Effectiveness of Regulation of Educational Requirements for Non-Bank Credit Providers in Czech Republic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Training

3. Methods and Data

- Q1:

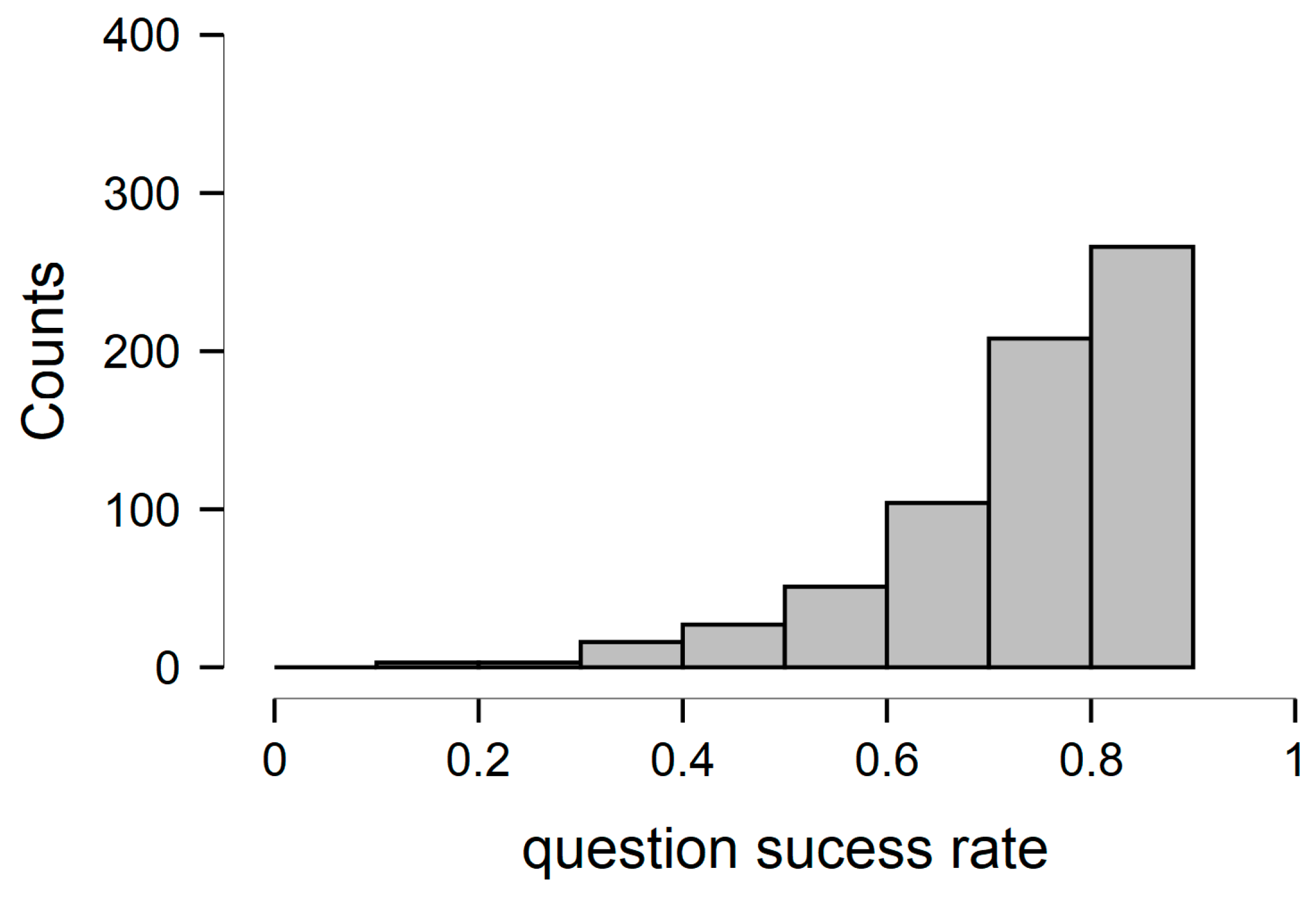

- Is the success rate of individual questions balanced?

