Abstract

During March and April 2020, the European Union (EU) was the center of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many national governments imposed severe lockdown policies to mitigate the health crisis, but the citizens’ support to these policies was unknown. The aim of this paper was to analyze empirically how citizens in the EU have reacted towards the measures taken by the national governments. To this end, a microeconometric model (ordered probit) that explains the citizens’ satisfaction by a number of attitudes and sociodemographic factors was estimated using a wide database formed by 21,804 European citizens in 21 EU countries who responded a survey between 23 April and 1 May 2020. Our results revealed that Spaniards were the least satisfied citizens in comparison with Danes, Irelanders, Greeks, and Croats, who were the most satisfied nationals. The years of education and the social class also played a determinant role. We also found that the most important determinant was the political support to the government, and that those who were more worried by the economy and the protection of individual rights were usually more critical of the measures than those who were more worried by the health consequences.

1. Introduction

In December 2019, Chinese health authorities faced a group of severe cases of bilateral pneumonia in Wuhan City, located in Hubei province, China. The Wuhan local government announced a strict quarantine in the city with the complete closure of the urban and intercity transport network and Wuhan Tianhe airport. The World Health Organization (WHO) called the new infectious disease “COVID-19”and declared it as a global pandemic on 11 March 2020 (WHO 2020a, 2020b).

The official reactions to the pandemic were not uniform and some countries reacted with different speeds and measures that balanced healthcare with the economic damage. Nevertheless, the majority of the EU member states decreed lockdowns, mainly characterized by a strict and enforced confinement, in which citizens were obliged to stay at home with a limited number of essential activities exceptions. Other less restrictive measures included banning large gatherings; school closures; closure of bars, restaurants, and discos; and selective geographical mobility closures. Italy was the first country to close schools, on Wednesday 4 March (CGTN 2020). Andersson and Aylott (2020) reviewed the Swedish strategy for being more permissive and extremely different from the rest of the countries of the EU.

The containment of the pandemic spread was a key challenge to EU national governments, as not many successful examples existed in the world. At first, it was thought that the lockdown imposed by the Chinese Government in 16 cities of Hubei Province that affected 50 million people could not be easily transferred into more democratic regimes. For example, Bull (2020) contended that “managing a public health crisis in a democracy involves striking a balance between measures protecting citizens and the social and economic impact of those decisions—meaning democratic politics cannot be suppressed.” Similarly, Fetzer et al. (2020) contended that lockdowns reduce civil liberties, erode social capital, and create a lot of stress and uncertainty about the economic situation. Thus, it was highly expected that citizens’ attitudes towards the measures that suppress or limit, in part, some civil rights, and that affect the economic situation, might have an effect on the citizens’ support towards the measures themselves, the institutional trust, and even satisfaction with democracy (Katz and Levin 2016).

Unfortunately, the anti-COVID measures to reduce the spread of the pandemic imposed numerous costs to the economic situation, and social cost benefit analysis that could have helped policy makers to determine which measures would receive more citizens’ support did not exist. So far, the most restrictive lockdowns have affected significantly most of the economic sectors, but other less restrictive measures, such as social distancing, quarantines, and travel restrictions, have also reduced dramatically the employment of some economic sectors, such as tourism. In contrast, the demand for medical supplies has skyrocketed. The political agreement signed on 10 November 2020 between the European Parliament and the Council ensures the most ambitious recovery plan (€1.8 trillion), with the aim to mitigate the economic recession caused by the pandemic. This plan, with other instruments, will make the EU greener, more digital, more resilient, and better equipped for the current and forthcoming crises (European Commission 2020). The current cabinets have been advertising this recovery plan since the beginning of the pandemic as a life vest that would not leave any citizen behind.

In any case, the successful implementation of any containment measure will require public support. Van Bavel et al. (2020) made an explicit call for the scientific community to mobilize rapidly to produce research to directly inform policy makers about individuals and collective behavior in response to the pandemic. The authors selected a number of topics within the social context, as the pandemic control usually requires a significant change in social behavior. According to the authors, the extent and speed of the social behavioral change is affected by features such as social norms, social inequality, and culture and polarization.

Regarding social norms, this paper aimed to contribute to the literature concerning how different traits, such as sociodemographic variables and attitudes, can affect the degree of citizens’ support towards the different measures taken by national governments to control the COVID-19 in the EU. Thus, we analyzed the support measured by the answers given to question Q2 of the survey: “How satisfied or not are you with the measures your national government has taken so far against the coronavirus pandemic?” The main determinants were studied according to a set of covariates that included sociodemographic factors such as country, gender, age, household size, no children present in the household, marital status, years of education, social class, and job status, in addition to citizens’ attitudes such as voting participation in the last EU elections, national government support, personal position on whether health benefits are greater than economic damage, personal position on being in favor of limit individual rights, the use of apps to track people, own health concerns, others’ health concerns, being affected by some economic loss, do need help from others, do help others, do talk more to others, and do engage online in COVID debates. Thus, our study provides interesting insights with respect to the identification of the determinant factors that affect the citizens’ satisfaction experienced by the containment measures taken by the EU national governments to control COVID-19.

Our study presents several advantages over other existing studies. First, we directly examine the degree of citizens’ support measured by the satisfaction experienced with the measures taken by the national governments so far to control the pandemic. Other studies have examined a similar topic with presidential vote intention or institutional trust as dependent variables (Bol et al. 2020; Harell 2020; Leininger and Schaub 2020; Merkley et al. 2020; Schraff 2020). In this sense, Devine et al. (2020) contended that the pandemic has presented a unique opportunity to analyze the main theories in the trust literature. Second, our dataset was based on individual answers from a broad survey administered in 21 different EU countries, meanwhile the majority of the previous studies were only based in one country, so multinational comparisons were still scarce. In our case, it was possible to analyze the existing differences at a national level. Third, we considered a very extensive set of potential explanatory variables that included interesting individual attitudes as well as social effects caused by the current pandemic. We also considered sophisticated covariates that measured the degree of acceptance of measures that limited the individual civil rights—movement bans and the use of people tracking apps.

2. Literature Review

Amat et al. (2020) contended that the current pandemic poses an unprecedented number of challenges to modern democracies, including a massive global public health problem, an unknown economic recession, and containment measures that subtly border and suppress civil democratic liberties. Empirical evidence has shown that governments in charge during natural disasters, financial crisis, or economic downturns (Achen and Bartels 2017; Katz and Levin 2016; Margalit 2019; Flores and Smith 2013) are usually punished in the next election unless they have shown proficiency and efficiency in the crisis management (Ashworth et al. 2018; Besley 2007) or they have allocated enough donations and humanitarian aid that mitigate substantially the economic loss of the most affected households (Cole et al. 2012; Gallego 2018). The last mechanism that gives politicians in cabinet an incumbent advantage is known in the literature as clientelism and consists of guaranteeing the votes of those voters who have received the humanitarian aid.

Mauk (2020) addressed whether modern societies are facing a real democracy crisis, in which citizens are developing a new political and cultural preferences that are undermining the up-to-now consolidated support for democratic regimes. The author highlighted some events that appeared in Hungary, Poland, the Philippines and, most eminently, Turkey as examples of this observed trend. At the same time, the number of ‘critical citizens’ or ‘dissatisfied democrats’ are nowadays increasing in some of the most consolidated democracies of the western societies. In addition, the rise of populist, anti-democratic, and far-right wing parties are also shaking the political scene of the democracies in much of Western Europe. The recent Capitol attack on 6 January 2021 made by a pro-Trump rally can also be framed on this commented trend.

Thus, the current pandemic is further agitating the political arena and will renew the interest of how firm citizens’ support for the measures taken by the respective national governments really is. After the apparent success of the Chinese Government to control the disease, the democracies in the EU are highly scrutinized by the Europeans. European citizens are nowadays evaluating whether the measures have or have not been taken with enough anticipation, are giving more priority to maintaining the health system over the economy or vice versa, and have or have not been coordinated at the EU level. The citizens have still many unanswered questions.

Evidently, it is still too early to find enough literature that analyzes the drivers of the political support towards the measures taken by distinct levels of government to control the current pandemic. The methods have ranged from social media and survey experiments to observational data. The majority of the studies have analyzed only one country, with the exception of Bol et al. (2020), who analyzed 15 Western European countries during a period in which seven countries imposed national lockdowns. The authors found that incumbents have benefited from the implemented measures as the vote intention for the current cabinet has increased by about four points, and trust in government and satisfaction with democracy by about three points. The authors concluded with a clear demonstration of “the retrospective evaluation of performance mechanism: it seems that citizens have understood that lockdowns were necessary and rewarded those responsible for them (p. 2).”

The results of other studies (Harell 2020; Leininger and Schaub 2020; Merkley et al. 2020; Schraff 2020) have been concordant with those found by Bol et al. (2020) with respect to the fact that the health crisis has benefited the incumbent political parties. In fact, Schraff (2020) found that collective angst caused by the pandemic led citizens to convert existing institutions into life vests. On the other hand, the study by Amat et al. (2020) was the exception, as the authors claimed that the crisis may trigger a paradigmatic political attitudes change. In addition, partisanship has been found to be an important political driver to support strict lockdown measures (Andersen 2020; Kushner et al. 2020; Grossman et al. 2020) in the case of the United States.

Thus, many studies have shown that citizens’ support to the anti-COVID measures taken by regional and national governments might be driven not only by the perceived health risks, but also by the economic damage and other attitudinal variables that can be linked with personal values, social norms, and partisanship. These attitudinal variables can also be affected by other sociodemographic variables, such as age and income. Our analysis was mainly constrained by data availability. In this sense, we could not include institutional trust or satisfaction with democracy as dependent variables like other previous studies, such as Bol et al. (2020). Meanwhile, we note that all the variables included in our models were based on individual answers and not on aggregated data constructed from social media, geolocation data, or google trends at some demarcation scale, such as county, region, or state, which have been used by other studies such as Andersen (2020) and Grossman et al. (2020).

