De Modo Qualiter Reges Aragonum Coronabuntur. Visual, Material and Textual Evidence during the Middle Ages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Precedents: Dynastic Succession in Aragon through Primogeniture. Notes on the First Kingdom of Pamplona

3. Peter II (1196–1213): His Coronation in Rome and the Immediate Consequences

4. James I (1213–1276): The Renunciation of His Coronation and the Proclamation of the Right to Conquest

5. From Peter III (1276–1285) to James II (1291–1327): The Development of the Ceremonial in Favour of Royal Sovereignty

6. Alfonso IV (1327–1336) and Peter IV (1336–1387): The Culmination of the Process of Consecrating the King and Everything around Him

7. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aurell, Jaume, and Marta Serrano-Coll. 2014. The Self-coronation of Peter the Ceremonious (1336): Historical, Liturgical and Iconographical Representations. Speculum. A Journal of Medieval Studies 89: 66–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros Beretta, Antonio. 1963. Alfonso X el Sabio. Barcelona: Salvat. [Google Scholar]

- Blancas, Jerónimo. 1641. Coronaciones de los Serenissimos Reyes de Aragón. Zaragoza: Diego Dolmer. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, Marc. 1961. Les Rois Thaumaturges. Étude sur le Caractère Surnaturel Attribué a la Puissance Royale Particulièrement en France et en Angleterre. Paris: Armand Colin. [Google Scholar]

- Bouman, Cornelius A. 1957. Sacring and Crowning. The Development of the Latin Ritual for the Anointing of Kings and the Coronation of an Emperor before the Eleventh Century. Groningen-Djakarta: J.B. Wolters. [Google Scholar]

- Buc, Philippe. 2001. The Dangers of Ritual. Between Early Medieval Text and Social Scientific Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carlyle, Robert Warrand, and Alexander James Caryle. 1967. Il Pensiero Politico Medieval. Bari: Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Carrero Santamaría, Eduardo. 2012. «Por las Huelgas los juglares». Alfonso XI de Compostela a Burgos, siguiendo el libro de la coronación de los reyes de Castilla. Medievalia 15: 143–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Catalán, Diego. 1946. Crónica de Alfonso XI. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Conde, Rafael. 1992. Sello de plomo de Jaime I. In Cataluña medieval. Barcelona: Lunwerg. [Google Scholar]

- De Azara, José Jordán Urries. 1913. Las Ordenaciones de la Corte aragonesa en los siglos XIII y XIV. Boletín de la Real Academia de las Buenas Letras 7: 220–29. [Google Scholar]

- De Bofarull, Antonio. 1850. Crònica de D. Pedro IV, el Ceremonioso ó del Punyalet. Escrita en Lemosin por el Mismo Monarca, Traducida al Castellano y Anotada. Barcelona: Imprenta de Alberto Frexas. [Google Scholar]

- De Bofarull, Antonio. 1860. Crónica Catalana de Ramón Muntaner: Texto Original y Traducción Castellana, Acompañada de Numerosas Notas. Barcelona: Diputación Provincial de Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- De Dainville, Maurice Oudot. 1952. Sceaux conserves dans les Archives de la ville de Montpellier. Montpellier: Lafitte-Lauriol. [Google Scholar]

- De Molina, Rafael Conde y Delgado. 1998. Las insignias de coronación de Pedro I-II “El Católico”, depositadas en el Monasterio de Sijena. Anuario de Estudios Medievales 28: 147–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sagarra i Siscar, Ferran. 1916–1932. Sigil·Lografia Catalana. Inventari, Descripció i Estudi dels Segells de Catalunya. Barcelona: Estampa d’Henrich. [Google Scholar]

- Durán Gudiol, Antonio. 1978. Ramiro I de Aragón. Zaragoza: Guara. [Google Scholar]

- Durán Gudiol, Antonio. 1989. El rito de la coronación del rey en Aragón. Argensola: Revista de Ciencias Sociales del Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses 103: 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Eubel, Conrad. 1913. Hierarchia Catholica Medii Aevi, I. Munster: Sumptibus et typis Librariae regensbergianae. [Google Scholar]

- Ferotín, Marius. 1904. Le “Liber Ordinum” en usage dans l’Eglise wisitothique et mozarabe d’Espagne du cinquième au oncième siècle. Monumenta Ecclesiae Liturgica 5. [Google Scholar]

- Ferran, Soldevila. 2007a. Bernat Desclot, Crònica. In Les Quatre Grans Cròniques. Revisió Filològica de Jordi Bruguera i Revisió Històrica de M. Teresa Ferrer i Mallol. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans. [Google Scholar]

- Ferran, Soldevila. 2007b. Jaime I, Libre dels feyts del rei en Jacme. In Les Quatre Grans Cròniques. Revisió Filològica de Jordi Bruguera i Revisió Històrica de M. Teresa Ferrer i Mallol. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans. [Google Scholar]

- Giesey, Ralph E. 1968. If Not, Not. The Oath of the Aragonese and the Legendary Laws of Sobrarbe. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Helmholz, Richard H. 2010. The Spirit of Classical Canon Law. Athens: Georgia. [Google Scholar]

- Jacq, Christian, and Patrice de la Perriere. 1981. Les Origines Sacrées de la Royauté Française. Paris: Léopard d’Or. [Google Scholar]

- Kehr, Paul. 1946. El papado y los reinos de Navarra y Aragón hasta mediados del siglo XII. Estudios de Edad Media de la Corona de Aragón II: 74–186. [Google Scholar]

- Lacarra y de Miguel, José María. 1972. El juramento de los reyes de Navarra (1234–1329). Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia. [Google Scholar]

- Le Goff, Jacques. 2001. La structure et le contenu idéologique de la cérémonie du sacre. In Le Sacre Royal à L’époque de Saint Louis. Edited by Jacques Le Goff, Éric Palazzo, Jean-Claude Bonne and Marie-Noël Colette. Le Temps des Images. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Mansilla, Demetrio. 1955. La documentación pontificia hasta Inocencio III. Monumenta Hispaniae Vaticana 1: 1–665. [Google Scholar]

