In 1928, some painters and sculptors living in Bordeaux joined forces to create the group of the AIB, “artistes indépendants bordelais”—which could be translated by “independant artists from Bordeaux”. The name echoed to the “Société des Artistes indépendants”, who organized an annual Salon in Paris from 1884, independent from the official—and also Parisian—Salon. In an ambivalent way, the name of this group suggests that the Parisian art world inspired these artists from Bordeaux, but that they also claimed a strong anchoring in their city. Such as initiative—creating a local market for contemporary art—would be considered as an early attempt at artistic “decentralization”, to use an anachronism. Indeed, in the interwar period, the opposition between Paris and the rest of France was still very strong, as Jean-François Gravier showed in a controversial book. Published in 1947 (

Gravier 1947) and entitled

Paris et le désert français, “Paris and the French desert”, it revealed a huge imbalance in favor of a Parisian macrocephaly, which was stemming from the reign of Louis XIV and was specific to France. In other words, Paris concentrated political and economic capitals, leaving almost nothing to

“la province”—that is the “rest of France”, but in a slight backward and pejorative sense. In the 1960s, Gravier’s book thus paved the way for the

aménagement du territoire, i.e., French land use planning,

With a population ten times smaller than Paris—260,000 inhabitants in the 1920s

1—Bordeaux happened to be the fourth largest city and belonged to

“la province”. When the AIB was created, the city was then considered as the world capital of wine and had industrialized, but it was no longer the first port of France it had been in the 17th and 18th centuries. If Bordeaux was economically dominated by Paris, was it also the case in the art world? The ACA-RES project shows that, in the 18th century, provicial towns like Bordeaux were not lagging behind Paris but rather building artistic interactions between them, through the development of local art academies.

2 Similarly, the 19th century did not turn out to be deserted in

“la province”. In parallel with the Parisian official Salon, artistic exhibitions or local “Salons” bloomed throughout France, for instance in Toulouse with the “Union artistique” beginning in the 1860s, or in the Northern regions since the 1870s (

Buchaniec 2010). Most of the time, local associations of collectors or “friends of the arts” (

amis des arts) organized these provincial exhibitions, e.g., in Nancy, through the (

Société lorraine des Amis des arts) or in Bordeaux, through the (

Société des Amis des Arts) who was responsible for the local Salon, starting in 1851 (

Dussol 1997).

If the provincial art market starts being well studied for the 19th century (

Houssais and Lagrange 2010), the 1920s and 1930s appear like a blind spot and deserve more attention. Indeed, the interwar period was a turning point in the artistic sphere: at the end of the Great War, the official Salon ceased to play the role of “prescriber” in the Parisian market, leaving all power to art galleries and unofficial exhibitions, such as the Salon d’Automne, the Salon des Indépendants or the Salon des Tuileries (

Saint-Raymond 2019). In this new configuration, where the line of sight and the reference point was no longer the Parisian Salon, what was the situation of the provincial art markets? Did a decentralized and economically bouncy art sphere exist? The initiative of the AIB constitutes a well-documented case study

3, that allows testing the efficiency of a local market for contemporary art, as an alternative to the centralized and centripetal Parisian world. Indeed, from 1928 on, the AIB organized an annual exhibition in which they could show their works, and they also printed catalogues indicating the sale prices and all the actors and sponsors of this emerging scene.

This article thus seeks to understand the functioning of this so-called “provincial” alternative to Paris and to measure its potential success, both as a market and as an arbiter of taste for modern art.

Section 1 explores the origin of the AIB Salon, designed for being a tribune of independence and a commercial showcase. This goal is qualified by the statistics of

Section 2: the AIB benefited from the artistic influence of Paris—which they themselves had called for—and, at the same time, suffered the economic consequences of such satellization.

Section 3 thus gives a mixed assessment of this abortive attempt at decentralization. Taking a step back from this case study, the conclusion tackles the issue of “provincialism”.

1. A Local, Independent and Commercial Showcase: The Origins of the Aib

Before analyzing its artistic and commercial success—or failure—it seems necessary to explore the reasons why some artists decided to create the group of the “Artistes indépendants bordelais”, and to organize an annual exhibition in Bordeaux.

Section 1 thus goes back to the history of the AIB, which is already well known (

Cante 1991).

1.1. A Landscape of Five Competing Salons in the 1920s Bordeaux

The AIB opened their first exhibition in 1928, at the “Terrasse du Jardin Public”, a former orangery located in the public garden (

Figure 1).

From 1899, this venue had become the headquarters of five “Salons” in Bordeaux.

4 The oldest and most important one was the “Salon des Amis des Arts”, founded in 1851 by the “Société des Amis des Arts”. This society gathered together some collectors, businessmen and notables who decided to organize an annual exhibition, on the model of the Parisian Salon. The “Société des Amis des Arts” dedided to accept or reject the artworks that the artists submitted to its appreciation, as the Parisian jury would. Its economic functioning relied on a system of subscription and lottery. As Dominique (

Dussol 1997) showed, this Salon had become the biggest one in

la province, with more than 27,000 exhibitors and 49,000 exhibited artworks between 1851 and 1939.

When the “Terrasse du Jardin Public” opened, in 1899, it also welcomed a new exhibition, that of the “Artistes girondins”—

la Gironde being the name of Bordeaux’s department, named after the Gironde estuary. At least in the beginning, the “Artists girondins” positioned themselves as rivals to the Salon des Amis des Arts: contrary to the latter, in which all artists could exhibit their works, they only accepted “local” artists, from Bordeaux and

la Gironde. Taking place in November, the Salon of the “Artistes girondins” was rapidly coined “Salon d’Automne bordelais”, referring to the Parisian “Salon d’Automne” whose first exhibition took place in 1903. However, six years after its birth, the “Artists girondins” split. Led by Paul Quinsac (1858–1929), a former student of Jean-Léon Gérôme at the École des Beaux-Arts de Paris, and a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux, a small group of artists seceded, calling for greater professionalism and commitment to academic style: the “Association d’Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Architectes et Graveurs Domiciliés à Bordeaux” opened their first annual exhibition in 1906, entitled “L’Atelier”. Along with the Salon des Amis des Arts, the Salon des Artistes girondins and L’Atelier, the “Terrasse du Jardin public” welcomed a fourth annual exhibition from 1907, dedicated to local women artists grouped in the “Société des femmes artistes de Bordeaux”.

5Finally, one last Salon appeared in 1909, the “Salon des humoristes”. Created and hosted by three drawers from Bordeaux, Jacques Le Tanneur (1887–1935), Henri Ducot and Georges de Sonneville (1889–1978), this exhibition also displayed cartoons and caricatures by Parisian artists such as Jean-Louis Forain (1852–1931), Francisque Poulbot (1879–1946), Caran d’Ache (1858–1909), Leonetto Cappiello (1875–1942), Adolphe Léon Willette (1857–1926) or Théophie Alexandre Steinlen (1859–1923).

6 After 1918, this Salon became that of the “Dessinateurs and Fantaisistes” (

Dussol 1997) and, eventually, ended up into the “Salon des Artistes indépendants bordelais” (SAIB).

1.2. An Independent Salon... from Whom?

In 1927, the painter and art critic Jean-Loup Simian, along with Georges de Sonneville and some other painters, like Pierre Molinier (1900–1976) and Jac Belaubre (1906–1993), decided to create the “Société des Artistes indépendants bordelais”: their first exhibition opened its doors on October 20, 1928, at the “Terrasse du jardin public”. Independence was their watchword, claimed as a motto from their first catalogue: “there is no more beautiful word in French than independence. It is a word full of élan, an arabesque of sunshine and youth, an onomatopoeia more than a word.

7According to Georges de Sonneville, the main reason for this initiative was that these artists “were generally refused or misplaced at the ”Amis des Arts“ and at the ”Girondins“ Salons”.

8 Indeed, by targeting the juries and comparing them to some parasites that imprison art, the prefaces of the first SAIB catalogues implicitly referred to the Salon des Amis des Arts, in Bordeaux, and to the Salon des Artistes Français—the official Salon, in Paris: “They [the AIB] think that they have much better things to do, and willingly leave to the Artists of the Official Salons these mockery and other nonsense.”

