Houses and Daily Life in Islamic Portugal (12th–13th Century): Mértola in the Context of Gharb

Abstract

:1. Introduction

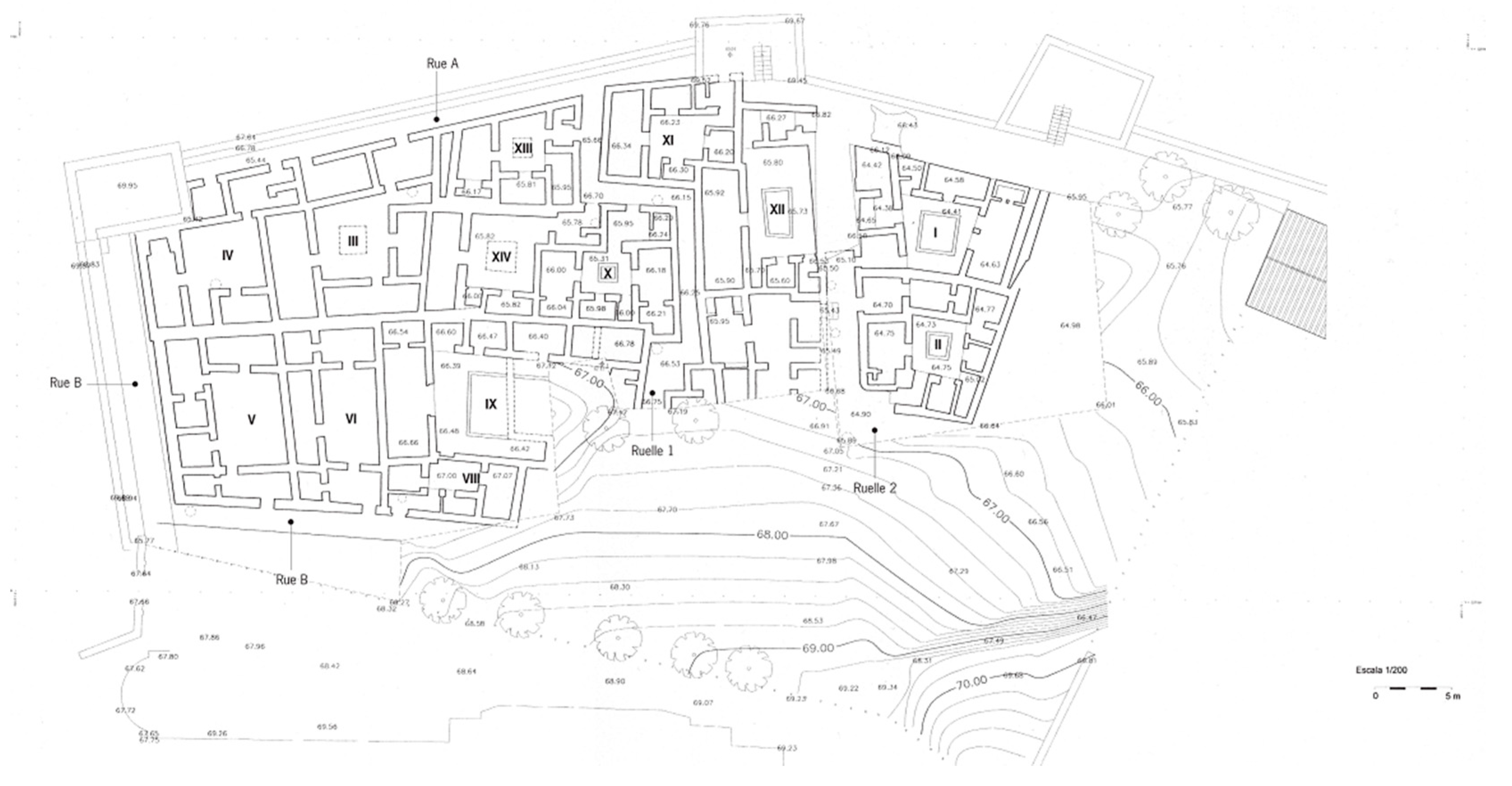

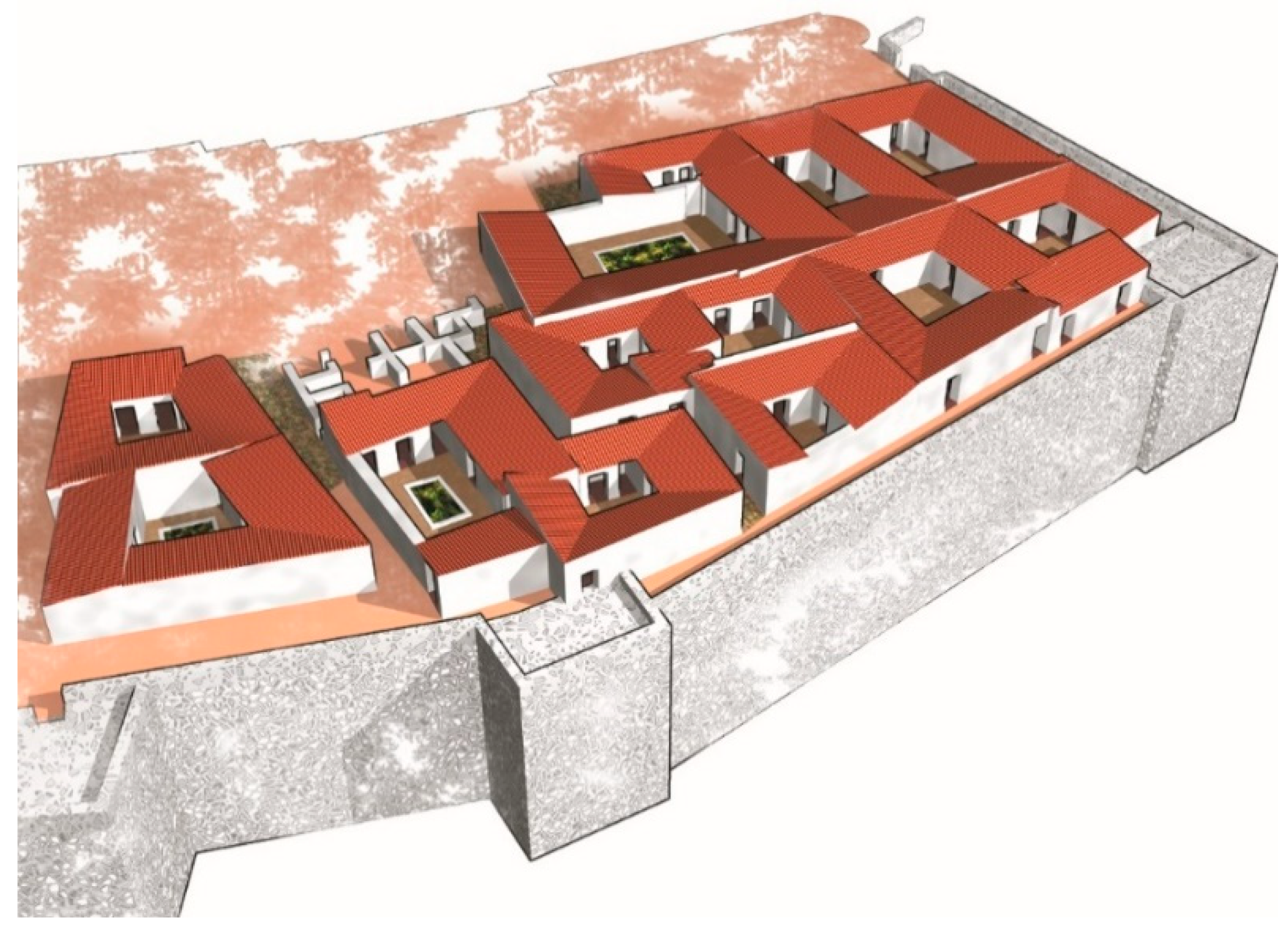

2. Urban Structures

- The orthogonality in urban schemes is not related to whether the city is Christian or Muslim. It is connected to the dependence on an authoritarian power and its capacity to order or impose certain construction programs. Geometric urban layouts, designed according to pre-established architectural schemes, abound in the Medieval Muslim world. That urban geometry is noticeable in the concentric plan of Baghdad, when it was the capital of the Abassid Empire, or Madinat az-Zahra, an orthogonal palatine complex in the classical fashion, fruit of the intervention of a caliphal power with hegemonic pretensions, constructed from scratch and for the exclusive use of the Cordoban caliphal court. Its layout is rigorously quadrangular, and its urbanism is rationally outlined with areas perfectly delineated in accordance with the function of each space (Vallejo Triano 2013, p. 91). There are many other examples such as the outskirts neighbourhood of El Forti, in Denia (Alicante) (Gisbert Santonja et al. 1992, pp. 27, 42 and Figure 7) and the interior of the abandoned city of Saltés (Huelva) (Bedia and Bazzana 1994, p. 625), an urban arrangement that was conceived from scratch and whose plan, street layout and sanitation system were all put in place before the building of the houses.

