2. Why Parenting Advice Books?

Baby care advice books were not new to the period studied in this paper. Literate mothers in colonial times in America could avail themselves of publications from England, and by 1800, such books were written and published in the United States (

Ryerson 1961). However, a number of factors came together in the early 20th century to create an increased demand for these publications. Industrialization that began in the 19th century had altered division of labor in families. Continuing urbanization, as families increasingly lived in cities rather than on farms, meant that nuclear families were less likely to live close to extended family; therefore, mothers lacked communal parenting support they might have found in earlier times. By 1900, the percentage of families living on farms had decreased to 40% (compared to 64% in 1850), and this decline continued throughout the period studied to 32% in 1920, 17% in 1950, and 2% by 1980 (

U.S. Census Bureau 2012). Declining infant mortality (

Brosco 1999) also contributed to a changed attitude toward children. In 1800, women gave birth to seven children on average, half of whom did not survive to age five, but by 1900, the average woman had three and a half children, and hoped for each child not only to survive, but to thrive (

Ehrenreich and English 2005).

The early 20th century was a time when the public became increasingly interested in science and impressed by modern ways rather than by tradition. All of these factors helped to create a perceived need for parenting information from experts such as that provided by baby care books. Another factor that helped to create an audience for these books was a trend toward women delivering babies in hospitals, with a decrease in home births from 50% to 15% in the period from 1915 to 1930 alone (

Grant 1998), as these hospitals sent new mothers home with doctor-endorsed baby care publications.

3. Do Parenting Advice Books Reflect the Parenting Practices of the Period?

Historians and other scholars disagree on the extent to which parenting advice publications reflected actual parenting practices. Writing about advice to women over two centuries,

Ehrenreich and English (

2005) assumed that such advice affected behavior, as did developmental child psychologist

Bronfenbrenner (

1961). Bronfenbrenner wrote, specifically about parenting advice publications, “Mothers not only read these books, but [they] take them seriously, and their treatment of the child is affected accordingly.” However, historian

Mechling (

1975) held that child rearing manuals reflected cultural values rather than actual parenting practices.

Grant (

1994,

1998), in a study of mothers’ groups in Upstate New York in the 1920s found that baby care books provided the basis for discussion of child raising practices; however, she also documented “a mixed response” from mothers to the experts’ advice (p. 140). Therefore, while such publications may or may not reflect what parents were actually doing at home, they do provide a window into the past, not a precise record of parenting behavior, but of cultural values and goals. British psychologist and best-selling baby book author

Penelope Leach (

1977) described published parenting advice as “a complex and…entrancing folklore of child care which, once upon a time, you might have received from your own extended family” (p. 26).

4. Methods and Materials

This paper samples “baby books”—printed pamphlets and books from a variety of sources including United States Government publications, pamphlets provided to hospital patients, and popular books from other publishers. Convenience sampling was used in collecting publications for study.

Riffe et al. (

2019) gave three criteria for choosing convenience sampling when studying media, all of which are met in this study: (1) the material is difficult to obtain, a criterion that often applies to older material for which there is no defined census, (2) random sampling is not possible due to resource limitations or the lack of a defined census, and (3) the sample comes from an important but under-researched area. All sources were assessed for documented popularity in the form of sales and readership by parents, university medical school affiliation of the medical doctor authors, publication by well-reputed sources, such as the Parents Association (publishers of

Parents Magazine), or publication and distribution by the United States federal agency the Children’s Bureau, and only those meeting these criteria were studied. The materials cited span the period from the 1890s to the 1980s. Illustrations that appear in this paper were further selected for their status as public domain or noncopyrighted images. These images were primarily published from the 1910s to the 1980s.

The selection of illustrations within the convenience sample followed three steps outlined by

Newbold et al. (

2002) for media content sampling: (1) selection of the type of media—in this study, books and pamphlets; (2) selection of time period—illustrations were found in publications beginning in 1910 and were present in publications throughout the period studied; and (3) sampling of relevant content from within those media. Step three used particularistic sampling, as I chose those items that I believed best illustrated the content being studied and potentially held interest for my audience. An analysis of the illustrations consisted of direct interpretation (

Stake 1995); a method used primarily in case study research. For a more detailed, nonpictorial analysis of some of this literature, see

Atkinson (

2017). The illustrations are organized by parenting practices including infant feeding, toilet training, and daily care, and other topics, such as the government’s role in providing parenting advice literature and prevalent images in the literature, and are presented chronologically within each topic section.

5. “Uncle Sam Will Help You Raise [Your] Baby”

