1. Prologue

No conceptual framework within art history more effectively addresses

Mieke Bal’s (

2007) concept of “migratory aesthetics” or the observation by

Saloni Mathur (

2011) and

Anne Ring Petersen (

2017, p. 88) that “traditional notions of location, origin and authenticity seem obsolete and in urgent need of reconsideration” than the subject of Jewish art, and within that difficult-to-define subject, that of Israeli art. As Hava Aldouby has noted,

1 Israeli art presents a unique inflection of the global condition of mobility—which contributes to the problem of easy definition.

Nothing could be more appropriate to the discussion of Israeli art alone, as Aldouby has observed, or to the larger definitional problem of “Jewish art”, than the suggestion of exploring it through

Nicolas Bourriaud’s (

2010) botanical metaphor of the “radicant”, and thus the notion of “radicant art”. The important distinction that Bourriaud offers between

radical and

radicant plants—whereby the former depends upon a central root, deep-seated in a single nourishing soil site, and the latter is an “organism that grows its roots and adds new ones as it advances…” with “…a multitude of simultaneous or successive enrootings” (ibid., p. 22)—is a condition that may be understood for both Israeli and Jewish art, past and present.

Indeed, if there is a flaw in the metaphor as one might apply it to Israeli art, it is that Bourriaud seems to intend it to reference the current age, which he designates as “altermodern”, but Israeli art has been radicant in evolving for more than a century—or arguably, as a subset of “Jewish art” (and that designation is too simple, as we shall see), for much longer than that. Or perhaps one might apply Bourriaud’s formulation to Israeli art through the idea that the migratory aspect of Israeli identity can be both contemporary and first-hand or inherited at a distance of several generations, and always connected to diverse diasporic rooting centers. Indeed, as Aldouby has noted, the image of “the Wandering Jew may be considered the archetypal radicant, predating Bourriaud’s “altermodernity” by nearly two millennia”.

2. Jewish Art and Israeli Art

It might be useful to place this discussion briefly within the two definitional contexts suggested above. The first of these is the definition of “Jewish art”—particularly since the primary purpose of the founding of the Bezalel School of Art in Jerusalem in 1906 was to create what might be construed as Jewish national art. The second of these is what eventuated out of Bezalel and the responses to it over the following century or so: the creation of Israeli art, for which it is important also to demand a definition.

Defining “Jewish art” offers an invigorating challenge. Does one approach the issue from the perspective of the art, and in that case, is the criterion the subject, the style, particular symbols, or intent or purpose? None of these criteria attach themselves straightforwardly to the adjective “Jewish” when that adjective is appended to the noun, “art”. Or should the criterion be the identity of the artist—and in that case, does one refer simply to the artist’s birth as a Jew? What of artists who have converted into or out of Judaism: does their art suddenly become or cease to be “Jewish?” Or should one refer to the artist’s

convictions as a Jew? So too, are those convictions based on defining Judaism as a religion or as a body of customs and traditions or as a culture or a race or a nationality or a civilization? What, more than incidentally, of Jewish ceremonial objects—“Judaica”—made almost exclusively, at least in Christendom, by Christians until the late nineteenth century? Is the criterion of usage sufficient to qualify a given object as part of “Jewish art”?

2These conceptual aspects of the definitional question may be multiplied by historical and geographical considerations. When did Judaism as we understand or define it actually begin? Solomon’s Temple was built for the Israelites—and designed and constructed by Tyrians, for that matter, consistent with the Northern Canaanite temple style—a millennium before the words “Judaism” or “Jew/ish” came into use to refer to a diasporic people with a fully canonized Bible and a distinctive calendar of festival and life-cycle events. Israelite and Judaean art and architecture are foundational to, but not the same as “Jewish” art and architecture. Perhaps the location should provide the definitional criterion. French and Spanish and Italian art may be easily enough reduced, if necessary, to “art made in France and Spain and Italy”, but the crutch of geography is not available where Jewish art is concerned. A century ago, when, after two millennia of inhabiting every corner of the globe, Jews began to return in large numbers to their point of geographic beginning, that place of return might well have been expected to offer the answer to the question. Simply, one might have said: “‘Jewish art’ is art made in a Jewish land”.

This idea received a kind of negative confirmation at that time when Martin Buber suggested that there had been no Jewish art across the centuries of dispersion because there had been no Jewish land in which it could be rooted. While Buber’s formulation was wrong because it was too narrow, it was well enough accepted to help galvanize support within the Zionist leadership for the formation of an arts school—Bezalel—in Jerusalem, under the directorship of Boris Schatz. In a Jewish land, Jewish art would be created.

The irony, of course, is that the Jewish land is called Israel, not Jewland—its very name chosen to sidestep the diasporic past, and to leapfrog back to an Israelite-Judaean self-conception. Nor, when Israel came into full-fledged existence a half-century after the founding of the Bezalel School, were all Israelis—and thus Israeli artists—necessarily Jews. Israeli art, then, offers no solution to the problem of defining Jewish art. It does, however, present an intriguing array of issues that pertain to the question of defining Israeli art.

One effective answer to this last issue is to refer to Israeli art as radicant art. It is, however, necessary to delineate the specifics of

how Israeli art is radicant in order to distinguish it from other modes of radicant art. This is analogous to the problem raised with RB Kitaj’s suggested definition of “Jewish art” as “Diasporist art”. What at first seems effective loses its effectiveness when he goes on to observe—correctly—that there are other groups that have experienced dispersions; for in so doing, he eliminates what makes Jewish art particular (it becomes just one of any number of forms of Diasporist art), so one is back where one started.

3 3. “Israeli” Painting from the Era of Early Bezalel to the Late Twentieth Century

These questions are reflected in the ideology of the Bezalel School when it opened in 1906. Schatz believed that he could create a Jewish

national art.

4 It was the conviction of Schatz’s supporters within the Zionist leadership that a fully Jewish

land could not exist in only

political or even

spiritual terms; that the complete realization of the Zionist dream must include

cultural self-expression; that, in particular, the visual arts would offer a statement that we are

here, in

our land, to

stay.

