1. Introduction

In September 1922, the tenth International Congress of Architects was held in Brussels, the first assembly of professionals in the discipline since the end of the First World War. German and Austrian nationals were not invited by the organisers, who represented the winning allied powers in the recent conflict. France, Italy, the United Kingdom, Denmark, the United States, Mexico, Uruguay, The Netherlands, Sweden, Poland, Switzerland and Japan sent architect delegates to participate. Spain was also invited and was officially represented by Luis María Cabello y Lapiedra. Thanks to the account of proceedings written by this Madrid architect and critic, published that year in the journal

Arquitectura (

Cabello 1922, p. 426), we know that one of the important points discussed at the congress related to the female architect:

Today, when a wide field of possibilities are open to women’s talents, which has been amply demonstrated in the areas of public administration, and in the exercise of noble professions such as lawyer and doctor, and of course Music and the Fine Arts, there is no just reason to close our doors to the practise of architecture by the female sex.

It might be argued, whether justified or not, that the exercise of the profession, having to climb up scaffolding and stairs, is not suited to a woman’s physical situation and her customary attire: but what cannot be doubted is that the practice of drawing, the study of ornament, the same arrangement and tracing of plans, in short, the work of assistants in a studio, can be performed by a female colleague to a high standard, and it is part of her aptitude and qualities to appreciate and feel beauty, which in a woman is more highly developed or is felt with greater intensity than would be the case in a man.

In the United States several female architects are already to be found; the same is also true in France. The same might be said of Italy and some of the Latin American republics. In Spain we have draughtswomen—the Compañía de Teléfonos de Barcelona employs women for drafting and producing its plans, with excellent results. What are we waiting for?

The Congress, however, didn’t provide any real solutions. It considered that it would not be necessary to grant official recognition to the female architect, and agreed to pass the matter on to be studied and deliberated by the Central Committee of the International Congresses.

In the light of this summary published by the Spanish delegate, it appears that the congress participants were not opposed to admitting women into architectural practice, but neither did they feel any kind of obligation to publicly recognise female architects who they already knew were practising. It is not possible to discern if this idea that female architectural practice was solely confined to technical drawing and other studio tasks was a personal opinion, or of a quorum of the congress. If we acknowledge that architectural creation is an inherent part of an architect’s work, implicitly, this is not apparent in the woman’s case. We may deduce from the account that women architects would remain excluded from the management of projects and the possibility of creation.

Almost a decade after the abovementioned congress, the doctor Gregorio Marañón, compatriot of Luis María Cabello, published a book in several languages which left no doubts as to its interpretation. He summarised the gender-specific functional characteristics of men and women in a full page graphic, which purported that compared to men, women were “more sensitive to emotional stimuli but were less disposed towards abstract and creative tasks” (

Marañón [1926] 1931, p. 35). In this context, it is understandable that the first Spanish female graduate from a School of Architecture, Matilde Ucelay Maórtua, often felt at a disadvantage, and not only for being outnumbered by men, but also because, as she would admit later, one professor had discriminated against her while passing a mandatory subject simply because of her sex (

Sánchez de Madariaga 2012, p. 25).

In 1931, the same year in which Matilde Ucelay began her architecture studies in Madrid, a remarkable exhibition was inaugurated at the Lyceum Club Femenino in the Spanish capital titled

Dibujantas. The women featured were not the draughtswomen of the Barcelona telephone company, to whom Cabello referred, but artists united together under their own name. Some of them had already appeared in exhibitions of the period, yet always relegated to the background and obliged to endure a paternalist and condescending criticism that often reduced them to the level of “señoritas” delicately painting, as if it were all merely an amusing pastime. Only a few of them merited more serious criticism, but in these cases, the quality of their work was evaluated by its conformity to male conventions (

Álix and González 2019, p. 9).

These illustrators, who needed to perform their work to earn a living, as many of them were working at the magazine Blanco y Negro, had joined together for the exhibition to protect themselves and to acquire greater visibility. The segregation of the sexes within the same discipline would be a recurring reality throughout most of the last century. Similarly, international organisations, exclusively directed by men, had the power to decide for most of the twentieth century whether to accept women into their ranks or not. The dichotomy between architecture and women sometimes appeared as if they were two incompatible or perhaps alien worlds. On other occasions, women architects would participate in all female congresses, like the dibujantas exhibition. Was this to protect themselves? To achieve greater visibility? Or simply because their male colleagues continued to reject their integration?

