Abstract

Living in today’s complex social world can contribute to the development of a multi-faceted personal identity and to the risk of identity dispersion. This study focused on values, which are conceptualised as the core of one’s personal identity. It aimed to explore the within-person value consistency across relational roles (i.e., relationships with parents, partners, and friends) and to analyse the association between value consistency, self-concept clarity, and basic psychological needs satisfaction. One hundred ninety-five Italian young adults (F = 85%; Mage = 26.65, SD = 3.83) participated in the study. They completed the Values in Context Questionnaire, the Self-Concept Clarity Scale, and the satisfaction subscale from the Basic Needs Satisfaction and Frustration Scale. Findings showed high value consistencies across the relational roles. Specifically, consistency is higher when values as a partner and values as a friend are considered. Moreover, the relation between value consistency and basic psychological needs satisfaction was fully mediated by self-concept clarity. Limitations of the study, future research developments, and practical implications of the results are discussed.

1. Introduction

In our society, people increasingly belong to several social groups and interact with others within many different relational contexts; each context enhances a set of beliefs, norms, and practices by shaping what is considered right or not within that specific group or context (Daniel et al. 2012a; Roccas and Brewer 2002; Stets and Burke 2003). In this complex social scenario, people, especially young adults, are asked to efficiently adapt to the ever-changing environmental demands (Daniel et al. 2012a). For example, nowadays youths are faced with varied and unpredictable professional careers (Nagy et al. 2019) and have to deal with more and more flexible intimate relationships, such as long-distance relationships (Firmin et al. 2013) or relationships in which partners are cohabiting without being married (Vespa 2014). In addition, compared to the past, the parent–offspring relationship is characterised by less defined parenting roles, with parents often being perceived as “special friends” by their children (Castiglioni 2018).

Experiencing multiple relational contexts (e.g., relationships with parents, partners, and friends) might convey different principles and behavioural standards that are likely to become part of personal identity (Hofstede 2001; Klimstra and van Doeselaar 2017; Rohan 2000). As is known, human identity (at least in part) comes from interactions with significant others within social and relational contexts (Baumeister 2010; Cooley 1992). Indeed, people’s self-attributes are the result of a multiple-context-dependent selves (McConnell 2010; McConnell et al. 2012); if different contexts are characterised by diverging ideas and communications, a multi-faceted—and even conflicting—set of meanings, values, and beliefs can coexist within the same person (Renedo and Jovchelovitch 2007; Wagner 2007; Wagner et al. 2000). People are therefore asked to balance two competing cognitive forces, namely differentiation and coherence. On the one hand, they should adapt to the changeable contextual demands (differentiation), and on the other, they have a natural propensity for consistency in their life (coherence; Daniel et al. 2012b). In doing so, two opposite mental states are possible: cognitive dissonance vs. cognitive polyphasia (Martinez 2018). The first one refers to a mental state in which contradictory cognitions may cause maladjustment, because people need to maintain an inner cognitive coherence (Festinger 1962). The second one refers instead to a mental state in which a different set of knowledge may adaptively coexist within the same person (Provencher 2011; Renedo and Jovchelovitch 2007). As such, cognitive polyphasia leads to self-concept differentiation, namely the individual’s tendency to perceive his or her own self-representations (e.g., personality traits and beliefs) as varying across social roles and contexts (e.g., as a family member or a friend) (Diehl et al. 2001; Donahue et al. 1993; Styla et al. 2010). The prior theories and speculations on the topic were largely consistent in stating that self-concept differentiation is an adaptive response to the different needs of the various social contexts and roles (e.g., Gergen 1972; Snyder 1974), leading to a specialized and flexible self. However, later empirical research highlighted that self-differentiation might represent a source of discomfort (Campbell et al. 2003), resulting, for example, in high levels of negative emotions (Showers and Kling 1996; Simon et al. 2019), poor adjustment (Showers et al. 2006), and low levels of both self-esteem and wellbeing (Diehl and Hay 2011; Fukushima and Hosoe 2011). As such, these findings supported the hypothesis that self-concept differentiation might lead to a fragmented self, namely a self in which there is a lack of a clear identity structure (Block 1961; Sheldon et al. 1997). On the contrary, reaching a certainty in self-attributes represents a promotional factor in order to achieve a sense of control regarding future outcomes and a sense of self-confidence (Baumgardner 1990).

In order to better understand these results, it is possible to lean on the most important theoretical framework within the study of identity. According to Erikson (1968) and Rogers (1959), psychological well-being is characterised by a coherent self-concept and by a sense of continuity in one’s own biography over time and situations. Differently from adolescence, when identity formation represents a core developmental task characterised by exploration and re-negotiation of self-aspects, during emerging and young adulthood it is essential to reach a more stable identity, characterised by persistence in terms of values, beliefs and commitments. By early adulthood, people have to face the developmental challenge of coordinating multiple facets of the self into a coherent and stable identity (Harter and Monsour 1992). Conversely, the failure to achieve of this developmental task leads to identity diffusion (Block 1961; Campbell et al. 2003; Pilarska and Suchańska 2015). In line with all this, more recently Crocetti et al. (2012) and Luyckx et al. (2006) pointed out that the achievement of a stable identity during young adulthood was associated with the satisfaction of the basic psychological needs of competence, relatedness, and autonomy. Coherently, several previous studies pointed out that a stable sense of identity, as well as identity commitment, is positively associated with self-concept clarity (Bigler et al. 2001; Crocetti et al. 2008; Pilarska and Suchańska 2015).

Self-concept clarity is conceptualised as the consistency of personality attributes across different social roles and contexts that gives coherence to the individual identity (Baumgardner 1990; Campbell 1990; Campbell et al. 1996). Several studies supported the link between self-concept clarity and positive outcomes, such as autonomy (Diehl and Hay 2011), emotional stability (Campbell et al. 2003), positive relationships (Lewandowski et al. 2010; Parise et al. 2019; Ritchie et al. 2011), wellbeing (Bigler et al. 2001; Hanley and Garland 2017; Slotter et al. 2010), self-efficacy, and motivation (Thomas and Gadbois 2007).

Thus, considering these findings, it seems that holding a stable and coherent identity represents an important protective and promotive factor. In the present study, we focused on the core of personal identity: personal values (Hitlin 2003).

1.1. Personal Values

Personal values are defined as guiding principles of what people consider worthy in their lives and, as such, they are a central aspect of personal identity (Barni 2009; Hitlin 2003; Hitlin and Piliavin 2004). Although people develop their values priorities within social contexts, they are not perceived as coerced aspects of the self or externally binding, but as ideals worthy of commitment. As such, values are intrinsically desirable (Hitlin 2003). In other words, although values are socially shaped, they are personally experienced. We depict ourselves according to our values, and this allows us to feel a sense of authenticity (Hitlin 2011).

