Abstract

Walter Benjamin’s 1936 essay, “The Storyteller” (2006) defines storytelling as a mode of communication that is defined in part by its ability to offer listeners “counsel”, or meaningful wisdom or advice. This article considers the earmarks of storytelling as defined by Benjamin and by contemporary writer Larry McMurtry and argues this type of narrative experience can be offered via interactive media and, in particular, video games. After identifying the key characteristics of storytelling as set forth by Benjamin, the article proposes and advocates for a set of key characteristics of video game storytelling. In doing so, the article argues that effective narrative immersion can offer what Benjamin calls counsel, or wisdom, by refusing to provide pat answers or neat conclusions and suggests these as strategies for game writers and developers who want to provide educational or transformative experiences. Throughout, the article invokes historic and contemporary video games, asking for careful consideration of the ways in which games focused on sometimes highly personal narratives rely on storytelling techniques that instruct and transform and that can provide a rich framework for the design and writing of narrative games.

1. Introduction

In every case the storyteller is a man who has counsel for his readers. But if today ‘having counsel’ is beginning to have an old-fashioned ring to it is because the communicability of experience is decreasing.Benjamin (2006)

In Larry McMurtry’s quasi-memoir Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen, the iconic Texas writer ruminates on the Texas he has lived and the one he has recounted for his readers, a landscape that is at turns both intoxicating and brutal. The book begins with McMurtry’s own reading of Walter Benjamin’s “The Storyteller” in his hometown Dairy Queen in Archer City, Texas (McMurtry 1999). In the essay, quoted above, Benjamin mourns the decline of storytelling in the period leading up to the first World War; McMurtry maps a similar fading during his own lifetime as Texas has shifted from a state of small towns to one of bustling global cities. Both Benjamin’s essay and McMurtry’s book are driven in part by a sense of nostalgia, the belief that something has been lost, which is unlikely to be recovered. However, in claiming personal experience of Benjamin-style storytelling, McMurtry is also offering a corrective: After all, Benjamin’s piece first appeared in print in 1936, the year of McMurtry’s birth, which means that the decline McMurtry notes comes decades after the one that Benjamin laments.

I begin with Benjamin and McMurtry not to take issue with either of their works, but rather to introduce a broader argument about the power and potential of a certain type of storytelling. This argument emanates from Benjamin’s “The Storyteller”, but draws, too, on McMurtry’s relatively modern invocation. After all, if McMurtry can find evidence of this endangered, yet deeply satisfying style of storytelling in the late 1960s, so might we find more recent evidence in our own places and practices. In this article, I consider the earmarks of storytelling as defined by Benjamin and McMurtry and argue this type of narrative experience can be offered via interactive media and, in particular, video games. In doing so, I ultimately suggest that effective narrative immersion can offer what Benjamin calls counsel, or wisdom, by refusing to provide pat answers or neat conclusions. This type of storytelling is not, as I frame it, dependent on the technological wizardry that drives many games, but rather on a careful engagement of the audience through the deliberate construction of meaningful narrative. Its ultimate goal is a kind of transformative experience, one by which profound types of experiences and knowledge—counsel—are imparted to audience members.

I turn now to a consideration of Benjamin’s definition of storytelling in a wider context of play theory and narrative theory (Callois 2006; Huizinga 1971; Juul 2005; Ryan 2001). Play, as I invoke it here, occupies an uneasy space between the real and the fictional and is deeply enmeshed with narrative strategies. Using this context, I consider the work of recent independent games. The games selected here tend to deal with emotional and/or highly personal experience as a primary concern. For example, in Depression Quest (Independent, 2013), the player takes the role of a depressed young adult, attempting to navigate a life in which choices are steadily eliminated by worsening symptoms. Through this, the game attempts to model the experience of depression for players who may not have the kind of first-hand experience the game draws from. Richard Hofmeier’s Cart Life (Independent, 2011) uses time and resource management mechanics to force players to confront the difficulty and stress of operating a small food or coffee cart. These games, and others like them, aspire to convey or form shared experiences and produce deep emotional responses; they move by providing familiarity with the stories and experiences of other. In this, they resonate with Walter Benjamin’s longing for storytelling as a means of conveying what he calls counsel or wisdom. I focus on these kinds of games because they are distinctly invested in the acquisition and circulation of experiential knowledge, a type of knowledge that seems particularly difficult to quantify or to convey through designed experiences. However, Benjamin holds, and McMurtry reiterates, that proper storytelling does just this; I forward that well-designed narrative games, games invested in personal stories (or at least, stories that seem personal) and experiential knowledge, too, can achieve this.

