Insight into the Organizational Culture and Challenges Faced by Women STEM Leaders in Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Questions

- How do women face everyday challenges in their position as a leader in STEM?

- What biases or stereotypes, if any, does she encountered in her STEM position as a leader

- What experiences have altered or changed a woman in STEM as a leader?

- What is the professional environment like for women in STEM?

- How does organizational culture facilitate or hinder the leadership style of STEM women?

2. Literature Review

3. Methods

3.1. Research Approach and Study Design

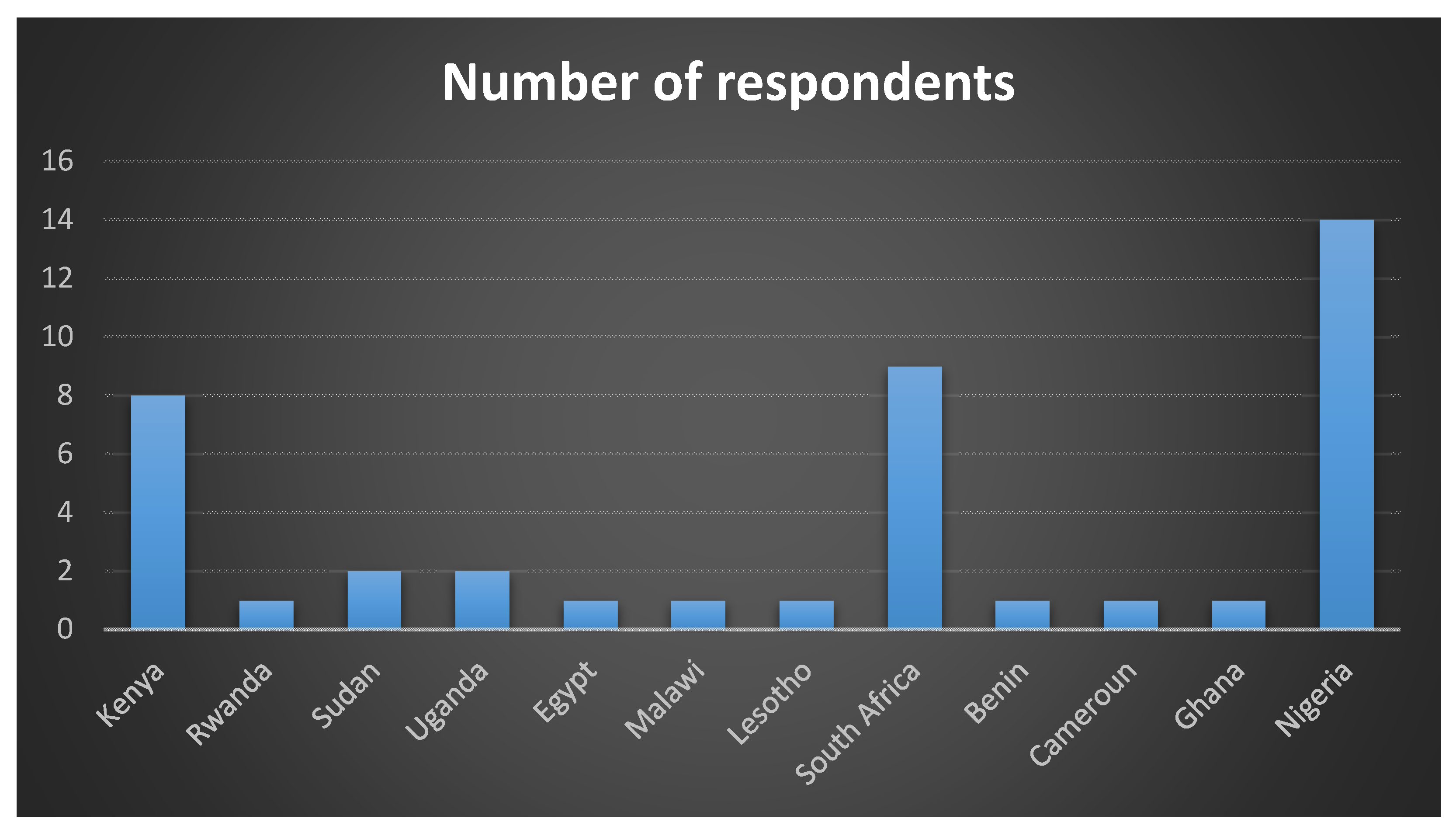

3.2. Population and Sampling

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Trustworthiness and Ethical Considerations

