Abstract

To date, most work on computers in art has focused on the Algorists (1960s–) and on later cyber arts (1990s–). The use of microcomputers is an underexplored area, with the 1980s constituting a particular gap in the knowledge. This article considers the case of Polish-Australian artist, Stan Ostoja-Kotkowski (b. 1922, d. 1994), who after early exposure to computers at the Bell Labs (1967), returned to microcomputers late in his life. He was not a programmer yet used micros in his practice from the early 1980s, first a BBC in his BP Christmas Star commission, and later a 32-bit Archimedes. This he used from 1989 until his death to produce still images with a fractal generator and the ‘paintbox’ program, “Photodesk”. Drawing on archival research and interviews, we focus on three examples of how Ostoja deployed his micro, highlighting the convergence of art, maths, electronics, and a ‘hands-on’ tinkering ethic in his practice. We argue that when considering the history of creative microcomputing, it is imperative to go beyond the field of art itself. In this case, electronics and the hobbyist computing scenes provide crucial contexts.

Keywords:

micro-computers; computer graphics; landscape; photography; hybrid arts; laser art; Mandelbrot; electronics; Australia; Poland 1. Introduction

If the Algorists were the first generation of artists working with computers, then artists working with microcomputers would be the second, with a third generation associated with the era of multimedia and cyber-arts, from the early 1990s. To date, most work on computers in art has focused on the first generation and their use of mainframe and mini computers (Brown et al. 2008; Beddard and Dodds 2009) and on later cyber arts (Zurbrugg 1994). In Australia, Steven Jones has charted the period up to 1975 (Jones 2011), and Darren Tofts post 1992 (Tofts 2005). The use of microcomputers is an underexplored area, with the 1980s constituting a particular gap in the knowledge.

The second generation of artists using microcomputers was relatively short in duration, running from the late 1970s and early 1980s through to the early 1990s, prior to the (third generation) era of digital multimedia, with its accompanying rhetoric of convergence around virtual reality, telepresence, interactivity, and the widespread use of readymade, off the shelf software (e.g., CAD, Macromedia Director, etc.). Microcomputers were so named after the microprocessors that powered them, as well as to differentiate them from their larger ‘mini’ computer siblings. Though the 1980s saw both a low and a high-end market in microcomputers, both were considerably less expensive than mini computers. The 1980s also marked the moment when computing became ‘personal’, at least in popular parlance,1 with the idea of a ‘home computer’ gaining traction as something that belonged in households during the decade (Swalwell 2012).

This article considers the case of Polish-Australian artist, Stan Ostoja-Kotkowski (b. 1922, d. 1994), who after early exposure to computers at the Bell Labs (1967), returned to micro-computers later in his life. He was not a programmer yet used micros in his practice from the early 1980s, first an 8-bit BBC Micro for the BP Christmas Star commission, and later a 32-bit Acorn Archimedes computer (see Figure 1). This he used from 1989 until his death to produce still images with a fractal generator and the ‘paintbox’ program, “Photodesk” (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6).2

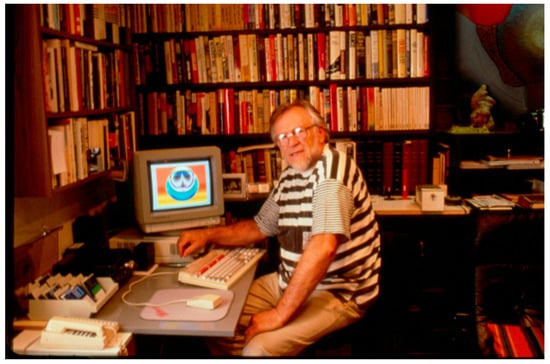

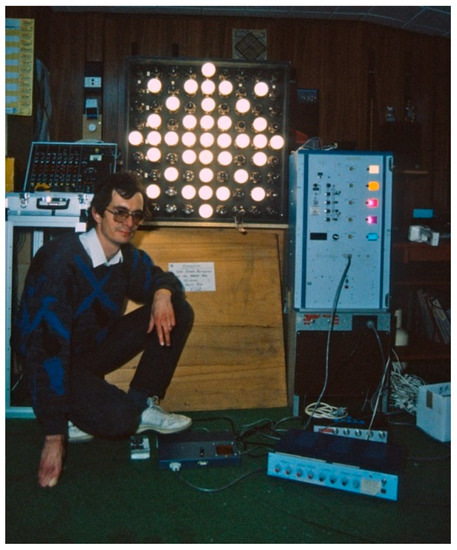

Figure 1.

Ostoja in his studio with his Acorn Archimedes microcomputer, date unknown. Published with permission. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia. SLSA: PRG919/22/42.

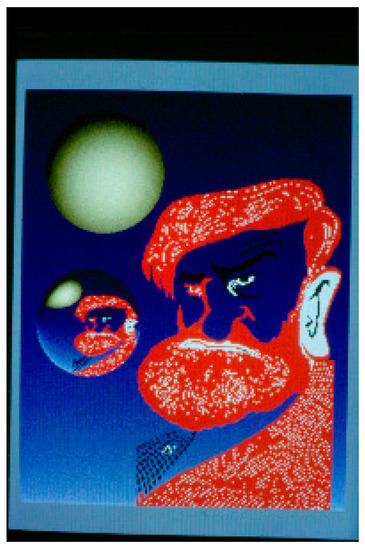

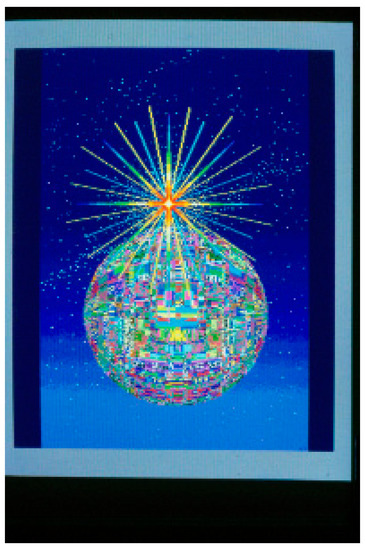

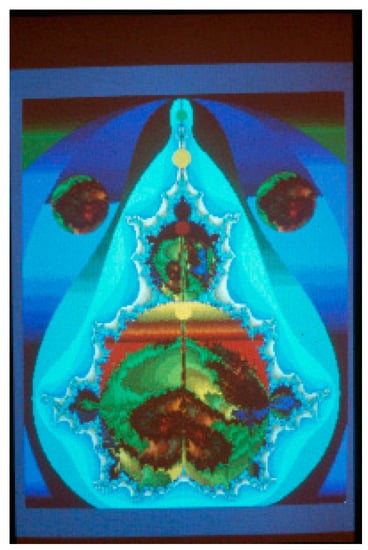

Figure 2.

Unnamed image from Ostoja’s slide collection, possibly a self-portrait. Published with permission. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia. SLSA: PRG 919/22/394.

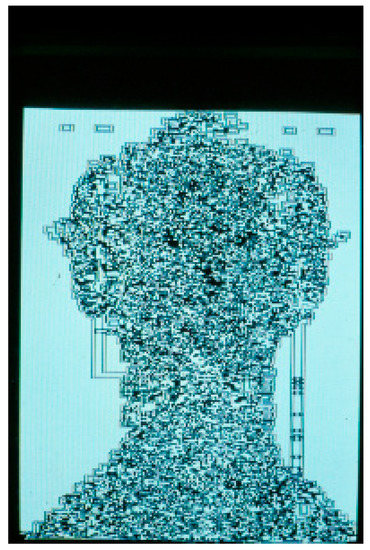

Figure 3.

