Ptolemaic Cavalrymen on Painted Alexandrian Funerary Monuments

Abstract

:1. Introduction

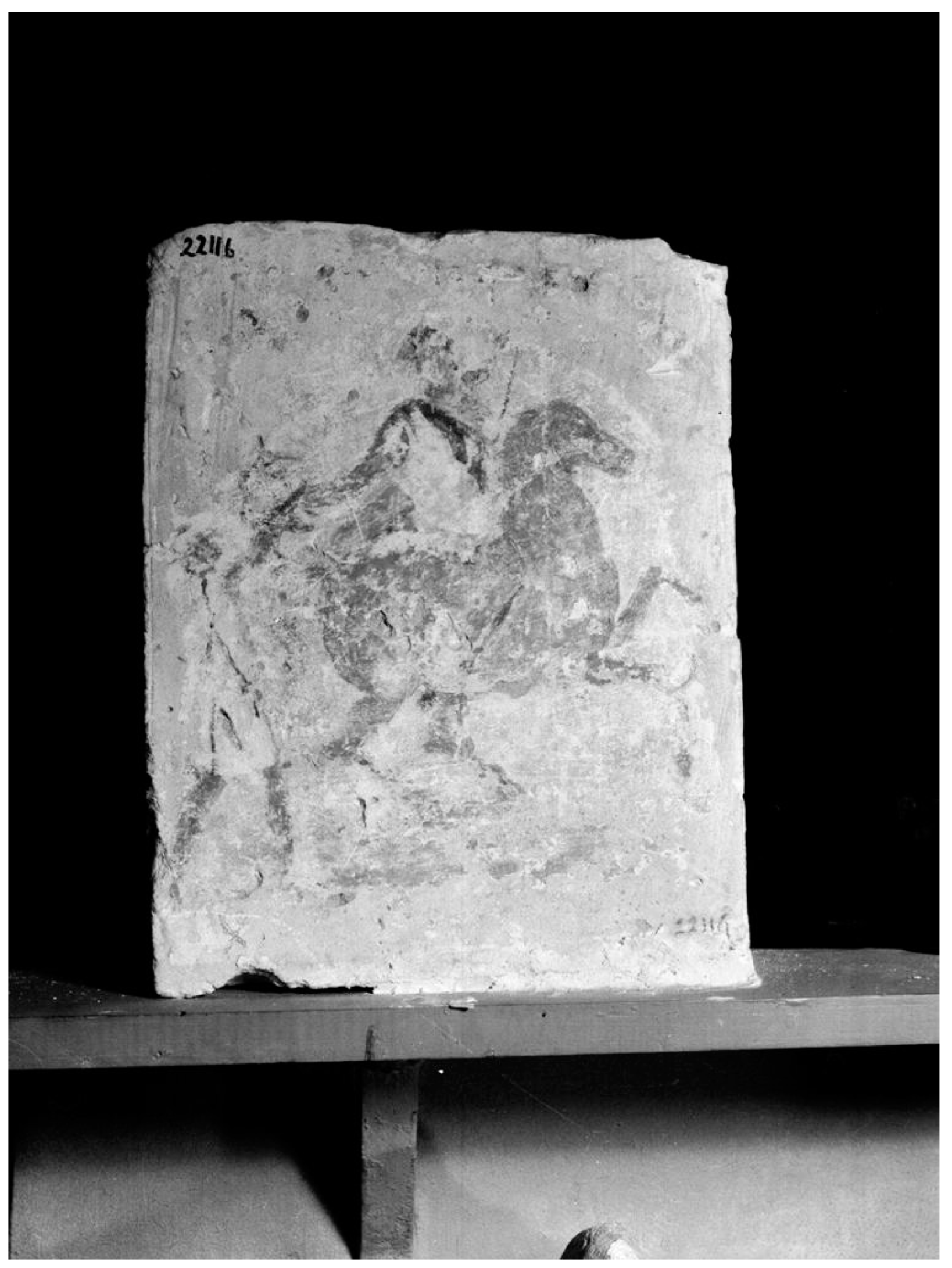

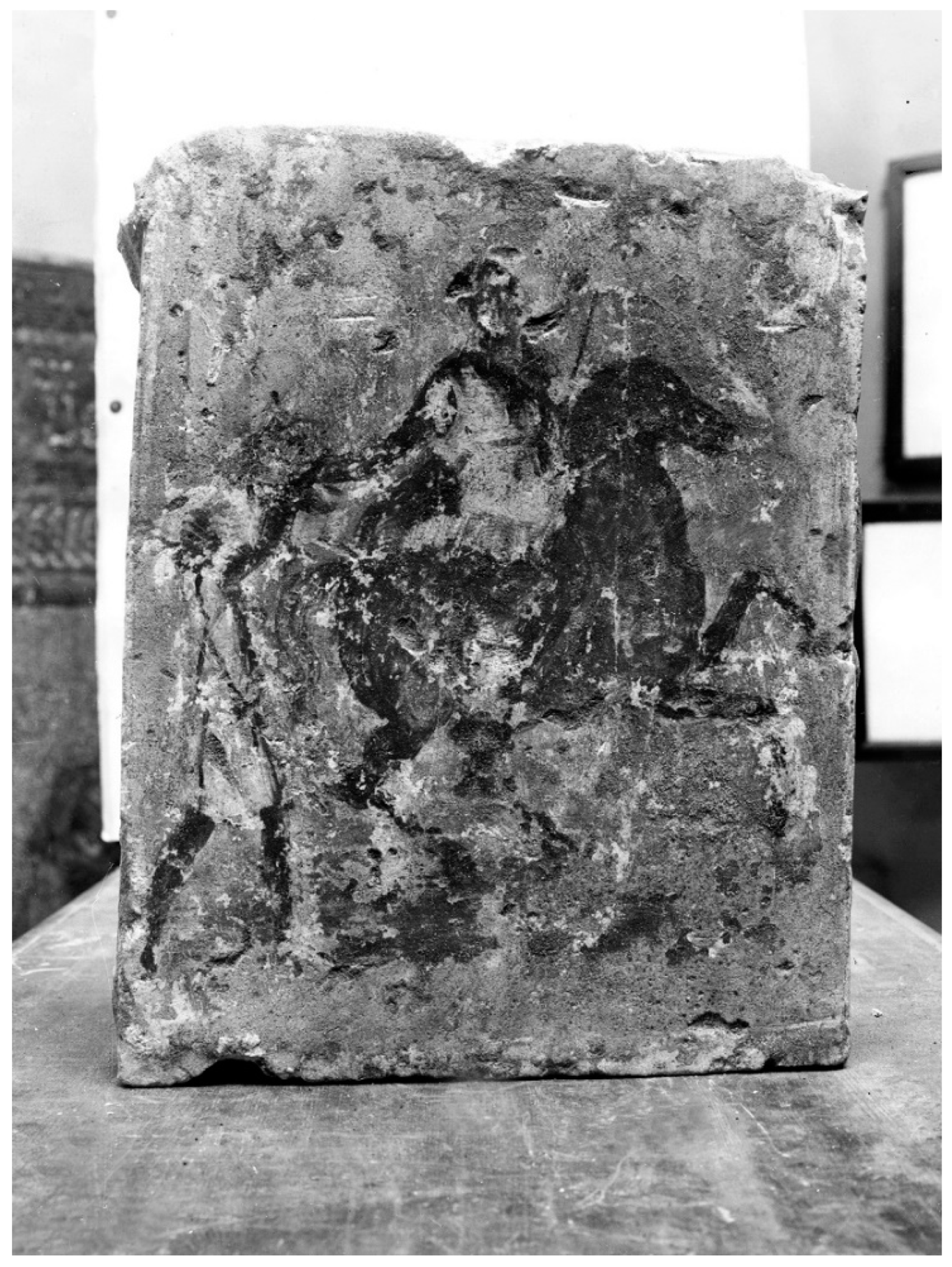

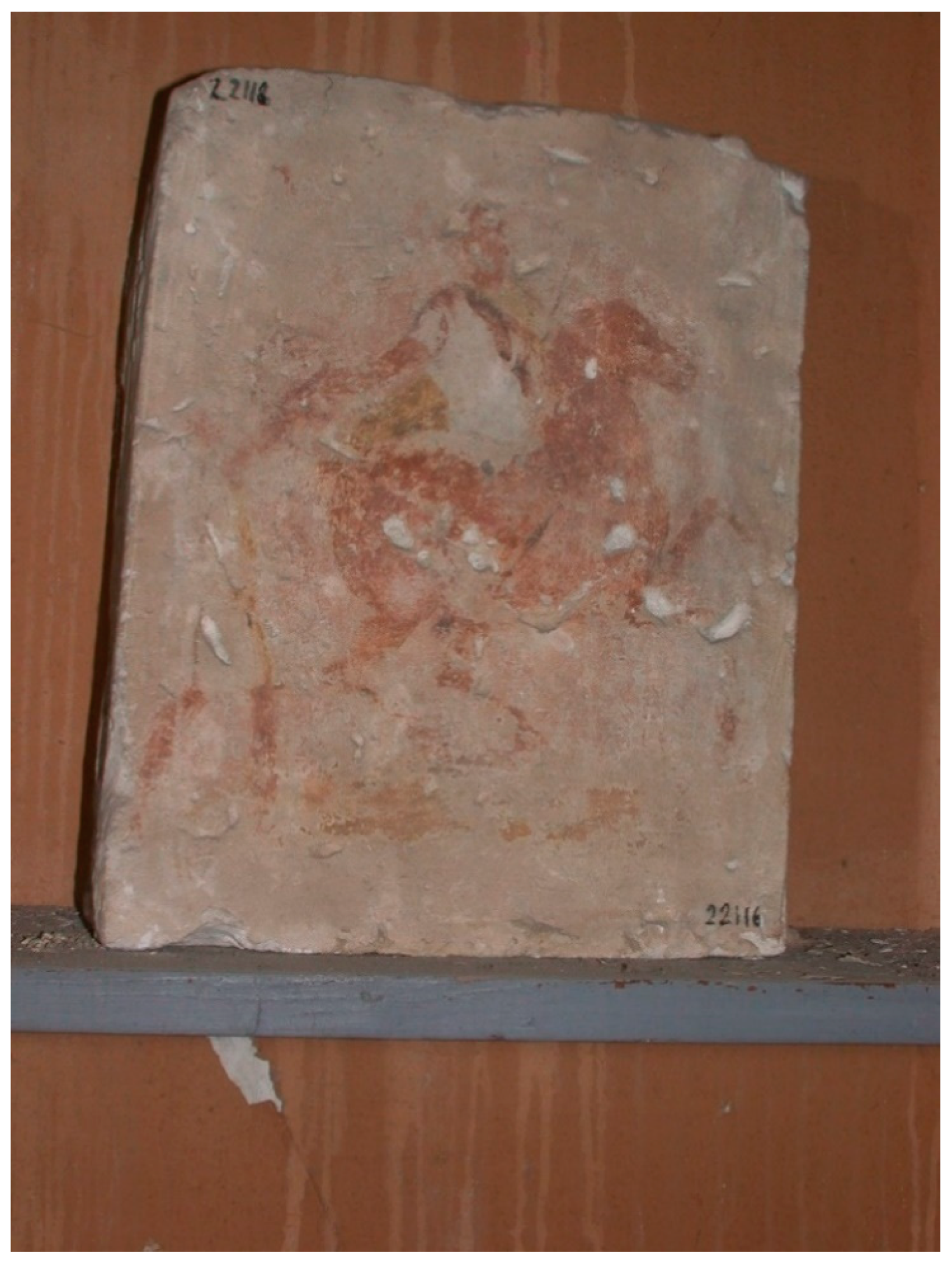

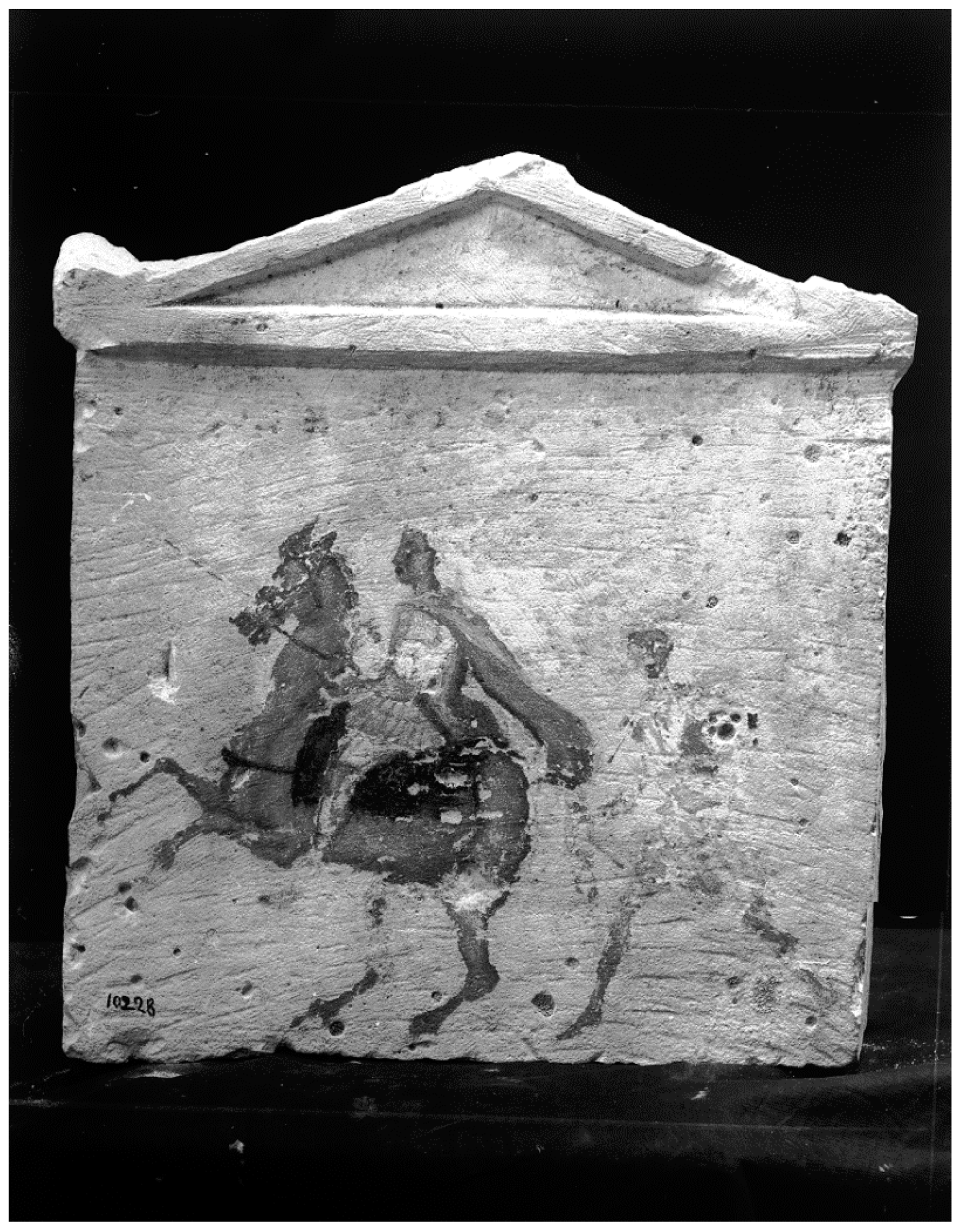

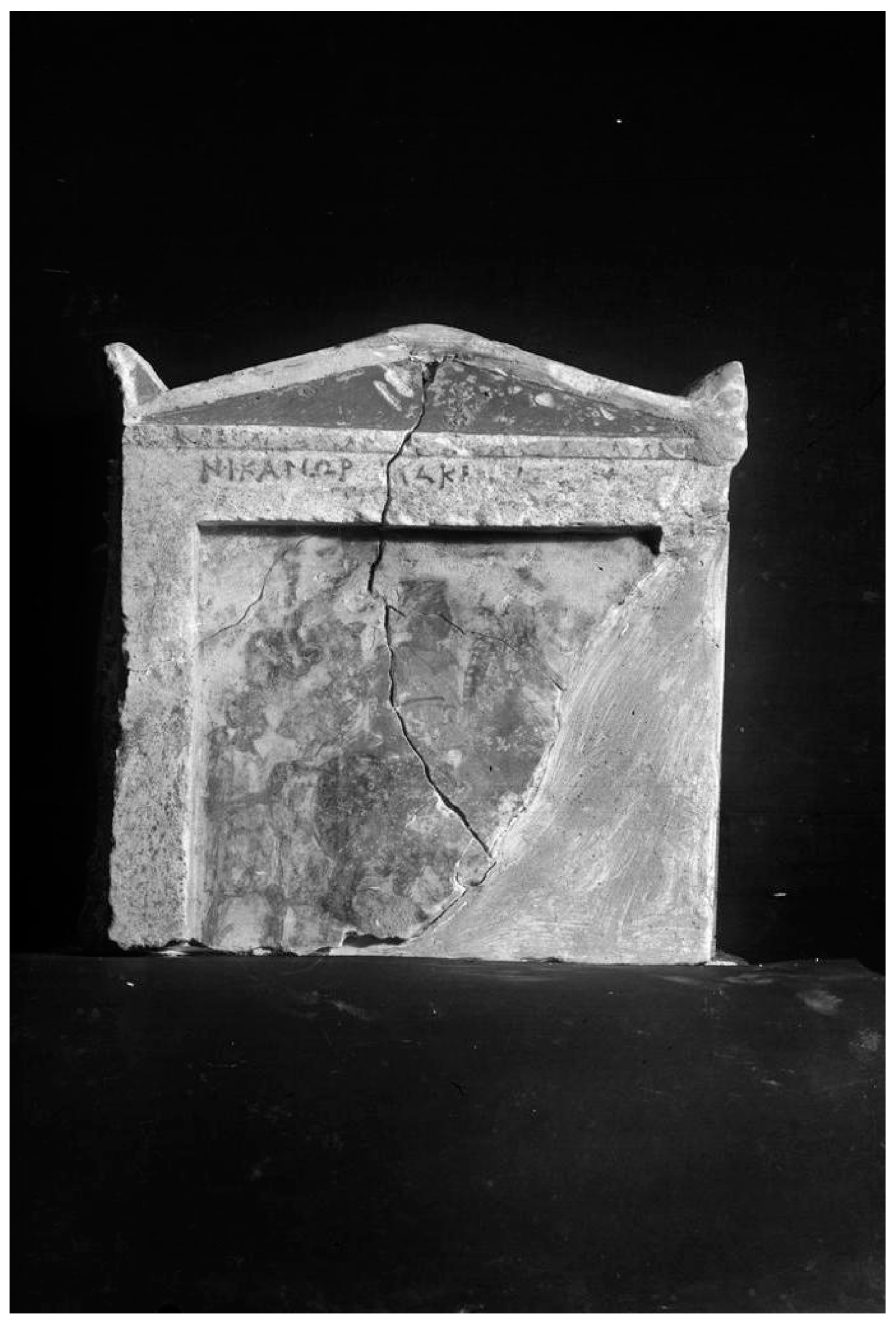

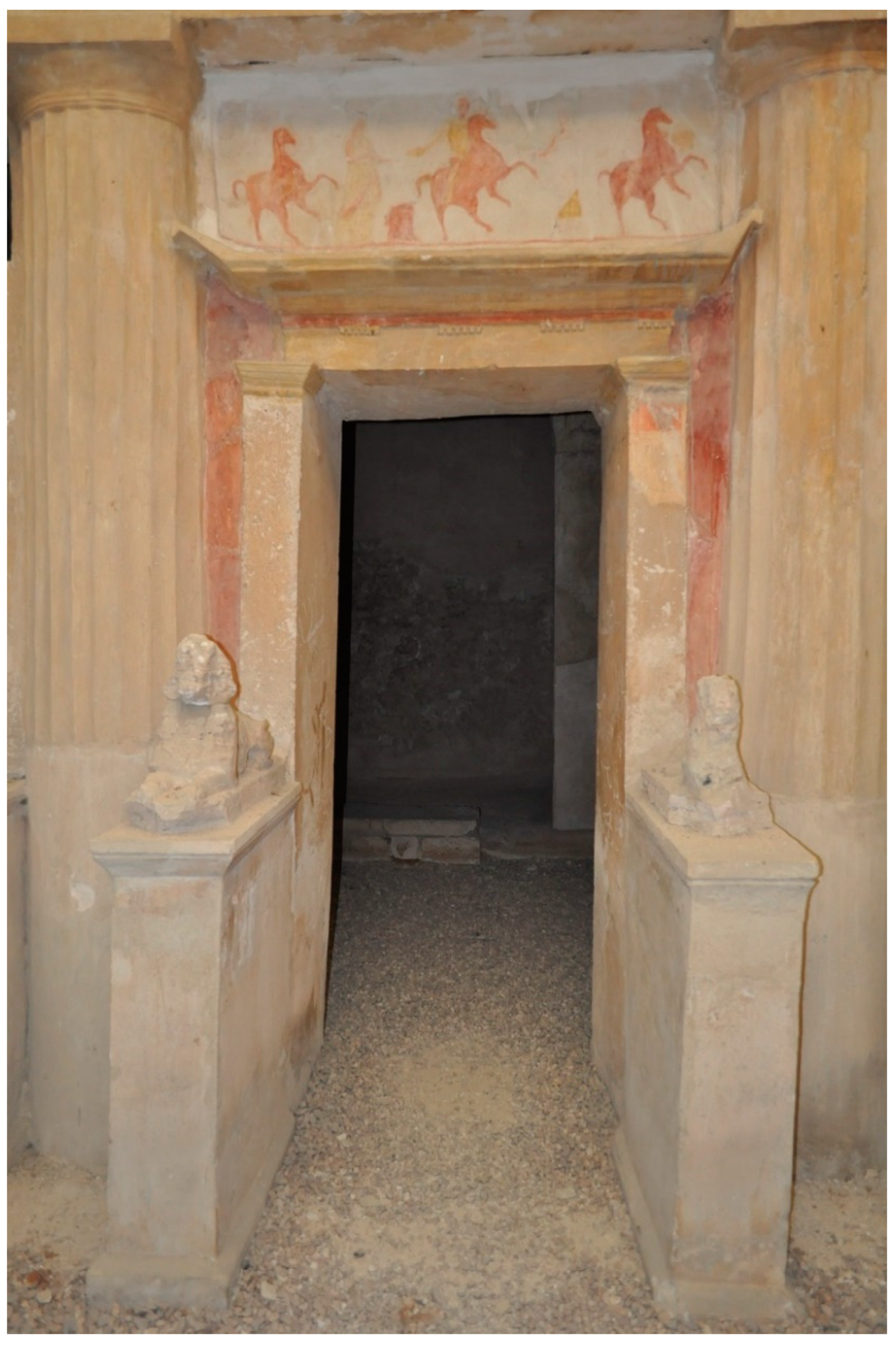

2. Catalogue of Painted Alexandrian Funerary Monuments Featuring Ptolemaic Cavalrymen

3. Northern Greek Comparanda

4. Early Alexandria and the Ptolemaic Cavalry

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| LIMC | Lexicon iconographicum mythologiae classicae |

References

- Abbe, Mark B. 2007. Painted Funerary Monuments from Hellenistic Alexandria. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Available online: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/pfmh/hd_pfmh.htm (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Adriani, Achille. 1936. Le Nécropole de Moustafa Pacha (Annuaire 2 [1933/34–1934/35]). Alexandria: Whitehead Morris. [Google Scholar]

- Adriani, Achille. 1952. Annuaire du Musée gréco-romaine III (1940–1950). Alexandria: Whitehead Morris Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Andrianou, Dimitra. 2017. Memories in Stone: Figures Grave Reliefs from Aegean Thrace. Athens: Ethniko Hidryma Ereunōn, Institouto Historikōn Ereunōn. [Google Scholar]

- Andronicos, Manolis. 1984. Vergina. The Royal Tombs and the Ancient City. Athens: Ekdotike Athenon S.A. [Google Scholar]

