Bringing Back the (Ancient) Bodies: The Potters’ Sensory Experiences and the Firing of Red, Black and Purple Greek Vases

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Because of its close ties to objects in the environment rather simply to a part of the spectrum, the ancient color experience could tap into smell, touch, taste and even sound. For Greeks and Romans, color was a basic unit of perception, a source of information and knowledge and a tool for accurately understanding the world around them … Using a single sense for all this was not always enough.

Ancient elite anxieties about the baseness of the senses, the corresponding baseness of those who relied on them and their proximity to animals who, by their nature were more attuned to such cues, likely contributed to the lack of (ancient) interest in the bodies of the banausoi (the artisan class).5 But this disdain and disinterest has had lasting implications for the scholarship on Greek vases, ignoring the intellectual and experiential knowledge of these ancient makers and reducing their bodily labor to only their hands.… the illiberal arts (banausikai), as they are called, are spoken against and are, naturally enough, held in utter disdain in our states. For they spoil the bodies of the workmen and the foremen, forcing them to sit still and live indoors and in some cases spend the day at the fire. The softening of the body involves serious weakening of the mind.(Xenophon, Oikonomikos 4.2–3)4

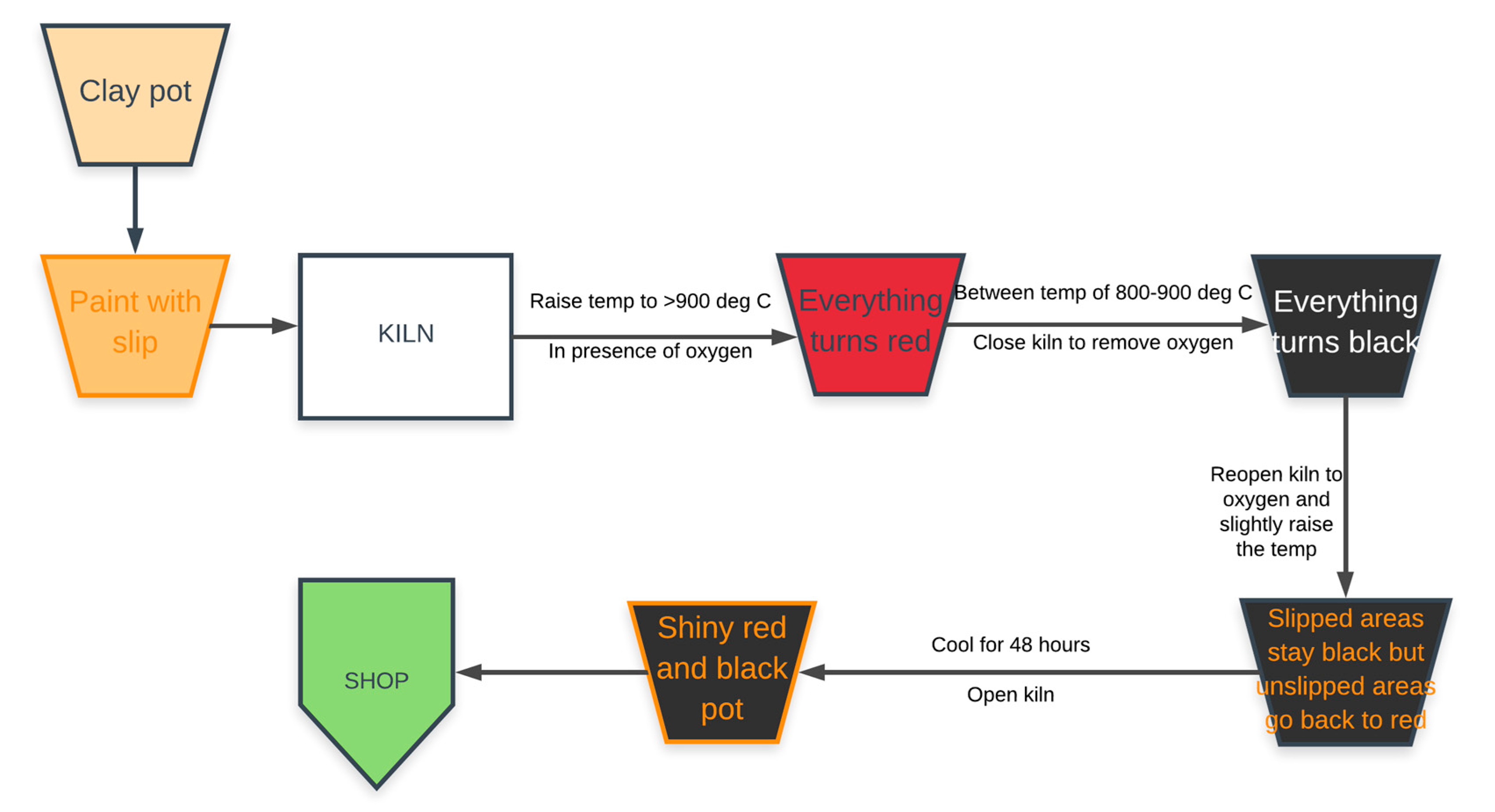

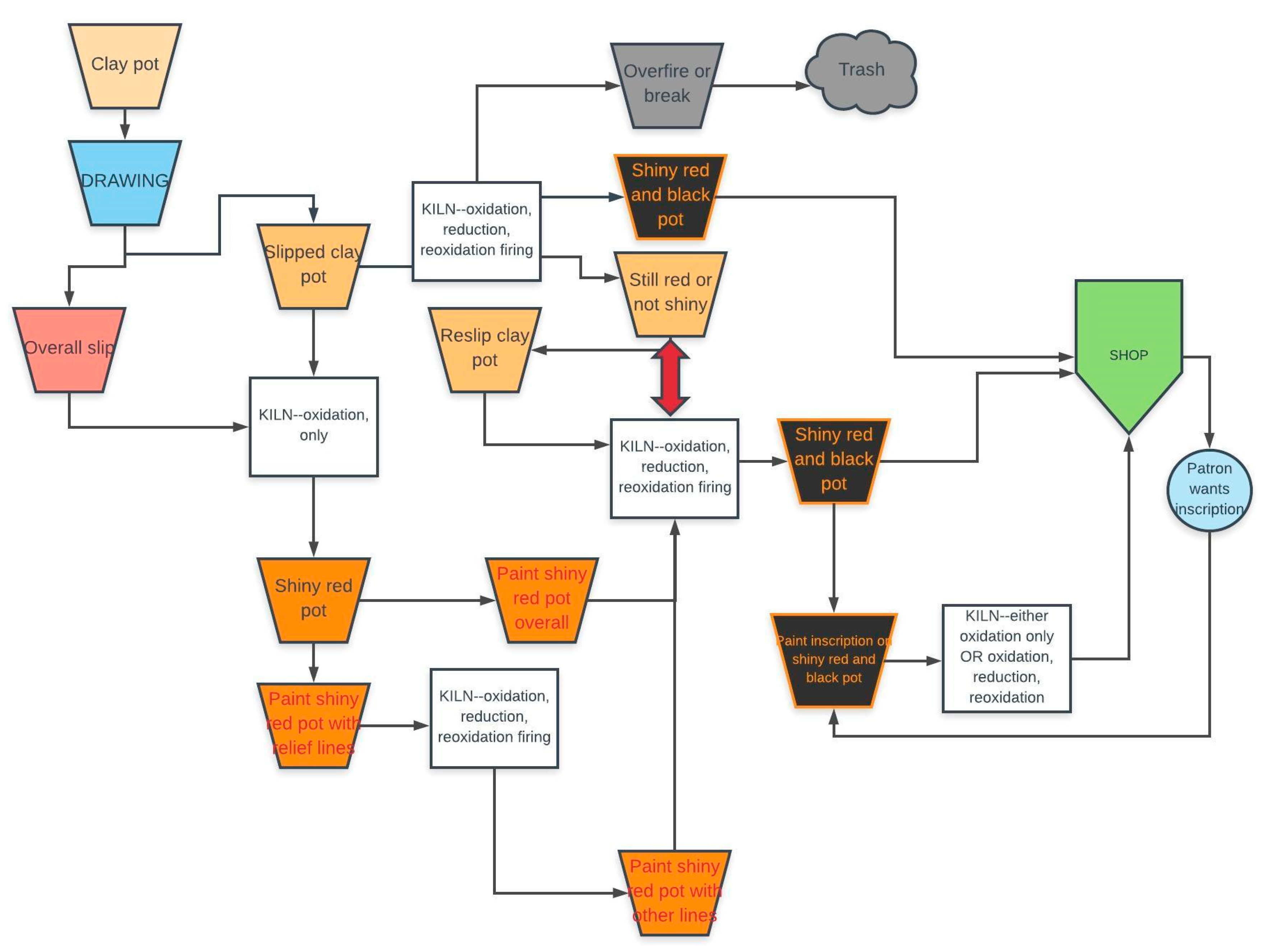

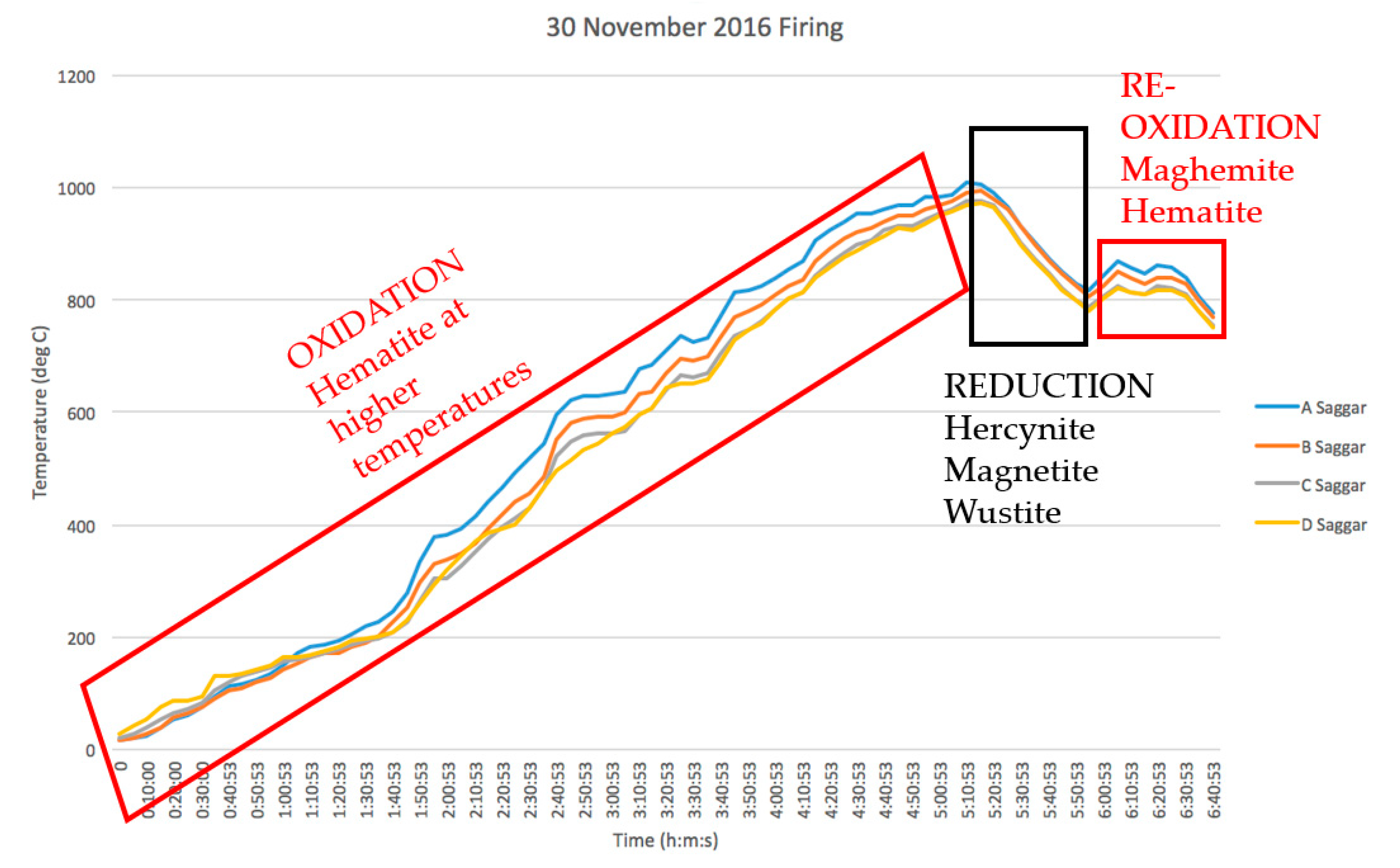

2. Chemically Bound Color: The Three-Phase Firing

3. Sensorially Guided Color: The Four-Phase Firing

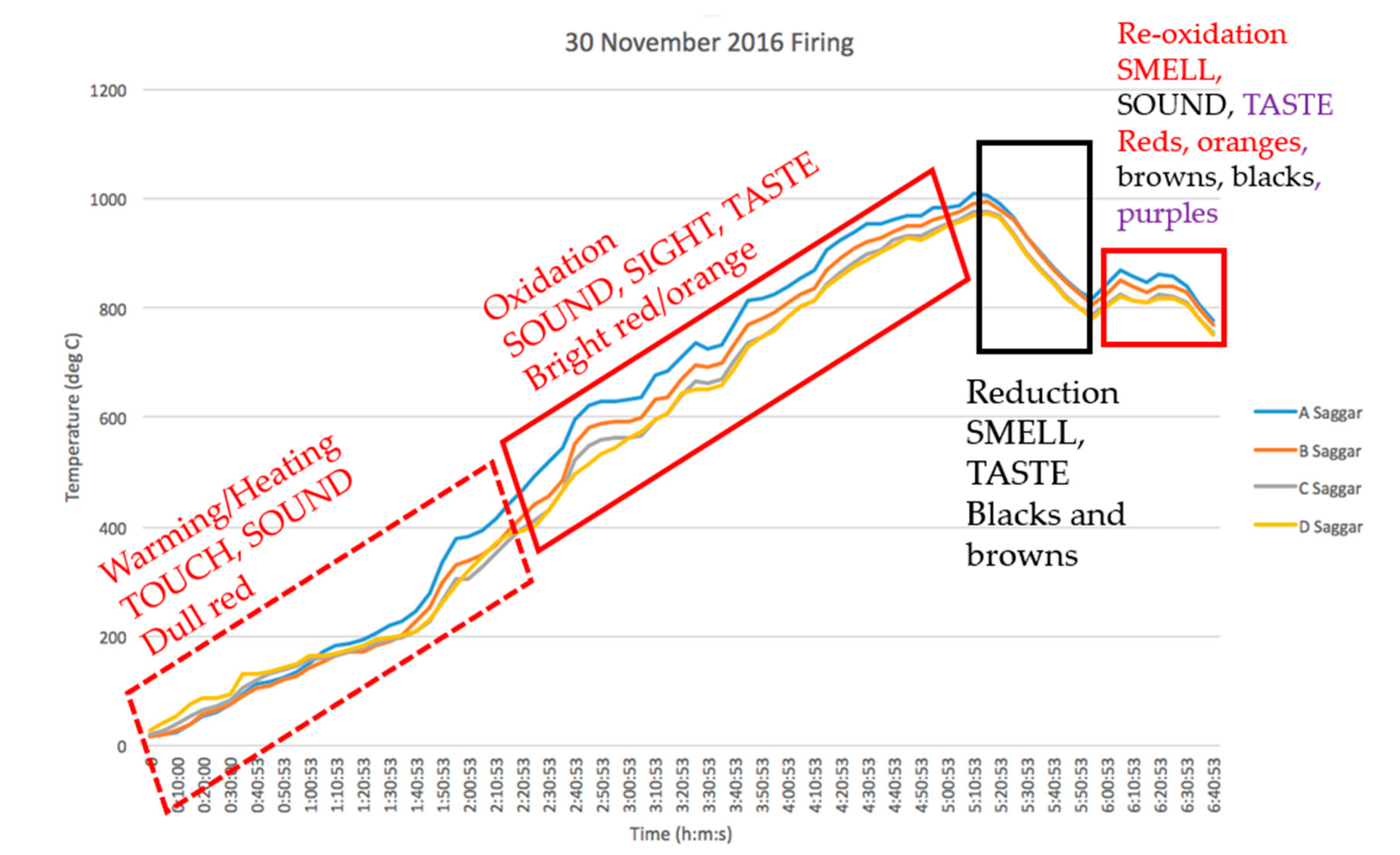

3.1. Sensory Phase 1: The Touch and Sound of Dull Red Pots

Potters, if you pay me for my song,then I ask that you, Athena, hold your hand above the kiln.—“Kiln,” Life of Homer 14.1–14.31

3.2. The Second Sensory Phase: The Sound, Sight and Taste of Bright Red Pots

in the hearing of voice, prayer, thunder and speech, an entire dialogue is played out among mortals and the divine. Each sound or speech is animated by the motion of an underlying significance to sounds, whether these sounds are ostensibly verbal or meterological. The sounds act as omens, bearers of meaning in a system of fate and prophesy that is as great and unknowable as the music of the spheres. Sound can mark our place in the world (as both space and time) but it does not always guarantee our agency.

3.3. The Third Sensory Phase: The Smell and Taste of Black Pots

It is tempting to consider whether potters chose their reduction fuel for their olfactory signatures as well as their performance, availability and cost. Did certain fuels signal cues in the reduction phase better than others? And if so, how did ancient kiln attendants smell? Was there an equivalent ancient odor to “hot dogs”?The Greeks, noting that the olfactory and gustatory modalities were physiologically associated, made use of the same semantics. Aristotle indicated that there is an analogy between the types of flavors and smells, but, “the odors not being quite as fully evident as the flavors, it is from the latter that the former derive their names.

3.4. Sensory Phase 4: The Smell, Sound and Taste (?) of Red, Black and Purple Pots

4. Conclusions

Despite this deliberate exclusion, the potters’ objects, full of their makers’ embodied experiences, were present in these rarified spaces and essential to the sensory and intimate worlds of the purchasers of their wares. While the more traditional kinds of evidence—archaeological, literary and epigraphic—might not record the physical bodies of these artisans, the objects they made and the sensory experiences accessible in the surfaces of those objects offer other ways to know these ancient people. I would argue that we have not tried to know them on their own terms. The objects they made tell us about who they were in their own specialized visual—and sensory—language. We only need to be willing to look, touch, listen, smell and even taste.We could make the potters recline on couches from left to right before the fire drinking toasts and feasting with wheel alongside to potter with when they are so disposed … But urge us not to do this, since, if we yield [the potter] will not be … a potter.

