Spatial Dimensions in Roman Wall Painting and the Interplay of Enclosing and Enclosed Space: A New Perspective on Second Style

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Second-Style Wall Decoration: Framing the Actors in the Room

2.1. A Glimpse at Other Media: Figure and Architectural Ground on Marble Reliefs and on an Ancient Theatre’s Stage

2.2. ‘Mistakes’ in Perspectival Construction and How to Make Sense of Them

2.3. Vistas on Natural Landscapes: More of the Same? The Rear Wall of Cubiculum M and the Case of the Odyssey Frescoes from the Esquiline

2.4. Framing the Actors in the Room in Second Style: Summary

3. Towards a Larger Picture: Framing the Actors in the Room and the Succession of Styles in Roman Wall Painting

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PPM—I. Baldassare, T. Lanzillotta, and S. Salomi. 1990–2000. Pompei. Pitture e Mosaici. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana. |

| PPP—I. Bragantini, M. deVos, and F. P. Badoni. 1981–1985. Pitture e Pavimenti di Pompei, Rome: Ministero per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali. |

References

- Anderson, Maxwell L. 1987–1988. The Imperial villa at Boscotrecase. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 45: 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Andreae, Bernhard. 1962. Der Zyklus der Odysseefresken im Vatikan. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Römische Abteilung 69: 106–17. [Google Scholar]

- Andreae, Bernhard. 1977. Das Alexandermosaik aus Pompeji. Recklinghausen: Bongers. [Google Scholar]

- Anguissola, Anna. 2010. Intimità a Pompei: Riservatezza, condivisione e prestigio negli ambienti ad alcova di Pompei. Image & Context 8. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Barbet, Alix. 2009. La peinture murale romaine, rev. ed. Paris: Picard. [Google Scholar]

- Barbet, Alix, and Annie Verbanck-Piérard, eds. 2013. La villa romaine de Boscoreale et ses fresques. Actes du colloque international organisé du 21 au 23 Avril 2010 aux Musée Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire de Bruxelles et aux Musée Royal de Mariemont. Arles: Ed. Errance. [Google Scholar]

- Barnabei, Felice. 1901. La villa pompeiana di P. Fannio Sinistore scoperta presso Boscoreale. Rome: Tipografia della R. Accad. dei Lincei. [Google Scholar]

- Beacham, Richard, Drew Baker, Martin Blazeby, and Hugh Denard. 2013. The Digital Visualisation of the Villa at Boscoreale. In La villa romaine de Boscoreale et ses fresques. Actes du colloque international organisé du 21 au 23 Avril 2010 aux Musée Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire de Bruxelles et aux Musée Royal de Mariemont. Edited by Alix Barbet and Annie Verbanck-Piérard. Arles: Errance, vol. 2, pp. 164–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, Bettina. 1994. The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 76: 225–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, Bettina. 2002. Playing with boundaries: Painted architecture in Roman interiors. In Built Surface. Architecture and the Visual Art from Antiquity to the Enlightment. Edited by Christy Anderson. Aldershot: Ashgate, vol. 1, pp. 15–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, Bettina, Stefano De Caro, Joan R. Mertens, and Rudolf Meyer. 2010. Roman frescoes from Boscoreale: The Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor in reality and virtual reality. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Beyen, Hendrik Gerard. 1938. Die pompejanische Wanddekoration vom zweiten bis zum vierten Stil. The Hague: Nijhoff, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Beyen, Hendrik Gerard. 1957. The Wall Decoration of the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor near Boscoreale in its Relations to Ancient Stage Painting. Mnemosyne 10: 147–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyen, Hendrik Gerard. 1960. Die pompejanische Wanddekoration vom zweiten bis zum vierten Stil. The Hague: Nijhoff, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Biering, Ralf. 1995. Die Odysseefresken vom Esquilin. Munich: Biering & Brinkmann. [Google Scholar]

- Von Blanckenhagen, Peter H., and Christine Alexander. 1990. The Paintings from Boscotrecase, rev. ed. Mainz: Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Borbein, Adolf. 1975. Zur Deutung von Scherwand und Durchblick auf den Wandgemälden des zweiten pompejanischen Stils. In Neue Forschungen in Pompeji und den anderen vom Vesuvausbruch 79 n. Chr. verschütteten Städten. Edited by Bernhard Andreae. Recklinghausen: Bongers, pp. 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau, Philippe, Ulpiano Bezerra de Meneses, Claude Vatin, Guy Donnay, Edmond Lévy, Anne Bovon, Gérard Siebert, Virginia R. Grace, Maria Savvatianou-Pétropoulakou, Elyzabeth Lyding Will, and et al. 1970. Exploration archéologique de Délos XXVII: l’îlot de la maison des comédiens. Paris: Boccard. [Google Scholar]

- Cain, Hans-Ulrich. 1989. Relief mit archaistischem Viergötterzug [cat. No. 92]. In Forschungen zur Villa Albani. Katalog der antiken Bildwerke I: Bildwerke im Treppenaufgang und im Piano nobile des Casino. Edited by Peter C. Bol. Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, pp. 288–92. [Google Scholar]

