The Contribution of Socio-Demographic Factors to Walking Behavior Considering Destination Types; Case Study: Temuco, Chile

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

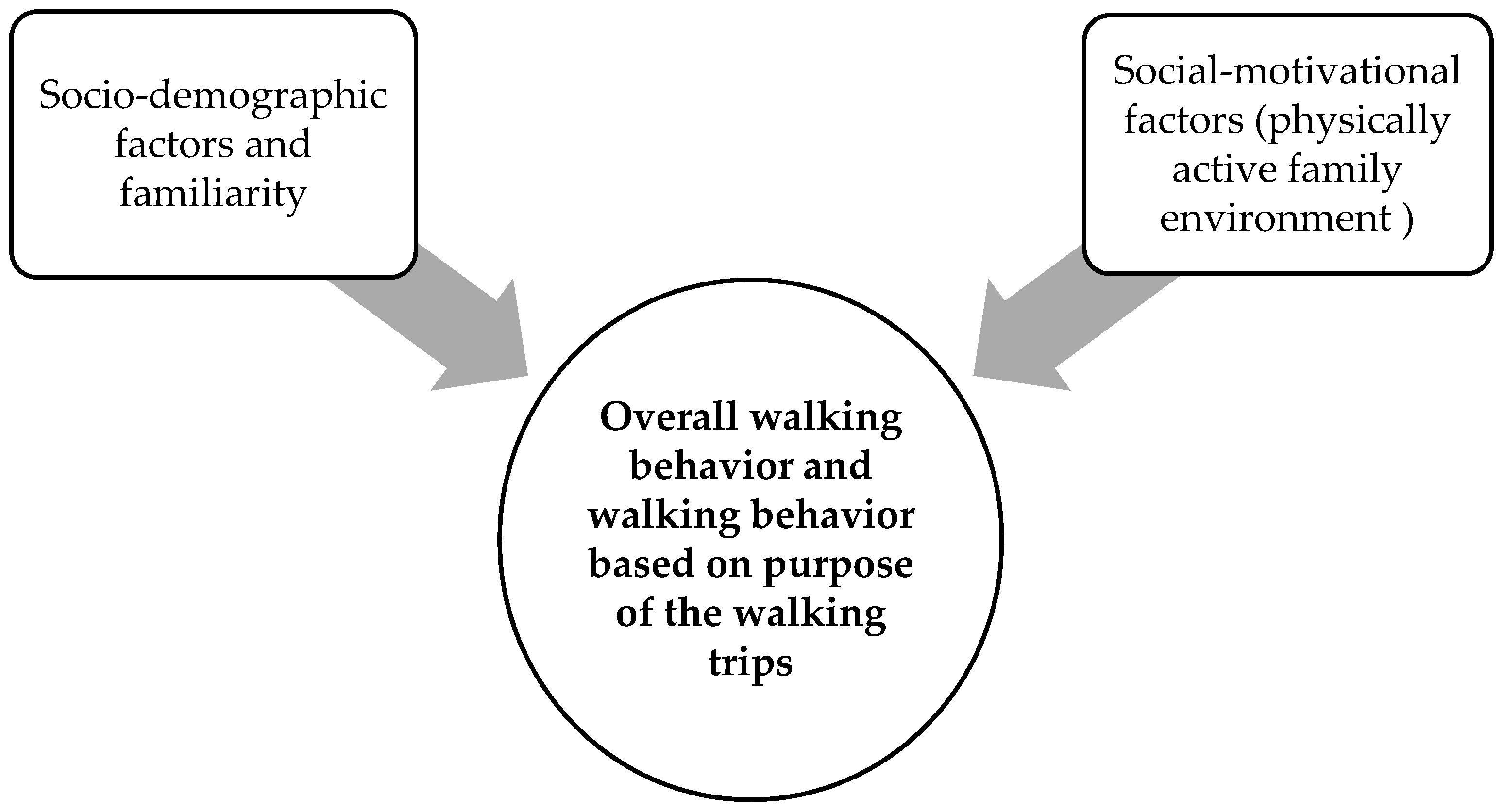

- What socio-demographic factors contribute to walking behavior in this city?

- (2)

- Does a physically active family environment contribute to walking behavior in Temuco?