All art may be called political, in the linguistic and conceptual senses of making a statement by or for the polis—the community—from Assyrian friezes to Roman historiated columns to Renaissance triptychs. Israeli art is political in a particular sense. At its inception, a half century before the existence of an independent State, Israeli Art began to develop as part of the program of defining what the state should be. Schatz created a school named for the artisan mentioned, in the book of Exodus, as the deviser of the Tabernacle in the wilderness, where the covenantal Tablets of the Law were housed. The very name of the school, then, connoted both a biblical backdrop for proto-Israeli art and a sense of redemption and return to the Land.

The work of the early Bezalel period—from 1906 to 1929—was marked by a series of distinctive features, the intention of which was to offer an indigenous Art-of-The-Land-and-Its-People.

5 Schatz strove to transform his own East European Academic background into a

style that interwove “Near Eastern” motifs, spoke with deliberate

symbols (the rising sun of Jewish nationalist rebirth, for example), and addressed itself to appropriately heroic—particularly biblical—

subject matter. The artists who arrived during these early decades—Slavic Jews like Schatz, and often artistically trained in Germany and/or France—were overwhelmed, as he was, by the landscape itself, and sought to express it in their work. Arts-and-crafts style copper (associated with King Solomon’s mines), silver, and olivewood work (the

material substance of the hills recast as art), carpets and carved ivory work, new Hebrew calligraphy embellished with arabesques (

Arab-esques), light-filled canvases reflecting the unique colors that wash over the land from the intensity of the sun—these features re-visioned the forms of the land and its groves of trees, sandy stretches, chaotic rocky shapes in dynamic tension with the geometries of Arab architecture: Whitewashed blocks punctuated by bright blues and greens and a profusion of curved and domed forms. The natural and architectural landscape elements were viewed as an extension of a visual continuum stretching back to antiquity.

The enthralling landscape included the human component: the Arabs themselves, whose garb and style of life, in conjunction with the elements of land and architecture, seemed to push the mind’s eye back to biblical Israel. Biblical characters, as well as the structures associated with them by tradition and imagination—from “David’s Tower” to “Rachel’s Tomb”—were intertwined in their exotic orientalism with the rough-hewn spirit in which arriving pioneers—halutzim—to Eretz Yisrael enveloped themselves. So, too, contemporary heroes were portrayed, just as their biblical heroes were: Theodor Herzl, “Father” of Zionism, above all.

The painters of the “founders” generation—an emphatically radicant group from diverse locations and cultural traditions—were particularly caught in webs of light: Reuven Rubin (1893–1974) from Rumania, for example, from his studies of nascent Tel Aviv in the early 1920s to his scintillating images of the Galilee shortly before his death in the early 1970s; Menachem Shemi (1897–1951) from Lithuania and Haim Glicksberg (1904–1970) from Russia, each with his own reflections of “Arab” blue-green hues and domed forms; Joseph Zaritsky (1891–1985) from Russia, with his early turn toward Impressionist style and his later turn towards the Abstract Expressionism imported from America. Nachum Gutman (1898–1980; Romania) and Israel Paldi (1892–1979; Russia) are part of this early group, joined shortly by Anna Ticho (1894–1980; Moravian Austro-Hungary), whose sweeping pen and pencil drawings of the landscape in intimate, almost abstract detail, have become world-recognized.

In the many decades between Schatz and the present day, one may observe a constant exploration of different styles—radicant expression mirroring the Jewish diasporic experience in an array of artists from an array of places, including the occasional figure, like Moshe Castel (1909–1991), who was born in Palestine itself. We also observe that, while the first impulse of incoming artists, under the spell of Schatz, was to turn inward to the land and its diverse elements, already by the late 1920s, the desire to create an indigenous, Jewish (Palestino-Israeli) art was encountering pushback from the desire to be part of the international artistic mainstream with its centers in Paris, Berlin, London—and later, New York.

6 The fear of becoming an isolated cultural backwater soon drove some of the first arrivals, as well as other, later-arriving artists outward. This is reflected in the revolt against Schatz and his Jerusalem school and the founding of other schools—most obviously, the Midrasha, in Tel Aviv, founded in 1946. Tel Aviv, like its art scene, was outward-facing, towards the Mediterranean and Europe, whereas Jerusalem rises in the country’s interior; Tel Aviv was newly founded in 1909, as the first

Jewish city in the land, whereas Jerusalem is a millennia-old continuum and the focus of a

handful of Faiths.

Moreover, by the late 1920s and early 1930s, the infatuation with Arab culture was overwhelmed by political realities (the Arab anti-Jewish riots in Hebron and Jerusalem, for example); “Arab” subject-matter ceased to be as romantic and thus as prominent as before. So too, while one may continue to observe the response, in painting, to the wonderful light that stains the stones of Jerusalem and scorches the beaches of Tel Aviv and the shadows of the Negev, it shouldn’t surprise one to see different, often darker reflections, as Nazism was a growing roar on the European scene and more incoming artists arrived. Jacob Steinhardt (1887–1968), born in Germany, is best known for his woodcuts, in which even Middle Eastern subjects seem to be part of an Eastern European world. Marcel Janco (1895–1984; Rumania) arrived as an already well-known Dadaist, and Mordecai Ardon (1896–1992; Poland) arrived, reluctantly, by way of training at the Bauhaus School in Weimar and influence from Paul Klee—and remained, enthusiastically, later to become the head of a revived Bezalel School.

7 During the period when he directed Bezalel, the 1950s, Ardon called for a struggle against the “cosmopolitan tendencies of capitulation to the Paris School”, and pushed for a search into biblical and Jewish sources for Israeli art. That call, shortly after the State of Israel came formally into existence, represents the first public statement of a self-conscious attempt to create Israeli art. It echoes Schatz’s declarations, but in a different key: indeed, the attempt to create “Jewish National Art” had, in the narrow sense, failed, but it had been transformed into the desire to create Israeli Art.

If art in the 1940s was largely eclipsed by the severity of political pre-occupations, the 1950s yielded further diversity—including the more prominent inclusion of Jewish historical subject matter, in no small measure as a consequence of the horrifying immediacy of the events of the 1940s, but also including the modernist urge to stay away from clear narrative subject matter altogether, pioneered among others, by Lithuanian-born Yehezkel Streichman (1906–1993) Polish-born Yehiel Krize (1908–1968), and German-born Aharon Kahane (1905–1967)—the third of these a founder in 1948 of the avant-garde-focused “New Horizons” group. Conversely, Ardon’s work, in particular, at that time, began to reflect painfully on the crucible of Israel’s birth: The Holocaust followed so shortly by the War of Independence. Israeli painting in the 1950s and the 1960s is sometimes lyrical, sometimes harshly expressionistic; it is sometimes figurative, more frequently abstract; occasionally cubistic and often surrealistic. As the familiar artists continued their productivity, newer names—such as Arie Aroch (b. Russia; 1908–1974), Yosl Bergner (b. Vienna; 1920–2017), Yaacov Wexler (b. Latvia; 1912–1995), to mention a few—appear, expanding the visual response to the Israeli scene.