Unnamed image from Ostoja’s slide collection. Published with permission. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia. SLSA: PRG919/22/404.

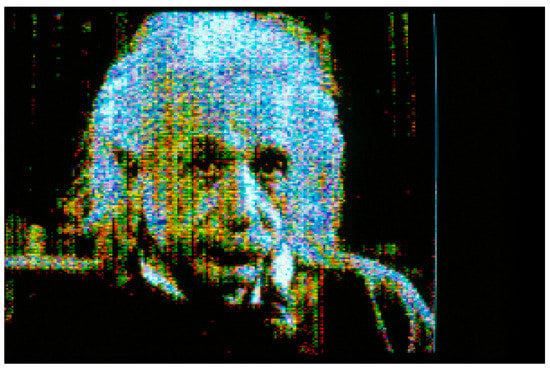

Figure 4.

Unnamed image from Ostoja’s slide collection. Published with permission. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia. SLSA: PRG919/22/744.

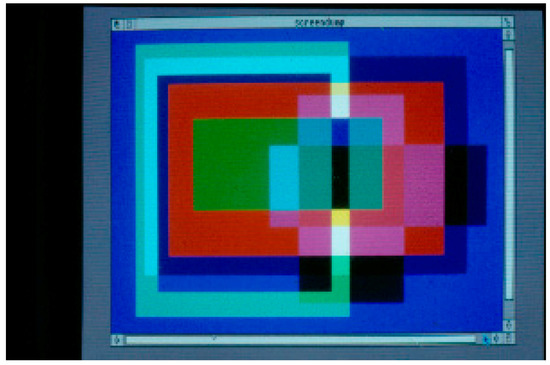

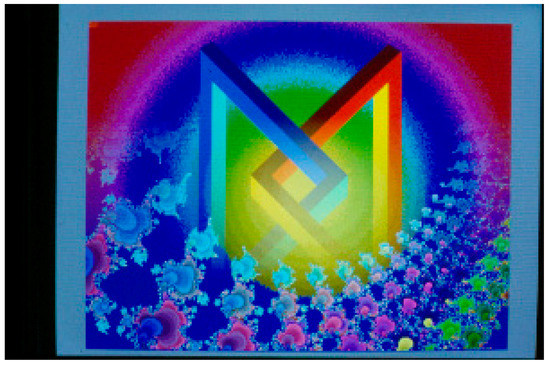

Figure 5.

Unnamed image from Ostoja’s slide collection. It seems to correspond to the disk label “Homage to Albers” (seen in a later Figure). Published with permission. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia. SLSA: PRG919/22/69.

Figure 6.

Unnamed image from Ostoja’s slide collection. Figure 6 appeared in black and white on the front of the Adelaide Beebnet computer user group printed newsletter. Published with permission. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia. SLSA: PRG919/22/464.

Focusing on three examples of how Ostoja deployed his micro—the BP Christmas star commissions, his Mandelbrot works, and his landscapes with CGI—we argue that his work instances a convergence of art, maths, electronics, and a ‘hands-on’ tinkering ethic, developed over many years of experimental practice across such diverse media as theatre, laser art (an example of which is seen in Figure 7), sound and image shows, electronics, and television. This is not a Jenkins-like convergence of technology (Jenkins 2006), but there are continuities between Ostoja’s early and later art practice in that he often seems to have combined a range of influences across his lifetime.

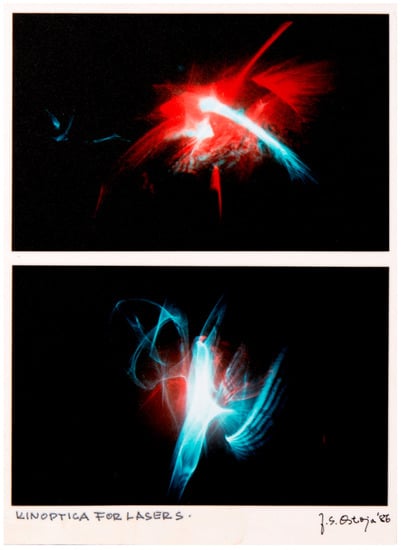

Figure 7.

Józef Stanisław Ostoja-Kotkowski. Kinoptica for lasers 1986. Colour photographs. Gift of the Estate of Edward Stirling Booth. Flinders University Art Museum Collection 4241.223. Photograph by Flinders University. © the Estate of the artist. Published with permission.

2. Context and Background

The context for this study is an ongoing project looking into Australian ‘creative micro-computing’ between 1976 and 1992. This follows on from Swalwell’s prior research into the everyday uses that were made of micro-computers when they first became accessible to laypeople in the late 1970s and 1980s in Australia and New Zealand (Stuckey et al. 2013, 2015; Melanie Swalwell 2008; Melanie Swalwell et al. 2017). Garda has previously researched the reception of 8-bit microcomputers by computer game players and other enthusiasts in 1980s Poland (Garda forthcoming). The wider project attempts to overcome a siloed approach by any framing that might consider, say, just artists’ use of micros. The research on Ostoja is a particularly good example of this approach—whereby the use and products of use are considered in an expanded context, taking in both hobbyist engagement and fine art scenes, for example—because of his habit of seeking out collaborators with specialist expertise, developed over many years of experimental practice across diverse media. Ostoja seems to have collaborated with assistants quite extensively, of whom we have been able to interview two. Though fieldwork is ongoing, preliminary findings from the larger study of creative micro-computing suggest—somewhat surprisingly—that fewer artists in the 1976–1992 period programmed than did everyday home users. Though he was very hands-on with technology, Ostoja exemplifies the tendency of those artists who used computers in their art practice to use them without necessarily learning to program. This set them apart from the earlier generation of artists, known as the Algorists, for whom programming was an essential skill.

3. Brief Survey of Ostoja’s Work

Originally trained as a painter, Ostoja spent much of his life working with various new technologies. He was an innovator in laser art, beginning in 1968, and was the only Australian to be working in this field at the time. He published an article in a Leonardo special issue on the topic (Ostoja-Kotkowski 1975) and is probably best known for his laser art works (Figure 7 shows several images of his laser art). Ostoja’s influences were many—Abstract Expressionism, Bauhaus, Op Art, and more besides. He worked the art/technology nexus for decades prior to using micro-computers. In what looks like an unpublished speech found in the Warsaw archive (dated Sunday 14 June 1992), John Stringer, Senior Curator at the Art Gallery of Western Australian, calls Ostoja “the old master of multi-media” (Stringer 1992). As Macdonald puts it in his doctoral thesis, Ostoja was never only doing one thing (Macdonald 2005). He was an innovator, leading a convergence of electronic media with theatre, dance, experimental film, and light shows from as early as the 1960s (Edwards 2009).

In some ways, Ostoja was an outlier, a paradoxical figure: a Polish man living in Australia, who at times encountered hostility to his art.3 Yet he was one of the most successful public artists in this era in Australia, personally recognised in the Australia Day Honors List in 1992 (The Advertiser 1992), and certainly amongst the best known Australian artists we have come across who were using computers to make art at the time (though he wasn’t necessarily widely known for this). One of his murals hung in Adelaide airport, a postage stamp was made featuring his laser art in 1985, and there was a feature on his use of computers in The Australian magazine (McKenzie 1989).

