Abstract

Driven by the solidarity movements following the “refugee crisis” of 2015, the Brussels-based non-profit organization Muziekpublique, specialized in the promotion of so-called “world music”, initiated the Refugees for Refugees project. This album and performance tour featured traditional musicians who had found asylum in Belgium and had artistic, political, and social goals. In comparison to the other projects conducted by the organization, each step of the project benefited from exceptional coverage and financial support. At the same time, the association and the musicians were facing administrative, musical, and ethical problems they had never encountered before. Three years after its creation, the band Refugees for Refugees is still touring the Belgian and international scenes and is going to release a new album, following the will of all actors to go on with the project and demonstrating the important social mobilization it aroused. Through this case study, we aim at questioning the complexity of elaborating a project staging a common identity of “refugees” while valuing their diversity; understanding the reasons for the exceptional success the project has encountered; and determining to what extent and at what level it helped—or not—the musicians to rebuild their lives in Belgium.

1. The “Migrant Crisis” in Brussels

By the end of summer 2015, the “migrant crisis”1 reached new dimensions in Europe and shook public opinion (Georgiou and Zaborowski 2017). Belgian political authorities did not adapt quickly enough to receive migrants who were arriving on their territory: hundreds of them,2 as they were waiting to fill in their asylum application at the Foreigners’ Office, were staying in the nearby Parc Maximilien in Brussels.3 In this tense context, numerous solidarity and humanitarian initiatives flourished.4

Several actors in the cultural sector, whose activities do not specifically concern refugees, decided to contribute in their own way. The radio station Musiq’3 set up the project “Musiques d’exil” [“musics of exile”];5 Syrians Got Talent was created to send a “strong political message of solidarity and for social inclusion.”6

In this article, we will discuss an initiative led by the Brussels non-profit organization Muziekpublique, which “defends and promotes musics of the world”7 by organizing concerts, coordinating a music school, and producing CDs.8 In October 2015, Muziekpublique launched the Refugees for Refugees project9 to record an album featuring refugee musicians, whose purpose was both artistic, political, and social. Each step was marked by exceptional media coverage and financial support compared to the other projects run by the organization.10 The CD was even awarded Best album of 2016 by the Transglobal World Music Charts. At the same time, the association and the musicians faced administrative and ethical problems they had never been encountering before. As a former Muziekpublique’s employee, Hélène Sechehaye coordinated the project from inside the organization from 2015 to summer 2016, and then continued to have regular contacts with the project. This article is largely based on her work during that period.

We aim at understanding the reasons for the exceptional success the project encountered in the cultural, associative, and media worlds. We will also discuss the ambiguity of this process that develops a common identity of “refugees” while simultaneously valuing their diversity. Finally, we will try to determine whether the project has modified or not the individual trajectories and the migratory careers (Martiniello and Rea 2014) of the musicians involved? To what extent and at what level did it help—or not—the musicians to rebuild their lives in Belgium?

2. Refugee Musicians, Bearers of Attacked Traditions

The analytical methods applied to musical practices in migratory context are of growing interest, having first emerged in the Anglo-Saxon world,11 and recently reached the French-speaking academic world.12 These studies often focus on the activity of minorities within urban societies, on diversity and multiculturality about western cities subject to globalization (Stokes 2004; Vertovec 2009; Aubert 2011; Bouët and Solomos 2011; Martiniello 2014; Devleeshouwer et al. 2015). In this context, Élina Djebbari’s study of a “transcultural” project identifies the two directions of application: one in which “hybridization is established as a norm”, the other advocating “the promotion of identities (where it is considered that the original musical style must remain identifiable, despite the mixing” (Djebbari 2012, p. 10). The concept of “diversity” is handled by the Belgian political world in the 21st century (OPC 2013, p. 4) to legitimize its public policies—even if what becomes a value is far from being shared by all segments of the population. Moreover, cross-cultural projects involving diversity are sometimes criticized for their “substantialization”13 of cultures (Zask 2014), as well as for their representation of a form of diversity that would be “acceptable”, and “aseptic” (Sainsaulieu et al. 2010, pp. 103–12).

“Integration” is often used along with diversity in policy and public debates. Whereas it indicates “social, political, cultural and economic processes that occur when migrants arrive in a new society” (Martiniello 2006, p. 4), it is often thought of as a linear process leading from the “migrant” status to the “integrated” foreigner, without considering potential stops or steps back. To nuance it, Martiniello and Rea (2014) propose the concept of “migratory careers”, that implies status changes as well as identity changes at each step of the career, breaks with the linear path concept and the migration/integration dichotomy. Martiniello proposes to replace integration with the term fair participation, that concerns “target individuals and groups in the social, economic, cultural and political spheres of the host European societies. In this perspective, a satisfactory level of immigrant integration is achieved when immigrants have similar participation patterns than non-immigrant citizens.” (Martiniello 2006, p. 9).

Can we approach refugees’ musical practices as usual migrants’ practices? There is a lack of literature on the music of refugees, who are specific migrants since the musical life of their country of origin is difficult if not destroyed, and as they have no possibility of returning to their country of origin.14 The definition of the object “refugee” is also problematic, because this status can be mobilized by people who do not possess this recognition but consider themselves as belonging to the “refugee” group, like Afghan individuals who were told by the Foreigners Office that the place they escaped is on the “safe areas list” and therefore cannot be granted the status legally (Tahri 2016).

Lambert (2018) notes that cultural heritage in the countries of origin is endangered by the destruction of archives, concert halls, the hunt for musicians and the exile of populations. Tahri (2016, p. 102) emphasizes the role that music, as poetry or dance, can play in “promoting the well-being of refugees”. Several studies have been carried out in migrant camps (Öğüt 2015; Tahri 2016; Emery 2017) and/or within specific communities (Diehl 2002; El-Ghadban 2005; Öğüt 2015). Most studies present these musical practices as part of the transit migration: musicians in refugee camps are not intended to settle there and are often on their way to other places. This influences their musical practices: “The feeling of being “unsettled” restricts the social and cultural relationships that can be formed with the local culture” (Öğüt 2015, p. 273). Though, Capone (2004, p. 11) notes that almost any deterritorialization process is followed by a re-territorialization process.

While it seems difficult to leave aside the problematic concept of “community” in ethnomusicology (Salzbrunn 2014), the “refugee” category encompasses heterogeneous populations in terms of nationality, religion, language … Therefore, we will here use the event lenses and study the different actors gathered by a particular event, rather than the ethnic lenses, which would focus on a particular social group defined with reference to ethnicity not relevant in the framework of this project.