4. Results

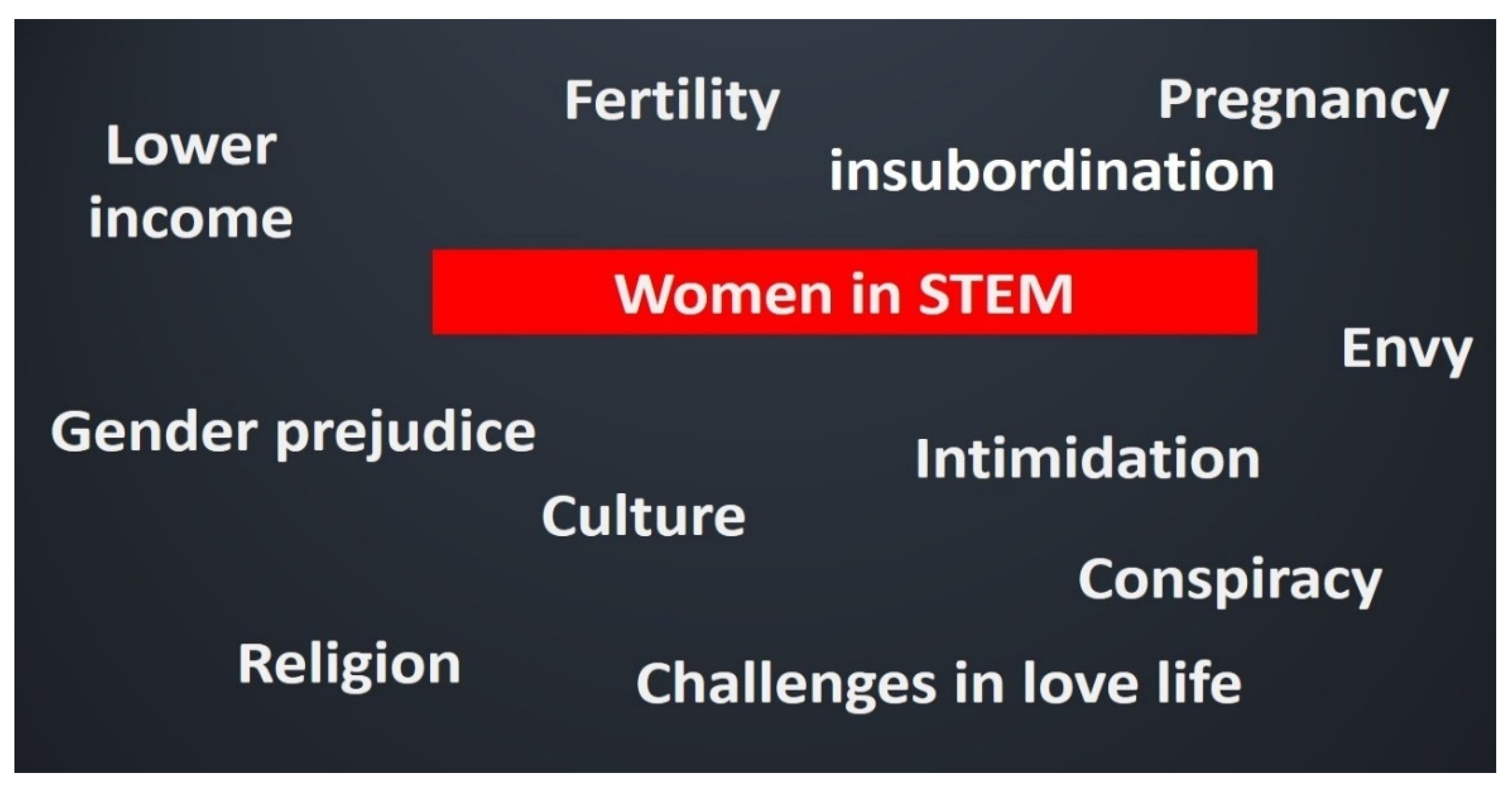

4.1. How Do Women Face Everyday Challenges in Their Position as STEM Leaders?

“Males say negative things about me sometimes, insubordination by some male counterparts under my leadership”.(P1/Ghana/55–64)