In the 1960s, the coming of age of a critical mass of native-born artists—such as Yaacov Agam, born in 1928; Ori Reisman, born in 1924; and Raffie Lavie, born in 1937—offered a sense of “Israeliness” that was unself-conscious, in some cases whether a given artist was working in Israel or spending more time in a studio in Paris or New York. As new artists’ groups and associations declared themselves during the 1960s—the “Kibbutz Artists”, led by Reisman; the “Group of 10”, pupils of Aaron Avnie, in revolt against him; the “10+” group in response to them, with Lavie as a key figure—still further aesthetic patterns emerge: Op and Kinetic Art, of which Agam remains, many decades later, the key progenitor and practitioner, for example; and Pop Art.

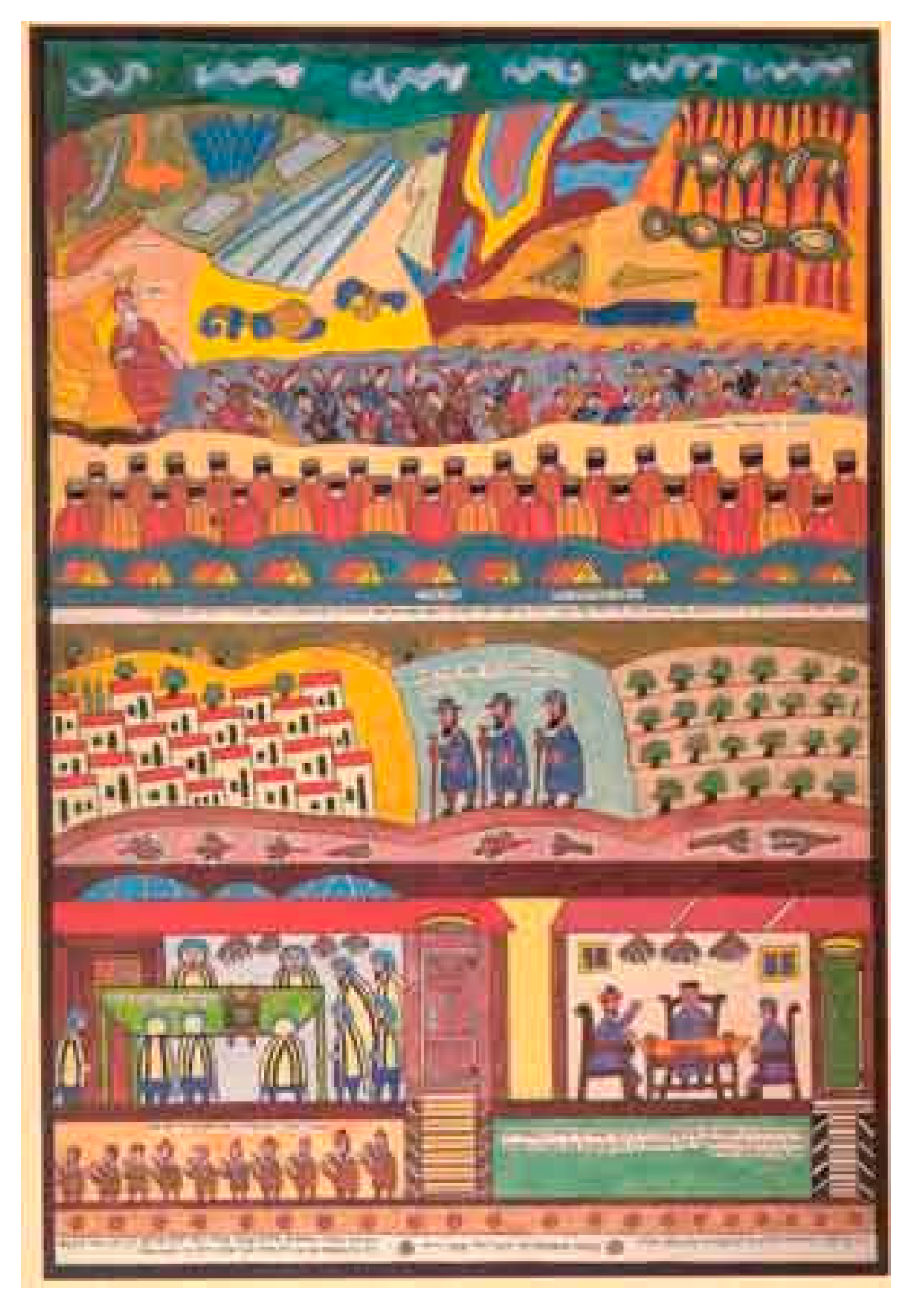

Still other painters and movements reveal the diverse modes of Being-in-the-World that resonate through Israeli art as, from the 1960s into the 1970s, native painters grew side-by-side with the still-active patriarchs and matriarchs of the early years. Groups like “

Tatzpit”, “Autumn Exhibitions”—expressions, as “New Horizons” and “10+” had been, of the desire to be in stride with contemporary trends in the art of the Western world—occasionally brought to the fore older artists like Moshe Kupferman (born in Yaroslav, Poland; 1926–2003), together with the younger ones gaining a name, like Uri Lifschitz (born on Kibbutz Givat HaShloshah; 1936–2011) and Dida Oz (born in Venice, Italy, 1941). Lithuanian-born (1933) Samuel Bak’s wonderful surrealism began to be recognized during this period, as did the work of Israel’s “Grandpa Moses”: Shalom of Safed (Shalom Moscowitz; 1887–1980). The watchmaker-turned-Naive-artist in his 60s, reflects in a particular manner part of the radicant heritage of Israel and Israeli painting. His juxtapositions of biblical scenes with contemporary celebrations of the festivals based on those scenes are accompanied by lengthy inscriptions—Hebrew, for the biblical images; Yiddish, for the contemporary reflections (

Figure 1).

