Abstract

The aim of this article is to characterise the rise of the Portuguese contemporary art market since the beginning of the 21st century, within the broader context of the global contemporary art market. Against a theoretical backdrop of the globalisation of markets for contemporary art and the concept of the periphery, I will analyse Lisbon’s art scene as a local phenomenon that is looking for an international recognition. In doing so, I am focusing on two working hypotheses. The first relates to the efforts made by the gallery sector to raise the international profile of its artists, giving them sought-after widespread recognition, which encompasses a historical perspective on the situation and a prominent role for the younger generation of gallerists. The second intends to observe the role played by private collectors and their contributions towards boosting the art scene, assembling their contemporary art collections and making them available to the public. I conclude that this has led to an upsurge in the contemporary art market in connection with the growing number of validating structures, museums, and art centres, due mainly to the fact that the shortcomings of the public sector are being made up for by private initiatives.

1. Introduction

The magazine Forbes Portugal named Maria Helena Vieira da Silva (1908–1992), Paula Rego (b. 1935) and Joana Vasconcelos (b. 1971) as the Portuguese artists who achieved the highest value at auction in 2019. Vieira da Silva’s work was sold for €38 million; Paula Rego’s for €11.6 million and Joana Vasconcelos’s for €3 million (Garcia 2019, pp. 20–21). All of them are women, and their work is notable for its creativity. They represent different generations: Vieira da Silva started exhibiting in 1930, Paula Rego in 1950, and Joana Vasconcelos from the mid-1990s. Vieira da Silva and Paula Rego are both painters. The former belonged to the Second School of Paris and concentrated on issues relating to space, architecture and geometry in painting. Both have a museum devoted to their works (Fundação Arpad-Szenes-Vieira da Silva in Lisbon; Casa das Histórias Paula Rego in Cascais). Paula Rego produces inventive paintings that feature narrative figuration and draw upon popular tales; she lives in London and was an integral member of the London Group. Joana Vasconcelos is based in Lisbon and explores everyday objects that she builds on a large scale, while delving into issues of identity and gender.

These artists have all achieved international recognition and exerted an influence on their peers, exhibiting in important museums such as Tate Britain, the Pompidou Centre, the Palace of Versailles and the Palazzo Grassi in Venice. Their work forms part of public and private relevant collections (e.g., Tate Modern, Centre Pompidou, MoMA, François Pinault, António Cachola, José Berardo). The combination of these factors is reflected in the price that they command on the market.

I will go on to discuss how artists achieve international recognition, which is a matter both of the structures of acquisition and the means of artistic legitimation in relation to the creation of art value and recognition. French sociologist Raymonde Moulin pointed out that cultural promotion is determined by the interconnection between an international network of art galleries and an international network of cultural institutions (Moulin 2003, p. 47); in other words, the meeting point between market activity and the impact of museums and art centres. On the other hand, the French sociologist Alain Quemin added that “galleries, art fairs, and auctions all play a major role in the creation of art value […] as they tend to have a greater influence on the global legitimation process of art and artists” (Quemin 2020, pp. 339–40). Despite the relevance of this statement, I underline Moulin’ perspective as I believe that this is not yet the case for Portuguese galleries for contemporary art, as they do not have such a global influence. Their presence in the most prominent international art fairs, like Art Basel, are still scarce.1

Vieira da Silva relied on the mediation of gallerists and dealers to promote her work internationally. From the 1930s onwards she worked with French galleries—the Galerie Jeanne Bucher2 and later the Galerie Pierre. For her part, Paula Rego has been working with Marlborough Fine Arts (London) since the late 1980s, recently has changed to Victoria Miro (Selvin 2020), and with Galeria 111 (Lisbon), among others. Joana Vasconcelos has also worked with galleries such as Galerie Nathalie Obadia (Paris) and Galeria Horrach Moya (Palma de Mallorca, Spain), although she also sells her works directly from her studio (Fernandes and Afonso 2014).

Does Portugal have official frameworks and commercial structures that can help its artists to gain international recognition? If we refer to the ArtReview Power 100, a ranking of the most influential people in art published since 2002, it is soon apparent that we cannot tell much about the impact of Portuguese players, namely artists, at an international level, because none have made the list.3 The same goes for the Kunstkompass lists, as a tool for assessing the resonance of artists in the international sphere. Going back over the last twenty years, for example, we see a certain stability in the ranking of artists who have maintained dominant positions, particularly from the US and Germany (e.g., Gerard Richter b. 1932, Bruce Nauman b. 1941, George Baselitz b. 1938, Rosemarie Trockel b. 1952, Cindy Sherman b. 1954).4 As such, these indicators are not useful for my purpose, as they only reinforce the idea that contemporary Portuguese artists enjoy little in the way of international recognition and are somewhat peripheral.

Academic literature on this subject that has been internationally published does not use the Portuguese situation as an example or case study. Exceptionally, James Goodwin’s book The International Art Markets: The Essential Guide for Collectors and Investors (Magalhães 2008) has a chapter by João Magalhães entitled Portugal. In this chapter Magalhães, who has been the representative of Sotheby’s in Portugal since 2016, characterised the art market as a product of a peripheral region, where artistic taste is traditionally conservative and nationalistic, and which tends to absorb international trends belatedly. He considers the decorative arts to be the driving force behind Portuguese naturalistic painting from the end of the 19th century and argues that the country does not have the power to emulate the international elites, neither is it peripheral enough to be distinctive in its own right, and thus attractive (Magalhães 2008, pp. 253, 257, 261, 263). If we take that perspective on board, it would seem that artists only receive international recognition on an occasional basis. It also means that Vieira da Silva, Paula Rego and Joana Vasconcelos are exceptions among Portuguese artists in having acquired international renown.

The idea of the belated absorption of international trends and the issue of a more conservative taste as mentioned in the piece by João Magalhães is nothing new in academic literature. This perspective gives continuity to the dominant narrative, whereby the periphery is a derivation and subordination of the canon produced at the artistic centres, in a clear hierarchy of cultural values.5 This idea of the periphery can be seen as a line of argument aimed at justifying the scanty recognition that Portuguese artists have achieved. From an empirical perspective, this idea is systematically deployed by those active within the Portuguese art world. However, the approach that I will adopt in this article is one that looks at the Portuguese art market in its manifold peripheral and conjunctural characteristics, within a global context, with a view to understanding the role of agents in promoting it. I will analyse its specific features, rather than regarding it as a mere replication of hierarchical models. Moreover, as this is not a linear or evolutionary phenomenon, I intend to observe the efforts that have been made towards internationalisation, mainly by the primary market sector and some private collectors whose collections have contributed to the opening of museums and art centres. Such efforts are significant because the public sector, i.e., the state, has been continually scaling back investment in supporting structures aimed at promoting contemporary art and acquiring contemporary artworks in order to update museum collections.6 In other words, the promotion of contemporary art has mainly been the work of private bodies.

Internationally, publications relating to the art market have been prolific, especially since 2000, when such topics began to be studied at universities. Various disciplines have dealt with this field (sociology, economics, finance, art history) with the aim of understanding the development of the art market, its scale and the effects of economic globalisation, the agents and the relations of power (art dealers and galleries, the auction sector), the growth of private museums and the predominant role of the collector. Scholars have also examined the importance of official artistic institutions and the increasing number of large-scale exhibitions (e.g., biennials). Authors who have made significant contributions over the last five years include Velthuis and Curioni (2015), Zarobell (2017), Hulst (2017), Adam (2017), Heinich (2017), and Robertson [2011] (2018). They discuss such themes and they expand their investigations to places outside the dominant axes of Europe and North America, where economic growth occurred alongside the rise in the art market.

India, China, Brazil, Latin America, South Africa, Nigeria, Congo, and other countries and regions that the literature includes in the Global South have been receiving increased and long-deserved attention from researchers.7 The Global South designation is complex because it doesn’t refer to a purely geographical domain, but rather a cultural and political reality in which the societies or countries that make it up have tended to be marginalised within the dominant narratives. Another source of complexity is that fact that whereas globalisation sees the expansion of opportunities, allowing the voices of those countries or regions to be heard, the opposite also happens and persists. In any case, while such studies represent opportunities to discuss the Global South, they also help to envision the situation that does not actually occur there. This context could be a framework to understand the Portuguese art market, which geographically and economically I could add to the Global South, with the attendant vulnerabilities. Historically speaking, however the imperialistic role that it played and the ensuing colonial issues put it in an ambiguous position. There is greater consensus for its categorisation as being on the periphery. Academic literature has been silent when it comes to dealing with the development of the art market in Portugal, due to it being an area of recent research in academia and undoubtedly also due to the local and peripheral dimension to its market, which does not have a high business volume or a large number of players. Of the most recent works, I have drawn from Mercados da Arte by Afonso and Fernandes (2019), where the researchers made an effort to consider distinctive Portuguese features within the context of the history and international flux of the market.

