2. Overview of Treasury Editions

The first treasury edition focuses on the time period beginning in the mid-1970s and concluding in 1981, with a general emphasis on the widely accepted narrative that hip-hop’s origins can be traced to community center parties located in the Bronx. It is at these parties that disc jockeys (DJs), such as Kool DJ Herc, began experimenting with multiple turntables to blend together existing drum breaks into extended patterns that were meant to energize those in attendance (

Fricke and Ahearn 2002). Much of the story that follows focuses on the DJs, such as Grandmaster Flash and Afrika Bambaataa, who rose to prominence after Herc was sidelined in a dramatically-depicted altercation involving a knife-wielding audience member. Along the way, masters of ceremonies or microphone controllers (MCs) were integrated into these DJs’ performances to add rhymes over looped drum tracks.

Other major characters in the first treasury edition include Russell “Rush” Simmons, Sylvia Robinson, and other burgeoning managers, producers, or record executives who competed to either cash-in on hip-hop as an assumed short-lived fad or in nurturing hip-hop toward sustained commercial success. While the popular breakthrough of studio-produced hip-hop recordings is credited to “Rapper’s Delight” by the hastily-assembled Sugarhill Gang in 1979, it is actually Kurtis Blowe (managed by Simmons) who earns the first official gold record in hip-hop history with his song, “The Breaks”. The first treasury edition of Hip Hop Family Tree climaxes in dramatic fashion with a legendary rap battle between Busy Bee Starski and Kool Moe Dee.