The most well-known psychosocial theory of values is the Theory of Basic Human Values developed by Schwartz (1992). This theory suggests the existence of ten basic values that underline and express different motivational goals and are related to each other. The relationships among basic values can be organised into a circular structure (Schwartz 1992, 2005, 2012). Values placed close to each other share similar motivational goals (e.g., benevolence and universalism), while values located far away from each other pursue conflicting motivational goals (e.g., benevolence and power). Based on these relationships, values can also be organised into four higher-order categories, also systematised along with two-dimensional structures. The first-dimension contrasts conservation values (tradition, security, conformity), which enhance the importance of self-restraint, traditional practices, and safeguarding of stability, with openness to change values (stimulation, self-direction, hedonism), which emphasise the importance of change, independence, and freedom in thinking and actions. The second dimension portrays the conflict between self-enhancement values (power and achievement), which emphasise the pursuit of one’s interest, success, and dominance over others, vs. self-transcendence values (universalism and benevolence), which emphasise concern for the welfare and interests of others and transcend one’s own selfish needs.

According to Schwartz (1992), values and their dynamic relationships hold three main characteristics: they are universally recognised, relatively stable across time, and trans-situational. In other words, people from all cultures are familiar with these values, even if the importance given to each one might change based on the social and cultural context in which the person lives. Moreover, the importance people ascribe to values tends to be quite stable and to endure through time. Finally, since values are conceptualised as abstract goals, they apply to several distinct situations, and their importance tends to transcend the specific circumstance (Hitlin and Piliavin 2004; Rohan 2000). Nevertheless, as highlighted above, situations and contexts can meaningfully differ in the priorities that they enhance. Indeed, recent evidence highlighted that sometimes values stability can be challenged because of external pressures (Arieli et al. 2014; Naveh-Kedem and Sverdlik 2019). However, little research has been conducted so far to investigate the possibility of spontaneous within-person value differentiation or value consistency across contexts, probably because of the abstract nature of values and their assumed tendency to stability. Only recently, Daniel and her colleagues (Daniel et al. 2012a; Daniel and Crabtree 2014; Daniel et al. 2016) empirically showed that the importance that people, specifically adolescents and young adults, give to values might slightly differ in ratings based on the salient context or role. They also showed that value differentiation is usually related to low levels of adjustment and well-being (Daniel et al. 2016; Daniel and Crabtree 2014). In a first study, Daniel et al. (2012a) involved a group of adolescents from four cultural groups (i.e., German adolescents, adolescents born in Germany from immigrant parents, Israeli adolescents, and adolescents born in Israel from immigrant parents) who were asked to rate their value priorities in the context of family, school, and country of residence. The authors found that values varied in importance across the contexts. Specifically, results highlighted that for all the adolescents, benevolence was the most important value in the family and country contexts, while achievement was the most important value in the school context. Moreover, immigrant adolescents showed higher levels of value differentiation than non-immigrant peers. In a further study, Daniel and Crabtree (2014) found that value differentiation was related to low levels of satisfaction with life among heterosexual adults. Specifically, a group of homosexual and heterosexual university students were asked to rate their value priorities in several roles or contexts (e.g., family member, friend, and student). Results highlighted that value differed similarly among heterosexual and homosexual students. For instance, benevolence values were rated as more important as a friend, while conformity values were more strongly emphasised as a student. However, this differentiation led to low levels of wellbeing only for heterosexual participants. According to the authors (Daniel and Crabtree 2014), these findings could be explained in the light of the negative consequences of cognitive polyphasia. If relevant self-attributes like personal values are questioned, cognitive polyphasia might lead to a sense of fragmentation. However, in the case of homosexual orientation, a high level of differentiation might be required due to the social circumstances. Indeed, homosexuality might be accepted to different degrees across the various life-contexts; consequently, if these contexts are perceived as significant and important for individuals, it may functionally lead to different value priorities across them (Daniel and Crabtree 2014). In line with these findings, Daniel et al. (2016) also showed that value differentiation was related to low levels of self-esteem in a group of adolescents from three cultural groups (i.e., Israelis, Former Soviet Union immigrants to Israel, and Arab citizens of Israel). Finally, in another study, Daniel et al. (2012b) investigated the relative consistency of values across various contexts (i.e., school, family, country) in a group of adolescents. Results showed that adolescents’ value priorities remained relatively stable across all the contexts. Specifically, values across the contexts were positively and moderately related among them, showing that adolescents tended to prioritize the same values regardless of the context. The authors speculated that value consistency preserves a sense of inner stability and meaning in adolescents, making it possible to be relatively coherent despite the various external pressures, and invited future studies to focus on the relationship between value consistency and positive outcomes.

Based on the above empirical results, it remains unclear the extent to which value consistency is positively related to individual adjustment and wellbeing, and it is also not clear which mechanisms underlie this relationship. Moreover, since all the previous empirical studies mainly focused on adolescents (Daniel et al. 2012a, 2012b, 2016), it would be important to extend the attention to further phases of the life cycle, such as young adulthood. On one hand, as already mentioned, young adults have to deal with several changes and transitions, assuming new social roles with the related responsibilities (Erikson 1968; Schoon and Silbereisen 2017). As such, this life cycle phase might result in a period of uncertainty and destabilising feelings. On the other hand, young adulthood is a life period in which the value system should be more stable compared to adolescence (Daniel and Benish-Weisman 2019; Vecchione et al. 2019).

1.2. The Present Study

This study addressed two main aims, namely:

- To explore the intraindividual value consistency across relevant relational roles (i.e., relationships with parents, friends, and partners) in a group of Italian young adults. Family relationships, friendships, and romantic relationships are among the most significant relationships in individuals’ development and lives (Clark and Graham 2005; Demir 2010);

- To analyse the relationships between value consistency, self-concept clarity, and the satisfaction of psychological needs, namely autonomy (volition and freedom in choice and actions), competence (the feelings of self-efficacy in pursuing desired outcomes), and relatedness (the feeling of being accepted and loved). According to the Basic Psychological Need Theory (BPNT), one of the six mini-theories within the Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Deci and Ryan 2000; Ryan and Deci 2017), these basic psychological needs are prerequisites of human growth that allow reaching an endured hedonic and eudemonic wellbeing (Deci and Ryan 2000; Ryan and Deci 2017). Indeed, several studies highlighted that basic psychological needs satisfaction was related to high levels of both psychological and physical wellbeing (Campbell et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2015a; Quested et al. 2018), and to greater relational satisfaction and vitality (Brenning et al. 2015). Specifically, we aimed to investigate the mediating role of self-concept clarity in the relationship between value consistency and basic psychological needs satisfaction.