- On the other hand, it is fitting to remember that the Mediterranean city (and, naturally, the Andalusian city) is designed, first of all, by a rigid classical anti-urbanism. If, in the planning schemes of cities organized in the Alexandrian or Roman fashion, an adopted pattern indicates the presence of a rationalizing power, the mercantile urbe, catalyst of the Mediterranean polis, can be compared to a living body in which all the equilibriums are organic and functional. The old frameworks of the port cities of Génova or Marselha, having in common the fact of never having been Islamicized, possess however an urbanism of an inorganic character, easily categorizable as “Islamic”. In the Mediterranean cities, regardless of being Christian or Muslim, adaptation to the lie of the land was the rule. With the area of power concentrated in the acropolis, the city is organized in an autonomous way following the logic of a conglomerate of neighbourhoods interwoven with vast family clans.

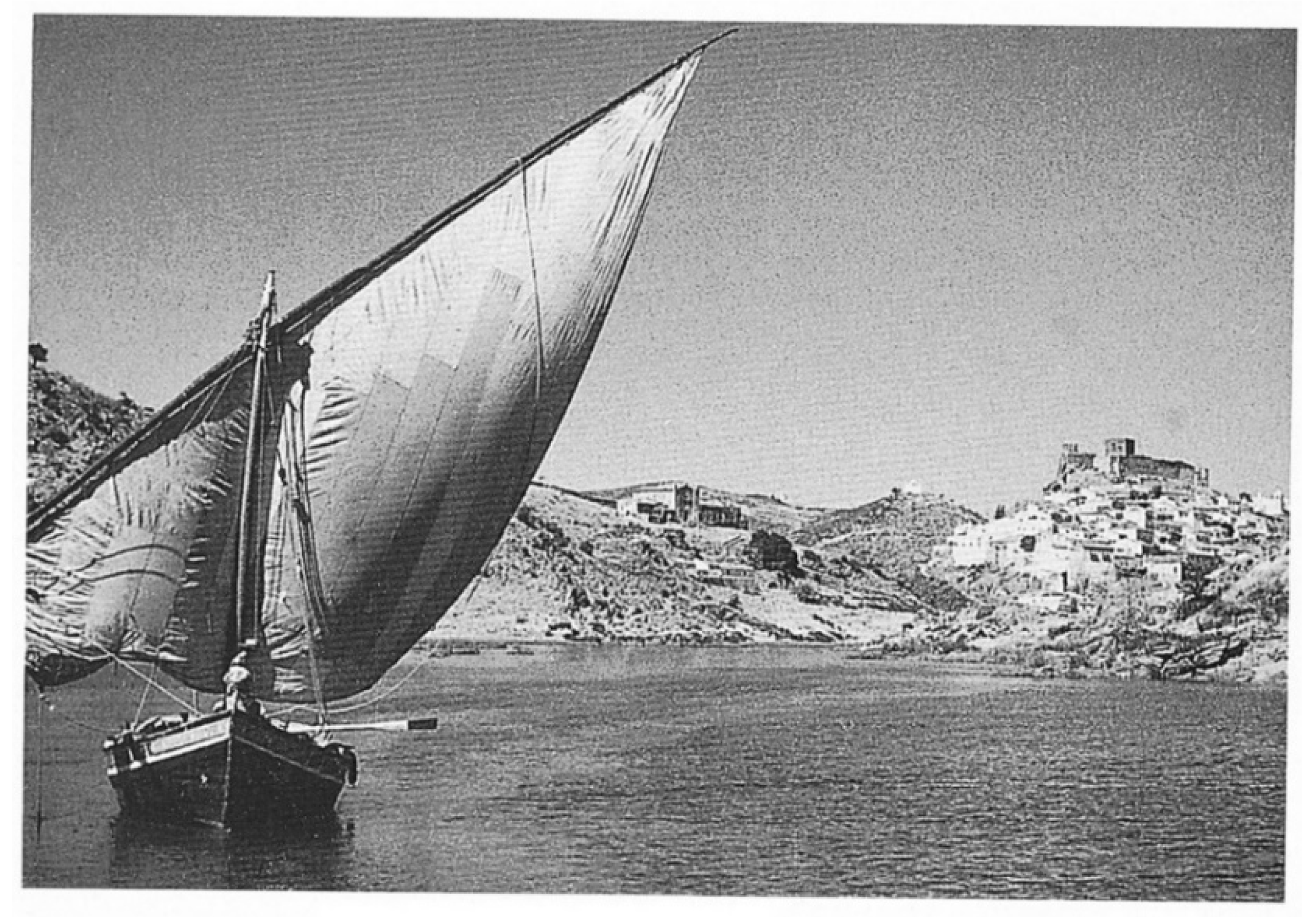

- Most of the cities of Gharb al-Andalus, following a millennial Mediterranean tradition, were organized in the following way: always close to an enclosure and, in the most strategically defendable place, possessing an alcácer (qasr), a cell of eminently military functions, along with the alcáçova (qasaba). This area, nearly always overlapping with the most important spaces of the Roman city, formed a true world apart, closed in on itself. At the side of this nucleus of power grew the city (medina—a name only applicable to the more important cities), normally walled with battlements. Within these walls, it was possible to find the markets, the baths, and the religious spaces etc. and the houses of the local merchant artisans, market-gardeners and peasants. Frequently, in the most important settlements, the city would expand outside its walls, thus creating the outskirts.