On the significance and reception of Ostoja’s work, Edwards writes:

He was a catalyst for a more adventurous style of theatre in Australia and he brought a modern European approach to filmmaking. His op art introduced many Australians to this genre …Reviews of his films, theatre sets and kinetic productions were not always positive, mainly because Ostoja was always pushing audiences to the edge, which sometimes made them uncomfortable. He was accused of commercialism, as he appealed to a broader audience than the art gallery clientele. He was an artist who managed to live from his art, but it was his art that was important to him.(Edwards 2009, p. 32)

4. Ostoja’s Micro-Computer Works

In this article, we focus on the three examples we found of how Ostoja deployed his microcomputer: (1) the Christmas star commissions for BP on St Kilda Rd in Melbourne; (2) his Mandelbrot works, and (3) his landscapes with CGI. Our method has involved archival research and analysis, combined with interviewing two of Ostoja’s collaborators, who have in turn shared archival materials from their personal collections with us. Ostoja’s archive is substantial and very rich, consisting of personal papers, artworks, press coverage, and many different media formats. He appears to have been a prolific letter writer, and it was his practice to keep copies of his correspondence. The archive is held jointly by the State Library of South Australia, and the University of Melbourne’s Ballieu Library, and is recognised as internationally significant. In 2008 it was accepted into the UNESCO Australian Memory of the World register (UNESCO 2008). We also consulted materials held in the Flinders University Art Museum, and the National Museum in Warsaw.

Our overarching argument is that in each of the three cases we consider from Ostoja’s art practice, there is a convergence of art often with maths, electronics, and what we term a ‘hands-on’ tinkering ethic. This tinkering ethic was a mode of practice with which Ostoja was thoroughly familiar, having spent many years experimenting in such diverse media as theatre, laser art, sound and image shows, electronics, and television. On televisual experimentation, Robert Scarfe reported Ostoja saying in interview:

We see many similarities between Ostoja’s earlier and later practice, where he was reliant on others to a significant degree in the production of his artworks. In that sense, the microcomputer works represented a continuation of collaborative practice rather than a departure, and this reliance on others is particularly seen in Russell Dahms’ building of custom electronics for the BP Star commission, as well as other projects.Of course with colour television the experiments could go much further. I spent some time [in 1962] at the Marconi Electronics Research lab in Chelmsford, England, and they have some beautiful equipment there to project colour television onto a screen. And when I got there first they showed me how beautifully they could project these images. They made up the image from something pre-set, sent it through the system and projected it onto a screen; and there were beautiful images on the screen in colour. So I said, “Well can we now start to do some experimenting with this,” and they said “What do you want?” “First of all I want to get the thing out of register”—“What do you mean, out of register’—we just spent two days getting the alignment on these”. But they co-operated, and we started experimenting, and by the end of the day I just didn’t have to do anymore. The ideas just kept on pouring, one after the other. What could we do? How could one do it?—let’s separate the reds from the blues, let’s shift them, let’s curve them. By the end I could just press a button and get a beautiful image there. This was by trying to explore, by trying to do things which are not the normal things; to get off the main way and try to experiment. That’s where you’re going back to experimentation and trying to discover things.I remember the first time we tried the experiments here at T.V. studios in Australia. The producer threw his hands [up] in despair—“What are you trying to do, you’ve lost all the half-tones”. I said, “Marvellous, good”. Now today to lose half-tones is practically a normal thing in television, but it took 5–6 years to convince the director you could get a beautiful picture without the half-tones.(Scarfe 1971)

4.1. Christmas Stars on St Kilda Rd

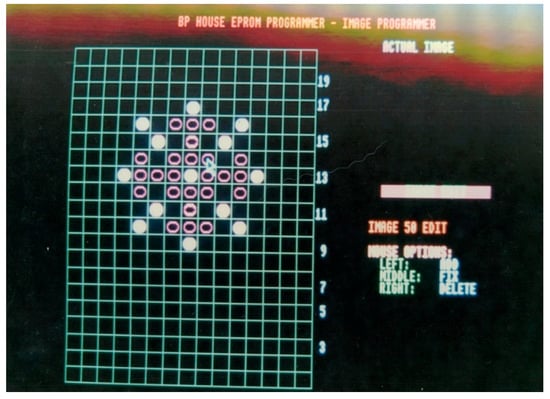

Ostoja received many commissions, including for the creation of a large electronic Christmas star to be installed on the BP building on St Kilda Road, in Melbourne.4 The BP Star commission was first done by Ostoja in 1971 (in which the lights responded to sound (Sunday Mail 1971)), but it was not until the 1980s, we think,5 that the stars were programmed using a computer. (Figure 8 shows a photograph of a star installed (we don’t know if it was one of Ostoja’s) on the BP Tower, taken by his friend, photographer Mark Strizic). These star installations instance a convergence of electronics and computing. Ostoja’s collaborator for these pieces, Russell Dahms (shown with a smaller prototype star in Figure 9), recalls writing a small program so that Ostoja could map out the patterns that he wanted for the light sequences. A shot of the screen showing the computer program Dahms developed is seen in Figure 10. Dahms recalls:

I wrote a program on the computer so Ostoja could program the images for the side of BP House in Melbourne for the Christmas display. Basically it was in a BASIC language on the BBC Micro. And I wrote a program so there was a grid on the screen, and he would manually—I think it was with a mouse back then, a very primitive mouse—go and turn on which lights he wanted to be on in that particular frame. He would then save it, he would then increment to the next frame, and then he would turn on and off the next light sequence he wanted for the exhibition. And then of course he could play it back and he would probably spend two weeks doing this, because it was like a nine by nine matrix of these lights. And when he’d finished with it I somehow got it out of the BBC Micro, probably on a floppy disc, and then I took it wherever I worked [where] there was an EPROM programmer. So I transferred the raw data into an EPROM and I would just clock that out with an opto-coupler multiplex circuit, and it would actually drive the light banks through the triacs. Because in Melbourne … someone else had made this big three-phase electrical controller which controlled these light panels on the side of BP House … And each one of them was kilowatts, and so it had this big three-phase control system. But I just outputted the information from the EPROM to this triacs which controlled the lights…and it would step through the images.(private communication)

Figure 8.

Photograph of a star installed on BP House, St Kilda Rd, Melbourne. We do not know whether it is one of Ostoja’s stars, or not. Mark Strizic, 1976, photograph of the Christmas Star installed on BP House, Melbourne. © the Estate of Mark Strizic. Published with permission. Image courtesy: Pictures Collection, State Library Victoria.

Figure 9.

Russell Dahms with the Christmas star prototype in Ostoja’s studio. Published with permission. Image courtesy Russell Dahms.

Figure 10.

Screenshot of the program Dahms developed to allow Ostoja to “program” the Christmas star. Published with permission. Image courtesy Russell Dahms.

In another photograph not reproduced here, Dahms is seen posing with Ostoja and the prototype star, with the micro-computer in the foreground on a trolley (refer n. 5).

