Racial Disparities in Police Crime Victimization

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Research on Racial Disparities in Police Use of Force

1.2. Research on Police Crime and Victimization

2. Method

2.1. Coding and Content Analysis

2.2. Reliability

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Strengths and Limitations

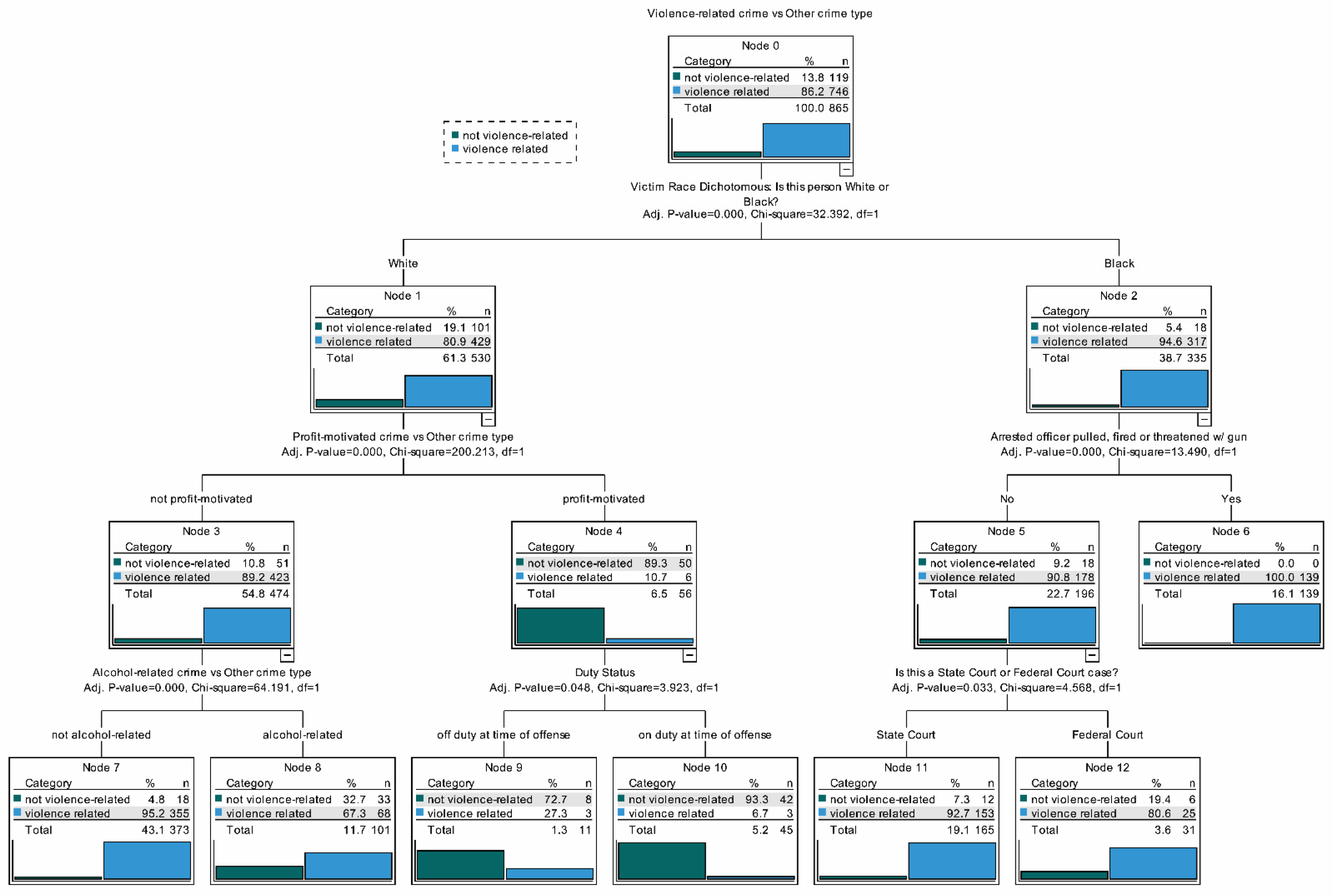

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altman, Alex. 2020. Why the Killing of George Floyd Sparked an American Uprising. Time. June 4. Available online: https://time.com/5847967/george-floyd-protests-trump/ (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Ammons, Jennifer. 2005. Batterers with badges: Officer-involved domestic violence. Women Lawyers Journal 90: 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur, John A., and Charles E. Case. 1994. Race, class, and support for police use of force. Crime, Law and Social Change 21: 167–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewick, Viv, Liz Cheek, and Jonathan Ball. 2004. Statistics review 13: Receiver operating characteristic curves. Critical Care 8: 508–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bharat, Krishna. 2012. Google News Turns 10. Google News Blog. September 22. Available online: http://googlenewsblog.blogspot.com/2012/09/google-news-turns-10.html (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Carlson, Matt. 2007. Order versus access: News search engines and the challenge to traditional journalistic roles. Media, Culture & Society 29: 1014–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chermak, Steven M., Edmund McGarrell, and Jeffrey Gruenewald. 2006. Media coverage of police misconduct and attitudes toward police. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 29: 261–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, Charles, and Ronald Burns. 2008. Police use of force: Assessing the impact of time and space. Policing and Society 18: 322–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, Matthew S., and Brittany Adrion. 2011. Focal concerns and police use of force: Examining the factors associated with taser use. Police Quarterly 14: 366–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, Mairead C., and Michael Doyle. 2000. Violence risk prediction: Clinical and actuarial measures and the role of the Psychopathy Checklist. The British Journal of Psychiatry 177: 303–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Engel, Robin Shepard, James J. Sobol, and Robert E. Worden. 2000. Further exploration of the demeanor hypothesis: The interaction effects of suspects’ characteristics and demeanor on police behavior. Justice Quarterly 17: 235–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridell, Lorie. 2017. Explaining the Disparity in Results Across Studies Assessing Racial Disparity in Police Use of Force: A Research Note. American Journal of Criminal Justice 42: 502–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridell, Lorie, and Hyeyoung Lim. 2016. Assessing the racial aspects of police force using the implicit- and counter-bias perspectives. Journal of Criminal Justice 44: 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, Joel H., Christopher D. Maxwell, and Cedrick J. Heraux. 2002. Characteristics associated with the prevalence and severity of force used by the police. Justice Quarterly 19: 705–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, Alice. 2018. The 1968 Kerner Commission Got It Right, But Nobody Listened. Smithsonian Magazine. March 1. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/1968-kerner-commission-got-it-right-nobody-listened-180968318/ (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Halim, Shaheen, and Beverly L. Stiles. 