- Archibald, Z. H. 1998. The Odyrisan Kingdom of Thrace. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitopoulos, A. S. 1928. Graptai stēlai Dēmētriados-Pagason. Athens: P.D. Sakellarios. [Google Scholar]

- Badian, Ernst. 1999. A Note on the ‘Alexander Mosaic’. In The Eye Expanded: Life and Arts in Greco-Roman Antiquity. Edited by F. B. Titchener and R. F. Moorton Jr. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, John. 2004. Egyptian Elite Self-Presentation in the Context of Ptolemaic Rule. In Ancient Alexandria between Egypt and Greece. Edited by W. V. Harris and Giovanni Ruffini. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 33–61. [Google Scholar]

- Baumer, Lorenz, and Ursula Weber. 1991. Zum Fries des ‘Philippgrabes’ von Vergina. Hefte des Archäologischen Seminars der Universität Bern 14: 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bingen, Jean. 2007. Hellenistic Egypt: Monarchy, Society, Economy, Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boteva, Dilyana. 2011. The ‘Thracian Horseman’ Reconsidered. In Early Roman Thrace: New Evidence from Bulgaria. Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series Number Eighty-Two. Edited by Ian P. Haynes. Portsmouth: Journal of Roman Archaeology, pp. 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Breccia, Evaristo. 1905. La Necropoli di Sciatbi. Bulletin de la Société royale d’archéologie d’Alexandrie 8: 55–100. [Google Scholar]

