The Dynamics of Remittances Impact: A Mixed-Method Approach to Understand Ghana’s Situation and the Way Forward

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Reflection

2.1. Justification of a Holistic Approach towards Migration

2.2. Empirical Works: The Role of Remittances and the Need for a New Direction towards Social Elements

3. Methodology

3.1. The Model

3.2. Data Source and Description

4. Results

4.1. Summary Statistics

4.2. Unit Root Test

4.3. Estimation Results

4.4. Micro-Analysis: The Inequality and Poverty Situation at the Household Level and How It Is Linked to Remittances

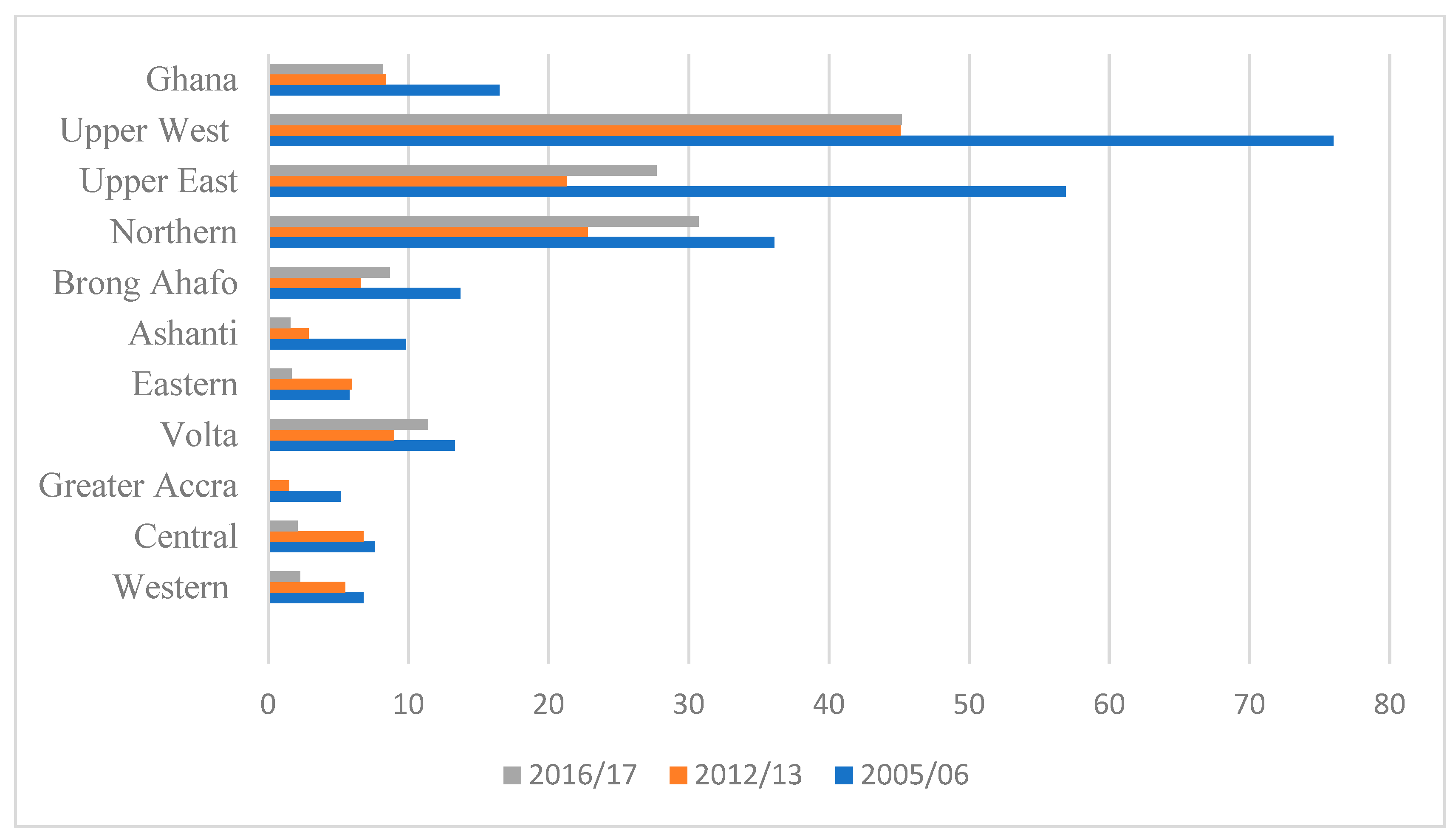

Remittances and Inequality in Ghana

4.5. Marxist Political Economy Perspective

4.5.1. Historicising the International Migration Situation in Ghana

4.5.2. Blending History and Marxist Political Economy on Migration

5. Discussion

Theoretical Implication and the Way Forward

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Unit Root Test Results Table (ADF) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Null Hypothesis: The Variable Has a Unit Root | ||||