2001. Differential Support for Police Use of Force, the Death Penalty, and Perceived Harshness of the Courts: Effects of Race, Gender, and Region. Criminal Justice and Behavior 28: 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F., and Klaus Krippendorff. 2007. Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication Methods and Measures 1: 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, Meghan E., and Wesley G. Jennings. 2018. Racial disparities in police use-of-force: A state-of-the-art review. Policing: An International Journal 41: 178–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferis, Eric S., Robert J. Kaminski, Stephen Holmes, and Dena E. Hanley. 1997. The effect of a videotaped arrest on public perceptions of police use of force. Journal of Criminal Justice 25: 381–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, Kimberly Barsamian, Joel S. Steele, Jean M. McMahon, and Greg Stewart. 2017. How suspect race affects police use of force in an interaction over time. Law and Human Behavior 41: 117–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, Robert J., and Michael D. White. 2013. Jammed Up: Bad Cops, Police Misconduct, and the New York City Police Department. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kass, Gordon. V. 1980. An exploratory technique for investigating large quantities of categorical data. Applied Statistics 29: 119–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klahm, Charles Frank, IV, James Frank, and John Liederbach. 2014. Understanding police use of force: Rethinking the link between conceptualization and measurement. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 37: 558–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, David A. 2008. On the importance of sound measures of forceful police actions. Criminology & Public Policy 7: 605–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraska, Peter B., and Victor E. Kappeler. 1995. To serve and pursue: Exploring police sexual violence against women. Justice Quarterly 12: 85–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2013. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, Regina C. 2000. The Politics of Force: Media and the Construction of Police Brutality. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Joongyeup. 2016. Police use of nonlethal force in New York City: Situational and community factors. Policing and Society 26: 875–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lersch, Kim Michelle, and Joe R. Feagin. 1996. Violent police-citizen encounters: An analysis of major newspaper accounts. Critical Sociology 22: 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lersch, Kim Michelle, Thomas Bazley, Thomas Mieczkowski, and Kristina Childs. 2008. Police use of force and neighbourhood characteristics: An examination of structural disadvantage, crime, and resistance. Policing and Society 18: 282–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, Eliott C. 2020. How George Floyd’s Death Ignited a Racial Reckoning that Shows No Signs of Slowing Down. CNN.Com. August 9. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/09/us/george-floyd-protests-different-why/index.html (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Menard, Scott. 2010. Logistic Regression: From Introductory to Advanced Concepts and Applications. Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Nix, Justin, Bradley A. Campbell, Edward H. Byers, and Geoffrey P. Alpert. 2017. A bird’s eye view of civilians killed by police in 2015: Further evidence of implicit bias. Criminology & Public Policy 16: 309–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, Brian K. 2013. White-Collar Crime: The Essentials. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing. 2015. Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing; Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. Available online: https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/Abstract.aspx?ID=271066 (accessed on 5 October 2018).