The latter seems most likely, as confirmed by the derisive comments of Juan Valera, politician and diplomat, to justify their opposition to allowing the entry of the writer Emilia Pardo Bazán to the

Real Academia de la Lengua (Royal Academy of Spanish Language): “If we bring women into men’s Academies, perhaps they will bind and shape their spirit to ours, erasing their originality and sterilizing them. It is therefore preferable to create women’s Academies where they invent new sciences, or, rather, they complement ours, which is no more than half of it until now” (

Virtanen 2016, p. 34).

Interestingly, Spanish higher education was never segregated by sex. While it is true that in the late 19th century, there were female students in Spanish universities, their number was really small, and it was not until 1910 when the need to be granted special permission to enrol was waived. Although there were several graduates and doctors in Medicine and Law, it was not until the proclamation of the Second Republic in 1931 that Spanish women became broadly aware of the importance of having an education and being able to practise a profession. It was in that Republican period when women started studying architecture for the first time.

In June 1936, Matilde Ucelay became the first female architect to graduate in Spain and hence opened the way for many others. She was also the first woman who practised architecture, although in extremely adverse conditions because she suffered, in addition to the difficulties of a profession historically exercised by men, professional disqualification imposed by court martial proceedings (

Vílchez 2014, p. 191). At the end of the Spanish Civil War, she was charged with “assisting a rebellion” and was sentenced to disqualification in perpetuity from public office and banned from the private practice of her profession for five years. Her first clients were foreigners, according to Ucelay, because they were used to seeing work entrusted to a woman in their countries (

Vílchez 2013, p. 176).

The second Spanish woman to finish her architectural studies was Rita Fernández Queimadelos, who received her degree in Madrid in 1941 (

López-González et al. 2017, p. 170). Only two other women studied architecture during the war, while five did so in the next two decades. The dominant ideology of the Franco regime forced the removal of women from studies and the labour market (

Agudo-Arroyo and Sánchez de Madariaga 2011, p. 159). In the 1960s, with the Economic and Social Development Plans, the number of female university students increased markedly, although enrolments for architecture courses remained low, with only about forty female architects graduating in Spain. Most of them dedicated themselves to teaching and working for state administrations, while others worked in ateliers, often managed by a man (usually her husband). The arrival of democracy in Spain in the late 1970s encouraged women’s access to employment and public life in the country. But it was not until 1995 that Pascuala Campos de Michelena became the first Full Professor in “Architectural Design” in a Spanish university (

Muxí 2018, p. 157). Since then, the increasing number of female students studying architecture has been constant, as well as the appearance of ateliers managed by women.

In 1936, there was a military uprising that led to a civil war in Spain. In 1939, when World War II began, the rebellion’s leader General Franco emerged victorious, embarking on a dictatorship. Once Nazism was defeated in Europe, Spanish isolation became more apparent, until in 1955, the Spanish state was accepted, for geostrategic reasons, as a full member of the UN. This meant the perpetuation of the Franco dictatorship until his death in 1975. It was in this stifling atmosphere that the first Spanish female architects built their works (

Hernández-Pezzi 2015, p. 392). Only a minority among the small number of professionals decided to cross the Spanish border and experience the different ideas that were being debated in democratic countries like Germany and the USA, or in dictatorships like Iran. There, they were able to witness that gender was not a primary issue for politicians or technicians.

We therefore propose an innovative exploration into how the international congress helped Spanish female architects—conditioned by the political system—to break down professional and geographic boundaries, despite the fact that all women suffered severe discrimination and were also fighting to establish their own place within the profession.

2. Women’s Opinions

In 1963, the architect Elena Arregui Cruz-López was sent by the Permanent Exhibition of Construction (EXCO) as the Spanish delegate to the First Women’s International Congress held in the German city of Bad Godesberg, close to Bonn, then capital of West Germany. The congress, whose main theme was the woman’s viewpoint on housing and town planning, was not organised, in the words of Arregui, “by any feminist club”, but by Federal West Germany’s Ministry of Construction. The purpose of the conference was to listen to the woman, to the mother, and specifically, to the person who spent the majority of their time in the home during that period.

However, during the sessions, doubts began to surface in the delegates’ minds about whether a woman was qualified to give opinions on these questions. The congress’s response, recorded by Arregui herself in a subsequent article (

Figure 1), was that: “They were not prepared to give an opinion on these questions, but they were prepared to prepare themselves and, which is of greater importance, were eager to do so” (

Arregui 1963, p. 32).

