Asian Americans’ Indifference to Black Lives Matter: The Role of Nativity, Belonging and Acknowledgment of Anti-Black Racism

Abstract

“You cannot change any society unless you take responsibility for it; unless you see yourself as belonging to it and responsible for changing it”—Grace Lee Boggs (emphasis added)

1. Introduction

2. The Stressful Commute

2.1. Racial Formation, Immigration and Complex Racial Positioning of Asian Americans

2.2. Asian American Social Identity, Collective Action, and Intersectionality

2.3. Moving Beyond Race: Immigration, Black–Asian Solidarity and Black Lives Matter

2.4. Immigration and the Ethics of Political Indifference: “Yellow Fragility” and/or Belonging

3. The Current Study

4. Materials & Methods

4.1. Data

4.2. Measures

4.3. Analytic Approach

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Multivariate Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abelmann, Nancy, and John Lie. 1997. Blue Dreams: Korean Americans and the Los Angeles Riots. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, Gordon W. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Reading: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Antonsich, Marco. 2010. Searching for belonging—An analytical framework. Geography Compass 4: 644–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, Matt A., Lorrie Frasure-Yokley, Edward D. Vargas, and Janelle Wong. 2018. Best practices in collecting online data with Asian, Black, Latino, and White respondents: Evidence from the 2016 Collaborative Multiracial Post-election Survey. Politics, Groups, and Identities 6: 171–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, Matt A., Lorrie Frasure-Yokley, Edward D. Vargas, and Janelle Wong. 2017. The Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey (CMPS), 2016. Los Angeles: CMPS. [Google Scholar]

- Boggs, Grace Lee. 2016. Living for Change: An Autobiography. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 2001. White Supremacy and Racism in the Post-Civil Rights Era. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 2004. From bi-racial to tri-racial: Towards a new system of racial stratification in the USA. Ethnic and Racial Studies 27: 931–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottero, Wendy. 2010. Intersubjectivity and Bourdieusian approaches to ‘identity’. Cultural Sociology 4: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, Larry, Quoctrung Bui, and Jugal K. Patel. 2020. Black Lives Matter May Be the Larges Movement in U.S. History. New York: The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/03/us/george-floyd-protests-crowd-size.html (accessed on 16 August 2020).

- Chang, Edward T. 2004. “As Los Angeles Burned, Korean America was Born” Community in the Twenty-first Century. Amerasia Journal 30: vi–x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Wendy. 2013. Strategic orientalism: Racial capitalism and the problem of ‘Asianness’. African Identities 11: 148–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, Margaret M. 2020. Stuck: Why Asian Americans Don’t Reach the Top of the Corporate Ladder. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Amanda D., Prentiss A. Dantzler, and Ashley E. Nickels. 2018. Black lives matter: (Re)framing the next wave of black liberation. In Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change. Edited by Patrick G. Coy. Somerville: Emerald Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 1990. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1990. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. In Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement. Edited by Kimberlé Crenshaw, Neil Gotanda, Gray Peller and Kendall Thomas. New York: New Press, pp. 357–83. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé, Priscilla Ocen, and Jyoti Nanda. 2015. Black Girls Matter: Pushed Out, Overpoliced, and Underprotected. New York: Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies, Columbia University. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, John. 1999. The politics of belonging: Some theoretical considerations. In The Politics of Belonging: Migrants and Minorities in Contemporary Europe. Edited by Andrew Geddes and Adrian Favell. Aldershot: Ashgate, pp. 15–41. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Angela Y. 2016. Freedom Is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement. Chicago: Haymarket Books. [Google Scholar]

- Della Porta, Donatella. 2013. Can Democracy Be Saved?: Participation, Deliberation and Social Movements. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- DiAngelo, Robin. 2018. White Fragility: Why It’s so Hard for White People to Talk about Racism. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dimock, Michael. 2019. Defining Generations: Where Millennials End and Generation Z Begins. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins/ (accessed on 16 August 2020).