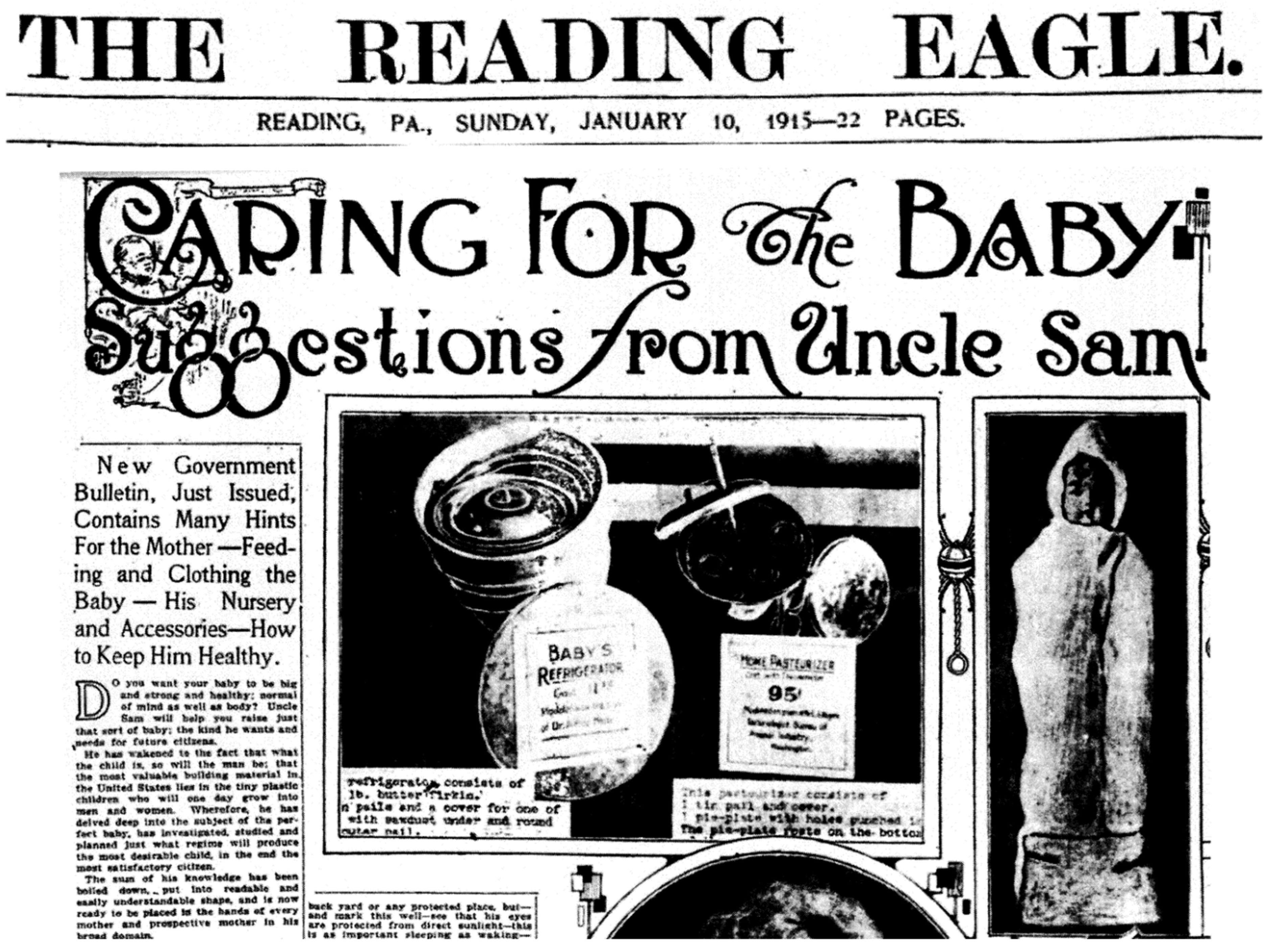

Unlike most baby care books, which were authored by male doctors, Children’s Bureau publications were written by the Bureau’s mostly female staff.

Figure 2 shows a response in the popular press to the new government-issued baby care bulletin. “Do you want your baby to be big and strong and healthy, sound of mind as well as body? Uncle Sam will help you raise just that sort of baby; the kind he wants for future citizens” (

Caring for Baby: Suggestions from Uncle Sam 1915, p. 16).

Infant Care was sold for 10 cents per copy or was distributed free of charge by government agencies, health departments, well-baby clinics, and members of Congress (

Hymes 1978), such as North Carolina Congressman Charles Raper Jonas (see

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

By 1929, the

Infant Care booklet had been sold or distributed to parents of 50% of American infants (

Ladd-Taylor 1986). The publication was revised and reissued periodically through 1989 (

Deavers and Kavanagh 2010).

7. Weaning and Solid Foods for Baby

Prior to 1900, children were given their first solid foods around 1 year of age (

Ryerson 1961). In the early decades of the 20th century, concern about overeating and digestive stress lessened. In the context of aggressive advertising by the baby food industry, doctors recommended starting solid food at much earlier ages. In 1894, Holt advised starting solid food at 10 months, and a Parents Association publication (

Beery 1917) gave a detailed account of an 8 ½-month-old baby’s daily routine with no mention of solid food. By 1925, however, Richardson wrote that “many of the best men” now recommended that mothers “give solid food much earlier in life than used ever to be thought of. According to this new trend, it is now no uncommon thing to begin the feeding of green vegetables, usually spinach, as early as six months of age” (pp. 192–93). Infant mortality rates had dropped overall and, with safer and more reliable milk supply, no longer spiked in the summer, so the “old fear of weaning in the summer” (pp. 198–99) no longer delayed feeding of other foods (

Duffus and Holt 1940).

Figure 11 from the 1935 edition of

Infant Care shows a baby being fed cereal on mother’s lap, now recommended at 5 months.

Spock (

1946) advised giving the baby orange juice at 6 weeks and starting solid foods between 1 and 4 months of age. By age 6 months, the baby should eat regular meals of fruit, vegetables, meat, cereal, and eggs.