Our study’s hypotheses were the following:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

we expected to find a positive association among all the study’s variables Based on the literature, which pointed out a positive association between a stable identity and the satisfaction of basic psychological needs (Crocetti et al. 2012; Luyckx et al. 2006) and a negative relationship between value differentiation and positive outcomes (i.e., satisfaction with life, Daniel and Crabtree 2014; self-esteem, Daniel et al. 2016), we hypothesised that value consistency should be positively associated with the satisfaction of basic psychological needs. Moreover, since values are an essential part to our identity (Hitlin and Piliavin 2004), value consistency should be positively related to the experience of internal integrity (Daniel et al. 2016). Finally, since previous studies highlighted a positive link between self-concept clarity and several positive outcomes, such as relationship quality (Lewandowski et al. 2010), volitional functioning (Diehl and Hay 2011), and motivation in learning (Thomas and Gadbois 2007), we expected a positive association between it and the satisfaction of basic psychological needs.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

we expected that self-concept clarity could mediate the relationship between value consistency and basic psychological needs satisfaction. Indeed, previous findings pointed out that self-concept clarity acts as mediators between individual factors (i.e., dispositional mindfulness, stress, and cultural identity) and positive outcomes (Hanley and Garland 2017; Ritchie et al. 2011; Usborne and Taylor 2010).

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

Participants were 195 young adults (85% females)1, aged from 18 to 35 years (M = 26.65, SD = 3.83). Since the inclusion criteria for participating in the study was to be engaged in an intimate relationship, all the participants had a romantic relationship, which had lasted more than one year (88.9%). They were born in Italy and were currently living in South (27.9%), Central (41.6%), or North Italy (30.5%). Most of them had a bachelor’s degree (71.3%).

All participants gave their written informed consent prior to inclusion in the study. They were asked to complete an online self-report and anonymous questionnaire, in which the careless responding bias was controlled (Ward and Meade 2018)2. The study followed the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its latest version and the APA ethical guidelines. Moreover, the main researcher of this study had previously completed the National Institute for Health training course ‘Protecting Human Research Participants’ (Certification Number:2868994).

2.2. Measures

Values in roles. In order to measure the value importance across the relational roles, we used the Values in Context Questionnaire (VICQ; Daniel et al. 2012a). The VICQ is an adaptation to life contexts and roles of the Schwartz Value Survey (SVS; Schwartz 1992). As such, the scale measures the values conceptualised according to the Theory of Basic Human Values (Schwartz 1992). The VICQ considers the following personal values: competence, ambition, success, honesty, helpfulness, forgiveness, obedience, politeness, self-discipline, curiosity, creativity, and freedom. Participants were asked to rate the importance of each value in referring to a specific role on a response-scale ranging from 1 (not at all important to me) to 6 (very important to me). In the present study, the reference contexts were the relationship (a) with parents, (b) with friends, (c) with their partner. Item examples are: “As a son/daughter (or as a friend or as a partner) it is important to me to be capable” and “As a son/daughter (or as a friend or as a partner) it is important to me to be creative/have new ideas”. To ensure that all the relational roles were relevant to the participants’ identity, we preliminarily measured the centrality of the son/daughter, friend, and partner relational roles to their identity using three items extracted from the Social Identification Questionnaire (Roccas et al. 2008), adapted to the relational roles taken into account in the present study (nine items in total; for more details see Benish-Weisman et al. 2015; Daniel et al. 2016). Participants were asked to rate their agreement with each item on a 6-points Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 6 = strongly agree). Respondents score on all relational roles on average above the middle score of the response scale (Mson/daughter = 4.62, SD = 1.04; Mfriend = 5.21, SD = 0.78; Mpartner = 4.87, SD = 1.03).

Self-concept clarity. We used the Self-Concept Clarity Scale (SCCS; Campbell et al. 1996; Italian validation by Scalas et al. 2013) to measure self-concept clarity. The scale is composed of 12 items, ranging from 1 (“disagree very much”) to 6 (“agree very much”), and it measures the extent to which respondents perceive stability and consistency in their self-concept. Except for items 6 and 11, all the items were reversed. An example of an item is: “My beliefs about myself often conflict with one another”. The total score was obtained by summing all the items, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of clarity of self-concept (α = 0.88).

Basic psychological needs satisfaction. To assess basic psychological needs satisfaction, we used the satisfaction subscales from The Basic Needs Satisfaction and Frustration Scale (Chen et al. 2015b; Costa et al. 2018). The satisfaction subscale is composed of three 4-items dimensions, ranging from 1 (“not true at all”) to 5 (“completely true”). Item examples are: “I feel a sense of choice and freedom in the things I undertake” (autonomy subscale; α = 0.91), “I feel that the people I care about also care about me” (relatedness subscale; α = 0.81), and “I feel confident that I can do things well” (competence subscale; α = 0.82). The total score was obtained by summing all the items, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of basic psychological needs satisfaction (α = 0.86).

2.3. Data Analysis

Value consistency. We adopted the procedure of dyadic correlations as previously done by several works (see, for example, Boehnke et al. 2007; Danioni et al. 2017; Kenny and Acitelli 1994). Dyadic correlations were calculated to measure participants’ value consistency across the relational roles of son/daughter, friend, and partner. Dyadic correlation, also labelled q-correlation, is the Pearson product–moment correlation between two sets of scores and is meant to capture their similarity in terms of patterns of responses (Barni et al. 2012, 2014a; Kenny and Winquist 2001). In the case of the current study, this correlation allows us to capture the consistency in terms of the relative importance the participants gave to the 12 values as son/daughter, friend, and partner. The dyadic correlations range from −1 to +1: positive correlations indicate that participants have similar value priorities as son/daughter, friend, and partner. Conversely, negative correlations indicate that young adults emphasise different values across the examined relational roles. According to Cohen (1988), coefficients (in absolute value) lower than 0.30 are of small/modest size, coefficients between 0.30 and 0.50 are moderate, and coefficients higher than 0.50 are large. We calculated three dyadic correlation coefficients for each participant (i.e., son/daughter–friend; son/daughter–partner; friend–partner). The coefficients were then transformed into z-scores in order to have a standard normal distribution (Barni et al. 2014a; Malloy and Albright 2001).

Differences in the levels of value consistency across relational roles. We firstly performed a descriptive analysis of each value across the roles of son/daughter, friend, and partner. Then, in order to verify the normality of data distribution, we performed skewness and kurtosis analysis of the z-scores. Finally, we performed a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare value consistencies (i.e., son/daughter–friend consistency vs. son/daughter–partner consistency vs. friend–partner consistency). This informs us about which relational roles are more similar in terms of value priorities for young adults.

