Food Itineraries in the Context of Crisis in Catalonia (Spain): Intersections between Precarization, Food Insecurity and Gender

Abstract

:1. Introduction

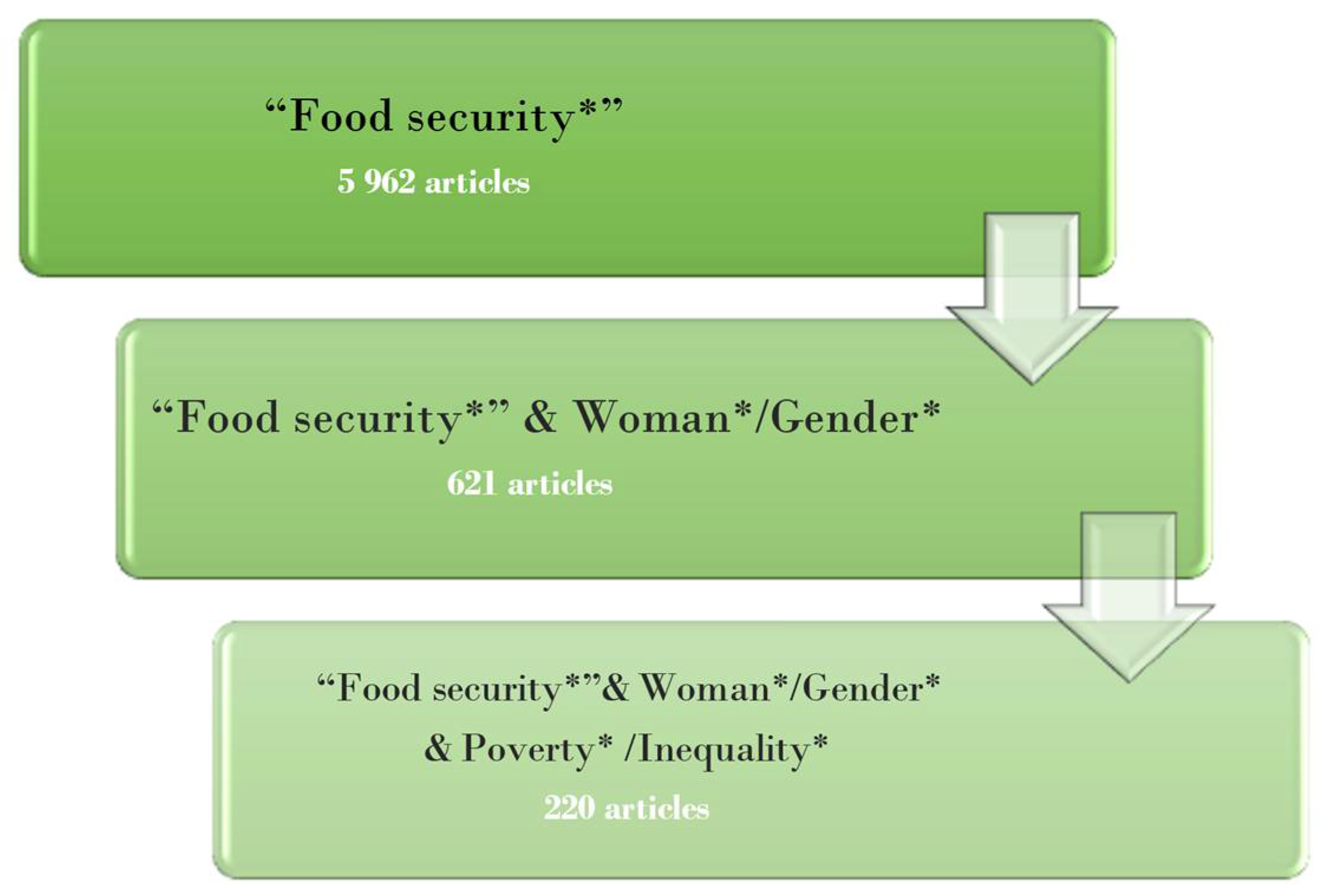

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

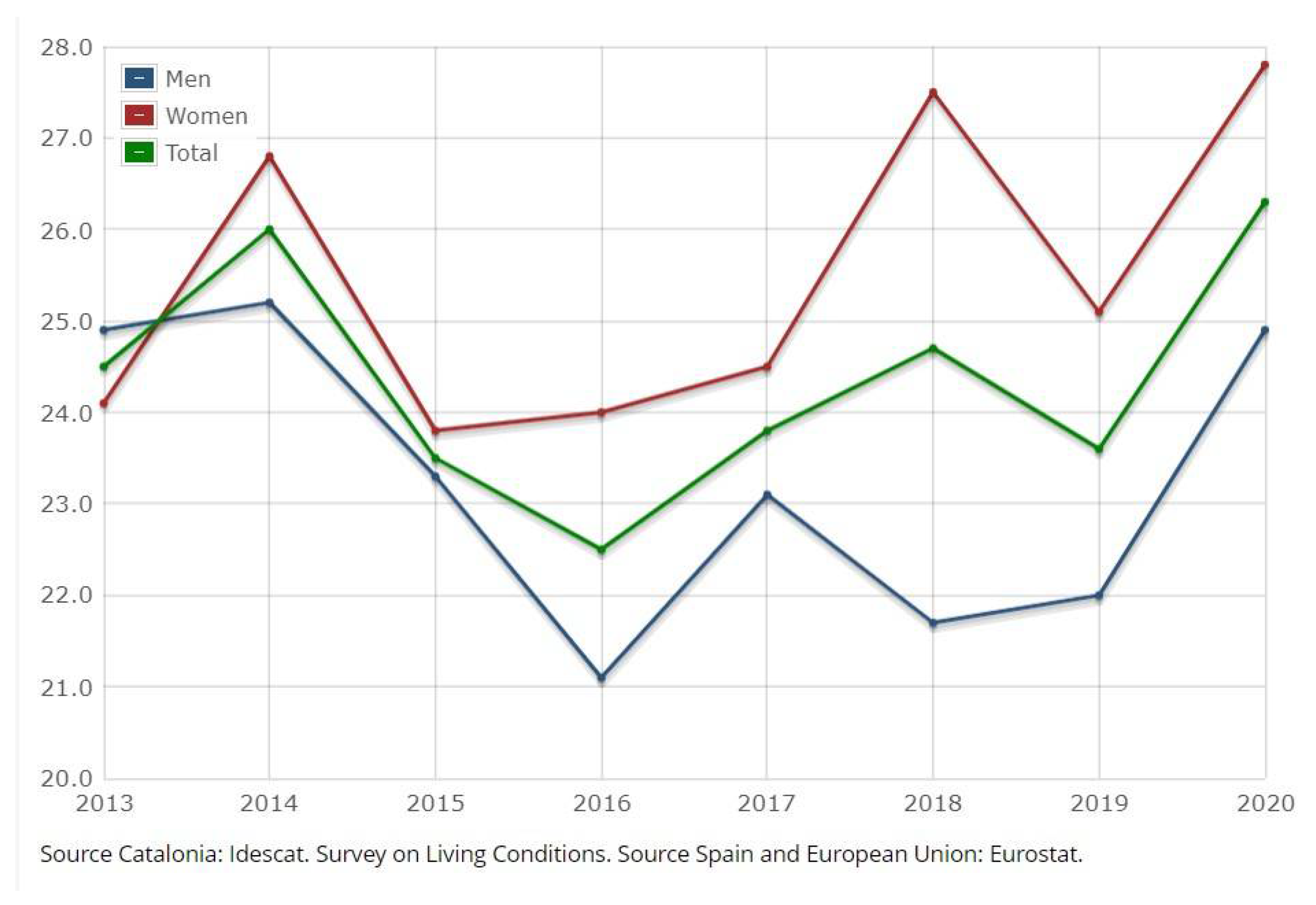

3.1. Living in Times of Crisis

3.2. Feminization of Poverty and Food Insecurity

3.3. Food Itineraries as a Expression of Increasingly Precarization

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | INE, Instituto Nacional de Estadística. https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=10011 (accessed on16 May 2021). |

