1. Introduction

Writing during the millennium, not long after the installation in Gateshead of Antony Gormley’s monumental sculpture,

The Angel of the North, artist and publisher Simon Cutts criticised the dominance of monumentalism within the field of public art. Decrying the lack of critical engagement offered by public sculptures, which, as “pejoratively valuable objects”, litter the world “like Mount Everest is littered with Coke cans” (

Cutts 2007, p. 87), he called for an alternative approach to public art, which prioritises the production of “metaphorical space” (ibid.) over physical form. Almost two decades later, it could be argued that mainstream understandings of public art have expanded beyond monumental sculpture to incorporate approaches that focus on process rather than product. Indeed, the commissioning of ephemeral artforms, such as performance, sound art, digital art and what is commonly referred to as socially engaged practice, has largely overtaken the installation of permanent sculpture, in part due to its prohibitive cost in today’s economic climate.

Within this milieu, the artist’s book has come to occupy a significant role within the production, dissemination and interpretation of public art. As the curators of

In Certain Places—a long-term public art project based in the city of Preston

1—we have, over the last few years, witnessed a growing trend amongst artists of producing publications as an integral part of their commission. For many, this is a temporal strategy, which, through the documentation of the artworks’ processes, realisation and reception, provides a legacy for an otherwise temporary project. For others, it offers a critical space in which to further explore the context and thematic content of their work, often through the invited contributions of specialists in other fields. As physical artefacts, books allow artists to connect with their audiences at the level of individuals, serving simultaneously as souvenirs for those who have experienced the work and as proxy artworks for those who have not. For certain artists, therefore, the artist’s book’s critical and communicative functions supplant the need for other creative outputs, and publications have also been produced as public artworks in their own right.

In the following text, we explore these trends through reference to specific artists’ books, which have been produced as, or as part of, public artworks. Within this context, public art serves as a broad definition to describe a range of place-based practices. This includes artworks that are created for, or in response to, specific locations, as well as those that explore more universal aspects of place. In each case, the “publicness” of the work relates to its existence, either exclusively or in part, outside of traditional gallery-based models of production and dissemination. In employing the term, we also acknowledge the lack of clarity that exists around public art as a discipline. As Cameron Cartiere and Shelly Willis point out, public art is an elusive and ambiguous practice, which “weaves in and around itself, existing in layers” (

Cartiere and Willis 2008, p. 9). As a result, “since

public art was coined as a term” over fifty years ago, “it has yet to be clearly defined in any art history text” (ibid., p. 8). However, despite, or, perhaps, due to such ambiguity, we regard it as a useful shorthand to describe the type of place-focussed, interdisciplinary and multi-sited projects that characterise our joint curatorial practice.

As a curatorial partnership, In Certain Places brings together our individual perspectives and professional concerns through a jointly authored project. In the same way, the following essay reflects our personal areas of interest in relation to artists’ books. In the first section, Charles Quick provides an art historical context, which locates the roots of the relationship between artists’ books and public art within the emergence of site-specific practice during the 1960s and 1970s. Central to this is the use of photography as a medium for documenting both the creative processes and the final outcomes of public art projects. He then goes on to examine the various roles that artists’ books play in connection to specific public artworks. Following this, Elaine Speight examines the status of the artist’s book as an autonomous public artwork. Focussing on the work of three artists from the North of England, she argues that, as interactive and sensory objects, artists’ books provide the ideal medium for creative explorations of place. Through these dual accounts, we aim to demonstrate that, far from ancillary artefacts, artists’ books play a pivotal role within the production of public art. Moreover, as accessible and democratic objects, they allow artists to express their ideas and connect with audiences outside of institutional boundaries. In this way, artists’ books offer an antidote to the popular view of public art as municipal decoration, by presenting it as an experimental, creative and, above all, critical practice.

2. The Artist’s Book in Public Art

The artist’s book as a format has been embraced by artists interested in many different approaches to public art. These publications have allowed them to take on the role of editor, designer and publisher. Through their lens, research, development and implementation have been captured, historical narratives created, and architectural alternatives or substitutes produced, which capture the essence of public art works in a different format. Almost without exception, artists’ books rely on photography to illustrate works and convey concepts.

With the arrival of digital printing, accessible design software and readily available ISBN numbers, the artist now has the ability to design a lasting record of a project, no matter how large, small, fleeting or long lasting. All new publications with an ISBN number are lodged with the British Library. The Special Collections at Manchester Metropolitan University and the library collections at Henry Moore Institute also collect artist publications, including those of other institutions, such as Tate Britain. All this provides a plethora of ephemeral public art projects archived for posterity and available to the committed researcher and wider public.

The arrival of photography as an accessible medium has enabled artists to explore and explain their ideas and concepts to a wider audience. There has been a relationship between the artist’s book and the more traditional forms of sculpture and public art since the early days of photography. Artist Man Ray assisted sculptor Brancusi in setting up his darkroom in Paris in 1921. His black and white photographs now form an important archive not only of his work, but also of the way he perceived and viewed it in his studio. The images documented the different arrangements of his sculptures over time in the specific location of his studio, as well as their appearance in different light. It was a very precise study of objects in a place and time. It also enabled him to transport his ideas and visions to new audiences in New York without the weight of the stone in his luggage.

Some 40 years later, artists were investigating the creation of art for sites and places known at the time as site-specific works. This refers to art intended specifically for a particular location and that had an interrelationship with that place. Its meaning and often its context relied on the site; the two could not be separated. Works were installed in situ and could be temporary in nature. This can be viewed as the beginning of an expanded public art practice with photography as the essential medium to record and document, as well as communicate the concepts. The term public art was not commonly used then, but unquestionably, artists were examining and using spaces outside the gallery as a site for making works, even if the documentation was later shown in the gallery. Richard Long’s A line made by walking (1967) is a prime example, created while he was a student at St Martin’s School of Art in London. This formative work is a black and white photograph showing a line that has been created in a field of grass by walking back and forth, with its title underneath.

At the same time, Peter Downsbrough was beginning to produce his version of artists’ books, eventually going on to create over 120. He could be considered a conceptional artist who mainly created minimalist sculptures with an interest in placing the works in a location, exploring the viewers’ relationship to their surroundings and the installations. For some artists working in public spaces, the artist’s book becomes the primary work. The temporary interventions and special arrangements recorded by photography are, in a few cases, meant to be experienced only via the publication. Two Pipes Fourteen Locations (1974) is one of his early books and the first that uses photography. It encompasses 63 photographs on 80 pages. A table of contents at the beginning of the book catalogues all 14 locations, distributed across the world. Detailed measurements are included of the black gas pipes used in every location. Each installation of the pipes is photographed from different viewpoints—it is up to the reader to work out what they are looking at. To turn the pages is to visit 14 worldwide sites without leaving the comfort of your armchair, remaining there as long as you like.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude recognised that it was necessary to document and capture not only the final work—installations, wrapped buildings, floating islands—through the medium of photography but equally to tell the story from their viewpoint and in their own words. They recorded the permissions, the court cases, the timeline, the battles to gain permission and how they persuaded communities to engage with and support their projects, often over years. This aspect is deemed to be equally critical by the artists as the installed work, which is often presented through photography and proposal drawings taken from a bird’s eye view, as if we are flying over the site. Publications were almost without exception produced in partnership with other organisations, institutions and publishers but with the sense of tight artist editorial control. Artists’ books, including the photographs and films, become the lasting essence of the work, outlasting the actual, on-the-ground experience. When you read the Christo: Surrounding Islands (Christo, 1984) publication, launched after the project, you view a combination of aerial perspective colour photographs and drawings of proposals, interspersed with black and white photographs of the artists working at ground level. These document the different aspects of the process, meetings, looking at maps, court cases and the installation. Detailed text by Werner Spies covers every aspect of the process that leads to the final realisation of the project. The work is positioned within a wider context of public art, particularly land art of the USA, all framed within a soft critical response by the writer. The result is a carefully choregraphed book that becomes the experience of the work for a significantly larger secondary audience, far outnumbering the people who actually witnessed the temporary installation lasting intentionally for only two weeks. In reality, as Werner Spies points out in the text, not many people did see the work from the sky, as presented in the artist’s book, which was only possible to a few who could afford to travel in a helicopter over the site. In this way, the publication goes some way to democratise the work, albeit in a way that lacks the immediacy and embodied experience of first-hand encounters with it.

