Abstract

In this paper, I will examine how Japanese documentary filmmaker Tsuchimoto Noriaki (1928–2008) tackled the issue of visual ethics through the representation of Matsunaga Kumiko and Kamimura Tomoko—two young female patients known for the symbolic roles they each played in the history of Minamata disease. I will introduce the ethical challenge Tsuchimoto encountered upon his first visit to Minamata in 1965—especially how he grappled with the question of filming subjects (shutai) who were unconscious and/or unable to express whether they approved the act of filming or not—and how such conundrums were reflected into his representation of Kumiko in her hospital bed. For the analysis of the representation of Tomoko as seen in Tsuchimoto’s documentary, I will bring in W. Eugene Smith’s photograph “Tomoko and Mother in the Bath” as a point of comparison to explore what could be an ethical representation of Minamata disease patients, including the issue of photographs that seem to beautify the tragedy. Based on the above examinations, I will argue that the challenges Tsuchimoto faced upon representing unresponsive subjects and the very struggle to find a way to capture them as humans, not as patients or victims, altered his manner of artistic and political involvement with Minamata disease. And in the current post-Fukushima era, the issue of ethical representation that he kept exploring carries even more significance upon representing disasters.

Prior to Tsuchimoto’s first visit to Minamata in 1965, numerous journalists and artists covered this strange disease, but only a handful continued their lifelong engagement with Minamata.1 One of them was Kuwabara Shisei (1936–present), who started photographing patients in 1960. Kuwabara strived to find a way to present patients without repelling the audience, as he argues that “[t]he more shocking the subject is, the more effective it might be [to use] a soft photograph.”2 One example of this soft photograph is his best known work—the close-up photograph of Matsunaga Kumiko’s eyes. The most notable artist who worked on Minamata disease, however, would undoubtedly be the local author Ishimure Michiko (1927–2018). Ishimure’s novel, Paradise in the Sea of Sorrow (Ishimure 1969), brilliantly described life in pre-modern, pre-disaster Minamata and Shiranui Sea in stark contrast to the chaos and tragedy brought on by the disease, and also presented the lives and voices of patients who were often rendered voiceless. As a result, Minamata disease, and especially its unresolved status, attained renewed awareness nationwide. This socially active author often collaborated with other journalists and artists, including Kuwabara and Tsuchimoto.

Through his 45-year career, Tsuchimoto Noriaki explored many social issues in his documentaries, but it is unquestionable that his name is most closely associated with Minamata—the place where he was “reborn” as a filmmaker. The questions of how to capture Minamata disease patients without objectifying them or putting them on display, and also from what position to represent them, were the issues Tsuchimoto encountered when he visited Minamata for the TV documentary, The Children of Minamata are Living (Minamata No Ko Wa Ikiteiru 1965).3 For this documentary, Tsuchimoto followed Nishikita Yumi, a female college student and a volunteer case worker, as she visited the Minamata Municipal Hospital and the areas considered as the disease’s epicenter. Despite his initial enthusiasm for reporting the state of Minamata disease almost ten years after its official confirmation, the rejection by villagers that he encountered left him emotionally devastated. He recalls his experience in the article, “Document in Adversity” (Gyakkyō No Naka No Kiroku):

[O]n the first day I entered Yudō, the area with the large number of patients, I was bitterly informed that its residents regarded [me] with loathing. It was February 1965, when Minamata disease [patients] were treated like aftereffects and secluded inside the area. While we were shooting the panoramic view of the area with the wide lens, housewives who were gathered at one of the houses started to raise a clamor. I was unaware of a child patient among them, but they harshly blamed us, complaining that we filmed [the child] without permission. I listened in without a word of justification. After that incident, both my cognitive faculty and speech completely ceased to function. In short, I was destroyed. Torn apart by the intuition that “I do not have the right to film Minamata disease,” I heard my own internal voice, “You don’t have the energy to shoot a film, so just quit,” endlessly. Unable to turn the camera to anywhere, I just stood on top of the stone wall by the wharf …Eventually, I saw a fragment of translucent and shiny tea cup at the bottom of the sea … “Can we focus [the lens] on it?” With this as a cue, we filmed several shots of the china at the bottom of the sea for a long time in silence … Filming it was the only way for us to start again. Namely, it was merely “a document at a standstill” (ashibumi no kiroku). But only by doing so, I could barely endure the profound sense of setback as a filmmaker. Without this experience, my relationship with Minamata until today would not have been born.4

After years of suffering discrimination from Minamata citizens at large and even neighbors, patients and their family members grew very sensitive to the presence of the media, particularly of the camera. In their eyes, the media in 1965 were mostly curious bystanders who “snatched” their images for a use which, though potentially well-meaning, might make their lives even harder. Hence, distrust and rejection of men with the camera and other recording devices was nurtured. Even though Tsuchimoto considered himself as an outsider to the established media, villagers would have registered him as “one of those media people” all the same. He took the rejection to heart, to the point that he even doubted his profession as a filmmaker, especially because he imposed on himself a policy of always asking for permission to film his subjects prior to actually filming them.5 This moment of standstill, however traumatic it might have been, allowed him to take steps forward in a form of independent documentary making five years later, namely without any connection to the mainstream media. Moreover, it strongly urged him to contemplate further on the role of documentary film and the issue of privacy, particularly in relation to Minamata disease.