The main aim of this article is to identify the mechanisms by which the primary art market in Portugal has been activated since the beginning of the 21st century, through a theoretical discussion of peripheral markets and the increasing interest in the Global South. This should engender a deeper understanding of whether the Portuguese art market is mature enough to act as a launching pad for the international recognition of Portuguese artists. With that in mind, I want to contribute to the discussion on art markets globally, from a peripheral perspective. I intend to observe the consolidation of the artistic structures that have helped to make a change to the outlook of low international recognition for Portuguese artists. To achieve this goal, methodologically I will examine academic literature, press articles that I will quote throughout this article, and compare their analyses with data,8 archive resources, interviews with gallery owners, and the author’s empirical observation on the field in order to identify the main structures of the market and their performance in boosting art and Portuguese artists on a global platform.

2. The Periphery Is Beautiful: The Rise of the Portuguese Contemporary Art Market in the 21st Century. Findings

The periphery is beautiful: the rise of the Portuguese contemporary art market in the 21st century is a paraphrase of the title of Ernst Schumacher’s book Small is Beautiful. In his influential book, published in 1973, the German economist addressed issues relating to the conventional perspective on the path of globalisation, how things look through the lens of large-scale corporations, and the importance of the economic sustainability from the viewpoint of citizens. Here, I have adapted the idea of ‘small is beautiful’ to the periphery, an approach that allows us to be aware of the main trends of the globalisation while also focusing our attention on a more proportionate market structure. Portugal is a small country, the westernmost country in Europe, located on the Iberian Peninsula. Its economy is very much dependent on international economic cycles, and recently has been gradually recovering from the 2008 global financial crisis, which affected all sectors, including the art market.9

Portugal has played a low-key role in the international visual arts scene. Concentrated in Lisbon, and to a lesser extent Porto, the most important northern city, the art market has a predominantly local scope, a domestic dimension (Magalhães 2008, p. 263; Afonso and Fernandes 2019, p. 197), although the way in which it functions is undergoing significant change, towards greater professionalism, while its structures have been moving towards internationalisation, especially since the turn of the millennium. This change is coupled with a growing interest in contemporary art, with elite society appreciating, collecting and displaying it to the public, as we will see. I will observe and characterise the efforts made to encourage the rise of the contemporary art market through the gallery sector, including a historical perspective, as a working hypothesis towards internationalisation, in the next section and its subsections.

2.1. The Contemporary Art Gallery Sector: Towards Internationalisation

Lisbon rising: a global art hub emerges from crisis (Choy 2017) is a very enthusiastic article published by Wallpaper that testifies to the growing interest that the city and the local art scene elicited in the media and among art agents. From that period onward, Lisbon began attracting international attention for its art, artists and art structures. The opening of ARCOlisbon, a boutique art fair organised by IFEMA as an extension of the Madrid’s art fair in 2016, was instrumental in this shift, as it led to greater visibility and harnessed potential for the internationalisation of Portuguese artists and contemporary art galleries (Choy 2017).

Going back a little, the new millennium ushered in an auspicious environment for visual arts and to art market in Lisbon, with growth in the number of art galleries and exhibition spaces for contemporary art. If we look at the data in Table 1, Art Galleries and Other Places for Temporary Exhibitions, we can observe the strong development of the sector. The number of spaces doubles over the two decades, despite a period of stagnation around the time of the financial crisis (2008–2012), and it has continued to grow up until the present.

Table 1.

Art galleries and other venues for temporary exhibitions.

This growth is the result of the optimistic environment around the new millennium. I can pinpoint cultural factors that contributed towards this enthusiasm, such as the opening of museums and art centres in the nineties. One of the most relevant institutions established during this period was Fundação Caixa Geral de Depósitos—Culturgest. Created by the bank controlled by the Portuguese government, this foundation is responsible for the contemporary art collection that has been assembled since 1983. Under Fernando Calhau, a conceptual artist, the collection was structured during the 1990s with the following criteria: Portuguese contemporary art from 1960 onwards and artworks with a “museum dimension”, meaning relevant artworks, also in the artists’ careers (Calhau 1993; Sardo 2009, p. 7). Later, the scope of the collection was opened up to international artists, particularly from Portuguese-speaking countries, through the choices of a new curator, António Pinto Ribeiro (Sardo 2009, pp. 12–13). The collection launches held at the new Culturgest galleries in Lisbon since 1993 help to legitimise contemporary artistic creation. Another institution of note is the Centro Cultural de Belém, which also opened in 1993, with a generous exhibition space in a great geographic location in Lisbon. Initially, these galleries held temporary exhibitions covering a wide range of topics (from the Baroque to contemporary photography). From 2007, due to the José Berardo’s agreement with Portuguese government, it has hosted the Berardo international modern and contemporary art collection, covered in further detail here (Duarte 2016, p. 245). Lisbon also saw the renovation of the Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea—Museu do Chiado, which reopened in 1994 after a long period of restoration due to a serious fire in in the local area in 1988. Perhaps the absence of a permanent exhibition contributed to the lack of strong representation for Portugal’s artists. The Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Fundação de Serralves opened in Porto at the end of the decade, in 1999. This opening was probably the most significant event for contemporary art in Portugal, due to the museum’s mission to assemble an international contemporary art collection based on the ‘Circa 68’ concept, i.e., international art from this period onwards, and its agenda of pursuing contemporary values, all within a modern building designed by the architect Siza Vieira (Todolí and Fernandes 1999).10 Built with its intended purpose in mind, the structure creates a dynamic atmosphere for contemporary art and promoting the works of the artists. Moreover, such art centres have been helping to boost the primary art market ever since then as they seek to update their collections through new acquisitions.

This cultural framework helps us to understand the growing number of art galleries and exhibition spaces observed in Table 1, but I believe that the internationalisation process systematically demonstrated by the gallery sector since this period has only reinforced the trend. Internationalisation means economic, political and cultural exchange between countries. Its importance lies with reputation and aesthetic quality. Art galleries with an international scope have a competitive advantage in that they are able to extend their work to different geographical regions, exporting their artists and artistic trends into major art collections. They also have the opportunity to put their choices up against those of their peers, and to participate in international scenes, which leads to visibility and artistic recognition.

The internationalisation of contemporary art galleries in Lisbon has been an ongoing goal since the professionalisation of the sector in the 1960s. Agents have developed various strategies in order to achieve it, the most relevant being participation in international art fairs. Despite the financial effort fairs involve, it is here that galleries have the opportunity to present their artists’ works to museums, collectors and international curators, opening their careers up to internationalisation and allowing them to find attractive alternatives to the local market in Lisbon.

To participate in international fairs, some galleries periodically requested financial support from the state (the Culture Secretariat, later the Institute of Arts) and foundations with a cultural profile based in Portugal, such as the Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian and the Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento.11 This strategy was not always successful because support was provided cyclically and not on a regular basis.12 Trends in terms of programmes and artist representation, including the showing of international artists alongside their Portuguese counterparts, have also bolstered internationalisation.13

It is at the intersection of such elements, namely programming that includes international artists and their continued presence at international fairs, that I will develop this subsection. I selected a set of galleries that, at the turn of the millennium, were conducting their activities with this goal of internationalisation in mind. The choice focuses on established and leading galleries in the Portuguese art market: Pedro Cera, Filomena Soares and Cristina Guerra, due to having the experience essential to harnessing the art fair market. Furthermore, they represent more than twenty artists each, most of them foreign and well established.14 I will also look at a generation of galleries that have been active more recently because this allows me to make forward-looking observations. This is the case with Bruno Múrias, Madragoa, and Francisco Fino. This choice has been made in qualitative terms, with the galleries analysed in chronological order, based on when they were established. It focuses on the galleries’ mission, path, aesthetic trends and participation in international art fairs. The narrative is based on bibliography, exhibition catalogues, articles published in the press, interviews with gallery owners,15 and, in a few cases, unpublished documentation accessed in archives (Quadrum, Módulo-Centro Difusor de Arte).

The first is Pedro Cera, whose gallery opened in 1998 in Lisbon (Figure 1).16 He developed a taste for contemporary art and used to buy works by Portuguese artists. After the gallery opened, he began collecting in earnest, extending the spectrum to mostly international artists. Although he prefers not to identify exogenous reasons for the opening of the gallery, but merely reasons of personal interest and taste, the inaugural ‘Circa 68’ exhibition at the Serralves Foundation in Porto in 1999 proved a particular source of inspiration, as it looked at the work done by Italian gallery owner Gian Enzo Sperone to promote Italian arte povera.17

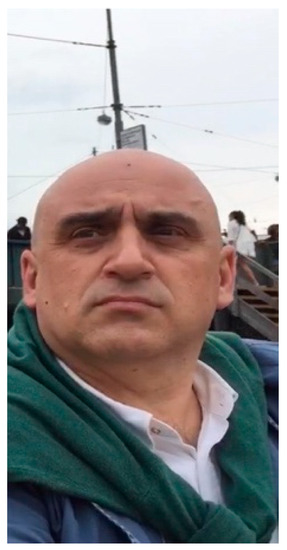

Figure 1.