There are different theories that underpin our study and the studies presented above. One of the main theories that can be first cited is the organizational learning theory (Argote 2012), in which the distinct government layers establish processes that create, retain, and transfer knowledge within the organizations. Secondly, there are theories of democratization in which the negative economic shocks are seen as opportunities for setting up democracies or for changing the political regimes (Acemoglu and Robinson 2001). Finally, the perspective of materialist state theory and state power (Jessop 2019), in which the state can be seen either as an executive committee of the elite class or a relative autonomous social organization capable of looking after the public interest, is also interesting due to the nature of the EU and its member states.

3. Data and Variables

Our empirical analysis was based on a dataset obtained from the administration of a survey that analysed the European citizens’ attitudes and opinions over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey was commissioned by the European Parliament and produced by Kantar (Zalc and Maillard 2020). The survey was conducted using Kantar’s online access panel between 23 April and 1 May 2020, and 21,804 respondents in 21 EU member states were finally gathered. Six member states—Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia, Cyprus, Malta, and Luxembourg—were not covered in the analysis. The survey was limited to respondents aged between 16 and 64 for the majority of the countries, except for Bulgaria, Czechia, Croatia, Greece, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, and Slovakia, where the respondents’ age was between 16 and 54. Representativeness at the national level was ensured by quotas on gender, age, and region. The sample error at national level was guaranteed to be lower than 3.1 at a confidence level of 95 percent due to the sample size of about 1000 interviews (Table A1).

At the time of the survey’s fieldwork, some measures taken against the pandemic were softly modulated in some countries, such as Denmark, Germany, and Austria, while in others like, for example, Italy and Spain, strict lockdown restrictions still persisted. The questionnaire was structured in four parts: (1) how EU citizens are coping with the crisis; (2) attitudes towards European action; (3) attitudes towards the national response; and (4) personal situation and individual freedoms. As said, the construction of the dependent variable for the econometric model was based on the answers given to the question Q2 of the survey: “How satisfied or not are you with the measures your national government has taken so far against the coronavirus pandemic?”

Table A2 in the Appendix A shows the explanatory variables that were used in the econometric model. It can be seen that there were 97 dummy variables and eight base categories for sociodemographic determinants that corresponded to: (1) country (Spain), (2) gender (male), (3) household size (one person), (4) children present in the household (yes), (5) marital status (married or living with partner), (6) terminal age of education (16 years or younger), (7) social class (semi or unskilled manual worker), and (8) employment status (employed full time—30 or more hours per week). In addition, we also included in the model 12 more variables and the corresponding base categories were: (1) the participation in the last 2019 May EU Election (voted); (2) national government support in general (totally support); (3) personal position regarding whether the health benefits are greater or not than the economic damage (the health benefits are greater than the economic damage); (4) personal position regarding the recent limitations to individual freedom (the fight against the coronavirus pandemic fully justifies recent limitations to my individual freedoms; (5) personal position regarding the use of apps to fight the virus expansion (strongly in favor); (6) own health concern because of the coronavirus (very concerned); (7) health concern of family and friends because of the coronavirus (very concerned); (8) economic loss caused by the pandemic (no); (9) respondents receive help from people around them (yes, definitely); (10) respondents help other people in need (yes, definitely); (11) respondents are talking more often to people on phone, social media, or apps (yes, definitely); (12) respondents engage online in debates on the measures applied against the coronavirus.

The answer format scale for the question Q2 was based on a five-point semantic ordered scale formatted according to: (1) not at all satisfied, (2) not very satisfied, (3) don’t know/not applicable, (4) fairly satisfied, and (5) very satisfied. A majority of respondents (56%) said they were satisfied with the measures their government has taken so far against the coronavirus pandemic, including 18% who said they are ‘very satisfied’. However, 34% said they are not satisfied, and this includes 12% who said they are ‘not at all satisfied’. The degree of satisfaction varied by country (highest in Denmark and Ireland, and lowest in Spain, Poland, and France).

The answer format scale for the independent variables can be extracted from Table A2. For example, it can be seen that for the social class variable, the response options were based on an eight-point semantic scales according to: (1) semi or unskilled manual worker, (2) skilled manual worker, (3) supervisory or clerical/junior managerial/professional/administrator, (4) intermediate managerial/professional/administrative, (5) higher managerial/professional/administrative, (6) student, (7) retired and living on state pension only, (8) unemployed (for over six months) or not working due to long-term sickness. For brevity and document extension, we omitted the rest of the format answer scales.

4. Methodology, Econometric Model

The dependent variable for the econometric model was based on the answers given by the respondents to Q2, which dealt with the satisfaction experienced on the measures taken by the governments against the coronavirus. As the responses were given on an ordinal scale of 5 points, we decided to use a heteroskedastic ordered probit model as the best approach to analyze the main determinants to explain the citizens’ support. Homoscedastic ordered probit models assume that error variances are constant across observations, and this is a very strong assumption that can lead to biased parameter estimates in addition to miss-specified standard errors, so the analysis of heteroskedastic ordered probit models has been highly recommended (Reardon et al. 2017). Some authors have also speculated that unmeasured variables can affect more the probability of support for some segments, such as, for example, those partisans of the current cabinet than for others who are not partisans, in which case it would be inappropriate to consider that the model is homoscedastic (Williams 2010).

In the current study, the heteroskedastic ordered probit model can be explained as the result of a latent variable model. Let y denote the random variable whose value ranges from 1 to 5, and the order of the values means that citizens are more satisfied with the anti-COVID-19 measures taken by the respective governments. Thus, the nature of the latent variable y* is determined by:

where x is a 1 × 97 vector formed by the dummy variables included in the model as the determinant factors, β and δ are two 97 × 1 vectors of parameters to be estimated by the model, is the error term that distributes as a standard normal distribution, and is the scale parameter that allows the variance of the error term to vary for the heteroskedastic models. The model now determines four threshold parameters that permit to link the observed dependent variable with the unobserved latent variable as follows:

The parameters are estimated by maximizing, as usual, the log-likelihood functions, which are consistent and asymptotically normal. The use of ordered probit models has been proven to be adequate when the dependent variable is categorical, but the categories represent a relative order, which is unknown (Greene and Hensher 2010). In this case, researchers reasonably hypothesized that there was a continuous latent variable that determined the citizens’ support towards the measures taken by the national governments. The translation from the latent variable y* to a rating could be viewed as the transformation presented in Equation (2). Therefore, the observed answers given to Q2 represent a censored version of the true underlying individual support. It is important to highlight that the differences between the categories of the Likert scale do not need to be the same on the scale determined by the thresholds.

There are a number of issues that need to be decided before the estimation. For example, it is necessary to decide in which way categorical variables are entered into the model. For example, the social class has eight different categories, and the impact of moving from one category to a different one needs to be captured by the model. The literature has addressed this issue using mainly dummy or effects coding. In this study, we used the common dummy coding that consists in recoding the categorical variable into eight dummy variables. To make the model identifiable, it is necessary to omit some dummy variable from the estimation process. This is equivalent to assuming that the constrained parameter is zero for a base category. In the case of the social class, the base category was fixed to semi or unskilled manual worker. A similar procedure was followed for each of the categorical variables included in the model, and all the categories with the respective base for each one can be consulted in Table A2.

5. Results

Table A3 and Table A4 in the Appendix A report both the estimation results for the homoscedastic and heteroskedastic models. The homoscedastic model is characterized by a constant in Equation (1). The signs of the parameters estimated in the homoscedastic model are informative as the sign determines the marginal effects for outcomes at the extreme of the distribution (not at all satisfied and very satisfied), but not for the intermediate outcomes (not very satisfied, don’t know/not applicable, and fairly satisfied). A brief first analysis of the Table A3 shows that: (1) all the nationalities seemed to be happier than Spanish; (2) females were happier than males; (3) larger households were less supportive than single households; (4) the presence of children in the household did not affect the citizens’ support; (5) marital status did not affect citizens’ support; (6) education did not affect citizens’ support; (7) retired people were less supportive than unskilled manual worker; (8) self-employed and unemployed citizens were a little bit less supportive than those who work full time; (9) the citizens who did not vote in the last EU election were less supportive than those who participated; (10) citizen who were less partisans of the national government were less supportive than those who were partisans; (11) the citizens who thought that the economic damage was greater than the health benefits were less supportive than those who thought the opposite; (12) the citizens who opposed more to any limitation of the individual freedoms were less supportive than those who favored the taken limitations; (13) those who were less in favor of the use of trace apps to control the pandemic were less supportive than those who were in favor of the use; (14) the less concerned citizens were about their own health, the more supportive they were; (15) the concern about family and friends did not affect the support; (16) the citizens who had experienced some economic loss were less supportive than those who have not; (17) the citizens who have needed less help from others were less supportive than those who have needed help; (18) the attitude of helping others did not affect the support; (19) there was not a clear sign for the attitude of talking more to others during the pandemic; (20) and there was no trend for having participated in debates online about the measures taken by the government either.

In the heteroskedastic model (Table A4), the absolute magnitude of the estimated parameters was uninformative, and for that reason, the marginal effects of the determinants on the probability of the outcome of being very satisfied will be commented on. In this case, the marginal effects depended on the sign of the relevant coefficients, the relative value of the mean of the latent variable, and the respective threshold parameters.

It can be seen that many coefficients for the countries are significant in both the latent model and the observed heterogeneity. For the rest of the determinants included in the analysis, there was at least one coefficient in the set of the dummy variables of each determinant for which the coefficient for the latent model or the variance was significant. In this respect, we also comment here that age was finally eliminated from the models as it was insignificant. All the threshold parameters were also significant. Finally, we tested whether the heteroskedastic model was statistically different from the homoscedastic model using a likelihood ratio test concluding, unsurprisingly, that the heteroskedastic model was different and improved significantly the model fit (Df = 97, Chisq = 1071.3, Pr > 2.2·10−16 ***). The marginal effects are also included in the table, but in order to summarize as much as possible the results, we only highlight the marginal effects of the outcome 5, which was associated with being very satisfied with the measures.