Tsuchimoto’s encounter with, or rather “witnessing” of, Matsunaga Kumiko, was exactly in line with this ethical question that he was struggling with, as he writes in “Minamata Note” (Minamata Nōto):

It is easy to film her because she is unresponsive and thus unable to reject [her being filmed]. I was supposed to simply film her just as many other visual media professionals did. Certainly, I felt pain against her being compelled into gradual oblivion due to the indifference of Minamata citizens, and filmed her with anger while branding onto myself what the act of capturing (toru; とる) her image means. However, ever since the moment when she endured the close-up without blink, rejection, and pain, I could neither suppress nor appease inexpressible bewilderment until I completed the piece. Why, for what, and from what position am I filming? Kumiko compelled me to ask myself this question.6

As Tsuchimoto points out with an implied sense of cynicism toward the existing media coverage of Minamata disease patients, the physical or technical ease of capturing the image of an immobile Kumiko marks a sharp contrast with the psychological difficulty of executing it. This is because the act of filming, according to him, should be a form of mutual interaction between image-makers and their subjects. Alternatively, if Tsuchimoto found it easy, he would be no better than the Minamata citizens whose “indifference” compelled Minamata disease patients into oblivion. In the fourth sentence, he uses the verb “capture” (toru; とる) in hiragana instead of “film” (toru; 撮る) in kanji, with the implication that image-makers and their act of “capturing” could lead to “taking” (toru; 取る) something away from subjects, or even “stealing” (toru; 盗る) something from these subjects by force. Here, his finger points at Minamata citizens as the indifferent bystanders, and also at himself as a filmmaker. “Why, for what, and from what position am I filming?” This is Tsuchimoto’s self-questioning toward his act of filming a subject who neither blinks nor rejects the camera—that is, the subject with whom he cannot interact, the one who cannot “speak for” herself. And this self-questioning leads to a larger question of how one should address such a subject.

Indeed, posing questions on issues related to the ethics of filmmaking is an essential part of Tsuchimoto’s career as a filmmaker-theorist, and he often examines the position of filmmakers in his writing. In the article, “Film is a Work of Living Beings” (Eiga Wa Ikimono No Shigoto De Aru), he states:

That I chose filmmaker as a profession means that I am not bare-handed and bare-faced as I am armed with the camera, and I impose on myself a deepened awareness of how to remain bare as a human being while retaining the functions of such a recording device.7The condition where the camera is present is not normal, and even if it is, it creates the relationship between the ones filming and the ones being filmed, resulting in a mutual sense of tension.8Documentary film steals people, cuts out and shoots portraits, and collects their words … As long as I singlehandedly monopolize such physical weapons as lens, film and tapes, and possess them as power, my “subjects” (hishatai) and I would never be equal.9

Tsuchimoto’s profession as a filmmaker makes him inseparable from the camera, which can also become a weapon figuratively depending on the context, and he is keenly aware of the danger that the camera as a weapon imposes on his subjects. Furthermore, the power of the camera as a weapon comes with the ability to not only “steal people, cut out and shoot portraits, and collect their words,” but also publicly exhibit what it captured—the ability to document a subject’s life as a power that could be used and/or abused. He is also sensitive to how the presence of the camera changes the ordinary into the extraordinary, as well as the position of the one who possesses it and the one who does not. There are always spaces in front of and behind the camera, and people in front of the camera are rendered in the passive term of hishatai (subject), which literally means “the body exposed to the gaze of the camera.” Tsuchimoto’s physical presence within his film, therefore, might be as much the manifestation of the constructed-ness of documentary films as his intention to also expose himself to the gaze of the camera, which indicates his urge to be on equal terms with his hishatai, if only momentarily.