Dahms further recalls that “We [he and John Fleming (partner) and friends] were always the source of information regarding computers and electronics.” He continued:

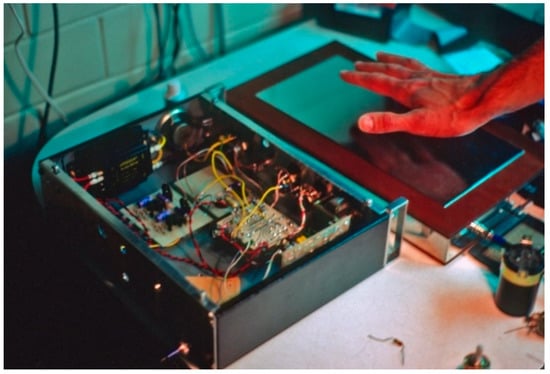

Dahms made it possible for Ostoja to ‘program’ this BP Christmas star, without doing any actual programming. Sharing archival images with us, Dahms has indicated to us that Ostoja’s theremins were also programmed on the Archimedes (see Figure 11 and Figure 12) (private communication, 18/7/16). Interestingly, these were artworks or instruments that were created with the micro, but which did not require the micro, and so looked more like electronics than computer art. As Dahms says: “A lot of it was dedicated electronics to produce a solution. It may have involved a computer to program it or to design it, but invariably it was mapped out into a standalone system that could function without the computer.”Ostoja would ring up and ask how to use some software feature on the program, and sometimes we hadn’t even seen the program. Or he couldn’t get his computer to start, or this sort of stuff … And I had a group of friends as well … and they were into computers and they had the BBC micros. They went to that club you mentioned, the computer club—Beebnet … They would go to those meetings and describe all the advances in computers. And to some extent I relied on them a little bit on the computer side of things ….(private communication)

Figure 11.

Russell Dahms with Ostoja’s theremin. Published with permission. Image courtesy Russell Dahms.

Figure 12.

Internal view of Ostoja’s theremin showing electronics. Published with permission. Image courtesy Russell Dahms.

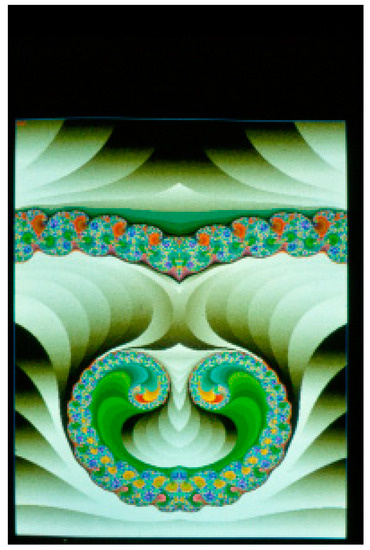

4.2. Mandelbrot Works

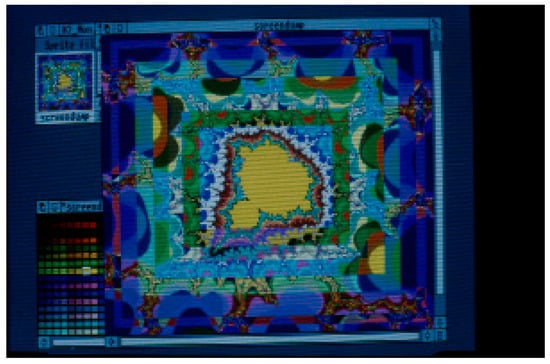

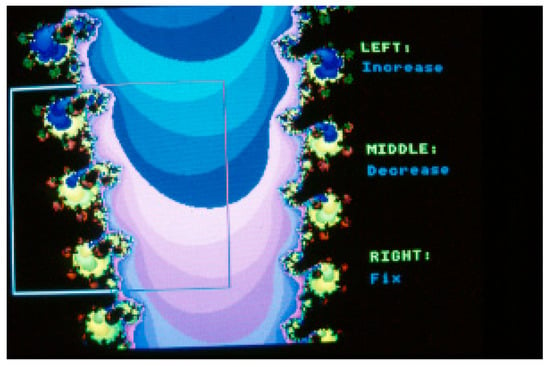

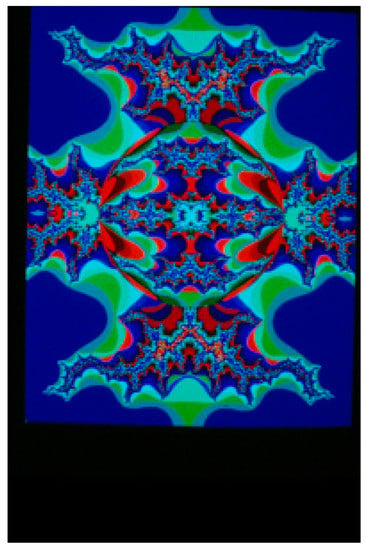

The Mandelbrot series is the first of Ostoja’s two still images series that we consider, that were created on the 32-bit Acorn Archimedes computer (see Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21 and Figure 22). In several news articles, it’s written that he “spent six months mastering difficult computer programs and now uses that technology and a mathematical formula, known as Mandlebrot [sic], to produce stunning images which he transfers to slides and sets to music” (The Advertiser 1992, 1994).

Figure 13.

A screenshot, apparently derived from the Mandelbrot set, manipulated in a paintbox program, and captured on slide film by Ostoja. Published with permission. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia. SLSA: PRG 919/21/381.

Figure 14.

A screenshot, apparently derived from the Mandelbrot set, manipulated in a paintbox program, and captured on slide film by Ostoja. Published with permission. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia. SLSA: PRG919/21/398.

Figure 15.

A screenshot which became the artwork “Id”, apparently derived from the Mandelbrot set, manipulated in a paintbox program, and captured on slide film. Published with permission. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia. SLSA: PRG 919/22/756.

Figure 16.

A screenshot, apparently derived from the Mandelbrot set, manipulated in a paintbox program, and captured on slide film by Ostoja. Published with permission. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia. SLSA: PRG919/22/810.

Figure 17.

A screenshot, apparently derived from the Mandelbrot set, manipulated in a paintbox program, and captured on slide film by Ostoja. Published with permission. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia. SLSA: PRG919/22/866.

Figure 18.

A screenshot, apparently derived from the Mandelbrot set, manipulated in a paintbox program, and captured on slide film by Ostoja. Published with permission. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia. SLSA: PRG/919/22/1271.

Figure 19.

A screenshot, apparently derived from the Mandelbrot set, manipulated in a paintbox program, and captured on slide film by Ostoja. Published with permission. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia. SLSA: PRG919/22/1208.

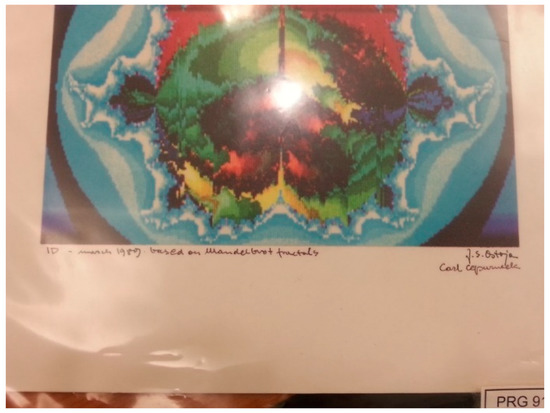

Figure 20.

“Id”, co-signed by Ostoja and Cepurneek, and dated March 1989. SLSA: PRG919/21/835. Image courtesy Melanie Swalwell. Published with permission of SLSA.

Figure 21.

Close-up of “Id”, co-signed by Ostoja and Cepurneek, and dated March 1989. SLSA: PRG919/21/835. Image courtesy Melanie Swalwell. Published with permission of SLSA.

Figure 22.

One of Ostoja’s landscapes with CGI. Published with permission. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia. SLSA: PRG 919/21/64.

However, as Heather McKenzie noted, “Ostoja is no computer buff” (McKenzie 1989, p. 58). She quoted him as saying of the Mandelbrot:

It offers the artist not only a range of colours, but a range of forms and shapes. When using the Mandelbrot, the graphic image on the screen represents the beauty of the mathematical formula; the artist recognises and responds to this beauty”.(McKenzie 1992, pp. 63–64)

While Ostoja had previously explored using mathematics to create art, this seems to have been limited to visual influences. Since at least the 1970s, he was interested in polyhedron stars and graph theory, for instance, a reproduction from Kircher’s Ars Magna Sciendi … (1669) was found in Ostoja’s archives (SLSA PRG 919/22/738).

