Positive and Negative Affects and Cultural Attitudes among Representatives of the Host Population and Second-Generation Migrants in Russia and Kazakhstan

Abstract

1. Introduction

Study Design

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Method

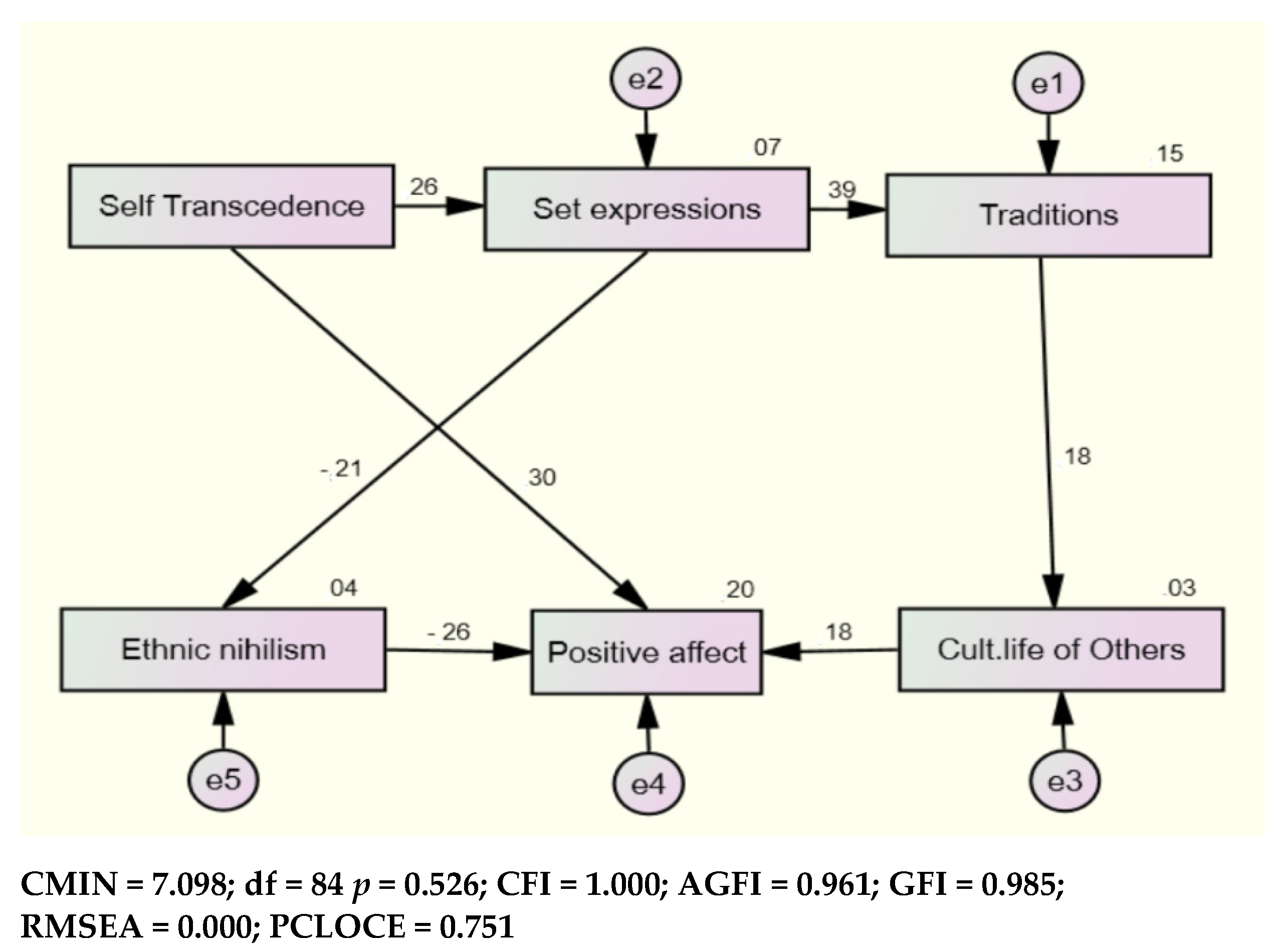

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barlow, Jane, Hanna Bergman, Hege Kornør, Yinghui Wei, and Cathy Bennett. 2016. Group-based parent training programmes for improving emotional and behavioural adjustment in young children. Cochrane Database Systematic Review 8: CD003680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benet-Martínez, Verónica, and Lydia Repke. 2020. Broadening the social psychological approach to acculturation: Cultural, personality and social-network approaches. International Journal of Social Psychology 35: 526–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabaniss, Emily Regis, and Abigail E. Cameron. 2018. Toward a social psychological understanding of migration and assimilation. Humanity & Society 42: 171–92. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, John R., and Julie D. Henry. 2004. The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 43: 245–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouhot, Lucas G., and Victor Nee. 2019. Assimilation and the Second Generation in Europe and America: Blending and Segregating Social Dynamics between Immigrants and Natives. Annual Review of Sociology 45: 177–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbrava, Costica. 2019. The ethno-demographic impact of co-ethnic citizenship in Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45: 958–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echterhoff, Gerald, Jens H. Hellmann, Mitja D. Back, Joscha Kärtner, Nexhmedin Morina, and Guido Hertel. 2020. Psychological antecedents of refugee integration (PARI). Perspectives on Psychological Science 15: 856–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, Nancy, Sandra Losoya, Richard A. Fabes, Ivanna K. Guthrie, Mark Reiser, Bridget Murphy, Stephanie A. Shepard, Rick Poulin, and Sarah J. Padgett. 2001. Parental socialization of children’s dysregulated expression of emotion and externalizing problems. Journal of Family Psychology 15: 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esses, Victoria M. 2020. Prejudice and Discrimination Toward Immigrants. Annual Review of Psychology 72: 503–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuligni, Andrew J. 2001. A comparative longitudinal approach to acculturation among children from immigrant families. Harvard Educational Review 71: 566–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritsenko, Valentina V., Oleg E. Khukhlaev, Raushaniia I. Zinurova, Vsevolod V. Konstantinov, Elena V. Kulesh, Ivan V. Malyshev, Irina A. Novikova, and Anna V. Chernaya. 2021. Intercultural Competence as a Predictor of Adaptation of Foreign Students. Cultural-Historical Psychology 17: 102–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, and Rolph E. Anderson. 2014. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Harpaz, Yossi. 2019. Compensatory citizenship: Dual nationality as a strategy of global upward mobility. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45: 897–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynie, Michaela. 2018. The Social Determinants of Refugee Mental Health in the Post-Migration Context: A Critical Review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 63: 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khukhlaev, Oleg E., Valentina V. Gritsenko, Soelma B. Dagbaeva, Vsevolod V. Konstantinov, Tatiana V. Kornienko, Elena V. Kulesh, and Tuyana T. Tudupova. 2022. Intercultural Competence and Effectiveness of Intercultural Communication. Experimental Psychology 15: 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinov, Vsevolod V. 2017. The Role of the Host Local Population in the Process of Migrants’ Adaptation. Social Sciences 6: 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovaleva, Yuliya V. 2020. Subjectivity and subjective well-being of representatives of large social groups on the example of the first and second generations of migrant from Armenia and Armenians living in their homeland. Social and Economic Psychology 5: 73–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kuleshov, Denis N. 2007. Theoretical and methodological aspects of studying population migration. Bulletin of the VEGU 31–32: 196–205. Available online: https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=13413867 (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Lebedeva, Nadezhda M. 2021. Ethnic Identity and Psychological Well-Being of Russians in Post-Soviet Space: The Role of Diaspora. Kul’turno-Istoricheskaya Psikhologiya = Cultural-Historical Psychology 17: 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Hyo-Seon, and Seok-Ki Kim. 2014. A qualitative study on the bicultural experience of second-generation Korean immigrants in Germany. Pacific Science Review 16: 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Blanco, Elma I., Alan Meca, Jennifer B. Unger, Andrea Romero, José Szapocznik, Brandy Piña-Watson, Miguel Ángel Cano, Byron L. Zamboanga, Lourdes Baezconde-Garbanati, Sabrina E. Des Rosiers, and et al. 2017. Longitudinal effects of Latino parent cultural stress, depressive symptoms, and family functioning on youth emotional well-being and health risk behaviors. Family Process 56: 981–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Blanco, Elma I., Alan Meca, Jennifer B. Unger, Andrea Romero, Melinda Gonzales-Backen, Brandy Piña-Watson, Miguel Ángel Cano, Byron L. Zamboanga, Sabrina E. Des Rosiers, Daniel W. Soto, and et al. 2016. Latino parent acculturation stress: Longitudinal effects on family functioning and youth emotional and behavioral health. Journal of Family Psychology 30: 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mähönen, Tuuli Anna, and Inga Jasinskaja-Lahti. 2013. Acculturation Expectations and Experiences as Predictors of Ethnic Migrants’ Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 44: 786–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martone, Jessica, Danielle Zimmerman, Maria Vidal de Haymes, and Lois Lorentzen. 