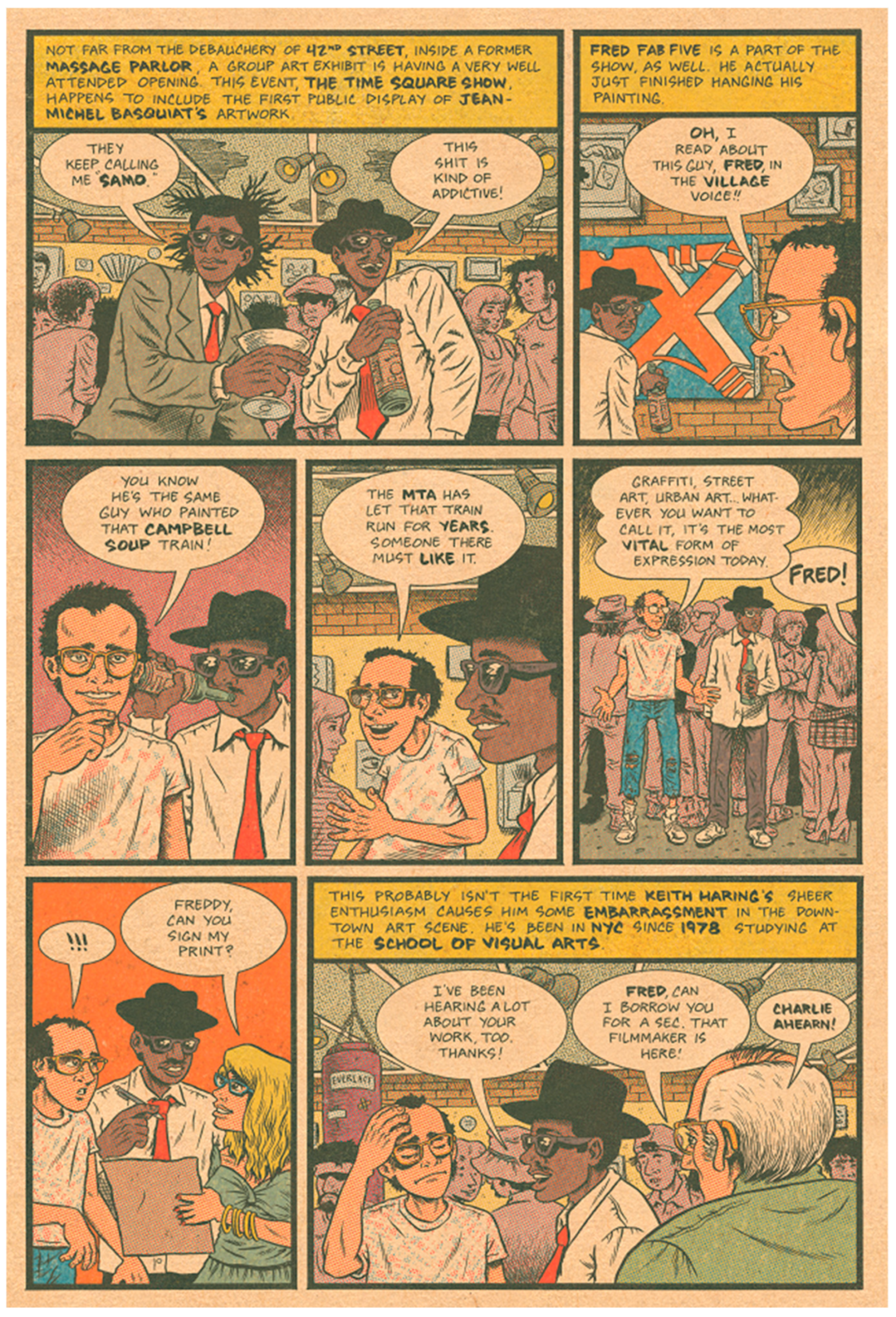

Readers who are interested in exploring intersections between hip-hop culture and visual art will find that the first treasury edition includes a notable thread detailing Fab 5 Freddy (Fred Brathwaite) and his development as both a graffiti artist and as a hip-hop pioneer. This thread depicts Braithwaite’s involvement with Lee Quinones and his Fabulous Five crew in tagging Warhol-inspired Campbell’s soup cans along the sides of subway trains. The recognition and media attention that comes along with this high-profile act leads to later art shows for Braithwaite in Rome and also in Manhattan art galleries, where he is in contact with other street-inspired artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring (

Figure 1). Through these connections, Braithwaite is shown striking up friendships with Debbie Harry and Chris Stein from the popular new wave band, Blondie, who eventually use his moniker in the lyrics of their single, “Rapture”, and also include Braithwaite, Quinones, and Basquiat in the accompanying music video.

The second treasury edition covers the years from 1981–1983 and continues to use a series of brief vignettes to intermittently describe the growing influence and visibility of hip-hop culture and graffiti artists in fine art galleries and venues in downtown Manhattan. In one of these vignettes, Piskor details events surrounding the Braithwaite-curated art show entitled, “Beyond Words: Graffiti Based, Rooted, Inspired Works”, held at the Mudd Club. The focus of another vignette is on Malcolm McLaren’s inclusion of hip-hop musicians, dancers, and graffiti artists as an opening showcase prior to a concert by the new wave band, Bow Wow Wow. Fab 5 Freddy and Futura 2000 were included as featured visual artists in the latter event, whereas the former event included works of art by Haring, Basquiat, Rammellzee, Dondi White, Kenny Scharf, Zephyr, and others.

The second treasury edition also documents the production of two films on the subject of hip-hop culture that featured graffiti and street-inspired artists in prominent roles. More specifically, Lee Quinones and Lady Pink played the lead roles in Charlie Ahearn’s

Wild Style (

1983) alongside Zephyr and Fab 5 Freddy;

New York Beat Movie—later re-titled

Downtown 81 (

2000)—featured Jean-Michel Basquiat as the main character, with Quinones and Fab 5 Freddy this time in supporting roles. While