4. Israeli Sculpture: From “We Are Here” to “What Are We?”

During this same sweep of decades, Israeli sculpture also evolved, particularly monumental sculpture—often monumental memorials. The size of the country and its uniquely war-torn history gives death a personal ubiquity: there was virtually nobody in the first fifty years of Israel’s existence who lacked relatives or close friends who had fallen in Israel’s wars (or during the Holocaust). Significantly, these sculpted monuments most often remind the viewer of tragedy, rarely boasting of victory.

Visual statements of the Jewish presence in the Land, after centuries of wandering, also reflect the constancy of war within Israeli life and the willingness to sacrifice in order to remain present in the Land—from Bessarabian-born (1892–1960) Abraham Melnikov’s “Memorial to the Fallen at Tel Hai” of 1926; to Berlin-born (1916–1977) Yitzhak Danziger’s “Negev Monument” of 1958; to Kibbutz Beit Alpha-born (1934–2015) Ezra Orion’s “Monument to the Golan Brigade” of 1972 and the “Monument to the Fallen” in the Jordan Valley, also from 1972, by Igael Tumarkin (b. 1933); to Dahlia Me’iri’s vast 1978 “Memorial at Moshav Moledet”—in which, at the edge of the collective farm where she was born (in 1951) and grew up, the names of the dead describe a path, from the Holocaust to the War for Independence, to Suez in 1956, to the Sinai in 1967 and again to the Sinai in 1973. The proliferation of public sculpture reflects an insistent desire to redirect the radicant origins of Israeli Jewish art into something firmly rooted in new-old soil.

Not all Israeli sculpture is monumental or memorial, of course. Danziger’s classic “Nimrod”, is neither—but this work of 1939 became iconic as a progenitor of the “Canaanite” sculptural movement, depicting the legendary biblical monarch who, in the rabbinic tradition, is represented as having built the Tower of Babel in an era that predates the Israelite period. Danziger is one of many individual Israeli stylistic and conceptual radicants, for decades later he became known for his abstract monumental public sculpture. Jerusalem-born (1932–2009) Buky Shwartz’ “Tower of Cubes” (ca. 1965) is a monumental, but not memorial, rhythmic heavenbound abstraction, as is Ezra Orion’s late 1970s “

Ma’alot” (“Ascents”). The latter is at once an allusion to the Psalms of David (“Songs of Ascents”), a pun on the Dream of Jacob (The Dream of

Israel) of a ladder between heaven and earth upon which angels float up and down, and simply a rhythmic diagonal pattern of white rectangles—made of industrial prefab stairs—against the blue Jerusalem sky (

Figure 2). No image more emphatically symbolizes the city itself, with its internal conflicts and contradictions between profane ambitions and sacred aspirations.

Diversity is as apparent in Israeli sculpture as in painting; abstract work is as common as figurative; self-reflection accompanies historical and diversely philosophical (not necessarily “Jewish”) consciousness. Agam’s kinetic “Beating Heart” (1971) is at once a concretization of the abstract notion of beating rhythms and, in the number of its tubes—eighteen—reflects a specifically Hebrew-Jewish-Israeli symbolism, in that the heart is the source of life and in Hebrew numerology, the consonants in the word “life” (hai) add up to eighteen. Michael Gross’ (1920–2004) “Stool” (1972), on the other hand, engages Plato: The form of a stool, which he offers us, is neither really a stool in form (one of the legs doesn’t reach the ground) nor is it a stool in function (it can’t be used as a stool); it is simply a work of art—or is it? This last question underscores Gross’ interest, as well, in continuing the play between meaning and meaninglessness in art engaged by Dadaism.

5. Israeli Art from Zionist Pasts to Zionist and Post-Zionist Presents

Tel Aviv-born Menashe Kadishman (1932–2015), commenting in the early 1980s, seemed to scoff at the very

idea of art, particularly of the sort that appears in the formal contexts of museums and galleries: he painted on trees, and then sculpted outdoor trees of bronze; he painted repeated images of sheep on canvas, and then painted (literally) on sheep (he was, he said, simply a shepherd, so he was merely responding to his environment) (

Figure 3). He claimed to be emphatically apolitical in his art—which was, of course, a political statement. Tel Aviv-born (in 1930) Dani Karavan’s environmental sculptures overrun the landscape with an array of stylized geometries that simultaneously grow out of the land and enforce a counterpoint to it, in their perfected regularities. His work is found throughout Europe, as well, where he often lives and works. His sculpture is, he commented,

Israeli, because Israel is where he was born and grew up, Israel is reflected in the forms and configurations he creates, Israel remains inside him even if he creates outside the country.

8The country—both the polity and the land—is Israeli art. It is the constant source of reflections and refractions. Jerusalem-born (in 1932) Raffi Kaiser’s monumental mid-1980s pencil and paper drawings of nooks and crannies of the land—in part done, from memory, while in Paris—were both detailed evocations of Eretz Yisrael and deliberate echoes of Anna Ticho’s work of two generations earlier. Younger artists in the 1980s and early 1990s—some of them recent graduates of Bezalel at that time, in its third, post-Schatz, post-Ardon, incarnation—began to reflect on the Zionist dream, from the era of Herzl and Schatz to the time of statehood to the emergence of Israel as a military power. Some painted and drew and sculpted the uncomfortable vision of post-1982, intifada Israel. Some, like Kadishman, insistently denied that they were reflecting on the political realities that the size and intensity of Israel make it impossible to ignore.

What Ardon had said in the early 1950s—“the artist is at all times engaged in the political life of his time, conveying his feelings about it. This we must do. This must be our life”—echoed in Israeli art four decades later, in the 1990s, and continues to do so today, whether by native-born or immigrant artists; whether they work in Tel Aviv or Jerusalem or an obscure kibbutz—or in Paris, Berlin, or New York; whether in the art-forms so briefly addressed here, or in architecture, photography, video, installation, or conceptual art, all of which have come to have astonishing levels of participation by Israeli artists.

The media have expanded, very much in step with the larger art world, while the kinds of issues that are being addressed still reflect both a desire to be part of that larger world and/or to eschew it in search of something somehow indigenous; and also the desire both simply to make art for its own aesthetic sake and/or to address a range of socio-political issues, some of which may be understood as uniquely Israeli and some of which are universal foci of art today.