- Breccia, Evaristo. 1912. La Necropoli di Sciabti. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Breccia, Evaristo. 1930. Nuovi scavi nelle Necropoli di Hadra. Bulletin de la Société archéologique d’Alexandrie 25: 99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Brecoulaki, Hariclia. 2006. La Peinture Funéraire de Macédoine: Emplois et Fonctions de la Couleur IVe-IIe s. av. J.-C. Athens: Centre de Recherches de l’antiquité Grecque et Romaine, Fondation Nationale de la Recherche Scientifique. [Google Scholar]

- Briant, Pierre. 1991. Chasses royales macédoinnes et chasses royales perses: le theme de la chasse au lion sur la chasse de Vergina. Dialogues d’histoire ancienne 17: 211–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Blanche R. 1957. Ptolemaic Paintings and Mosaics and the Alexandrian Style. Cambridge: Archaeological Institute of America. [Google Scholar]

- Burstein, Stanley M. 1985. The Hellenistic Age from the Battle of Ipsos to the Death of Kleopatra VII. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande-Kim, Roberta, ed. 2014. When the Greeks Ruled Egypt: from Alexander the Great to Cleopatra. New York: Institute for the Study o the Ancient World, Princeton: Distributed by Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cesarin, Giulia. 2016. Hunters on Horseback: New Version of the Macedonian Iconography in Ptolemaic Egypt. In Alexander the Great and the East: History, Art, Tradition. Edited by Krzystof Nawotka and Agnieszka Wojciechowska. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Ada. 2010. Art in the Era of Alexander the Great: Paradigms of Manhood and their Cultural Traditions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, Sara E. 2019. Cultural Manoeuvring in the Elite Tombs of Ptolemaic Egypt. In The Ancient Art of Transformation: Case Studies from Mediterranean Contexts. Edited by Renee M. Gondek and Carrie L. Sulosky Weaver. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 76–106. [Google Scholar]

- Comstock, Mary, and C. Vermeule. 1971. Greek, Etruscan and Roman Bronzes in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Greenwich: New York Graphic Society. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Brian. 1966. Inscribed Hadra Vases in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Papers of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, vol. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Coussement, Sandra. 2016. ‘Because I Am Greek’: Polyonymy as an Expression of Ethnicity in Ptolemaic Egypt. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrova, Nora. 2002. Inscriptions and Iconography in the Monuments of the Thracian Rider. Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 71: 209–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Empereur, J. Y., and M. D. Nenna, eds. 2001. Nécropolis 1. Cairo: IFAO. [Google Scholar]