- Q2:

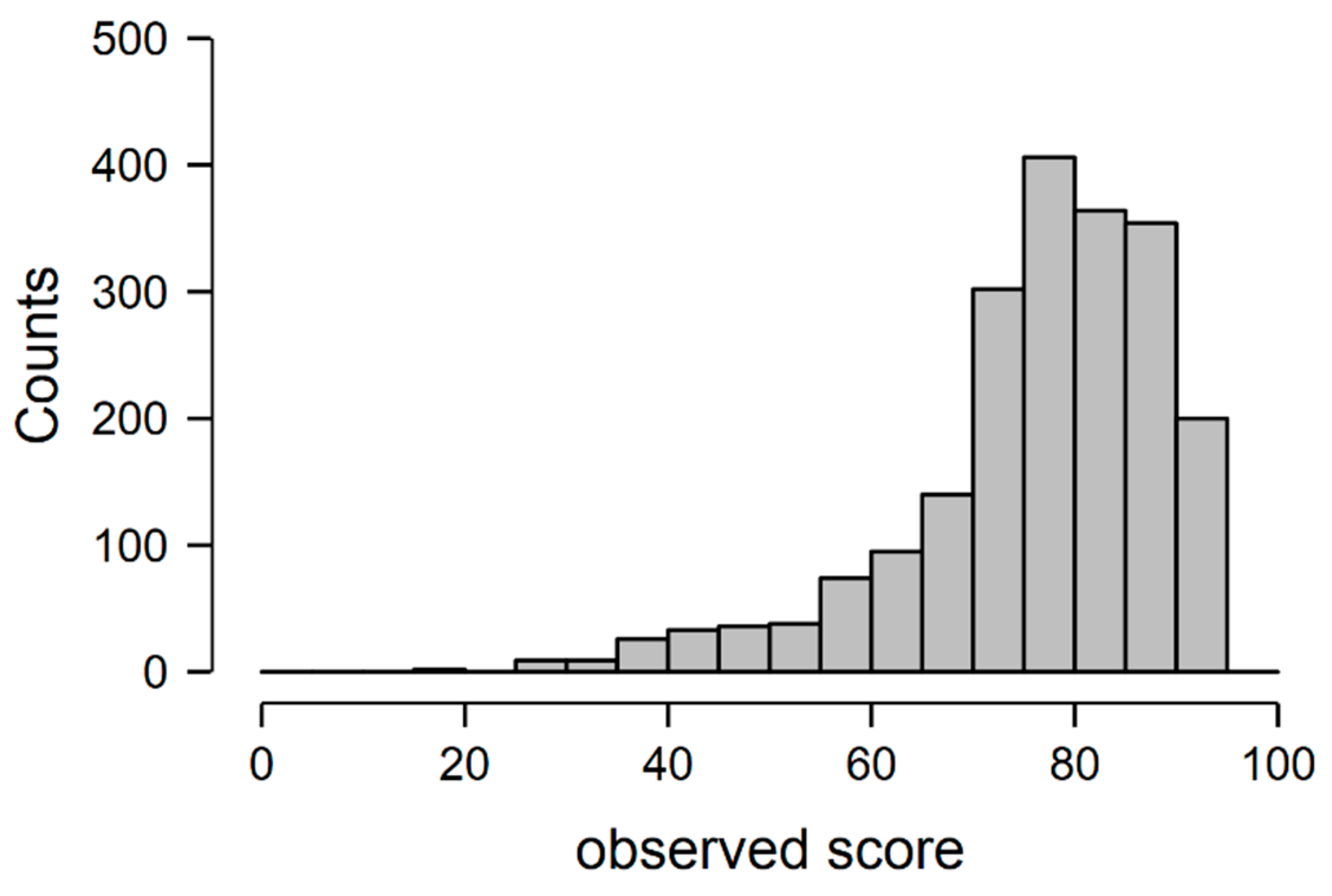

- Is the expected (mean) point score for each variant of the test balanced?