There is more, of course. To begin with, the non-Jewish population of evolving Israel also includes artists who, by the 1980s were becoming more visible—as those who would previously have been called

Palestinians (as pre-Israel Jews living in Palestine would also have been called) have been

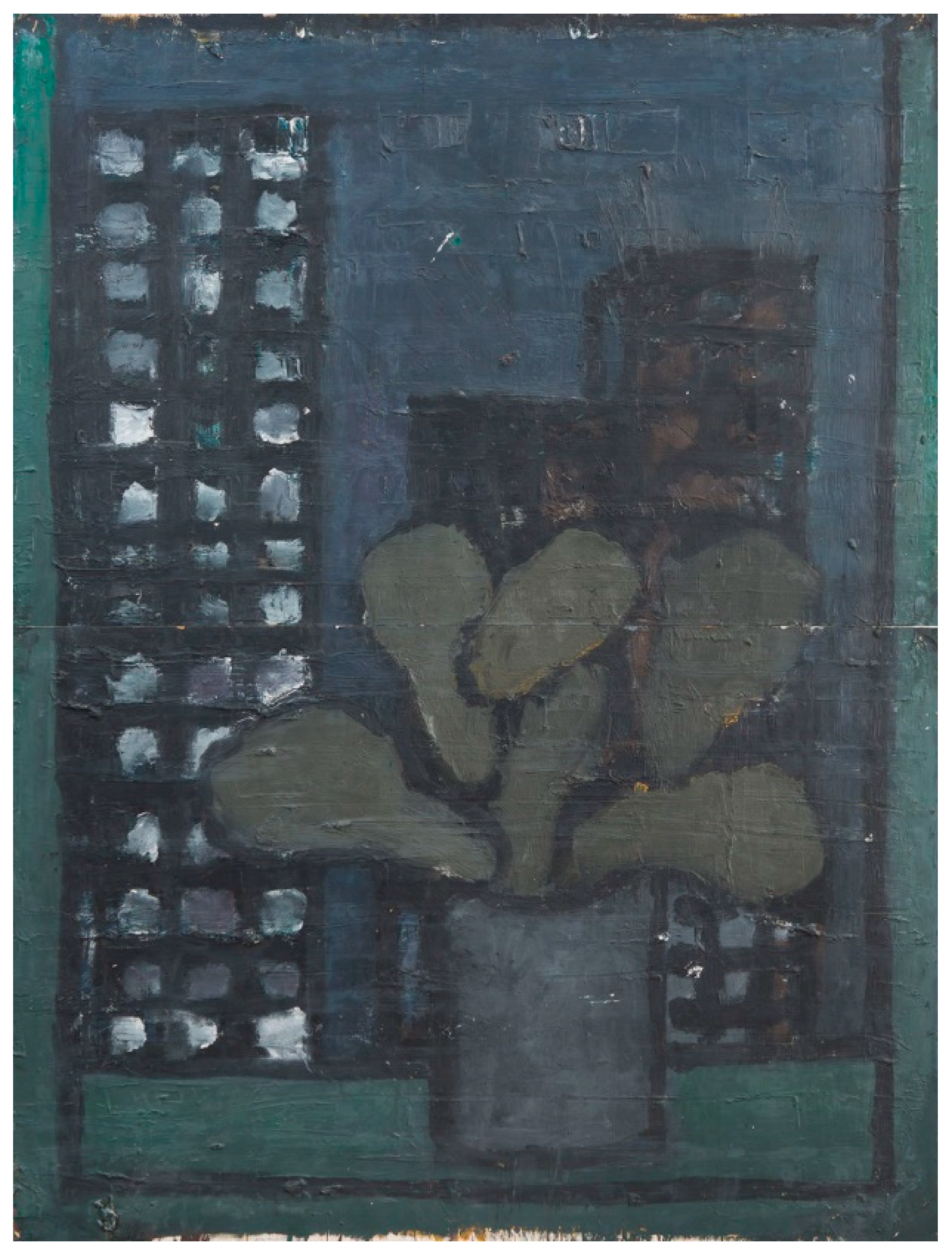

Israelis since 1948, resident in Jerusalem or Jaffa or Haifa—or elsewhere: Christian or Muslim or Druze Israeli Arabs. Thus, for instance, Asim Abu Shakra (1961–1990), among notable painters within this group, was born in the northern Arab Israeli city of Umm al-Fahm. Neither necessarily tied to the Jewish Israeli tradition nor rebelling against it, per se, he reflects on Israeli identity as heterogeneous, with a specific visual vocabulary. He repeatedly depicted the Israeli cactus—the

sabra—and its fruit. What had become the quintessential symbol of (Jewish) Israelis—native-born Israelis are, after all, called Sabras—has been repurposed as a symbol of the Palestinians (

Figure 4).

The sabra plant is difficult to uproot; bulldozers may tear it up, but it somehow emerges again from the soil. If that has been said historically of the Jews, it is intended by Abu-Shakra to refer to Palestinian Muslim and Christian Arabs, who use sabra bushes to mark building plots and the boundaries of villages from which they cannot be uprooted. Even if it is removed from the natural soil and potted—many of Abu-Shakra’s images are of potted sabras—it remains what it is. Just as Dani Karavan could and often did point out that, wherever he was living and creating art, he remained an Israeli, Asim Abu Shakra’s sabra images suggest the same radicant idea from different soil but yearning toward the same sky: That wherever they are located or mislocated, Palestinians remain Palestinians. At the same time, the sabra bush that, as a hedge, separates, as a shared symbol, reflects a common interest in return and renewal.

Asim’s second cousin, Walid Abu Shakra (1946–2019) lived for the last half-century of his life in England. Like Asim, Walid was born and grew up in Umm al-Fahm, where his brother, Said, founded a successful art gallery that showcases art by both Palestinian and Israeli artists. Walid was one of a handful of Palestinians to attend an Israeli art school, (trailblazing the path later followed by Asim), coming to study at the Avni Institute in Tel Aviv, in 1967. He immigrated to London in 1972, but constantly returned to study the Israeli-Palestinian landscape and people, and to paint—from images of sabra bushes to abstractions composed of rich blocks of color. Like Asim, Walid Abu Shakra has had work exhibited in and collected by Israeli museums.