| 2 | Idescat. Institut d’Estadística de Catalunya. https://www.idescat.cat/indicadors/?id=anuals&n=10412&lang=es (accessed on 16 May 2021). |

| 3 | However, some references from professionals have also been used to support the arguments put forward by people living in precarious situations. |

| 4 | Ministry data from 7 July 2021. https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/situacionActual.htm (accessed on 1 July 2021). |

| 5 | https://d500.epimg.net/descargables/2021/03/09/f7fac84299f53d552054762b79091967.png (accessed on 29 June 2021). |

| 6 | The IMV was approved by Royal Decree Law 20/2020, of 29 May. |

| 7 | ERTE, Expediente de Regulación Temporal. Approved in Royal Decree Law 8/2020, of 17 March 2020, and modified in the RD Law 30/2020, in September of that same year. |

| 8 | |

| 9 | https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/alimentacion/temas/estrategia-mas-alimento-menos-desperdicio/bloque1.aspx (accessed on 7 July 2021). |

References

- Alonso, Luis Enrique, and Carlos Jesús Fernández. 2013. Debemos aplacar a los mercados: El espacio del sacrificio en la crisis financiera actual. Vínculos de Historia. 2: 97–119. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, Luis, and Oscar Cantó. 2018. Ciclo económico, clases medias y políticas públicas. In Tercer Informe Sobre la Desigualdad en España. Madrid: Fundación Alternativas. [Google Scholar]

- Borch, Anita, and Unni Kjaernes. 2016. Food security and food insecurity in Europe: An analysis of the academic discourse (1975–2013). Appetite 103: 137–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramall, Rebecca. 2013. The Cultural Politics of Austerity: Past and Present in Austere Times. Palgrave Macmillan Memory Series; London: Basingstoke. [Google Scholar]

- Broussard, Nzinga H. 2019. What explains gender differences in food insecurity? Food Policy 83: 180–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caritas. 2016. Fràgils. L’alimentació com a dret de ciutadania. Barcelona: Caritas. [Google Scholar]

- Caritas. 2021. Un año Acumulando Crisis. La Realidad de las Familias Acompañadas por Cáritas en Enero de 2021. Observatorio de la Realidad Social, Col. La crisis de la Covid-19, núm. 3. Madrid: Caritas. [Google Scholar]

- Comas d’Argemir, D. 1996. Antropología Económica. Barcelona: Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- EAPN, European Antipoverty Network. 2021. Valoración de las nuevas medidas del Ingreso Mínimo Vital. Informe de posicionamiento EAPN España. Madrid: EAPN, Available online: https://www.eapn.es/publicaciones (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- EPA. 2019. Encuesta de Población Activa. Available online: https://www.ine.es/daco/daco42/daco4211/epa0419.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- EPA. 2021. Encuesta de Población Activa. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176918&menu=ultiDatos&idp=125473597659 (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- Escajedo, Leire, Alberto López-Basaguren, and Esther Rebato Ochoa, eds. 2018. Derecho a una Alimentación Adecuada y Despilfarro Alimentario. València: Tirant lo Blanch. [Google Scholar]

- FAO, Organización Panamericana de la Salud OPS, World Food Programme WFP, and United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund UNICEF. 2019. Panorama de la Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutricional en América Latina y el Caribe 2019. 135. Licencia: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO, Santiago: Food and Agriculture Organization, FAO. [Google Scholar]

- FAO, Fondo Internacional de Desarrollo Agrícola FIDA, World Food Programme WFP, United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund UNICEF, and World Health Organization, WHO. 2020. El Estado de la Seguridad Alimentaria y la Nutrición en el Mundo. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ca9692en/online/ca9692en.html (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Fernández, Daniel. 2017. Los salarios en la recuperación española. Cuad Info Econ 260: 1–12. Available online: https://www.funcas.es/Publicaciones/Sumario.aspx?IdRef=3-06260 (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- FESBAL Federación Española de Bancos de Alimentos. 2019. Memoria Anual (Serie 2017–2019). Madrid: FESBAL, Available online: https://www.fesbal.org.es/memorias-anuales (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Fischler, Claude. 1995. El (H)Omnívoro: El Gusto, la Cocina y el Cuerpo. Barcelona: Anagrama. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación FOESSA. 2020. Análisis y Perspectivas 2020. Distancia Social y Derecho al Cuidado. Caritas. Madrid: Fundación FOESSA. [Google Scholar]