Christo and Jeanne Claude’s books are still the template for presenting an artist-initiated temporary public art project.

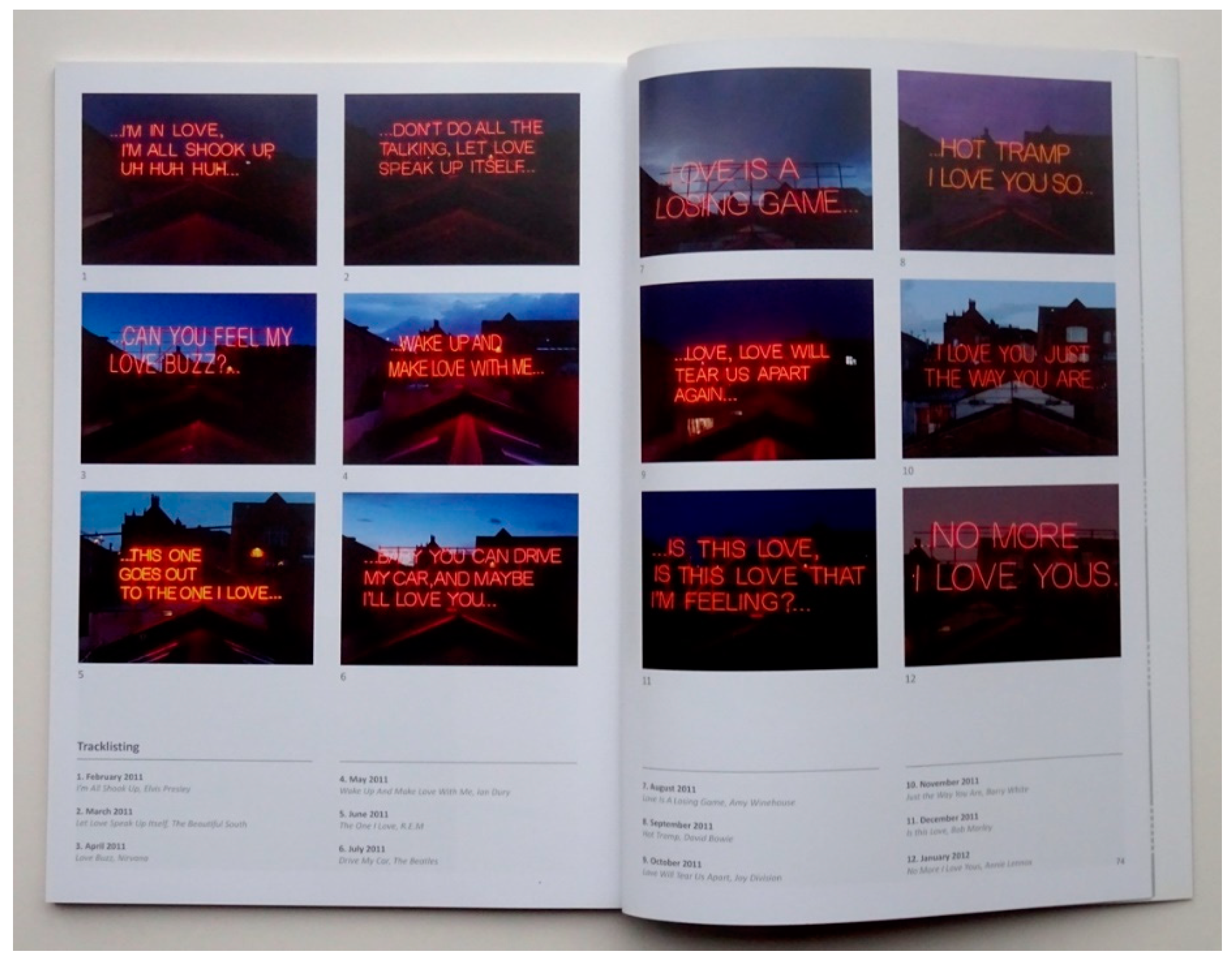

12 Months of Neon Love (2011) (

Figure 1) by Victoria Lucas and Richard William Wheater was just such a project. Over twelve months in 2011, they installed twelve different large, red, neon signs, one after the other, portraying love using song lyrics on a rooftop in Wakefield, seen by rail travellers on the main line from Kings Cross, London, to the north of the UK and engaging the inhabitants of the city.

The larger than A4, full colour, soft backed publication, 12 Months of Neon Love 2011 (2012), allows the colour images to illustrate the story, with texts by the artists, Jasmin Patel and Sheila McGregor, who, between them, map out the narrative within a critical context. This was a project that had to gain permission and raise funds as well as create and install the work. Many of the photographs are taken from vantage points that the public audience would not have had access to, some visually explaining the different processes and aspects of the work. This is a self-published limited edition of 365, the number of days in the year and the length of the project. A double-page spread acts as a calendar, showing all twelve song lyrics, one for each month.

Unlike exhibition catalogues, which are published by public and private galleries, publications such as those of Christo and Jeanne-Claude and Lucas and Wheater tend to be produced independently of cultural institutions and serve a different function. In particular, where exhibition catalogues generally consist of photographic documentation of a body of work, usually alongside one or more contextual essays, artists’ publications focus on one project in great detail. As well as documenting the completed artwork, such publications also allow the reader “behind the scenes” by revealing the complex intricacies of the processes involved in producing and installing the work. The potential readership for artists’ publications is also wider than that of exhibition catalogues, as they tend to be distributed through high street book shops, online book sellers such as Amazon, artists’ websites and public libraries, rather than a gallery’s shop. Many are also held in specialist collections, such as the artists’ books section of the Special Collections Library at Manchester Metropolitan University and the library collections at the Henry Moore Institute. These collections are accessible by appointment and free of charge to the general public, reinforcing the public nature of the work and, in some ways, further democratising access to the projects. Nevertheless, it is important to note that whilst audiences may encounter publicly sited artworks as part of their everyday lives and movements within a place, chance encounters with artists’ books are likely to occur only in cultural contexts, such as libraries, museum collections and artists’ book fairs. As a result, audiences tend to be self-selecting and made up of people with a pre-existing interest in a particular artist, artwork or area of art practice.

Most public art projects have extended lead-in times, complex discussions and technical concerns, requiring the involvement of other professionals. These aspects combine to produce an activity that can have just as much significance as the finished work for the artist and people involved. Certain artist practices value the engagement with all its twists and turns.