- Coarelli, Filippo. 1998. The Odyssey Frescos of the via Graziosa: A Proposed Context. Papers of the British School at Rome 66: 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colpo, Isabella. 2010. ‘Ruinae … et putres robore trunci’. Paesaggi di rovine e rovine nel paesaggio nella pittura romana (I secolo A.C.—I secolo D.C.). Rome: Antenor Quaderni 17. [Google Scholar]

- Colpo, Isabella. 2013. Paysage de ruines dans la peinture romaine (I er siècle av. J.-C.—I er siècle ap. J.-C.). In Les ruines. Entre destruction et construction de l’Antiquité à nos jours. Actes de la journée d’études de l’Équipe d’Accueil Histara, INHA, 14 octobre 2011. Edited by Karolina Kaderka. Rome: Campisano, pp. 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Croisille, Jean-Michel. 2005. La Peinture Romaine. Paris: Picard. [Google Scholar]

- Croisille, Jean-Michel. 2010. Paysages Dans la Peinture Romaine: Aux Origines du Genre Pictural. Paris: Picard. [Google Scholar]

- Della Corte, Matteo. 1922. La Villa rustica « Ti Claudi Eutychi, Caesaris l(iberti) », esplorata dal sig. cav. Ernesto Santini, nel fondo di sua proprietà alla contrada Rota (Comune di Boscolrecase), negli anni 1903–1905. Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità 19: 459–78. [Google Scholar]

- Di Franco, Luca. 2017. I relievi ‘neoattici’ della Campania. Produzione e circolazione degli ornamenta marmorei a soggetto mitologico. Rome: Bretschneider. [Google Scholar]

- Dickmann, Jens-Arne. 1999. Domus frequentata. Anspruchsvolles Wohnen im pompejanischen Stadthaus. Munich: Pfeil. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, Nikolaus. 2017. Pictorial space as a media phenomenon: the case of ‘Landscape’ in Romano-Campanian wall-painting. In Le spectacle de la nature: regards grecs et romains. Cahiers des Mondes Anciens 9. Edited by François Lissarrague, Emmanuelle Valette and Stéphanie Wyler. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/mondesanciens/1903#quotation (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- Ehrhardt, Wolfgang. 1991. Bild und Ausblick in Wandbemalungen zweiten Stils. Antike Kunst 34: 28–65. [Google Scholar]

- Elsner, Jaś. 1995. Art and the Roman Viewer: The Transformation of Art from the Pagan World to Christianity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gazda, Elaine K., and John R. Clarke, eds. 2016. Leisure and Luxury in the Age of Nero: The Villas of Oplontis near Pompeii. Ann Arbor: Kelsey Museum of Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, Regina. Forthcoming. The Wall Paintings of Villa A. In Oplontis: Villa A (“of Poppaea”) at Torre Annunziata, Italy: Decorative Ensembles: Painting, Stucco, Pavements, Sculptures. Edited by John R. Clarke and Nayla K. Muntasser. New York: The Humanities E-Book Series of the American Council of Learned Societies, vol. 2.

- Gros, Pierre. 2008. The Theory and Practice of Perspective in Vitruvius’ De Architectura. In Perspective, Projection and Design Technologies of Architectural Representation. Edited by Mario Carpo and Frédérique Lemerle. London: Routledge, pp. 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Grüner, Andreas. 2004. Venvs Ordinis. Der Wandel von Malerei und Literatur im Zeitalter der römischen Bürgerkriege. Paderborn: Schöningh. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, Friedrich. 1889. Die neu-attischen Reliefs. Stuttgart: Wittwer. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, Ernst. 2002. Der zweite Stil in pompejanischen Wohnhäusern. München: Biering & Brinkmann. [Google Scholar]

- Hiller, Friedrich. 1988. Die Entstehung einer subjektivistischen Kunstform in der pompejanischen Wandmalerei. In Bathron. Beiträge zur Architektur und verwandten Künsten für Heinrich Drerup. Edited by Hermann Büsing and Friedrich Hiller. Saarbrücken: Saarbrücker Druckerei und Verlag, pp. 195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Hinterhöller, Monika. 2007a. Typologie und stilistische Entwicklung der sakral-idyllischen Lanschaftsmalerei in Rom und Kampanien während des zweiten und dritten pompejanischen Stils. Römische Historische Mitteilungen 49: 17–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterhöller, Monika. 2007b. Die gesegnete Landschaft. Zur Bedeutung religions-und naturphilosophischer Konzepte für die sakral-idyllische Landschaftsmalerei von spätrepublikanischer bis augusteischer Zeit. Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Instituts 76: 129–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterhöller-Klein, Monika. 2015. Varietates topiorum. Perspektive und Raumerfassung in Landschafts-und Panoramabildern der römischen Wandmalerei vom 1. Jh. v. Chr. bis zum Ende der pompejanischen Stile. Vienna: Phoibos. [Google Scholar]