- Empereur, J. Y., and M. D. Nenna, eds. 2003. Nécropolis 2. 2 vols. Cairo: IFAO. [Google Scholar]

- Erskine, Andrew. 2013. Founding Alexandria in the Alexandrian Imagination. In Belonging and Isolation in the Hellenistic World. Edited by Sheila L. Ager and Riemer A. Faber. Toronto, Buffalo and London: University of Toronto Press, pp. 169–83. [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius, Johanna. 1999. Die Hellenistischen Totenmahlreliefs: Grabrepräsentation und Wertvorstellungen in Ostgriechischen Städten. Munich: F. Pfeil. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Bovet, Christelle. 2011. Counting the Greeks in Egypt: Immigration in the first century of Ptolemaic rule. In Demography and the Graeco-Roman World: New Insights and Approaches. Edited by Claire Holleran and April Pudsey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 135–54. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Bovet, Christelle. 2014. Army and Society in Ptolemaic Egypt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Franks, Hallie M. 2012. Hunters, Heroes, Kings: The Frieze of Tomb II at Vergina. Princeton: American School of Classical Studies at Athens. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, P. M. 1977. Rhodian Funerary Monuments. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fredricksmeyer, E. A. 1986. Alexander the Great and the Macedonian Kausia. Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974–2014) 116: 215–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudriaan, Koen. 1992. Ethnical Strategies in Graeco-Roman Egypt. In Ethnicity in Hellenistic Egypt. Edited by Per Bilde, Troels Engberg-Pedersen, Lise Hannestad and Jan Zahle. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, pp. 74–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Fekri, ed. 2002. Alexandria Graeco-Roman Museum: A Thematic Guide. Egypt: National Center for Documentation of Cultural and Natural Heritage and the Supreme Council of Antiquities. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzopoulos, Miltiades B. 2016. The Burial of the Dead (at Vergina) or the Unending Controversy on the Identity of the Occupants of Tomb II. Tekmeria 9: 91–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzopoulos, Miltiades B., and Pierre Juhel. 2009. Four Hellenistic Funerary Stelae from Gephyra, Macedonia. American Journal of Archaeology 113: 423–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinge, George, and Jens A. Krasilnikoff, eds. 2009. Alexandria: A Cultural and Religious Melting Pot. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hölbl, G. 2000. History of the Ptolemaic Empire. Translated by T. Saavedra. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Dennis D. 1999. Hero Cult, Heroic Honors, Heroic Dead: Some Developments in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods. In Ancient Greek Hero Cult: Proceedings of the Fifth International Seminar on Ancient Greek Cult, Organized by the Department of Classical Archaeology and Ancient History, Göteborg University, 21–23 April 1995. Edited by Robin Hägg. Stockholm: Svenska Institutet i Athen, Jonsered: Distributor P. Åström, pp. 167–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaitzi, Myrina. 2016. Figured Tombstones from Macedonia, Fifth—First Century BC. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kinch, Karl Frederik. 1920. Le tombeau de Niausta. Tombeau Macédonien. Mémoires de l’Académie Royale des Sciences et des Lettres de Danemark, Copenhague, 7me Série, Section des Lettres 4: 283–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kitov, Georgi. 2001. A Newly Found Thracian Tomb with Frescoes. Archaeologia Bulgarica 5: 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kitov, Georgi. 2009. Alexandrovskata Grobnitsa. Varna. [Google Scholar]

- La’da, Csaba A. 2002. Foreign Ethnics in Hellenistic Egypt. Leuven and Dudley: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- La’da, Csaba A. 2003. Encounters with Ancient Egypt: The Hellenistic Greek Experience. In Ancient Perspectives on Egypt. Edited by Roger Matthews and Cornelia Roemer. London: UCL, pp. 157–69. [Google Scholar]

- Landvatter, Thomas. 2018. Identity and Cross-cultural Interaction in Early Ptolemaic Alexandria: Cremation in Context. In Ptolemy I and the Transformation of Egypt, 404–282 BCE. Edited by Paul McKechnie and Jennifer A. Cromwell. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 199–234. [Google Scholar]

- Launey, Marcel. 1949–1950. Recherches sur les Armées Hellénistiques. Paris: E. de Boccard. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, Alan B. 2002. The Egyptian Elite in the Early Ptolemaic Period: Some Hieroglyphic Evidence. In The Hellenistic World: New Perspectives. Edited by Daniel Ogden. London: The Classical Press of Wales and Duckworth, pp. 117–36. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S. Rebecca. 2017. The Art of Contact: Comparative Approaches to Greek and Phoenician Art. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, Jean-Luc, Alexandre Baralis, Néguine Mathieux, Totko Stoyanov, and Milena Tonkova, eds. 2015. L’épopée des rois Thraces: Des Guerres Médiques aux Invasions Celtes, 479–278 av. J.-C.: Découvertes Archéologiques en Bulgarie. Paris: Musée du Louvre. [Google Scholar]

- McKechnie, Paul, and Jennifer A. Cromwell, eds. 2018. Ptolemy I and the Transformation of Egypt, 404–282 BCE. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, Judith. 2007. The Architecture of Alexandria and Egypt 300 BC—AD 700. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, Augustus C. 1885. Inscribed Sepulchral Vases from Alexandria. American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts 1: 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, Augustus C. 1887. Painted Sepulchral Stelai from Alexandria. American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts 3: 261–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikov, Vasil. 1954. Le Tombeau Antique près de Kazanlăk. Sofia: Académie Bulgare des Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Stella G. 1993. The Tomb of Lyson and Kallikles: A Painted Macedonian Tomb. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Stella G. 2014. Hellenistic Painting in the Eastern Mediterranean, Mid-Fourth to Mid-First Century BC. In The Cambridge History of Painting in the Classical World. Edited by J. J. Pollitt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 170–237. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, Paolo. 2004. Alessandro Magno. Immagini Come Storia. Rome: Istituto poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, Libreria dello Stato. [Google Scholar]

- Nachtergael, Georges. 1996. Trois dédicaces au dieu Hèrôn. Chronique d’Égypte 71: 129–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenna, Marie-Dominique, and Merwatte Seif el-Din. 2000. La vaiselle en Faïebce d’époque gréco-Romain. Catalogue du Musée gréco-Romain d’Alexandrie. Cairo: IFAO. [Google Scholar]

- Néroutsos-Bey, Dr. 1887. Inscriptions grecques et latines recueillies dans la ville d’Alexandrie et aux environs. Revue Archéologique 9: 291–98. [Google Scholar]

- Özgüç, Tahsin. 1971. Kültepe and Its Vicinity in the Iron Age. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kunumu Basimevi. [Google Scholar]

- Pagenstecher, Rudolf. 1919. Nekropolis: Untersuchungen über Gestalt und Entwicklung der alexandrinischen Grabanlagen und ihrer Malereien. Leipzig: Giesecke & Devrient. [Google Scholar]

- Palagia, Olga. 2000. Hephaestion’s Pyre and the Royal Hunt of Alexander. In Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction. Edited by A. B. Bosworth and E. J. Baynham. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 167–206. [Google Scholar]