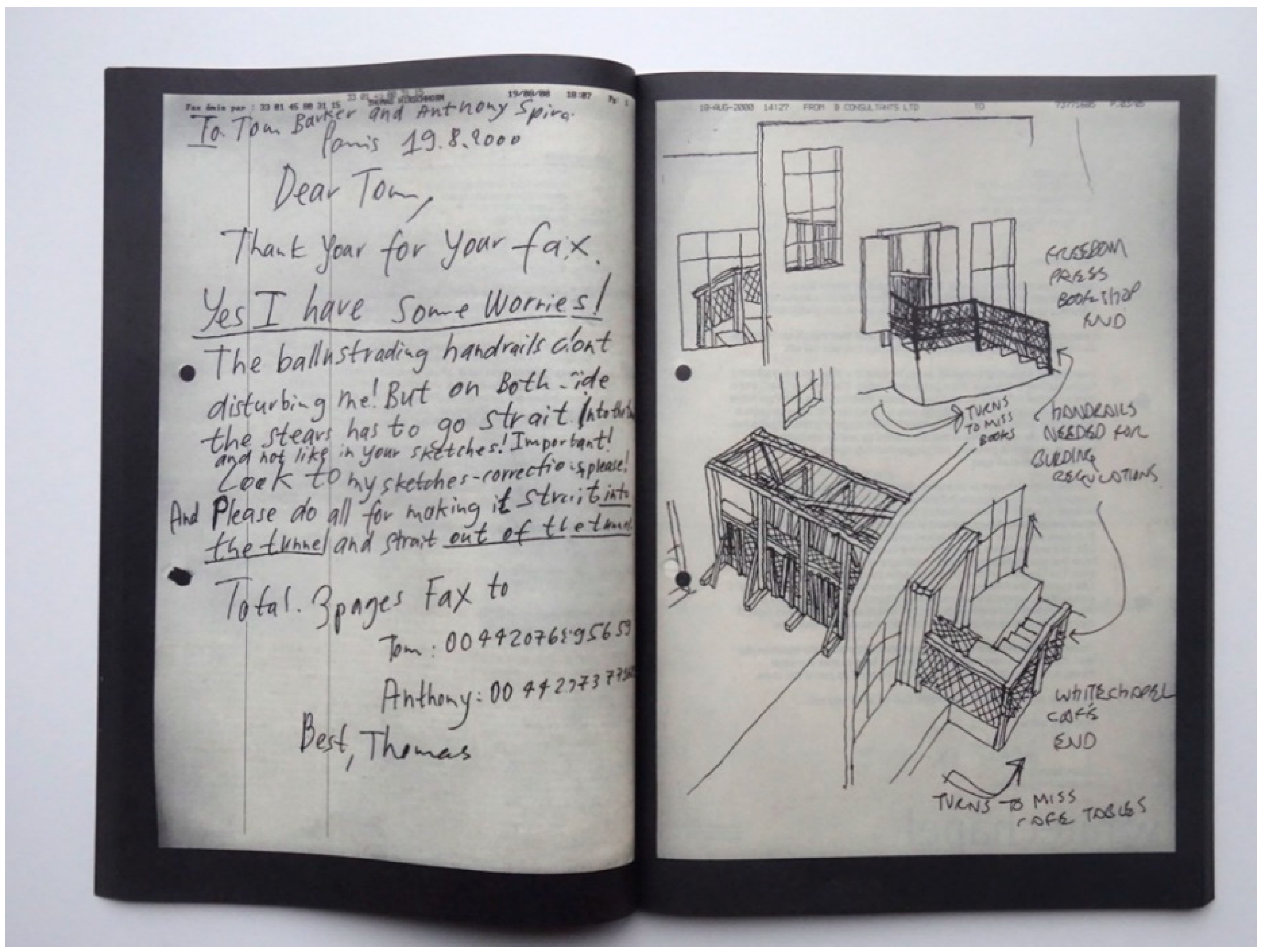

Material The Public Works–The Bridge 2000 (

Hirschhorn 2001), co-published by Bookworks and Whitechapel Art Gallery, is an assemblage of the material generated by just such a project.

The Bridge was an impermanent construction at first-floor level between the Freedom Press anarchist bookshop and the Whitechapel Gallery Café next door. Thomas Hirschhorn covered the structurally sound bridge in his trademark tape and plastic bags, thus contributing to its DIY cave-like appearance, a portal from which to pass from one world to another. What makes this book distinctive from the ones of Christo and Jeanne Claude and Lucas and Wheater is its determination to reveal the unedited correspondence amongst the numerous parties, throughout the duration of the lead-up to the installation and beyond. It places positive and negative emails, alongside engineer and artist drawings and handwritten responses from the artist in French and English, interspersed with images of the construction in process, planning documents from Tower Hamlets council, financial budgets and interviews with the participants and others (

Figure 2).

It is a very open and honest record of the discords that are part of a work of this nature.

Craig Martin from Bookworks describes the publication as “going beyond the work’s original architectural intention, the book is an attempt to extend this into social relations” (

Hirschhorn 2001). The artist’s book captures the dialogues of these social relations, not in a prefabricated timeline but, rather, a representation of the disordered discourse joining many distinct parties and voices.

Claire Bishop (

2011, p. 265) talks about Hirschhorn’s methods as “a montage principal of co-existing incompatibilities”. The development of the project definitely supports that view and is evidenced by this artist’s book. Furthermore, to emphasise the anarchic process and to try and find a place for this publication, it chooses to reference material you might hope to find in the Freedom Press bookshop to which the bridge was connected. The soft cover book is printed with black ink on A4, thin, yellowed newsprint. The design used the paper size of the digital correspondence, while the photocopy aesthetic reflected the material to be found in the anarchist bookshop. Many of the 200 pages showed the original ring binder holes or slide pockets from the archival material. This was not a catalogue to accompany

The Bridge 2000 (2000). It was produced after the undertaking had finished, as a way of recording the practice as well as reflecting the place of activity and encompassing the gritty aesthetic.

