1. Introduction

Dear Evan Hansen (2015) is beginning to evidence a new phase of engagement between audiences and production. The hit musical successfully utilises utopian performatives (

Dolan 2005) to draw in audiences and engage its fandom, or, as they call themselves, Dear Evan “Fansens”. This musical in particular has seen an influx of engagement from audiences across social media, possibly more notably than other current shows popular amongst fandoms, such as

Heathers (2010),

Come from Away (2013) or

Six (2017). This engagement comes through the creation of fan art and fanfiction in line with this particular production that mirror the narrative and provide audiences with new readings of the original text, as they seek to recreate the lost liveness of their experiences with the performance. Librettist Steven Levenson discusses the importance of social media in the show.

If we tried to tell our story today without cell phones and social media, there would be a real inauthenticity about the show. And at the same time, we wanted to be sure we’re using social media as a storytelling device and we were never interested in exploring social media as a theme or as an idea. We always wanted to make sure it was grounded in the story and part of the grammar of the show.

The interactive relationship established between the show and its audience has allowed fans to create innovative methods of reshaping the way theatre engages with its audience. Beyond marketing’s previous reliance on critic reviews, official show accounts circulate posts from paying theatregoers, fans and their responses to the performance. The online presence of

Dear Evan Hansen engages, acknowledges and shares the fan-created paratexts to establish one-to-one connections with its “fansens”. It allows the fan-generated material to speak back to the performance, validating the transactional relationship between fan and production. Images and artwork shared on the production’s official Tumblr page (@dearevanhansenofficial) provide endless examples which support the analysis later in this work.

To provide context,

Dear Evan Hansen tells the story of a young teenager suffering from social anxiety (though this is not directly stated in the text). Due to his anxiety, Evan struggles to make friends and is encouraged by his therapist to write himself letters. Shortly into the musical, one of Evan’s fellow peers, Connor Murphy, takes his own life and Evan becomes caught in several lies as he convinces others that he and Connor were friends. The story then detours to focus on Evan’s spiralling lies and has a strong focus on the impact of social media in modern society. Social media becomes a heavily featured aspect within the production, being referenced not only in the book and lyrics, but also in the immersive set design and projection that can be seen throughout the production. Through exploring the show and its interactions online, it became clear that it has resonated across the Generation Z community. With an ever-growing fan base,

Dear Evan Hansen has become one the most talked about, trending musicals within the last several years. Throughout this work,

Dear Evan Hansen will be used simply as a lens in an attempt to examine how Generation Z are engaging and creating paratexts as a means of elongating what Richard

Schechner (

1988, p. 245) recognises as the cool-down moment after a performance, and seek out utopian performatives as defined by

Dolan (

2005).

Theatre is “an art that lives by, and survives largely in the memory” (

Carlson 2003, p. 211), and utopian performatives allow an audience member to be lifted from the performance through a euphoric and hopeful feeling, which, when combined with the ephemeral element of theatre, can provide spectators with a lingering memory of the performance. This ephemerality allows audiences to acknowledge and be aware of the temporary relationships being formed in the moment of performance; relationships which link audience to performance, stage, texts and other spectators. Audiences are able to create connections, as well as share emotions in response to the text and complex paradoxes inherent in being an audience member. These momentary responses from the audience can have an impact on the delivery of the performance at that moment in time, as well as impact the “live presence of spectators and performers in shared time and space” (

Freshwater 2009, p. 15). Such responses also allow audience members to take on individual ownership for their “imaginative processes” (ibid., p. 58) and inject their own beliefs and values into the performance. These new, contemporary waves of audiences are finding original methods of extending the ephemerality of theatre into the cool-down moment.

Schechner (

1988, p. 245) states that “the transition between the show and the show-is-over is an often overlooked but extremely interesting and important phase”. In this moment, audience and performer alike are transitioning from the performance of another world back to a neutral state of existence. The feelings of excitement, gratitude and euphoria have peaked. This cool-down period allows audiences to wallow in the ephemeral nature of the performance and typically ends as they end their experiences by leaving the theatre.

These new audience engagements allow us to explore the transaction between paratextuality, intertextuality and the audience. Here, the term paratext refers to materials that have been created to aid the promotion of a performance. These materials, or texts, that audiences encounter both before and after they witness a production have the ability to frame their expectations and readings of a production. As musical fandoms expand and develop their visible online presence, so have the ubiquity of fan-authored paratexts, though often unaware of the production’s intent to use this material as a means of promotion. When audiences engage with a show, they become creators through the construction of these paratexts and the way in which they are consumed. Social media is facilitating this shift towards a more collaborative relationship between production and audience, as social media users become more apparent as content creators. Younger audiences delight in such interactions, which have led to critically engaged and creative responses to the musical. Widespread access to online, interactive platforms such as Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr bring new opportunities for paratextual creativity and for re-experiencing the feelings and euphoria associated with the fleeting nature of performance. There is also something to be explored in the nature of sharing the fan-established paratextual creations for those who are yet to experience the performance moment. The relationship between fandoms is beginning to expand, in an attempt to replicate and share this ephemerality with those unable to witness the performance first-hand.