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aloupi-Siotis, Eleni. 2008. Recovery and Revival of Attic-Vase Decoration Techniques: What Can They Offer Archaeological Research? In Papers on Special Techniques in Athenian Vases. Edited by Kenneth Lapatin. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, pp. 113–28. [Google Scholar]

- Balachandran, Sanchita. 2018. Uncovering Ancient Preparatory Drawings on Greek Ceramics. The Iris. Available online: http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/uncovering-ancient-preparatory-drawings-on-greek-ceramics/ (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Arrington, Nathan T. 2017. Connoisseurship, Vases and Greek Art and Archaeology. In The Berlin Painter and His World: Athenian Vase-Painting in the Early Fifth Century B.C. Edited by J. Michael Padgett. Princeton: Princeton University Art Museum, pp. 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Boulay, Thibaut. 2018. Tastes of Wine: Sensorial Wine Analysis in Ancient Greece. In Taste and the Ancient Senses. Edited by Kelli C. Rudolph. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Mark. 2013. Color As Synaesthetic Experience in Antiquity. In Synaesthesia and the Ancient Senses. Edited by Shane Butler and Alex Purves. Durham: Acumen Publishing, pp. 127–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Mark, ed. 2015. Smell and the Ancient Senses. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Shane, and Sarah Nooter, eds. 2018. Sound and the Ancient Senses. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Shane, and Alex Purves, eds. 2013. Synaesthesia and the Ancient Senses. Durham: Acumen Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzedemetriou, Athena N. 2005. Parastaseis Ergastēriōn kai Emporiou Stēn Eikonographia Tōn Archaïkōn Kai Klasikōon Chronōn. Athēna: Tameio Archaiologikōn Porōn Kai Apallotriōseōn. [Google Scholar]

- Chaviara, Artemi, and Eleni Aloupi-Siotis. 2016. The Story of a Soil That Became a Glaze: Chemical and Microscopic Fingerprints on the Attic Vases. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 7: 510–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianchetta, Ilaria, Karen Trentelman, Jeffrey Maish, David Saunders, Brendan Foran, Marc Walton, Philippe Sciau, Tian Wang, Emeline Pouyet, Marine Cotte, and et al. 2015a. Evidence for an Unorthodox Firing Sequence Employed by the Berlin Painter: Deciphering Ancient Ceramic Firing Conditions through High-Resolution Material Characterization and Replication. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectroscopy 30: 666–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianchetta, Ilaria, Jeffrey Maish, David Saunders, Marc Walton, Apurva Mehta, Brendan Foran, and Karen Trentelman. 2015b. Investigating the Firing Protocol of Athenian Pottery Production: A Raman Study of Replicate and Ancient Sherds. Journal of Raman Microscopy 46: 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Beth, ed. 2006. Colors of Clay. Special Techniques in Athenian Vases. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Cuomo di Caprio, Ninina. 1984. Pottery Kilns on Pinakes from Corinth. In Ancient Greek and Related Pottery: Proceedings of the International Vase Symposium in Amsterdam 12–15 April, 1984. Edited by Herman A. G. Brijder. Amsterdam: Allard Pierson Series, pp. 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Day, Jo. 2013. Making Senses of the Past. Toward a Sensory Archaeology. Carbonadale: Southern Illinois University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dembin, Einav Z. 2018. Voicing the Past: The Implications of Craft-referential Pottery in Ancient Greece. In The Adventure of the Illustrious Scholar: Papers Presented to Oscar White Muscarella. Edited by Elizabeth Simpson. Boston: Brill, pp. 537–63. [Google Scholar]

- Draycott, Jane. 2015. Smelling Trees, Flowers and Herbs in the Ancient World. In Smell and the Ancient Senses. Edited by Mark Bradley. London: Routledge, pp. 60–73. [Google Scholar]

- Gliozzo, Elisabetta, Ian W. Kirkman, E. Pantos, and Isabella Memmi Turbanti. 2004. Black Gloss Pottery: Production Sites and Technology in Northern Etruria. Part II, Gloss Technology. Archaeometry 46: 227–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haland, Evy J. 2012. The Ritual Year of Athena: The Agricultural Cycle of the Olive, Girls’ Rites of Passage and Official Ideology. Journal of Religious History 36: 256–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilakis, Yannis. 2013. Archaeology and the Senses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hasaki, Eleni. 2002. Ceramic Kilns in Ancient Greece: Technology and Organization of Ceramic Workshops. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hasaki, Eleni. 2012. Craft Apprenticeship in Ancient Greece. In Archaeology and Apprenticeship: Body knowledge, Identity and Communities of Practice. Edited by Willeke Wendrich. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, pp. 171–202. [Google Scholar]