- Hodske, Jürgen. 2007. Mythologische Bildthemen in den Häusern Pompejis. Die Bedeutung der zentralen Mythenbilder für die Bewohner Pompejis. Ruhpolding: Rutzen. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, Peter E. 2015. The Literary House of Mr. Octavius Quartio. Illinois Classical Studies 40: 171–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsidu, Haritini. 1998. Augusteische Sakrallandschaften. Ihre Bedeutung und ihre Rezeption in der bürgerlichen Privatsphäre. Hephaistos 16: 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kotsidu, Haritini. 2007. Landschaft im Bild. Naturprojektionen in der antiken Dekorationskunst. Worms: Werner. [Google Scholar]

- La Rocca, Eugenio, Serena Ensoli, Stefano Tortorella, and Massimiliano Papini. 2009. Roma: La pittura di un impero. Milano: Skira. [Google Scholar]

- Laidlaw, Anne. 1985. The First Style in Pompeii: Painting and Architecture. Rome: Bretschneider. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, Eleanor W. 1988. The Rhetoric of Space: Literary and Artistic Representations of Landscape in Republican and Augustan Rome. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, Eleanor W. 2004. The Social Life of Painting in Ancient Rome and on the Bay of Naples. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Roger. 1991. Roman Painting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, Katharina. 2008. Bilder machen Räume. Mythenbilder in pompeianischen Häusern. Image & Context 5. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, Katharina. 2013. Neronian Wall-Painting. A Matter of Perspective. In A Companion to the Neronian Age. Edited by Emma Buckley and Martin T. Dinter. Chicester: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 363–81. [Google Scholar]

- Mau, August. 1882. Geschichte der decorativen Wandmalerei in Pompeji. Berlin: Reimer. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoleni, Donatella, and Umberto Pappalardo. 2005. Pompejanische Wandmalerei. Architektur und illusionistische Dekoration. Munich: Hirmer. [Google Scholar]

- Mielsch, Harald. 2001. Römische Wandmalerei. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. [Google Scholar]

- Muth, Susanne. 2007. Das Manko der Statuen—oder: Zum Wettstreit der bildlichen Ausstattung im spätantiken Wohnraum. In Statuen und Statuensammlungen in der Spätantike. Funktion und Kontext. Akten eines internationalen Workshops, München 11.-12.6. 2004. Edited by Franz A. Bauer and Christian Witschel. Wiesbaden: Reichert, pp. 341–55. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, Timothy M. 2007. Walking with Odysseus: The Portico Frame of the Odyssey Landscapes. The American Journal of Philology 128: 497–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1927. Die Perspektive als ‘symbolische Form’. In Vorträge der Bibliothek Warburg 1924–1925. Edited by Fritz Saxl. Leipzig: Teubner, pp. 258–330. [Google Scholar]

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1991. Perspective as Symbolic Form. Translated by Christopher S. Wood. New York: Zone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Wilhelmus J. T. 1963. Landscape in Romano-Campanian Mural Painting. Assen: Van Gorcum. [Google Scholar]

- Plantzos, Dimitris. 2018. The Art of Painting in Ancient Greece. Athens: Kapon Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, Verity. 2002. Viewing, Desiring, Believing: Confronting the divine in a Pompeian house. Art History 25: 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, Verity. 2009. Where the Wild Things Are: Locating the Marvellous in Augustan Wall Painting. In Paradox and the Marvellous in Augustan Literature and Culture. Edited by Philip Hardie. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 41–74. [Google Scholar]

- Squire, Michael J., and Verity Platt, eds. 2017. The Frame in Classical Art: A Cultural History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmaltz, Bernhard. 1989. Andromeda. Ein campanisches Wandbild. Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 104: 259–81. [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg, Susan R. 1980. A Corpus of the Sacral-Idyllic Landscape Paintings in Roman Art. Los Angeles: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson, Philip. 2011. Perspective Systems in Roman Second Style Wall Painting. American Journal of Archaeology 115: 403–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran Tam Tinh, Vincent. 1964. Essai sur le culte d´Isis à Pompéi. Paris: Boccard. [Google Scholar]

- Trümper, Monika. 1998. Wohnen in Delos. Eine baugeschichtliche Untersuchung zum Wandel der Wohnkultur in hellenistischer Zeit. Rahden: Leidorf. [Google Scholar]

- Tybout, Rolf A. 1989. Aedificiorum figurae: Untersuchungen zu den Architekturdarstellungen des frühen zweiten Stils. Amsterdam: Gieben. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. 1988. The Social Structure of the Roman House. Papers of the British School at Rome 56: 43–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. 1994. Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. 2009. Case dipinte: Il sistema decorative della casa romana come aspetto sociale. In Roma. La Pittura di un Impero. Edited by Eugenio La Rocca, Serena Ensoli, Stefano Tortorella and Massimiliano Papini. Milano: Skira, pp. 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zanker, Paul. 1979. Die Villa als Vorbild des späten pompejanischen Wohngeschmacks. Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 94: 460–523. [Google Scholar]