Based on the above-discussed incident of standstill and also the inherent psychological difficulty of filming unresponsive patients, how did Tsuchimoto deal with the potential harm the presence of the camera poses to his subjects in The Children of Minamata are Living? This TV documentary features two main types of voiceover: that of a female narrator explaining the overall situation from the protagonist Yumi’s perspective and Yumi’s own voice that is interwoven between the narrator’s voice. Approximately two minutes into the documentary, the image of Yumi with her voiceover explaining how a young patient is like a wax doll (rō ningyō) and unable even to recognize her own parents is abruptly intercut by the medium shot of a little girl’s frail right arm popping out of the futon (Figure 1). The arm then slowly lowers and hides beyond the futon. After this ten-second shot, the extreme close-up of Kumiko’s blinking right eye cuts in (Figure 2). This six-second shot is then followed by a series of still images before the location of the scene shifts from the city of Kumamoto to Minamata. Who the arm belongs to remains uncertain, yet I assume it belongs to Kumiko’s judging from the order of shots as well as the somewhat ironic shot-voiceover pairing. Yumi’s voiceover does not specify which patient she is referring to, and whether she is speaking of a single patient or multiple patients is unidentifiable due to the fragmentary nature of the voiceover as well as the structure of the Japanese language. However, considering that Kumiko’s byname is ikeru ningyō, I think it likely that the term “wax doll” is used to refer to Kumiko, or at least someone in a condition similar to hers. Then, the pairing of the term “wax doll,” namely a lifeless and immobile object, with the images of Kumiko’s moving arm and eye is rather poignant. There are two ways to describe these subtle movements: an arm and an eye that do indeed move if only slightly, and an arm and an eye that only move slightly. Whichever the viewer’s take might be, this subtle shot-voiceover pairing already begins to challenge the common tendency of putting these patients under fixed categories. The inserted image of the arm, while a gesture of invitation to Minamata, already encapsulates the tragedy that happened to human bodies by presenting the involuntary (and, most likely, unconscious) body movements patients exhibit. And the close-up of Kumiko’s eye, instead of emphasizing her beauty, speaks to her status as an object of gaze who cannot gaze back; that is, as the being who lost touch with her surroundings.

Figure 1.

A right arm raised in the air. Still from The Children of Minamata are Living (1965), director Tsuchimoto Noriaki.

Figure 2.

The extreme close-up of Kumiko’s right eye. Still from The Children of Minamata are Living (1965), director Tsuchimoto Noriaki.

Another shot of Kumiko is included at the very end of the two-minute handheld tracking shot, in which the camera traces the path from the Minamata Municipal Hospital’s main entrance to its Minamata disease ward. The sheer distance traveled by the camera reveals how deep inside the hospital building the patients were hidden away. As Tsuchimoto recalls, this special ward, which was located next to the mortuary and the contagious disease quarantine ward, was “the space for death and contagious disease where hospital visitors would not step in under any circumstances.”10 Indeed, while the entrance and the general waiting room are busy with the flow of visitors, past the waiting room the corridors are quiet, and once in the Minamata disease ward there are only doctors, nurses and patients. This distance is physical as well as psychological since, as the narrator reveals, both in the town of Minamata and the hospital, the presence of Minamata disease has faded and people no longer talked about it.

The hospital also plays a crucial role here for this process of concealment. Being part of the municipal government, this hospital is a shelter as well as a prison for patients, particularly due to the secluded location of this special ward, which underlines the undeniable symbolism of its being a place of no return. To battle against this general inclination to undermine the significance of Minamata disease, the unintended underexposure and overexposure included in the shot provides unexpected effects. The long tracking shot covers both the exterior and interior of the hospital. As a result, the section of the general waiting room crowded largely with Minamata citizens—those “indifferent” citizens Tsuchimoto criticizes—is underexposed and mostly veiled in darkness, as if to embody their not-so-laudable deeds to their neighbors. On the other hand, at the Minamata disease ward, the well-lit sections with the windows and other openings nicely illuminate the subjects, including Kumiko. Through this natural lighting, Minamata disease patients are brought out as those who deserve to be in the spotlight and be treated with respect, not contempt. While the natural light helps to soften the impression of the severely-ill Kumiko, capturing her image is no easy matter psychologically. Upon facing her, both Tsuchimoto and his cameraman backed off, revealing the conflicting emotions of being unable to turn the camera to her while finding it even harder to face her without it.11 In this shot, Kumiko is in bed but not sleeping, unlike in the director’s cut of Minamata: The Victims and Their World (Minamata: Kanja-San To Sono Sekai 1971) in which she is captured asleep, as I will discuss shortly. Is there be any difference between filming a patient asleep and one not fully conscious but neither asleep?

What is suggestive is not only Kumiko’s on-screen presence but also her absence. As a matter of fact, she does not appear in the wider-circulated 120-min version of Minamata: The Victims and Their World; however, she does appear in the 167-min director’s cut version.12 The scene begins with the establishing shot of the building, with the sign “Rehabilitation Center.”13 The tracking shot through the corridor that follows is reminiscent of the one in The Children of Minamata are Living, though shorter this time, and after passing by one young male patient in a wheelchair, the camera finally stops to capture the arithmetic lesson for some congenital Minamata patients. After this sequence, the camera focuses back on the male patient captured earlier, Yamamoto Fujio, and then shifts to the short sequence of Kumiko in bed sleeping. While the scene up to Fujio remains largely the same between two versions of Minamata, Kumiko’s shots are deleted from the shorter version. The sequence with these two patients appearing after one another is actually significant, since Tsuchimoto was particularly intrigued by them, as he writes in “Minamata Note”:

I would especially like to see Matsunaga Kumiko, who has been confined to bed for more than a decade in the adult Minamata disease ward on the fourth floor, and Yamamoto Fujio, who is in the congenital patients’ ward on the second floor. They are typical Minamata disease patients at the cruelest this disease can be …I go to “witness” Kumiko and Fujio at the Rehabilitation Center because I want to meet human beings that live alone in the psychologically distant world that defies and rejects any interaction. I approach them to face the origin of Minamata disease. Their horrifying existence unsettles the life with Minamata disease that I grew accustomed to.14

For Tsuchimoto, both Fujio, who barely ceases to move, and Kumiko, who barely moves, are the symbols of Minamata disease at its bleakest since they represent “absolute disconnect” (tetteitekina danzetsu) as human beings. In other words, this disease damages and challenges the very aspects of what makes humans human by disabling their interaction with others.15 Fujio’s family largely abandoned him, and thus his shot was kept in the shorter version. However, Kumiko, whose family remained as attentive caretakers, disappeared altogether.

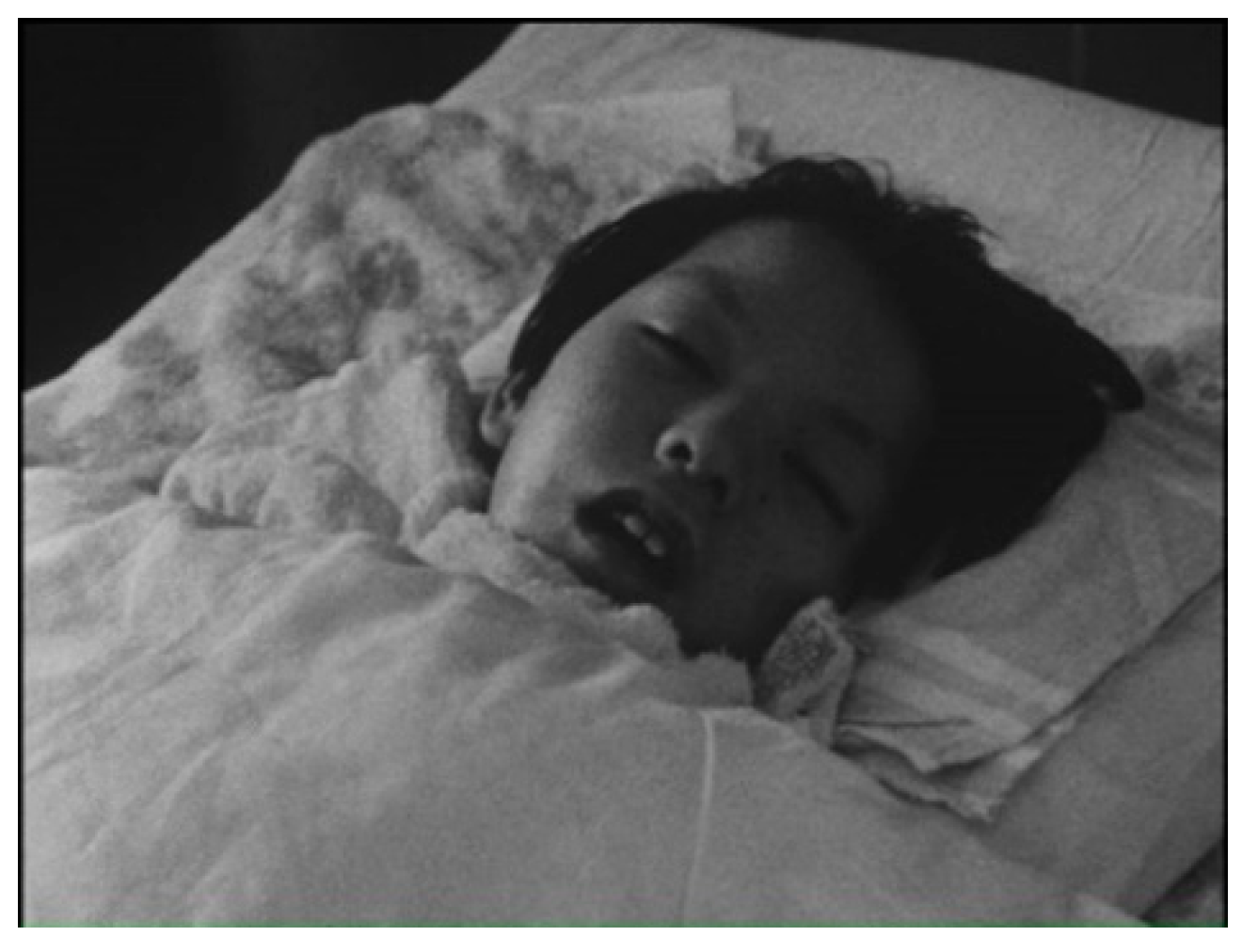

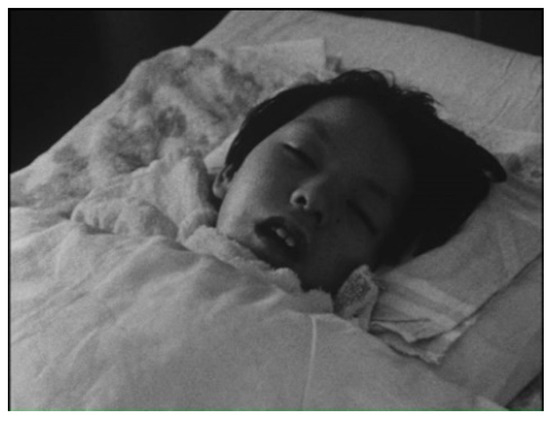

In the short sequence of Kumiko, she is filmed in the medium shot while sleeping with her eyes closed, from the left and then from the right (Figure 3). Without her signature big open eyes, and also without explanation of who she is (her byname ikeru ningyō had been well established by the time of Tsuchimoto’s filming) other than her name and patient number, it might be rather difficult to recognize her just by this image. Two medium shots that both last a few seconds maintain the sense of comfortable distance, allowing the audience to observe her without getting too close to her, if through the non-immediacy of screen. The fact that she is visibly sleeping, instead of laying down barely responsive as in The Children of Minamata are Living (Figure 4), might also make the act of witnessing her feel a little less guilty. At the same time, however, filming her asleep gives Tsuchimoto a different sort of mental qualm from filming her awake but not responsive, again reverting to the question of how to capture a subject who does not return the gaze to the camera. Compared to the image of 15-year-old Kumiko in The Children of Minamata are Living, that of 20-year-old Kumiko in Minamata does not reveal much change at a glance. Yet, Tsuchimoto senses her early decrepitude, already starting to shrink and emitting an odor of old age after the lifelong battle, she has lost the power to thrive and is about to rush away her short life.16 Taking this “aging” factor into consideration might enable a more sensitive reading of the different level of Kumiko’s responsiveness along with the environmental factor. In The Children of Minamata are Living, as the ending point of the long tracking shot, the camera comes to stop to focus on her nicely-lit face, eventually framing her face in the close-up. The youthfulness of an adolescent girl that is sensible through her appearance makes up for her lack of response and movement. In Minamata, the still camera simply frames her in the stable medium shots from both sides; along with the darkness of the room, the fast-asleep Kumiko seems to be almost beginning a gradual process of implosion, thus rejecting the external world even more categorically than before. When facing this rapidly aging woman in a secluded hospital ward, Tsuchimoto might have felt a sense of relief, or felt less guilty, that she is asleep and thus does not return the gaze—aside from the fact that even if she were indeed awake, it would be nearly impossible to tell whether she is returning the gaze or having her eyes open aimlessly. The deletion of Kumiko’s sequence from the wider-circulated version deprives the audience of the opportunity to witness the person who symbolically embodies the ordeal of being a Minamata disease patient, of the life consumed by the darkness of an incurable, man-made (or corporate-made) disease, and awaits her slow death in silence.