- Pfuhl, Ernst, and Hans Möbius. 1977–1979. Die ostgriechischen Grabreliefs. Mainz am Rhein: Von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Picón, Carlos A. 2007. Art of the Classical World in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Greece, Cyprus, Etruria, Rome. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Plantzos, Dimitris. 2018. The Art of Painting in Ancient Greece. Atlanta: Lockwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Posamentir, Richard. 2011. The Polychrome Grave Stelai from the Early Hellenistic Necropolis. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reinach, S. 1888. Review of Neroutsos. L’Ancienne Alexandrie. Revue critique d’histoire et de littérature 26: 420. [Google Scholar]

- Reinach, Adolphe. 1911. Les Galates dans l’art alexandrine. Monuments et mémoires de la Fondation Eugène Piot 18: 37–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, Gisela M. A. 1927. Handbook of the Classical Collection. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, Gisela M. A. 1953. Handbook of the Greek Collection. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rostovtzeff, M. I. 1941. The Social and Economic History of the Hellenistic World. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rotroff, Susan I. 1982. Hellenistic Pottery: Athenian and Imported Moldmade Bowls. Princeton: American School of Classical Studies at Athens. [Google Scholar]

- Rouveret, Agnès. 2004. Peintures Grecques Antiques: La Collection Hellénistique du Musée du Louvre. Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard and Musée du Louvre. [Google Scholar]

- Saatsoglou-Paliadeli, Chryssoula. 1993. Aspects of Ancient Macedonian Costume. The Journal of Hellenic Studies 113: 122–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatsoglou-Paliadeli, Chryssoula. 2004. Βεργίνα. O τάφος του Φιλίππου. H τοιχογραφία του κυνηγιού. Athens. [Google Scholar]

- Saatsoglou-Paliadeli, Chryssoula. 2006. Reflections on the Painting Technique on Philip’s Tomb at Vergina. In Maiandros. Festschrift für Volkmar von Graeve. Edited by R. Biering, V. Brinkmann, U. Schlotzhauer and B. F. Weber. Munich: Biering & Brinkmann, pp. 213–20. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Stefan. 2010. Nekropolis—Grabarchitektur und Gesellschaft im hellenistischen Alexandreia. In Alexandreia und das Ptolemäische Ägypten: Kulturbegegnungen in Hellenisticher Zeit. Edited by Gregor Weber. Berlin: Verlag Antike, pp. 136–55. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, P., and Alain Schnapp. 1982. Image et société en Grèce ancienne: les representations de la chasse et du banquet. Revue Archéologique, Nouvelle Série 1: 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzmaier, Agnes. 1997. Griechische Klappspiegel: Untersuchungen zu Typologie und Stil. Berlin: W. de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Spier, Jeffrey, Timothy Potts, and Sara E. Cole, eds. 2018. Beyond the Nile: Egypt and the Classical World. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Stanwick, Paul Edmund. 2002. Portraits of the Ptolemies: Greek Kings as Egyptian Pharaohs. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swindler, Mary Hamilton. 1929. Ancient Painting, from the Earliest Times to the Period of Christian Art. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Dorothy Burr. 1963. The Terracotta Figurines of the Hellenistic Period. Princeton: Published for the University of Cincinnati by Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thonemann, Peter. 2015. The Hellenistic World: Using Coins as Sources. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tonkova, Milena. 2011. Les parures d’harnachement en or de Thrace et l’orfevrerie de la haute époque hellénistique. Bolletino di Archeologia on line (Numero special dedicato al Congresso di archeologia, A.I.A.C., 2008), 44–63. [Google Scholar]

- Török, László. 1995. Hellenistic and Roman Terracottas from Egypt. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider. [Google Scholar]

- Tripodi, Bruno. 1998. Cacce reali macedoni. Tra Alessandro I e Filippo V. Messina: Di.Sc.A.M. [Google Scholar]

- Velkov, Velizar, and Alexandre Fol. 1977. Les Thraces en égypte Gréco-Romaine. Sofia: Academia Litterarum Bulgarica, Institutum Thracicum. [Google Scholar]

- Venedikov, I. 1986. Koj e pogreban v Kazanlskata grobnitsa. Izkustvo 8: 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Venit, Marjorie Susan. 2002. The Monumental Tombs of Ancient Alexandria: The Theater of the Dead. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Venit, Marjorie Susan. 2009. Theatrical Fiction and Visual Bilingualism in the Monumental Tombs of Ptolemaic Alexandria. In Alexandria: A Cultural and Religious Melting Pot. Edited by George Hinge and Jens A. Krasilnikoff. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, pp. 42–65. [Google Scholar]

- Venit, Marjorie Susan. 2016. Visualizing the Afterlife in the Tombs of Graeco-Roman Egypt. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeule, Emily. 1979. Aspects of Death in Early Greek Art and Poetry. Berkeley and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Versluys, Miguel John. 2010. Understanding Egypt in Egypt and Beyond. In Isis on the Nile. Egyptian Gods in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt. Edited by Laurent Bricault and Miguel John Versluys. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 7–36. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Susan, and Peter Higgs, eds. 2001. Cleopatra of Egypt: From History to Myth. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wartenberg, Ute. Forthcoming. Early Portraits of Alexander the Great: The Numismatic Evidence.

- Webber, Christopher. 2003. Odrysian Cavalry Arms, Equipment, and Tactics. In Early Symbolic Systems for Communication in Southeast Europe. Edited by Lolita Nikolova. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 529–54. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Gregor, ed. 2010. Alexandria und das Ptolemäische Ägypten: Kulturbegegnungen in Hellenistischer Zeit. Berlin: Verlag Antike. [Google Scholar]

- Westgate, Ruth. 2011. Party Animals: The Imagery of Status, Power and Masculinity in Greek Mosaics. In Sociable Man: Essays on Ancient Greek Social Behaviour in Honour of Nick Fisher. Edited by S. D. Lambert. Swansea: Classical Press of Wales, pp. 291–322. [Google Scholar]

- Wypustek, Andrzej. 2013. Images of Eternal Beauty in Funerary Verse Inscriptions of the Hellenistic and Greco-Roman Periods. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Zvkova, Lyudmila. 1974. Kazanlskata grobnitsa. Sofia. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | For an overview of the Ptolemaic cavalry, see (Fischer-Bovet 2014, pp. 125–33). |

| 2 | See (Venit 2009) on the use of “bilingual visual vocabulary” and theatricality related to funerary rituals in Alexandrian tombs. |

| 3 | |

| 4 | For Hellenistic funerary stelae, see, e.g., (Fabricius 1999; Fraser 1977; Pfuhl and Möbius 1977–1979). |

| 5 | I erroneously stated that the slab came from the Soldiers’ Tomb (Cole 2019, p. 88). |

| 6 | Metropolitan Museum of Art 04.17.4 and 04.17.6: (Casagrande-Kim 2014, p. 104, cat. 121 and 122); Metropolitan Museum of Art 04.17.5: (Plantzos 2018, pp. 259–61, Figure 251). |