3. Refugees for Refugees, from the Idea to the Stage

3.1. A Musical Metaphor

Muziekpublique launched the production of Refugees for Refugees, an album featuring refugee musicians living in Belgium. Its aim was and still is simultaneously artistic, political, symbolic, and social: to bring the voices of refugee musicians to the media through an album while helping them to integrate in European professional networks. Peter Van Rompaey, director of Muziekpublique, sets the context:

The purpose of our label is to support artists to develop their careers from A to Z. Here, the initial aim was to show that among refugees there are very good musicians, to show an image of refugee artists as a metaphor that they are also doctors, chemists … All refugees have talents, they are not items to reject.

The first exchanges around the project raised questions about the composition of the band: which “refugees” did the project want to feature? Muziekpublique eventually decided to follow its usual artistic line and to work with high-skilled musicians from classical and popular traditions, located in Belgium. As musicians were in a precarious situation, the decision was made to produce the album in a very short time:16 the speed made it also possible to guarantee media attention since the issue of refugees was a top media priority. The project was called Refugees for Refugees because part of its profits would be donated to social organizations promoting refugees’ expression, well-being and fair participation through amateur artistic practice.17

To find musicians, Muziekpublique contacted its usual artistic networks, but also organizations working in the associative field.18 Four artists simply refused to take part in the project, and three withdrew later for various reasons:19 the conditions of the recordings did not suit them;20 they could not find time to play music between administrative interviews, training, professional and family obligations. Some others expressed doubts about the project itself, first because its aims and results were very unclear when they were contacted, but also because many musicians were reluctant to be labelled as “refugees”.

In one month, a very heterogeneous group was brought together, made of some twenty musicians from different countries,21 sometimes speaking no common language,22 arrived by different means and having various legal statuses [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Refugees for Refugees during the CD release concert (Muziekpublique, Brussels, 13 May 2016). On stage: 17 musicians from 8 countries playing 15 different types of musical instruments and singing in 3 languages. Among them: 5 asylum seekers waiting for a decision, 8 having obtained the administrative “refugee” status, 3 Belgians, 1 stateless person. Credits: Jean-Luc Goffinet and Muziekpublique (used by permission).

As the recordings began, this heterogeneity also became a musical problem: how to combine various repertoires, musical systems, and languages? Muziekpublique looked for a musical mediator and director they already knew to coordinate the project. After a Syrian ‘ūd player they had proposed refused to play this role, they eventually asked the Belgian ‘ūd player Tristan Driessens, experienced in conducting transcultural ensembles.

Looking for financial support also happened to be faster than usual. Needing a start-up capital, the association used crowdfunding for the first time, which met and even exceeded its objective.23 An interest was also felt on the institutional side: the European Commission provided a support budget; the Wallonia-Brussels Federation, normally not entitled to support musicians not residing legally on its territory—which was the case of the majority of the group’s musicians—granted an exceptionally high budget for the recording of the album.

Simultaneously, the mainstream media, usually not much interested in world music, paid particular attention to the project.24 Several articles and major programs were devoted to Refugees for Refugees before the release of the album:25 this interest would never decrease.26 The project coordinator Lynn Dewitte, also regrets that it was not directed towards the musical project for itself but rather towards its political dimension and the musicians’ personal stories:

Journalists have preconceived ideas that they want to include in their articles. However, musicians do not necessarily want to get involved politically, sometimes they do not want to hear about politics anymore: their commitment is in music.

This exclusive commitment in music was confirmed by Tammam Ramadan, a musician in the project:

On stage, we break down [religious, linguistic] barriers, while there are wars at these borders. […] It costs nothing, it’s the cheapest solution. I hope we can replace wars with music, because it’s more effective.

However, tensions were palpable during the months preceding the CD release. Some musicians left the project because it did not meet their musical and professional expectations. The choices that the production team had to make concerning the layout of the album and its cover (Figure 2) raised questions of representation: the cover picture did not represent the whole band, and an imbalance was felt in the distribution of the tunes—some musicians would have liked to play on more tunes for instance.29 In the end, the musicians hardly identified themselves with the final product.

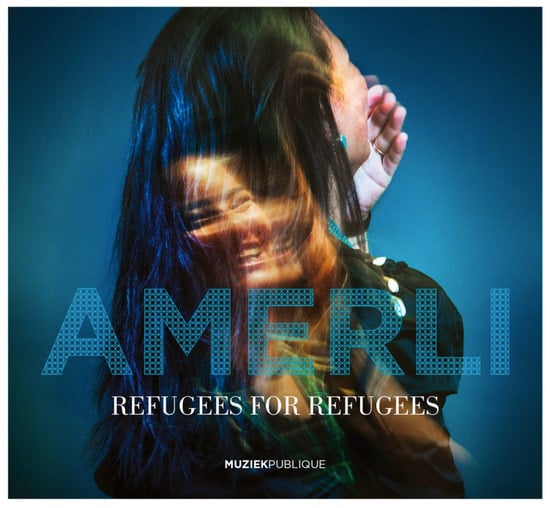

Figure 2.

The cover of the album shows the Tibetan singer Dolma Renqingi. Amerli, the title of the CD, refers to an Iraqi city. Credits: Dieter Telemans, Desiree de Winter & Muziekpublique (used by permission).

The album’s release concert in Brussels, on 13 May 2016 in the theatre Molière, the home of Muziekpublique, was crowded with world music aficionados, curious individuals, and several associations supporting migrants, who came with groups of their recipients.

3.2. From Song Compilation to Stage Performance

The band was quickly asked to give performances30, and musicians were enthusiastic to play some more concerts together. For technical and financial reasons, the band had to be reduced to ten musicians:31 the choices, made in a logic of scenic production, focused on the variety of profiles and repertoires, on the musicians’ ability to play together as well as on their desire to get involved in a long-term professional project in Belgium. While the band included musicians of various nationalities, several requests concerned a “band of Syrians” in relation to recent arrivals of refugees in the country.32

Muziekpublique also faced unusual demands. Many music festivals oriented towards “world music”33 wanted to feature Refugees for Refugees, whose musical repertoire is rather to be included in the category of “traditional music”34.

I usually don’t feel that our project is different from the others, because we play in the same places than the other Muziekpublique’s projects. But sometimes there have been festivals where, when I saw the other bands, I wondered if they had invited us just for the name of our band, because you feel that the music in these festivals is not the same as ours”,35 says Tammam Ramadan.

Other types of solicitations came from more official institutions. The presence of Refugees for Refugees was intensely desired but little valued in practice; for instance, the band was sometimes used as background music during a buffet.36 When the band was awarded the Culture Price by the Flemish Commission, it was proposed to take part in the ceremony and play some 15-s jingles before the announcement of each laureate, behind a curtain. After negotiations, the band also played two whole songs in front of the audience.