- Zanker, Paul. 1987. Augustus und die Macht der Bilder. Munich: Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Zanker, Paul. 1995. Pompeji. Stadtbild und Wohngeschmack. Mainz: Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Zanker, Paul. 2000. Die Gegenwelt der Barbaren und die Überhöhung der häuslichen Lebenswelt. Überlegungen zum System der kaiserzeitlichen Bilderwelt. In Gegenwelten zu den Kulturen Griechenlands und Roms in der Antike. Edited by Tonio Hölscher. Munich: Saur, pp. 409–33. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Any textbook on Roman wall painting may exemplify this. See, e.g., (Mielsch 2001), p. 29, on the beginning of second style: “Die wichtigste Neuerung ist die Öffnung der Wand”, and p. 67, on the transition from second to third style: “An einer Reihe von Wänden der frühaugusteischen Zeit […] war die Tendenz bemerkbar, die „gebauten“ Architekturen zu reduzieren und die räumliche Illusion fast aufzuheben”. As it combines elements of the third and second styles, statements on the fourth style found in textbooks become more nuanced, emphasizing only the re-appropriation of perspectival architectural illusion as are found in second style, while elements of surface decoration typical for the third style are still in use. See, e.g., (Croisille 2005, p. 81), on the fourth style in general: “Sur le plan formel, ce “style” se caractérise par son hétérogénéité: il exploite librement les tendances antérieures, insistant tantôt sur l´aspect “architectonique”, tantôt sur l´aspect ornemental, dont on a vu les manifestations dans le IIe et IIIe styles”. See also (Ling 1991, pp. 71–72). That the differences between the styles with regard to their spatiality are not clear-cut but a matter of relative importance of either surface decoration or spatial illusion has not passed unnoticed, of course. Third-style walls, for example, maintain some elements of spatial illusion. Accordingly, description of them as surface decoration is made only in comparison to second-style walls, see (Zanker 1987, pp. 281–83; Ling 1991, pp. 52–53, 57; Mielsch 2001, pp. 70–73; Croisille 2005, pp. 68–71; Barbet 2009, p. 104). The interplay of two- and three-dimensionality in Roman wall painting is a recurrent topic in the recent volume on the frame edited by V. Platt and M. Squire: (Platt and Squire 2017, pp. 21–25 [V. Platt and M. Squire], pp. 102–16 [V. Platt]), on spatial ambiguities in third style wall painting, see also (Platt 2009). On the interplay of two- and three-dimensionality in Roman wall painting, see also (Dietrich 2017, especially pp. 13–21). The differentiation of the styles according to the main criterion of the three-dimensionality or two-dimensionality of the painted wall decoration goes back to the groundbreaking (Mau 1882). For the study of the complexities of ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ (another way of tackling the matter of two- and three-dimensionality) created in Roman illusionist wall painting, (Elsner 1995, pp. 49–87), has been groundbreaking. See also (Bergmann 2002). |

| 2 | New York, Metropolitan Museum 20.192.16 (central mythological landscape painting from cubiculum 19); for a detailed description and commentary, see (Blanckenhagen and Alexander 1990, pp. 33–40); most recently: (Plantzos 2018, pp. 324–25). On Perseus and Andromeda in Roman wall painting general, see (Schmaltz 1989; Hodske 2007, pp. 180–84; Lorenz 2008, pp. 124–49). |

| 3 | Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale 8998 (from the peristyle of the Casa dei Dioscuri in Pompei); PPP II, 223; PPM IV, 975, Figure 224; (Lorenz 2008, pp. 131–35, Figure 38, pp. 562–64, cat. no. K 31 [on the house and its mythological pictures in general]). |

| 4 | On this phenomenon, see already (Dietrich 2017, pp. 18–21). |

| 5 | Replacing wall decorations within the Roman house as a specific social context, and especially as the stage of the dominus’ representation, instead of treating it as an autonomous type of art, has been one of the major trends in scholarship on Roman wall painting since the 90s of the twentieth century. For this re-orientation, the works of A. Wallace-Hadrill were groundbreaking (see Wallace-Hadrill 1988, 1994 and [most recently] 2009). See also (Zanker 1979, 1995, 2000; Leach 1988, 2004; Bergmann 1994). For the interpretation of the mythological imagery in Roman wall painting, the most comprehensive and far-reaching attempt to replace the paintings in the (social and ‘atmospheric’) context of the Roman house is (Lorenz 2008), with a short introduction on the respective history of scholarship on pp. 3–11, with more bibliography. |

| 6 | There is an extensive literature on Roman landscape painting, especially on the so-called sacro-idyllic genre. See, e.g., (Peters 1963; Silberberg 1980; Leach 1988, pp. 197–260; Kotsidu 1998, 2007; Mielsch 2001, pp. 179–92; Hinterhöller 2007a, 2007b; Hinterhöller-Klein 2015; Croisille 2010; Colpo 2010, especially pp. 167–79, and 2013; Dietrich 2017; La Rocca et al. 2009, pp. 53–54), provides an extensive further bibliography on Roman landscape painting. |

