Who Believes in Fake News? Identification of Political (A)Symmetries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Believing in Fake News

3. Motivated Reasoning and Fake News Belief

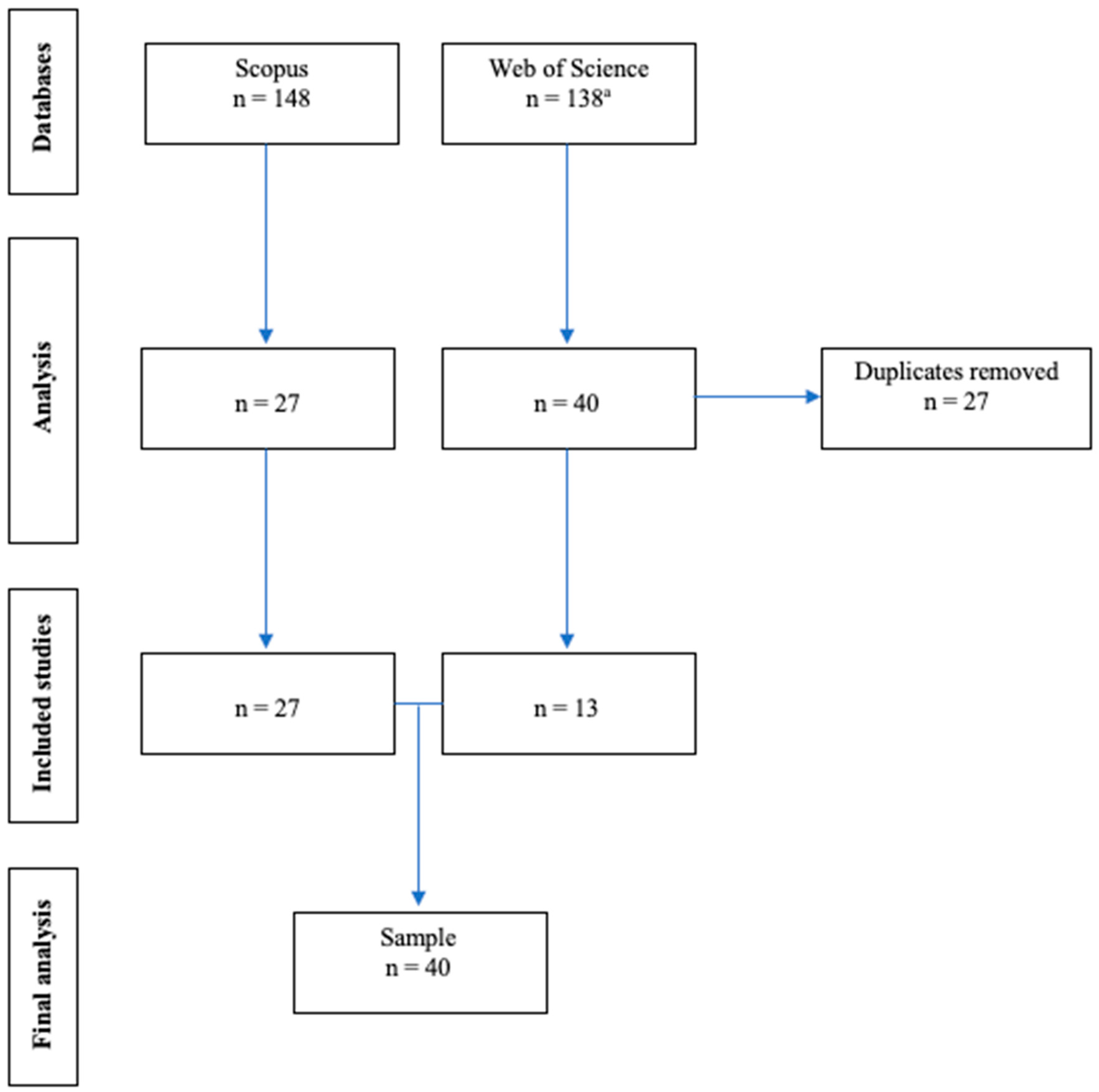

4. Methods

5. Bibliographic Analysis

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bago, Bence, David G. Rand, and Gordon Pennycook. 2020. Fake news, fast and slow: Deliberation reduces belief in false (but not true) news headlines. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 149: 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmas, Meital. 2014. When fake news becomes real: Combined exposure to multiple news sources and political attitudes of inefficacy, alienation, and cynicism. Communication Research 41: 430–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, João Pedro, and Anabela Gradim. 2020. Understanding fake news consumption: A review. Social Sciences 9: 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, João Pedro, and Anabela Gradim. 2021. “Brave New World” of Fake News: How It Works. Javnost-The Public 28: 426–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, João Pedro, and Anabela Gradim. 2022a. A Working Definition of Fake News. Encyclopedia 2: 632–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, João Pedro, and Anabela Gradim. 2022b. Online disinformation on Facebook: The spread of fake news during the Portuguese 2019 election. Journal of Contemporary European Studies 30: 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, João Pedro, and Marlene Loureiro. 2018. Ideologia Política Esquerda-Direita–Estudo Exploratório do Eleitorado Português. Interações: Sociedade e as novas modernidades 35: 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, João Pedro, Elisete Correia, Anabela Gradim, and Valeriano Piñeiro-Naval. 2021a. The influence of political ideology on fake news belief: The Portuguese case. Publications 9: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, João Pedro, Elisete Correia, Anabela Gradim, and Valeriano Piñeiro-Naval. 2021b. A ciência cognitiva e a crença em fake news: Um estudo exploratório. Eikon 9: 103–14. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, João Pedro, Elisete Correia, Anabela Gradim, and Valeriano Piñeiro-Naval. 2021c. Partisanship: The true ally of fake news? a comparative analysis of the effect on belief and spread. Revista Latina de Comunicacion Social 79: 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnidge, Matthew, Albert Gunther, Jinha Kim, Yangsun Hong, Mallory Perryman, Swee Kiat Tay, and Sandra Knisely. 2020. Politically motivated selective exposure and perceived media bias. Communication Research 47: 82–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Shanto Iyengar. 2008. A new era of minimal effects? The changing foundations of political communication. Journal of Communication 58: 707–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Steven Livingston. 2018. The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication 33: 122–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brashier, Nadia M., and Daniel L. Schacter. 2020. Aging in an era of fake news. Current Directions in Psychological Science 29: 316–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, Axel M., Stefan Pfattheicher, and Melissa Jauch. 2020. The role of motivation in the association of political ideology with cognitive performance. Cognition 195: 104124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Kaileigh A., Crina D. Silasi-Mansat, and Darrell A. Worthy. 2015. Who chokes under pressure? The Big Five personality traits and decision-making under pressure. Personality and Individual Differences 74: 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvillo, Dustin P., Abraham Rutchick, and Ryan J. Garcia. 