- Rabe-Hemp, Cara E., and Jeremy Braithwaite. 2013. An exploration of recidivism and the officer shuffle in police sexual violence. Police Quarterly 16: 127–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ready, Justin, Michael D. White, and Christopher Fisher. 2008. Shock value: A comparative analysis of news reports and official records on TASER deployments. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 31: 148–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riffe, Daniel, Stephen Lacy, and Frederick G. Fico. 2005. Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research, 2nd ed. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Riffe, Daniel, Stephen Lacy, Brendan R. Watson, and Frederick G. Fico. 2019. Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research, 4th ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Jeffrey Ian. 2000. Making News of Police Violence: A Comparative Study of Toronto and New York City. Westport: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Schuck, Amie M. 2004. The masking of racial and ethnic disparity in police use of physical force: The effects of gender and custody status. Journal of Criminal Justice 32: 557–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonquist, John A. 1970. Multivariate Model Building: The Validation of a Search Strategy. Ann Arbor: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson, Philip M. 2009. Police Crime: A Newsmaking Criminology Study of Sworn Law Enforcement Officers Arrested, 2005–2007. Indiana: Indiana University of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson, Philip M. 2015. Police crime: The criminal behavior of sworn law enforcement officers. Sociology Compass 9: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinson, Philip M. 2020. Criminology Explains Police Violence. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson, Philip M., and John Liederbach. 2013. Fox in the henhouse: A study of police officers arrested for crimes associated with domestic and/or family violence. Criminal Justice Policy Review 24: 601–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stinson, Philip M., John Liederbach, and Tina L. Freiburger. 2010. Exit strategy: An exploration of late-stage police crime. Police Quarterly 13: 413–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinson, Philip M., Bradford W. Reyns, and John Liederbach. 2012a. Police crime and less-than-lethal coercive force: A description of the criminal misuse of TASERs. International Journal of Police Science & Management 14: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stinson, Philip M., J. Liederbach, and Tina L. Freiburger. 2012b. Off-duty and under arrest: A study of crimes perpetuated by off-duty police. Criminal Justice Policy Review 23: 139–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stinson, Philip M., John Liederbach, Steven L. Brewer, Hans D. Schmalzried, Brooke E. Mathna, and Krista L. Long. 2013. A study of drug-related police corruption arrests. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 36: 491–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stinson, Philip M., John Liederbach, Steven L. Brewer, and Brooke E. Mathna. 2014a. Police sexual misconduct: A national scale study of arrested officers. Criminal Justice Policy Review 26: 665–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stinson, Philip M., John Liederbach, Steven L. Brewer, and Natalie Todak. 2014b. Drink, drive, go to jail? A study of police officers arrested for drunk driving. Journal of Crime and Justice 37: 356–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stinson, Philip M., Steven L. Brewer, Brooke E. Mathna, John Liederbach, and Christine M. Englebrecht. 2014c. Police sexual misconduct: Arrested officers and their victims. Victims & Offenders 10: 117–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinson, Philip M., John Liederbach, Michael Buerger, and Steven L. Brewer. 2018. To protect and collect: A nationwide study of profit-motivated police crime. Criminal Justice Studies 31: 310–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stinson, Philip M., John Liederbach, and Robert W. Taylor. 2020a. Police sexual violence: Exploring the contexts of victimization. Sexual Assault Report 23: 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson, Philip M., Robert W. Taylor, and John Liederbach. 2020b. The situational context of police sexual violence: Data and policy implications. Family & Intimate Partner Violence Quarterly 12: 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Terrill, William, and Stephen D. Mastrofski. 2002. Situational and officer-based determinants of police coercion. Justice Quarterly 19: 215–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrill, William, and Eugene A. Paoline. 2017. Police Use of Less Lethal Force: Does Administrative Policy Matter? Justice Quarterly 34: 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Brian L., and James Daniel Lee. 2004. Who cares if police become violent? Explaining approval of police use of force using a national sample. Sociological Inquiry 74: 381–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuch, Steven A., and Ronald Weitzer. 1997. Racial differences in attitudes toward the police. The Public Opinion Quarterly 61: 642–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. 2010 FIPS Codes for Counties and County Equivalent Entities; Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. Census Bureau. Available online: https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/codes/cou.html (accessed on 14 March 2016).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2003. Measuring Rurality: Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. (Computer File); Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Available online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/briefing/rurality/ruralurbcon/ (accessed on 5 May 2011).