- Mateu y Llopis, Felipe. 1954. Rex Aragonum. Notas sobre la intitulación real diplomática en la Corona de Aragón. Spanische Forschungen der Görresgesellschaft. Herausgegeben von ihrem spanischen Kuratorium. Heindrich Finke (+), Wilhelm Neuss, Georg Schreiber. Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Kulturgeschichte Spaniens 9: 117–43. [Google Scholar]

- Molina i Figueras, Joan. 1997. La ilustración de leyendas autóctonas: El santo y el territorio. Analecta Sacra Tarraconensia 70: 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto Soria, José Manuel, ed. 1993. Legitimación y propaganda como criterios de valoración de una tipología ceremonial. In Ceremonias de la Realeza. Propaganda y Legitimación en la Catilla Trastámara. Madrid: Nerea. [Google Scholar]

- Niña Jové, Meritxell. 2014. L’escultura del Segle XIII de la Seu Vella de Lleida. Lleida: Universitat de Lleida. [Google Scholar]

- Orcástegui Gros, Carmen. 1986. Crónica de San Juan de la Peña (Versión Aragonesa). Edición Crítica. Zaragoza: Diputación Provincial, Institución Fernando el Católico. [Google Scholar]

- Orcástegui Gros, Carmen. 1995. La coronación de los reyes de Aragón: Evolución política-ideológica y ritual. In Homenaje a Don Antonio Durán Gudiol. Huesca: Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses. [Google Scholar]

- Orcástegui Gros, Carmen, and Esteban Sarasa Sánchez. 2001. Sancho Garcés III el Mayor. Rey de Navarra. Burgos: La Olmeda. [Google Scholar]

- Pacaut, Marcel. 1957. La Théocratie. L’Eglise et le Pouvoir au Moyen Age. Paris: Montaigne. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios Martín, Bonifacio. 1969. La bula de Inocencio III y la coronación de los reyes de Aragón. Hispania. Revista Española de Historia 113: 485–504. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios Martín, Bonifacio. 1975. La Coronación de los Reyes de Aragón. 1204–1410. Aportación al Estudio de las Estructuras Políticas Medievales. Valencia: Anubar. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios Martín, Bonifacio. 1976. Los símbolos de la soberanía en la Edad Media española. El simbolismo de la espada. In VII Centenario del Infante D. Fernando de la Cerda. Ciudad Real: Instituto de Estudios Manchegos. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios Martín, Bonifacio. 1986. Los actos de coronación y el proceso de secularización de la monarquía catalano-aragonesa (s. XII–XIV). Bibliothèque de la Casa de Velazquez. 1. État et Église Dans la Gènese de L’état Modern 1: 115. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios Martín, Bonifacio. 1988. Investidura de armas de los reyes españoles en los siglos XII y XIII. Gladius vol. esp.: 153–92. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios Martín, Bonifacio. 1994a. El “Manuscrito de San Miguel de los Reyes” de las “Ordinacions” de Pedro IV. Coordinated with Bonifacio Palacios Martín. Valencia: Scriptorium. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios Martín, Bonifacio. 1994b. Estudio histórico de las Ordenaciones. In El “Manuscrito de San Miguel de los Reyes” de las “Ordinacions” de Pedro IV. Coordinated with Bonifacio Palacios Martín. Valencia: Scriptorium. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Monzón, Olga. 2010. Ceremonias regias en la Castilla Medieval. A propósito del llamado Libro de la Coronación de los Reyes de Castilla y Aragón. Archivo Español de Arte 83: 317–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ramos Loscertales, José María. 1961. El Reino de Aragón Bajo la Dinastía Pamplonesa. Salamanca: Universidad de Salamanca. [Google Scholar]

- Righeti, Mario. 1956. Historia de la Liturgia. Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, Teófilo. 2012. A King Travels: Festive Traditions in Late Medieval and Early Modern Spain. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- San Vicente Pino, Angel. 1992. Ceremonial de Consagración y Coronación de los Reyes de Aragón. Ms. R. 14.425 de la Biblioteca de la Fundación Lázaro Galdiano, en Madrid. Coordinated with Eduardo Vicente de Vera. Transcripción y estudios. Zaragoza: Diputación General de Aragón. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Albornoz, Claudio. 1962. La “Ordinatio principis” en la España goda y postvisigoda. Cuadernos de Historia de España 35–36: 5–36. [Google Scholar]

- Schramm, Percy Ernst. 1960. Las Insignias de la Realeza en la Edad Media Española. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Políticos. [Google Scholar]

- Serra Desfilis, Amadeo. 2002. Ab recont de grans gestes. Sobre les imatges de la història i de la llegenda en la pintura gòtica de la Corona d’Aragó. Afers. Fulls de Recerca i Pensament 17: 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Coll, Marta. 2008a. El códice AGN-B2 y la iconografía de coronaciones y exequias en el arte bajomedieval. In Ceremonial de la Coronación, Unción y Exequias de los Reyes de Inglaterra. Estudios Complementarios al Facsímil. Coordinated with Eloísa Ramírez. Pamplona: Gobierno de Navarra. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Coll, Marta. 2008b. Jaime I el Conquistador. Imágenes Medievales de un Reinado. Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Coll, Marta. 2011. La iconografia de Jaume I durant l’edat mitjana. In Jaume I, Commemoració del VIII Centenari del Naixement de Jaume I. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Coll, Marta. 2012. Art as Means of Legitimization in the Kingdom of Aragon. Coronation Problems and their Artistic Echos during the Reigns of James I and Peter IV. Ikon. Journal of Iconographic Studies 5: 161–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Coll, Marta. 2015. Effigies Regis Aragonum. La Imagen Figurativa del Rey de Aragón en la Edad Media. Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Coll, Marta. 2017. Rex et Sacerdos. A veiled ideal of kingship? Representing priestly kings in Medieval Iberia. In Political Theology in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Discourses, Rites and Representations. Edited by Montserrat Herrero, Jaume Aurell and Angela C. Micheli. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Sesma Muñoz, Ángel. 1988. El sentimiento nacionalista en la Corona de Aragón y el nacimiento de la España Moderna. In Realidad e Imágenes del Poder. España a Fines de la Edad Media. Coordinated with Adeline Rucquoi. Valladolid: Ámbito. [Google Scholar]

