Abstract

With the outbreak of the Syrian conflict in 2011, many artists left as part of a massive migratory flow out of the country. Other artists had already migrated because of perceived constraints to art-making due to censorship and lack of professional opportunities. Both waves of migration converged in artistic hubs throughout the Middle East and Europe. From the interviews I carried out with visual artists from Syria displaced in London and other locations, it emerged that they faced a shared dilemma. Many wished to move away from politics focusing on universal themes like human suffering, which in the Syrian art-scene were perceived to be apolitical. In exile, however, it is precisely these themes that marked their works as political in the eyes of agents of the artworld and international audiences. I argue that this politicization is a form of essentialization and homogenization of the Syrian art-scene abroad, for categorizing these artists as ‘Syrian’ or ‘Middle Eastern’ flattens their individual creativity by placing them within a national or regional category. This form of ‘othering’ is rooted in the history of Western colonialism in the Middle East and postcolonial geopolitics and power relations structuring the Syrian conflict and Western perceptions of it. I show how my informants attempt to overcome these constraints by employing the discursive register of universalism, while often organizing their lives around the ‘Syrian artist’ category.

1. Introduction

Just two months after having worked as anesthetist in a Damascene hospital, Tarek Tuma, an aspiring painter from Douma, decided to start a new life in London. Beginning in 2005, he studied English for more than a year to allow himself to train as artist. He was accepted into The Art Academy and later graduated from the prestigious City & Guilds of London Art School. However, Tarek struggled economically. Having recently become an art history teacher in a primary school, his dream is to become a full-time artist.

In this thesis, I investigate dynamics at play for Syrian artists like Tarek, who are navigating the international, Western-centered artworld, having been displaced from their country and its artistic scene. I specifically concentrate on the tension between these artists’ claims to mediate universal, apolitical themes, and the ‘politicizing’, essentialist discourses pervading the Western art industry. I will use the term ‘visual artist’ in an all-encompassing way, referring to someone who engages in artistic practice and exhibits in available platforms (via market or other routes), to avoid falling into an unreflecting collapsing of ‘artist’, ‘anti-regime’, ‘activist’, as generally assumed by literature written from a Western perspective.

With the outbreak of the conflict in 2011, following protests asking for the toppling of President Asad and a ‘democratic shift’ for Syria, most artists left as part of a massive migratory flow out. They converged in artistic hubs throughout the Middle East (Beirut, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Doha, Bahrain) and, predominantly, Europe (Figure 1). Many anti-regime artists from older generations ended up in France and young talents in Germany (Griswold 2018). Artistic partnerships with France were established before the war because of available scholarships sponsored by French art institutions, installed in Syria since the colonial period1. Since 2011, many have found prolific platforms throughout France, mainly thanks to the association Syria.art. As for Germany, as a result of the open-door policies by Merkel’s government in 2015, it represents a central hub for Syrian artists (Holmes and Castañeda 2016).

Figure 1.

Map following the paths of a hundred artists who have fled Syria since 2011. Source: Griswold (2018), public domain image.

This phenomenon has intensified throughout the war and, as it stands now, the Syrian art-scene can be said to have mobilized out of the country’s borders. The current situation of emergency in Syria—a site for proxy warfare—is dramatic: Beyond half of the population is in need of humanitarian assistance, the UN estimates that the number of killings is around 400,000, and there are approximately 5.6 million refugees abroad (UN News 2018). At the same time, other artists like Tarek left before 2011, because of perceived constraints to art-making due to censorship, but also lack of innovation in the arts and difficulty finding professional opportunities. This landscape is reflected in my informants’ trajectories: Some moved abroad in the early 2000s to receive more ‘sophisticated’ training, and never returned, whilst others had to flee because of war and persecution. Greater accessibility of their works to wider audiences and, in some instances, an ‘aesthetic adaptation’ to the conflict, has given way, beyond their intentions, to the ‘Syrian refugee art industry’. I contextualize these developments exploring dilemmas encountered by artists from Syria trying to emplace themselves in new artistic contexts: How does the Western-centered art-scape get configured in their eyes, in comparison to the Syrian one? What new demands and stereotypes do they confront, and how do they respond to them? Are artists asked to reflect on their practice in new ways? Do they use art to reflect on the conflict? How are their works received, and through what lenses are they interpreted? In other words, what is the social and political logics of being a Syrian artist today? These are important questions that I explore through my informants’ perspectives. I am interested in the relationship between sociopolitical change and aesthetic transformation, and I hope to contribute to existing literature on ‘artists at times of war’2 through an anthropologically informed study of these artists’ status. As I will discuss, this approach involves disentanglement from mainstream curatorial practices tending to homogenize ‘Arab artists’ under a regional category that has political connotations (Schneider 2017, p. 15).

Talking with my informants, I immediately encountered a refusal to communicate a political stance when asked to reflect on their art, which deserves investigation. Despite differences in style, themes, media used, backgrounds, and ethnic status, a common contradiction emerges for displaced Syrian artists. One the one hand, in Syria, visual artists tended to privilege abstract painting and depict ‘universal’ themes such as ‘human suffering’ to escape censorship, but also because they were thought to transcend politics, understood as taking a position with regard to concrete political players (i.e., the regime). However, to their own surprise, it is precisely these themes that, in exile, render their art ‘political’ for audiences, insofar as they perceive such focus on ‘suffering’ as an intervention in the conflict. Artists see such ‘politicization’ as ‘trivialization’ of their work connected to their shared uneasiness with the ‘Syrian artist category’ used to describe them. They perceive such identification, that posits them as ‘Syrian’/‘Middle Eastern’ before ‘artists’, as forced because it values their identity over their talent. I attempt to bring light to, and eventually challenge, ideological frameworks behind such processes of homogenization, thus offering broader insights on the relatively peripheral place of ‘minority-artists’ in the international artworld.

I argue that my informants use a discursive strategy of ‘universal humanism’ when articulating the significance of their work and that they tend to distance their art from politics because their approaches are informed, to varying degrees, by the specific legacy concerning artists’ relationship to the Syrian regime. This has often brought artists to ‘suspend the political’ and focus on themes considered universal and apolitical. When entering the Western-centered artworld, artists from Syria reclaim the ‘autonomy’ of their art in reaction to external interpretations that ‘localize’ their work, based on prevalent assumptions that the Syrian regime has hindered all forms of creativity as a result of oppression. These artists are also expected to visually represent the war, communicating their political positioning within it. I encourage focus on the fact that desires mapped into Syrian artists’ production—by the art industry, its agents, and audiences—are shaped by geopolitical dynamics, namely the place of ‘the West’ in the conflict and historical presence in the region. I argue that the criterion for approaching Syrian art has changed from ‘ethnicity’ and ‘location’—thought to be encapsulated in Arabic/Islamic calligraphy—to ‘national identity’ and ‘politics’—expected to transpire from works dealing with current political events. Thus, what it means to be a ‘Syrian artist’ has changed, and a form of ‘othering’ continues being reproduced by the market. I show that the political relevance of art is not always the consequence of artists’ choice, since they are embedded in complex networks and situated in a discursive space. More generally, I conclude that the artworld remains a highly contested site where cultural identity, political claims, and power relations are negotiated and re-inscribed. It will be seen that while most artists lament such categorization as ‘Syrian’ because it is ‘flattening’ their individual creativity, for some it reveals useful for emerging in a competitive marketplace. In fact, most are unable to escape it, because channels provided—galleries promoting ‘Middle Eastern art’, or exhibitions centered around national/regional political climate—tend to reinforce it. In the Conclusions, I reflect on future prospects for my informants, navigating between disillusionment and hope, as Syria has entered the eighth year of war.

Concerning my approach to my informants, I concentrated on their subjectivity and discourses, treating them as ‘epistemic partners’ (Given 2008), considering they have expertise to share—from first-hand experience of the Syrian art-scene, to knowledge of institutional dynamics of the artworld—while acknowledging the necessity to deconstruct the view that artists are detached from society.

