Abstract

Zemun is an old Central European town on the right bank of the Danube River, today one of the boroughs of Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. There has been a small Jewish community in Zemun dating back to the mid-18th century. Some of the Jews who lived in Zemun in the 19th century contributed to the emergence of Zionism. This paper presents new archival information about Zemun’s Jewish quarter including an analysis of the Zemun synagogue as well as various hermeneutic explanations of its urban and architectural development. Previous analyses of this area of Zemun have focused on external and morphological characteristics of its religious architecture but failed to explain its conceptual, historical, socio-political and religious context. This paper will cover these new elements as well as establish a basis for understanding this part of the old urban core of Zemun in relation to the significant personalities who lived there and the important ideas they developed.

1. Introduction

Zemun (Srb. Zemun, Hun. Zimony, Ger. Semlin) is an old Central European town on the right bank of the Danube River, today one of the boroughs of Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. Due to its strategic location adjacent to the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and as it is at the crossroads between Central Europe and the Balkans, it has had a turbulent history. Many armies conquered it including the Avars, Byzantines, Bulgarians and the Crusaders. At the beginning of the 9th century, it was even a part of Charlemagne Carolingian’s Empire. In the Roman times, Zemun was known as Taurunum, but by the mid-9th century, Slavs moved in and bestowed it with the name Zemun which it has maintained until the present time. Towards the end of the Middle Ages, Zemun was controlled by the Hungarians and when Belgrade came under Turkish control in 1521, so did Zemun. It remained under the Turks for almost 200 years until 1717 and the signing of the Treaty of Belgrade in 1739, which defined the Sava and Danube as the border between the Ottoman and Habsburg Empires. In 1746, Zemun became part of the Military Frontier (Militärgrenze) of the Habsburg Empire and three years later, the Military Commune (Militär Communität). Zemun remained part of the Habsburg (later Austro-Hungarian) Empire until its dissolution in 1918.

Economically, whenever the Sava and Danube formed its border, Zemun progressed as a border town and trading center. At the end of the 18th century, Zemun was equidistance from Vienna and Istanbul—the capitals of the two rival empires, in the vicinity of the rich and fertile Pannonian plains, as well as in the middle of the vast network of river and land traffic that connected Central Europe with the Balkans and further east.1 Since it was a border town, a quarantine station was established in it in 1730. In addition to sanitary benefits i.e., in preventing the spread of infectious diseases like the plague from Turkey, the quarantine was also an important trading center and an initiator of economic development for Zemun.2 Thanks to trading, Zemun became a multiethnic place where, besides the Serbian majority, Aromanians, Greeks, Czechs and Germans lived and enjoyed equality.

Jews moved to Zemun after the Austrian retreat from Belgrade and Serbia in 1739, when after more than 50 years of Austro-Turkish wars, the border was established along the Sava and Danube rivers. Around 1742, there were five to eight Jewish families living in Zemun (Gavrilović 1989, p. 78). During the next decade, the number of Jewish families increased. Jews were later granted permission to settle in Zemun through Maria Theresa’s special decree of October 23rd 1753 (Gavrilović 1989, p. 79). However, that privilege was granted to only 19 families, with the strict prohibition of expanding the number of families.3 That prohibition proved to be the main obstacle to the further development of both the Zemun Jewish community and the Zemun Jewish Quarter all the way until 1867.

The most important sources of Zemun’s early urbanism are maps preserved in the collection of the local museum in Zemun and the ones housed at the Vienna War Archives (Dabižić 2014, p. 127). These cartographic sources prove that Zemun’s urban development was very rapid. From an abandoned village sold by Counts of Schönborn in the 4th decade of the 18th century, to the completely formed and defined town that was, according to some 19th century accounts, “the most beautiful and richest town within the Military Frontier,” less than 50 years has passed (Dabižić 1967, p. 8).

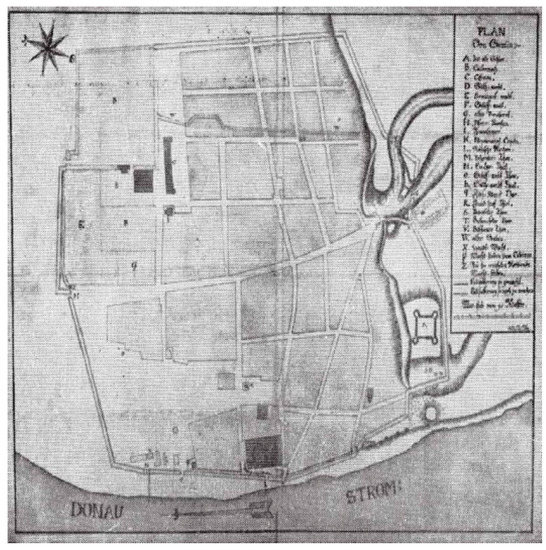

Basic outlines of urban Zemun that will define its future development, according to Klotz’s city plan (Figure 1) appeared 15 years after the Belgrade Treaty (1739). At that time, Zemun was formed as a relatively regular square at the foot of a sand hill, present day Gardoš, parallel to the Danube flow and fenced off with palisades.

Figure 1.

Johan Michael Klotz’s plan of the City of Zemun, 1754.

2. Jewish Quarter of Zemun

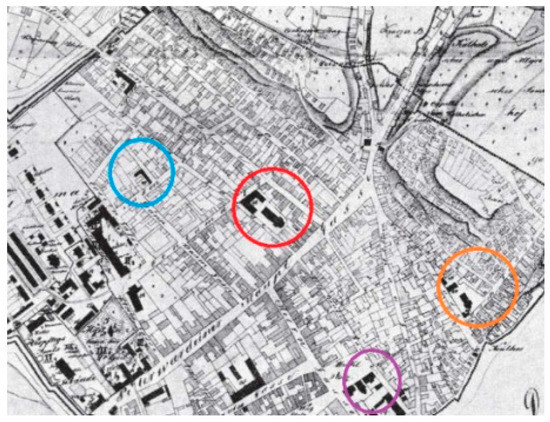

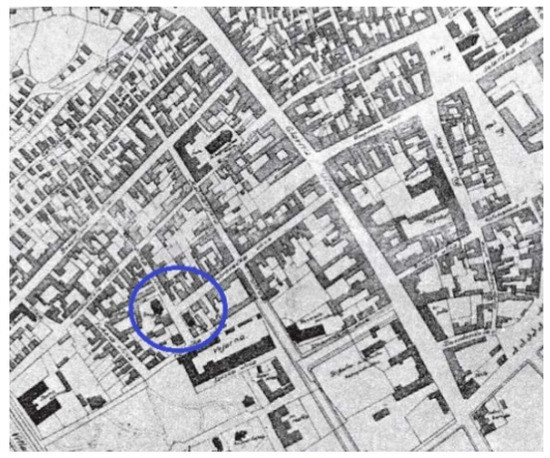

The part of the old Zemun core we are interested in was situated along the south-west border of the town and was already urbanistically defined around 1740. From that time on, it only spread slightly westward. Generally, the quarter was outlined by Main Street to the east, Bežanijska Street to the north and the Kontumaz area to the south.