“Women who are negative towards other women and are talkative and will always talk behind your back to pull me down”.(P9/South Africa/55–64)

“Being underrated, looked down on and being side-lined when crucial/hard decisions are to be made because I am a female”.(P21/Kenya/35–44)

“Lack of cooperation from colleagues is an issue, especially when they want to underestimate my capability”.(P20/Nigeria/35–44)

“Have to rearrange the family demands with that of the job. I must work for long hours and travel quite often”.(P3/South Africa/55–64)

“I haven’t personally experienced any hindrance at any organization where I held a leadership position. However, I have realized that other family roles can clash with management expectations, especially as a single parent. It is widespread where a woman in leadership should work long hours, be absent from home for a long period, and lack extended family support. Personally, the boarding school has been the best choice in making sure that I don’t feel guilty of giving my childless attention”.(P33/Lesotho/45–54)

“Men do not regard me, and they see me as a threat, so I am always not flowing with them”.(P23/Nigeria/55–64)

“Getting people to understand one’s vision and objectives of working in interdisciplinary research” (P8/Nigeria/45–54) was a challenge.

“I have to be at work for longer hours and to travel quite often. I do not have the same level ground to contest anything with my colleagues’ opposite sex. I feel intimidated, then comes the need to have to combine family responsibilities with giving birth to children and house care” (P6/Nigeria/45–54), and another participant categorically emphasized family responsibility.(P13/South Africa/45–54)

“My main challenge is the balance between work, traveling and family care which is not always understood by all members of our senior staff”.(P40/Cameroun/35–44)

“I was taught to see challenges as hurdles to be crossed to achieve goals. Therefore, I have always programmed myself to handle things as they come”. The “challenges I had is common to any gender—but which I was always able to confront with the backing of the Dean and the support of the University, especially male colleagues, I found it very easy to confide in them than to women and of course prayer!”.(P20/Nigeria/35–44)

4.2. What Biases or Stereotypes, If Any, Does She Encountered in Her STEM Position as a Leader

“Voting for the positions of Dean first time. Some males refused to vote for me. Some were jealous of my rapid progress both at work and in the church”.(P1/Ghana/55–64)

“Man does not value decisions made by women especially if they are from the same race”.(P2/Malawi/45–54)

“They do not expect me [a woman] to know how to fix the network or work with technology. People equality believe that women positions should be below men”.(P12/South Africa/25–34)

“Implicit bias related to gender and grade. Sometimes, people think that I am not qualified enough to be involved in a certain decision making”.(P40/Cameroun/35–44)

“The biggest stereotype promoted by some women is that when a woman holds a managerial position, they should start behaving and acting like men. Women are made to act or toughen up and lose their womanliness. Women are emotional and sometimes make irrational decisions; women like fighting and gossiping”.(P33/Lesotho/45–54)

“I relate to other people on an equal footing, and I have not experienced problems as a leader”.(P6/Nigeria/45–54)

“Not much and probably because, in the institution that I work for, most of the leaders and bosses are ladies and so to have a lady leader is normal”.(P28/Kenya/45–54)

Another participant wrote, “none”.(P13/South Africa/45–54)

4.3. What Experiences Have Altered or Changed a Woman in STEM as a Leader?

“I always think ahead and raise my head in the board room. The ability to analyze and process information proactively and thinking out of the box is also a new experience or a factor to consider. Add to these is the ability to incorporate more trans-disciplinary and inter-disciplinary research than pure and basic sciences, networking across the globe, working with people from different cultures, and appreciating different viewpoints. The above points are not only transformational but also bring people together”.(P16/Kenya/55–64)

“I learned from short courses outside STEM that is incorporated into STEM research to be strong and still be involved in everything I do. But being watchful of them not to destroy what other people who have gone higher, I learn from previous works as well as inputs and criticisms from others”.(P10/Nigeria/55–64)