- Ebert, Kim, and Dina Okamoto. 2015. Legitimating contexts, immigrant power, and exclusionary actions. Social Problems 62: 40–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdal, Marta Bivand, and Ceri Oeppen. 2013. Migrant balancing acts: Understanding the interactions between integration and transnationalism. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39: 867–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espiritu, Yen Le. 1993. Asian American Panethnicity: Bridging Institutions and Identities. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fortier, Anne-Marie. 2000. Migrant Belongings: Memory, Space, Identity. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fujino, Diane Carol. 2005. Heartbeat of Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, Marc A., Patricia A. Homan, Catherine García, and Tyson H. Brown. 2020. The color of COVID-19: Structural racism and the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on older racial and ethnic minorities. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 76: e75–e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, Steven J. 2004. From Jim Crow to racial hegemony: Evolving explanations of racial hierarchy. Ethnic and Racial Studies 27: 951–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Elaine Lynn-Ee. 2008. Citizenship, migration and transnationalism: A review and critical interventions. Geography Compass 2: 1286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Jennifer. 2020. Anti-Asian racism, Black Lives Matter, and COVID-19. Japan Forum 3: 148–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinger, David A. 2000. Postethnic America: Beyond Multiculturalism. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Cathy P. 2020. Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning. New York: One World. [Google Scholar]

- Hope, Jeanelle K. 2019. This tree needs water!: A case study on the radical potential of Afro-Asian solidarity in the era of Black Lives Matter. Amerasia Journal 45: 222–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, Juliana M., and Gretchen Livingston. 2016. How Americans View the Black Lives Matter Movement. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/07/08/how-americans-view-the-black-lives-matter-movement/ (accessed on 16 August 2020).

- Johnson, David R., and Rebekah Young. 2011. Toward best practices in analyzing datasets with missing data: Comparisons and recommendations. Journal of Marriage and Family 73: 926–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampmark, Binoy. 2020. Protesting in pandemic times: COVID-19, public health, and Black Lives Matter. Contention 8: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, Grace. 2006. Where are the Asian and Hispanic victims of Katrina?: A metaphor for invisible minorities in contemporary racial discourse. Du Bois Review 3: 223–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendi, Ibram X. 2019. How to be An Antiracist. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Khan-Cullors, Patrisse. 2018. When They Call You a Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir. New York: St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Claire Jean. 1999. The racial triangulation of Asian Americans. Politics & Society 27: 105–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Clare Jean, and Taeku Lee. 2001. Interracial politics: Asian Americans and other communities of color. Political Science and Politics 34: 631–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Elaine H. 1993. Home is where the han is: A Korean American perspective on the Los Angeles upheavals. Social Justice 20: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jae Kyun. 2015. Yellow over black: History of race in Korea and the new study of race and empire. Critical Sociology 41: 205–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jae Kyun, and Moon-Kie Jung. 2019. “The Darker to the Lighter Races”: The Precolonial Construction of Racial Inferiors in Korea. History of the Present 9: 55–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Nadia. 2007. Asian Americans’ experiences of "race" and racism. In Handbooks of the Sociology of Racial and Ethnic Relations. Edited by Hernán Vera and Joe R. Feagin. New York: Springer, pp. 131–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kochiyama, Yuri. 1994. The impact of Malcolm X on Asian-American politics and activism. In Blacks, Latinos, and Asians in Urban America: Status and Prospects for Politics and Activism. Edited by James Jennings. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, pp. 129–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, Wen H. 1995. Coping with racial discrimination: The case of Asian Americans. Ethnic and Racial Studies 18: 109–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Yaejoon. 2017. Transcolonial racial formation: Constructing the “Irish of the Orient” in US-occupied Korea. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 3: 268–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Erika. 2015. The making of Asian America: A History. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jennifer C. 2020. The nativist fault line and precariousness of race in the time of Coronavirus. ASA Footnotes 48: 17. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jennifer C., and Samuel Kye. 2016. Racialized assimilation of Asian Americans. Annual Review of Sociology 42: 253–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, Nancy. 2013. Racial Capitalism. Harvard Law Review 126: 2151–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, Pei-te, M. Margaret Conway, and Janelle Wong. 2004. The Politics of Asian Americans: Diversity and Community. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitz, George. 1995. The possessive investment in whiteness: Racialized social democracy and the” white” problem in American studies. American Quarterly 47: 369–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Wen. 2018. Complicity and resistance: Asian American body politics in Black Lives Matter. Journal of Asian American Studies 21: 421–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, Ian H. 1997. White by Law: The Legal Construction of Race. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, Daryl J. 2009. Chains of Babylon: The Rise of Asian America. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, Mari. 1993. We will not be used. UCLA Asian Pacific American Law Journal 1: 79. [Google Scholar]