2021b. Individual Differences in Belief in Fake News about Election Fraud after the 2020 US Election. Behavioral Sciences 11: 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvillo, Dustin P., Bryan J. Ross, Ryan J. B. Garcia, Thomas J. Smelter, and Abraham M. Rutchick. 2020. Political ideology predicts perceptions of the threat of COVID-19 (and susceptibility to fake news about it). Social Psychological and Personality Science 11: 1119–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvillo, Dustin P., Ryan Garcia, Kian Bertrand, and Tommi A. Mayers. 2021a. Personality factors and self-reported political news consumption predict susceptibility to political fake news. Personality and Individual Differences 174: 110666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deppe, Kristen D., Frank J. Gonzalez, Jayme Neiman, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Jackson Pahlke, Kevin Smith, and John R. Hibbing. 2015. Reflective liberals and intuitive conservatives: A look at the Cognitive Reflection Test and ideology. Judgment and Decision Making 10: 314–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ditto, Peter H., Brittany S. Liu, Cory J. Clark, Sean P. Wojcik, Eric E. Chen, Rebecca H. Grady, Jared B. Celniker, and Joanne F. Zinger. 2019. At least bias is bipartisan: A meta-analytic comparison of partisan bias in liberals and conservatives. Perspectives on Psychological Science 14: 273–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, Christopher. 2018. Religion and Fake News: Faith-Based Alternative Information Ecosystems in the US and Europe. Review of Faith and International Affairs 16: 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, Karen M., Joseph E. Uscinski, Robbie Sutton, Aleksandra Cichocka, Turkay Nefes, Chen Siang Ang, and Farzin Deravi. 2019. Understanding conspiracy theories. Political Psychology 40: 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, Elizabeth, and Grant Blank. 2018. The echo chamber is overstated: The moderating effect of political interest and diverse media. Information, Communication and Society 21: 729–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effron, Daniel A., and Medha Raj. 2019. Misinformation and Morality: Encountering Fake-News Headlines Makes Them Seem Less Unethical to Publish and Share. Psychological Science 31: 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egelhofer, Jana Laura, and Sophie Lecheler. 2019. Fake news as a two-dimensional phenomenon: A framework and research agenda. Annals of the International Communication Association 43: 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faragó, Laura, Anna Kende, and Péter Krekó. 2019. We only believe in news that we doctored ourselves: The connection between partisanship and political fake news. Social Psychology 51: 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fessler, Daniel M. T., Anne C. Pisor, and Colin Holbrook. 2017. Political Orientation Predicts Credulity Regarding Putative Hazards. Psychological Science 28: 651–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, Richard, Alessio Cornia, Lucas Graves, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2018. Measuring the Reach of “Fake News” and Online Disinformation in Europe. Oxford: Reuters Institute Factsheet, University of Oxford, Oxford. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/INFORMIT.807732061612771 (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Freire, André. 2006. Esquerda e Direita na Política Europeia: Portugal, Espanha e Grécia em Perspectiva Comparada. Lisboa: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [Google Scholar]