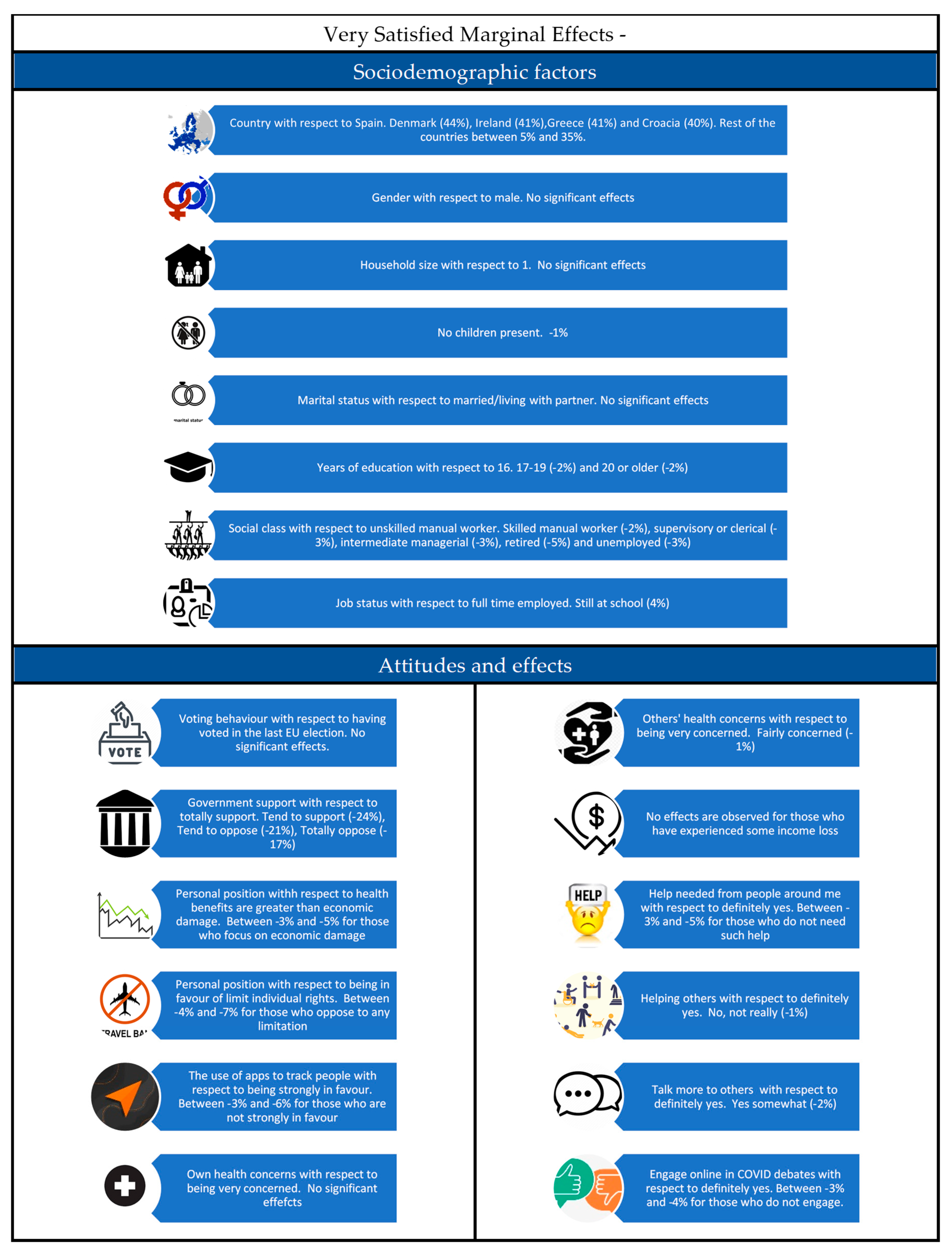

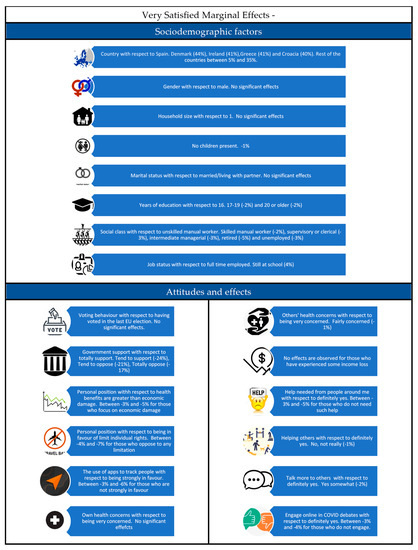

Figure 1 presents, schematically, the summary of the results. It can be seen that the following determinants did not present significant effects: (1) gender, (2) household size, (3) marital status, (4) voting behavior in the last EU election, (5) own health concerns, or (6) having experienced some economic loss. In summary, from the 20 variables included in the analysis, we concluded that six variables did not have any significant effect on the probability of being very satisfied with the measures against COVID-19 taken by the government. Analyzing now the positive drivers respective to the base categories, we found that: (1) with respect to Spain, the rest of the nationalities had a higher probability of being very satisfied, especially Danes (44%), Irish and Greeks (41%), and Croatians (40%); (2) respondents who were still at school had a higher probability of four points of being very satisfied than full-time employees. Finally, we present the negative results, that is those cases who had less probability of being very satisfied with respect to the base category:

Figure 1.

Marginal effects for the experienced satisfaction with the measures taken by the government. (Very Satisfied).

(1) The households with no children had one percent less probability of being very satisfied than the households with children; (2) those who had more years of education had two points less probability of being very satisfied than those who ended the education with 16 years or less; (3) with respect to unskilled manual workers, there were at least five classes that had less probability of being very satisfied, especially retired people, who had five points less; (4) with respect to total governmental support, an effect of the lower partisanship citizens showing lower support for the measures was seen (−24% and −17%), but the relationship was not linear; (5) the citizens who focused more on the economic damage than on the health benefits had a lower probability (three and five percent) of being very satisfied in comparison with those who contrarily focus more on the health benefits than on the economic damage; (6) the opposition to limiting any individual right decreased the probability of being very satisfied in the range of four and seven points in comparison with those who were in favor of the limitation; (7) a very similar pattern was observed for those who opposed the use of apps to trace people (−3% and −6%) in comparison with those who were in favor of the use; (8) those who were fairly concerned about the health of others (family and friends) had one percent less probability of being very satisfied than those who were very concerned; (9) the citizens who definitely did not need help had less probability of being very satisfied (−3% and −5%) than those who were in such a need; (10) those who were not really helping others had one percent less probability of being very satisfied than those who definitely were helping others; (11) those who were talking somewhat more to others during the pandemic had two percent less probability of being very satisfied than those who definitely were talking more to others; and (12) those citizens who were less proactive in engaging in online debates about the pandemic measures had less probability (−3% and −4%) of being very satisfied than those who are very participative.

6. Discussion

Grossman et al. (2020) contended that governments play a central role in controlling pandemics by adopting different measures that impose costs and sacrifices to citizens. The coordination of the response measures of multiple layers of governmental agencies and entities is also crucial. This study analyzed the main determinants that explain the satisfaction experienced by citizens in 21 EU countries towards the anti-COVID-19 measures taken by the governments. Figure 1 shows that there were 14 determinants (sociodemographics, attitudes, and effects) that significantly affected the probability of being very satisfied with the anti-COVID-19 measures taken by the respective 21 countries in the EU included in the analysis. By magnitude order, the main determinants observed were country differences, general support to governments (partisanship), and position of being in favor or not of civil rights limitations.

Amat et al. (2020) contended that the response to the pandemic has been mostly handled at national level, that the leadership of the EU has not existed, and even competition among member states to buy in the stressed medical supplies market has existed. Similarly, the pandemic has brought to light an important feature of the divisive union regarding the capacity to respond to the health crisis (Celi et al. 2020). Unfortunately, we cannot compare our results regarding the country differences obtained, as to our knowledge, this is the first study analyzing multinational responses. We can only speculate that the causes of observed differences between Spain and the rest of the countries could be rooted in three distinct categories: (1) the weak support that the government coalition (Partido Socialista Obrero Español-Podemos) has in the national parliaments (155 out of 350); (2) the strong support that separatist parties have in some regions of Spain, especially Catalonia and the Basque Country; and (3) the lack of resources that the Health Alert and Emergency Coordination Centre has to coordinate a total decentralized health national system of 17 very different regional health systems. Legido-Quigley et al. (2020) found five important lessons that can be drawn to combat the pandemic: (1) regional health systems need more financial resources; (2) the long term underinvestment in health services has stressed has impaired the system in the moment of necessity; (3) Spanish residents have responded very professionally so far, but their demands need to be attended to guarantee this conduct in the near future; (4) different government layers need to be better coordinated and politicians should not extract situational rents; (5) Spain will need to rearm its previously strong health sector.

In line with previous studies, we found that the degree of partisanship influences the support level (Kushner et al. 2020; Grossman et al. 2020). Partisanship can be measured in different ways, such as with political party affiliation or sympathy, intended vote choice for the next election, ideological position, mass media readership and viewership, or general government support. Theodoridis (2017) contended that party identification (PID) is profusely handled in the political behavior literature, but its conceptualization and proper measurement is still in progress.

Andersen (2020) measured partisanship by the counties’ vote for Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton in 2016 US President Election and also by Fox News viewership. The author found that individuals in counties that supported Hillary Clinton in 2016 reduced their visits outside by an additional 0.13 percent per day, compared to counties that supported Donald Trump. Similarly, the author demonstrated that a one percentage point increase in in Fox News viewership was associated with 0.06 percent more visits per day. Kushner et al. (2020) measured partisanship with the sympathy degree to Democrats, Republicans, and others measured with the PID scale, and found that partisanship was the single most consistent factor that explained the political support of the measures, and suggested that the public health message needs to take this into account for being decisive. The authors found strong evidence that relative to Republicans, Democrats were more significantly likely to report having adopted a number of health behaviors that included, among others, washing hands more, using sanitizers, avoiding contact with others and gatherings, and searching information on COVID-19. Similarly, Democrats, relative to Republicans, exhibited more worrying attitudes about the pandemic. More interestingly, regarding the public health measures, the authors found that Democrats were much more likely to support all the measures related to physical distance, such as cancelling public events, closing schools, and facilitating paid sick leaves. Regarding bans and travel limitations, Democrats were less supportive than Republicans with respect to air travel restrictions, banning entry from China/UK/Italy, closing the Mexican border, putting in quarantine people travelling from China and Italy. Grossman et al. (2020) measured partisanship with past electoral returns at the county level (using Trump votes in the 2016 presidential election) and analyzed how partisanship mediated the relationship between governors’ COVID-19 communications and residents’ engagement in physical distancing. The authors found that governors’ tweet messages that suggest voluntary “stay home” measures had a significant effect on residents’ mobility, and the effects were more intense in Democratic counties. Interestingly, they also observed that Democratic counties were more responsive to Republican governors than Republican counties. The authors showed that, on average, Democratic governors have been encouraging “staying at home” messages earlier than Republican governors.