It was expected that the criticism and complaints of the women would capture all the headlines. Elena Arregui had the task of putting a list of demands together to be directed to the planners that were tasked with building the living spaces. However, it ended with the delegates contemplating a request for dialogue and training, in addition to a list of aspirations issued by the women congress delegates, which can be summarised broadly into four points:

Single family housing. The congress decided that there was a real necessity to design houses for families with children with their own garden. In justification, they elaborated a variety of arguments, even, that the individual house represented an element to combat communism, as a symbol of the bourgeoisie and of family well-being in contrast to the monolithic housing blocks behind the iron curtain.

Larger houses. So that the young lady and the mistress of the house could get dressed and admire themselves in a full length mirror. So the father could escape and relax after returning from a tiring day’s work. They also demanded bigger kitchens where they could eat, and a lavatory and washbasin, along with a bathroom. Lastly, the women dreamt of certain improvements such as a dividable living room, a space between it and the bedrooms, in addition to enough underground garages to not have to suffer the vexing lines of cars in front of their houses.

Town planning. From the mother’s point of view, they demanded children’s playgrounds, with paths leading directly to schools and solutions to pedestrian crossings.

Other problems. They also addressed accommodation for the elderly and its integration into community life, and dwellings for single occupiers and buildings in rural areas.

In general, the women lamented their inability to criticise housing developments when they were still at the planning stage and only having the possibility when it was too late. They also demanded that more consideration be given to their opinions, which were mainly ignored, meaning that their experience was often inconsequential and their wishes overlooked (

Arregui 1963, p. 35).

Given that these problems appeared to be similar across Europe, it was proposed to conclude the congress with the creation of a permanent committee that would bring together European women who were interested in the housing question, and that the press, radio and television should broadcast their concerns. Furthermore, they proposed that female technicians must consult any blueprints when certain bodies apply for planning approval for residential and urban developments. This last point is especially relevant, and not without reason, because by having qualified professionals—architects and engineers—or female consultants at the forefront of new urban developments, women might be able to feel at least minimally represented. They trusted that their requirements would immediately be incorporated in the new field of town planning, bringing their aspirations to fruition.

By acting as a conduit between women’s grievances as a group and the profession’s practices, the architects became the spokeswomen for the demands formulated in the congress. The attendees, judging by the four points of the resolution, appeared to be most interested in finding valid representatives before the decision-making bodies and organising themselves into associations.

Echoes of women’s progressive organisation began to arrive in Spain in the 1960s. Carmen Castro, a doctor of philosophy and literature—who had lived in Paris, Rome, Berlin and Princeton—wrote an article in the journal

Arquitectura, injecting a spirit of optimism and encouragement for women architects and women in general:

Among architects—in Spain and outside of Spain—there are many good architects who are women, excellent, wise and admirable. And therefore both women and men—professionally—place careful attention and grant a preferential position to the woman as an indispensable part for the construction, and the most perfect realization of their projects.

Carmen Castro continued her article, with a strongly argued case for high-rise buildings, considering that they were the typology best suited to women. The dense and compact city, with street level shops and teeming sidewalks, like New York or Chicago, was the prototype for the new urban and cosmopolitan woman. This was the dream-city for Castro and many other women, in contrast to the isolated house with its garden, where they would have to spend 80% of their time trapped at home, because, for one thing, they had no other spaces for recreation. Nonetheless, this city needed not be incompatible with the demands for parks, footpaths to school and underground parking, nor with the requirement agreed in the 1963 women’s congress to find female representatives for the decision-making bodies, and organising themselves into associations.

In 1970, another international congress was organised in Bad Godesburg, under the slogan “Städtebau und die Belange der Frau” (Urbanism and the interests of women). Attending were such figures as the doctor Camila Odhnoff, Swedish minister of Family and Social Affairs, and a representative from the Moscow Institute of Town Planning, Jelena Borissowna Sokolowa, who extolled the uniqueness of the role of women in the Soviet Union (

Winter-Efinger 1970, p. 29).