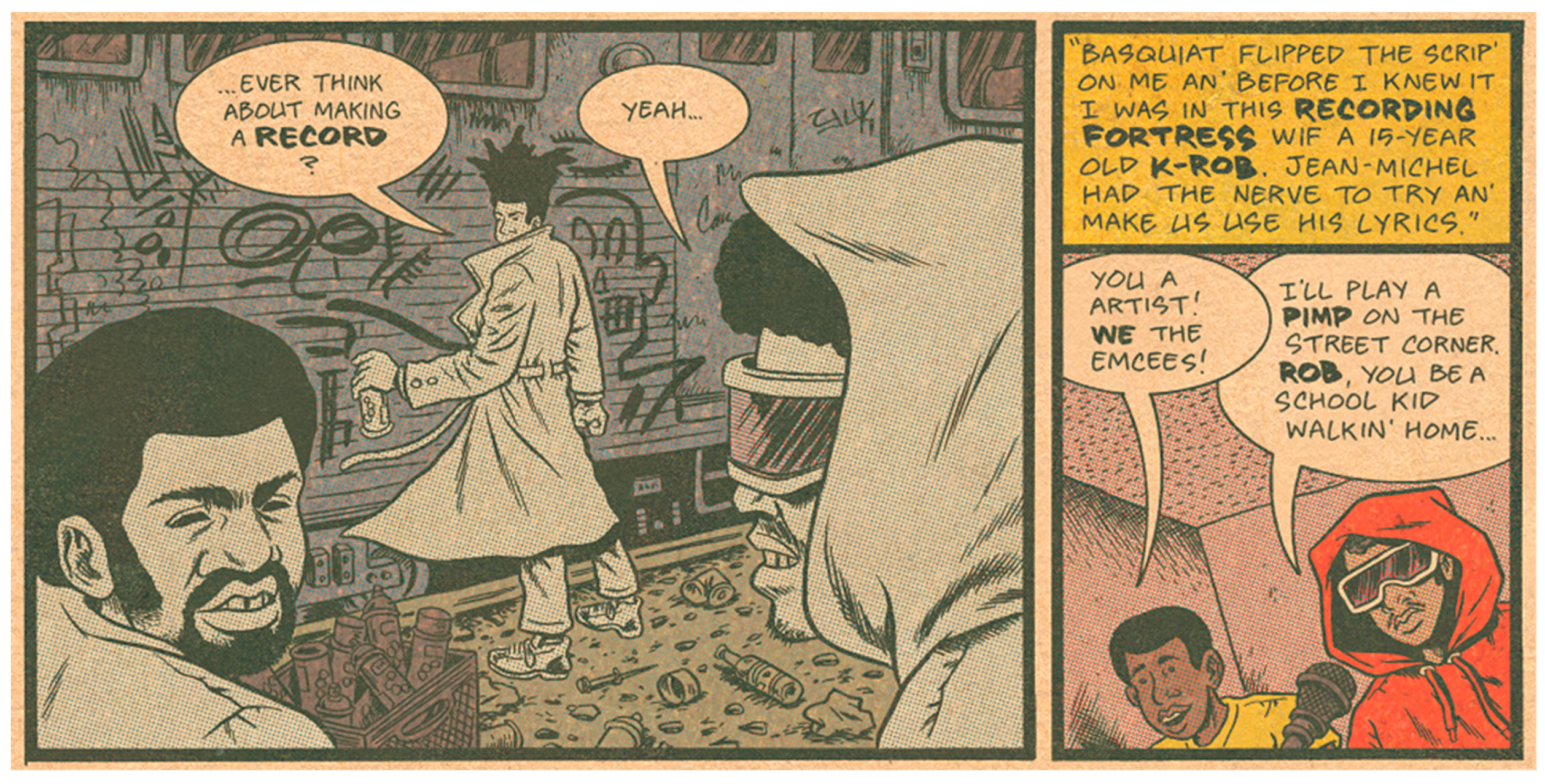

New York Beat Movie also included some of Basquiat’s collaborative musical work on its soundtrack, Piskor rightfully turns his attention more toward Basquiat’s musical ventures through his legendary involvement in the production of the hip-hop song, “Beat Bop”, by K-Rob and fellow visual artist, Rammellzee (

Nosnitsky 2013) (

Figure 2).

Elsewhere, separate story threads in the second edition emerge that are more loosely related to art and design. For instance, some readers may be interested to find that Chuck D (Carlton Ridenhour) was a graphic design major at Adelphi University who used his skills to create logos for his earliest hip-hop groups before eventually leading Public Enemy to critical success. Similarly, Piskor reveals how hip-hop producer, Rick Rubin—then still an undergraduate at New York University—took such care in launching his independent record label (Def Jam Recordings) that he hand-designed the company’s iconic logo with resources available from Estee Lauder’s art department where his aunt was employed. More generally speaking, the second treasury edition of Hip Hop Family Tree also traces the growing success of hip-hop music through Afrika Bambaataa’s “Planet Rock”, the social consciousness of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s’ “The Message”, the emergence of a west coast rap scene, and the earliest days of Run-DMC’s career development.

The third treasury edition focuses on the years 1983 and 1984, with the ongoing thread on visual art shifting its attention to the work of Martha Cooper and Henry Chalfant. This pair of photographers became interested in documenting the emerging hip-hop scene, primarily through images of graffiti on subway trains, and their collaboration resulted in the publication of a book on the subject (

Cooper and Chalfant 1984). Chalfant also collaborated with Tony Silver in producing a documentary,

Style Wars (

1983), that addresses the conflicts that graffiti artists face not just from legal authorities but also from parental disapproval, traditional fine art communities, and in competition with one another. Many of the artists featured in

Style Wars—such as Mare 139, Dr. Revolt and Cey Adams—go on to have successful careers designing logos or even sculptural trophies for Black Entertainment Television, MTV, and several notable musical groups.