“The admiration I have for successful women in STEM over the world constitutes, for me, a source of motivation that makes me believe that I could do better to achieve my goal. I attended a workshop for women in science in 2015 in Trieste, where I met ladies who got the Elsevier prizes. It led me to review my position as a leader and doubled the effort to succeed, which allowed me to perform lots of things from the professional point of view since then”.(P40/Cameroun/35–44)

“It should be noted that in our deeper most selves, we are all the same! We have the same fears, the same challenges, the difference being how one faces those fears and how one tackles those challenges, dealing with people with different characteristics”.(P27/South Africa/65–74)

“knowing that being a leader, I understood that I must be a driving force and must carry everybody along (selflessly). I was allowed to lead and attain academic development, which has equipped me to perform maximally in my field”.(P30/Nigeria/35–44)

4.4. What Is the Professional Environment Like for Women in STEM?

“Talking about the professional environment in terms of collaboration, I would say it is friendly, and the networking is opened. But I am always in trouble due to the lack of facilities when considering my project or research.(P40/Cameroun/35–44)

“Collaborative/collective responsibility”.(P48/Uganda/35–44)

“I am working/studying in a quite nice environment where I, as a woman, have value and voice when needed. However, sometimes a job is not assigned to you mainly because you are a woman. It is funny, but there are always lots of gossiping around when a woman achieves something, but I don’t care about it”.(P47/Cameroun/25–35)

4.5. How Does Organizational Culture Facilitate or Hinder the Leadership Style of STEM Women?

“Rituals, routines, control systems, and stories. A woman from Ghana related her experience that Ghana’s laws promote females’ use on all boards. As a scientist, I am overwhelmed by the call to serve on so many committees needing a scientist. Too many offers that I cannot meet all of them facilitate—the organization provides mentoring courses”.(P1/Ghana/55–64)

“My organization does not hinder leadership, but support staff in a leadership position, and because of the culture of my colleagues at work, the framework of the organizational culture does not discriminate against women leaders. On the contrary, it encourages female participation in leadership roles. Most of the discrimination stems from individual perception”.(P35/Sudan/55–64)

“Sometimes decision making is not easy because of bureaucratic procedures”.(P48/Uganda/35–44)

“Academic credentials have a higher say in determining whether you could be a leader in the organization or not. Therefore, I have could look out and create my own space of influence out of the organization. In Kenya, for instance, there is affirmative action to ensure that there is equal opportunity for each gender in leadership positions. Thus, ensuring that more women are now given leadership positions and has allowed me to prove that they are capable of delivering on my mandate”.(P26/Kenya/35–44)

“The organizational culture facilitates my integration in my institution and allows me to be more confident by being friendlier and understanding”.(P40/Cameroun/35–44)

“Being born and grow-up in Soweto, where the community is mixed (all cultures included). And that freedom of knowing that we are all human beings first before you are a Zulu, Xhosa, or any tribe helped break cultural barriers. I speak most South African languages, including Afrikaans, which is a strength in my leadership. Also, the institution facilitates administration in that from the topmost bosses is a woman, and most Departments have a woman leader or boss encouraging our growth as women leaders. It facilitates when the organization is supportive and hinders when some unpalatable bottlenecks are brought into play that may slow down the work pace. Thus, the organization believes that whatever a man can do, a woman can do much better. So, that has allowed women to be in a critical position in the system”.(P27/South Africa/65–74)

“Male dominance hinders leadership. Sometimes men do not give me equal opportunities as men, but still, I press forward, not minding what happens. Sometimes they deny me some rights, but I was hesitant and not discouraged. I keep moving forward. Men are preferred because of the culture of the people I work with”.(P23/Nigeria/55–64)

5. Discussion

6. Limitations, Recommendations, and Managerial Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akter, Sonia, Pieter Rutsaert, Joyce Luis, Nyo Me Htwe, Su Su San, Budi Raharjo, and Arlyna Pustika. 2017. Women’s empowerment and gender equity in agriculture: A different perspective from Southeast Asia. Food Policy 69: 270–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audenaert, Mieke, Philippe Carette, Lynn M. Shore, Thomas Lange, Thomas Van Waeyenberg, and Adelien Decramer. 2018. Leader-employee congruence of expected contributions in the employee-organization relationship. The Leadership Quarterly 29: 414–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, Bruce J., Fred O. Walumbwa, and Todd J. Weber. 2009. Leadership: Current theories, research, and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology 60: 421–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, LouAnn. 2003. Circle of healing: Traditional storytelling, part one. Arctic Anthropology 40: 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boahene, Lewis Asimeng. 2013. The social construction of sub-Saharan women’s status through African proverbs. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 4: 123. [Google Scholar]