As Generation Z become more established theatregoers, theatre producers can be seen trying to adapt and keep up. This generation, and presumably future audiences, are now beginning to establish an “internet state of mind” (

Chandler and Simeon 2019, p. 2). “This mindset is shifting the power dynamics between producers and consumers, causing a decentralisation and digestation of musical theatre, which is impacting on form and structure” (ibid., p. 2). Generation Z fall into the category of those born between the mid 1990s to the mid 2000s, and whilst Millennials (those born between approximately 1980 and 1996) are technically capable, having themselves experienced the growth of social media as a platform, Generation Z began expanding on the use of social media through established platforms such as Snapchat and Instagram, and re-inventing much loved millennial contents such as GIFs and memes. With 75% of current Instagram users under the age of 24 (

Tran 2020), Generation Z are populating social media with new engagements and content that can be disseminated amongst audiences. It is this that has led theatres, productions and their retrospective marketing teams to find methods of engaging a new wave of audiences beyond the use of the standard “post” or “tweet”. Bree

Hadley (

2017, p. 4) states that the “next stage in which theatre will re-find its relevance to modern audiences [is] by addressing them in direct, individual and accessible ways”. This is something that can already be seen in recent engagements from productions within the musical theatre world, and Balme (in

Hadley 2017) refers to it as the “next stage of engagement”. Generation Z are beginning to respond to performances in ways that are unique, and have begun to establish a relationship between social media and the theatre audience. Generation Z are engaging with productions through these interactive platforms, in an attempt to seek recognition, acknowledgement and status within the fandom through the production’s representative social media platforms, developing an online participatory culture in response to the musical.

2. “Fansens”, Fan Art and Fanfiction: The Wider Context

Many fandoms demonstrate their ability to “contribute to, augment and personalise a textual world” (

Gray 2010, p. 165) through paratextual creations. Since its first appearance in 1997, social media has seen the development of a number of sites whose content stretches beyond that of a blog and the sharing of thoughts to a select number of friends or followers. A popular form of social media are visual sharing sites such as Instagram and Tumblr, where users are encouraged to share content in the form of images and videos rather than written text. Often, the algorithm for receiving this content is uniquely tailored to the interests of the users (whether through the user’s own curations or the platform’s recommendations of content that they may also like), causing interactions with others to revolve around these mutual interests. Generation Z are beginning to manipulate the use of these social media platforms. Through their expressive artwork design, reimagined stories, lyric images and animations, these audiences are finding new ways to establish communities and meaning related to the text. Though the shift in fan art and fanfiction has moved to a more digital and interactive form, these items created on social media are also of a paratextual nature. This is not necessarily a new phenomenon in itself. “1930’s pulp fanzines” (

Thomas 2006, p. 226) displayed similar paratextual creations. However, Generation Z utilise social media to cultivate and share these paratexts with their community and with the show’s creative producers in order to extend the utopian performatives of live performances. We also see a shift here as show producers and creatives begin to capitalise on these creations to sell their own production, as they exploit the fans’ engagement with the production and their eagerness to produce content.

With

Dear Evan Hansen becoming increasingly popular among younger audiences, fandoms are beginning to use these online forums to share their responses and readings of texts. These responses are shared to gain status and community amongst the fandom surrounding these texts, texts which ultimately “[…] provide a focal point through which fans can identify to which community they belong. […] they might even adopt ideals, beliefs and values […] that they feel the text valorises” (

Harris and Alexander 1998, p. 136). Their method of sharing these ideas and values comes in the aforementioned forms of fan art, fanfiction and fan videos. Upon examining these platforms, these fan-created paratexts can be seen as equally desirable, if not more desirable than the original text, which in this instance is the very moment of performance, and ultimately “these objects are the main focus of most discussions outside of the show itself and are highly prized because they require some level or artistry to master” (Sabotini in

Turk 2014).

The paratextuality of the “fansen” community ultimately feeds back on the performance moment, referencing the production and generating a wider audience and activity to surround the show. On an obvious level, this creation of new material provides the production’s marketing team with new shareable content that has the ability to draw in new audiences, but alongside this, it also allows existing audiences to re-read the show and re-experience the feelings they had associated with the original moment of performance.

Schechner (

1988) proposes that audiences follow varying post-show rituals; from clapping at the end of a production to waiting outside the stage door, audiences follow routines at the end of immersing themselves in an event as a means of mentally returning to their usual state. He notes that “ending the show and going away also involve[s] ceremony: applause or some formal way to conclude the performance and wipe away the reality of the show, re-establishing in its place the reality of everyday life” (Schechner in

Dolan 2005, p. 39)). Post-show rituals of Generation Z audiences may involve applause, waiting outside the stage door or leaving the theatre immersed in a discussion of their favourite characters, scenes and songs with those who accompanied them in the moment of performance. They also engage in documenting images of their visits, through online status updates and sharing their readings and imaginative new extensions to the narrative with their followers and others in the relative online communities, and they may reasonably expect some of this content to be recirculated, in turn, by the show’s creators or official accounts. Fans are ultimately seeking to elongate the cool-down moment, aiming to continue the experience of the production’s ephemerality and utopian performatives.