Pedro Cera. 2018. © Santiago Cera

From the very outset, Pedro Cera defined internationalisation as fundamental to his work as a gallerist. In his own words, ‘it would be very annoying if our performance landscape were confined to Portugal’.18 As he saw it, it did not make sense to impose geographic limitations, as ideas or objects can be found at any latitude. The gallery began to promote emerging and mid-career Portuguese artists. It has increasingly included established international artists from Latin America and North America (Melo 2001). Its current focus is to promote artists who work with a range of media and question those media (David Claerbout b. 1969, Ana Manso b. 1984) and reflect on the fragility of the materials (Gilberto Zorio b. 1944), conceptual issues, the influence of contexts in the meaning of the works (Adam Pendleton b. 1984), and appropriation, displacement and irony (Miguel Branco b. 1963). The focus on internationalisation can also be seen from its persistent participation in art fairs. There is no doubt that as a result of this path, the gallery’s clients are mostly private and institutional collectors from Europe and America.19 In 1999, Cera attended Artissima, then ARCOmadrid (Melo 2001). Indeed, he never missed the latter. He was also a familiar face at Art Basel Miami Beach, Art Basel (the world’s leading art fair) and Art Basel Hong Kong. Art Basel Miami Beach may have led to Cera’s attendance at Art Basel, as he has regularly attended this event since 2007 (with exceptional interruptions in 2009, 2010, and 2012).20

The second example is the Galeria Filomena Soares, which opened in 1999. It is managed by the couple Filomena Soares and Manuel Santos. Filomena gained experience at Galeria Cesar (1997–2000), in partnership with Cristina Guerra, also a gallery owner (Melo 2001). Discreet in nature and without training in the field of visual arts, the couple developed their enterprise by focusing on internationalisation and went on to become one of the most prestigious contemporary Lisbon art galleries to operate on a global stage (Herstatt 2008, p. 111). With a set of institutional art collectors and an influence on the Portuguese secondary art market, its recognition arose from the strategy that the gallery adopted, which was to promote renowned artists, especially Europeans, on the international art circuit, participating in large-scale exhibitions and key museums.21 The renowned and established artists Pilar Albarracín (b. 1968), Letícia Ramos (b. 1976), Rui Chafes (b. 1966), Shirin Neshat (b. 1957), Imi Knoebel (b. 1940), Dan Grahan (b. 1942), Helena Almeida (1934–2018), and Günther Förg (b. 1952) have all been represented by Filomena Soares. The gallery works in the fields of representation, identity, gender, social criticism, conceptual questioning and reflection on materials. They also make use of curatorship, inviting leading international curators for exhibitions and thereby helping to reinforce the symbolic value of the gallery’s selection of artists. They have been an abiding presence at art fairs, especially in the years following the 2008 financial crisis, when there were around 10 fairs per year—almost one per month.22 Their ubiquity at fairs on the Iberian Peninsula (ARCOmadrid) and in Central Europe suggests that this is its most loyal market, but the gallery has been exploring new markets in South America and the Middle East, and participates regularly at ZONAMACO fairs, ARTBO, SP-Arte, ArtRio, and Art Dubai.

The Cristina Guerra Contemporary Art is the final example of a leading art gallery to be examined here. It was founded in 2001.23 After managing Galeria Cesar with Filomena Soares, Guerra moved on to her own gallery project, where she also pursued internationalism and devised a strategy for promoting Portuguese artists alongside international artists. As she recalls, “I wanted to internationalise from the very beginning of my project. There are certain things that are just not done. I got Lawrence Weiner’s phone number and called him. I introduced myself and told him I would love to work with him” (Tavares 2010). And she did get him. Lawrence Weiner (b. 1942) had been a pioneering artist in the field of conceptual art since the 1960s and was one of the artists exhibited by the gallery from its initial phase onwards (Figure 2).

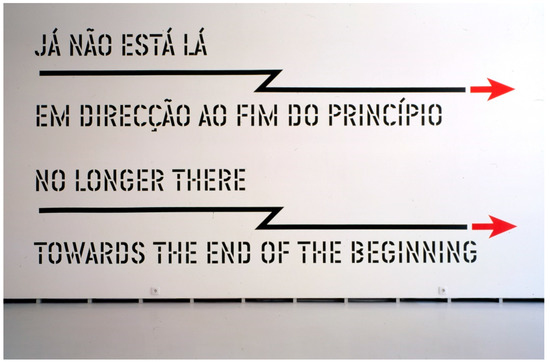

Figure 2.

Cristina Guerra Contemporary Art. “Lawrence Weiner. Towards the End of the Beginning”, 2002. © Cristina Guerra Contemporary Art.

In addition to promoting dialogue, she endeavoured to attract an international clientele who were less knowledgeable about the art scene in Portugal, besides institutional Portuguese clientele and private collectors.24 Meanwhile, she turned to international curators with the purpose of promoting artists she represented abroad. In artistic terms, she focus towards a conceptual and minimal style of art due to her aesthetic affinities.25 John Baldessari (1931–2020), Julião Sarmento (b. 1948), Ângela Ferreira (b. 1958), Juan Araujo (b. 1971), Erwin Wurm (b. 1954), João Maria Gusmão + Pedro Paiva (b. 1979; b. 1977), Matt Mullican (b. 1951), Yonamine (b. 1975), Sabine Hornig (b. 1964), Jonathan Monk (b. 1969), and Robert Barry (b. 1936) have all been represented by the gallery, thus underlining its international scope and extending its conceptual matrix to other contemporary art narratives such as post-colonial issues, interculturality, representation and medium. In terms of involvement with art fairs, Cristina Guerra has focused on the Central European and North American market, making repeated appearances at Art Basel since 2004, and Art Basel Miami Beach since 2002. Closer to home, she has participated in ARCOmadrid since 2002 and ARCOlisboa since 2016, the fair’s opening year.

Examining these galleries allows me to tease out some common threads. Firstly, they are primarily committed to mid-career artists who are conversant with the language of contemporary art language and whom the market recognises as producing quality work because their pieces form part of the collections of major public institutions and private collections, and because they feature large-scale exhibitions (Saraiva 2017).26 Secondly, established galleries are more cautious about participating in art fairs; they do so progressively and use the weakest economic cycles to explore new markets. After the 2008 economic crisis, galleries systematically invested in Latin America and the Middle East. Although central Europe and North America continue to be the predominant markets, with a continuous presence in ARCOmadrid by most of the galleries under observation, and they exhibit a typical fair footprint of an average of five attendances per year.27

2.1.1. Driving Internationalisation: The Youngest Galleries in the Market

Bruno Múrias belongs to a generation of young galleries that represents a breath of fresh air within the contemporary art market in Portugal, especially in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis.28 Having built up experience at Módulo—Centro Difusor de Arte (1998–2003) and at Galeria Filomena Soares (2003–2014), Bruno Múrias joined Nuno Centeno’s project in 2014. This became known as Galeria Múrias Centeno (Sobral 2016). After four years, in 2018, the partners went their separate ways. Múrias remained in Lisbon, registering the gallery in his own name (Figure 3). Centeno did likewise in Porto, setting up the Galeria Nuno Centeno in a new, ambitious space, and taking with him some promising artists.29 In terms of his gallery’s programme, Múrias prefers to invest in young artists (Bruno Cidra b. 1982) and mid-career artists who have gained some recognition in the art world and work with a variety of supports and themes related to contemporary art: the question of self-referentiality and the city (Rui Calçada Bastos b. 1971), contemporary photography (António Júlio Duarte b. 1965), the relationship between sound and space (Ricardo Jacinto b. 1975), common objects and their poetics (Pablo Accinelli b. 1983, Nicolás Robbio b. 1975), or modernist architecture (Marcelo Cidade b. 1979), to name but a few examples. Both Portuguese and international artists are promoted here. During his time working alongside Centeno, Múrias attended the Independent Brussels art fair for two consecutive years (in 2016 and 2017), as well as Liste Art fair Basel (2016 and 2017), ZONAMACO and Frieze London (2015 and 2016), and Frieze New York (2016 and 2017). He participated in ARCOmadrid every year between 2014 and 2019, and was at ARCOlisbon every year except 2017. The years 2016 and 2017 were particularly fair-heavy, with five and six fairs respectively, which reduced to three in 2018 and 2019, when Múrias embarked on his solo project.30

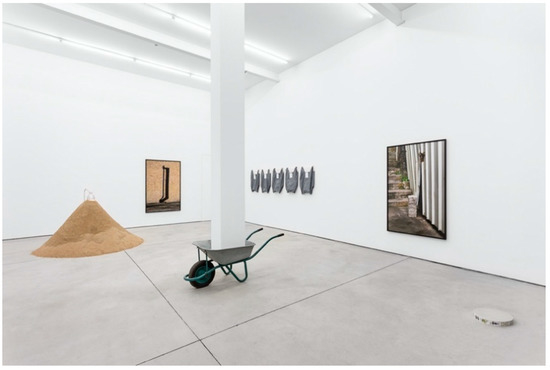

Figure 3.