Figure 3.

The medium shot of Kumiko asleep in bed. Still from Minamata: The Victims and Their World (1971), director Tsuchimoto Noriaki.

Figure 4.

The medium shot of Kumiko awake in bed. Still from The Children of Minamata are Living (1965), director Tsuchimoto Noriaki.

While Matsunaga Kumiko was known for her beauty despite being a Minamata disease patient, Kamimura Tomoko was identified by the opposite reason—as the embodiment of all the ordeals this disease could possibly impose on a human body. What contributed to her symbolic status was W. Eugene Smith’s photograph “Tomoko and Mother in the Bath,” which shocked and awed the world outside Minamata. Smith and his wife, Aileen Smith, stayed in Minamata from 1971 to 1973 in order to capture the daily lives and moments of political encounters.17 The photograph “Tomoko and Mother in the Bath” was taken at the Kamimura residence’s bathroom in December 1971, and published as part of the eight-page feature story of Minamata disease, entitled “Death Flow from a Pipe” in the 2 June 1972 issue of Life. Out of the eleven photographs included in this story, this photograph is the concluding, and most dramatic, image. While this photograph triggered heated reactions from artists and critics alike, Japanese photographers and filmmakers working in Minamata around the same time raised strong voices of opposition, including Tsuchimoto who criticized it based on Smith’s photographing a naked teenage girl. Although Tomoko could not verbally communicate her feelings, Tsuchimoto claims that her discomfort upon being photographed in such a condition was manifested by her unusually tightened body in the photograph. Tsuchimoto even cites Smith’s photograph when pointing out that young, speech-impaired patients often appear angry and their faces are twitching in many photographs because photographers are unaware that these patients do not want to get photographed. According to him, “[Tomoko’s] body [in Smith’s photograph] is stiffened up. A close look at the photograph reveals how much this girl, who barely entered puberty, is reluctant [to get photographed].”18 In his view, it is ethically wrong to capture the image of a subject who is unwilling to be photographed—the view which reflects his belief of torasetemorau, namely his subjects allowing him to film them, instead of him filming them irrespective of their reactions. As his contemporary, Ōshima Nagisa points out, “[f]or Tsuchimoto, film production is always built upon the principle in which his subjects have to allow him to film them (torasetemorau). And this process of torasetemorau means, on the one hand, to discover a person, company or organization that gives him a material base to produce a film, and on the other, to have his subjects allow him to film them.”19 As the earlier discussion of how the accusation of filming a young patient without permission left him emotionally devastated reveals, Tsuchimoto was a firm believer of establishing communication with his subjects, of getting to know them, before filming them. That is also why subjects such as Matsunaga Kumiko, with whom he could not achieve such communication, posed great challenges to his ethics as a filmmaker. Based on this belief, Smith’s act of exposing an unconsented subject to the gaze of a camera was unthinkable and unethical to Tsuchimoto.