The measures taken that limit civil rights can be analyzed from multiple lenses. For example, Amat et al. (2020) contended that the pandemic is seen as an opportunity for governments to centralize, to accumulate power, and to increase surveillance and citizens’ control beyond democratic borders, as citizens are normally willing to exchange civil rights for more protection and pandemic control. The authors found that Spanish citizens were willing to support drastic measures even if they curtail basic civil liberties, and the anti-COVID-19 measures were more drastically supported than those measures taken against climate change or terrorism. Meanwhile, Tepe et al. (2020) analyzed the policy tradeoff preferences of Germans to the response to COVID-19 to minimize the number of deaths, with two interesting treatments giving information to the respondents about the associated costs in terms of: (1) the economy frame—loss of economic wealth caused by insolvencies, unemployment, and public debt; and (2) the freedom frame—long term restrictions of civil liberties (assembly and movement freedoms). The authors found that both treatments reduced the support of the life-saving measures and the economy frame reduction was greater than the freedom frame. Our results were a little bit different, as we have found that, in Tepe’s frames, the marginal effects reduction of being very satisfied with the measures were greater in the case of “freedom” than in the case of “economy”. Our results are not directly comparable as we were only analyzing the tail of the distribution and Tepe’s results were made taking into account the whole sample, considering no effects and two treatments.

7. Conclusions

Based on a broad dataset from a survey of citizens of 21 EU member states, this paper empirically tested the individual support towards the anti-COVID-19 measures taken by the national governments, which have been characterized by lockdowns that impose strict and enforced confinements in which citizens were obliged to stay home with a limited number of essential activities exceptions such as going to work, buying groceries or exercising individually in a surrounding area of the home location. The support varied very much by country, because the pandemic effects have also varied in different countries of the EU, affecting Italy and Spain more intensely. The lockdowns have been highly contested by some groups, which include refuted epidemiologists that especially emphasized the economic damage and the limitation of civil rights. Given this context, the study econometrically examined whether twenty determinants, including sociodemographic factors, attitudes, and COVID-19 individual effects, affected the citizens’ support.

Our micro-econometric analysis, based on a heteroskedastic ordered probit model, showed that there are 14 determinants that affect the highest citizens’ support (those who manifested to be very satisfied) towards anti-COVID-19 measures taken by governments in 21 EU countries. On the other hand, six determinants, namely gender, household size, marital status, voting behavior in the last EU election, own health concerns, and having experienced some economic loss, did not significantly affect the highest citizens’ support. The results provide valuable insights on how the measures have been: (1) more supported in some countries such as Denmark, Ireland, Greece, and Croatia in comparison with Spain; (2) less supported by those citizens who are not partisans of the respective government in each country; (3) less supported by citizens who have a personal position of neither limiting civil rights nor using trace apps; and (4) less supported by those who think that the economic damage is greater than the health benefits regarding the consequences of the anti-COVID-19 measures. Important lessons can be taken to respond to future pandemics. In this respect, as the partisanship seems to play a relevant role in supporting the government measures, it will be crucial for future pandemics to explore the role that “rally around the flag” (Hetherington and Nelson 2003) can play with more unanimous support in the national parliaments, or even in the European Parliament, giving a more prominent role to the European Institutions.

In line with other studies (Reardon et al. 2017), our econometric analysis methodologically clearly supported the empirical evidence regarding the use of more simple homoscedastic ordered probit specifications to analyze the main determinants that explain the acceptance of policy measures, as these can mislead the results and distort the conclusions. For example, the gender plays a very different role when the heteroscedastic model is used instead of the homoscedastic model.

This study presents a number of possible extensions for future research. For example, the possible negative effects of lockdowns on mental and physical health and subjective well-being of citizens is an interesting research area (Sibley et al. 2020). Winter et al. (2020) assessed and validated in English the Fear of COVID-19 scale. The authors found that the scale was negatively correlated with well-being and with the citizens who reported themselves as more conservative. In addition, more sophisticated econometric models that included some interaction between the explanatory variables and heterogeneity in the threshold parameters or in the explanatory variables using random parameters can be also an interesting line for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.M.; Formal analysis, J.C.M.; Methodology, J.C.M. and C.R.; Software, C.R.; Writing—original draft, J.C.M.; Writing—review & editing, C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The online panel survey was conducted for the European Parliament by Kantar.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data was facilitated by the Public Opinion Monitoring Unit. Directorate-General for Communication. European Parliament.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sample features.

Table A1.

Sample features.

| Country | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| France | 1054 | 4.8 |

| Germany | 1054 | 4.8 |

| Spain | 1054 | 4.8 |

| Italy | 1054 | 4.8 |

| Netherlands | 1046 | 4.8 |

| Belgium | 1046 | 4.8 |

| Austria | 1041 | 4.8 |

| Poland | 1051 | 4.8 |

| Sweden | 1041 | 4.8 |

| Finland | 1049 | 4.8 |

| Denmark | 1025 | 4.7 |

| Bulgaria | 1020 | 4.7 |

| Croatia | 1029 | 4.7 |

| Czech | 1011 | 4.6 |

| Greece | 1050 | 4.8 |

| Hungary | 1043 | 4.8 |

| Ireland | 1019 | 4.7 |

| Portugal | 1026 | 4.7 |

| Romania | 1017 | 4.7 |

| Slovakia | 1035 | 4.7 |

| Slovenia | 1039 | 4.8 |

| Total | 21,804 | 100.0 |

Table A2.

Definitions of the independent variables.

Table A2.

Definitions of the independent variables.

| Variable | Categories | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 21 country dummy variables | Country1 | France |

| Country2 | Germany | |

| Country3 (Base) | Spain | |

| Country4 | Italy | |

| Country5 | Netherlands | |

| Country6 | Belgium | |

| Country7 | Austria | |

| Country8 | Poland | |

| Country9 | Sweden | |

| Country10 | Finland | |

| Country11 | Denmark | |

| Country12 | Bulgaria | |

| Country13 | Croatia | |

| Country14 | Czech | |

| Country15 | Greece | |

| Country16 | Hungary | |

| Country17 | Ireland | |

| Country18 | Portugal | |

| Country19 | Romania | |

| Country20 | Slovakia | |

| Country21 | Slovenia | |

| 4 gender dummy variables | Gender1 (Base) | Male |

| Gender2 | Female | |

| Gender 3 | I don’t identify as either | |

| Gender4 | Prefer not to answer | |

| 4 household size dummy variables | HHsize1 (Base) | 1 |

| HHsize 2 | 2 | |

| HHsize 3 | 3 | |

| HHsize 4 | 4 or more | |

| 1 no children present in the household dummy variable | Ch_Presence(N) | There are no children in the household |

| 6 marital status dummy variables s | MarSta1 (Base) | Married/living with partner |

| MarSta2 | Never married (single) | |

| MarSta3 | Divorced/widowed | |

| MarSta4 | Living with parents | |

| MarSta5 | Domestic partner/living with other adults | |

| MarSta6 | NA | |

| 4 terminal age of education dummy variables | Edu1 (Base) | 16 years or younger |

| Educ2 | 17–19 years | |

| Edu3 | 20 years or older | |

| Edu4 | Still studying | |

| 8 social class dummy variables | SClass1 (Base) | Semi or unskilled manual worker |

| SClass2 | Skilled manual worker | |

| SClass3 | Supervisory or clerical/Junior managerial/Professional/Administrator | |

| SClass4 | Intermediate managerial/Professional/Administrative | |

| SClass5 | Higher managerial/Professional/Administrative | |

| SClass6 | Student | |

| SClass7 | Retired and living on state pension only | |

| SClass8 | Unemployed (for over 6 months) or not working due to long term sickness | |

| 9 employment status dummy variables | Employ1 (Base) | Employed full time (30+ h per week) |

| Employ2 | Employed part time (less than 30 h per week) | |

| Employ3 | Self-employed | |

| Employ4 | Retired/Unable to work/Disabled | |

| Employ5 | Still at school | |

| Employ6 | In full time higher education | |

| Employ7 | Unemployed and seeking work | |

| Employ8 | Not working and not seeking work | |

| Employ9 | Prefer not to say | |

| 3 dummy variables regarding the participation in 2019 May EU elections | VoteEU1 (Base) | Voted |

| VoteEU2 | Did not vote | |

| VoteEU3 | Don’t know/Not applicable | |

| 5 dummy variables regarding national government support in general | Gov_Sup1 (Base) | Totally support |

| Gov_Sup2 | Tend to support | |

| Gov_Sup3 | Tend to oppose | |

| Gov_Sup4 | Totally oppose | |

| Gov_Sup5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | |

| 7 dummy variables regarding the personal position between the health benefits and economic damage | HBvsED1 (Base) | 1—The health benefits are greater than the economic damage |

| HBvsED2 | 2 | |

| HBvsED3 | 3 | |

| HBvsED4 | 4 | |

| HBvsED5 | 5 | |

| HBvsED6 | 6—The economic damage is greater than the health benefits | |

| HBvsED7 | Don’t know/Not applicable | |

| 7 dummy variables regarding the personal position on the recent limitations to my individual freedoms | LimIndFree1 (Base) | 1 The fight against the coronavirus pandemic fully justifies recent limitations to my individual freedoms |

| LimIndFree2 | 2 | |

| LimIndFree3 | 3 | |

| LimIndFree4 | 4 | |

| LimIndFree5 | 5 | |

| LimIndFree6 | 6 I am strongly opposed to any limitations of my individual freedoms, regardless of the coronavirus pandemic | |

