1. Introduction

Divorce is one of the most stressful life events, bringing several emotional, affective, and social consequences for the divorcing couple and their children (

Garrido-Rojas et al. 2021). Many studies have documented the short-term effects of parental divorce on children and adolescents, such as internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, lower academic achievement, poor physical health, higher risk for mental health, or attachment insecurity (

Afifi and McManus 2010;

Altenhofen et al. 2010;

Baert and Van der Straeten 2021;

Weaver and Schofield 2015). In the long term, a great body of research also suggests that parental divorce is associated with negative outcomes on adult children, such as lower educational and occupational attainment (

Larson and Halfon 2013), lower wellbeing (

Amato 2001;

Huurre et al. 2006), insecure attachment styles (

Fraley and Heffernan 2013), poor marital quality (

Amato 2001), higher divorce rates (

Amato 2001), mental and physical health problems (

Schaan et al. 2019;

Tullius et al. 2021), and less secure parent-child relationships (

Amato 2001;

Cui and Fincham 2010;

Feeney and Monin 2016). Nevertheless, in Spain the effects of parental divorce on children and adults have been less widely examined than in other countries (e.g.,

Cantón et al. 2002).

In Spain, divorce was legally recognized in 1981. Since then, divorce rates have increased dramatically, from 0.6 annual divorces per 1000 inhabitants in 1990 to 2.0 per 1000 inhabitants in 2018 (

Eurostat, Statistical Office of the European Communities 2020). According to the Spanish National Statistics Institute (

INE 2020), 56.7% of Spanish divorced families have underage children or economically dependent overage children. Parental divorce, therefore, might be a stressful life event for many Spanish young adults. Since the examination of the possible long-term effects of parental divorce on Spanish emerging adult children is limited, in this study, we attempted to fill this gap in the literature by analyzing the effects of parental divorce on parent-child relationships among emerging adults from a cultural context where divorce is still novel. Emerging adulthood has specific features that cannot be considered an extension of adolescence. Unlike emerging adults, adolescents still live with their parents, and they are minors under the law (

Arnett 2015). Additionally, during adolescence, parents play a crucial role as socializing agents (

Queiroz et al. 2020). Conversely, emerging adulthood is characterized by much more freedom from parental control, greater independent exploration, and greater emotional autonomy toward parents. In addition, parental socialization strategies during this developmental period are characterized by more warmth and less strictness (

García et al. 2020). Even if some scholars suggest that parental socialization is over when the adolescent reaches adult age (

Gimenez-Serrano et al. 2021;

García et al. 2020), parents are still important figures in the transition to this period, as young adults still depend on their parents not only as an economic resource but also for emotional support and advice (

Arnett 2015). Moreover, this developmental period provides an excellent opportunity for personal growth in several domains, such as education, employment, intimate relationships, and parenthood, but it is also a developmentally challenging transition to adulthood, in which relationships with parents are emotionally charged from positive emotions, such as love, gratitude, and acceptance to more negative emotions, such as resentment, disillusionment, and wariness (

Arnett 2015). Given that divorce is an emotionally stressful and complex transition for families and that emerging adulthood is a stage of crisis, in this study, we expected less positive parent-child relationships among Spanish emerging adults who have experienced parental divorce.

From the divorce–stress–adjustment perspective, divorce is considered a family transition event that brings some family readjustments to its members (

Amato 2010). Thus, from this perspective, it is not divorce per se that leads to negative consequences, but family life changes and stressful circumstances surrounding divorce that might increase the risk of a variety of problems among children. These circumstances refer to pre- and post-divorce conflict levels, poorer relationship quality with the custodial parent, lower frequency of contact with the non-custodial parent (

Bastaits et al. 2012;

Carlson 2006), lower economic resources, and other stressful events, such as changing residence, or parents remarrying (

Amato 1994). Moreover, this perspective highlights that divorce is a process in which several factors may moderate children’s reactions to divorce and that stressors related to this experience might mediate the association between parental divorce and children’s reactions to it, leading to negative consequences that can persist into adulthood. Specifically, stressful circumstances surrounding the divorce experience might diminish parents’ responsiveness and availability as primary caregivers (

Feeney and Monin 2016), which can lead children to suffer from a deterioration in parenting from both custodial and non-custodial parents (

Hetherington and Kelly 2002). Indeed, attachment theory suggests that early caregiving experiences influence social and close relationships throughout the life span (

Bowlby 1969). Furthermore, negative family experiences, such as divorce, can affect parents’ appraisals, emotions, and behaviors, leading them to be less sensitive to their children’s needs which in turn, may have a negative impact on the quality of parent-child relationships. In fact, some empirical studies have associated parental divorce with less secure parent-child relationships, even in the long term, during young adulthood (

Amato 2001;

Feeney and Monin 2016).