- Hedreen, Guy M. 2016. The Image of the Artist in Archaic and Classical Greece: Art, Poetry and Subjectivity. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heilmeyer, Wolf-Dieter. 2004. Ancient Workshops and Ancient ‘Art’. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 23: 403–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitch, Sarah. 2018. Tastes of Greek Poetry: From Homer to Aristotle. In Taste and the Ancient Senses. Edited by Kelli C. Rudolph. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hurwit, Jeffrey M. 2015. Artists and Signatures in Ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hyleck, Matthew, Lisa C. Kahn, John Wissinger, and Sanchita Balachandran. 2016. Recreating Greek Pottery. Recreating a Working Greek Kiln. National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts Journal 37: 90–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kamen, Deborah. 2013. Status in Classical Athens. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kasimis, Demetra. 2018. The Perpetual Migrant and the Limits of Athenian Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, Rebecca. F. 2014. Immigrant Women in Athens: Gender, Ethnicity and Citizenship in the Classical City. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Kingery, W. David. 1991. Attic Pottery Gloss Technology. Archaeomaterials 5: 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Langdridge-Noti, Elizabeth M. 2015. ‘To Market, To Market’: Pottery, The Individual and Trade in Athens. In Cities Called Athens. Studies Honoring John M. Camp II. Edited by Kevin F. Daly and Lee Ann Riccardi. Lanham: Bucknell University Press, pp. 165–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lapatin, K., ed. 2008. Papers on Special Techniques in Athenian Vases. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Sian. 2010. Images of Craft on Athenian Pottery: Context and Interpretation. Bollettino di Archeologia On Line 1: 12–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lühl, Lars, Bernhard Hesse, Ioanna Mantouvalou, Max Wilke, Sammia Mahlkow, Eleni Aloupi-Siotis, and Birgit Kanngiesser. 2014. Confocal XANES and the Attic Black Glaze: The Three-Stage Firing Process Through Modern Reproduction. Analytical Chemistry 86: 6924–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maish, Jeffrey P. 2008. Observations and Theories on the Technical Development of Coral-Red Gloss. In Papers on Special Techniques in Athenian Vases. Edited by Kenneth Lapatin. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, pp. 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis, Yannis, Eleni Aloupi, and A. D. Stalios. 1993. New Evidence for the Nature of the Attic Black Gloss. Archaeometry 35: 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, Joseph V. 1988. The Techniques of Painted Attic Pottery. Revised Edition. London: Thames and Hudson. First published 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, John K. 2003. Ceramicus Redivivus. The Early Iron Age Potters’ Field in the Area of the Classical Athenian Agora. Hesperia Supplements. Princeton: American School of Classical Studies in Athens, vol. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Purves, Alex, ed. 2018. Touch and the Ancient Senses. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, Gisela M. A. 1923. The Craft of Athenian Pottery: An Investigation of the Technique of Black-Figured and Re-Figured Athenian Vases. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rowan, Erica. 2015. Olive Oil Pressing Waste as a Fuel Source in Antiquity. American Journal of Archaeology 119: 465–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, Kelli C., ed. 2018. Taste and the Ancient Senses. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sanidas, Giorgos M. 2013. La Production Artisanale en Grece. Lille: Editions du Comite des Travaux Historiques et Scientifiques. [Google Scholar]

- Sapirstein, Philip. 2013. Painters, Potters and the Scale of the Attic Vase-Painting Industry. American Journal of Archaeology 117: 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, David A., Karen Trentelman, and Jeffrey Maish. forthcoming. Collaborative Investigations into the Production of Athenian Painted Pottery. In New Approaches to Ancient Material Culture. Edited by Kate Cooper and Alison Surtees.

- Schreiber, Toby. 1999. Athenian Vase Construction. A Potter’s Analysis. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Squire, Michael, ed. 2016. Sight and the Ancient Senses. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Stissi, Vladimir. 2012. Giving the Kerameikos a Context: Ancient Greek Potters’ Quarters as Part of the Polis space, Economy and Society. In “Quartiers” Artisanaux en Grèce Ancienne: Une Perspective Méditerranéenne. Edited by Arianna Esposito and Giorgos M. Sanidas. Villeneuve d’Ascq: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, pp. 201–30. [Google Scholar]

- Stissi, Vladimir. 2016. Minor Artisans, Major Impact? In Töpfer Maler Werkstatt. Edited by Norbert Eschbach and Stefan Schmidt. Munich: C. H. Beck, pp. 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tonks, Oliver S. 1908. Experiments with the black glaze on Greek vases. American Journal of Archaeology 12: 417–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venit, Marjorie S. 1988. The Caputi Hydria and Working Women in Classical Athens. The Classical World 81: 265–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, Michael J. 1985. Artful Crafts: The Influence of Metal Work on Athenian Painted Pottery. The Journal of Hellenic Studies 105: 108–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, Michael J., and David W. J. Gill. 1994. Artful Crafts: Ancient Greek Silverware and Pottery. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, Marc, Karen Trentelman, Marvin Cummins, Giulia Poretti, Jeffrey Maish, David Saunders, Brendan Foran, Miles Brodie, and Apurva Mehta. 2013a. Material Evidence for Multiple Firings of Ancient Athenian Red-Figure Pottery. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 96: 2031–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, Mark, Karen Trentelman, Jeffrey Maish, David Saunders, Brendan Foran, Piero Pianetta, and Apurva Mehta. 2013b. Compositional Characteristics of Athenian Black Gloss Slips (5th c. B.C.). Microscopy and Microanalysis 19: 1400–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, Marc, Karen Trentelman, Ilaria Cianchetta, Jeffrey Maish, David Saunders, Brendan Foran, and Apurva Mehta. 2015. Zn in Athenian Black Gloss Ceramic Slips: A Trace Element Marker for Fabrication Technology. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 98: 430–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, Martin L. 2003. Homeric Hymns, Homeric Aprocrypha, Lives of Homer. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 391–95. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Dyfri. 2009. Picturing Potters and Painters. In Athenian Potters and Painters Volume II. Edited by John H. Oakley and Olga Palagia. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 306–17. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Dyfri. 2016. Peopling Athenian Kerameia: Beyond the Master Craftsmen. In Töpfer Maler Werkstatt. Edited by Norbert Eschbach and Stefan Schmidt. Munich: C. H. Beck, pp. 54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Dyfri. 2017. Beyond the Berlin Painter: Toward a Workshop View. In The Berlin Painter and His World: Athenian Vase-Painting in the Early Fifth Century B.C. Edited by J. Michael Padgett. Princeton: Princeton University Art Museum, pp. 144–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wissinger, John C., and Lisa C. Kahn. 2008. Re-creating and Firing a Greek Kiln. In Papers on Special Techniques in Athenian Vases. Edited by Kenneth Lapatin. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, pp. 129–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfert, Paula. 2009. Mediterranean Clay Pot Cooking. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | |

| 2 | See the translation by Marjorie J. Milne, published in (Noble [1965] 1988, pp. 190–91). |

| 3 | While it would be physically possible to carry out a firing alone, it seems unlikely in an industry that had access to cheap labor, especially slave labor. |

| 4 | Cited in (Hedreen 2016, p. 4). |

| 5 | |

| 6 | See Penteskouphia Pinax, Berlin Antikensammlung, inv. F891. |

| 7 | See Athenian red-figure kalpis hydria in Vicenza, Banca Intesa inv. 2, attributed to the Leningrad Painter, dated to c. 470–450 BCE. I would argue that this figure may be drawing rather than painting based on extant evidence for drawing still visible on ceramics. See Balachandran (2018). |

| 8 | See black-figure Boeotian skyphos, Athens, National Museum, inv. No. 442., dated to 400–390 BCE. |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 | Saunders et al. (forthcoming) and Maniatis et al. (1993) provide a useful summary of past attempts to characterize black gloss. |

| 14 | Aloupi-Siotis (2008), Chaviara and Aloupi-Siotis (2016), Cianchetta et al. (2015a, 2015b), Gliozzo et al. (2004); Kingery (1991); Lühl et al. (2014); Maniatis et al. (1993); Schreiber (1999); Walton et al. (2013a, 2013b, 2015). It should be noted that there are some debates among these scholars regarding the chemical characterization and production technologies of ancient Greek ceramics. |