- Silleras-Fernández, Nuria. 2015. Creada a su imagen y semejanza: la coronación de la reina de Aragón según las ordenaciones de Pedro el Ceremonioso. Lusitania Sacra 31: 107–28. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Damian J. 2016. Inocencio III, Pedro Beneventano y la Historia de España. Vergentis 2: 85–79. [Google Scholar]

- Soldevila, Ferran. 1926. La figura de Pere el Catòlic en les cròniques catalanes. Revista de Catalunya 4: 497ff. [Google Scholar]

- Soldevila, Ferran. 1934. Historia de Catalunya. Barcelona: Alpha. [Google Scholar]

- Soldevila, Ferran. 1968. Els primers anys de Jaume I. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal Mayor. 1989. Vidal Mayor. Versión Romanceada en Aragonés del Códice “In Excelsis Dei Thesauris”. Siglo XIII. Edición Facsímil Autorizada por el J. P. Getty Museum de Santa Mónica, California. Huesca: Diputación Provincial de Huesca and Instituto de Estudios Aragoneses. [Google Scholar]

- Yarza Luaces, Joaquín. 1995. La pintura española medieval. El mundo gótico. In La Pintura en Europa. La Pintura Española. Directed by Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez. Milán: Electa. [Google Scholar]

- Zurita, Jerónimo. 1980. Anales de Aragón. Edited by Ángel Canellas López. Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico. book II. First published 1512–1580. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | 1 Samuel 10. However, there is an even earlier reference in 9,16: “About this time tomorrow I will send you a man from the land of Benjamin. Anoint him ruler over my people Israel”. |

| 4 | Panoramic view of the ceremonies of the coronation, the unction and the funeral rites of the kings of England, for example, in (Serrano-Coll 2008a, pp. 145–74). |

| 5 | The first, defended by certain anthropologists, in particular Fortes and Geertz, focuses on the taking of power through this ceremony, whereas the second, put forward by Van Gennep, emphasises the fact that in the course of the ceremony the king moves from one state to another completely new. This would be a ceremony of transit. Palacios synthesises this thesis by stating that these acts are a translatio of royal dignity to the person of the king (Palacios Martín 1986). For more on this question, see also (Le Goff 2001, p. 19ff). |

| 6 | Due to lack of space, this article will not discuss the coronation of queens, despite the fact that they were entitled to similar solemnities as the king, given that a queen was not only the king’s wife, but also the mother, or should be, of the future king. In addition, a queen’s anointment meant that like her husband she was a sovereign individual embodying the sacredness of the monarchy; however, she acceded to the crown through her spouse, so she remained subordinate to the king. See (Bouman 1957, p. 151). In the Crown of Aragon the principle of the queen’s subordination to the king is manifested textually because, among other elements of a legal nature, the queen’s ceremony followed that of her husband’s investiture. It can also be observed figuratively, as will be seen. See (Silleras-Fernández 2015). |

| 7 | |

| 8 | Quia enim—post unctionem quam cum coeteris fidelibus. Meruistis hoc consequi quod beatus Apostulus Petrus dicit: vos genus electus, regale sacerdotium—episcopale et spirituali unctione et benedictione regiam dignitatem potius quam terrena potestate consecuti estis. P. L. 125. Col. 1040. From (Bloch 1961, p. 71). |

| 9 | “El poder ha sido dado de lo alto a mis señores […] para que el reino terrestre esté al servicio del reino de los cielos” (Power has been given from on high my lords […] so that the kingdom of the earth may serve the kingdom of heaven). Gregorii Papae I Registrum Epistolarum, III, 61. Quoted in (Pacaut 1957, p. 230). |

