The Subjective Well-Being of Children in Residential Care: Has It Changed in Recent Years?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

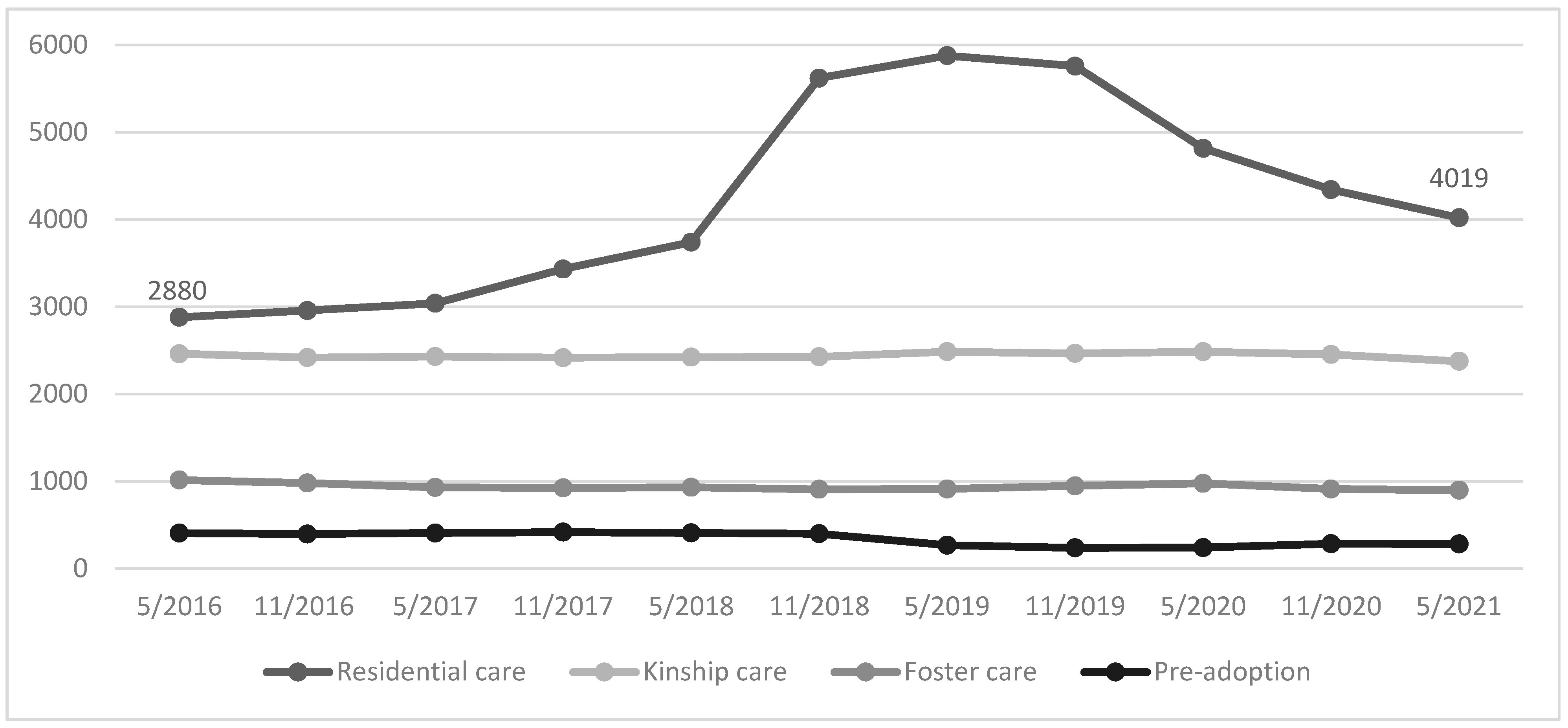

1.1. Residential Care in Spain

1.2. The Subjective Well-Being of Children in Residential Care

1.3. Measuring Subjective Well-Being over Time

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments and Procedure

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ben-Arieh, Asher. 2008. The child indicators movement: Past, present and future. Child Indicators Research 1: 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonal, Xavier, and Sheila González. 2020. The impact of lockdown on the learning gap: Family and school divisions in times of crisis. International Review of Education 66: 635–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, Joao, Paulo Delgado, Carme Montserrat, Joan Llosada-Gistau, and Ferran Casas. 2020. Subjective Well-Being of Children in Care: Comparison between Portugal and Catalonia. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 38: 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, Ferran. 2011. Subjective Social Indicators and Child and Adolescent Well-being. Child Indicators Research 4: 555–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, Robert A. 2010. Subjective Wellbeing, homeostatically protected mood and depression: A synthesis. Journal of Happiness Studies 11: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Valle, Jorge Fernández, and Ferran Casas. 2002. Child residential care in the Spanish social protection system. International Journal of Child and Family Welfare 5: 112–28. [Google Scholar]