While there was never a formal ghetto in Zemun, in the early stages of the town’s development, Jews were ordered to “be secluded from Christians”, forbidden “to live on Main Street” (Ćelap 1958–59, p. 62), required to stay “in their mahallah”(quarter in Turkish)4 as well as to live far away from churches.5 Namely, in the first months of 1742, when there were only a few Jewish families living in Zemun, the Habsburg Slavonian State authority recommended that an area be set aside for them “a bit further from the Sava (sic!), where they can construct their houses” (Gavrilović 1989, p. 78).6

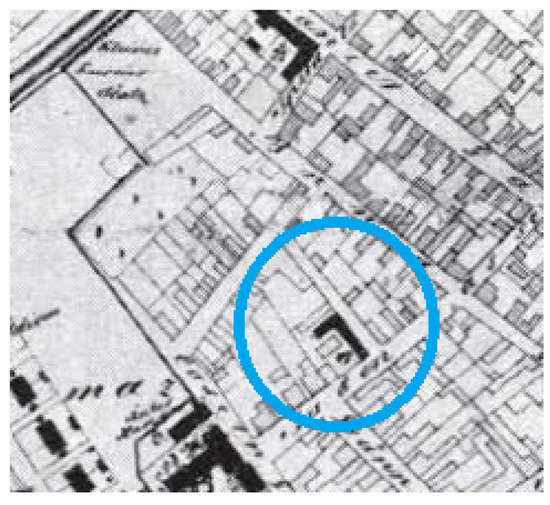

As early as 1830, Carl Berthold’s city plan shows that the district’s primary thoroughfare was called Jewish Street (Judengasse)7 (Figure 2). However, according to Škalamera, this is not the earliest mention of the Jewish Street.8 Lazar Ćelap (1958–59, p. 60) referred to Dubrovačka Street as the “Jewish sokak.”9 If we accept both of these accounts as reliable, we can assume that towards the end of the first period of their settlement in Zemun, Jews lived on two streets—Jewish Street, later known as Primorska and today as Rabbi Yehudah Alkalay Street, and on Long Street, today known as Dubrovačka Street.10 Since the trench built to protect the Kontumaz and the town palisade fence were close to these streets, and since we know that Jews owned 15 houses that were situated close by to one another, probably due to the regulation of eruv (ritual halakhic enclosure), one can say that this was the initial Jewish quarter.11

Figure 2.

Carl Berthold’s plan of the City of Zemun with Jewish street, 1830.

Although secluded from the rest of the town, the Jewish quarter had no gates and did not have the appearance or other characteristics of a ghetto. It closely resembled the “Čivutska mahallah” (Jewish quarter in Turkish) across the river in Ottoman controlled Belgrade. Both the Jewish quarter of Zemun and the mahallah of Dorćol-Yali in Belgrade were situated on land that was prone to flooding, close to the main business centers and both had a Dubrovačka Street nearby.

The location of Zemun’s Jewish quarter presented certain challenges. There were health issues because the land was low lying and moss covered it, causing residual water to seep into the houses, exposing the inhabitants to the risk of malaria. It was also close to the quarantine, exposing them to the constant threat of the plague. The location also presented certain benefits: Jewish traders—mainly wholesalers—were able to participate in business transactions related to the Kontumaz which, during its 112-year long existence, was the main engine of Zemun’s economy and the center of trade on the border of the two empires.12 Living conditions in the quarter did not improve much with the closure of the Kontumaz in 1842 since the abandoned warehouses were repurposed for drying raw hide which was accompanied by an unbearable stench (Dabižić 2013, p. 148).13

According to the research of Camillo Sitte (1967, p. 2), symbolic-hierarchical structuring of the town marked all of the historic periods until the 20th century; later on, modernistic and functionalistic concepts were implemented through zoning principles. According to that principle, the town became urbanistically structured around central objects that had symbolic meaning. In Zemun, this certainly referred to the Great Square with its Catholic Church of the Ascension of the Blessed Virgin which was the town’s focal point since during Zemun’s formation as a modern settlement at the beginning of the 18th century, Catholicism was the official state religion of the Habsburg Empire.14 In such a hierarchical order, church edifices have the greatest symbolic weight, as well as spatial-material significance. In general, each of Zemun’s ethnic quarters was formed around main religious buildings, although the hierarchy was also established according to the wealth and influence of certain citizens.15

3. Zemun Synagogue, 18th Century

The central part of the Zemun Jewish quarter is occupied by the synagogue (Figure 3). It is the oldest synagogue still standing in Serbia and until today, has not been examined in depth.16

Figure 3.

Zemun synagogue today.

It is common practice to call it the Ashkenazi synagogue, although it was Ashkenazi only between 1871 and 1947, i.e., while a Sephardi synagogue also existed.17 According to Željko Škalamera (1966, p. 79), it was built on the site of an older building from the 18th century.18 Authors that wrote after Škalamera about Jewish religious buildings in Zemun mostly mention 1755 as the year when the “first” synagogue was “built“ (Aćimović 2010, p. 48; Borovnjak 2013, p. 84; Borovnjak 2017, p. 129), without quoting their sources for this statement.19

More frequent references to the synagogue, or the Temple, can be found in the historical records of the Magistrate archives of the second half of the 18th century. Thus, for example, “Johanes Georg Schalk paid 4 forints on 17. 2. 1774 as a fine for twice disturbing Jews in their synagogue.”20 The well-known Zemun chronicler, Dr. Petar Marković (Маркoвић 2004, p. 133), writes in his History of Zemun that the “Jewish Temple in Zemun” is mentioned as early as 1776. Also, the Jewish traders Jakob Rafael Salamon and Enoh Faischl reported that “during the night of 14. 5. 1791 somebody broke into the Temple and stole ritual and precious items, and are asking that an investigation be undertaken.”21 Since the Zemun Magistrate only passed a protocol for the building construction in 1871, it is impossible to confirm the veracity of the assertion that the first synagogue was erected in 1755 as stated previously.

On Wеrthenpreis-Wolgenmuht’s city plan, compiled in 1780 and considered by many researchers as an “absolutely valuable topographic source” (Dabižić 2013, p. 128)—which was created at the time when the synagogue-Temple had already been mentioned in historical documents and travel records—on Jewish, Dubrovačka or Preka streets, no larger or free standing building is visible (Figure 4). At the same time, all the prominent cult edifices of Zemun, two Serbian Orthodox and one Catholic Church, as well as the Franciscan monastery, are visible on the plan. It seems that we can conclude with certainty that a synagogue as a free standing building did not exist in that period.22

Figure 4.

Wеrthenpreis-Wolgenmuht’s plan of the City of Zemun with the Jewish quarter, 1780.

The fact that Toleranzpatent was issued in 1781 confirms this opinion.23 According to that act, religions tolerated in the Austrian Empire were allowed to have meetings of “not more than hundred people in a private home, whose appearance does not differ much from a regular house” (Blitz 1989, p. 585).24 The same act limited the possibility of constructing a non-Catholic religious building, “only to those places where more than a hundred families live and that is more than a day’s walk to another” (Blitz 1989, p. 585). According to the census of 1777, Zemun had 3918 inhabitants, out of which 47 were Jews (Маркoвић 2004, p. 92, f. 17). Since we know that Jews were forbidden to settle within the Military Frontier zone and that the total number of Jewish families who were allowed to permanently settle in Zemun until 1862 never surpassed 33, it is not credible that a synagogue could have been built as a separate, free standing building.25 Moreover, Christian intolerance towards the Jews in Zemun was very pronounced throughout that period.26

Zemun Synagogue, 19th Century

When the First Serbian Uprising broke out in 1804, a large number of Jews, mostly of Sephardic origin, left Belgrade and came to Zemun. Thus, the number of families rose to 27. The central government in Vienna was concerned by these developments and therefore, in early 1816, Emperor Francis I ordered that “thirty families that originate from those nineteen that were granted the privilege to settle in Zemun in 1753, will be allowed to stay and to possess thirty houses.” Besides private houses, “one community building” was mentioned too (Ćelap 1958–59, p. 67).

