1. Introduction

Construction of the Alhambra monumental complex in Granada began during the Nasrid dynasty (1232–1492), once the city was conquered in 1237. During the more than three hundred years of al-Andalus rule, the palace-fortress was extended and renovated. After 1492, building work did not cease with the Christian conquest, as many of the complex’s infrastructures were maintained, albeit being adapted to their new needs and uses.

The Alhambra provides us with a vast repertoire of building types, most of which feature painstakingly-detailed glazed ceramic work on the carved or moulded dadoes, chiselled or moulded plaster wall coverings, and polychrome, either magnificent or more simple ceilings. Of these three elements, this study focuses mainly on the architectural ceramics, as they are clearly an inherent part of the Nasrid Alhambra. However, it would be unwise to think that the ceramic mosaic panels or alicatados that currently offer such colourful adornment to Nasrid palaces all come from the time of al-Andalus. Replacement work carried out immediately after the Christian conquest, the introduction of new emblems and symbols, adaptations to new uses, and restoration work to recover an image that is more originally Islamic have all meant that these pieces have undergone significant intervention. The study of the Alhambra’s architectural ceramics is therefore extremely complex, requiring the consultation of numerous sources. Nevertheless, it affords us a greater understanding of the palace-fortress as it gives us the chance to better appreciate its many vicissitudes, its successes and failures, which have led to the Alhambra we know today.

Fully aware of this importance, in 2016, the Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife (Council of the Alhambra and the Generalife) entered into an agreement with the University of Granada entitled “The Alhambra’s Architectural Ceramics”. Its basis was the recognition that this form of artistic expression has undergone many changes over time. For this reason, detailed research was needed into a large part of this material, which today can be seen in the architecture of the monumental complex as well as in the Alhambra Museum’s collections. The study of this material involves the recovery of all the information from the archive, which becomes essential to ensuring the success of the research and it is undertaken rigorously and thoroughly. This aspect was the aim of the signed agreement, the launch of the Alhambra’s architectural ceramics documentary corpus.

The corpus is systematised via a simple database that nevertheless includes complete archival, bibliographical, and image references. As far as the bibliography is concerned, it includes both classical and general works and more recent articles and books that deal specifically with the Alhambra’s architectural ceramics, offering new research perspectives. We have taken information from a number of works, above all from books on the subject, regarding the descriptions of the areas referred to, facilitating bibliographic searches on the current information that is available regarding specific parts of the palace-fortress complex.

As far as the images were concerned, most came from the Council of the Alhambra and the Generalife Archive’s various digital collections, as well as the Council’s library. The most important criterion was the age of the image, although the greatest possible sharpness was also sought in order to better appreciate the various ceramic elements. As far as possible, we have avoided the repetition of images showing similar views of the same scene and which do not provide any new information. We were interested in images that showed spaces that allowed us to analyse changes to the architectural ceramics, in such a way that, for instance, in one we might see ceramic elements with gaps in the design, while in another, these have been filled in with replacement pieces, or also quite the opposite, since both types of examples can be seen in the Alhambra. We did not disregard any image, from the oldest photographs to the most recent, from paintings and engravings from various periods to drawings and plans of both ground layouts and front elevations showing dadoes.

With regard to the document database, it contains copies of contracts and reports for the restoration of architectural ceramic elements in a number of areas of the complex. To this end, we consulted the archives of the Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife and specifically its collection from the Fondo del Patronato de la Junta de Andalucía. We are also carefully transcribing and analysing hundreds of files from the aforesaid archive, which give an excellent account of the Alhambra’s history since the 16th century, extracting the most interesting information and making a brief summary that highlights the essence of each of these documents.

There is much still to be done. In the future, we hope to be able to draw up a “map” of the Alhambra’s architectural ceramic pieces that is sound in terms of its originality and chronology.

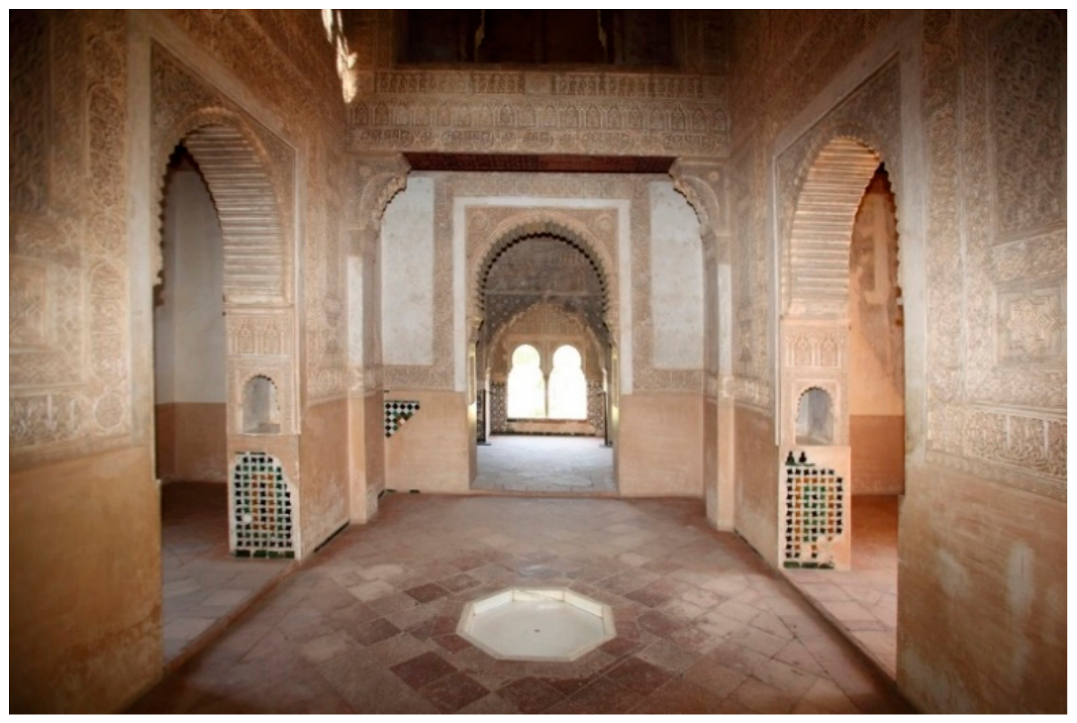

2. The Alhambra as a Palatine City

The Alhambra was originally a Nasrid palatine city. It was the centre of power and residence of the sultans who made Granada the capital of what was then called Reino de Granada. The art that was produced during the Nasrid period dates principally from 1237 to 1492, corresponding to the years of the occupation and abandonment of Granada. In order to understand Nasrid art, one has to study Granada as a city and its architecture. However, this is not the only area to be analysed, as the dynasty’s art extended to the region of Murcia, to Almería and to Málaga, reaching the Strait of Gibraltar and its strategically important enclaves of Algeciras and Tarifa (

Figure 1).