| 7 | Suggested by (Brown 1957, p. 28). |

| 8 | On these elements of Macedonian costume, see (Saatsoglou-Paliadeli 1993; Fredricksmeyer 1986). |

| 9 | Schmitt and Schnapp (1982) discuss the link between the hunt and the symposium in Archaic Greek vase painting, and Vermeule (1979) considers the poetic and artistic themes of hunt, war, and rape/abduction as they relate to death in the Greek imagination. |

| 10 | On the Thracian cavalry, see (Webber 2003). |

| 11 | A wide variety of interpretations of the identity and significance of the Thracian Rider have been put forward. See (Andrianou 2017, pp. 110–25) for an overview; and (Boteva 2011, p. 86, note 12) for relevant bibliography. See also LIMC VI.1. (1992), s.v. “Heros Equitans”, 1019–1081 (A. Cermanović-Kuzmanović et al.). In addition to being shown as a hunter, the Thracian Rider also appears astride a walking horse approaching a snake-entwined tree. The votive and funerary stelae are so similar in their use of these two motifs that their function is often only ascertainable by their inscriptions. |

| 12 | On the heroized dead as a warrior or hunter on horseback, see (Wypustek 2013, pp. 65–66). |

| 13 | It is worth noting that hunt and battle scenes appear frequently in Greek mosaics, a medium that was closely related to painting. Westgate (2011) examines this theme in mosaics as representative of Greek masculinity, particularly in Hellenistic Macedonia. Greek pebble mosaics were adopted in Alexandria: a stag hunt mosaic found in the palace quarter (McKenzie 2007, p. 68 Figure 98) resembles a stag hunt mosaic from the House of the Abduction of Hades in Pella (Franks 2012, p. 63, Figure 47; Cohen 2010, pl. I) and a lion hunt mosaic from the House of Dionysus at Pella (Franks 2012, p. 62, Figure 46; Cohen 2010, p. 67, Figure 21, pl. IV). In a partially preserved Alexandrian mosaic, a nude warrior brandishes a spear and shield (Cohen 2010, pp. 133–34, Figure 61). |

| 14 | Warriors with their weapons also appear on painted Alexandrian funerary monuments, but the present discussion is focused specifically on the mounted rider motif. Isolated weapons, without human figures, appear on early Hellenistic painted stelae from the Tower of Zeno in the Chersonese, for which, see (Posamentir 2011). The painted lunettes in the burial chamber of the Tomb of Lyson and Kallikles at Lefkadia depict military gear but do not include images of the deceased individuals: see (Miller 1993). The so-called Ghirghis tomb at Alexandria includes a kline chamber in which an Egyptian naiskos is carved in relief, surrounded by relief images of Greek arms and armor; the deceased evidently adhered to Egyptian funerary religion but also wished to signal his elite status as a member of the Ptolemaic military: see (Venit 2002, pp. 92–93, Figure 76). |

| 15 | For a summary of painted military and hunting imagery in Hellenistic tombs, see (Miller 2014, pp. 185–97). |

| 16 | See examples in (Kalaitzi 2016; Posamentir 2011; Brecoulaki 2006; Rouveret 2004; Arvanitopoulos 1928). |

| 17 | (Hatzopoulos and Juhel 2009, cat. 4, Figures 8–10). Kilkis Archaeological Museum, inv. no. 2315. |

| 18 | See examples in (Kalaitzi 2016). |

| 19 | (Andrianou 2017, pp. 123–24, 212, and 349, Relief 27, 213–14 and 352–55, Relief 29, 214–15 and 356–57, Relief 30). Note that these examples date to the late Hellenistic–early Roman period. |

| 20 | The tomb was discovered by Manolis Andronicos in 1977: see (Andronicos 1984). On the ongoing debate about the identity of the cremated man and woman buried within the tomb, who are thought to be either Philip II and his wife Kleopatra or Philip III Arrhidaios and Euridike, see (Hatzopoulos 2016). |

| 21 | E.g., (Hatzopoulos 2016, pp. 114–15; Saatsoglou-Paliadeli 2004, pp. 165–69; Andronicos 1984, pp. 115–17, 230). Tripodi (1998, pp. 106–9) argues that they are instead Alexander IV and Philip III Arrhidaos, while Baumer and Weber (1991, pp. 38–41), followed by Badian (1999, pp. 87–88), identify them as Philip III Arrhidaios and Philip II. Palagia (2000, pp. 195–97) suggests Philip Arrhidaos and Alexander. |

| 22 | Plutarch, Alex 40.4–5; Arrian, Anabasis 4.13.2; Curtius History of Alexander 8.1.13–17, 8.6.7. |

| 23 | |

| 24 | Xenophon, Cynegeticus 1.18; 12.1–9. Strabo Geographica 10.4.21 also reports that on Crete, youths were prepared for battle by hunting. |

| 25 | Arrian, Anabasis 4.13.1. Arrian also reports that the Macedonian king hunted on horseback as the Persians did. |

| 26 | Athenaeus, Deipnosophists, I, 18A. |

| 27 | See e.g., (Palagia 2000). |

| 28 | (Franks 2012, pp. 48–52; Cohen 2010, pp. 82–93). Coinage of the Thracian Bisalti dating to ca. 500 BC depict horsemen (see Franks 2012, p. 44, Figures 31 and 32) and may even have influenced the adoption of this motif on Macedonian regal coinage. |

| 29 | See especially (Franks 2012; Cohen 2010, pp. 237–97). |

| 30 | (Saatsoglou-Paliadeli 2006, p. 215; Saatsoglou-Paliadeli 2004, pp. 33–34; Andronicos 1984, p. 113). On materials and techniques, see also (Brecoulaki 2006, pp. 119–29). |

| 31 | Kitov (2009, pp. 29–30) believes this is a woman. |

| 32 | For Thracian metalwork, including horse trappings, see (Tonkova 2011). |

| 33 | Similarly, a sarcophagus found at Çan (early 4th century BC) and the Alexander Sarcophagus from Sidon (late 4th century BC) both juxtapose hunts on horseback with scenes of warfare in which the main protagonists are mounted riders: see (Cohen 2010, pp. 119–27). For scenes of hunters on horseback from Greek-style Phoenician sarcophagi of the 5th–4th century BC, see (Franks 2012, pp. 32–35, Figures 20–25; Palagia 2000, pp. 178–179, Figures 2–7). |

| 34 | Moreno (2004, p. 220) interprets the figure on foot as the rider’s attendant, but it is apparent that the rider aims his weapon at this man, who raises his shield and bends his knees in a defensive posture. The shield he holds is of a Macedonian type, but Cohen (2010, p. 142) explains this object as having been discarded by a fallen soldier and picked up by the enemy. |

| 35 | Palagia (2000, pp. 200–1) asks whether the rider might be Alexander himself. |

| 36 | (Brecoulaki 2006, p. 220). See also a drawing of a now-lost painting from a late 4th-century BC tomb at Dion in Macedonia that depicts an equestrian battle between Greeks and Persians: (Cohen 2010, pp. 136–37, Figure 63; Brecoulaki 2006, pp. 249–51). |