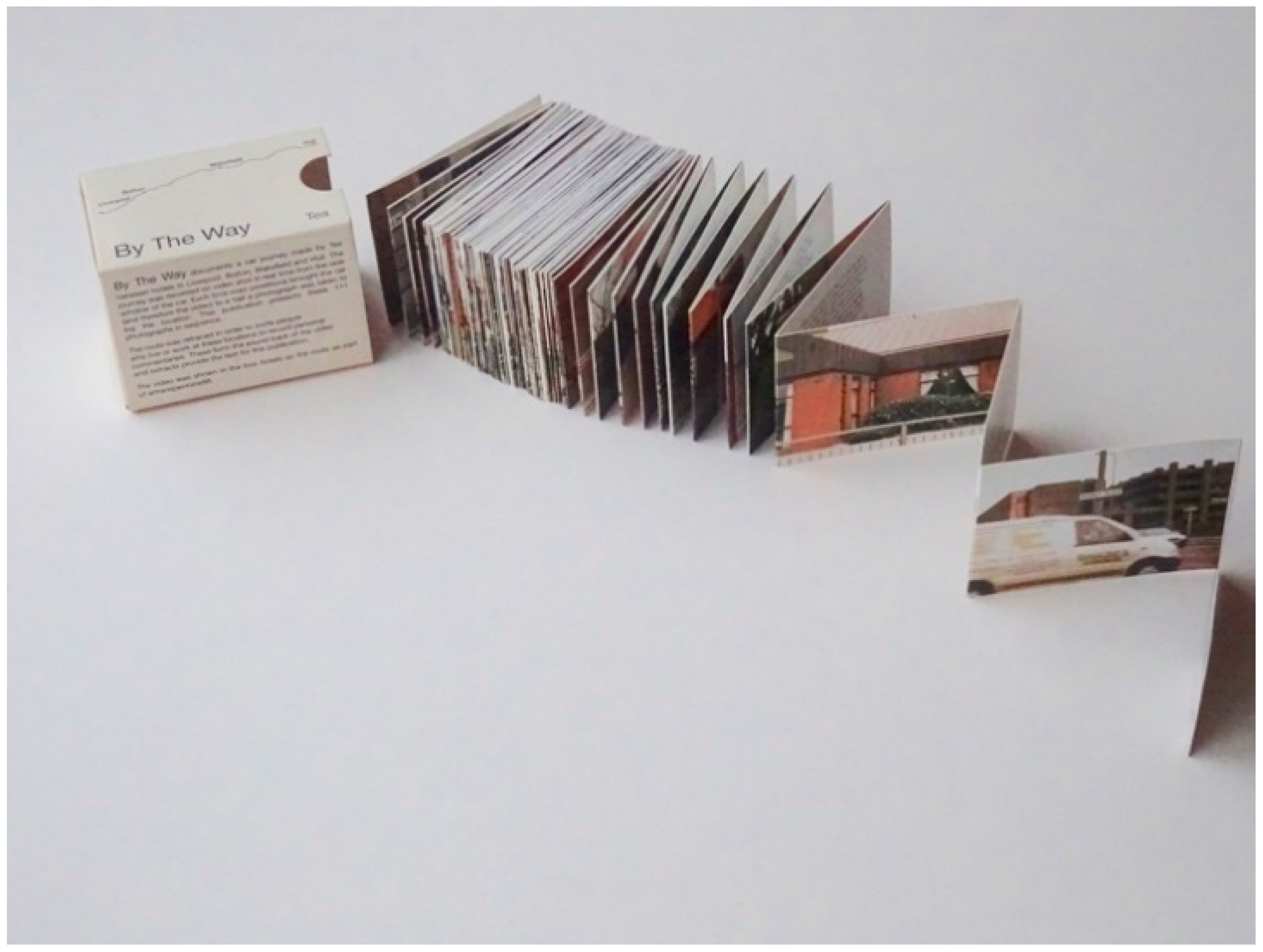

For specific artists, the publication is not about recording an approach, but more about creating an object that holds the essence of the work without necessarily reproducing it. The more successful of these crafted products can stand on their own. When Those Environmental Artists (TEA), a collaboration between Jon Biddulph, Peter Hatton, Val Murray and Lynn Pilling, were commissioned by artranspennine98 to initiate the work

By The Way (1998) to reveal the transpennine region from Hull to Liverpool, they filmed their drive between the two cities out of the side window of a car in real time, producing a five-hour unedited film. Every time the car stopped, a photograph was taken out of the window, and this location was later revisited to record the observations of someone speaking about their place. The completed work was shown to passers-by, on the original route, in the foyers of four Forte Hotels. The film played for the three-month duration of the artranspennine exhibition but to our knowledge has never been shown again. However, TEA then used the 111 images of places along the route and associated edited dialogue to produce a 55 mm high and 9 m long strip of images on one side with the quotation from each interview on the reverse, all concertinaed into a small, carefully designed and printed bespoke carboard container, all at once magically capturing the entire car journey across a region from the North Sea to the Irish Sea, while sitting in the hand, permitting the viewer to form an intimate relationship with the work (

Figure 3).

The deliberately awkwardly framed snaps taken out of a car side window are generally, but not exclusively, of architecture, the type you find adjacent to major trunk roads. With the artist’s book, as opposed to the film, you can study each image for as long as you require, while having the opportunity to juxtaposition any of the other images next to it, even from opposite ends of the journey. Likewise, those texts can be read repeatedly, offering the prospect to digest their relevance to the places they depict. The publication By The Way (TEA, 1999) was funded independently from artranspennine98 and seemed to fulfil a desire by TEA to produce a separate artwork that captured the essence of the work but in a material that is more durable than digital film. It is positioned against the actual work, as the low-tech version, whose batteries will never run out—an antidote to the commissioned film now acting as the research for the small, boxed, concertinaed object. Rather than documenting the project in the style of an exhibition catalogue, the publication constitutes another iteration of the artwork, which provides an alternative account of TEA’s journey that is assessable to a wider non-geographically defined audience.

The ability of the artist to work with the architectural form of a publication to reflect an aspect of the physical nature of the work has become a well-used and fruitful strategy. It enables the viewer to gain an understanding of the relationship between the form of the site or location and the artist’s work. TEA’s

By The Way traversed a whole region, whereas Glassball, artists Cora Glass and David Ball, generated a work for a whole street in the Hanley East area of Stoke-on-Trent during a period of change, both positive and negative. David Gibson of PNC Regeneration describes the project in their self-published concertinaed book,

Living Gallery, an archival record (2010), as follows:

In 2008 Glassball was commissioned to develop and deliver the Living Gallery project. Their job was to deliver high quality art works to be placed over the secured windows and doors of properties purchased for clearance, in order to create a ‘gallery’ of art works that would not only have visual impact on the area but would also be relevant and meaningful to the local community.

Many artists that work within the expanded field of public art have created artworks that have been funded by and are part of regeneration projects, sometimes described disingenuously as “art washing”. They bring their creative abilities and interests, in this case, a willingness to work with a place and a community, to create a work that eventually expands the boundary of the original regeneration brief.

After the event, in this case, not uncommonly following a research and development period life of two years, there becomes a need to capture the project’s numerous facets and acknowledge the many local participants and partners’ involvement in the activity. Thus, the artist’s book sets out to transcend the multiple agendas and audiences, in this case, PNC Regeneration, residents of all ages and service providers, for example, housing associations. However, this book has another purpose, that is to create a contemporary art context for the work, establishing its value as an artwork that sits entirely outside of an art gallery context, unconnected to the traditional art world. Through its distribution, the artist’s book places the work into that wider cannon of practice, especially as it becomes housed in appropriate collections and archives.

Consequently, it is the artist’s book that can transcend the life of all these works presented. The Russian artist/architect El Lissitzy often singled out the artist’s book as his preferred creative medium. In his essay

The New Culture, published in Vitebsk in 1919, he talks about how he values the artist’s book: “In contrast to the old monumental art itself (the book) goes to the people and does not stand like a cathedral in one place waiting for someone to approach. Surely the book is now everything. It expects the contemporary artist to make of it this ‘monument of the future’” (

Perloff 2016, p. 150). Later, in the 1960s, the Dutch artist Jan Dibbets gave up painting to concentrate on interventions in the landscape, which he then recorded using photography. In 1969, he created the work

Robin Redbreast’s Territory/Sculpture (1969). The small book contained all the ingredients that you now find in artists’ books that document site-specific projects. There is a map of Amsterdam showing the location of Vondel Park, including hand-drawn sketches of the sculpture’s location. Drawings, photographs and hand-written notes in his native language are set out on the left-hand pages and then typewritten in English, French and German on the opposite page. The project sets out to manipulate the territory of a robin in the park by installing poles with perches, which were slowly moved each day. The work was the drawing in space that the robin created by flying between the poles. This is something that can only be fashioned in the viewer’s imagination while reading the small hand-sized artist’s book, far outliving the original sited work. In a recorded interview at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Jan Dibbets states, “The book at the end is the real sculpture”.

2 3. The Artist’s Book as Public Art

One of the criticisms levied at public art is that it tends to impose meanings upon and ossify experiences of a place. Indeed, the monumental sculptures and artist-designed street furniture, which sprang up like mushrooms across UK post-industrial cities at the start of the millennium, embodied government-led efforts to replace narratives of economic and social decline with the promise of an “urban renaissance”. The political implications of such instrumentalisation, which extended to temporary and “socially engaged” forms of art practice, have been subject to much critique in recent years, particularly in relation to gentrification processes and the phenomenon of “art washing” (see

Pritchard 2017). Alongside grassroots social art projects and activist interventions, this includes the production and publication of artists’ books, which artists have embraced as autonomous critical spaces that facilitate layered and subjective engagements with familiar and unknown places. In this section, therefore, we examine some of the properties that make artists’ books particularly conducive to creative investigations of place, through a focus upon the work of three artists from the North of England: Joanne Lee, Emily Speed and Magda Stawarska-Beavan.