Many artists were interested in fractals in the 1980s. Books such as The Beauty of Fractals: Images of complex dynamical systems (Peitgen and Richter 1986) were widely available, and exhibitions of fractal images toured. We have found a reference suggesting that the “Patterns of Chaos” exhibition—comprising 76 3D images which had been touring the world for eight years—was shown at the University of Adelaide, around 1990. It is conceivable that Ostoja would have seen either the books, or the exhibition, or both. And though he might not have understood the maths, Carl Cepurneek, his sometime collaborator with a PhD in biomedical science, did. Cepurneek is mentioned in several publications and described as a “computer specialist” (McKenzie 1992, p. 64). Ostoja often credited him. Indeed, we found a version of “Id”—probably the best known of Ostoja’s Mandelbrot works—that is co-signed by Ostoja and Cepurneek (see Figure 20 and Figure 21), dated March 1989. It was reported that ‘Id’ took Ostoja two hours to produce (McKenzie 1989, p. 64).

Like Dahms’ friends, Cepurneek had contact with the user group and hobbyist computing scene and was transmitting some of this knowledge to Ostoja. He suspects he found Ostoja a fractal generator, possibly from a user group. Creating “Id” would have involved using at least two different programs, Cepurneek thinks: the Mandelbrot generator, and a basic paint program, “PhotoDesk”, which was a little like early Photoshop. Using these software tools, Ostoja manipulated the Mandelbrot images, often combining them with geometrical shapes, like interlocking triangles (Figure 16), or wrapping them onto spheres. Cepurneek related that he would also show Ostoja things he’d just learned were possible to do on the Archimedes and share interesting parts of the Mandelbrot he’d discovered with him. Cepurneek talked about their collaboration as being like the kind of sharing that went on at computer user group meetings, where someone would figure out something new and go okay, “now everybody can use that new little bit to further the direction they happen to be going in” (private communication).

It is possible to see scanlines on the smaller printed versions of ‘Id’. Cepurneek actually counted them as he explained to us that the Archimedes screen resolution was 256 × 640. We found a photograph of Ostoja with a larger version of “Id”, in the scrapbooks in the National Museum in Warsaw. Based on correspondence we found in the SLSA archive, we think this was probably printed using Metromedia MMT, which was a then new computer/robot-executed acrylic drum painting technology for outdoor advertising. McKenzie corroborates this, noting that a 2 m × 1.6 m ‘painting’ of “Id” was created using the MMT technique, which involved “computer scanning” with superior resolution and quality (McKenzie 1989, p. 64). Ostoja was pleased with the results, though he felt it still needed re-touching to be of the quality expected for fine art.6

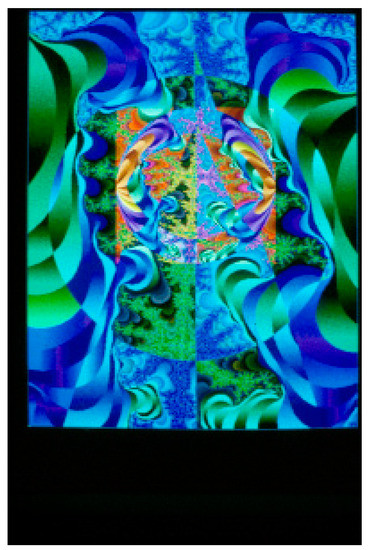

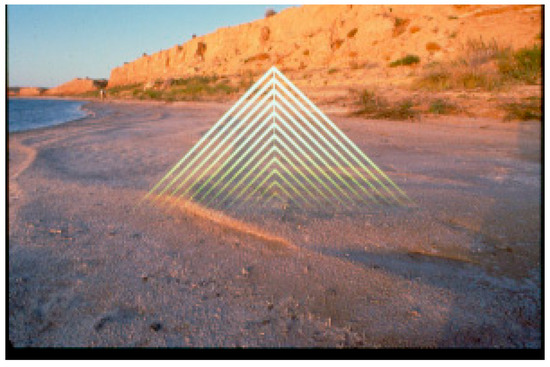

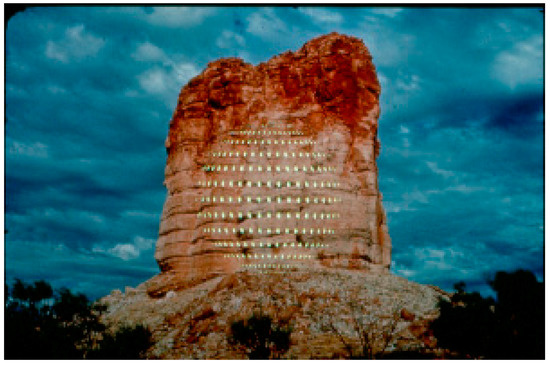

4.3. Landscapes with CGI

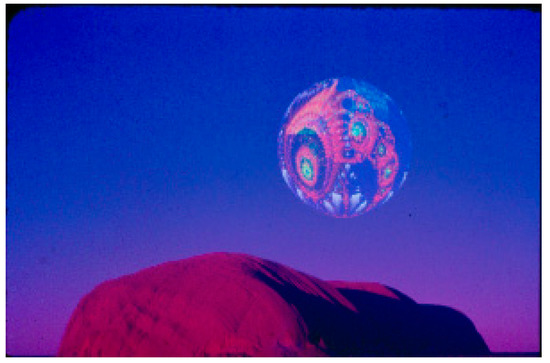

The landscapes with CGI are the latest works we are aware of that were made with the Archimedes. These combined digital graphics with analogue photographs, often of iconic Australian landscapes including Uluru, and the Devil’s Marbles (Figure 22, Figure 23, Figure 24, Figure 25, Figure 26, Figure 27 and Figure 28 show samples from this series). Our research indicates that these images—which variously bear slide dates of late 1992 and 1993—were not exhibited until 1994, the year of Ostoja’s death, at the Adelaide Festival.7

Figure 23.

One of Ostoja’s landscapes with CGI. Published with permission. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia. SLSA: PRG919/21/69.

Figure 24.

One of Ostoja’s landscapes with CGI. Published with permission. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia. SLSA: PRG919/21/159.

Figure 25.

One of Ostoja’s landscapes with CGI, featuring Mandelbrot imagery mapped onto a sphere. The landscape is the very recognisable Uluru. Published with permission. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia., PRG919/21/163.

Figure 26.

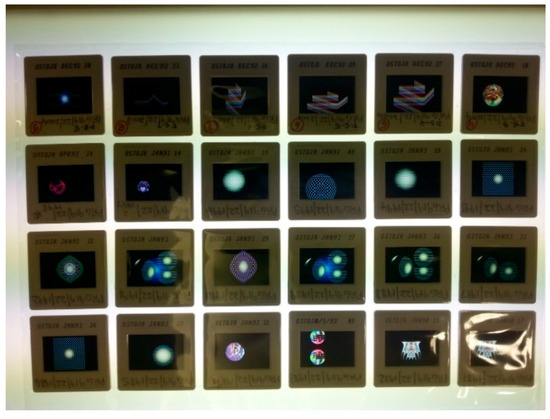

Slides of the computer-generated imagery, dated January 1993. We think Ostoja shot these directly off the screen using 35 mm slide film. SLSA: PRG919/22/1981-2004. Image courtesy Maria Garda. Published with permission of SLSA.