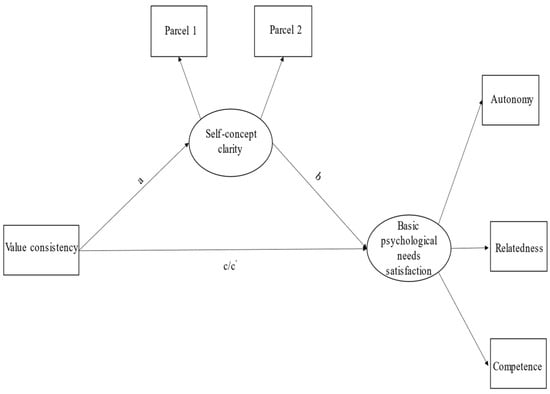

Mediation model. After summing the three z-scores to obtain a total score of value consistency, we performed descriptive analysis (i.e., means, range, skewness, and kurtosis) and calculated bivariate Pearson correlations to assess the associations between the study variables. The conceptualised mediation model (Figure 1) was tested through a structural equation model (SEM) with latent and observed variables (Hayes 2009) in Mplus-6 (Muthén and Muthén 2009). Specifically, the Structural Equation Model (SEM) was used to test the mediation role of self-concept clarity (SCC) in the relationship between value consistency and basic psychological needs satisfaction (BPNS). Since skewness and kurtosis related to the basic psychological needs satisfaction was higher than 1, a robust estimation was used (MLR). We used the total score of value consistency as a single composite indicator, while SCC and BPNS were both modelled as latent variables. For SCC we aggregated items into two parcels for parsimony purposes and for avoiding model-non-identification issues. We used the item-to-construct balance approach for the construction of the parcels (Little et al. 2002). Both the parcels showed a good internal consistency (α = 0.81 and α = 0.77). For BPNS we used, instead, the composite scores of its three subscales (for Cronbach alphas see the Measures section). To verify the goodness-of-fit of the model, the following fit indices were used: Chi-squared test (p-value > 0.05 indicates a good fit), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Non-normed Fit Index (TLI) (values > 0.90 indicate a good fit; values > 0.95 indicate a very good fit), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardised Root Means Square Residual (SRMR) (values < 0.08 indicate a good fit, values < 0.05 indicate a very good fit) (Kenny 2015).

Figure 1.

Conceptual mediation model. Note: a was the association of value consistency on self-concept clarity; b was the association of self-concept clarity on basic psychological needs satisfaction; c represents the total effect; c’ represents the direct effect.

3. Results

Differences in the levels of value consistency across relational roles. In Table 1, we reported the means and the standard deviations of each value across the roles of son/daughter, friend, and partner.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations of values across roles.

All the z-scores showed a normal distribution, as suggested by the skewness and kurtosis, always between −1.00 and +1.00.

The repeated measures ANOVA showed that the mean levels of value consistency differed significantly across some of the relational contexts we considered [F(2,186) = 34.612, p < 0.001]. The highest consistency was that between values as a friend and as partner. Post hoc test, using Bonferroni correction, pointed out a significant difference (p < 0.001) between, on one hand, friend–partner consistency (M = 0.96, SD = 0.488) and son/daughter–friend consistency (M = 0.69; SD = 0.44), and on the other, friend–partner consistency and son/daughter–partner consistency (M = 0.69; SD = 0.40). Conversely, there was not a significant difference between son/daughter–friend and son/daughter–partner consistencies.

Mediation model. Descriptive statistics of the mediation model variables and their correlations were reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of mediation model variables and their correlations.

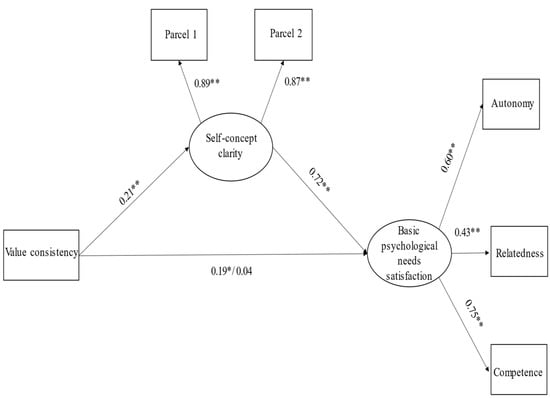

The significant inter-correlations between the study’s variables allowed us to move on with the mediation model (Baron and Kenny 1986). The SEM showed a good fit to the data. Specifically, χ2(7) = 10.677, p = 0.15; RMSEA = 0.05; SRMR = 0.02; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.97. Table 3 reported the standardised effects of the mediation model, and in Figure 2 were reported the observed weight of each path.

Table 3.

Results of the mediation with standardised effects and 95% CI.

Figure 2.

Structural mediation model with standardised effects. Note: ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

Results showed a significant β coefficient between value consistency and SCC (β = 0.21; p < 0.01), as well as a significant β coefficient between SCC and BPNS (β = 0.72; p < 0.01). The direct path between value consistency and BPNS, after adjusting for the mediator, was no more statistically significant (β = 0.04; p = 0.582).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Living in a complex social world might lead to a sense of confusion, because multiple contexts and social roles might meaningfully differ on values they convey (Barni et al. 2014a, 2014b; Hofstede 2001; Klimstra and van Doeselaar 2017; Rohan 2000). Especially during young adulthood, individuals must face several critical social transitions, such as the completion of their education, the achievement of economic independence, the renegotiation of relationships with parents, and the establishment of more stable romantic relationships (Schoon and Silbereisen 2017).

Having a well-developed identity, through which individuals experience consistency and stability of self attributes across roles and contexts, is a protective factor against adverse effects caused by external pressures (Erikson 1968; Klimstra and van Doeselaar 2017). A central role in personal identity is fulfilled by personal values, as they constitute each individual as unique and authentic (Hitlin 2003, 2011; Hitlin and Piliavin 2004; Rohan 2000). Thus, the present study, which involved young adults, was firstly aimed at analysing the intraindividual value consistency across relevant relational roles, those of son/daughter, friend, and partner. Secondly, the study aimed to analyse the relationship among value consistency, self-concept clarity and basic psychological needs satisfaction, with a specific concern in testing the mediating role of self-concept clarity.