- Frischlich, Lena, Jens H. Hellmann, Felix Brinkschulte, Martin Becker, and Mitja D. Back. 2021. Right-wing authoritarianism, conspiracy mentality, and susceptibility to distorted alternative news. Social Influence 16: 24–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, R. Kelly, Erik C. Nisbet, and Emily L. Lynch. 2013. Undermining the corrective effects of media-based political fact checking? The role of contextual cues and naïve theory. Journal of Communication 63: 617–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, R. Kelly, Shira Dvir Gvirsman, Benjamin K. Johnson, Yariv Tsfati, Rachel Neo, and Aysenur Dal. 2014. Implications of pro-and counterattitudinal information exposure for affective polarization. Human Communication Research 40: 309–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfert, Alex. 2018. Fake news: A definition. Informal Logic 38: 84–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, Rebecca Hofstein, Peter Ditto, and Elizabeth Loftus. 2021. Nevertheless, partisanship persisted: Fake news warnings help briefly, but bias returns with time. Cognitive Research 6: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinberg, Nir, Kenneth Joseph, Lisa Friedland, Briony Swire-Thompson, and David Lazer. 2019. Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Science 363: 374–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guess, Andrew, Jonathan Nagler, and Joshua Tucker. 2019. Less than you think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Science Advances 5: eaau4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameleers, Michael, and Sophie Minihold. 2020. Constructing discourses on (un) truthfulness: Attributions of reality, misinformation, and disinformation by politicians in a comparative social media setting. Communication Research, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameleers, Michael. 2020. My reality is more truthful than yours: Radical right-wing politicians’ and citizens’ construction of “fake” and “truthfulness” on social media—Evidence from the United States and The Netherlands. International Journal of Communication 14: 1135–52. [Google Scholar]