- U.S. Department of Justice. 2000. National Incident-Based Reporting System: Data Collection Guidelines; Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Criminal Justice Information Services Division. Available online: http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/nibrs/nibrs_dcguide.pdf/view (accessed on 9 March 2013).

- U.S. Department of Justice. 2008. Census of State and Local Enforcement Agencies (CSLLEA); Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. [CrossRef]

- U.S. National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. 1968. Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders; Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Walker, Samuel, and Dawn Irlbeck. 2002. Driving while Female: A National Problem in Police Misconduct. Omaha: Department of Criminal Justice, Police Professionalism Initiative, University of Nebraska at Omaha, Available online: http://samuelwalker.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/dwf2002.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2016).

- White, Michael D., and Justin Ready. 2009. Examining fatal and nonfatal incidents involving the TASER: Identifying predictors of suspect death reported in the media. Criminology & Public Policy 8: 865–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | (%) | (Valid %) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Officer Duty Status | Agency Type | |||||||

| Male | 816 | (94.3) | (94.3) | On–Duty | 455 | (52.6) | Primary State Police | 37 | (4.3) |

| Female | 49 | (5.7) | (5.7) | Off–Duty | 410 | (47.4) | Sheriff’s Office | 113 | (13.1) |

| County Police Dept. | 43 | (5.0) | |||||||

| Age | Rank | Municipal Police Dept. | 649 | (75.0) | |||||

| 19–23 | 15 | (1.7) | (1.9) | Officer | 675 | (78.0) | Special Police Dept. | 20 | (2.3) |

| 24–27 | 101 | (11.7) | (13.1) | Detective | 49 | (5.7) | Constable | 1 | (0.1) |

| 28–31 | 101 | (11.7) | (13.1) | Corporal | 18 | (2.1) | Tribal Police Dept. | 1 | (0.1) |

| 32–35 | 145 | (16.8) | (18.8) | Sergeant | 69 | (8.0) | Regional Police Dept. | 1 | (0.1) |

| 36–39 | 104 | (12.0) | (13.5) | Lieutenant | 19 | (2.2) | |||

| 40–43 | 137 | (15.8) | (17.8) | Captain | 7 | (0.8) | Full-Time Sworn Officers | ||

| 44–47 | 66 | (7.6) | (8.6) | Major | 2 | (0.2) | 0 | 3 | (0.3) |

| 48–51 | 50 | (5.8) | (6.5) | Colonel | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | 7 | (0.8) |

| 52–55 | 33 | (3.8) | (4.3) | Deputy Chief | 4 | (0.5) | 2–4 | 17 | (2.0) |

| 56 or older | 18 | (2.1) | (2.3) | Chief | 22 | (2.5) | 5–9 | 24 | (2.8) |

| Missing | 95 | (11.0) | 10–24 | 71 | (8.2) | ||||

| Function | 25–49 | 51 | (5.9) | ||||||

| Years of Service | Patrol and Street Level | 724 | (83.6) | 50–99 | 71 | (8.2) | |||

| 0–2 | 72 | (8.3) | (11.4) | Line/Field Supervisor | 106 | (12.3) | 100–249 | 104 | (12.0) |

