Between the Art Canon and the Margins: Historicizing Technology-Reliant Art via Curatorial Practice

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Expanding the Canon

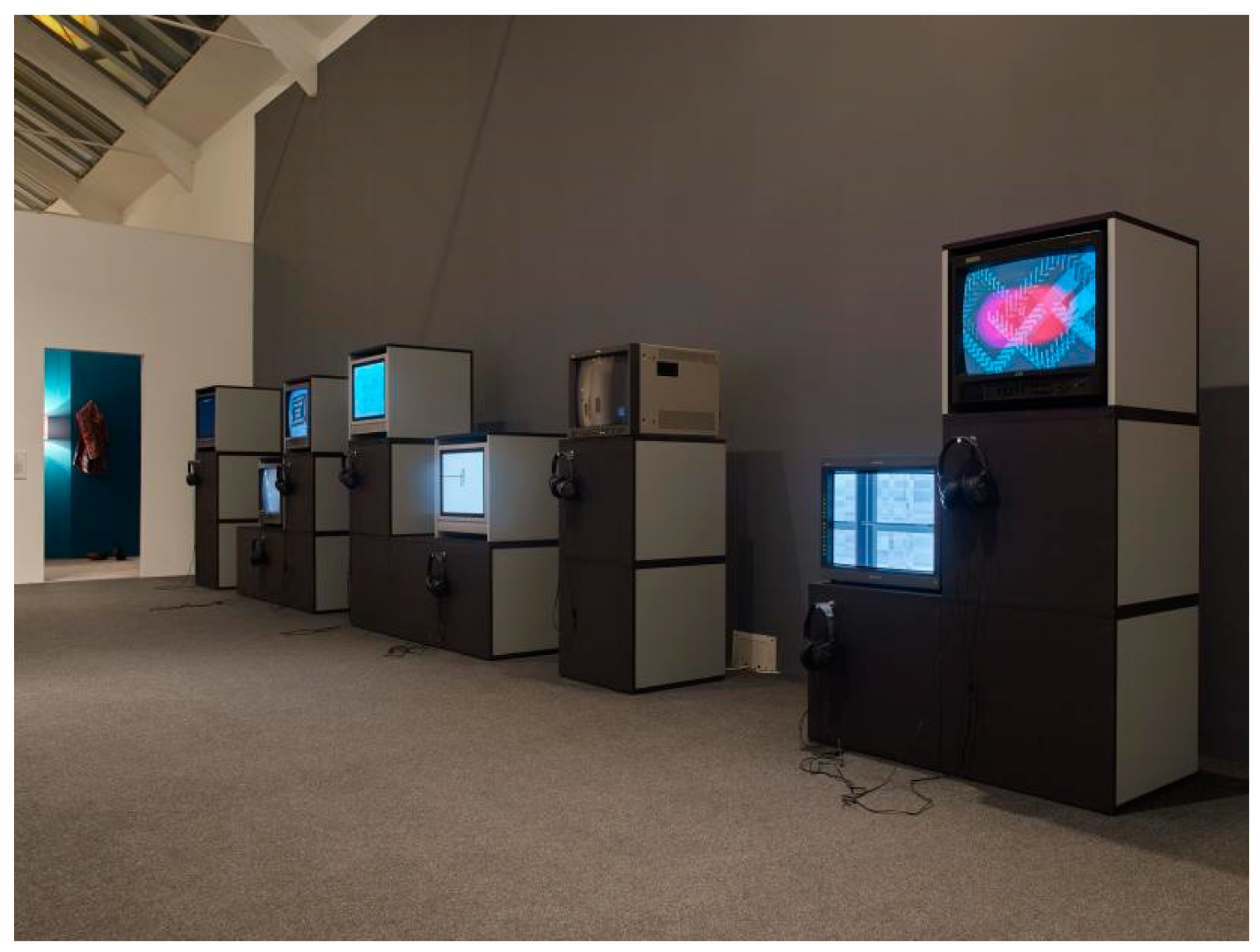

2.1. Display Issues in Exhibiting Technology-Reliant Works

2.2. Exhibiting Digital Histories

Curators like to believe that the activity of curating art—which sometimes (but not necessarily) includes the collection of art—is the necessary precursor to the historicization of art. […] Yet what if instead of looking backwards—assuming those named things which are collected […] are the subject of art history—we look forwards, to how the early stages of curatorial activity (the finding, naming, and showing) inform what, from the wide world, is to become a possible subject for art history in the first place?