2014. Immigrant integration through mediating social institutions: Issues and strategies. Journal of Community Practice 22: 299–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikova, Nadezhda M., Snezhana A. Kuznetsova, and Elena V. Charina. 2021. Virtual world as a way to preserve and form ethnic identity in the context of migration. Bulletin of the M.K. Ammosov North-Eastern Federal University. Series: Pedagogy. Psychology. Philosophy 4: 118–25. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, Mary, John Wong, and Andrew Trlin. 2006. Civic and social integration: A new field of social work practice with immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers. International Social Work 49: 345–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, Marisol. 2020. The psychosocial perspective on immigration: An introduction (la perspectiva psicosocial de la inmigración: Una introducción). International Journal of Social Psychology 35: 441–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newland, Lisa A. 2015. Family well-being, parenting, and child well-being: Pathways to healthy adjustment. Clinical Psychologist 19: 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osin, Evgeniy N. 2012. Izmerenie pozitivnykh i negativnykh emotsii: Razrabotka russkoyazychnogo analoga metodiki PANAS [Measuring Positive and Negative Affect: Development of a Russian-language Analogue of PANAS]. Psychology. Journal of Higher School of Economics 9: 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Rocheva, Anna L., Evgenij A. Varshaver, and Nataliya S. Ivanova. 2019. Integration of second-generation migrants from Transcaucasia and Central Asia in the Tyumen region: Social, linguistic and identification aspects. Bulletin of Archeology, Anthropology and Ethnography 2: 166–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryabichenko, Tatiana A., Nadezhda M. Lebedeva, and Irina D. Plotka. 2019. Multiple Identities, Acculturation and Adaptation of Russians in Latvia and Georgia. Kul’turno-Istoricheskaya Psikhologiya = Cultural-Historical Psychology 15: 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samokhvalova, Anna G., and Marina V. Mets. 2020. Intercultural Communicative Difficulties of Teens Migrants of the First and Second Generation: Cross-Cultural Aspect. Social Psychology and Society 11: 149–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Seth J., Alan Meca, Ward Colleen, Ágnes Szabó, Verónica Benet-Martínez, Elma I. Lorenzo-Blanco, Gillian Albert Sznitman, Cory L. Cobb, José Szapocznik, Jennifer B. Unger, and et al. 2019. Biculturalism dynamics: A daily diary study of bicultural identity and psychosocial functioning. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 62: 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Shalom, Tatiana P. Butenko, Dariya S. Sedova, and Anna S. Lipatova. 2012. Refined theory of basic individual values: Application in Russia. Psychology. Journal of the Higher School of Economics 9: 43–70. [Google Scholar]

