Waves to Waveforms: Performing the Thresholds of Sensors and Sense-Making in the Anthropocene

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Technology

2.1. Location

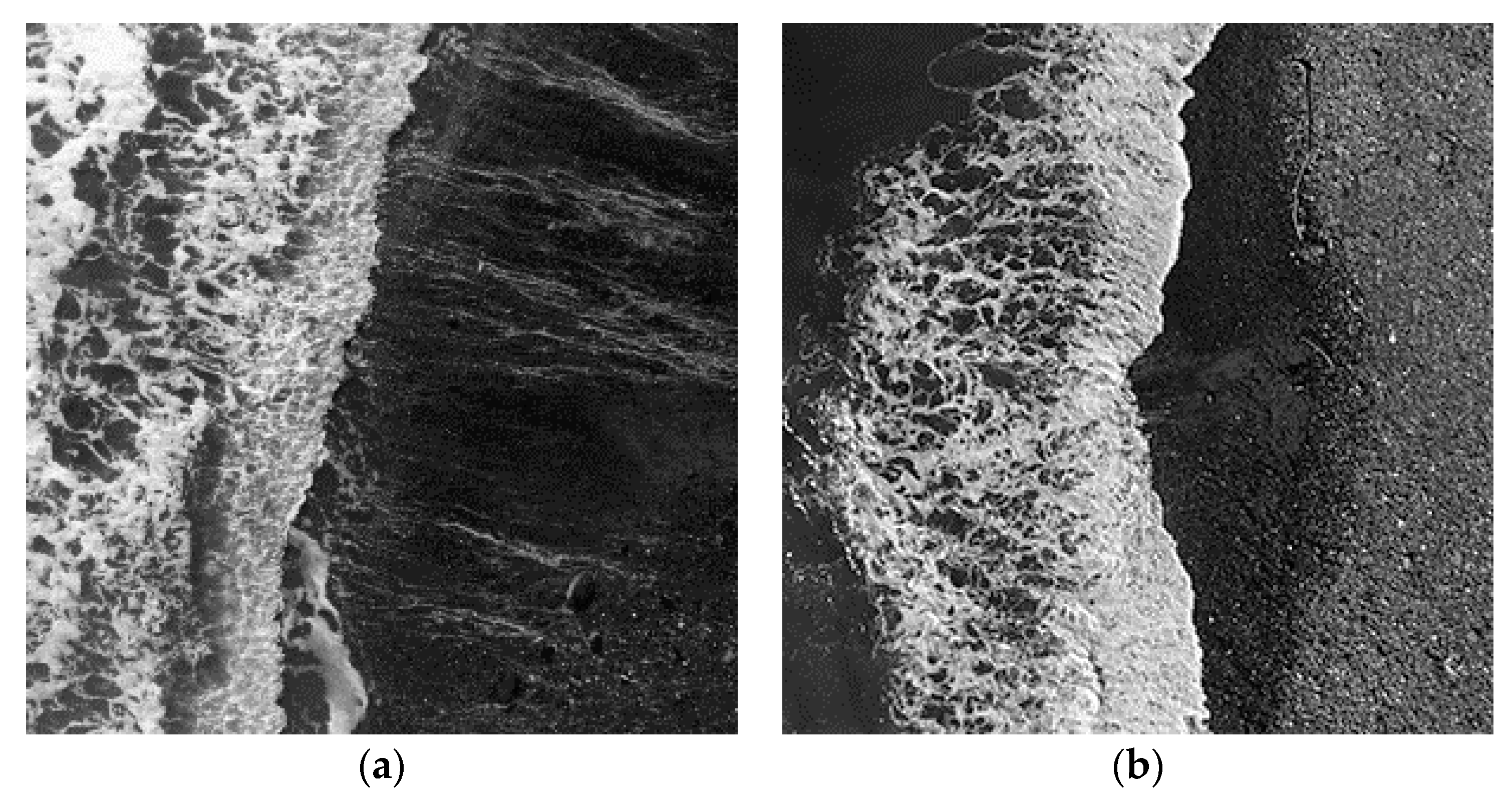