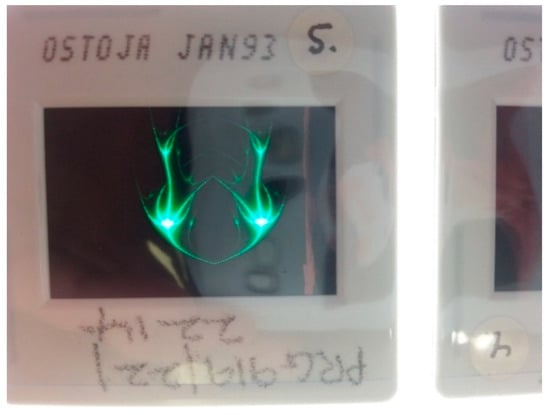

Figure 27.

Close-up of computer-generated imagery that would be combined with the landscape in Figure 29. SLSA: PRG919/22/1981-2004. Image courtesy Maria Garda. Published with permission of SLSA.

Figure 28.

Composited landscape with CGI slide, dated February 1993. SLSA: PRG919/22/2140. Image courtesy Maria Garda. Published with permission of SLSA.

In a post-Photoshop world, the composited images might not seem that remarkable. However, getting work off the screen was an issue many artists using micro-computers grappled with at this time. In terms of their creation, these works are interesting digital-analogue hybrids. Ostoja had a camera mount on his desk (the small white box is visible behind him and to the right in Figure 1) and according to Dahms, he would turn the computer monitor so that it would be square on to the mount. Using 35 mm slide film, he photographed the computer graphics as they were displayed on the screen. Samples of some of his CGI slides are seen in Figure 26 and Figure 27.

We are not sure how Ostoja made the composited images, an example of which is seen in slide form in Figure 28. Like many artists working with computers in the micro era, he was concerned with the quality of output from the computer. In 1992, McKenzie wrote:

For the future, Ostoja is working to devise a method which reproduces computer art in its original clarity and colour, as it appears on the screen. At present, he feels that the brilliance of the screen images is lost when transferred to film. He feels optimistic that research will find a solution and believes that liquid-crystal technology may well provide an answer, allowing an image to be transferred to a liquid-crystal display plate or board.(McKenzie 1992)

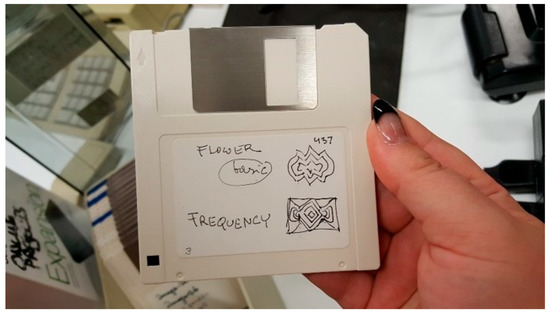

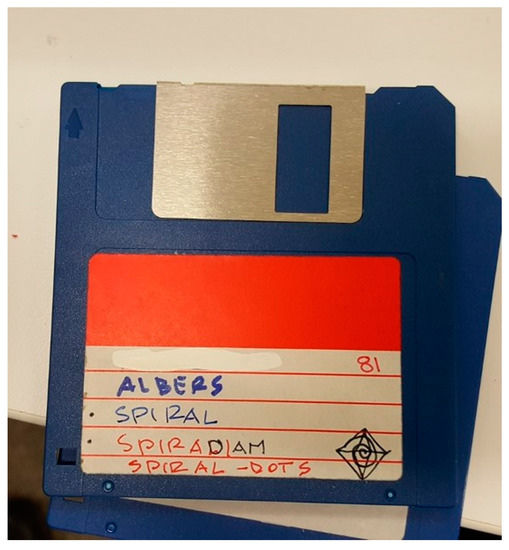

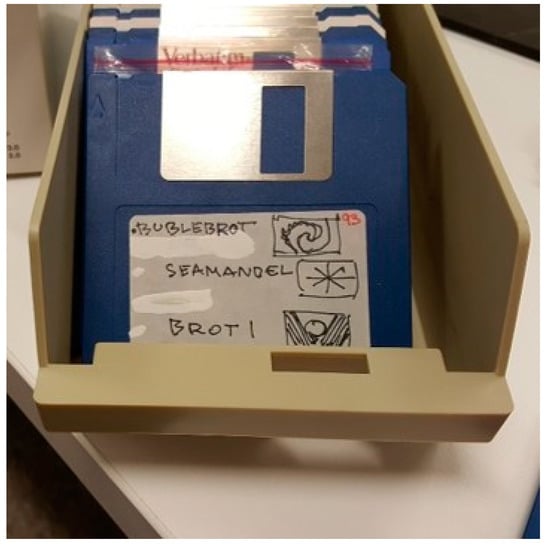

We initially thought that Ostoja must have projected the CGI slide images simultaneously with slides of the landscapes and re-photographed these on 35 mm slide film. He often used multiple slide projectors at installation events as seen in Figure 29, so this was a reasonable guess (there are many such photographs of him with multiple slide projectors). There were no scanlines visible to us in the landscape elements of these works (unlike, say in Figure 4, the Einstein image), suggesting the landscapes were analogue images. Furthermore, in the course of his proposal to Tony Salvis of Barton computers in Collingwood (to whom Ostoja proposed trading some of his artworks for a computer memory upgrade, from 1 to 4 MB), Ostoja suggested that the images might be exhibited this way, though he clearly recognised that this was not an ideal solution. However, projection on the one screen would not explain how the black backgrounds of the CGI images were masked. We assume some kind of scanner must have been used, though this is speculation at the moment. Currently Ostoja’s slides are accessible to researchers, but not his disks, so our analysis has been conducted without the benefit of access to the digital files. It is hoped that further clues as to the creation of these images might be found once Ostoja’s floppy disks are imaged and made accessible to researchers (Figure 30, Figure 31 and Figure 32 show some of his floppy disks, from the State Library of South Australia archive). Access to the disks may also clarify which computer system the Christmas star was programmed on.

Figure 29.

Mark Strizic. The artist demonstrating equipment for “Sound and Image” kinetic lasers productions 1960s. Black and white photograph. Gift of the Estate of Edward Stirling Booth. Flinders University Art Museum Collection, Papers of Ostoja-Kotkowski, Folder 20. © the Estate of the artist. Published with permission. This is one of many photographs we found showing Ostoja with his apparatus. Note the multiple slide projectors in the background.

Figure 30.

One of Ostoja’s floppy disks, showing his descriptive use of line drawings to label disks, and his reference to the Mandelbrot-derived images using everyday referents which they resembled in some way (“flower”, “frequency”). SLSA disks taken in Flinders Computer Archaeology Lab. Image courtesy Melanie Swalwell. Published with permission of SLSA.

Figure 31.

One of Ostoja’s floppy disks, showing his descriptive use of line drawings to label disks, and use of white-out on disk labels. SLSA disks taken in Flinders Computer Archaeology Lab. Image courtesy Melanie Swalwell. Published with permission of SLSA.

Figure 32.

One of Ostoja’s floppy disks, clearly showing neologisms (e.g., “Seamandel”, “Bubelbrot”), descriptive use of line drawings, and use of white-out on disk labels. SLSA disks taken in Flinders Computer Archaeology Lab. Image courtesy Melanie Swalwell. Published with permission of SLSA.

