Abstract

Numerous images embedded in the painted decorations in early modern Central and Eastern European synagogues conveyed allegorical messages to the congregation. The symbolism was derived from biblical verses, stories, legends, and prayers, and sometimes different allegories were combined to develop coherent stories. In the present case study, which concerns a bird, seemingly a nocturnal raptor, depicted on the ceiling of the Unterlimpurg Synagogue, I explore the symbolism of this image in the contexts of liturgy, eschatology, and folklore. I undertake a comparative analysis of paintings in medieval and early modern illuminated manuscripts—both Christian and Jewish—and in synagogues in both Eastern and Central Europe. I argue that in some Hebrew illuminated manuscripts and synagogue paintings, nocturnal birds of prey may have been positive representations of the Jewish people, rather than simply a response to their negative image in Christian literature and art, but also a symbol of redemption. In the Unterlimpurg Synagogue, the night bird of prey, combined with other symbolic elements, represented a complex allegoric picture of redemption, possibly implying the image of King David and the kabbalistic nighttime prayer Tikkun Ḥaẓot. This case study demonstrates the way in which early modern synagogue painters created allegoric paintings that captured contemporary religious and mystical ideas and liturgical developments.

1. Introduction

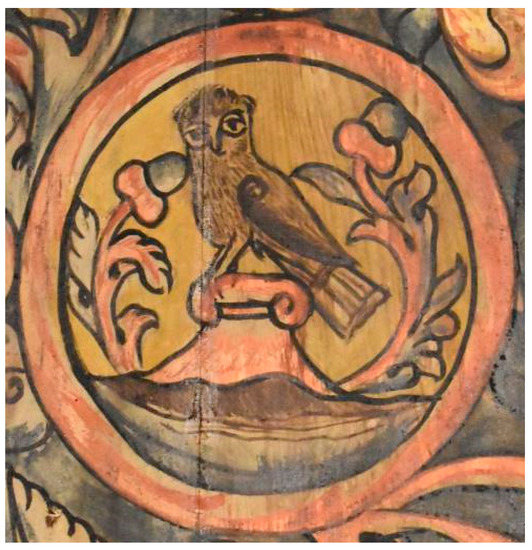

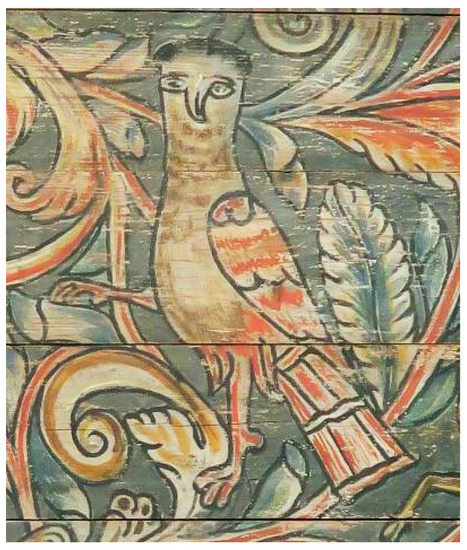

Among the animals depicted on the ceiling of the Unterlimpurg Synagogue, a nocturnal bird of prey stands out as one of the most peculiar: standing on an ionic capital and staring at the viewer with its large eyes and a mysterious smile, this bird is an enigma (Figure 1). Jewish imagery in the Middle Ages and the early modern period included numerous zoomorphic motifs whose symbolic intent was based on biblical verses, stories, legends, and prayers.1 However, the nocturnal birds appearing in these sources have never been investigated thoroughly. Perhaps the reason is the scarcity of these images as compared with the more popular animals in the Jewish artistic tradition, such as the lion, the deer, and the eagle.2 Moreover, in synagogue paintings, nocturnal birds of prey were only documented in three synagogues in Franconia and its vicinity (today southern Germany): in the Bechhofen, Horb, and Unterlimpurg synagogues.3 Thus, I have no intention of formulating a general symbolic or allegorical import of the owl in Jewish art but, rather, I decipher its particular meaning in the Unterlimpurg Synagogue based on Christian and Jewish artistic precedents. One of the initial challenges I faced was the need to determine the name of the nocturnal bird under discussion here, one of which is in Unterlimpurg, as there are no references in the Hebrew visual sources regarding the names of the specific birds. Hence, although it is clear that the bird depicted on the ceiling of the Unterlimpurg Synagogue is a nocturnal bird of prey, it is hard to determine what it was named by the painter and his contemporaries in Hebrew, Yiddish, German, or Latin, as the Bible, as well as Ḥazalic and Christian literature, mentions several kinds of such birds.4 Thus, the discussion relating to this imaging focuses primarily on the general characteristics of nocturnal birds of prey in Jewish and Christian literature and art. For convenience, all such discussed in this study are referred to as “owls”.

Figure 1.

An owl, painting on a wooden panel. Unterlimpurg, Synagogue, 1738/9. Schwäbish Hall, Hälisch Fränkisches Museum. Photograph: Zvi Orgad, 2017. Used by permission.

2. The Owl as a Herald of Redemption

The painting on the ceiling of the Unterlimpurg Synagogue shows an owl facing the viewers while standing on an elevated hill-like podium, topped by an ionic capital. Branches appear on either side of the bird, each with a bud. At first glance, the owl’s solemn gaze and pose implies a positive image. This might seem peculiar, because, based on several well-known biblical verses that talk about it nesting in ruined buildings, the owl is usually considered a harbinger of destruction. However, early modern Jews could actually adopt positive connotations for the owl as a herald of redemption from these same verses, as they do not refer to the destruction and bitter end of Israel, but of the empires that enslaved the people of Israel. The owl in the verse, “The desert owl and screech owl will possess it; the great owl and the raven will nest there […]” (Isaiah 34:11, NIV) is part of a prophecy telling of God’s revenge on Edom: “[…] God will stretch out over Edom the measuring line of chaos and the plumb line of desolation”. In Jewish tradition, Rome and its Christian heirs are identified with Edom.5 Thus, European Jews could interpret this verse as a promise of God’s vengeance on the rulers of the Christian lands where they were persecuted. Although this biblical chapter does not specifically mention the fate of Jews living in the Edomite regions, European Jews may have construed it as implying redemption and the reconstruction of the Temple. A second example is in the book of Zephaniah (2:13–14, NIV), where owls symbolize the destruction of Assyria: “He will stretch out his hand against the north and destroy Assyria […]. The desert owl and the screech owl will roost on her columns”. Finally, Yalkut Shimoni (a medieval compilation of Ḥazalic sources) compares the destructions of two of Israel’s enemies—Egypt and Aram—and views the ten plagues in Egypt as a sign of the plagues that are to come upon Aram. In this list of plagues, that of arov was equaled to destruction in the verse “The desert owl and screech owl will possess it” (Yalkut Shimoni, Isaiah 24, sign 424).6 It seems, then, that based on these Hebrew texts, the owl might imply the Jewish narrative of redemption. A link between the owl and redemption can also be found in depictions of an owl in one late medieval and one early modern haggadah.