- Holbert, R. Lance. 2005. A typology for the study of entertainment television and politics. American Behavioral Scientist 49: 436–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, Toby, Patrick Ferrucci, and Chris J. Vargo. 2020. Why do people share ideologically extreme, false, and misleading content on social media? A self-report and trace data–based analysis of countermedia content dissemination on Facebook and Twitter. Human Communication Research 46: 357–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, Christy Galleta, Dennis Galletta, Jennifer Crawford, and Abhijeet Shirsat. 2021. Emotions: The Unexplored Fuel of Fake News on Social Media. Journal of Management Information Systems 38: 1039–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humprecht, Edda. 2020. How Do They Debunk “Fake News”? A Cross-National Comparison of Transparency in Fact Checks. Digital Journalism 8: 310–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S. Mo, and Joon K. Kim. 2018. Third person effects of fake news: Fake news regulation and media literacy interventions. Computers in Human Behavior 80: 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Jang, S. Mo, Tara Mortensen, and Jingjing Liu. 2021. Does media literacy help identification of fake news? Information literacy helps, but other literacies don’t. American Behavioral Scientist 65: 371–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, John T., Jack Glaser, Arie Kruglanski, and Frank Sulloway. 2003. Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin 129: 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudrnáč, Aleš. 2020. What Does It Take to Fight Fake News? Testing the Influence of Political Knowledge, Media Literacy, and General Trust on Motivated Reasoning. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 53: 151–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, M. Asher, and Hemant Kakkar. 2021. Of pandemics, politics, and personality: The role of conscientiousness and political ideology in the sharing of fake news. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 151: 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowsky, Sephan, Werner G. K. Stritzke, Alexandra M. Freund, Klaus Oberauer, and Joachim Krueger. 2013. Misinformation, disinformation, and violent conflict: From Iraq and the “War on Terror” to future threats to peace. American Psychologist 68: 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva, Rodolfo, and Charlie Beckett. 2020. Testing and unpacking the effects of digital fake news: On presidential candidate evaluations and voter support. AI and SOCIETY 35: 969–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodge, Milton, and Charles S. Taber. 2005. The automaticity of affect for political leaders, groups, and issues: An experimental test of the hot cognition hypothesis. Political Psychology 26: 455–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz-Spreen, Philipp, Stephan Lewandowsky, Cass R. Sunstein, and Ralph Hertwig. 2020. How behavioural sciences can promote truth, autonomy and democratic discourse online. Nature Human Behaviour 4: 1102–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, Ben, Vittorio Mérola, Jason Reifler, and Florian Stoeckel. 2020. How politics shape views toward fact-checking: Evidence from six European countries. The International Journal of Press/Politics 25: 469–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancosu, Moreno, Salvatore Vassallo, and Cristiano Vezzoni. 2017. Believing in Conspiracy Theories: Evidence from an Exploratory Analysis of Italian Survey Data. South European Society and Politics 22: 327–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, Cameron, Gordon Pennycook, and David G. Rand. 2020. Reliance on emotion promotes belief in fake news. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications 5: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougall, Julian, Maria-José Brites, Maria-João Couto, and Catarina Lucas. 2019. Digital literacy, fake news and education/Alfabetización digital, fake news y educación. Cultura y Educación 31: 203–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, William J. 1964. Inducing resistance to persuasion: Some contemporary approaches. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Edited by Leonard Berkowitz. New York: Academic Press, vol. 1, pp. 191–229. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, Lee. 2018. Post-Truth. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- McPhetres, Jonathon, David G. Rand, and Gordon Pennycook. 2021. Character deprecation in fake news: Is it in supply or demand? Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 24: 624–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, Hugo, and Dan Sperber. 2017. The Enigma of Reason. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Messing, Solomon, and Sean J. Westwood. 2014. Selective exposure in the age of social media: Endorsements trump partisan source affiliation when selecting news online. Communication Research 41: 1042–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, David S., Jonathan S. Morris, and Peter L. Francia. 2020. A fake news inoculation? Fact checkers, partisan identification, and the power of misinformation. Politics, Groups, and Identities 8: 986–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Jacob L., and Harsh Taneja. 2018. The small, disloyal fake news audience: The role of audience availability in fake news consumption. New Media and Society 20: 3720–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, Raymond. 1998. Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology 2: 175–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, Artur, Arvid Erlandsson, and Daniel Västfjäll. 2019. The complex relation between receptivity to pseudo-profound bullshit and political ideology. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 45: 1440–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyhan, Brendan, and Jason Reifler. 2010. When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Political Behavior 32: 303–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmundsen, Masthias, Alexander Bor, Peter Bkerregaard Vahlstrup, Anja Bechmann, and Michael Bang Petersen. 2021. Partisan polarization is the primary psychological motivation behind political fake news sharing on Twitter. American Political Science Review 115: 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascale, Celine-Marei. 2019. The weaponization of language: Discourses of rising right-wing authoritarianism. Current Sociology 67: 898–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, Gordon, and David G. Rand. 2019a. Lazy, not biased: Susceptibility to partisan fake news is better explained by lack of reasoning than by motivated reasoning. Cognition 188: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennycook, Gordon, and David G. Rand. 2019b. Fighting misinformation on social media using crowdsourced judgments of news source quality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116: 2521–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, Gordon, and David G. Rand. 2020. The Psychology of Fake News. PsyArXiv Preprints. Available online: https://psyarxiv.com/ar96c/ (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Pennycook, Gordon, Tyrone Cannon, and David G. Rand. 2018. Prior exposure increases perceived accuracy of fake news. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 147: 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Andrea, Elizabeth Harris, and Jay J. Van Bavel. 2018. Identity concerns drive belief: The impact of partisan identity on the belief and dissemination of true and false news. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, Michael Bang, Mathias Osmundsen, and Kevin Arceneaux. 2020. The “need for chaos” and motivations to share hostile political rumors. PsyArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pian, Wenjing, Jianxing Chi, and Feicheng Ma. 2021. The causes, impacts and countermeasures of COVID-19 “Infodemic”: A systematic review using narrative synthesis. Information Processing and Management 58: 102713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierri, Francesco, Alessandro Artoni, and Stefano Ceri. 2020. Investigating Italian disinformation spreading on Twitter in the context of 2019 European elections. PLoS ONE 15: e0227821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, Ian. 2012. Satirical fake news and/as American political discourse. The Journal of American Culture 35: 258–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rini, Regina. 2017. Fake news and partisan epistemology. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 27: 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, Craig T., Rachel Mourão, and Esther Thorson. 2020. Who uses fact-checking sites? The impact of demographics, political antecedents, and media use on fact-checking site awareness, attitudes, and behavior. The International Journal of Press/Politics 25: 217–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roets, Arne. 2017. ‘Fake news’: Incorrect, but hard to correct. The role of cognitive ability on the impact of false information on social impressions. Intelligence 65: 107–10. [Google Scholar]