The elongation of this cool-down moment through fan art and fanfiction not only allows members of Generation Z to generate and establish additional networks between themselves but also provides an opportunity to re-establish the lost liveness of performance and re-experience the feelings that the show generates all over again. “From Twitter to Instagram, and from Blogs to Facebook, users frequently use online platforms as experience repositories. Ephemeral moments can be captured into snapshots, to be revisited and re-experienced later” (Bucknall and Sedgman in

Sant 2017, p. 113). Posting photos of themselves outside the theatre venue, boomerangs of playbills in front of the stage or artwork as a means of re-generating the euphoric feelings experienced in the theatre, users are documenting their experiences as a means generating these feelings in those yet to experience the performance moment first-hand. These imaginative fan products have ephemeral traces of the original performance moment, which are both “hinting at and hiding the origination of social engagements” (Busse in

Gray 2017, p. 53), and it can be considered that the intentions and focus of the fandom are directed at their particular communities and their “taking part in the communal activity” (ibid., p. 54). Whilst the moment of posting and the instant responses to each post are ephemeral, the materials posted online are archived and documented for long periods. The experiences with the images after the moment of posting will likely never be experienced in the same way again. Whilst they only provide a temporary fix in the seeking of utopian and ephemeral experiences, they have the potential to bring together new communities of fans. Ultimately, through the seeking of liveness and gaps within the narrative of the original text, “[a]udiences form temporary communities, sites of public discourse that, along with the intense experiences of utopian performatives, can model new investments in and interactions with variously constituted public spheres” (

Dolan 2005, p. 10), a feature which can be directly applied to the audiences of the Generation Z community.