5. Concluding Thoughts

By way of conclusion, we offer three sets of reflections, drawing from and contextualising this case study. First, we note that Ostoja’s uses of the micro diverged in several important ways from those of his contemporaries, both Australian and international artists. Internationally, not very many artists seem to have used low-end consumer micro-computers as Ostoja did. An as yet unpublished but related survey of computer art catalogues held in the Patric Prince collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum, reveals that of those artists who were making ‘computer art’ from the late 1970s to the early 1990s, a considerable proportion were working with higher end systems, e.g., Qantel Paintboxes, Silicon Graphics workstations, or machines in commercial or military or university premises (e.g., David Em used the machines at the Jet Propulsion Labs). In the Australian context, Ostoja seems to have been working in quite a different paradigm and also exhibiting different concerns to his contemporaries. Computer art theorist, Grant D. Taylor, writes that many artists of the 1980s understood their practice in terms of photographic theory, and the continental philosophies that attached to postmodernism, but that this was an ill-fitting paradigm for much computer art, which shared allegiances with science and technology and the modernist paradigm (Taylor 2014, p. 23). The potential to make art using microcomputers was embraced by younger Australian artists in the 1980s, many of whom came from either a visual arts or musical background. Only a few were programming, interfacing electronics with computers, or using code to generate imagery, however, with the majority of the visual artists, at least, tending toward video art. Apart from offering a convenient output for computer work, video artists were—per Taylor’s thesis—working with a lexicon of photographic and moving image aesthetics.8 Though Ostoja was no stranger to multimedia shows, his work with the computer produced a visual art that was about still rather than moving images. Indeed, at a time when local artists were eschewing the landscape tradition—curator Peter Callas suggests post-war Australians may be more interested in, and comfortable with mediascapes (Callas 1994, p. 5)—Ostoja was captivated by the quality of Australian light and remade iconic landscapes, juxtaposing natural elements with CGI, inventing a hybrid (digital-analogue) aesthetic. His practice produced a distinct aesthetic from others working with computers at the time, who were embracing grainy, pixelated images, utilising the computer as an animation tool. More than 20 years later, Ostoja’s defamiliarised landscapes remain remarkably fresh: they are no longer just Uluru or the Devil’s Marbles. Denaturalised, they almost seem to make visible an unseen energy or presence.

Second, Ostoja’s use of micros suggests that there is a need for an expansion of the narrative on artists’ uses of microcomputers in the 1980s that goes beyond that of the “artist-programmer” and “user of off-the-shelf-software” continuum. In his “A little piece on Algorithmic Art” from 1987, Bill Kolomyjec offers a narrative on how artists came to computing and developed application software:

Ostoja’s practice complicates the scenario Kolomyjec outlines and offers a useful case for rethinking the narrative around the extent to which artists were able to experiment with micro-computers in the period. Often, the narrative seems to be that artists were either hamstrung by the software they had available, or by their limited coding abilities, and that these were factors that impeded experimentation. Ostoja is neither an artist-programmer nor just a user of off-the-shelf application software. He collaborates not just with programmers (Cepurneek, Dahms), but also with a technician with a deep expertise in electronics (Dahms), to undertake a range of artistic experiments that exceed the category of ‘software’ or ‘algorithm’. His extensive use of assistants was arguably a collaborative method that he was well used to from years of collaboration, working in labs, and befuddling technicians. He was heavily reliant on others to do the programming and circuitry, having no understanding nor grasp of either programming or electronics, and “no capability”, as Dahms put it. According to Dahms, Ostoja was always more interested in the outcome than in understanding how the electronics worked.9 Yet the Archimedes seems to have given him a remarkable degree of creative control. He could do much more on his own with the computer than with other equipment. Using Dahm’s program for the BP star, he could try different settings by himself; not to mention the countless hours he must have spent tinkering with the Mandelbrot images in editing programs. He once described the computer as the ‘artist’s apprentice’ (Harris 1989), and in a sense, for him, it was. As Edwards writes:In the beginning there was no application software. If a person wanted to be creative with a computer, i.e., be a computer artist, s/he had to either write algorithms or collaborate with someone who could. Application software often grew out of such collaborations or dialogs between artist/designers and engineer/scientists. People who knew how to write algorithms began to provide software for the less knowledgeable. Eventually, artist/designers acquired these skills for themselves.(Kolomyjec 1987, p. 3)

Ostoja’s practice calls for a rethinking of the assumption whereby programming competence is thought to equal greater capacity for experimentation. His collaborative method of working with the microcomputer and others with specialist skills presaged many of the art-science collaborations that are undertaken today (such as the Synapse program run by ANAT). Edwards actually calls Ostoja an “artist-scientist” (Edwards 2009, p. 27). Other artists at the time were mostly doing solo works, whereas he was seeking out knowledgeable others who could take his art somewhere he could not on his own.He was able to harness the knowledge of others when his inspiration was not matched by his technological knowledge, and by doing so, extended the freedom of the artists who were to follow, who found themselves no longer bound by convention and form.(Edwards 2009, p. 33)

Finally, the Ostoja case study demonstrates the great value of an expanded approach to what we call ‘creative micro-computing’. The imbrication of different creative computing scenes at this time—from art to hobbyist/computer tinkerer, to electronics, to professional science-maths knowledge—is well illustrated. It was through Dahms and his friends that Ostoja was connected to the BBC Computer User group. Meanwhile, as a postdoctoral biomedical research specialist, Cepurneek provided contacts to both the professional research sector and the Archimedes hobbyist computing scene.10 These connections and collaborations followed on from earlier ones Ostoja had enjoyed with many labs, industries, scientists and technicians (3M, Philips, Weapons Research, CSIRO), and universities (Budrewicz 1982, p. 19). There is also good evidence of him reaching out to commercial entities, such as computer companies (including Barton Computers in Collingwood and the Australian branch of Acorn), seeking their support for the further development of his computer graphics, and offering samples of his art as a showcase of what could be produced using their machines. In this, he was not alone: preliminary fieldwork indicates that many artists working with micros during the period were working in and proximate to industry as well as to art scenes (examples in Australia include Sally Pryor and Linda Dement). Others were connected to enthusiast culture. Yet such an expanded approach to computer art history has rarely if ever been undertaken.

The Ostoja case study supports our argument for an expanded microcomputer history, one that is able to attend to the crossovers between art, industry, and hobbyist pursuits. Rather than a media arts history that is only curious about what artists were doing, or a computer history that ignores the popular, it is important to attend to the overlaps and the nexus between different computing scenes. This is something we expect our future work to contribute to.

Author Contributions

Funding acquisition, M.S.; Investigation, M.S. and M.B.G.; Project administration, M.S.; Writing—original draft, M.S.; Writing—review & editing, M.S. and M.B.G.

Funding

This research was funded by the Australian Research Council, grant number FT130100391.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Flinders University which provided co-investment funding to support Garda’s postdoctoral position. We also thank the staff of the archives we consulted, particularly the State Library of South Australia and Flinders University Art Museum, for their assistance in preparing and permission to re-publish images.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Beddard, Honor, and Douglas Dodds. 2009. V&A Pattern: Digital Pioneers. London: V&A Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Paul, Charlie Gere, Nicholas Lambert, and Catherine Mason, eds. 2008. White Heat Cold Logic: British Computer Art 1960–1980. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Budrewicz, Olgierd. 1982. Wsrod Polskich Kangurow. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Interpress. [Google Scholar]

- Callas, Peter. 1994. An Eccentric Orbit: Video Art in Australia (Catalogue Essay). New York: American Federation of Arts, pp. 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Cancel, Luis R. 1987. Introduction. In The Second Emerging Expression Biennial: The Artist and the Computer. New York: The Bronx Museum of the Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, June. 2009. Explorer in Light. Bibliofile, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Garda, Maria B. Forthcoming. Microcomputers. In Alternative Media Usage During the Decline of the Polish People’s Republic. Edited by Piotr Sitarski, Maria B. Garda and Krzysztof Jajko. Lodz: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Lodzkiego.