Distorção Inerente. First exhibition at Bruno Múrias, 2018. © Bruno Múrias.

Madragoa opened in 2016 in a small space and owes its name to the area in Lisbon where it is located. It was founded by Gonçalo Jesus, a Portuguese biologist and researcher who has long had an interest in contemporary art, and the Italian Matteo Consonni, who has a background in art history and experience of working in galleries. Consonni was director of the Galleria Franco Noero (2010–2016) in Turin for five years (Figure 4).31

Figure 4.

Madragoa, Matteo Consonni and Gonçalo Jesus, 2016. © Madragoa.

He was drawn to Lisbon as he saw a city with lots of potential to increase its artistic institutions and saw an opportunity in the low number of galleries, the quality of the local art scene, and the openness to internationalisation there. Recently, the gallery has sought to promote young artists born since 1980, as the gallery owners consider this generation to harbour particular potential. However, they are flexible when it comes to their programme: the gallery has already shown the work of the artist Enzo Cucchi (b. 1949), a historical representative of the Italian transavantgarde (Van Eeckhoutte 2020). It opened with a solo exhibition by the Italian artist Renato Leotta (b. 1982). Madragoa also works with artists from Portugal (Luís Lázaro Matos b. 1987, Sara Chan Yan b. 1982), Central and South America (Andrián Balseca b. 1989, Rodrigo Hernández b. 1983), Poland (Joanna Piotrowsca b. 1985), Spain (Belén Uriel b. 1974) and South Africa (Buhlebezwe Siwani b. 1987). Consonni says that, in general, its artists reveal conceptual concerns and a certain poetic attitude (Anonymous 2019b). Madragoa has a clearly international focus, as can be seen from its programme and participation in international art fairs. The gallerists have had a presence at Artíssima since they opened in 2016, as well as at Art Basel, in the Statements section dedicated to emerging art (2018), Art Basel Miami Beach (2018, 2019), Art-O-Rama Marseille, and Liste Art Fair, among others (Salema 2018). Madragoa participated in ten fairs in 2017 and in eight in the following two years.32

The final example in this examination of the youngest galleries section is the Galeria Francisco Fino (Figure 5). It opened in 2017 in Marvila, Lisbon. Francisco Fino adapted a former olive oil and wine warehouse into a modern gallery in eastern Lisbon, a neighbourhood particularly popular for contemporary art projects (the Bruno Múrias gallery is nearby). When he returned to Lisbon from New York,33 the economic situation was not particularly conducive to investing in his own gallery (Orientre 2018). His strategy was to work independently with artists from 2012, as Francisco Fino Art Projects. This phase was important, as he built up experience and developed a close relationship with artists with whom he would later work in his gallery. In 2017 he opened his gallery with a collective exhibition entitled Morphogenesis, a concept related to the development of a biological organism, and which could also be applied in a metaphorical sense to the opening of the gallery itself. The curator was João Laia, then an independent curator. The opening took place within days of the opening of ARCOlisboa, then in its second year, so the new gallery was able to feature in the Opening section of that year’s fair. The artists he represents produce work of an experimental nature. They are emerging and mid-career artists born in the 1980s or mid–late-1970s. Their use of media varies: some work with film, photography, obsolete technologies or installation to create fictional and imaginative narratives (Tris Vonna-Mitchell b. 1982, Gabriel Abrantes b. 1984, Mariana Silva b. 1983). They address ecology and our relationship with the environment (Adrien Missika b. 1981); they reflect on abstraction, memory, repetition and painting as a specific quality (Marta Soares b. 1973, Karlos Gil b. 1984); or they may deal with post-colonial, gender-related issues, drawing upon archives and political matters (Vasco Araújo b. 1975, Carla Filipe b. 1973). The gallery’s internationalisation is a priority, and Francisco Fino’s strategy has been to participate in art fairs, averaging about four per year. He has opted for Artíssima on a regular basis (2017, 2019) and has also made forays into Art Brussels (2018), Sp-Arte (2017) and MIART (2019). The Iberian Peninsula is a key market for Fino: he regularly attends ARCOmadrid (2018, 2019) and ARCOlisboa (2017, 2019).

Figure 5.

Galeria Francisco Fino, “Serendipity or the Art of Reading the Signs”, 2019. © Galeria Francisco Fino.

I have pinpointed these three young galleries as they appear to be looking to invest in internationalisation, and they participate mainly in alternative art fairs.34 This strategy shows that they are looking for a niche, and internationalisation is assumed to be a primary aim. Their programmes reveal an effort to represent promising young and mid-career international and Portuguese artists based on recognition gained within the art world, through prizes won, artistic residencies, and acquisitions for collections. Looking ahead, the resolute, risk-accepting attitude of such galleries, driven by an optimistic outlook for Lisbon’s artistic scene, coupled with international attention, leads me to believe that the internationalisation of these galleries is in a phase of consolidation, and that peripheries such as Lisbon may also represent an opportunity to provide something that can complement large-scale structures, within a global context.

Furthermore, as I discuss this atmosphere of revitalisation in the Lisbon art scene, it is worth mentioning that some international galleries have opened branches of their galleries, a development that has added to the growing internationalisation and rejuvenation of the local art scene. Such galleries bring with them artists that face up against the Portuguese, as well as international clients and—potentially—new audiences. Monitor, an international gallery from Rome, opened a branch in Lisbon in 2017, after an experience in New York; Maisterravalbuena, an international gallery based in Madrid, opened a space in Alvalade. Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, a historical French gallery that has represented Vieira da Silva, opened a space in the Chiado neighbourhood in 2018, and a major international gallery of Brazilian art, Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel, opened an office in the Chiado, also in 2018.

2.1.2. Driving Internationalisation: Pioneers

‘Wishing to introduce contemporary avant-garde trends in Portugal, I hereby announce the artists that I have selected for the Basel Art’78 International Fair: Lourdes Castro, Ana Vieira, Jorge Pinheiro, Victor Fortes and João Moniz. (...) Your technical and financial support will contribute to the dissemination of the work of visual artists who work in our country, and who aspire to their dissemination abroad, which is so difficult to achieve nowadays’ (D’Agro 1978). Dulce D’Agro wrote this letter to the Gulbenkian Foundation to request financial support for her to participate in Art Basel and justifies it by stressing the importance of publicising the work of visual artists on an international stage. And D’Agro did indeed receive support almost every year.35

In this subsection, I will underline the influential role that three art galleries played in promoting their artists internationally through their ongoing presence at art fairs, over a period prior to globalisation, and also look back at their programmes. They are Quadrum—Galeria de Arte, Módulo—Centro Difusor de Arte, and Cómicos—Luís Serpa Projetos. This effort was recognised by their peers and artists, and helped to distinguish them as pioneering galleries that would endeavour to raise the international profile of their artists and seek to defend artistic and cultural values, as well as encouraging other galleries to follow a similar path.

The painter Dulce D’Agro (1915–2011) opened Quadrum in 1973. Quadrum was an avant-garde art gallery located at Coruchéus in the Alvalade district of Lisbon. Active between 1973 and 1995, Quadrum distinguished itself as a forerunner in the dissemination of the avant-garde and the discovery of new artists.36 The political context of the 1970s was complex due to the Carnation Revolution (1974), which put an end to the long dictatorship. Economically, Portugal went through a recession with consequences for the art market, which had been growing since the mid-1960s. Given those difficulties, Quadrum developed a somewhat risky strategy, dedicating itself to conceptual and experimental art, anticipating future tastes among society and spreading symbolic values (Bystryn 1978, p. 393; Moulin 1997, p. 56). The importance of D’Agro’s work in professionalising artists’ careers, her influence with collectors and gallery owners, who subsequently replicated her strategy and the impact of the gallery’s achievements on Portuguese cultural life throughout the last quarter of the 20th century make Dulce D’Agro an iconic figure in Portuguese culture.

According to archival resources, D’Agro started to participate in art fairs in 1977 at Bologna Arte Fiera, Italy.37 This was an important year for the art fair because of the focus on conceptual art galleries, performance, videotape and photography. As far as we can see, Quadrum’s programme shifted in that direction over the following years as a result. As she started to exhibit modern artists like Victor Vasarely (1906–1997), Karel Appel (1921–2006) and their Portuguese counterparts, D’Agro began increasingly promoting conceptual art, environmental art, body art, installations and performance (Ana Vieira 1940–2016, Alberto Carneiro 1937–2017, Gina Pane 1939–1990, Dany Bloch 1925–1988, Ulrike Rosenbach b. 1943) (Figure 6).