- May, Vanessa. 2011. Self, belonging and social change. Sociology 45: 363–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGary, Howard. 1997. Racism, social justice, and interracial coalitions. The Journal of Ethics 1: 249–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merseth, Julie Lee. 2018. Race-ing solidarity: Asian Americans and support for Black Lives Matter. Politics, Groups, and Identities 6: 337–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milbrath, Lester W., and Madan Lal Goel. 1977. Political Participation: How and Why Do People Get Involved in Politics? Chicago: Rand McNally College Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Nopper, Tamara K. 2006. The 1992 Los Angeles riots and the Asian American abandonment narrative as political fiction. The New Centennial Review 6: 73–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, Kevin B. 2020. American Medical Association: Racism is a Threat to Public Health. Chicago: American Medical Association. Available online: https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/health-equity/ama-racism-threat-public-health (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Okamoto, Dina G. 2003. Toward a theory of panethnicity: Explaining Asian American collective action. American Sociological Review 1: 811–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Okamoto, Dina G. 2014. Redefining Race: Asian American Panethnicity and Shifting Ethnic Boundaries. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. 1994. Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, Aihwa, Virginia R. Dominguez, Jonathan Friedman, Nina Glick Schiller, Verena Stolcke, David Y.H. Wu, and Hu Ying. 1996. Cultural citizenship as subject-making: Immigrants negotiate racial and cultural boundaries in the United States. Current Anthropology 37: 737–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Kim, Juliana Menasce Horowitz, and Monica Anderson. 2020. Amid Protests, Majorities Across Racial and Ethnic Groups Express Support for the Black Lives Matter Movement. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/06/12/amid-protests-majorities-across-racial-and-ethnic-groups-express-support-for-the-black-lives-matter-movement/ (accessed on 16 August 2020).

- Perea, Juan F. 1998. The Black/White binary paradigm of race: The normal science of American racial thought. La Raza Law Journal 10: 127–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, Thomas F. 1998. Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology 49: 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirtle, Whitney N. Laster. 2020. Racial capitalism: A fundamental cause of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic inequities in the United States. Health Education & Behavior 47: 504–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan, S. Karthick, and Thomas J. Espenshade. 2001. Immigrant incorporation and political participation in the United States. International Migration Review 35: 870–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Nandita. 2020. Home Rule: National Sovereignty and the Separation of Natives and Migrants. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel, Georg. 1997. The Metropolis and Mental Life. In Simmel on Culture. Edited by David Frisby and Mike Featherstone. London: Sage, pp. 174–85. First published 1903. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, Bernd, and Bert Klandermans. 2001. Politicized collective identity: A social psychological analysis. American Psychologist 56: 319–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrentny, John David. 2001. Color Lines: Affirmative Action, Immigration, and Civil Rights Options for America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Andrea. 2012. Indigeneity, Settler Colonialism and White Supremacy. In Racial Formation in the Twenty-First Century. Edited by Daniel Martinez HoSang, Oneka LaBennett and Laura Pulido. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 66–94. [Google Scholar]

- Takaki, Roland. 1993. A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America. New York: Back Bay Books. [Google Scholar]