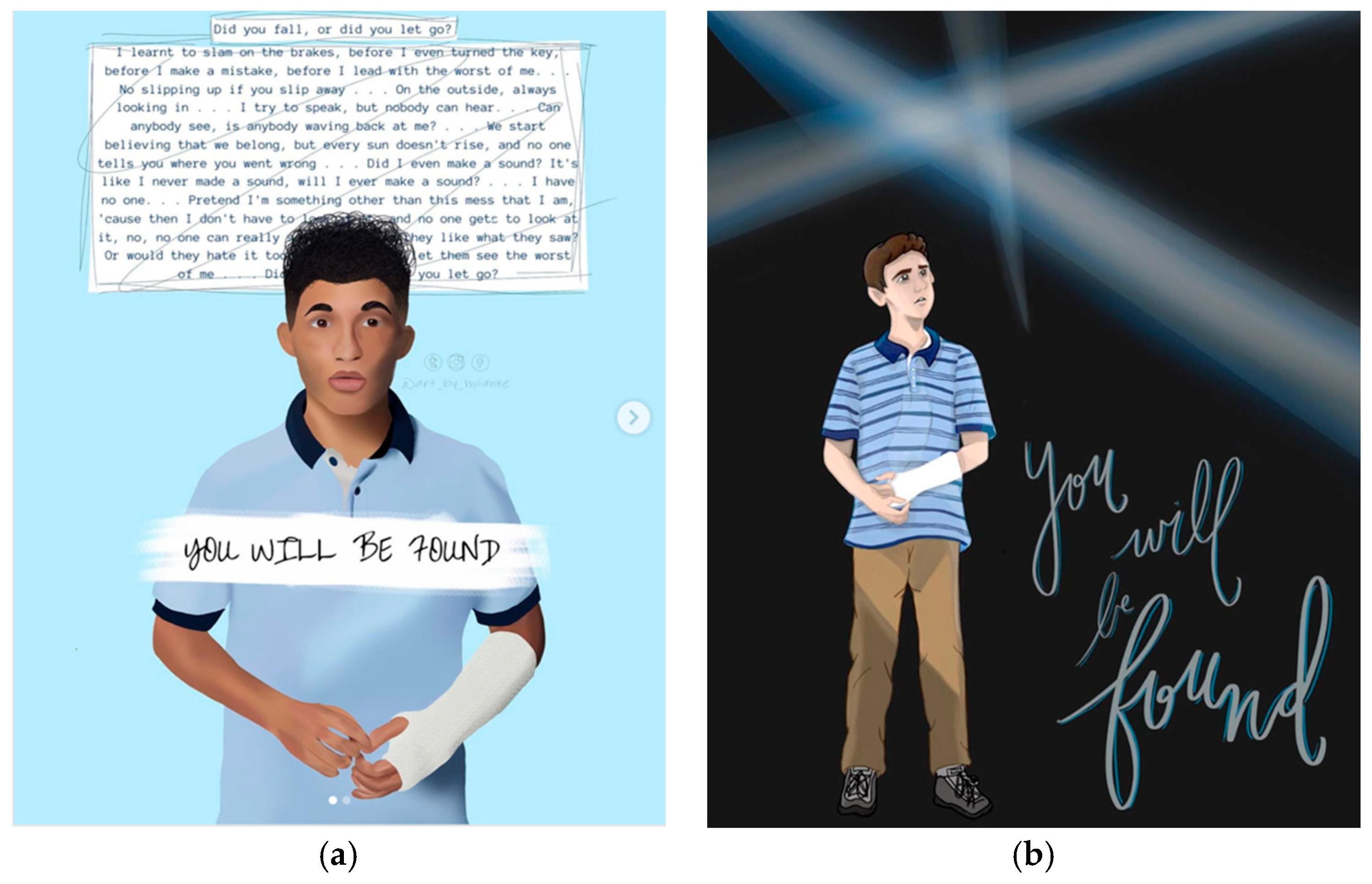

Focusing solely on Instagram, a large portion of images mirror the trends of those on the microblogging platform Twitter, as we see Generation Z audiences display a clear connection to Dear Evan Hansen’s poignant lyrics, “You Will Be Found”. Users are engaging with short phrase as the main stimulus, and the end product published in the varying social media platforms often comes in several forms. Users have a diverse range of responses to this particular phrase, and the accompanying imagery and visualisations on sites such as Instagram and Tumblr become representations of just some of the utopian performatives that exist within the original source text.

The varying presentation of these performatives is supported by Dolan, who states that “utopian performatives appear in many ways within, across, and among constantly morphing spectating communities, publics that reconstitute themselves anew for each performance” (

Dolan 2005, p. 17). Using #YouWillBeFound as an example, which at the time of writing consists of over 107K posts, the suggested “morphing” of communities becomes apparent in the different styles of posts. Several posts focus solely around the words and the meaning of the phrase as suggested in the text. The images present varying utopian performatives that are embedded within the phrase “You will be found”, such as the suggestion of a coming resolution for the fan engaging with the phrase, alluding to a world where they will indeed “be found”. Dolan suggests that live performance “provides a place where people come together, embodied and passionate, to share the experience of making meaning and imagination that can describe or capture fleeting imitations of a better world” (ibid., p. 2). We can apply this specifically to

Dear Evan Hansen, as Pasek and Paul present a set of lyrics to a song that suggest a utopian world. Audience members establish a connection to the utopian performatives loaded within the phrase that provides them with the hopeful feeling. By experiencing the original performance moment, audiences are led to read the achievability of being found and the creation of the fan art surrounding the phrase as a means of recreating the moments which they originally felt and lived within the theatre upon hearing these lyrics. Images which focus on the phrase “you will be found” often disregard other imagery that points towards

Dear Evan Hansen as a text. There is little focus on the show’s characters or signature marketing (e.g., an arm in a cast on the background of a blue striped polo shirt) or illustrations of particular moments within the show. This suggests that the utopian performatives, to these particular audience members, were found within the lyrics and in their resonance. Searching the hashtag #YouWillBeFound on Instagram will provide a multitude of examples of these kinds of images (see

Figure 1).

3. Utopian Performativity, “Shipping” and #Treebros

Contrastingly, some of the fan-created paratexts in relation to the “You Will Be Found” hashtag present a clear focus on how the text relates to the narrative and the characters in the production. Looking through #YouWillBeFound on both Instagram and Tumblr, we are able to find several artist impressions of the show’s main protagonist accompanied by the poignant and ever-recurring phrase (see

Figure 2). These images point towards the utopian performatives that can be found in the narrative of Evan’s character, though it is clear from looking at the images that they each slightly differ in emotional focus.

Figure 1 shows two pieces of artwork which present images of Evan Hansen alongside the phrase “You Will Be Found”. These images present what could be considered negative connotations of Evan and his narrative, suggesting that these were the performatives that resonated with these two members of the fandom.

Figure 2, on the other hand, presents a simple but optimistic interpretation of Evan, suggesting the utopian performatives here were found in the more positive moments of the show and the hopeful feelings accompanied by the concept of “being found”. These subtle, but noteworthy, differences in the artwork evidence the varying responses from Generation Z and how they interact with the utopian performatives presented throughout

Dear Evan Hansen. Some present a positive image of Evan, suggesting, as in the previous reading, that there is hope of “being found”. Through these paratexts, audiences seek out the utopian performatives in their personal connections to Evan. Their visual responses suggest that there is some level of relativity between the audience member as an individual and the potential resolution to the teen’s narrative presented in the original text. Others, however, present illustrations with a more negative appearance, suggesting that they are still seeking to achieve the moments that they experienced within the performance moment, in that they are still hoping to “be found”. There is evidence of a desire within the fandom to capture the moment of performance and re-experience it through the engagement with social media and the process of creating fan art. The focus on this loaded phrase, “you will be found”, is poignant to the fandom, as they seek to extend the cool-down period of experiencing the emotion and the utopia of the performance. The application of this through artwork can suggest that the fandom is using it as a way of “drawing [the performance moment] close and absorbing its essence” (

Manifold 2009, p. 10), and documenting the performance online through the posting of their animations, sketches and images.