In this article, I outline a rubric for crafting successful storytelling games broadly defined; because storytelling structures are used across game forms and genres, I draw examples from a diversity of styles of game design and production. Utilizing methods proposed by theorists including Stuart Hall, Antonio Gramsci, Chantal Mouffe, and other experts in articulation theory, first, I review Benjamin’s definition of storytelling and show examples of how his key characteristics are evident in narrative media forms; then, I turn to the use of narrative in games before discussing how Benjamin’s style of storytelling might be evidenced in games and why this might be useful (Grossberg 1986; Mouffe 1979). Ultimately, I propose a list of key characteristics for storytelling games that could be used by developers, arguing that this approach could be used as a framework for effective transformative games.

2. Storytelling Things

The value of information does not survive the moment in which it was new. It lives only at that moment; it has to surrender to it completely and explain itself to it without losing any time. A story is different. It does not expend itself.Benjamin (2006)

The storyteller, as Benjamin defines him, is part historian, part performer, part fabulist. Storytellers pass on local scandals and lore, but they do not provide information; rather, they transform facts into meaningful, engaging narratives. To tell a story, then, is not merely to tell what happened but to offer a means of making sense of it. Stories, for Benjamin, demand interpretation while information refuses it. Some key characteristics of a storyteller, as carefully defined by Benjamin, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Benjamin’s key characteristics of storytellers.

What becomes apparent in listing these characteristics is that storytelling is a craft, a creative art, and an idiosyncratic instructional strategy; we are entertained by storytellers, we admire their artistry, but we also learn from them and from the lived experiences they convey. In this way, the most skillful storytellers are not unlike the most skilled game designers, and there is a meaningful overlap between storytelling and play. Storytelling, as Benjamin describes it, is fanciful in that it is less interested in factual information and explanations than it is in the imparting of wisdom, morals, and deeper truths; in this way, it is a bit like the documentaries of filmmaker Werner Herzog, who introduces visually compelling and fabricated metaphor to his ostensible nonfiction, as in Little Dieter Needs to Fly, where he shows the titular character locking and unlocking doors to emphasize the lingering effects of his previous imprisonment. Storytelling is also fanciful because it is, in most cases, both improvisational and playful. As envisioned by both Benjamin and McMurtry, storytelling is a kind of performance, but it is also a kind of play, not in the sense of a theatrical performance, although it can be this, but in the sense of the types of fiction-driven games described by Roger Callois. There are games, according to Callois, “which presuppose free improvisation, and the chief attraction of which lies in the pleasure of playing a role, of acting as if one were someone or something else, a machine for example” (Callois 2006; Juul 2005). In these, the fiction, the acting as if, takes the role of a rule set. Storytelling has its own rules and principles. Benjamin identifies some of them, but I would highlight that the guidelines Benjamin lays out require their own acting as if. Those listening to a storyteller often accept that the tale they are told may be nonfactual even as it is true; these inaccuracies are accepted in the service of the broader narrative point. Further, in engaging with the storyteller, the audience necessarily enters a state of suspended disbelief, which is a prerequisite of immersion and of truly experiencing the work of a storyteller.

The storyteller may break this suspension through ineptitude or they may subtly adjust their tale to lure the audience back. Storytellers may alter their performance to best engage their current audience or insert humor as a hook. They may draw on their knowledge of audience members to tease and cajole. These interactions with the audience provide a type of multisensory experience and heighten immersion; audience members don’t just listen to a storyteller, they also watch them, and may find themselves engaged in prompted callbacks.

The storyteller is not a lecturer or a finger-wagger; they provide a framework in which people may learn for themselves. The storyteller draws audiences into moral instruction. Stories are often parables or warnings, imparting fairytale knowledge or practical reminders. Many of us know these lessons from fairy tales—it is easy, after all, to get lost or injured in the woods alone after dark, and such folly can end in humiliation as easily as physical harm—or from fables—the tortoise’s steady pace is more successful if less glamorous than the rabbit’s. These lessons are old, sometimes ancient, but they are easier to learn with a thrill or a laugh than they are through nagging reminders. In providing a fanciful framework for imparting necessary knowledge, too, the storyteller is playful. Play is well documented as a means through which children develop and learn (Broadhead et al. 2010; Cook 2000; Elkind 2007; Singer et al. 2006). In addition, it is also key for adults’ well-being and satisfaction (Proyer 2013; Magnuson and Barnett 2013). Play is not only an action, but an approach to the world, a means of interacting.

Fables, and storytelling too, as described by Benjamin, provide a means of inviting audience members to participate in their own education, since they require interpretation and application. Research suggests that storytelling can play a key role in education in a diversity of subjects (Brown 1997; Rodgers 1980; Short and Ketchen 2005; Whyte 1995). Again, these types of stories are rarely explained directly, but rather impart knowledge indirectly by providing the audience with a story to mull over and make sense of.