- Bowie, Jennifer Barnes, Donald R. Songer, and John Szmer. 2014. The View from the Bench and Chambers: Examining Judicial Process and Decision Making on the US Courts of Appeals. Charlottetown: University of Virginia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brescoll, Victoria L. 2016. Leading with their hearts? How gender stereotypes of emotion lead to biased evaluations of female leaders. The Leadership Quarterly 27: 415–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, Ann, and Marianne Coleman. 2019. Research Methodology in Educational Leadership and Management. Oxford: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chizema, Amon, Dzidziso S. Kamuriwo, and Yoshikatsu Shinozawa. 2015. Women on corporate boards around the world: Triggers and barriers. The Leadership Quarterly 26: 1051–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W. 2009. Editorial: Mapping the field of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 3: 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, Michael, and Dena Phillips Swanson. 2010. Educational resilience in African American adolescents. The Journal of Negro Education 79: 473–87. [Google Scholar]

- Dambrin, Claire, and Caroline Lambert. 2012. Who is she and who are we? A reflexive journey in research into the rarity of women in the highest ranks of accountancy. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 23: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, Nilanjana, and Jane G. Stout. 2014. Girls and women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences 1: 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, Belle, Colette Van Laar, and Naomi Ellemers. 2016. The queen bee phenomenon: Why women leaders distance themselves from junior women. The Leadership Quarterly 27: 456–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, Alice H., and Mary C. Johannesen-Schmidt. 2001. The leadership styles of women and men. Journal of Social Issues 57: 781–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, Alice H., and Madeline E. Heilman. 2016. Gender and leadership: Introduction to the special issue [Editorial]. Leadership Quarterly 27: 349–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, Caren. 1996. Achieving despite the odds: A study of resilience among a group of Africa American high school seniors. Journal of Negro Education 65: 181–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furr, R. Michael. 2008. A framework for profile similarity: Integrating similarity, normativeness, and distinctiveness. Journal of Personality 76: 1267–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furst, Stacie A., and Martha Reeves. 2008. Queens of the hill: Creative destruction and the emergence of executive leadership of women. The Leadership Quarterly 19: 372–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, Jessica, Guy Grossman, and Amanda Lea Robinson. 2018. Do men and women have different policy preferences in Africa? Determinants and implications of gender gaps in policy prioritization. British Journal of Political Science 48: 611–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouws, Amanda. 2008. Obstacles for women in leadership positions: The case of South Africa. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 34: 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Rachel A., and Lewis Asimeng-Boahene. 2006. Culturally responsive pedagogy in citizenship education: Using African proverbs as tools for teaching in urban schools. Multicultural Perspectives 8: 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groysberg, Boris, and Robin Abrahams. 2014. Manage our work, manage your life. Harvard Business Review 92: 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Guramatunhu-Mudiwa, Precious. 2010. Addressing the Issue of Gender Equity in the Presidency of the University System in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Region. Forum on Public Policy Online. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ903581 (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Hoyt, Crystal L., and Susan E. Murphy. 2016. Managing to clear the air: Stereotype threat, women, and leadership. The Leadership Quarterly 27: 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Stefanie K., Susan Elaine Murphy, Selamawit Zewdie, and Rebecca J. Reichard. 2008. The strong, sensitive type: Effects of gender stereotypes and leadership prototypes on the evaluation of male and female leaders. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 106: 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karelaia, Natalia, and Laura Guillén. 2014. Me, a woman and a leader: Positive social identity and identity conflict. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 125: 204–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kark, R., R. Waismel-Manor, and B. Shamir. 2012. Does valuing androgyny and femininity lead to a female advantage? The relationship between gender-role, transformational leadership, and identification. The Leadership Quarterly 23: 620–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolpakov, Aleksey, and Eric Boyer. 2021. Examining gender dimensions of leadership in international nonprofits. Public Integrity 23: 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladegaard, Hans J. 2011. Stereotypes and the discursive accomplishment of intergroup differentiation: Talking about ‘the other’in a global business organization. Pragmatics 21: 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemoine, G. James, Ishani Aggarwal, and Laurens Bujold Steed. 2016. When women emerge as leaders: Effects of extraversion and gender composition in groups. The Leadership Quarterly 27: 470–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lituchy, Terri R., Bella L. Galperin, and Betty Jane Punnett. 2017. LEAD: Leadership Effectiveness in Africa and the African Diaspora. Berlin: Springer, pp. 1–270. [Google Scholar]