- Q3:

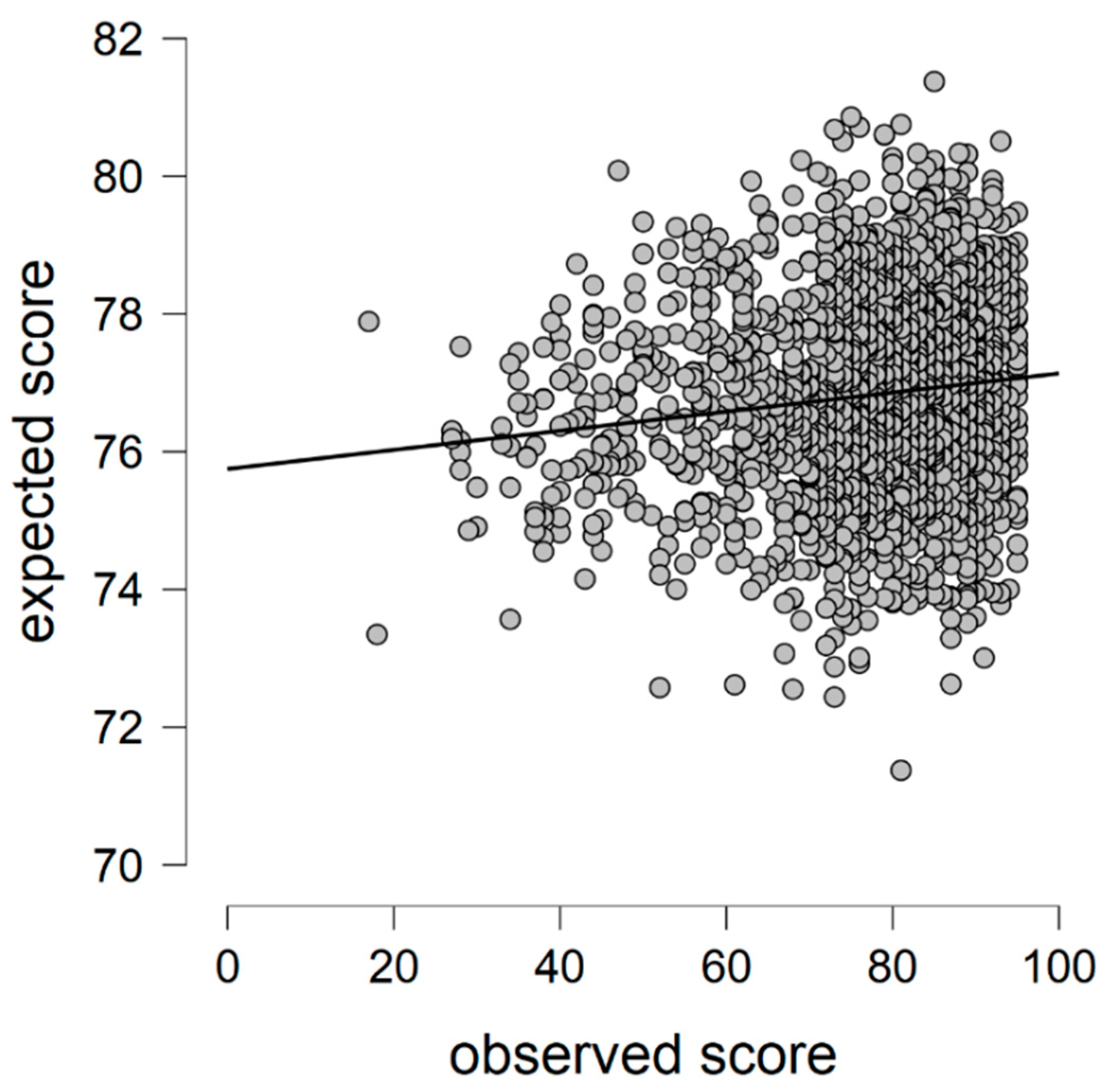

- Does the expected value of each variant point score correspond to an observed point score?

- Q4:

- Can the test be passed by a mere random selection of answers or when information about a variant set already leaked?