- Del Valle, Jorge Fernández, Mónica López, Carme Montserrat, and Amaia Bravo. 2009. Twenty years of foster care in Spain. Profiles, patterns and outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review 31: 847–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, Paulo, Joao Carvalho, Carme Montserrat, and Joan Llosada-Gistau. 2020. The Subjective Well-Being of Portuguese Children in Foster Care, Residential Care and Children Living with their Families: Challenges and Implications for a Child Care System Still Focused on Institutionalization. Child Indicators Research 13: 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DGAIA [Catalan Directorate General of Child and Adolescent Care]. 2021. Official Statistics on Child Protection. Available online: https://treballiaferssocials.gencat.cat/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Dinisman, Tamar, Carme Montserrat, and Ferran Casas. 2012. The subjective well-being of Spanish adolescents: Variations according to different living arrangements. Children and Youth Services Review 34: 2374–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Molsosa, Marta, Jordi Collet-Sabé, Joan Carles Martori, and Carme Montserrat. 2019. School satisfaction among youth in residential care: A multi-source analysis. Children and Youth Services Review 105: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Molsosa, Marta, Jordi Collet-Sabé, and Carme Montserrat. 2020. What are the factors influencing the school functioning of children in residential care: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review 120: 105740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, Carla, Alba Águila-Otero, Carme Montserrat, Susana Lázaro-Visa, Eduardo Martín, Jorge Fernández del Valle, and Amaia Bravo. 2021. Subjective well-being of young people in therapeutic residential care from a gender perspective. Child Indicators Research 15: 249–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffejee, Sadiyya, and Diane Thembekile Levine. 2020. ‘When will I be free’: Lessons from COVID-19 for Child Protection in South Africa. Child Abuse & Neglect 110: 104715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye-Tzadok, Avital, Sun Suk Kim, and Gill Main. 2017. Children’s subjective well-being in relation to gender. What can we learn from dissatisfied children? Children and Youth Services Review 80: 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llosada-Gistau, Joan, Carme Montserrat, and Ferran Casas. 2015. The subjective well-being of adolescents in residential care compared to that of the general population. Children and Youth Services Review 52: 150–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llosada-Gistau, Joan, Ferran Casas, and Carme Montserrat. 2017. What matters in for the subjective well-being of children in care? Child Indicators Research 10: 735–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llosada-Gistau, Joan, Ferran Casas, and Carme Montserrat. 2019. The subjective well-being of children in kinship care. Psicothema 31: 149–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, Mónica, and Jorge Fernández del Valle. 2015. The waiting children: Pathways (and future) of children in long-term residential care. British Journal of Social Work 45: 457–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, Eduardo. 2015. Niños, niñas y adolescentes en acogimiento residencial. Un análisis en función del género [Children and adolescents in residential care. A gender analysis]. Qurriculum 28: 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, Eduardo, Carla González-García, Jorge Fernández del Valle, and Amaia Bravo. 2018. Therapeutic residential care in Spain. Population treated and therapeutic coverage. Child & Family Social Work 23: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montserrat, Carme, and Ferran Casas. 2006. Kinship foster care from the perspective of quality of life: Research on the satisfaction of the stakeholders. Applied Research in Quality of Life 1: 227–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montserrat, Carme, Marta Garcia-Molsosa, Joan Llosada-Gistau, and Rosa Sitjes-Figueras. 2021. The views of children in residential care on the COVID-19 lockdown: Implications for and their well-being and psychosocial intervention. Child Abuse & Neglect 120: 105182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortúzar, Harry, Rafael Miranda, Xavier Oriol, and Carme Montserrat. 2019. Self-control and subjective-wellbeing of adolescents in residential care: The moderator role of experienced happiness and daily-life activities with caregivers. Children and Youth Services Review 98: 125–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, Estrella, Laura López-Romero, Beatriz Domínguez-Álvarez, Paula Villar, and Jose Antonio Gómez-Fraguela. 2020. Testing the effects of COVID-19 confinement in Spanish children: The role of parents’ distress, emotional problems and specific parenting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 6975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, Fabiane, Jorge Sarriera, Livia Bedin, and Carme Montserrat. 2015. Subjective well-being of children in residential care: Comparison between children in institutional care and children living with their families. Psicoperspectivas 14: 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, Julie, Marsha Wood, and Tabitha Newman. 2016. Looked after children and young people in England: Developing measures of subjective well-being. Child Indicators Research 10: 363–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spanish Childhood Observatory [Observatorio de la Infancia]. 2020. Boletín de datos estadísticos de medidas de protección a la infancia. Boletín 22 [Spanish Child Protection Figures. Bulletin 22]. Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social. Available online: https://observatoriodelainfancia.vpsocial.gob.es/productos/pdf/BOLETIN_22_final.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Vallejo-Slocker, Laura, Javier Fresneda, and Miguel Vallejo. 2020. Psychological Wellbeing of Vulnerable Children during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psicothema 32: 501–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittaker, James, Lisa Holmes, Jorge Fernández Del Valle, Frank Ainsworth, Tore Andreassen, James Anglin, and Anat Zeira. 2016. Therapeutic residential Care for Children and Youth: A consensus statement of the international work group on therapeutic residential care. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth 33: 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, Nicole Gilbertson, Amanda Hiles Howard, and Philip Goldman. 2020. Rapid return of children in residential care to family as a result of COVID-19: Scope, challenges, and recommendations. Child Abuse & Neglect 110: 104712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2014 Sample | % | 2020 Sample | % | Total | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | 195 | 53.6% | 116 | 55.8% | 311 | 54.4% |