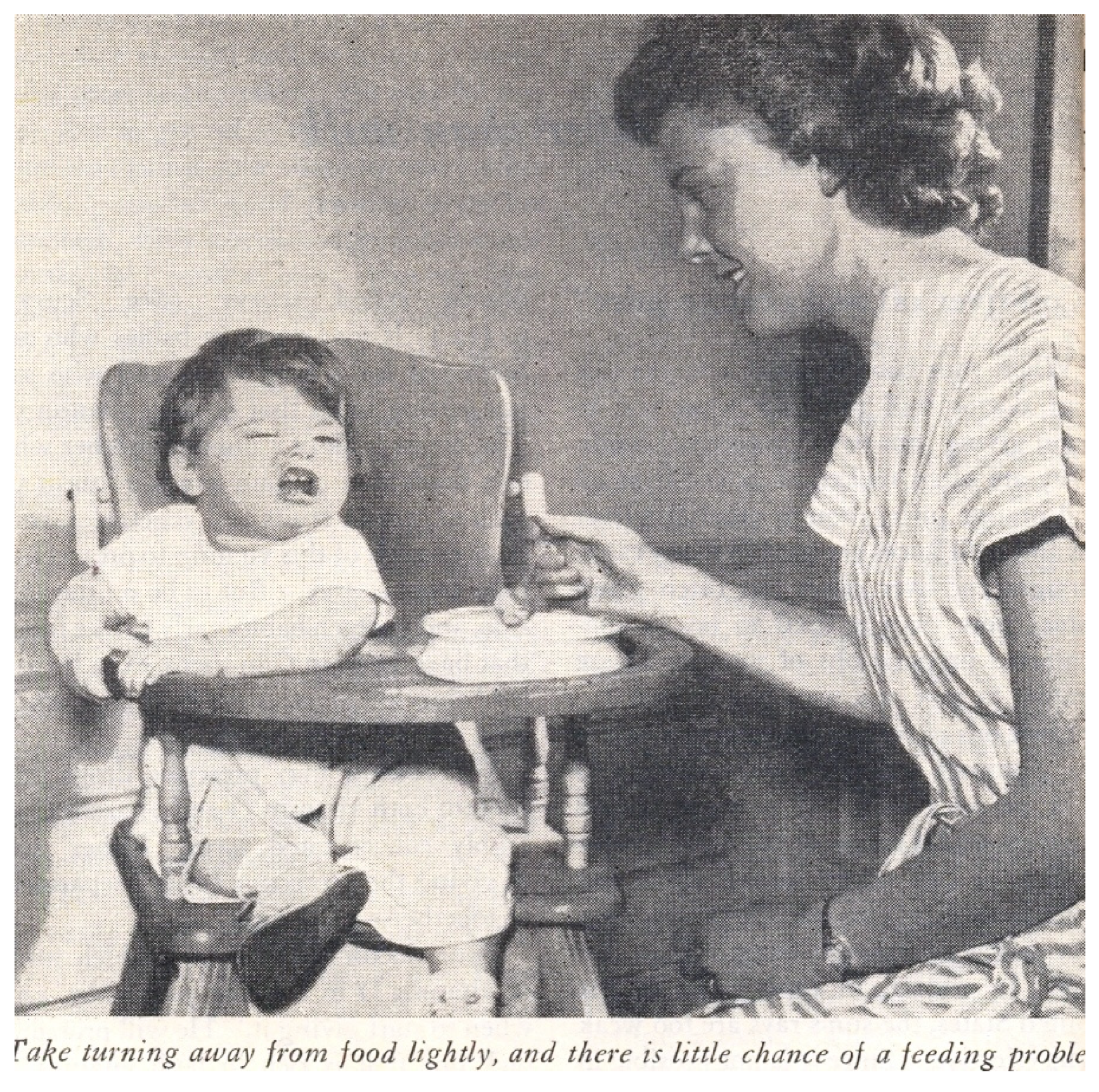

Figure 12 from the 1951 edition of

Infant Care shows baby in a highchair with advice against overreacting to baby’s refusal of food.

Figure 13, from the 1989 edition of

Infant Care, shows baby in highchair ready for a meal.

8. Toilet Training

In the late 19th century, experts instructed mothers in toilet training, beginning as early as 1 month of age. If mothers encouraged regularity, the baby might be bowel-trained by 3 months, stated

Holt (

1894). Other advice books also recommended early, but nonpunitive, toilet training. Pediatrician and professor

Griffith (

1921) recommended that training begin at 3 months, warning, “It need scarcely be remarked that punishment for delinquencies in this line is totally out of the question at any age (pp. 186–87).