Regarding the first aim, the highest level of value consistency was the one related to the roles of friend and partner. In other words, the importance young adults gave to values as friends are very similar to the importance given to values as partners. Specifically, at a descriptive level, it is noteworthy to point out that young adults gave the same importance to values like freedom, honesty, and helpfulness across their roles as a friend and partner. That is, as far as their value priorities were concerned, young adults experience the role of partner in the same way they experience the role of friend. Two speculations are possible: firstly, nowadays intimate relationships among young people are more “liquid” than in the past, a phenomenon that could partly depend on the so-called “laissez-faire approach” to romantic relationships (Drexler 2015). In the last 30 years, especially in Western countries, youths’ romantic relationships have been shown to be more and more characterised by lower levels of commitment (Shulman and Connolly 2013). For example, young adults tend to postpone the age of marriage (Vespa 2014) and frequently move to several sporadic relations (Arnett 2014; Cohen et al. 2003). According to Cigoli and Scabini (2000), commitment with the partner is one of the features that differentiate romantic relationships from friendship ones. Thus, if the commitment dimension comes down, these two types of relationships become more similar, leading the individual to prioritise the same values (e.g., freedom). On the other hand, compared to the other considered value consistency indexes (i.e., relational contexts of friend and son/daughter, or partner and son/daughter), the relational contexts of partner and friend can both be conceptualised as horizontal relationship contexts. Contrary to vertical relationships (i.e., the relationship with parents), the horizontal ones are peer relationships, in terms of power and responsibilities, and, as such, they are characterised by higher levels of reciprocity (Iafrate 2008). To some extent, the relational contexts of friendship and romantic relations are more similar than the relational contexts of son/daughter and friends or partner. Considering the other side of the coin, young adults tend to differentiate their value priorities between inside and outside family relational roles. In other words, it seems that although during young adulthood people generally move away from their families, this relational context remains “unique” compared to all the others. Moreover, family is the first socialisation agency, and the parent–son/daughter relationship is essential in the co-construction of value systems (Barni et al. 2012, 2014a, 2020).

Concerning the second aim of the present study, the findings supported our hypotheses (H1, H2). More in detail, correlational analysis supported the positive association between all the variables. More interestingly, after adjusting for self-concept clarity, the association between value consistency and basic psychological needs satisfaction was no longer significant, highlighting that self-concept clarity fully mediated the relationship. This result confirms and expands the hypothesis of Daniel et al. (2012b), according to which intraindividual value consistency would allow individuals to preserve a sense of stability and meaning. Values are a central aspect of personal identity that reflects aspirations, guiding people in the evaluation of situations and behaviours. Institutional and social agents tend to instil some values explicitly or implicitly in people (Moscovici 1984; Schwartz 1999), endangering the stability of value priorities. However, our findings indicated that if individuals can manage these external pressures, preserving a consistency among their value priorities, they can perceive their self-beliefs as clearly and confidently defined (Campbell et al. 1996). In turn, coherently with several previous findings that highlighted the role of self-concept clarity in enhancing wellbeing (Bigler et al. 2001; Hanley and Garland 2017; Slotter et al. 2010), self-concept clarity is positively associated with the satisfaction of basic psychological needs. Thus, based on our results, it is possible to claim that value consistency might allow individuals to experience a sense of authenticity and uniqueness, linking with a mental state of self-coherence, which in turn is associated with young adults’ perceptions of experiencing fulfilment of basic psychological needs. Moreover, it is well-known that the links between personal values and positive/negative adjustment or behavioural outcomes are often mediated or moderated by other variables (e.g., hope, Russo et al. 2021; locus of control, Engqvist Jonsson and Nilsson 2014; parent practices, Benish-Weisman et al. 2017; for more details, see Roccas and Sagiv 2017), pointing out the complexity of human functioning. Values work as a compass in our lives, guiding our attitudes, predispositions and behaviours (Schwartz 1992, 2012). However, other personal dispositional characteristics, as well as situational factors, might intervene, increasing or decreasing the influence of values (Roccas and Sagiv 2017). As such, from our findings, it is possible to claim that value consistency across relational roles is not enough to explain the satisfaction of psychological needs; on the other hand, among all the human self-beliefs, personal values are the most important, because they represent the beliefs about what is worthy in a person’s life (Schwartz 1992). As such, it might be misleading to only consider the role of self-concept clarity without taking the critical role of personal values into account in explaining the satisfaction of psychological needs. Indeed, it would seem that being able to preserve consistency in value priorities is linked with a mental state of coherence, through which the self-attributes are clear and stable (Campbell 1990).

In interpreting these findings, four main limitations must be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional nature of the present study did not allow us to capture the causality of the relationships among the variables. Thus, future studies with a longitudinal design are needed. Second, our sample was relatively small in size and unbalanced by sex; we adopted a convenience sample, which allowed us to involve more female young adults than male counterparts. The reduced number of men in our sample did not allow us to assess whether and to what extent the model tested was invariant across respondents’ sex. Third, we involved young adults engaged in a stable intimate relationship. Being in a stable romantic relationship could make these individuals different from randomly selected young adults. Indeed, they might experience a greater sense of belongingness (Kashdan et al. 2018), as well as they might achieve higher levels of self-concept clarity. Future studies should also involve single young adults, in order to test the same model and verify if the same results are highlighted. Finally, we took a limited number of relational contexts into account, although these are of great relevance in life. Youths interact with several other relational contexts (e.g., school or work, sporting clubs, etc.) that deserve to be considered.

Despite its limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to address the topic of intraindividual value consistency across significant relational contexts during young adulthood. This is also the first study to uncover one possible mechanism underlying the relationship between value consistency and the satisfaction of basic psychological needs. Considering the protective role of preserving a personal value consistency (e.g., Daniel et al. 2012b), we think it is relevant to increasingly develop psychosocial interventions capable of making salient people’s values priorities. For example, the value affirmation intervention seems to be efficient not only in making people aware of their values, but also in educating them to live consistently with these values (Bradley et al. 2015). This kind of intervention generally adopts three steps in order to promote value consistency: (1) Creating awareness of our core values; (2) taking ownership of our values; (3) putting our values into action. It could be interesting for future studies to explore the effectiveness of these kinds of interventions by analysing their effects in supporting intraindividual value consistency, self-concept clarity, and the promotion of positive adjustment outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.R., D.B. and F.D.; methodology C.R. and D.B.; software, C.R.; formal analysis, C.R.; resources, I.Z.; data collection, C.R. and I.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, C.R.; writing—review and editing, F.D.; supervision, D.B.; project administration, C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Lumsa University of Rome, Italy (protocol number: 3; year of approval: 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The higher prevalence of women than men reflected that most participants were recruited through the collaboration of human and social sciences departments of several universities, which had a higher prevalence of female students. We firstly recruited university students and then, through a snowball sampling, we involved other young adults, with whom the students did not have a romantic or close friendship relationship. |

| 2 | The careless responding bias refers to low accuracy in providing responses, because participants may not carefully read the item content (Bowling et al. 2016; Meade and Craig 2012). Following the guidelines of Ward and Meade (2018) based on the cognitive dissonance theory (Aronson et al. 1991; Stone et al. 1994), to limit this bias we added to the survey instructions that made salient the amount of work and time needed to develop a psychological questionnaire. On the same webpage, participants were asked to fill out three statements related to their commitment to the survey (e.g., I acknowledge that this study will take approximately 30 min). We also added a control item in the middle of the survey (i.e., ‘This is a control item. Please select “strongly disagree”’). Moreover, at the end of the survey, we asked participants to tell us (dichotomous response: yes–no) if their responses were accurate and truthful. Finally, we randomised the order of the scales. |