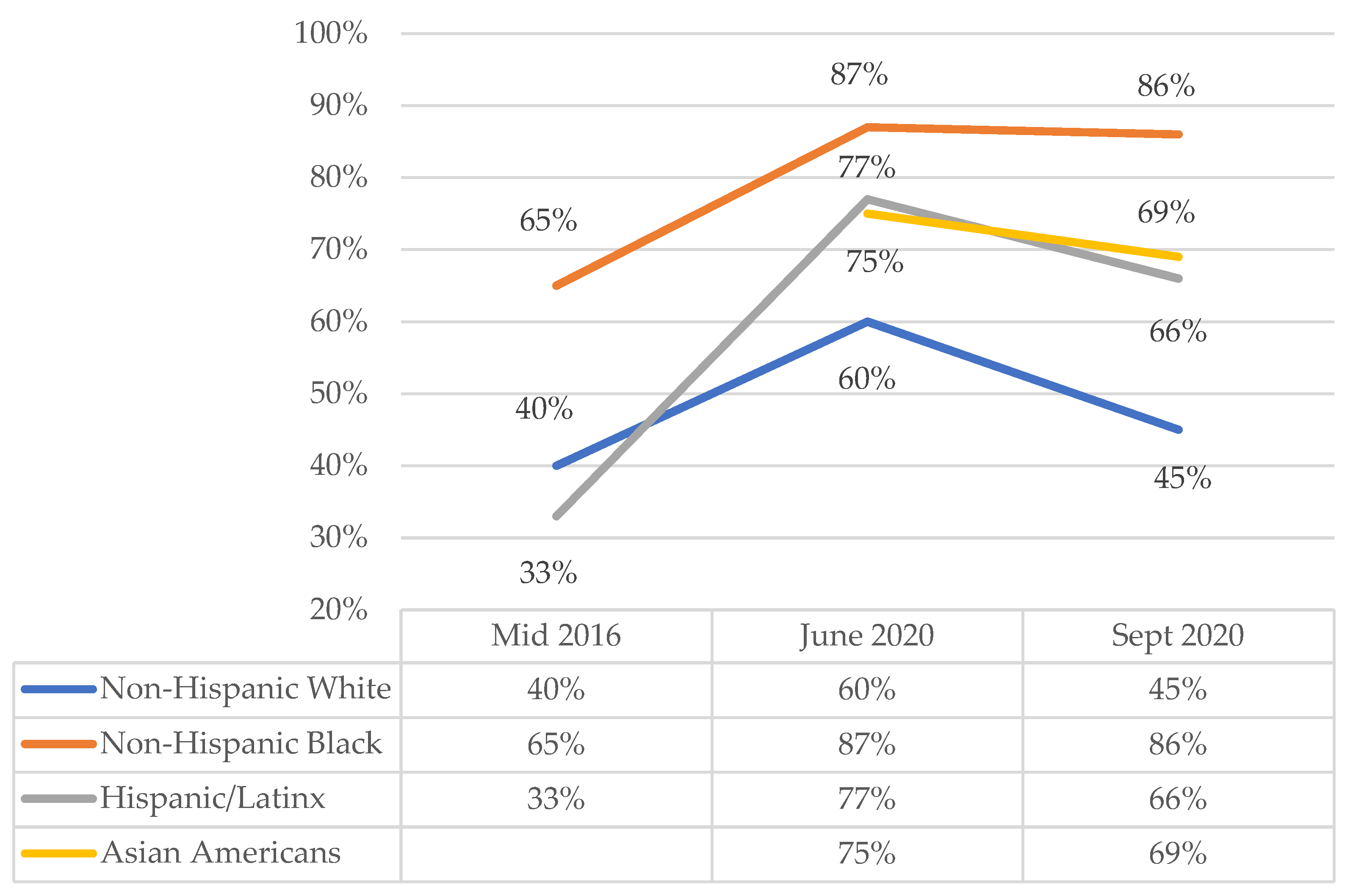

- Thomas, Deja, and Juliana Menasce Horowitz. 2020. Support for Black Lives Matter Has Decreased since June but Remains Strong among Black Americans. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/09/16/support-for-black-lives-matter-has-decreased-since-june-but-remains-strong-among-black-americans/ (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Thomas, Emma F., Elena Zubielevitch, Chris G. Sibley, and Danny Osborne. 2020. Testing the social identity model of collective action longitudinally and across structurally disadvantaged and advantaged groups. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 46: 823–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonkiss, Fran. 2003. The Ethics of Indifference: Community and Solitude in the City. International Journal of Cultural Studies 6: 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Nellie, Nadine Nakamura, Grace S. Kim, Gagan S. Khera, and Julie M. AhnAllen. 2018. APIsforBlackLives: Unpacking the interracial discourse on the Asian American Pacific Islander and Black communities. Community Psychology in Global Perspective 4: 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 1960. Census 1960; Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2020. 2014–2018 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates; Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

- Van Zomeren, Martijn, Tom Postmes, and Russell Spears. 2008. Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: A quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychological Bulletin 134: 504–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C. 1993. Race Matters. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wiley, Shaun, and Nida Bikmen. 2012. Building solidarity across difference: Social identity, intersectionality, and collective action for social change. In Social Categories in Everyday Experiences. Edited by Shaun Wiley, Gina Philogène and Tracey A. Revenson. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Janelle. S., S. Karthick Ramakrishnan, Taeku Lee, and Jane Junn. 2011. Asian American Political Participation: Emerging Constituents and Their Political Identities. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Ellen D. 2013. The Color of Success: Asian Americans and the Origins of the Model Minority. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Jun. 2005. Why do minorities participate less? The effects of immigration, education, and electoral process on Asian American voter registration and turnout. Social Science Research 34: 682–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Jun, and Jennifer C. Lee. 2013. The marginalized “model” minority: An empirical examination of the racial triangulation of Asian Americans. Social Forces 91: 1363–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yancey, George A. 2003. Who is White? Latinos, Asians, and the New Black/Nonblack Divide. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Iris Marion. 2011. Justice and the Politics of Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Min, and Jennifer Lee. 2017. Hyper-selectivity and the remaking of culture: Understanding the Asian American achievement paradox. Asian American Journal of Psychology 8: 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, Helen. 2000. Asian American Dreams: The Emergence of an American People. New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux. [Google Scholar]

| % Support of BLM | % Indifferent of BLM | % Oppose of BLM | Belonging | % Acknowledgement of Anti-Black Racisms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White | 26.7% | 28.9% | 44.4% | 2.69 | 26.6% |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 70.1% | 22.4% | 7.5% | 2.45 | 69.1% |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 45.3% | 37.1% | 17.6% | 2.44 | 48.7% |

| Asian Americans | 40.2% | 42.5% | 17.4% | 2.27 | 32.7% |

| Foreign-born Asian Americans | 42.0% | 40.0% | 18.0% | 2.47 | 45.2% |

| U.S.-born Asian Americans | 39.1% | 43.3% | 17.6% | 2.21 | 28.8% |

| Total | 35.5% | 30.1% | 34.4% | 2.60 | 35.6% |

| Total | U.S. Born (n = 1635) | Foreign Born (n = 1371) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %/m | std | %/m | std | %/m | std | diff | |

| Indifference to BLM | 42.5% | 0.49 | 40.0% | 0.49 | 43.3% | 0.50 | *** |

| Key Variables of Interests | |||||||

| Foreign born | 45.6% | 0.43 | 0.0% | 0.00 | 100% | 0.00 | |

| Belonging | 2.27 | 0.81 | 2.47 | 0.78 | 2.21 | 0.81 | *** |

| American identity (0–10) | 7.02 | 2.95 | 8.19 | 2.42 | 6.66 | 3.00 | *** |

| Asian American identity (0–10) | 7.33 | 2.70 | 8.07 | 2.58 | 7.10 | 2.70 | *** |

| Ethnic identity (0–10) | 7.33 | 2.87 | 7.08 | 2.96 | 7.41 | 2.84 | *** |

| Citizenship status | 66.5% | 0.47 | 100% | 0.00 | 56.0% | 0.50 | *** |

| Acknowledgement of anti-Black racisms | 32.7% | 0.47 | 45.2% | 0.50 | 28.8% | 0.45 | *** |

| Own racial discrimination experience | 39.7% | 0.49 | 46.9% | 0.50 | 37.4% | 0.48 | *** |

| % Black residents in neighborhood | 7.0% | 1.08 | 11.1% | 1.17 | 5.8% | 1.05 | |