2. Materials and Methods

This paper draws most of its ethnographic data from six weeks of fieldwork I conducted in London in the summer 2017. During this time, I met and interviewed six visual artists. As outlined, Tarek Tuma is a painter and art teacher; Hasan Abdalla is a painter, originally Kurdish, who fled Syria because of persecution; Ammar Azzouz is an architect from Homs, now working as architect at the firm Arup; Hrair Sarkissian is an established photographer from Damascus; Issam Kourbaj is a conceptual artist in residence and Lector in Art at Cambridge; and Ibrahim Fakhri is an activist and graphic designer from Damascus. Carrying out semistructured, in-depth interviews with a topic-guide (see Appendix A) was meant to allow my informants to provide the information they think is important (Wolcott 2005, p. 160). All of them are fluent in English. I contacted them via email or Facebook, having come across their names in online searches, and I encountered positive responses from all of them through oral consent. This might be partly due to their ‘aspiration of recognition or publicity’, as Duclos notes in relation to Iraqi artists in Damascus who did not want to be anonymized (Duclos 2017, p. 4), as well as their motivation to share with wider audiences their ideas related to art but also, for some, to the revolution that first. Concerns for some of my informants included covering war-related trauma or ‘politics’, disclosing information that would put their families—still in Syria—at risk. I tried to handle these ‘ethically important moments’ (Guillemin and Gillam 2004, p. 265) by avoiding sensitive questions. However, on occasion, they would ‘unintentionally’ reveal details and requested anonymity. Throughout the paper, I reflect on my positionality as a Western researcher studying Middle Eastern artists and the challenges involved.

The only criteria I followed in selecting participants were artists’ nationality, and the location where they are based (London)—‘purposive sampling’ (Bernard 2017, p. 14). This resulted in a diverse group of artists. My fieldwork consisted of repeated meetings, going to artists’ exhibitions, visiting their houses/ateliers, etc. I also had the chance to talk with curators, as well as academics specialized in Syria, such as political scientist Wendy Pearlman and writer Malu Halasa.

As for my methodological choice of London as my main field-site, I adopted Candea’s suggestion of re-valuing ‘arbitrary locations’, for it allows the ethnographer to appreciate the multi-sitedness, but also incompleteness, of any local context (Candea 2007, p. 172; Gellner 2012, p.11). London is ‘arbitrary’ as ‘it bears no necessary relation to the wider object of study (Candea 2007, p. 180), the Syrian art-scene. Indeed, as I will discuss, the UK does not represent a central concentration point for Syrian artists. London is not a ‘traditional village’ but a metropolis and main global art center, within which I travelled to meet my informants.

When dealing with members of a population experiencing unprecedented migration out of the country, it might be argued that the most appropriate method is ‘multi-sited ethnography’, a necessary adaptation of the discipline to changing world realities, suited to the study of transnational communities (Marcus 1995; Gupta and Ferguson 1997). Existing literature on diasporas is extensive3, including research on displaced artists from the Middle East, especially Iraqi (Shabout 2012), Egyptian (Winegar 2008a), Palestinian (Boullata 2004; De Cesari 2012; Salih and Richter-Devroe 2014), and Iranian (Naficy 1991; Walker-Parker 2005). I deal with individual, displaced professionals with different personal paths and approaches, rather than a unified community of artists, and my methodological choices respond to these conditions. Indeed, I carried out other six semistructured interviews through Skype to gauge an idea of the artistic scene in other hubs where Syrian artists are based. Of these, Houmam Al-Sayed is a popular painter working in Lebanon, Gregory Buchakjian is a Lebanese photographer and art historian specialized in Middle Eastern art, and Dima Nachawi is an illustrator and clown-performer based in Beirut. Jaber Al Azmeh—photographer from Damascus living in Qatar—, Tammam Azzam—who uses different media, currently working in Germany—, and Ammar Abd-Rabbo—photographer and journalist based in France since childhood—are among the most well-known contemporary artists from Syria. These interviews helped me to identify narratives common to exiled Syrian artists, and I encourage further research to enrich the data collected.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Booming Syrian Art-Scene

In the last decade or so, before the 2011 protest movement, public media, the internet, and the international artworld have been putting the spotlight on ‘the emerging Syrian art-market’ (Anderson and Duncan 2010). Statements such as ‘Syria is liberalizing its economy, foreign capital is flooding into the country, and contemporary art is booming’ (DP News 2010) have been making the pages of Western newspapers, art blogs, and magazines, and websites of auction houses such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s, installed in Dubai since 2005. Since the early 2000s, these have claimed that art produced in the Middle East will find favor with Western collectors (Seaman 2016). As for Syria, the Ayyam gallery, founded in 2006, is considered the most successful in terms of primary and secondary market presence (Duncan 2010; Oweis 2010).

The perceived ‘latedness’ of Syria in entering the international market is partly connected to ‘Western misperceptions about the extent and nature of its authoritarian regime’ (Kluijver 2009). The process of institutionalization of art in Syria is considered still in its infancy in comparison to that of other countries in the region. Works by contemporary Syrian artists feature considerably less than those by Egyptian, Iranian, Lebanese, and Iraqi artists, and from the Gulf states, in auctions and exhibitions in the West—such as, among recent ones, ‘Unveiled: New art from the Middle East’ (London 2009), ‘Golden Gates: New Art from the Middle East’ (Paris 2009), and ‘Come Invest In Us. You’ll Strike Gold’ (Vienna 2012). Works by Syrians that have sold the most are by older generations (Kräussl 2014, p. 12). The opening of Ayyam—and other galleries such as Al Sayyed, Atassi, Tajallyat, Kalemaat, Free Hand, and Art House Syria—facilitated ‘the privatisation and professionalization’ of the art-scene in Syria (Woodcock 2012, p. 4). Under Hafiz Al-Asad, the government used to be the main cultural entrepreneur, establishing relations of tutelage with artists in a closed, socialist economy, whilst neoliberal measures implemented by Bashar have favored the emergence of a private sector in the arts, yet still controlled (Longuenesse and Roussel 2014, p. 30).

While I am not going to focus on the political context that determined conditions of production preceding this booming, I briefly explore how this legacy has informed predominant understandings of the relationship between art, politics, and the market among contemporary Syrian visual artists.

3.2. Artists’ Political Positionality

The typological schema proposed by Hasan Abbas (2005) helps to broadly understand visual artists’ positionality in relation to the regime, including those sustaining the ‘Official Ideology’, ‘Conformists’, ‘Others’, and ‘Those on the Opposition’4.

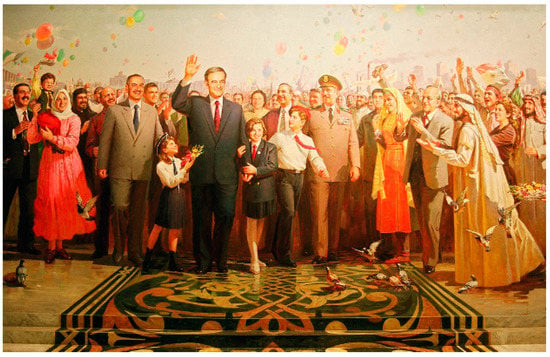

It can be seen that there is a clear polarization. At the center of the schema are artists following the Baathist party and its allied ones under the coalition of the National Progressive Front, who adopt a figurative, realist style celebrating Arabic heritage and the president as ‘Arab leader’ (Figure 2 and Figure 3)—among these, Mamdûh Qachelâna, Hilmi Sabûnî, and Ghazi Al-Khalidi, President of the Artists’ Trade Union, and Naji Obeid and Osama Jahjah, using Arabic calligraphy.

Figure 2.

What the Arabs brought to Europe. (Oil on Canvas.) Source: Al-Khalidi (1990), open access.

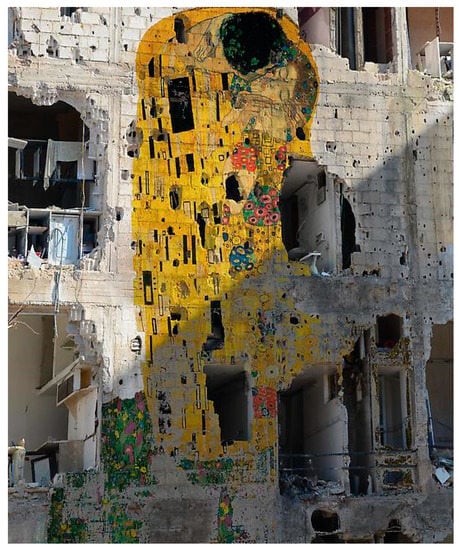

Figure 3.

Grand-scale mural staging Syria’s victory over Israel in the Yom Kippur War in lieu of defeat (n.d.). Damascus, Syria: October War Panorama Museum. Source: Stone Fish (2013), open access.