The quality of parent-child relationships has also been studied as a key mediator between parental divorce and children’s later adjustment, due to the modifications that parent-child relationships experience in the post-divorce period (

Amato 2000;

Amato and Sobolewski 2001;

Lee 2019). Adult children of divorce usually have less contact with their parents, exchange less emotional support and help behaviors with them, and describe the relationships with their parents in a more negative way which, in turn, has been associated with lower wellbeing levels in young adulthood (e.g.,

Amato and Sobolewski 2001). Furthermore, according to some longitudinal studies, stressful life events, such as parental divorce, might change parent-child attachment relationships, which, in turn, may influence adult children’s romantic attachment and romantic relationship quality (

Lee 2019;

Waters et al. 2000). A less positive involvement from parents following divorce might also reduce children’s social competence and may lead adult children to hold more negative expectations towards intimate relationships (

Bartell 2006;

Kelly and Emery 2003).

Although some studies have exclusively examined the impact of parental divorce on parent-child relationships (e.g.,

Booth and Amato 2001), little is known about the potential roles that the parent’s gender plays. That is, scarce studies have examined the differential effects of parental divorce on father-child and mother-child relationships (

Lee 2018,

2019;

Smith-Etxeberria and Eceiza 2021). A number of studies have suggested that divorce seems to affect more negatively adult children’s relationships with their father than with their mother (

Amato 2014;

Amato and Booth 1996;

King 2002). In the post-divorce period, children usually suffer from a loss of or diminished contact with their non-custodial parent, who is usually the father. That is, after parental divorce, non-custodial fathers are likely to have less contact with their children, and the frequency of contact declines over time (

Carlson 2006). This situation might lead children to have a negative view of their fathers and to a decrease in closeness in the relationship with their father (

Bartell 2006;

Kelly and Emery 2003;

Lee 2019). These changes in father-child relationships might also be associated with young adults’ lower wellbeing, more negative relationship attitudes, lower romantic relationship quality, and higher risk for psychopathology (

Bartell 2006;

Carr et al. 2018;

Kelly and Emery 2003;

Reuven-Krispin et al. 2021). In fact, both partial and complete father absence during the post-divorce period have been associated with lower wellbeing levels among young adults (

Reuven-Krispin et al. 2021).

Given the inconsistent results regarding the effects of parental divorce on father-child and mother-child relationships, more empirical research is needed to clarify this issue, especially in young adulthood, analyzing which variables associated with the quality of father-child and mother-child relationships are more affected. Some scholars (e.g.,

Armsden and Greenberg 1987) have defined the quality of parent-child affective relationships in terms of trust (i.e., parental understanding, respect and mutual trust), communication (i.e., extent and quality of verbal communication with parents), and alienation (i.e., feelings of alienation and loneliness in parent-child relationships). Thus, in the current study, we analyzed the association between parental divorce and trust, communication, and alienation in mother-child and father-child relationships during young adulthood.

In addition to parental divorce, continued exposure to parental conflict has also been associated with negative outcomes in both mother-child and father-child relationships during young adulthood (

Riggio 2004;

Riggio and Valenzuela 2011), such as lower affective quality, independence, and emotional support in both father-child and mother-child relationships (

Riggio 2004). The spillover hypothesis in the family systems theory suggests that negativity from disruption in one family subsystem (e.g., interparental conflict) might spill over into other subsystems (e.g., parent-child relationships), such that parents might reproduce marital hostility and aggressiveness in the relationships with their children (

Harold and Sellers 2018;