References

- Arieli, Sharon, Adam M. Grant, and Lilach Sagiv. 2014. Convincing yourself to care about others: An intervention for enhancing benevolence values. Journal of Personality 82: 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, Jeffrey J. 2014. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens through the Twenties. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson, Eliot, Carrie Fried, and Jeff Stone. 1991. Overcoming Denial and Increasing the Intention to Use Condoms through the Induction of Hypocrisy. American Journal of Public Health 81: 1636–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barni, Daniela. 2009. Trasmettere Valori. Tre Generazioni Familiari a Confronto [Transmitting Values. Comparing Three Family Generations]. Milano: Unicopli. [Google Scholar]

- Barni, Daniela, Sonia Ranieri, and Eugenia Scabini. 2012. Value similarity among grandparents, parents, and adolescent children: Unique or stereotypical? Family Science 3: 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barni, Daniela, Ariel Knafo, Asher Ben-Arieh, and Muhammad M Haj-Yahia. 2014a. Parent–child value similarity across and within cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 45: 853–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barni, Daniela, Alessio Vieno, Rosa Rosnati, Michele Roccato, and Eugenia Scabini. 2014b. Multiple sources of adolescents’ conservative values: A multilevel study. European Journal of Developmental Psychology 11: 433–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barni, Daniela, Claudia Russo, Ioana Zagrean, Marika Di Fabio, and Francesca Danioni. 2020. Adolescents’ internalization of moral values: The role of paternal and maternal promotion of volitional functioning. Journal of Family Studies, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, Reuben M., and David D. Kenny. 1986. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51: 1173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, Roy F. 2010. The Self. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgardner, Ann H. 1990. To know oneself is to like oneself: Self-certainty and self-affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 58: 1062–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benish-Weisman, Maya, Ella Daniel, David Schiefer, Anna Möllering, and Ariel Knafo-Noam. 2015. Multiple social identifications and adolescents’ self-esteem. Journal of Adolescence 44: 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benish-Weisman, Maya, Ella Daniel, and Ariel Knafo-Noam. 2017. The relations between values and aggression: A developmental perspective. In Values and Behavior. Edited by Sonia Roccas and Liliach Sagiv. Cham: Springer, pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Bigler, Monica, Greg J. Neimeyer, and Elliott Brown. 2001. The divided self revisited: Effects of self-concept clarity and self-concept differentiation on psychological adjustment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 20: 396–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, Jack. 1961. Ego identity, role variability, and adjustment. Journal of Consulting Psychology 25: 392–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehnke, Klaus, Andreas Hadjar, and Dirk Baier. 2007. Parent-Child Value Similarity: The Role of Zeitgeist. Journal of Marriage and Family 69: 778–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, Nathan A., Jason L. Huang, Caleb B. Bragg, Steve Khazon, Mengqiao Liu, and Caitlin E. Blackmore. 2016. Who cares and who is careless? Insufficient effort responding as a reflection of respondent personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 111: 218–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, Dominique, Evan Crawford, and Sara E. Dahill-Brown. 2015. Fidelity of implementation in a large-scale, randomized, field trial: Identifying the critical components of values affirmation. In The Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness (ED562183). Evanson: Spring. [Google Scholar]