| 7 | Indeed, whereas scholarship on Roman wall painting in general has long begun to replace the decorated walls in the social context of the house and its owners (see note 6 here above), this does not necessarily hold true for the more specific topic of spatial depiction. Here, attempts to trace a general ‘history of perspective’ in the wake of the groundbreaking (Panofsky 1927, English translation: Panofsky 1991) through the (more or less ‘geometric’) analysis of perspectival vistas on the walls taken on their own are still produced quite regularly, and not necessarily with much attention paid to the social context and finalities of wall decoration. For attempts to reconstruct methods of perspective construction in Roman painting, see most recently the monograph (Hinterhöller-Klein 2015), or (Stinson 2011, pp. 406–8, with earlier bibliography on p. 403, note 2). |

| 8 | (Heinrich 2002, pp. 9–11). However, see already (Mau 1882, pp. 128–30), who noted the existence of such simple second-style decorations. Not having been illustrated in his groundbreaking book, these walls have largely missed out in subsequent studies on second-style wall decoration. |

| 9 | The wall decoration of the Casa di Cerere as depicted in (Heinrich 2002, pp. 78–83, cat. no. 10–17, Figures 15–38), provides an example of such standard second-style walls. Only the more lavishly decorated rooms make some use of the motif of projecting columns in the foreground, deemed paradigmatic of second-style wall decorations as a whole. |

| 10 | The scholarly literature on the Boscoreale Villa is far too large to be cited here. The most comprehensive and up-to-date presentation of the frescoes in their architectural context is currently (Barbet and Verbanck-Piérard 2013), vol. 1 with a thorough and well-illustrated room-by-room description of the Villa’s wall-paintings and with extremely useful reconstructions by F. Ory, incorporating the extant fragments of the frescoes in line drawings of the walls’ overall decorative designs (except Cubiculum M), vol. 2 with a collection of articles on the villa and its frescoes, making extensive use of digital reconstructions. The most recent overview is (Plantzos 2018, pp. 313–17). Issues of spatiality and framing relevant to the present argument are tackled by V. Platt in (Platt and Squire 2017, pp. 102–8). For the present aim of linking wall decoration, the architecture of the respective rooms, and their inhabitants, (Bergmann 2010), which presents the villa through a digital model that projects the frescoes back on the walls, is key. A more traditional account of perspectival painting in this villa is found in (Ehrhardt 1991, pp. 42–46). An extensive (though not complete) bibliography (especially on the frescoes of Cubiculum M) is to be found on the website of the Metropolitan Museum (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/247017, last viewed on 21 January 2019) For a useful virtual tour realized by the King’s Visualization Lab (King’s College London) in cooperation with the Metropolitan Museum and the eight other museums owning paintings from the Boscoreale Villa, see https://www.metmuseum.org/metmedia/video/collections/gr/boscoreale-model (last viewed on 21 January 2019); on this digital visualization, see (Beacham et al. 2013). |

| 11 | On the room and its frescoes, see (Barnabei 1901, pp. 47–60; Barbet and Verbanck-Piérard 2013, vol. I, pp. 52–63 [with further bibliography], with a restitution of the northern wall’s overall design on pl. 19a–b; Barbet and Verbanck-Piérard 2013, vol. II, pl. IX). |

| 12 | On the room and its frescoes, see (Barnabei 1901, pp. 63–66; Barbet and Verbanck-Piérard 2013, vol. I, 43–51 [with further bibliography], with a restitution of the southern wall’s overall design on pl. 17a–b; Barbet and Verbanck-Piérard 2013, vol. II, pl. VII). |

| 13 | New York, Metropolitan Museum, Rogers Fund, 1903 (03.14.13a–g); on the room and its frescoes, see (Barnabei 1901, pp. 72–81; Barbet and Verbanck-Piérard 2013, vol. I, 76–91 [with further bibliography]; Barbet and Verbanck-Piérard 2013, vol. II, pl. XV–XVIII). For further bibliography, see (Hinterhöller-Klein 2015, p. 230, note 669). |

| 14 | Paris, Louvre P 101 (MND 615) and P 102 (MND 616); on the room and its frescoes, see (Barnabei 1901, pp. 21–22; Barbet and Verbanck-Piérard 2013, vol. I, 22–24 [with further bibliography], with a restitution of the Eastern wall’s overall design on pl. 2a–b; Barbet and Verbanck-Piérard 2013, vol. II, pl. I). |

| 15 | See especially (Wallace-Hadrill 1994, pp. 38–61). |

| 16 | The prominence of devices closing the view in the middle zone of second-style walls has, of course, already been noted in scholarship, see, e.g., (Hiller 1988, especially p. 200). However, this structural (as I claim) characteristic of second-style decorations has been discussed as a transitional characteristic of earlier second style’s breaking through the wall not having yet fully reached its (teleological) end. See, e.g., (Ehrhardt 1991), who stresses the fact that earlier second-style walls (as those from the Villa dei Misteri) tend to be relatively more closed than later ones (as those from the Villa of Oplontis). He is perfectly right in noting that those deep spaces behind the shear walls are presented as being—in principle—accessible, see p. 47 (on Oplontis). However, it is precisely this accessibility that makes the closure all the more noteworthy. On shear walls in second style, see also (Borbein 1975). |