3. The Jewish Owl

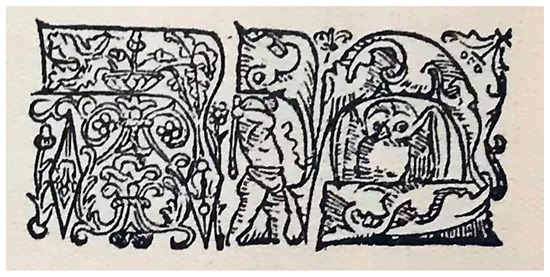

Only a few owls were depicted in Hebrew illuminated manuscripts in the late Middle Ages and the early modern period. Two images of owls might be seen as representing not just the narrative of redemption but also the actual embodiment of the Jew persecuted in a foreign land under Christian rule and anticipating being redeemed. One of them appears in a popular haggadah printed in 1527 in Prague by Gershom Cohen (Figure 2).7 Studies of this haggadah have focused on the depictions of human figures and the narrative scenes that illustrate the text.8 However, the book also includes depictions of human, vegetal, and zoomorphic motifs that were combined to decorate the initial words. Each letter of these initial words was designed with one or more figures that were repeated every time they appeared throughout the book. To date, these illustrations have been considered as merely decorative additions, their symbolic intent generally ignored.9 The letter “מ” was systematically decorated with two figures: on the right, inside the letter, is an owl that is staring at the reader. To the left, underneath the leg of the letter, a human figure wearing a loincloth is swinging a stick toward the bird in a threatening way.

Figure 2.

Decorated initial word, woodcut. Passover Haggadah, Prague, Gershom Cohen, 1527. Photograph: Zvi Orgad, 2019.

In this combined illustration, the owl is depicted en face, as was common in owl paintings in the medieval and early modern periods. In consequence, the owl acquired personality and potentially enlisted the viewer’s sympathy. In contrast, the face of the man on the left is hidden by the hand holding the stick, so he can be interpreted as an anonymous threat. As other initial word decorations, the illustration of the letter “מ” appears on several pages of the haggadah, so it probably was not designed to illustrate a specific text but, rather, was related to the whole haggadic story. Hence, it may well be that this threatening figure symbolizes the enslaving Egyptians in a manner that fits the text: “The Egyptians made us angry and tortured and gave us hard work”.

In contrast, the tremulous gaze of the owl may illustrate the text that describes the Jewish people’s prayer for salvation: “and the Children of Israel sighed from the work and yelled out”. Moreover, the painting shows the owl isolated and protected from his human pursuer, who—despite his threatening pose—cannot harm it. This composition may relate to the closing line of the piyyut, Vehi She’amda: “Not only one [enemy] threatened to destroy us, and the Holy One blessed be He, saved us from them”. Therefore, the letter “מ” protecting the owl in this illustration might stand for “melekh” (the king—the Almighty). Further, to describe the owl being protected from its enemies, the painter depicted it hiding in the darkness. This darkness may be a symbol for exile, as it is called in the begging for redemption at the end of the piyyut: “You will turn the darkness of night into daylight”.10 Thus, in this scene, the owl might represent the Jewish people anticipating redemption.

The sympathetic rendition of the owl in the Prague Haggadah and its identity as representing the enslaved people of Israel may have been a response to negative traits that were associated with owls in medieval Christian literature and the obscene qualities that were considered “Jewish”, for example, in the aviary and bestiary books.11 The owl was described as a bird that prefers darkness over light—just as the Jew rejected the light of Jesus.12 Many owls were depicted with two horns, which might have recalled the popular medieval horned image of Jews, especially Moses,13 and anti-Semitic images of horned Jews seen in early modern German lands.14 The text in bestiaries emphasized the owl’s hatred toward Christianity, which was expressed by living in the ruins of churches, eating the pigeons’ eggs, and drinking oil from the lamps of the church altars.15