Storytelling is a kind of fiction game as described by Callois, not only because a fiction is relayed, but also because the audience is asked if not to act as if, at least to imagine as if. Imagine as if the story is factual or real even when it defies other known information; imagine as if you are one of the characters in the story. What might you have done differently? How will you, in future, avoid the fate of some unfortunate? I reference Callois here in part to move this discussion towards games, but also because Callois’ elastic definition of games and of play allows room for considering as playful many types of social interactions and narrative forms. As Johan Huizinga implies and Callois makes explicit, rules generate their own kinds of fictions as well. These rule-based fictions are, in the words of Jesper Juul, half-real in that their rules are treated as real even as they are effectively laid over a fabricated reality (Juul 2005).

The storyteller Benjamin describes is one who, like the designers of the games Juul references, creates a half-real place, one governed by real rules even as it creates a fictionalized reality that can deliver greater truths. While expressing his distaste for novels as lacking in counsel, Benjamin allows that stories of the kind propagated by storytellers can be written down; in this, he suggests that storytelling can be mediated and that, in the absence of a human storyteller, the story can be carried forward by other recorded means. There is a danger in this, however; while some such efforts retain the story’s punch and purpose, others effectively sanitize the story, closing down its possibilities and robbing it of counsel. In transitioning to a consideration of mediated stories, I would like to turn to the idea of storytelling things, or, more specifically, storytelling games.

3. Storytelling Games

The more self-forgetful the listener is, the more deeply is what he listens to impressed upon his memory.Benjamin (2006)

The audience member’s willingness to suspend their sense of self and their own sense of the world makes it easier for them to remember the lessons imparted in the story and to place themselves in the narrative. This is a fundamental requirement for immersion; it is also a reminder that audience members are often making choices of their own—they are choosing to go along with the story, to forget themselves. The person listening to a Benjamin-style storyteller is an active participant. Researchers like Zunshine (2006) and Vermeule (2009) have shown the similarities in how we process and interpret real and fictional events; we become immersed in stories much as we become immersed in our own daily lives. This type of immersion, this possibility of forgetting the self, of finding ourselves in the experiences of others, is why games are so well suited to storytelling. It is also why one of the key questions raised in the arena of serious and learning games over the past few decades has been the question of whether or not games can teach, and if so, what they can teach. James Paul Gee, for example, has called games “learning machines”, and numerous other scholars have argued for the application of games as educational tools (Gee 2003; Mayo 2007; McGonigal 2011; Prensky 2006; Rieber 1996; Shaffer et al. 2005). More recent work, often undertaken by scholars working in learning science, has shifted from the question of whether games can be educational and moved into more specific questions about efficacy and design (Schrier 2016; Trujillo et al. 2016).

Callois (2006) argues that play requires consent. It is an opting in; forced play ceases to be play and becomes something else. While learning games are often, to their detriment, made compulsory, as in the case of games used to train employees, the appeal and true potential of learning games and most serious games lies in the possibility that players will choose them of their own accord (deWinter et al. 2014). In this, too, they echo Benjamin’s storytelling. After all, children submit to lectures, but beg to hear stories. Stories offer an immersive experience, while often lectures provide only a pedantic one. Immersion and voluntary participation are not explicated as such in either Benjamin’s original essay or McMurtry’s later revisiting of it, but they are implied in the key characteristics of a storyteller that Benjamin identifies. The storyteller is a performer who draws the audience in.

In this way, Benjamin’s proposed storyteller is again somewhat like a gamemaster. His storytelling draws people in, immersing them in the world and lessons of the tale to be told. As Marie-Laure Ryan points out, advocates of virtual reality frequently tout the possibilities for immersion; however, peculiarly, in doing so they frequently summon the metaphor of a literary text (Ryan 2001). To be immersed in a virtual reality is similar to being immersed in a good book. The world presented is not necessarily real, but real enough. Similarly, the world of a story is real enough, a frame in which we are willing to act as if. Ryan ultimately argues that narrative is itself a kind of virtual reality. So, too, are stories. But, in all cases, for these virtual realities to be effective, they have to provide an experience of immersion. There are well-known enemies to immersion—games that are too easy or too difficult readily lose players who grow bored or frustrated and many games require strenuous effort from players wishing to occupy the fictional world (Linderoth 2012). Ultimately, I suggest that Benjamin’s storytelling model offers a potentially powerful model for the development of effective storytelling games that offer players not just information, but counsel—and, because of this, Benjamin’s classic essay is a useful resource for game designers and writers who strive to produce meaningful experiences in new media.