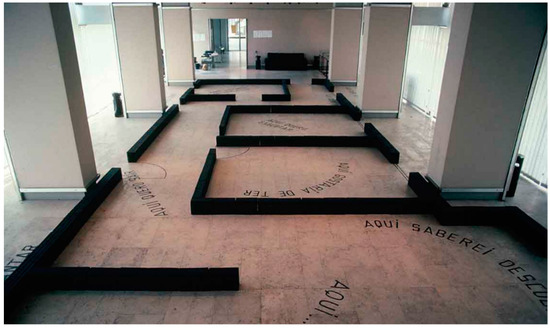

Figure 6.

Galeria Quadrum, “Ana Vieira, Ocultação/Desocultação”, 1978. © Quadrum/EGEAC, Galerias Municipais.

She demonstrated her commitment to the avant-garde with a more radical programme.38 By exhibiting non-sellable art, she was turning towards the international market. She began to put in regular appearances at international art fairs: Art Basel (1978–1978), Arte Fiera Bologna, FIAC (1979), ARCOmadrid (between 1982, its first year, and 1988) and the Los Angeles Art Fair (1988–1990). Quadrum was also a regular participant in Portuguese art fairs with a local focus, such as Forum de Arte Contemporânea (1988–1989), and Marca Madeira (the first such event in Portugal, in 1987).

As a result of this approach, Dulce D’Agro developed a valuable international network—she counted Denise René, Daniel Templon, Juana Mordó and other gallerists among her friends—and was able to exchange works by Portuguese artists with other European galleries, receiving, in turn, pieces by foreign artists to exhibit in her gallery.39 Economically speaking, however, Quadrum was not a successful gallery. She ended up losing her personal fortune, and archived documents often reveal her complaints about low sales.

In 1982 the first criticism relating to Quadrum’s programme appeared in the press. The articles also pointed out the emergence of new art galleries like Diferença as alternatives. I would add Módulo—Centro Difusor de Arte, which was opened in Porto in 1975 with an audacious roster of young Portuguese and foreign artists, and proved a pioneer in promoting photography as part of its relationship with the visual arts. Indeed, it’s very name (‘Centre for the Dissemination of Art’) was a bold statement of intent, even if that option meant economic ruin.40

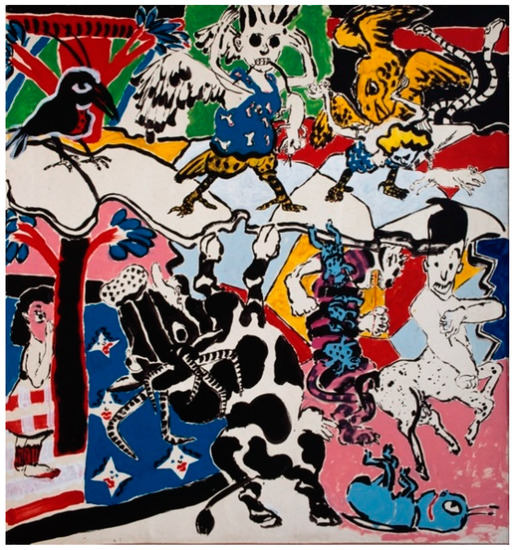

Mário Teixeira da Silva was the Módulo’s promoter. A consummate collector, Teixeira da Silva read Chemical Engineering at the University of Porto, before going on to study Museology and Art History at the Smithsonian Institute, USA, and the Courtauld Institute of Art, London, prior to his gallery project.41 The programme that he devised was a risky and ambitious from a business perspective, as it sought to promote new trends in contemporary art within the conservative city of Porto. His main focus was Portuguese avant-garde artists, contemporary international photographers and paper works by international artists. When he started out in the 70s, Teixeira da Silva selected a set of artists committed to abstract, conceptual and post-conceptual art, land art, photography, art and language, gender issues and new media, such as Robyn Denny (1930–2014), Richard Smith (1931–2016), John Hoyland (1934–2011), Hamish Fulton (b. 1946), Gilbert and George (b. 1943; b. 1942), Michael Biberstein (1948–2013), Roger Raveel (1921–2013) and Jochen Gerz (b. 1949) (Melo 1999, pp. 44–47). He settled upon a clearly international programme, which was overstated by the art critic Nelson Di Maggio, who commented that Módulo was the only space in Lisbon devoted to foreign artists (Maggio 1983). (Teixeira da Silva opened a Lisbon branch in 1979). Over the following decade he changed strategy to focus on Portuguese artists, particularly emergent talent in the field of new figuration (including Ana Vidigal b. 1960, Manuel Rosa b. 1953, Pedro Portugal b. 1963, Pedro Casqueiro b. 1959 and Júlia Ventura b. 1952, who rank among the most stablished Portuguese artists today). In the 90s he returned to his previous plan, mainly promoting international artists of renown, such as David Tremlett (b. 1945), Hanne Darboven (1941–2009), Franz Erhard Walther (b. 1939), Allan McCollum (b. 1944), and emerging artists like Wim Delvoye (b. 1965), Sue Williams (b. 1954), Patrick Corillon (b. 1959), Jack Pierson (b. 1960) and Sylvie Fleury (b. 1961) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Módulo, “Wim Delvoye, Chantier (Installation)”, 1992. © Módulo—Centro Difusor de Arte.

Some of the most interesting photographers worked at Módulo and were a distinctive feature of the gallery from the very beginning, exhibiting documental, conceptual, stage and black-and-white photography (Paulo Nozolino b. 1955, Jorge Molder b. 1947, Paul den Hollander b. 1950, Bernard Faucon b. 1950, Larry Fink b. 1941, Bruce Charlesworth b. 1950, Axel Hütte b. 1951, John Batho b. 1931, and Mário Cravo Neto 1947–2009). Teixeira da Silva was a pioneer in boosting this medium among Portuguese collectors, which extended to institutional collectors and museums.

In addition to this demanding program, Teixeira da Silva began appearing at art fairs from 1977. The first of these was Art Basel, followed by Bologna Art Fair, Cologne Art Fair, Düsseldorf Art Fair, and ARCOmadrid and Arte Lisboa, to which he was a regular visitor (Anonymous 1977a, Anonymous 1977b, Anonymous 1978).

His constant presence at art fairs may be considered to be an internationalising strategy, as it was an opportunity to meet new collectors, new museum directors and new curators, and to have an international audience to validate his choices. As sources testify, the press commented favourably upon his stables of artists, particularly in the 70s and 80s, deeming Teixeira da Silva to be a rigorous and committed gallerist, and a pioneer in his field (Machado 1983; Melo 1986). Teixeira da Silva is still active in the market, regularly participating in art fairs, preferably satellite versions (due to ‘fairtigue’),42 while his gallery currently focuses on emerging, mainly Portuguese artists, although he still pays attention to contemporary photographers and artists from further afield.

The last example of a gallery driving internationalisation that I wish to discuss here is Galeria Cómicos—Espaço Intermédia. Its founder was Luís Serpa (1948–2015), a collector who had studied Drawing and Painting at the School of Fine Arts in Lisbon, with a specialisation in Museology and Design. The gallery opened in 1984 and during the 1980s played a role similar to that of Quadrum during the 70s. It was committed promoting artistic values and focused on the neo-expressionism. The new gallery was borne of the impact of a major exhibition, called After Modernism, coordinated by Luís Serpa, which was held in Lisbon in 1983. This exhibition took the pulse of the postmodern art scene, assessing upcoming trends, the return to painting, the transavantgarde, neo-expressionism and bad painting, and cleared the way for the new generation of artists that emerged.43 The gallery became a figurehead for a new aesthetic trend. Cómicos set out an original, eclectic programme, and in its first two years of activity combined several disciplines, including architecture, music, design and performance. Soon, however, its sole focus was the visual arts (1986). Serpa states that from the very beginning, Cómicos’ aim was raise the international profile of its artists and put an end to geographic borders. The artists and the gallery had a common strategy that would be legitimised by international agents (Serpa 2006). Cómicos presented emerging artists at that time (Pedro Cabrita Reis b. 1956, Cristina Iglesias b. 1956, Juan Muñoz 1953–2001), together with established figures, bringing major experimental artists together within its programme. The gallery became a benchmark establishment, a place that spanned conceptual art (Joseph Kosuth b. 1945), arte povera (Michelangelo Pistoletto b. 1933, Gilberto Zorio b. 1944), land art, walking art (Hamish Fulton b. 1946), gender, issues of representation, photography (Cindy Sherman, Robert Mapplethorpe 1946–1989), experimental theatre, and visual art (Robert Wilson b. 1941). With Serpa’s help, Jorge Molder, Julião Sarmento (b. 1948), Jose Maria Sicilia (b. 1954) and Ferran Garcia Sevilla (b. 1949) achieved international visibility, becoming recognised artists in today’s art world. Serpa himself maintained a regular presence at art fairs in order to better establish his artists’ reputation abroad. He attended ARCOmadrid from 1985 onwards (Melo 1999, p. 52) and explored the market in other parts of the world: Los Angeles, Tokyo, Zurich, London, Chicago and Basel (Melo 1999, p. 56). He was also one of the responsible for the opening of Forum de Arte Contemporânea, the first art fair in Lisbon, in 1988 and 1989, and a founding member of the AGPA, a Portuguese gallery association. This soon made waves in the press. David Joselit (1987) wrote in Art in America that Serpa had probably been ‘the most aggressive art dealer in Lisbon in promoting his artists outside Portugal: the group of artists he represents share some of the techniques and preoccupations of transavantgarde expressionism, making them more immediately accessible to an international audience’. This recognition would be cemented when his gallery was rated one of the 200 best galleries in the world (Daviot 1991).