- Garro, Linda C., and Cheryl Mattingly. 2001. Narrative as construct and as construction: An introduction. In Narrative and the Cultural Construction of Illness and Healing. Edited by Cheryl Mattingly and Linda C. Garro. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia-Arnaiz, Mabel. 2015. Comemos lo Que Somos. Reflexiones Sobre Cuerpo, Género y Salud. Barcelona: Icaria. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia-Arnaiz, Mabel. 2017. Taking measures in times of crisis: The political economy of obesity prevention in Spain. Food Policy 68: 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia-Arnaiz, Mabel. 2019. Eating outside the home: Food practices as a consequence of economic crisis in Spain. In Food and Sustainability in the Twenty First Century. Edited by Paul Collinson, Iain Young, Lucy Antal and Helen Macbeth. Oxford: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia-Arnaiz, Mabel, Lina Casadó-Marin, and Mireia Campanera. 2021. Antropologías del hambre: (in)seguridad alimentaria en contextos de precarización. Revista de Antropología Social 30: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, Daphne C., Layton M. Reesor, and Rosenda Murillo. 2017. Food insecurity and adult overweight/obesity: Gender and race/ethnic disparities. Appetite 117: 373–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE, Instituto Nacional de Estadística. 2018a. Encuesta de Población Activa, Módulo Conciliación entre la vida laboral y la familiar. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dynt3/inebase/index.htm?type=pcaxis&path=/t22/e308/meto_05/modulo/base_2011/2018/&file=pcaxis&L=0 (accessed on 23 May 2021).

- INE, Instituto Nacional de Estadística. 2018b. España en cifras. Available online: https://www.ine.es/prodyser/espa_cifras/2018/2/ (accessed on 23 May 2021).

- INE, Instituto Nacional de Estadística. 2021. Encuesta de Población Activa, serie 2009–2020. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=10943#!tabs-grafico (accessed on 23 May 2021).

- Lambie-Mumford, Hannah. 2017. Hungry Britain: The Rise of Food Charity. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Llano, Juan Carlos (coord.). 2019. El Estado de la Pobreza. 9º Informe 2019. Madrid: EAPN España. [Google Scholar]

- Llano, Juan Carlos (coord.). 2020. El Estado de la Pobreza. 10º Informe 2019. Madrid: EAPN España. [Google Scholar]

- Llobet, Marta, Paula Durán Monfort, Claudia Rocío Magaña González, Araceli Muñoz García, and Eugenia Piola Simioli. 2020. Précarisation alimentaire, résistances individuelles et expériences pratiques: Regards locaux, régionaux, transnationaux. Anthropology of Food 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorey, Isabell. 2015. State of Insecurity: Government of the Precarious. Londres: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Christopher, Stephanie Ho, Siddharth Singh, and May Y. Choi. 2021. Gender Disparities in Food Security, Dietary Intake, and Nutritional Health in the United States. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 116: 584–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malgesini, Graciela, Silvina Monteros, Aurea Grané, and Rosario Romera. 2018. Valoración del impacto del Fondo de Ayuda Europea para las personas más desfavorecidas (FEAD) en España, a través de la percepción de las personas beneficiarias, Organizaciones y personal de gestión. Boletín Vulnerabilidad Social 16: 1–147. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, José Moisés. 2019. Nueva Desigualdad en España y Nuevas Políticas para Afrontarla. Barcelona: Observatorio Social de La Caixa. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Molly A., and Adam M. Lippert. 2012. Feeding her children, but risking her health: The intersection of gender, household food insecurity, and obesity. Social Science Medicine 74: 1754–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McIntosh, William Alex. 1996. World Hunger as a Social Problem. Edited by Donna Maurer and Jeffery Sobal. Eating Agendas. New York: Aldine de Gruytier. [Google Scholar]