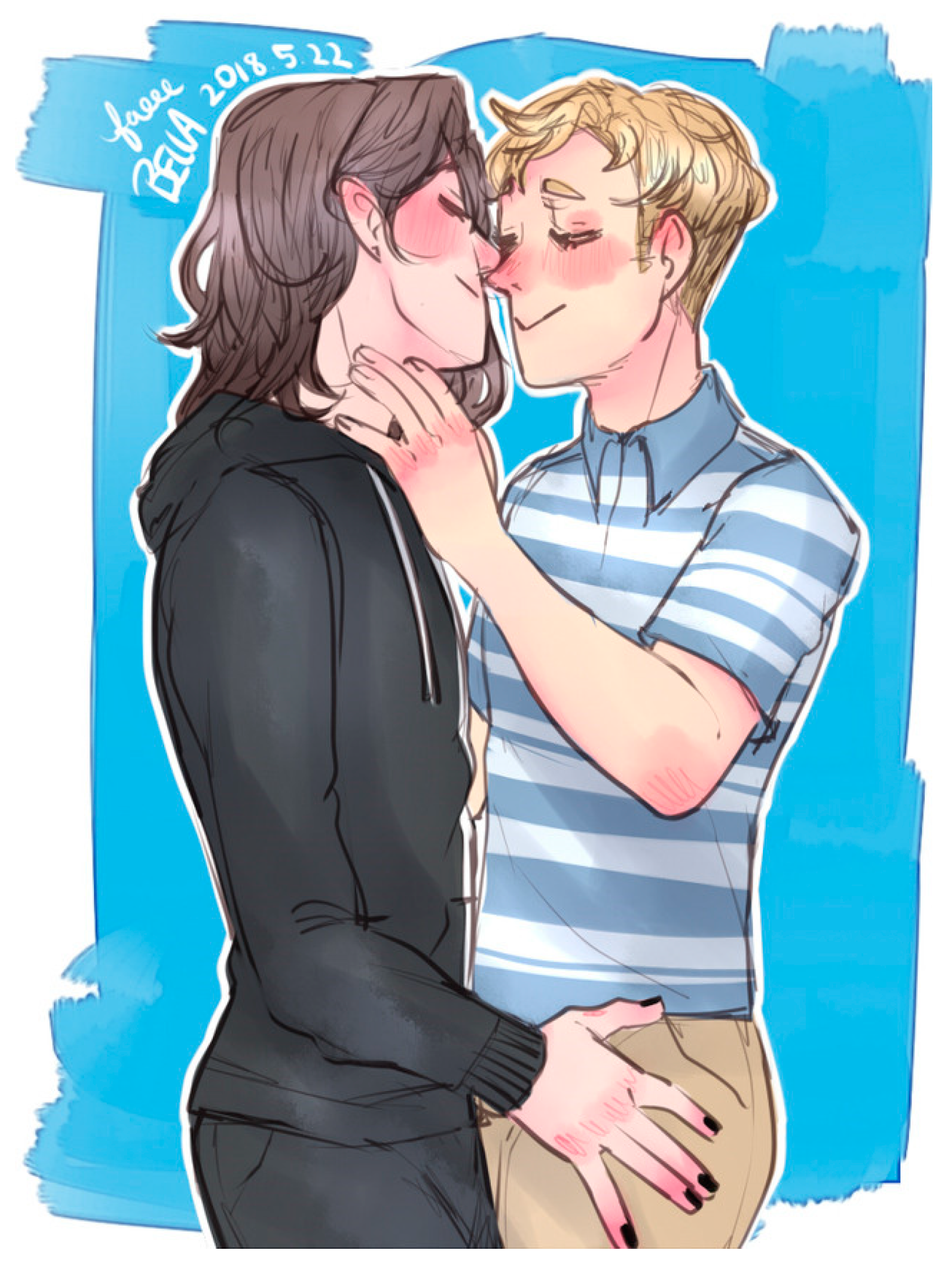

Alongside the “fansens” using imagery and illustration to share their passion for the production online, Generation Z are using social media platforms and fan art to fill gaps within the original text. These fan-created paratexts are assisting this particular fan group in their endeavours to elongate the post-performance cool-down period. Similarly, through illustrations and lengthy portions of fictional texts, audiences are re-writing the events of the production and re-imagining on-stage relationships between characters. Within the opening moments of the show, it is revealed that Connor, a mere acquaintance of Evan Hansen, has unexpectedly taken his own life. Following this, the narrative unravels as, through a misunderstanding, Evan becomes entangled in convincing others around him that he and Connor were friends. A turning point within the narrative comes with the song “For Forever”. It is this song, and the references within it, that make a poignant appearance across the materials presented online via the fandom. Here, they are taking the original text and expanding it to create additional levels of meaning. Starting with a simple, yet intriguing example, the number makes reference to Evan’s love of trees, which is reaffirmed in “For Forever” through the romanticised lyrics: “End of May or early June, this picture perfect afternoon we shared […] An open field that’s framed with trees, we pick a spot and shoot the breeze, like buddies do” (

Levenson et al. 2017, p. 84). Through his imagination, Evan creates his own utopian world, where he and Connor would share many an afternoon in a local orchard. These references to trees became a key icon of the relationship between the two characters, often seeing the two referred to by fans as #treebros (searching this on Instagram and Tumblr can again provide examples of the following analysis). The differing interpretations of the relationship can vary from fan to fan. Several images present the utopian performative of Connor and Evan as a close friendship whilst others present the two “tree bros” in a romantic relationship, a term referred to by Generation Z as “shipping”:

Shipping, initially derived from the word relationship, is the desire by fans for two or more people, either real-life celebrities or fictional characters, to be in a relationship, romantic or otherwise. Shipping often takes the form of creative works on the internet, including fanfiction and fan art. A “ship” refers to the relationship supported, while “shipping” refers to the phenomenon.