4. Putting Benjamin on Screen

It has seldom been realized that the listener’s naive relationship to the storyteller is controlled by his interest in retaining what he is told.Benjamin (2006)

In this section, I turn to an examination of how principles from Benjamin’s essay can be useful if adapted and applied by writers and developers to produce meaningful narrative games; to do this, I continue to draw on research on the educational uses of games and on strategies for providing moral and experiential education. While some of these strategies are designed for the classroom, I suggest they, like Benjamin’s fundamentals, are good models for what might be possible in thoughtfully designed narrative games. Both advocates and critics of video games often assume that games offer a richer, more powerful, and more seductive form of storytelling. This can be seen as a danger, as in efforts to regulate violent video games, or as an opportunity, as in the advocacy for the adoption of educational games. This shared assumption is backed up by some research, although the range of games that serve as effective learning tools is much narrower than the range of games that are touted as effective learning tools. This may owe in part to the conditions under which these games are deployed. The success of the early computer game The Oregon Trail (Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium, 1974; see Figure 1) as both a widely circulated educational tool and popular obsession provides a tantalizing example of what might be possible. The game ultimately sold some 65 million copies and taught, at the very least, that those westbound along the original Oregon Trail of westward expansion faced significant hardships (Campbell 2013b). However, while games like The Oregon Trail offer skills and, to some extent, knowledge, I would argue that they fail to offer counsel. However, this does not mean that games cannot do so, only that these particular games do not. Research on curriculum development for English language arts classes suggests the possibility. Ryan et al. (2002) suggest thoughtful curriculum can provide teachers and students with opportunities to not only cover the required subjects, but to also provide character education and reflection on moral values; Mantle-Bromley and Foster (2005) argue that language arts teachers are uniquely positioned to provide education on matters of democracy and social justice because of the importance of literacy and storytelling in building an understanding of the broader world.

Figure 1.

This screen capture from The Oregon Trail shows the game’s simple interface.

One of the promises of effective game design has been the idea that games can provide experiential knowledge; this echoes Benjamin’s assertion that true storytellers draw on the well of experience. The use of simulators for training in fields like flight and medicine has proven effective because they engage students in an experience that closely mirrors real surgical or flight practices while offering additional learning opportunities (Dennis and Harris 1998; Hays et al. 1992; Issenberg et al. 1999; Issenberg et al. 2005). Further, students in these areas are actively invested in learning the material; someone who has enrolled in flight school, for example, clearly wants to learn to fly a plane and so is more likely to retain information from a flight simulation than someone who has not demonstrated such interest. The Oregon Trail is a kind of simulator; you, too, can die of dysentery and hunt squirrels in a pixilated wild west. In this, the game teaches the dangers of disease and difficulties of resource management that plagued pioneers. This is a lesson of a kind. Typing games and the numerous games that quiz children on times tables and subtraction problems are also offering lessons, even as many function as glorified flashcards intercut with games.

However, the most effective games are often those built around rich stories, and educational research backs up Benjamin’s assertion that storytelling is an effective pedagogical tool. This is no surprise: Studies suggest, for example, that readers of narrative fiction and viewers of television of drama are more empathetic (Black and Barnes 2015). Problem solving is also key to mediated learning experiences. In one study, Bransford et al. (1989) note that the most effective efforts to encourage learners to access relevant knowledge involved “problem-oriented acquisition experiences”. These processes presented students with problems to solve rather than lists of facts, what Benjamin might have dismissed as information. The students who solved problems proved better at accessing and applying relevant information. Games, both those that are deliberately educational and those that exist for reasons more of entertainment or art, can be an excellent medium for providing problems to solve. Game mechanics like resource management, trading, role playing, territorial acquisition, and others can all offer compelling problems for players to tackle. What players can gain from solving these types of problems varies widely; most games aspire to at least provide some brief amusement, but others can immerse players in long-running campaigns or rich storyworlds (Long 2016). I would argue that this problem-solving function is a key component both for Benjamin’s idealized storyteller—who offers truths without explanation and avoids dispensing information—and for effective games.

Games invested in biographical, historical, or sociological events can present particularly nettlesome problems. The pen-and-paper role-playing game Dog Eat Dog (Liwanag Press, 2013) pits the majority of players against a single player as they are cast respectively as the colonized population and colonizing force. In Papers, Please (3309 LLC, 2013), the player works as an immigration officer who must decide which immigrants to admit and deny. Reigns: Her Majesty explicitly grapples with the extent to which powerful women are often seen as wives more than leaders and, therefore, have to wield power quite differently (Devolver Digital, 2017). Games like these model complex cultural and political problems with a profound human toll. The player faced with addressing these is asked to consider not only their complexity, but their emotional weight. The play of these games can be deeply uncomfortable—in Dog Eat Dog one of the players’ first tasks is to identify the wealthiest player and cast him as the colonizer—but they also engage players in the workings of a fictionalized representation of a difficult reality while frequently refusing to tell players what to make of those difficulties. In short, they demand that players solve problems, they provide experiential knowledge and, at least potentially, counsel, about complicated social and cultural issues even while engaging and entertaining players.