The coordinator of the event was Dr. Eng. Isolde Winter-Efinger, who worked for the German Ministry of Housing (

Figure 2). She had met the Spanish architects Rodolfo García-Pablos and Carlos de Migue, during an official visit they had made to Germany in 1965. As a result of the good relations they had formed and both countries’ interest in exchanging experiences, Winter-Efinger had been invited to give a talk in Spain about women’s activities in the field of housing design (

Blanco-Agüeira 2010, p. 128;

Hervás 2017, p. 49). There is no confirmation as yet that the said conference on women actually took place in Spain, but we do know that no Spanish male or female architects were among the speakers at the 1970 congress, although a summary of the presentations was translated into Spanish.

3. Women and Architecture

There were few female Spanish architects practising during the dictatorship, but at least we can attest that some were fully informed about what was happening outside Spain’s borders. During the transition (a period of modern Spanish history that started in 1975, the year of Franco’s death, and ended in 1982), and even immediately prior, we know first-hand about the experiences of María Teresa Muñoz Jiménez and Anna Bofill Levi. In this extremely complex political moment (

Pérez-Moreno 2016, p. 113), Spanish female architects attending international conferences outside the Spanish borders experienced forums of debate and conflict, where their role as professionals was openly discussed.

María Teresa Muñoz took part in the “Women in Agriculture Symposium”, organised in 1974 by Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. For three days from 29 to 31 March, they explored the multiple concerns of professional women in America. The participants were mainly women, although some men attended. They discussed conflicts of roles, feminist issues around design and also the image and perception of female students in a predominantly male world. At this ambitious symposium, Muñoz, who qualified in 1972, was able to attend a presentation given by Gertrude Kerbis, in which she talked about her concepts of design morphology illustrated by her own work in a professional career that included collaborations with the firm S.O.M. In addition to town planners, the event was also remarkable for the attendance of psychologists, psychiatrists and a sociologist, Whitney Gordon, who introduced questions such as how to establish a healthy work–life balance, and the role of mothers in the fields of law, medicine and architecture (

Standley et al. 1974). Regi Goldberg, the New York architect, founder of the Alliance of Women in Architecture, explained the symbolism of architecture, while Marjorie Hogg focused on discrimination in education and the profession. Therefore,

arquitectas became aware of those groups which women architects formed in the 1970s in the United States to push for greater professional equality (

Stratigakos 2016, p. 17).

More than four decades after the event, Muñoz still recalls the impact that her attendance at the congress made on her. Travelling from Toronto, where she was studying for a Masters in architecture and passing through Chicago (

Figure 3), she travelled with a group of colleagues and a professor, to experience a culture clash:

I saw all these powerful and wise women. Women architects who were making calculations relating to really complex structures and who explained everything to us on questions concerning town planning. My impression is that they were very radical, especially those coming from Columbia University. They gave importance to sociological implications in architecture and the message they transmitted was that women should get more involved in the discipline.

1

Several of the participants in St. Louis, such as Regie Goldberg and Whitney Gordon, had previously taken part in other international congresses specifically dedicated to women architects. Thus, a series of intersections and connections were established between careers and shared personal situations that fostered a bonding process among colleagues from different parts of the world. Names such as Alison Smithson or Denise Scott Brown were a reference for Spanish architects that graduated during the transition. Other names emerged after participation in congresses with women’s themes, during the transition period to democracy. One such figure was the Catalan architect Anna Bofill, who a year after qualifying attended the 1972 International Congress on Design and Architecture (IDCA), held in Aspen, Colorado. In this location, deep in the Rocky Mountains, a close collaboration among modern art, design and architecture had been promoted for decades (

Banham 1974).

Anna Bofill presented a talk on the projects of the

Taller de Arquitectura, a multidisciplinary team founded the previous decade in Barcelona and of which Bofill was a member (

Bofill 1975). Her sojourn in Aspen allowed her to meet other architects and artists, including the painter Robert Rauschenberg who, during the congress, created an open-air sculpture made from recycled materials with the assistance of students and volunteers.

I formed a friendship with Gae Aulenti, with whom I made a journey after the congress to Phoenix, Arizona, to visit Taliesin West, the studio of Frank Lloyd Wright, presided over at the time by his widow and leading designers. There we hired a car to roam around the deserts and the Mesa Verde national park, before arriving at San Francisco.