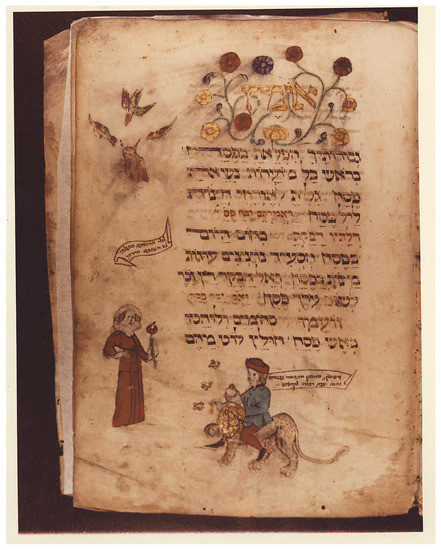

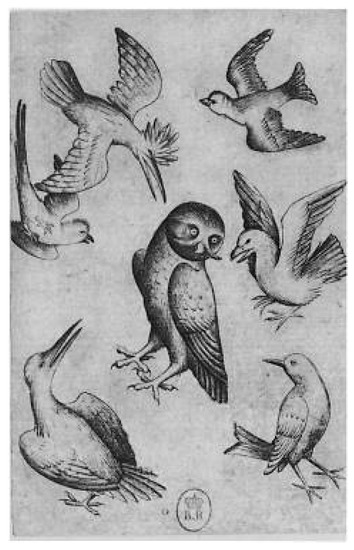

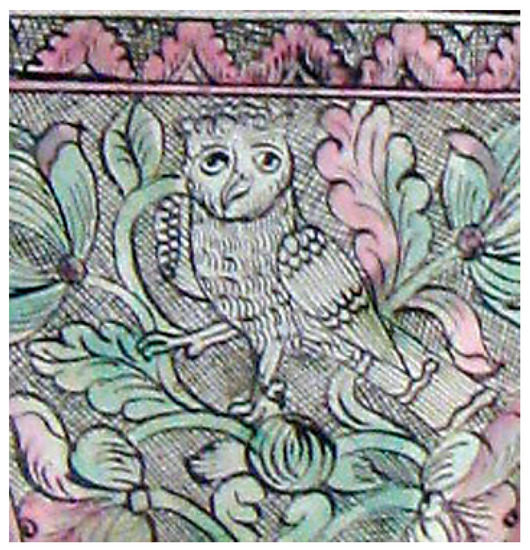

A scene showing an owl being attacked by smaller birds in a late medieval German haggadah indicates how Jewish painters used the negative image of the “Jewish owl” in an opposing approach, turning it into a positive Jewish motif. In the Second Nürnberg Haggadah,16 created in the second half of the fifteenth century, an owl is depicted being attacked by three smaller birds (Figure 3). As in the Prague Haggadah, the painter appears to be sympathetic toward the owl, which, portrayed with a bowed head and a melancholy gaze, seems to be trying to protect itself. The other paintings on the same page support the contention that owl symbolizes the Jewish people. Underneath the owl, we see a scroll with Samson’s riddle to the Philistines: “If you had not plowed with my heifer, you would not have solved my riddle” (Judges 14:18, NIV). This phrase is associated with the painting at the bottom of the page, which depicts Samson tearing the lion apart on the right and his Philistinian bride standing on the left.17 According to the biblical tale, Samson’s wife seduced him to reveal the solution to this riddle and secretly told the Philistinians his answer, a betrayal that cost Samson both money and prestige. In an unusual way in this haggadah, the scroll containing the riddle was set almost equidistant between the biblical scene at the bottom of the page and the owl at the top. Apparently, the painter intended to link the phrase inside the scroll to both the biblical scene and the owl, based on the Jewish tradition that viewed the people of Israel and the Torah as a wedded couple18 and on Rashi’s interpretation of the word “heifer” as “wife”.19 The rhymed phrase can be interpreted as an accusation made by the owl—apparently representing Moses or the Jewish people—against the three birds—possibly representing the Christian Trinity—for stealing the Torah, considered the Jewish people’s wife, and falsifying it in order to harm the Jews. The Jews’ feeling that the Torah was being stolen from them could have been a response to the printing of German translations of the Bible in the second half of the fifteenth century—about the same time the Second Nürnberg Haggadah was created.20 Therefore, this owl might represent the persecuted Jewish people, perhaps in an apologetic way. The image of an owl attacked by smaller birds has its origins in Christian art. A similar composition showing six birds that are attacking an owl, which might have been used as a visual model by the haggadah painter, can be found in a card made by the Playing Card Master in mid-fifteenth-century Germany (Figure 4).21 However, from the awkward look of the owl, this painting seems to follow a medieval tradition of portraying this scene with sympathy toward the smaller birds, which symbolize Christians—their superiority expressed by their ability to fly—who show hate toward the “Jewish owl” for its immorality—implied by its poor flying abilities (Figure 5).22

Figure 3.

An owl attacked by birds. “Second Nürnberg Haggadah”, Germany, fifteenth century; COLLECTION OF DAVID SOFER LONDON, fol. 39r. Used by permission.

Figure 4.

An owl attacked by birds. Master of the Playing Cards, [today’s] southern Germany, first half of the fifteenth century; Paris, Bibliothéque Nationale. Used by permission.

Figure 5.

An owl attacked by birds. Bestiary, England, second quarter of the thirteenth century; London, © British Library Board, MS. Harley 4751, fol. 47r. Used by permission.

Early modern depictions of owls in German Christian illuminated manuscripts testify to the continuation of the “Jewish evil” theme ascribed to the owl.23 In an early sixteenth-century illuminated manuscript from Nürnberg,24 a seemingly taxidermy owl stands on a tree stump, flanked by many songbirds, while above them is a scene of Christ and eleven apostles. Hence, the owl, standing on what could be identified with the damaged Old Testament, might have embodied the missing twelfth apostle—Judas. In another illuminated manuscript from the early sixteenth century,25 an owl is shown as an ill-omened sign for Jesus’s destiny: on the upper part of the page is the adoration of Jesus by the three magi, while at the bottom, an owl with two horns is fleeing from sunlight with a small bird in its beak. In the Christian society of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in England, owls continued to symbolize the threatening Jew: the owl as an anti-Semitic symbol lasted in England well into the seventeenth century, even when there were no longer any Jews was living there. However, it also represented other religious rivals, such as Catholics, or political opponents, such as the Puritans.26 A comprehensive study has not yet been conducted on the meaning of the owl in the German lands in the early modern period. However, Dutch and German proverbs that were common in these regions portray the owl as a bird that refuses to see the light—as in anti-Jewish images of the owl in the Middle Ages. These proverbs were illustrated in Dutch and German prints throughout the seventeenth century,27 which might indicate that there, as well, owls represented evil and possibly reflected anti-Semitic biases.

We know of very few examples from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries of owl paintings in religious sources bearing symbolic or allegoric messages. This dearth might be due to the increasing acknowledgment in the seventeenth century that animals, as Descartes put it, obeyed physical laws and thus were not suitable tools for symbolizing human moral virtues and vices. This contention led to the denial of moral attributes of animals among the Cartesian school of philosophers.28 Another reason for the diminution of animal symbolism might have been the extent of research and the revelations regarding the natural world: from the sixteenth century on, researchers began publishing books including scientific facts about exotic and farm animals, among them the owl.29 However, these new conceptions existed side by side with traditional medieval thought, which viewed animals as analogical representations of human traits. These earlier notions were commonly shared by theosophical writers, such as the German Jacob Bohem, who, in 1623, claimed that man embodied the properties of all animals and, therefore, could be understood through animal symbolism.30 Thus, even though there is very limited evidence of symbolic owl paintings from the seventeenth century, this symbolic approach might well be a link to the painting of the owl on the ceiling of the Unterlimpurg Synagogue. Hence, this motif might be thought of as a successor to the owl paintings in medieval traditional art and thought.31 Bearing that in mind the perceptions illustrated in the Nürnberg and Prague haggadot—the identity of the persecuted Jew and the narrative of redemption—can explain the inclusion of the owl in the Unterlimpurg Synagogue. However, this owl also represents further symbolic elements that together create a more complex allegorical picture.

Before analyzing each of these elements, I have to clarify the approach of the Unterlimpurg Synagogue painter regarding symbolism. Wooden beams divide the synagogue’s ceiling into fifteen separate areas. The painter exploited this construction to create a composition comprising fifteen separate motifs, almost all of them zoomorphic, thirteen of which are framed by wide round borders. This kind of composition is unlike those in other documented synagogue ceilings in the same geographic area, such as in Bechhofen and Horb, on which the painter integrated the animal scenes into one vast vegetal pattern that defined the space. Further, in these two synagogues, most zoomorphic motifs were depicted more than once, whereas in Unterlimpurg, there is only one depiction of each animal. Thus, each of the zoomorphic motifs in the Unterlimpurg Synagogue seems to attain a higher symbolic value than those in the others. Some of the symbolic motifs include several elements: a lion standing beside a castle; a bow and arrow hovering above the water and flanked by trees; an elephant carrying a construction on its back; and a bird standing on an ionic capital with a horseshoe in its beak. In these complex motifs, each element, as well as the overall design, speaks to the symbolic import. The painter of the Unterlimpurg Synagogue combined elements from various sources that were carefully chosen to convey a message. For example, the elephant was copied from a similar figure depicted on the Horb Synagogue ceiling, painted by Eliezer-Zusman, who was probably the former employer of the Unterlimpurg Synagogue painter.32 In contrast, the design of the construction on the elephant’s back was changed from a seemingly plain residence in Horb to a vaulted symmetrical building with two towers, which suggests that this specific construction represents the Jerusalem Temple.33 The comprehensive symbolic implication is thus messianic and expresses hope for redemption and the building of the Third Temple. Similar to the elephant, the owl painting in the Unterlimpurg Synagogue is not a random assembly of elements derived from various visual and verbal sources, but a combination of carefully selected motifs designed to convey an allegorical message. I suggest that the goal was to express the idea of the night prayer as a way to expedite redemption and that the portrayal of the owl was likely a way to represent King David without depicting a human figure or a crown.34