| 3–5 | 106 | (12.3) | (16.9) | Management | 35 | (4.0) | 250–499 | 85 | (9.8) |

| 6–8 | 107 | (12.4) | (17.0) | 500–999 | 95 | (11.0) | |||

| 9–11 | 75 | (8.7) | (11.9) | Region of United States | 1000 or more | 337 | (39.0) | ||

| 12–14 | 71 | (8.2) | (11.3) | Northeastern States | 198 | (22.9) | |||

| 15–17 | 73 | (8.4) | (11.6) | Midwestern States | 182 | (21.0) | Part-Time Sworn Officers | ||

| 18–20 | 62 | (7.2) | (9.9) | Southern States | 366 | (42.3) | 0 | 701 | (81.0) |

| 21–23 | 20 | (2.3) | (3.2) | Western States | 119 | (13.8) | 1 | 22 | (2.5) |

| 24–26 | 20 | (2.3) | (3.2) | 2–4 | 44 | (5.1) | |||

| 27 or more years | 23 | (2.7) | (3.7) | Level of Rurality | 5–9 | 39 | (4.5) | ||

| Missing | 236 | (27.3) | Metropolitan County | 792 | (91.6) | 10–24 | 32 | (3.7) | |

| Non–Metro County | 73 | (8.4) | 25–49 | 22 | (2.5) | ||||

| Arresting Agency | 50–99 | 5 | (0.6) | ||||||

| Employing Agency | 272 | (31.4) | (31.4) | 100–249 | 0 | (0.0) | |||

| Another Agency | 593 | (68.6) | (68.6) | 250–499 | 0 | (0.0) |

| n | (%) | (Valid %) | n | (%) | (Valid %) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victim’s Race | Victim’s Law Enforcement Status | ||||||

| White | 497 | (57.5) | (57.5) | Victim is Not a Police Officer | 793 | (91.7) | (91.7) |

| Black | 335 | (38.7) | (38.7) | Victim is a Police Officer | 72 | (8.3) | (8.3) |

| American Indian | 9 | (1.0) | (1.0) | Missing | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Asian | 24 | (2.8) | (2.8) | ||||

| Missing | 0 | (0.0) | Victim Adult or Child | ||||

| Adult | 737 | (85.2) | (85.4) | ||||

| Victim’s Race (Dichotomous) | Child | 126 | (14.6) | (14.6) | |||

| Black | 335 | (38.7) | (38.7) | Missing | 2 | (0.2) | |

| Non-Black | 530 | (61.3) | (61.3) | ||||

| Missing | 0 | (0.0) | Victim’s Sex | ||||

| Female | 305 | (35.3) | (35.9) | ||||

| Victim’s Ethnicity | Male | 545 | (63.0) | (64.1) | |||

| Hispanic | 115 | (13.3) | (13.3) | Missing | 15 | (1.7) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 750 | (86.7) | (86.7) | ||||

| Missing | 0 | (0.0) | Victim’s Age | ||||

| Birth–5 | 25 | (2.9) | (4.4) | ||||

| Victim’s Relationship | 6–11 | 22 | (2.5) | (3.9) | |||

| Current Spouse | 52 | (6.0) | (6.0) | 12–13 | 11 | (1.3) | (1.9) |

| Former Spouse | 7 | (0.8) | (0.8) | 14–15 | 23 | (2.7) | (4.1) |

| Current Girlfriend or Boyfriend | 17 | (2.0) | (2.0) | 16–17 | 42 | (4.9) | (7.4) |

| Former Girlfriend or Boyfriend | 19 | (2.2) | (2.2) | 18–19 | 36 | (4.2) | (6.3) |

| Child or Stepchild | 40 | (4.6) | (4.6) | 20–24 | 99 | (11.4) | (17.5) |

| Some Other Relative | 8 | (0.9) | (0.9) | 25–32 | 135 | (15.6) | (23.8) |

| Unrelated Child | 84 | (9.7) | (9.7) | 33–41 | 80 | (9.2) | (14.1) |

| Stranger or Acquaintance | 638 | (73.8) | (73.8) | 42 or older | 94 | (10.9) | (16.6) |

| Missing | 0 | (0.0) | Missing | 298 | (34.5) |

| Variable Label | N | χ2 | df | p | V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offense Characteristics | |||||