| LimIndFree7 | Don’t know/Not applicable | |

| 5 dummy variables regarding the personal position on the use of apps to fight the virus’ expansion | AppsUse1 (Base) | Strongly in favor |

| AppsUse2 | Somewhat in favor | |

| AppsUse3 | Somewhat opposed | |

| AppsUse4 | Strongly opposed | |

| AppsUse5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | |

| 5 dummy variables regarding the own health concern because of the coronavirus | Health1 (Base) | Very concerned |

| Health2 | Fairly concerned | |

| Health3 | Not very concerned | |

| Health4 | Not at all concerned | |

| Health5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | |

| 5 dummy variables regarding the health concern of family and friends because of the coronavirus | Health_Fam1 (Base) | Very concerned |

| Health_Fam2 | Fairly concerned | |

| Health_Fam3 | Not very concerned | |

| Health_Fam4 | Not at all concerned | |

| Health_Fam5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | |

| 1 dummy variable that reflects whether the respondent is suffering some economic loss | Eco_loss | Loss of income, difficulties in paying bills/rents, partial unemployment or bankruptcy, difficulties in having decent meals |

| 5 dummy variables regarding if respondents receive help from people around them | Helped1 (Base) | Yes, definitely |

| Helped2 | Yes, somewhat | |

| Helped3 | No, not really | |

| Helped4 | No, not at all | |

| Helped5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | |

| 5 dummy variables regarding if respondents help other people in need | Helping1 (Base) | Yes, definitely |

| Helping2 | Yes, somewhat | |

| Helping3 | No, not really | |

| Helping4 | No, not at all | |

| Helping5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | |

| 5 dummy variables regarding if respondents talk more often to people on phone, social media or apps | Talk1 (Base) | Yes, definitely |

| Talk2 | Yes, somewhat | |

| Talk3 | No, not really | |

| Talk4 | No, not at all | |

| Talk5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | |

| 5 dummy variables regarding if respondents engage online in debates on the measures applied against the coronavirus | Debates1 (Base) | Yes, definitely |

| Debates2 | Yes, somewhat | |

| Debates3 | No, not really | |

| Debates4 | No, not at all | |

| Debates5 | Don’t know/Not applicable |

Table A3.

Homoscedastic model.

Table A3.

Homoscedastic model.

| Variable | Definition | Model | Marginal Effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Freq = 1 | Freq = 2 | Freq = 3 | Freq = 4 | Freq = 5 | ||

| Country1 | France | 0.1944 *** | −0.0131 *** | −0.0507 *** | −0.0045 *** | 0.0398 *** | 0.0284 *** |

| Country2 | Germany | 0.6924 *** | −0.0465 *** | −0.1804 *** | −0.0160 *** | 0.1419 *** | 0.1010 *** |

| Country4 | Italy | 0.4348 *** | −0.0292 *** | −0.1133 *** | −0.0100 *** | 0.0891 *** | 0.0634 *** |

| Country5 | Netherlands | 1.0710 *** | −0.0720 *** | −0.2790 *** | −0.0247 *** | 0.2195 *** | 0.1562 *** |

| Country6 | Belgium | 0.6585 *** | −0.0443 *** | −0.1715 *** | −0.0152 *** | 0.1349 *** | 0.0960 *** |

| Country7 | Austria | 1.2256 *** | −0.0824 *** | −0.3193 *** | −0.0283 *** | 0.2511 *** | 0.1788 *** |

| Country8 | Poland | 0.8204 *** | −0.0551 *** | −0.2137 *** | −0.0189 *** | 0.1681 *** | 0.1197 *** |

| Country9 | Sweden | 0.8714 *** | −0.0586 *** | −0.2270 *** | −0.0201 *** | 0.1786 *** | 0.1271 *** |

| Country10 | Finland | 0.9733 *** | −0.0654 *** | −0.2536 *** | −0.0224 *** | 0.1995 *** | 0.1420 *** |

| Country11 | Denmark | 1.4701 *** | −0.0988 *** | −0.3829 *** | −0.0339 *** | 0.3012 *** | 0.2144 *** |

| Country12 | Bulgaria | 0.8171 *** | −0.0549 *** | −0.2128 *** | −0.0188 *** | 0.1674 *** | 0.1192 *** |

| Country13 | Croatia | 1.3922 *** | −0.0936 *** | −0.3627 *** | −0.0321 *** | 0.2853 *** | 0.2031 *** |

| Country14 | Czech | 0.9449 *** | −0.0635 *** | −0.2461 *** | −0.0218 *** | 0.1936 *** | 0.1378 *** |

| Country15 | Greece | 1.3751 *** | −0.0924 *** | −0.3582 *** | −0.0317 *** | 0.2818 *** | 0.2006 *** |

| Country16 | Hungary | 0.6345 *** | −0.0426 *** | −0.1653 *** | −0.0146 *** | 0.1300 *** | 0.0925 *** |

| Country17 | Ireland | 1.3954 *** | −0.0938 *** | −0.3635 *** | −0.0322 *** | 0.2859 *** | 0.2035 *** |

| Country18 | Portugal | 1.1157 *** | −0.0750 *** | −0.2906 *** | −0.0257 *** | 0.2286 *** | 0.1627 *** |

| Country19 | Romania | 0.4425 *** | −0.0297 *** | −0.1153 *** | −0.0102 *** | 0.0907 *** | 0.0645 *** |

| Country20 | Slovakia | 1.0446 *** | −0.0702 *** | −0.2721 *** | −0.0241 *** | 0.2140 *** | 0.1523 *** |

| Country21 | Slovenia | 1.0792 *** | −0.0725 *** | −0.2811 *** | −0.0249 *** | 0.2211 *** | 0.1574 *** |

| Gender2 | Female | 0.0598 *** | −0.0040 *** | −0.0156 *** | −0.0014 *** | 0.0123 *** | 0.0087 *** |

| Gender 3 | I don’t identify as either | 0.2088 | −0.0140 | −0.0544 | −0.0048 | 0.0428 | 0.0305 |

| Gender4 | Prefer not to answer | 0.2439 | −0.0164 | −0.0635 | −0.0056 | 0.0500 | 0.0356 |

| HHsize 2 | 2 | −0.0510. | 0.0034. | 0.0133. | 0.0012. | −0.0105. | −0.0074. |

| HHsize 3 | 3 | −0.0668 * | 0.0045 * | 0.0174 * | 0.0015 * | −0.0137 * | −0.0097 * |

| HHsize 4 | 4 or more | −0.0525. | 0.0035. | 0.0137. | 0.0012. | −0.0108. | −0.0077. |

| Ch_Presence(N) | There are no children in the household | −0.0131 | 0.0009 | 0.0034 | 0.0003 | −0.0027 | −0.0019 |

| MarSta2 | Never married (single) | −0.0153 | 0.0010 | 0.0040 | 0.0004 | −0.0031 | −0.0022 |

| MarSta3 | Divorced/widowed | −0.0465 | 0.0031 | 0.0121 | 0.0011 | −0.0095 | −0.0068 |

| MarSta4 | Living with parents | 0.0218 | −0.0015 | −0.0057 | −0.0005 | 0.0045 | 0.0032 |

| MarSta5 | Domestic partner/living with other adults | −0.0187 | 0.0013 | 0.0049 | 0.0004 | −0.0038 | −0.0027 |

| MarSta6 | NA | −0.1327 * | 0.0089 * | 0.0346 * | 0.0031 * | −0.0272 * | −0.0194 * |

| Educ2 | 17−19 years | 0.0019 | −0.0001 | −0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0004 | 0.0003 |

| Edu3 | 20 years or older | 0.0179 | −0.0012 | −0.0047 | −0.0004 | 0.0037 | 0.0026 |

| Edu4 | Still studying | −0.0126 | 0.0008 | 0.0033 | 0.0003 | −0.0026 | −0.0018 |

| SClass2 | Skilled manual worker | −0.0384 | 0.0026 | 0.0100 | 0.0009 | −0.0079 | −0.0056 |

| SClass3 | Supervisory or clerical/Junior managerial/Professional/administrator | −0.0361 | 0.0024 | 0.0094 | 0.0008 | −0.0074 | −0.0053 |

| SClass4 | Intermediate managerial/Professional/Administrative | −0.0294 | 0.0020 | 0.0077 | 0.0007 | −0.0060 | −0.0043 |

| SClass5 | Higher managerial/Professional/Administrative | −0.0237 | 0.0016 | 0.0062 | 0.0005 | −0.0048 | −0.0035 |

| SClass6 | Student | −0.0072 | 0.0005 | 0.0019 | 0.0002 | −0.0015 | −0.0011 |

| SClass7 | Retired and living on state pension only | −0.1244 ** | 0.0084 * | 0.0324 ** | 0.0029 * | −0.0255 * | −0.0181 ** |

| SClass8 | Unemployed (for over 6 months) or not working due to long term sickness | −0.0258 | 0.0017 | 0.0067 | 0.0006 | −0.0053 | −0.0038 |

| Employ2 | Employed part time (less than 30 h per week) | −0.0358 | 0.0024 | 0.0093 | 0.0008 | −0.0073 | −0.0052 |

| Employ3 | Self-employed | −0.0621. | 0.0042. | 0.0162. | 0.0014. | −0.0127. | −0.0091. |

| Employ4 | Retired/Unable to work/Disabled | −0.0079 | 0.0005 | 0.0021 | 0.0002 | −0.0016 | −0.0012 |

| Employ5 | Still at school | 0.0079 | −0.0005 | −0.0021 | −0.0002 | 0.0016 | 0.0012 |

| Employ6 | In full time higher education | 0.0182 | −0.0012 | −0.0047 | −0.0004 | 0.0037 | 0.0027 |

| Employ7 | Unemployed and seeking work | −0.0555. | 0.0037. | 0.0145. | 0.0013. | −0.0114. | −0.0081. |

| Employ8 | Not working and not seeking work | −0.0404 | 0.0027 | 0.0105 | 0.0009 | −0.0083 | −0.0059 |

| Employ9 | Prefer not to say | −0.0617 | 0.0041 | 0.0161 | 0.0014 | −0.0126 | −0.0090 |

| VoteEU2 | Did not vote | −0.0675 *** | 0.0045 *** | 0.0176 *** | 0.0016 *** | −0.0138 *** | −0.0098 *** |