9 The 1929 preface then explains what these mockery and nonsense are:

They are called, like the Angel of Forfeiture, Legion: editorial boards in magazines, reading committees in theatres, juries in exhibitions. We wanted to banish these parasites from this place. [...] No boundaries were drawn here, no rules were laid down, no semblance of servitude was offered. Life is too vast and creation too manifold for everyone not to have the right to see or celebrate them according to his strength or his law.

10

Finally, the 1930 preface summarizes the ideal of the AIB: “Jury Osmosis—NO. Escape from prison—YES”.

11 The Salon of the AIB would thus have no jury at all and, contrary to the Salon des Amis des Arts, the artists themselves—and not an association of collectors and businessmen—would organize their own exhibition.

The AIB coupled their autonomy with another form of independence, less organizational than artistic. Indeed, they rejected the academicism advocated at the Salon des Amis des Arts and at the SAF. Being in their twenties, the leaders of the AIB claimed their independence in a very disruptive and provocative way. Joining deeds to words, they burned the effigy of a firefighter at the opening of their first exhibition—the firefighter or

pompier symbolizing academic art or

art pompier, pejoratively speaking—and they welcomed the public with an airplane that dropped leaflets and with a jazz band.

12 This stormy demonstration of independence had another purpose, that of attracting an audience of potential collectors who would buy their artworks.

1.3. Creating an Alternative and Local Market

Following Georges de Sonneville’s insights, the annual SAIB was also meant to make up for the lack of economic opportunities, in Bordeaux. Indeed, the AIB “did not always have the means to exhibit in the showcase of the city’s main framers: Imberti, Grézy, Jalby, etc.”

13 As they had no gallery in which they could sell their artworks, they decided to create their own one: the SAIB. From the first exhibition, they launched a two-fold financing scheme. On the one hand, like their “ennemies” of the “Amis des Arts”, the AIB launched a subscription of shares amounting to 10 francs each. The preface of the 1928 catalogue explains this two-fold system, like a carnival stalker calling out to the crowd:

Every man has in his heart a sleeping collector; and all these canvases, hung inside, could enrich your collection, or give rise to one, if you only agree, for ten francs (it is not so ruinous...) to subscribe to a share of our Society. From then on, you will have the chance to win something, and, my goodness, it’s always good to take and then, several times ten francs, it can be of service to us—these were not the times of the disinterested Patrons....

14

As for the Salon des Amis des Arts, the subscription would give the right to participate in a random draw, distributing some exhibited artworks by the core members of the AIB—the “Sociétaires”—in an amount equal to the total sum of the subscriptions.

15 From 1930, the AIB made this trick even more appealing by offering an original engraving by one of its members to each generous donor who would subscribe to a ten franc share—the artist would sign and number the print.

16 On the other hand, and like any other Salon in the 19th and 20th centuries, the exhibited artworks had their sale prices mentioned in the catalogues

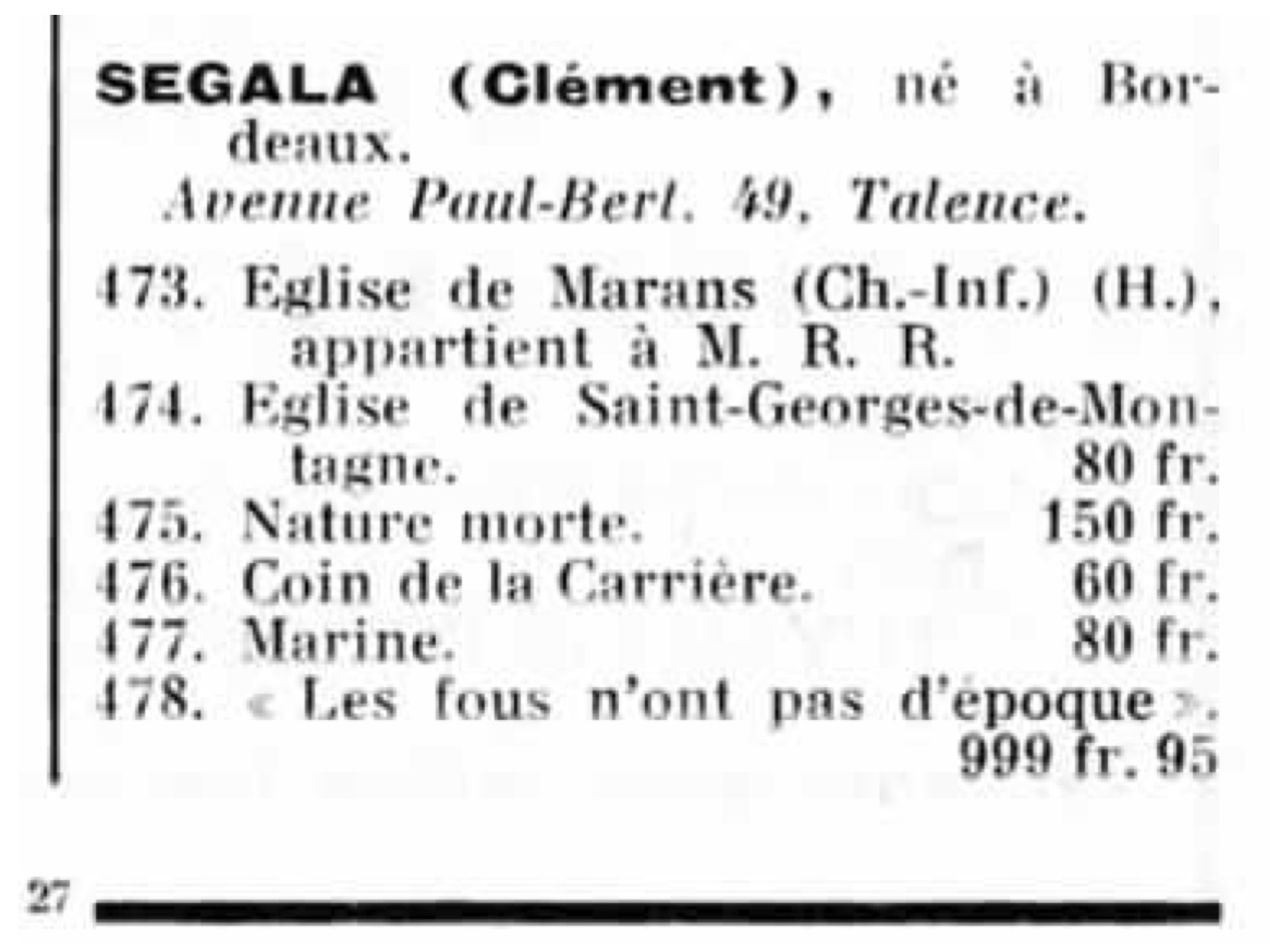

17 and could thus be directly purchased by the visitors of the SAIB. For Instance, in 1930, Clément Ségala proposed an artwork entitled “Les fous n’ont pas d’époque” for 999.95 francs, a commercial wink not to say 1000 francs (

Figure 2)!