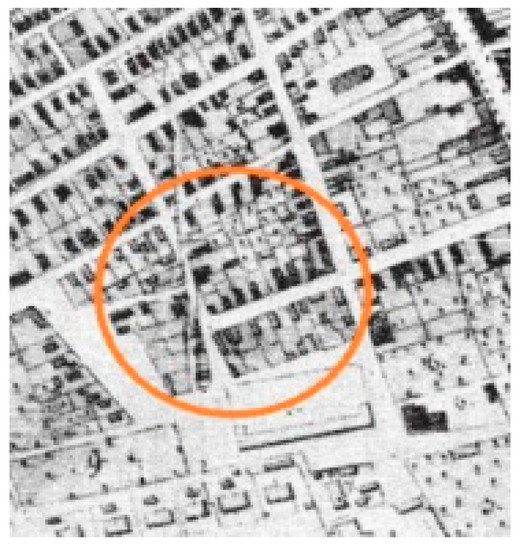

Carl Berthold’s city map from 1830 presents Zemun in detail (Figure 5). The regular street roster of the downtown nucleus clearly presents religious buildings that were grouped around the Great Square (Catholic Church), in the north-east part of the town (Orthodox Church), as well as the building of the Magistrate. In the south-western part of the town, on Jewish Street, one building is marked darker than the others. It is a building in the shape of letter L, with its longer face towards Preka Street. The wing spreads to the depth of the plot and runs parallel to Jewish Street. It is unclear from the drawing whether this small building touches Jewish Street too.27 We might assume that this part of Berthold’s city map represents the “Jewish community building”, where the rabbi, teacher and ritual slaughter lived, and a “school building” where, according to Gavrilović (1989, p. 85), “church and school activities were undertaken”. Besides the house and the school, this complex most probably contained a mikveh (ritual bath). We do not have much data on the ritual bath, although it is certain that it existed. The only evidence we have at our disposal are receipts for the five forint tax for “renting outgoing bath water into the fortress canal” for the years 1852, 1856 and 1859, which are currently preserved in the Jewish Historical Museum in Belgrade.28

Figure 5.

Carl Berthold’s Plan of the City of Zemun, 1830. The Jewish quarter is to the left, the Greek quarter is in the center and the Orthodox quarter is on the far right. The Catholic Church with the Great Square is underneath.

Further proof that our conclusion is correct and that the synagogue, as a free standing building did not exist until the sixth decade of the 19th century, is the application for “constructing a synagogue”, which was submitted in the name of the Jewish community to the Zemun Magistrate by Jakov Isak Albahari (Fogel 2007, p. 18) in May 1833 and was denied on June 10th of the same year by the Habsburg Slavonian General Command (Gavrilović 1989, p. 87).

In the second half of the 19th century, the living conditions of Zemun’s Jews improved somewhat due to the revolutionary events of 1848 in the Habsburg Empire marking the turning point in relations toward minorities: constitutional equality of all citizens, regardless of religious or any other affiliation, was announced. However, in the period that followed as a reaction to the revolution of 1848, known as Bach’s absolutism (1851–1860), pre-revolutionary anti-Jewish regulations were reintroduced, including the prohibition of real estate property ownership. Only in 1860 were these restrictions abolished with the restoration of constitutional order. However, it was not until 1867 that the Austrian law granted full equality to the Jews.

Nevertheless, the situation that the Jews of Zemun found themselves in was more difficult than in other parts of the Habsburg Empire. Namely, according to the order of the Habsburg Supreme Military Command of 1849, Jews from Hungary were forbidden to stay in the area of the Military Frontier since they had supported the Hungarian uprising. The Jews of Zemun sympathized with the Hungarians in the course of their revolution. A respected Jewish merchant from Zemun, Simon Herzl, was even jailed for 10 days for this political offence, but was released during the Jewish High Holidays after a request was submitted by the Jewish community (Ćelap 1958–59, p. 69). Because of such political circumstances, it is hardly probable that a synagogue was built in the course of those years—especially not in 1850 as stated by all previous researchers—knowing that such an application was denied 20 years earlier when circumstances were much quieter.

There is another detail that proves that the synagogue could not have been built before 1862. According to Toleranzpatent, formally cancelled in 1848 and in practice only in 1862, religious buildings of non-Catholic faith could have been built only if they did not resemble a church, i.e., they could not have any religious characteristics. Also, the religious buildings of tolerated religions were forbidden to have round windows—oculi. The synagogue in Zemun has both: oculi—one on the apse, above the Aron HaKodesh, and another one above the entrance. Visible religious characteristic—Tablets of the Ten Commandments—are on the roof of the building. Since the edifice is a two-story building some 13 m in height, it is higher than the surrounding one-story houses and the Tablets of the Ten Commandments are visible even outside of the Jewish quarter. Those two characteristics would have defined the building as a religious edifice, which was forbidden in those delicate times, according to the still valid Patent of Tolerance.

However, one decade later, the circumstances in the Habsburg Empire and in Zemun changed considerably. By August 1862, Jews were allowed to settle in Zemun without any restrictions. After more than a century of struggle between the Magistrate and the Jewish community of Zemun, the time for the construction of the Zemun synagogue had arrived.

4. Zemun Synagogue, Structure

According to Rabbi Ignjat Šlang, the Zemun synagogue was built in 1862 and was consecrated the same year by Leopold Löw, the rabbi of Szeged (Šlang 1939, p. 82).29 Although the synagogue was a result of efforts of the whole community, Rabbi Šlang informs us that two of the biggest contributors were Simon and Jakob Herzl, grandfather and father of Theodor Herzl (Šlang 1939, p. 81).30

Today the synagogue is situated at no. 7 of Yehudah Alkalay Street and has not been in active use since 1962.31 It occupies a plot 21 by 32.5 m at the corner of two streets. The entrance is on Preka Street. It is withdrawn 2.5 m from Preka and 4 m from Yehudah Alkalay Street. It is surrounded by a brick-and-iron fence.32

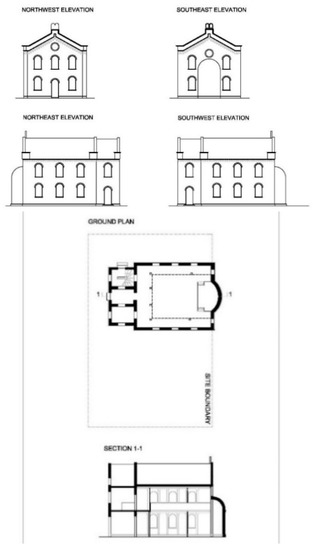

The synagogue is a single nave building with the apse orientated south-eastwardly, i.e., in the direction of Jerusalem.33 The dimensions of the building are 17.9 m × 11.4 m and the height is 12.9 m (Figure 6). A somewhat narrower entry front hall is placed on the north-west side of the building, with dimensions 9.7 m × 4.3 m. On both longitudinal sides of the building, there are single rows of three windows, both on the ground floor and on the first floor. All the openings (doors and windows) are arched and accentuated with simple profiles. The main facade is symmetrical, organized along the vertical axis and divided in three horizontal parts: the ground floor has one door and two side windows, three windows are to be found on the first floor and above them and on the top of the gable, there is a closed oculus. Above the main entrance door, there is an inscription in Hebrew block letters carved on pink stone. On the eastern side wall, on the ground floor level, there is another door and staircase leading to the women’s gallery. A similar opening is visible on the western side where today the opening is bricked-in so it is unclear whether it was another entrance to the gallery or a window.34 The Tablets of the Ten Commandments are located on the south east side of the roof.