On the other hand, Abbas identifies artists on the opposition—‘circle of artists-activists’, including Ahmad Moualla, Nazir Ismail, artists exiled in Europe such as Sakher Farzât, Bachar al-‘Îssâ, and Najah al-Bukai, and the most representative case of Youssef Abdelke, member of the Communist Party, imprisoned for years because of caricatures of public authorities (Abbas 2005, p. 50). In general, it emerged that state-sponsored painters are dismissed by cultural elites as ‘inauthentic by dint of their association with the government’ (Shannon 2005, p. 377). In a way, it might be argued that I reproduce such discourses, delimiting my focus to artists not aligned with the regime, and relying on sources written from a Western, tendentially anti-regime perspective. I want to avoid falling into an analytically unreflecting collapsing of ‘artist’ and ‘anti-regime’. In fact, Abbas points out that artists supporting the regime are not ‘aesthetically conformists’ (Abbas 2005, p. 18)—i.e., they do not necessarily reproduce precepts of the main ideology. ‘Propaganda art’, anyway, has been extensively used by the regime since its very beginning, an example being Nizâr Sabûr’s gigantic portraits of President Hafiz (ibid., p. 35). Furthermore, Abbas notes that many artists have safeguarded a neutral position. This broad, stratified group includes those claiming not to be interested in politics and those exhibiting a ‘cold, anti-conformist violence’ (ibid., p. 52), such as Sara Shamma, internationally known for her images of anguished human bodies. As I will show, when entering the international scene, such ‘experience of suffering’ depicted by artists like Shamma will be interpreted as political statements.

I discussed with Tarek the multilayered engagements of artists with the establishment:

Yet, regardless of their political views, he would evaluate these artists’ work ‘as pieces of art in themselves’, citing the distinctively ‘Syrian’, ‘neutral’ style of Safwan Dahoul, one of the most popular painters, known since the 80s for his ‘Dream’ series featuring distressed female figures5.Until now you have pro-regime artists, but also those refusing to take sides. If you’re a neutral artist, you’re either afraid of the regime or you’re with it, and in that case you wouldn’t want to reveal your position now.

Art commentators in the West such as Mayamanah Farhat tend to think that pervading themes in Syrian artists’ production remain ‘abstracted, distorted studies of the human figure or commentary on recent political events’ (Woodcock 2012, p. 25). It is worth noting that throughout the second part of the 20th century, ‘the European tripartite system of private galleries, public museums and independent journalistic criticism’ (Lenssen 2014, p. 17) was not available in Syria, and absence of artistic criticism is unhelpful in fostering the popularity of art in society. Moreover, to have their work exhibited, artists have been required to avoid ‘controversial’ subject-matters (Cooke 2007, p. 9). It is after a severe economic crisis in the first decade of Hafiz’s rule that public institutions progressively relied on sanctions on artists, bringing to the disappearance of the peaceful relationship between artists and state (Boëx 2011, p. 140; Becker 2005, p. 79). Under Hafiz, the state acted as the only sponsor and main educator in the arts on a Soviet model (Cooke 2007, p. 21), benefitting only those who accepted the boundaries specified by the Ministry of Information, and against which a ‘transgressive counter culture’ developed (Weeden 2015, p. 89). This resulted from the production of cartoons, plays, films, and novels in which ‘dissident’ artists engaged for decades. One of my informants pointed out that ‘symbolic political messages were already in artworks, but they might have been ignored or not understood by everyone’, citing Ali Ferzat’s work6. In general, it can be said that a claim to ‘political neutrality’ and a tendency towards abstraction and symbolism is predominant in the visual arts. In order to understand my informants’ positionality, I adopt Abbas’ approach in considering aspects such as ‘the self-judgment of the artist’, ‘their production’, and their ‘political behaviour’ (Abbas 2005, p. 13). Indeed, I mainly focus on the discursive, rather than aesthetic, aspect of art.

It is with the 2011 uprisings that there has been an explosion of ‘revolutionary cultural production’ in Syria (Cooke 2016, p. 8). The protests are seen as the culmination of perceived oppression under Assad, use of physical violence by security forces against civilians, and silencing of civil rights (Hokayem 2013; Sottimano 2016, p. 458). They also need to be contextualized within wider regional tensions: The rise of political Islamism, waves of popular discontent manifested in the Arab Spring across the Middle East, economic deprivation, struggle for regional dominance between Iran and other Arab states, etc. (Foley 2013, p. 33; Abbas 2014, p. 52). Syrian society can be said to be divided between those opposing the regime—Sunni Muslims, members of minorities, working classes, rural populations, civilians who took up arms (Free Syrian Army)—and those wanting to preserve it or who feared alternatives, including ‘crony capitalists’, urban government employees, and other members of minorities (Pearlman 2017, p. xlii; Foley 2013, p. 42).

Not all artists got involved in the protests, from those few who came out publicly to back the President7, to those who kept quiet, as they did not believe meaningful changes would have been achieved, to those who, like Jaber, decided ‘not to go in the streets’ in order to protect their families. His story is emblematic, for he first engaged in art when the revolution started:

Jaber realized his first series, ‘Wounds’ (2012), of shots depicting blood-red and black silhouettes of figures in motion, represented ‘people fighting bravely for their freedom’. In the same spirit, he produced in secret the series ‘The Resurrection’ (2014) (Figure 4), where civil society members hold the official newspaper (Al-Ba’ath) on which each wrote something against the regime, in the style of ‘Facebook status’.In such circumstances everybody has to give something to the people: the doctor will help the wounded, the baker make bread for whoever needs it, and the artist produce to report this history.

Figure 4.

Detail from ‘The Resurrection’ (2014) by Jaber. (Printed on Cotton Rag Fine Art Archival paper.) London, UK: British Museum. Photograph by the author.

Active anti-regime artists received threats, had to remain silent or were forced into exile (Boëx 2013, p. 15)—among them, Hasan, who joined protests since the beginning, and was arrested in 2011 and tortured. Once out of prison, he fled illegally to England. He later learnt that his house had been raided by the police, and his son arrested.

As for Ibrahim’s involvement in the protests, despite being already outside Syria, he devised a way to contribute to ‘the revolution’: Graffiti, such as the banner featuring faces of martyrs exhibited in Rich Mix, London (2013). Online platforms allowed him to circulate stencils for protesters.

In the case of Tammam, he managed to overcome a major logistical issue—the destruction of his studio in Damascus—by shifting from painting to digital media. The latter has become increasingly popular in ‘post-Arab Spring countries’, employed by artists such as Khalil Younes and Fares Cachoux (Al-Shami 2016). Tammam’s ‘Freedom Graffiti’ print (2013), part of the ‘Syrian Museum’ series, went viral on social media (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Tammam’s ‘Freedom Graffity’ (2013). (Digital Print.) Used by permission of the artist.

Such emotional intensity caused by this turbulent moment induced artists to shift the content of their art. Anti-regime voices received most attention in Western media, being celebrated as ‘defiant art’, having a misleading impact on the ways in which all art from Syria is seen. Since then, the ‘emerging Syrian art-scene’ has been bustling outside Syria to a greater extent: A profound shift occurred from a neoliberalization of the art market supported by the regime, to a concomitant anti-regime politicization and commercialization of artists’ works abroad. I will now explore how these developments and the experience of displacement have informed my informants’ subjectivities.

3.3. Othering ‘the Syrian’ before ‘the Artist’

Flipping through art catalogues with Tarek and Ammar at P21 gallery in London, I observed I had not been able to find sources about visual art from Syria, and they explained that the lack of such books is a reflection of the absence of a unified Syrian cultural elite.

We met there as they wanted to show me where the first collective exhibition in which they participated took place, back in 2013. Tarek was lead curator of #WithoutWords: Emerging Syrian artists, for which artworks were smuggled out of Syria, by artists based abroad or still living there, many of whom were persecuted—Ali Ferzat and the Lens Young Collective. A more recent occasion where their works were shown was the exhibition ‘Art of Resilience’ at the US Embassy in London (January 2017). The organization Mosaic, together with the Asfari Foundation, played a major role in supporting Syrian artists in London, hosting public auctions of artworks, and sharing funds raised between artists and activity of aid relief. Since 2011, similar initiatives have been put in place, such as those by the Shubbak festival, International Alert and the British Red Cross. The general public’s attention to ‘Syrian art’ might have also been stimulated by art-therapy projects set up by charities such as the London Art Therapy Centre, Flourish Foundation, and Refugee Week. However, Tarek and Ammar noted that many organizations ‘aren’t active at the moment’, and Ibrahim feels that Mosaic ‘became one of those charities after the money’. Further, the London branch of Ayyam gallery closed down soon after its opening in 2013, because of ‘the absence of fertile grounds in Europe for Middle Eastern art’, as remarked by one of my informants.