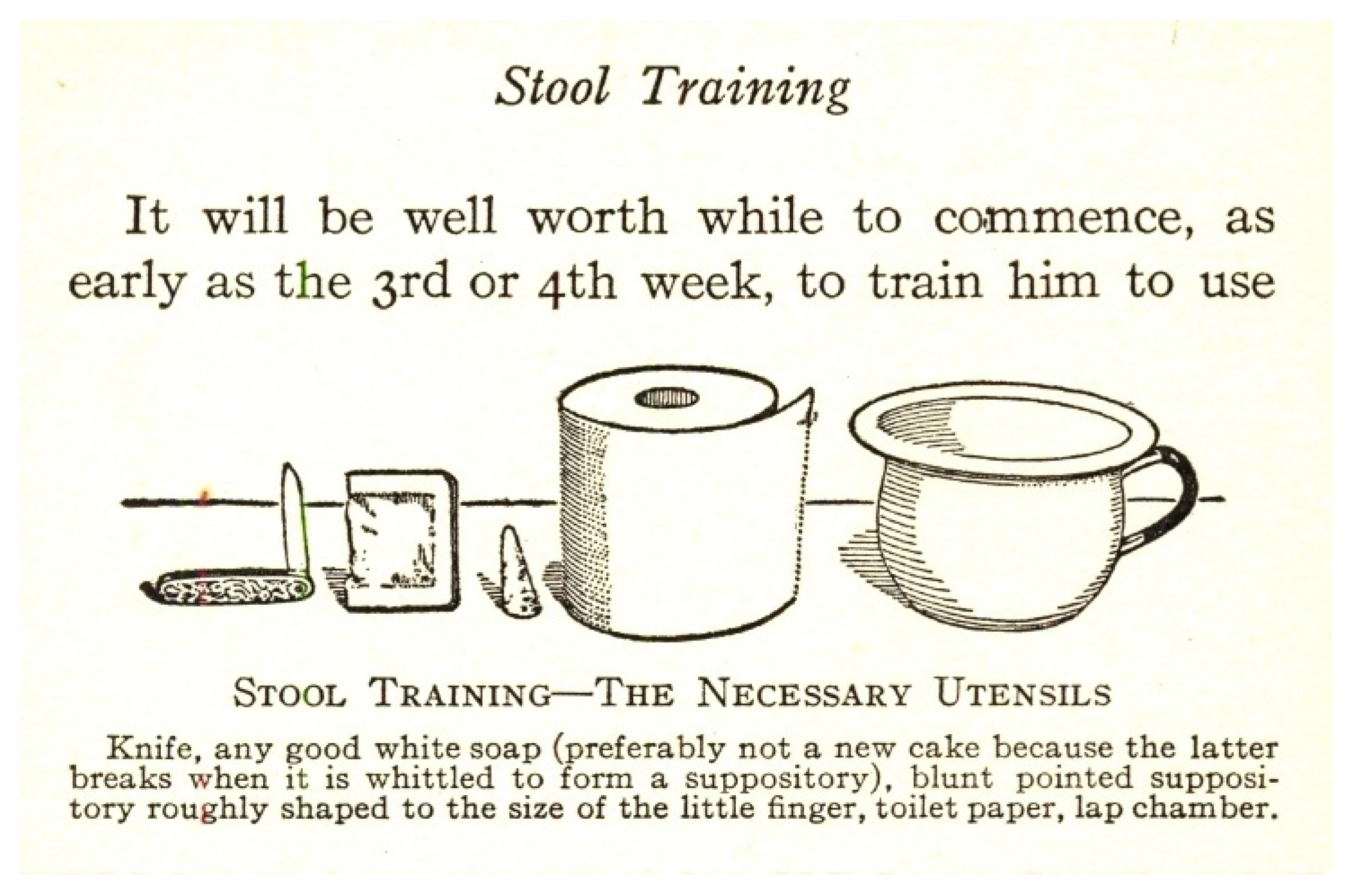

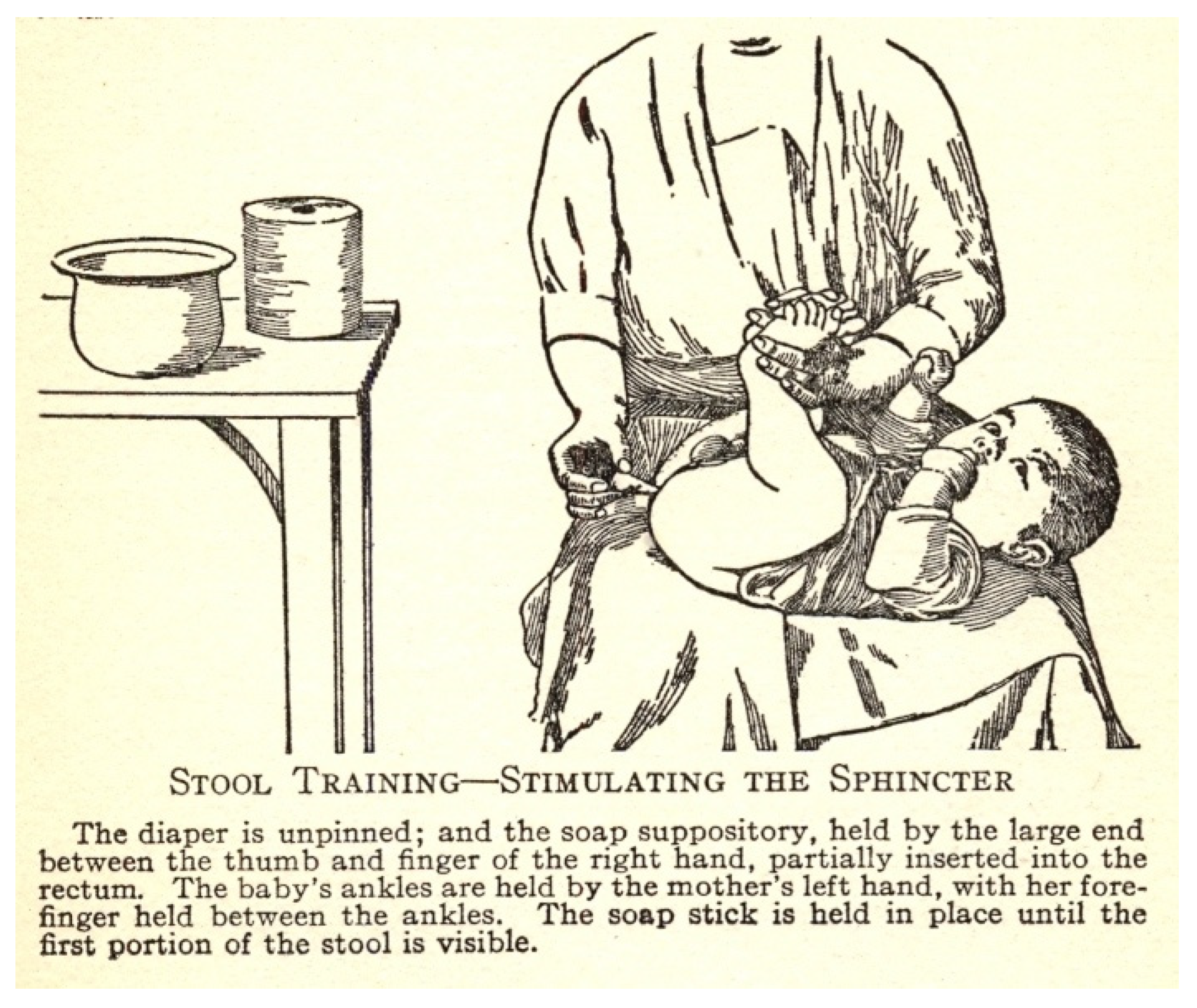

Richardson (

1925) gave detailed, illustrated directions (see

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 17).

Mothers were instructed to use the pictured penknife to whittle a small “stick” out of soap and to “apply the chamber.” “She should lay him on his back across her lap… holding the chamber close up to the buttocks... If, after waiting for a few minutes, the expected stool does not come, she may facilitate matters by inserting the small soap suppository…” (pp. 48–50). The contemporary 1926 U.S. government publication,

Infant Care, advised, “Toilet training may be begun as early as the end of the first month...The first essential in bowel training IS absolute regularity”(

U.S. Department of Labor, Children’s Bureau 1926, p. 42–43).

None of the illustrations (uncredited) in Richardson’s book show the mother’s head.

Mothers were instructed to use the soap suppository if necessary to encourage a timely bowel movement.

By the mid-20th century, toilet training advice had changed considerably. Freudian-trained Dr.

Spock (

1946) urged parents to avoid early and severe toilet training, explaining that “second year possessiveness and balkiness” might actually delay early training efforts. “I don’t think there is any one right time or way to begin toilet training,” he wrote, providing advice on a variety of methods that began between 12 and 24 months (pp. 190–99). The 1951 edition of

Infant Care, similar in tone, advised parents to look for readiness and to focus on “having a baby who feels like working with you instead of against you” (p. 87). The 1962 Children’s Bureau publication,

Your Baby’s First Year, advised letting baby set the pace of toilet training (see

Figure 19), and by 1989,

Infant Care included no mention of toilet training.

Some historians have questioned the Freudian explanation for the change in toilet training timeline advice.

Gordon (