| 17 | For splendid photographs of the villa’s frescoes, see (Mazzoleni and Pappalardo 2005, pp. 102–24), for cubiculum 16, see pp. 104, 109–11. On the second-style perspectival vistas in Cubiculum 16 of the Villa dei Misteri, see (Ehrhardt 1991, pp. 37–42, with useful line drawings on pp. 36–37, Figures 1–2). On the effects of spatial illusion created by painted wall decoration in the Villa dei Misteri, see (Elsner 1995, pp. 62–71). |

| 18 | For splendid photographs of the villa’s frescoes, see (Mazzoleni and Pappalardo 2005, pp. 126–64), for oecus 15, see pp. 136–37. For a comprehensive study of the villa in its various aspects, see most recently (Gazda and Clarke 2016, making extensive use of digital reconstructions). On its second-style paintings, deemed to have been executed by the same workshop as the Boscoreale frescoes, see the contribution of Regina Gee in (Gazda and Clarke 2016, especially pp. 86–88); and (Gee forthcoming [on the villa’s frecoes]; Ehrhardt 1991, pp. 47–51 [focusing on its perspectival vistas]). For further bibliography, see (Hinterhöller-Klein 2015, p. 230, note 669). |

| 19 | See (Platt and Squire 2017). |

| 20 | On the perspectival vistas in this room, see (Ehrhardt 1991, pp. 37–42, Figures 1 and 2). On rooms with alcoves and their function within an ‘archaeology of intimacy’ amidst the houses’ social hierarchy, see (Anguissola 2010). |

| 21 | A very good analysis of the typical situations of social interaction of the dominus with his guests in the context of Pompeian domestic architecture and its mobile furniture (klinais, but also cathedrae) is provided in (Dickmann 1999, pp. 281–87, without special attention paid to wall painting). On alcove rooms as a setting for the more intimate interactions between people, see (Anguissola 2010). |

| 22 | (Muth 2007), to which this article owes much, makes a similar point concerning the astonishingly small role played by sculpture in the otherwise over-densely decorated late antique Villa of Piazza Armerina. In order not to overshadow the dominus’ appearance in front of his guests, the focal points of the Villa’s many apsidial rooms—where the dominus or other important people would have been seated—are precisely not taken by statues, even though such apses would otherwise constitute the perfect location for the setting of statuary. |

| 23 | Berlin, Antikensammlung Sk 921. On the type, see (Cain 1989; Di Franco 2017, pp. 23–37). |

| 24 | Paris, Louvre MA 1606. The first discussion of the type is (Hauser 1889, pp. 189–99). Extensive further bibliography is provided on the website of the British Museum (concerning the London replica of the same type [British Museum 1805,0703.123]). |

| 25 | Based on a notice in Vitruvius, the idea was first discussed in relation to extant Roman wall painting in (Beyen 1957, specifically on the Boscoreale Villa). Recent discussions, no more necessarily interested in the question of historic origin, include (Leach 2004, pp. 93–122; Gros 2008; Lorenz 2013, pp. 368–71). |

| 26 | The earliest occurrence of this phenomenon known to me is the dentil frieze framing the Alexander mosaic from the late second century BC Casa del Fauno. The illusionistic rows of small blocks depicted in oblique view suddenly change their left or right orientation in the center of each side of the frame (see, e.g., Andreae 1977, p. 76, Figure 25). As in later Roman perspectival wall painting, the mosaicist did not make any attempt to conceal this ‘mistake’. The same ‘mistake’ would probably have embarrassed an Italian Renaissance painter eager to master central perspective. Indeed, analogous problems with changing orientations in the center of a picture also occur in Late Medieval/Proto-Renaissance perspectival painting (typically with painted paved floors). Accordingly, the artists’ coping with such problems constitutes one of the crucial aspects in Panofsky’s famous account of the development of Renaissance perspective (Panofsky 1927 or 1991 [English translation]). |

| 27 | For bibliography on Roman landscape painting, see above note 7. |

| 28 | For a reconstruction of the wall’s overall decorative design, see (Andreae 1962), or more recently (Coarelli 1998, with further bibliography on the frescoes in note 1). A thorough presentation of the individual frescoes is Biering 1995. On the relationship of the Odyssey-frescoes and their frames, see (O’Sullivan 2007). |

| 29 | On the relationship of the wandering viewer in the corridor and the wandering Odysseus within the pictorial narrative, see the detailed study by (O’Sullivan 2007). |