- Roozenbeek, Jon, and Sander van der Linden. 2019. The fake news game: Actively inoculating against the risk of misinformation. Journal of Risk Research 22: 570–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardigno, Rosa, and Giuseppe Mininni. 2020. The rhetoric side of fake news: A new weapon for anti-politics? World Futures 76: 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, Anne, Werner Wirth, and Philipp Müller. 2020. We are the people and you are fake news: A social identity approach to populist citizens’ false consensus and hostile media perceptions. Communication Research 47: 201–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Jieun, and Kjerstin Thorson. 2017. Partisan selective sharing: The biased diffusion of fact-checking messages on social media. Journal of Communication 67: 233–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, C., Lauren Strapagiel, Hamza Shaban, Ellie Hall, and Jeremy Singer-Vine. 2016. Hyperpartisan Facebook pages are publishing false and misleading information at an alarming rate. Buzzfeed News. October 20. Available online: https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/partisan-fb-pages-analysis (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Silverman, Craig, and Lawrence Alexander. 2016. How teens in the Balkans are duping Trump supporters with fake news. Buzzfeed News. November 3. Available online: https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/how-macedonia-became-a-global-hub-for-pro-trump-misinfo (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Silverman, Craig. 2016. Here are 50 of the biggest fake news hits on Facebook from 2016. Buzzfeed News. December 30. Available online: https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/top-fake-news-of-2016 (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Sinclair, Alyssa H., Matthew L. Stanley, and Paul Seli. 2020. Closed-minded cognition: Right-wing authoritarianism is negatively related to belief updating following prediction error. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review 27: 1348–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindermann, Cornelia, Andrew Cooper, and Christian Montag. 2020. A short review on susceptibility to falling for fake political news. Current Opinion in Psychology 36: 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, Matthew L., Nathaniell Barr, Kelly Peters, and Paul Seli. 2020. Analytic-thinking predicts hoax beliefs and helping behaviors in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Thinking and Reasoning 27: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterrett, David, Dan Malato, Jennifer Benz, Liz Kantor, Trevor Tompson, Tom Rosenstiel, Jeff Sonderman, and Kevin Loker. 2019. Who Shared It?: Deciding What News to Trust on Social Media. Digital Journalism 7: 783–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stier, Sebastian, Nora Kirkizh, Caterina Froio, and Ralph Schroeder. 2020. Populist attitudes and selective exposure to online news: A cross-country analysis combining web tracking and surveys. The International Journal of Press/Politics 25: 426–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, Samanth. 2017. Inside the Macedonian fake-news complex. Wired Magazine. February 15. Available online: https://www.wired.com/2017/02/veles-macedonia-fake-news/ (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Szebeni, Zea, Jan-Erik Lönnqvist, and Inga Jasinskaja-Lahti. 2021. Social Psychological Predictors of Belief in Fake News in the Run-Up to the 2019 Hungarian Elections: The Importance of Conspiracy Mentality Supports the Notion of Ideological Symmetry in Fake News Belief. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Taber, Charles S., and Milton Lodge. 2006. Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science 50: 755–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, Shalini, Amandeep Dhir, Puneet Kaur, Nida Zafar, and Melfi Alrasheedy. 2019. Why do people share fake news? Associations between the dark side of social media use and fake news sharing behavior. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 51: 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, Edson, Zheng Wei Lim, and Richard Ling. 2018. Defining “Fake News”: A typology of scholarly definitions. Digital Journalism 6: 137–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorson, Emily. 2016. Belief echoes: The persistent effects of corrected misinformation. Political Communication 33: 460–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonković, Mirjana, Francesca Dumančić, Margareta Jelić, and Dinka Čorkalo Biruški. 2021. Who Believes in COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories in Croatia? Prevalence and Predictors of Conspiracy Beliefs. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 643568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uscinski, Joseph E., Casey Klofstad, and Matthew Atkinson. 2016. What drives conspiratorial beliefs? The role of informational cues and predispositions. Political Research Quarterly 69: 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, Sander, Costas Panagopoulos, and Jon Roozenbeek. 2020a. You are fake news: Political bias in perceptions of fake news. Media, Culture and Society 42: 460–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, Sander, Jon Roozenbeek, and Josh Compton. 2020b. Inoculating against fake news about COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 566790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kessel, Stijn, Javier Sajuria, and Steven Van Hauwaert. 2021. Informed, uninformed or misinformed? A cross-national analysis of populist party supporters across European democracies. West European Politics 44: 585–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, Brian E., Ericka Menchen-Trevino, Christopher Calabrese, Andreu Casas, and Magdalena Wojcieszak. 2021. Partisan media, untrustworthy news sites, and political misperceptions. New Media and Society, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Whitsitt, Lynnette, and Robert Williams. 2019. Political Ideology and Accuracy of Information. Innovative Higher Education 44: 423–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolverton, Colleen, and David Stevens. 2019. The impact of personality in recognizing disinformation. Online Information Review 44: 181–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, Franziska, Katrin Scheibe, Wolfgang Stock, and Mechtild Stock. 2019. Echo chambers and filter bubbles of fake news in social media. Man-made or produced by algorithms. Paper presented at the 8th Annual Arts, Humanities, Social Sciences and Education Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, January 3–5; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, Fabian, and Matthias Kohring. 2020. Mistrust, Disinforming News, and Vote Choice: A Panel Survey on the Origins and Consequences of Believing Disinformation in the 2017 German Parliamentary Election. Political Communication 37: 215–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Country | Method or Data | Main Findings Related to Our Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pennycook and Rand (2019a) | US | Survey = Exposure to fake and real headlines | Trump supporters (Conservatives/Republicans) were less able to discern fake news (vs. Clinton supporters/Liberals/Democrats) |