2.3. Whose Histories?

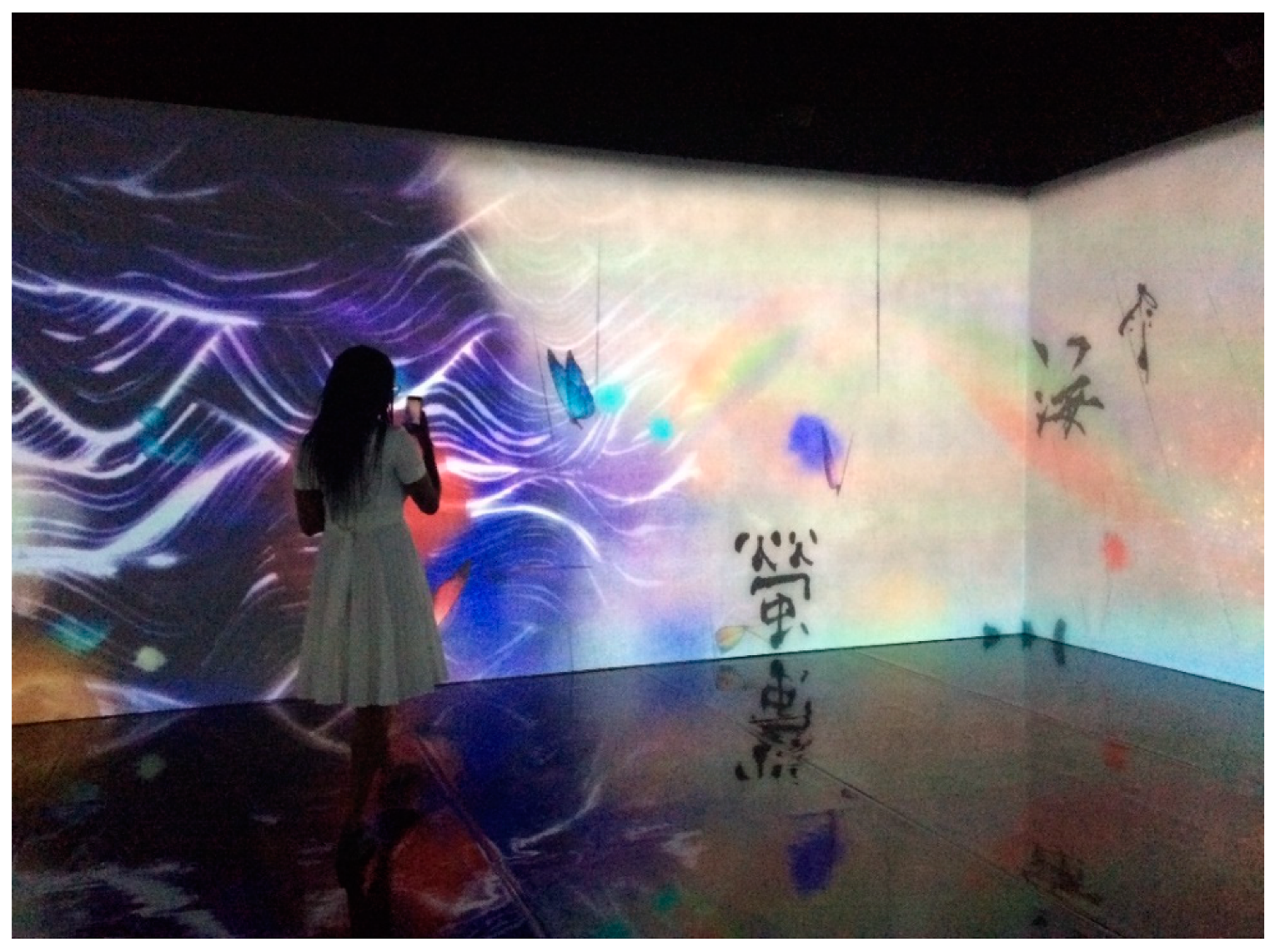

- The aesthetics of the piece and the context within which it was created. As mentioned earlier, the ‘naïve’ aesthetics of the work was one of the first points of criticism. However, amongst the arguments in defence of the art collective was the realisation that their work is “deeply embedded in aesthetics of Japanese art and culture which may require some translation” (Christiane Paul’s response to the email thread). One might as well see this as a ‘culture clash’; the UK traditionally separated art from design, whereas in Japan the two are usually indistinguishable (Beryl Graham’s response, with a reference to Charlie Gere’s (2004) Tate paper “New Media Art and the Gallery in the Digital Age”). Furthermore, TeamLab integrate numerous references from Japanese history and culture in their work which, however, cannot be easily understood from a Western-audience perspective. The first work that one witnesses when visiting their headquarters in Tokyo is a screen with an animated story showing how agricultural work takes place in the rice fields throughout the year. Informative and yet entertaining, one of the first things they mention is that they want to communicate their ideas without excluding the ‘fun factor’ or becoming overtly educational in their nature. Equally, a funny-looking frog that appears in many of their interactive creations is, in fact, Choju-giga, a central character from one of the oldest picture scrolls in Japanese history, dating back to the 12th century.11 My Japanese acquaintances could automatically read all those references, aesthetics of the image, and humbleness of the spectacle itself, whereas I had to ask endless questions only to begin to comprehend the ways in which they saw their work and managed to combine commercial and artistic projects. The above logic certainly informs their practice, which, in turn, generates issues relating to the context and receivability of non-Western or non-canonical art that can be applied to numerous contemporary cases of technology-reliant art, and the subsequent questioning of the tools we have, as researchers and/or exhibition visitors, to decode the messages conveyed.

- Curatorial choices that placed What a Loving and Beautiful World outside the main exhibition space of the AI: More than Human exhibition. Although other works were exhibited outside The Curve (where the largest part of the exhibition was shown), they were all on the same floor level. However, one needed to change floors and enter a separate space to experience the TeamLab piece (Figure 4). Understandably, this could only be shown in an isolated space with no other visual or sonic interference but its placement in a separate location still conceptually excluded it from the rest of the exhibition. Institutional logistics aside, the politics of space play an essential role in the understanding and historicization of a technology-reliant work.