4. The Owl and King David’s Tikkun Ḥaẓot

The owl in the Unterlimpurg Synagogue is perched on an elevated platform, which is in the shape of a hill or a mountain. Figured in this way, it might represent the Temple Mount, a common notion in Ḥazalic literature, or a synagogue: according to the Shulḥan Arukh, a synagogue should be built in the highest place in the region (Oraḥ Ḥaim 100:2). An image of a hill or a mountain could also indicate the city of Jerusalem, which eighteenth-century Jews in southern Germany often identified with an elevated place. An inscription evidencing this association was documented in the Kirchheim Synagogue, for which the decoration was completed by Eliezer-Zusman around the same time as the adorning of the Unterlimpurg Synagogue.35 The inscription, which appeared above the depictions of the city of Jerusalem and the Temple, included a prophecy of comfort: “You who bring good news to Zion, go up on a high mountain” (Isaiah 40:9, NIV); “Zion will be delivered with justice, her penitent ones with righteousness” (according to Isaiah 1:27, NIV). The first verse is part of the prophecy of consolation “Comfort, comfort my people” (Isaiah 40:1–31), the haftarah for the Shabbat after Tisha Be’Av, proclaiming that Jerusalem’s time of anguish is over, its crime is forgiven, and from this moment exile ends and redemption begins. The Unterlimpurg Synagogue painter was most probably familiar with this inscription in the Kirchheim Synagogue and its association with the image of Jerusalem and the Temple. Thus, the mountain on which the owl stands might be a visual interpretation of the idea expressed in that inscription.

The concept of redemption could be represented by another detail in that painting: branches on either side of the owl, topped by acorns or buds. Growth and buds might suggest the coming redemption, as found in the Ḥidushei Agadot of the Maharsha.36 Maharsha interpreted the expression “[…] the time of the singing of birds is come […]” (Song of Songs 2:12, KJV) as “the song of the Temple” (Maharsha, Ḥidushei Agadot, Ta’anit 3). When this is juxtaposed with the first part of the verse, “The flowers appear on the earth”, the image of blossoming is associated with the Temple. A blossom as representing redemption is also found in biblical prophecies of comfort, one of which declares: “The desert and the parched land will be glad, the wilderness will rejoice and blossom” (Isaiah 35:1, NIV), which talks about the return of the people of Israel to a flourishing land. It goes on: “Then will the eyes of the blind be opened […]” (Isaiah 35:5, NIV). It can be suggested that, since the Middle Ages, Jews have identified the term “the blind” with the image of “Jewish owls” depicted in Christian sources with their eyes closed, implying that they did not admit the light of Jesus. There might also have been an association with the blood libel that Jewish infants were born blind and had to drink Christian blood to acquire the ability to see.37 Perhaps as a response, the owls’ eyes drawn in each of the known Hebrew sources are not only wide open but are focusing their gaze on the viewer.38

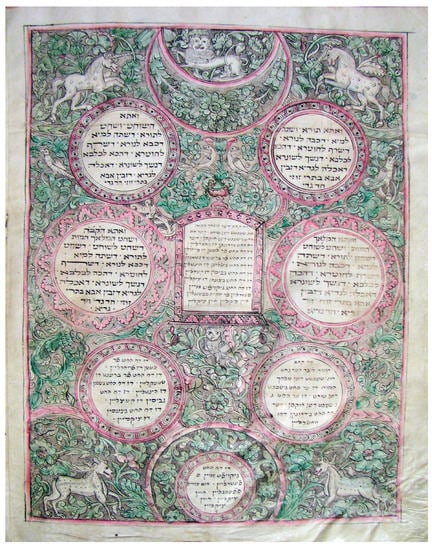

The design of the owl in the Unterlimpurg Synagogue was probably copied from depictions in contemporary sources in Franconia or Alsace: paintings in the Bechhofen or Horb synagogues (Figure 6)39 or a Passover haggadah created in Ihringen in 1732 (Figure 7).40 A comparison between the owls in the Unterlimpurg Synagogue and the other two synagogues and the haggadah reveals the same general features, notably the shape of the head and the tail. Clearly, then, the owls in the Unterlimpurg Synagogue and the haggadah probably share a messianic message as well. In the haggadah, this message is suggested in the illustration for the last verse of the piyyut Ḥad Gadya (fol. 26b, Figure 8). The painting includes zoomorphic motifs that have nothing to do with the literal meaning of the text: a lion, a pair of unicorns, four birds, two deer, and an owl. Animal pairs, such as birds may have been used to express the idea of the cherubim atop the Ark of the Covenant.41 Each of these animals may also represent the idea of God overseeing his people: owing to their ability to fly, birds may symbolize spiritual creatures and deer may represent God in the phrase: “My beloved is like a gazelle or a young stag. Look! There he stands behind our wall, gazing through the windows, peering through the lattice” (Song of Songs 2:9). The lion and the unicorn might stand for the two messiahs: the unicorn for Messiah Ben Yosef and the lion for Messiah Ben David.42 All of these animals symbolize the general idea of Ḥad Gadya: God’s providence in his world. Thus, similar to the rest of the painted animals on the page of the haggadah, the owl is also likely representative of a messianic idea or divine providence.

Figure 6.

An owl painting on a wooden panel. Horb, Synagogue, 1735. Jerusalem, The Israel Museum. Photograph: Zvi Orgad, 2017. Used by permission.

Figure 7.

An owl. “Passover Haggadah”, Ihringen, 1732; Jerusalem, The Israel Museum, Ms. 181/48, Fol. 26v. Used by permission.

Figure 8.

“Passover Haggadah”, Ihringen, 1732; Jerusalem, The Israel Museum, Ms. 181/48, Fol. 26v. Used by permission.

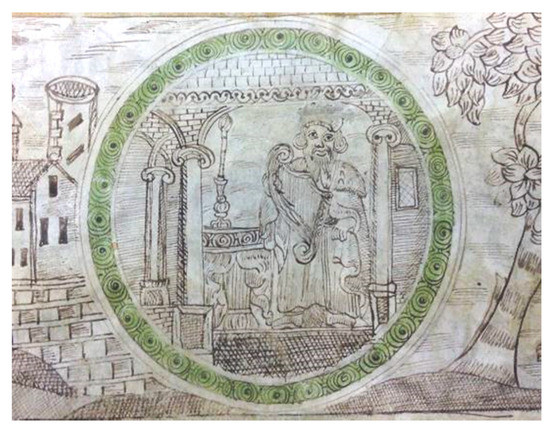

Another discernible detail in the Unterlimpurg Synagogue that might have been copied from an early modern haggadah is the ionic capital on which the owl stands. In a popular haggadah published in Amsterdam in 1695, the illustration of pillars with ionic capitals are a prominent component of King David’s palace. This depiction was probably the visual model for similar scenes painted in the Ihringen Haggadah, in which such capitals were depicted in three urban scenes—in two of them, King David is shown in his palace (Figure 9).43 Hence, the ionic capital in the owl painting in the Unterlimpurg Synagogue might also be a symbol for the king’s palace. Could it be, then, that the owl in the Unterlimpurg Synagogue was an embodiment of King David himself? This possibility should be seriously considered, as in the Book of Psalms, attributed to King David, the author compared himself to an owl: “I am like a desert owl, like an owl among the ruins” (Psalm 102:6, NIV). Moreover, the owl’s face, unlike its alleged visual models in the Horb Synagogue and Ihringen Haggadah, seems to have been deliberately stylized as a human face—with a nose instead of a beak and a smiling mouth.44 This human smile can perhaps be associated with depictions of King David in the Ihringen Haggadah (Figure 9 and Figure 10).45

Figure 9.