- Messer, Ellen. 2009. Rising Food Prices, Social Mobilization, and Violence: Conceptual Issues in Understanding and Responding to the Connections Linking Hunger and Conflict. In The Global Food Crisis: New Insights into an Age-Old Problem. Edited by David Himmelgreen. Memphis: NAPA Bulletin, vol. 32, pp. 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mennell, Stephen. 1985. All Manners of Food. Eating and Taste in England and France from the Middle Ages to the Present. Londres: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Neogy, Suniti. 2010. Gender Inequality, Mothers’ Health, and Unequal Distribution of Food: Experience from a CARE Project in India. Gender and Development 18: 479–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. 2006. Food Insecurity and Hunger in the United States: An Assessment of the Measure. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Observatori d’Igualtat de Gènere. 2020. Les Dones a Catalunya 2020. Barcelona: Institut Català de les Dones. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell, Rebecca, and Julia Brannen. 2016. Food, Families and Work. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Offenhenden, María. 2017. ‘Si hay que romperse, una se rompe’. El trabajo del hogar y la reproducción social estratificada. Ph.D. dissertation, Anthropology, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, Joanne G., Jennifer Russomanno, Andreas A. Teferra, and Jennifer M. Jabson Tree. 2020. Disparities in food insecurity at the intersection of race and sexual orientation: A population-based study of adult women in the United States. SSM Population Health 12: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paugam, Serge. 2013. La Disqualification Sociale, Essai sur la Nouvelle Pauvreté. Paris: P.U.F. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, Diane. 1978. The Feminization of Poverty: Women, Work, and Welfare. Urban and Social Change Review 11: 1–2, 28–36, 78. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez de Armiño, Karlos. 2018. Los bancos de alimentos en España durante la crisis: Su papel y discurso en un contexto de erosión de los Derechos sociales. In Derecho a una Alimentación Adecuada y Despilfarro Alimentario. Edited by Escajedo Leire, Esther Rebato and Alberto López Basaguren. València: Tirant lo Blanch, pp. 225–61. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, Sabine, Tobias Ritter, and Elke Oestreicher. 2015. Food Insecurity in German households: Qualitative and Quantitative Data on Coping, Poverty Consumerism and Alimentary Participation. Social Policy and Society 14: 483–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottier, Johan. 1999. The Anthropology of Food. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prada-Trigo, José. 2018. Vulnerabilidad territorial, crisis y ‘post-crisis económica’: Trayectoria y persistencia a escala intraurbana. Scripta Nova 22: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riches, Graham, and Tiina Silvasti. 2014. First World Hunger Revisited: Food Charity or the Right to Food. Londres: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Russomanno, Jennifer, and Jennifer M. Jabson Tree. 2020. Food insecurity and food pantry use among transgender and gender nonconforming people in the Southeast United States. BMC Public Health 20: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, Carolyn, and Anouk Patel-Campillo. 2014. Feminist food justice: Crafting a new vision. Feminist Studies 40: 396–410. [Google Scholar]

- Subirats, Marina. 2012. Barcelona: De la Necesidad a la Libertad. Las Clases Sociales en los Albores del Siglo XXI. Barcelona: UOC. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2015. The World’s Women. Trends and Statistics. Nueva York: UN. [Google Scholar]

- Valls, Francesc, and Angel Belzunegui. 2014. La Pobreza en España desde una Perspectiva de Género. Madrid: Fundación Foessa, Available online: http://www.foessa2014.es/informe/uploaded/documentos_trabajo/15102014141447_8007.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2019).