3. Habitational Structures

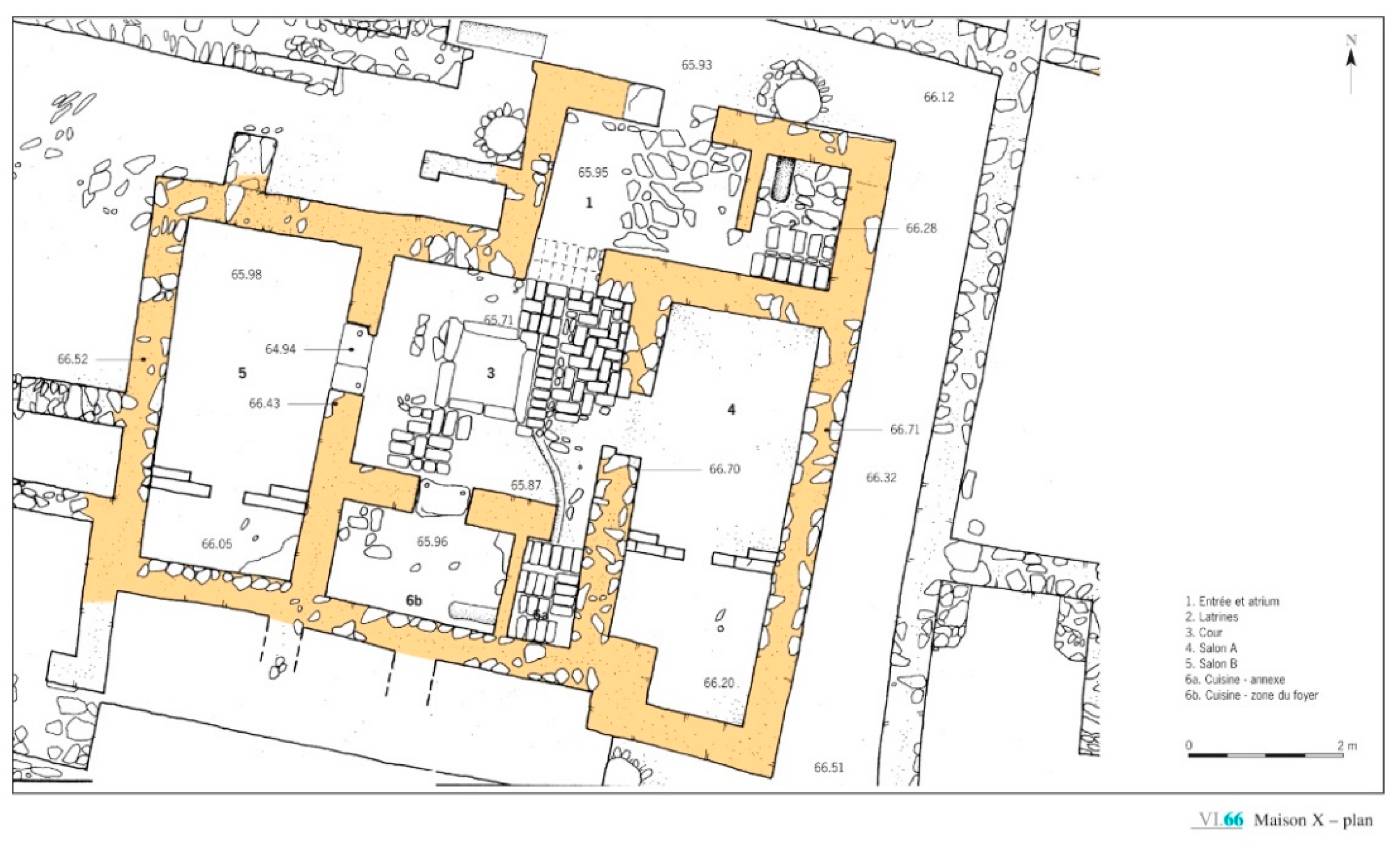

3.1. Entrance through an Atrium

3.2. Uncovered Central Patio

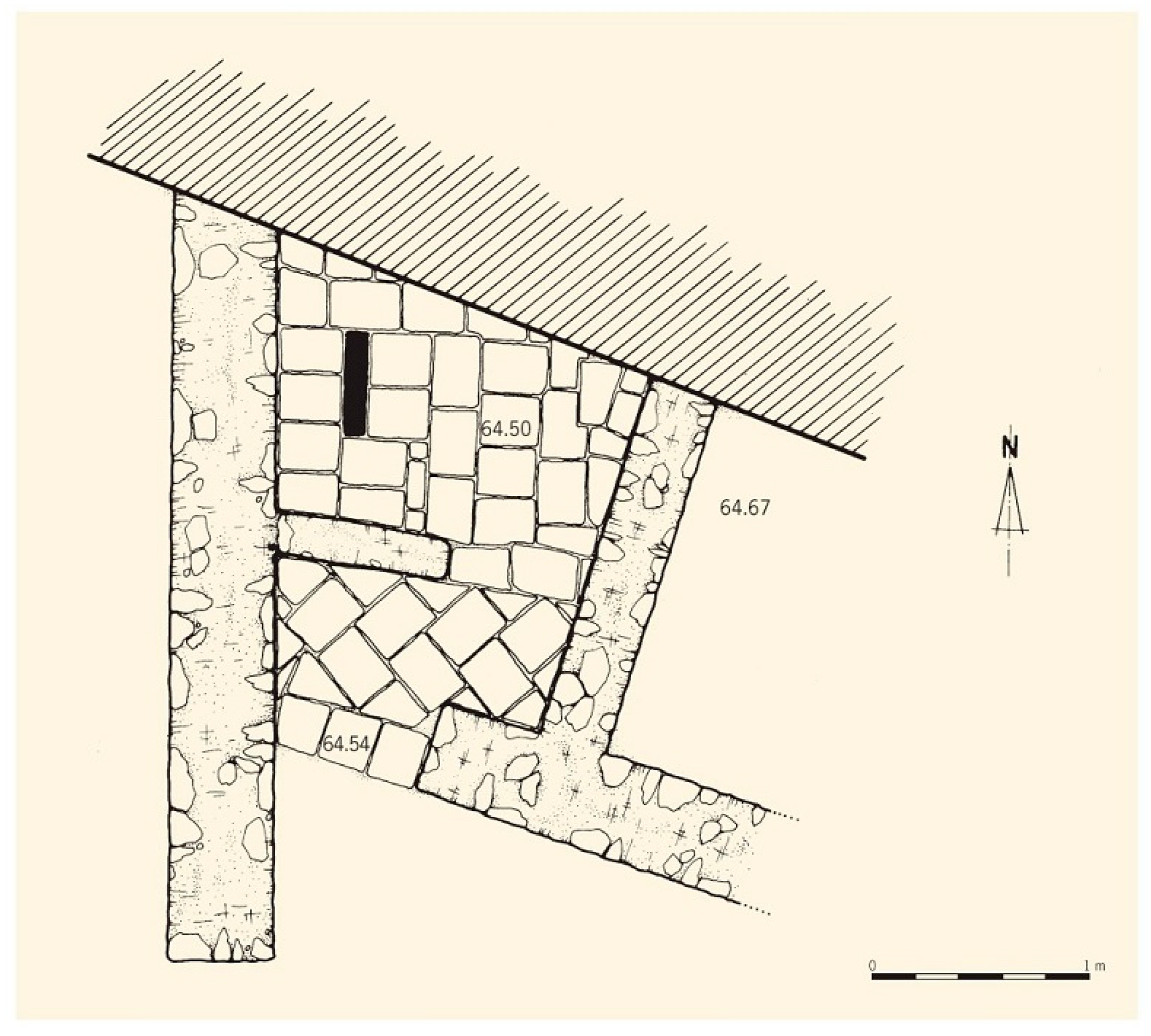

3.3. Principal Room with Mortar Floor, Painted with Red Ochre, with a Small Recess/Alcove in the Top

3.4. Smaller Room of Multiple Functions

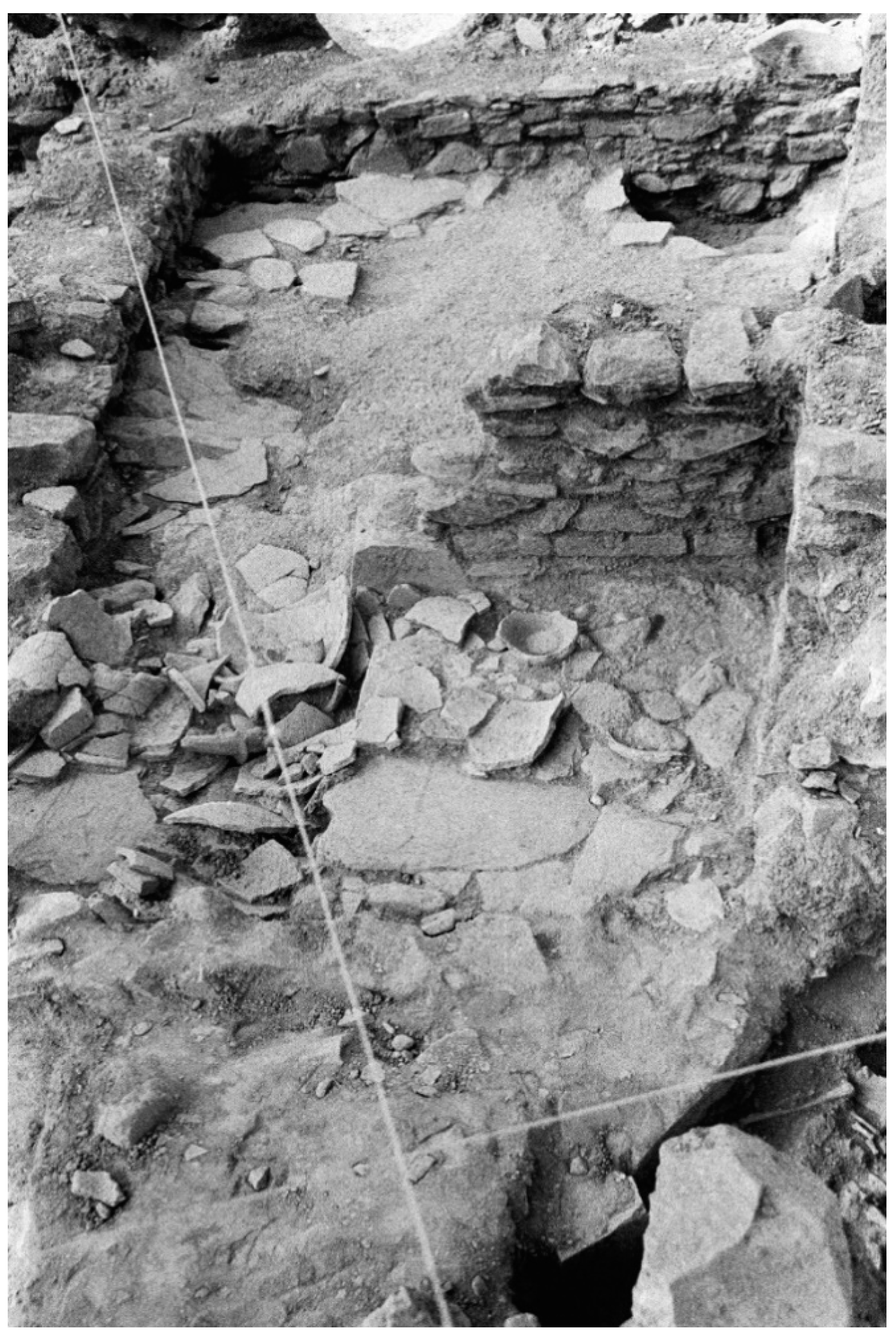

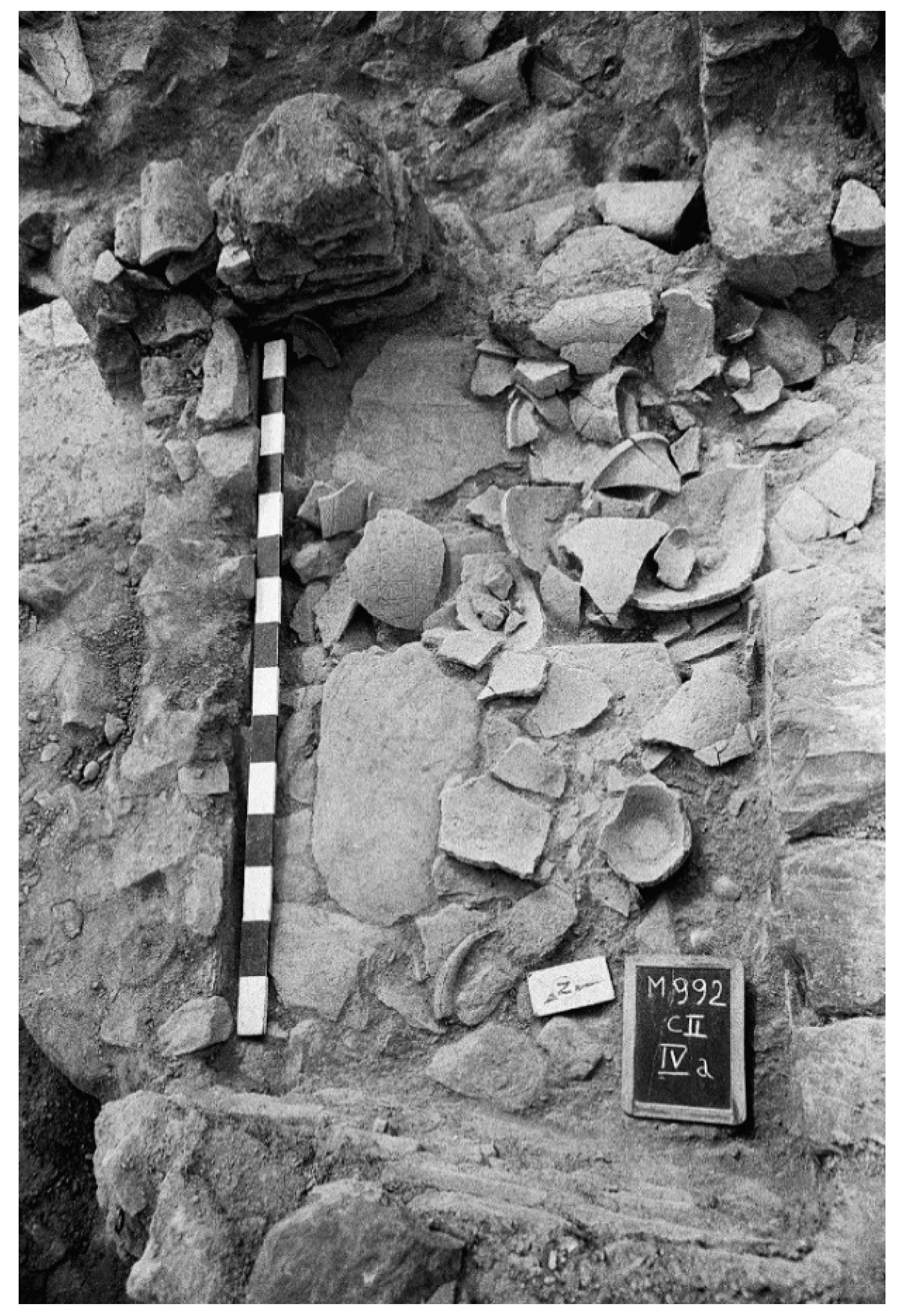

3.5. Kitchen Divided into Two Areas

3.6. A Latrine Directly Linked to a Network of Sewers or Covered Ditches Situated on the Exterior of the House

4. Domestic Life