| At Level | At First Difference | |||

| Intercept | Intercept + Trend | Intercept | Intercept + Trend | |

| LNREM | −3.4459 | −3.4183 | −7.0553 | −7.0962 |

| 0.0153 | 0.0639 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| ** | * | *** | *** | |

| LNODA | −1.1401 | −4.3468 | −7.7565 | −7.6316 |

| 0.6898 | 0.0072 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| n0 | *** | *** | *** | |

| LNGDP | 0.6088 | −2.6622 | −3.4663 | −3.7804 |

| 0.9881 | 0.2571 | 0.0147 | 0.0291 | |

| n0 | n0 | ** | ** | |

| LNCPID1 | −5.7106 | −7.2054 | −5.6214 | −5.4017 |

| 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0006 | |

| *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| LNGCF | −2.4488 | −1.1768 | −4.2162 | −4.6469 |

| 0.1364 | 0.8999 | 0.0022 | 0.0038 | |

| n0 | n0 | *** | *** | |

| Unit Root Test Results Table (PP) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Null Hypothesis: The Variable Has a Unit Root | ||||

| At Level | At first Difference | |||

| Intercept | Intercept + Trend | Intercept | Intercept + Trend | |

| LNREM | −3.4233 | −3.4183 | −9.0884 | −18.9150 |

| 0.0162 | 0.0639 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| ** | * | *** | *** | |

| LNODA | −1.2433 | −4.3556 | −9.2873 | −9.0123 |

| 0.6454 | 0.0071 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| n0 | *** | *** | *** | |

| LNGDP | 2.3286 | −3.2849 | −3.3088 | −3.5070 |

| 0.9999 | 0.0841 | 0.0216 | 0.0533 | |

| n0 | * | ** | * | |

| LNCPID1 | −5.7106 | −10.8523 | −33.4338 | −36.1001 |

| 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | |

| *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| LNGCF | −2.4534 | −1.2521 | −4.2396 | −4.5219 |

| 0.1353 | 0.8833 | 0.0021 | 0.0051 | |

| n0 | n0 | *** | *** | |

References

- Abdul-Mumuni, Abdallah, and Christopher Quaidoo. 2016. Effect of International Remittances on Inflation in Ghana Using the Bounds Testing Approach. Business and Economic Research 6: 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, Richard. 2011. Evaluating the Economic Impact of International Remittances On Developing Countries Using Household Surveys: A Literature Review. The Journal of Development Studies 47: 809–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, Richard, Jr., and Alfredo Cuecuecha. 2010. The Economic Impact of International Remittances on Poverty and Household Consumption and Investment in Indonesia. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5433. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Adepoju, Aderanti. 2005. Patterns of Migration in West Africa. In At Home in the World. International Migration and Development in Contemporary Ghana and West Africa. Edited by Takyiwaa Manuh. Accra: Sub-Saharan Publishers, pp. 24–54. [Google Scholar]

- Adepoju, Aderanti. 2010. International Migration within, to and from Africa in a Globalised World. Accra: Sub-Saharan Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, Reena, Demirgüç-Kunt Asli, Peria Maria, and Soledad Martinez. 2011. Do remittances promote financial development? Journal of Development Economics 96: 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anarfi, Kwasi John, and Ofosu-Mensah Ababio Emmanuel. 2018. A Historical Perspective of Migration from and to Ghana. In Migration in a Globalising World. Perspectives from Ghana. Edited by Awumbila Mariama. Accra: Sub-Saharan Publishers, pp. 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Anarfi, John, and Stephen Kwankye. 2005. The Costs and Benefits of Children’s Independent Migration From Northern to Southern Ghana. Paper presented at the International Conference on Childhoods: Children and Youth in Emerging and Transforming Societies, Oslo, Norway, June 29–July 3; Oslo: Migration, Globalisation & Poverty, pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Anarfi, Kwasi John, Kofi Awusabo-Asare, and Nicholas N. N. N. Nuamah. 2000. Push and Pull Factors of International Migration–Country Report: Ghana. Working Paper No. 2000/E(10). Luxembourg: Eurostat. [Google Scholar]