Anna Bofill again encountered the Italian architect and designer in the UIFA (

Union Internationale des Femmes Architectes) congress, held in Ramsar, Iran in 1976. She also made contact there with Marie Christine Gagneux and various Iranian architects, including Nasrine Faghih, a project planner who eventually established herself in Europe after the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Also attending the conference were Jane Drew, Alison Smithson and Denise Scott-Brown, all unaccompanied by their well-known partners: “Generally, no one declared themselves to be overtly feminist. I noted that only a few complained about their position in the team or about a male colleague with whom they collaborated. It was more a complaint than a demand. There was no feminist consciousness”.

2Anna Bofill’s invitation to attend the congress came directly from Solange D’Herbez de la Tour, an architect of Romanian origin who had founded the Union Internationale des Femmes Architectes (UIFA) in Paris in 1963, as the Union Internationale des Architectes (UIA) had vetoed the entry of women into its ranks. With the objective of organising an international network of professional women and promoting their work, the association arranged a series of congresses.

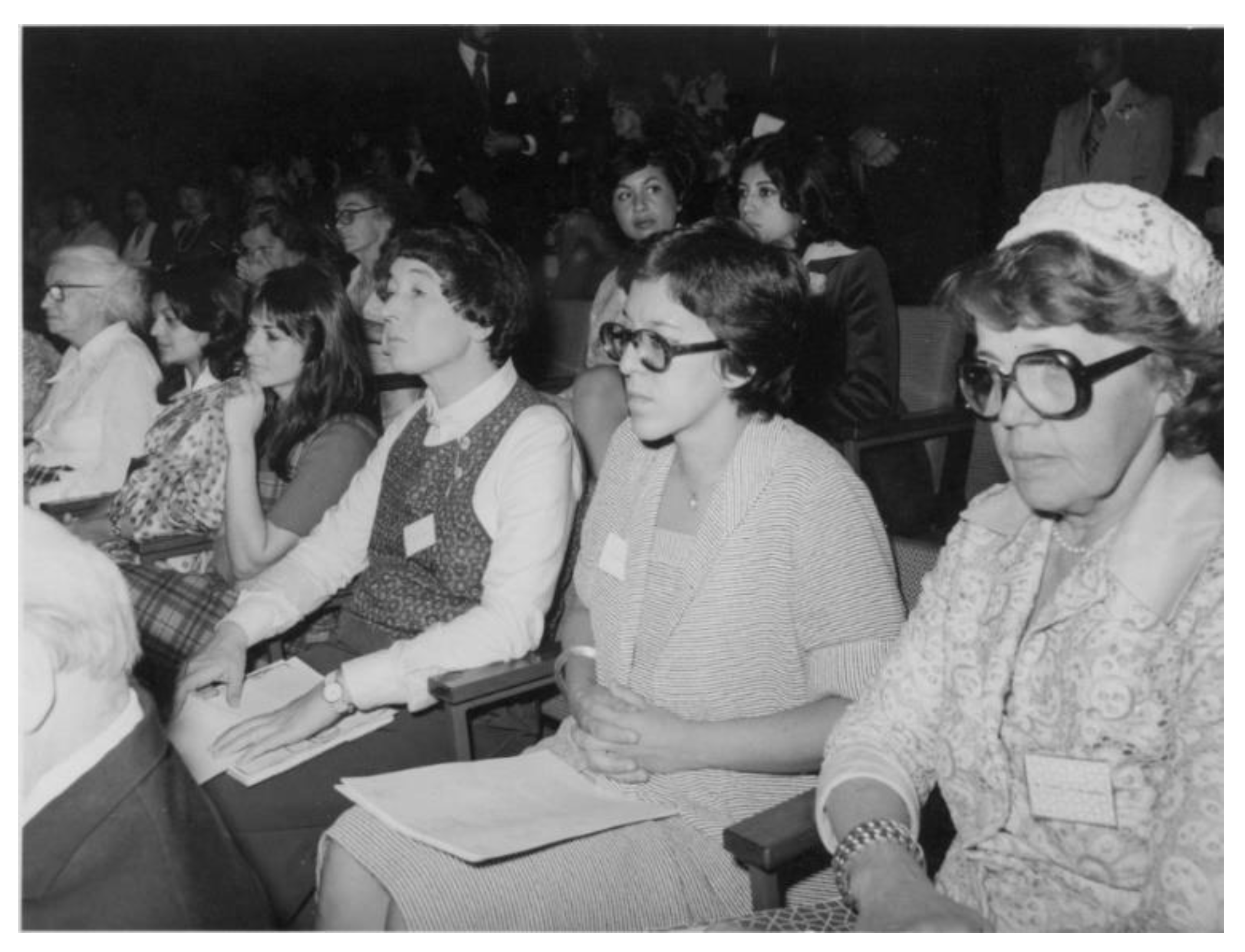

The first UIFA congress took place in Paris in 1963. Women from twenty countries attended, but not one of them came from Spain. The second congress was held in Monaco in 1969, and the third in Bucharest in 1972. For the fourth congress, in 1976, the chosen destination was Ramsar, Iran, under the title “The Crisis of Identity in Architecture”. The event was notable for the presence of the Iranian empress and architect Farah Diba, who as part of her institutional role attended the sessions and toured the exhibition of the attendee’s projects. In addition to the Spanish representation, architects from France, Italy, the United Kingdom, the United States, India, Turkey, Nigeria, Denmark, Czechoslovakia and Finland attended (

Drew et al. 1976). Bofill presented a talk titled

Design as Response to People’s Dreams (

Figure 4). This contribution was neither published nor subsequently reviewed, but its author considered that “it gave a significant stimulus to recognition of my work within the team with whom I was working at that moment. It was an empowering boost to our self-esteem that many needed at that time. It was also gratifying to meet other architects from around the world and learn of the existence of such excellent women professionals”.

3 She had been particularly impressed by presentations given by Alison Smithson and Denise Scott Brown, and also the exhibition of the American Anne Tying, a partner of Louis I Kahn, which had explored “aspects of geometry and mathematics that she was researching in the studio and were the basis of projects attributed to Kahn, but evidently were authored by both”.

4With Spain’s 1985 entry into the European Economic Community, new possibilities suddenly opened to architects that travelled beyond its borders. The European Union, at least superficially, was interested in the roles of Spanish professionals, brandishing its support and assistance, when Spain entered as a fully entitled member. Under the “operation Bienvenida”, the architect Amparo Berlinches Acín, winner of the 1981 National Architecture Award of Spain in the speciality of restoration, received a letter of greeting from the European commissioner Carlo Ripa di Meana. In his letter, the Italian politician, who formed part of the European Commission led by Jacques Delors, invited her to form part of an initiative that in 1986 aiming to intensify relations between female professionals throughout Europe. The programme brought together Spanish and Portuguese women with Irish and Italian women, to foster an exchange of common experiences within the European Union (