| Pennycook and Rand (2019b) | US | Classification of news sources (traditional media, hyperpartisan and fake news sites) according to familiarity and trust | Democrats were better at assessing media reliability, and their ratings were more strongly correlated with those of fact-checkers. |

| Calvillo et al. (2020) | US | Survey = Exposure to fake and real headlines | Conservatism was identified as a predictor of belief in COVID-19 fake news, had a less accurate discernment for true and false COVID-19 headlines. |

| Hameleers (2020) | US & NL | Content analysis: Twitter and Facebook messages | Right-wing populists in both countries label the media as fake news to de-legitimize their credibility. Left populists emphasize other divisions and do not blame the media. |

| Osmundsen et al. (2021) | US | Survey and collection of (re)tweets on twitter | Republicans are more likely to share fake news compared to Democrats. |

| van Kessel et al. (2021) | Europe | Cross-national survey | High levels of online disinformation increase the likelihood of supporting a right-wing populist party. Being uninformed is more common among people who support right-wing populist parties |

| Calvillo et al. (2021a) | US | Survey = Exposure to fake and real headlines | Political conservatism were negatively related to the news discernment. |

| Baptista et al. (2021a) | PT | Survey = Exposure to fake and real headlines | Ideologically right-wing people (conservatives) exhibited a greater tendency to believe fake news, regardless of whether it is pro-left or pro-right fake news. |

| Weeks et al. (2021) | US | Exposure to disinformation sites based on web search history | Conservatives are more likely to expose themselves and engage with uninformative content. |