Figure 6.

Zemun synagogue plan, cross section and elevation.

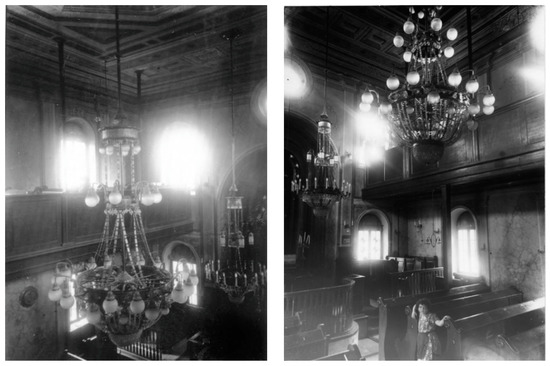

The interior of the building is a single space. Judging by the photo of the interior, the women’s gallery was made of wood (Figure 7a) and shaped like the letter U. The ceiling was coffered. The gallery was lit by a row of windows on the longitudinal sides of the building and by one on each side of the Aron HaKodesh (Figure 7b). Above the Aron HaKodesh, there was one oculus that provided light to the interior and there were also two windows on the ground floor.35 Three stairs led to the bimah, which was situated in front of the Aron HaKodesh and separated from the central area by a nice balustrade. According to Klein, such a disposition of the synagogue’s floor plan—where the bimah is situated in front of the Aron HaKodesh—indicates a period of construction after 1848 and is characteristic of Neolog synagogues (Klein 2017, p. 107). One cannot state with certainty whether the Zemun synagogue was Neolog or Orthodox, although some characteristics indicate that it was Orthodox.36

Figure 7.

Zemun synagogue interior before WWII.

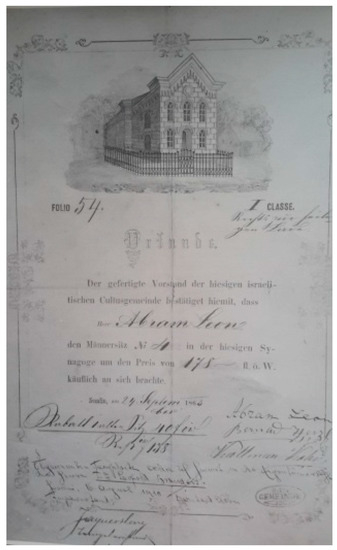

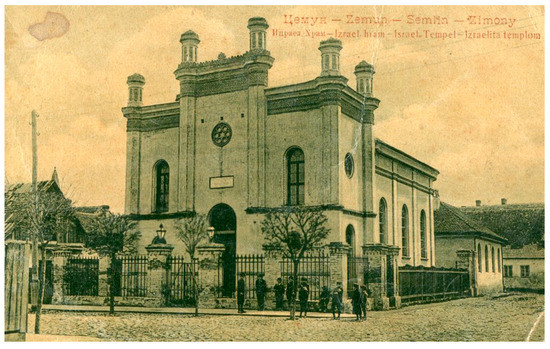

The synagogue is a brick building, which was subsequently plastered. Compared to the oldest visual testimony at our disposal for this building—dating back to 1863—it never underwent any external changes37 (Figure 8). The interior of the building, however, was grossly altered and adapted to its new function. The ceiling was lowered, rendering longitudinal galleries and the first floor invisible from the inside. In front of the apse, an elevation—which once was the bimah—is still visible.

Figure 8.

Receipt showing that Leon Abram bought the right to sit in the second row of the men’s section of the synagogue in 1863.

The shape of the synagogue building is simple. It follows the shape of secular architecture and resembles city houses. It only slightly deviates from the look of surrounding houses due to its size (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

General view of Zemun Jewish quarter from Ćukovac hill.

The common style identification of the Zemun Ashkenazi synagogue is related to the modest repertoire of its outside decoration. Namely, along the roof line, there is a typical Rundbogen frieze that connects this synagogue, style-wise, with Romanticism. The Rundbogen style38 is a common decoration in synagogues of the Habsburg Empire, especially with “factory-hall type synagogues” to which this synagogue belongs according to Rudolf Klein (2017, p. 304).39 As a romantic expression of striving towards national style,40 this decorative repertoire was the most universal, i.e., the least national: it was rarely used on Christian sacral edifices and therefore, in a non-intrusive manner, expressed the difference. This is why Jews mostly used it.41

There were many reasons why Rabbi Yehudah Alkalay (1798–1878), the Zemun chacham at the time, and his community decided to build this type of synagogue: more than a century of restrictive policies towards Jews enacted by the Zemun Magistrate, the size and limited wealth of the Zemun Jewish community, the placement of the building at the edge of the town and, as we assume, an Orthodox denomination.

Here we must stress another very important fact. Ashkenazim made up the majority of Zemun’s Jewish population from the beginning of their settlement in town. However, over the following two centuries, depending on events in neighboring Belgrade, a Sephardic presence began to be seen. However, Sephardim never comprised more than half of the community membership. Despite many authors assuming that during Rabbi Alkalay’s time two separate Jewish communities existed in Zemun (Štajner 1970, p. 58; Weisz 2013, p. 47), existing documents suggest otherwise. The very first documents from Zemun’s archive from 1753 states: although “four of the 19 families (first to settle in Zemun) were marked as Turkish and the rest as German Jews,” they made up “one community.”42

Indirect testimony that only one Jewish community existed in Zemun until 1871 is a document from the mid-19th century that is now kept in the Jewish Historic Museum in Belgrade (Figure 8). It is a receipt showing that Leon Abram bought the right to sit in the second row of the men’s section of the synagogue, dated September 1863.43 Judging by the name and family tradition, Leon Abram was of Sephardic origin. His ancestor, with the same name, moved to Zemun around 1795 and in 1800 already owned a house at number 142.44 The question can be asked: if another community existed, why would a Sephardi rent a seat in an Ashkenazi synagogue? The assumption is that only one Jewish community existed in Zemun at the time the synagogue was built. Further evidence of this assumption can be seen by the heading and the seal on this very document where it is written Israeli Religious Community (Israelitische Cultusgemeinde), as opposed to documents from the end of the 19th century where the Ashkenazi community was called the German-Israel Religious Community (Deutsch Israelitische Cultusgemeinde, Semlin).45

4.1. Zemun Synagogue, Inscription

There is an inscription above the entrance door (Figure 10), carved into pink stone, with the Hebrew words:וְעָשׂוּ לִי, מִקְדָּשׁ; וְשָׁכַנְתִּי, בְּתוֹכָם “Have them make a sanctuary for me and I will dwell among them”, which is a quotation from the Second Book of Moses (Shemot 25:8–9).

Figure 10.

Inscription above the main entrance to the Zemun synagogue.

Zemun Synagogue, Inscription, Meaning

Although up until now, to the best of my knowledge, no one has systematically collected and explained the inscriptions above entrances to synagogues, there are some local parallels that can now be drawn, which are very interesting.46 Christian churches have their patron protector represented above the main entrance. Usually this patron is chosen by the church founder and quite often this choice represents his various (religious or even political) attitudes. Contrary to that, the inscription that adorn the entrance of a synagogue is usually determined by the entire Jewish community. Thus, the choice of the specific verse from the Tanakh might indicate internal intentions of the community, its attitudes, aspirations and perspectives.