Figure 5). Joining the Madrid architect in receiving letters were jurists, journalists and company directors. Apart from building friendly relations, these initiatives were able to bring positive results by means of joint actions.

4. Results

After the first advance parties, during the dictatorship, Spanish architects who decided to venture beyond the country’s borders encountered debates and demands that were entirely unfamiliar. While in the Bad Godesberg congress of 1963, female technicians were proposed to act as mediators on behalf of other women for the scale models, numbers and arguments expressed by their male colleagues, the Union Internationale des Femmes Architectes decided the same year to reproduce the format of the congresses to which their attendance was barred.

It is important to highlight how in the first international congress held in Germany, the terms “urbanism” and “woman” were exclusive; they were two spheres that coexisted, without interacting with each other. It was evident that women were not prepared to comment on this issue. In addition, the dichotomy of roles was reinforced: Point two stated that the father should have a space to rest after work and the mother needed a mirror for grooming. It was even intended to fight communism, colonising the land with the mass construction of single-family homes with private gardens, managed by housewives. However, women attendees admitted not being versed in specific concepts of urban planning but claimed they needed to train, to associate and to find in European female architects a greater empathy to formulate their needs, which were common throughout Europe.

During the transition to democracy, the female Spanish architects who attended international conferences were able to create an international network of contacts that allowed them to exchange ideas and knowledge. They recounted information and met figures they admired, and also excellent professionals who were hitherto unknown. By the 1960s, they were all reflecting upon equal rights for women in the profession and the impact they had in specific fields of architecture and town planning, traditionally relating to male roles. Although these experiences and events were not always recorded, there is no doubt they provided a significant stimulus in their work. In the congress held in the United States, the burgeoning demands of professional women and their achievements up to that moment could be felt, exposing examples and models that served as a reference to all participants.

Finally, the incorporation of Spain into the European Economic Community in 1985, now the European Union, opened paths to new opportunities for women. Albeit timidly, the European Commission did offer to assist them within the new legal framework that enabled them to improve their situation. Thus, it was abroad, where they had previously gone to advance their careers, which came to nurture and protect them.