| 37 | (Mikov 1954, pp. 8–10, 15–17, pl. III–V, XXV–XXVI). For digital reconstructions of the paintings, see (Webber 2003, p. 546, Figure 12d, 12e). |

| 38 | (Zvkova 1974, p. 18). For details of the possible Seuthes figure, see (Webber 2003, p. 545, Figure 12c). |

| 39 | Pliny, Natural History, 35.138. |

| 40 | |

| 41 | For recent summaries of this issue, see (Landvatter 2018, pp. 199–202; Fischer-Bovet 2014, pp. 4–6) with a focus on the Ptolemaic army. See (Lloyd 2002) on Egyptian elites in the early Ptolemaic period. |

| 42 | See (Martin 2017), who challenges traditional definitions of “Greek” and “Phoenician”, as well as ingrained notions about artistic style as a reflection of ethnicity, in the study of classical art history. |

| 43 | |

| 44 | There is evidence that elite individuals in Ptolemaic Egypt were sometimes depicted in portrait sculptures that showed them in both Greek and Egyptian styles, just as Ptolemaic rulers did (for which see Stanwick 2002). The Callimachos Decree from Thebes orders three statues of the strategos Callimachos, two to be made in hard stone and one in bronze; these materials likely equate to Egyptian and Greek styles, respectively: see Poole in (Spier et al. 2018, pp. 170–71, cat. 102; Burstein 1985, pp. 144–46, no. 111). |

| 45 | See most recently (Coussement 2016). |

| 46 | (Bingen 2007, pp. 83–93). On Thracians in Ptolemaic Egypt, see also (Goudriaan 1992, pp. 77–79; Velkov and Fol 1977), though I agree with Bingen that Velkov and Fol are incorrect in their conclusion that the Thracians occupied a low social standing under the Ptolemies. |

| 47 | Diodorus 18.4.3–4. |

| 48 | Polybius, Histories, 5.79.2. |

| 49 | Polybius, Histories, 5.63.11–12. |

| 50 | (Fischer-Bovet 2014, p. 132); on Egyptians in the Ptolemaic army, see (Fischer-Bovet 2014, pp. 161–66). |

| 51 | Landvatter (2018) similarly argues that the use of cremation in the burials of the Shatby cemetery was meant as a rejection of Egyptian funerary practices and an assertion of non-Egyptian identity in the early Ptolemaic period. |

| 52 | Images of horsemen were in use on Macedonian coinage long before the Hellenistic period: Alexander I (r. 498–454 BC), the first Macedonian king to inscribe his name on his coinage, frequently employed this motif. He was followed by subsequent Macedonian kings: see (Franks 2012, pp. 40–48, Figures 28, 30, 33–40). Alexander the Great appears on his coinage as both a mounted hunter and warrior: see (Wartenberg forthcoming). The successors of Alexander adopted similar imagery on their coinage—a notable example is Eucratides of the Graeco-Bactrian kingdom (r. 171–145 BC), who appears on the obverse in a Macedonian military helmet, with two mounted riders on the reverse: e.g., (Thonemann 2015, pp. 98–100, Figure 5.19–5.20, p. 150, Figure 8.6). |

| 53 | For instance, an amphora found at Kültepe, Cappadocia dating to the 4th–3rd century BC shows a hunter mounted on horseback aiming his spear at a leopard: (Miller 2014, p. 196, Figure 5.16; Özgüç 1971, pp. 92–93, pl. 30). Another noteworthy example—though from an earlier period—that shows a Near Eastern connection is a lekythos by the Xenophantes Painter (ca. 390–380 BC) that shows Persians (including one on horseback and one in a horse-drawn chariot) hunting both real and fantastical animals: (Cohen 2010, pp. 87–88, 89, Figure 33). For examples of warriors with their horses on earlier red-figure Attic vases from the late 6th–5th centuries BC, roughly contemporaneous with the reign of Alexander I of Macedon, see (Tripodi 1998, pp. 26–28, 144–45, Figures 4–6). |

| 54 | Votive terracotta plaques from Hellenistic Troy show mounted warriors and hunters: (Thompson 1963, pp. 108–116, no. 108–128, pl. XXVII-XXVIII). A notable example from Egypt is a terracotta figure of the dwarf god Bes as a mounted warrior in the Greek tradition: (Török 1995, pp. 37–38, no. 19, pl. VII). Bes is shown with his characteristic animal-like face and dwarf-like legs, but has a muscular torso and wears a kilt. In his right hand, Bes raises his sword above his head. In his left, he holds a round shield. The horse moves to the right and rears up. The figure dates to the late 2nd or early 1st century BC and shows that, by this time, artists were experimenting with syncretic mixtures of Egyptian religion and the Greek horseman-hero. Another monument that encapsulates this syncretism is a limestone relief stele found at Tebtunis in the Fayyum, which depicts the god Heron (originally Thracian Heros, this god became popular among Ptolemaic soldiers) astride a horse that rears to the right. He wears a tunic and an Egyptian royal nemes headdress; in his right hand, he holds out a phiale. The stele dates to the 1st century B.C. and is inscribed in both Demotic (illegible) and Greek. The Greek inscription records the name of the dedicator of the stele as Manres, also called Sisois: (Nachtergael 1996). |

| 55 | (Rotroff 1982, p. 19, nos. 238–72, pl. 46–54). These were found in Athens but Palagia (2000, 206 note 170) raises the possibility that they were manufactured in Alexandria. |

| 56 | (Nenna and Seif el-Din 2000, pp. 86–88, 281 no. 369, pl. 56): a fragmentary Egyptian faience vase shows a nude warrior on horseback spearing his fallen enemy. |

| 57 | A bronze mirror cover shows two nude youths hunting a boar: (Cohen 2010, p. 73, Figure 25; Schwarzmaier 1997, p. 266, no. 78; Comstock and Vermeule 1971, p. 255, no. 367). |

| 58 | Silver appliques from the 4th-century BC Letnitsa treasure in Thrace: (Martinez et al. 2015, pp. 344–46, cats. 290–98). |

| 59 | A Thracian gold signet ring found near Starosel bears the image of a hunter on horseback attacking a boar: (Kitov 2009, p. 64 Figure 66; Kitov 2001, p. 25 Figure 15). |

| 60 | A gold-glass bowl found in a tomb in Tresilico (Reggio Calabra) depicts a hunter in Greek dress astride a rearing horse. The hunter aims his spear at a leopard. See (Cesarin 2016) for a comparison of this bowl with the hunt-frieze from Vergina Tomb II and a suggestion that the bowl may have been manufactured in Alexandria. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cole, S.E. Ptolemaic Cavalrymen on Painted Alexandrian Funerary Monuments. Arts 2019, 8, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020058

Cole SE. Ptolemaic Cavalrymen on Painted Alexandrian Funerary Monuments. Arts. 2019; 8(2):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020058

Chicago/Turabian StyleCole, Sara E. 2019. "Ptolemaic Cavalrymen on Painted Alexandrian Funerary Monuments" Arts 8, no. 2: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020058

APA StyleCole, S. E. (2019). Ptolemaic Cavalrymen on Painted Alexandrian Funerary Monuments. Arts, 8(2), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020058