- Vasco Ramos Vasco, Mónica Truninger, Sónia Goulart Cardoso, and Fábio Rafael Augusto. 2020. Researching children’s food practices in contexts of deprivation: Ethical and methodological challenges. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. [Google Scholar]

- Warde, Alan. 1997. Consumption, Food & Taste: Culinary Antinomies and Commodity Culture. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

| Topics | Analytical Categories (Codes) | Cross-Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Precarization process | Suffering, impoverishment, uncertainty, casualization, underemployment, non-contributory benefits, difficulty in paying bills, low wages, informal economy, housing conditions, financial help, food assistance | Spaces, access, temporariness, gender (identifying the gender of the subject, gender analysis), health, social class |

| Individual and collective responses to precarization | “empowerment”, activism, agency | |

| Food security—insecurity | Irregular access to food, access to healthy food, food quality (condition of food), varied diet, household food management, food origin | |

| Excess weight—precarity | quantity of food, quality of food, emotional health, physical activity, eating habits | |

| Food itineraries | Institutional circuits, neighborhood circuits, formal-informal itineraries, soup kitchen, parish church, Caritas, municipal spaces, community supermarket, food bank, supermarkets, allotments, market, street market | |

| Food strategies | Type of food (cheaper products, pre-cooked, fresh, processed, ultra-processed), purchase of food (changes in the place of purchase) | |

| Gastro-anomic—gastronomic structures | Mealtimes, eating spaces, access to kitchen, food over the day (number of meals, type of meals, time of meals, eating places, eating with others, time spent cooking) | |

| Formal support networks | Community organization, social services, businesses with CSR (restaurants, supermarkets, etc.), NGOs, AMPAS (parent-teacher associations), CAP (community health centers), etc. | |

| Informal support networks | Support from family, neighbors, friends | |

| Healthcare for excess weight in precarious situations | Prescribed treatment, diet, diseases associated with precarity (mental health, obesity, physical pain, malnutrition), physical activity, dietary practices, health intervention (individual, group, community), social inequality, detecting precarity, community intervention, health programs, limitations of interventions, protocols | |

| Public policies for prevention and intervention (obesity, precarity) | Prevalence of obesity, comparative policy, social variables of obesity, socioeconomic status (social class), socio-demographic variables (age, gender, etc.), obesity prevention programs |

| Service | Food Aid Received | Organization | Organization Type | City |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purse card | Debit card to buy food and other essentials | Barcelona City Council | Public administration | Barcelona |

| Social supermarket | Fortnightly food parcels (including fresh and frozen products) | DISA Sant Andreu, Caritas | Charitable organization linked to the Catholic Church | Barcelona |

| Soup kitchen | Weekly food parcels and several days’ worth of food in Tupperware (including fresh produce). | Gregal soup kitchen | Neighborhood social organization | Barcelona |

| Soup kitchen | Lunch from Monday to Friday, takeaway meals (weekends) | Bonavista soup kitchen (Joventut i Vida Foundation) | Foundation | Tarragona |

| Soup kitchen | Lunch Monday to Friday, takeaway meals (weekends and dinner) | Can Pedró Foundation | Foundation | Barcelona |

| Food parcels and children’s canteen | Fortnightly food parcels. School meals | Mossén Frederic Bara Foundation | Charitable Christian foundation | Reus |

| Food parcels | Fortnightly food parcels | Tarragona Red Cross | NGO | Tarragona |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gracia-Arnaiz, M.; Garcia-Oliva, M.; Campanera, M. Food Itineraries in the Context of Crisis in Catalonia (Spain): Intersections between Precarization, Food Insecurity and Gender. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10100352

Gracia-Arnaiz M, Garcia-Oliva M, Campanera M. Food Itineraries in the Context of Crisis in Catalonia (Spain): Intersections between Precarization, Food Insecurity and Gender. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(10):352. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10100352

Chicago/Turabian StyleGracia-Arnaiz, Mabel, Montserrat Garcia-Oliva, and Mireia Campanera. 2021. "Food Itineraries in the Context of Crisis in Catalonia (Spain): Intersections between Precarization, Food Insecurity and Gender" Social Sciences 10, no. 10: 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10100352

APA StyleGracia-Arnaiz, M., Garcia-Oliva, M., & Campanera, M. (2021). Food Itineraries in the Context of Crisis in Catalonia (Spain): Intersections between Precarization, Food Insecurity and Gender. Social Sciences, 10(10), 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10100352