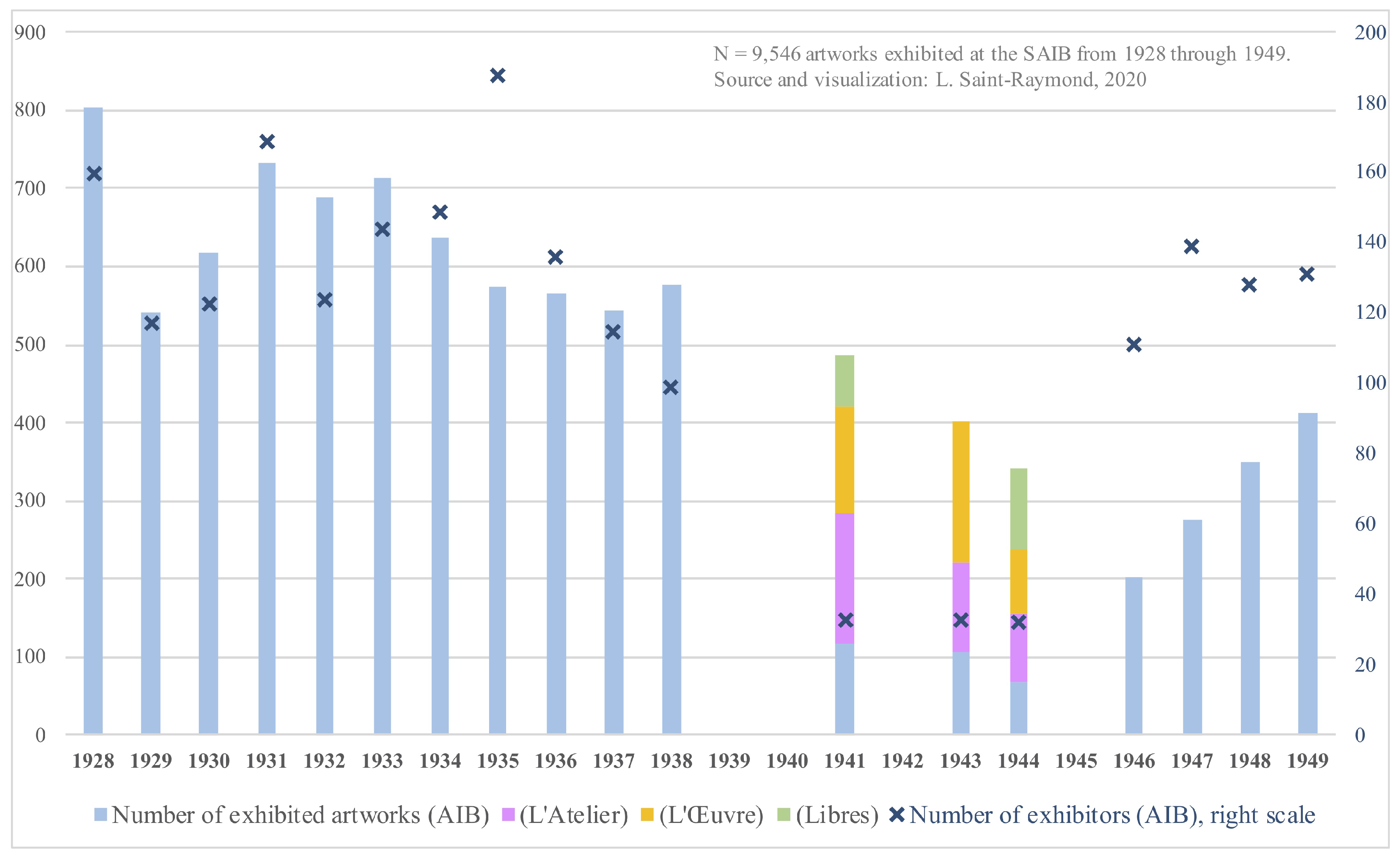

Since its beginning and during the 1930s, the SAIB annually welcomed more than one hundred exhibitors and more than 500 exhibited works (

Figure 3), with two peaks in 1931 (733 artworks) and 1935 (188 exhibitors).

The outbreak of World War II interrupted the SAIB and all the other Salons in Bordeaux; in 1941, three artistics associations—the AIB, l’Atelier and L’Oeuvre, which was founded in 1934—decided to “forget about their rivalries” and to exhibit their works in a common Salon, along with some “Libres” artists, who did not belong to any group. In 1941, 1943 and 1944, the number of AIB exhibitors then dropped to 32, its lowest level ever (

Figure 3). Two years after the Liberation, in 1946, the AIB exhibited again, but only in the Fall 1950–1951 did they organize their own and separate Salon—between 1946 and 1949, they showed their works at the Salon de Mai and the Salon d’Automne, which gathered together other artistic groups in Bordeaux. The artistic landscape of the post-war years was all the more scrambled as the president of the SAIB changed, after the death of the painter Jean-Albert Larocque in 1948: the new one, Jean-Maurice Gay, turned to the youngest artists and created a subgroup, “Sève”, but he also split the AIB into figurative and non-figurative artists, by initiating another group in 1952, Structures.

18 This series of difficulties and splits explains why the following sections will focus on the period 1928–1949.

2. The Parisian Domination, Both Wanted and Endured

The AIB sought to achieve two objectives: first, to become independent of the official Salons in Paris and Bordeaux and, second, to create a local and alternative market for their non-academic artworks. Did their results live up to their expectations? To answer this question, the SAIB catalogues have been transcribed, allowing to take a step back and measure their performances.

2.1. The Detour by Parisian Tutelary Figures

In order to establish their legitimacy, the young “independent” artists from Bordeaux paradoxically took their model from the Salon des indépendants, an exhibition without jury or awards that had been held annually in Paris since 1884 and, above all, from the Salon des surindépendants that opened in Paris in the autumn of 1928, at the same time as the first SAIB. They also relied on the reputation of modern Parisian artists, or those they considered as such. The AIB held Cézanne or Matisse up as paragons of modernity and recognized themselves in fauvism, cubism and expressionism.

19 But more than a simple artistic and symbolic affiliation, they sought to physically attract works of these artists, whom they considered avant-garde, to the walls of their exhibitions. To do so, they used the total sum received from the 10 franc shares, as Georges de Sonneville explained:

What contributed to the creation of the Salon des Indépendants Bordelais? The desire of young painters, not coming from the École des Beaux-Arts, to see the works of these avant-garde Parisian painters, whom they knew only from reproductions and critics. In such a salon, they could finally “invite” those they wished to know.

20

This initiative—bringing modernity to a city steeped in academism—did not date back to 1928: as early as 1919, Georges de Sonneville himself had organized, in Bordeaux, an exhibition of “A group of modern painters”, which brought together artists from Paris and Bordeaux, including his friend André Lhote (1885–1962) whom he liked to portrait (

Figure 4).

21 Born in Bordeaux, the latter appeared as a tutelary and avant-garde figure for the artists of the next generation: in 1937, the AIB even asked him to write the preface to a book of poems they had illustrated.

22The same year, in their Salon, the AIB paid tribute to André Lhote by organizing a solo show for his pictures alongside another tutelary figure born in Bordeaux, Albert Marquet (1875–1947). By giving them the recognition they deserved in their hometown, the AIB claimed to catch up with Paris—the Petit Palais had already displayed André Lhote’s artwoks in 1935

23—and they could thus legitimize themselves:

The masters of independent art have received this year in Paris a definitive consecration. Their works, exhibited at the Petit Palais, have revealed to many the richness of a living art, hitherto too scorned

en province. Our Salons, for the past ten years, have accomplished the same mission in our region, since we revealed all these great names of contemporary painting, in Bordeaux. Today, continuing our work, we are proud to present a truly characteristic set of works by André Lhote and Albert Marquet, once scorned by their hometown, which still denies them the place that the world’s greatest museums have long since granted them.

24

The example of André Lhote was characteristic of the “detour” by a guardian figure, who gained recognition in Paris and who helped legitimizing the younger AIB in Bordeaux. Same initiative happened in 1936, when the AIB managed to be “the first ones”

25 to exhibit 20 paintings by Maurice Utrillo (1883–1955), “who himself came to Bordeaux” as reported in the local press.

26. Similarly, in 1937, they dedicated a solo show to the Swiss painter Félix Vallotton (1865–1925) and another one to Othon Friesz (1879–1949), asking the writer and art critic André Salmon (1881–1969) to write a preface.

27 In 1938, they also set up a retrospective for Odilon Redon (1840–1916), a painter born in Bordeaux from an earlier generation than Lhote, Marquet, Utrillo and Friesz.