Sturge-Apple et al. 2006). Parental stress related to conflict might hinder parents’ ability to be sensitive and supportive attachment figures to their children. Moreover, parental conflict throughout early development might lead children to view themselves as unlovable and unworthy of love, while they might perceive others as undependable and uncaring and as a consequence, close interpersonal relationships as undependable and transitory (

Belsky et al. 1991;

Steinberg et al. 2006). Continued marital conflict, therefore, might also be associated with more negative parent-child interactions in childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood (

Martin et al. 2017;

Sturge-Apple et al. 2006). In this vein, the results of some studies have indicated that adult children who report high levels of interparental conflict show more insecure attachment relationships with both parents (

Hannum and Dvorak 2004;

Ross and Fuertes 2010). In addition, perceived frequency, intensity, and resolution of interparental conflict, along with both perceived threat and self-blame in the presence of interparental conflict, have been associated with lower trust and communication in parent-child relationships (

Ross and Fuertes 2010).

Empirical research has also shown that parent-child relationship quality mediates the association between parental conflict and adult children’s adjustment. Indeed, children exposed to parental conflict show feelings of keeping a less close relationship with both parents (

Booth and Amato 1994;

Sobolewski and Amato 2007) which in turn, has been linked with a greater risk of adult children suffering from distress, lower self-esteem, general unhappiness, and lower romantic relationship quality (

Booth and Amato 2001;

Cusimano and Riggs 2013). Likewise, children exposed to parental conflict show higher parent-child alienation (

Monè and Biringen 2006) and a higher likelihood of feeling caught between parents which in turn, leads to lower wellbeing of children (

Amato and Afifi 2006).

Some studies have also compared the effects of parental divorce with those of interparental conflict. Overall, both parental conflict and divorce are associated with more negative parent-child relationships (

Amato and Booth 1996;

Booth and Amato 1994). However,

Monè and Biringen (

2006), for example, found that interparental conflict is associated with greater alienation in parent-child relationships, regardless of parental divorce. Children whose parents have a highly conflicted marriage are more likely to feel caught in the middle between their parents than those from divorced families (

Amato and Afifi 2006). Other investigations, instead, have suggested differential effects of parental divorce and conflict for the quality of mother-child and father-child relationships. Specifically, when comparing the effects of parental divorce and interparental conflict, a few studies have concluded that parental divorce leads to more negative father-child relationships, whereas interparental conflict is linked with more negative mother-child and father-child relationships (

Hannum and Dvorak 2004;

Riggio 2004;

Riggio and Valenzuela 2011;

Smith-Etxeberria and Eceiza 2021). In order to shed further light on this issue, in this study, we also examined the association between parental divorce and conflict with young adult children’s trust, communication, and alienation in both father-child and mother-child affective relationships.

In the study of the effects of these family experiences, beyond comparing and analyzing the differential effects of parental divorce and conflict, it is necessary to analyze their interactive relationship. The stress-relief hypothesis (

Wheaton 1990) posits that divorce, as a stressful life experience, can benefit children if perceived as a way of escape from a stressful or dysfunctional environment. That is, parental divorce might alleviate the stress derived from high levels of interparental conflict, leading young adult children to fare better when the parental marital relationship is characterized by high levels of conflict in the pre-divorce period, whereas they fare worse when low parental conflict precedes divorce (

Booth and Amato 2001). Evidence suggests that parental divorce might have a buffering effect on the negative effects of conflictive interactions between parents on children and that high levels of parental conflict might lead to even more negative outcomes for children when parents do not divorce (

Gager et al. 2016). Some researchers have attempted to test this hypothesis by analyzing the interaction between parental divorce and conflict. Although several studies have failed to find an interactive effect on parent-child relationship quality (

Booth and Amato 2001;

Monè and Biringen 2006;

Riggio 2004;

Riggio and Valenzuela 2011), a recent study found such an interactive effect (

Yu et al. 2010), suggesting that divorce uniquely moderates the negative effects of interparental conflict on mother-daughter relationships. That is,

Yu et al. (

2010) found that interparental conflict in non-divorced families has a negative impact on mother-daughter relationships and that this effect is reduced when parents divorce, such that parental divorce seems to have a buffering effect on mother–daughter relationships when the parental marital relationship is characterized by high levels of conflict. However, these previous studies did not analyze the difference between destructive and constructive conflict behaviors. Destructive conflict behaviors are characterized by the cultivation of hostility in the relationship and a lack of resolution, whereas constructive behaviors are characterized by cooperation, resolution, problem solving, and support, which are associated with more positive outcomes in children (