Assad Azi (b. 1955), whose father served—and died serving—in the Israel Defense Forces, and who was beginning to rise to prominence in the mid-1980s, is a Druze: Part of a religious minority whose members are found mainly in Lebanon, Israel and Syria, where their majority neighbors are either Jews or Muslims.

9 Indeed, the village in which he was born is part Christian, part Muslim and part Druze; he grew up as part of a minority between two minorities that, in most non-Israeli contexts, are majorities. One finds the evidence of all

four traditions in his work, together with resonances from Matisse and Giacometti, Byzantine icons and Inca art. In a series of self-portraits done in the mid-1980s these diverse elements were harnessed to a brilliant rhythmic progression that suggested Monet’s haystacks become the self as Icon, framed in arabesques and suggestions of Jewish ceremonial decor. Such an eclectic synthesis is, of course, quintessentially Israeli (and profoundly Jewish).

On the other hand, any number of Jewish Israeli artists began, in the aftermath of the Lebanon incursion of 1982, and with increasing vehemence as the twentieth anniversary of the Six-Day War approached, to offer a post-Zionist or even what some might call an anti-Zionist vision on their canvases, or at the very least, a re-considered vision of the very landscape around them. One particularly interesting series—of 38 oil paintings, 38 impressions on newspaper of the landscape paintings, and some still lifes done after samples of flora from the area—was done in 1993–1994 by South African-born Larry Abramson (b. 1954), of the Jerusalem Hills near Kibbutz Tzuba. Those same hills had been painted, a decade earlier, by Zaritsky at his most abstractly lyrical. Abramson’s images included the ruins of the Palestinian Arab village deserted after the 1948 war that had not shown up in Zaritsky’s images. Including—and then defacing—this element in a naturalistic manner, Abramson intended to criticize an Israeli viewpoint that would erase the Palestinian identity from the appropriated territory.

More politically overt, a few years earlier, in the old building of the original Bezalel School, an exhibition of posters was organized in 1987 to mark the twentieth anniversary of the conquest and occupation of Gaza and the West Bank. Two of the more noteworthy features of that exhibition were the strident nature of some of the work produced by Jewish Israeli artists—well-known figures like Tumarkin and Lavie, as well as by lesser known ones, like Dov Haller and Gabi Klezmer—and the fact that several non-Jewish Palestinian artists also participated.

Among these was Taleb Dweik, (b. 1952, Jerusalem) who eventually became the President of the League of Palestinian Artists (1990–1996) and has exhibited all over the world. Dweik’s work, then and since, typically offers a colorful, often abstract palette so that his imagery tends to lead the viewer away from the ugly politics outside the canvas into a realm of beauty and calm: his work offers a kind of visual tikkun olam (“repairing the world”), reminiscent, as such, of paintings by Mark Rothko. In recognizing that Jerusalem and its people are his most consistent subject, however, one may also recognize the suggestion of yearning for an earlier, more innocent and childlike pre-Occupation Jerusalem—particularly in one of his images, in which he has suggested the gerrymandering idea of the Wall by creating a Jerusalem skyline compositionally broken into thirteen vertical slabs that suggest chunks of the city broken by chunks of obstruction.

There is certainly some irony to the fact that Israel is the only place in the Middle East where artistic work raising questions about government policy could be exhibited. There is also an obvious contentiousness between what an artist like Dweik recalls as “innocent” and what Israelis of the same generation or older, might recall of the 1949–1967 pre-Occupation era when Jewish access to the Old City was all but forbidden to them—or that, regardless of its negative aspects, the Wall quickly cut down suicide bombings by 90%. That said, Dweik’s perspective offers a track parallel to the yearning perspective often found in diasporic Jewish art and resisted by Jewish Israeli artists—and there is further irony that his voice found a place in, of all places, the old Bezalel school building. The radicant nature of Israeli art is clear here: Different sources, not one source, and different directions multiplying those sources.

One can follow the issue of political commentary into the work of any number of Israeli and Palestinian artists in the decades since 1987. A 2008 installation by the film-maker, Sobhi al-Zobaldi (b. 1961) called “Part-ition” offers 72 playing cards laid out for a game on a table. The cards are made from a cut-up, large-scale, pre-Israel map of Palestine—a map given to him as a young teenager, which adorned the walls of his room as a youth in Ramallah as well as in his home in New York in the 1980s.

10He returned to Palestine in 1994 after the Oslo Accords, but felt that he could not display it, for shame: “I felt embarrassed with the map, as though I didn’t want it to see me anymore, or see what was going on…”—expressing shame and betrayal for the deals made by Arafat with Israel that he deemed “humiliating and doomed”: The map as a symbol of loss. Now cut up as cards on a table with a chair on either side, the map both signifies a Palestinian perspective and a perspective that an Israeli might question—what could Arafat have negotiated that would have been sufficient for Sobhi to feel good about it? However, it also reflects the Israeli political reality that provided an acceptable radicant context for the installation.

So, too, in the case of Nisreen Najjar’s (b. 1985, Nazareth) “Route 443” (2010), an installation at

Al-Housh (The House of Arab Art and Design), in Jerusalem. The mixed media sculpture takes its name from the Israeli road that connects Jerusalem to Tel Aviv as an alternative to the primary Road #1 that does the same thing. The artist perceives it as a road intended to connect a network of settlements by cutting though Palestinian land. She has shaped it as a grotesquely enlarged toy racing track stuffed into the gallery space, entering from a wall, somewhat randomly rising and falling before exiting into a window grille. Her view is that this is a road made for the convenience of Jewish settlers, (although it serves both Israelis and Palestinians in connecting Tel Aviv and Jerusalem), that can go in whatever direction they choose, regardless of topography or the needs of the indigenous population—but it also recalls, with tongue in cheek, the phrase “roadmap to peace” and the “peace process” as understood by Israelis and Americans—as opposed to Palestinians.

11In May 2016, an entire conference was devoted to this subject—in Bethlehem: that is, in a city on the West Bank governed by Israel. It was an international conference, in which the contributors came from Palestine and various other countries—but not Israel. That a conference the substance of which was criticism of Israel took place within the area that the Israelis have administered for half a century is consistent with the democratic and at the same time radicant nature of Israel and Israeli art.

Of course, questions and comments by Jewish Israeli artists have also expanded beyond Tumarkin’s overt criticism in the Bezalel exhibit in 1987 or Abramson’s in 1993–1994. Particularly photographers capture—or stage—moments that raise issues, whether these pertain to Israeli society in the street and in the home or to the condition of the Palestinians under Israeli domination.