Many requests from the volunteer sector concerned events intended for their users, often refugees, to show them that some refugees have “successful” trajectories, willing to share with them positive stories as well as the opportunity to spend a festive moment with familiar music. The wage proposed to artists was often very low: while Refugees for Refugees tended to integrate musicians professionally, the fact that they needed to be paid decently to pursue their life project did not always seem to be a main concern for those who wanted to book them for a show.

In the end, the variety in the proposals was not necessarily perceived positively by Peter Van Rompaey:

We are of course happy that the project works. […] But we have the feeling that for this project, it is the theme that attracts. As it is in the news, the programmers jump on it without even listening to the songs, just because the musicians are refugees. We would like our other projects to generate the same interest.

3.3. Musicians on Tour: Work, an Obstacle to Fair Participation?

While all the musicians in the band eventually obtained a legal status in Belgium,38 many have since been affiliated to the CPAS39 and face enormous difficulties in getting paid. The musician’s work irregularity does not allow the CPAS to establish a protocol. Every month, problems concerning contracts, postpone the reception of money and cause many difficulties.

The CPAS system also sets a maximum earnings ceiling: above a given amount, the musicians’ wage is deducted from their monthly allowance.40 A feeling of uselessness to work may be felt, and even more, sometimes a musician who spends money for his transport or the babysitter cannot receive additional financial compensation, and must therefore indirectly “pay” to work.41

Things are not easier for the few musicians who decide to enter the labor market by accepting non-artistic work: fixed working hours make it difficult to spend several days abroad.

“The difficulty of their situation is one of the things that does not change. Even with so many concerts […] One of the musicians had managed to leave the CPAS and was trying to make a living from classes and concerts, but after two years he gave up, it was too hard,” says Lynn Dewitte.

However, some have been able to highlight their involvement in music as a positive point to advocate their case with the administration, as Tammam Ramadan explains:

When the CPAS employees asked me to find a job, they thought music was my hobby, and proposed me to work as a vegetable cutter in a restaurant. Showing them my contracts helped me to defend my artistic project.

Two particular barriers to a professional career were mentioned.44 On the one hand, travelling outside the Schengen area is difficult for people with the status of refugee45. Although this situation has not yet occurred, it is a potential problem.46 On the other hand, the family situation, and the events in their country of origin disrupts the musicians a lot, even if they do not talk about it at work. In these conditions they find it difficult to devote themselves totally to their artistic production. Yet, the ‘ūd player Tristan Driessens, notes that music can sometimes ease injuries:

Sometimes, there are musicians who carry on their shoulders very heavy bereavements […] Being able to express oneself in Europe through one’s instrument, one’s art, makes it much lighter. It always creates an atmosphere of joy despite the realities that are still there […] I witness how music can really heal pain and suffering.47

4. Three Years Later: Same Name, New Shape

In two years, the band Refugees for refugees gave about sixty concerts and the album sold more than 2500 copies.48 While some tensions are still present, the musicians became used to each other’s musical languages and are now driven by the desire to progress together. The idea of a new album, presenting the “work of the band,” has gained ground. An important turning point in the band’s life was an artistic residency in the fall of 2017, during which new compositions were thought for the whole group, musical textures were worked on. The band really became a band, and was no longer the addition of individuals. A balance was found between the different repertoires, but the main focus is still on the bridges created between them. “The moments of exchange between the repertoires are what people [from the audience] appreciate most,” says Lynn Dewitte.49 The description of the project now highlights the message of hope and resilience conveyed by the project, as well as the album turns a new page, symbolizing reconstruction.50

The relevance of the designation Refugees for Refugees is questioned: as seen above, the denomination of musicians as “refugees” is sometimes experienced in a negative and stigmatizing way. Hussein Rassim, ‘ūd player who was involved in the early stages of the project, says in this regard:

Once the sadness of no longer playing with the band passed, I realized that it opened up other opportunities for me. During a festival in Tournai, I played on the same stage than Refugees for Refugees. But while their names were appearing in small, under the project title, mine was appearing in large. I realized that my career could also take advantage from it.

This name will finally be maintained so that professionals recognize the continuity of the project. Tammam Ramadan says: “After four years in Belgium, you have to understand that you are a refugee, whether you agree or not.”52

The new CD release, no longer considered as a separate project but as an ordinary production of Muziekpublique, is scheduled for February 2019. Artistically, all the participants are convinced that it will be musically better than the previous one, but doubts are expressed about the same warm welcome as for the first opus, because “[the subject of refugees] is not so fashionable anymore.”53

5. Refugees’ Narratives, Skills, and the Music

The Refugees for Refugees project stands out from the other projects supported by Muziepublique. First thought of as a one-shot project, it received particular attention in terms of funding, by the media as well as the audience. Gradually, it has changed and has developed in the long run, responding to a demand from some musicians, Muziekpublique and other organizations. Aiming at promoting and networking high-skilled musicians who arrived in Belgium, Refugees for Refugees differs from other projects born during the “welcome crisis” by its longevity and by the repertoire played by the musicians—a repertoire that comes from “back home” (Emery 2017, p. 57). In the discussion, we will examine to what extent it affects cultural, social, economic, and political aspects of the refugees’ presence in Belgium.

5.1. To Be a “Refugee” Musician, between Confinement and Perspectives

In the beginning of the project, the musicians we asked to fit in a top-down approach that values their differences, turned towards the substantialization of their musical practices (Zask 2014). Each one played a repertoire from his or her home country. This approach of diversity through world music was described by ethnomusicologist Laurent Abert as such:

In a multicultural environment such as that of the major Western metropolises, one can notice that world musics represent both unifying standards of identity and bridges between communities; they are one of the few areas in which the integration of each individual does not imply assimilation to dominant models.(Aubert 2011, p. 28 [our translation])

One could first wonder what would be the musical dominant model in Belgium, what kind of musical models would musicians be expected to assimilate? Their own musical traditions and heritage are either exoticized or neglected. It certainly is difficult for them to navigate between these two scenarios or to find another way to participate and be recognized by the Belgian music world and by the larger society.

However, it seems that the visibility is made easier by adhering to the simplistic categories in which musicians are classified without further reflection (Cabot 2016, p. 20). While one of the project’s aims was to show the diversity present within this “refugee” band, the framework seemed to imply a way of featuring it that leaves little space for negotiation.

This approach is then perceived as locking up: Hussein Rassim, who founded his own band, reports that the organizers who contact him are surprised that there are also Belgian musicians in his band, while they would have preferred only “refugees.”54 Similarly, some criticism has been leveled at Muziekpublique regarding the presence of two Belgian musicians in a band of so-called “refugees”. The arrival of immigrant and refugee populations, which has led to policies and discourses on “living together” that aimed at building bridges, has paradoxically led these same actors to build barriers by identifying and institutionalizing distinct categories of people (OPC 2013, p. 14).