My informants invited me to reflect on how media, public, and art collectors’ attention to art produced by Syrian artists has declined, In fact, most articles and interviews of Syrian artists date back to the war’s early years (2011–2014). I am going to explore reasons behind the initial enthusiasm for the ‘phenomenon of Syrian art’, in order to contextualize its fading appeal (and production). I look at discourses and practices that surround these artists and are beyond their control. I problematize the category of ‘Syrian artist’ conflated within that of ‘Middle Eastern or Arab’. Homogenizing narratives weigh on non-Western artists in general yet evolve from a discrimination based on ‘ethnicity’ to a more subtle form of ‘othering’ because of changing geopolitical dynamics. This involves a shift from ‘a culturally exotic other’ to ‘a politically exotic other supposed to be either exiled from or critical about his/her country of origin’ (Araeen et al. 2002, p. 333). I argue that such essentializing tendencies are fostered precisely by Syrian artists’ ‘universalizing’ discourses about their art.

It is useful to adopt the notion of ‘artworld’ as imbricated networks involving differently positioned actors, in order to study ‘the discursive practices that determine who will find a place within it’ (Harris 2012b, p. 153). Despite celebrated ‘pluralization’ of the artworld in terms of origin of its actors (Elkins et al. 2010, p. 14; Schultheis et al. 2016, p. 18), access to it seems to depend on artists’ ‘positionality vis-à-vis various hegemonies and ideologies at play, regionally and internationally’ (Toukan 2013, p. 75). That is, the political situation in Syria, Western countries’ position in it, and their historical presence in the region determine the ways in which Syrian artists’ work is interpreted. In other words, ‘the particularities of place’ (Harris 2012b, p. 16) do not simply have a geographical dimension and still determine patterns of inclusion/exclusion in the artworld, whose centers of gravity remain Western art institutions/metropolis. Despite growing interest for non-Western forms of contemporary art such as African, Middle Eastern, and Chinese, these artists remain powerless players. On the one hand, ‘art always takes place within a national situation’ in terms of audiences, museums, and parameters within which it can take place (Elkins 2007, p. 16). During our conversation at Something Gallery, where Hasan’s works were exhibited, the curator expressed her discomfort with the Scottish Cultural Secretary’s statement that ‘artists don’t have to be close to government, they just have to have a common understanding of what the country wants’ (Wade 2017). Moreover, artists often choose to give a sense of their ‘localised’ identity in their work, and yet, a ‘methodological nationalism’ cannot be adopted to the study of the art-scape in which they operate, since it has become an increasingly international enterprise (Belting and Buddensieg 2009, p. 10; Gardner and Green 2013).

Whenever my informants perceive that their art is dismissed as ‘Syrian’, they feel their talent is overlooked. They are aware that the ‘straitjacket of geography and prescribed identities’ (Carver 2006) weighing on them comes with imaginations about Syria and the wider region via association with war and displacement, as expressed by Ibrahim. Based in the UK for the past fifteen years, in addition to his involvement in art-activism, Ibrahim works fulltime as graphic designer for Alaraby TV Network and is also a curator. In London, ‘there have been attempts to create a network of Syrian artists’ and to find more platforms for those scattered throughout Europe. Ibrahim is one of the collaborators of ‘Syria Speaks: Art and Activism from the front line’ (2014), committed to bringing to the fore the voices of artists and musicians denouncing the ‘untold bloodshed’ taking place in Syria, who cannot emerge ‘because of politics’. Moreover, as I was able to grasp in my conversation with Gregory—the Lebanese art historian—investment in Syrian art has collapsed within the region itself, because ‘Arab states are in deep political crises’.

These observations refer to those ideological frameworks shaping selection and evaluation of artworks, which are never neutral (Winegar 2008b, p. 652). Exhibiting and museum practices have a historical and institutional dimension, often shaping audiences’ perceptions (Karp and Lavine 1991, p. 12).

Before exploring this further, a note of contextualization on such debates on the status of ‘minority arts’ in the international artworld is necessary. In the 1980s, many took issue with the exclusion of non-Western artists and the neglect of their contribution to ‘mainstream developments’ (Araeen et al. 2002, p. 333). These sensibilities seek to ‘retrace modern art in other parts of the world’ (Elkins 2007, p. 21) and are part of wider efforts in academia to disentangle from hegemonic interpretative tools of historicism and Eurocentrism (Chakrabarty 2000, 2009). In anthropology, there has been a shift from a view of art objects as ‘emblems of holistic cultures’, unlocking the worldview of so-called ‘ethnic’ communities (Kaur and Dave-Mukherji 2014, p. 7; Welsch 2004, p. 403), to the study of individual artists as legitimate subjects of inquiry, a path initiated by Schneider (1996, p. 184). Appadurai argues that early approaches entailed the ‘metonymic freezing’ of natives by their places (Appadurai 1988, p. 36). Instead, I hope to demonstrate that ‘taking seriously individuality and idiosyncratic discourses’ does not imply neglecting social processes in which artists are embedded (Schneider 1996, p. 188). A sound anthropological analytical strategy goes beyond the modernist myth of the hyper-subjectivity of the artistic genius, appreciating that artists never operate in isolation from economic and sociopolitical domains (Krauss 1986, p. 4; Langton and Papastergiadis 2003, p. 13). However, the art establishment often undermines individual talent of minority-artists, expected to reveal elements of cultural ‘distinctiveness’ (Harris 2012b, p. 162; Belting and Buddensieg 2009, p. 40). As noted by Araeen et al. (2002, p. 340), founder of the ‘Third Text’ journal, and by Taylor (1994), the system of exclusions at the basis of ‘modern art’ has been refined by multiculturalism, centered around the importance of recognizing ‘cultural others’, still based on an assimilationist logic, and concealed by a universalist frame (Araeen et al. 2002).

For Syrian/Middle Eastern artists forms of ‘othering’ are structured around orientalist assumptions:

Edward Said famously conceptualized ‘Orientalism’ as the positioning of ‘the Orient’ as backwards because of Western imperialism in these territories (1978). This phenomenon seems to have escalated in recent years. According to Gregory, since 9/11 and the ‘war on terror’, ‘the whole world became interested in Middle Eastern art practices’ (Buchakjian 2012, p. 40). Art agents, pushed by funding bodies, looked for intellectual/artistic sources as containers of knowledge about the Arab world. Concurrently, Gulf States started investing in art, creating ‘a contradictory situation: on one side, Arabs associated with terrorists, and on the other, Arabs with money’.Tarek: If the Arabic culture was valued, its art would also be valued … But it’s still debated whether it’s art or not. Fortunately, they now teach this in schools in Europe.

I suggest that the recent exhibition ‘Age of Terror: Art since 9/11’ at the IWM in London reproduces these discourses since it puts together a collection of works by Middle Eastern artists highlighting controversial feelings post-9/11 in the region. I observed a similar tendency to group artists from the diverse Arab region in the exhibition ‘Living Histories. Recent acquisitions of works on paper by contemporary Arab artists’ in Room 34, ‘The Islamic World’ of the British Museum. The series ‘Resurrection’ by Jaber, Issam’s installation ‘Dark Water, Burning World’ and a drawing by Houmam Al-Sayed (2009) feature in it. The issue at play in putting this exhibition of contemporary artists inside the Islamic art section is the conflation of region, culture, history, and religion (Winegar 2008b, p. 655). Sharing the same birthplace or having a name that identifies them ‘as having hailed’ from a place is not simply a nominalist definition (Withey 2013, p. 16). Gupta and Ferguson remind us that all associations of place, people, and culture are ‘social and historical creations to be explained, not given natural facts’ (Gupta and Ferguson 1997, p. 4). In this setting, Winegar would argue, a discontinuum is established between a glorious, past Islamic civilization and a present status of decay. However, ‘Arabic’ and ‘Islamic’ are not to be conflated, since the Middle East has contested borders, subsuming various ethnic/religious groups (Roudi-Fahimi and Kent 2007). Critically, I argue that a shift in focus from ‘ethnicity’ and ‘location’ to ‘national identity’ and ‘politics’ as criterion for approaching ‘Arab art’ has occurred; that is, from ‘ethnographic’ Islamic calligraphy to works dealing with current politics. As my informants invited me to reflect, qualifying art in this way is problematic:

As a Western researcher dealing with artists originally from the Middle East, I have approached my informants with the expectation of finding ‘counter-hegemonic statements’ in their art: This is not a completely unfounded presumption if one looks at Syria’s artistic history, especially post-2011 ‘revolutionary art’. However, when researching art produced in conditions of crisis, during wartime or under siege, celebrating it as ‘anti-powers resistance’ involves predetermining its dramatic dimensions (Spyer in Kaur and Dave-Mukherji 2014, p. 73; Boullata 2004, p. 75), assuming that all artists are against the regime. The tendency to give prominence to sociopolitical conditions determining artists’ production involves making epistemological statements about their capacity to overcome them (Marcus and Myers 1995, p. 5). The imposition of such a frame comes from the fact that Syria as a location is imbued with historical/political content.Tammam: I would like to have more sponsors, but not because of my nationality. I want to be seen as an artist and Syrian, not because I’m a refugee who’s able to paint.