Benjamin’s evocation of storytelling suggests that storytellers can do much the same, and this is why “The Storyteller” can be seen as a useful reference and model for writers and developers interested in the types of counsel, of wisdom, of moral education that games might be able to offer, whether explicitly framed as educational games or not. Benjamin’s characteristics of a storyteller can be adapted to describe the characteristics of a storytelling game. In Table 2, I propose a list of key characteristics of effective storytelling games.

Table 2.

A possible adaptation of Benjamin’s storytelling characteristics for the development of immersive game narratives.

These characteristics allow for a broad range of idiosyncratic approaches, but they emphasize opportunities for self-reflection and exploration. These games are often lessons without answers. They make use of the affordances of interactive media while drawing on the best of older traditions and strive to provide experiential knowledge often necessary for cultivating empathy and understanding. There is a subtlety both to Benjamin-style storytelling and to the best of empathy games. They may offer multiple answers or no answers at all, leaving the solutions open to the player. A number of recent games at least aspire to offer counsel through engaging game narratives. I focus on the games mentioned here not because they are the only ones that aspire to offer the kind of rich narrative experience that this Benjamin-derived model asks for, but because they offer a particularly high number of salient examples.

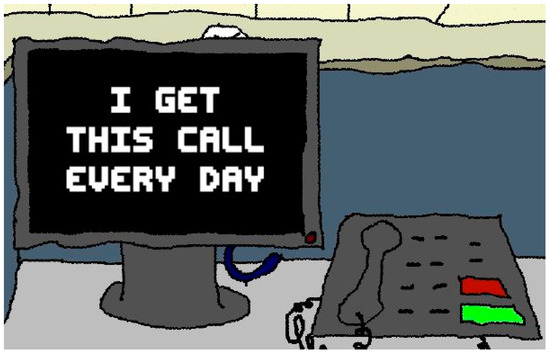

These games can be at times impressionistic in refusing to offer a clear-cut resolution or lesson. In this, they mirror Benjamin’s beloved stories, while deviating from industry norms that continue to celebrate good vs. evil superhero values and emphasize simple win/loss dichotomies. The most effective narrative games are often much subtler and less easily recognizable. While some potentially provocative games adhere to the standards of recognized genres—3rd World Farmer (Independent, 2005), for example, is a resource-management-driven farming sim—others present intimate, ambiguous tales through the medium of the game. In this, they both are artisanal in the sense of providing distinct experiences and experiential. The ambiguity of games like I Get This Call Every Day (Independent, 2013) does not provide players with lessons, but rather invites them to reflect and reach their own conclusions. Both 3rd World Farmer and I Get This Call Every Day present complex narrative worlds even while dealing with daily realities. In 3rd World Farmer, the player is tasked with maintaining a small family farm in the face of harsh weather, disease, militant uprisings, theft, and political corruption; the impact of these factors on the farm and the family that lives there is relayed through orderly charts that summarize the underlying horrors. Crops fail. The money runs out. Family members die. I Get This Call Every Day is focused on the developer’s experience working in a call center (see Figure 2). The calls presented were fabricated and scripted, but the fictionalized call center was so believable that the developer was fired from his job, in part because of allegations that he was relaying real calls (Campbell 2013a).

Figure 2.

The opening screen for I Get This Call Every Day places the player in a first-person perspective at a call desk.