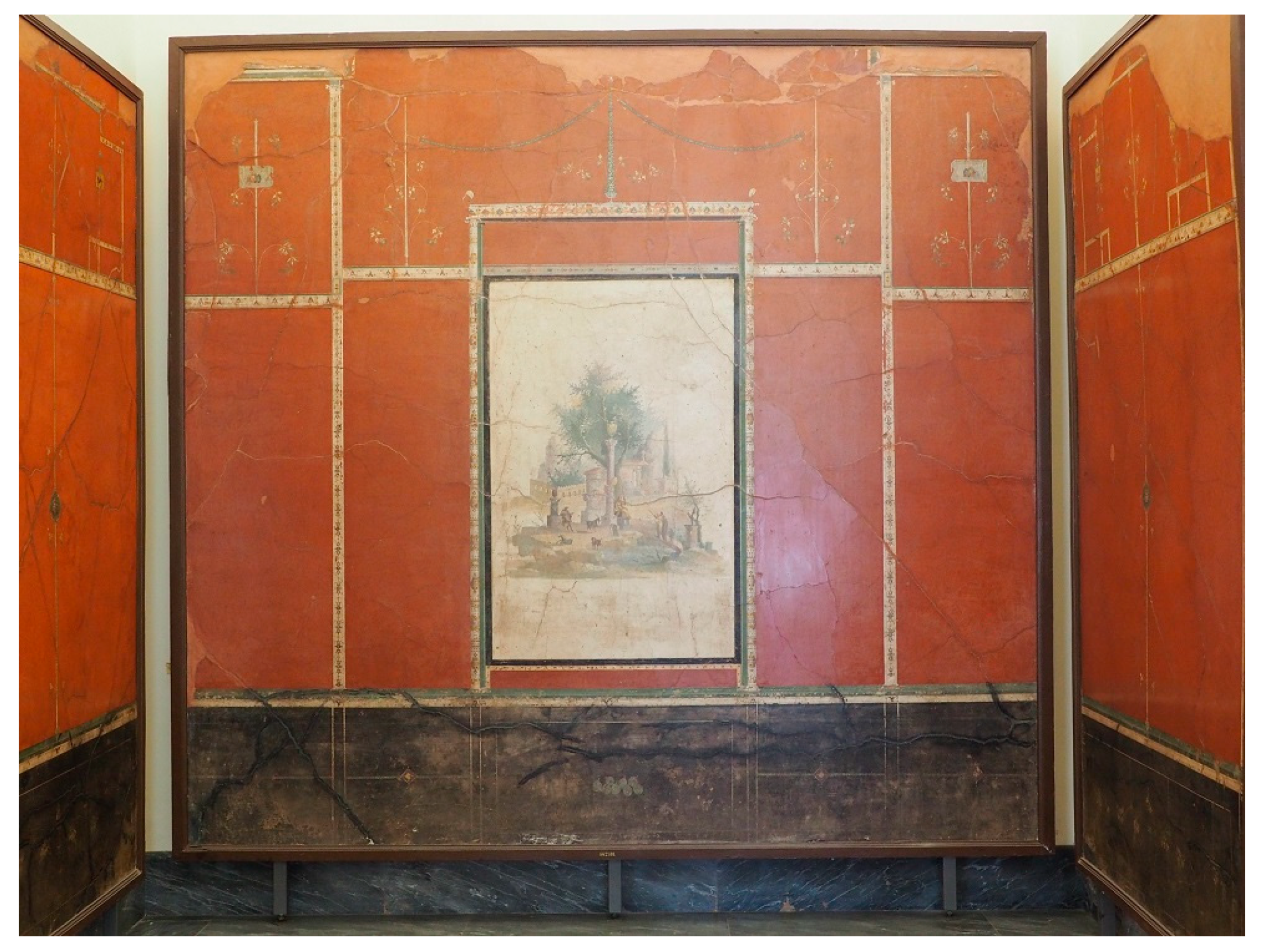

| 30 | On the house’s decoration, see PPP III, pp. 428–29; PPM IX.3.2, 128–39 (with bibliography until 1999 on p. 129); for photographs of the wall in its current state of preservation, see Figures 18–20 [I. Bragantini]. For a comprehensive overview of first-style walls in Pompei in their overall structure, see (Laidlaw 1985), on the ‘Officina of Ubonius’: pp. 285–89, with a drawing of the wall depicted here on p. 286 and pl. 85. |

| 31 | That the Pompeian first style has much older forerunners in the Greek East has long become consensual (Mielsch 2001, p. 22). On the differences between Roman first-style walls and their Greek forerunners (especially concerning the former’s high socles), see, e.g., (Ling 1991, p. 13): “The low plinth of the East is replaced by a high plain socle which pushes the orthostates up nearer to the middle of the wall”. See also (Barbet 2009, p. 25). A good example for a Greek plastered and painted wall comes from the ‘Maison des Comédiens’ in Delos from late second century BC (i.e., roughly contemporaneous with Pompeian first style walls): (Bruneau et al. 1970, p. 154, Figure 110), for an overview of the house’s architecture, see (Trümper 1998, pp. 202–5, cat. no. 18, with bibliography). |

| 32 | See, e.g., the fauces of the Casa del Fauno: (Mazzoleni and Pappalardo 2005, p. 56, with photograph showing plastic columns in the upper zone). |