Adi Nes’s 2006 chromogenic print, “Untitled (Abraham and Isaac)” offers the ironic reality of homeless street people in the country created to provide every Jew with a home (

Figure 5). The elderly urban street person who pushes his sleeping son in a shopping cart packed with flotsam and jetsam is more akin to Abraham the wanderer than Abraham the founding father of a dramatic new faith, and more akin to the prophet’s diasporic descendants—as Wandering Jews—than to the still-largely rural vision of a century ago in which all Jews coming to the Land would build it and be rebuilt by it. The image would seem to question whether all Jews coming to Eretz Yisrael find themselves well cared for. It might be further noted that Nes (b. 1966), who is openly gay, and whose family is from Iran, has also taken on the particularized regional machismo that characterizes so much of Israeli culture, particularly in staged images involving soldiers.

12Rina Castelnuovo’s (b. 1956) photo, “Gaza Border” (2009), depicts an Orthodox Jewish Israeli soldier, at sunrise, wearing his tallit and t’fillin as he recites his morning prayers atop a military tank parked in a grassy field. A stream of black smoke rises from a building in the distance, the end of its plume hovering just over the distant Gazan town illuminated by the newly emerged sun. The issue of piety and religion as it pertains to the politics of defending Israel from Hamas and of devastating Gaza and its inhabitants in the name of that defense, would appear to be very much on the artist’s mind—and perhaps in the recesses of her mind, too, the notion that Gaza’s Hamas (unlike the Palestinian Authority that governs the West Bank) considers itself a specifically religious organization, on the basis of which it still denies Israel’s right to exist.

6. Radicant Israeli Art from Present to Future

The array of roots derived from and extending toward different sources in the context of Israel and thus of Israeli art offers a unique level of intensity, which has continued to expand over the past few decades, facilitated by conflicts and disputes from within and without—which include the question not only of homecoming, but of who is permitted to come home and to where. Thus, the Law of Return has yielded diverse outcomes for Jews coming from America or the former Soviet Union or Ethiopia or India—based in theory on how Israel’s rabbinate defines “Jewish” and whether or not that rabbinate concludes that a given population is truly Jewish or not; is one’s Judaism sufficiently rabbinic? Is one’s parentage distinctly Jewish on one’s mother’s side? Was one’s conversion into Judaism facilitated by an approved rabbinical authority?

If automatic entitlement to Israeli citizenship is imbedded within the question of who qualifies as “Jewish”, this sort of issue has extended in the past few decades in different directions—this is, after all, not a radical but a radicant reality—to post-Oslo Israeli Arabs re-defining themselves as Palestinian Israelis, and potentially to Palestinians beyond the Green Line who assert the right and wish to return to a pre-1948 location within the Green Line. So, religion and politics, as always, interweave each other and, as always, offer fodder for all kinds of artists.

Conversely, for political or economic reasons, a growing cadre of Israelis has gravitated away from Israel, to establish themselves—but often as part of Israeli ex-pat communities—in New York and Berlin most obviously, and also in other places, and as visual artists occupy notable places within these communities; thus the radicantity of Israel and its artists keeps expanding yet further. The definition of Israeliness and of Israeli art becomes still more complex—encompassing Jews from all over the world but also non-Jewish groups such as Druze, Circassians, and Muslim and Christian Palestinian Arabs.

One might chart this ongoing radicantity by way of a handful of particular exhibitions that have marked out familiar and newly acknowledged plots of soil for the roots of Israeli art. In 1991, the Israel Museum mounted an exhibit called “Routes of Wandering”, in which the curator, Sarit Shapira, “proposed a model of wandering from center to margin as key to comprehension of Israeli modernism and Israeli-Jewish existence” (

Ofrat 1998, p. 333). That notion, together with the inauguration in 1990 of the Museum’s large international pavilion is part of the statement that yes, clearly, by now, following decades of aspiration, Israeli art is fully integrated and in step with the best in the contemporary art world, as one of Israel’s key art historians, Gideon Ofrat put it (ibid.). While the concept of “wandering”, and the plural “routes” could hardly be more in tune with this discussion, Shapira’s and Ofrat’s summary analysis seems keyed, not to the

radicant reality of Israel, but to a less dispersive

radical model; and reflects only on

Jewish Israeli existence.

Conversely, the 1987 Bezalel exhibition inclusionist revolution continued and expanded exponentially with the posthumous retrospective exhibition of Asim Abu Shakra’s work at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in 1995, five years after his tragically early death from leukemia, and—like the other shoe dropping—with the retrospective of Walid Abu Shakra’s work also at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, simultaneous with an exhibit of his work in the gallery founded by Said Abu Shakra in their hometown, Umm al-Fahm, in 2012—at the very time a museum of Palestinian art was being planned for that city.

This last exhibition also came on the heels of the exhibit,

Men in the Sun (

2009), at the Herzliyah Museum of Art, in 2009, which showcased the work of 12 Palestinian artists. Amal Jamal, writing in the exhibit’s catalogue (co-curated by Hanna Farah-Kufer Birim and Tal Ben-Zvi), observed that “[a] Palestinian, by essence, is made from the lost culture, from the dialectic relationship with memory and with the foreign culture on which he draws, and at the same time criticizes. The lost, expropriated time, like culture and as part of it, continues to exist in the consciousness of life here and there, as if refusing to acknowledge the parting”.

13This could easily be a statement by a Jewish thinker regarding Diaspora Jews. It certainly echoes the continuous longing for Jerusalem, for Zion, over the years of dispersion, expressed in the liturgies of Judaism, and offers its own expressive version of that dialectic relationship with memory and with the cultures through which Jews have moved, as participants who almost never fully cease to be outsiders. Jamal’s words echo centuries of Hebrew poetry—one thinks of the iconic words of Yehudah HaLevi (1075/1086–1141): “My heart is in the East, while I am in the chains of the West…”—that offer the refusal “to acknowledge the parting” from Jerusalem.