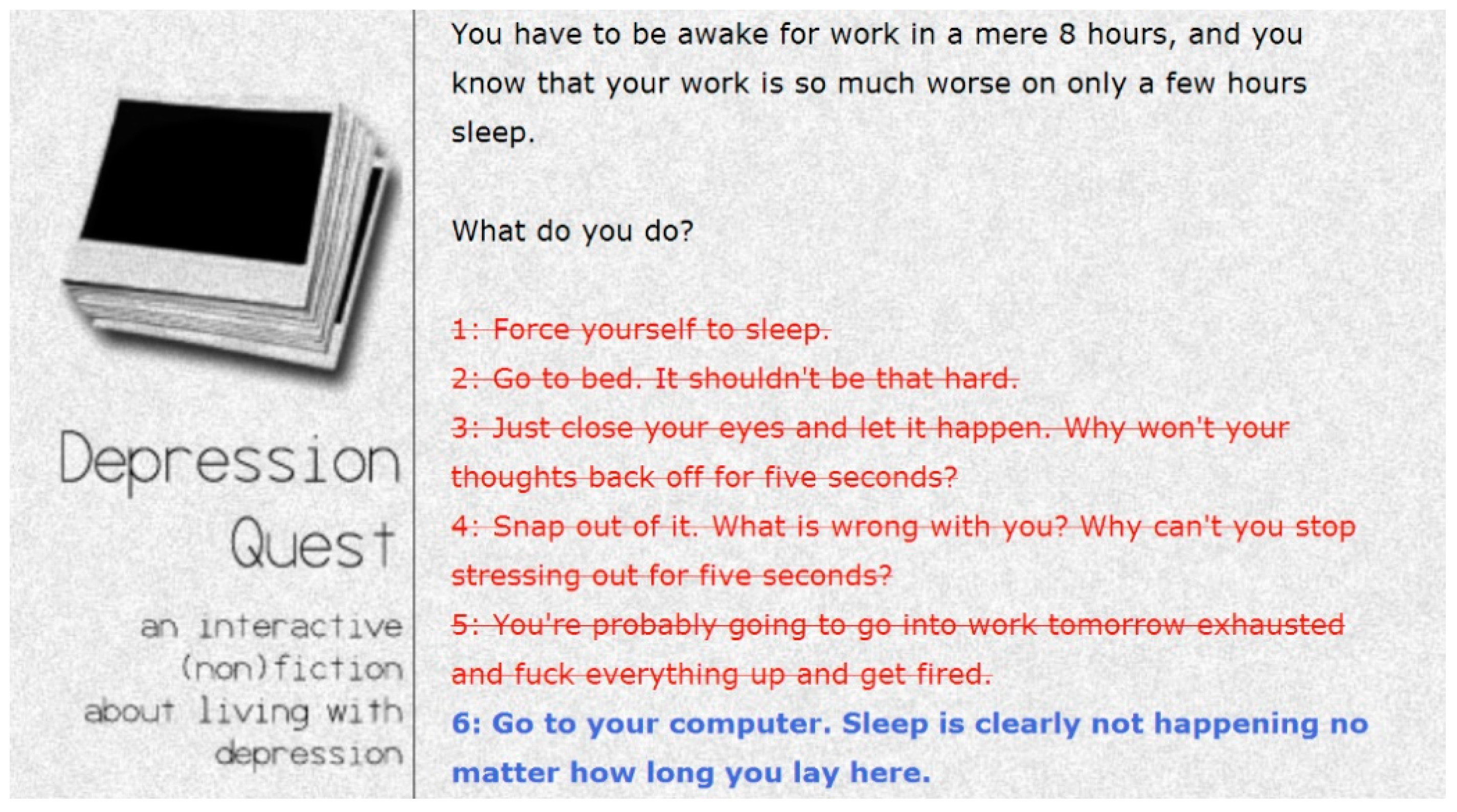

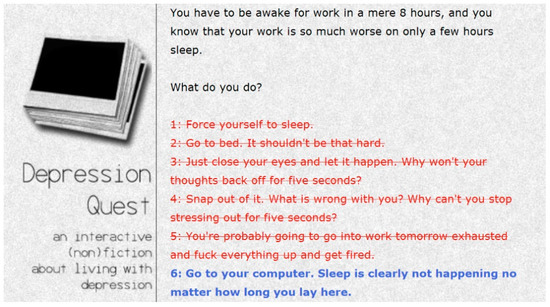

Depression Quest, like many games that explore lived human experiences, is focused on a particular hardship. In it, the player assumes the role of a depressed twentysomething. The game offers players frustration, recognition, and reassurance. If the player makes choices that help the character to improve their life, more pleasant options and scenarios emerge. If the players’ choices result in the character’s options becoming more limited, those unavailable options will be shown struck through in red (see Figure 3). The game has a soundtrack of faint atmospheric music in a minor key. As the character becomes more depressed, the images embedded in the game become more and more obscured by static; if the character becomes less depressed, the images grow clearer. Through these mechanics and through stylistic and narrative choices, the game seeks to provide a bit of experiential knowledge of depression for players. When the game was released, blog posts and articles often recounted the extent to which players used the game to recognize depression in themselves or work out a path towards treatment (Klepek 2015).

Figure 3.

Depression Quest steadily eliminates options as the game unfolds.

Some research on games shows they can be effective at fostering empathy (Flanagan et al. 2008; Greitemeyer et al. 2010). In doing so, the most effective of these games may include facts without focusing on them, concentrating instead on immersive game play that invites players to experience feelings. In this way, at their best, they—like Benjamin-type storytelling—require reflection and invite the audience to make their own sense of the experience. They also provide seemingly personalized experiences, sometimes exposing the designer or developer in the process. If players of Depression Quest recognize themselves in the game’s struggling protagonist, they are also recognizing the life experience of developer Zoe Quinn, who has been open about the high extent to which the game is autobiographical. There are morals and fables to be learned from games, even in those that refuse to provide clear answers. Too often, educational games provide rote information or pedantic definitives. Some of the best narrative games relay experiences by putting the player in another person’s situation and inviting the players to make their own conclusions. They provide a framework in which the player can understand their world differently.