For artists disillusioned with the bureaucratic tendencies and standardised forms of practice within the field of public art, the artist’s book offers an alternative form of publicness, which, due to its low production costs and ease of distribution, provides a greater scope for experimentation and critical engagement with places. Sheffield-based artist Joanne Lee, for example, describes how, after graduating from university, she became frustrated with what she felt was her increasingly formulaic response to the site-specific projects she was invited to develop in places across the UK and Europe. Echoing Miwon Kwon’s critique of nomadic art practices in her book

One Place after Another—in which she emphasises the “undifferentiated serialization” of places that can occur when artists fail to attend to the contradictions within and relationships between places (

Kwon 2002, p. 166)—Lee became “suspicious” that her ability to create work about a site that she had inhabited only briefly did not constitute “a proper investigation of place”.

3 In response, she began focussing on her immediate environment and “obsessing over the things which were immediately to hand”: condensation on a window, stained surfaces, the texture of tarmac, the shapes of bollards. Such ephemera eventually became the subject of a long-term self-publishing project, in which Lee attends to aspects of the everyday in forensic-like detail through photography and expansive critical essays.

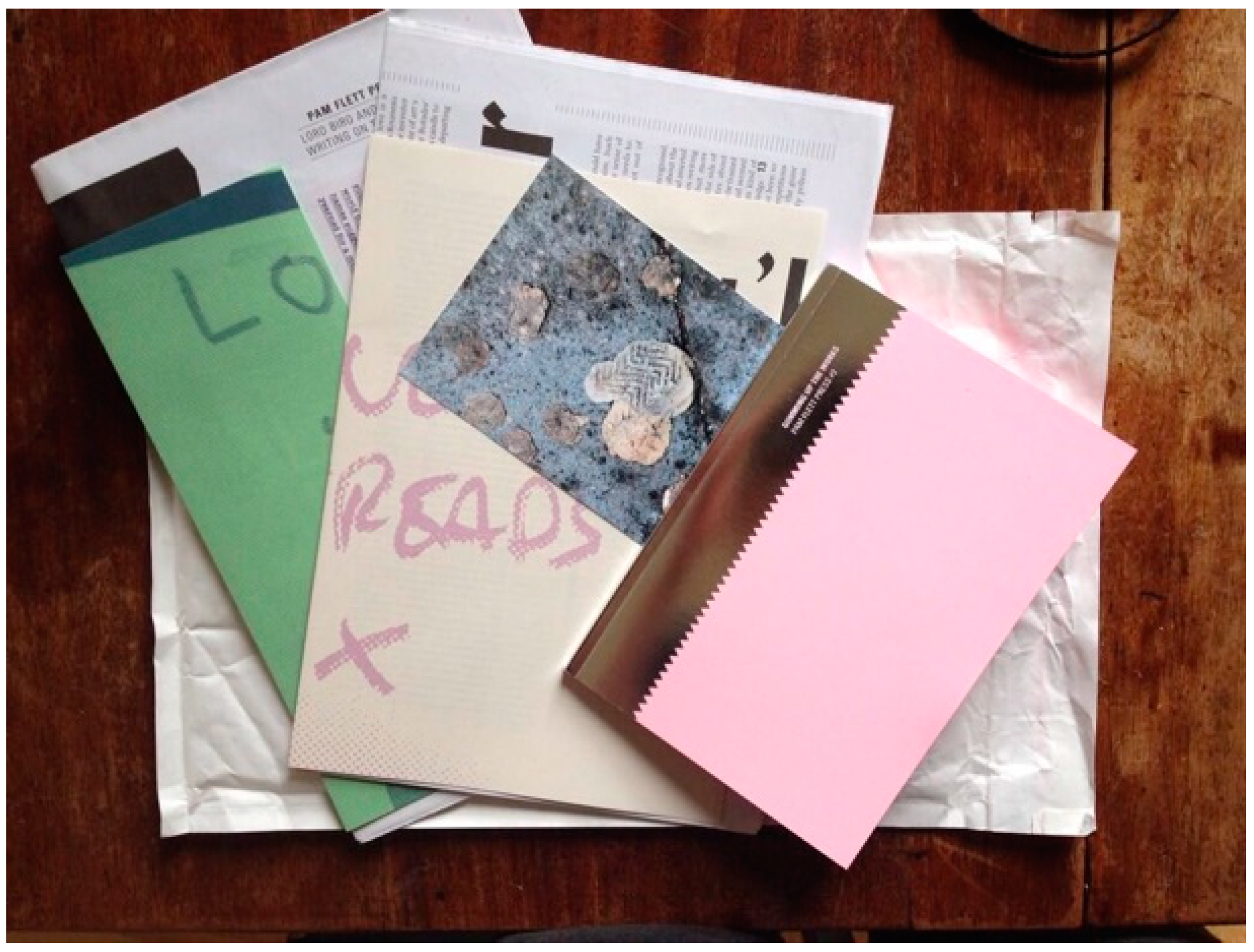

The title of Lee’s series, the

Pam Flett Press (2011–) (

Figure 4), is a pun that describes her chosen format and evokes an image of a stout and stoic woman handing out religious or political tracts. This mixture of fanaticism and pragmatism characterises Lee’s approach to the press, which, as a self-funded venture, allows her to indulge her curiosity about the nature of everyday life without the pressure to meet deadlines or the tick-box agendas of commissioners and funding bodies. The first issue,

Call Yourself a Bloody Professional, sets out Lee’s motivations for creating the press through an exploration of amateurism. Emphasising the etymology of the term, Lee examines what it means to pursue a project due to love rather than professional necessity and constructs a portrait of the amateur as a meticulous, insightful and inventive individual, who is motivated by the pursuit of knowledge rather than professional status. As a lover, the amateur attends to her subject with a level of intimacy and care that the professional sphere, with its rule-bound procedures and disciplinary boundaries, actively discourages.

In this way, rather than lacking in quality, the activities of the amateur are not only rigorous but, in their disregard for upholding the status quo, are also “powerfully critical” (

Lee 2011). As a conscious alternative to the peer-reviewed and increasingly monetised model of publishing by which academic success is measured, the

Pam Flett Press embodies

Simon Cutts’ (

2007, p. 66) definition of self-publishing as “a defined critical stance”. For Cutts, such projects, which could also include Craig Atkinson’s

Café Royal Books4 series, the publications of practice-based research project

Manual Labours,

5 Twigs and Apples publishing

6 and

The Shrieking Violet,

7 amongst many others, provide an antidote to what he sees as the mainstream co-option of radical art practices, through which “art activity is relegated to the blandness of footfall” in the service of financial gain (ibid., p. 54). Within the context of public art, the act of publishing can itself be thought of as “a public work” (ibid., p. 87), through which, as “a prime object”, the artist’s book occupies “if not sculptural, certainly critical space” (ibid., p. 70).

In relation to projects that deal with place, criticality can be understood as an approach that, in the words of geographer Doreen Massey, acknowledges its “unfixed, contested and multiple” nature (

Massey 1994, p. 5). For example, as an investigation into the post-industrial landscapes that form the backdrop to Lee’s life, the press accommodates a level of complexity that mainstream public art tends to avoid in favour of cohesive narratives. Forging connections between such seemingly disparate subject matters as chewing gum, contemporary art and the digestive functions of earthworms, the series explores ontological questions about our interactions with the world through a focus on what might be classed as the more banal aspects of life. This approach, which is epitomised by the self-published works of fellow Yorkshire artist and postman Kevin Boniface,

8 chimes with Massey’s description of places as constellations of “social relations” (ibid., p. 154), which, whilst increasingly interconnected and global, are often encountered through such mundanities as “waiting in a bus-shelter with your shopping for a bus that never comes” (ibid., p. 163).