- (3)

- How does the purpose of the walking trips influence the association between walking behavior and socio-demographic factors as well as physically active family environment?

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. The Factors Influencing Walking Behavior (Overall Walking)

4.3. The Factors That Impact on Walking Behavior Considering Three Types of Destination

5. Discussion

6. Limitations of the Study

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Actualizacion Plan De Transporte Temuco Y Desarrollo De Anteproyecto, ETAPA II. 2017. Ministerio de Transportes y Telecomunicaciones. Chile: SECTRA. [Google Scholar]

- Bagley, Michael N., and Patricia L. Mokhtarian. 2002. The Impact of Residential Neighborhood Type on Travel Behavior: A Structural Equations Modeling Approach. Annals of Regional Science 36: 279–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berger, Geoff Der, Nanette Mutrie, and Mary Hannah. 2005. The impact of retirement on physical activity. Aging Ment Health 25: 181–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bicalho, Paula Gonçalves, Tatiane Géa-Horta, Alexandra Dias Moreira, Andrea Gazzinelli, and Gustavo Velasquez-Melendez. 2018. Association between sociodemographic and health factors and the practice of walking in a rural area. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 23: 1323–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Booth, Katie M., Megan M. Pinkston, and Walker S. Carlos Poston. 2005. Obesity and the built environment. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 105: 110–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carrapatoso, Susana, Paula Silva, Paulo Colaço, and Joana Carvalho. 2017. Perceptions of the Neighborhood Environment Associated With Walking at Recommended Intensity and Volume Levels in Recreational Senior Walkers. Journal of Housing For the Elderly 32: 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celis-Morales, Carlos, Carlos Salas, Anas Alduhishy, Ruth Sanzana, María Adela Martínez, Ana Leiva, Ximena Diaz, Cristian Martínez, Cristian Álvarez, Jaime Leppe, and et al. 2015. Socio-demographic patterns of physical activity and sedentary behaviour in Chile: Results from the National Health Survey 2009–10. Journal of Public Health 38: e98–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clark, Andrew F., and Darren M. Scott. 2013. Does the social environment influence active travel? An investigation of walking in Hamilton, Canada. Journal of Transport Geography 31: 278–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Andrew F., Darren M. Scott, and Niko Yiannakoulias. 2014. Examining the relationship between active travel, weather, and the built environment: A multilevel approach using a GPS-enhanced dataset. Transportation 41: 325–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clark, Charlotte, and David Uzzell. 2002. The affordances of the home, neighbourhood, school and town centre for adolescents. Journal of Environmental Psychology 22: 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, Verity, Kylie Ball, Clare Hume, Anna Timperio, Abby C. King, and David Crawford. 2010. Individual, social and environmental correlates of physical activity among women living in socioeconmically disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Social Science and Medicine 70: 2011–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copperman, Rachel, and Chandra Bhat. 2007. An analysis of the determinants of children’s weekend physical activity participation. Transportation 34: 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, Cora L., Ross C. Brownson, Sue E Cragg, and Andrea L. Dunn. 2002. Exploring the effect of the environment on physical activity: A study examining walking to work. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 23: 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darlow, Susan D., and Xiaomeng Xu. 2011. The influence of close others’ exercise habits and perceived social support on exercise. Psychology of Sport & Exercise 12: 545–78. [Google Scholar]