| 10 | See (Palacios Martín 1975). |

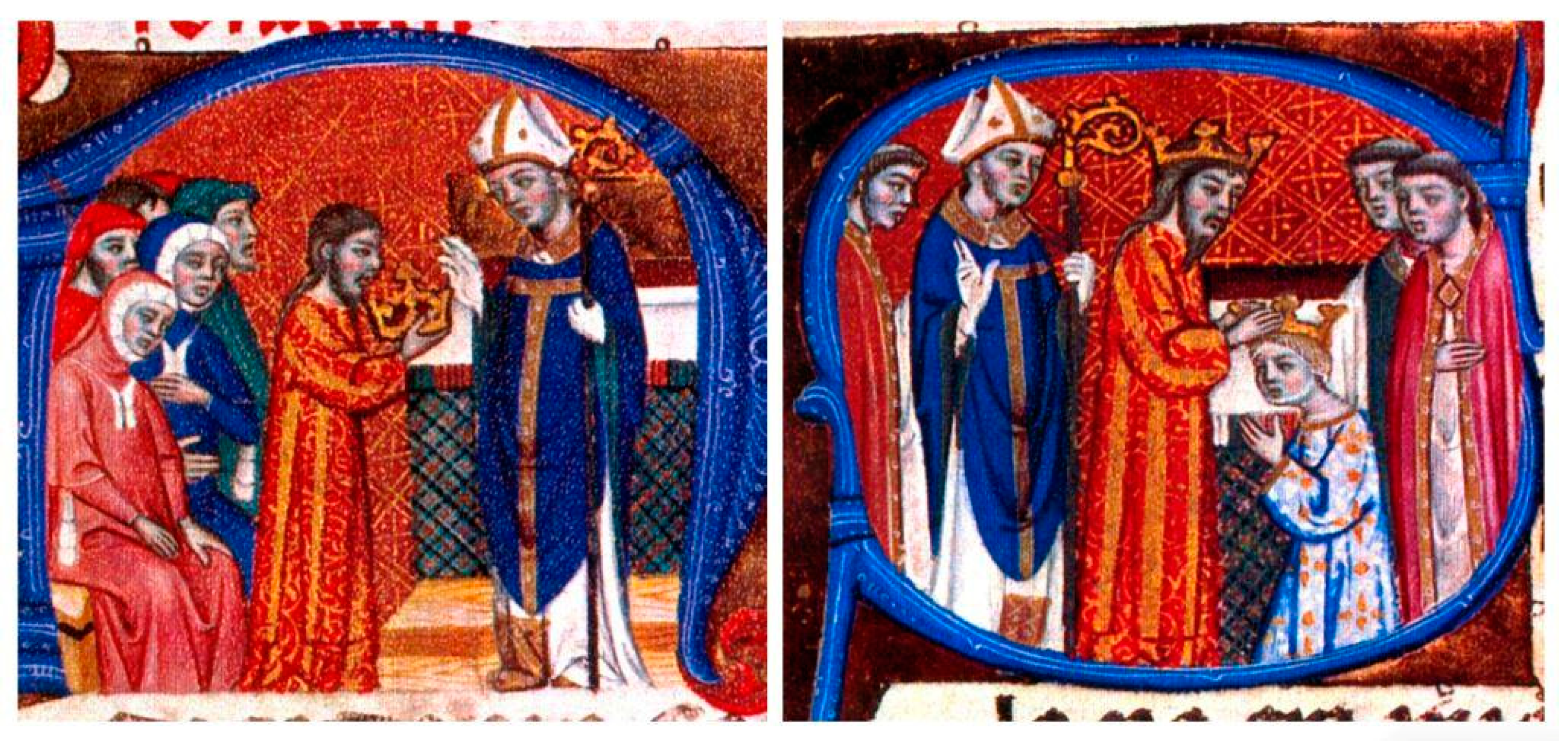

| 11 | Coronations as part of the royal ceremonies surrounding monarchical power are studied in (Ruiz 2012; Buc 2001). For a study focusing primarily on the Crown of Aragon, see (Orcástegui Gros 1995, pp. 633–47). |

| 12 | (Ramos Loscertales 1961). Referenced in (Orcástegui Gros and Sánchez 2001, p. 85). |

| 13 | |

| 14 | Ibid., p. 35. |

| 15 | “Mientras los hijos de los reyes son niños o mancebos, no son llamados reyes, sino infantes, principalmente en España, donde el hijo del rey no alcanza esta categoría si le falta el reino, no pudiendo ser rey cumplidamente; ostentará aquel título, cualquiera que sea su edad y mereciendo por naturaleza el reino; si no lo obtienen, los hijos de los reyes serán llamados infantes” (While the sons of kings are boys or youths they are not called kings, but rather infantes, principally in Spain, where the son of the king does not obtain the status of king if he does not have a kingdom, because he is not fully able to be king; he will bear that title, whatever his age and naturally meriting the kingdom; if they do not obtain it, the sons of the kings will be called infantes) (Vidal Mayor 1989, italics are mine). Regarding coronations in Navarre, see (Orcástegui Gros 1995, pp. 637–39). |

| 16 | |

| 17 | “Pareció al rey don Pedro que convenía a la dignidad de su estado coronarse con la solemnidad y fiesta que se requiere a príncipe que tiene poder que representa supremo señorío” (it seemed to King Peter that it befitted the dignity of his status to be crowned with the solemnity and celebration that is required by a prince who has power that represents supreme dominion) (Zurita [1512–1580] 1980, book II, p. 51). In the same vein Blancas also states that “convenia a la dignidad de su estado coronarse en solemnidad y fiesta” (it befitted the dignity of his status to be crowned with the solemnity and celebration) (Blancas 1641, book I, p. 3). |

| 18 | |

| 19 | (Righeti 1956, p. 1041). See also (Palacios Martín 1975, pp. 23–25). |

| 20 | Reg. Vat. 5, fol. 202r–202v. Although it has been published on various occasions, for example in (Blancas 1641, book I, pp. 5–6), in the present study we have used the transcription given in (Palacios Martín 1975, ap. doc. II, pp. 299–301), which was in turn taken from (Mansilla 1955, p. 341). |

| 21 | The document indicates that predictum regem permanum Petri Portuensis episcopi fecit iniungi, quem postmodum ipse manu propia coronavit, largiens ei regalia insignia universa, mantum videlicet, et colobium, ceptrum et pomum, coronam et mitram (ibid., p. 300). Paludamentum purpureum of the Byzantine emperors, the colobium or marina purpura auro decora (short cloak), the globe, the crown and the mitre are all listed by Durán Gudiol (1989, p. 18). Regarding the insignias and the difficulties in interpreting them, see (De Molina 1998, pp. 148–49). |

| 22 | This is known from a document addressed to James I, dated 1 June 1218 and issued by Ozenda, prioress of the convent. In it the abbess agrees to send the king the crown and other royal insignias belonging to James’ father for his coronation: concedimus et convenimus vobis Iacobo regi Aragonum et comiti Barchinone et domino Montispesulani, ut quacumque hora vos queritis vobis coronam et mitram et sceptrum et pomum similiter que fuerunt honorabilis patris vestri Petri regis Aragonum et comitis Barchinoneci eterna sit requies. On the back of the document it states: Carta corone domini regis. Carta coronee, mitre et ceptri domini regis Petri antiqui. References in (ibid., pp. 147–56). |

| 23 | As the Pope indicates in the document in which he allows the kings and queens of Aragon to be crowned in Zaragoza: Reg. Vat. 7, fol. 31, n. 92 and fol. 95. Published in (Blancas 1641, book I, p. 7). |