How, then, did he deal with Tomoko as a subject to be filmed? To begin with, Kumiko and Tomoko created a fascinating contrast. While the infantile patient, Kumiko, retained her body relatively undeformed, the congenital patient, Tomoko, born with deformed feet, could never support her own body and her entire body suffered deformation as she aged. On the other hand, unlike largely unconscious Kumiko, Tomoko was conscious, responsive, and “cried out” to express her emotions, as her parents listened to her and “interpreted” her cries to guests on her behalf. The following is how Tsuchimoto, whose lodging was near the Kamimura residence, describes her:

Sometimes, among the boisterous voices of … innocent children of the Kamimura family that live across the street, I hear the inarticulate, voiceless voice—shall I call it a groan or the emotional expression of the vocal cords … Kamimura Tomoko has already turned fourteen. Despite that her period had started early, her eyes glare at empty space and are rolled up into her head, her fingers have bent inward like a crane and been hardened, and her legs are too wilted to even seat herself. The characteristic action of organic mercury poisoning melts and perishes brain cells, robbing humans of what make them humans. However, the activities of stomach, bowel and heart are exempted from direct poisoning. Therefore, while I can still observe the remnant of humanness from the chest and stomach parts, when I compare them with the small-scale skull, bony legs and the twisted waist, [Tomoko’s entire body] appears to us as an indescribable, cruel human body. Yet, though not entirely certain, this girl follows human voices and reacts to them with the slightest sway of facial expressions. Seating her on their laps, her mother and father acknowledge the faintest clues of her emotional swings, interpret them with attentiveness characteristic of parents, cradle and talk to her … I seat myself among visitors and other children and witness such an interpretation of the soul, and thinking of the day when I might be able to talk with her loosens my hardened heart.20

The above quote contains disclosure of very private information, which could lead to a violation of the patient’s privacy. Tsuchimoto’s intention behind violating Tomoko’s privacy in such a manner, however, is to communicate the loss of basic human functions, which is hard to visually represent and thus could otherwise go unnoticed. In that sense, his method of political appeal is similar to that of Tomoko’s parents—to present her body in front of the camera to let it speak for its tragedy. However, this position does not imply that he regards patients’ bodies as mere objects to be captured. It is particularly clear considering the ways in which he includes the sequences of interaction between patients and himself as another subject captured on screen, such as when the filmmakers wait outside until getting invited, signaled by a patient’s gesture of beckoning, to enter the house, and another patient enjoys the moment of interviewing Tsuchimoto instead. Tsuchimoto is sensitive to his communication with these patients, and this is again indicative of his torasetemorau stance. But to what extent such communication is possible is uncertain. The third-to-last section of the above quote does begin with the expression “though not entirely certain,” that is to say, casting a slight shadow of uncertainty about whether Tomoko really understands her surroundings. But Tsuchimoto is evidently inspired by Tomoko’s parents as “interpreters of the soul” and how they make the seemingly impossible interpretation of and communication with Tomoko possible. Therefore, his filming of patients might be torn between inquiry into the interpretations of patients’ inner states provided by their family members, namely the inaccessibility to these patients, and his urge to understand and access their interiority despite the seeming impossibility.