As in the previous edition, Piskor once again takes time to trace the emergence of a notable hip-hop musician—in this case, Lawrence Parker—who literally makes his mark as a graffiti artist before finding critical success as a musician. Through Piskor’s comic art, readers learn that Parker likely developed his recording pseudonym, KRS-One, as a graffiti tag before ever committing his lyrics to record. Large portions of the third treasury edition also focus on the growing acceptance of notable rap acts, such as the Fat Boys and Run DMC, as they begin to find mainstream commercial success during this time period.

The fourth and final treasury edition features content from the years 1984 and 1985. In comparison to the previous editions, this final installment seems to place less emphasis on the role of visual art in hip-hop culture and contains only a few passing references to the topic. In shorter passages than before, Piskor details graffiti artists—Phase 2 and Brim—who respectively participate in

Steven Hager’s (

1984) book project on the history of hip-hop or the similarly-themed documentary produced by the British Broadcasting Corporation (

Beat This: A Hip-Hop History 1984). There are also passing references to KRS-One’s continued involvement in graffiti alongside Ced Gee, and also to Schoolly D who designs the cover art for his own self-produced 12-inch single.

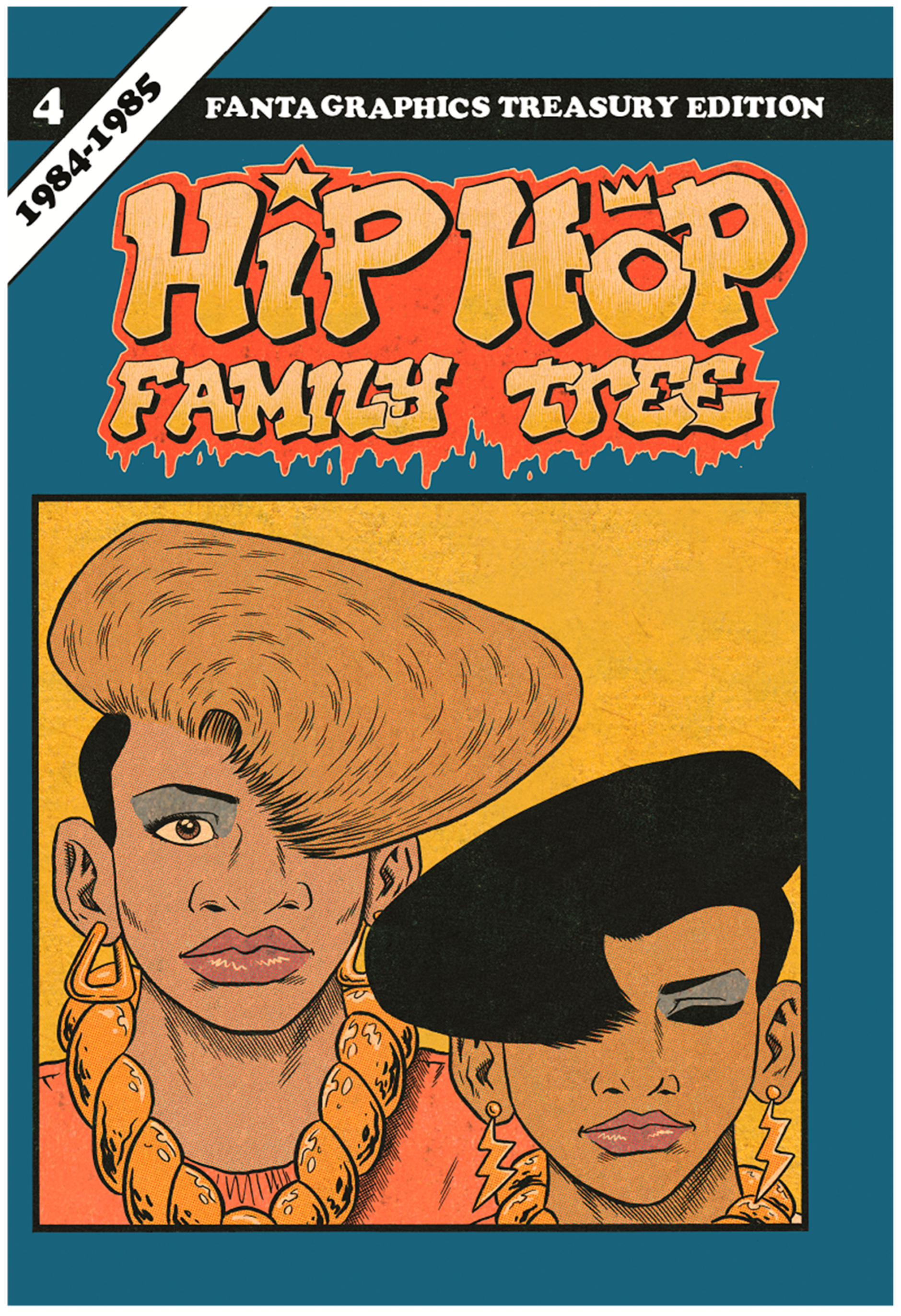

Although visual art is featured less prominently, the fourth edition does devote more space to social justice issues and the growing presence of women in hip-hop as musicians with sustainable popular success. Salt ‘N’ Pepa are featured both within the storyline and on the cover art of this edition (

Figure 3), and Piskor continues to document the career trajectory of Roxanne Shante as well. In terms of social commentary, the fourth edition offers more extensive sections looking critically at the proliferation of crack use in low-income urban communities, and the forceful reaction of the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) to this phenomenon through the use of V-100 commando tanks. Similarly, Piskor also describes deadly police confrontations with MOVE, a controversial Black liberation and back-to-nature organization in West Philadelphia, that also occurred during this time period. This section concludes with details about the subsequent movement to respond to these acts and others like them through politically-charged hip-hop lyrics and recordings.

3. Relevance to Art and Visual Culture Educators

On the most basic level, Piskor’s collected work is notable for blending together what may seem as two distinctly different genres of popular culture—hip-hop and comic books—and these volumes can be enjoyed and appreciated by fans of either. It is similarly obvious that Hip Hop Family Tree can also serve as an engaging educational tool for those interested in studying the history of hip-hop. On a deeper level, however, these treasury editions can serve as a supplementary resource for art and visual culture educators to use with their students when introducing postmodern principles, the use of historical and arts-based research methods, and in discussing a broad range of social justice and identity issues.

3.1. A Resource for Teaching Principles of Postmodern Art

When introducing the complex topic of postmodern art, secondary and higher education instructors may consider making comparisons to hip-hop music (