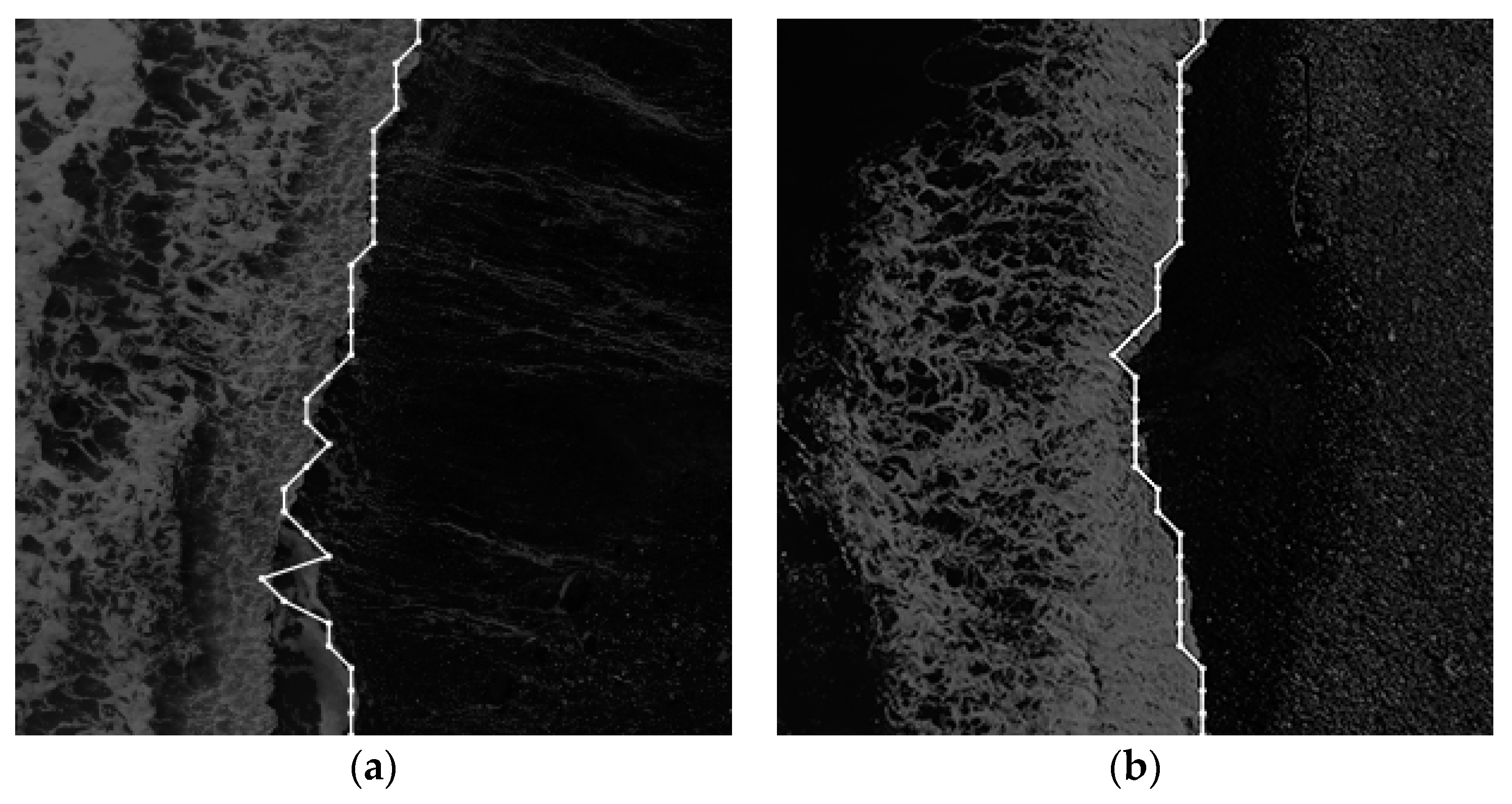

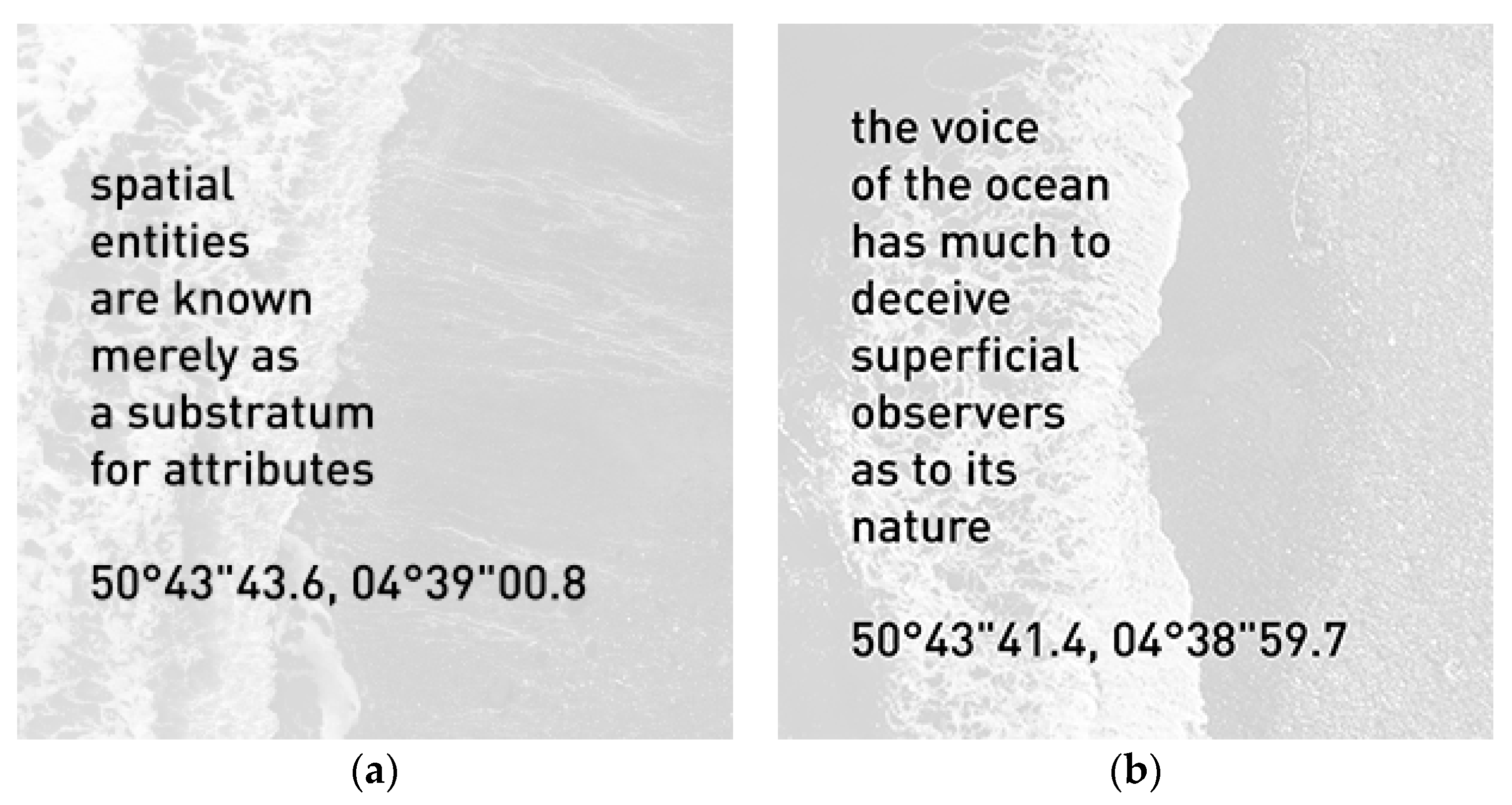

2.2. Photography

2.3. Text Generation

3. Sensing the Anthropocene

[I]deas of the Anthropocene have been shaped by a technospheric net of innumerable satellites, cameras, and detectors, resulting in an aesthetic regime composed of data that has been used to narrate profound changes to climate, landscape, and biodiversity over the past 400 years.