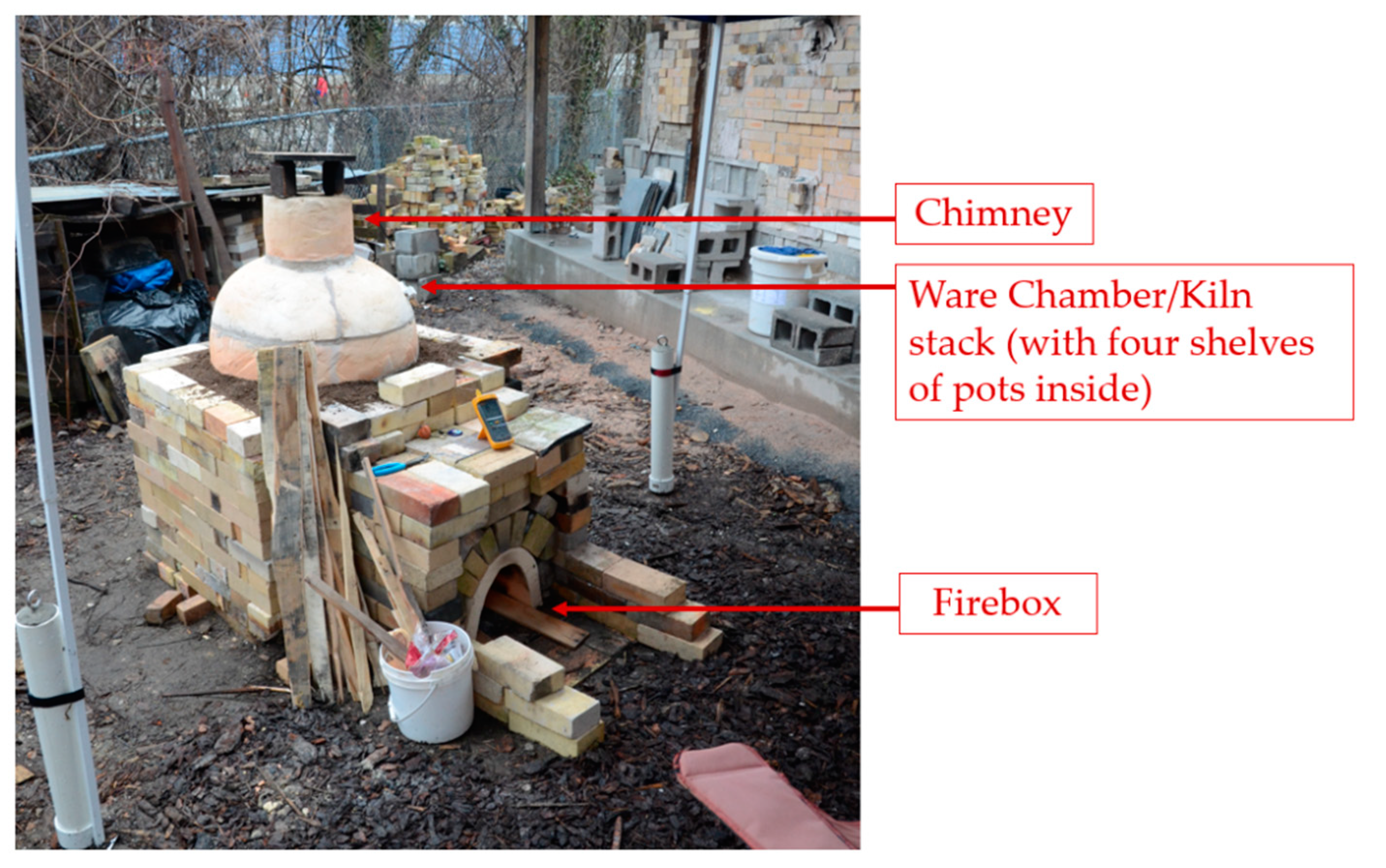

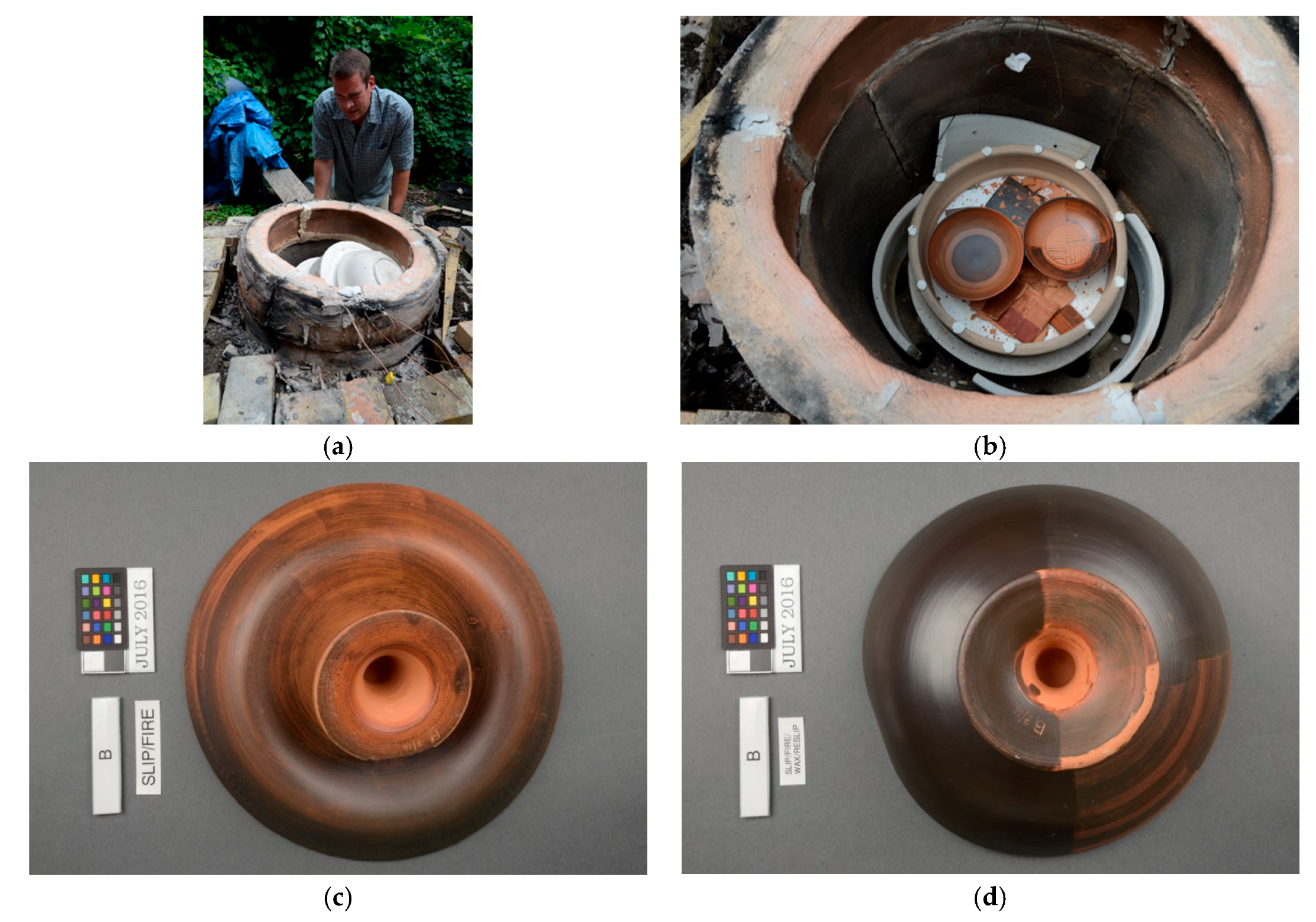

| 15 | See Hyleck et al. (2016). A description of the beehive shaped updraft kiln built for this project is available here: http://archaeologicalmuseum.jhu.edu/the-collection/object-stories/recreating-ancient-greek-ceramics/week-9-building-and-breaking/. |

| 16 | The initial firing was the focus of the 2015 course “Recreating Ancient Greek Ceramics” co-taught by the author and potter Matthew Hyleck at Johns Hopkins University. A full account of the project is available at the website: http://archaeologicalmuseum.jhu.edu/the-collection/object-stories/recreating-ancient-greek-ceramics/. The short film, Mysteries of the Kylix (https://vimeo.com/140393971) also documents this course and the first firing. |