Syrian Journey: Choose Your Own Escape Route (2015), distributed by the BBC, challenges players to make the “right” decisions as they flee as refugees from Syria. In Richard Hofmeier’s Cart Life, the player is shoved into the brutalities of trying to run a small retail business while maintaining a life and receives an at times grueling lesson in the realities of life under late model capitalism. Both of these games present realities through graphic styles that are easily identifiable. They have a distinct aesthetic and feel deeply personal. There is a real intimacy to the experiences these games provide, in part because they invite players to consider what someone else’s life is like. They tell stories through immersive, mediated experiences. At both their most reassuring and their grimmest, these games provide opportunities for human connection, for making people feel less alone as they plunge into stories that provide a flash of recognition. In this, perhaps they offer counsel, wisdom, the kind of moral education that so much relies upon.

5. Conclusions

I return now to my original focus on Benjamin, on McMurtry, on that Dairy Queen along a dusty highway in Archer City. The promise of storytelling, as Benjamin and McMurtry view it, is powerful; it is a tool for forming communities and establishing networks, for making brutal places less so, for preserving folklore and tradition, for providing a sense of place and comfort. Discussion of the possibilities of innovative, immersive, experimental games often focuses on their potential instrumentality, and at points games may be effective in this way, in teaching division or geography to grade schoolers or helping adults to prepare for job tasks. But games like these often fail to be playful. They also fall short of the deeper potential of games as an immersive storytelling medium that could help us to explore values, wisdom, and our own inner lives. This is not a call to value one kind of games over another, but rather it is a call to think of games as part of a broader cultural web of storytelling; to look back to oral traditions and practices of community as a source not only of abstract inspiration, but concrete practice. We learn from one another, but we also learn from play, as do most intelligent animals. This is why are impressed when cephalopods and dolphins make toys from the items in their tanks or grackles roll down the windshields of snow-covered cars. It is also why, in thinking about developing serious games or meaningful games or learning games or any games at all, we should think broadly, not just about the information they might impart, but the experiences and wisdom they can provide.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Benjamin, Walter. 2006. The Storyteller. In The Novel: An Anthology of Criticism and Theory 1900–2000. Edited by Dorothy J. Hale. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 361–78. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Jessica, and Jennifer L. Barnes. 2015. Fiction and Social Cognition: The Effect of Viewing Award-Winning Television Dramas on Theory of Mind. Psychology of Aesthetics Creativity and the Arts 9: 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bransford, John D., Jeffrey J. Franks, Nancy J. Vye, and Robert D. Sherwood. 1989. New Approaches to Instruction: Because Wisdom Can’t Be Told. In Similarity and Analogical Reasoning. Edited by Stella Vosniadou and Andrew Ortony. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 470–97. [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead, Pat, Justine Howard, and Elizabeth Wood, eds. 2010. Play and Learning in the Early Years. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Gillian. 1997. Fables and the Forming of Americans. MFS Modern Fiction Studies 43: 115–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callois, Roger. 2006. The Definition of Play and the Classification of Games. In The Game Design Reader: A Rules of Play Anthology. Edited by Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 122–55. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Collin. 2013a. Fired For Making A Game: The Inside Story of I Get This Call Every Day. Polygon. March 7. Available online: http://www.polygon.com/features/2013/3/7/4071136/he-got-fired-for-making-a-game-i-get-this-call (accessed on 19 February 2015).

- Campbell, Collin. 2013b. The Oregon Trail Was Made in Just Two Weeks. Polygon. July 31. Available online: http://www.polygon.com/2013/7/31/4575810/the-oregon-trail-was-made-in-just-two-weeks (accessed on 18 February 2015).

- Cook, Guy. 2000. Language Play, Language Learning. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, Kerry A., and Don Harris. 1998. Computer-based simulation as an adjunct to ab initio flight training. The International Journal of Aviation Psychology 8: 261–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deWinter, Jennifer, Carly A. Kocurek, and Randall Nichols. 2014. Taylorism 2.0: Gamification, Scientific Management and the Capitalist Appropriation of Play. The Journal of Gaming and Virtual Worlds 6: 109–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkind, David. 2007. The Power of Play: Learning What Comes Naturally. New York: Da Capo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, Mary, Daniel Howe, and Helen Nissenbaum. 2008. Embodying values in technology: Theory and practice. Information Technology and Moral Philosophy, 322–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, James Paul. 2003. What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. Computers in Entertainment (CIE) 1: 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greitemeyer, Tobias, Silvia Osswald, and Markus Brauer. 2010. Playing Prosocial Video Games Increases Empathy and Decreases Schadenfreude. Emotion 10: 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossberg, Lawrence. 1986. On postmodernism and articulation: An interview with Stuart Hall. Journal of Communication Inquiry 10: 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, Robert T., John W. Jacobs, Carolyn Prince, and Eduardo Salas. 1992. Flight Simulator Training Effectiveness: A Meta-analysis. Military Psychology 4: 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizinga, Johan. 1971. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Issenberg, S. Barry, William C. McGaghie, Ian R. Hart, Joan W. Mayer, Joel M. Felner, Emil R. Petrusa, Robert A. Waugh, Donald D. Brown, Robert R. Safford, Ira H. Gessner, and et al. 1999. Simulation Technology for Health Care Professional Skills Training and Assessment. JAMA 282: 861–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issenberg, S. Barry, William C. Mcgaghie, Emil R. Petrusa, David Lee Gordon, and Ross J. Scalese. 2005. Features and Uses of High-fidelity Medical Simulations That Lead to Effective Learning: A BEME Systematic Review. Medical Teacher 27: 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juul, Jesper. 2005. Half-Real: Video Games between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Klepek, Patrick. 2015. They Made a Game That Understands Me. Giant Bomb. April 10. Available online: http://www.giantbomb.com/articles/they-made-a-game-that-understands-me/1100-4619/ (accessed on 19 February 2015).