Kopystynska et al. 2020;

McCoy et al. 2013). Therefore, in this study, in order to test the stress-relief hypothesis, we analyzed the interaction between parental divorce and low and high interparental conflict by distinguishing between that which was unresolved and resolved. The literature review suggests that the resolution of conflictive behaviors between parents plays a primary role in children’s adjustment. Furthermore, offspring who perceive a lack of resolution within their parental marital relationships show poor adjustment, whereas those who observe resolution strategies in their interparental disagreements are more likely to be better adjusted (

Cantón et al. 2013). Hence, in this study, we expected poorer parent-child relationships among emerging adult children who perceive frequent, intense, and non-resolved conflictive interactions between their parents. By contrast, we predict positive outcomes in parent-child relationships among those who perceive both frequent and intense but resolved interparental conflict, as well as low levels of frequency and intensity and high levels of resolution in their interparental interactions.

Overview of the Current Study

By investigating the role that parental divorce and interparental conflict play in young adult children’s affective relationships quality with their parents, we aimed to contribute to the literature in several ways. First, limited attention has been given to the study of the associations between parental divorce and conflict and their interactive effect on parent-child relationships. Moreover, the potential roles of parents’ gender have not been extensively investigated. Thus, in this study we attempted to contribute to the literature by analyzing these effects on both father-child and mother-child relationship quality, considering the different dimensions that define the quality of father-child and mother-child affective relationships, such as trust, communication, and alienation. Next, although the literature review suggests that constructive or resolved conflictive interactions between parents might lead to positive outcomes in children, this link has not been widely empirically examined. Finally, the study of these effects in Spanish emerging adults is limited. Herein, the following hypotheses were tested:

Parental divorce will be associated with lower trust and communication and higher alienation in mother-child and father-child relationships.

High unresolved interparental conflict will be associated with lower trust and communication and higher alienation in mother-child and father-child relationships.

High unresolved interparental conflict will be more strongly associated with lower trust and communication and higher alienation in mother-child and father-child relationship quality than parental divorce.

High resolved parental conflict will be associated with higher trust and communication and lower alienation in both father-child and mother-child affective relationships quality.

High interparental conflict and parental divorce will interact to explain both father-child and mother-child affective relationships, such that parental divorce will moderate the effects of high parental conflict. Specifically, for young adults from non-divorced families, high interparental conflict will be positively associated with lower trust and communication and higher alienation in mother-child and father-child relationship quality to a greater degree than for young adults whose parents divorced.

4. Discussion

The present study analyzed the associations between parental divorce and interparental conflict with trust, communication, and alienation in both mother-child and father-child relationship quality in a Spanish young adult sample. In addition, the interactive effect of parental divorce and conflict was also tested. This study makes important contributions in relation to other studies by (1) Analyzing a non-widely studied developmental period; (2) examining an understudied population of Spanish emerging adults; (3) studying simultaneously the associations between parental divorce and both high resolved and high unresolved interparental conflict with trust, communication, and alienation in mother-child and father-child relationships and (4) examining the interactive effect between parental divorce and both high resolved and high unresolved interparental conflict.

Parental divorce is a life event stressor that involves multiple changes and has significant consequences for children. Even though several studies have found stronger effects on children during the first years after parental divorce, some other studies have found long-term consequences on young adult children (e.g.,

Hetherington and Kelly 2002). In this investigation, as expected (hypothesis 1), our results suggested that adult children of divorce show lower relationship quality with both parents (

Amato 2001;

Sobolewski and Amato 2007). Specifically, parental divorce was associated with lower trust and communication, along with higher alienation, in both mother-child and father-child relationships. Stressors associated with the divorce process are usually accompanied by deterioration in the parenting of both custodial and non-custodial parents. Custodial parents (usually mothers) might be less sensitive to their children’s needs and non-custodial parents might diminish their parenting role during the divorce process and the post-divorce period (