- Brenning, Katrijn, Bart Soenens, and Maarten Vansteenkiste. 2015. What’s your motivation to be pregnant? Relations between motives for parenthood and women’s prenatal functioning. Journal of Family Psychology 29: 755–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, Jennifer D. 1990. Self-Esteem and Clarity of the Self-Concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59: 538–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Jennifer D., Paul D. Trapnell, Steven J. Heine, Ilana M. Katz, Loraine F. Lavallee, and Darrin R. Lehman. 1996. Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70: 141–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Jennifer D., Sunaina Assanand, and Adam Di Paula. 2003. The structure of the self-concept and its relation to psychological adjustment. Journal of Personality 71: 115–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, Rachel, Maarten Vansteenkiste, Liesbeth M. Delesie, An N. Mariman, Bart Soenens, Els Tobback, Jolene Van der Kaap-Deeder, and Dirk P. Vogelaers. 2015. Examining the role of psychological need satisfaction in sleep: A Self-Determination Theory perspective. Personality and Individual Differences 77: 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglioni, Micaela. 2018. Docenti, studenti, genitori: Un triangolo in crisi? [Teachers, students, parents: A triangle in crisis?]. Annali Online Della Didattica e Della Formazione Docente 10: 213–22. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Beiwen, Jasper Van Assche, Maarten Vansteenkiste, Bart Soenens, and Wim Beyers. 2015a. Does psychological need satisfaction matter when environmental or financial safety are at risk? Journal of Happiness Studies 16: 745–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Beiwen, Maarten Vansteenkiste, Wim Beyers, Liesbet Boone, Edward L. Deci, Jolene Van der Kaap-Deeder, Bart Duriez, Willy Lens, Lennia Matos, and Athanasios Mouratidis. 2015b. Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion 39: 216–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigoli, Vittorio, and Eugenia Scabini. 2000. Il Famigliare. Legami, Simboli, Transizioni [The Familiar. Links, Symbols, Transitions]. Milano: Raffaello Cortina Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Margaret S., and Steven M. Graham. 2005. Do relationship researchers neglect singles? Can we do better? Psychological Inquiry 16: 131–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1988. Set correlation and contingency tables. Applied Psychological Measurement 12: 425–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Patricia, Stephanie Kasen, Henian Chen, Claudia Hartmark, and Kathy Gordon. 2003. Variations in patterns of developmental transitions in the emerging adulthood period. Developmental Psychology 39: 657–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooley, Charles Horton. 1992. Human Nature and the Social Order. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, Sebastiano, Sonia Ingoglia, Cristiano Inguglia, Francesca Liga, Alida Lo Coco, and Rosalba Larcan. 2018. Psychometric evaluation of the Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale (BPNSFS) in Italy. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development 51: 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, Elisabetta, Monica Rubini, and Wim Meeus. 2008. Capturing the dynamics of identity formation in various ethnic groups: Development and validation of a three-dimensional model. Journal of Adolescence 31: 207–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, Elisabetta, Marta Scrignaro, Luigia Simona Sica, and Maria Elena Magrin. 2012. Correlates of identity configurations: Three studies with adolescent and emerging adult cohorts. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 41: 732–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, Ella, and Maya Benish-Weisman. 2019. Value development during adolescence: Dimensions of change and stability. Journal of Personality 87: 620–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, Ella, and Maya Crabtree. 2014. Value differentiation and sexual orientation. Papers on Social Representations 23: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, Ella, David Schiefer, Anna Möllering, Maya Benish-Weisman, Klaus Boehnke, and Ariel Knafo. 2012a. Value differentiation in adolescence: The role of age and cultural complexity. Child Development 83: 322–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, Ella, David Schiefer, and Ariel Knafo. 2012b. One and not the same: The consistency of values across contexts among majority and minority members in Israel and Germany. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 43: 1167–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, Ella, Klaus Boehnke, and Ariel Knafo-Noam. 2016. Value-differentiation and self-esteem among majority and immigrant youth. Journal of Moral Education 45: 338–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danioni, Francesca, Daniela Barni, and Rosa Rosnati. 2017. Transmetting sport values: The importance of parental involvement in children’s sport activity. Europe’s Journal of Psychology 13: 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, Edward L., and Richard M. Ryan. 2000. The “What” and “Why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry 11: 227–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, Melikşah. 2010. Close relationships and happiness among emerging adults. Journal of Happiness Studies 11: 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, Manfred, Catherine T. Hastings, and James M. Stanton. 2001. Self-concept differentiation across the adult life span. Psychology and Aging 16: 643–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, Manfred, and Elizabeth L. Hay. 2011. Self-concept differentiation and self-concept clarity across adulthood: Associations with age and psychological well-being. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development 73: 125–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue, Eileen M., Richard W. Robins, Brent W. Roberts, and Oliver P. John. 1993. The divided self: Concurrent and longitudinal effects of psychological adjustment and social roles on self-concept differentiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 64: 834–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drexler, Peggy. 2015. Millennial Women Are Taking a Laissez-Faire Approach to Romance. Available online: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/-millennial-women-are-tak_b_6578116 (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Engqvist Jonsson, Anna-Karin, and Andreas Nilsson. 2014. Exploring the relationship between values and pro-environmental behaviour: The influence of locus of control. Environmental Values 23: 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, Erik H. 1968. Identity: Youth and Crisis. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger, Leon. 1962. Cognitive dissonance. Scientific American 207: 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firmin, Michael W, Ruth L Firmin, and Kaile Lorenzen Merical. 2013. Extended communication efforts involved with college long-distance relationships. Contemporary Issues in Education Research 6: 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fukushima, Osamu, and Tatsuro Hosoe. 2011. Narcissism, variability in self-concept, and well-being. Journal of Research in Personality 45: 568–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergen, Kenneth J. 1972. The concept of self. Contemporary Sociology 1: 324–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, Adam W., and Eric L. Garland. 2017. Clarity of mind: Structural equation modeling of associations between dispositional mindfulness, self-concept clarity and psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences 106: 334–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harter, Susan, and Ann Monsour. 1992. Development analysis of conflict caused by opposing attributes in the adolescent self-portrait. Developmental Psychology 28: 251–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2009. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs 76: 408–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitlin, Steven. 2003. Values as the core of personal identity: Drawing links between two theories of self. Social Psychology Quarterly 66: 118–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitlin, Steven. 2011. Values, personal identity, and the moral self. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research. Edited by Schwartz Seth J., Koen Luyckx and Vivian L. Vignoles. Berlin: Springer, pp. 515–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hitlin, Steven, and Jane Allyn Piliavin. 2004. Values: Reviving a dormant concept. Annual Review of Sociology 30: 359–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, Geert. 2001. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations across Nations. New York: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Iafrate, Raffaella. 2008. Costruire gli affetti e le relazioni [Building affections and relationships]. In Fare Progetto Culturale [Making a Cultural Project]. Edited by Servizio Nazionale per il Progetto Culturale della CEI. Milan: Servizio Nazionale per il Progetto Culturale della CEI, pp. 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan, Todd B., Dann V. Blalock, Kevin C. Young, Kyla A. Machell, Samuel S. Manfort, Patrick E. McKnight, and Patty Ferssizidis. 2018. Personality strengths in romantic relationships: Measuring perceptions of benefits and costs and their impact on personal and relational well-being. Psychological Assessment 30: 241–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, David A. 2015. Measuring Model Fit. Available online: http://davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Kenny, David A., and Linda K. Acitelli. 1994. Measuring similarity in couples. Journal of Family Psychology 8: 417–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, David A., and Lynn Winquist. 2001. The measurement of interpersonal sensitivity: Consideration of design, components, and unit of analysis. In The LEA Series in Personality and Clinical Psychology. Interpersonal Sensitivity: Theory and Measurement. Edited by Hall Judith A. and Frank J. Bernieri. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, pp. 265–302. [Google Scholar]

- Klimstra, Theo A., and Lotte van Doeselaar. 2017. Identity formation in adolescence and young adulthood. In Personality Development across the Lifespan. Edited by Specht Jule. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 293–308. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski, Gary W., Jr., Natalie Nardone, and Alanna J. Raines. 2010. The role of self-concept clarity in relationship quality. Self and Identity 9: 416–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, Todd D., William A. Cunningham, Golan Shahar, and Keith F. Widaman. 2002. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling 9: 151–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, Koen, Luc Goossens, and Bart Soenens. 2006. A developmental contextual perspective on identity construction in emerging adulthood: Change dynamics in commitment formation and commitment evaluation. Developmental Psychology 42: 366–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malloy, Thomas E., and Linda Albright. 2001. Multiple and single interaction dyadic research designs: Conceptual and analytic issues. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 23: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, Ramona. 2018. Bridging cognitive polyphasia and cognitive dissonance: The role of individual differences in the tolerance and negotiation of discrepant cognitions. Papers on Social Representations 27: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, Allen R. 2010. The Multiple Self-aspects Framework: Self-concept representation and its implications. Personality and Social Psychology Review 15: 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConnell, Allan R., Tonya M. Shoda, and Havley M. Skulborstad. 2012. The self as a collection of multiple self-aspects: Structure, development, operation, and implications. Social Cognition 30: 380–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, Adam W., and S. Bartholomew Craig. 2012. Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychological Methods 17: 437–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovici, Serge. 1984. The phenomenon of social representations. In Social Representations. Edited by Moscovici Serge and Robert M. Farr. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 3–69. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, Linda K., and Benght O. Muthén. 2009. Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, Noemi, Ariane Froidevaux, and Andreas Hirschi. 2019. Lifespan perspectives on careers and career development. In Work across the Lifespan. Edited by Boris B. Baltes, Cort W. Rudolph and Hannes Zacher. Amesterdam: Elsevier, pp. 235–59. [Google Scholar]