For the AIB, these solo shows constituted a step further in the “detour” strategy, in order to catch the attention of the audience and legitimize themselves: beforehand, they “just” relied on a symbolical guardianship, by having some big names in their honorary committee, like the socialite painter Jacques-Emile Blanche (1861–1942) and the poet and critic Max Jacob (1876–1944)

28 and also by asking similar celebrities to preface their exhibition catalogues. For instance, they reproduced the letters that the painters Fernand Léger (1881–1955) and Louise Hervieu (1878–1954) sent them

29 and three main art critics of the 1930s accepted to write prefaces—Raymond Cogniat (1896–1977), Jacques de Laprade (1903–1984) and Jean Cassou (1897–1986).

30However, the detour by tutelary figures of the Parisian artistic scene was a double-edged sword strategy: if it could legitimize the action of the AIBs, it also placed them in a risky position, both symbolically and economically.

2.2. The Gateway to Symbolic Domination?

By inviting celebrities from the Parisian art world, the AIB certainly contributed to giving greater prestige to their exhibitions. Nevertheless, a closer reading of their writings might have somewhat poisoned their gift. Indeed, the tone used by these Parisian celebrities was often paternalistic or openly condescending. At best, they wanted the AIB to be truly free—implying that they were not yet independent, or not completely. For example, in 1932, Fernand Léger encouraged visitors and AIB to be brave, since “to ’enter the dance’, to be able to appreciate or create, YOU MUST BE FREE.”

31 Similarly, in 1933, Louise Hervieu wished “all the best for you and your comrades who have youth and talent and godparents of every distinction”.

32While the famous Parisian painters remained benevolent towards their young comrades from Bordeaux, the art critics took a more ambiguous stance. Indeed, they assumed that

la province was lagging behind Paris and that it was up to Parisians—i.e., to them—to help

la province appreciate artistic modernity—the latter coming from Paris and ensuring French genius. The preface by Raymond Cogniat summarized these double standards. First, he give all his support to the initiative of the AIB:

There is a lot of talk about decentralization. We will not have done anything when we’ve been content to send out more or less sensational exhibitions from Paris, without knowing what echoes they will arouse. The movement has to start from

la province. It is from fervent circles such as the

Artistes Indépendants de Bordeaux that we must wait for effective action, for they alone can undertake the daily work of persuasion likely to get the ideas we hold dear accepted.

33

However, in the following sentences, Cogniat denied the AIB their full ability to achieve this goal:

La province—by what miracle—lives in a strange artistic isolation. One admires all the more deeply the young people who dare to make the effort to get out of it and who, with little means but with their strong will, achieve excellent results. In Paris, caught up in our daily tasks, neither we nor the others make the effort to encourage them, all the effort they deserve. And yet it is a double duty to help them...

34

Similarly, in 1936, Jean Cassou wrote that only Paris had been able to conquer “the truth of modern art”, which is “one of the most beautiful creations of the French genius” and “one of the comforting proofs of the vitality of our country”. According to him, it was thus necessary “to invite

la province to this conquest”, “to incline

la province to recognize these testimonies of the French intellectual audacity”.

35 Jacques de Laprade, for his part, set Paris even more against

la province, which was maybe more instinctive, but lagging behind in terms of artistic modernity:

[...] at a time when the École de Paris no longer surprises us, a new interest is awakening in the artists who inhabit it. We want painters who are less distracted, more instinctive, closer to their deepest lives: these are provincial virtues. Perhaps the fruit of the necessary revolutions of these last thirty years will be gathered in

la province.

36

If, behind their compliments, the art critics were relatively harsh and condescending towards the AIB, the latter themselves contributed to forging the conditions of Parisian domination, being both the wound and the knife. Indeed, they used very reverential formulas to introduce Parisian celebrities in their catalogues. For instance, they presented Raymond Cogniat’s introductory word by saying that “Mister Raymond Cogniat, art critic for the journals

Beaux-Arts,

Les Nouvelles Littéraires and

L’Art Vivant, was kind enough to write this preface.”

37 Similarly, they were very grateful that “Mister Jean Cassou was kind enough to write the preface” of the 9th SAIB

38 and, in 1938, that “the AIB benefit from the precious support of MM. G. Besson, Cassou, Ch. Fegdal, R. Cogniat, P. du Colombier, Ch. Kunstler et E. d’Ors.”

39 But more importantly, the AIB boasted about organizing “the most important event of living art in

la province” (

Figure 5).

This expression automatically lowered the SAIB to a subordinate position, since la province was itself a rather pejorative formula. If the AIBs really wanted to brag without hurting themselves symbolically, they should have written “the most important event of living art in the South of France” or “the most important event of living art in France”. By saying that they belong to la province, they were implicitly considering themselves as a satellite, circling around Paris without ever being able to reach it.

2.3. An Economic Domination by Parisian Artists and Their Galleries

Dominated symbolically, willingly and unwillingly, the AIB were also dominated economically. Indeed, by inviting some Parisian guardian figures at the SAIB, they left the door open for many other Parisian artists, who succeeded much better than the artists from Bordeaux and

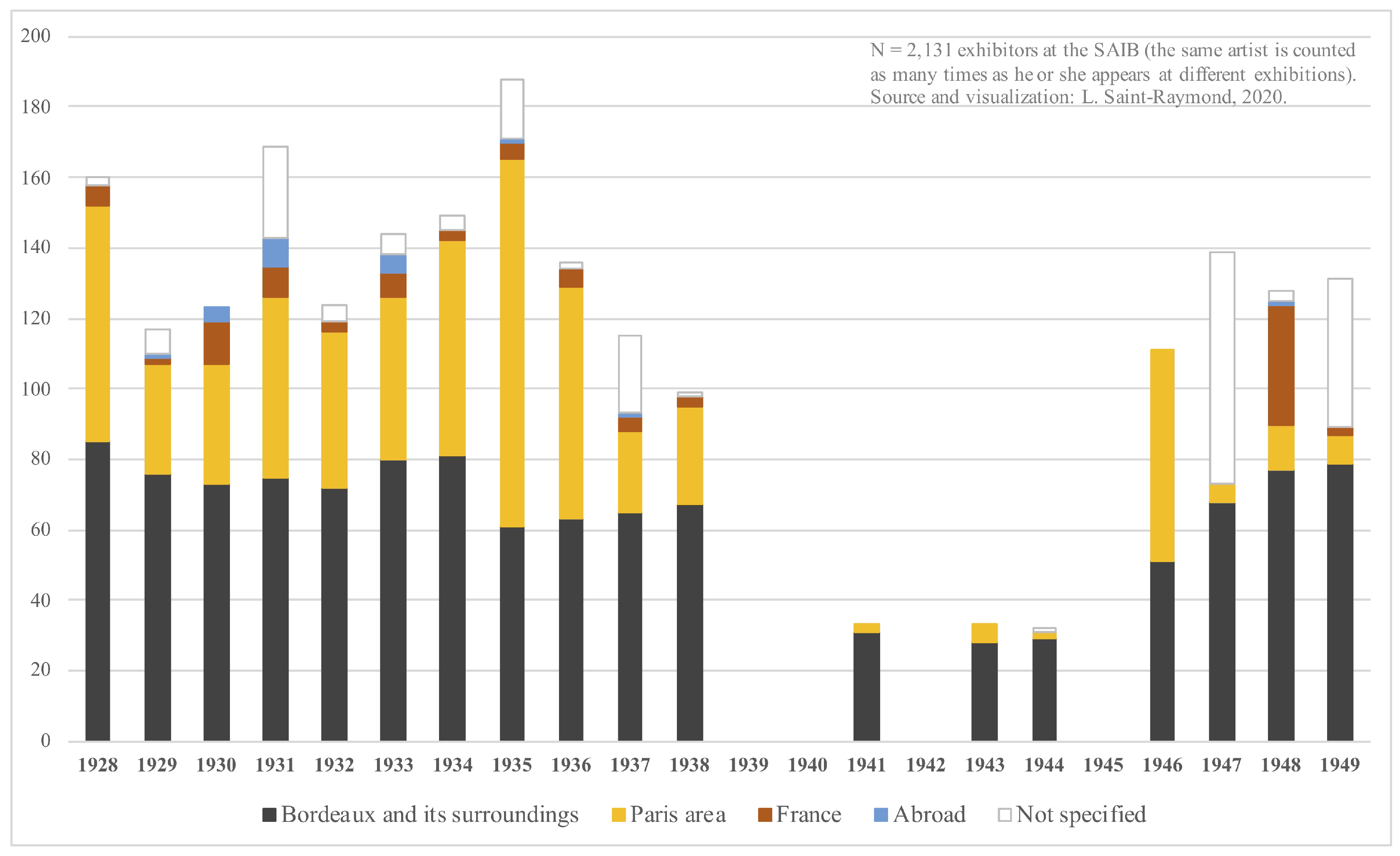

la Gironde did. From 1928 to 1938, between a quarter and a third of the exhibitors gave an address in Paris—even 60 % in 1935 (

Figure 6). These Parisians exhibited relatively fewer works than artists from Bordeaux, since they were the authors of 16% of the works shown at the SAIB at the same period.