The Alhambra of the 13th century was very different to that of the first half of the 14th century and the early 15th century. Spaces changed with the new building work that each sultan wanted to undertake in order to leave his indelible mark on history (

Díez Jorge et al. 2006, pp. 20–32). Above all, the Alhambra was a city and the experience of living within it was as such. This was a city built for power, for the royal family, and their whole entourage. It required the provision of a wide range of domestic services and workshops.

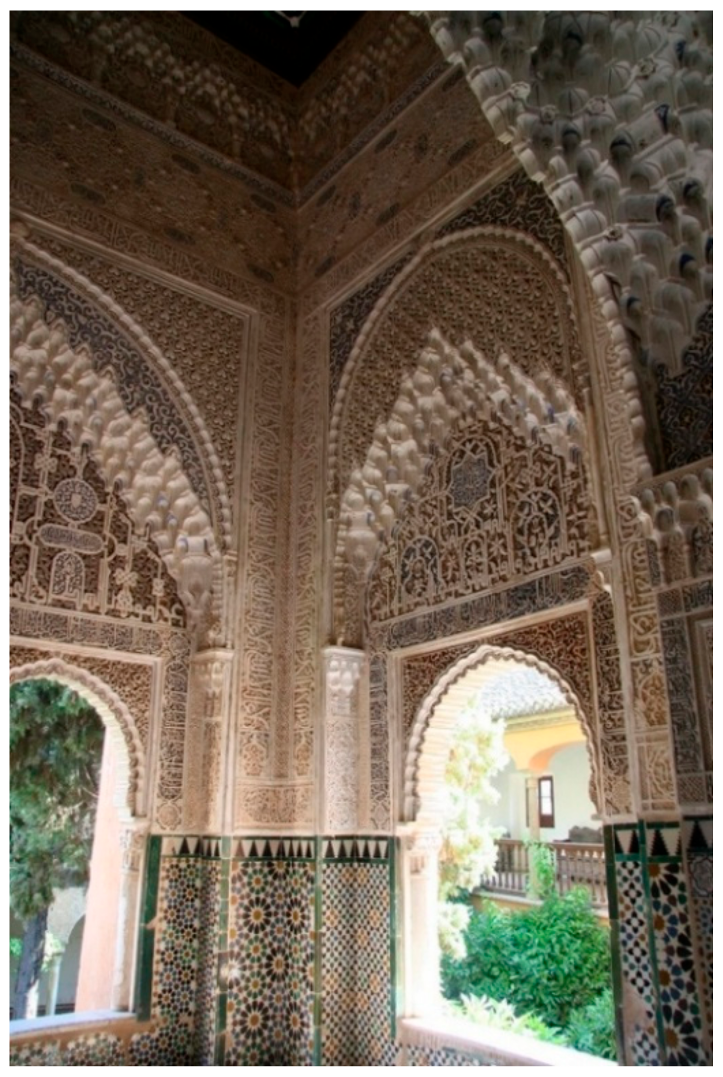

The Alhambra is seen as the pinnacle of Nasrid art. Its beauty and splendour were praised by both the Muslims and Christians who set eyes upon it. One of the Alhambra’s poets, Ibn al-Yayyab, made special mention of its fine plasterwork, ceramic tile mosaics, and ceilings (

Rubiera Mata 1982, pp. 112, 114) (

Figure 2). This widespread admiration has been maintained over time, this is particularly the case with Romantic travellers (on different travellers and their vision of the Alhambra, see

Galera Andreu 1992). It is true that nineteenth-century historiography took the view that Nasrid art lacked balance and characterised some of it as being chaotic and extravagant, full of fantasy, caprice, and seduction, and essentially designed to satisfy the corporal pleasures of a decrepit court. The Alhambra was described at that time in some sources as an immense pleasure centre, with its gardens and running water, and the folly and despotism of its corrupt rulers in the harem. The role of the palatine city was identified more than political activities with incessant galas and balls, and yet these learned travelers nevertheless brought the Alhambra to light, holding it in great esteem (

Díez Jorge 2005).

In traditional historiography, Nasrid art was seen as the beginning of a decline of al-Andalus art, as the ongoing vassalage to Castile represented the end of the independence that had characterised periods, such as that of the Umayyad Caliphate in Córdoba. Obviously, not all of the Nasrid period was one of continuous decline. The most stable periods came during times of peace with Castile during the rule of Yusuf I (from 1333 to 1354) and Muhammad V, a time that also saw the height of Nasrid artistic splendour, materialising in the Alhambra’s Comares Palace and the Palace of the Lions. This was also a period in which the export of glazed ceramics grew, as did the prestigious silk industry (see

Figure 3). On the other hand, the 15th century highlighted the decadence and artistic twilight of the Nasrids, in which the height of abandonment coincided with the rule of Boabdil in 1482 and from 1487 to 1492. Perhaps this contrast of a period of splendour followed by one of decadence, while nonetheless real to a greater or lesser extent, has been exaggerated, based above all on the chronology and attributes assigned to certain parts to the Alhambra. The reality was somewhat more complex. Although a more stable political panorama obviously contributed toward greater artistic production, which was probably, in contrast, drastically reduced due to the lack of money in subsequent times of crisis; it is also true to say that creativity and imagination do not always depend on the prevailing economic situation. Without forgetting the magnificent Alhambra palaces built by Yusuf I and Muhammad V in the 14th century, there were also important contributions made at other times: the Partal, a fine example of open architecture because it includes a portico with balconies that have views to the river Darro and San Pedro and Albaicín quarters, as well as a covered balcony that is accessed from a staircase (for more information about this palace, see

Orihuela Uzal 1996, pp. 57–70) and that is attributed to Muhammad III (1302–1309) at a time of uneasiness, with the Alhambra surviving an internal coup, and problems with the Marinids; or the sumptuous Tower of the Princesses (Torre de las Infantas), built under the rule of Muhammad VII (1392–1408) in the early 15th century (see

Figure 4). Such works should cause us to question this idea that Nasrid art was uninventive and repetitive, relying too heavily on al-Andalus’s past as it has also been proved with other cultural aspects from the Nasrid period, such as poetry (

Puerta Vílchez 2000).