| 17 | It is still unclear whether there was one preferred ancient Athenian clay source, though the specific preferred morphological and chemical characteristics of the clay used to make Athenian vases has been extensively studied by Aloupi-Siotis (2008), Chaviara and Aloupi-Siotis (2016), Cianchetta et al. (2015b), Lühl et al. (2014) and Walton et al. (2013b). The lack of a singular “identifiable” clay source suggests that potters may have mixed their clay to suit their personal preferences even if there were particular preferred clay deposits that were typically exploited. As all contemporary potters will attest, the choice of clay is the most fundamental and personal decision of any practitioner. |

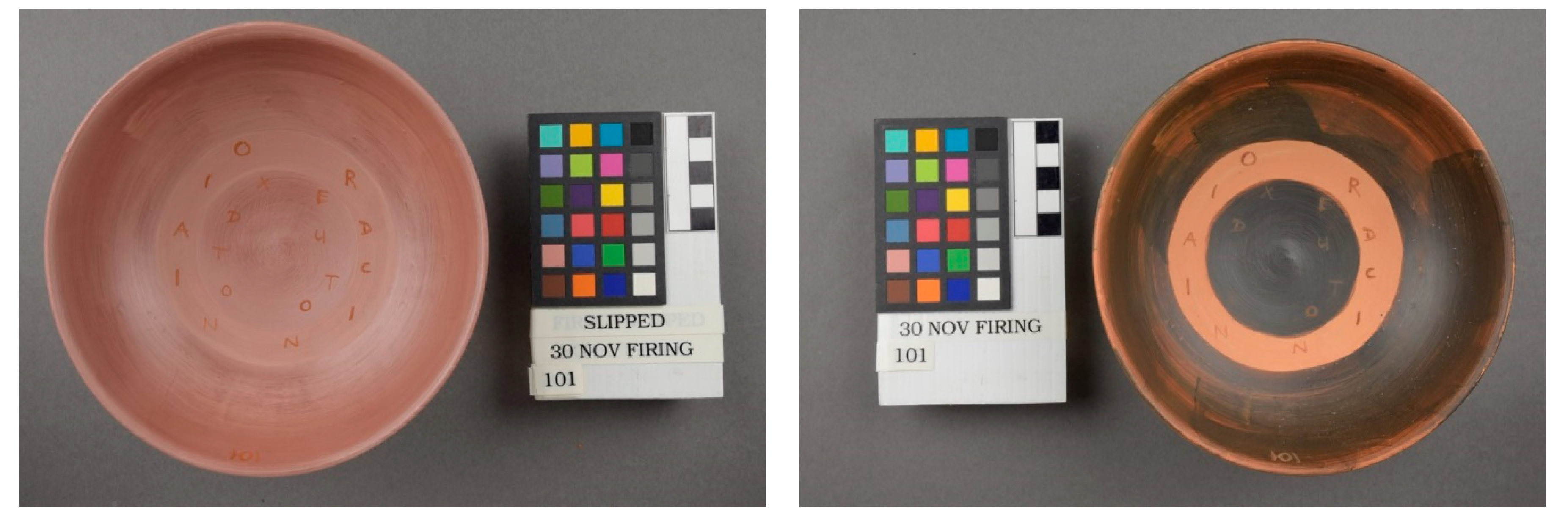

| 18 | We used Cedar Heights Redart 103 earthenware clay from Pittsburgh, PA, as our base clay for both vessels and slip. Iron oxide pigments purchased from Kremer Pigments, NY, were utilized for painted inscriptions. |