For Lee, the artist’s book provides a “handy container” for the “disparate ideas and images” that characterise her practice (

Lee 2011). Chosen for its modest immediacy and political associations, the pamphlet also serves as a visual shorthand for the radical aims of the project. Yet, in contrast to the throw-away qualities associated with the form, the

Pam Flett Press is a series of carefully crafted objects. Produced in collaboration with the Sheffield-based collective dust, the pamphlets are inventively designed and folded, setting up dialogues between image and text and encouraging the reader to interact physically, as well as intellectually, with the work. As forms of public art, the architecture of artists’ books is of particular significance. Architectural historian and writer Jane

Rendell (

2006, p. 65) points out that although “books are public sites accessible to diverse audiences”, they are “not usually regarded as ‘physical’ locations”. However, as “sites”, they are defined by “specific formal limits and material qualities”, such as the type of paper or size of font used, and “are produced through particular spatial practices or habits of use” (ibid.), such as reading from left to right. In this sense, much like geographical sites, books allow artists to question assumed understandings and to generate new forms of knowledge by disrupting familiar protocols and challenging assumptions of what might happen in a place.

Emily Speed’s publications provide a particularly good example of how artists can produce critical readings of place by attending to the architecture of artists’ books. As an artist who undertakes projects within both gallery and public art contexts, Speed often creates publications to accompany and contextualise her work. However, as physical and cultural spaces, artists’ books also provide a context for her explorations into the interplay between buildings, bodies and psychological space. By exposing and subverting “the spatial ways in which we read images and words” (ibid.), Speed’s books emphasise the embodied and performative nature of reading and make connections between the structural qualities of books and those of the built environment. Her contribution to

Practising Place (

Speight 2019), for example—an anthology of collaborative essays on place by artists and academics—explores the ways in which urban dwellers disrupt official attempts to impose order on public space. Presented as a series of unruly footnotes to an essay about city planning by geographer Duncan Light, Speed’s drawings, diagrams and anecdotes break free of the formal styling commonly applied to secondary information. Instead, they cut through the text like desire lines, creeping over it as vines and creating barricades across the page, reflecting the subversive creativity of her subject matter and offering a counternarrative to Light’s account of placemaking as a form of social control.

Speed’s publications tell stories about the built environment and the power relations that shape it. Generally handmade and produced in editions of between 20 and 100 copies, they invite the reader to consider perceptions of place that exist between the gaps of mainstream experience.

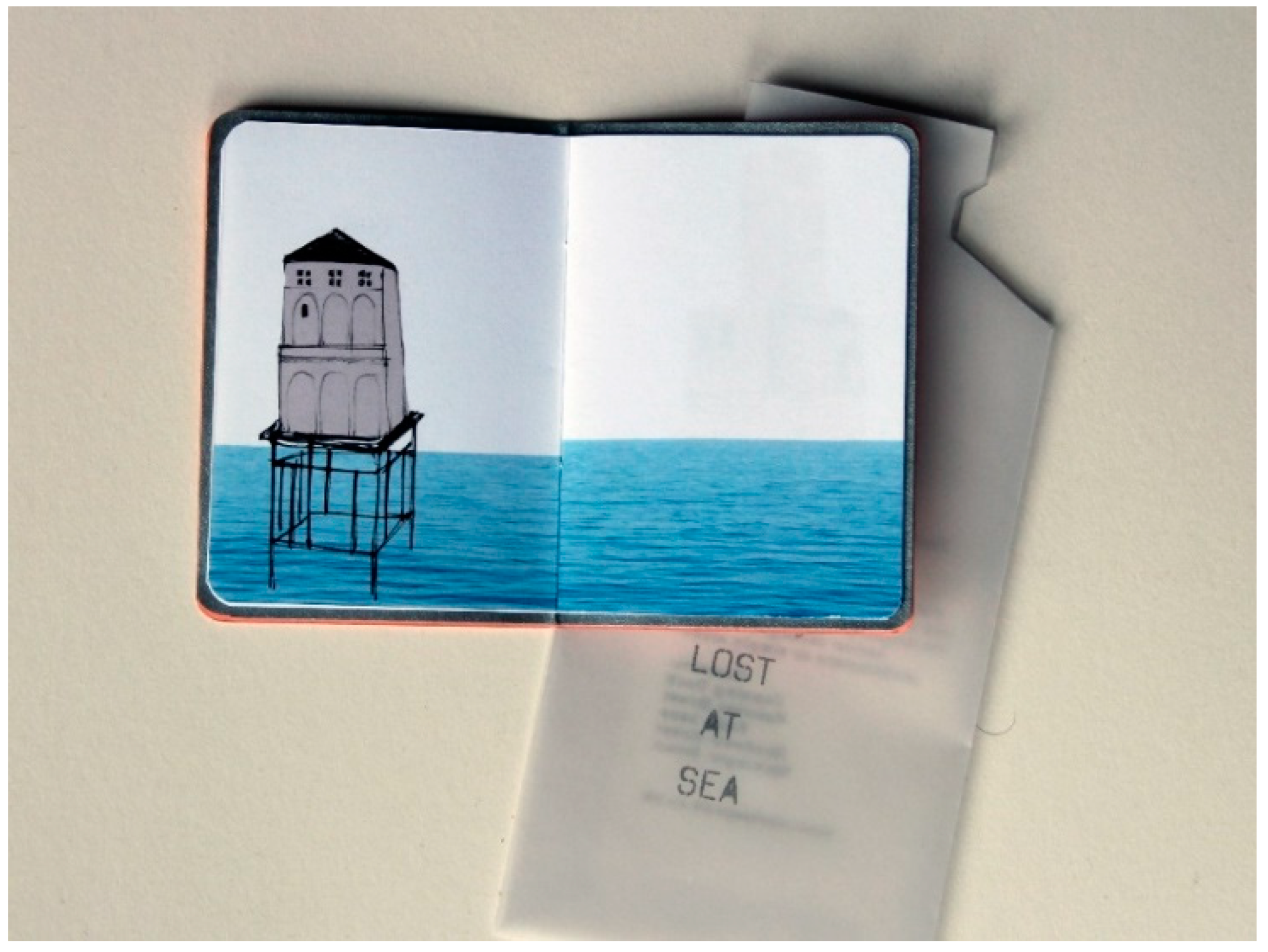

Lost at Sea (2009) (

Figure 5), for example, is a diminutive publication encased within a transparent bottle-shaped envelope. Featuring drawings of historic buildings that have been side-lined by Liverpool’s redevelopment, it raises questions about which lives and histories are preserved or enhanced by regeneration and which are pushed to the margins. Similarly,

Places for Hiding (2009) deals with the architecture of the powerless. “Hidden” within an envelope that resembles the hoardings on development sites, it contains simple line drawings of make-shift structures, reminiscent of childhood dens. Yet, the austerity of its production points to a bleaker architecture: that of refugees, the homeless and other communities at the fringes of urban society. Whilst subtler in form and content, these books share similarities with Laura Oldfield Ford’s zine series,

Savage Messiah (2005–2009), which reveals “the hidden narratives and oppositional currents’ beneath the ‘smooth space’ produced by regeneration schemes” (

Iles and Berry Slater 2010, p. 46). By focussing upon experiences of vulnerability and precarity within the contemporary city, such projects invite alternative readings of place and present a model of public art as a form of critical practice rather than a “social and environmental enhancer” (ibid., p. 22).

One of the main differences between artists’ books and mainstream forms of public art, such as monumental sculpture, is that whilst the latter broadcasts its message to an undifferentiated public, artists’ books offer a profoundly personal experience.