| 24 | As pointed out by Schramm (1960, p. 129). |

| 25 | |

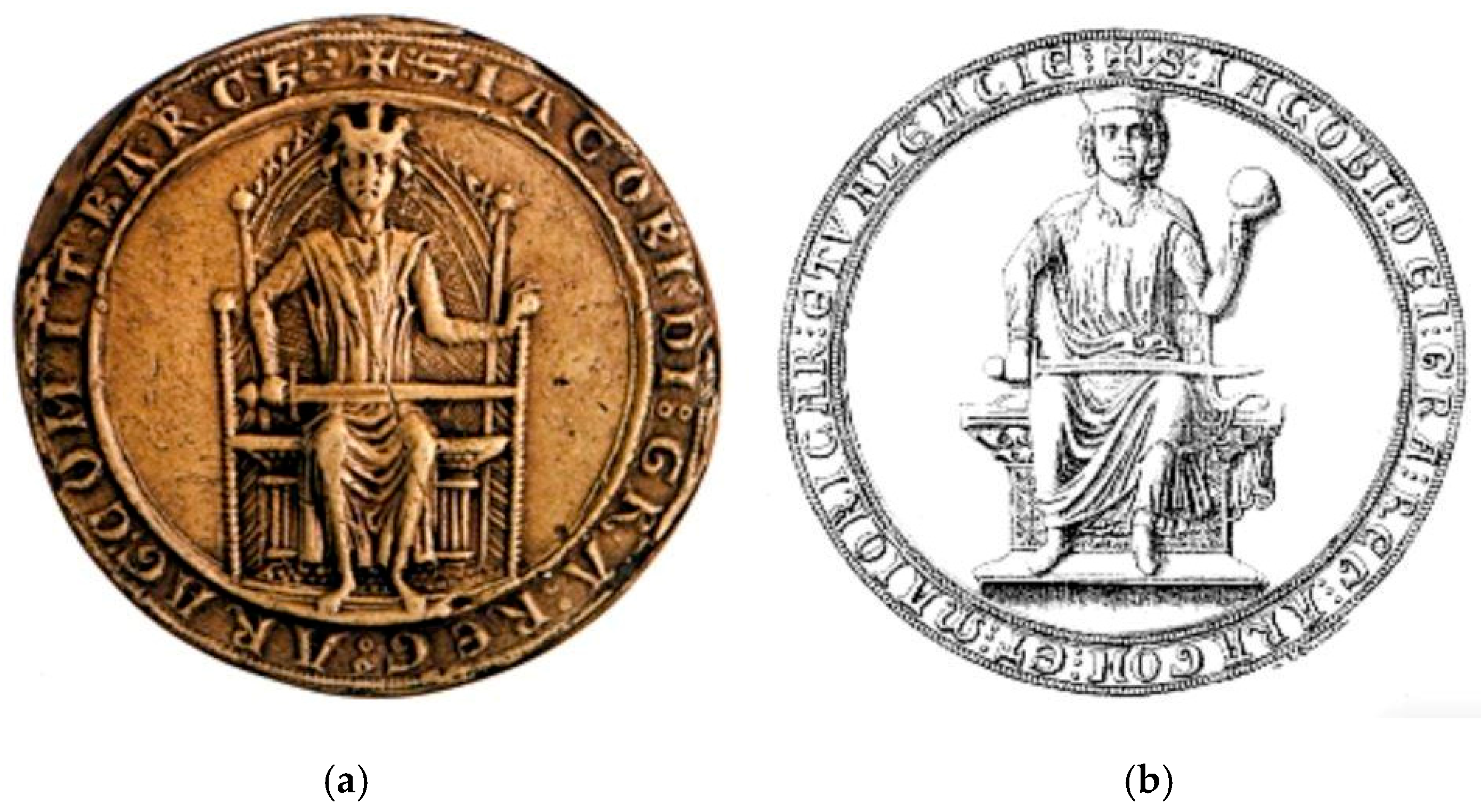

| 26 | For more on this hypothesis, see (Serrano-Coll 2015, p. 68). The king may have copied the sigillographic models of Federico II for his largest stamps. Subsequently, after adopting the imperial insignias, he transferred them to the iconography of his bulls. |

| 27 | Sancho Ramírez had already enfeoffed his kingdom to the Holy See. A letter has survived which states that the monarch informed Urban II (1088–1099) about this matter, offering him an annual tribute of 500 mancusos (mancusos Iaccensis monete) and, each of his knights, another mancuso annually. He adds that this is in perpetuity: “Haec constituo et confirmo et a me et a successor meo obseruanda perpetuo”. The document was the first to be published by Paul Ewald in 1880 according to Paul Kehr, 1928, Das Pastum un die Könogsreichen Navarra und Aragon, a work published in Berlin that was translated to Spanish (Kehr 1946). By allying himself with a distant but powerful institution such as the Papacy, Sancho Ramírez was perhaps seeking to strengthen his own position in relation to his most powerful neighbours. From then on until Peter III, there is only one clear case of a king of Aragon swearing his vassalage to the Holy See, namely Peter I, in 1098 (Mansilla 1955, pp. 58–59; Kehr 1946, pp. 184–86). |

| 28 | (Palacios Martín 1988, p. 179). See, also, (Orcástegui Gros 1995, pp. 639–40). |

| 29 | |

| 30 | Reg. Vat. 7, fol. 97, n. 100. As in (ibid., ap. doc., III, p. 302). |

| 31 | Much has been written about Peter’s motives, which bring together his interests in the south of France and the Mediterranean, with Mallorca and Sicily as strongholds. Synthesis in the early but still pre-eminent reference work by Soldevila (1934, vol. I, p. 222ff). |

| 32 | |

| 33 | See (Palacios Martín 1975, p. 27). |

| 34 | Regarding this principle, see the chapter Principles of Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction: The Protection of Miserabiles Personae and Jurisdiction ex Defectu Iustitiae in (Helmholz 2010, pp. 116–44). |

| 35 | |

| 36 | For more on this subject, see (Smith 2016). |

| 37 | That is, the best pope in the last hundred years up to the very moment in which the king wrote his chronicle (Ferran 2007b, chp. 10, p. 61). The king adds that “era bon clergue en los sabers que tanyen a apostoli de sabere, e havia sen natural, e dels sabers del món havia gran partida”; that is, “there was no better pope in the Church of Rome, because he was a good cleric, versed in matters corresponding to a pope, and he was gifted with good sense and knew much about the knowledge of the world” (ibid.). |

| 38 | Regarding this figure, who was delegated by the pope to act on behalf of James I, see (Smith 2016). |

| 39 | Ibid. |

| 40 | According to James I’s chronicle, because James was only six years old, the Bishop of Pamplona, a relative of his, held him aloft so that all could see him. And it was that that they swore loyalty to the king. “[…] on nos tenia en el braç l’arquebisbe n’Espàrrec, que era del llinatge de la Barca e era nostre parent” (where we were held in the arms of Archbishop Esparrec, who was of the lineage of Barca and was relative) (Ferran 2007b, chp. 11, p. 63). |