This Parisian wave can be explained by a genuine transport improvement: in 1928, it took 9 h and 40 min to go from Paris to Bordeaux by train. This travel time decreased by 3 h in 1930, then by an additional hour in 1934, until it reached 5 h and 50 min.

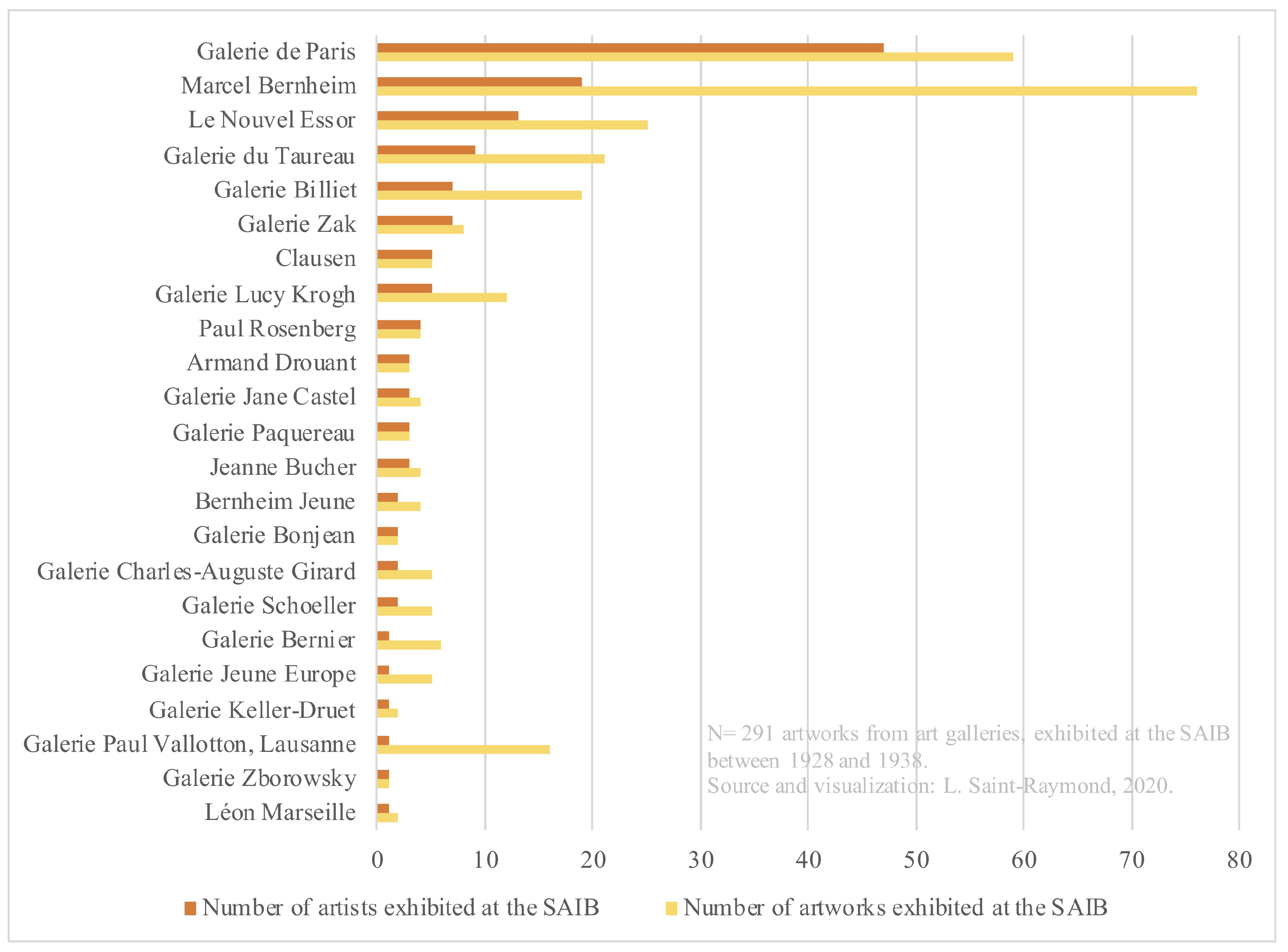

40 This progress in transport facilitated access to a very practical outlet for Parisian artists, and above all for art dealers, who could then be affected by economic difficulties, following the 1929 crisis. Until 1938, 22 Parisian dealers and one Swiss-Paul Vallotton, in Lausanne-sent to Bordeaux some artworks from their gallery, to be exhibited at the SAIB (

Figure 7).

These dealers sent a total 291 artworks to the SAIB at this period, starting in 1928 by the galerie du Taureau, located 52, rue d’Assas in Paris. Little is known about this gallery, who did not resist the crisis—it was registered in 1928, for one year only, in the

Bottin du commerce.

41 The reason why this gallery was the very first one to present the artworks of some artists at the first SAIB—mostly Spanish—is that the owner already knew Georges de Sonneville and had given him a solo show in 1926.

42 In 1929, the galerie du Taureau disappeared, while three main Parisian dealers came to the SAIB—Armand Drouant, Bernheim Jeune and Marcel Bernheim. The latter’s gallery was the only one to appear at the third SAIB. In 1931, Marcel Bernheim was joined by Léonce Rosenberg—the owner of the gallery “Le Nouvel Essor”—by Jeanne Bucher and the Billiet gallery, then, in 1932, by Charles-Auguste Girard and Jane Castel. The year 1933 was quiet—only two works, by Pierre Bonnard and Maurice de Vlaminck, came from a Parisian gallery, that of Bernheim Jeune. In 1934, however, seven Parisian galleries presented a total of 32 paintings at the SAIB, mainly by artists of the École de Paris.

A deeper Parisian wave affected the AIBs in 1935, with the arrival of Paul de Montaignac, the owner of the “Galerie de Paris”, located in the very chic 8th arrondissement at 17 avenue Victor-Emmanuel III. This young Parisian dealer, then 26 years old, had started his activity the previous year and he aimed at “promoting new trends in French painting”, in particular a group of young artists he had called “Jeune France”.

43 After promoting this group in Brussels in 1934,

44 Paul de Montaignac did the same in Bordeaux, in 1935, by exhibiting “a selection of the most important young people who today give painting its new character, both sober and passionate”

45 next to some of the great names of the École de Paris. Moreover, he made the Bordeaux exhibition an official tribune, becoming “General Delegate of the AIB for Paris and Abroad”—a function he kept until 1937. The local press pointed out in 1936 that the AIB “entrusted Mr Paul de Montaignac with the task of bringing together the works of some of the great masters of contemporary painting.”

46 The prominent place of Paul de Montaignac appeared visually in the catalogues of 1935, 1936 and 1937, since the advertising inserts of the “Galerie de Paris” occupied a full page, contrary to the other sponsors (

Figure 8).

Literally and, somehow, ironically, the “Galerie de Paris” thus helped “independent” artists bringing modernity to Bordeaux! Commercial “colonization” thus joins symbolic domination, both of which being wanted and suffered. The economic performances of Bordeaux artists added to this mixed picture, as the following section shows.