If quantification, abstraction, and the logic of evidential traces have been the means by which we’ve largely come to recognize our purported Anthropocene condition, then the question becomes how we might proceed so that our “sensing” is less “remote,” and forge aesthetics that incorporate not only the representational, but also the lived and affective experiences of various anthropo-scenes.

Sunlight is behaving differently in this part of the world as the warming Arctic air causes temperature inversions and throws the setting sun off kilter. Light is bending and deceiving eyes that have tracked the position of the sun for generations, using it as an index of place and a marker for direction. The crystalline structures of ice and snow are twisting and morphing, producing a new optical regime borne out of climate change and indigenous observations.

The sense of closed global space that had disturbed the strategic thinking of so many Westerners at the beginning of the twentieth century found expression in a global geopolitics of competitive imperial struggle as the frontiers of Western empires converged at the ends of the earth. Mapping the globes climates and physiography into “natural” regions could naturalize patterns of control and strategy among the imperial powers. Geopolitics suggested that unalterable geographic “realities”—the distribution of lands and seas, of landforms, natural resources, or “races”—had to be exploited if a state was to survive, compete, and prosper.

4. Airborne Sensing

4.1. Aerial Activism

PigeonBlog thus staged an act of speculative sensing, one that entered into a collaboration with nonhuman partners so as to inspire new ways of seeing and thinking amongst its human observers. On this point, Haraway (2016, pp. 23–24) reads PigeonBlog as a striking instance of the exploratory kinships that are of particular import for life in the Cthulucene: ‘Perhaps it is precisely in the realm of play, outside the dictates of teleology, settled categories, and function, that serious worldliness and recuperation become possible’.With homing pigeons serving as the “reporters” of current air pollution levels, Pigeonblog attempted to create a spectacle provocative enough to spark people’s imagination and interests in the types of action that could be taken in order to reverse this situation. Activists’ pursuits can often have a normalizing effect rather than one that inspires social change. Circulating information on “how bad things are” can easily be lost in our daily information overload. It seems that artists are in the perfect position to invent new ways in which information is conveyed and participation inspired. The pigeons became my communicative objects in this project and “collaborators” in the co-production of knowledge.

4.2. Drone Art

We find ourselves on the side of the drone and its pilot, desperate to understand this torrent of collected images, the better to control and dominate—and, we realize, destroy—what and who lies below. The unmediated flow of visual and spatial data that passes through drone eyes collapses the distance between device and operator, between American air base and Middle Eastern valley, into a single moment of seeing.

Information is a property of people and communities and discussions, and actual work, it’s not something you can just take a picture of and steal. But that was the paradigm, and it actually remains the prevailing paradigm, that information is property, that it can be stolen with cameras. So flying the BIT Plane through these no-camera zones was part of the exploration of what you could actually just see. What could you actually see? What information could you take from the plane? Of course, the answer is not much (as contemporary drones have so aptly demonstrated)—lots of images but not much actual trustable information.

5. Vision Machines

5.1. Signal Processing

The rays received from the external world allowed for the precise algebraic processing of successive waveforms, which visualised objects that had previously been imperceptible to the naked eye. […] Photography and television were touted as technologies that faithfully recorded reality. Radar, however, broke the apparent unity of reality and its representation apart, because it programmatically manipulated the image. The pictures were not a faithful record of the rays received; they merely represented the initial data for filtering, that is, the algebraic calculation of the image. Slowly but surely, algorithms were beginning to determine what was considered as real.