| Girls | 169 | 46.4% | 92 | 44.2% | 261 | 45.6% |

| Total | 364 | 100.0% | 208 | 100.0% | 572 | 100.0% |

| 2014 | 2020 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low SWB (≤7) | High SWB (>7) | Low SWB (≤7) | High SWB (>7) | |||||

| Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | |

| OLS | 38.5% | 60.4% | 61.5% | 39.6% | 42.2% | 43.5% | 57.8% | 56.5% |

| Satisfaction health | 21.0% | 29.6% | 79.0% | 70.4% | 20.4% | 24.7% | 79.6% | 75.3% |

| Satisfaction with the things you have | 50.3% | 48.5% | 49.7% | 51.5% | 45.0% | 29.2% | 55.0% | 70.8% |

| Satisfaction with safety | 35.4% | 58.6% | 64.6% | 41.4% | 47.6% | 45.9% | 52.4% | 54.1% |

| Satisfaction with what may happen to you later in life | 37.4% | 53.7% | 62.6% | 46.3% | 47.6% | 51.2% | 52.4% | 48.8% |

| Satisfaction with your use of time | 47.2% | 52.7% | 52.8% | 47.3% | 43.6% | 42.7% | 56.4% | 57.3% |

| Satisfaction with friends | 31.4% | 21.3% | 68.6% | 78.7% | 28.4% | 27.3% | 71.6% | 72.7% |

| Satisfaction with the area where you live | 29.5% | 42.2% | 70.5% | 57.8% | 46.8% | 51.7% | 53.2% | 48.3% |

| Satisfaction with classmates | 33.9% | 46.8% | 66.1% | 53.2% | 48.7% | 42.1% | 51.3% | 57.9% |

| Satisfaction with the freedom you have | 56.2% | 63.7% | 43.8% | 36.3% | 58.7% | 57.1% | 41.3% | 42.9% |

| Satisfaction with how adults listen to you | 36.4% | 46.8% | 63.6% | 53.2% | 35.6% | 31.8% | 64.4% | 68.2% |

| 2014 | 2020 | p-Values Comparison for the Two Years | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | p-Value | Boys | Girls | p-Value | Boys | Girls | |