| 41 | The act took place “sus el palau de volta qui ara és, e llaores era de fust, a la finestra on ara és la cuina per on dóna hom a menjar a aquells qui mengen en lo palau” (in the palace that is now vaulted, but was then of wood, in the window where now is the kitchen from which food is given to those who eat at the palace) (ibid.). For more on this palace and the historiographical debates around its construction, I refer the reader to the epigraph El Castell del Rei in the doctoral thesis of Niña Jové (2014, pp. 153–59). |

| 42 | Biblioteca Nacional de Madrid, Ms. 13042, fol. 7v. Published in (Palacios Martín 1975, p. 69 and ap. doc., VI, pp. 302–3). Highly informative is another document from 1217 in which Honorius III says the following about the kingdom of Aragon: quod regnum tuum ad Romanam ecclesiam noscitur pertinere (Mansilla 1955, pp. 86–87, n. 106), quoted in (Palacios Martín 1975, p. 71, n. 29). |

| 43 | Carissimo in Christo filio, illustri regi Aragonum. Utinam prava consilia tuam adolescentiam non seducant, nec impellant ad aliquid faciendum per quod videaris ingratus et immemor beneficiorum et graciae quae apostolica sedes tibi studuit exhibere, te de illorum manibus quos inimicos reputas eruendo ac reddendo tibi terram tuam pariteer et te terrae! (Most esteemed son in Christ, the illustrious King of Aragon. I hope that bad advice does not seduce your adolescence nor impel you to do anything that makes you appear ungrateful and forgetful of the benefits and graces that the Holy See strove to give you, freeing you from the hands of those who you state are your enemies and returning your kingdom to you, and you to your kingdom!” (Soldevila 1968, pp. 143–44 and n. 22). |

| 44 | With the sole help of his mother and guardian, Lady Berenguela, who adjusted it for him. See (Palacios Martín 1988, p. 188). |

| 45 | “E fo la nostra cavalleria en Sancta Maria de l’Horta de Tarassona, que oïda la misa de Sent Espirit, nós cenyim l’espasa que prenguem de sobre l’altar” (And it was our cavalry in Santa Maria de l’Horta de Tarasson who after the mass of the Holy Spirit, put around our waist the sword which we took from the altar) (Ferran 2007b, p. 19). |

| 46 | I quote (Palacios Martín 1988, p. 160). |

| 47 | For more on the bull issued by Innocent III and its consequences for the kings of Aragon after James I, see (Palacios Martín 1969). |

| 48 | In fact, even in 1229 he sent an envoy to Rome to request that Gregory IX perform his coronation (Palacios Martín 1975, p. 78). |

| 49 | “E nós dixem-los que no érem venguts a la sua cort per metre-nos en treüt, mas per franquees que ell nos donàs; e, pus fer no ho volia, volíem-nos-en més tornar menys de corona que ab corona” (And we told him that we had not come to his court to pay him tribute, but rather for the franchises that he had given us; but he did not want to do it, so we preferred to return without the crown than with the crown) (Ferran 2007b, para. 538). |

| 50 | “E sobre açò romàs que no ens volguem coronar” (And so it came over us that we did not want to be crowned) (ibid.). |

| 51 | “Car mon llinatge la conqués ab l’espasa” (Since my predecessors conquered it with the sword) (Ferran 2007a, p. 543). |

| 52 | Although his will gave the Holy See another chance to strengthen its position. See (Palacios Martín 1975, p. 49). |

| 53 | |

| 54 | As stated in (Palacios Martín 1976, pp. 274–96). See also (Serrano-Coll 2008b, pp. 53–55). |

| 55 | These terms, however, were common in diplomatic signatures (Mateu y Llopis 1954). |

| 56 | This saint had already collaborated with a king of Aragon, Peter I (1094–1104), during the conquest of Huesca. Nevertheless, this event is described eloquently and for the first time in the Crónica de San Juan de la Peña commissioned by Peter IV between 1369 and 1372: “Vencida aquella batalla vínose San Jorge […] a la batalla de Huesca et vidieronlo visiblement” (With that battle won [of Antioch], Saint George came […] to the battle of Huesca and they saw him) (Orcástegui Gros 1986, ap. 18, lines 59–60, p. 40). |

| 57 | For more on this interpretation, see, among others, (Yarza Luaces 1995, vol. I, p. 104; Molina i Figueras 1997; Serra Desfilis 2002, p. 25). |

| 58 | The altarpiece of Saint George or the Centenar de la Ploma by Marzal de Sax, from around 1410–1420 (Victoria and Albert Museum); the altarpiece of Saint George in Jérica, from around 1423 (Museo del Ayuntamiento de Jérica, Castellón); and the predella of the altarpiece of Saint George by Nisart around 1470 (Museo Diocesano de Palma de Mallorca) are the best known examples. See the epigraph “El Conquistador amparado por la divinidad” in (Serrano-Coll 2008b, pp. 208–26). More recently, (Serrano-Coll 2011, pp. 715–37). |

| 59 | “[…] no quiso recibir la corona ni título real hasta que fuese primero coronado en Zaragoza” ([…] he did not receive either crown or royal title until he had been crowned in Zaragoza) (Zurita [1512–1580] 1980, book IV, chp. II). The coronation took place on 15 or 22 November according to (Durán Gudiol 1989, p. 25). |

| 60 | This was confirmed some time later by Peter IV when he stated that Zaragoza caput est regni Aragonum quod regnum est titulum et nomen nostrum principale: Archivo de la Seo de Zaragoza, Cartoral Grande, fol. 324v. Cited in (Palacios Martín 1975, p. 107, n. 39). |

| 61 | (Eubel 1913, p. 153), cited in (Palacios Martín 1975, p. 100, n. 19). |

| 62 | Highly significant are the terms recorded by Bonifacio Palacios: […] sed possint succesores nostri qui pro tempore fuerint, recipere unctionem, benedictionem et coronationem in quacumque civitate eis placuerit totius nostri jurisdictionis et per ministerium archiepiscopi vel episcopi notri districtus (ibid., p. 103, n. 29). |

| 63 | |

| 64 | […] quam à vobis venerabili I A. Dei gratia Oscensi Episcopo facimus, non intendimus à vobis recipere tanquam ab Ecclesia Romana, nec pro ipsa Ecclesia, nec contra Ecclesiam. Item etiam protestamur, quod ex en quia in Civitate Caesaraguste in Ecclesia Maiori Sancti Salvatoris Coronam et Militiam recipimus nullum nobis, vel successoribus nostris […] (Blancas 1641, book I, p. 22). Analysed in (Palacios Martín 1975, pp. 121–22). |