- Selyaninova, Gulsina D. 2020. Migrants in Perm: From adaptation to well-being. Modern City: Power, Management, Economy 1: 204–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamionov, Rail M. 2012. Psychological characteristics of personal social activity. World of Psychology 3: 145–54. [Google Scholar]

- Shamionov, Rail M., Marina V. Grigoryeva, and Nataliya V. Usova. 2013. The subjective well-being of Russian migrants in Spane and foreigners in Russia. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 86: 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Rebecca L., Christina M. Chiarelli-Helminiak, Brunilda Ferraj, and Kyle Barrette. 2016. Building relationships and facilitating immigrant community integration: An evaluation of a Cultural Navigator Program. Evaluation and Program Planning 55: 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoukalas, Spyridon, Filotheos Ntalianis, Petros Papageorgiou, and Symeon Retalis. 2010. The impact of training on first generation immigrants: Preliminary findings from Greece. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 3: 5529555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, David. 2002. Positive affectivity: The disposition to experience pleasurable emotional states. In Handbook of Positive Psychology. Edited by C. R. Snyder and Shane J. Lopez. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 106–19. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, David, Lee A. Clark, and Auke Tellegen. 1988. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54: 1063–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, Rebecca, Magdalena Arias Cubas, Derya Ozkul, Cailin Maas, Chulhyo Kim, Elsa Koleth, and Stephen Castles. 2022. Migration and social transformation through the lens of locality: A multi-sited study of experiences of neighbourhood transformation. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48: 3041–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Host Population (n = 150) | Second Generation of Migrants (n = 150) | Total (n = 300) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %/Mean | SD | %/Mean | SD | %/Mean | SD | |

| Age | 39.15 | (12.0) | 37.72 | (10.89) | 38.44 | (11.57) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 25.3% | 26.7% | 26% | |||

| Female | 74.7% | 73.3% | 74% | |||

| Residence | ||||||

| Rural area | 26.7% | 35.3% | 34% | |||

| City | 73.3% | 64.7% | 69% | |||

| Education | ||||||

| School level | 11.4 | 14.7 | 13.0 | |||

| Vocational | 27.5 | 38.0 | 32.8 | |||

| University level | 61.1 | 47.3 | 54.2 | |||

| M1 | SD | M2 | SD | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tendency to follow ethnic group traditions (CA1) | 4.16 | 0.87 | 4.03 | 0.95 | 1.21 | 0.23 |

| Knowledge of ethnic traditions (CA10) | 4.09 | 0.81 | 3.78 | 0.93 | 3.13 | 0.00 |

| Tendency to use sayings (set expressions) of the ethnic group (CA2) | 4.08 | 1.10 | 3.57 | 1.33 | 3.60 | 0.00 |

| Ethnic language proficiency (CA8) | 4.30 | 1.00 | 3.81 | 1.31 | 3.62 | 0.00 |

| Tendency to participate in the people’s religious life (CA3) | 4.38 | 0.77 | 4.25 | 0.85 | 1.42 | 0.16 |

| Inclusion in the culture and traditions of the ethnic group (CA11) | 4.01 | 1.05 | 3.43 | 1.06 | 4.75 | 0.00 |

| Desire to change ethnic identity (CA4) | 1.34 | 0.93 | 1.31 | 0.80 | 0.27 | 0.79 |

| Tendency to view the culture of one’s people as a source of its unity and stability (CA12) | 4.25 | 0.94 | 3.79 | 1.06 | 3.98 | 0.00 |

| R) “Moral and ethical norms of an ethnos limit individuality” attitude (CA9) | 3.85 | 1.11 | 3.69 | 1.06 | 0.20 | 0.16 |

| Participation in the cultural life of other ethnic groups (CA5) | 3.44 | 1.50 | 3.65 | 1.27 | -1.33 | 0.19 |

| Positive attitude towards cultural borrowings (CA6) | 3.45 | 1.05 | 3.03 | 1.16 | 3.29 | 0.00 |

| Tendency to mix cultures and traditions (CA7) | 4.09 | 1.06 | 3.85 | 1.07 | 1.96 | 0.05 |