- DiPietro, Loretta, Yichen Jin, Sameera Talegawkar, and Charles E Matthews. 2018. The Joint Associations of Sedentary Time and Physical Activity With Mobility Disability in Older People: The NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. The Journals of Gerontology Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 73: 532–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, Charles, Melvyn Hillsdon, and Thorogood Thorogood. 2004. Environmental perceptions and walking in English adults. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 58: 924–28. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, Amy, Mira Katz, Catherine Heaney, Dustin Duncan, Janet Buckworth, Angela Odoms-Young, and Sharla Willis. 2009. Social support and companionship among active African American women. American Journal of Health Behavior 33: 673–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harms, Ilse Mariska, Joke H. van Dijken, Karel A. Brookhuis, and Dick de Waard. 2019. Walking Without Awareness. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harms, Lucas, Luca Bertolini, and Marco te Brömmelstroet. 2014. Spatial and social variations in cycling patterns in a mature cycling country exploring differences and trends. Journal of Transport & Health 1: 232–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herrmann-Lunecke, Marie Geraldine, Rodrigo Mora, and Lake Sagaris. 2020. Persistence of walking in Chile: Lessons for urban sustainability. Transport Reviews 40: 135–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Frank B., Tricia Y. Li, Graham A. Colditz, Walter C. Willett, and JoAnn E. Manson. 2003. Television Watching and Other Sedentary Behaviors in Relation to Risk of Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Women. JAMA 289: 1785–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inoue, Shigeru Yumiko Ohya, Yuko Odagiri, Tomoko Takamiya, Kaori Ishii, Makiko Kitabayashi, Kenichi Suijo, James Sallis, and Teruichi Shimomitsu. 2010. Association between Perceived Neighborhood Environment and Walking among Adults in 4 Cities in Japan. Journal of Epidemiology 20: 277–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kang, Bumjoon, Anne Moudon, Philip Hurvitz, and Brian E Saelens. 2017. Differences in behavior, time, location, and built environment between objectively measured utilitarian and recreational walking. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 57: 185–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotulla, Theresa, Jon Martin Denstadli, Are Oust, and Elisabeth Beusker. 2019. What Does It Take to Make the Compact City Liveable for Wider Groups? Identifying Key Neighbourhood and Dwelling Features. Sustainability 11: 3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krogstad, Julie Runde, Randi Hjorthol, and Aud Tennøy. 2015. Improving walking conditions for older adults. A three-step method investigation. European Journal of Ageing 12: 249–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lemieux, Mélanie, and Gaston Godin. 2009. How well do cognitive and environmental variables predict active commuting? The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 6: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matthews, Charles E. 2002. Use of self-report instruments to assess physical activity. In Physical Activity Assessments for Health-Related Research. Edited by Greg Welk. Champaign: Human Kinetics, pp. 107–23. [Google Scholar]

- Menai, Mehdi, Hélène Charreire, Thierry Feuillet, Paul Salze, Christiane Weber, Christophe Enaux, Valentina A. Andreeva, Serge Hercberg, Julie-Anne Nazare, Camille Perchoux, and et al. 2015. Walking and cycling for commuting, leisure and errands: Relations with individual characteristics and leisure-time physical activity in a cross-sectional survey (the ACTI-Cités project). International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 12: 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes de Leon, Carlos F., Kathleen A. Cagney, Julia L. Bienias, Lisa L. Barnes, Kimberly A. Skarupski, Paul A. Scherr, and Denis A. Evans. 2009. Neighborhood social cohesion and disorder in relation to walking in community-dwelling older adults: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Aging and Health 21: 155–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mesters, Ilse, Stefanie Wahl, and Hilde M Van Keulen. 2014. Socio-demographic, medical and social-cognitive correlates of physical activity behavior among older adults (45–70 years): A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 14: 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ministerio de Salud de Chile. 2018. Encuesta Nacional de Salud (ENS): Contenido Informativo Descargable [Chilean National Health Survey (ENS): Informational Content] [WWW Document]. Available online: http://epi.minsal.cl/encuesta-ens-descargable/ (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Olsen, Jonathan R., Richard Mitchell, Nanette Mutrie, Louise Foley, and David Ogilvie. 2017. Population levels of, and inequalities in, active travel: A national, cross-sectional study of adults in Scotland. Preventive Medicine Reports 8: 129–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ory, Marcia G., Samuel D. Towne, Jaewoong Won, Samuel N. Forjuoh, and Chanam Lee. 2016. Social and environmental predictors of walking among older adults. BMC Geriatrics 16: 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paydar, Mohammad, and Asal Kamani Fard. 2016. Perceived legibility in relation to path choice of commuters in central business district. URBAN DESIGN International 21: 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydar, Mohammad, and Asal Kamani Fard. 2021a. The Contribution of Mobile Apps to the Improvement of Walking/Cycling Behavior Considering the Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 13: 10580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydar, Mohammad, and Asal Kamani Fard. 2021b. The Hierarchy of Walking Needs and the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 7461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydar, Mohammad, and Asal Kamani Fard. 2021c. The impact of legibility and seating areas on social interaction in the neighbourhood park and plaza. Archnet-IJAR 15: 571–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydar, Mohammad, Asal Kamani Fard, and Marzieh Khaghani. 2020a. Pedestrian Walkways for Health in Shiraz, Iran, the Contribution of Attitudes, and Perceived Environmental Attributes. Sustainability 12: 7263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydar, Mohammad, Asal Kamani Fard, and Mohammad M. Khaghani. 2020b. Walking toward Metro Stations: The Contribution of Distance, Attitudes, and Perceived Built Environment. Sustainability 12: 10291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydar, Mohammad, Asal Kamani Fard, and Roya Etminani-Ghasrodashti. 2017. Perceived Security of Women in Relation To Their Path Choice toward Sustainable Neighbourhood in Santiago, Chile. Cities 60: 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perchoux, Camille, Ruben Brondeel, Rania Wasfi, Olivier Klein, Geoffrey Caruso, Julie Vallée, Sylvain Klein, Benoit Thierry, Martin Dijst, Basile Chaix, and et al. 2019. Walking, trip purpose, and exposure to multiple environments: A case study of older adults in Luxembourg. Journal of Transport & Health 13: 170–84. [Google Scholar]