To gain further insight into this conundrum, I shall introduce how Ishimure Michiko describes Tsuchimoto’s first impression of Tomoko:

It is scary to look at Tomoko. At the beginning it was just too painful to bring out the camera. However … while I was talking, I realized that the voice of Tomoko in [her mother’s arms], which I initially thought expressed her anger, instead expressed happiness for the visit of a person she is familiar with. At such a moment, Tomoko’s face looks very beautiful, almost breathtakingly beautiful. Gradually, [her face] came to look that way. It is only when she appears beautiful to me that I can turn the camera to her.21

Such an image of Tomoko, with the impression she leaves in the hearts of beholders, is what Tsuchimoto aims to capture in the scene at the Kamimura household in Minamata. In the first shot, the camera frames Tomoko’s younger siblings and her father and then pans to the left to show her in the arms of her mother, being fed. Throughout the scene, the camera alternates between the image of Tomoko and that of her siblings, sometimes through pan shots and at other times in separate shots. The comparison with her healthy siblings accentuates her helpless state. Furthermore, the degree of physical destruction she suffered due to mercury poisoning is highlighted by their facial semblance and physical differences, which are made visible especially through two sets of pan shots that first show the entire body of Tomoko’s youngest sibling and then frame Tomoko.

The first close-up of her face, which shows her inability to swallow the liquid food at once and her mother scooping the overflowing liquid and putting that back into her mouth is, in a sense, a dehumanizing, exploitative image of Tomoko being put on display for the audience. However, it is not only the tragedy that Tsuchimoto tries to communicate visually, but also the attention and affection that Tomoko receives from her family. The linking of Tomoko with the rest of the family members through the pan shots also indicates her inclusion within the family circle, which was often difficult for the severe congenital patients to retain.22 And this is where Tsuchimoto inserts Tomoko’s “happy” voice as part of the soundtrack, along with her mother’s explanation on the way she reacts to the presence of someone she knows with such a voice. Overlapped with such a “happy” voice is the close-up of Tomoko in her mother’s arms (Figure 5). Their posing is almost exactly the same as Smith’s “Tomoko and Mother in the Bath,” with her mother slightly lowering her chin and looking into her face. The difference, though, is that instead of the darkness that frames their solitary figures in the bath, they are surrounded by the light and the chattering voices of Tomoko’s siblings. In other words, the public nature of the living room and the private nature of the bathroom are symbolically indicated by the degree of darkness. Moreover, unlike photography, which necessarily captures one frozen moment, Tsuchimoto’s film, being a moving image, is capable of capturing even subtle changes in her facial expressions and, therefore, of presenting to the audience the non-dramatized face of Tomoko in the continuing (unstopped) historical time. And the way the audience gradually gets to know Tomoko and her surroundings through this sequence parallels, if temporarily condensed, Tsuchimoto’s own experience with her—from the initial fear to the eventual admiration.

Figure 5.

The medium shot of Tomoko. Still from Minamata: The Victims and Their World (1971), director Tsuchimoto Noriaki.

Tsuchimoto’s involvement with Minamata lasted for the rest of his life, and between the TV documentary in 1965 and the video piece, Minamata Diary: Visiting Resurrected Souls (Minamata Nikki: Yomigaeru Tamashii O Tazunete, 2004), four years before his death, he worked on more than a dozen Minamata documentaries. The encounter with subjects who forced onto him the question of what is an ethical representation of the persons incapacitated of self-expression enriched his thoughts and experiences as a filmmaker, making his devotion to this disaster even more meaningful. In the wake of the earthquake and tsunami in northern Japan and the Fukushima nuclear plant disaster (“3.11”), Minamata disease has received renewed interest as one of Japan’s first and worst environmental disasters. A growing number of artistic and journalistic representations about 3.11 has been produced, and for instance, a couple dozens of films, both documentary and fictional, have been produced with 3.11 as their main subject. And that is why it is essential for artists and journalists involved in this disaster to challenge themselves with the very question Tsuchimoto grappled with. The power of the media should be a catalyst for empowering subjects, and in the age of media proliferation, such power needs to be exercised with caution, with greater mindfulness to the ethics of representation and to the fact that there might only be a thin threshold between the use and abuse of images.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to Michael Raine, Daniel O’Neill, Aaron Kerner, and my colleagues Marianne Tarcov and Soo Mi Lee for their continued support.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Inoue, Miyo. 2018. Exhibition, Document, Bodies: The (Re)presentation of Minamata Disease. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ishimure, Michiko. 1969. Kugai Jōdo: Waga Minamatabyō. Tokyo: Kōdansha. [Google Scholar]

- Ishimure, Michiko. 2008. Eiga ‘Minamata’ (Tsuchimoto Noriaki Kantoku) (1). In Ishimure Michiko Zenshū, Shiranui. Tokyo: Fujiwara Shoten, vol. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara, Shisei. 1989. Hōdō Shashinka. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Minamata No Ko Wa Ikiteiru, 1965. Noriaki Tsuchimoto, director. Tokyo: Siglo, 2006. DVD.

- Minamata: Kanja-San to Sono Sekai, Kanzenban, 1971. Tsuchimoto Noriaki, director. Tokyo: Siglo, 2006. DVD.