King David. Passover Haggadah”, Ihringen, 1732; Jerusalem, The Israel Museum, Ms. 181/48, Fol. 3r. Used by permission.

Figure 10.

King David. Passover Haggadah”, Ihringen, 1732; Jerusalem, The Israel Museum, Ms. 181/48, Fol. 22r. Used by permission.

Associating the owl with King David was presumably done to create a link with the Tikkun Ḥaẓot prayer. One reason for connecting the owl with the king’s Tikkun Ḥaẓot and redemption is the fact that it is a nocturnal bird. In the early modern period, especially in the eighteenth century, there was a resurgence of mysticism among Eastern and Central European Jewry.46 Jewish mysticism influenced the design, decoration, and inscriptions written on the walls of synagogues in Eastern Europe.47 This revival of mysticism was also a feature in some of the rural communities in today’s southern Germany, which saw intensive kabbalistic practice from the late seventeenth century on.48 Similar to Eastern European synagogues—where kabbalistic inscriptions and prayers were inscribed on the walls, kabbalistic prayers were also documented in Germany, for example, on the walls of the Bechhofen Synagogue.49 The Tikkun Ḥaẓot, which is an optional private prayer recited at midnight, was one of the common kabbalistic rituals in these communities.50 Comprising lamentations regarding the destruction of the Temple, it is ascribed to King David, whose image in the Zohar is a pillar of fire that leads the Jewish people to redemption.51 The Talmud associated praying at midnight with David based on the verse “At midnight I rise to give you thanks for your righteous laws” (Psalm 119:62 NIV). Similar to the Jerusalem Talmud, the Bavli cites the legend about the musical instrument that woke David at midnight. However, the latter links the king’s awakening to Torah study, which could be connected with Tikkun Ḥaẓot: “[…David] would immediately rise [from his bed] and study Torah until the first rays of dawn” (Bavli Berakhot 3b, [WDE–E]).

Jewish prayer books printed in German-speaking lands as early as the seventeenth century include Tikkun Ḥaẓot,52 so we can assume that it was also part of the liturgy there at that time as well. Some of these early modern prayer books from the German lands explicitly refer to King David as the author of the prayer. For example, a small booklet called Sefer Tikkun Ḥaẓot, printed in Frankfurt on the Oder in 1678–1679 mentions its attribution to King David more than once.53 The image of the owl might well be evidence of the practice of the prayer in the small Jewish community of Unterlimpurg. Another image on the Unterlimpurg Synagogue ceiling that possibly reinforces this suggestion is a depiction of a black rooster (Figure 11). According to the Zohar (Bereshit Vayeḥy), at midnight, when the northern wind blows, a flame hits the black rooster—which represents severe judgment—beneath its wing, causing it to crow. Sefer Tikkun Ḥaẓot includes two references to the black rooster as a means for waking up at midnight to pray. The first mention relates to the Zohar’s suggestion of keeping a black rooster at home for waking at midnight,54 and the second alludes to Rabbi Akiva, who kept a black rooster to wake him up at midnight, and recommends that the reader do the same.55 In the Unterlimpurg Synagogue, as in those in Eastern Europe, there were no inscriptions regarding Tikkun Ḥaẓot, perhaps owing to the optional private nature of this prayer,56 but the images of the owl and the black rooster might well imply the practice of this kabbalistic prayer.

Figure 11.

A black rooster, painting on a wooden panel. Unterlimpurg, Synagogue, 1738/9. Schwäbish Hall, Hälisch Fränkisches Museum. Photograph: Zvi Orgad, 2017. Used by permission.

5. Conclusions

In medieval and early modern Christian thought, the owl bore negative connotations, representing the evil Jew or other religious and national rivals, but, owing to the dearth of textual references, the owl’s status in the Jewish Ashkenazic world of these eras is less certain. Although, in the Bible, the owl was generally associated with destruction, a precise reading puts it in the right context—the destruction of Israel’s enemies—so it might actually have symbolized redemption. The three visual depictions of owls from the late Middle Ages and early modern period in Jewish sources that I discussed in this article tend to support this assumption and prove that this bird’s reputation might have been better then hitherto suggested. The positive attitude toward the owl evident in these paintings implies the embodiment of the Jewish people. Whereas its representation in the fifteenth-century Nürnberg Haggadah was probably a response to the notion that translating and printing the Bible in German was “stealing” it, the owl in the sixteenth-century Prague Haggadah is part of a wider scene implying Jewish hopes for redemption. The most complex depiction is found in the Unterlimpurg Synagogue, where additional motifs including an elevated platform, an ionic capital, and branches bearing buds may signify redemption by pointing to the increasingly popular Tikkun Ḥaẓot, which was recited to hasten the rebuilding of the Temple. Thus, this depiction is an outstanding example of the allegorizing methods employed by synagogue painters in the early modern period. This specific depiction of the owl might well be evidence of early modern religious ideas and developments in the small community of Unterlimpurg, which left no traces of its customs and liturgical practice except for some hints in the synagogue’s interior paintings. Moreover, whereas most studies relate to synagogue painters as interpreters of textual and visual sources, the intricate motif of the owl in the Unterlimpurg Synagogue suggests that its painter was an authentic narrator and storyteller in the cause of Jewish redemption.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Davidovitch, David. 1962. Haẓayar Eliezer-Zusman (Ben Haḥazan Shlomo Katz MiBrad) [The Painter Eliezer-Zusman (Son of the Cantor Shlomo Katz)]. Gazit 7–8: 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Elior, Rachel. 2014. Israel Ba’al Shem Tov and His Contemporaries: Kabbalists, Sabbatians, Hasidim and Mitnaggedim, I. Jerusalem: Carmel. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Marc Michael. 1997. Dreams of Subversion in Medieval Jewish Art and Literature. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haarmann, Julia. 2013. Hüter der Tradition: Erinnerung und Identität im Selbstzeugnis des Pinchas Katzenellenbogen (1691–1767). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Peter. 1998. The Virtues of Animals in Seventeenth-Century Thought. Journal of the History of Ideas 59: 463–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassig, Debra. 1995. Medieval Bestiaries: Text, Image, Ideology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, Brett D. 2010. This Earthly Stage: World and Stage in Late Medieval and Early Modern England. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, Elliott. 1989. Coffee, Coffeehouses and the Nocturnal Rituals of Early Modern Jewry. AJS Review 14: 17–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huberman, Ida. 1979. Painted Ceilings in the Wooden Synagogues in Southeastern Poland. Mater’s thesis, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Hubka, Thomas C. 2003. Resplendent Synagogue: Architecture and Worship in an Eighteenth-Century Polish Community. Hanover: Brandeis University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Irmscher, Christoph. 2011. Catesby’s Owl. Pacific Coast Philology 46: 153–76. [Google Scholar]