4. Results

4.1. Examination Test Assessment

4.2. Regulation Impact and Examination Tests

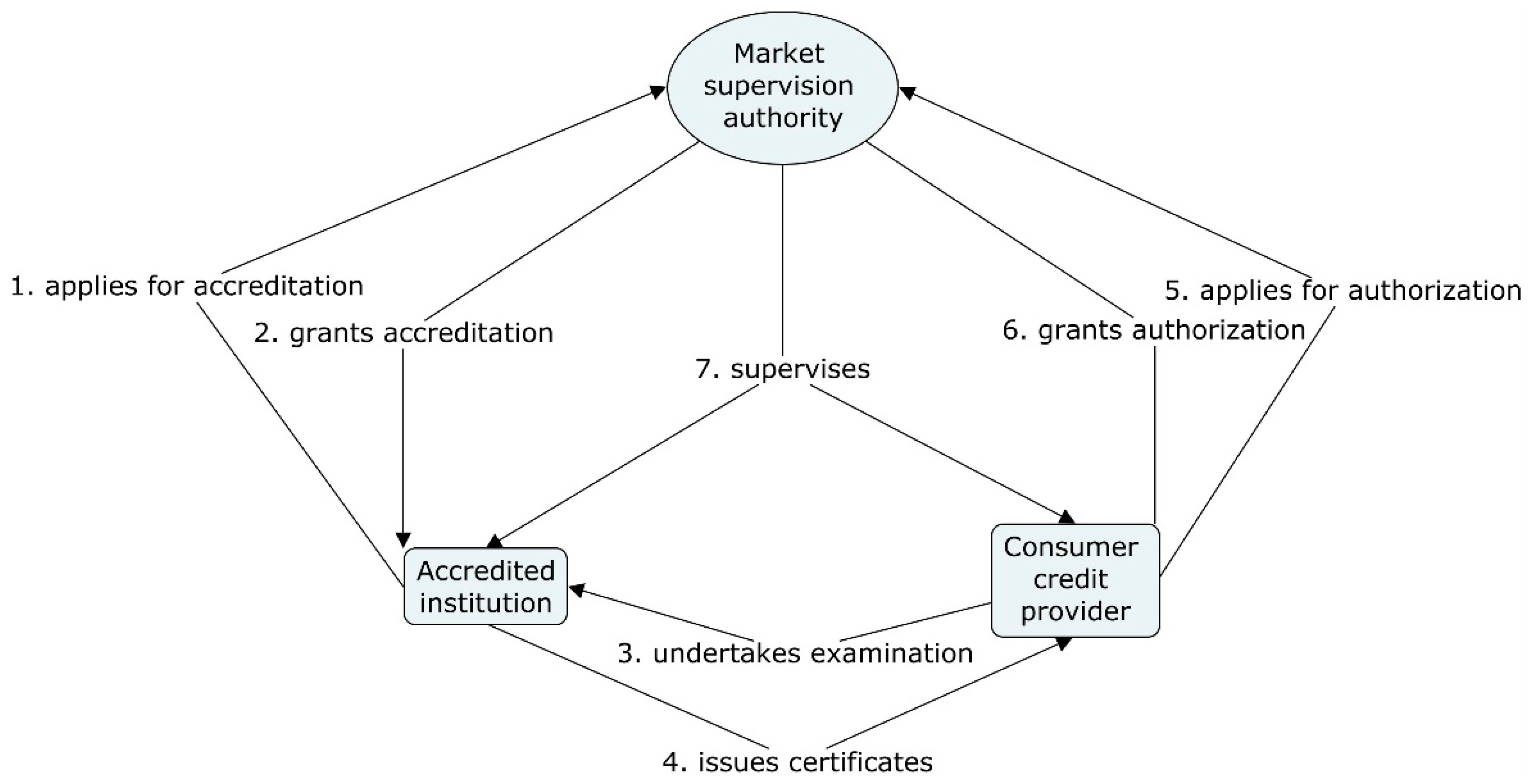

- Private entity, mostly in the form of a private limited company, submits an application for accreditation to CNB. The request is assessed according to the requirements from article 9 of (Czech National Bank 2016a) and article 63(2) of (Parliament of the Czech Republic 2016). One of them relates to the board of examiners. There is a rule that a majority of the members of the board of examiners has to be independent of the accredited person or of the business group of which the accredited person is a member. Such independent examiners are then, e.g., academic professionals in a field of finance or economy or practicing professionals. A board of examiners list and their CVs are a part of required application documents in order to keep examination unbiased.