| 19 | Nearly all vessels and tiles were made and assembled primarily by Matthew Hyleck with the assistance of potter Camila Ascher. Preparatory drawings on these surfaces were carried out by Karun Pandian, the author and Hyleck. The objects were slipped (i.e., painted) by the author and Hyleck. Firings typically involved at least four participants, with Hyleck as the kiln master, along with the author, potters Ascher and Anastassia Sovolieva, materials scientist Patricia McGuiggan and classicist Ross Brendle. An additional four plates prepared in the black figure technique were provided by Eleni Aloupi-Siotis (Thetis Authentics, Ltd, Athens, Greece) for test firing. |

| 20 | Recent analyses at the Getty provide evidence that both the Kleophrades Painter and the Berlin Painter used more complex, multiple firing techniques. See Cianchetta et al. (2015a, 2015b), Maish (2008), Saunders et al. (forthcoming) and Walton et al. (2013a, 2013b). |

| 21 | Thus far, there is little evidence of kiln wasters specific to multiple firings, suggesting that more complicated multiple firings may have been a specialized practice. However, the regular refiring of pots to correct firing mistakes is to be assumed and has been raised by Aloupi-Siotis (2008). Noble considered re-firing ancient pots to correct ancient flaws, though he admitted that “this does raise the ethical and moral question as to whether it is proper to correct an error made by an ancient potter in firing his kiln several thousand years ago” (Noble [1965] 1988, p. 181). |

| 22 | I am grateful to H. Alan Shapiro, David Saunders, Annette Giesecke, Jennifer Stager and Andrew Stewart (through Jennifer Stager) for their thoughts on whether the ancient Greeks themselves described or distinguished their own ceramics in this way. Shapiro suggested that these descriptive “categories” of objects perhaps developed in the 19th century scholarship and not in the ancient world. |

| 23 | See Cianchetta et al. (2015b), Gliozzo et al. (2004), Lühl et al. (2014) and Maniatis et al. (1993). Note that there are some disagreements in the scientific literature about the characterization of specific iron oxides, though there is consensus that black iron oxides are only formed during the reduction phase. |

| 24 | See Papadopoulos (2003). Some of the painted plaques from Penteskouphia show kilns with delineated spy-holes (small upside-down “u” shapes) which could have been opened to draw out test pieces. It is unclear from the extant archaeological evidence how typical this feature was. See Hasaki (2002) for kiln evidence. Our kiln did not include a spy-hole. |

| 25 | |

| 26 | Matthew Hyleck, personal communication, 10/26/2018. Noble also notes this awareness on the part of potters (Noble [1965] 1988, p. 154). |

| 27 | Contemporary potters assume that one third of a kiln-load is likely to be lost or damaged beyond sale, even in a successful firing. |

| 28 | For recent scientific and technical studies, see Aloupi-Siotis (2008), Chaviara and Aloupi-Siotis (2016), Cianchetta et al. (2015a), Cianchetta et al. (2015b), Gliozzo et al. (2004), Kingery (1991), Lühl et al. (2014), Maniatis et al. (1993), Schreiber (1999), and Walton et al. (2013a, 2013b, 2015). It should be noted that none of our experimentally produced ceramics were subjected to scientific analyses to verify the different iron oxidation states mentioned in the published literature; however, this is an area of future research. |

| 29 | The optimal temperature to be reached depends on the clay being used. For the RedArt clay used in our firings, it was necessary to reach 1000 degrees Celsius to ensure reduction. This optimal temperature may have been somewhat different for Attic or Corinthian clays. |

| 30 | Our datalogger information ends soon after the temperature fell below 800 degrees Celsius because the recording equipment was disconnected after this time. |

| 31 | I am grateful to Annette Giesecke for her translation. See West (2003, pp. 390–95), for the original Greek text. |

| 32 | In his translation, West refers to Asbetos as “Overblaze,” rather than “Unquenchable” as in Milne’s translation in (Noble [1965] 1988) but both terms suggest a kiln grown too hot. See West (2003, p. 393). |

| 33 | Translation by Milne, as published in (Noble [1965] 1988, pp. 190–91). |

| 34 | Milne in (Noble 1988, p. 190). |

| 35 | This assumes that reduction takes between twenty to forty minutes over the course of an eight hour firing, which was our general experience. |

| 36 | As with oxidation, the optimal reduction temperature is clay dependent. For RedArt clay, beginning reduction around 1000 degrees centigrade was most effective. However, lower temperatures were workable for the test pieces sent to us by Thetis Authentics, Ltd. |

| 37 | Cuomo di Caprio (1984) even mentions the use of cut up horses’ hooves as a possibility for fuel. |

| 38 | See the Penteskouphia plaque currently in the collection of the Louvre, accession number MNB 2856. |

| 39 | See Penteskouphia Pinax, MNB 2856, Louvre, dated 575–550 BCE. |

| 40 | See Langdridge-Noti (2015) on buying pots. |

| 41 | As mentioned in Geoponia VI, 3, as a way to test the quality of a pithos. See Richter (1923, p. 88). |

| 42 | Boulay (2018, p. 210). Though Boulay is speaking of wine in this instance, the same characteristics apply to ceramics production. |

| 43 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balachandran, S. Bringing Back the (Ancient) Bodies: The Potters’ Sensory Experiences and the Firing of Red, Black and Purple Greek Vases. Arts 2019, 8, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020070

Balachandran S. Bringing Back the (Ancient) Bodies: The Potters’ Sensory Experiences and the Firing of Red, Black and Purple Greek Vases. Arts. 2019; 8(2):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020070

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalachandran, Sanchita. 2019. "Bringing Back the (Ancient) Bodies: The Potters’ Sensory Experiences and the Firing of Red, Black and Purple Greek Vases" Arts 8, no. 2: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020070

APA StyleBalachandran, S. (2019). Bringing Back the (Ancient) Bodies: The Potters’ Sensory Experiences and the Firing of Red, Black and Purple Greek Vases. Arts, 8(2), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020070