Admitting Nasrid art’s original forms does not mean that we ignore the imitation of earlier models, nor is it contradictory to recognise artistic multiculturality. Architecturally and artistically, this diversity has not been jointly analysed, although scattered data in a great deal of the existing research constantly point to this being the possible result of the influence of Christian kingdoms in the way that the Partal palace opens to the outside, in the cloister-like forms of the Court of the Lions (Patio de los Leones), and in the paintings in the Kings’ Hall (Sala de los Reyes), which have been the source of so many fascinating hypotheses regarding cultural relations at the time (

Robinson and Pinet 2008).

Having said this, we should bear in mind that as we walk through the Alhambra today, not all we see is Nasrid. Specialists have to attempted to discern the provenance of the architectural and stylistic forms, as well as highlighting the presence of inter-relationships, loans, and exchanges. We should view the various interventions and repairs in such a way that admits the fact that at some point there may have been misinterpretations of how things were during the Nasrid period, or attempts to give the work what was regarded as a “more Islamic” air. One time of unquestionable importance was right after the conquest of the Alhambra by the Catholic Monarchs in 1492, as the Christian forces decided to maintain the complex as a palatine city. The site of the Alhambra makes it a visual and symbolic point of reference, as well as inspiring the admiration and respect of the Catholic Monarchs for this place (

Díez Jorge 1998). One element on which the repairs and interventions were well-documented from the outset are the glazed ceramic tiles or the

alicatados (see

Figure 5).

3. The Alhambra’s Architectural Ceramics

Within this world of splendour without which it is impossible to understand the Alhambra, architectural ceramics played a fundamental role. Fabrics and carpets in vivid colours, polychrome plasterwork, gold and blue ceilings, objects replete with metallic reflections, and, everywhere, brightly coloured shining glazed pieces that were used from the floor to the rafters.

Floors combined terracotta tiles with small glazed pieces known as

olambrillas. Floors also featured

almatrayas, a series of glazed ceramic pieces which generally formed a rectangle before the main door to a house or other rooms therein. The Alhambra still has the remains of these Nasrid

almatrayas combined with terracotta tiles, although sometimes the glazed ceramic pieces are missing, as is the case with the houses alongside the Gate of the Seven Floors (Puerta de los Siete Suelos, see

Figure 6). However, the Alhambra, as a royal seat and centre of power, had a flooring that is rarely found elsewhere, due to its cost and the techniques involved, such as the ceramic tiles, which are currently on display at the Alhambra Museum, featuring figurative elements dated as being from the 14th century and that seem to have been used in the Queen’s Dressing Room tower (Torre del Peinador de la Reina) and the Alijares Palace. Similar pieces from the Alhambra can be found in other collections, such as that pertaining to the Instituto Valencia de Don Juan (

Nebreda Martín 2016, p. 530 et seq.), which also includes a ceramic panel known as the Fortuny tile which some researchers claim was found in a house on the Acera del Darro (

Nebreda Martín 2016, p. 565) and that is usually interpreted as being from the base of a door frame (

Marinetto Sánchez 2000b). Dadoes and column bases also feature glazed ceramics, giving the impression that some parts of the Alhambra were covered in bright colourful glass carpets.

On the walls, the glazed ceramic mosaics appear in the dadoes, the often decorated bottom third of the walls, with a wide range of techniques and designs used. Traditionally, during the different phases of Andalusi art, dadoes received a lot of attention, and not only in palaces, but also in more humble abodes, with their simple geometric motifs or beautifully intricate designs featuring intertwined loops and plant elements (

García Granados 2014). The Alhambra also features painted dadoes from the Nasrid era, such as those in the Court of the Harem (Patio del Harén) in the Palace of the Lions, or in the latrine near the Hall of the Boat (Sala de la Barca) in the Comares Palace (see

Figure 7). However, undoubtedly, it was the glazed ceramic mosaic tiles, especially the

alicatados, which were used in the most formal of rooms, as in the 14th century this was an expensive technique that, in general, although not always, was reserved for more ostentatious places. Some columns appear covered in

alicatado pieces, making real what had seemed impossible, given that it meant having to cut the pieces to fit a curved surface (see

Figure 8). As far as we are concerned, for the specific case of al-Andalus, we have only seen this type of

alicatado on a curved surface in the Alhambra, although this does not mean that there were not any other ones that we could eventually find. There are capitals made from glazed ceramics that evidently could not withstand heavy loads as they were hollow, and which played a more decorative role. Some of these capitals have become well-known through publications (

Marinetto Sánchez 2000a), although the Alhambra Museum’s collection has other examples that we have been able to see, some of which are very small fragments of unknown origin (Alhambra Museum, refs. 3815 and 105558). However, they speak to us of the Alhambra in a very different way to how we see the complex today, as, in general, these pieces cannot be seen in situ.

There are more pieces in the Alhambra Museum collection, such as the glazed ceramic latticework (

Marinetto Sánchez 2000b), while others are still visible to any visitor, such as the

sebka panels on the Justice Gate (Puerta de la Justicia) or the

cuerda seca1 on the spandrels on either side of the arch of the Wine Gate (Puerta del Vino) (see

Figure 9). We can also mention the tiled roofs that could combine various colours or the vaulted arches of the Nasrid baths, whose skylights are made from glazed ceramic. The vaulted arches of the Comares baths have recently been restored by the architect Pedro Salmerón (between October 2014 and July 2017), while the ceramic skylights, among other pieces, have been returned to their former glory by the restorers María Dolores Blanca López and Lourdes Blanca López. Nonetheless, these are not the only glazed ceramic skylights in the Alhambra, as others have been conserved that are almost complete (Alhambra Museum, ref. 86807) or in fragments (ref. 124440, ref. 124441, ref. 124442, ref. 124444, ref. 12448, ref. 124450, ref. 80200, ref. 87877, ref. 87881, ref. 87882, ref. 87904, ref. 81906, ref. 87911, ref. 87913, ref. 87915, ref. 87916, ref. 87917, ref. 87918, ref. 87931, ref. 87886, ref. 87897, ref. 97927, and ref. 91243). They come from the baths at the current Parador de San Francisco hotel, a former Nasrid palace, while others are of unknown origin (see

Figure 10).