Since Rambam’s time until today, one can find a large number of explanations for the biblical verse that adorns the entrance to the Zemun synagogue. As said previously, that quotation refers to Shemot 25:8–9 and is related to the parashat Terumah.47 Some of its interpretations might be interesting for our analysis.

Mikdash (מִּקְדָּשׁ) originates from the makom kodesh root and means the Holy place. In a way, every synagogue is a mikdash, although the most famous one is Beit HaMikdash (בֵּית־הַמִּקְדָּשׁ) - The Jerusalem Temple. According to sages, the Jerusalem Temple is the one that will descend from the sky or be built in Jerusalem at the end of times.48 On the other hand, mishkan מִשְׁכַּן (Tabernacle), which is also mentioned in this parashat, originates from the shekhinah שכינה—Divine Presence—the place where God is present and where He will really live together with His chosen people.49 Mikdash is in many ways always a separate, holy area. Mishkan, however, can exist only when believers, united in prayer and celebration of God, invite His presence to the place where they are. Thus, according to some explanations, only human activity, united action, can turn a mikdash into a mishkan.50

This possible explanation brings us to several interesting topics such as: the Temple in Jerusalem, activism and the return to the Land of Israel, which at the same time, are also the central themes of political proto-Zionism.

There is no doubt that the choice of this inscription above the entrance to the Zemun synagogue is connected to the most important religious personality of the Zemun Jewish community—Rabbi Yehudah Alkalay. In 1862, at the time the Zemun synagogue was being built, Rabbi Alkalay had lived, served and taught Judaism in Zemun for almost 40 years.51

Through his religious activities and work as a writer, Alkalay initiated the idea of the return to Eretz Israel. In 1839, he published Darhe ha’am, the Hebrew grammar book advocating for the revival of the Hebrew language as a national language.52 In the following years, he developed his ideas based on an ancient idea of collective teshuvah, understood as a return to the Holy Land first formulated in his book Minhat Yehudah, published in Vienna in 1843.53

Rabbi Alkalay did not stick only to the theory. In the decade prior to the construction of the Zemun synagogue, his activities—both theoretical and practical—reached their climax: In 1852 in London, he founded The Society for Settling in Eretz Israel for settling in Palestine and to assist endangered Jews. One of his most influential works, in which he describes the overall system for the colonization of Palestine, Goral la Adonai was published in Vienna in 1857. He also participated in the organization of Alliance Israelite Universelle with Montefiore and Crémieux in 1860 in Paris.

For that reason, we are of the opinion that the inscription above the entrance to the synagogue reveals a lot about the Jewish community of Zemun of those times and about its leader. It explains the atmosphere the community lived in, tells us about the money that was invested in the temple, about Zemun’s Jews self-perception in multi-ethnic Zemun, but mostly about the activism that Rabbi Alkalay was involved in. We know that Alkalay invested all the money he earned into publishing his books and in the realization of his theoretical and practical ideas about the return to Eretz Israel. Towards the end of his life he was penniless, so much so that his two daughters were left without dowries (Štajner 1970, p. 65).

For that reason, we can assume that the choice of verses for the Zemun synagogue inscription might be seen as a pars pro toto expression of the centrality of the idea of Mikdash (understood primarily as Beit HaMikdash in Jerusalem) and as such, as an abbreviated formula or motto of not only Alkalay’s personal beliefs, but of political proto-Zionism in general.

Alkalay’s religious fervor and political activism were contagious: they “infected” other members of Zemun’s Jewish Community, especially Simon Herzl, and through him, his grandson Theodor (Weisz 2013, pp. 47–51).

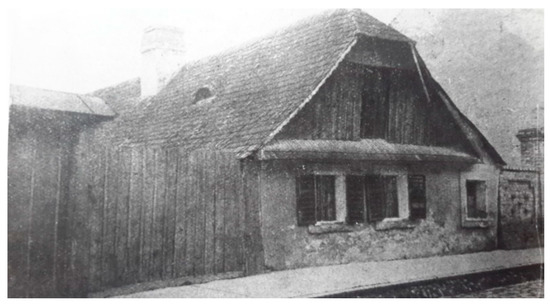

Simon Herzl (1797–1879) was a respected Zemun merchant, member of the community board, descendant of a glass-cutter Naftali Herzl who moved to Zemun in the mid-18th century (Šlang 1939, pp. 85–86). Simon and his family lived in his parents’ family house at Apostelgasse 253 (Figure 11).54 He was married to Rebecca, the daughter of a Zemun chacham named Bilitz. They were probably married around 1830 (Šlang 1939, p. 84).55 Although there are no precise data, it is probable that Rabbi Alkalay officiated at the marriage ceremony as we have already shown that there was only one Jewish community and one synagogue in Zemun in those times. Therefore, Rabbi Alkalay and Simon Herzl were acquaintances for at least 40 years. Simon Herzl probably had one of the first copies of Goral la Adonai from 1857, in which Alkalay precisely laid out his plan for the “return of Jews to the Holy Land and the resurrection of Jerusalem’s glory” (Štajner 1970, p. 62).56 Simon’s son, Jakov, was born in Zemun in 1831. In the mid-19th century, Jakov moved to Budapest and started his own family. We know that he often travelled to Zemun and that he, on more than one occasion, contributed to the synagogue (Šlang 1939, p. 82).57 It seems that Jakov’s son, Theodor (Zeev) Herzl, Simon’s grandson, also often visited Zemun, since in 1903, he was issued citizenship of Zemun58. Based on these historic and archival evidences, the connection between Alkalay’s proto-Zionistic ideas and Herzl’s Zionist ideas seems very probable, which is a connection that some authors have recently been paying attention to.59

Figure 11.

The Herzl family House in Zemun, once Apostelgasse 253, before 1910.

5. Conclusions

All restrictions concerning Jewish settlement in Zemun were lifted in 1862, the same year that the Zemun synagogue was completed.

In February 1867, Emperor Franz Josef acknowledged full equality with other religions for the Jews; in 1871, the Military Frontier was cancelled and one year later, Zemun became Liberae civitater regiae—a free town. The same year, a Zemun builder Josef Marks built a Sephardi synagogue in Zemun’s Jewish quarter (Dabižić 1999, pp. 145–51), a nice oriental-looking Sephardi temple, classified by Klein (2017, p. 643) as a “Solomon Temple” type synagogue. Although it was built after the Emancipation was announced, the building was withdrawn from the street and fenced off (Figure 12). The inscription on its façade was the product of a different inspiration as compared to the one on the first Zemun synagogue: תפילה יקרא לכל העמי כי ביתי בית “For my house will be called a house of prayer for all nations” (Isaiah 56:7). It is obvious that its more universal and political message was directed beyond the Jewish quarter which, due to political changes and Emancipation, was no longer as secluded from the rest of the town.

Figure 12.

Josef Marks’ Sephardi synagogue, Zemun 1871.

Building of the Sephardi synagogue was the last stage of emancipation of Jews in Zemun and also the last stage of the development of the proto-Zionistic idea. Theodor Herzl, a Zemun citizen himself, would further develop this idea 25 years later and would present it in his own work. At the same time, upon construction of the second synagogue, the Jewish quarter got its own small square and the town of Zemun got another defined religious focal point in its south-west part (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Jewish quarter of Zemun in 1909.