1968) posited the “Maytag hypothesis” (pp. 578–83) that changing technology such as automatic washers and dryers that freed mothers from unpleasant and time-consuming diaper laundering and sterilizing, rather than Freud-inspired expert advice, explained trends toward later toilet training.

9. Fresh Air and Sunshine

“Fresh air is of almost as much importance to the baby as food” (

Fischer 1913, p. 5). Starting with the first edition of his book

The Health-Care of the Baby in 1906, Dr. Fischer, in keeping with his peers, preached the gospel of fresh air as rivaling food in its essentiality. Experts recommended “copious amounts” of fresh air in the baby’s room, day and night (

Bolt 1924), to purify the blood, provide oxygen, and prevent colds and pneumonia. Fresh air was touted as a cure for many ills, and napping in the open air was recommended, not only in warm weather but during the winter as well. This might take place on a porch, or for city apartment dwellers, in a “window crib” or “balcony cot,” a small screened and roofed platform that hung from an apartment window (

Hardyment 1983;

Richardson 1925). In 1923, Emma Read received a patent for such a “baby cage.”

Figure 20 shows a drawing from her patent application.

The 10th edition of Fischer’s book in 1920 included illustrations and an endorsement of the Boggins Window Crib, shown in

Figure 21, which Dr. Fischer assessed “absolutely safe.”

The 1935 edition of

Infant Care encouraged sunbathing for baby in order to acquire a healthy tan, as illustrated in

Figure 23.

10. Sleeping and Playing

While expert advice on infant sleep was given independently of advice related to the role of play, those recommendations varied together over time. Early in the period studied, advice-givers focused on ensuring the maximum amount of sleep, and showed no evidence of valuing the infant’s daytime experiences in terms of play and learning, as control of the baby’s habits took priority (

Atkinson 2017).