| VoteEU3 | Don’t know/Not applicable | −0.0586. | 0.0039. | 0.0153. | 0.0014. | −0.0120. | −0.0085. |

| Gov_Sup2 | Tend to support | −1.2181 *** | 0.0819 *** | 0.3173 *** | 0.0281 *** | −0.2496 *** | −0.1777 *** |

| Gov_Sup3 | Tend to oppose | −2.2106 *** | 0.1486 *** | 0.5759 *** | 0.0510 *** | −0.4530 *** | −0.3224 *** |

| Gov_Sup4 | Totally oppose | −3.1360 *** | 0.2108 *** | 0.8169 *** | 0.0723 *** | −0.6426 *** | −0.4574 *** |

| Gov_Sup5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | −1.7409 *** | 0.1170 *** | 0.4535 *** | 0.0401 *** | −0.3567 *** | −0.2539 *** |

| HBvsED2 | 2 | 0.0379 | −0.0025 | −0.0099 | −0.0009 | 0.0078 | 0.0055 |

| HBvsED3 | 3 | −0.0519 | 0.0035 | 0.0135 | 0.0012 | −0.0106 | −0.0076 |

| HBvsED4 | 4 | −0.0889 ** | 0.0060 ** | 0.0231 ** | 0.0020 ** | −0.0182 ** | −0.0130 ** |

| HBvsED5 | 5 | −0.2542 *** | 0.0171 *** | 0.0662 *** | 0.0059 *** | −0.0521 *** | −0.0371 *** |

| HBvsED6 | 6—The economic damage is greater than the health benefits | −0.5678 *** | 0.0382 *** | 0.1479 *** | 0.0131 *** | −0.1163 *** | −0.0828 *** |

| HBvsED7 | Don’t know/Not applicable | −0.0894 * | 0.0060 * | 0.0233 * | 0.0021 * | −0.0183 * | −0.0130 * |

| LimIndFree2 | 2 | −0.1320 *** | 0.0089 *** | 0.0344 *** | 0.0030 *** | −0.0271 *** | −0.0193 *** |

| LimIndFree3 | 3 | −0.2857 *** | 0.0192 *** | 0.0744 *** | 0.0066 *** | −0.0585 *** | −0.0417 *** |

| LimIndFree4 | 4 | −0.3933 *** | 0.0264 *** | 0.1025 *** | 0.0091 *** | −0.0806 *** | −0.0574 *** |

| LimIndFree5 | 5 | −0.4292 *** | 0.0288 *** | 0.1118 *** | 0.0099 *** | −0.0880 *** | −0.0626 *** |

| LimIndFree6 | 6—I am strongly opposed to any limitations of my individual freedoms, regardless of the coronavirus pandemic | −0.7536 *** | 0.0506 *** | 0.1963 *** | 0.0174 *** | −0.1544 *** | −0.1099 *** |

| LimIndFree7 | Don’t know/Not applicable | −0.3498 *** | 0.0235 *** | 0.0911 *** | 0.0081 *** | −0.0717 *** | −0.0510 *** |

| AppsUse2 | Somewhat in favor | −0.1449 *** | 0.0097 *** | 0.0377 *** | 0.0033 *** | −0.0297 *** | −0.0211 *** |

| AppsUse3 | Somewhat opposed | −0.2794 *** | 0.0188 *** | 0.0728 *** | 0.0064 *** | −0.0573 *** | −0.0408 *** |

| AppsUse4 | Strongly opposed | −0.4534 *** | 0.0305 *** | 0.1181 *** | 0.0105 *** | −0.0929 *** | −0.0661 *** |

| AppsUse5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | −0.2645 *** | 0.0178 *** | 0.0689 *** | 0.0061 *** | −0.0542 *** | −0.0386 *** |

| Health2 | Fairly concerned | 0.0795 ** | −0.0053 ** | −0.0207 ** | −0.0018 ** | 0.0163 ** | 0.0116 ** |

| Health3 | Not very concerned | 0.1654 *** | −0.0111 *** | −0.0431 *** | −0.0038 *** | 0.0339 *** | 0.0241 *** |

| Health4 | Not at all concerned | 0.1248 *** | −0.0084 ** | −0.0325 *** | −0.0029 ** | 0.0256 ** | 0.0182 ** |

| Health5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | 0.0555 | −0.0037 | −0.0145 | −0.0013 | 0.0114 | 0.0081 |

| Health_Fam2 | Fairly concerned | 0.0329 | −0.0022 | −0.0086 | −0.0008 | 0.0067 | 0.0048 |

| Health_Fam3 | Not very concerned | 0.0101 | −0.0007 | −0.0026 | −0.0002 | 0.0021 | 0.0015 |

| Health_Fam4 | Not at all concerned | −0.0141 | 0.0009 | 0.0037 | 0.0003 | −0.0029 | −0.0021 |

| Health_Fam5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | 0.1089 | −0.0073 | −0.0284 | −0.0025 | 0.0223 | 0.0159 |

| Eco_loss | Loss of income, difficulties in paying bills/rents, partial unemployment or bankruptcy, difficulties in having decent meals | −0.1122 *** | 0.0075 *** | 0.0292 *** | 0.0026 *** | −0.0230 *** | −0.0164 *** |

| Helped2 | Yes, somewhat | −0.1414 *** | 0.0095 *** | 0.0368 *** | 0.0033 *** | −0.0290 *** | −0.0206 *** |

| Helped3 | No, not really | −0.1840 *** | 0.0124 *** | 0.0479 *** | 0.0042 *** | −0.0377 *** | −0.0268 *** |

| Helped4 | No, not at all | −0.2136 *** | 0.0144 *** | 0.0556 *** | 0.0049 *** | −0.0438 *** | −0.0312 *** |

| Helped5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | −0.1533 ** | 0.0103 ** | 0.0399 ** | 0.0035 ** | −0.0314 ** | −0.0224 ** |

| Helping2 | Yes, somewhat | 0.0169 | −0.0011 | −0.0044 | −0.0004 | 0.0035 | 0.0025 |

| Helping3 | No, not really | −0.0042 | 0.0003 | 0.0011 | 0.0001 | −0.0009 | −0.0006 |

| Helping4 | No, not at all | 0.0157 | −0.0011 | −0.0041 | −0.0004 | 0.0032 | 0.0023 |

| Helping5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | −0.0950 * | 0.0064 * | 0.0247 * | 0.0022 * | −0.0195 * | −0.0139 * |

| Talk2 | Yes, somewhat | −0.0401 * | 0.0027 * | 0.0104 * | 0.0009. | −0.0082 * | −0.0058 * |

| Talk3 | No, not really | −0.0164 | 0.0011 | 0.0043 | 0.0004 | −0.0034 | −0.0024 |

| Talk4 | No, not at all | −0.0070 | 0.0005 | 0.0018 | 0.0002 | −0.0014 | −0.0010 |

| Talk5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | −0.0516 | 0.0035 | 0.0135 | 0.0012 | −0.0106 | −0.0075 |

| Debates2 | Yes, somewhat | −0.0835. | 0.0056. | 0.0218. | 0.0019. | −0.0171. | −0.0122. |

| Debates3 | No, not really | −0.0926 * | 0.0062 * | 0.0241 * | 0.0021 * | −0.0190 * | −0.0135 * |

| Debates4 | No, not at all | 0.0016 | −0.0001 | −0.0004 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 | 0.0002 |

| Debates5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | −0.0316 | 0.0021 | 0.0082 | 0.0007 | −0.0065 | −0.0046 |

| Threshold parameters | |||||||

| −3.4185 *** | |||||||

| −2.1584 *** | |||||||

| −2.0386 *** | |||||||

| −0.1126 | |||||||

| Model adjustment Log-Likelihood: −21,401.82 McFadden’s R2: 0.2738 AIC: 43,005.65 | |||||||

Significant codes: ‘***’ 0.001, ‘**’ 0.01, ‘*’ 0.05, ‘.’ 0.1.

Table A4.

Heteroskedastic model.

Table A4.

Heteroskedastic model.

| Variable | Definition | Model | Marginal Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SD | Freq = 1 | Freq = 2 | Freq = 3 | Freq = 4 | Freq = 5 | ||

| Country1 | France | 0.1015 *** | 0.0382 | −0.0088 | −0.0535 *** | −0.0060 *** | 0.0191 | 0.0493 *** |

| Country2 | Germany | 0.3154 *** | 0.0608 | −0.0237 *** | −0.1478 *** | −0.0179 *** | 0.0155 | 0.1740 *** |

| Country4 | Italy | 0.1969 *** | 0.0174 | −0.0193 *** | −0.1047 *** | −0.0112 *** | 0.0431 * | 0.0921 *** |

| Country5 | Netherlands | 0.5062 *** | 0.1711 *** | −0.0264 *** | −0.1898 *** | −0.0260 *** | −0.0825 *** | 0.3247 *** |

| Country6 | Belgium | 0.3065 *** | 0.1347 ** | −0.0183 *** | −0.1319 *** | −0.0173 *** | −0.0164 | 0.1838 *** |

| Country7 | Austria | 0.5464 *** | 0.0703 | −0.0311 *** | −0.2152 *** | −0.0290 *** | −0.0701 *** | 0.3454 *** |

| Country8 | Poland | 0.3700 *** | −0.0306 | −0.0296 *** | −0.1836 *** | −0.0219 *** | 0.0421 * | 0.1930 *** |

| Country9 | Sweden | 0.4130 *** | 0.2552 *** | −0.0160 *** | −0.1496 *** | −0.0217 *** | −0.0855 *** | 0.2727 *** |

| Country10 | Finland | 0.4443 *** | 0.0842. | −0.0280 *** | −0.1869 *** | −0.0243 *** | −0.0295 | 0.2686 *** |

| Country11 | Denmark | 0.6662 *** | 0.1335 ** | −0.0320 *** | −0.2300 *** | −0.0323 *** | −0.1473 *** | 0.4416 *** |

| Country12 | Bulgaria | 0.3628 *** | 0.0916 * | −0.0243 *** | −0.1595 *** | −0.0202 *** | −0.0081 | 0.2121 *** |