- Ōshima, Nagisa. 1978. Dōjidai Sakka No Hakken. Tokyo: San’ichi Shobō. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchimoto, Noriaki. 1974. Eiga Wa Ikimono No Shigoto De Aru: Tsuchimoto Noriaki Shiron Dokyumentarī Eiga. Tokyo: Miraisha. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchimoto, Noriaki. 1976. Gyakkyō No Naka No Kiroku. Tokyo: Miraisha. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchimoto, Noriaki. 1988. Minamata Eiga Henreki: Kioku Nakereba Jijitsu Nashi. Tokyo: Shin’yōsha. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchimoto, Noriaki. 2005. Kiroku Eiga Sakka No ‘Genzai’ Ni Tsuite. In Minamatagaku Kōgi. Edited by Masazumi Harada. Tokyo: Nihon Hyōronsha, vol. 2, pp. 81–112. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchimoto, Noriaki, and Kenji Ishizaka. 2008. Dokyumentarī No Umi E: Kiroku Eiga Sakka Tsuchimoto Noriaki Tono Taiwa. Tokyo: Gendai shokan. [Google Scholar]

| 1. | Minamata disease is a pollution-triggered disease which was first officially confirmed on 1 May, 1956. Methyl mercury contained in the waste water discharged from the Chisso Minamata factory was consumed by fish and shellfish in Minamata Bay, which were then consumed by humans, and the consumption of mercury-contaminated fish and shellfish triggered damage to their central nervous systems. Common symptoms included sensory impairment of the extremities of all four limbs, lack of bodily control, constriction of the visual field, and hearing disorders triggered by damage to the central nervous system. While the degree of severity varied among patients, those with the fulminant form (gekishōgata) of this disease developed symptoms very rapidly and often met quick physical deterioration and abrupt death. |

| 2. | (Kuwabara 1989, pp. 38–40). My translation. |

| 3. | This documentary was produced for Nihon TV’s program “Non-fiction Theater” (Non Fikushon Gekijō; 1962–1968), which is often considered as the pioneer of TV documentary on social issues. Film director Ōshima Nagisa’s Forgotten Imperial Army (Wasurerareta Kōgun; aired on 16 August 1963) is arguably the most known documentary it produced. |

| 4. | (Tsuchimoto 1976, p. 93). My translation. This article was first published in the 31 January, 1975, issue of Tōkyō Shimbun. |

| 5. | (Tsuchimoto 2005, p. 89). My translation. |

| 6. | (Tsuchimoto 1974, p. 15). My translation. This article was first published in the November, 1970, issue of Shin Nihon Bungaku. |

| 7. | (Tsuchimoto 1974, p. 115). My translation. This article was first published in the June, 1972, issue of Tenbō. |

| 8. | Ibid., p. 117. |

| 9. | Ibid., p. 136. |

| 10. | (Tsuchimoto 1988, p. 47). My translation. |

| 11. | Ibid., p. 48. |

| 12. | In 1969, the major Minamata disease support group, named the Mutual Aid Association for the Family of Minamata Disease Patients (Minamatabyō Kanja Katei Gojokai), was divided into the arbitration group (Ichininha) and the trial group (Soshōha) depending on their stance toward the Japanese government’s response to the plea for compensation. The former largely avoided media exposure, while the latter, which brought the company Chisso and the government to the court, actively engaged with the media to appeal their dire situations to the larger public and allowed photographers and filmmakers to capture them both at home and at street demonstrations. I assume the main reason for this sequence’s deletion from the wider circulated version is the position of Kumiko’s father as the arbitration group’s leader and Tsuchimoto’s connection with the trial group. In addition, Kumiko’s photographs taken by Kuwabara Shisei were often used at demonstrations without the permission of Kuwabara and Kumiko’s family, which Kumiko’s family was not content with. |

| 13. | Yunoko Rehabilitation Center opened in March 1965 as the region’s first rehabilitation facility, and all the Minamata disease patients at the municipal hospital’s Minamata disease ward were transferred to this center. |

| 14. | (Tsuchimoto 1974), pp. 13, 15 |

| 15. | Ibid., p. 17. |

| 16. | Ibid., p. 16. |

| 17. | As the encapsulation of their three-year stay in Minamata, they published the photobook, Minamata, first in the US in 1975 and later in Japan in 1980. As a result of the discussion with Kamimura Tomoko’s parents in 1999, Aileen Smith, who holds the copyrights to Smith’s Minamata photographs, decided to withhold this photograph from further exhibition and distribution. I discussed this issue extensively in Chapter 1 of my dissertation (Inoue 2018). |

| 18. | (Tsuchimoto and Ishizaka 2008, p. 143). My translation. |

| 19. | (Ōshima 1978, p. 74). My translation. |

| 20. | (Tsuchimoto 1974) Emphasis is mine, pp. 14–15. |

| 21. | (Ishimure 2008) My translation, pp. 274–75. |

| 22. | Due to the difficulty of proper care and the lack of equipment, most severely ill and congenital patients were sent to hospitals, which became their final home. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).