As a reply to my first email, Hrair said he did not want to be categorized as Syrian artist, as he is ‘not committed to the Syrian art-scene (…) the only thing we have in common is where we’re from’. Others insisted I would make sure their name was not going to be ‘associated’ to that of others, while featuring in the same research. They all took issue with the ‘refugee moniker’ defining them. I therefore appreciated the arbitrariness of the ‘exiled Syrian artists’ category, unsettling my initial research focus, which shifted to whether and how displaced artists from Syria reflect on the conflict through their creative practices and how they react to the label used to describe them. My expectation of finding a ‘diasporic community’ is to be related to romanticized online accounts of the ‘Syrian artistic diaspora’. These refer to artists–activists like Ibrahim and Dima, committed to promoting change through human-rights organizations, opposition groups, etc. (Qayyum 2011, p. 8; Chaudhary and Moss 2016, p. 15), or to the smaller, transnational network of more established artists—including Tammam, Houmam, Jaber, and Ammar Abd Rabbo—whose works are brought together by internationally travelling exhibitions. As for London, however, I found a fragmented, non-existent Syrian art-scene: My informants were barely able to mention names of other Syrian artists living there. I have come under the impression that in Lebanon, France, and Germany, relations among Syrian artists are more settled. Yet, Tammam, completing a fellowship at the Institute for Advanced Study in Delmonhost, expressed his uneasiness with the ‘superficial trend of Syrian art’ in Germany. Similarly, Houmam—based in Beirut, ‘the de facto capital of the Syrian contemporary art-scene’ (Brownell 2014)—does not consider himself ‘a fun of local art circles’, including the Syrian one, which remains separate.

Different factors explain the lack of collaborations between artists—competition, diverging approaches to art, institutional, financial or personal issues, as well as political ones, including migration policies. My initial assumption can be said to reproduce social scientists’ tendency to overstate internal homogeneity of transnational communities (Wimmer and Glick-Schiller 2002, p. 233). Indeed, a ‘methodological nationalism’ has affected the study of migrants, including ‘diaspora artists’, approached primarily in relation to their homeland (Wimmer and Glick-Schiller 2002, p. 228; Anthias 1998; Deebi 2012, p. 12). Exhibitions such as ‘Word into art: Artists of the modern Middle East’ (Porter 2006), and ‘Unveiled: New art from the Middle East’ (Farjam 2009) presented works by Egyptian, Iranian, Iraqi, Palestinian, Lebanese, and (proportionally less) Syrian artists as unitary phenomena. ‘Diaspora as creative space’ essentializes artists. The term ‘transmigrants’ captures more fully the complexity of their accommodation and resistance to hegemonic contexts (Glick-Schiller et al. 1992), as it is rooted in a conceptualization of identity as intersectional, ‘mobile and unstable relation of difference’ (Gupta and Ferguson 1997, p. 13; Anthias 1998), which resonates with my informants’, who attempt to resist imposed categories, emphasizing their flexible disposition. This has implications for methods used and forms of knowledge produced.

3.4. The Discursive Strategy of ‘Universalism’

Through my fieldwork, I was able to grasp that the Orientalism weighing on Middle Eastern artists is obscured, as Withey (2013) argues, by the predominant discourse of universalism, embraced by Syrian artists, who present themselves as mediators as a ‘universal humanism’, and by Western viewers and curators, but with different motivations. The latter promote Syrian artists as universal because of their capacity to criticize their ‘troubled, sectarian society’ and to embrace ‘Western values’ such as cosmopolitanism, respect for human rights, etc. (Groys 2008, p. 181). Art critics seem to expect Syrian artists’ work to ‘have a political edge’, as much as contemporary Tibetan artists are expected to reproduce a narrative on Chinese Colonialism (Harris 2012b, p. 159). They are, however, required to express these issues in a visual vocabulary catered to the market: Conceptual art. I had the chance to talk with a curator, Rebecca, who reproduced this narrative:

On the gallery’s website, Hasan’s canvases are defined as ‘visually, culturally and historically unique’, communicating a ‘quiet sense of yearning’. Rebecca was attracted by Hasan’s art as she could ‘feel happy memories of the Middle East’ despite the trauma experienced, making his art ‘universally appealing’ (Figure 6).The West wants Middle Eastern artists, but the region is so unstable that the plan of bringing Western art-making there isn’t happening. Its art is becoming so precious because it survives conflict.

Figure 6.

In September 2017, Hasan titled this painting ‘Friends’ (n.d.), but recently re-posted it on Facebook as ‘Agony in the Streets’, making me wonder whether Rebecca’s description would have changed. (Acrylic on canvas.). Used by permission of the artist.

Whenever artists like Hasan are thought to transmit universal messages, or the uniqueness of their ‘culturally-specific styles’ is emphasized, a discourse of ‘othering’ is reproduced. On the other hand, I argue that the way in which my informants use such a ‘universalist narrative’ differs, because they see the themes they depict as transcending politics. Their way of including themselves within a universal category of artists through an emphasis on individualism is a ‘creative strategy’ (Harris 2012a, p. 234) to resist imposition of imagined constructions of ‘Syrianness’. And while my informants seek to achieve global visibility, they do not necessarily emulate ‘Western mainstream’. Moreover, they are aware that ‘difference has become marketable’ and they can actively ‘perform ethnicity’ and ‘export themselves’ (Mosquera in Langton and Papastergiadis 2003, p. 19; Kaur and Dave-Mukherji 2014, p. 10). Indeed, the fragile human figure recurring in the visual arts in Syria, as much as ‘the refugee’, entrapped Syrians and their destroyed cities, come to represent the very ‘symbolic capital’, an ‘iconography of suffering’ that makes them aesthetically recognizable to curators.

Some artists—like Issam, in the UK since the 1990s—embrace the ‘Syrian identification’, yet maintaining an ‘authentic’ stance:

Who needs to learn how to ‘digest’ the suffering caused by war? Is it Western audiences, not familiar to these realities, or Syrians themselves? Issam made this observation during his talk at King’s College (October 2017). Ammar expressed similar thoughts:Because I’m from that part of the world, everything’s charged differently. Sometimes I cannot escape it. But that’s my landscape and my job as artist is to present it in a way that can be digested.

For Issam and Ammar, it is about accepting ‘the inevitability of exile art to be political’ (Homsey 2016, p. 8), that is, the diaspora position. There seems to be a general understanding that Syrian artists are the most entitled, by virtue of their origin, to do so. These perceptions are to be reconnected to controversies around instances of ‘cultural appropriation’ in the arts, particularly when Western artists adopt styles/themes considered to appertain to another ‘culture’8. Arguably, in some cases, artists unintentionally ‘bestow a status as others on them’ (Schneider 1996, p. 184), because it is precisely what they think makes them ‘universal’—the theme of human suffering—that marks them as ‘particular’.Every piece of art is about politics. Syria is always on my mind, and as creative person I must, and I have the power to, do something for Syrians there.

In his book, Gregory argues that ‘Middle Eastern artists’ ‘shift to the domestic is a manifestation of a renewed Orientalism’, with the difference that ‘local artists have replaced European Orientalists in producing the iconography’ (Buchakjian 2012, p. 79). In other words, my informants might be self-ascribing the category of ‘other’ simply by referring to the situation in Syria. Critically, they might not be conscious of it, because ‘it’s the way in which the West mediatizes their work that politicises it’, as Gregory observed. In artists’ view, such ‘politicisation’ is perceived as a ‘trivialisation’, preventing attribution of transformative capacities to their art (Jelinek 2013, p. 10). Because of this context, my informants differentiate their work from, in Gregory’s words, ‘a strategic production since 2011, that’s not a deep reflection on what’s going on’. One may recall predominant understandings of art as ‘socially relevant’, ‘authentic’ practice. In 2011, Abdelke urged younger generations of artists to be skeptical of the new market’s ‘financial attractions’, because the artworks promoted do not reflect the rich Syrian visual heritage (Takieddine 2011, p. 60).