Hetherington and Kelly 2002). All of these changes may negatively affect parent-child relationship quality, even in the long term, when children are young adults and are entering a new important developmental stage, as shown by our results. However, our findings suggest a stronger association between parental divorce and qualities related to father-child relationships, such as lower trust and communication. This result is consistent with several investigations that indicate that father-child relationships are more deteriorated than mother-child relationships by the divorce experience (

Lee 2019;

Riggio and Valenzuela 2011;

Smith-Etxeberria and Eceiza 2021). This might be due to the fact that the parenting of fathers is more likely to be negatively affected by circumstances surrounding the divorce experience (

Lee 2019), whereas mothers’ parenting roles do not seem to be so altered. Non-custodial fathers usually have little contact with their children, and this contact decreases over time. This has an impact on the quality of their involvement in their children’s lives, which, in turn, also affects negatively both children’s wellbeing and the quality of father-child relationships, even until adulthood (

Lee 2019;

Reuven-Krispin et al. 2021).

Another way through which parent-child relationships can be affected in adulthood is through continued exposure to high levels of conflictive interactions between parents. In fact, research on the associations between interparental conflict and parent-child relationship quality indicates negative and significant associations between high levels of parental conflict and both mother-child and father-child relationship quality (

Riggio 2004;

Smith-Etxeberria and Eceiza 2021). That is, continued exposure to parental conflict might hinder parents’ ability to function as a secure base and safe haven for their children, due to the stress related to conflictive interactions (

Martin et al. 2017). This lower sensitivity might also explain more negative parent-child interactions in young adulthood (

Davies and Cummings 2006). In our study, parental conflict is associated with more negative father-child and mother-child relationships in young adulthood. Overall, in support of our second hypothesis, our results suggest that interparental conflict is associated with lower trust and communication and higher alienation in the relationship quality with both parents. Furthermore, our findings support our predictions (hypothesis 3) about the greater predictive ability of parental conflict than parental divorce on parent-child relationships in young adulthood. However, this conclusion is especially meaningful for trust, communication, and alienation in mother-child relationships and for alienation in father-child relationships. That is, when both high resolved and high unresolved levels of interparental conflict were included, parental divorce was no longer associated with dimensions defining the quality of mother-child relationships (trust, communication, and alienation) and alienation in father-child relationships. Nevertheless, our results suggest that both parental divorce and conflict are concurrently associated with lower trust and communication in father-child relationships. Therefore, our findings confirm the detrimental effects of divorce mainly on father-child relationships, as parental divorce is negatively associated with lower trust and communication in father-child relationships, even when parental conflict is taken into account. Thus, in agreement with other studies, parental conflict is associated with more negative mother-child and father-child relationship quality, whereas parental divorce is more strongly associated with negative father-child relationships (e.g.,

Riggio and Valenzuela 2011). Our findings also suggest that when adult children observe frequent, intense, and both resolved and unresolved conflicts between parents, they report lower trust, communication, and alienation in the relationship with both parents. Thus, observing frequent and intense conflictive interactions between parents, regardless of being resolved or not, would be equally negatively influential, given that, in both cases, adult children report lower trust and communication along with higher alienation in the relationship with both parents. This does not confirm our expectations regarding the positive effect of high resolved interparental conflict (hypothesis 4).