| 65 | |

| 66 | Archivo Catedral de Huesca, sign. 10, fol. 60v, according to (Lacarra y de Miguel 1972, p. 22, n. 34). It is possible that this pontifical was the one adapted for the coronation of Alfonso III, given that the following ceremony (after James II, who was not crowned) used the imperial pontifical “of Constantinople” which is kept in the Toledo codex. Palacios hypothesises that the pontifical was used by the see of Huesca, which is where the bishop who crowned the king came from. It therefore needed to be modified, which explains the notes in the margins intended to adapt it to the ceremony (Palacios Martín 1975, p. 128). Transcription of the same in (ibid., ap doc., XXI, pp. 317–21). More details on this text in (Durán Gudiol 1989, pp. 20–22). |

| 67 | Once girdled round his waist, the king of Aragon took it from its scabbard and brandished it three times, promising, respectively, to challenge the enemies of the Catholic faith, support orphans and widows and impart justice for all (De Bofarull 1860, chp. CCXCVII, p. 574). |

| 68 | The first to use it could have been Alfonso X, according to (Ballesteros Beretta 1963, p. 54). In fact, in his chronicle he mentioned that the figure of Santiago “gave him a ritual blow on the cheek” (Catalán 1946, chp. CXX, p. 1332). Brief but illustrative comments on the truth of this mechanism, in reality a transformed Virgin Mary, can be found in, among others, (Carrero Santamaría 2012). |

| 69 | And all this despite the fact that both Zurita and Blancas state that he was crowned in San Salvador de Zaragoza “in the usual manner”. The matter was contradicted and clarified in (Palacios Martín 1969, p. 496). |

| 70 | |

| 71 | |

| 72 | See (Palacios Martín 1975, p. 194). |

| 73 | (Ibid., p. 200). The king not only swore on the privileges but also became their most staunch defendant. In the same vein as Palacios are the studies of Sesma Muñoz (1988, p. 226). |

| 74 | The chronicler Muntaner attended as a representative of Valencia, with his children: “E així mateix hi fom nosaltres” (And likewise we went there) (De Bofarull 1860, chp. CCXCIV, p. 566). He also how impressive the event was in the following terms: “Què us en diría? Que jamés en Espanya no fo així gran festa en un lloc, de bona gent, com aquesta és estada” (What can I say to you? That never in Spain has there been as great celebration as this has been) (ibid.). Peter IV in the prologue to his chronicle also refers to it: “Item és feta menció del fer de la coronació del dit senyor rey N’Anfós, com fos una de les notables festes qui es feessen en la Casa d’Aragó, e non den ésser més en oblit, car solament hic es feta mencio del sit senyor rey, nostre pere, en aquests dos fets qui foren fort notables, ço es, de la conqueste de Sardenya e de la sua coronació” (To mention the coronation of King Alphonse, as one of the most notable celebrations ever to be held by the House of Aragon, and will never be forgotten, since our King Peter mentions two notable feats, that is, the conquest of Sardinia and his coronation) (De Bofarull 1850, p. 25). |

| 75 | […] antequam pervenissemus ad apicem regie dignitatis is a sentence that is repeated in more than one document issued by the king before he was crowned. References in (Palacios Martín 1975, p. 207, n. 9). |

| 76 | |

| 77 | Regarding ritualizations and propagandistic and legitimating intentions, a chapter that continues to be of interest is that of (Nieto Soria 1993, pp. 23–26). |

| 78 | |

| 79 | “ell pensa que aixi con los sants apostols e dexebles de nostre Senyor Déus Iesuchrist estaven desconsolats, que axi los seus sotsmeses estaven ab gran tristor per la mort del senyor rei son pare; e que axi com Iesuchrist, lo jorn de la Pascha, primer vinent, que fo diumenge, a tres diez en abril del any MCCCXXVIII, que ell confortas e alegras si mateix, e sos germans e tots los seus sotsmesos. E ordona quel dia davant dit de Pascha, que prelats e richs homens e cavallers e missatgers e ciutadans e homens de viles honrrades de regnes fossen a la ciutat de Çaragoça; e aquell dia beneyt ell se faria cavaller, e pendria la corona beneyta e astruga ab la major solemnitaat” (he thinks that in this way the holy apostles and disciples of our Lord Jesus Christ were disconsolate, that in this way his subjects were very sad due to the death of the king his father; and that like Jesus Christ, on the next day of Easter, which was Sunday, 3rd April 1328, he comforted and cheered them, and his brothers and all his subjects. And he ordered on that day of Easter, that prelates, rich men, knights, messengers, citizens and men from honourable kingdoms were in the city of Zaragoza; and that blessed day he became knight and took the blessed and fortunate crown with the greatest solemnity) (De Bofarull 1860, chp. CCXCIV, p. 564). |

| 80 | “y entravan todos de luto por la muerte del Rey Don Jayme II. Y assi lo estuvieron los días, que hubo de aquella semana hasta el Viernes Santo a la tarde, que el Rey mandò, que el dia siguiente Sabado Santo dicha el Alleluya, se lo quitasen, y se aparejasen muy de propósito para la fiesta” (And they all entered in mourning due to the death of James II. And they were in this way from that week until the afternoon of Good Friday, when the king ordered that the following day, Easter Saturday, their period of mourning should be lifted and they should get ready for the celebration) (Blancas 1641, book I, p. 30). |

| 81 | According to Marc Bloch, “tout contribuait donc, et de plus en plus, à évoquer à propos des vêtements portés par le souverain, le jour où il recevait l’onction et la couronne, l’idée des ornements sacerdotaux ou pontificaux” (Bloch 1961, p. 204). See also (De Azara 1913, p. 221). |

| 82 | The king wore an alb “es vestí camís, aixi com si degues dir missa” (he wore a chemise as if he was going to say mass) and a stole, which “era tan rica e ab tantes perles e peres precioses, que seria fort cosa de dir ço que valia” (was so rich and with so many precious pearls and stones, that it would be difficult to say what it was worth). The maniple was also “molt rich e ab gran noblesa” (very rich and with great nobility) (De Bofarull 1860, chp. CCXCVII, p. 573). |