Dima is critical of the corporate-oriented mentality around which ‘Western art agencies’, particularly in the UK, are structured, which she learned about during her studies at Kings College (London). Such perceived limitations brought Dima to move back to Lebanon, where working as free-lancer artist is more feasible; she is a ‘clown performer’ for the initiative ‘Clown me in’, committed to providing relief to disadvantaged communities. As it emerged from my interviews, the greatest challenge for artists is to ‘emancipate themselves from big players of the global art-market’ (Schultheis et al. 2016, p. 256). Moreover, as noted by Tarek, works for exhibitions are often selected dependently on curators’ personal preferences/contacts, ‘being treated as commodities’. Tarek’s conception of art resonates with that of older generations, as he developed his approach in Syria before the ‘booming’. This concern that adjusting one’s choices to the market’s demands might compromise ‘authenticity’ of the sentiments inspiring artworks is shared by Syrian artists (Shannon 2005, p. 378), as well as in the Western world.

At the same time, artists are not always able to be in control of the ways in which their artworks circulate in the ‘already saturated visual-discursive space’ (Malmvig 2016, p. 264). Hrair recounted that in 2011 journalists from the Netherlands and the US contacted him to post images from his series ‘Execution Squares’ on newspapers, ‘relating them to the conflict, as critique of the ongoing killings, while it has nothing to do with that because Syria has become an incomparable execution square’. Hrair realized the series in 2008. It comprises photographs of squares in Aleppo, Latakia and Damascus, taken at dawn, when people used to be hanged because of civil punishment. He came up with this project as a consequence of a tormenting vision: At the age of twelve, he saw ‘three naked hanged bodies in the middle of a square wrapped with sheets that had their name and crime committed written on them’ (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

From Hrair’s ‘Execution Squares’ (2008). (Archival inkjet print). Used by permission of the artist.

Similarly, Tammam laments mediatic manipulations of his biography, such as his presumed imprisonment and escape from Syria. While he has the ‘refugee’ status, Tammam ‘travelled normally by plane’ when leaving Damascus in 2011. For this reason, he refused to be interviewed by anyone except me in the past months, as I was not doing a ‘journalistic report’. The context to which Hrair (Figure 8) and Tammam refer is exemplified by another instance—the exhibition ‘Syria: a conflict explored’, which went on in IWM venues across the UK in 2017—where, according to Hrair, the conflict is ‘fetishized’. This is because photographs exhibited were taken by a Russian photographer ‘who probably had easy access to Aleppo’ and ‘made them look dramatic’. He was also struck by the organization of a reception ‘with people drinking all dressed up, a musician playing from the sound of bombs, while an entire nation is suffering’.

Figure 8.

Hrair at the Tate Gallery, London. Photographs by the author.

3.5. Making Compromises

When navigating such complex space of the artworld, specifically in Europe, not everyone can choose to opt out from orientalist depictions. Artists may realize that ‘collectivizing’ their art may give them more chances to ‘emerge’, thus limiting to the discursive sphere contestation of imposed localization. The kind of identity bringing them together is a universal one, as the suffering they illustrate is an affective need rather than a political statement. However, as Harris (2006, p. 710) notes, rather than being free agents travelling internationally, artists’ physical mobility is often limited: As Dima was able to grasp from her short staying in London, Syrian artists operate within ‘strong Arab connections’ that remain a separate circuit. Emplacing oneself in the competitive London art-scene is challenging, as Tarek explained:

Tarek has several unsold paintings, many of which he had to leave behind ‘everywhere he moved in the UK’. Similarly, during his first months in London, Hasan used to live in a tiny flat, with walls covered with canvases he managed to bring with him from Syria. Some of my informants have concurrently other jobs, and some donated works to charities.We’re going to a warehouse where my paintings are stored. It’s not the appropriate place where to keep them. Their journey is a reflection of the condition of art from Syria: if it was valued, it wouldn’t be in a food storage.

As seen, these artists’ choices are not only driven by economic preoccupations, but also ethical concerns connected to representation of war, uneasiness with external categorization as ‘Syrian’, and commodification of artworks required by the market. I have also discussed how my informants discursively and practically mediate between universality—i.e., make their works accessible to international audiences—and particularity—representing a ‘local situation’ that is currently a war-zone. Yet, identification as ‘Syrian’ is not necessarily their ‘curse’ but may also represent their ‘salvation’, allowing some to find a place in the market.

4. Epilogue—Inhabiting Uncertainty

Now in the eighth year of the conflict, the shared impulse of responding to it with urgency seems to have vanished, as reflected in artworks produced and broader resolutions adopted by artists from Syria (Malmvig 2016, p. 258). Most of my informants are now working on new projects. Jaber realized the series ‘Border-lines’ in 2016 (Figure 9):

This abandonment of notions of ‘national belonging’ seems common to my informants and translates into indifference to changing location, to be related to the discourse of ‘universalism’ that they embrace. Hasan and Tarek articulated a tension between a ‘cosmopolitan stance’ and emotional bonds to homeland:Maybe it’s a self-defense-mechanism, but seeing my country destroyed and people killing each other for nations, I don’t believe in borders anymore. It’s surreal that a Syrian cannot escape war because of a paperbook.

H: ‘In spite of jail and persecution, I still feel attached to Syria. But I wasn’t angry when I came here, I adapted easily. I go to Costa to have coffee, as I used to do in Syria—it’s funny, it reminds me of home.’

I could also perceive a shared sense of fear that the ‘Syrian culture’ would disappear. When entering the warehouse where Tarek’s paintings are stored, I noticed a display-cabinet with food products exported from Syria. He suggested taking a photograph, as if these represented ‘relics’ of a lost past (Figure 10).T: ‘This feeling of living in exile will always stay with me. But you recreate your identity abroad, I feel more cosmopolitan. Of course everyone’s attached to family and friends, but in terms of country, I’ve abandoned it to live in peace.’

Figure 9.

Jaber’s ‘Nationalism 1’ (a) and ‘Survival 13’ (b) (2016). ‘Border-lines’. (Printed on cotton rag fine art archival paper.) Used by permission of the artist.

Figure 10.

Display cabinet with Syrian goods. Photograph by the author.

My informants expressed disillusionment in relation to Syria’s future. As it stands now, the multidimensional character of conflict seems to prevent taking any collective action that will guarantee ceasefire and rehabilitation (Vignal 2012; Heydemann 2013, p. 71). Houmam claimed that everyone has stopped believing in anything, from politics to religion: ‘maybe only in fifty years, when I’m not going to be there, things might change’. As a result, he shifted his aesthetic focus from ‘citizen zero’ to ‘citizen −1, −2 … since we’re below average (of respect of human rights)’.

Hrair described the status in which Syrians find themselves as ‘the opposite of hope, the condition of having nothing to hold onto’. In his video work ‘Horizon’ (2016) (Figure 11), he traces refugees’ routes crossing the Mediterranean from Turkey to Greece, noting that ‘only uncertainty accompanies them’.

Figure 11.

From Hrair’s ‘Horizon’ (2016). (Two channel video, HD.) Used by permission of the artist.

On the other hand, activists like Ibrahim and Dima still encourage mobilization, especially on social media—for instance, sustaining the #SaveGouta Campaign after attacks by government forces on civilians in February 2018. Ammar, Tarek, Jaber, and Tammam are also active, sharing posts related to the conflict or links for humanitarian donations, yet with less frequency. Despite this, a belief in the power of artistic creativity persists, to provide resilience to Syrians, but also to influence wider audiences’ perspectives.

Syrians’ condition resonates with Palestinians’ because of their experience of prolonged displacement (Charles and Denman 2013). One may recall Palestinian poet Darwish’s characterization of their status as sustained by an ‘incurable malady called hope’ (Boullata 2004, p. 82). Tammam phrased it clearly: ‘Syrians are refugees now’. And how does their faith get configured in their own imagination, that of receiving countries, and of Syrian authorities? I raise the same open question as for future prospects for contemporary Syrian artists. As seen, their place has depended on specific imaginations of war and exile, encapsulated in the figure of a ‘diaspora artist’. As more and more artists are based abroad and possibilities of working in Syria are almost null, it can be said that the Syrian art-scene has mobilized outside the country’s borders. It is a crucial moment of uncertainty not only for artists, curators, and collectors, but also art-historians and academics, and I invite further reflection on what the future might bring.