- Antwi Bosiakoh, Thomas. 2008. ‘Understanding Ghana’s Migrants: A Study of Nigerian Migrant Associations in Accra, Ghana. Master’s thesis, Sociology Department, University of Ghana, Legon, Accra, Ghana. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur, John. 2008. The Africa Diaspora in the United States and Europe. Minnesota: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Awumbila, Mariama. 1997. Gender and Structural Adjustment in Ghana: A Case Study in Northeast Ghana. In Tradition, Location and Community: Place-Making and Development. Edited by A. N. Teymur. New York: Awotoma, Avebury Aldershot, pp. 161–72. [Google Scholar]

- Awumbila, Mariama, Manuh Takyiwaa, Tagoe Quartey Peter, Addoquaye Cynthia, and Bosiako Antwi Thomas. 2008. Migration Country Paper: Ghana. Accra: Centre for Migration Studies, University of Ghana. [Google Scholar]

- Bade, Klaus. 2003. Migration in European History. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bank of Ghana. 2019. Annual Report 2019. Accra: Bank of Ghana. [Google Scholar]

- Barajas, Adolfo, Chami Ralph, Fullenkamp Connel, Gapen Michael, and Montiel Peter. 2010. Do Workers’ Remittances Promote Economic Growth? IMF Working Paper WP/09/153. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Barham, Bradford, and Stephen Boucher. 1998. Migration, remittances, and inequality: Estimating the net effects of migration on income distribution. Journal of Development Economics 55: 307–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmamoun, Mamoun, and Kevin Lehnert. 2013. Financial Growth: Comparing the effects of FDI, ODA, and International Remittances. Journal of Economic Development 38: 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boarini, Romina, Fabrice Murtin, and Paul Schreyer. 2015. Inclusive Growth: The OECD Measurement Framework. OECD Statistics Working Papers, 2015/06. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bump, Micah. 2006. Ghana: Searching for Opportunities at Home and Abroad. Georgetown: Institute for the Study of International Migration, Georgetown University. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, Fernando Henrique. 1972. Dependency and Development in Latin America. New Left Review 74: 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Castles, Stephen, and J. Mark Miller. 2009. The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo, Cristina. 2005. International Migration and Poverty; Cross-Country Analysis. Milan: Università Degli Studi di Milano. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, Murshed. 2016. Financial development, remittances and economic growth: Evidence using a dynamic panel estimation. The Journal of Applied Economic Research 10: 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jeffrey. H. 2005. Remittances outcomes and migration: Theoretical contests, real opportunities. Studies in Comparative. International Development 40: 88–112. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Jeffrey H, and Leila Rodriguez. 2005. Remittance Outcomes in Rural Oaxaca, Mexico: Challenges, Options and Opportunities for Migrant Households. Population, Space and Place 11: 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, John, and Denis Conway. 2000. Migration and remittances in Island microstates: A comparative perspective on the South Pacific and the Caribbean. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 24: 52–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haas, Hein. 2021. Theory of migration: The aspirations-capabilities framework. Comparative Migration Studies 9: 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado Wise, Raul, and Humberto Marquez. 2009. Understanding the Relationship Between Migration and Development: Toward a New Theoretical Approach. Social Analysis 53: 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado Wise, Raul, and Henry Veltmeyer. 2018. Rethinking Development from a Latin American Perspective. Canadian Journal of Development Studies 39: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dessy, Sylvain, and Tiana Rambeloma. 2009. Immigration Policy, Remittances, and Growth in the Migrant-Sending Countries. Working Paper 09–15. Quebec: CIRPEE. [Google Scholar]

- Durand, Jorge, Parrado Kandel William, and Douglas Massey. 1996. International migration and development in Mexican communities. Demography 33: 249–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehwi, Juvenile, Maslova Sabina Richmond, and Asante Lewis Abedi. 2021. Flipping the page: Exploring the connection between Ghanaian migrants’ remittances and their living conditions in the UK. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekbia, Hamid, and Bonnie Nardi. 2016. Social Inequality and HCI: The View from Political Economy. Problem-solving or not? The Boundaries of HCI Research, 4997–5002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Frank. 2000. Rural Livelihoods and Diversity in Developing Countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eromenko, Igor. 2016. Do Remittances Cause Dutch Disease in Resource-Poor Countries of Central Asia? MPRA Paper 74965. Munich: University Library of Munich. [Google Scholar]