The epistemological violence carried by the term “refugee” also raises the issue of refugees considered as voiceless, deprived of their agency, who could only speak when given the word (Cabot 2016). It is interesting to note that, as long as it fit the musical quality required, Muziekpublique did not interfere in the repertoire played by the musicians. Roles were distributed clearly: Muziekpublique was responsible for the production work, and the musicians for the repertoire. It resulted in the fact that some musicians sometimes did not agree on the ways the project was introduced; or that Muziekpublique discovered that a new song with what they considered as unbearable kitsch arrangements had appeared during a concert. But overall, this way of working allowed the project to emerge and progress despite the different perspectives of about thirty participants.

Although the project was part of the news, fighting with mainstream discourses against refugees hosting, it did not aim at being sensationalist. The musicians’ journey and suffering were not recounted unless asked by journalists. In the music of the album, all musicians were not willing to speak about their suffering and escape. Spiritual Sufi songs follow traditional songs praising Epicureanism; poems remembering Himalayan mountains; or an instrumental evoking the epic of a city besieged by the Islamic state55. If the refugee narratives implicitly appear along the album, the musicians did not make it its common theme: songs with sometimes opposing speeches rub shoulders, echoing the musicians’ various profiles.

Gradually, from a project featuring “art by migrants”, the project has transformed itself into a “transcultural creation” (Djebbari 2012), “mobilizing its cultural differences as its conscious object” (Appadurai [1996] 2001, p. 206) to raise awareness both to the various traditions brought by refugees, and to the bridges that can be built between them. The ensemble transformed itself into a band with which the musicians can identify, with a unified discourse around their musical practice. Despite the band’s name, their art is not about migration or about migrants anymore: their approach is touched by “migratory aesthetics” (Bennett 2011) mainly because the experience of migration allowed their encounter, their discovery of other musical languages, their project together.

The CD encountered an obvious success: it was awarded “World Music album of the year” by the Transglobal World Music Charts in 2016;56 it received the Culture Prize from the Flemish Community in 2017; international media praised it (Al Jazeera; Froots; Songlines; BBC; Le Monde; Libération …). Programmed all over Europe, the band got a warm welcome in every place where it performed. Despite the fact that the musicians cannot physically travel to their home countries, digital distribution of the album and social networks reached an audience worldwide. Proudly57 sharing the project news on their Facebook page, the musicians received hundreds of expressions of support from their compatriots. This transnational dimension of the Refugees for Refugees project is not the focus of this article, but it seems clear that people seeing their own musical cultures endangered in their countries tend to support initiatives maintaining these musical cultures elsewhere.

Cabot (2016) shows how refugee voices are often silenced even—or particularly—when they are “given a space of speech”—this last expression already denying them any autonomous speaking. We saw that though communication was clearly oriented, the content of the album was totally left to the artists, resulting in songs about love, religion, politics, nature ... After all the events described earlier—organizers asking for the project without having heard a song; music used as a background for banquets—one could ask who really listened to the music? These pieces are not of exile, but the words that musicians themselves wanted to say.

Some interesting self-reliance demonstrations happened unexpectedly—or not—outside the project. During the first year after the CD release, Tibetan singer Dolma Renqingi developed some musical projects featuring rock and pop repertoires. Without claiming that there is a direct link with Refugees for Refugees, we can assume that taking part to this project gave her confidence and tools to mobilize networks she had newly acquired in Belgium. Another musician of the band ran for the municipal election for the first time in 2018: again, without knowing if there is any causal link to this,58 we could suppose that playing with musicians from other backgrounds, having to cope with new language and administrative challenges, and juggle networks is something that could have been reinforced through his involvement in Refugees for Refugees.

Muziekpublique’s inability to meet some of the musicians’ demands lead to some big conflicts and sometimes leavings. These departures were firstly felt as failures, but have actually led some musicians to express their agency by creating their own artistic project.

5.2. A Project Based on Skills

Among the remaining musicians, several of them joined the European professional networks through this project—which would probably have happened anyway for most of them, but at a slower pace. In the end, leaving the CPAS system remains difficult for several of them; being paid for playing their music also remains difficult, despite the fact that they have been working on this project for almost three years. With few exceptions, the administrative situation of artists has not dramatically changed; and the band still faces difficulties in travelling outside the Schengen area.

Muziekpublique targeted the self-reliance of musicians, wishing to go beyond the representations of “refugees” as victims and vulnerable (Refugees Studies Centre 2017) by presenting them as skilled people. Their wish for autonomy seems to have partially failed, at least in economic terms, as Peter Van Rompaey expresses:

Their situation is still complicated, even if they have a good time [during the concerts]. It’s very difficult to move on to another level, and it’s perhaps the biggest disappointment … But it’s the same […], it’s not just about being a refugee musician. It’s hard to play music from your own country and to be accepted by the mainstream media. Somewhere along the line, it’s the biggest disappointment, not only about this project. The organizers are interested in the history of the musicians, but in reality, few are interested in what they do.

The lack of flexibility of the institutions, the administrative uncertainty and lack of knowledge of the necessary tools seem to be structural reasons preventing the empowerment of musicians or in other words to take full control of their migratory and musical careers.

“In addition to providing livelihoods, projects for refugees, humanitarian and political actors should address the systemic issues, such as barriers to work or a lack of legal representation, that create challenging work and living conditions for refugees”.(Refugees Studies Centre 2017, p. 2)

This brings us to the refugees’ narratives: whereas one cannot criticize the advantages of going beyond the representation of refugees as victims, representing them as super-refugees (high-skilled individuals or heroes) can also influence badly our perception of refugees who do not meet these expectations (Fiddian-Qasmiyeh 2017). This question was central to Muziekpublique’s concern, whose explicit main goal is artistic—proposing quality to a demanding audience, whereas working with refugees or other musicians.60 What would happen to the “non-chosen” ones? Muziekpublique answered this question in two ways. On the one hand, some of the projects founded by refugee musicians who were not enrolled in Refugees for Refugees have been set into Muziekpublique’s regular programing.61 On the other hand, by helping financially organizations whose work with refugees is based on an amateur artistic practice, Muziekpublique indicates and supports the many ways in which music can take part in helping refugees. This situation induces a small reversal in which seems one-way. The musicians are not only hosted in Belgium: by contributing with the donation of a part of the CD profits to other associations, they have closed the loop and become hosts of other refugees.