Despite its success, the gallery changed tack after the first decade: in 1994 Cómicos became the Luís Serpa Gallery, then, two years later, Luís Serpa Projects, reflecting the fact that it was taking on a broader cultural dimension. This change also occurred at a time when a few artists had started running their own careers and working with other galleries (Julião Sarmento,44 Pedro Cabrita Reis). Serpa essentially stopped representing artists after 1994, as they became established; after all, he had no exclusive say in their activities, leaving him free to conduct his own curatorial projects (Melo 2001). The gallery left behind its commercial profile and progressively took on a more cultural one. Serpa is still remembered as the man responsible for amplifying the idea of internationalisation to an unusual level of professionalism in Lisbon and making artists’ work accessible to a wider audience.

The galleries mentioned here were generally present at art fairs from the point at which they were founded, for which they often received funding. However, the internationalisation of Portuguese art was not just a matter of participating in art fairs. This goal was also achieved by systematically including foreign artists alongside those from Portugal in the gallery’s programme from the very outset. That strategy was followed by Quadrum, Módulo, and Cómicos. As those galleries adopted an avant-garde profile, promoting contemporary art, their foreign artists were chosen to fit the strategy. The reputation that these pioneers built for the Portuguese art scene provided a lasting legacy for their peers and for artists.

2.2. Museums and Centres for Contemporary Art: The Role of Collectors

Having analysed the efforts made by galleries, especially since 2000, in this section I will take a closer look at how Portuguese artists can obtain international recognition and what kind of structure can support it. As our second working hypothesis, I will observe the role that private collectors have played in a peripheral context, and determine how they have contributed to the rise of Lisbon’s art market by assembling collections of contemporary art. First, they made these collections available to the public in museums and art centres, increasing the number of public exhibition spaces, and second, they included international artists alongside Portuguese talent, bringing international visibility to artists and to institutions. We will now look at the context in which acquisitive structures are connected with those of legitimation—museums and art centres (Moulin 2003)—and see if this has a bearing on effective internationalisation.

Since the first decade of the 21st century, contemporary art museums in Portugal have seen significant changes due to the accessibility of new facilities to the public. Many of these new spaces have their origins in private collections (Duarte 2016, p. 9). Table 2 summarises this growth and reveals the dynamism of the sector, revealing the rise that has occurred since 2000, with a greater concentration in the city of Lisbon.

Table 2.

The growing number of contemporary art museums and art centres in Portugal in the 21st century.45

From Table 2, I selected two private collectors whose collections gave rise to museums during this period. There is the José Berardo collection, which enabled the opening of the Museu Coleção Berardo de Arte Moderna e Contemporânea in Lisbon in 2007. Although its acquisitions did not boost the Portuguese art market (purchases were predominantly made at auction houses—Sotheby’s and Christie’s—and at international art galleries), this collection served as a sort of model for private collections going public, through political agreements, and acting as a launchpad for museums and art centres. Secondly, there is the Norlinda and José Lima collection, which led to the Centro de Arte Oliva in São João da Madeira, near Porto, in 2013. These two collections are notable for acting as figureheads and due to their international scope, a characteristic that was slow to become embedded in private collecting in Portugal.

Moreover, I will also look at a private collection with corporate tutelage by the Museu de Arte Arquitetura e Tecnologia, open to the public in Lisbon in its own building. Finally, I will briefly touch upon a recent Lisbon project, Rialto6, as it started off as a private collection whose collectors are committed to the Lisbon art scene, and allows to envision the future with new exhibition models.

The Berardo Collection of Modern and Contemporary Art is the most important collection featuring international artists available to the public in Portugal. It was created in 1993 as a private collection intended to fulfil a public function. At that time, the economy was in recession due to the Gulf War, which provided advantageous conditions for those who wanted to acquire artworks in the international market (Melo 1995, p. 35). The man responsible for the initiative was Francisco Capelo, an economist who managed José Berardo’s fortune in the 1990s while working with the millionaire.46 Capelo is the foremost active collector in Portugal and has assembled various art collections in order to establish museums.47 He has stated that he does so for pedagogical reasons—that presenting objects of international quality educates the eye and elevates culture. Although he was not the first collector to buy objects of international quality in Portugal—others had done so before, like Jorge de Brito in the 70s—he was essentially the first to establish a public museum with these pieces. As early as 1993, the year the collection began, press reports stated that Berardo’s collection was a kind of ‘museum that does not exist in Portugal’ (Porfírio 1993).

Capelo used a rational methodology: he started by defining a concept for the collection, set a budget to make it feasible, and from there he researched the best works by the artists that appeared on the market. In addition, he checked the work’s background to guarantee its authenticity and scrutinised condition reports to preclude any damage. This strategy secured him a set of works by various blue-chip artists (Francis Bacon 1909–1992, Gerhard Richter, Pablo Picasso 1881–1973, Sigmar Polke 1941–2010, Jeff Koons b. 1955, Franz Kline 1910–1962, David Hockney b. 1937, Morris Louis 1912–1962, Tom Wesselmann 1931–2004). These trophy pieces were considered to be financial assets in the art market (Afonso and Fernandes 2019, p. 71) and thus aroused international attention.48 This resulted in a panoramic collection that provides an insight into the successive artistic movements over the 20th and 21st centuries. The major pool of artworks included Pop Art (James Rosenquist 1933–2017, Roy Lichtenstein 1923–1997, Andy Wharhol 1928–1987, Robert B. Kitaj 1932–2007), Nouveau Réalisme (Arman 1928–2005, Bernard Rancillac b. 1931), Art & Language, abstraction and the predominance of colour (Josef Alberts 1888–1976, Ad Reinhardt 1913–1967). Going back even further, they took in Art Brut (Jean Dubuffet 1901–1985), the Paris School (Pierre Soulage b. 1919, Henri Michaux 1899–1984), spatialism (Lucio Fontana 1899–1968), and narrative figuration (Francis Gruber 1912–1948). The aim was to bring together a significant group of pieces by artists from the western world—Europe and North America, in order to represent post-World War II artistic production, with all its contradictions and ruptures, testimony to the fragility of the human condition that had emerged from a violent context. Later, after 1997, and thanks to favourable economic conditions, the collection broadened again, with the purpose of addressing two important artistic movements: Abstraction-Création and Surrealism (Salvador Dalí 1904–1989, Joan Miró 1893–1983, Hans Arp 1886–1966, Auguste Herbin 1882–1960). It achieved this with works made around the 1930s, which were a hugely impactful part of the collection. The collection’s chronology currently covers the entire 20th century and even the early decades of the 21st century.

The choice of artists from the foremost figures of the current avant-garde was a strategy that Capelo would continue to pursue, with a major impact on the collection. Capelo once said that a collection is always a collection of artists (Capelo 1996, p. 9). Indeed, there are a few works by each artist, with a clear preference for painting. This is a compendium collection that mainly comprises painting for reasons of taste, but the preference for this technique in the art market should not be overlooked. The collection currently includes a large number of Portuguese artists. Over the period that Capelo was choosing the artists (until 1999), he opted to include only three Portuguese artists—Vieira da Silva, Paula Rego and Julião Sarmento. He argued that at that time only these artists had an international trajectory that was similar to the others exhibited in the collection. Since 1997, the collection has been public, first at the Sintra Museu de Arte Moderna, and then ten years later, in 2007, in the main galleries of the Centro Cultural de Belém, Lisbon, under a protocol signed by the Ministry of Culture and the collector.49 The collection remains private property, but is accessible to the public, in a space managed and maintained by public funds.50 This model, based on a rigid and controversial protocol (Duarte 2016, pp. 249–52), was eventually adapted by other private collectors, who likewise made their collections available in public spaces.