| Country13 | Croatia | 0.6151 *** | 0.1561 *** | −0.0303 *** | −0.2173 *** | −0.0303 *** | −0.1255 *** | 0.4034 *** |

| Country14 | Czech | 0.4294 *** | 0.1183 ** | −0.0258 *** | −0.1764 *** | −0.0232 *** | −0.0378 * | 0.2633 *** |

| Country15 | Greece | 0.6259 *** | 0.1305 ** | −0.0313 *** | −0.2233 *** | −0.0311 *** | −0.1248 *** | 0.4105 *** |

| Country16 | Hungary | 0.2873 *** | 0.0459 | −0.0231 *** | −0.1394 *** | −0.0165 *** | 0.0263 | 0.1526 *** |

| Country17 | Ireland | 0.6267 *** | 0.1247 ** | −0.0314 *** | −0.2238 *** | −0.0312 *** | −0.1250 *** | 0.4114 *** |

| Country18 | Portugal | 0.5070 *** | 0.0266 | −0.0313 *** | −0.2125 *** | −0.0280 *** | −0.0378 * | 0.3096 *** |

| Country19 | Romania | 0.2020 *** | 0.1389 ** | −0.0090. | −0.0887 *** | −0.0123 *** | −0.0137 | 0.1238 *** |

| Country20 | Slovakia | 0.4637 *** | 0.0479 | −0.0298 *** | −0.1982 *** | −0.0257 *** | −0.0244 | 0.2781 *** |

| Country21 | Slovenia | 0.4795 *** | −0.0494 | −0.0324 *** | −0.2174 *** | −0.0281 *** | 0.0009 | 0.2770 *** |

| Gender2 | Female | 0.0256 *** | −0.0268. | −0.0072 *** | −0.0172 *** | −0.0004 | 0.0217 *** | 0.0032 |

| Gender 3 | I don’t identify as either | 0.0550 | 0.0245 | −0.0047 | −0.0296 | −0.0033 | 0.0113 | 0.0263 |

| Gender4 | Prefer not to answer | 0.0791 | −0.0582 | −0.0152 | −0.0541 | −0.0032 | 0.0551 | 0.0174 |

| HHsize 2 | 2 | −0.0233. | 0.0219 | 0.0065. | 0.0153 * | 0.0004 | −0.0189. | −0.0033 |

| HHsize 3 | 3 | −0.0267 * | 0.0297 | 0.0082 * | 0.0176 * | 0.0003 | −0.0233 * | −0.0028 |

| HHsize 4 | 4 or more | −0.0255. | 0.0145 | 0.0058 | 0.0162 * | 0.0008 | −0.0171 | −0.0056 |

| Ch_Presence(N) | There are no children in the household | −0.0037 | −0.0400 * | −0.0046. | −0.0005 | 0.0013. | 0.0137. | −0.0099. |

| MarSta2 | Never married (single) | −0.0045 | 0.0202 | 0.0033 | 0.0040 | −0.0004 | −0.0097 | 0.0027 |

| MarSta3 | Divorced/Widowed | −0.0130 | −0.0010 | 0.0019 | 0.0078 | 0.0006 | −0.0056 | −0.0046 |

| MarSta4 | Living with parents | −0.0001 | 0.0089 | 0.0012 | 0.0007 | −0.0003 | −0.0034 | 0.0019 |

| MarSta5 | Domestic partner/living with other adults | −0.0035 | 0.0579. | 0.0084 | 0.0054 | −0.0015 | −0.0236. | 0.0113 |

| MarSta6 | NA | −0.0508 * | −0.0020 | 0.0082 | 0.0307 * | 0.0023 | −0.0244 | −0.0167 |

| Educ2 | 17–19 years | 0.0021 | −0.0953 * | −0.0118 * | −0.0088 | 0.0026. | 0.0373 * | −0.0192. |

| Edu3 | 20 years or older | 0.0081 | −0.1002 ** | −0.0141 * | −0.0116 | 0.0025. | 0.0418 * | −0.0186. |

| Edu4 | Still studying | −0.0029 | −0.0805. | −0.0090 | −0.0049 | 0.0025 | 0.0290 | −0.0176 |

| SClass2 | Skilled manual worker | −0.0188 | −0.0576 * | −0.0044 | 0.0073 | 0.0026 * | 0.0127 | −0.0183 ** |

| SClass3 | Supervisory or clerical/Junior managerial/Professional/administrator | −0.0137 | −0.1045 *** | −0.0106 ** | 0.0002 | 0.0037 *** | 0.0327 ** | −0.0261 *** |

| SClass4 | Intermediate managerial/Professional/Administrative | −0.0151 | −0.1177 *** | −0.0117 *** | −0.0002 | 0.0042 *** | 0.0366 ** | −0.0289 *** |

| SClass5 | Higher managerial/Professional/Administrative | −0.0080 | −0.0419 | −0.0040 | 0.0017 | 0.0016 | 0.0121 | −0.0114 |

| SClass6 | Student | 0.0001 | −0.0049 | −0.0006 | −0.0004 | 0.0001 | 0.0019 | −0.0010 |

| SClass7 | Retired and living on state pension only | −0.0590 ** | −0.1861 *** | −0.0126 ** | 0.0250 | 0.0093 *** | 0.0291 | −0.0507 *** |

| SClass8 | Unemployed (for over 6 months) or not working due to long term sickness | −0.0195 | −0.1116 ** | −0.0101 * | 0.0031 | 0.0044 * | 0.0310. | −0.0284 ** |

| Employ2 | Employed part time (less than 30 h per week) | −0.0059 | 0.0497 * | 0.0076. | 0.0064 | −0.0012 | −0.0215 * | 0.0087 |

| Employ3 | Self−employed | −0.0242 | 0.0669 * | 0.0135 ** | 0.0171 * | −0.0010 | −0.0357 ** | 0.0061 |

| Employ4 | Retired/Unable to work/Disabled | −0.0062 | 0.0388 | 0.0062 | 0.0059 | −0.0009 | −0.0175 | 0.0062 |

| Employ5 | Still at school | 0.0228 | 0.1223 ** | 0.0135. | −0.0059 | −0.0043 ** | −0.0392 * | 0.0359 ** |

| Employ6 | In full time higher education | 0.0087 | 0.0270 | 0.0022 | −0.0033 | −0.0012 | −0.0067 | 0.0089 |

| Employ7 | Unemployed and seeking work | −0.0120 | −0.0292 | −0.0019 | 0.0052 | 0.0014 | 0.0054 | −0.0101 |

| Employ8 | Not working and not seeking work | −0.0119 | 0.0742 * | 0.0124. | 0.0105 | −0.0017 | −0.0332 * | 0.0120 |

| Employ9 | Prefer not to say | −0.0135 | 0.0797 | 0.0136 | 0.0115 | −0.0018 | −0.0359. | 0.0126 |

| VoteEU2 | Did not vote | −0.0259 ** | 0.0262. | 0.0074 ** | 0.0171 *** | 0.0004 | −0.0217 ** | −0.0033 |

| VoteEU3 | Don’t know/Not applicable | −0.0200 | 0.0232 | 0.0063 | 0.0132. | 0.0002 | −0.0178 | −0.0019 |

| Gov_Sup2 | Tend to support | −0.6094 *** | −0.3391 *** | 0.0738 *** | 0.3639 *** | 0.0282 *** | −0.2265 *** | −0.2395 *** |

| Gov_Sup3 | Tend to oppose | −1.0407 *** | −0.2594 *** | 0.4469 *** | 0.3366 *** | −0.0096 *** | −0.5637 *** | −0.2102 *** |

| Gov_Sup4 | Totally oppose | −1.5004 *** | −0.0318 | 0.8510 *** | −0.0204. | −0.0277 *** | −0.6370 *** | −0.1660 *** |

| Gov_Sup5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | −0.8368 *** | −0.3363 *** | 0.3637 *** | 0.3403 *** | −0.0157 *** | −0.5609 *** | −0.1273 *** |

| HBvsED2 | 2 | 0.0028 | −0.0593 * | −0.0076 * | −0.0064 | 0.0016 | 0.0239 * | −0.0115 |

| HBvsED3 | 3 | −0.0398 ** | −0.1082 *** | −0.0073 * | 0.0171. | 0.0053 *** | 0.0194 | −0.0345 *** |

| HBvsED4 | 4 | −0.0591 *** | −0.0725 * | −0.0001 | 0.0323 ** | 0.0051 *** | −0.0038 | −0.0334 *** |

| HBvsED5 | 5 | −0.1369 *** | −0.0242 | 0.0213 *** | 0.0835 *** | 0.0064 *** | −0.0660 *** | −0.0451 *** |

| HBvsED6 | 6—The economic damage is greater than the health benefits | −0.3028 *** | 0.0864 * | 0.0962 *** | 0.1573 *** | 0.0034 * | −0.1978 *** | −0.0590 *** |

| HBvsED7 | Don’t know/Not applicable | −0.0523 ** | −0.1370 *** | −0.0086. | 0.0241. | 0.0071 *** | 0.0192 | −0.0418 *** |

| LimIndFree2 | 2 | −0.0635 *** | −0.1098 *** | −0.0041 | 0.0325 *** | 0.0065 *** | 0.0075 | −0.0423 *** |

| LimIndFree3 | 3 | −0.1324 *** | −0.1188 *** | 0.0062 | 0.0806 *** | 0.0100 *** | −0.0368 *** | −0.0600 *** |

| LimIndFree4 | 4 | −0.1793 *** | −0.0857 ** | 0.0210 *** | 0.1131 *** | 0.0101 *** | −0.0802 *** | −0.0640 *** |

| LimIndFree5 | 5 | −0.1911 *** | −0.0510. | 0.0306 *** | 0.1199 *** | 0.0087 *** | −0.0999 *** | −0.0593 *** |

| LimIndFree6 | 6—I am strongly opposed to any limitations of my individual freedoms, regardless of the coronavirus pandemic | −0.3821 *** | 0.0262 | 0.1192 *** | 0.2024 *** | 0.0044 * | −0.2508 *** | −0.0752 *** |

| LimIndFree7 | Don’t know/Not applicable | −0.1706 *** | −0.1135 ** | 0.0158 * | 0.1120 *** | 0.0109 *** | −0.0771 *** | −0.0617 *** |