Several ethical issues are also raised by this project. The selection procedure for musicians, conducted by the association, favored word of mouth and networks, and did not reach all the refugee musicians living in Belgium. The participants were lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time. Second, Muziekpublique’s efforts to find musicians only allowed them to meet three female musicians, among which only one stayed in the band, the singer Dolma Renqingi.62 The representation of women is a recurrent question in the world music worlds as in other artistic worlds (Zheng 2009, p. 41; Olivier 2012, p. 58; Pouchelon 2014, p. 207). Not being very present on stage, they are conventionally confined to the roles of singer or manager. Studies focusing on refugee populations note that women are usually invisible and therefore even more vulnerable than men (Emery 2017, p. 65; Refugees Studies Centre 2017, p. 3). Third, the project coordinators are all Belgians, as is the musical director. With one exception,63 the refugee musicians hold various non Belgian nationalities. A racialized division of labor (Stokes 2004) can be observed within the project. One our reviewers rightly pointed out that this article used to include more quotes from Muziekpublique’s workers than from musicians64. Aware of this problem, Muziekpublique tried to make things change from within, and for example hired one of the band’s musician to work a part-time administratively for the project.

Have the musicians really benefited from the project? In light of these elements, one might be tempted to assume that in spite of good intentions, Refugees for Refugees could be an involuntary reinforcement of a situation this project claimed to fight against (Stokes 2004, p. 372). The association advocates “self reliance” but at the same times intervenes in many ways by deciding decide how to communicate around the project, hiring translators during major conflicts or by the presence of a (non-refugee) musical mediator. At the same time, refugee musicians use their agency to build the repertoire, to change the performance conditions when they do not agree with it, and sometimes leave the project for new horizons.

Using the term “refugees” in the band’s name clearly conditioned its reception by the media and organizations. This status, which was perceived as a stigma by musicians but as the banner of a struggle by Muziekpublique and the media (Devleeshouwer et al. 2015, p. 113), changed with the formation of musicians as a real ensemble. Some musicians were asked if they would have conducted the project differently, particularly with regard to the choice of the name: some replied that they would have found another name, some said that they do not know, and others that they would probably have chosen the same name, for communication reasons. We hope that this section, considering all the nuances and the heterogeneous nature of the individuals gathered by the project, proved the difficulty to simply oppose Muziekpublique and the “refugee” musicians.

6. Conclusion: Can We Talk about Results? A Project Raising Multiple Issues

The initial goals of the project Refugees for Refugees were to produce a high quality album; to help refugee musicians to integrate in professional European music networks; and to promote the cultures carried by “refugees” and to change the way they were socially viewed. As these objectives are multiple, so are the results: some of them seem to be fully accomplished, others to have partially—or totally—failed. Our definition of “success” and “failure” must take into account not only an economic point of view, as we should be tempted to do, but also consider the other dimensions such as social and cultural. Another thing to point out is that despite the institutional weight, the ordinary relationships between people, the situations of diversity people face every day go much faster than politics (Vertovec 2009, p. 28).

Given the reviews from the specialized media and the numerous concert proposals, but also the abundant expressions of support from compatriots residing in home countries, the musical quality objective was reached. The evaluation of the second objective is more difficult: if musicians have indeed played on several major European scenes, their participation into the labor market is more or less effective on a case-by-case basis. Few musicians said this project helped them to enter the Belgian market; more face real difficulties to get out of what could be called the vicious circle of social aid. Finally, it is difficult to assess the project’s role in looking at the “refugees” issue in Belgium:65 we do not know how many people have been affected by the project, nor whether they were already convinced by the cause before the project started or whether it really helped to improve the visibility of the refugees’ struggle for their rights.

The analysis through migratory careers points out the interest of considering the resettlement of migrants not only through the economic dimension, but also through their social, cultural, and other needs (Tahri 2016; Refugees Studies Centre 2017; Martiniello 2014). The examination of several levels that were influenced by the project helps to reflect the complexity of the situation, evolving at different speeds. The use of music allowed a certain kind of participation into the host society: musicians found their place in a group and the pleasure of playing music; they have had access to a professional activity; and some of them see it as an ideological involvement (“crossing borders on stage”). Music makes it possible to build links “beyond identity” (Bennett 2011, p. 473). It might seem strange that in this article about a musical project, co-written by a musicologist, music is so little mentioned; however, that is finally what this project was all about: moving people with an aesthetic shock.

Nevertheless, the host society in which we would like musicians to participate fairly (or “integrate”) has structural problems at the root: racism and sexism; overestimation of the activity of “work” even though the professional sector is difficult to access; and considering that work is a major path to participation while there are many others. Moreover, the “othering” of refugees can be identified as an encouragement to substantialize them as “extra-territorials” and thus justify their different treatment by medias, policies, and institutions (Glick Schiller 2010, p. 109). Paradoxically, while work is overestimated in speeches, there is a great disorder in the modes of professional integration for world music artists, whether they are refugees or not (Laborde 2012, p. 11). If musicians and their projects are symbolically valued by society, there is a need for another form of institutional support that would allow artists to take into account the specificity of their situation—especially when they come to take refuge in a country about which they do not know anything. The bridge between the migratory career and the musical career still needs to be built.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, H.S.; Writing—review & editing, M.M.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Heartfelt thanks to the anonymous reviewers and Anne Damon-Guillot for their sharp and precious comments; to Marco Martiniello who took over the supervision as soon as it was needed; to Nastasia Dahuron for her review of the translation; to Stéphanie Weisser whose participation was missed; and to the Muziekpublique team and musicians who work hard to make music happen.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Appadurai, Arjun. 2001. Après le colonialisme. Les conséquences culturelles de la globalisation [Modernity At Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization]. Paris: Payot & Rivages. First published 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Aubert, Laurent, ed. 2005. Musiques migrantes, de l’exil à la consécration. Genève: Musée d’ethnographie. [Google Scholar]

- Aubert, Laurent. 2011. La musique de l’autre. Les nouveaux défis de l’ethnomusicologie. Genève: Georg. [Google Scholar]

- Bachir-Loopuyt, Talia. 2008. Le tour du monde en musique. Les musiques du monde, de la scène des festivals à l’arène politique. Cahiers d’ethnomusicologie 21: 11–34. [Google Scholar]