| 83 | “E con fo revestit e hach comensada la missa, lo dit senyor rei, ell mateix, pres la corona del altar e las posa al cap” (And as he was dressed and had commenced mass, the King took the crown off the altar and placed it on his head) (De Bofarull 1860, chp. CCXCVII, p. 574). |

| 84 | “e com aço hach feyt, lo senyor arquebisbe de Toledo e el senyor infant En Pere e el senhyor infant En Ramon Berenguer adobarenla li” (and as that was done, the Archbishop of Toledo and the infante Peter and the infante Ramon Bereguer dressed him in it) (ibid.). |

| 85 | |

| 86 | |

| 87 | Ibid. |

| 88 | As stated in (Palacios Martín 1975, p. 217). A recent study of this matter is that of Aurell and Serrano-Coll (2014). |

| 89 | The illuminated versions with scenes representing the act of self-coronation are preserved in the Fundación Lázaro Galdiano de Madrid, Ms Reg. 14425 and the Biblioteca Nacional de Francia, Ms. Esp. 99. |

| 90 | I follow the timeline offered by Palacios Martín (1975, p. 239), who asserts that the first ceremonial text was produced in Zaragoza shortly before the Peter IV’s coronation and was used in that ceremony. He would subsequently return to the text to make new annotations for the later versions. For more on the arguments that Palacios uses to support his hypothesis, see (ibid., p. 239ff). |

| 91 | Halfway through his reign, Peter IV wanted to reorganise and regulate his house and court and added to his ordinances the ceremonial text for the coronation of kings. The text was more solemn and included the coronation of queens, which did not feature in the previous version because the king was not married. He took the opportunity to rectify certain concepts that had not been properly formulated in the first version, perhaps because it was written hastily (ibid., p. 259). In addition to the unfinished version kept in El Escorial (Man. & III.3), there are three complete versions: one in Latin, another in Catalan and a third in Aragonese. They may have been connected with the three capital cities of the three kingdoms at the core of the Crown of Aragon; that is, Zaragoza, Barcelona and Valencia. See (Palacios Martín 1994a, p. 14). |

| 92 | These terms are from the codex of the Escorial: “dita la oración debe el rey prender la corona del altar e debesela meter en la cabeza, e que no le ayude ninguna persona, ni larzebispe ni infant ne ninguna persona otra de cualquier condicion que sea ni tocar la pont” (after the prayer is said, the king must take the crown from the altar and put it on his head, and nobody must help him, not the archbishop, nor the infante nor anybody else of any status, nor may they touch it?) (Palacios Martín 1975, p. 237). Likewise, the codex of Saint Michael of the kings explains that: Acabada esta oración, el Rey tomará de encima del altar esta corona y él mismo se la ponrá en la cabeza sin que nadie le ayude” (after the prayer, the king will take the crown from the altar and he himself will place it on his head with anybody else’s assistance) (Palacios Martín 1994b, p. 222). In a similar manner, the codex in the Museo Lázaro Galdiano says: “E aquesta oración dita el rey prenga la corona de sobre l altar e ell mismo pósela en su cabeça sin ayuda de otra persona” (And once this prayer has been said the king must take the crown from the altar and he himself place on his head without the help of any other person) (San Vicente Pino 1992, vol. II, p. 33). |

| 93 | Fragment extracted from the manuscript in the Fundación Lázaro Galdiano de Madrid, Ms Reg. 14425, fol. 19r. |

| 94 | “[…] veèmnos en tan gran perill, ço es, per lo dia quins era lo pus honrat que null altre que nos esperasen en aquest setge, e que aquell que teniem per pare, quant en aquest mòn, diguès aytals paraules en honrar la sua esglesia e sòn archabisbat en gran detrment e subïugació de nostre règne” (we saw oneself in great danger, that is, on the most honourable of all days we did not expect this attack of whom we consider our father, that in that moment he should say those words with the aim of honouring the church and his archbishopric in great detriment and subjugation of our kingdom (De Bofarull 1850, p. 81). |

| 95 | “E tantost fet lo dit atorgament, Nos isquem de la sacrestia” (And having given in to him, we left the sacristy) (ibid.). |

| 96 | “E Nos diguèmli que prou. Bastaba, e que nons adobás nens tocas nostra corona, que Nos lens adobariem. E axi no lin donam licencia, de la qual cosa ell fò molt mogut, e non gosà fèr res apares” (And we said enough. That was enough now, and that he should not adjust or touch our Crown, that we would do it on our own. And in this way we denied him licence, and he was surprised and did not dare to do anything) (ibid.). |

| 97 | Depending on the ceremonial text used, the archbishop proclaimed that crown was placed on his head by the unworthy hands of the bishops: licet ab indignis episcoporum manibus capiti tui imponitur. I cite (Palacios Martín 1975, p. 245, n. 32). In the second ceremonial text and its copies, these terms are replaced by others that reflected what really happened during the ceremony. |

| 98 | Although there are precedents in his own dynasty, which I discussed in (Serrano-Coll 2017, pp. 337–62). |

| 99 | |

| 100 | Although we are told that nowhere does it state that this sword was ever used, despite sending the archdeacon of Zaragoza, don Ponce de Tahuste, to Sicily to fetch it. We also know that he sent emissaries to obtain jewels from various places (Blancas 1641, book I, p. 63). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Serrano-Coll, M. De Modo Qualiter Reges Aragonum Coronabuntur. Visual, Material and Textual Evidence during the Middle Ages. Arts 2020, 9, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010025

Serrano-Coll M. De Modo Qualiter Reges Aragonum Coronabuntur. Visual, Material and Textual Evidence during the Middle Ages. Arts. 2020; 9(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerrano-Coll, Marta. 2020. "De Modo Qualiter Reges Aragonum Coronabuntur. Visual, Material and Textual Evidence during the Middle Ages" Arts 9, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010025

APA StyleSerrano-Coll, M. (2020). De Modo Qualiter Reges Aragonum Coronabuntur. Visual, Material and Textual Evidence during the Middle Ages. Arts, 9(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010025