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | |||||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Chinese | 21.5% | 0.41 | 28.4% | 0.45 | 19.4% | 0.40 | *** |

| Taiwanese | 2.8% | 0.16 | 1.5% | 0.12 | 3.2% | 0.18 | * |

| Indian | 21.2% | 0.41 | 9.1% | 0.29 | 25.0% | 0.43 | *** |

| Korean | 9.1% | 0.29 | 9.0% | 0.29 | 9.2% | 0.29 | * |

| Filipinx | 17.2% | 0.38 | 13.7% | 0.34 | 18.3% | 0.39 | *** |

| Vietnamese | 10.5% | 0.31 | 15.3% | 0.36 | 9.0% | 0.29 | *** |

| Japanese | 5.1% | 0.22 | 11.6% | 0.32 | 3.1% | 0.17 | *** |

| Other Asian Americans | 12.5% | 0.33 | 11.4% | 0.32 | 12.8% | 0.33 | |

| Female | 50.9% | 0.50 | 50.5% | 0.50 | 51.0% | 0.50 | |

| LGBTQ+ sexual orientation | 10.1% | 0.30 | 10.6% | 0.31 | 10.0% | 0.30 | |

| Generation | |||||||

| Greatest Generation | 6.9% | 0.25 | 5.4% | 0.23 | 7.3% | 0.26 | |

| Baby Boomer | 24.2% | 0.43 | 22.5% | 0.42 | 24.8% | 0.43 | |

| Millennials | 28.2% | 0.45 | 23.5% | 0.42 | 29.7% | 0.46 | |

| Generation X | 33.6% | 0.47 | 35.5% | 0.48 | 33.0% | 0.47 | ** |

| Generation Z (ref) | 7.1% | 0.26 | 13.1% | 0.34 | 5.2% | 0.22 | *** |

| Marital status (Married) | 58.6% | 0.49 | 42.0% | 0.49 | 63.7% | 0.48 | *** |

| Skin color | 3.44 | 1.34 | 3.38 | 1.35 | 3.46 | 1.34 | * |

| Economic and Political Characteristics | |||||||

| Education (College and beyond) | 54.3% | 0.50 | 44.1% | 0.50 | 57.5% | 0.49 | *** |

| Employed (Full-time) | 41.1% | 0.49 | 41.7% | 0.49 | 40.9% | 0.49 | + |

| Household income | |||||||

| Less than $40,000 | 29.2% | 0.45 | 32.1% | 0.47 | 28.3% | 0.45 | |

| $40,000 to $69,999 | 24.4% | 0.43 | 21.9% | 0.41 | 25.2% | 0.43 | * |

| $70,000 to $99,999 | 20.0% | 0.40 | 19.3% | 0.40 | 20.2% | 0.40 | |

| $100k more | 26.4% | 0.44 | 26.6% | 0.44 | 26.3% | 0.44 | * |

| Conservative political ideology | 19.3% | 0.39 | 17.6% | 0.38 | 19.9% | 0.40 | |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 3A (USB) | Model 3B (FB) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Variables of Interests | ||||||||||

| Foreign born | 1.19 | * | 1.09 | 1.03 | ||||||

| Belonging | 0.89 | * | 0.89 | * | 0.87 | * | 0.94 | |||

| American Identity (0-10) | 0.96 | *** | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | |||||

| Asian American Identity (0-10) | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.97 | 1.01 | ||||||

| Ethnic Identity (0-10) | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.04 | + | 0.97 | |||||