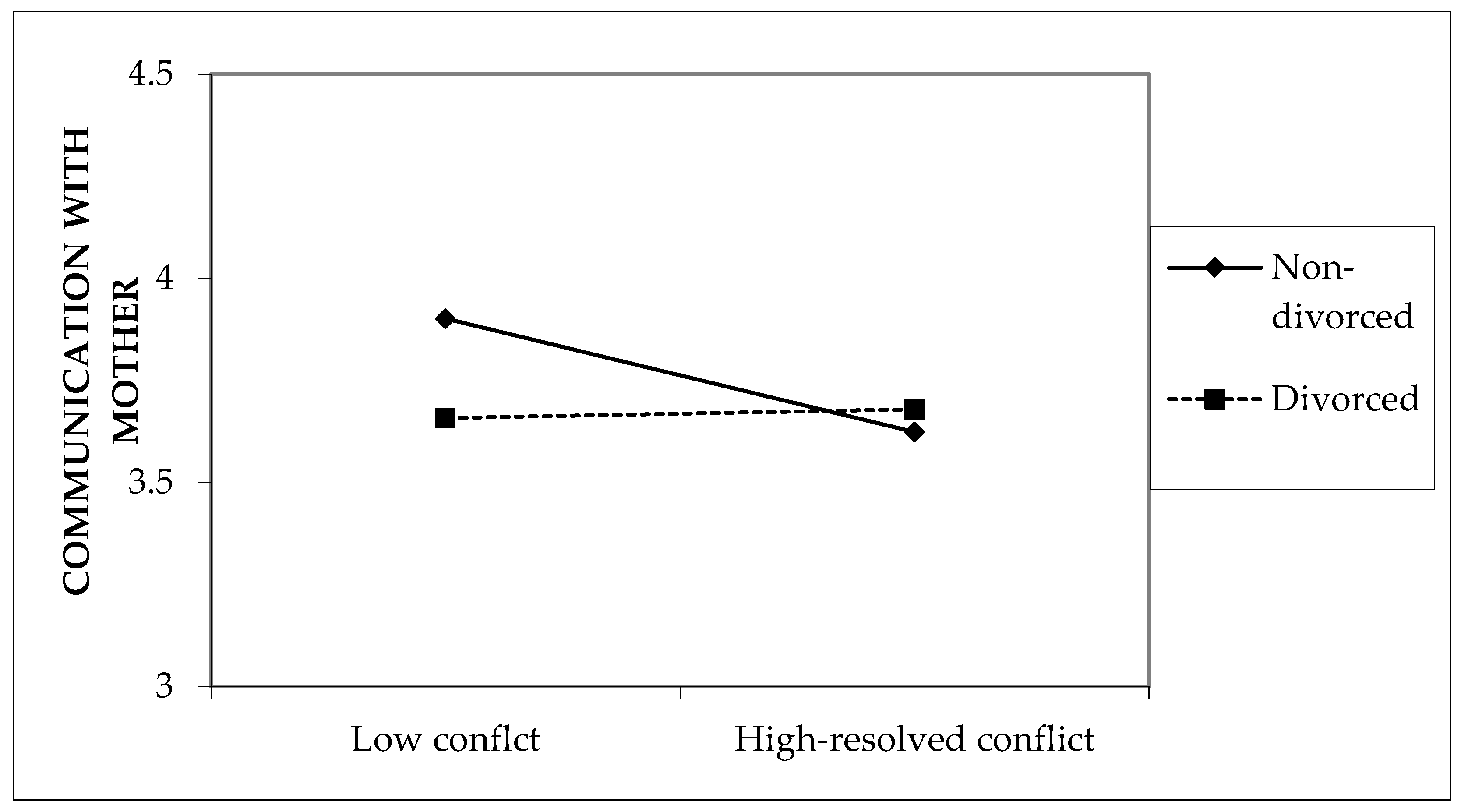

In addition, the results of this study indicate that parental divorce moderates the effects of high resolved interparental conflict on mother-child communication (hypothesis 5). Specifically, adult children from non-divorced families whose parents remained in a high conflict marriage showed lower communication with their mother than when the level of conflict between their parents was low. Conversely, among young adult children from divorced families, higher levels of conflict in the parental marital relationship were not associated with lower communication in mother-child relationships, such that the level of mother-child communication remained the same regardless of interparental conflict. These results would support the stress-relief hypothesis (

Wheaton 1990), which suggests that parental divorce might relieve the stress derived from continued exposure to high levels of parental conflict. That is, parental divorce might be a protective factor for mother-child communication under adverse circumstances, such as high parental conflict. This is consistent with the study conducted by

Yu et al. (

2010), who concluded that parental divorce has a buffering effect on mother–daughter relationships when the interparental relationship is characterized by high levels of conflict. However, in agreement with other studies, and contrary to what we expected, our findings did not suggest such significant interaction for the other variables that define the quality of father-child and mother-child relationships (e.g.,

Riggio 2004). Therefore, our expectations regarding the interactive effect between parental divorce and conflict were partially confirmed.