3. Conclusions/Towards a Holistic Exhibition Regime

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cook, Sarah. 2003. Towards a Theory of the Practice of Curating New Media Art. In Beyond the Box—Diverging Curatorial Practices. Edited by Melanie Townsend. Banff: Banff Centre Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Sarah. 2014. Murky Categorisation and Bearing Witness: The Varied Processes of the Historicization of New Media Art. In New Collecting: Exhibiting and Audiences after New Media Art. Edited by Beryl Graham. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 203–19. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Sarah. 2008. Immateriality and its discontents: models of curating new media art. In New Media in the Whiet Cube and Beyond: Curatorial Models for Digital Art. Edited by Christiane Paul. Berkeley and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dare, Eleanor, and Elena Papadaki. 2016. Bare Nothingness: Situated objects in embodied artists’ systems. In Experimental Multimedia Systems for Interactivity and Strategic Innovation. Edited by Ioannis Deliyannis and Christine Banou. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 16–48. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, Matthew. 2016. Eleven Pro-Tips for Art Plus Internet. Available online: http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/eleven-pro-tips-art-plus-internet (accessed on 24 June 2019).

- Gere, Charlie. 2004. New Media Art and the Gallery in the Digital Age. Tate Papers. Available online: https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/02/new-media-art-and-the-gallery-in-the-digital-age (accessed on 24 June 2019).

- Graham, Beryl. 2014. New Collecting: Exhibiting and Audiences after New Media Art. Edited by Beryl Graham. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Beryl, and Sarah Cook. 2010. Rethinking Curating: Art after New Media. Cambridge and London: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grau, Oliver. 2003. Virtual Art—From Illusion to Immersion. London and Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Reesa, Bruce Ferguson, and Sandy Naime, eds. 1996. Thinking about Exhibitions. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Heinich, Nathalie, and Michael Pollak. From Museum Curator to Exhibition Auteur: inventing a singular position. In Thinking about Exhibitions. Edited by Reesa Greenberg, Bruce Ferguson and Sandy Nairne. London: Routledge.