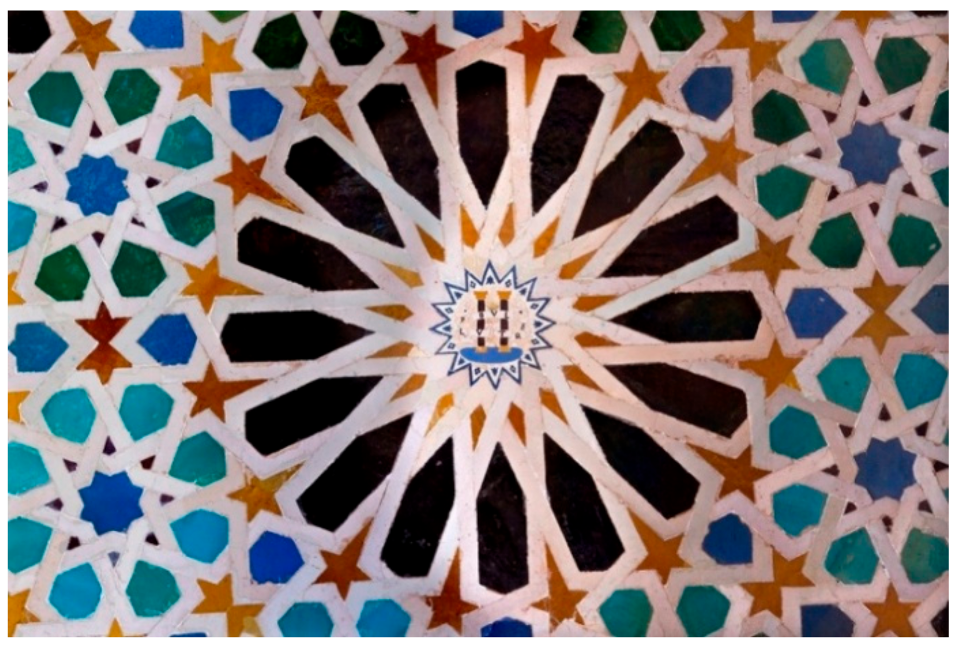

The use of architectural ceramics in the Islamic world is wide and varied in terms of the techniques, materials and colours used (

Degeorge and Porter 2001). In the case of Nasrid architecture, in the main areas reserved for the nobility, it is worth mentioning the use of

alicatados on the dadoes. Traditionally it has been said that

alicatados (

zillij or

zellij in Arabic) could already be found in the Maghreb and al-Andalus in the 12th and 13th centuries, as can still be seen, for example, in Marrakech, both on the Kutubbiyah minaret, which uses turquoise green and white tiling, and in the

qasba (

Benassa 1992). Previously, for example, during the Umayyad Caliphate, tessera and

opus sectile were more commonly used in place of

alicatados. The best known use of the

alicatado technique flourished in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, appearing simultaneously in a number of regions, including Granada. The variety of the work in the Alhambra has been studied at length by a number of academics who have analysed in great depth the complex designs and narratives that can be found there (

Pérez Gómez et al. 2007;

García Granados 2014;

Martínez Vela 2017), as well as the wide range of colours used (

Bush 2011), although an accurate chronology of them has yet to be made. In the case of the