The term

co-sleeping (parent(s) and infant sleeping in the same bed) did not appear in printed parenting literature during the period studied. For many centuries, children slept in the parents’ bed until age 2 or older, after which they would share a bed with brothers or sisters (

Ryerson 1961). Separate beds became common during the 19th century; newborn babies still slept with parents and were moved to their own bed by 1 year of age. In 1878, English doctor Chavasse wrote, “Ought a babe to lie alone from the first? Certainly not…he requires the warmth of another person’s body” (

Chavasse 1878, pp. 3–4). However, by 1984, Holt advised, “Should a child sleep in the same bed with his mother or nurse? Under no circumstances … nor should older children sleep together” (p. 50).

Newborn babies were expected to sleep “about nine tenths of the time” and “two thirds of the time” at age 1 year (

Holt 1894, pp. 50–51). Holt recommended putting the baby to bed in a crib, awake, in a darkened room. He cautioned that rocking was “by no means [necessary] and a habit easily acquired, but hard to break and a very useless and sometimes injurious one” (p. 51). Crying, he advised, expanded the lungs, and was “necessary for health. It is the baby’s exercise” (p. 53).

Bolt (

1924) warned that, “It is dangerous for it [baby] to go to sleep in the same bed with [mother]. A number of instances have been reported where a mother has unknowingly rolled over on the baby during a sound sleep” (p. 9), evoking a myth debunked by current research (

McKenna 2000;

McKenna and McDade 2005;

McKenna et al. 2007) but persistent into the current era.

Holt’s recommendations for regulating and training the young baby’s habits contrast with present-day emphasis on the importance of stimulation for intellectual growth. Holt’s advice on playing with a baby was, “The less of it at any time the better for the infant” (p. 57). A Parents Association publication (

Beery 1917), providing a sample daily routine for 8 ½-month-old “Dickey,” assumed a great capacity for the older infant to sleep or to entertain himself for long periods of time, and warned that too much play or excitement might interfere with sleep.

In the 1920s, behavioral psychologist

Watson (

1928) provided a psychological rationale for discouraging touching, cuddling, or rocking a baby to sleep. That advice was similar to Holt’s earlier cautions, though Holt justified his directives with concern for baby’s health and mother’s workload. Watson claimed that too much handling and kissing was detrimental because it would condition children to expect such treatment as they grew up. In particular, a boy might become a “mama’s boy” and expect undue attention and affection from his wife. Watson wrote, “Never hug and kiss them, never let them sit in your lap. If you must, kiss them once on the forehead when they say good night. Shake hands with them in the morning. Give them a pat on the head if they have made an extraordinarily good job of a difficult task” (pp. 81–82).

Watson also viewed excessive handling and attention as a deterrent to an infant exploring and manipulating their environment. This valuing of exploratory play revealed a new perspective on infant development. The contemporary Children’s Bureau’s

Infant Care pamphlet (1926) cautioned, “The rule that parents should not play with the baby may seem hard, but it is no doubt a safe one.” Playpens became popular, advertised as an alternative to too much handling (see

Figure 25;

Trimble 1913).

In the 1940s, psychologist and pediatrician Gesell at Yale University Clinic of Child Development and his associate, pediatrician Frances Ilg, advised mothers, “Don’t watch the clock, watch the child” (

Gesell and Ilg 1943, p. 53). Gesell and Ilg’s schedule for a 9-month-old baby differed from that of earlier writers as they recommended flexible times for sleeping (in the parents’ room, but not in the parents’ bed), waking, and feeding. They described the baby beginning to talk and develop fine motor skills, developmental milestones largely ignored in earlier advice books. Their recommendations validated the baby’s needs and preferences, in contrast to earlier advice-givers who interpreted the baby’s actions as attempts to manipulate caregivers.

Figure 26, from the 1951 edition of

Infant Care, supports the value of play and exploration by the baby.

While earlier experts advised against bath toys as a distraction, the 1951

Infant Care pamphlet described bath time as a pleasurable activity, as seen in

Figure 27.

By 1962, play was valued not only for enjoyment, but also as a learning activity, as shown in

Figure 28 from

Your Baby’s First Year (U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare).

The 1989 edition of

Infant Care also encouraged play, as shown in

Figure 29, encouraging parents to be mindful of safety and aware of developmental changes in the infant.

11. Images of Babies and Families Overwhelmingly White and Middle Class

The stated aim of the Children’s Bureau was to serve “all classes of our people” (

U.S. Department of Commerce and Labor, Children’s Bureau 1912, p. 2); however, while their publications were affordable and widely distributed (

Ladd-Taylor 1986), illustrations showed white, middle-class families exclusively through at least the 1938 edition. Advice books and pamphlets printed by the private sector followed the same pattern. Early publications had no illustrations (

Department of Labor, Children’s Bureau 1914;

Holt 1894). By the 1920s, drawings were often included, and by the mid-20th century, photographs appeared in these publications, though by the 1980s, line drawings again predominated in government publications.

Little research exists on the racial and socioeconomic status of baby book consumers.

Anderson (

1936) found, based on a survey of 3000 American families, that 56.1% of 173 Black parents reported reading at least one book on child rearing in the previous year, in contrast to 49.4% of white parents. Within both groups, parents of higher socioeconomic status read more books than did parents of lower socioeconomic status. Readership of parenting pamphlets was nearly identical across the two groups (65.9% for Black parents and 64.8% for white parents), again with slightly higher readership among parents of higher socioeconomic status in both groups (p. 287). In addition, 78.1% of Black parents and 88.2% of white parents reported reading at least one article on child rearing in a newspaper or magazine (p. 288). Anderson’s findings, though based on a small sample of Black parents, documented nonwhite readership of parenting advice publications, despite the fact that these parents were more likely to have purchased the books they read due to less access to public libraries, a source of reading material included in the survey (p. 287).