- Baily, John, and Michael Collyer. 2006. Introduction and Special Issue, Music and Migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 32: 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Jill. 2011. Migratory Aesthetics: Art and politics beyond identity. Directed by Mieke Bal and Miguel A. Navarro Hernandez. In Art and Visibility in Migratory Culture: Conflict, Resistance, and Agency. Amsterdam: Rodopi, pp. 450–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bouët, Jacques, and Makis Solomos, eds. 2011. Musique et Globalisation: Musicologie–Ethnomusicologie. Paris: L’Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- Cabot, Heath. 2016. “Refugee Voices”: Tragedy, Ghosts, and the Anthropology of Not Knowing. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 45: 645–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, Laura. 2018. Faut-il dire migrant ou réfugié? Débat lexico-sémantique autour d’un problème public. Langages 210: 124–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, Stefania. 2004. À propos des notions de globalisation et de transnationalisation. Civilisations (Bruxelles, Université Libre de Bruxelles) LI: 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damon-Guillot, Anne, and Mélaine Lefront. 2017. Comment Sonne la ville? Musiques Migrantes de Saint-Etienne. Villeurbanne: CMTRA/Université Jean Monnet. [Google Scholar]

- Devleeshouwer, Perrine, Muriel Sacco, and Corinne Torrekens, eds. 2015. Bruxelles, Ville-Mosaïque. Entre espaces, Diversité et Politiques. Bruxelles: Editions de l’Université Libre de Bruxelles. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl, Keila. 2002. Echoes from Dharamsala: Music in the Life of a Tibetan Refugee Community. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Djebbari, Elina. 2012. Du trio de zarb aux “créations transculturelles”. La création musicale du percussionniste Keyvan Chemirani: Une globalisation parallèle? Cahiers d’Ethnomusicologie 25: 111–37. [Google Scholar]

- El-Ghadban, Yara. 2005. La musique d’une nation sans pays: Le cas de la Palestine. In Musiques—Une encyclopédie pour le XXIème siècle. Directed by Jean-Jacques Nattiez. Tome 3. Arles/Paris: Actes Sud/Cité de la Musique, pp. 823–52. [Google Scholar]

- Emery, ed. 2017. Radical Ethnomusicology: Towards a politics of “No Borders” and “insurgent musical citizenship”—Calais, Dunkerque and Kurdistan. Ethnomusicology Ireland 5: 48–74. [Google Scholar]

- Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, Elena. 2017. Disrupting Humanitarian Narratives? Representations of Displacement Series. Available online: https://refugeehosts.org/representations-of-displacement-series/ (accessed on 29 December 2018).

- Georgiou, Myria, and Rafal Zaborowski. 2017. Couverture médiatique de la « crise des réfugiés»: perspective européenne. In Rapport du Conseil de l’Europe. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/couverture-mediatique-cirse-refugies-2017-web/168071222e (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Glick Schiller, Nina. 2010. A global perspective on transnational migration: Theorising migration without methodological nationalism. In Diaspora and Transnationalism. Concepts, Theories and Methods. Directed by Rainer Bauböck, and Thomas Faist. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 109–129. [Google Scholar]

- Laborde, Denis. 2012. Faire profession de la tradition? Equivoques en Pays Basque. Cahiers d’ethnomusicologie 25: 205–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, Jean. 2018. Les musiques du Moyen-Orient: patrimoines en danger? In Al Musiqa. Paris: Éditions La Découverte/Cité de la musique, pp. 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, Erik, and Florian Scheding, eds. 2010. Music and Displacement: Diasporas, Mobilities, and Dislocations in Europe and Beyond. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martiniello, Marco. 2006. Towards a coherent approach to immigrant integration policy(ies) in the European Union. Intensive Programme “Theories of International Migration”; Liège: Liège University, August 29. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/dev/38295165.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Martiniello, Marco, ed. 2014. Multiculturalism and the Arts in European Cities. New York: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Martiniello, Marco, and Andrea Rea. 2014. The concept of migratory careers: Elements for a new theoretical perspective of contemporary human mobility. Current Sociology 62: 1079–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiniello, Marco, Nicolas Puig, and Gilles Suzanne, eds. 2009. Créations en migration, Parcours, déplacements, racinements. Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales 25: 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Öğüt, Evrim Hikmet. 2015. Transit migration: An unnoticed area in ethnomusicology. Urban People-Lidé mésta 2: 269–82. [Google Scholar]

- Olivier, Emmanuelle, ed. 2012. Musiques au monde. La tradition au prisme de la création. Sampzon: Deltour-France. [Google Scholar]

- Observatoire des Politiques Culturelles. 2013. La Diversité Culturelle. Repères. Politiques Culturelles 3. Available online: http://www.opc.cfwb.be/index.php?id=9943 (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Pistrick, Eckehard. 2015. Performing Nostalgia. Migration, Culture and Creativity in South Albania. Ashgate: Farnham. [Google Scholar]

- Pouchelon, Jean. 2014. Les Gnawa du Maroc: Intercesseurs de la Différence? Étude Ethnomusicologique, Ethnopoétique et Ethnochoréologique. Ph.D. dissertation, 2014, Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC, Canada, Université Paris Ouest, Nanterre, France. [Google Scholar]

- Refugees Studies Centre. 2017. Refugees Self-Reliance. Moving Beyond the Marketplace. In RSC Research in Brief 7. Oxford: Oxford University. [Google Scholar]

- Sainsaulieu, Ivan, Monika Salzbrunn, and Laurent Amiotte-Suchet, eds. 2010. Faire communauté en société. Dynamique des appartenances collectives. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes. [Google Scholar]

- Salzbrunn, Monika. 2014. Traverser des paysages sonores translocaux: Réflexions méthodologiques sur la transnationalisation du religieux à travers la musique et les événements. Paper presented at International Conference on the Transnationalization of Religion Through Music, Montréal, BC, Canada, October 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, Martin, ed. 1994. Ethnicity, Identity and Music. The Musical Construction of Place. Oxford: Providence, Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, Martin. 2004. Musique, identité et “ville-monde”. Perspectives critiques. L’Homme 171–72: 371–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tahri, Anissa. 2016. “Je suis réfugié”. Entre Affirmation Identitaire et Reconnaissance, le Parcours d’asile des Afghans en Belgique. Master’s dissertation, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Bruxelles, Belgium. [Google Scholar]