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bazzana, André. 2005. Excavaciones en la isla de Saltés (Huelva), 1988–2001. Sevilla: Junta de Andalucía/Consejeria de Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- Bedia, J., and André Bazzana. 1994. Saltés y el Suroeste peninsular. In Arqueologia en el entorno del Bajo Guadiana. Huelva: Universidad de Huelva, pp. 619–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bolens, Lucie. 1990. La Cuisine Andalouse. Paris: Albin Michel. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, James. 1994. Rural settlement and islamization in the Lower Alentejo of Portugal. Evidence from Alcaria Longa. In Arqueologia en el entorno del Bajo Guadiana. Huelva: Universidad de Huelva, pp. 527–44. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, James. 2009. Lost Civilization. The Contested Islamic Past in Spain and Portugal. London: Duckworth. [Google Scholar]

- Catarino, Helena. 2005. Arquitectura de taipa no Algarve islâmico. As escavações nos Castelos de Salir (Loulé) e de Paderne (Albufeira). In Arquitectura de terra em Portugal. Lisboa: Argumentum, pp. 138–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cavaco, Sandra. 2011. O arrabalde da Bela Fria: Contributos para o Estudo da Tavira Islâmica. Master’s dissertation, Faculdade de Ciências Humanas e Sociais da Universidade do Algarve, Faro, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, António Borges. 1975. Portugal na Espanha Árabe. Lisboa: Seara Nova, vol. IV. [Google Scholar]

- Conde, Manuel Sílvio. 1997. Sobre a casa urbana no Centro e Sul de Portugal, nos finais da Idade Média. Arqueologia Medieval 5: 243–65. [Google Scholar]

- de Matos, José Luís. 1999. Lisboa Islâmica. Lisboa: Instituto Camões. [Google Scholar]