- Janson, Horst Waldemar. 1952. Apes and Ape Lore in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. London: The Warburg Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Kalonymus ben Kalonymus. 1873–1874. Seder Iggeret Ba’ale Ḥayyim. Vilnius: Yehudah Leib ben Eliezer Lipman. [Google Scholar]

- Klingender, Francis. 1971. Animals in Art and Thought to the End of the Middle Ages. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kogman-Appel, Katrin. 1993. The Second Nuremberg Haggadah: A Stylistic and Iconographic Analysis, I. Ph.D. dissertation, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Magid, Shaul. 1996. Conjugal Union, Mourning and “Talmud Torah” in R. Isaac Luria’s “Tikkun Hazot”. Daat: A Journal of Jewish Philosophy and Kabbalah 36: XVII–XLV. [Google Scholar]

- Mellinkoff, Ruth. 1970. The Horned Moses in Medieval Art and Thought. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mellinkoff, Ruth. 1974. The Round-Topped Tablets of Law: Sacred Symbol and Emblem of Evil. Journal of Jewish Art 1: 28–43. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki, Mariko. 1999. Misericord Owls and Medieval Anti-Semitism. In The Mark of the Beast: The Medieval Bestiary in Art, Life, and Literature. Edited by Dabra Hassig. New York: Garland, pp. 23–49. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan Neta ben Moshe Hanover. 1690. Sefer Sha’arei Ẓion. Dührn-Port: Shabtai Bas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Orgad, Zvi. 2017. Eliezer-Zusman: An Eighteenth-Century Synagogue Painter at Work. Ph.D. dissertation, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Panter, Armin. 2015. Die Haller Synagogen Des Elieser Sussmann Im Kontext der Sammlung des Hällisch-Fränkisches Museums. Künzelsau: Swiridoff. [Google Scholar]

- Shadmi, Tamar. 2011. Wall Inscriptions in East European Synagogues—Their Sources, Meanings, and Role in Shaping the Concept of Space and Worship. Ph.D. dissertation, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Tabori, Joseph. 1987. The Art of Printing and the Illustrations in the Prague Haggadah. Ohev Sefer 1: 13–21. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Toeplitz, Erich. 1923. Wall Paintings in Synagogues of the 17th and 18th Centuries. Rimon 3: 1–8. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Wengrov, Charles. 1967. Haggadah and Woodcut: An Introduction to the Passover Haggadah Completed by Gershom Cohen in Prague, Sunday, 26 Teveth, 5287 (Dec. 30, 1526). New York: Shulsinger Bros. [Google Scholar]

- Wischnitzer-Bernstein, Rachel. 1935. Symbole und Gestalten der Jüdischen Kunst. Berlin: Siegfried Scholem. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, Martha. 1982. Some Manuscript Sources for the Playing-Card Master’s Number Cards. The Art Bulletin 64: 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaniv, Bracha. 1999. The Cherubim on Torah Ark Valances. Assaph 4: 155–70. [Google Scholar]

- Yosef ben Shlomo from Poznań. 1678–1679. Sefer Tikkun Ḥaẓot. Frankfurt on the Oder. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The discussion about the symbolism of Jewish art is well rooted in twentieth-century Jewish scholarship. See, for example, (Wischnitzer-Bernstein 1935, pp. 71–89; Epstein 1997). On the symbolism of zoomorphic motifs in synagogues, see (Huberman 1979, pp. 52–65; Hubka 2003, pp. 95–103). |

| 2 | The present study located barely a handful of owl depictions in Hebrew medieval illuminated manuscripts. |

| 3 | The absence of documented owl depictions in eighteenth-century Polish synagogues might be due to the sparsity of remnants and photographs from these sites. However, it is also possible is that the owl was a unique motif in the Franconia region of the early modern period. |

| 4 | In Isaiah (34:11, New International Version [NIV]), three nocturnal birds are described as inhabiting deserted places and symbols of destruction: the desert owl [Hebrew: ka’at], the screech owl [kipod], and the great owl [yanshuf]. The desert owl and screech owl are also mentioned in the same context in Zephaniah 2:13–14. According to Rashi, the “kipod”, which he calls “kifofa” (translated as “great owl”), is a nocturnal bird: “Karya [little owl] and kifofa—birds that cry at night and their faces resemble those of a cat with their eyes in front” (Bavli Niddah 23a, William Davidson Edition–English [WDE–E]). The kipod and kifofa were mentioned in phrases that mark their oddness: “[…] One who sees an elephant, a monkey, or a vulture [Rashi: “Kifof”] recites: Blessed… Who makes creatures different” (Bavli Berachot 58b, WDE–E); “All types of animals are auspicious [signs] for a dream except for an elephant, a monkey and a long-tailed ape [Hebrew: “kipod”]” (Bavli Berakhot 57:2, WDE–E). These verses refer to humans or strange animals that astonish their viewers. The resemblance between the faces of nocturnal birds and human beings, especially in the shape of the jaws (Tosfot Chulin 62:2) or the cheeks (Sefer Mitzvot Gadol 59–62) is the cause of this astonishment. Tosfot (Chulin 63:1) specified three different nocturnal birds according to the phrase “Abaye says: Ba’ut among birds kifof”. Accordingly, “Ba’ut” is the barn owl [Hebrew: “Tinshemet”], while “karya” and “kifof” refer to the desert owl [Hebrew: “kos”] or the owl [Hebrew: “yanshuf”]. Medieval Hebrew sources also used several different names to describe nocturnal birds of prey. For example, in the Iggeret Ba’ale Hayyim, translated from Arabic to Hebrew by Kalonymus ben Kalonymus in the thirteenth century, there are at least two names of nocturnal raptors: the Athene [kos] and owl [yanshuf]. See (Kalonymus ben Kalonymus 1873–1874, p. 24a). In medieval Christian bestiary and aviary literature, nocturnal raptors such as the nycticorax, noctua, bubo, and ulula were discussed. See (Miyazaki 1999, p. 27). All these birds were portrayed similarly in the miniatures that accompanied the texts. |

| 5 | See, e.g., Abarbanel on Isaiah 32:10: “[…] the sages received that the soul of Esau was reincarnated into the soul of Jesus from Nazareth […] and perhaps it is called Jeshua [ישוע], a name that is comprised of the same letters of the name “Esau [עשיו]”. And hence, all believers of his religion and faith should have been called the sons of Edom, because Jesus is Esau and Esau is Edom […]”. |

| 6 | See also Shemot Raba, Vaera 9:13, and Psikta Rabbati Piska 17. |

| 7 | On this haggadah, see (Wengrov 1967). |

| 8 | For a comprehensive analysis of the paintings of human figures and narrative scenes, see (Tabori 1987). |

| 9 | Tabori focused on technical aspects relating to the illustrated initial words and their distribution (ibid., p. 14). |