- Kholeif, Omar. 2018. Goodbye, World! Looking at Art in the Digital Age. Berlin: Sternberg Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meigh-Andrews, Chris. 2006. A History of Video Art: The Development of Form and Function. Oxford and New York: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Mondloch, Kate. 2010. Screens: Viewing Media Installation Art. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, Paul. 2007. The Curatorial Turn: From Practice to Discourse. In Issues in Curating Contemporary Art and Performance. Edited by Judith Rugg and Michèle Sedgwick. Chicago and Bristol: Intellect, pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Papadaki, Elena. Curating Screens: Art, Performance, and Public Spaces. Ph.D. Thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London, London, UK.

- Paul, Christiane. 2008. New Media in the White Cube and Beyond. London, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, Christiane. 2003. Digital Art. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Shanken, Edward A. 2010. Contemporary Art and New Media: Toward a Hybrid Discourse? Available online: https://artexetra.files.wordpress.com/2009/02/shanken-hybrid-discourse-draft-0-2.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Trodd, Tamara. 2011. Screen/Space—The Projected Image in Contemporary Art. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Oliver Grau’s (2003, pp. xi, 4) Virtual Art—From Illusion to Immersion provides a useful mapping of this terrain, focusing on computer-simulated virtual environments and a genealogy of old and new media of illusion. Graham and Cook (2010), Mondloch (2010), Kholeif (2018), Shanken (2010), Meigh-Andrews (2006), and Trodd (2011) have equally chose one specific term as a consistent point of reference (whilst acknowledging the problematics of this definition), explaining how its characteristics represented the respective objects of study and research interests. For an analysis of the ‘question of definition’, see also Elena Papadaki’s (2014) Curating Screens—Art, Performance, and Public Spaces (doctoral thesis). |

| 2 | This point of the curator’s role is also raised at various times in the published discussions of the BALTIC series, as well as in the—now defunct—CRUMB forum. |

| 3 | At the workshop ‘Digital Audiovisual Preservation in Communities of Practice’ (Presto Centre and Institut National de l’Audiovisuel, Paris, 4 December 2013), Pip Laurenson (Head of Collection Care Research, Tate) presented the challenges that arose when copying obsolete technologies (such as a Sony ½ inch tape) onto new formats, in order to preserve the work and enable its future exhibiting. In the international declaration “Media Art needs global networked organisation and support”, the pressing issue of major works that can no longer be shown or are disappearing is addressed (http://www.mediaarthistory.org/declaration, last accessed on 24 June 2019). The preservation of digital data is a fertile subject of research, although it expands beyond the scope of the present paper. However, it demonstrates that there is a history behind technology-bound pieces, as well as exhibiting limitations that both need to be known and acknowledged by curators. |

| 4 | “[…] thus Internet-founder Ted Nelson might see hypertext where art critic Jack Burnham sees sculpture or media theorist Lev Manovich sees database-driven video narrative” (Graham and Cook 2010, p. 1). |

| 5 | For a further analysis of the context/content dichotomy and subsequent curatorial judgements of quality, see (Dare and Papadaki 2016). |

| 6 | Videographies—The Early Decades (The Factory—National School of Fine Arts, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens, 13 July–31 December 2005). |

| 7 | More information from the official link from Barbican Centre website: https://www.barbican.org.uk/hire/exhibition-hire-bie/digital-revolution (last accessed on 24 June 2019). |

| 8 | Conrad Bodman, Guest Curator of Digital Revolution, on a clip promoting it (“Welcome to the Digital Revolution”, link as above). |

| 9 | Official exhibition link from the Whitechapel Gallery: https://www.whitechapelgallery.org/exhibitions/electronicsuperhighway/ (last accessed on 24 June 2019). |

| 10 | At the same time, a quick YouTube or Google search reveals a plethora of home-made videos from exhibition spaces and exhibits, that are usually taken by visitors without permission and then uploaded online. |

| 11 | Interview with TeamLab in their headquarters in Tokyo, June 2018. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papadaki, E. Between the Art Canon and the Margins: Historicizing Technology-Reliant Art via Curatorial Practice. Arts 2019, 8, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030121

Papadaki E. Between the Art Canon and the Margins: Historicizing Technology-Reliant Art via Curatorial Practice. Arts. 2019; 8(3):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030121

Chicago/Turabian StylePapadaki, Elena. 2019. "Between the Art Canon and the Margins: Historicizing Technology-Reliant Art via Curatorial Practice" Arts 8, no. 3: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030121

APA StylePapadaki, E. (2019). Between the Art Canon and the Margins: Historicizing Technology-Reliant Art via Curatorial Practice. Arts, 8(3), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030121