Broome 2015) as a way to connect students’ interests to hard-to-grasp postmodern principles, such as appropriation, recontextualizaton, and layering (

Gude 2004). These postmodern principles are often recognizable in

sample-based hip-hop music (

Schloss 2004) where sounds are borrowed—or appropriated—from existing sources and then recontextualized and layered with other sounds to create new songs with potentially new meanings for these sampled components. Interestingly enough, Piskor’s approach in creating

Hip Hop Family Tree is also generally congruent with these postmodern principles and hip-hop aesthetics as well, as he employs several subtle uses of appropriation within select sections of these graphic novels. Most obviously, Piskor utilizes appropriation through the occasional layering of scanned images of musicians, album covers, book covers, and still-frames within a number of panels in his comic narrative, particularly in the fourth treasury edition.

In other instances—and in a manner similar to hip-hop musicians who sample from their own predecessors—Piskor cleverly appropriates and references historical conventions from within the comic book and animation industries as well. As an obvious example, the new art featured on the outside casing of the first box set is rendered in a style similar to classic silver-age comic book covers complete with a faux price tag of ten cents and a seal from the long-defunct comics code authority. Furthermore, the coloring of

Hip Hop Family Tree is largely executed through the use of Ben-Day dots as a seemingly intentional reference to the production standards of comic book publishers during the era depicted within Piskor’s graphic novel (

Brown 2013). Less obviously, Piskor also incorporates popular culture iconography into the periphery of his text by hand-drawing appropriated imagery from other comic or animated sources such as Inspector Gadget, Beavis and Butthead, Archie Comics, and Fat Albert (with this latter image slyly implied to represent a young Biggie Smalls). Given the multiple uses of appropriation within

Hip Hop Family Tree, art teachers may consider mixing some of these examples in with select hip-hop songs as a way to augment students’ understanding of the postmodernism principles of appropriation, recontextualizaton, and layering.

3.2. A Catalyst for Considering Historical or Arts Based Research

Art and visual culture educators working in higher education may also find Hip Hop Family Tree to be a useful resource when instructing introductory coursework on research methods for Master’s students. At its core, Hip Hop Family Tree is a graphic representation of the history of hip-hop and, as such, may serve as a motivational springboard for novice researchers in considering historical or arts-based approaches. In terms of historical methodology, Piskor’s work may not hold the same rigor as that of a formally trained doctoral-level academic specializing in historical methods, yet the scope of his research appears to be extensive and thorough in terms of reviewing primary and secondary sources of literature, music, film, and other media. The point to impart on higher education students, then, may not be to uphold Piskor’s use of research methods as a shining academic exemplar, but rather to broaden students’ minds as to conducting historical research on topics of interest related to popular visual culture. Hip Hop Family Tree can be used to show students that historical research in art does not have to be limited to the confining boundaries of traditional conceptions of Western fine art.