- Galdeano, Francisco Castillo, and Rafael Martínez Madrid. 1990. La vivienda hispanomusulmana en Bayyana-Pechina (Almeria). In La Casa Hispano-Musulamana. Aportaciones de la Arqueologia. Granada: Patronato de La Alhambra y Generalife, pp. 111–27. [Google Scholar]

- García Gómez, Emilio, and Lévi-Provençal Évariste. 1981. Sevilla a Comienzos del siglo XII. El tratado de Ibn Abdun. Sevilla: Servicio Municipal de Publicaciones. [Google Scholar]

- Gisbert Santonja, Josep A., Vicent Burguera Sanmateu, and Bolufer I Marques Joaquin. 1992. La Cerámica de Daniya (Dénia)-alfares y Ajuares Domésticos de los Siglos XII–XIII. Valencia: Ministerio de Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, Rosa Varela. 2009. O Castelo de Silves-contributos de investigação recente. Xelb 9: 477–88. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, Ana, and Maria Alexandra Gaspar. 2002. O Castelo de S. Jorge–da fortaleza islâmica à alcáçova cristã. In Mil anos de fortificações na Península Ibérica e no Magreb (500–1500). Actas do Simpósio Internacional Sobre Castelos. Lisbon: Edições Colibri, pp. 397–404. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, Maria José. 2008a. Silves Islâmica: A Muralha do Arrabalde Oriental e a Dinâmica de Ocupação do Espaço Adjacente. Master’s dissertation, Faculdade de Ciências Humanas e Sociais da Universidade do Algarve, Faro, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, Maria José. 2008b. Silves Islâmica: A Muralha do Arrabalde Oriental e a Dinâmica de Ocupação do Espaço Adjacente. Master’s dissertation, Faculdade de Ciências Humanas e Sociais da Universidade do Algarve, Faro, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Bermejo, J. Esteban. 1990. Dificultades en la identificación e interpretación de las espécies vegetales citadas por los autores hispano-árabes. Aplicación a la obra de Ibn Bassal. In Ciencias de la Naturaleza en al-Andalus. Textos y Estudios. Madrid: Editorial CSIC-CSIC Press, pp. 241–63. [Google Scholar]

- Inácio, Isabel, and Helena Catarino. 2009. Ensaio de reconstituição de casas islâmicas do Castelo de Paderne. Xelb 9: 613–22. [Google Scholar]

- Leitão, Maria Isabel Caetano. 2015. A Presença Islâmica em al-Qasr—Uma Análise Sobre o Urbanismo e o Sistema Defensivo. Master’s dissertation, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Macias, Santiago. 1996. Mértola. Estudo Histórico-Arqueológico do Bairro da Alcáçova (sécs. XII–VIII). Mértola: Campo Arqueológico de Mértola. [Google Scholar]

- Macias, Santiago. 2006. Mértola. Le Dernier port de la Méditerranée. Mértola: Campo Arqueológico de Mértola, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Macias, Santiago, José Gonçalo Valente, and Vanessa Gaspar. 2016. Castelo de Moura—Escavações Arqueológicas 1989–2013 (Textos). Moura: Câmara Municipal de Moura. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Palazon, Julio. 1990. La casa Andalusí en Siyasa: Ensayo para una Clasificacion Tipologica. La casa Hispano-Musulamana Aportaciones de la Arqueologia. Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife, pp. 177–98. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, Maria de Fátima, Miguel Reimão Costa, Susana Gómez Martínez, Virgílio Lopes, and Ana Costa Rosado. 2018. As casas de Mértola: dois mil anos de formas de habitar. Arqueologia Medieval 14: 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, Maria Teresa Lopes. 2000. Alcácer do Sal na Idade Média. Lisboa: Ed. Colibri/Câmara Municipal de Alcácer do Sal. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, Cláudio. 1992. O Garb al-Andaluz. In História de Portugal. Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores, vol. I, pp. 363–415. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo Triano, Antonio. 2013. Madinat Al-Zahra: Historical reality and present-day heritage. In Reflections on Qurtuba in the 21st Century. Madrid: Casa Árabe, pp. 89–109. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Macias, S. Houses and Daily Life in Islamic Portugal (12th–13th Century): Mértola in the Context of Gharb. Arts 2018, 7, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040077

Macias S. Houses and Daily Life in Islamic Portugal (12th–13th Century): Mértola in the Context of Gharb. Arts. 2018; 7(4):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040077

Chicago/Turabian StyleMacias, Santiago. 2018. "Houses and Daily Life in Islamic Portugal (12th–13th Century): Mértola in the Context of Gharb" Arts 7, no. 4: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040077

APA StyleMacias, S. (2018). Houses and Daily Life in Islamic Portugal (12th–13th Century): Mértola in the Context of Gharb. Arts, 7(4), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040077