| R) Tendency to mix ethnic cultures (CA13) | 2.40 | 1.16 | 2.19 | 1.01 | 1.69 | 0.09 |

| Interest in the ethnic group’s history (CA14) | 4.04 | 1.11 | 3.51 | 1.31 | 3.85 | 0.00 |

| Cultural Attitudes | Beta | t | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host population | |||

| Participation in the cultural life of other ethnic groups (CA5) | 0.22 | 2.79 | 0.01 |

| Using sayings and proverbs of one’s ethnic group in speech (CA2) | 0.19 | 2.35 | 0.02 |

| “Moral and ethical norms of an ethnos limit individuality” attitude (CA9) | 0.17 | 2.17 | 0.03 |

| R2 = 0.13, F = 7.1, p < 0.001 | |||

| Representatives of the second generation of migrants | |||

| Tendency to follow ethnic group traditions (CA1) | 0.29 | 2.47 | 0.02 |

| Positive attitude towards cultural borrowing (CA6) | 0.16 | 2.09 | 0.04 |

| Participation in the religious life of one’s ethnic group (CA3) | 0.19 | 2.32 | 0.02 |

| Desire to change ethnic identity (CA4) | 0.16 | 2.00 | 0.05 |

| R2 = 0.16, F = 6.95, p < 0.001 | |||

| Cultural Attitudes | Beta | t | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host population | |||

| Moral and ethical norms of an ethnos limit individuality (CA9) | −0.19 | 2.48 | 0.01 |

| Interest in the history of an ethnic group (CA14) | −0.20 | 2.53 | 0.01 |

| R) Tendency to mix ethnic cultures (CA13) | 0.21 | 2.81 | 0.01 |

| Tendency to view the culture of one’s people as a source of its unity and stability (CA12) | −0.24 | 2.82 | 0.01 |

| Participation in the religious life of one’s ethnic group (CA3) | 0.20 | 2.65 | 0.01 |

| R2 = 0.24, F = 9.1, p < 0.001 | |||

| Representatives of the second generation of migrants | |||

| Participation in the cultural life of other ethnic groups (CA5) | −0.26 | 3.25 | 0.001 |

| Ethnic language proficiency (CA8) | −0.16 | 2.03 | 0.04 |

| R2 = 0.10, F = 8.2, p < 0.001 | |||

| Beta | t | Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive affect | |||

| Host population: ethno-nihilism | −0.27 | 3.45 | 0.001 |

| R2 = 0.08, F = 11.87, p < 0.001 | |||

| Negative affect | |||

| Host population: ethno-nihilism | 0.32 | 4.06 | 0.001 |

| R2 = 0.10, F = 16.44, p < 0.001 | |||

| Second generation of migrants: ethno-egoism | 0.29 | 3.61 | 0.001 |

| R2 = 0.08, F = 13.04, p < 0.001 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shamionov, R.M.; Sultaniyazova, N.J.; Bolshakova, A.S. Positive and Negative Affects and Cultural Attitudes among Representatives of the Host Population and Second-Generation Migrants in Russia and Kazakhstan. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100473

Shamionov RM, Sultaniyazova NJ, Bolshakova AS. Positive and Negative Affects and Cultural Attitudes among Representatives of the Host Population and Second-Generation Migrants in Russia and Kazakhstan. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(10):473. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100473

Chicago/Turabian StyleShamionov, Rail M., Nasiya J. Sultaniyazova, and Alina S. Bolshakova. 2022. "Positive and Negative Affects and Cultural Attitudes among Representatives of the Host Population and Second-Generation Migrants in Russia and Kazakhstan" Social Sciences 11, no. 10: 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100473

APA StyleShamionov, R. M., Sultaniyazova, N. J., & Bolshakova, A. S. (2022). Positive and Negative Affects and Cultural Attitudes among Representatives of the Host Population and Second-Generation Migrants in Russia and Kazakhstan. Social Sciences, 11(10), 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100473