- Plaut, Pnina O. 2005. Non-motorized commuting in the US. Transportation Research Part D 10: 347–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rind, Esther, Niamh Shortt, Richard Mitchell, Elizabeth Richardson, and Jamie Pearce. 2015. Are income-related differences in active travel associated with physical environmental characteristics? A multi-level ecological approach. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 12: 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stathi, Afroditi, Holly Gilbert, Kenneth Fox, Jo Coulson, Mark Davis, and Janice Thompson. 2012. Determinants of neighborhood activity of adults age 70 and over: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity 20: 148–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stevenson, Mark, Jason Thompson, Thiago de Sá, Reid Ewing, Dinesh Mohan, Rod McClure, Ian Roberts, Geetam Tiwari, Billie Giles-Corti, Xiaoduan Sun, and et al. 2016. Land use, transport, and population health: Estimating the health benefits of compact cities. Lancet 388: 2925–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, Fei, Ian J Norman, and Alison E While. 2013. Physical activity in older people: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 13: 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sun, Guibo, Nicolas Oreskovic, and Hui Lin. 2014. How do changes to the built environment influence walking behaviors? a longitudinal study within a university campus in Hong Kong. International Journal of Health Geographics 13: 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sun, Guibo, Ransford A. Acheampong, Hui Lin, and Vivian C. Pun. 2015. Understanding Walking Behavior among University Students Using Theory of Planned Behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12: 13794–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Troped, Philip Kosuke Tamura, Meghan McDonough, Heather Starnes, Peter James, Eran Ben-Joseph, Ellen Cromley, Robin Puett, Steven Melly, and Francine Laden. 2017. Direct and Indirect Associations Between the Built Environment and Leisure and Utilitarian Walking in Older Women. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 51: 282–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Cauwenberg, Jelle, Liesbeth De Donder, Peter Clarys, Ilse De Bourdeaudhuij, Tine Buffel, Nico De Witte, Sarah Dury, Dominique Verté, and Benedicte Deforche. 2014. Relationships between the perceived neighborhood social environment and walking for transportation among older adults. Social Science & Medicine 104: 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauwenberg, Jelle, Veerle Van Holle, Dorien Simons, Riet Deridder, Peter Clarys, Liesbet Goubert, Jack Nasar, Jo Salmon, Ilse De Bourdeaudhuij, and Benedicte Deforche. 2012. Environmental factors influencing older adults’ walking for transportation: A study using walk-along interviews. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 9: 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xiao, Longzhu, Linchuan Yang, Jixiang Liu, and Hongtai Yang. 2020. Built Environment Correlates of the Propensity of Walking and Cycling. Sustainability 12: 8752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Hae Young. 2019. Environmental Factors Associated with Older Adult’s Walking Behaviors: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies. Sustainability 11: 3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zandieh, Razieh, Johannes Flacke, Javier Martinez, Phil Jones, and Martin Van Maarseveen. 2017. Do Inequalities in Neighborhood Walkability Drive Disparities in Older Adults’ Outdoor Walking? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14: 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Variables | Description of Variable | Frequency | Percentage | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years old) | 41.02 | |||