| 10 | See (ibid., pp. 17–18). |

| 11 | The owl was not the only animal that medieval Jews identified with positive “Jewish traits” in response to its “negative Jewish traits” in Christians texts. According to Epstein, Christians identified the hare, as well as a group of other animals, including the hyena and the weasel, as animals that are involved in strange and incomprehensible sexual activity and thus symbolize sexual hypocrisy. This hypocrisy was associated with homosexuality, which was also considered immoral. Christians in the Middle Ages also suspected Jews of possessing ‘moral hypocrisy’. It was this comparison that may have led Christians to identify Jews with hares. In response, the Jewish minority not only accepted the image imposed on them but embraced it. See (Epstein 1997, p. 27). Jews could emphasize the positive aspects of the hare—an intelligent and cunning animal—that is capable of hiding from its enemies (ibid.). |

| 12 | See (Miyazaki 1999, p. 27; Mellinkoff 1974, p. 39). |

| 13 | See (Hirsch 2010, p. 137). On the spread of the image of horned Moses in medieval Europe, including German lands, see (Mellinkoff 1970, pp. 69–75, Figure 80: Speculum Humanae Salvationis, Weißenau, 14th century; Kremsmünster, Stiftsbibliothek, Codex Cremifanensis 243, fol. 21v and Figure 81: Biblia Pauperum, Nördlingen, 1471; Munich, Bavarian State Library, fol. 18v). Images of Moses with two horns or two beams of light were painted by Jewish scribes and painters in early eighteenth-century illuminated manuscripts. See, e.g., Yaakov ben Yehudah Leib Shamash of Berlin, Seder Tikkun Sabbath, Hamburg, 1730; Amsterdam Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana, Ros 661, fol 1r, and Yaakov ben Yehudah Leib Shamash of Berlin, Psalm Book, Hamburg, 1721; Amsterdam, Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana, Ros 533, fol 1r. For more about the “Jewish” characteristics of the owl in medieval bestiaries, see (Hassig 1995, pp. 97–98). |

| 14 | See (Mellinkoff 1970, pp. 135–36, Figures 127 and 128). |

| 15 | See (Janson 1952, p. 178). |

| 16 | “Second Nürnberg Haggadah”, Germany, 15th Century; London, David Sofer Collection, Nuernberg MUS 2121 (formerly). |

| 17 | On the iconography of this scene, see (Kogman-Appel 1993, pp. 122–24). |

| 18 | In Jewish tradition, the people of Israel and the Torah married on the festival of Shavuot. See, for example, Shemot Rabbah (33:7) on the verse, “Moses gave us the LORD’s instruction, the special possession […]” (Exodus 33:7). The Midrash proposes to read the word “possession”, in Hebrew “morasha”, as the Hebrew word “me’orasa”, which means “engaged”. Therefore, it interprets the verse as an engagement between the people of Israel (the bridegroom) and the Torah (the bride). |

| 19 | Rashi explained the phrase “If you had not plowed with my heifer” as “if you had not questioned my wife”. |

| 20 | In 1466, the Mentelin Bible was published in Germany for the first time. It was later reprinted thirteen times. In about 1475, the illustrated Zainer Bible was published. It was reprinted in 1477. |

| 21 | See (Wolff 1982, p. 591). Katrin Kogman-Appel pointed to the resemblance between animals painted by the Master of the Playing Cards and in the Yehudah and Second Nürnberg haggadot, made in the second half of the fifteenth century. Kogman-Appel suggested that these cards may have been used by the painters of these two haggadot, perhaps indirectly, as visual models. See (Kogman-Appel 1993, pp. 173–77). |

| 22 | The image of three small birds attacking an owl appears, for example, in a thirteenth-century English illuminated bestiary (Bestiary, England, second quarter of the thirteenth century; London, British Library, MS. Harley 4751, fol. 47r). The painter described each of the small birds in a distinct design and posture that gave them individual personalities. In contrast, the owl was depicted as a large, awkward figure with a blank gaze. A similar scene of three birds assaulting an owl was painted in Bestiary, England, 1225–50; Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Bodley 764, fol. 73v (See also Miyazaki 1999, p. 28) and in “The Queen Mary Psalter”, England, 1310–20; London, British Library, Royal MS 2 B. vii, fol. 129r. The number of birds assaulting an owl in medieval Christian art was not fixed: a scene of two birds attacking an owl can be seen in “The Queen Mary Psalter”, fol. 128v. Five birds attacking an owl were carved under a misericord in the late fourteenth century in Norwich Cathedral, Norwich, England. |

| 23 | In the early modern period, as in Classical antiquity, the owl could be also connected to Athena and symbolize wisdom. See (Hirsch 2010, pp. 138–39). However, this interpretation is irrelevant to the owls referred to in this article. |

| 24 | Gradual, Germany, Nuremberg, 1507–1510; New York, The Morgan Library, MS M.905 II, fol. 145r. |

| 25 | Gradual, Germany, Nuremberg, 1507–1510; New York, NY, The Morgan Library, MS M.905 I, fol. 38v. |

| 26 | See (Hirsch 2010, pp. 131–33, 170). The owl as representing negative features, not necessarily Jewish, was mentioned as early as in the Parables—an English fable book, published in 1219. See (Klingender 1971, pp. 363–64). |

| 27 | See (ibid., pp. 162–63, note 118). |

| 28 | See (Harrison 1998, pp. 479–81). |

| 29 | On Mark Catesby’s Natural History of Carolina, Florida & the Bahama Islands, which contains information about the owl’s flying abilities (the information was acquired in 1723), see (Irmscher 2011, pp. 153–56). |

| 30 | See (Harrison 1998, p. 467). |

| 31 | There is much more evidence that synagogue painters generally remained faithful to medieval visual sources. For example, they used the medieval square letter type that was typical of medieval Ashkenazic illuminated manuscripts as opposed to the shift of Hebrew manuscript illuminators to the Amsterdam letter type that was widely used in printed books in the early modern period. See (Orgad 2017, pp. 70–71). |

| 32 | Eliezer-Zusman was a well-known master craftsman in Franconia in the first half of the eighteenth century. He signed the paintings of the Bechhofen, Horb, and Kirchheim synagogues, all of them in the vicinity of the Unterlimpurg Synagogue. The stylistic similarities indicate that the painter of the Unterlimpurg Synagogue was part of the school of craftsmen founded by Eliezer-Zusman. He may have been an apprentice or worked under Eliezer-Zusman’s supervision before painting the Unterlimpurg Synagogue’s interior. Hence, he was probably familiar both with Eliezer-Zusman’s style and the liturgical themes he featured. See (ibid., pp. 306–07). |

| 33 | In synagogues in Eastern Europe, vaulted symmetrical constructions with two towers were painted on elephants’ backs, probably to resemble contemporary conventional depictions of the Jerusalem Temple. See (Orgad 2017, pp. 79–80). In the Bechhofen Synagogue, Eliezer-Zusman painted a different kind of construction representing the Temple: a multistory residence with a large gate in front—very much like the house on the elephant’s back in the Horb Synagogue. Thus, this construction apparently represents the Temple as well. See (ibid., pp. 196–97). The painter of the Unterlimpurg Synagogue probably found this design not clear or convincing enough as a depiction of the Temple and sought to rely on other visual models of a domed castle with two towers, which originated in Eastern Europe. |