- Vertovec, Steven. 2009. Conceiving and Researching Diversity. Working Paper 09-01 given at Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity. Göttingen: Max-Planck Institute, pp. 8–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zask, Joëlle. 2014. Contre “l’identité culturelle” et “l’appartenance”, la question de la culturation individuelle. Available online: http://joelle.zask.over-blog.com/2017/04/contre-l-identite-culturelle-et-l-appartenance-la-question-de-la-culturation-individuelle.2014.html (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Zheng, Su. 2009. Claiming Diaspora: Music, Transnationalism, and Cultural Politics in Asian/Chinese America. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Also referred to as “migrants’ crisis” by the media, or “welcome crisis” in the more engaged media (for an analysis of the lexical treatment of the event, read Calabrese 2018). |

| 2 | The estimated figure varies between 600 individuals (Wahoud Fayoumi, “Réfugiés à Bruxelles: “Jamais je n’aurais imaginé un camp en Belgique” [Refugees in Brussels: “I’d never have imagined a camp in Belgium”], rtbf.be [online], 9 September 2015) and 1200 (Thomas Mangin, “Parc Maximilien, le village pour réfugiés s’organise tant bien que mal” [Parc Maximilien, the village for refugees is getting organized as best it can], Le Soir [online], 16 September 2015). |

| 3 | This problematic situation has not ended with the so-called “welcome crisis”: in 2018, hundreds of migrants are still gathering around the Parc Maximilien where they sleep at night, or are taken care of by associations. |

| 4 | September 2015 saw the birth of the non-profit organization Plateforme Citoyenne de Soutien aux Réfugiés Bruxelles [Brussels Citizen Platform for Refugee Support], which coordinates all the initiatives and is still active three years later [http://www.bxlrefugees.be/en/ seen 8 August 18]. |

| 5 | Achille Thomas, “Musiques d’exil: le Festival Musiq’3 lance un projet de soutien aux réfugiés” [Musics of exile: Musiq’3 Festival launches a project to support refugees], Musiq’3, 2 February 2016 [https://www.rtbf.be/musiq3/emissions/detail_festival-musiq3/accueil/article_musiques-d-exil-le-festival-musiq-3-lance-un-projet-de-soutien-aux-refugies?id=9203019&programId=3773 seen 24 August 2018]. |

| 6 | Description of the project on their Facebook page Syrians Got Talent [https://www.facebook.com/pg/ SyriansGotTalent/about/ seen 24 August 2018]. |

| 7 | About this controversial designation, read (Aubert 2005, 2011; Bachir-Loopuyt 2008; Bouët and Solomos 2011; Olivier 2012). |

| 8 | Organization’s description on their website [https://muziekpublique.be/about/?lang=en, seen 24 August 2018]. |

| 9 | Band’s website [http://muziekpublique.be/artists/refugees-for-refugees/ seen 18 September 2018]. |

| 10 | Interview with Peter Van Rompaey and Lynn Dewitte, Brussels, 28 February 2018 [our translation]. |

| 11 | To name a few: (Stokes 1994; Baily and Collyer 2006; Zheng 2009; Levi and Scheding 2010; Bouët and Solomos 2011; Pistrick 2015; Martiniello et al. 2009; …). |

| 12 | Several research projects are being carried out in Nanterre and Saint-Étienne (Damon-Guillot and Lefront 2017); the 2018–2019 nomadic seminar of the French Society of Ethnomusicology is entitled “Music and immigration in France”; the next issue of the Cahiers d'Ethnomusicologie will be devoted to “Migrants’ Music”. We can also mention Martiniello et al. (2009). |

| 13 | Substantialization of culture, sometimes called “essentialization” (Capone 2004; Djebbari 2012) is defined by Zask as follows: “a particular culture as a kind of unified whole that customs have fixed on the one hand, history and circumstances on the other. Ethnicity then appears as an index of fixity”, a stable entity hermetic to change that would stick to the skin. |

| 14 | The “refugee” status may be withdrawn from an individual who has been granted it if he or she travels to his or her country of origin. Source: General Commission for Refugees and Stateless Persons, leaflet “Vous êtes reconnu réfugié en Belgique. Vos droits et vos obligations” [You are recognized as a refugee in Belgium. Your rights and obligations], November 2016, p. 10. Available online: https://www.cgra.be/sites/default/files/brochures/2016-11-25_brochure_reconnu-en-belgique_fr_0.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2016). |

| 15 | Interview with Peter Van Rompaey, Brussels, 30 August 2018 [our translation]. |

| 16 | Seven months separated the first discussion on the project from the CD release: the search for musicians began in October 2015, funding requests were sent in November, recordings took place in December 2015 and February 2016, and the CD was released in May 2016. |

| 17 | Two Brussels non-profit organisations, Globe Aroma and Synergie 14, are given 1€ each per CD sold. |

| 18 | Humanitarian organizations, welcome centers, language schools for newcomers, and citizen initiatives. |

| 19 | Unfortunately, due to the poor conditions in which the collaboration stopped with these musicians, they did not wish to answer the questions asked in the context of this article, probably no longer wishing to be associated with it. |

| 20 | Muziekpublique, not having large resources, proceeds for this project as it does for others: the recordings take place in “live” conditions and not in a studio; some musicians, thinking they will be included in a full classical orchestra, realize that they can only work with the musicians on board; the association cannot provide accommodation for musicians coming from far away during the recordings period. |

| 21 | Syria, Iraq, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tibet. Despite the non-recognition of their country on the official level, the musicians participating in the project consider themselves as “Tibetans”. Muziekpublique then chose to indicate this geographical area at the same level as the other nations in the description of the project, a militant choice that sometimes prevented the project from being programmed for important institutional events. |

| 22 | While lack of language skills is generally not an obstacle, Muziekpublique used translators on several occasions: during initial contacts with musicians; or during major conflicts involving members of the band. |

| 23 | €15.755, 126% of the initial goal, were collected in one month thanks to 272 supporters. |

| 24 | The week of the recordings in December 2015 was a real media marathon. |

| 25 | “Des réfugiés unis par la musique” [Refugees united by music], La Libre Belgique, 14 December 2015; “The Musician from Diyala”, Al Jazeera (UK), 24 December 2015; “Tout le Baz’Art” [The whole baz’Art], Arte/La Trois, 1 March 2016; “Les Festivals de musique ouvrent leurs scènes aux artistes réfugiés” [Music festivals open their stage to refugee artists], Télérama, 22 June 2016; “De la musique en mémoire d’Alep” [Music in the memory of Aleppo], Le Soir, 21 April 2016; “Virtuoze vluchtelingen” [Virtuoso refugees], De Standaard, 13 May 2016; “L’Invitation” [The invitation], RTBF—La Trois, 16 May 2016. |

| 26 | Recently “Des réfugiés jouent pour les réfugiés, au gré des marées” [Refugees play for refugees, at the discretion of the tides], Le Monde, 16 August 2018; “Quand on est sur scène, je ne sens pas que nous sommes réfugiés” [When we are on stage I don’t feel we are refugees], Libération, 21 August 2018. |

| 27 | Interview with Lynn Dewitte, Brussels, 30 August 2018 [our translation]. |

| 28 | Interview with Tammam Ramadan, Brussels, 30 August 2018 [our translation]. |

| 29 | Which was not feasible: for various reasons, at no time could all the musicians get together. Similarly, the photo sessions were not attended by all artists. |