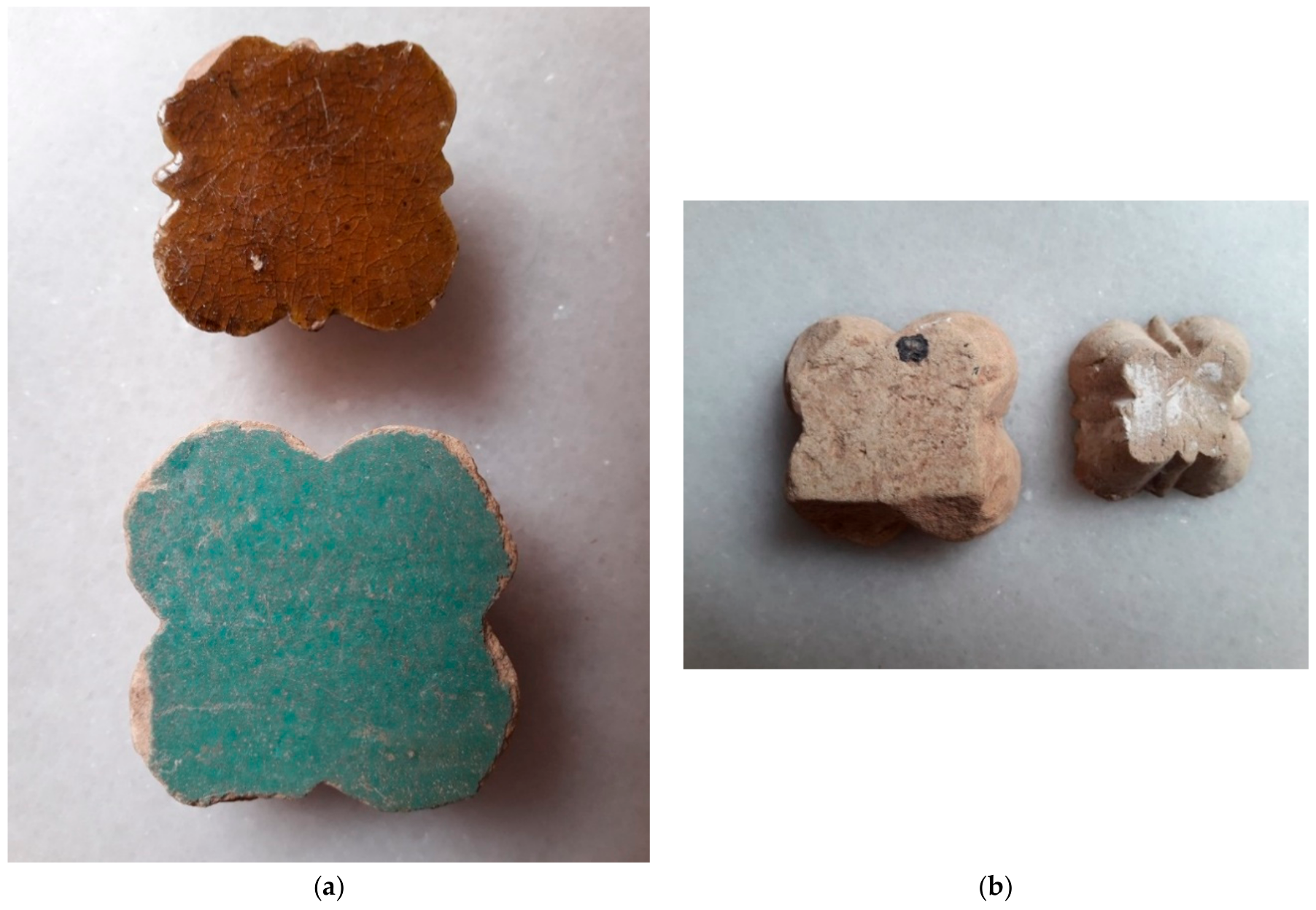

alicatado works, and depending on the design in question, a craftsman would cut the pieces (

Figure 11) from a fired and glazed monochrome sheet and place them face down almost like a jigsaw puzzle, which is based on the design and the colour used. The individual elements were set into a panel with mortar and then the panel was attached to the wall with the mortar as well.

Nevertheless, as we have previously mentioned, other techniques were also used. Among these is that of

incrustación, which is very specific to the Alhambra (

Sánchez Gómez et al. 2018), which consisted of producing glazed tiles that were then encrusted into these other glazed ceramic pieces.

The technique of alicatado continued to be used, with certain variations, after the Christian conquest, making the study of architectural ceramics in the Alhambra all the more complex and rewarding. Some examples of this work can be seen at the Architectural Ceramics exhibition at the Alhambra Museum, which opened on 18 May 2018 and will run until 21 April 2019.

Since the Christian conquest, there have been a number or repairs to and other intervention on the Nasrid pieces, as well as new additions. Some are easily recognisable, as they employ techniques such as those used on the

cuenca or

arista2 tiles that were more common in the late 15th century, and, above all, in the 16th century; or else because they use motifs from the 16th century onward (see

Figure 12). However, in other cases, it is difficult to situate them chronologically. It is this aspect that has, in part, been the motivation for this project. One of the Alhambra’s most vulnerable areas has always been its

alicatados, as various pieces have been replaced without a reliable study of their chronology. This has meant that it is not unusual to find Nasrid mosaic tiles mixed with later pieces, the result of repairs made not only long ago, but also more recently. Fortunately, in the present day, interventions are more carefully controlled. This complexity can clearly be seen in the case of the numerous repairs and other interventions that have been made to the Comares baths throughout history (

Díez Jorge 2007). Nonetheless, it is also evident in other pieces, such as some of the repairs made to the Mexuar (

Sánchez Gómez et al. 2018).

As a result, what we find today in the Alhambra is Nasrid alicatado panels that have been altered since the Christian conquest, pieces from the 16th century mixed with others from the Nasrid period, 19th century interventions that have invented new designs and the replacement of pieces with the sole criterion that the gaps should not be visible to visitors. A complex situation, in other words.

It should be remembered that, after the Christian conquest, architectural ceramics were used in numerous buildings in the Kingdom of Granada. This was not only the case in the Alhambra, which passed into the hands of the Christian royal household, but also in numerous other instances throughout the city, in the churches and other civil buildings in which mainly

arista tiles and

olambrillas were used in the floors, on the landings on staircases, dadoes in hallways and other rooms, altars, bell towers, and so on. In the case of the Alhambra, the problem is discerning between work from the Nasrid and the Christian periods, as very often Nasrid pieces were reused or copied (

Gómez-Moreno Calera 2000).

Based on over 1300 documents that we have consulted to date, the procedure followed throughout the 16th and 17th centuries tended to be that when the Alhambra’s royal works needed materials, such as glazed tiles, bricks, and roof tiles, at the behest of the master builder and his officials, they would be put out to tender, which would be announced for days before in the city’s public squares by the town crier, accompanied by the Alhambra’s scribe who would attest to the proceedings. As far as the roof tiles and bricks were concerned, the town crier might be accompanied by the scribe and the bailiff to announce the tender in the villages where there were brick and roof tile kilns, nearly always in Gabia la Grande and Pago del Campo del Fresno. Very often, when there was a pressing need for these materials, they would be directly embargoed, ordering the brick and tile makers to take them to the Alhambra, where they would later be paid at the going rate in the city.

The bills of materials and promissory notes from the period also document the payments that were made for the roof tiles and the

rasilla and

mazarí3 bricks to be used in the Alhambra and delivered to the site manager. In most cases, there is no record of the location where the materials had to be sent. Daily and weekly payments were also documented in the receipts and payment notes given to the brick cutters, scrapers, and layers, as well as the floor layers and wall liners; in all cases, they were the master craftsmen, the journeymen, and the labourers.

From the late 16th century to the early 17th century there are letters and deeds of obligation to master tile makers that set out the stipulated delivery and payment conditions, as well as records of the warrants and orders given to master craftsmen and senior journeymen in the tenders, reverse auctions, reserved bids, prices pre-offered by the buyer, new tenders, and successful bids.

Payments were normally made in three or four installments. The first two or three of these were advance payments, with the first corresponding to a third of the total sum established in the contract, allowing the craftsmen to purchase their materials. The second advance payment (and third, if required) would pay a further third when the materials had been delivered to the site manager at the Alhambra, with the final payment made when all the materials cited in the contract were delivered. On occasion, the materials were not delivered to the Alhambra, but taken there by mule teams.

There is documentation referring to inventories from various years detailing the tiles that were kept in the stores. Of special interest here are the declarations made by master craftsmen inspecting the spaces in the Alhambra, highlighting the lack of these glazed tiles specifying with the vara castellana (0.83 m) on the alicatado panels.

It is clear to see that there was incessant activity with regard to the Alhambra’s architectural ceramics for centuries. By way of example, here we have our case study of the Cuarto Dorado.