This trend raises the question as to what causes the audience’s desire to create this artwork. At the time of writing, #TreeBros on Instagram has an impressive 23,400 posts, suggesting the vast size of the “fansens”’ impact on this particular platform. Whilst the examples discussed in this article are a mere sample of the posts available online, they represent the vast majority of readings and reinterpretations of the show shared across the fandom. To give a specific example of a fan’s impression, we see the two characters in a deep embrace, with the show’s signature shade of blue creating the background (see

Figure 3). This is a more obvious representation of how the intimacy between the two characters has been manipulated by the reader, and they have created this paratext drawing from the original text within the narrative of the production and “[…] previous storylines and their understanding of the world to help them construct the meaning of their favourite text” (

Harris and Alexander 1998, p. 135). This “shipping” of Connor and Evan is not restricted to the boundaries of the “tree bros” hashtag. It seems to have occurred vastly beyond that, with the imagery of the two together becoming the most popular across the varying social media platforms. Images that directly reference the potential homosexual relationship (Generation Z refer to this particular dynamic as a “slash”) between the two characters evidence the “fansens”’ desire for this to be the case and are by far the most popular, suggesting that this is a sought after utopian performative that audiences are attempting to bring to life.

Audiences have depicted the innocent nature of the relationship and what they hope it would have been had the narrative of the production panned out differently. Audiences are establishing their own fan-made paratexts to seek out the ephemerality of the performance and extend the prescribed narrative of the original text. By creating a new strand of narrative, audiences are allowing themselves to establish their own utopian performatives, displayed within the body of their fan-written text. The excitement of discovering something that “could have been” allows them to extend and elongate the cool-down period through the consistent search for something more. The nature of these images often has the tendency, with Generation Z, to focus on the sexual relationship between Connor and Evan that has been established by the fandom. These images are often laden with intertextual references that point back to direct moments within the original text. The creators of these particular paratexts have lifted these moments out of the performance and reconstructed their meaning, ultimately reframing the original moment that sits within the text. Although the focus is less on the forming of the relationship, the very nature of these images allows us to note how audiences are rewriting Evan’s narrative. Whilst Evan’s sexuality is not directly referenced within the musical, it is implied through certain lyrics and the romantic narrative surrounding Zoe (Connor’s sister) that he is heterosexual. Fans have expressed their disagreement with this through their paratextual postings on social media. They created illustrations and imaginations of new narratives that play on the specific stereotypes of characters within the production and use imagery and illustration to fill this gap in the text. Audiences pick up on intertextual cues within the original text and piece these together to establish new readings and reconstructions. By augmenting what is presented within the original text, audiences are able to create new utopian performatives that are experienced within the paratexts of the production. Moreover, these new materials have the ability to establish a false horizon of expectation for those who are yet to experience it first-hand.

The reframing of Dear Evan Hansen through fan-created paratexts is prominent across the different platforms, but not limited to the production of art. Narrative-based content is a continuously growing and extremely popular form of engagement within the Broadway and musical theatre communities. Fanfiction is not new and not particularly specific to the engagements of Generation Z on social media. It is, however, disseminated and created in new ways by this particular community. Fans of Dear Evan Hansen are still engaging with the musical and fanfiction in the original format, writing detailed accounts of new narrative strands that feed off the original text. Whilst it is difficult to get the exact statistics from some platforms, the vast amount of fan-created material in the form of fanfiction suggests an extremely extensive engagement from Generation Z.

At the time of writing, Reddit (popular blogging and sharing site) and Tumblr display a wide variety of material available, and

fanfiction.com (2019), a popular platform amongst writers, produces a range of results for the search “Evan Hansen Fanfiction”. Each of these results indicate a carefully constructed extension to the narrative of the show, with pieces often reaching 1000+ words, and one particular example reaching an impressive 74,000 words and 20 chapters surrounding the narrative between Connor Murphy and Evan. These extensions of the production’s narrative become paratexts through their reference to the production, again created with the intention of elongating the cool-down moment by keeping the memory of the performance moment and the individual’s connection with the utopian performatives within it. “Fans are people who attend to a text more closely than any other types of audience members” (

Harris and Alexander 1998, p. 136). It is this that allows them to establish the gaps within the performance that inspire them to create the vast amount of material available on the various platforms, as shown by the above examples of extensive writing and fan art. The fans not only combine the written element of the narrative with imagery and illustration, but are also reconstructing the very nature and structure of what other generations know as fanfiction into smaller, text-based snapshots of narrative known as memes. We millennials know a meme as a simple image usually accompanied by a witty phrase or anecdote. However, as Generation Z began to establish their presence on social media, the meme has evolved into more than just a picture with text on it. Generation Z immerse themselves in the culture of sharing entertaining things on the internet, and in this context a meme is much more than a simple, short and comedic piece. Whilst memes display a similar focus, these short and simple fragments of text range from a snapshot of the fan’s experience to a 74,000-word document establishing relationships or an extension to the narrative. Again, a large portion of these contributions seem to focus on the #TreeBros trend and the relationship between Connor and Evan.