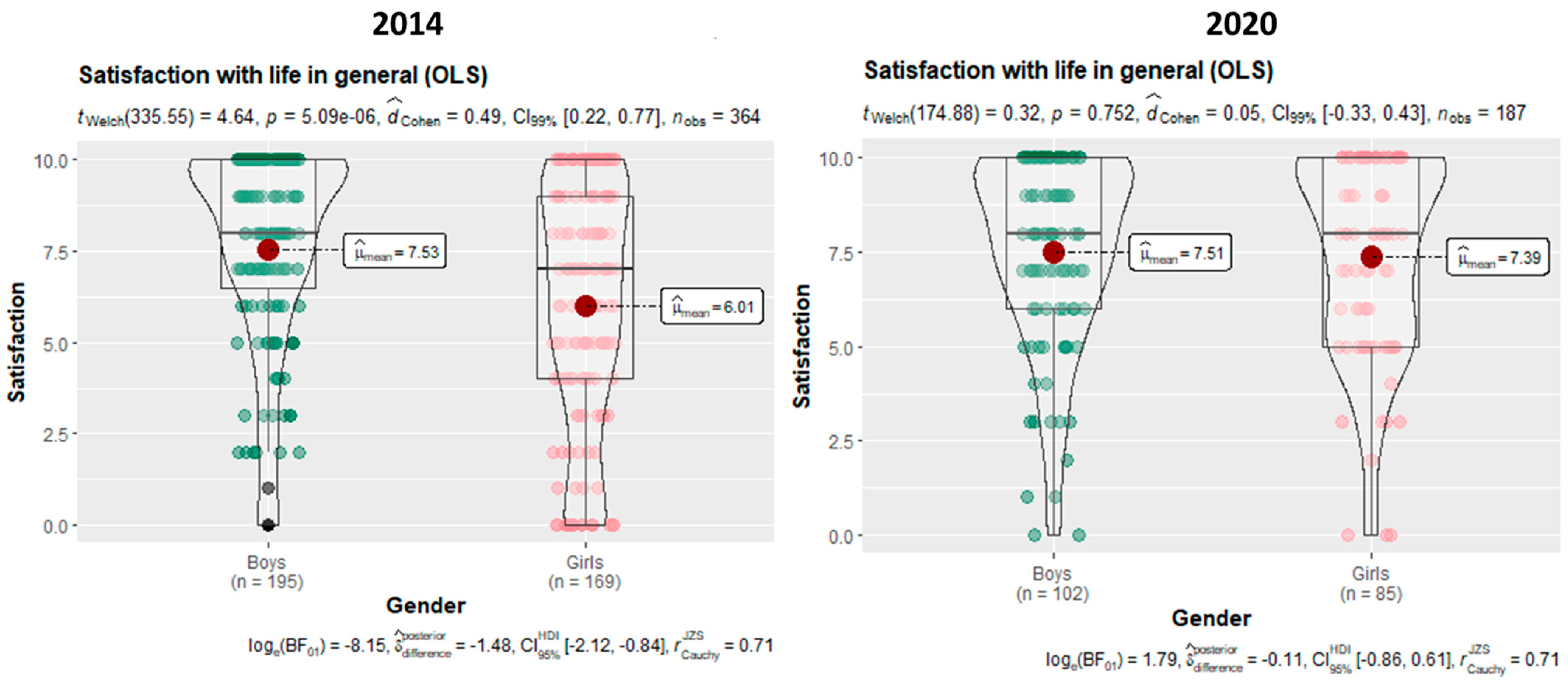

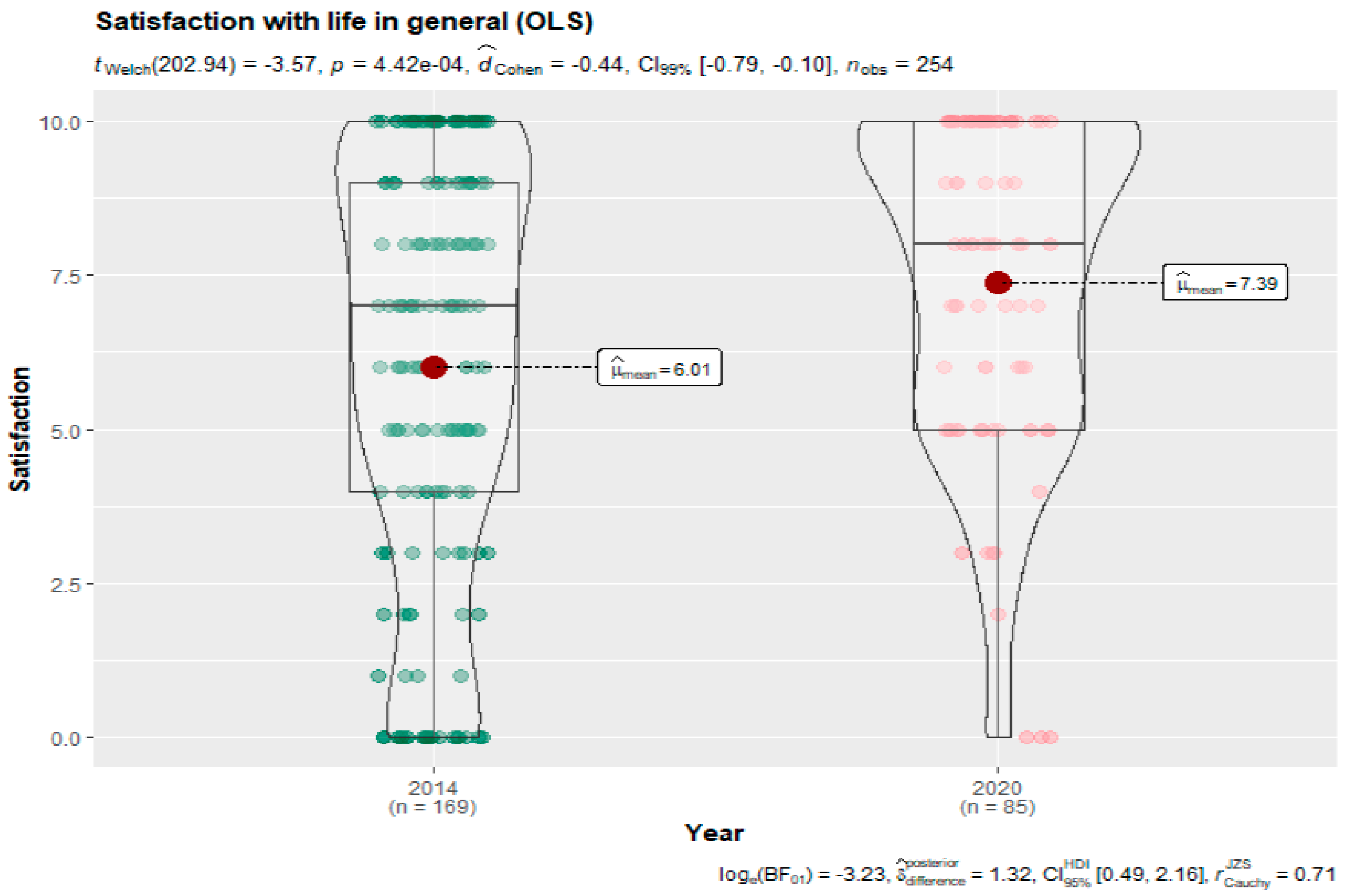

| OLS | 7.53 | 6.01 | p < 0.001 | 7.51 | 7.39 | p = 0.752 | p = 0.955 | p < 0.001 |

| Satisfaction health | 8.82 | 8.16 | p = 0.005 | 8.46 | 8.21 | p = 0.453 | p = 0.150 | p = 0.869 |

| Satisfaction with the things you have | 7.25 | 7.08 | p = 0.537 | 7.80 | 8.30 | p = 0.073 | p = 0.042 | p < 0.001 |

| Satisfaction with safety | 8.06 | 6.70 | p < 0.001 | 7.49 | 7.13 | p = 0.375 | p = 0.049 | p < 0.273 |

| Satisfaction with what may happen to you later in life | 7.78 | 6.75 | p < 0.001 | 7.32 | 7.05 | p = 0.465 | p = 0.135 | p = 0.412 |

| Satisfaction with your use of time | 7.33 | 6.99 | p = 0.204 | 7.72 | 7.72 | p = 0.998 | p = 0.159 | p = 0.009 |

| Satisfaction with friends | 8.20 | 8.53 | p = 0.131 | 8.34 | 7.97 | p = 0.314 | p = 0.555 | p = 0.112 |

| Satisfaction with the area where you live | 8.06 | 7.44 | p = 0.023 | 7.10 | 6.69 | p = 0.357 | p = 0.005 | p = 0.057 |