6. Coda

We unintentionally confirmed the identification of the Zemun synagogue with the Jerusalem Beit HaMikdash, by the fact that the members of the Society of Serbian Templars, official name of which is Ordo Supremus Militaris Templi Hyerosolymitani, today hold their meetings on the first floor of the Zemun synagogue. For them now, as was the case with Rabbi Alkalay, Simon Herzl and the small 19th century Zemun Jewish community, Zemun’s synagogue represents Beit HaMikdash—The Holy Temple of Jerusalem.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The text was translated by Brane Popović and proofread by Rachel Chanin and Joel Fisher. Ana Mihailović provided drawings of the ground plan and section of the synagogue (Figure 6). Aleksandra Dabižić gave permission for publication of Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 13 from her text (Dabižić 2014). Tijana Kovčić helped in archival research. The Jewish Community of Zemun provided Figure 7. Figure 8 and Figure 11 are from the Jewish Historical Museum in Belgrade and Figure 12 is in the public domain. Figure 3, Figure 9 and Figure 10 were created by the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| IAB, ZM | Historical Archives of Belgrade, Zemun Magistrate |

| JIM | Jewish Historical Museum Belgrade |

References

- Aćimović, Ljiljana. 2010. Pogled preko reke, Fotografije gradskog poglavarstva Zemuna tridesetih godina 20. veka. Beograd: Muzej grada Beograda. [Google Scholar]

- Blitz, Rudolph C. 1989. The Religious Reforms of Joseph II (1780–1790) and their Economic Significance. Journal of European Economic History 18: 583–94. [Google Scholar]

- Borovnjak, Đurđa. 2013. Verski objekti Beograda, projekti i ostvarenja u dokumentima Istorijskog arhiva Beograda. Beograd: Istorijski Arhiv Beograda, pp. 84–85. [Google Scholar]

- Borovnjak, Đurđa. 2017. Synagogues in recent Serbian Architecture. In Serbian Studies 28. Bloomington: Slavica Publishers, pp. 127–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ćelap, Lаzar. 1958–59. Jevreji u Zemunu za vreme vojne granice. In Jevrejski Almanah. Beograd: Savez jevrejskih opština Jugoslavije, pp. 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Mordechai Z. 2011. Interpreting the resting of the Shekhinah: Exegetical implications of the theological debate among Maimonides, Nahmanides and Sefer Ha-Hinnukh. In The Temple of Jerusalem: From Moses to Messiah. Edited by Steven Fine. Leiden: Brill, pp. 237–75. [Google Scholar]

- Dabižić, Miodrag. 1967. Staro jezgro Zemuna, Istorijska i urbana Celina. Zemun: Narodni muzej Zemun i Zavod za zaštitu spomenika Beograd. [Google Scholar]

- Dabižić, Miodrag. 1987. Zemun. Beograd-Zemun: Turistička štampa. [Google Scholar]

- Dabižić, Aleksandra. 1999. Sefardska sinagoga u Zemunu. In Nasleđe 2. Beograd: Zavod za zaštitu kulturnog nasleđa Beograda, pp. 145–51. [Google Scholar]

- Dabižić, Miodrag. 2013. Prilog prošlosti gradskog parka u Zemunu od sedamdesetih godina XIX veka do 1914. godine. In Nasleđe 14. Beograd: Zavod za zaštitu kulturnog nasleđa Beograda, pp. 145–53. [Google Scholar]

- Dabižić, Aleksandra. 2014. Značaj kartografskih izvora za proučavanje razvoja Zemuna. In Građa za proučavanje spomenika kulture u Vojvodini XXVII. Novi Sad: Pokrainski zavod za zaštitu spomenika kulture Vojvodine, pp. 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel, Danilo. 2007. Jewish Community in Zemun, Chronicle (1739–1945). Zemun: Jewish Community of Zemun. [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilović, Slavko. 1989. Jevreji u Sremu u XVIII i prvoj polovini XIX veka. In Jevreji u Zemunu i Petrovaradinskoj regimenti. Beograd: SANU, pp. 78–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Benjamin J. 2007. Religious Conflicts and the Practice of Toleration in Early Modern Europe. London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Rudolf. 2017. Synagogues in Hungary 1782–1918. Budapest: Terc. [Google Scholar]

- Маркoвић, Петар. 2004. Земун oд најстаријих времена па дo данас. Земун: Мoстарт. [Google Scholar]

- Markuš, Zoran. 1992. Kuća u Apostelgasse 253. In Zbornik 6. Beograd: Jevrejski istorijski muzej. [Google Scholar]

- Rodov, Ilia. 2015. Hebrew Inscriptions. Visual Arts and Architecture: Jewish Art. In Encyclopedia of the Bible and its Reception: Halah—Hizquni. Edited by Dale C. Allison Jr., Christine Helmer, Volker Leppin, Choon-Leong Seow, Hermann Spieckermann, Barry Dov Walfish and Eric J. Ziolkowski. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, Volume 11, cols. 624–31. [Google Scholar]

- Shallev-Eyni, Sarit. 2004. Jerusalem and the Temple in Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts: Jewish Thought and Christian Influence. In L’interculturalita dell’ebraismo a cura di Mauro Perani. Ravenna: Longo, pp. 173–91. [Google Scholar]

- Sitte, Camillo. 1967. Umetničko oblikovanje gradova. Beograd: Građevinska knjiga. [Google Scholar]

- Šlang, Ignjat. 1939. Zemunski preci Teodora Hercla. In Jevrejski narodni kalendar 5700. Beograd: Biblioteka jevrejskog narodnog kalendara, pp. 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Štajner, Aleksandar. 1970. Jehuda Haj Alkalaj (1798–1878). In Jevrejski Almanah. Beograd: Savez jevrejskih opština Jugoslavije, pp. 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Gerhard, and Harald Olbrich. 1968–78. Eintrag Rundbogenstil. In Lexikon der Kunst. Architektur, bildende Kunst, angewandte Kunst, Industrieformgestaltung, Kunsttheorie (in German). Leipzig: Seemann, Band 6. p. 293 ff. [Google Scholar]

- Škalamera, Željko. 1966. Staro jezgro Zemuna I. Beograd: Zavod za zaštitu spomenika kulture grada Beograda. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz, Georges Yitshak. 2013. Theodor Herzl: A New Reading. Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Zemun was the center of a large and multifaceted trade: goods from Italy and Germany arrived by the Sava River and from Hungary, France and England by the Danube River; Dutch goods came by land (Škalamera 1966, p. 14. Dabižić 2014, p. 133). |

| 2 | The word used in archive documents for Zemun’s quarantine is Kontumaz. |

| 3 | IAB, ZM, Rathausprotocoll 22-1756. According to archival documents at the Zemun Magistrate (where the names of Jews who settled there are listed), all of them moved to Zemun from Belgrade in 1739. There were four Jews of “Turkish“ decent and 15 Ashkenazi families. See (Ćelap 1958–59, p. 60). |

| 4 | IAB, ZM, RathsProtocol, F. II, XXIV, 1771. |

| 5 | All of the Zemun churches are rather far away from the Jewish quarter. The closest are the Franciscan monastery and the Kontumaz chapels that were, due to their “secluded” function, fenced off and thus “invisible” in the town structure. |