- Mama, Amina, and Margo Okazawa-Rey. 2012. Militarism, conflict and women’s activism in the global era: Challenges and prospects for women in three West African contexts. Feminist Review 101: 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, Claude-Hélène, Rudolf M. Oosthuizen, and Sabie Surtee. 2017. Emotional intelligence in South African women leaders in higher education. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology 43: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, Ebony O., and Lydia Bentley. 2017. The troubled success of black women in STEM. Cognition Instruction 35: 265–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, Ebony Omotola. 2016. Devalued Black and Latino racial identities: A byproduct of college STEM success. American Educational Research Journal 53: 1626–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, Hazel, Jo Silvester, Diana Bilimoria, Sophie Jané, Ruth Sealy, Kim Peters, H. Möltner, Morten Huse, and J. Goke. 2017. Women in power: Contributing factors that impact on women in organizations and politics; psychological research and bests practice. Organizational Dynamics 47: 189–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, Alyson, Amanda Sinclair, and Karen A. Jehn. 2017. Identities under scrutiny: How women leaders navigate feeling misidentified at work. The Leadership Quarterly 28: 672–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekongo, Pierrette Essama, Sylvie Kwedi Nolna, Marceline Djuidje Ngounoue, Judith Torimiro Ndongo, Mireille Ndje Ndje, Celine Nkenfou Nguefeu, Julienne Nguefack, Evelyn Mah, Amani Adjidja, and Barbara Atogho Tiedeu. 2019. The mentor–protégé program in health research in Cameroon. The Lancet 393: e12–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchneck, Beth, Jessi L. Smith, and Melissa Latimer. 2016. A recipe for change: Creating a more inclusive academy. Science 352: 148–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncube, Lisa B. 2010. Ubuntu: A transformative leadership philosophy. Journal of Leadership Studies 4: 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, Carla. 1997. Dispositions toward (collective) struggle and educational resilience in the inner city: A case analysis of six African-American high school students. American Educational Research Journal 34: 593–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospina, Sonia, and Erica Foldy. 2009. A critical review of race and ethnicity in the leadership literature: Surfacing context, power and the collective dimensions of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly 20: 876–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott-Holland, Catherine J., Jason L. Huang, Ann Marie Ryan, Fabian Elizondo, and Patrick L. Wadlington. 2014. The effects of culture and gender on perceived self-other similarity in personality. Journal of Research in Personality 53: 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, Laura. 2016. Championing institutional goals: Academic libraries supporting graduate women in STEM. The Journal of Academic Librarianship 42: 192–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, Ken, Michael D. Mumford, Ian Bower, and Logan L. Watts. 2014. Qualitative and historiometric methods in leadership research: A review of the first 25 years of the Leadership Quarterly. The Leadership Quarterly 25: 132–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflanz, M. 2011. Women in Positions of Influence: Exploring the Journeys of Female Community Leaders. Available online: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cehsedaddiss (accessed on 29 August 2019). [CrossRef]