- Market supervisor (CNB) issues accreditation in case of meeting the requirements.

- Employees of a consumer credit provider have to apply for professional qualifications examination.

- Accredited institution organizes examination according to the requirements and issues a certificate of professional qualifications for successful trainees.

- Consumer credit provider can apply for an authorization to pursue consumer credit business. There is, among other requirements, obligatory duty to prove that all staff participating on provision and intermediation of consumer credit hold a certificate professional qualification.

- Market supervisor (CNB) grants authorization in case of meeting the requirements.

- The whole process is under market supervisor’s supervision. Accredited institutions e.g., report professional qualifications examination terms in advance to the market supervisor. Any examination can be visited by supervisor’s inspection team, which unannounced, arrives at the beginning of an examination and performs a supervision of examination room, question delivery, examiner’s identity, etc.

- Theoretical part: 45 questions had only one correct answer, which is rated at one point. Another 15 questions had multiple correct answers, which are rated two points.

- The practical part contained 2 case studies with 5 questions for 2 points.

- The total minimum number of points is 72, with the minimum number of points to be achieved at the same time in the theoretical part (45 points) and in the practical part (12 points).

4.3. Preparation of Employees and Examination

- minimum expert knowledge of the financial market

- structure, entities, and functioning of the market

- regulation of the market

- lending and the products of consumer credit other than for house purchase

- related complementary services

- the principles of the process for assessing a consumer’s creditworthiness

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abadzi, Helen. 2016. Training 21st-century workers: Facts, fiction and memory illusions. International Review of Education 62: 253–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austrian Financial Market Authority. 2019. Austrian Banking Act. Vienna: Austrian Financial Market Authority. [Google Scholar]