- Faist, Thomas. 2019. Migration and the Politics in Social Inequality in the Twenty-First Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fayissa, Bichaka, and Christian Nsiah. 2010. The Impact of Remittances on Economic Growth and Development in Africa. The American Economist 52: 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghana Statistical Service. 2018. Poverty Trends in Ghana 2005–2017. Ghana Living Standards Survey. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service. [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Statistical Service. 2019. Ghana Living Standard Survey 7 Main Report. Household Survey. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service. [Google Scholar]

- González, Mercedes, Augustín Escobar, and Agustin Latapik. 1991. The Impact of IRCA on the migration Patterns of a Community in Los Altos, Jalisco, Mexico. In The Effect of ReceivingCountry Policies on Migration Flows. Edited by Diáz-Briquet. Boulder: Westvie, pp. 205–31. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Richard. 2007. Geographies of investment: How do the wealthy build new houses in Accra, Ghana? Urban Forum 18: 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiliano, Paola, and Marta Ruiz-Arranz. 2009. Remittances, financial development, and growth. Journal of Development Economics 90: 144–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupto, Sanjeev, Catherine Patillo, and Smita Wagh. 2009. Effect of Remittances on Poverty and Financial Development in sub-Saharan Africa. World Development 37: 104–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamood, Sara. 2006. African Transit Migration through Libya to Europe. The Human Cost. Cairo: American University of Cairo. [Google Scholar]

- International Organisation for Migration. 2019. Migration in Ghana, a Country Profile. Geneva: IOM. [Google Scholar]

- Iosifides, Theodoros. 2016. Qualitative Methods in Migration Studies; A Critical Realist Perspective. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, Zafar, and Sattar Abdus. 2005. The Contribution of Workers’ Remittances to Economic Growth in Pakistan. Research Report No: 187. Pakistan: PIDE. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R. 1998. Introduction: The renewed role of remittances in the New World Order. Economic Geography 74: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kabki, Mirjam. 2007. Transnationalism, Local Development and Social Security: The Functioning of Support Networks in Rural Ghana. Leiden: African Studies Center. [Google Scholar]

- Ketkar, Suhas, and Dilip Ratha. 2001. Securitisation of Future Flow Receivables: A Useful Tool for Developing Countries. Finance and Development. A Quarterly Magazine of the IMF 38(1). Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, James, and Richard Anker. 1981. Analysis of Income Transfers in a Developing Country: The Case of Kenya. Journal of Development Economics 8: 205–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, Michael. 1980. Migration from the rural areas of poor countries: The impact on rural productivity and income distribution. World Development 8: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokshin, Michael, Bontch-Osmolovski Mikhail, and Glinskaya Elena. 2010. Work-related migration and poverty reduction in Nepal. Review of Development Economics 14: 323–32. [Google Scholar]

- Martey, Edward, and Ralph Armah. 2020. Welfare effect of international migration on the left-behind in Ghana: Evidence from machine learning. Migration Studies 1: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, Douglas. 1990. Social Structure, Household Strategies, and the Cumulative Causation of Migration. Population Index 56: 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, Douglas, and Emilio Parrado. 1998. International migration and business formation in Mexico. Commentaries. Authors’ reply. Social Science Quarterly 79: 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, Douglas, Arango Joaquin, Hugo Graeme, Kouaouci Ali, Pellegrino Adela, and Taylor Edward. 1993. Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal. Population and Development Review 18: 229–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, Valentina, Bart Van Den Boom, and Nicholas Nsowah-Nuamah. 2008. Remittances in Ghana: Origin, Destination and Issues of Measurement. International Migration 46: 103–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, Esi Akyere. 2012. The Saga of the Returnee. Exploring the Implications of Involuntary Return Migration for Development. A Study of the Reintegration Process for Ghanaian Migrant Workers from Libya. Master’s thesis, Development Management, University of Agder, Kristiansand, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Mines, Richard. 1981. Developing a Community Tradition of Migration: A Field Study in Rural Zacatecas, Mexico, and California Settlement Areas. San Diego: Monographs in U.S.-Mexican Studies no.3. La Jolla: Center for U. S.-Mexican Studies, University of Califonia at San Diego. [Google Scholar]