| Calvillo et al. (2021b) | US | Survey = Exposure to fake and real headlines | Conservatism is associated with a greater belief in fake news that support voter fraud in the 2020 US elections. |

| Frischlich et al. (2021) | DE | Survey = Exposure to distorted news article and a typical journalist news media report. | High (vs. low) authoritarians perceived distorted news with a right- wing editorial line to be more credible and also perceived a distorted news article with a left-leaning editorial stance as being more credible. |

| Baptista et al. (2021c) | PT | Survey = Exposure to fake and real headlines | Right-wing supporters (vs. left-wing supporters) are more likely to believe and share compatible fake news. |

| Whitsitt and Williams (2019) | US | Classroom sessions: classification of politically accurate or inaccurate items | Conservative students were less accurate in judging false political statements than liberal and independent students. |

| Lawson and Kakkar (2021) | US | Survey: Exposure to real and fake COVID-19 news stories | Sharing of fake news is largely driven by low conscientiousness conservatives. The authors found no differences in political ideology regarding high levels of consciousness. |

| Morris et al. (2020) | US | Survey = Exposure to fake and real news stories | Fake news inoculation effect: Conservatives (vs. liberals) are more likely to find the “truth” in fake news. |

| Guess et al. (2019) | US | Survey and Facebook profile data = Combining interviews with data about your actual behavior on social media | Conservatives are more likely to share fake news than liberals or moderates. |

| Grinberg et al. (2019) | US | Tweets Collection | Conservatives are more likely to engage with fake news sources. |

| Zimmermann and Kohring (2020) | DE | Collected survey data | Belief in fake news may have favored the right-wing populist party in the 2017 elections in Germany, radicalizing supporters of the moderate right. |

| Kudrnáč (2020) | CZ | Survey = Exposure to a political caricature or a graphic with a brief political declarative expression | The study demonstrates that motivated reasoning has a different effect for liberal and conservative students. |

| Leyva and Beckett (2020) | US | Survey = Exposure to Facebook news feed posts and online news article | Fake news can reinforce the partisan dispositions of particularly politically conservative users. |

| Study | Country | Method or Data | Main Findings Related to Our Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jang and Kim (2018) | US | Survey = Perceived influence of fake news on self and political groups | Third person effects of fake news: Both Republicans and Democrats believe that fake news is more influential outside the group. |

| van der Linden et al. (2020a) | US | National Survey | Both liberals and conservatives use the term fake news to label traditional media. |

| Faragó et al. (2019) | HU | Survey = Exposure to fake and real headlines | Both people (who supported and did not support the government) believe more in fake news consistent with their beliefs. |

| Pennycook et al. (2018) | US | Survey = Exposure to fake and real headlines | Trump supporters were more skeptical about mismatched fake news headlines than Clinton supporters (and vice versa). |

| Grady et al. (2021) | US | Survey = Exposure to fake and real headlines with warning and without warning | Falsehood warning discourages belief in fake headlines. Two weeks later, the partisan bias persists for both Democrats and Republicans. |

| McPhetres et al. (2021) | US | Survey = Exposure to politically biased“character-focused” | Political news of character depreciation seems equally appealing to Democrats and Republicans. |

| Szebeni et al. (2021) | HU | Survey = Exposure to fake and real headlines | Participants (pro and anti-government) exhibited bias according to their political preferences. |

| Pereira et al. (2018) | US | Experimental Survey = Exposure to fake and real headlines | Democrats and Republicans are more likely to believe and share compatible political news content. |

| Hopp et al. (2020) | US | Data collected on social media | Sharing countermedia content is positively associated with the ideological extremity (liberal or conservative). |

| Horner et al. (2021) | US | Survey = Exposure to fake and real headlines | In general, both Democrats and Republicans considered fake headlines attacking the opposing political party more credible than those attacking their own. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baptista, J.P.; Gradim, A. Who Believes in Fake News? Identification of Political (A)Symmetries. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100460

Baptista JP, Gradim A. Who Believes in Fake News? Identification of Political (A)Symmetries. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(10):460. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100460

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaptista, João Pedro, and Anabela Gradim. 2022. "Who Believes in Fake News? Identification of Political (A)Symmetries" Social Sciences 11, no. 10: 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100460

APA StyleBaptista, J. P., & Gradim, A. (2022). Who Believes in Fake News? Identification of Political (A)Symmetries. Social Sciences, 11(10), 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100460