As a final consideration, I would like to further reflect on my role of researcher. I have been encouraged by my informants, especially Ammar, to ‘initiate a network of Syrian artists in London’, ‘transfer my knowledge into practice’. I am committed to the wider purpose of undoing the stereotypes that artists lament. As Van Willigen notes, larger numbers of anthropologists are working for government agencies and other organizations, with the objective of having an impact through policy-making (Van Willigen 2002, p. 3). As for the artistic realm, ‘anthropologically informed visual practices’ are increasingly used as ‘social interventions’ that unsettle mainstream representational practices by creating platforms for one’s informants to represent their experiences (Pink 2009). In the near future, I am planning to collaborate with enterprises committed to promoting artists living in conflict zones such as today’s Syria, in order to embrace Ammar’s invitation to enable the application of academic research to artists’ practical use.

Funding

This research received funding to cover part of the fieldwork from Green Templeton College, Oxford University.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Interview and Topic Guide

I used this general interview and topic guide for all the interviews I carried out. This set of questions provided me with guidance throughout conversations with artists, but each took a different direction as I allowed much space for my informants to express themselves and for their perspectives to unfold. In fact, they frequently brought up new themes themselves, and I also prepared more specific questions concerning each artist’s work.

Biography and Subjectivity

- I would like to know about your personal development as an artist and what brought you to focus on certain themes rather than others [specific artworks cited in this respect].

- Do you recreate specific moments of your past in your works? Do you tell a story about your own subjectivity?

- What are your artistic influences?

- When did you move here [London/France/Germany/Lebanon/Qatar]? How is your life as artist different compared to when you were in Syria?

Art and the Representation of Conflict

- I am interested in the relationship between art and the outside world. In your perspective, what is the role of art in society, and in particular in relation to the current crisis in Syria?

- How was your artistic production before the conflict? Has it changed since then, and if so, in what ways?

- What are your thoughts on the relationship between the production of art, resilience from conflict, and its representation? Can art foster resilience from conflict?

- As for the politics of representation around your works, how do you posit your art within the broader political and social framework of crisis and activism in Syria? I am referring in particular to the recently published book ‘Syria Speaks’, are you familiar with it?

- What would you like to communicate with your artworks? What are the main themes you deal with?

- Do you aim at giving a political commentary or simply representing reality, offering your distanced reflection on unfolding events?

- Have you encountered instances of external politicization? I mean, specific expectations by audiences or curators concerning the content of your work. Have you had to deal with ‘wrong’ interpretations that emphasize your political positioning in relation to what is happening in Syria? I would like to explore your take on this politicization lamented by other Syrian artists

- Do you agree that there is a particular social and political logic in being an artist coming from Syria at this particular point in time?

Doing Art in Syria versus Abroad

- Exhibitions often promote ‘Syrian artists’ as a group, and there is a general trend in the media to talk about ‘Syrian art’. Do you feel part of this category?

- Do you feel like the tendency to group Syrian artists in a single category has brought many to isolate and take a different direction in their work?

- Can we talk of ‘Syrian art’? Is there a style unique to Syrian artists that developed historically?

- What is your experience of the art-scene in Syria? How has it changed with the introduction of an art market?

- How is your life as an artist here like in comparison to Syria? How is your routine like? Where do you work? Are there good opportunities for artists?

- Do you engage in exchanges or work in collaboration with other Syrian artists here?

- Do you see your work related to that others treating similar themes? I can mention the names of the other artists I am interviewing for this research; do you know them or have you come across their work?

- Can we talk of a transnational network of Syrian artists, as the media does?

- What are the main artistic hubs for Syrian artists today?

- How do you see your future as a Syrian artist and that of your colleagues? How is it connected to Syria’s future?

- What is your relation to Syria now? Do you have hope for your country?

References

- Abbas, Hasan. 2005. Les artistes peintres syriens et la politique. Collections Électroniques de l’Ifpo. Livres en Ligne des Presses de l’Institut Français du Proche-Orient 22: 233–47. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, Hasan. 2014. Between the cultures of sectarianism and citizenship. In Syria Speaks: Art and Culture from the Frontline. Edited by Malu Halasa, Zaher Omareen and Nawara Mahfoud. London: Saqi. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khalidi, Ghazi. 1990. What the Arabs brought to Europe. (Oil on Canvas.). Available online: https://books.openedition.org/ifpo/564?lang=en (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Al-Shami, Leila. 2016. Emerging from the Kingdom of Silence. Beyond Institutions in Revolutionary Syria. Ibraaz. Available online: https://www.ibraaz.org/publications/75 (accessed on 4 January 2018).

- Anderson, Brooke, and Don Duncan. 2010. Contemporary Middle East. Wall Street Journal. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB127378397101791153 (accessed on 29 November 2017).

- Anthias, Floya. 1998. Evaluating ‘diaspora’: Beyond ethnicity? Sociology 32: 557–80. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1988. Putting hierarchy in its place. Cultural Anthropology 3: 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araeen, Rasheed, Sean Cubitt, and Ziauddin Sardar, eds. 2002. The Third Text Reader: On Art, Culture, and Theory. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Carmen. 2005. Strategies of Power Consolidation in Syria under Bashar al-Asad: Modernizing Control over Resources. The Arab Studies Journal 13: 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- Belting, Hans, and Andrea Buddensieg. 2009. The Global Art World. Audiences, Markets, and Museums. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H. Russell. 2017. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Bevan, Sara. 2015. Art from Contemporary Conflict. London: Imperial War Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Boëx, Cécile. 2011. The end of the state monopoly over culture: Toward the commodification of cultural and artistic production. Middle East Critique 20: 139–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boëx, Cécile. 2013. Mobilisations d’artistes dans le mouvement de révolte en Syrie: Modes d’action et limites de l’engagement. In Devenir Révolutionnaires. Au Cœur des Révoltes Arabes. Paris: Armand Colin, pp. 87–112. [Google Scholar]

- Boullata, Kamal. 2004. Art under the Siege. Journal of Palestine Studies 33: 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, Joanna. 2017. War and Art. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell, Ginanne. 2014. Syrian Artists Set up Base in Beirut. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/19/arts/international/syrian-artists-set-up-base-in-beirut.html (accessed on 21 January 2018).

- Buchakjian, Gregory. 2012. War and Other Impossible Possibilities: Thoughts on Arab History and Contemporary Art. Beirut: Alarm Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Candea, Matei. 2007. Arbitrary locations: In defence of the bounded field-site. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 13: 167–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, Antonia. 2006. Don’t Force Middle Eastern Artists into an Identity Straitjacket. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2006/sep/06/arts.visualarts (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Chakrabarty, D. 2000. Subaltern studies and postcolonial historiography. Nepantla: Views from South 1: 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2009. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, Lorraine, and Kate Denman. 2013. Syrian and Palestinian Syrian refugees in Lebanon: The plight of women and children. Journal of International Women’s Studies 14: 96. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, Ali R., and Dana M. Moss. 2016. Triadic Political Opportunity Structures: Re-conceptualising Immigrant Transnational Politics. Working Paper 129. Oxford: International Migration Institute (IMI). [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, James. 1997. Diasporas. In Routes: Travel and Translation in the late Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 244–77. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Robin. 2008. Global Diasporas: An Introduction, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, Miriam. 2007. Dissident Syria: Making Oppositional Arts Official. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, Miriam. 2016. Dancing in Damascus: Creativity, Resilience, and the Syrian Revolution. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- De Cesari, Chiara. 2012. Anticipatory Representation: Building the Palestinian Nation (-State) through Artistic Performance. Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 12: 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deebi, Aissa. 2012. Who I Am, Where I Come from, and Where I Am Going: A Critical Study of Arab Diaspora as Creative Space. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK. [Google Scholar]

- DP News. 2010. Contemporary Middle East. DP News. Available online: http://www.dp-news.com/en/detail.aspx?articleid=38991 (accessed on 6 December 2017).

- Duclos, Diane. 2017. When ethnography does not rhyme with anonymity: Reflections on name disclosure, self-censorship and storytelling. Ethnography. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, Don. 2010. Contemporary art from Syria Finds Favour with International Buyers. DW. Available online: http://www.dw.com/en/contemporary-art-from-syria-finds-favor-with-international-buyers/a-5493328 (accessed on 15 November 2017).