Sociologists Robert and Helen Merrell Lynd, in their 1929 landmark study of white residents (95%) of a small Midwestern city,

Middletown, observed growing numbers of new mothers in both working- and middle-class families looking for parenting advice. They noted, “The attitude that child rearing is something not to be taken for granted but to be studied appears in parents of both groups. One cannot talk with Middletown mothers without being continually impressed by the eagerness of many to lay hold of every available resource for help in training their children” (

Lynd and Lynd 1929, p. 149). The Lynds enumerated multiple printed sources, some cited in this paper, and noted, “Parents could not help wondering about the efficacy of traditional child–rearing strategies in a modern era,” (p. 133) as they viewed their own parents’ practices as inadequate for the new generation of children.

Ladd-Taylor (

1986) also documented readership across social classes and reported on mothers’ letters to the Children’s Bureau requesting advice publications, many from women in poverty.

The front cover of the 1926 edition of

Infant Care shown in

Figure 31 (U.S. Department of Labor) shows a white baby of remarkably similar appearance to the one in

Figure 30.

The cover of the 1935 edition of

Infant Care (U.S. Department of Labor) shown in

Figure 32 used a drawing, again a white baby, now with mother.

The 1935 edition of

Infant Care also included recommendations to families for choosing a home, recommending a well-ventilated house with a sunny yard and healthy surroundings (see

Figure 33) without reference to economic or racial barriers to such housing.

The 1951 edition of

Infant Care included some photos of nonwhite parents and babies, as shown in

Figure 34 and

Figure 35. These photos appeared without any race-specific captioning and were the first use of such photos or illustrations in publications reviewed for this paper. (At this time, according to the

U.S. Census Bureau (

1951), 89.7% of the population was white, 9.9% was listed as “Negro,” and less than 1% were listed as “Other.”)

Figure 32 also represents a trend toward picturing more fathers in baby care publications.

The 1962 Children’s Bureau publication,

Your Baby’s First Year, a “short picture leaflet… designed for quick reading,” used cartoon-style line drawings to depict infants and parents. The 1989 final edition of

Infant Care used sketches, clearly multiracial but less distinct than photographs, as shown in

Figure 36 and

Figure 37.

Figure 36 accompanied recommendations for allowing the baby time on the floor to roll, kick, and begin to crawl.

Lack of racial representation prior to 1951 occurred despite apparent diversity in readership. Other gaps existed between the lives of many readers and the suburban and middle-class settings overwhelmingly pictured in parenting literature. These publications rarely mentioned external forces that affected families’ lives, instead implying that solutions to problems and challenges were to be found in behavior change by parents (

Atkinson 2017).

12. Conclusions

This look through the window of baby care books at parenting advice and practices of the past yielded interesting, puzzling, and even head-shaking ideas and illustrations. It was, indeed, an “entrancing look at “the folklore of child care” (

Leach 1977, p. 26). However, along with fascinating pictures and descriptions of quaint parenting practices is another story, of the increased revering of all things scientific, and of the rise of experts, who stepped in with advice when grandma could not.

The publications highlighted in this paper met American parents’ perceived need for expert advice in an era of increasing specialization and scientific study. Much of that advice changed over the years; in fact, there were many changes over a relatively short time period. In some cases, this reflected new scientific knowledge. For example, as scientists and health professionals learned about the dangers of lead, lead nipple shields fell out of favor with experts. Likewise, advice shaped by serious concern about infant mortality due to contagious disease or contaminated milk changed when immunizations and pasteurization became widely available (

U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Office of Child Development 1977, p. 29). New research about the danger of overexposure to sun also led to changes in recommendations.

However, much of the experts’ changing advice was not based on new scientific knowledge. Despite the Archimedean tone of the advice, no underlying basis in empirical science supported many of these recommendations. Infant anatomy and physiology and the timelines of child growth and development did not change over the short span of years covered in this paper; however, experts’ advice on infant care and feeding, presented to parents as scientific and universal, changed considerably over that same period. That advice was informed as much by the experts’ opinion of what American families should look like as by scientific findings (

Atkinson 2017).

In less than a century, infant feeding recommendations transformed from rigidly scheduled feedings, whether breast or bottle, to “demand” feedings based on the baby’s hunger. Mothers were advised to introduce solid foods at increasingly earlier ages; over a 60-year time span, the recommended age for starting solid foods decreased from 12 months to 1 month by the mid-20th century, only to be reversed somewhat in recent years. Over the same period, the recommended age for initiating toilet training changed even more dramatically, though in the opposite direction, from 1 month to 2 or even 3 years of age. Expert recommendations for babies’ sleep habits changed from scheduled naps and nighttime sleep that might require a period of crying prior to sleep, to a more flexible “baby led” schedule. As experts came to value play and stimulation over maximizing the amount of baby’s sleep, these changing sleep recommendations were accompanied by corresponding recommended changes in daytime practices. At the same time, the dominant characterization of the baby (along with a pronoun change from “it’ to “he”;

O’Conner and Kellerman 2009;

Tieken-Boon van Ostade 2000) changed from a manipulative creature to a developing person with legitimate needs and preferences (

Atkinson 2017). Experts’ recommendations, in fact, reflected changing patterns of thought in middle-class society rather than an empirical body of knowledge that stood over time (

Clark 1951;

McKenna 2000), belying the absolutism of the experts’ advice.