| 6 | Zemun is situated on the right bank of the Danube. |

| 7 | Bertold’s plan is the first plan to contain street names officially adopted in 1816–1818. See (Dabižić 1967, p. 16). |

| 8 | Škalamera (1966, p. 14) says, without quoting the exact source, that already 18th century documents of Zemun Magistrate mention Jewish Street. |

| 9 | Sokak is Turkish for small street, equivalent to German Gasse. |

| 10 | More on the chronology of Zemun’s street names in (Škalamera 1966, pp. 14–17). |

| 11 | Based on archival documentation found at the Zemun Magistrate, we know that 15 Jews lived in their own houses in Zemun in 1756. However, we cannot determine their exact location, although we know that the majority of them lived in houses numbered from 137 do 162. See (Gavrilović 1989, pp. 93–96). |

| 12 | “Everything that came from Turkey had to pass through the Kontumaz: people, animals, goods, even letters. According to descriptions and documents, large loads of various goods could be found in Kontumaz warehouses. A contemporary witness compared Zemun’s Kontumaz to an Eastern bazaar or bezistan because of the numerous storerooms, mixture of languages and various items: wool, cotton, oriental red-dyed yarns, raw silk, fabrics, Persian rugs, Indian shawls and other dyed goods, Macedonian honey and wax, oils coming from Provence and other places, Arabian coffee, rice, Tokay and Cypriot wines, citrus fruits, spices, various oils and perfumes, incense, turtle shells, gold and silver ingots and pearls from Istanbul” (Dabižić 1987, p. 77). |

| 13 | Due to the unpleasant smell, raw hide processing was forbidden within the town and on the river bank. |

| 14 | It is necessary to mention that the same hierarchical system was true in Zemun during the previous Turkish period: instead of the Catholic Church and school, there was a mosque and a school on the central square. |

| 15 | Towards the end of the 18th century, most of the Serbian houses in Zemun (including the most prominent among them, the Karamata family house) were grouped around the Orthodox St. Nicolas Church. The Aromanian quarter developed around the Greek Church of St. Mary, near the homes of Naum Ičko (Bežanijska Street 18), Afrodita Bialo (Main Street 45) and Gina Vulko (Main Street 18). This distribution one should take into account only conditionally since due to religious tolerance, Christian communities of the central Zemun were rather intertwined. The German colony of Franzstal was separate since its inception and maintained its own language and national and confessional uniqueness until World War II. |

| 16 | Rudolf Klein (2017, p. 657) only mentions the Zemun synagogue in the catalogue of his book on synagogues in Hungary. The Ashkenazi synagogue in Zemun can be found in the Bezalel Narkis Index of Jewish Art, under n. 20517. http://cja.huji.ac.il/browser.php?mode=set&id=20517 (accessed on 17 October 2019). However, the technical drawings presented there are from 2001 and show the modern apperance of the synagogue building, not the original one. |

| 17 | Until the Sephardi synagogue was built in Zemun in 1871, this synagoge was the only synagogue in Zemun. Regretfully, it returned to this status again in 1947 when the Sephardi synagogue was demolished. |

| 18 | For this statement, Škalamera does not offer any documentation. |

| 19 | Recently Đ. Borovnjak addressed this issue twice but with scarce results. In the first publication (2013, p. 84) speaking about the Askhenazi synagogue she refers to a photo that represents the Sephardi synagogue. In the second publication (2017, p. 129, f. 3), she mixes two synagogues again. Describing Ashkenazi synagogue she refers to the photo of the Sephardi synagogue from Ljiljana Aćimović’s book. |

| 20 | IAB, ZM, 10, K. 20, 17. 2.1774. |

| 21 | IAB, ZM, K. 1465, 1791. f.XXXVI, n. 59. |

| 22 | Zemun Magistrate archival documents relate serious tensions between the Jewish community and the Magistrate relating to even the most basic rights including the right to live and work in Zemun. Thus, it seems unlikely and hardly possible that the synagogue was built in that period. It is more probable that one of the existing buildings was adapted to serve as a synagogue. |

| 23 | The Patent of Toleration or Toleranzpatent was an act issued by the Austrian Emperor Joseph II in October 1781. Among other things, it enabled non-Catholic Christian denominations (Orthodox and Protestant) within the Habsburg Empire excercitium religionis privatum the right to hold religious services in private homes. The looks of the buildings where such non-Catholic services were performed was precisely specified: buildings should not have bells, direct entrance from the street and no external religious characteristics. Although Joseph II produced an Edict on Tolerance thet referred to the Jews as early as the beginning of 1782, it did not contain any indication on the apperance of Jewish cult edifices. Therefore, the above-mentioned regulation was also applied to synagogues (Kaplan 2007, p. 192). |

| 24 | Such semi-clandestine houses of worship—Kaplan (2007, pp. 192–94) calls them schuilkerk—used by religious minorities (Christians and Jews) were to be found “inside houses” and were common in Europe as a way “for governments to permit a degree of religious tolerance”. |

| 25 | Special act of 8.1.1773 on limited settling of Jews within Zemun community (Ćelap 1958–59, p. 64, f. 41, refers to the document IAB, ZM, RathsProtokoll, f.XVI, n. 38, 1796, that is missing today). Some time later, towards the end of 1781, Joseph II introduced a rule which stipulated that “Jews should not spread further in his land i.e. the Habsburg Empire”. That was further confirmed by the Zemun community’s decision that: “not a single Jew, except for those with privileges (the archival documents call them Schützjuden) can settle in Zemun. ” IAB, ZM, RathsProtokoll, f.XXVIII, 15.12. 1781. |

| 26 | Already in 1755, only two years after Empress Theresa granted settling privileges to Jews, the Zemun Magistrate issued a decision that “Jews are not to be considered citizens as all other Christian contribuents, but only as a tolerated community”(Ćelap 1958–59, p. 61, f.9). Since Zemun was at that time considerably multi-ethnic, although primarily a Christian town, attacks on Jews did not only come from one side. According to Lazar Ćelap’s (1958–59, p. 62) research, the basis for intolerance against Jews among Zemun’s Germans was mostly based on religion, while Serbs and Aroumanians felt that Jews were threatening them economically as competition. Towards the end of the 18th century, conflicts between Christians and Jews became more frequent and even escalated in 1792. The Magistrate, upon the directive of the Military Command, investigated the case and reported on 8.5.1792 that no formal dispute between the Jewish and the Serbian community in Zemun was determined. After that, the Magistrate ordered, promising to issue strict punishments that “all must refrain from abusing Jews”. IAB, ZM, K.1502-1792, F. LXIV, 33. |

| 27 | It is interesting that the disposition of this building corresponds to the present day synagogue. |

| 28 | JIM, Zemun: 8–10, reg.n.1152/53. |

| 29 | It is important to note that Šlang wrote this text in 1939 based on Zemun synagogue books that were destroyed during WWII. |

| 30 | Simon Herzl gave a gift of 51 forints and 48 kreuzer, and Jakob Herzl gave 44 forints. |

| 31 | The Jewish Community of Zemun suffered greatly during the Holocaust. The records show that 574 community members were taken to Jasenovac or Stara Gradiška concentration camps in Croatia. After WWII, two aliyot left for Israel. Since just a few Jews remained in Zemun, the community decided to sell the synagogue building to local authorities in 1962 under the condition that it was to be used for cultural events. The building first became a warehouse, then a disco-club, and since 2005, a non-kosher restaurant. In accordance to the Special Law on Restitution of Jewish Property for the Victims of Holocaust with No Legal Heirs of 2016, an application was submitted for it to be returned to the community in exchange for another building. However, the Court of Appeal rejected that application in October 2019. |