- Elkins, James, ed. 2007. Is Art History Global? Abingdon: Taylor & Francis, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins, James, Zhivka Valiavicharska, and Alice Kim. 2010. Art and Globalization. University Park: Penn State Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Farjam, Lisa. 2009. Unveiled: New Art from the Middle East. London: Booth-Clibborn Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, Sean. 2013. When life imitates art: The Arab Spring, the Middle East, and the modern world. Alternatives: Turkish Journal of International Relations 12: 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, Anthony, and Green Green. 2013. Biennials of the South on the Edges of the Global. Third Text 27: 442–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellner, David N. 2012. Uncomfortable antinomies: Going beyond methodological nationalism in social and cultural anthropology. In Beyond Methodological Nationalism. London: Routledge, pp. 127–44. [Google Scholar]

- Given, Lisa M., ed. 2008. The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Glick-Schiller, Nina, Linda Basch, and Cristina Blanc-Szanton, eds. 1992. Transnationalism: A new analytic framework for understanding migration. In Towards a Transnational Perspective on Migration. New York: The New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 645, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Griswold, Eliza. 2018. Mapping the Journeys of Syria’s artists. The New Yorker. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/mapping-the-journeys-of-syrias-artists (accessed on 28 January 2018).

- Groys, Boris. 2008. Art Power. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guillemin, Marilys, and Lynn Gillam. 2004. Ethics, reflexivity, and “ethically important moments” in research. Qualitative Inquiry 10: 261–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Akhil, and James Ferguson. 1997. Culture, power, place: Ethnography at the end of an era. In Culture, Power, Place. Explorations in Critical Anthropology. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Halasa, Malu. 2012. Creative Dissent. Index on Censorship 41: 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Clare E. 2006. The Buddha Goes Global: Some thoughts towards a transnational art history. Art History 29: 698–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Clare E. 2012a. The Museum on the Roof of the World: Art, Politics, and the Representation of Tibet. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Clare E. 2012b. In and out of Place: Tibetan Artists’ Travels in the Contemporary Art World. Visual Anthropology Review 28: 152–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydemann, Steven. 2013. Syria and the Future of Authoritarianism. Journal of Democracy 24: 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokayem, Emile. 2013. Syria’s Uprising and the Fracturing of the Levant. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, Seth M., and Heide Castañeda. 2016. Representing the “European refugee crisis” in Germany and beyond: Deservingness and difference, life and death. American Ethnologist 43: 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homsey, Dakota D. 2016. The Art of Exile: A Narrative for Social Justice in a Modern World. Student Publications. 421. Available online: http://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/421 (accessed on 15 November 2017).

- Jelinek, Alana. 2013. This Is Not Art: Activism and Other ‘Not-Art’. London: IB Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Karp, Ivan, and Steven D. Lavine. 1991. Exhibiting Cultures. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institute Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, Raminder, and Parul Dave-Mukherji. 2014. Arts and Aesthetics in a Globalising World. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kluijver, Robert. 2009. Syrian Artists Cherish Their Cultural Background. The Power of Culture. Available online: http://kvc.minbuza.nl/en/current/2009/august/syrian-artists (accessed on 26 December 2017).

- Krauss, Rosalind E. 1986. The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kräussl, Roman. 2014. Art as an Aternative Asset Class: Risk and Return Characteristics of the Middle Eastern & Northern African Art Markets. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langton, Marcia, and Nikos Papastergiadis. 2003. Complex Entanglements: Art, Globalisation, and Cultural Difference. London, Sydney, and Chicago: Rivers Oram Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lenssen, Anneka Erin. 2014. The Shape of the Support: Painting and Politics in Syria’s Twentieth Century. Ph.D. dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Little, Tom. 2011. Syrian Protesters Set Up Celebrity List of Shame. BBC Monitoring. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-16284426 (accessed on 2 February 2018).

- Longuenesse, Elisabeth, and Cyril Roussel. 2014. Retour sur Une Expérience Historique: La Crise Syrienne en Perspective. Beirut: Presses de l’Ifpo, Cahiers de l’Ifpo, p. 8. ISBN 978-2-35159-402-5. Available online: https://books.openedition.org/ifpo/6526 (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Mackinlay, John. 2003. Artists and war. The RUSI Journal 148: 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmvig, Helle. 2016. Eyes Wide Shut: Power and Creative Visual Counter-Conducts in the Battle for Syria, 2011–2014. Global Society 30: 258–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, George E. 1995. Ethnography in/of the world system: The emergence of multi-sited ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology 24: 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, George E., and Fred R. Myers, eds. 1995. The Traffic in Culture: Refiguring Art and Anthropology. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Naficy, Hamid. 1991. The poetics and practice of Iranian nostalgia in exile. Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 1: 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oweis, Khaled Yacoub. 2010. Feature—Damascus Art Gallery Ignites Syrian Culture War in Reuters. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/syria-art-idAFLDE6961JG20101013 (accessed on 30 January 2018).

- Pearlman, Wendy. 2017. We Crossed a Bridge and it Trembled: Voices from Syria. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Pink, Sarah, ed. 2009. Visual Interventions: Applied Visual Anthropology. New York: Berghahn Books, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Venetia. 2006. Word into Art: Artists of the Modern Middle East. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qayyum, Mehrunisa. 2011. Syrian Diaspora: Cultivating a New Public Space Consciousness. Policy Brief. No 35. Washington, DC: Middle East Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Roudi-Fahimi, Farzaneh, and Mary Mederios Kent. 2007. Challenges and opportunities: The population of the Middle East and North Africa. Population Bulletin 62: 24. [Google Scholar]

- Safran, William. 1991. Diasporas in modern societies: Myths of homeland and return. Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 1: 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, Ruba, and Sophie Richter-Devroe. 2014. Cultures of resistance in Palestine and beyond: On the politics of art, aesthetics, and affect. The Arab Studies Journal 22: 8–27. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Arnd. 1996. Uneasy relationships: Contemporary artists and anthropology. Journal of Material Culture 1: 183–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Arnd, ed. 2017. Alternative Art and Anthropology: Global Encounters. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Schultheis, Franz, Erwin Single, Raphaela Köfeler, and Thomas Mazzurana. 2016. Art Unlimited?: Dynamics and Paradoxes of a Globalizing Art World. Bielefeld: Transcript-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Seaman, Anna. 2016. Christie’s and Sotheby’s Make a Bid to Boost Middle East Art. The National. Available online: https://www.thenational.ae/arts-culture/christie-s-and-sotheby-s-make-a-bid-to-boost-middle-east-art-1.167781 (accessed on 5 March 2018).

- Shabout, Nada. 2012. In between, Fragmented and Disoriented Art Making in Iraq. Middle East Report 263: 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, Jonathan H. 2005. Metonyms of modernity in contemporary Syrian music and painting. Ethnos 70: 361–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sottimano, Aurora. 2016. Building authoritarian ‘legitimacy’: Domestic compliance and international standing of Bashar al-Asad’s Syria. Global Discourse 6: 450–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone Fish, Isaac. 2013. The Massive Mural That Captures Syria’s Surprising Alliance with North Korea. Foreign Policy. Available online: http://foreignpolicy.com/2013/09/10/the-massive-mural-that-captures-syrias-surprising-alliance-with-north-korea/ (accessed on 26 January 2018).

- Takieddine, Zena. 2011. Arab Art in a Changing World. Contemporary Practices 8: 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Charles. 1994. Multiculturalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Toukan, Hanan. 2013. Negotiating Representation, Re-making War: Transnationalism, Counter-hegemony and Contemporary Art ftom Post-Taif Beirut. In Narrating Conflict in the Middle East: Discourse, Image and Communications Practices in Lebanon and Palestine. Edited by Dina Matar and Zahera Harb. London: IB Tauris, vol. 121. [Google Scholar]

- UN News. 2018. Syria. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/focus/syria (accessed on 22 April 2018).

- Van Willigen, John. 2002. Applied Anthropology: An Introduction. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Vignal, Leïla. 2012. Syria: Anatomy of a Revolution. Paris: Books and Ideas. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, Mike. 2017. SNP Denies Trying to Shape Artists’ Ideas. The Sunday Times. Available online: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/snp-denies-trying-to-shape-artists-ideas-l6bctfqsc (accessed on 3 March 2018).

- Walker-Parker, Sharon LaVon. 2005. Embodied Exile: Contemporary Iranian Women Artists and the Politics of Place. Ph.D. thesis, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Weeden, Lisa. 2015. Ambiguities of Domination. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Welsch, Robert L. 2004. Epilogue: The authenticity of constructed art worlds. Visual Anthropology 17: 401–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, Andreas, and Nina Glick-Schiller. 2002. Methodological nationalism and the study of migration. European Journal of Sociology 43: 217–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]