- Naveh-Kedem, Y., and N. Sverdlik. 2019. Changing prosocial values following an existential threat as a function of political orientation: Understanding the effects of armed conflicts from a terror management perspective. Personality and Individual Differences 150: 109494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parise, Miriam, Ariela F. Pagani, Silvia Donato, and Constantine Sedikides. 2019. Self-concept clarity and relationship satisfaction at the dyadic level. Personal Relationships 26: 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilarska, Aleksandra, and Anna Suchańska. 2015. Self-complexity and self-concept differentiation—What have we been measuring for the past 30 years? Current Psychology 34: 723–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Provencher, Claudine. 2011. Towards a better understanding of cognitive polyphasia. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 41: 377–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quested, Eleanor, Cecilie Thøgersen-Ntoumani, Hannah Uren, Sarah J. Hardcastle, and Richard M. Ryan. 2018. Community gardening: Basic psychological needs as mechanisms to enhance individual and community well-being. Ecopsychology 10: 173–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renedo, Alicia, and Sandra Jovchelovitch. 2007. Expert knowledge, cognitive polyphasia and health: A study on social representations of homelessness among professionals working in the voluntary sector in London. Journal of Health Psychology 12: 779–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, Timothy D., Constantine Sedikides, Tim Wildschut, Jamie Arndt, and Yori Gidron. 2011. Self-concept clarity mediates the relation between stress and subjective well-being. Self and Identity 10: 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccas, Sonia, and Marilynn B. Brewer. 2002. Social identity complexity. Personality and Social Psychology Review 6: 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccas, Sonia, and Lilach Sagiv. 2017. Values and Behavior: Taking a Cross Cultural Perspective. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Roccas, Sonia, Lilach Sagiv, Shalom Schwartz, Nir Halevy, and Roy Eidelson. 2008. Toward a unifying model of identification with groups: Integrating theoretical perspectives. Personality and Social Psychology Review 12: 280–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, Carl Ransom. 1959. A Theory of Therapy, Personality, and Interpersonal Relationships: As Developed in the Client-centered Framework. NewYork: McGraw-Hill, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Rohan, Meg J. 2000. A Rose by Any Name? The Values Construct. Personality and Social Psychology Review 4: 255–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, Claudia, Daniela Barni, Ioana Zagrean, Maria A. Lulli, Giorgia Vecchi, and Francesca Danioni. 2021. The resilient recovery from substance addiction: The role of self-transcendence values and hope. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. 2017. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Scalas, Francesca L., Daniela Fadda, and Mauro Meleddu. 2013. Contributo alla validazione italiana della self-concept clarity scale [Contribution to the Italian validation of the self-concept clarity scale]. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia 40: 615–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, Ingrid, and Rainer K. Silbereisen. 2017. Pathways to Adulthood: Educational Opportunities, Motivation and Attainment in Times of Social Change. London: UCL IOE Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 1992. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 25: 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 1999. A theory of cultural values and some implications for work. Applied Psychology 48: 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 2005. Basic Human Values: Their Content and Structure across Countries. In Valores e Comportamento Nas Organizações. Edited by Tamayo Alvaro and Juliana B. Porto. Petropolis: Vozes, pp. 21–55. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 2012. An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture 2: 919–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, Kennon M., Richard M. Ryan, Laird J. Rawsthorne, and Barbara Ilardi. 1997. Trait self and true self: Cross-role variation in the Big-Five personality traits and its relations with psychological authenticity and subjective well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 73: 1380–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showers, Carolin J., and Kristen C. Kling. 1996. Organization of self-knowledge: Implications for recovery from sad mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70: 578–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showers, Carolin J., Virgil Zeigler-Hill, and Alicia Limke. 2006. Self-structure and childhood maltreatment: Successful compartmentalization and the struggle of integration. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 25: 473–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shulman, Shmuel, and Jennifer Connolly. 2013. The challenge of romantic relationships in emerging adulthood: Reconceptualization of the field. Emerging Adulthood 1: 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, Heather L. Monaghan, Joanne Di Placido, and James M. Conway. 2019. Attachment styles in college students and depression: The mediating role of self differentiation. Mental Health & Prevention 13: 135–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotter, Erica B., Wendi L. Gardner, and Eli J. Finkel. 2010. Who am I without you? The influence of romantic breakup on the self-concept. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 36: 147–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, Mark. 1974. Self-monitoring of expressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 30: 526–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, Jan E., and Peter J. Burke. 2003. A sociological approach to self and identity. In Handbook of Self and Identity. Edited by Mark R. Leary and June Price Tangney. New York: Guildford Press, pp. 128–52. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Jeff, Elliot Aronson, A. Lauren Crain, Matthew P. Winslow, and Carrie B. Fried. 1994. Inducing hypocrisy as a means of encouraging young adults to use condoms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 20: 116–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styla, Rafal, K. S. Jankowski, and H. Suszek. 2010. Skala Niespójności Ja [Self-concept differentiation scale]. Studia Psychologiczne 48: 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Cathy R., and Shannon A. Gadbois. 2007. Academic self-handicapping: The role of self-concept clarity and students’ learning strategies. British Journal of Educational Psychology 77: 101–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usborne, Esther, and Donald M. Taylor. 2010. The role of cultural identity clarity for self-concept clarity, self-esteem, and subjective well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 36: 883–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchione, Michele, Guido Alessandri, Sonia Roccas, and Gian V. Caprara. 2019. A look into the relationship between personality traits and basic values: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of Personality 87: 413–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vespa, Jonathan. 2014. Historical trends in the marital intentions of one-time and serial cohabitors. Journal of Marriage and Family 76: 207–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, Wolfgang. 2007. The theory of social representations as an approach to social psychology. In Familiar and Unfamiliar: Social Representations of Groups in Israel. Edited by E. Orr and S. Ben-Asher. Israel: Ben Gurion, pp. 68–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, Wolfgang, Gerard Duveen, Jyoti Verma, and Matthias Themel. 2000. I have some faith and at the same time I don’t believe—Cognitive polyphasia and cultural change in India. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 10: 301–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M. K., and Adam W. Meade. 2018. Applying social psychology to prevent careless responding during online surveys. Applied Psychology 67: 231–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).