- Bank of Portugal. 2017. Decree-Law 74-A/2017 Partially Transposing Directive 2014/17/EU on Credit Agreements for Consumers for Residential Properties. Lisbon: Bank of Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Best, John W., and James V. Kahn. 2006. Research in Education, 10th ed. Boston: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Bjork, Robert A., John Dunlosky, and Nate Kornell. 2013. Self-Regulated Learning: Beliefs, Techniques, and Illusions. Annual Review of Psychology 64: 417–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, Kenneth G. 2001. Using computers to deliver training: Which employees learn and why? Personnel Psychology 54: 271–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgarian National Assembly. 2018. Consumer Loan Act. Sofia: Bulgarian National Assembly. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Benjamin A., Russell Coff, and David Kryscynski. 2012. Rethinking Sustained Competitive Advantage from Human Capital. Academy of Management Review 37: 376–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, Wayne F. 2019. Training trends: Macro, micro, and policy issues. Human Resource Management Review 29: 284–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bank of Ireland. 2017a. Minimum Competency Code. Dublin: Central Bank of Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Central Bank of Ireland. 2017b. Minimum Competency Regulations. Dublin: Central Bank of Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Louis, Lawrence Manion, and Keith Morrison. 2007. Research Methods in Education, 6th ed. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Crook, T. Russell, Samuel Y. Todd, James G. Combs, David J. Woehr, and David J. Ketchen. 2011. Does human capital matter? A meta-analysis of the relationship between human capital and firm performance. Journal of Applied Psychology 96: 443–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czech National Bank. 2016a. Decree No. 381 of 16 November 2016, on Applications, Notifications and the Submitting of Statements Pursuant to the Consumer Credit Act. Praha: Czech National Bank, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Czech National Bank. 2016b. Decree No. 384/2016 Coll. of 23 November 2016 on Professional Qualifications for the Distribution of Consumer Credit. Praha: Czech National Bank, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Czech National Bank. 2017. Supervisory Benchmark No. 1/2017—The Manner of Generating Tests When Organising Professional Examinations Pursuant to Act No. 257/2016 Coll., on Consumer Credit. Praha: Czech National Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, Tarcisio Pedro, Mauricio Leite, Jaqueline Carla Guse, and Vanderlei Gollo. 2017. Financial and economic performance of major Brazilian credit cooperatives. Contaduría y Administración 62: 1442–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozdova, Anna A., and Anya I. Guseva. 2017. Modern Technologies of E-learning and its Evaluation of Efficiency. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 237: 1032–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council. 2014. Directive 2014/17/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 February 2014 on credit agreements for consumers relating to residential immovable property. Official Journal of the European Union L60: 34–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, Joseph F., ed. 2014. Multivariate Data Analysis: Pearson New International Edition, 7th ed. Essex: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hungarian Ministry of National Economy. 2015. Decree No. 40/2015. (XII. 30.) NGM of the Minister for National Economy on Duties Connected with Official Training and Official Examination for Financial Services Intermediaries, Insurance Intermediaries and Capital Market Traders. Budapest: Hungarian Ministry of National Economy. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, Robin H. 2012. Exploring the use of video podcasts in education: A comprehensive review of the literature. Computers in Human Behavior 28: 820–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaźmierczyk, Jerzy, Gulnara Fatykhovna Romashkina, and Przemysław Macholak. 2020. Lifelong learning as an employee retention tool. Comparative banking analysis. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 8: 1064–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Ikram Ullah, Zahid Hameed, and Safeer Ullah Khan. 2017. Understanding Online Banking Adoption in a Developing Country: UTAUT2 with Cultural Moderators. Journal of Global Information Management 25: 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraiger, Kurt. 2008. Transforming Our Models of Learning and Development: Web-Based Instruction as Enabler of Third-Generation Instruction. Industrial and Organizational Psychology 1: 454–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, Omar Rabeea, Islam A. Nassar, and Mahmoud Khalid Almsafir. 2019. Knowledge management processes and sustainable competitive advantage: An empirical examination in private universities. Journal of Business Research 94: 320–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, Jeanne C., and Karie Willyerd. 2010. The 2020 Workplace: How Innovative Companies Attract, Develop, and Keep Tomorrow’s Employees Today, 1st ed. New York: Harper Business. [Google Scholar]

- Menshikova, Maria, Alberto Romolini, Illa Sabbatelli, and Marco De Marco. 2017. The Role of Digital Tools and Platforms for Training Programmes Developed by the Organisations of the Banking Sector. In Exploring Services Science. Edited by Stefano Za, Monica Drăgoicea and Maurizio Cavallari. New York: Springer International Publishing, vol. 279, pp. 309–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, Jerome L., Arnold Well, and Robert Frederick Lorch. 2010. Research Design and Statistical Analysis, 3rd ed. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Noe, Raymond A. 2016. Employee Training and Development, 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament and the President of the Hellenic Republic. 2016. Law 4438/2016 Harmonization of Legislation with the Directive European Parliament 2014/17/EU and of the Council of 4 February 2014 on Consumer Credit Agreements for Residential Real Estate and Amending Directives 2008/48/EC and 2013/36/EU and Regulation (EU) No. 1093/2010, and other Provisions of Competence of the Ministry of Finance. Athens: Parliament and the President of the Hellenic Republic. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of the Czech Republic. 2016. Act No. 257/2016 Coll. Of 14 July 2016, on Consumer Credit. 100/2016. Praha: Parliament of the Czech Republic. [Google Scholar]