When the Zionist idea emerged into activation in the late nineteenth century, the only question for some Jews was “how?”—through human action or divine action, or a synthesis of both? Should our goal be political or spiritual—or, eventually, cultural? As we began this essay by noting, the radicant nature of early Bezalel art and the first public statuary in pre-state Palestine were in part an attempt to answer that question by their insistent statements of the Jewish presence: To remain in the Land. More than a century later the question has evolved from that we are here to how and what we are, and further, who is the “we” who participates—and who remains outside even if living inside the Land?

In participating in the larger world of art, Israel was represented, surely with some sense of irony, at the Venice Biennale of 1995—the year of Asim Abu Shakra’s Tel Aviv Museum of Art retrospective—by an enormous library, affirming the identity of Jewish Israel as word-focused, rather than land- or image-focused. Put otherwise, the pavilion both recalled the label first applied by Muhammad to the Jews: “People of the Book”. It underscored the unrooted identity of Jews, who could take their words and prayers and books with them, wherever they were forced to go, rather than emphasizing the rootedness of Jews in communities marked by gargantuan houses of prayer—or rooted again within their Land.

Two years later, at the 1997 Biennale, Sigalit Landau (b. 1969 in Jerusalem), demolished the interior space of a shipping container: For her, “home” had become transitory packing that now became an object of expressed anger—suggesting that, having come home, Israelis remain somehow homeless—whether due to the competing narrative of the Palestinians, the pressures of their neighbors, or their own yearning, artistically or otherwise, to be part of the wide world through which they have wandered for nearly two millennia, accepted, at times, but rarely fully embraced.

We might twist this screw one further turn, by reference to an expansive exhibition project inspired directly by the Venice Biennale. One of the more recent instruments through which Israel as an art-eager polity has sought to engage both itself and the world at large has been through the Jerusalem Biennale—as of this writing, offering its fourth iteration—organized by Rami Ozeri in the fall, around the High Holidays. Inspired by its much older Venice counterpart, the Jerusalem Biennale is an inherently radicant form of Israeli visual expression. To begin with, the myriad exhibits that shape it are located all over the city of Jerusalem in varied venues, not all of them galleries or museums—in one case, in the 2017 Biennale, a single exhibit, organized through the Jewish Art Salon in New York City, was on display in two different locations, due to the politics of showing some of the art in a museum in which the director felt that his largely ultra-Orthodox visitors would be offended.

So, too, the Biennale’s varied exhibitions come from all over the world, and not just Israel. As for content, each iteration offers a particular theme and relates that theme to Jerusalem, so that the entire Biennale is, as it were, directed toward a center; but the artistic response to the theme is not only varied in terms of specific subject, style, symbolic language, and medium; it ranges from exhibits that offer the work of a single artist to those offering a group exhibit presenting the work of several dozen artists. The theme in the third iteration, in 2017, for example, was “Watershed”—referring to the diverse ways in which Jerusalem may be seen as a watershed: politically, geologically, spiritually, for starters—to which artists responded variously.

Israeli-born (in 1951) and -resident Avner Sher’s individual exhibit, an installation at the Tower of David Museum, “Alternative Topographies” engages the “tension between the eternal and transient [as] a metaphysical and concrete characteristic of Jerusalem… and the relationship between destruction and reconstruction…” for a city the old part of which, covering less than one square kilometer, has for thousands of years been the focus of “nations, kingdoms and religions [who] have fought and struggled for control of this territory” (

Jerusalem Biennale 2017, p. 422). The installation may be understood as a radicant examination of the city itself, with its historical inputs that derive from diverse geographic starting and ending points.

By contrast, the four-person exhibition, “Balfour at 100”—including the work of Beverley-Jane Stewart, Chanan Mazel, Jacqueline Nicolls, and Ruth Schreiber, (the first from London, the second New York-born and resident in Jerusalem, the third from London, and the fourth London-born and resident in Jerusalem)—directed itself to that watershed moment in Jewish and Zionist history, when a substantial European power acknowledged the theoretical legitimacy of a “Jewish” state. The multi-media installation reflected from different angles on the significance of that moment a century earlier—including the process of apprehending the Land long before Lord Balfour’s statement was articulated.

How very different from the exhibit, “War or Peace”, which offers the work of eight Indian artists reflecting on this universal subject from the perspective of parallels between Israel and India, both of which gained independence in the aftermath of World War II and a reconfiguration of much of the world, particularly its erstwhile colonial empires. One may discern iconic images—like the outline of the Buddha’s head, or the lotus blossom, (but stuffed within the interior of a gun image)—that are not expected in the visual vocabulary of Israel. Interestingly, the community of Bene Israel Jews—who arrived from India into Israel after 1948 and are dispersed throughout the country—are not part of the exhibition. Not that they necessarily should be, but they would immediately recognize its imagery as other Israelis might not, as a radicant population that the Chief Rabbinate only recognized after 1961 as Jews and thus as full Israeli citizens.

The radicant nature of the Jerusalem Biennale—I have merely touched the tip of an entire series of icebergs from only one of the Biennale’s iterations—is unequivocal. It brings this discussion full circle, not only with regard to Israel and its art as radicant, but to the cognate questions of how to define Judaism and Jewish art, Israel and Israeli art. Israeli art is intense, and, more than 110 years after Schatz opened the Bezalel School, reflects a Schatz-like, if transformed, determination. It is not a means of assuring a three-dimensional Zionist reality-of-the-future; it is part of the struggle to shape the painful contours of a present reality toward that aspect of normalcy that pushes a polity to make art and toward the art-making that pushes a polity toward some sort of normalcy—in Israel’s case, an intensely radicant normalcy.

The Israeli effort to be a “normal” society, (and the irony that the need for such an effort underscores the abnormalcy of Israeli reality) is reflected in Israeli art, as in the disproportionate number of galleries, the passion for artists’ colonies and sculpture gardens (even within large industrial complexes, such as at Kfar Vradim, in the Galilee), the proliferation of museums of exemplary quality and the soaring percentage of the population that is enrolled, formally, in artists’ associations. Israeli Art began as part of the statement for Jews and Jewish artists that we are here; it has become part of the question: What are we? Like Israeli society itself, it simultaneously fits as a subset within the rubric “Jewish art” and extends beyond it, including the work of artists who are not Jewish—but Muslim, Christian, and Druze, among others. In layered pasts, in indigenous internationality, in diversity of experience and reflection, Israeli art inevitably echoes what the community is or how its artists feel about or wish to see it—a radicant community, whether in the visions and re-versions of yesterday or the existential questions of today and tomorrow.