13. My Story

I was a new mother in the 1980s, at home with a confounding, challenging small baby, wondering why my extensive child development background and the support of family and friends were not enough to make me feel confident and encouraged. I turned, as many parents do, to books written to advise and guide parents, primarily mothers, through those challenging early weeks and months filled with sleep deprivation, confusion, and angst. I found some useful information and reassurance, but also many doubtful ideas and much advice that raised more questions than it answered.

I wondered whether the parenting practices recommended so unequivocally by the experts of the 1980s were the universal truths they purported to be. Did they hold up historically and cross culturally? In the little time I could carve out of my day (actually late at night), I began to search and read. I found that over the years, a wide range of often-contradictory practices had been recommended to parents with just as much certainty. I began to collect old “baby books”—pamphlets distributed by birthing hospitals, government publications, and old copies of Dr. Spock’s books. Some years later, I researched the stories behind the items in my collection and those in other advice books for parents. Confirming my earlier, sleep-deprived suspicion, I found that the experts were influenced not only by professional knowledge of the needs of the baby and family, but also by the social and cultural environment in which they lived and wrote.

14. Relevance for Parenting in the 21st Century

Now, in the 21st century, the books and pamphlets cited in this paper, with their captivating illustrations, may seem merely an interesting curiosity. We may be amused, or horrified, or feel satisfaction that we know better now what promotes healthy infant growth and development than did those writers. Indeed, the parental advice-giving profession in the years studied was male dominated, classist, racist, and inconsistent, however we might allow for the fact that the content and style of the books reflected the times in which those people lived and wrote.

At its best, parental advice literature serves an important function in bridging the gap between those who study children and parents who might benefit from information and insights from the field of child development. “What’s the use of obtaining fascinating information about bed-wetting if you don’t pass it on to the people who wash the sheets?” asked baby book author

Penelope Leach (

1977).

Of course, many things have changed since the period studied in this paper. The role of women has undergone dramatic change, the rate of maternal employment has increased, and child-rearing literature has also changed. Beginning in the 1970s, more baby books were written by women and nonphysicians. British psychologist Penelope Leach’s

Your Baby and Child: From Birth to Age Five, published in 1977, sold over two million copies. The best-selling

What to Expect… series of books on pregnancy and early child care (

Murkoff et al. 2014) are authored by a female medical writer.

Sources of parenting advice are many. Parents can avail themselves of websites, some hosted by popular baby book authors, and can search the internet for answers to questions that arise. Parents can obtain and share information on social networking sites, in a trend toward information sharing rather than a one-way flow from expert to mother. This abundance of sources allows for specialization—information for parents of children with special needs and parents in special situations.

However, baby care books continue to have a role. “The classics still do well,” commented a local bookstore clerk, when I asked about preferences of today’s parents. A 10th edition of

Dr. Spock’s Baby and Child Care (

Spock and Needlman 2018), advertised as “timeless yet up-to-date,” with “the latest information on child development from birth through adolescence—including cutting-edge research on topics as crucial as immunizations, screen-time, childhood obesity, environmental health, and more” (

Spock and Rothenberg 2018) shares the shelves with newer books. Among these are books from a popular series first published in 1992 by William and Martha Sears, medical professionals and parents of eight children, who describe their

The Baby Book (

Sears and Sears 2013) as “the ‘baby bible’ of the post Dr. Spock generations.” The Sears books support “attachment parenting” practices such as extended breastfeeding and co-sleeping, both highly disapproved by the experts cited in this paper. Specialized books advise parents of children with special needs, such as autism. There are books about raising an only child, being a single parent, gay or lesbian parent, older parent, or custodial grandparent, raising an adopted child, raising a boy, raising a girl, and raising children in the digital age, as well as books targeted to fathers.

Black parents are finally represented on the baby book shelves as well.

The Black Parenting Book: Caring for Our Children in the First Five Years (

Beal et al. 1998) was published in 1999. “I am glad that someone created a book for black parents with pictures of African-American people nursing and caring for their children,” commented a reader reviewer (

The Black Parenting Book 1998) who clearly would have viewed the parenting literature of the early 20th century with less enthusiasm or identification. Parenting books are also available online and in digital format for reading on a variety of handheld devices, blurring the line between books and online content.

The lesson I learned as a young mother reading old baby books was that parenting advice, however decisively prescribed, deserved scrutiny rather than unqualified acceptance. That same lesson can be applied to the consumption of current advice, printed or online, written or illustrated, professionally sourced or peer-shared. “Trust yourself. You know more than you think” wrote Dr.

Spock (

1946, p. 3), despite his abundance of decisive advice.

In the end, published recommendations, along with well-meaning advice from older generations and from friends and acquaintances, all resonate when parents make child-rearing decisions. Gaining a historical perspective, such as that presented in this paper, decreases the certainty that printed materials exude, as parents of young children continue to make the best decisions they can with imperfect input and knowledge.