- Mousourou, Loukia M. 1991. Migration and Migration Policy in Greece and Europe. Athens: Gutenberg. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Phuc Hien. 2017. Remittances and competitiveness: A case study of Vietnam. Journal of Economics, and Business Management 5: 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nishat, Muhammed, and Bilgrami Nighat. 1991. The impact of migrant worker’s remittances on Pakistan economy, Pakistan. Economic and Social Review 29: 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, Brian, Max Roser, and Stefan Thewissen. 2016. GDP Per Capita Versus Median Household Income: What Gives Rise to Divergence Over Time? LIS Working Paper Series, No. 672. Luxembourg: LIS Cross-National Data Center. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamongo, Esman, Misati Morekwa, Kipyegon Leonard Roseline, and Lydia Ndirangu. 2012. Remittances, financial development and economic growth in Africa. Journal of Economics and Business 64: 240–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberai, A. S., and Manmohan K. Singh. 1980. Migration, Remittances and Rural Development: Findings of a Case Study in the Indian Punjab. International Labor Review 119: 229–41. [Google Scholar]

- Owusu, Thomas. 2000. The Role of Ghanaian Immigrant Association in Toronto, Canada. International Migration Review 34: 1115–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peil, Margaret. 1974. Ghana’s Aliens. International Migration Review 8: 367–81. [Google Scholar]

- Peil, Margaret. 1995. Ghanaians Abroad. African Affairs 94: 336–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peprah, James Atta, Isaac Kwesi Ofori, and Abel Nyarko Asomani. 2019. Financial development, remittances and economic growth: A threshold analysis. Cogent Economics & Finance 7: 1625107. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, Alejandro, and Ruben Rumbaut. 2006. Immigrant America: A Portrait, 3rd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ratha, Dilip. 2003. Workers’ Remittances: An Important and Stable Source of External Development Finance. In Global Development Finance 2003. Washington, DC: World Bank, pp. 157–75. [Google Scholar]

- Reichert, Joshua. 1981. The migrant syndrome: Seasonal US labour migration and rural development in central Mexico. Human Organization 40: 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, Hymie. 1992. Migration, Development and Remittances in Rural Mexico. International Migration 30: 127–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, Sharon Stanton, and Michael Teitelbaum. 1992. International Migration and International Trade. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, Sharon Stanton, Jacobsen Karen, and William Deane Stanley. 1990. International Migration and Development in Sub-Sahara Africa. World Bank Discussion Papers 101. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Solimano, Andres. 2003. Workers Remittances to the Andean Region: Mechanisms, Costs, and Development Impact. Paper present at the Multilateral Investment Fund-IDB Conference, Quito, Ecuador, May 12. [Google Scholar]

- Spatafora, Nikola. 2005. Worker Remittances and Economic Development. In World Economic Outlook April 2005. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, Oded. 1984. Rural-to-Urban Migration in LDCs: A Relative Deprivation Approach. Economic Development and Cultural Change 32: 475–86. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, Oded. 1991. The Migration of Labor. Oxford and Cambridge: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, Oded, and David Bloom. 1985. The new economics of labour migration. The American Economic Review 75: 173–78. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, Oded, Edward Taylor, and Shlomo Yitzhaki. 1988. Migration, Remittances in Inequality: A Sensitivity Analysis Using the Extended Gini Index. Journal of Development Economics 28: 309–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigliz, Joseph E. 2012. Price of Inequality. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Stratan, Alexandru, Marcel Chistruga, Victoria Clipa, Alexandru Fala, and Viorica Septelici. 2013. Development and Side Effects of Remittances in the CIS Countries: The Case of the Republic of Moldova. San Domenico di Fiesole (FI): CARIM-East RR 2013/25. Fiesole: Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, European University Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, James, and Michael Kearney. 1984. Causes and Effects of Agricultural Labor Migration from the Mixteca of Oaxaca to California. La Jolla and San Diego: Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies, University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J. Edward, Jorge Mora, Richard Adams, and Alejandro Lopez-Feldman. 2005. Remittances, Inequality and Poverty. Evidence from Rural Mexico: Working Papers n° 05-003. San Diego: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Tonah, Steve, and Emmanuel Codjoe. 2020. Risking It All: Irregular Migration from Ghana through Libya to Europe and Its Impact on the Left-Behind Family Members. In Global Processes of Flight and Migration. The Explanatory Power of Case Studies. Edited by Eva Bahl. Göttingen: Göttingen University Press, pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Twumasi-Ankrah, K.waku. 1995. Rural-urban migration and socioeconomic development in Ghana: Some discussions.10(2). Journal of Social Development In Africa 9: 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). 2019. International Migrant Stock 2019. Data Set. New York: United Nations. Available online: www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates19.asp (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2009. Human Development Report 2009: Overcoming Barriers: Human Mobility and Development. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hear, Nicholas. 2009. Managing Mobility for Human Development: The Growing Salience of Mixed Migration. UNDP Human Development Research Paper, 2009/20. New York: UNDP Human Development. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, Lina. 2006. Europe and migrations in the 20th century. In Immigration and Immigrant Integration into Greek Society. Edited by Papadopoulou Eleni. Athens: Gutenberg, pp. 83–126. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2006. Global Economic Prospects 2006: Economic Implications of Remittances and Migration. Washington, DC: WorldBank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2020. World Bank Data. Retrieved from Personal Remittances Received (Current US$)-Ghana. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.CD.DT?locations=GH (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Yassen, S. Hadeel. 2012. The positive and negative impact of remittances on economic growth in MENA countries. Journal of International Management Studies 7: 7–14. [Google Scholar]