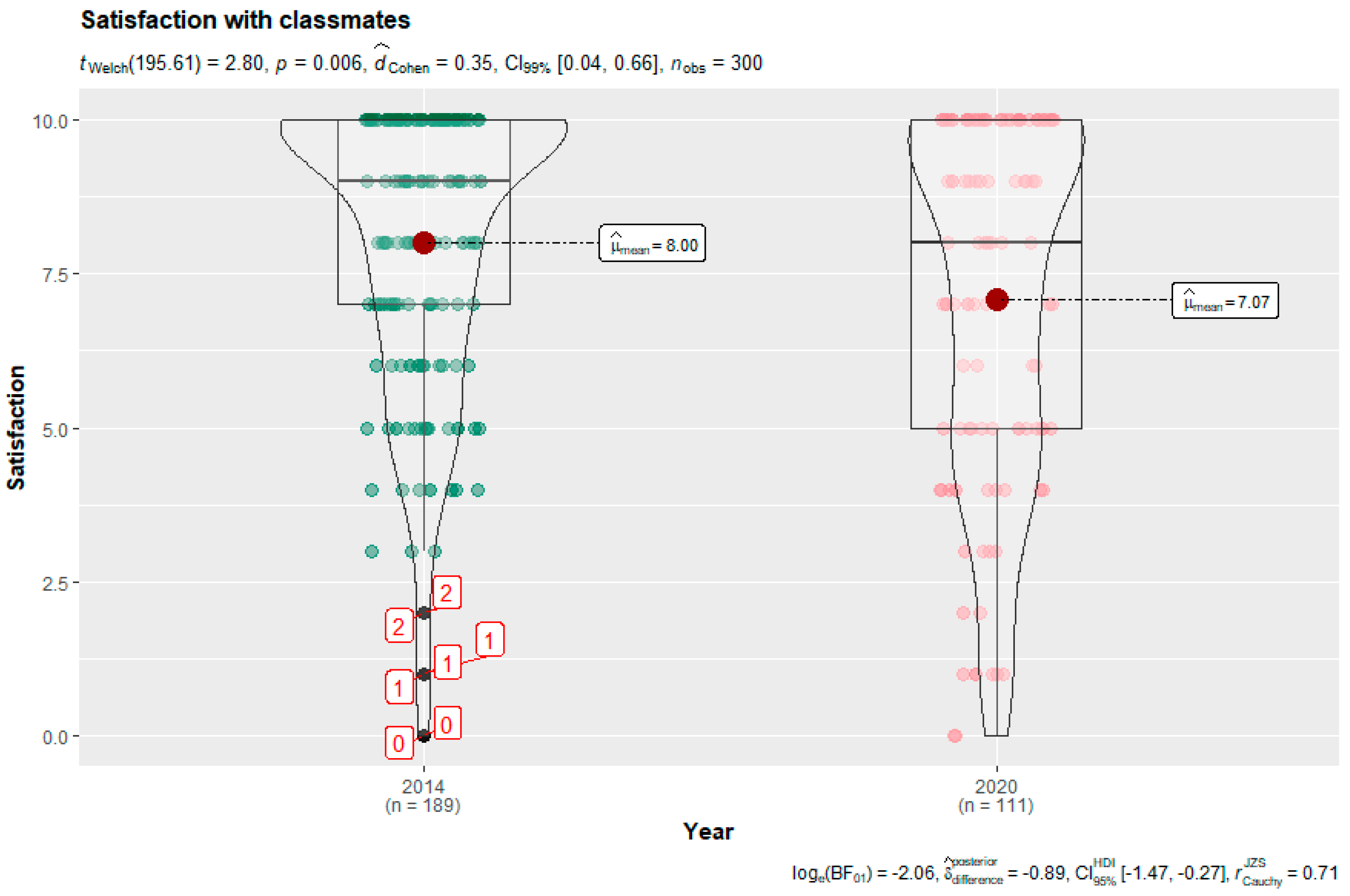

| Satisfaction with classmates | 8.00 | 7.13 | p = 0.002 | 7.07 | 7.28 | p = 0.626 | p = 0.006 | p = 0.695 |

| Satisfaction with the freedom you have | 6.30 | 5.70 | p = 0.085 | 6.46 | 6.62 | p = 0.721 | p = 0.678 | p = 0.028 |

| Satisfaction with how adults listen to you | 7.82 | 7.20 | p = 0.023 | 7.63 | 7.84 | p = 0.574 | p = 0.532 | p = 0.060 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Montserrat, C.; Llosada-Gistau, J.; Garcia-Molsosa, M.; Casas, F. The Subjective Well-Being of Children in Residential Care: Has It Changed in Recent Years? Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11010025

Montserrat C, Llosada-Gistau J, Garcia-Molsosa M, Casas F. The Subjective Well-Being of Children in Residential Care: Has It Changed in Recent Years? Social Sciences. 2022; 11(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleMontserrat, Carme, Joan Llosada-Gistau, Marta Garcia-Molsosa, and Ferran Casas. 2022. "The Subjective Well-Being of Children in Residential Care: Has It Changed in Recent Years?" Social Sciences 11, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11010025

APA StyleMontserrat, C., Llosada-Gistau, J., Garcia-Molsosa, M., & Casas, F. (2022). The Subjective Well-Being of Children in Residential Care: Has It Changed in Recent Years? Social Sciences, 11(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11010025