| Official Capacity | 865 | 58.404 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.260 |

| Duty Status | 865 | 42.773 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.222 |

| Officer Brandished Gun | 865 | 36.340 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.205 |

| Violence-Related | 865 | 32.392 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.194 |

| Alcohol-Related | 865 | 29.858 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.186 |

| Profit-Motivated | 865 | 25.781 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.173 |

| Weapons Law Violations | 865 | 16.482 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.138 |

| Vandalism | 865 | 11.770 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.117 |

| Family Violence | 865 | 9.765 | 1 | 0.002 | 0.106 |

| Official Misconduct | 865 | 7.605 | 1 | 0.006 | 0.094 |

| Aggravated Assault | 865 | 7.430 | 1 | 0.006 | 0.093 |

| Civil Rights Violations | 865 | 7.257 | 1 | 0.007 | 0.092 |

| Murder and Non-Negligent Manslaughter | 865 | 7.173 | 1 | 0.007 | 0.091 |

| Drug-Related | 865 | 5.983 | 1 | 0.014 | 0.083 |

| Bribery | 865 | 5.358 | 1 | 0.021 | 0.079 |

| Officer and Victim Characteristics | |||||

| Officer’s Race—Black | 696 | 54.690 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.280 |

| Victim is a Police Officer | 865 | 22.768 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.162 |

| Victim’s Sex | 850 | 16.624 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.140 |

| Officer’s Ethnicity—Hispanic | 696 | 5.331 | 1 | 0.021 | 0.088 |

| Officer Has History of PTSD | 865 | 6.511 | 1 | 0.011 | 0.087 |

| Child Victim | 863 | 3.983 | 1 | 0.046 | 0.068 |

| Officer Previously Shot Someone with Gun | 865 | 3.904 | 1 | 0.048 | 0.067 |

| Agency Response | |||||

| Agency Scandal/Cover-Up | 865 | 46.939 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.233 |

| Officer’s Chief Under Scrutiny | 865 | 32.415 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.194 |

| Officer’s Supervisor is Disciplined | 865 | 11.194 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.114 |

| Reassigned to Another Position | 865 | 7.997 | 1 | 0.005 | 0.096 |

| Case Processing Characteristics | |||||

| Federal Court | 865 | 6.089 | 1 | 0.014 | 0.084 |

| Employing Agency Characteristics | |||||

| Geographic Region | 865 | 85.282 | 3 | <0.001 | 0.314 |

| Variable Label | N | χ2 | df | p | V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offense Characteristics | |||||

| Profit-Motivated | 865 | 309.215 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.598 |

| Alcohol-Related | 865 | 29.699 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.185 |

| Drug-Related | 865 | 22.576 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.162 |

| Police Sexual Violence | 865 | 12.718 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.121 |

| Sex-Related | 865 | 5.506 | 1 | 0.019 | 0.080 |

| Duty Status | 865 | 5.083 | 1 | 0.024 | 0.077 |

| Officer and Victim Characteristics | |||||

| Victim’s Ethnicity—Hispanic | 865 | 67.121 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.279 |

| Victim Injury | 809 | 57.000 | 3 | <0.001 | 0.265 |

| Victim’s Race—Black | 865 | 32.392 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.194 |

| Child Victim | 863 | 6.705 | 1 | 0.010 | 0.088 |

| Officer’s Sex | 865 | 4.098 | 1 | 0.043 | 0.069 |

| Employing Agency Characteristics | |||||

| Geographic Region | 865 | 11.688 | 3 | 0.009 | 0.116 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stinson, P.M.; Wentzlof, C.A.; Liederbach, J.; Brewer, S.L. Racial Disparities in Police Crime Victimization. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10080287

Stinson PM, Wentzlof CA, Liederbach J, Brewer SL. Racial Disparities in Police Crime Victimization. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(8):287. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10080287

Chicago/Turabian StyleStinson, Philip Matthew, Chloe Ann Wentzlof, John Liederbach, and Steven L. Brewer. 2021. "Racial Disparities in Police Crime Victimization" Social Sciences 10, no. 8: 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10080287

APA StyleStinson, P. M., Wentzlof, C. A., Liederbach, J., & Brewer, S. L. (2021). Racial Disparities in Police Crime Victimization. Social Sciences, 10(8), 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10080287