Cutts (

2007, p. 57) describes “the presence of the book” as “invitational”, because it “reveals its sensation as it is unfolded at a pace controlled by the reader”. In this sense, the reader is not merely a passive viewer, but an embodied participant and a co-producer of meaning within the work. Artists Katja Hilevaara and Emily Orley describe how the architecture of “the bound book, made up of folded sheets of paper”, facilitates a “multi-dimensionality” of practice (

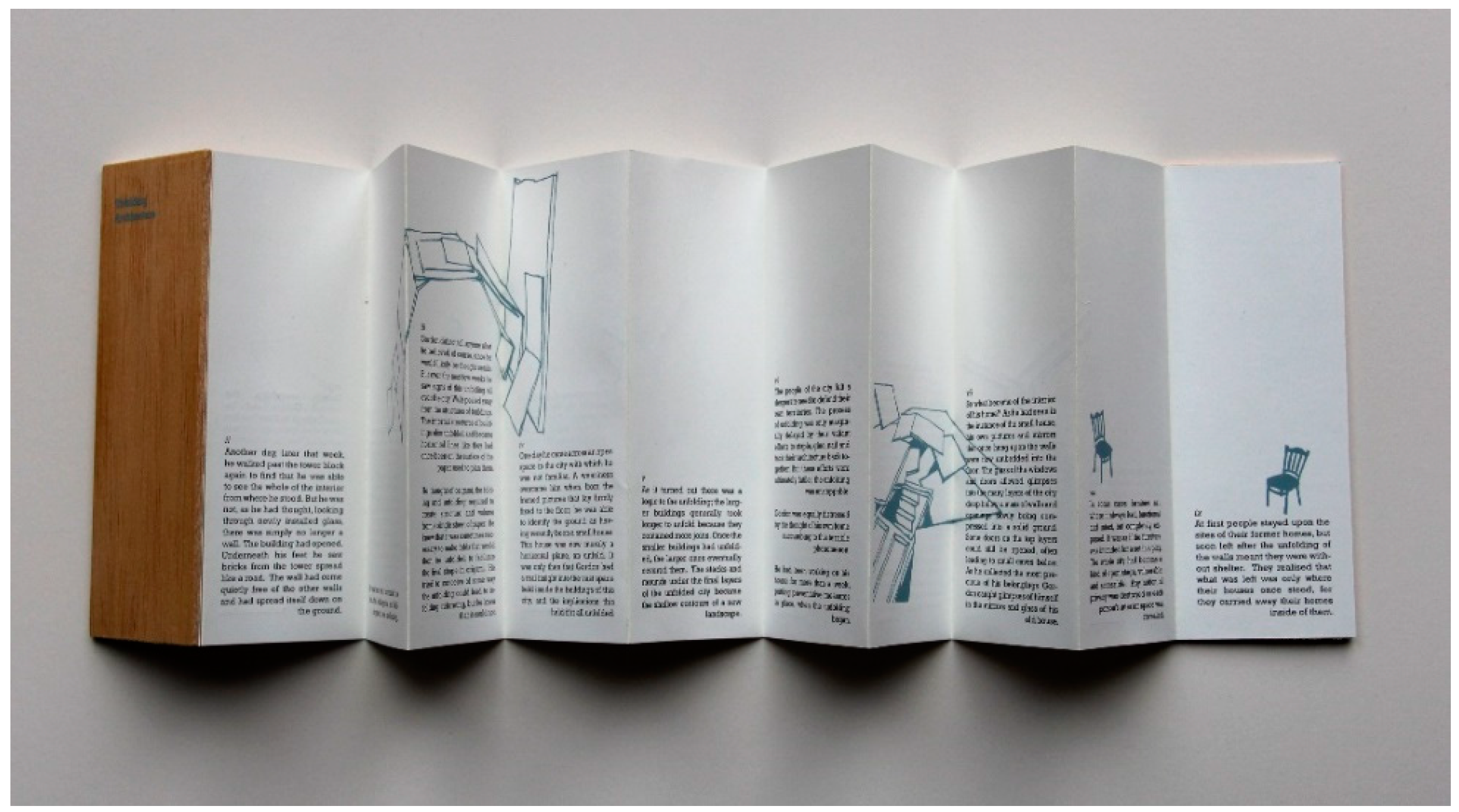

Hilevaara and Orley 2018, p. 3). Specifically, “the physical action of folding” creates “an endless feedback cycle”, which “both enables linear, codified reading, yet simultaneously disrupts its continuity”, as the reader opts “to fold backwards, forwards, interweave” or “extract” the publication’s content (ibid.). The diversity of experience enabled by the fold is made explicit in Speed’s

Unfolding Architecture (2007) (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7), an accordion-folded book that recounts the tale of Gordon, a city dweller who witnesses the collapse of public buildings and, ultimately, his own home as the urban fabric begins to unfold around him. Housed in a balsa wood box that, somewhat alarmingly, unfolds upon opening, the fragility of the folded sheet provokes something of the protagonist’s anxiety about the undoing of his city. Yet, whilst employed by Speed as a metaphor for “the empty space” left behind by the “disappearance of a loved one through dementia”, the act of unfolding also produces “an open plain full of possibility” (

Speed 2019). As Gordon asserts, unfolding is not the same as falling apart, and the artist’s book suggests that hope and potential may be achieved through the dismantling of existing structures.

The symbiotic relationship produced between the artist’s book and the reader is particularly conducive to examining aspects of place. Human geographers have long asserted the relational nature of place as an ongoing “event” (

Cresswell 2004, p. 40), which is produced through the “meeting and weaving together” (

Massey 1994, p. 154) of different experiences and identities at a particular location. In other words, the character or essence of a place is never fixed or predetermined but is contingent upon the activities of its inhabitants and exists as an ongoing process of becoming. Artists’ books that critically engage with geographical locations could be seen to contribute to such place-becoming by generating new connections with and experiences of them. The work of artist Magda Stawarska-Beavan is a particular case in point. As a founder member of Art Lab, a printmaking research project at the University of Central Lancashire in Preston, Stawarska-Beavan has a history of working with artists and record labels to produce books that are both visual artefacts and recorded sound artworks. Within her own practice this approach has been employed to produce hybrid artworks, such as

Resonating Silence (2019)—a handprinted artwork, vinyl record and video installation that explores the acoustic environment of Manchester Central Library—and