3. A Failed Attempt at Decentralization?

Although the AIB wanted to undertake an “artistic decentralization”,

47 their ambition ended in failure overall, except for the small core group of founding members. This section analyses the contours of this mixed assessment and identifies some of the reasons for this, mainly the lack of stylistic coherence between exhibitors and the absence of a truly “local” art market.

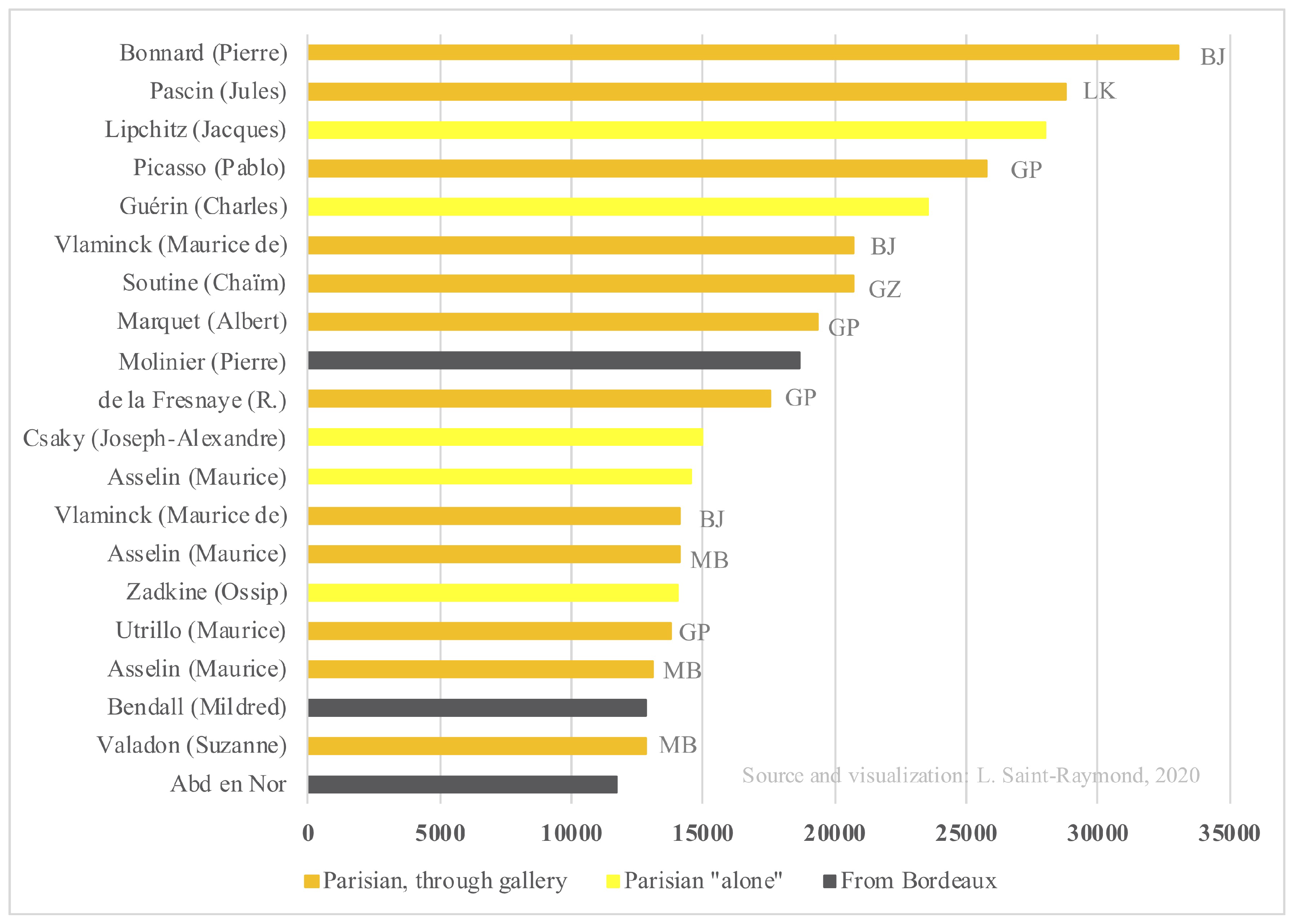

3.1. The Winners and Losers of the Saib: Paris vs. Bordeaux?

If Parisian artists massively occupied the SAIB between 1928 and 1938, it seems that the prices they displayed significantly exceeded those of artists from Bordeaux. Of the twenty works with the highest selling price mentioned in the catalogue (

Figure 9), seventeen were created by artists living in Paris and only three by artists from Bordeaux—Pierre Molinier, Mildred Bendall and Abd en Nor.

History does not tell us whether these works were finally purchased or not. Nevertheless, the same artists who obtained the best prices on the Paris art market in the 1930s

48 were also those who occupied the top of the ranking in the AIB exhibitions, mainly the painters of the École de Paris such as Maurice Asselin (1882–1947), Jules Pascin (1885–1930), Chaïm Soutine (1893–1943), the sculptor Jacques Lipchitz (1891–1973), Nabis (with Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947)), but also the cubist works—those of the painters Roger de La Fresnaye (1885–1925) and Maurice de Vlaminck (1876–1958) and of the sculptors Joseph Csaky (1888–1971) and Ossip Zadkine (1890–1967)—without forgetting Pablo Picasso (1881–1973).

49 Again, the role of art galleries was crucial: of the 17 Parisian works with the highest selling price, 12 were presented by art dealers.