| Gender | Male | 714 | 43.6 | |

| Female | 922 | 56.3 | ||

| Monthly income (Chilean Peso) | (Low) Less than 300 mil | 483 | 57.5 | |

| (Medium) 300–1200 mil | 318 | 37.9 | ||

| (Upper-Medium and Higher) 1200–1700 and More | 39 | 4.6 | ||

| Home Property | Owner | 1234 | 75.4 | |

| Rent | 386 | 23.6 | ||

| Education | Low (Primary school and Lower) | 663 | 40.5 | |

| Intermediate (High School and similar degrees) | 837 | 51.2 | ||

| High (University degrees, bachelor and higher) | 136 | 8.3 | ||

| Job Situación | With job (Full or part time) | 562 | 34.3 | |

| Occasionally working | 23 | 1.4 | ||

| Retired and no job (The family members who do not work) | 1042 | 63.7 | ||

| Access to Internet | No Internet | 756 | 46.2 | |

| Having Internet | 875 | 53.5 | ||

| Access to TV | No TV | 684 | 41.8 | |

| Having TV | 949 | 58 | ||

| Current Housing Type | Department | 160 | 9.7 | |

| Villa Houses | 1473 | 90 | ||

| Driver’s license | Have | 265 | 16.2 | |

| Do not have | 1367 | 83.5 | ||

| Time Living Years (Familiarity) | Up to one year | 101 | 6.2 | |

| 1–5 | 383 | 23.4 | ||

| 6–10 | 224 | 13.7 | ||

| 11–20 | 345 | 21.1 | ||

| More tan 20 years | 580 | 35.4 | ||

| Number of Vehicles at Home | Have | 541 | 33.1 | |

| Do not Have | 1095 | 66.9 | ||

| Number of Bicycles at Home | 1.07 | |||

| Number of People in Household | 4.12 | |||

| Number of Trips for each household | 11.95 | |||

| Walking trips based on purpose of walking | ||||

| To study | 509 | 29.6 | ||

| To Job | 317 | 18.4 | ||

| For shopping | 293 | 17 | ||

| See someone | 190 | 12.7 | ||

| To health center | 89 | 6.4 | ||

| For recreation | 78 | 4.9 | ||

| Otra cosa | 160 | 11 | ||

| Variables | Standard Coefficient | t | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic variables and Familiarity | |||

| Gender Dummy | 0.103 | 4.102 | 0.000 ** |

| Age (Continous) | 0.135 | 4.015 | 0.000 ** |

| Monthly income (“Upper medium and higher income” is reference category) | |||

| Dummy low income | 0.024 | 0.675 | 0.500 |

| Dummy medium income | −0.030 | −0.854 | 0.394 |

| Home property Dummy | −0.011 | −0.382 | 0.702 |

| Education (High education is reference category) | |||

| Dummy low education | −0.084 | −1.523 | 0.128 |

| Dummy intermediate education | −0.056 | −1.106 | 0.269 |

| Job Situación (“Retired and no job” is reference category) | |||

| Dummy with job | 0.092 | 2.811 | 0.005 ** |

| Dummy occasionally working | 0.039 | 1.564 | 0.118 |

| Access to internet (Dummy) | −0.016 | −0.585 | 0.559 |

| Access to TV (Dummy) | −0.042 | −1.581 | 0.104 |

| Dummy Housing Type | −0.046 | −1.781 | 0.075 * |

| Driver’s license (Dummy) | −0.057 | −1.965 | 0.050 * |

| Time Living Years (Familiarity) (More than 20 years is reference category) | |||

| Less than one year Dummy | 0.015 | 0.504 | 0.614 |

| 1–5 years Dummy | 0.014 | 0.467 | 0.641 |

| 6–10 years Dummy | 0.015 | 0.531 | 0.596 |

| 11–20 years Dummy | 0.046 | 1.638 | 0.102 |

| Having private car at home (Dummy) | −0.043 | −1.609 | 0.098 * |

| Number of Bicycles at Home (Continous) | 0.004 | −0.159 | 0.874 |

| Number of People in Household (Continous) | 0.122 | 3.623 | 0.000 ** |

| Number of Trips in household (Continous) | 0.003 | 0.094 | 0.925 |

| Social variables | |||

| Proportion of walking trips to total trips in each household | 0.176 | 6.313 | 0.000 ** |