| 32 | The building’s appearance is in line with the strictly applied regulation, dating from the reign of Emperor Joseph II, which decreed that non-Catholic religious buildings could not have an entrance directly on the street. Such buildings also needed to be separated from the street by a fence. Cf. (Kaplan 2007, p. 192). |

| 33 | Although the position of the apse of the synagogue is largely dictated by the street roster and in synagogues in Hungary is mostly towards the East, according to Klein (2017, p. 53), the orientation directly towards Jerusalem is a characteristic of Orthodox synagogues. |

| 34 | This opening is clearly defined and according to the overall symmetry of the building, it is more likely that it represents a door which was once the second entrance to the women’s gallery. |

| 35 | After 1962, this part of the building underwent some structural changes with the construction of the second floor that divides that space into two distinct levels. |

| 36 | Since the entrances to the women’s gallery were separated from the men’s, one can assume that the synagogue was Orthodox. Also, the synagogue did not have the small decorative towers—“minarets,” which are usually associated with “factory hall type” synagogues. According to Klein (2017, p. 304), a lack of this decorative element is characteristic of Orthodox synagogues. |

| 37 | JIM, K.17, reg. n.1155/53. The header of the document represents the synagogue as built from bricks. However, today, the synagogue is covered with plaster. |

| 38 | Rundbogenstil (round-arch style) is a nineteenth-century historic revival of neo-Romanesque architecture popular in some countries of Central Europe. Cf. (Strauss and Olbrich 1968–78, p. 293). |

| 39 | “The factory-hall type synagogue emerged in Hungary in the 19th century but is rooted in architectural traditions of the Habsburg Empire. Before the Emantipation synagogues could not represent their religious purpose on their facade and therefore, they followed the forms of secular architecture.” See more: (Klein 2017, pp. 302–17). |

| 40 | About serach for the style in Hungarian synagogues built in the period of Romanticism see (Klein 2017, p. 110). |

| 41 | Such a definition of style is especially prominent in the local architectural context since all of the Zemun churches—either Orthodox or Catholic—were built in Baroque style and the Magistrate (Town hall) building was built in Classicist style. |

| 42 | IAB, ZM, Raths Protocoll, f.I, n.1. pro anno 1755. |

| 43 | JIM, K.17, reg.n.1155/53. |

| 44 | According to an excerpt from the Zemun Magistrate, it seems that Leon Abram moved to Zemun around 1795 since the census data shows that he had spent the previous 20 years in Zemun (Gavrilović 1989, p. 94). Miss Barbara Panić, curator of the Jewish Historical Museum in Belgrade, is a direct decendant of Leon Abram, through her maternal relatives. |

| 45 | JIM, K. Zemun, reg.n. 1186/54. |

| 46 | Although many scholars such as Shalom Sabar, Bracha Yaniv, Ilia Rodov, Sergey Kravtsov and Bezalel Narkiss addressed Jewish inscriptions (either in Jewish or Christian Art) in their work, to the best of my knowledge no one has systematically collected and explained the inscriptions above entrances to synagogues in Central Europe. My text that deals with this topic is in preparation. The Sephardi synagogue of Zemun (1871), as well as the nearby Novi Sad synagogue (1906), had the inscription based on Isaiah 56:7. The Zagreb synagogue (1867) had an inscription from Psalms 118:6. The Belgrade Askhenazi synagogue (1926) does not have any inscription at all and for both Belgrade Sephardi synagogues, we do not have any information because they were destroyed after WWII. About other inscriptions, see: (Rodov 2015, cols. 624–31). |

| 47 | https://www.etzion.org.il/en/parashat-teruma-and-let-them-make-me-sanctuary-i-may-swell-among-them (accessed on 13 October 2017). |

| 48 | The idea that the Third Temple “will descend fully formed from heaven“ was further adopted by Rashi in his commentary to the Sukkat Treatise of the Babylonian Talmud (41a) (Shallev-Eyni 2004, p. 177). On the other side, Maimonides declared that the Third Temple “will be built by the human hands of the Messiah” (Code of Law, Sefer Mishpatim, 11:1) and “if he succeeded and built the Temple, he is certainly the Messiah” (ibid., p. 178). |

| 49 | Few subjects in Judaism are as central as the notion of God’s presence, “dwelling” in the Holy Temple in Jerusalem. See (Cohen 2011, pp. 237–75). |

| 50 | http://www.rabbidanny.com/2016/02/two-minutes-of-torah-terumah-more-than.html (accessed on 13 October 2017). |

| 51 | Rabbi Yehudah Alkalay (1798–1878) was a descendant of the famous rabbinic family from Thessaloniki. Originally from Alkala, Spain, the family settled in Thessaloniki after the Expulsion. Rabbi Judah was born in Sarajevo in 1798 (5558 in the Jewish calendar). From a young age, he was educated at the Chacham Yeshiva in Jerusalem. He was a kabbalist. He spent almost half a century (1825–1874) in Zemun as a school teacher and rabbi. While in Zemun, he wrote 53 publications (Štajner 1970, pp. 55–66). |

| 52 | Darhe ha’am was printed in Belgrade’s State Printing House in 1839. It is interesting to mention Weisz’s idea that in the 1830s, Theodor Herzl’s father, Jacob, was a student of Alkalay’s at the Zemun cheder and he probably used this textbook to learn Hebrew (Weisz 2013, p. 47). |

| 53 | Weisz (2013, pp. 73–74) was the first author to draw attention to the relationship between Rabbi Alkalay’s teshuvah idea of the Return to Eretz Israel and Theodor Herzl’s central idea of Heimkehr zur Judenthum (Return to Jewishness). |

| 54 | The Herzl family house has not existed since 1910, but the site where it was standing is known; the current address is Gundulićeva Street 15, about 100 meters from the synagogue (Markuš 1992, pp. 245–48). Photo source: JIM, K. Zemun 1, reg. n. 1435. |

| 55 | Both Simon and Rebbeca Herzl are buried in Zemun’s Jewish cemetery. |

| 56 | Alkalay’s Goral la Adonai is a detailed step-by-step guide about how to re-establish the Jewish state in Israel, by introducing Hebrew language, gradually purchasing land and returning to agricultural production. |

| 57 | On the occassion of consecration of the Sefer Torah in 1879, Jakob Herzl donated silver rimonim for the Torah, in memory of his deceased sister Rezl (Šlang 1939, p. 82). |

| 58 | IAB -100- K903. According to the census list of citizens of Zemun, which is kept in the Belgrade City Archives (Census list without date for Gundulićeva Street 15),“Todor Herzl,” “writer,” (living) “in Paris” was granted Zemun citizenship (document n.7859/903). This document was issued as a proof of citizenship that represents the original citizenship of the whole family. I am grateful to Michal Brandl, Ph.D. at the Department of Judaic Studies of the Faculty of Philosophy in Zagreb for sharing her explanation of the concept “zavičajnost” (citizenship) with me. |

| 59 | Until recently, the connection between Rabbi Alkalay and Theodor Herzl’s ideas was merely based on the facts that they were both connected to the Zemun Jewish community. Weisz was the first author to recognize the ideological connection between Rabbi’a Alkalay’s idea of teshuvah as a collective return to the Land of Israel and Theodor Herzl’s central idea of the return to the Place. See more: (Weisz 2013, pp. 47–51, 73–74). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).