- Parliamentary Council of the Federal Republic of Germany. 2019. Commercial Code as Amended on February 22, 1999 (Federal Law Gazette I p. 202), Which Was Last Amended by Article 15 of the Law of November 22, 2019. (Federal Law Gazette I p. 1746). Berlin: Parliamentary Council of the Federal Republic of Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Ployhart, Robert E., and Thomas P. Moliterno. 2011. Emergence of the human capital resource: A multilevel model. Academy of Management Review 36: 127–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polish Sejm. 2019. Act on Financial Market Supervision. Warsaw: Polish Sejm. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Aaron M., and J. Kevin Ford. 2003. Learning within a learner control training environment: The interactive effects of goal orientation and metacognitive instruction on learning outcomes. Personnel Psychology 56: 405–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitzmann, Traci, Bradford S. Bell, Kurt Kraiger, and Adam M. Kanar. 2009. A Multilevel Analysis of the Effect of Prompting Self-Regulation in Technology-Delivered Instruction. Personnel Psychology 62: 697–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Sun Young, and Jin Nam Choi. 2014. Do organizations spend wisely on employees? Effects of training and development investments on learning and innovation in organizations: TRAINING AND DEVELOPMENT INVESTMENT AND INNOVATION. Journal of Organizational Behavior 35: 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, Elizabeth T., Connie R. Wanberg, Kenneth G. Brown, and Marcia J. Simmering. 2003. E-learning: Emerging uses, empirical results and future directions. International Journal of Training and Development 7: 245–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Lu, Xiaochao Guo, Zhimei Lei, and Ming Lim. 2019. Social Network Analysis of Sustainable Human Resource Management from the Employee Training’s Perspective. Sustainability 11: 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Other measures can also be found in CCA to reach this goal such as initial capital requirements, creditworthiness procedures, and consumer procedures in a case of default. |

| 2 | We disclose that we had no role in a design of any studied training, examination processes, and related e-learning data processing including data extraction. |

| 3 | software developed in Department of Psychological Methods, University of Amsterdam. |

| Frequency | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trainees | 1027 | 339 | 87 | 25 | 9 | 2 | 1 |

| Success Rate Main Descriptives | Success Rate Percentiles | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.813 | 5th percentile | 0.510 |

| Std. Deviation | 0.153 | 25th percentile | 0.727 |

| Skewness | −1.149 | 50th percentile | 0.849 |

| Minimum | 0.115 | 75th percentile | 0.931 |

| Maximum | 1.000 | 95th percentile | 1.000 |

| Expected Point Score Main Descriptives | Expected Point Score Percentiles | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 78.815 | 5th percentile | 64.528 |

| Std. Deviation | 1.387 | 25th percentile | 75.881 |

| Skewness | −0.021 | 50th percentile | 76.793 |

| Minimum | 71.374 | 75th percentile | 77.770 |

| Maximum | 81.375 | 95th percentile | 79.067 |

| Observed Point Score Main Descriptives | Observed Point Score Percentiles | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 76.788 | 5th percentile | 49.000 |

| Std. Deviation | 12.799 | 25th percentile | 72.000 |

| Skewness | −1.284 | 50th percentile | 75.000 |

| Minimum | 17.000 | 75th percentile | 86.000 |

| Maximum | 95.000 | 95th percentile | 92.000 |

| Regulator Requires Submission of Training Program | Regulator Requires Knowledge/Skill Certification | Regulator Supervises Examination Companies | Certification by Registered Private Companies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | x | x | ||

| Bulgaria | ||||

| Croatia | x | x | x | |

| Czech Republic | x | x | x | |

| Germany | x | |||

| Greece | x | x | x | |

| Hungary | x | x | x | |

| Ireland | x | x | ||

| Netherlands | x | x | ||

| Poland | ||||

| Portugal | x | x | x | |

| Slovenia | x | x | x |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soukal, I.; Hamplová, E.; Haviger, J. Effectiveness of Regulation of Educational Requirements for Non-Bank Credit Providers in Czech Republic. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10010028

Soukal I, Hamplová E, Haviger J. Effectiveness of Regulation of Educational Requirements for Non-Bank Credit Providers in Czech Republic. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoukal, Ivan, Eva Hamplová, and Jiri Haviger. 2021. "Effectiveness of Regulation of Educational Requirements for Non-Bank Credit Providers in Czech Republic" Social Sciences 10, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10010028

APA StyleSoukal, I., Hamplová, E., & Haviger, J. (2021). Effectiveness of Regulation of Educational Requirements for Non-Bank Credit Providers in Czech Republic. Social Sciences, 10(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10010028