5. Results

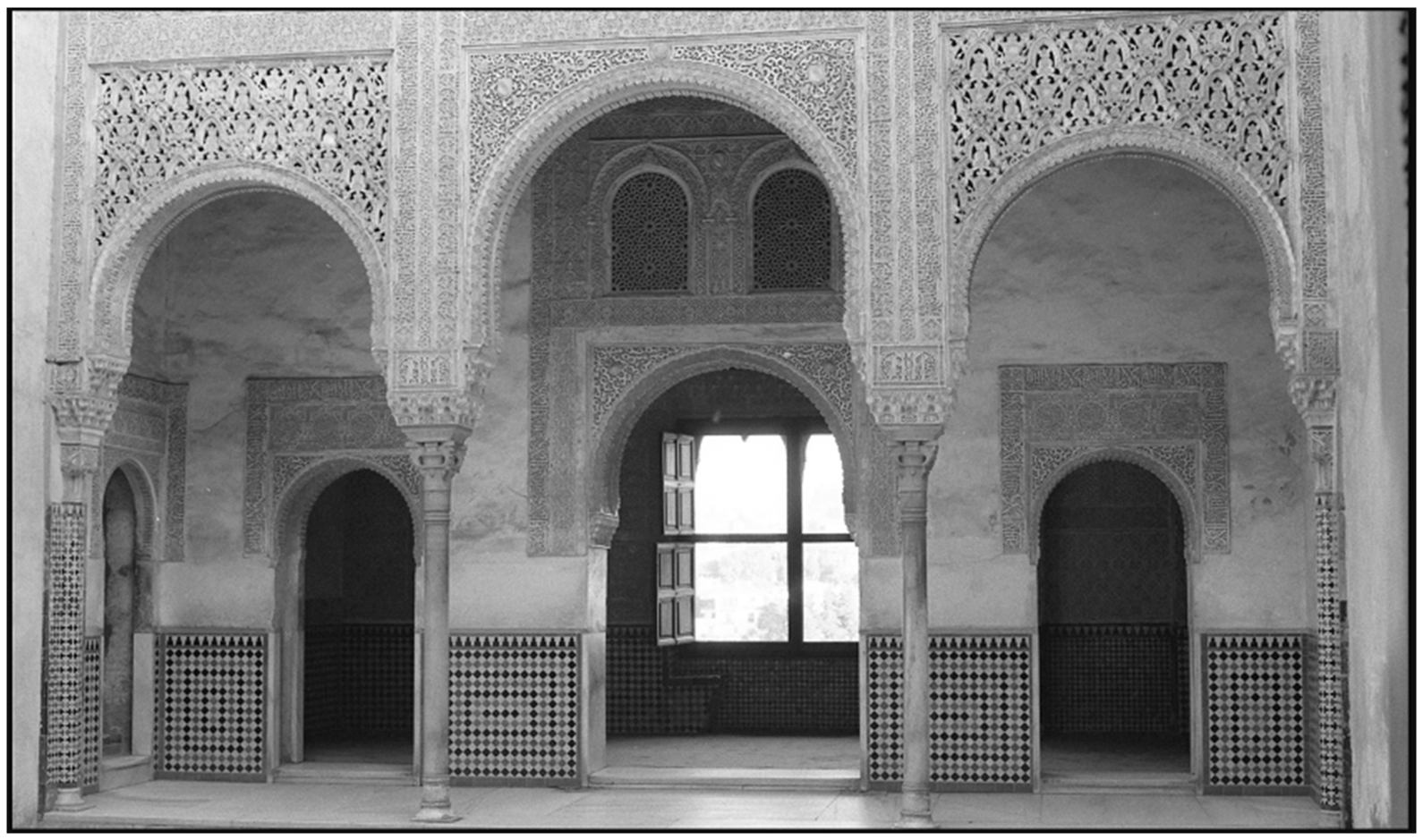

With regard to the transformation that the Cuarto Dorado underwent in the 15th century to adapt the living area for occupation by Empress Isabella of Portugal, Jesús Bermúdez Pareja takes the view that:

“[…] in order to turn this Muslim room into Christian living quarters, the three lower windows in the north wall, in the Muslim style, were converted into a single high central window of Moorish style and decoration. There is hardly any trace left of the Moorish style central window, although some sign of the openings made for the side windows can be seen on the inside of the building, and, with much greater clarity, in the impressions which are still visible on the facade which looks over the neighbouring wooded area. Of the three doors on the south wall, only the central one remains, with its strengthened main entrance gate. The smaller side doors boarded up […] The new plasterwork decoration and the Moorish ceramic dadoes on the walls covered the boarding up of the doors that had been removed, to the present day. It is very possible that the side, plasterwork doorways leading to the outside were partially hidden underneath the smooth plaster and the ceramic dadoes, until the restoration work that was carried out until early this century”.

Meanwhile, Leopoldo Torres Balbás wrote that “the repair of the Cuarto Dorado in the late 15th century must have included the plasterwork of its walls, wainscot and ceiling…”, without making any reference to the ceramic dadoes in the room (

Torres Balbás 1951, p. 202).

Some of the ceramic dadoes that can still be seen inside the Cuarto Dorado, especially on the north wall, may date from the 17th century, as we have previously documented; other parts of this wall are also partly or fully dated from the 19th century.

This idea stems from a reading of the following text by Antonio Orihuela Uzal, regarding the ceramic dado on the facade of the Comares Palace, which occupies the south wall of the Cuarto Dorado Court:

“During summer 1979 [it is clear that this is a mistake and should in fact be 1879], Valeriano Medina Contreras, the highest-ranking master craftsman in the team of restorers, assisted his workers in the replacement of the lower part and the mosaic in the Court of the Mosque (AHA, Leg. 319-5 new). In the photographs taken a few years after the end of the work, it is possible to see that a dado had been added to the lower part of the facade, composed of small square ceramic tiles placed at 45° to the horizontal and topped with a crenellated wainscot, which seems to be the same as the one we see today. We can therefore conclude that at that time tiles were being supplied in the five traditional colours. The design of this dado seems to have been invented by Rafael Contreras, as in previous drawings of the work, such as those published by Lewis in 1835 and Owen Jones, in 1842 (

Fernández Puertas 1980, plates VIII, XIII.a), we can see that there is not the slightest trace remaining”.