- Harris, Samela. 1989. Computer Artist Takes a Byte of the Future. The Advertiser, December 14. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence Culture. New York and London: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Stephen. 2011. Synthetics: Aspects of Art and Technology in Australia. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kolomyjec, Bill. 1987. A Little Piece on Algorithmic Art. Paper presented at SCAN Seventh Annual Symposium on Small Computers in the Arts, Philadelphia, PA, USA, October 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, Ian S. 2005. Josef Stanislaw Ostoja-Kotkowski: Explorer in Light and Sound. Ph.D. thesis, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, Heather. 1989. Requiem for a Paintbrush. The Australian Magazine, October 17, 56–59, 64. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, Heather. 1992. Images from Chaos. Craft Arts International 25: 62–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ostoja-Kotkowski, Stanislaw. 1975. Audio-Kinetic Art with Laser Beams and Electronic Systems. Leonardo 8: 142–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peitgen, Heinz-Otto, and Peter H. Richter. 1986. The Beauty of Fractals: Images of Complex Dynamical Systems. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Scarfe, Robert. 1971. Untitled interview with Ostoja-Kotkowski. The Griffen, March 10, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Stelarc. 1994. Just Beaut to Have Three Hands (Interviewed by Martin Thomas). Continuum 8: 377–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, John. 1992. Ostoja’s Computer Graphics. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey, Helen, Melanie Swalwell, and Angela Ndalianis. 2013. The Popular Memory Archive: Collecting and Exhibiting Player Culture from the 1980s. In Making the History of Computing Relevant. Edited by Arthur Tatnall, Tilly Blyth and Roger Johnson. Berlin and Heidelberg: IFIP/Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey, Helen, Melanie Swalwell, Angela Ndalianis, and Denise De Vries. 2015. Remembering & Exhibiting Games Past: The Popular Memory Archive. Transactions of DiGRA 2. Available online: http://todigra.org/index.php/todigra/article/view/40 (accessed on 30 December 2018).

- Sunday Mail. 1971. 20-story star. Sunday Mail, December 4, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Swalwell, Melanie. 2008. 1980s Home Coding: The Art of Amateur Programming. In Aotearoa Digital Arts Reader. Edited by Stella Brennan and Su Ballard. Auckland: Clouds/ADA, pp. 193–201. [Google Scholar]

- Swalwell, M. 2012. Questions about the Usefulness of Microcomputers in 1980s Australia. Media International Australia 143: 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swalwell, Melanie, Helen Stuckey, and Angela Ndalianis, eds. 2017. Fans and Videogames: Histories, Fandom, Archives. New York and Oxon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Grant D. 2014. When the Machine Made Art: The Troubled History of Computer Art. New York and London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- The Advertiser. 1992. Laser Artist’s Dream in Sight. The Advertiser, January 25. [Google Scholar]

- The Advertiser. 1994. Master who was light years ahead, Obituary: Stan Ostoja-Kotkowski 1922–94. The Advertiser. [Google Scholar]

- Tofts, Darren. 2005. Interzone: Media Arts in Australia. Fisherman’s Bend: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2008. Archives of Joseph Stanislaus Ostoja-Kotkowski. Available online: http://www.amw.org.au/register/listings/archives-joseph-stanislaus-ostoja-kotkowski (accessed on 30 December 2018).

- Victorian Heritage Database. 2019. Former BP House: Statement of Significance. Available online: https://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/places/183680 (accessed on 30 December 2018).

- Zurbrugg, Nicholas. 1994. Electronic Arts in Australia. Continuum 8. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | IBM’s 1977 micro-computer was the original personal computer or ‘PC’. |

| 2 | A description of “paintbox” type programs from the period reads: “paint systems; computers which either through software or design allow the user to draw or paint with the computer. The TV screen (or monitor) of such a paint system will typically contain two borders; one with either patterns or color bands that the user can select and another where the user can choose the ‘tools’ for painting the colors or patterns. Usually the tools are electronic symbols for traditional paint tools, i.e., a brush or pen with varying thicknesses or an airbrush…” (Cancel 1987, p. 9). |

| 3 | Ostoja’s frustration with the reception of his art in Australia is palpable in a 1970 interview:

|

| 4 | Built from 1962–1964 and converted to apartments in 1995, the building at 1–29 Albert Rd, Melbourne (formerly BP House) is now known as the Domain Building. It is on the Heritage Council of Victoria’s Register, considered to be “of state significance as an example of the changing international perceptions by 1960 of the International Style tower”. The Statement of Significance notes that “the combination of architecture and art in the building, a prominent international idea at the time, incorporating a Competition winning foyer mural by Adelaide artist, Stansilaw Ostoja-Kotkowski [sic], and cast bronzes sculptures by noted Victorian sculptor, Norma Redpath, in the Theatrette foyer and exterior façade (Victorian Heritage Database 2019). |

| 5 | We have not been able to definitely resolve the date or the computer system that the star was programmed on (BBC Micro or Acorn Archimedes). Dahms remembers it being a BBC Micro, but we have not found any other evidence that Ostoja had a home computer any earlier than the Acorn Archimedes in 1989. Based on a photo we found in the Warsaw archive, we suspect the computer used was an Archimedes (based on the coloured keys layout on the keyboard and the type of monitor). |

| 6 | Letter from Ostoja to MMT, dated 5 Dec 1989. The special exhibition “Computer Art” for the 1990 Adelaide Festival was cancelled, so it was not shown then. |

| 7 | Electronic media art was excluded from the 1992 Adelaide Biennale of Australian art by the curator. The landscapes with CGI seem to have been shown at the 1994 Adelaide Festival:

Some documents suggest that the presentations of Ostoja’s computer graphics were set to music. We found one slide in the archival collection saying in Polish: “Computer graphics with Vangelis” (SLSA PRG 919/21/242). Russell Dahms remembers being invited to slide shows set to music at Ostoja’s home, so this seems plausible. |

| 8 | Though Ostoja did not belong to this cohort, he was clearly known and respected by local artists. He corresponded with Stelarc (there was talk of them collaborating on a project in Adelaide, but the funding didn’t eventuate) and Stephen Jones. Stelarc noted that:

|

| 9 | Ostoja was eloquent on the role of computers in art, and the potential he saw for computing: it was only ‘natural’— “painters will move from brushes to …” computers (SLSA PRG 919/3/58). He was always looking for new techniques and possibilities, always in search of the artist’s palette of the future that would combine science and art. Electronics played a significant part in his vision, from early on. For example, in an interview from 1970 he said: “Electronics today helps us to execute ideas which we could once only dream about.” And “Exhibitions around the world have proved that electronics can be used very successfully in the works of art, in the exhibitions and the exhibits” (Scarfe 1971). But while electronics was central to his vision, he did not feel that he himself had to master the domain. In the same interview he comments, in response to the question: “… to be able to do electronics you must surely have had electronics training?”, “It’s analogous to you driving a car without knowing how the car is built, you don’t have to know how the engine is built in order to know how to [drive] it”. In McKenzie’s article, Ostoja is quoted as saying: “A pianist doesn’t have to know how to build a piano to play it” (McKenzie 1989, p. 64) |

| 10 | We are still searching to see whether there might be a demo-scene connection. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).