| 30 | Even before the CD was released, the band was invited by the Music Meeting (Nijmegen, NL), Festival de Wallonie (Villers-la-Ville, BE), Espéranzah! (Floreffe, BE), Festival Les Suds (Arles, FR), Festival d’Art de Huy (BE) and Les Rencontres Inattendues (Tournai, BE). |

| 31 | At its beginning, the band was gathering Ali Shaker Hassan (qānūn), Aman Yusufi (dambura and vocals), Asad Qizilbash (sarod and violin), Dolma Renqingi (vocals and choreography), Kelsang Hula (dramyen and vocals), Khaled al-Hafez (vocals and daf), Simon Leleux (darbūka), Tammam Ramadan (nāy), Tareq al-Sayed Yahya (‘ūd) and Tristan Driessens (‘ūd). Today, Souhad Najem (qānūn) has replaced Ali Shaker and Fakher Madallal (vocals) has replaced Khaled. |

| 32 | Since 2015, the main nationalities of asylum seekers have changed: while Syrians still arrive in large numbers in Belgium, new migrant groups are now mainly made of Eritreans and Sudanese people. |

| 33 | In French as well as in English, the “world music” label generates much confusion. Laurent Aubert (2011, p. 32) established three categories encompassed by this term: folklore music, world music and traditional music. According to him, the label “world music” refers to fusion repertoires: “experiences generated by the meeting of musicians from diverse backgrounds and by the integration of “exotic” instruments and sounds into the electronic equipment of current Western music production” (Aubert 2011, p. 33, our translation). |

| 34 | Music with an acoustic aesthetic, oriented towards the act of listening and often perceived by Western audiences as “authentic”, unlike world music, which fully assumes an aesthetic of hybridity (Aubert 2011, p. 33). |

| 35 | Interview with Tammam Ramadan, Brussels, 30 August 2018 [our translation]. |

| 36 | This made the Aleppo musicians particularly angry: they refused to play their Sufi repertoire in front of an audience drinking alcohol that was not even listening to them. |

| 37 | Interview with Peter Van Rompaey, Brussels, 30 August 2018 [our translation]. |

| 38 | When they arrive in Belgium, asylum seekers must submit a file to the CGRS (Office of the commissioner general for refugees and stateless persons). In the time period preceding the granting or not of refugee status, asylum seekers are in a precarious legal status, legally not allowed to work in Belgium. |

| 39 | CPAS (Centre public d’action sociale [Public social action center]): in Belgium, a public institution that supplies a number of social services including a monthly allowance for those who do not have a job or access to unemployment benefit. |

| 40 | These ceilings vary according to the allowance received and the CPAS to which they are affiliated. |

| 41 | The application of these laws differs from one CPAS to another, and even within the same CPAS, a general lack of clarity surrounds the recipients’ rights. As on this FAQ from Brussels City CPAS website: “Do I still have the right to earn money if I receive the living wage? It depends on the case: it is imperative to inform your assistant of any amount of money received”. The assistant in question is available on a permanent basis one hour a week, during which the phone line is saturated with calls. Source: “Some frequently asked questions”. Available online: http://www.cpasbru.irisnet.be/fr/index.asp?ID=66 (accessed on 27 August 2018) [our translation]. |

| 42 | Interview with Lynn Dewitte, Brussels, 30 August 2018 [our translation]. |

| 43 | Interview with Tammam Ramadan, Brussels, 30 August 2018 [our translation]. |

| 44 | Interviews with Lynn Dewitte and Peter Van Rompaey, Brussels, 30 August 2018 [our translation]. |

| 45 | Two of the musicians held Syrian passports that were expired. Moreover, the Syrian passport is not eligible to travel so some countries, like in Morocco where the band could not take part to a big world music festival. |

| 46 | Since the Syrian embassy in Belgium is considered functional again, musicians are required to renew their passports, but are reluctant to support financially and symbolically a regime from which they had to flee. |

| 44 | Interview with Tristan Driessens for “La Musique, moteur d’émancipation” [Music, the engine of emancipation], RTBF 26 December 2017 (9’40). Available online: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fs8eqTMLsSY&t=36s (accessed on 18 September 2018). |

| 48 | Figures provided by Muziekpublique on 31 August 2018. |

| 49 | Interview with Lynn Dewitte, Brussels, 30 August 2018 [our translation]. |

| 50 | Description on the crowdfunding website Available online: https://www.kisskissbankbank.com/en/projects/refugees-for-refugees-new-album (accessed on 30 December 2018). |

| 51 | Interview with Hussein Rassim, Brussels, 6 September 2018. |

| 52 | Interview with Tammam Ramadan, Brussels, 30 August 2018 [our translation]. |

| 53 | Interview with Peter Van Rompaey, Brussels, 30 August 2018 [our translation]. The present seems to prove him right: at the time of writing, a crowdfunding launched by the association for the production of the band’s second CD is struggling to achieve its objective. |

| 54 | Interview with Hussein Rassim, Brussels, 6 September 2018. |

| 55 | This last piece, despite being the only one to explicitly refer to the reasons which made the musician escape—or precisely by that virtue—became the title song of the album (“Amerli”). |

| 56 | Transglobal World Music Charts website. Available online: http://www.transglobalwmc.com/charts/best-of-2016-chart/ (accessed on 4 September 2018). |

| 57 | Although out of reach of this article, it should be noted that “these aspects of pride should be taken seriously” (Cabot 2016, p. 18). |

| 58 | We unfortunately did not have any interview with him about his political investment and therefore do not know if he is running for reasons related to migration, artistic or other issues. |

| 59 | Interview with Peter Van Rompaey, Brussels, 30 August 2018 [our translation]. |

| 60 | We do not have the opportunity to tackle this issue in the limited framework of this article, but Laborde (2012) illustrates the various ways of being considered as a professional world musician. |

| 61 | Qotob Trio 6 October 2017; Wajd Ensemble 24 August 2017 and 13 October 2018; Nawaris 27 January 2018; Damast Duo 13 October 2018 … |

| 62 | Of the other two musicians, one left the project because she did not accept the precarious recording conditions; the other was a Belgian musician invited to the album. |

| 63 | The percussion player Simon Leleux was hired for his musical skills and his ability to adapt to different repertoires, which no refugee percussionist presented. |

| 64 | After having balanced the whole I analyzed this was due to many factors, among which my own experience in the production; my missing skills in Tibetan, Pashto and Urdu language; the fact that musicians who had left the project did no longer want to talk about it (see above). |

| 65 | More generally, Georgiou and Zaborowski (2017, p. 3) note that the presentation of refugees by the European media has changed in the course of the year 2015. The sympathetic reaction of a large part of the press during the summer and particularly in early autumn 2015 has gradually given way to mistrust and, in some cases, hostility towards refugees and migrants. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).