Indeed, later photographs of the restoration of the Comares Palace facade show a dado that is similar to the one that we see in the Cuarto Dorado (see

Figure 28 and

Figure 29). As Orihuela argues, this was a dado invented by Contreras for this facade. In our opinion, it might have been inspired by old dadoes that had been conserved in other parts of the Alhambra; for example, in the Comares Baths, or else in the Cuarto Dorado itself. Could it therefore be possible that the dadoes on the north wall of the Cuarto Dorado were either partly or fully the work of Contreras or his predecessors? In this regard, we should consider the words of Manuel Gómez-Moreno González in 1892 on the way that restorers working before Rafael Contreras and his contemporaries operated:

“…in decorative restorations there was a common yet disastrous tendency to attempt to recover the Alcázar’s original splendour, destroying in the process old adornments, whose condition had deteriorated to a greater or lesser extent, in order to replace them with entirely new pieces in such a way as to render the original decoration indistinguishable, and the restorers were very proud when this was achieved; although on occasion, not satisfied with this, they would also seek to alter the past by adding other pieces on the basis of their whim and fantasy (…) naming Mr. Rafael Contreras as Director and Restorer (…). From this time (1847) we may note a greater respect for that which is venerable, although the lightness with which they sometimes proceed is nonetheless regrettable”.

Among these restorers who preceded Rafael Contreras, special mention should be made of his father, José Contreras Osorio, who worked in the Alhambra from 1840 to 1846, much in the way outlined above by Gómez-Moreno. Regarding the reports that were written by José Contreras inasmuch restoration work carried out from 1843 to 1846 in the Comares Court and the Hall of Abencerrajes, Juan Manuel Barrios Rozúa (based on the documents from the Archivo del Patronato de la Alhambra y el Generalife, L-203-2, L-228-31 y L-233-5, and Archivo General del Palacio Real de Madrid, 12014/13), says that although “…they remade many of the plaster and wood adornments (…) their work only halted with the tiles because they could not find anyone who would produce them at a low cost” (

Barrios Rozúa 2011, p. 252) and that “…the restoration of the tile dadoes, which they called ‘varnished slabs’, was put out to tender, although the money they offered was half what was needed, according to the estimates of the bidders, and thus the tender received no response”. These reports made it clear that this was the intention “although [these tiles] were never purchased or installed”. José Contreras also proposed the repositioning of tiles in the Court of the Lions (Patio de los Leones), the Kings’ Room and the Hall of the Two Sisters (Sala de los Reyes and Sala de Dos Hermanas) (

Barrios Rozúa 2016, pp. 75, 92, 97, and notes 170 y 218).

Having said this, we take the view that some of the ceramic dadoes on the north wall of the Cuarto Dorado may have been replaced during the time of Rafael Contreras (1847–1890) and not before, despite the fact that in 1878 Contreras made no reference to the dadoes in this part: “…passing between the two columns I found a small room that had been rebuilt after the

Reconquista, as could be seen from its ceiling, in the centre of which there was a window of Gothic design…” (

Contreras 1878, p. 300). In 1890, Francisco de Paula Valladar reported that restoration work had already been undertaken in the Cuarto Dorado: “The room was restored at the time of the

Reconquista with the work showing many signs of ignorance. The whole facade was whitewashed and it must have been beautiful, to judge by the interesting restoration work that had been done there” (

Valladar 1890, p. 51).

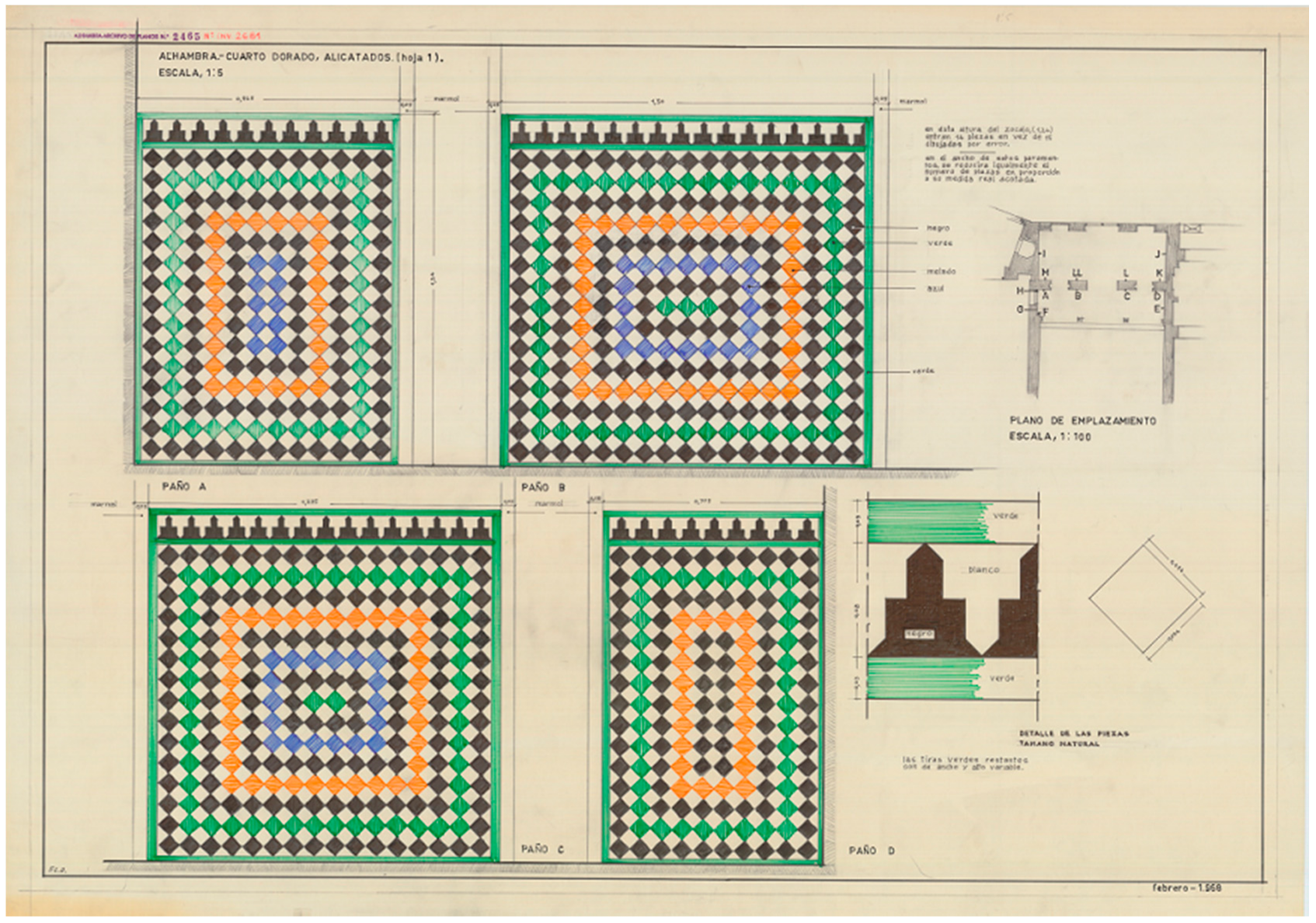

The Cuarto Dorado therefore contains fragments of dadoes from the 17th and 18th centuries, and even some from the 19