4. The Novel as Paratext: Fan Art and Fanfiction as Broadway Musical Marketing Ploys

Whilst there is a large portion of the fandom “shipping” the relationship between the two fictional characters, there are some who are arguing the case. When we refer here to the original text, it is the stage production that is being referenced. This is often the stimulus for the creation of these paratextual images and stories. Fan-created paratextuality is “shap[ing] stories and creat[ing] tropes, which in turn shape our perceptions and creates more stories” (Busse in

Gray 2017, p. 46), such as that of Evan and Connor’s romanticised relationship. The fans are in fact filling in the gaps that exist within the text that they are framing. However, in 2019, Val Emmich collaborated with Pasek and Paul to publish a novel of the production—a relatively new phenomenon, as we usually see adaptations happen in the reverse order, that is, with the production becoming an adaption of a book or alternative original text. The novel in itself, laden with both paratextual and intertextual references, became a new stimulus for the fandom to piece together moments within the narrative. It provided audiences with new extensions to the narrative and confirmations (or indeed rejections) of fan-imagined narratives set out in paratexts presented on these social media platforms. At the time of writing, the novel currently ranks at 8th for “Amazon’s Bestsellers in Books on Death for Young People” which poses several suggestions about the text. This text led various users to post within the “fansen” community, questioning the legitimacy of their readings of the production. One user suggests the premise of the novel as evidence to support the contradictions of the new strands of the narrative being created by other online users, particularly the very nature and likeliness of the relationship between Connor and Evan. The novel shares a similar purpose to that of the creation of fan art or fanfiction, by allowing audiences to extend the cool-down period after the performance moment. The book also shares a quality of excitement for the fandom, as it provides them with the imaginings of new utopian performatives, allowing them to experience new moments within the narrative and the meaning within it.

Beyond these deeper moments of analysis of the fan’s use of their created material, it is also worth exploring how

Dear Evan Hansen utilises these as a means of benefitting their production. It is clear how “[f]an communities contribute significantly to the presence of [

Dear Evan Hansen] on social networks” (

Lacasa et al. 2017, p. 53) through the consistent sharing and engagement with the marketing methods implemented by the production. Through the engagement with #YouWillBeFound, users are encouraged not only to post images of themselves for marketing purposes, but they have also interpreted this as using the hashtag as a means of sharing their work. By sharing their own creations in their personal online accounts, users encourage the engagement of those less likely to have been exposed to the production and ultimately draw in new audiences for the production. These paratexts support the show and provide it with new ways of sharing their material to a wider audience. Though not created directly by the production, these fan-created paratexts have the same effect. The use of the fan-created paratexts in this manner present fragmented barriers between the fans and performance, and the promotion of the show’s message to attract new audiences. The creation of fan art, more so than fanfiction, is often inspired by these key messages of the production, mostly the notion of fans “being found”. This potential exploitation is used to encourage people to engage with the musical’s online presence. Looking at

Dear Evan Hansen’s Tumblr page, the production is active in re-sharing, commenting and acknowledging the user content being posted to the platform. Furthermore, there have been feminist considerations regarding the paratext and the use of fan labour which could be further explored in line with

Dear Evan Hansen’s sharing the work of their avid supporters.

Busse (

2015) states that “Even though many fannish labours of love are performed by men, there tends to be a split, where often traditionally male-dominated fan activities move to create secure monetary remuneration and traditionally female-dominated ones do not” (p. 114). The identities of Generation Z fans play a considerable role in the transaction between paratext and production.

In the exploration of both fan art and fanfiction, it is clear that there is an evident cycle between fan-created content and performance. This trend, popular amongst Generation Z, proves successful in assisting in the transaction between fan and production, but also in providing the production with endless amounts of fan-generated marketing. It is important to note that this particular phenomenon is not limited to Dear Evan Hansen. Broadway musicals have begun to see a shift in the marketing strategies, with productions such as Hamilton receiving similar attention from their fandom in relation to fan art and fanfiction. The performance ultimately speaks to the fan-created paratexts by providing a stimulus and imagery to be deconstructed. From here, fans use their first-hand experiences both of the performance, the original text and their own lived experiences to cultivate a new reading of the performance and express this in the form of art or a piece of creative writing. Fan paratexts and the performance moment are intrinsically linked, and the impact of this is the reshaping of the horizons of expectations of the performance for other readers, particularly those yet to experience the performance first-hand. The participation in the creation of these paratextual works can be put down to an attempt to elongate the cool-down moment, each image being a snapshot of an individual’s utopian performatives, derived from the original text. Fans generate this material not only with the intent of establishing additional networks between themselves, but also as a means of re-living and re-experiencing the show, along with the feelings it generates.

5. Conclusions: Towards a More Co-Creative Culture

Dear Evan Hansen utilises social media as a means of engaging audiences. Through marketing and establishing strong fan communities, the production is ultimately able to effectively brand itself as a means to generate interest and excitement surrounding the production. “Participatory spectatorship had become a hallmark of brand

Dear Evan Hansen as it continues to engage with audiences in online spaces” (

Chandler and Simeon 2019, p. 8), thus linking “Virtual Broadway”, as coined by Pasek and Paul, to the show’s diverse and impressive fan base. The production engages with this fan base across several platforms, such as Instagram, Tumblr and Twitter. These interactions are becoming increasingly personal and engaging Generation Z with the performance text.