Similarly, higher educators could also use Piskor’s graphic novel as a catalyst for encouraging graduate students to consider alternative or unique ways to display their data or structure research findings. Ongoing developments in qualitative research have opened doors for possibilities in

arts-based research, or ways in which art making can be used for collecting, interpreting, and analyzing data, or in presenting findings (

Cahnmann-Taylor and Siegesmund 2008;

Greenwood 2012). For arts-based researchers, data does not always have to be displayed as numbers or through the use of formally written academic language; instead data can be shared, analyzed, or discussed through almost any type of creative arts including, but not limited to paintings, poetry, theatrical productions, or even as graphic novels. Some arts-based researchers, such as

Nick Sousanis (

2015) and Sally Campbell

Galman (

2007,

2013), have already received notable attention for using comic book formats in their work, and a number of art educators have experimented with these methods as well (

Carpenter and Tavin 2010;

Duffy 2009;

Flowers 2017;

Jones and Woglom 2013). Because of the accessibility of its content, writing style, and potentially interesting subject matter to students, the

Hip Hop Family Tree series could easily serve as a motivational resource in spurring fledgling Master’s students to consider using comic art or other arts-based methods in their future research.

3.3. Discussion of Social Justice and Identity Issues

As with any other instructional resource, it’s important that art and visual culture educators critically examine

Hip Hop Family Tree prior to using it as a teaching tool. As a historical exploration of hip-hop culture, the text does contain several frank portrayals of the drug use, violence, explicit language, and misogynistic content that has at times accompanied certain situations and sub-genres surrounding hip-hop. While these depictions may provide opportunities for the critical deconstruction of popular imagery often associated with hip-hop culture (

Chung 2007;

Clinton 2010), other secondary teachers may find it wise to carefully screen the text before selecting specific excerpts to share with their students.

It should also be noted that Piskor is a White male (as am I), and that any subjectivities that may come along with his identity present worthy discussion points in analyzing his depiction of women or the historical development of a culture that largely grew out of Black urban environments. Initially, instructors could encourage critical dialogue related to the potentiality of such subjective representations through simple prompts asking students to openly consider the ways in which different characters and situations are portrayed in Piskor’s narrative. Are some characters portrayed in semi-heroic proportions similar to those found in superhero genres of comic books? If so, why were those particular characters chosen to be portrayed in such a manner? Is the portrayal of women ever problematic in the course of Piskor’s narrative? Is it possible that some figures essential to the history of hip-hop have been reduced to simplified comedic caricatures in terms of the way that they are depicted or speak? Is the use of such exaggerations ever problematic given that these characters are based on living persons rather than fictional heroes and villains? Is the use of phonetic vernacular dialogue—a practice with a long-running tradition in comic art (

Pekar 1996)—ever problematic, given the context of the narrative and identity of the author? Such critical discussions may prepare students for more intense conversations that may arise in reaction to specific vignettes from

Hip Hop Family Tree that detail forceful police interventions in Black communities. Several scenes (particularly those depicting the LAPD’s use of commando tanks, and the Philadelphia Police Department’s deadly confrontations with MOVE) are ripe for fostering classroom discussions on social justice issues, and also the deft ways that skillful artists approach such topics.

Although it is important to look at any text critically, Hip Hop Family Tree presents itself as a comprehensive work masterfully created by an authentic and genuine devotee to both hip-hop culture and the history and craft of comic book art. One gets the sense that Ed Piskor is passionate about both topics, fully immersed in both cultures, and that he would be just as enthusiastic, intelligent, and articulate in discussing the influence of Melle Mel, Dr. Dre, and the Beastie Boys as he would when discussing the impact of Jack Kirby, Harvey Pekar, and Robert Crumb on the art of making comics. In the end, Hip Hop Family Tree is a welcome and important addition to both scholarship on the history of hip-hop and to the graphic novel format. Art and visual culture art educators may find it as a useful resource in introducing aspects of postmodern art, in fostering early graduate students to consider historical and arts-based research methods, and in discussing relevant social justice and identity issues with students.