| 34 | In the first half of the eighteenth century, human figures were often implied by depicting hands in various positions and actions. Therefore, the painter of the Unterlimpurg Synagogue could not paint human figures there, nor could he paint a crown on the owl’s head—a motif that was only used in synagogues for the Torah crown or the double-headed eagle (conspicuously, all the crowns in the 1732 Ihringen Haggadah were erased—perhaps for the same reason. See, for example, Figures 9 and 10). In depicting human figures as animals, he probably did not rely on medieval paintings in Passover haggadot in which Jews were imaged with animal heads. However, he might have followed Eliezer-Zusman’s anthropomorphized figures in the Horb Synagogue, allegedly representing some of the Jewish community leaders. See (Toeplitz 1923, p. 7). |

| 35 | According to a dating inscription in the Unterlimpurg Synagogue, the ornamentation was completed in the Hebrew year 5499, (1738 or 1739). See (Panter 2015, p. 83). According to various studies, the work on the interior painting of the Kirchheim Synagogue ended in the Hebrew year 5500 (1739 or 1740). See (Orgad 2017, p. 169). |

| 36 | Rabbi Shmuel Eliezer Halevi Idles—rabbi in Chelm and Ostroh between sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. |

| 37 | See (Miyazaki 1999, p. 30). |

| 38 | It should be noted that of all the paintings in the Unterlimpurg Synagogue, only a lion, a hare, and the owl are imaged gazing at the viewer. The first two are identified with the Jewish people: the lion might represent the tribe of Judah or Messiah ben David, and the hare might symbolize Jacob and the people of Israel; painting the owl in the same way suggests that the painter had a similar intention. |

| 39 | According to the documented signatures of Eliezer-Zusman, the decoration of the Bechhofen Synagogue was completed in 1732, while the interior of the Horb Synagogue was painted in 1735. See (Orgad 2017, pp. 167–69). Depiction of an owl from the Bechhofen Synagogue, which was designed similarly to the owl in Horb, was copied by Yosef Valersteiner. See (Davidovitch 1962, p. 15). |

| 40 | Passover Haggadah, Ihringen, 1732; Jerusalem, The Israel Museum, Ms. 181/48. Similar to other early modern haggadot, the 1732 Ihringen Haggadah includes narrative scenes copied from the Amsteradam Haggadah. However, in contrast to most other early modern haggadot, some of its paintings share the medieval symbolic attitude of contemporary synagogue painting, especially in the variety of zoomorphic motifs painted outside the narrative scenes, sometimes in heraldic pairs. Moreover, this haggadah’s paintings are very similar in style and motifs to those in the synagogues of Bechhofen and Horb. Therefore, it is possible that Eliezer-Zusman—and his co-worker in the Unterlimpurg Synagogue—were familiar with the paintings in this haggadah. There is evidence of direct copying from the Ihringen Haggadah to the wall of the Unterlimpurg Synagogue without the intermediation of other synagogue paintings in Franconia in the depiction of Jerusalem: a tower appears in both the haggadah and the Unterlimpurg Synagogue (see Panter 2015, p. 86) with an identical column of bricks on its left side (Figure 9, left to the border), whereas in Horb, the same construction was painted without this element. According to the photographed documentation, this construction was not included in the depictions of Jerusalem in the Bechhofen and Kirchheim synagogues. |

| 41 | See (Yaniv 1999, p. 158). |

| 42 | See (Epstein 1997, pp. 97–112). |

| 43 | As in the Ihringen Haggadah, in many other Passover haggadot dating back to the late seventeenth century in German lands, such capitals were depicted in urban scenes, mostly ones in which King David is shown in his palace kneeling before God. For example, “NL Joseph Leipnik Haggadah”, Darmstadt, 1733; Jerusalem, National Library of Israel, NL Ms. Heb. 8º983, fol 14v. “Copenhagen Haggadah”, Hamburg-Altona, 1739; Copenhagen, Det Kongelige Bibliothek, Ms. 9, fol 24. “Hayyim of Kittsee IM Haggadah”, Vienna, 1748; Jerusalem, The Israel Museum, Ms. 181/53, fol 14v. |

| 44 | Depictions of owls with typical “Jewish” faces were common in medieval Christian art. In these cases, the owls were painted with grotesque features such as a crooked nose. See (Hirsch 2010, p. 146; Miyazaki 1999, p. 28). |

| 45 | Both depictions of King David in the Ihringen Haggadah are framed in round borders reminiscent of the border of the owl on the Unterlimpurg Synagogue ceiling. Similar to the owl, in both depictions, King David’s face is viewed from the front. In the first painting, David stands on a raised platform between three pillars topped by ionic capitals (Figure 9). To his left is a candle, which indicates that the whole scene takes place at night. Nighttime relates to the legend quoted in the Jerusalem Talmud: “A violin was hung against David’s windows, a north wind was blowing at night and waving it, and it was playing by itself” (Yerushalmi, Berachot 2:5). It can also be associated with the owl. |

| 46 | On the development in Jewish mysticism up to the first half of the eighteenth century in the context of Israel Ba’al Shem Tov’s doctrine, see (Elior 2014, pp. 545–607). On the inclusion of kabbalistic prayers in Eastern European prayer books, see (Shadmi 2011, p. 95). |

| 47 | See (Hubka 2003, pp. 140–165; Shadmi 2011, pp. 95–97). |

| 48 | One prominent example is the study of Kabbalah in Fürth since the end of the seventeenth century. See (Haarmann 2013, pp. 43–44). |

| 49 | See (Shadmi 2011, pp. 101–02). |

| 50 | Evidence for the popularity of this prayer in Eastern Europe is its prevalence in printed prayer and kabbalistic books printed since the seventeenth century, e.g., (Nathan Neta ben Moshe Hanover 1690). See also (Huberman 1979, pp. 14–15). |

| 51 | See (Magid 1996, pp. XXIV–XXV). |

| 52 | The Shulḥan Arukh Ha’ari, printed in Frankfurt on the Main in 1691, mentioned a custom of getting up at midnight and studying Torah shortly after prayer, then returning to sleep and getting up about half an hour before sunrise for further study. This custom, which enabled even people who found it hard to stay awake all night to practice Tikkun Ḥaẓot, demonstrated the popularity of this prayer in Frankfurt at the end of the seventeenth century. See (Horowitz 1989, pp. 26–27, note 28). |

| 53 | See (Yosef ben Shlomo from Poznań 1678–1679), pp. 15, 17, 20. |

| 54 | See (ibid., p. 2). |

| 55 | See (ibid., p. 21). |

| 56 | One of the kabbalistic inscriptions on the walls of Moravian and Franconian synagogues, including the one in Unterlimpurg, was Ledavid Mizmor. The most common usage of this psalm during prayer is when returning the Torah scroll into the Torah ark, on weekdays and holidays that do not fall on Shabbat, but it is also included in the Tikkun Ḥaẓot. According to Huberman, the Tikkun Ḥaẓot prayer was included in the liturgy in southeastern Polish synagogues in the eighteenth century. See (Huberman 1979, p. 15). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).