| 33 | The most fundamental element in which this solution found in the first style shaped all future developments is perhaps the tripartite structure of the wall (high socle—orthostate/middle zone—upper zone), which is basically conserved in all subsequent styles. On this tripartite structure as a leading compositional principle in Roman wall painting of all subsequent styles, see (Ling 1991, p. 15): “[…] in moving higher on the wall, they [the orthostates] begin to assume more prominence in the design; the way is set for the threefold division of dado (socle), main zone (orthostates) and upper zone which is fundamental to the later styles”. See also, e.g., (Mielsch 2001, p. 9). |

| 34 | Casa die Grifi, Room II. For splendid colour photographs, see (Mazzoleni and Pappalardo 2005, pp. 65–76). For a short overview on the wall decoration, see, e.g., (Mielsch 2001, pp. 29–32). |

| 35 | For a general account of this second phase of the second style (usually dated to 40–20 BC), as defined by H. G. Beyen and since then largely accepted (Beyen 1938, 1960), see, e.g., (Ling 1991, pp. 31–42; Mielsch 2001, pp. 53–66; Barbet 2009, pp. 40–44). |

| 36 | Vitruvius 7.5.3–4. On this much discussed passage, see the analysis in (Grüner 2004, pp. 186–211, 233–63), and the remarks in (Platt 2009, pp. 53–56). The detailed archaeological commentary in (Tybout 1989, pp. 55–107) deals with the passage immediately preceding Vitruvius’ outburst against the ‘irrational’ new trends in wall painting of his own present time, namely an account of what used to be done in the past (and ought still to be done): Vitruvius 7.5.1–2. |

| 37 | For a general description of the third style, see, e.g., (Ling 1991, pp. 52–70; Mielsch 2001, pp. 67–78; Croisille 2005, pp. 68–80; Barbet 2009, pp. 96–178). |

| 38 | On the Villa of Boscotrecase and its wall painting, see (Della Corte 1922; Blanckenhagen and Alexander 1990; Anderson 1987–1988). For short overviews, see, e.g., (Mielsch 2001, pp. 70–73; Croisille 2005, pp. 77–80; Barbet 2009, pp. 109–10). See also (Dietrich 2017). |

| 39 | See (Mau 1882, p. 451): “Den zweiten und dritten Stil mögen wir als zwei aus ganz verschiedenen Geschmacksrichtungen hervorgegangene Decorationssyteme betrachten, welche, jedes in seiner Art hoch entwickelt, sich gleichberechtigt gegenüberstehen; die letzten pompejanischen Malereien sind der Beginn des Verfalls“. For a (less opinionated…) general description of fourth style, see, e.g., (Ling 1991, pp. 71–100; Mielsch 2001, pp. 79–92; Croisille 2005, pp. 81–102; Barbet 2009, pp. 179–273). |

| 40 | On the house’s decoration, see (PPP I, 212–219; PPM III.2.2, 42–108 [with bibliography until 1991 on p. 43; for more photographs of room f, see Figures 46–78] [M. de Vos]; Zanker 1995, pp. 150–62, with further bibliography in note 43; Platt 2002; Lorenz 2008, pp. 538–40, cat. no. K12; Knox 2015). We have to assume that a statuette standing in the wall’s central niche took the place of the mythological picture which we would otherwise have expected here. Those scholars who interpret this room as an Isis sacellum tend to reconstruct a statuette of Isis, see, e.g., (Tran Tam Tinh 1964, pp. 43–45). See (Platt 2002, pp. 104–7), for comments on the statuette’s three-dimensionality in relation to the house’s two-dimensional painted images. In any case, an interpretation of room f as a sacellum does not preclude its use for more intimate social gatherings too, see (Zanker 1995, pp. 155–56, comparing this sacellum with the Amaltheion in a villa of Cicero’s friend Atticus, with more similar examples in note 52). |

| 41 | This important remark has been made in (Lorenz 2013, p. 369). |

| 42 | |

| 43 | What to do, for example, with those large scale mythological or sacro-idyllic landscape typical of the transitional phase between second and third style, as we find them in the Houses of Augustus and of Livia on the Palatine? Being well centred both horizontally and vertically on the walls, and being large in size, they seem to concur strongly with the dominus’ own appearance. I currently do not have a good answer to this feature that does not fit well into the general model outlined here. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dietrich, N. Spatial Dimensions in Roman Wall Painting and the Interplay of Enclosing and Enclosed Space: A New Perspective on Second Style. Arts 2019, 8, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020068

Dietrich N. Spatial Dimensions in Roman Wall Painting and the Interplay of Enclosing and Enclosed Space: A New Perspective on Second Style. Arts. 2019; 8(2):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020068

Chicago/Turabian StyleDietrich, Nikolaus. 2019. "Spatial Dimensions in Roman Wall Painting and the Interplay of Enclosing and Enclosed Space: A New Perspective on Second Style" Arts 8, no. 2: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020068

APA StyleDietrich, N. (2019). Spatial Dimensions in Roman Wall Painting and the Interplay of Enclosing and Enclosed Space: A New Perspective on Second Style. Arts, 8(2), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020068