| GDP | GCF | CPI | ODA | REM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 6.931411 | 9.430690 | 2.383965 | −9.821681 | 4.084335 |

| Median | 6.846872 | 8.565914 | 2.825483 | −10.06363 | 4.107707 |

| Maximum | 7.499458 | 12.99713 | 5.541670 | −4.586451 | 6.275405 |

| Minimum | 6.541699- | 6.989855 | 2.805889 | −14.29474 | 2.398568 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.280299 | 1.829813 | 2.369218 | 2.662037 | 0.979850 |

| Probability | 0.128742 | 0.200034 | 0.233205 | 0.372845 | 0.464539 |

| Sum Sq. Dev. | 2.985556 | 117.1876 | 213.3014 | 269.2847 | 36.48405 |

| Observations (no. of years of the series) | 38 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 38 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 4.383537 | 0.388260 | 11.29019 | 0.0000 *** |

| LNREM | 0.038999 | 0.013999 | 2.785848 | 0.0090 *** |

| LNGCF | 0.078052 | 0.024679 | 3.162727 | 0.0035 *** |

| D(LNCPI) | −0.187033 | 0.088150 | −2.121762 | 0.0420 ** |

| LNODA | −0.168275 | 0.017704 | −9.505154 | 0.0000 *** |

| R-squared | 0.961155 | |||

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.956143 | |||

| Regions | Total Number of Households | No. of Households That Receive Remittances Overseas | Percentage of Households Remittances Received |

|---|---|---|---|

| Western | 753,642 | 4067 | 0.54% |

| Central | 607,837 | 1160 | 0.19% |

| Greater Accra | 1,324,504 | 32,158 | 2.43% |

| Volta | 547,455 | 4033 | 0.74% |

| Eastern | 857,405 | 8001 | 0.93% |

| Ashanti | 1,661,560 | 6569 | 0.40% |

| Brong Ahafo | 678,208 | 3707 | 0.55% |

| Northern | 479,675 | 1108 | 0.23% |

| Upper East | 226,983 | 625 | 0.28% |

| Upper West | 162,655 | 130 | 0.08% |

| Total | 7,299,925 | 61,558 | 0.84% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Asafo Agyei, S. The Dynamics of Remittances Impact: A Mixed-Method Approach to Understand Ghana’s Situation and the Way Forward. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10110410

Asafo Agyei S. The Dynamics of Remittances Impact: A Mixed-Method Approach to Understand Ghana’s Situation and the Way Forward. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(11):410. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10110410

Chicago/Turabian StyleAsafo Agyei, Stephen. 2021. "The Dynamics of Remittances Impact: A Mixed-Method Approach to Understand Ghana’s Situation and the Way Forward" Social Sciences 10, no. 11: 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10110410

APA StyleAsafo Agyei, S. (2021). The Dynamics of Remittances Impact: A Mixed-Method Approach to Understand Ghana’s Situation and the Way Forward. Social Sciences, 10(11), 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10110410