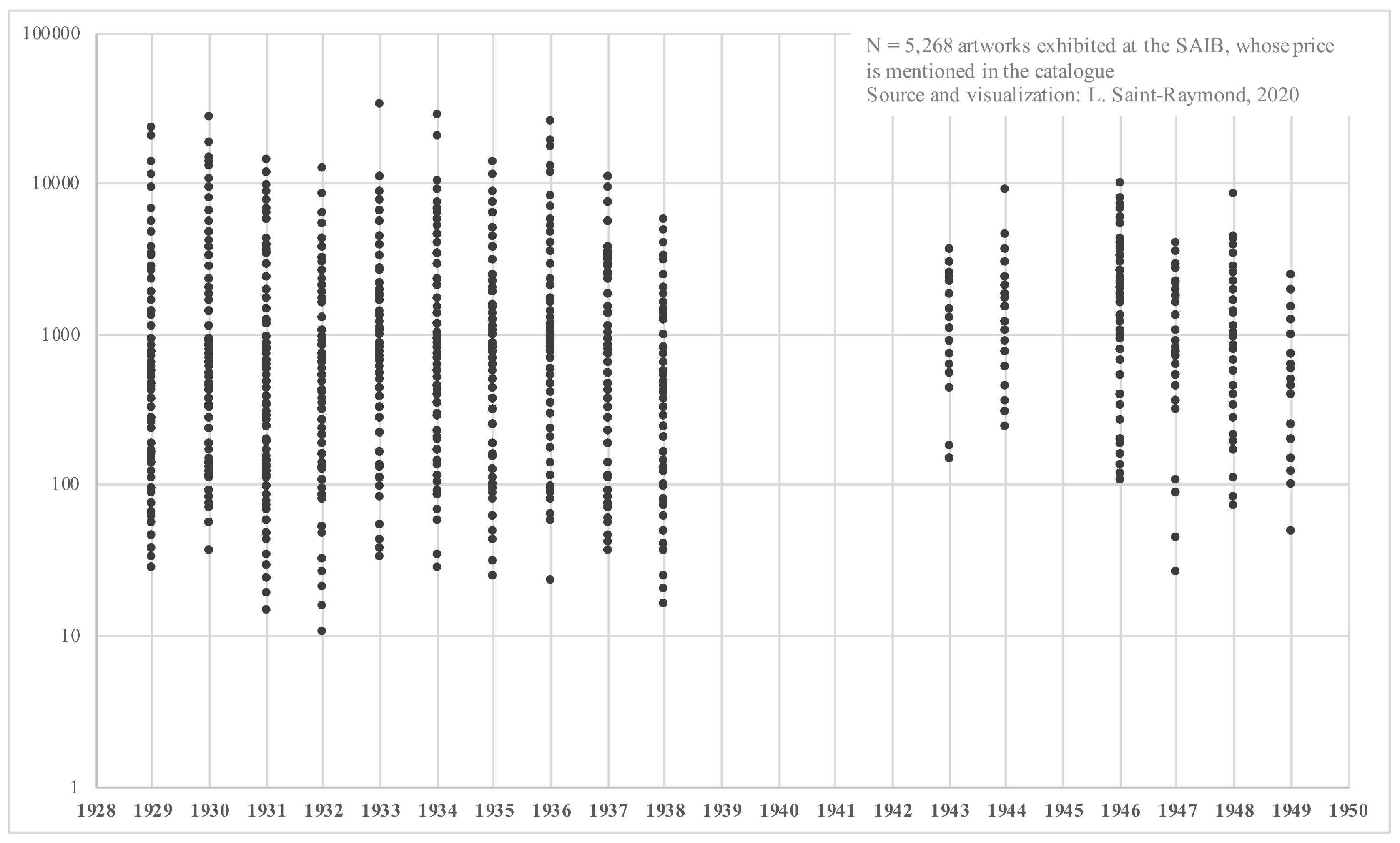

The top of this ranking, however, constitutes only a tiny part of the works offered for sale. Between 1928 and 1949, the SAIB catalogues listed the prices of 5268 works, with a high internal variability (

Figure 10). For example, in 1936, visitors could choose to pay 22,000 (current) francs for a portrait of a woman, by Picasso, or 50 francs for a “Etude de bourg”, by Eugène Danguy, an artist living in Bordeaux.

In order to analyze all of these 5268 prices, and to determine whether artists from Bordeaux performed less well than artists from Paris, it is necessary to use another technique, that of hedonic regression (

Table A1). Without going into technical details,

50 its purpose is to describe how an “explained variable”—here the selling price, in constant 1928 francs—varies according to different “explanatory variables”, and to make comparisons “all other things being equal”, pretending that all the observed characteristics are unchanged, except for the explanatory variable in question. If the explanatory variable has an effect on the explained variable (i.e., when three or two asterisks appear next to the coefficient), then the explanatory variable is said to be “significant”—the sign of the coefficient gives the direction of the correlation between the explanatory and the explained variables—otherwise these two variables are independent. For more rigor in the regressions, it is possible to add a “fixed effect”, i.e., to perform this regression technique by separating various entities, or groups: here, the regressions were also split year by year.

The results of the two hedonic regressions run on the 5268 prices (

Table A1) confirm what had been predicted for the top of the ranking: giving an address in Paris significantly increases the selling price, all other things being equal, while Bordeaux artists conversely experienced a discount of the same selling price. This added value, given by the Parisian aura was only valid for “real” Parisians. Indeed, when an AIB living in Bordeaux moved to Paris, his or her selling price decreased instead of increasing (

Table A2): of the thirteen geographical “defectors”, only three women artists increased their average selling price while living in Paris—Yvonne Préveraud de Sonneville, Marie-Madeleine Machet and Janette Schoeller. However, the two hedonic regressions show that not all AIB were in the same situation of inferiority: women artists were even more devalued and, on the contrary, sculptors, the “Sociétaires”—that is, the AIB who took an active part in the organization of the SAIB and their financing—and the “regulars”—which we have arbitrarily defined as artists who had exhibited in at least seven SAIB—had a much higher selling price than the other exhibitors, all other things being equal (

Table A1). To sum up, the economic performances of Parisians far outstripped that of the AIB from Bordeaux, except for a small number of them—the most invested ones. We can therefore conclude that this attempt at artistic decentralization was a semi-failure.

3.2. A Lack of Identity and Stylistic Consistency

It is difficult to explain the reasons for this assessment by saying that the artworks created by the artists from Bordeaux were of poorer “quality” than the works of the Parisians or of the “regulars” or “Sociétaires”. indeed, the SAIB catalogues reproduced very few artworks and it is almost impossible to find them—the catalogue giving only a vague title, without any dimensions. Nevertheless, one can easily assume that the large number of works exhibited annually—more than 500 (

Figure 3)—could “drown out” the individual works and lead to a certain lack of stylistic coherence. Both a “regular” and a “Sociétaire” of the AIB, Georges de Sonneville made the same remark, in 1922, against the Salon des Amis des Arts, which presented many more works than the Terrasse du Jardin Public could show:

500 paintings are hung at the Amis des Arts, when the room only offers space for 300. Why—since the exhibition lasts two months—not exhibit the paintings twice? A first series in February, a second in March. Such a measure would be to the enormous benefit of the presentation of the paintings and of the income from the admissions; the visitors would be obliged to come back a second time.

51

This “quantity effect” was compounded by the absence of a clear stylistic line. At no time did the “independent” artists of Bordeaux define the extent to which their art was modern and avant-garde—the art critics were also unable to explain why they were artistically independent. No preface played the role of a manifesto, independence being then only an empty shell. From the first exhibition of the AIB, the local press judged that the AIB were “followers”, marked by “the influence that the Matisse, the Dufy, the Derain, the Marie Laurencin, the Dunoyer de Segonzac, the Utrillo, etc., have had on real young people”.

52 If we reduce the focal length to the most faithful “regulars”, who exhibited their works in more than ten SAIB (

Figure 11), a great diversity also seems to appear.

At first sight, there is nothing to group together Jac Belaubre’s Fauvist-inspired works, Jean-Maurice Gay’s Cubist period in the 1930s, Georges de Sonneville’s portraits and genre scenes (

Figure 12), Mildred Bendall’s flower paintings (

Figure 13) or Edmond Boissonnet’s realistic scenes, apart from the fact that these artists lived in Bordeaux or in the Gironde.

As a consequence, the AIB could not constitute a unified avant-garde, stylistically speaking—the first attempt in that sense only took place in the 1950s, when Jean-Maurice Gay tried to unify a younger generation of AIB artists in the subgroups “Sève” and “Structures”, under the common denominator of abstraction.

53 3.3. Was There a Real “Market” for Contemporary Art in Bordeaux?

In the absence of available archives, it is impossible to know how many artworks were actually sold during the SAIB. However, hedonic regressions help us to understand how crucial galleries were to sustain selling prices (

Table A1). All other things being equal, the selling price of a work was all the more important as a dealer acted as an intermediary between the artist and the potential purchaser. However, in the 1920s and 1930s, and contrary to Paris, Bordeaux had no “modern” art gallery specialized in living artists. In 1928, there was only one art dealer in Bordeaux, A.-R. Balades, and their number increased to five between 1933 and 1936, but these dealers were not focusing on contemporary art.

54 Vincent Imberti, for instance, was initially a framer who was also selling engravings, prints and Old paintings.

55 A. Grézy, the only dealer advertised in the SAIB catalogues, mentioned that he was specialized in the “supply for painters and applied work” and the packaging, framing and re-covering of paintings (

Figure 8). The auction market was not very open to contemporary art in Bordeaux and could not be an alternative to the absence of art galleries.

56 It was not until 1947, with the bookstore-gallery L’Ami des lettres, directed by Madeleine Duverger and focused on contemporary art, that living artists were able to exhibit their works collectively—soon joined, in 1960, by Henriette Bounin’s Galerie du Fleuve.