| Citizenship status | 1.02 | 1.08 | 1.00 | 1.16 | ||||||

| Acknowledgement of anti-Black racisms | 0.48 | *** | 0.48 | *** | 0.42 | *** | ||||

| Own racial discrimination experience | 0.74 | *** | 0.77 | * | 0.72 | ** | ||||

| % Black residents in neighborhood | 0.94 | + | 0.97 | 0.94 | ||||||

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity (ref: Chinese) | ||||||||||

| Taiwanese | 1.07 | 1.05 | 1.23 | 0.84 | 1.73 | |||||

| Indian | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.65 | * | 1.06 | ||||

| Korean | 0.78 | + | 0.83 | 1.07 | 1.47 | + | 0.90 | |||

| Filipinx | 0.86 | 0.88 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.14 | |||||

| Vietnamese | 1.25 | + | 1.31 | * | 1.26 | 1.45 | + | 0.96 | ||

| Japanese | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.16 | |||||

| Other Asian Americans | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.95 | 1.19 | 0.74 | |||||

| Female | 1.13 | + | 1.13 | + | 1.18 | * | 1.13 | 1.27 | + | |

| LGBTQ+ sexual orientation | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.92 | |||||

| Generation (ref: Gen Z) | ||||||||||

| Greatest Generation | 2.56 | *** | 2.74 | *** | 2.33 | ** | 3.00 | ** | 1.88 | |

| Baby Boomer | 2.19 | *** | 2.34 | *** | 1.90 | ** | 2.15 | ** | 1.82 | |

| Millennials | 2.21 | *** | 2.24 | *** | 1.87 | ** | 1.60 | + | 2.47 | * |

| Generation X | 1.86 | ** | 1.84 | ** | 1.57 | * | 1.64 | * | 1.65 | |

| Marital status (Married) | 1.51 | *** | 1.48 | *** | 1.46 | *** | 1.46 | ** | 1.64 | *** |

| Skin color | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.05 | ||||||

| Economic and Political Characteristics | ||||||||||

| Education (College and beyond) | 0.81 | * | 0.80 | * | 0.82 | * | 0.66 | ** | 1.09 | |

| Employed (Full-time) | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.99 | |||||

| Household income (ref: $100k more) | ||||||||||

| Less than $40,000 | 1.78 | *** | 1.70 | *** | 1.69 | *** | 1.31 | + | 2.22 | *** |

| $40,000 to $69,999 | 1.49 | *** | 1.44 | ** | 1.39 | ** | 1.22 | 1.63 | ** | |

| $70,000 to $99,999 | 1.48 | *** | 1.44 | *** | 1.36 | ** | 1.18 | 1.55 | * | |

| Conservative political ideology | 0.74 | ** | 0.75 | ** | 0.67 | *** | 0.54 | *** | 0.85 | |

| Constant | 0.21 | *** | 0.41 | ** | 0.53 | * | 0.53 | 0.29 | * | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yellow Horse, A.J.; Kuo, K.; Seaton, E.K.; Vargas, E.D. Asian Americans’ Indifference to Black Lives Matter: The Role of Nativity, Belonging and Acknowledgment of Anti-Black Racism. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10050168

Yellow Horse AJ, Kuo K, Seaton EK, Vargas ED. Asian Americans’ Indifference to Black Lives Matter: The Role of Nativity, Belonging and Acknowledgment of Anti-Black Racism. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(5):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10050168

Chicago/Turabian StyleYellow Horse, Aggie J., Karen Kuo, Eleanor K. Seaton, and Edward D. Vargas. 2021. "Asian Americans’ Indifference to Black Lives Matter: The Role of Nativity, Belonging and Acknowledgment of Anti-Black Racism" Social Sciences 10, no. 5: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10050168

APA StyleYellow Horse, A. J., Kuo, K., Seaton, E. K., & Vargas, E. D. (2021). Asian Americans’ Indifference to Black Lives Matter: The Role of Nativity, Belonging and Acknowledgment of Anti-Black Racism. Social Sciences, 10(5), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10050168