- Linderoth, Jonas. 2012. The Effort of Being in a Fictional World: Upkeyings and Laminated Frames in MMORPGs. Symbolic Interaction 35: 474–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Geoffrey. 2016. Creating Worlds in Which to Play: Using Transmedia Aesthetics to Grow Stories into Storyworlds. In The Rise of Transtexts: Challenges and Opportunities. Edited by Benjamin W. L. Derhy Kurtz and Mélanie Bourdaa. New York: Routledge, pp. 139–52. [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson, Cale D., and Lynn A. Barnett. 2013. The Playful Advantage: How Playfulness Enhances Coping with Stress. Leisure Studies 35: 129–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantle-Bromley, Corinne, and Ann M. Foster. 2005. Educating for Democracy: The Vital Role of the Language Arts Teacher. The English Journal 94: 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, Merrilea J. 2007. Games for Science and Engineering Education. Communications of the ACM 50: 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGonigal, Jane. 2011. Reality is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- McMurtry, Larry. 1999. Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen: Reflections at Sixty and Beyond. New York: Touchstone. [Google Scholar]

- Mouffe, Chantal, ed. 1979. Hegemony and Ideology in Gramsci. In Gramsci and Marxist Theory. London: Routledge, pp. 168–204. [Google Scholar]

- Prensky, Marc. 2006. Don’t Bother Me, Mom, I’m Learning! How Computer and Video Games Are Preparing Your Kids for 21st Century Success and How You Can Help! New York: Paragon House. [Google Scholar]

- Proyer, René T. 2013. The Well-being of Playful Adults: Adult Playfulness, Subjective Well-being, Physical Well-being, and the Pursuit of Enjoyable Activities. European Journal of Humour 1: 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieber, Lloyd P. 1996. Seriously Considering Play: Designing Interactive Learning Environments Based on the Blending of Microworlds, Simulations, and Games. Educational Technology Research and Development 44: 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, Daniel T. 1980. Socializing Middle-class Children: Institutions, Fables, and Work Values in Nineteenth-century America. Journal of Social History 13: 354–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Marie-Laure. 2001. Narrative as Virtual Reality: Immersion and Interactivity in Literature and Electronic Media. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Francis J., John J. Sweeder, and Maryanne R. Bednar. 2002. Character Education in the English Language Arts Classroom. Counterpoints 122: 91–114. [Google Scholar]

- Schrier, Karen S. 2016. Knowledge Games: How Playing Games Can Solve Problems, Create Insight, and Make Change. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, David Williamson, Richard Halverson, Kurt R. Squire, and James P. Gee. 2005. Video Games and the Future of Learning. WCER Working Paper No. 2005-4. Madison: Wisconsin Center for Education Research. [Google Scholar]

- Short, Jeremy C., and David J. Ketchen. 2005. Teaching Timeless Truths through Classic Literature: Aesop’s Fables and Strategic Management. Journal of Management Education 29: 816–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, Dorothy G., Roberta Michnick Golinkoff, and Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, eds. 2006. Play = Learning: How Play Motivates and Enhances Children’s Cognitive and Social-Emotional Growth. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo, Karen, Barbara Chamberlin, Karin Wiburg, and Amanda Armstrong. 2016. Measurement in Learning Games Evolution: Review of Methodologies Used in Determining Effectiveness of Math Snacks Games and Animations. Technology, Knowledge and Learning 21: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeule, Blakey. 2009. Why Do We Care About Literary Characters? Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, Douglas A. 1995. Stories, Fables, and Fairy Tales as Teaching Tools. Human Service Education: A Journal of the National Organization for Human Service Education 15: 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zunshine, Lisa. 2006. Why We Read Fiction: Theory of Mind and the Novel. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).