Darling SweetheartYou are my avid fellow feeling. My affection curiously clings to your passionate wish. My liking yearns for your heart. You are my wistful sympathy: my tender liking.Yours beautifully,M.U.C.

5.2. Experimental Aesthetics

6. Waves to Waveforms

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aerocene. 2018. Available online: http://aerocene.org/ (accessed on 20 October 2018).

- All-Party Parliamentary Group on Drones. 2018. The UK’s Use of Armed Drones: Working with Partners; London: All-Party Parliamentary Group on Drones. Available online: http://appgdrones.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/INH_PG_Drones_AllInOne_v25.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2018).

- Bolen, Jeremy, Emily Eliza Scott, and Andrew Yang. 2016. Sensing the Insensible: Aesthetics in/and/through the Anthropocene. Anthropocene Curriculum. Available online: http://www.anthropocene-curriculum.org/pages/root/campus-2016/sensing-the-insensible-aesthetics-in-the-anthropocene (accessed on 30 August 2018).

- Buelens, Geert. 2015. Everything to Nothing: The Poetry of the Great War, Revolution and the Transformation of Europe. Translated by David McKay. London: Verso, ISBN 9781784781491. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Richard. 2018. Waveform. Available online: http://richardacarter.com/waveform/ (accessed on 29 October 2018).

- Cosgrove, Dennis. 2001. Apollo’s Eye: A Cartographic Genealogy of the Earth in the Western Imagination. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0801864917. [Google Scholar]

- Crutzen, Paul, and Eugene Stoermer. 2000. The “Anthropocene”. IGBP Global Change 41: 17–8. [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa, Beatriz. 2017. Interspecies Coproduction in the Pursuit of Resistant Action. Surveillance and Art. Available online: https://sites.tufts.edu/surveillanceandart/files/2017/11/pigeonstatement.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2018).

- Davis, Heather, and Etienne Turpin, eds. 2015. Art in the Anthropocene. London: Open Humanities Press, ISBN 9781785420054. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, Donna. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press, ISBN 9780822362241. [Google Scholar]

- Jeremijenko, Natalie. 2013. Interview: Natalie Jeremijenko. Center for the Study of the Drone. Available online: http://dronecenter.bard.edu/interview-natalie-jeremijenko/ (accessed on 30 August 2018).

- Link, David. 2016. Archaeology of Algorithmic Artefacts. Minneapolis: Univocal Publishing, ISBN 9781945414046. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Jason, ed. 2016. Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism. Oakland: PM Press, ISBN 9781629631486. [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Hansen, Finn. 2016. Sensing. Anthropocene Curriculum. Available online: https://www.anthropocene-curriculum.org/pages/root/resources/sensing/ (accessed on 30 August 2018).

- Schuppli, Susan. 2014. Can the Sun Lie? In Forensis: The Architecture of Public Truth. Edited by Eyal Weizman and Anselm Franke. Berlin: Sternberg Press, pp. 54–64. ISBN 9783956790119. [Google Scholar]

- Starosielski, Nicole. 2015. The Undersea Network. Durham: Duke University Press, ISBN 9780822357407. [Google Scholar]

- Strachey, Christopher. 1954. The “Thinking” Machine. Encounter 13: 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenburg, Colin. 2016. Drone Art. Dissent 63: 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virilio, Paul. 1994. The Vision Machine. London: British Film Institute, ISBN 0253325749. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carter, R. Waves to Waveforms: Performing the Thresholds of Sensors and Sense-Making in the Anthropocene. Arts 2018, 7, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040070

Carter R. Waves to Waveforms: Performing the Thresholds of Sensors and Sense-Making in the Anthropocene. Arts. 2018; 7(4):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040070

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarter, Richard. 2018. "Waves to Waveforms: Performing the Thresholds of Sensors and Sense-Making in the Anthropocene" Arts 7, no. 4: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040070

APA StyleCarter, R. (2018). Waves to Waveforms: Performing the Thresholds of Sensors and Sense-Making in the Anthropocene. Arts, 7(4), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040070