| Standard Coefficient 1 | p-Value | Standard Coefficient 2 | p-Value | Standard Coefficient 3 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic variables | ||||||

| Gender (Dummy) | 0.057 | 0.372 | 0.093 | 0.035 ** | 0.141 | 0.023 ** |

| Age (Continous) | 0.119 | 0.116 | 0.143 | 0.057 * | 0.144 | 0.027 ** |

| Monthly income (“Upper medium and higher income” is reference category) | ||||||

| Dummy low income | −0.073 | 0.326 | 0.092 | 0.054 | 0.067 | 0.528 |

| Dummy medium income | −0.186 | 0.113 | 0.214 | 0.754 | 0.109 | 0.335 |

| Home property Dummy | −0.020 | 0.771 | −0.021 | 0.671 | 0.104 | 0.126 |

| Education (High education is reference category) | ||||||

| Dummy low education | −0.151 | 0.169 | −0.199 | 0.472 | −0.008 | 0.931 |

| Dummu intermediate education | −0.159 | 0.129 | −0.038 | 0.887 | −0.018 | 0.824 |

| Job Situación (“Retired and no job” is reference category) | ||||||

| Dummy with job | 0.173 | 0.011 ** | 0.032 | 0.478 | −0.066 | 0.326 |

| Dummy occasionally working | −0.044 | 0.463 | 0.036 | 0.434 | 0.033 | 0.599 |

| Access to internet (Dummy) | −0.113 | 0.122 | −0.058 | 0.263 | 0.046 | 0.490 |

| Access to TV (Dummy) | −0.051 | 0.446 | −0.011 | 0.819 | −0.110 | 0.071 * |

| Dummy Housing Type | 0.037 | 0.567 | −0.114 | 0.017 ** | −0.159 | 0.012 ** |

| Driver’s license (Dummy) | −0.002 | 0.976 | −0.177 | 0.000 ** | −0.137 | 0.052 * |

| Time Living Years (Familiarity) (More than 20 years is reference category) | ||||||

| Less than one year Dummy | −0.124 | 0.103 | 0.126 | 0.025 | 0.112 | 0.134 |

| 1–5 years Dummy | 0.029 | 0.653 | −0.021 | 0.722 | 0.083 | 0.236 |

| 6–10 years Dummy | −0.083 | 0.211 | 0.025 | 0.637 | 0.062 | 0.344 |

| 11–20 years Dummy | −0.068 | 0.278 | 0.073 | 0.184 | 0.124 | 0.050 ** |

| Having private car at home (Dummy) | 0.010 | 0.883 | −0.077 | 0.110 | 0.008 | 0.899 |

| Number of Bicycles at Home (Continous) | −0.037 | 0.573 | 0.043 | 0.357 | −0.064 | 0.312 |

| Number of People in Household (Continous) | 0.112 | 0.179 | 0.078 | 0.146 | 0.141 | 0.124 |

| Number of Trips in household (Continous) | 0.167 | 0.054 * | −0.003 | 0.959 | 0.028 | 0.746 |

| Social Variables | ||||||

| Proportion of walking trips to total trips in each household | 0.295 | 0.000 ** | 0.065 | 0.193 | 0.172 | 0.009 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paydar, M.; Fard, A.K. The Contribution of Socio-Demographic Factors to Walking Behavior Considering Destination Types; Case Study: Temuco, Chile. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120479

Paydar M, Fard AK. The Contribution of Socio-Demographic Factors to Walking Behavior Considering Destination Types; Case Study: Temuco, Chile. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(12):479. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120479

Chicago/Turabian StylePaydar, Mohammad, and Asal Kamani Fard. 2021. "The Contribution of Socio-Demographic Factors to Walking Behavior Considering Destination Types; Case Study: Temuco, Chile" Social Sciences 10, no. 12: 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120479

APA StylePaydar, M., & Fard, A. K. (2021). The Contribution of Socio-Demographic Factors to Walking Behavior Considering Destination Types; Case Study: Temuco, Chile. Social Sciences, 10(12), 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120479