José Lima is another prominent collector within Portugal’s current arts scene. He began collecting systematically from the 1980s onwards. As an entrepreneur in the footwear sector in São João da Madeira, near Porto, Lima accumulated a large collection of modern and contemporary art, consisting of more than 1000 works by about 250 Portuguese and international artists. It is an eclectic collection in terms of its thematic scope, scale and technical diversity (including video, photography and installation). The works are mainly from the time of World War II onwards, and I can identify certain authorial and thematic nuclei. It includes artists from the Iberian Peninsula (Paula Rego, Miquel Barceló b. 1957, Eduardo Chillida 1924–2002, Cristina Iglésias, Julião Sarmento, Helena Almeida, João Louro b. 1963, Francisco Tropa b. 1968, Rigo 23 b. 1966) (Figure 8), Western Europe (Arman, Karel Appel, Günter Förg 1952–2013, Sophie Calle b. 1953, Joseph Beuys 1921–1986, Damien Hirst b. 1965, Christo and Jeanne Claude 1935–2020; 1935–2009, Candida Höfer b. 1944, Mimmo Rotella 1918–2006, Jan Voss b. 1936, Anish Kapoor b. 1954) and the USA (Robert Rauschenberg 1925–2008, Andy Warhol, Dan Graham b. 1942, Nan Goldin b. 1953, Leon Golub 1922–2004), most of them artists with well-established careers. Yet there is another key strand to the collection, featuring works by artists from South and Central America (Adriana Varejão b. 1964, Kcho b. 1970, Matta 1911–2002, Vik Moniz b. 1961, Cisco Jimenez b. 1969], Nelson Leirner 1932–2020, Lygia Pape 1927–2004), Africa (Jorge Días b. 1972, Nicolas Hlobo b. 1975, Yonamine b. 1975, Gonçalo Mabunda b. 1975, Mário Macilau b. 1984) and other regions, making this a collection with global coverage. Without a political or conceptual aim, this collection opens up to artists from the Global South as a result of the curiosity aroused by contemporary art, together with aesthetic affinities and circumstantial factors.

Figure 8.

Paula Rego, A Árvore de Dubuffet (da série Homenagem a Dubuffet) (1985). © Aníbal Lemos/Coleção Norlinda e José Lima/Centro de Arte Oliva.

Acquisitions predominantly for this collection have fed the primary market, although they also occurred at auctions, with some mediated by dealers. Lima does not have a formal curator for the collection and says that he talks to curators and gallery owners: he is in contact with the Spanish Juana de Aizpuru and Helga de Alvear and is famously friendly with Cristina Guerra, Graça Fonseca and the Porto gallerists José Mário Brandão and Manuel Ulisses is well known (Amado and Duarte 2014, p. 88). Above all, he enjoys meeting artists and visits their studios regularly. He visits museums, biennials, art fairs and galleries around the world, sometimes as part of business trips. Over the course of such visits, Lima trained his eye and cultivated his taste. This unlikely collector is one of the most notable in his métier, especially after arranging the lending of his works to the Centro de Arte Oliva in São João da Madeira from 2013 onwards.51

A collection with a corporate profile is that managed by Fundação EDP, a private institution for public benefit created by the electric company EDP in 2004.52 The Foundation has played an important role in the field of patronage and the creation of prizes for visual artists.53 Since 2016, which saw the opening of the Museu de Arte, Arquitetura e Tecnologia, a cosmopolitan building designed by British architect Amanda Levete on the bank of the River Tagus, next to a historic power station, the programme of exhibitions has increased, attracting an international audience who were drawn by the new dynamic to the contemporary art sector. In terms of the collection, the new museum stimulated the resumption of acquisitions, which now number around 2400 works by 330 artists, in various artistic disciplines.54 The collection was started in 2000 with João Pinharanda, an art critic, responsible for it in the initial phase. Pinharanda defined the concept of contemporary Portuguese art made after the 1960s as a chronological marker. This choice was based on the artistic openness to international trends that was observed in the work of Portuguese artists in this period (Pop Art, minimal, conceptual). He brought together works by artists who have now achieved high renown, including Ana Vieira, Lourdes Castro (b. 1930), Ângelo de Sousa (1938–2011), Jorge Martins (b. 1940), Jorge Pinheiro (b. 1931), Helena Almeida, António Sena (b. 1941), Menez (1926–1995) and António Palolo (1946–2000). The purchase of the Pedro Cabrita Reis private collection in 2015 marked a particular influx into the EDP collection (Figure 9).55

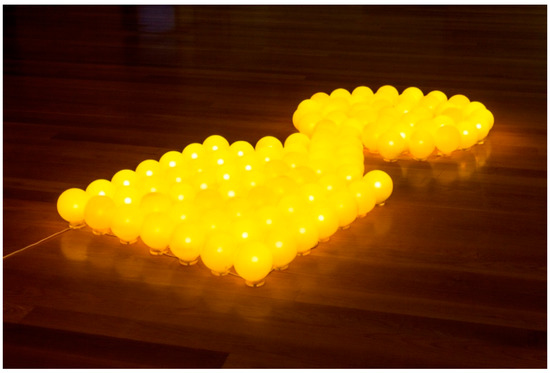

Figure 9.

Joana Vasconcelos, “Pop Luz”, 1995. © Bruno Lopes/Coleção Arte Fundação EDP/Col. Cabrita Reis.

Between 1995 and 2005, with the help of his wife, the artist Patrícia Garrido, Cabrita assembled an important collection of young Portuguese artists, motivated by the desire to repay the generosity that the art system had shown to him by recognising their work. He cites social responsibility as his motivation for collecting works by young artists who needed financial support and encouragement to pursue their art.56 He put together a set of 388 works by 77 young Portuguese artists, and was also receptive to suggestions from his assistants (who were also artists: Nuno Cera, Hugo Canoilas and João Ferro Martins). The addition of the Cabrita collection to that of the EDP was a major coup due to its stature. As it had been given the mark of approval by a major artist, it boosted the profile of the collection.57

Finally, I will underline a different type of private project. Rialto6 is a recent project that was launched in Lisbon in 2019 by the collector couple Maria and Armando (2019). They have opened up their home to the artistic community with exhibitions, events, conferences, performances and displaying their collection of contemporary Portuguese and international art. The couple has been supporting non-profit artistic projects and collecting systematically since 2006 (they have amassed around 250 works so far). The acquisitions were mainly made in the primary market, through regular attendance at art fairs (Art Basel, ARCOmadrid, ARCOlisbon, Frieze New York), initially with the support of certain art galleries (Filomena Soares, Cristina Guerra, José Mário Brandão). They have been tenaciously pursuing their own taste and line of thought about art, which they see as a tool for combatting alienation, and they have been learning in this subject in museums, at exhibitions and collaborations with other private collections (Luiz Augusto Teixeira de Freitas, José Carlos Santana Pinto).58

The collection encompasses a range of media, with a clear preference for video, installation and photography. The works date from the 1970s onwards and represent different aesthetic trends. The collection includes artists from different generations and regions, including Portugal and elsewhere in Europe (Filipa César b. 1975, João Maria Gusmão + Pedro Paiva, Ângela Ferreira, Julião Sarmento, Igor Jesus b. 1989, Elmgreen & Dragset b. 1961; b. 1969, Tacita Dean b. 1965, Harun Farocki 1944–2014, Magali Reus b. 1981), North America (Bruce Nauman, Lawrence Weiner, Cindy Sherman, Doug Aitken b. 1968, Taryn Simon b. 1975) and South America (Adriano Amaral b. 1982, Lygia Pape, Jonathas de Andrade b. 1982).

It is an ambitious project. The collectors put the emphasis on private initiative as they defend a liberal system for the visual arts. They are committed to increasing the global visibility of Portuguese art and artists and to making Lisbon’s art system more cosmopolitan.59 Rialto6 is unique because it transforms the collectors’ residence into a kind of art centre or Kunsthalle with a carefully devised programme of rotating exhibitions and tours to showcase the collection. This is an unparalleled initiative that enriches the institutional offering of contemporary art in Lisbon.

I may conclude that the selected private and corporate collectors are committed to contemporary values as their program have a clear international scope. Their collections have been progressively broadened into a wider concept to take in artists from Europe, North America and regions of the Global South. Furthermore, they have clearly changed Lisbon’s overall art scene in making their collections available to public, allowing them to act as a validating structure for the international recognition of artists.

3. Is the Peripheral Beautiful? A Discussion

This investigation leads me to conclude that there has been an upsurge in Lisbon’s contemporary art market in Lisbon in conjunction with the growing number of legitimising structures in the form of museums and art centres. While academic literature is more sceptical, citing the domestic scale and conservative taste of Portuguese collectors as a weakness (Afonso and Fernandes 2019, pp. 206–8), the data clearly shows strong development in the sector. Although the Portuguese art market may be seen as a product of a peripheral region, as stated by Magalhães (2008), it does not mean that artistic taste remains “traditionally conservative and nationalistic”, or that trends are still belatedly absorbed, as usually is associated with the peripheral markets. Lisbon appears to be an example of the perseverance of the local art market within the Global South context, allowing to rewrite the discussion of global dominance and its hierarchies.