th century, all of which feature the same design. We can also include those added by Prieto-Moreno from 1969 to 1971 in a similar line to the foregoing, echoing the spirit of the Minutes of Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife (10 November 1967), in which “it is agreed to complete the

alicatado dado and maintain the

Mudéjar spirit of the interior” (

Fernández Puertas 1980, p. 41).

Pieces of

alicatado are not only replaced in the main room but also in the portico. In the 20th century, the portico before the Cuarto Dorado underwent a series of changes, which should be highlighted here:

—In 1965 the two 16th century arches resting on pillars which partly obscured the Nasrid portico were removed (

Bermúdez Pareja 1965, p. 99), pursuant to an agreement in the Minutes of Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife (30 June 1964) (

Fernández Puertas 1980, p. 41) under the supervision of Prieto-Moreno (

Romero Gallardo 2014, p. 90). At the same time, the original door connecting the portico to the small court, which was original part of Mexuar, was opened up.

—From 17 April to 15 May 1967 the side arch-doors between the portico and the Cuarto Dorado were restored and opened up by Francisco Prieto-Moreno.

With the exception of James Cavanah Murphy’s engraving, the iconography of the 19th century (and until 1967) shows a portico where the side arches leading onto the Cuarto Dorado appear as boarded up, possibly from the time of the Catholic Monarchs, as Bermúdez believes, in order to adapt the hall for use as living quarters.

We do not know whether or not this portico featured ceramic dadoes in Nasrid times, and if they did, what they looked like. Neither do we know if a new one was adapted to a Christian aesthetic or replacing an earlier Nasrid piece that might have been there. We only have information in this regard from the 19th century onward as there are two paintings, one that we have already mentioned by M. Medina and another entitled

El Tribunal de la Alhambra (“The Court of The Alambra”) by Mariano Fortuny, dated 1871 and also published by Bermúdez Pareja (

Bermúdez Pareja 1965, p. 105, Plate XIII), in which we can see ceramic dadoes on the portico. The first of these shows a dado similar to the ones that we see today on the north portico of the Comares Palace and Baths, while the second depicts a more complex

alicatado of wheel motifs of different sizes that are very similar to those on the jambs of the side

alcoba in the Hall of the Two Sisters. In both paintings, the most easterly arch providing access to the Cuarto Dorado is shown as open, or featuring a door. We are of the belief that this is due to a fantasy in the minds of the two painters who have used dado designs that they may have seen elsewhere in the Alhambra, as they do not appear in contemporary photographs of the portico. However, this portico does feature a ceramic element, which can be seen in both the aforementioned paintings and in photographs taken prior to the removal in 1965 of the arches that were added in the 16th century (see

Figure 30). Here, we are referring to the remains of the

alicatado panel that extends around the top of the shaft of the engaged column on the western edge, as well as running from left to right on its facing. It is formed by three-pointed

alicatados in various colours (black, white, honey-coloured, green and blue), framed by green

cintas and topped with a black crenellated wainscot. These three-pointed

alicatados can also be seen in the Comares Baths and on the crenellation on the arch that leads from the Hall of the Boat to the Comares Hall, among other examples.

Records of the conservation work carried out during Modesto Cendoya’s time in the Royal Household state that in September 1911 “the walls of the Cuarto Dorado’s gallery were shored up and the engaged columns of tiles found were repaired” (

Álvarez Lopera 1977, p. 144). This repair work may have included the total reintegration of ceramic pieces that are missing from the shafts of these engaged columns, or at least on the column on the extreme western side of the portico, as in December 1966, all that remains of the shaft of the engaged column is the

alicatado at the top (see

Figure 31). We can currently see how the

alicatado has been completely reintegrated into the shafts of the two engaged columns.

The rest of the ceramic dadoes in the portico were added by Prieto-Moreno as a result of the agreement to complete the

alicatado on the facade, as outlined in the Minutes of Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife (10 November 1967), reproducing the same sections as those that are found in the Cuarto Dorado, such as the dado on the facade of the Comares Palace (see

Figure 32 and

Figure 33).

We can therefore see that, over time, from Rafael Contreras to Francisco Prieto-Moreno and in various restorations and replacements of ceramic tile mosaics in the areas we have mentioned, the same alicatado design has been used, based on the remains of the “Moorish ceramic dadoes”, which Bermúdez refers to in the Cuarto Dorado or that were perhaps copied from elsewhere. What is evident is that the result has been the creation in the hall, the portico and the facade of fictitious architectural ceramics in which symmetry and a harmonious design have prevailed.

There can be no doubt as to the importance of architectural ceramics to the Nasrid Alhambra. Proof of this can be seen in the numerous pieces in the Alhambra Museum’s collection, as well as other in situ examples. However, what we can see today of the history of the palatine city is like the page of a vast manuscript which brings together eras, repairs, adaptations, major restorations and inventions. Ascertaining from what period each element that we see today dates is a task in which researchers and specialists need to apply stringent standards and which requires of study and an in-depth knowledge of numerous sources, as we have outlined in this paper, from archive documentation covering various periods to a wealth of photographs, drawings, and engravings.

This does not prevent us from recognising the value of the alicatado dado replacement work and accepting that not all we see is from the Nasrid era or that it does not correspond to what could be seen before. On the contrary, all of this highlights the complexity and historical treasures of a monument that the country has always sought to conserve. There is a huge task still facing us. Readers of this paper will have appreciated the great difficulties in studying a space that is nonetheless not so large, such as the Cuarto Dorado. Imagine this applied to the whole of the palatine city. Our duty is to not falsify or simplify reality but rather to depict the Alhambra in its whole historical dimension.