- Phaneuf, Julie-Élaine, Jean-Sébastien Boudrias, Vincent Rousseau, and Éric Brunelle. 2016. Personality and transformational leadership: The moderating effect of organizational context. Personality and Individual Differences 102: 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poltera, Jacqui, and Jenny Schreiner. 2019. Problematising women’s leadership in the African context. Agenda 33: 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, Laura R., Diana E. Betz, and Denise Sekaquaptewa. 2013. The effects of an academic environment intervention on science identification among women in STEM. Social Psychology of Education 16: 377–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichl, Corinna, Michael P. Leiter, and Frank M. Spinath. 2014. Work–nonwork conflict and burnout: A meta-analysis. Human Relations 67: 979–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronay, Richard, William W. Maddux, and William Von Hippel. 2020. Inequality rules: Resource distribution and the evolution of dominance- and prestige-based leadership. The Leadership Quarterly 31: 101246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosette, Ashleigh Shelby, Christy Zhou Koval, Anyi Ma, and Robert Livingston. 2016. Race matters for women leaders: Intersectional effects on agentic deficiencies and penalties. The Leadership Quarterly 27: 429–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, Diana, Daan Van Knippenberg, and Barbara Wisse. 2010. Leader power and leader self-serving behavior: The role of effective leadership beliefs and performance information. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 46: 922–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, John M., and Ping Shao. 2012. The role of attribution in how followers respond to the emotional expression of male and female leaders. The Leadership Quarterly 23: 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotland, James. 2009. Exploring the philosophical underpinnings of research: Relating ontology and epistemology to the methodology and methods of the scientific, interpretive, and critical research paradigms. English Language Teaching 5: 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Smriti, and Finn Tarp. 2018. Does managerial personality matter? Evidence from firms in Vietnam. Journal of Economic and Behavior Organization 150: 432–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, Sanjay, Steve Guglielmo, and Jennifer S. Beer. 2010. Perceiving others’ personalities: Examining the dimensionality, assumed similarity to the self, and stability of perceiver effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 98: 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanton-Salazar, Ricardo D., and Stephanie Urso Spina. 2000. The network orientations of highly resilient urban minority youth: A network-analytic account of minority socialization and its educational implications. The Urban Review 32: 227–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stout, Jane G., Nilanjana Dasgupta, Matthew Hunsinger, and Melissa A. McManus. 2011. STEMing the tide: Using ingroup experts to inoculate women’s self-concept in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100: 255–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunstein, Cass, and Reid Hastie. 2014. Wiser: Getting beyond Groupthink to Make Groups Smarter. Brighton: Business Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Szelényi, Katalin, Nida Denson, and Karen Kurotsuchi Inkelas. 2013. Women in STEM majors and professional outcome expectations: The role of living-learning programs and other college environments. Research in Higher Education 54: 851–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiessen, Rebecca. 2008. Small victories but slow progress. International Feminist Journal of Politics 10: 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 2017. Women in Science Factsheet. Institute for Statistics. Available online: http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/fs43-women-in-science-2017-en.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Vial, Andrea C., Jaime L. Napier, and Victoria L. Brescoll. 2016. A bed of thorns: Female leaders and the self-reinforcing cycle of illegitimacy. The Leadership Quarterly 27: 400–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wille, Bart, Brenton M Wiernik, Jasmine Vergauwe, Amelie Vrijdags, and Nikola Trbovic. 2018. Personality characteristics of male and female executives: Distinct pathways to success? Journal of Vocational Behavior 106: 220–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Joseph M., and Tarrell Awe Agahe Portman. 2014. No one ever asked me”: Urban African American students’ perceptions of educational resilience. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development 42: 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehnder, Christian, Holger Herz, and Jean-Philippe Bonardi. 2017. A productive clash of cultures: Injecting economics into leadership research. The Leadership Quarterly 28: 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerer, Thomas W., and Mahmoud M. Yasin. 1998. A leadership profile of American project managers. Project Management Journal 29: 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Babalola, O.O.; du Plessis, Y.; Babalola, S.S. Insight into the Organizational Culture and Challenges Faced by Women STEM Leaders in Africa. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10030105

Babalola OO, du Plessis Y, Babalola SS. Insight into the Organizational Culture and Challenges Faced by Women STEM Leaders in Africa. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(3):105. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10030105

Chicago/Turabian StyleBabalola, Olubukola Oluranti, Yvonne du Plessis, and Sunday Samson Babalola. 2021. "Insight into the Organizational Culture and Challenges Faced by Women STEM Leaders in Africa" Social Sciences 10, no. 3: 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10030105

APA StyleBabalola, O. O., du Plessis, Y., & Babalola, S. S. (2021). Insight into the Organizational Culture and Challenges Faced by Women STEM Leaders in Africa. Social Sciences, 10(3), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10030105