Through its textual messages, marketing and online interactions, the production promotes the need for its audience to “be found”. This loaded phrase becomes a paratextual reference in itself, pointing back to the signature song of the production. Dear Evan Hansen cleverly utilises the popular microblogging tool, the hashtag. This can be seen across all platforms discussed previously, to serve the main purpose of connecting people and introducing them to a community. The #YouWillBeFound movement that has been trending over the various platforms since before the production’s Broadway debut has begun to make an impact on the theatre industry. It encourages fans to join the “fansen” community and changes the way in which audiences consume the musical and interact with the production’s post-performance. There is the argument that audiences are being exploited through this particular selection of lyrics, combined with the fan-created paratexts available across the varying social media platforms; that this need to “be found” is encouraging fans to remain active in the participatory nature of the show’s online engagements.

Making up over 15% of the Broadway demographic (

The Broadway League 2018) and establishing a new voice within theatre, Generation Z are demonstrating a shift in the way Broadway musicals and the theatre industry engage with their audiences. Teen audiences are finding ways to interact with productions they have limited access to through platforms such as Instagram, Tumblr and Twitter in the community of their fandom.

Hadley (

2017) poses the question of whether social media will eventually cause audiences of the arts to lose the authentic ephemeral presence. Judging from the research presented in this article and the evident shift in theatre interactions, theatre has the potential to become more interactive. Content has the potential to fall into a more commercialised state, as marketing through social media can become targeted and manipulated to suit varying audiences. Whilst the option to live-stream, document and archive performances online becomes far more readily available, theatre still relies on the element of liveness. Though Generation Z are a technically capable generation, it can be stated that, in order to engage with a production, they have the tendency to become “bound by the parameters of social propriety established partly by communities formed online” (

Manifold 2009, p. 9). These fans still fall into the habits of idolising performers, relishing in the atmosphere of the theatre auditorium and choosing their merchandise as they eagerly await the house doors to open. It is clear that Generation Z are far more engaged with the intertexts and paratexts of a show, and it is possible that we will continue to see a peak in these interactions as social media continues to develop and become more accessible.

Social media is, in fact, driving a shift from the “mass media paradigm that dominated the 20th Century, to the more co-creative, collaborative and democratic media paradigm” (

Hadley 2017, p. 3). This can also present the concept of a shift throughout the theatre industry, via social media, towards a more co-creative culture (

Hadley 2017, p. 7). Fans are becoming increasingly critical of texts, through their interactions, and are consistently rebuilding their own values and knowledge through the interpretation of the text. “To interpret a text, to discover its meaning, or meanings, is to trace those relations. Reading thus becomes a process of moving between texts. Meaning becomes something which exists between a text and all other texts to which it refers and relates, moving out from the independent text into a network of textual relations. The text becomes the intertext” (

Allen 2000, p. 1). These interpretations are only confirmed and reinforced through the interactions of a community, online.

The intertextual and paratextual relations surrounding Dear Evan Hansen provide the text with an array of layers that can be unpicked by the audiences and the fandom. Through the co-creative element of Generation Z’s interactions with Dear Evan Hansen, they are reconstructing the text and paratextually impacting the way in which the performance is being read and received. It is evident that it is possible for the paratexts to alter the horizons of expectations. The paratexts created by the production (cast recordings, posters, press releases, a novel, etc.) can be formatted to provide a streamlined, singular reading of the production that is in line with the original text. Essentially, what we are getting here is the producer, director or marketer’s version of the paratexts they want us to see. These production-based materials create a general “buzz” surrounding the production, accompanied by recognisable logos or the confirmation of the “6-time Tony Award winning production”. The paratexts have the ability to frame an audience’s expectations, and therefore, contrastingly, the engagement with fan-created paratexts such as fan art, fanfiction or videos, can create a more flexible and individual relationship with a production, and the expectations surrounding it. As with the novel, which re-framed the original text, these new interactions and paratextual creations of Generation Z are beginning to speak back to the original text. In an attempt to gain recognition and status from the creators of the original text, audiences are engaging with the various social media platforms, uploading reconstructions of the text, vocal performances of their favourite songs and engagements with a community. The interaction with these reconstructions of Dear Evan Hansen establishes a cycle in the paratextual and intertextual reception of the show.

This cycle allows Dear Evan Hansen to push the limits of social media through the application and utilisation of Dolan’s performatives to ultimately allow the fan base to extend the cool-down moment, as proposed by Schechner. Dolan states that “utopia in performance argues that live performance provides a place where people come together, embodied and passionate, to share experiences of making meaning and imagination that can describe or capture these fleeting imitations of a new world” (2005, p. 2). Through Generation Z’s engagement with Dear Evan Hansen, we can see a reinvestment of their energies via the online platforms, and they embody these utopian performatives in their own online identities, as well as embedded within the body of their interactive and paratextual designs.