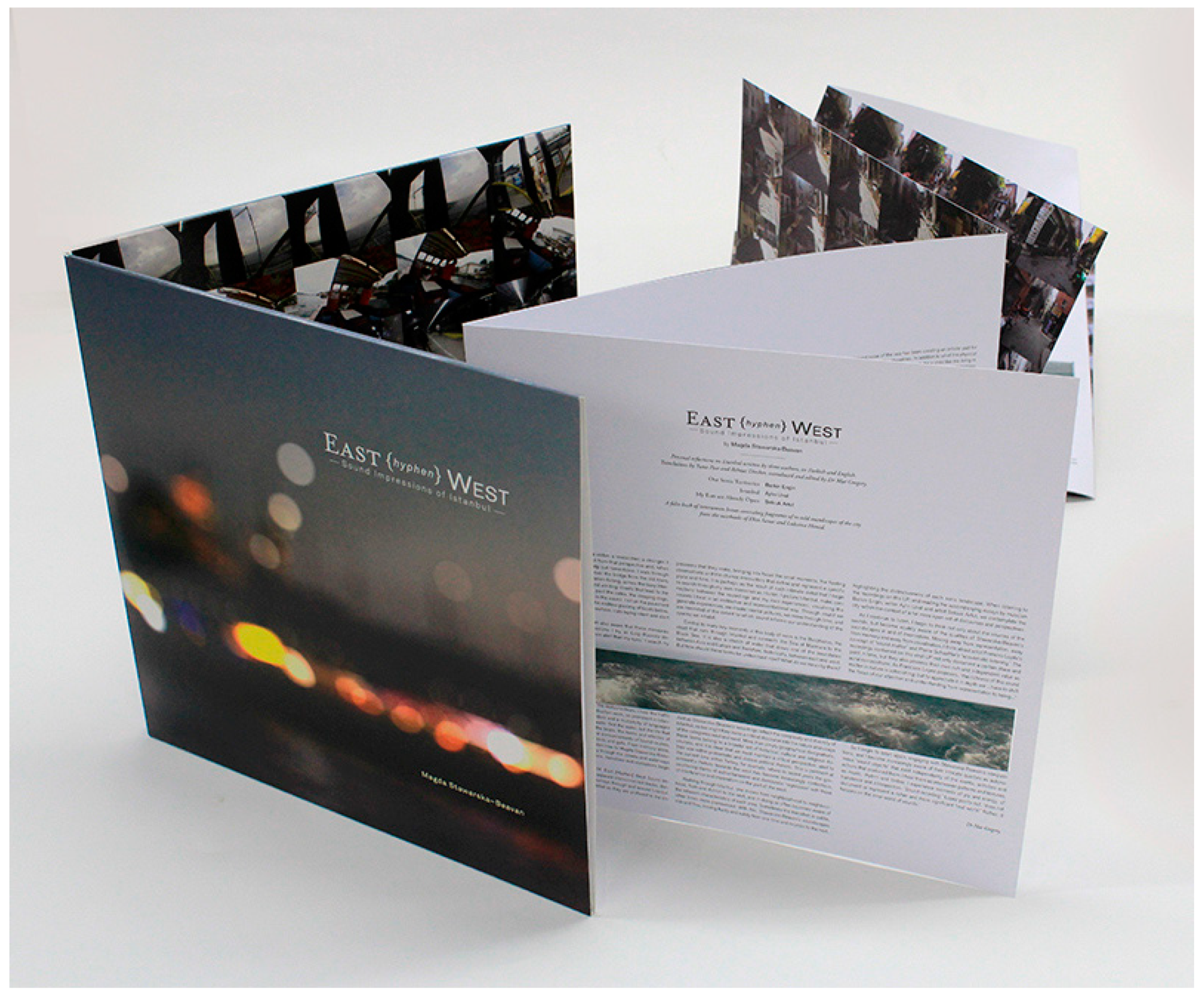

East {hyphen} West, Sound Impressions of Istanbul (2015) (

Figure 8), a limited-edition artist’s book and record, produced in response to a month-long visit to the city. The latter work includes audio–visual content captured by devices attached to the artist’s body as she walked through Istanbul, as well as written and vocalised responses to the recorded soundscape by artist Lubaina Himid and musician Ekin Sanaç. The effect is an embodied, intimate and immersive encounter with, what for many readers and listeners, will be an unfamiliar place.

The inclusion of sound recordings within the books of Starwarska-Beavan, as well as those of artists such as Helen Cammock—whose artist book and record

Moveable Bridge (2017) explores the effect of national politics and global economics upon communities in Hull—adds an additional dimension to the experience of place engendered by the work. Sound artists Agnus Carlyle and Cathy Lane describe how “the practice of listening can operate to reveal a parallel reality” to that of the purely visual, which “lies below, beyond, behind or inside that which is immediately accessible” (

Carlyle and Lane 2013, p. 9). Stawarska-Beavan’s watery compositions, produced from recordings taken on, around and under the Bosporus Strait, create a sense of movement, both physically and culturally, between the east and west of Istanbul. Yet, whilst certain distinctions emerge from the cacophony of sounds, the complexity of the soundscapes, in which environmental, mechanical and animal sounds merge with human voices, belies the reductive binary of political rhetoric, in which east and west are fundamentally opposed. In capturing the “small moments” and “chance encounters which define a time and place” (

Gregory 2015), the work allows for more nuanced readings, which generate certain insights. In her recorded response to the composition, for example, Lubaina Himid observes the dominance of male voices throughout Stawarska-Beavan’s soundscapes of Istanbul. In so doing, she reveals the gendered nature of the city’s “power geometry”—a term used by

Massey (

1994) to describe the ways in which access and experience are shaped by disparities of power—and highlights the significance of the artist’s subjectivity as a woman walking alone.

The process of listening to Starwarska-Beavan’s soundscapes is an active one, in which the audience contributes their own experiences, memories and imagination to the construction of a multi-layered sense of place. The work, therefore, cannot be experienced passively but necessitates the active involvement of its audience.

Lane (

2013, p. 153) points out that the act of listening “is not easy”, but “requires full concentration and the engagement of all our faculties”. It demands time, attention and physical interaction, through the employment of our senses.

Tim Ingold (

1993, p. 220) writes that “seeing, hearing and touching are not passive reactions of the body to external stimuli but processes of actively and intentionally attending to the world”. Sensory works, such as Stawarska-Beavan’s, are, therefore, able to connect us to places in ways that implicate us within the production of various meanings. The same is also true of artists’ books, such as those of Lee and Speed, which invite us to engage through haptic interaction. Sociologist

Les Back (

2007, p. 7) asserts that “social investigations” that utilise non-ocularcentric forms of engagement “are likely to notice more and ask different questions of the world”. As objects that employ “a democracy of the senses” (ibid.), artists’ books in all their forms have the potential to move beyond dominant narratives of place, towards more complex and critical understandings.

As we have sought to demonstrate in this essay, the relationship between public art and the artist’s book is a long and productive one. Initially employed as a temporal strategy to document and provide a legacy for ephemeral and site-specific artworks, particularly through the use of photography, the role of artists’ books has subsequently developed to accommodate the challenges and opportunities presented by a more expansive approach to public art. In many cases, the decision to create a publication is informed by pragmatic concerns relating to the artist’s professional development and future career prospects. For example, as a tangible record of an otherwise temporary project, the artist’s book serves as a proxy artwork for a secondary audience and a convenient calling card to present to potential patrons. In addition, by providing an art historical or theoretical underpinning for the work, publications can help to reframe projects commissioned through commercial or municipal channels within a contemporary art context. They also offer a space in which the artist is able to ascribe visibility and value to the creative, practical and political processes through which public artworks are realised but which are often eclipsed by the final artefact.

The dematerialisation of public art that has occurred over the last 50 years, in which “context is half the work” (

Artist Placement Group 2019) and process supplants product, has led to further roles for artists’ books. These include as ancillary and supporting artworks, as well as providing a medium for the final outcomes of a project. As low cost and accessible “forms of availability” (

Cutts 2007), publications enable artists to eschew the limitations imposed by the professionalisation of public art, in favour of more autonomous and radical models of creative practice and dissemination. In particular, artists’ books provide a productive format for creative explorations of place. As sensory and interactive objects, they allow for subjectivity, multi-layered readings and the type of embodied experience not permitted by popular forms of digital communication. In this way, they can be understood as a critical and particularly contemporary form of public art. Curator Claire Doherty explains how growing disaffection with dominant commissioning approaches has led to the emergence of long-term artist-led projects that call for “a shift in our thinking about the ‘time’, rather than simply the ‘space’ of public art” (

Doherty 2015, p. 14). Through their temporal and democratic properties, artists’ books provide a context in which to evaluate the practice of art and place and to generate further responses. Above all, by accommodating the “fragile possibilities” and “bits of ephemera” that “might only reverberate in the mind” (

Cutts 2007, p. 87), they “enrich what can be thought of everyday things” (

Lee and Wilson 2019, p. 14) and encourage new ways of understanding, responding to and being in place.