In terms of the first working hypothesis, the drive to the enhance the art market through the contemporary gallery sector has shown strong results and evinced links with the cultural environment of the 1990s, which was favourable to investment in contemporary values. The art gallery sector, which controls the market for contemporary art, has focused on internationalisation through its ongoing participation in art fairs. Moreover, galleries have concentrated on mixed programmes, with mid-career Portuguese artists alongside their foreign counterpart in order to attract an international audience. This strategy has been taken up by the youngest galleries, who see Europa and other regions of the globe as a platform for their performance. Indeed, this follows on from the trend seen in the 1970s, in the context of globalisation. It seems that periphery, geographically speaking, can act as a complementary art scene, from which a successful internationalisation strategy can be developed through a systematic methodology. As a second working hypothesis, I testified to the role of private collector in boosting the primary art market and contributing to its rise by assembling contemporary art collections and making them available to the public. One specific characteristic of such collections is their international make-up, with international artists alongside the Portuguese, thus furthering the narrative concept and attracting international attention. And doing so, they also help to legitimise the work of artists through their exhibition programme, thus revealing a mature art market sector at work.

I set out to determine whether Portugal, and specifically Lisbon, has legitimising and commercial structures that can help its artists to gain international recognition. The research allows me to answer in the affirmative, with the caveat that there are other forces active in the Portuguese art world, as for the purposes of this study I have not covered major policy measures within the cultural sector, but rather focused on private initiatives. These structures are indeed cause for optimism, but given the predominance of the local art market the peripheral dimension remains an issue, so alternative measures still need to be implemented in order to consolidate a strong market. I believe that what is missing is legitimation through the public sector, the state and municipalities in terms of systematic collecting, permanent exhibition spaces and museums infrastructure. More broadly, we need cultural policies for Portugal’s contemporary art sector. Up until now, nurturing this area of the contemporary art system has fallen mainly to private initiatives, gallerists and collectors. Therefore, for the purpose of future research, it is worth pointing out the need of broaden case studies and research archives (a field almost untouched by academic research) in order to confirm or contest the conclusions I have drawn. Moreover, it would be interesting to examine the global art market impact of certain projects that have been launched in alternative spaces by artists and independent curators. It would also be useful to develop a quantitative methodology for questioning gallerists, in order to better understand their motivations, efforts toward internationalisation and needs within the field of art.

4. Materials and Methods

The research set out in this article takes a qualitative perspective. It focuses on surveying the existing academic literature on the topic, doctoral theses, master’s dissertations and published articles, comparing them and underlining the relevant points. I proceeded to the study of press articles (online magazines devoted to discussing contemporary visual art, such as Artecapital, Contemporânea, Umbigo, and others that have been discontinued, accessed via libraries like L+Arte, Leilões Arte e Antiguidades) and catalogues for private collections and museums created during the period of study. I also studied commemorative gallery catalogues published to mark anniversaries (Vera Cortês Gallery, Cómicos/Luís Serpa Projetos).60

I used Pordata, the database of Contemporary Portugal, to verify the growing number of art galleries and other venues for temporary exhibitions (Table 1). I also used the art map (Isto não é um Cachimbo, updated in 2019) to pinpoint galleries, museums, foundations and other places devoted to contemporary art in Lisbon (Anonymous 2019a). This information served as a reference tool for selecting galleries that were relevant to this article. The websites of the galleries and private collections were another source that I browsed in order to determine their participation in annual art fairs, their programmes and represented artists. I also interviewed and talked with some of the people mentioned here.

In some cases, I used testimonies of collectors (Armando Cabral, Francisco Capelo, António Cachola, Miguel Leal Rios, José Lima, Fernando Figueiredo Ribeiro, Arlete Alves da Silva, Pedro Álvares Ribeiro) that were collated as part of the project Ciclo Colecionar Arte, which took place at the Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea between 2013 and 2019. This cycle was organised by the author, who is also Vice-President of the association Os Amigos do Museu do Chiado—Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea and comprises dialogues between collectors and curators about the creation of their collections (motivation, taste, market, elective artists). These dialogues will be published by Veritas Art Auctioneers later this year. I also drew upon information from archival sources relating to the Galeria Quadrum, Módulo—Centro Difusor de Arte, Cómicos, Filomena Soares, and Cristina Guerra, which were examined by the author when putting together entries for the Art Market Dictionary published by De Gruyter, and which is currently on press.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author is deeply grateful to the gallerists and collectors who allowed her to study their work. All figures have been used with permission.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Adam, Georgina. 2017. Dark Side of the Boom. The Excesses of the Art Market in the 21st Century. Farnham: Lind Humphries. [Google Scholar]

- Afonso, Luís Urbano, and Alexandra Fernandes. 2019. Mercados da Arte. Lisboa: Edições Sílabo. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, Bernardo Pinto de. 1981. A temporada do Porto. In Artes Plásticas, Jornal de Letras. N. 20, s.p. File no. 1975–1981. Lisbon: Archive Modulo—Centro Difusor de Arte. [Google Scholar]

- Amado, Miguel, and Adelaide Duarte. 2014. “O meu saber sobre arte nasce da experiência do olhar: uma conversa com José Lima”. In Traço descontínuo: Coleção Norlinda e José Lima—Uma seleção (Parte II). São João da Madeira: Câmara Municipal de São João da Madeira, pp. 53–100. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 1977a. Modulo a New Selection, Cologne Art Fair. Lisbon: Módulo—Centro Difusor de Arte. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 1977b. Modulo a Selection. Basel Art Fair 8’77 (Stand 13.361). Lisbon: Módulo—Centro Difusor de Arte. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 1978. Modulo, Bologna Art Fair 78. (Stand G.153/54). Lisbon: Módulo—Centro Difusor de Arte. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 2008. Nova direção da APGA defende internacionalização das galerias portuguesas. Available online: https://www.rtp.pt/noticias/cultura/nova-direccao-da-apga-defende-internacionalizacao-das-galerias-portuguesas_n166592 (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Anonymous. 2014. ArtReview. An Introduction to the 2014 ArtReview Power 100. Available online: https://artreview.com/power-100-2014-introduction/ (accessed on 9 July 2020).

- Anonymous. 2019a. Mapa Das Artes. Lisboa. Arte Contemporânea. Available online: http://mapadasartes.pt/desktop/ (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Anonymous. 2019b. Meet Madragoa. 2019. Gallerist Matteo Consonni Discusses Art and Life in Europe’s Newest Art Hub. Available online: https://www.artbasel.com/stories/meet-madragoa (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Anonymous. 2019c. Power 100. Available online: https://artreview.com/power-100?year=2019 (accessed on 11 June 2020).

- Anonymous. 2020a. “Serralves Collection Presentation”. Available online: https://www.serralves.pt/en/institucional-serralves/-2/ (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Anonymous. 2020b. Bruno Múrias. Fairs. Available online: https://www.brunomurias.com/artfairs/ (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Anonymous. 2020c. Coleção de Arte Moderna e Contemporânea—Norlinda e José Lima. Available online: http://centrodearteoliva.pt/colecao/colecao-de-arte-contemporanea-norlinda-e-jose-lima/ (accessed on 28 October 2020).

- Anonymous. 2020d. Coleções Fundação EDP. Coleção de Arte Portuguesa. Available online: https://maat.pt/index.php/pt/colecoes-fundacao-edp (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Anonymous. 2020e. Cristina Guerra Contemporary Art. Artistas. Available online: https://www.cristinaguerra.com/artist.work.php (accessed on 9 July 2020).

- Anonymous. 2020f. Galeria Filomena Soares. About. Available online: http://gfilomenasoares.com/About (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Anonymous. 2020g. Galeria Filomena Soares. Artistas. Available online: http://gfilomenasoares.com/Artists (accessed on 9 July 2020).

- Anonymous. 2020h. Madragoa. Fairs. 2016–2020. Available online: https://www.galeriamadragoa.pt/Fairs (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Anonymous. 2020i. Pedro Cera. Artists. Available online: https://www.pedrocera.com/artists/ (accessed on 9 July 2020).

- Anonymous. 2020j. Pedro Cera. Available online: https://www.pedrocera.com/fairs/ (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Brown, Kathryn. 2019. Private Influence, Public Goods, and the Future of Art History. Journal for Art Market Studies 3: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bystryn, Marcia. 1978. Art Galleries as Gatekeepers: The Case of Abstract Expressionist. Social Research. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 390–408. [Google Scholar]