Study Limitations, Strengths and Implications

Our results should be seen in the light of several limitations. First, this study had a retrospective and cross-sectional design. This makes it difficult to infer causal conclusions, as adult children of divorce reported on parental conflict prior to divorce. Emerging adults might have provided information about past interparental relationships based on their current life stress or current post-divorce interparental relationships. Thus, participants may not be able to recall accurately past parental relationships. Some other investigations have used prospective longitudinal data to enhance the reliability of measures (e.g.,

Lee 2019). Therefore, future studies should focus on conducting a longitudinal follow-up design study with a Spanish population, in order to precisely control the actual pre-divorce parental conflict level, by also analyzing interparental conflict from parents’ perspective. In addition, in our study, we uniquely analyzed college and vocational school students. Given the age range of our sample, future studies should replicate this investigation with a broader and more heterogeneous sample. Next, parental divorce was assessed as a dichotomous variable by asking participants whether their parents were divorced or separated. Divorce is a diverse experience, and several circumstances surrounding the divorce process might explain better children’s reactions to divorce (e.g.,

Yárnoz-Yaben and Garmendia 2015). Besides, parental divorce does not always affect parent-child relationships to the same degree. That is, several factors surrounding the divorce experience, such as contact and closeness with non-custodial parents, type of custody (e.g., shared or sole custody), parents’ distress and adjustment following divorce, the amount of interparental conflict, or diminished financial resources might better explain the effects than divorce per se (

Amato 2010;

Kelly and Emery 2003). Thus, future studies should focus on the examination of other variables related to the divorce process, in order to detect factors that might explain variations in the effects of parental divorce on parent-child relationship quality. A final limitation has to do with not examining protective factors, such as authoritative parenting, both parents’ psychological wellbeing, parents’ effective co-parenting relationship in the post-divorce period, or children’s individual characteristics, such as their effective coping skills or psychosocial maturity. Analyzing these variables might help explain a reduced effect of both parental divorce and conflict (

Amato 2014;

DeBoard-Lucas et al. 2010;

Kelly and Emery 2003;

Lee 2018;

Rejaäan et al. 2021;

Yeung 2021). Moreover, the study of these factors could be of use to gather important information in order to make preventive and clinical intervention efforts to reduce the negative effects of both parental divorce and conflict.

Despite the limitations of this study, it contributes to the investigation of emerging adults’ father-child and mother-child relationship quality in several ways. First, the associations between parental divorce and both high resolved and high unresolved interparental conflict with trust, communication, and alienation in mother-child and father-child relationships were analyzed by testing simultaneously their effect in a non-widely studied sample and cultural context. Another important contribution refers to the study of the role of parents’ gender, as many studies have not focused on the differential effects of parental divorce and conflict on mother-child and father-child relationships separately. In addition, this study analyzed the interaction between parental divorce and conflict in order to examine the moderating role of parental divorce in mother-child and father-child relationships. Overall, our findings contribute to better understanding the effects of parental divorce on parent-child relationships during emerging adulthood, and add to the existing literature, suggesting that interparental conflict is more strongly associated with both mother-child and father-child relationship quality in young adulthood more so than parental divorce. In addition, parental divorce is more strongly related to lower father-child relationship quality than to mother-child relationship quality. Thus, our results highlight the long-term consequences of parental divorce and conflict and suggest the importance of analyzing more factors (e.g., child’s gender and age at time of divorce) in order to extend our knowledge about the way through which these stressful family experiences might shape emerging adult children’s relationships with their parents.

These findings have implications for public policies and preventive interventions for divorced and non-divorced families with dysfunctional family dynamics. Parental stress related to dysfunctional family dynamics derived from conflictive interactions between parents might diminish parents’ sensitivity, responsiveness, and warmth toward their children’s needs, which may have detrimental effects on parent-child relationship quality, even during emerging adulthood. Thus, more efforts should be made to implement and design psychosocial prevention programs aimed at strengthening parental relationships, along with improving parental sensitivity through attachment-based interventions (

Berlin et al. 2016). In addition, although in the current study, parental divorce was negatively associated with both mother-child and father-child relationship quality, emerging adult children’s current perceptions of the relationship with their father seemed to be more damaged. Therefore, intervention programs focused on improving children’s adjustment to divorce should provide tools to enhance father-child relationships.