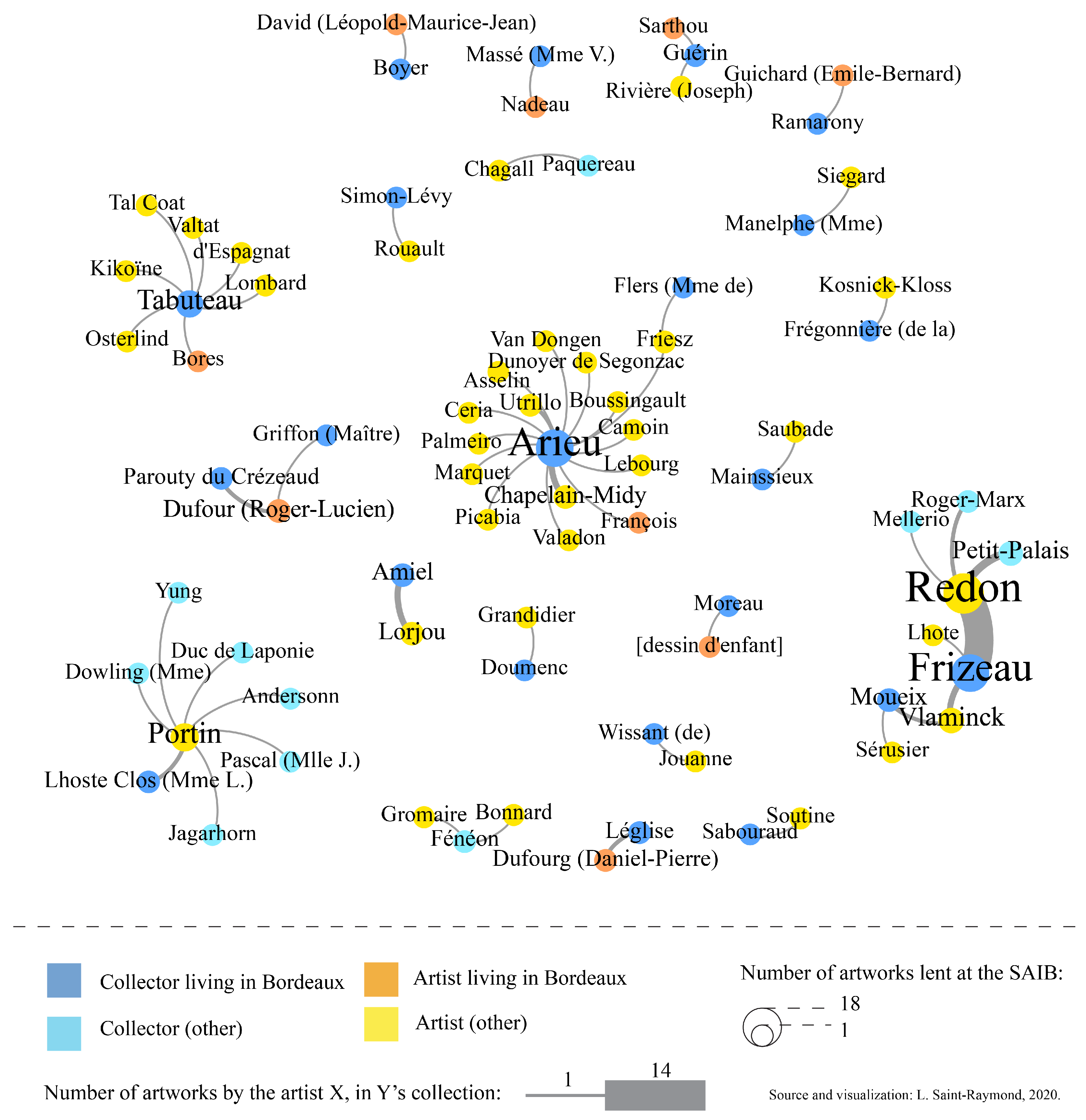

57While there was a desperate need for active galleries to build a local contemporary art market in Bordeaux, demand was also very sluggish. The SAIB catalogues mentioned very few collectors who loaned their works for these exhibitions, whose names were not anonymous and who lived in Bordeaux (

Figure 14). The situation depicted by Georges de Sonneville for the 1910s could therefore be applied to the inter-war period:

One can hardly speak of the “dominant taste for art” in the Bordeaux society of the “Belle Epoque”. They went to music. Painting, to tell the truth, did not interest them. If there were collectors, it was more often out of vanity than out of taste, especially old paintings. With regard to the artists of their time, they were still demanding “well-finished”, well “licked” paintings, where the “brushstrokes” did not appear. They did not buy much. Most often they were content to win a painting at the tombola where the Amis des Arts scattered about fifty paintings each year.

58

Unfortunately, the few Bordeaux collectors mentioned in the SAIB catalogues did not much favour the contemporary art of their city (

Figure 14). Antoine Arieu, for example, possessed artworks from the École de Paris, Mrs L. Lhoste Clos owned two works by the Swede Charles Portin (1889–1980), who lived in Paris at the time. As for Georges Frizeau (1870–1938)—then, at his death, his son Jean—known for his openness to modern art,

59 he only lent to the SAIB artworks by consecrated artists—Odilon Redon, Maurice de Vlaminck and André Lhote—without supporting any “young” AIB from Bordeaux. The Musée des Beaux-Arts did not play an active role either: apart from a purchase in 1928 for a work by Georges de Sonneville exhibited at the SAIB (

Figure 12), it was not until 1950 that new acquisitions were found to enrich the city’s public collections.

60In these conditions, the independent artists from Bordeaux could have a hard time devoting themselves to their art, while remaining in a local market:

Among painters, there are no such thing as amateurs vs. professionals. Only those who live exclusively from the sale of their paintings without any additional resources—annuities, professorship, administrative function—vs. the others. The former are extremely rare among the 30,000 painters who claim to live in France.

61

The AIB whose biographies are known today lived on their pensions or on a sideline professional activity. For example, Mildred Bendall was born into the merchant bourgeoisie and Jean-Maurice Gay was a dental surgeon.

62 4. Conclusions

On the whole, the attempt at artistic decentralization and the creation of a local market ended in semi-failure. As a matter of fact, between 1928 and 1949, the art market in Bordeaux remained “mired” in “provincialism”. This term does not mean that the artistic field was a “desert”, to paraphrase Jean François (

Gravier 1947), as the dynamism of the AIB exhibitions in Bordeaux testified to the vitality of the local scene. “Provincialism”, as a market phenomenon, was rather characterized by the domination of Parisian artists to the detriment of artists from Bordeaux, both in prices—selling prices were much higher for Parisian artists—and in the tastes of local collectors. In other words, “provincialism” was the symptom of an imbalance of recognition, to the detriment of regional artists and in favor of those defended by Parisian galleries. After the disappearance of the official Salon as the main “prescriber”, the network of galleries thus became a determining factor for artistic consecration: many Parisian art dealers were specialized in modern art and willing to support young artists—contrary to Bordeaux, at least until the 1950s (

Dussol and Saumier 2009).

Conversely, the issue of provincialism should be tackled through the other end of the lens. Did local artists only sell their works during the SAIBs or in within that same local environment? Their exportability can be observed through the careers of the artists from Bordeaux who decided to make a career in Paris and, eventually, through their choice to settle in the capital or not. Surprisingly, the detour to Paris did not seem to be an asset once back on the local scene: when an AIB decided to move back to Bordeaux, his or her selling price decreased instead of increasing. Was this a local peculiarity? Did provincialism, as a market phenomenon, also happen to other local initiatives taking place outside Paris, during the same period as the AIB? Few similar projects came into being in France in the 1920s and 1930s. Nevertheless, it is possible to make a comparison with the exhibitions of another group of “local” artists, which were held annually in a southern French city competing with Bordeaux: although they began in 1906, the exhibitions of the “Artistes méridionaux” (literally, the southern artists) took place in Toulouse throughout the inter-war period and allow a comparison with the AIB. This research project on “Artistes méridionaux” exhibitions is currently being published with Hadrien Viraben.

Finally, this failed attempt at decentralization has to be put in parallel with the characteristics of the artworks during that period: was the provincialism, as a market domination, correlated with some “artistic provincialism”? In other words, was there a radical difference between the artworks by Parisian artists and those by local artists, that would justify such price gaps? When exhibiting in both Paris and Bordeaux, did these artists decide to show different types of artworks in each city? While it is difficult—even impossible and dangerous—to define and therefore give an objective measure of the “quality” of an artwork, it is still necessary to retrace the works that were exhibited at the SAIB. This is why the database that served as the basis for this paper—the exhaustive transcription of all the SAIB catalogues between 1928 and 1949—will soon be put online, hosted by the École normale supérieure, with the possibility of enriching it with external information, in particular with the works preserved today.