| AppsUse2 | Somewhat in favour | −0.0630 *** | −0.0595 ** | 0.0021 | 0.0346 *** | 0.0048 *** | −0.0083 | −0.0331 *** |

| AppsUse3 | Somewhat opposed | −0.1223 *** | −0.0769 ** | 0.0101 * | 0.0736 *** | 0.0079 *** | −0.0402 *** | −0.0515 *** |

| AppsUse4 | Strongly opposed | −0.1914 *** | −0.0161 | 0.0335 *** | 0.1160 *** | 0.0079 *** | −0.0983 *** | −0.0592 *** |

| AppsUse5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | −0.1130 *** | −0.1307 *** | 0.0014 | 0.0684 *** | 0.0098 *** | −0.0241. | −0.0555 *** |

| Health2 | Fairly concerned | 0.0392 ** | −0.0687 ** | −0.0139 *** | −0.0292 *** | 0.0000 | 0.0441 *** | −0.0009 |

| Health3 | Not very concerned | 0.0723 *** | −0.0969 *** | −0.0214 *** | −0.0521 *** | −0.0011 | 0.0697 *** | 0.0049 |

| Health4 | Not at all concerned | 0.0619 *** | −0.0399 | −0.0128 *** | −0.0408 *** | −0.0022. | 0.0419 ** | 0.0139 |

| Health5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | 0.0384 | 0.0280 | −0.0021 | −0.0200 | −0.0026 | 0.0043 | 0.0203 |

| Health_Fam2 | Fairly concerned | 0.0076 | −0.0605 ** | −0.0087 ** | −0.0090 | 0.0014. | 0.0266 ** | −0.0102. |

| Health_Fam3 | Not very concerned | 0.0018 | −0.0550 * | −0.0070 * | −0.0054 | 0.0015 | 0.0218. | −0.0109 |

| Health_Fam4 | Not at all concerned | −0.0064 | 0.0345 | 0.0056 | 0.0059 | −0.0007 | −0.0159 | 0.0052 |

| Health_Fam5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | 0.0102 | −0.0942 | −0.0117. | −0.0154 | 0.0021 | 0.0410 | −0.0159 |

| Eco_loss | Loss of income, difficulties in paying bills/rents, partial unemployment or bankruptcy, difficulties in having decent meals | −0.0469 *** | 0.0478 ** | 0.0127 *** | 0.0318 *** | 0.0010 | −0.0393 *** | −0.0062 |

| Helped2 | Yes, somewhat | −0.0553 ** | −0.0650. | 0.0002 | 0.0301 ** | 0.0046 ** | −0.0039 | −0.0311 *** |

| Helped3 | No, not really | −0.0746 *** | −0.0781 * | 0.0015 | 0.0410 *** | 0.0059 *** | −0.0082 | −0.0402 *** |

| Helped4 | No, not at all | −0.0903 *** | −0.0743 * | 0.0044 | 0.0507 *** | 0.0065 *** | −0.0167 | −0.0448 *** |

| Helped5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | −0.0575 * | −0.1011 * | −0.0038 | 0.0304. | 0.0061 ** | 0.0044 | −0.0371 *** |

| Helping2 | Yes, somewhat | −0.0012 | −0.0537 * | −0.0065. | −0.0033 | 0.0016 | 0.0199. | −0.0117 |

| Helping3 | No, not really | −0.0084 | −0.0569 * | −0.0058. | 0.0009 | 0.0020 * | 0.0177 | −0.0148 * |

| Helping4 | No, not at all | 0.0029 | −0.0023 | −0.0007 | −0.0019 | −0.0001 | 0.0022 | 0.0005 |

| Helping5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | −0.0324 | −0.0489 | −0.0012 | 0.0169 | 0.0031. | 0.0017 | −0.0204. |

| Talk2 | Yes, somewhat | −0.0221 * | −0.0393 * | −0.0017 | 0.0105. | 0.0022 ** | 0.0048 | −0.0159 ** |

| Talk3 | No, not really | −0.0137 | −0.0185 | −0.0003 | 0.0070 | 0.0012 | 0.0006 | −0.0085 |

| Talk4 | No, not at all | −0.0108 | 0.0780 ** | 0.0126 * | 0.0103 | −0.0018. | −0.0342 ** | 0.0132 |

| Talk5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | −0.0283 | 0.0294 | 0.0087 | 0.0182 | 0.0003 | −0.0240 | −0.0033 |

| Debates2 | Yes, somewhat | −0.0342 | −0.1173 ** | −0.0090 | 0.0127 | 0.0053 * | 0.0252 | −0.0342 ** |

| Debates3 | No, not really | −0.0383 | −0.1494 *** | −0.0125 * | 0.0125 | 0.0064 ** | 0.0365. | −0.0429 *** |

| Debates4 | No, not at all | 0.0047 | −0.1347 ** | −0.0177 ** | −0.0125 | 0.0036 * | 0.0535 ** | −0.0269 * |

| Debates5 | Don’t know/Not applicable | −0.0208 | −0.1049 * | −0.0092 | 0.0046 | 0.0042. | 0.0279 | −0.0275 * |

| Threshold parameters | ||||||||

| −1.5923 *** | ||||||||

| −1.0112 *** | ||||||||

| −0.9594 *** | ||||||||

| −0.1308 ** | ||||||||

| Model Adjustment: Log-Likelihood: −20,866.18 No. Iterations: 26 McFadden’s R2: 0.2920604 AIC: 42,128.36 | ||||||||

Significant codes: ‘***’ 0.001, ‘**’ 0.01, ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1.

References

- Acemoglu, Daron, and James A. Robinson. 2001. A theory of political transitions. American Economic Review 91: 938–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achen, Christopher H., and Larry M. Bartels. 2017. Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government. Princeton: Princeton University Press, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Amat, Francesc, Andreu Arenas, Albert Falcó-Gimeno, and Jordi Muñoz. 2020. Pandemics Meet Democracy: Experimental Evidence from the COVID-19 Crisis in Spain. Working Paper, Preprint. Available online: https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/dkusw/ (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Andersen, Martin. 2020. Early Evidence on Social Distancing in Response to COVID-19 in the United States. SSRN 3569368. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3569368 (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Andersson, Staffan, and Nicholas Aylott. 2020. Sweden and Coronavirus: Unexceptional Exceptionalism. Social Sciences 9: 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, Linda. 2012. Organizational Learning: Creating, Retaining and Transferring Knowledge. Berlin: Springer Science and Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, Scott, Ethan Bueno de Mesquita, and Amanda Friedenberg. 2018. Learning about voter rationality. American Journal of Political Science 62: 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, Timothy. 2007. Principled Agents?: The Political Economy of Good Government. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bol, Damien, Marco Giani, André Blais, and Peter John Loewen. 2020. The effect of COVID-19 lockdowns on political support: Some good news for democracy? European Journal of Political Research. forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, Martin J. 2020. Italy’s ‘Darkest Hour’: How Coronavirus Became a Very Political Problem. Available online: https://theconversation.com/italys-darkest-hour-how-coronavirus-became-a-very-political-problem-133178 (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Celi, Giuseppe, Dario Guarascio, and Annamaria Simonazzi. 2020. A fragile and divided European Union meets Covid-19: Further disintegration or ‘Hamiltonian moment’? Journal of Industrial and Business Economics 47: 411–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CGTN. 2020. COVID-19 Timeline Betrays European Countries’ Different Responses. Available online: https://newseu.cgtn.com/news/2020-03-24/COVID-19-timeline-betrays-European-countries-different-responses-P4x9fbgzYs/index.html (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Cole, Shawn, Andrew Healy, and Eric Werker. 2012. Do voters demand responsive governments? Evidence from Indian disaster relief. Journal of Development Economics 97: 167–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, Daniel, Jennifer Gaskell, Will Jennings, and Gerry Stoker. 2020. Trust and the Coronavirus Pandemic: What are the Consequences of and for Trust? An Early Review of the Literature. Political Studies Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2020. Questions and Answers on the Agreement on the €1.8 Trillion Package to Help Build Greener, More Digital and More Resilient Europe. Brussels: European Commission, November 11. [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer, Thiemo, Lukas Hensel, Johannes Hermle, and Christopher Roth. 2020. Coronavirus perceptions and economic anxiety. Review of Economics and Statistics, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Alejandro Quiroz, and Alastair Smith. 2013. Leader survival and natural disasters. British Journal of Political Science 43: 821–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, Jorge. 2018. Natural disasters and clientelism: The case of floods and landslides in Colombia. Electoral Studies 55: 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, William H., and David A. Hensher. 2010. Modeling Ordered Choices: A Primer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, Guy, Soojong Kim, Jonah M. Rexer, and Harsha Thirumurthy. 2020. Political Partisanship Influences Behavioral Responses to Governors? Recommendations for COVID-19 Prevention in the United States. SSRN Working Paper. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_d=3578695 (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Harell, Allison. 2020. How Canada’s Pandemic Is Shifting Political Views. Report for the Institute for Research on Public Policy. Available online: https://policyoptions.irpp.org/fr/magazines/avril-2020/how-canadas-pandemic-response-is-shifting-political-views/ (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Hetherington, Marc J., and Michael Nelson. 2003. Anatomy of a rally effect: George W. Bush and the war on terrorism. PS: Political Science and Politics 36: 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessop, Bob. 2019. The Capitalist State and State Power. In The Oxford Handbook of Karl Marx. Edited by Vidal Matt, Tony Smith, Tomás Rotta and Paul Prew. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 299–320. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Gabriel, and Ines Levin. 2016. The dynamics of political support in emerging democracies: Evidence from a natural disaster in Peru. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 28: 173–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushner Gadarian, Shana, Sara Wallace Goodman, and Thomas B. Pepinsky. 2020. Partisanship, Health Behavior, and Policy Attitudes in the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic. SSRN Working Paper. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3574605 (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Legido-Quigley, Helena, José Tomás Mateos-García, Vanesa Regulez Campos, Montserrat Gea-Sánchez, Carles Muntaner, and Martin McKee. 2020. The resilience of the Spanish health system against the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Public Health 5: 251–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]