2.1. Architecture and Painting Art

Ajanta is the sole monumental record of classical Buddhist culture that is preserved in a land that gave birth to this religion, and also influenced the culture of other Asian countries. The thirty odd caves cut into horse shoe shaped scrap of a steep cliff overlooking the Waghura river are the best creations of the time which inspired Buddhist in central Asia, China and south-east Asia.

Ajanta painters were guided by a highly developed sense of blending of colors with a view to produce total impression with three dimensional effects giving true perspective to line and plane. Besides, the technique of giving three dimensional effects to the painting was first introduced in India in the cave paintings of Ajanta in 3-4 century A.D.

Figure 2 shows some of the paintings of Ajanta showing three dimensional effects. This technique was later copied by the other artist in the Asian region.

Figure 2.

Showing Three Dimensional Paintings from cave 1 and 26, Ajanta.

Figure 2.

Showing Three Dimensional Paintings from cave 1 and 26, Ajanta.

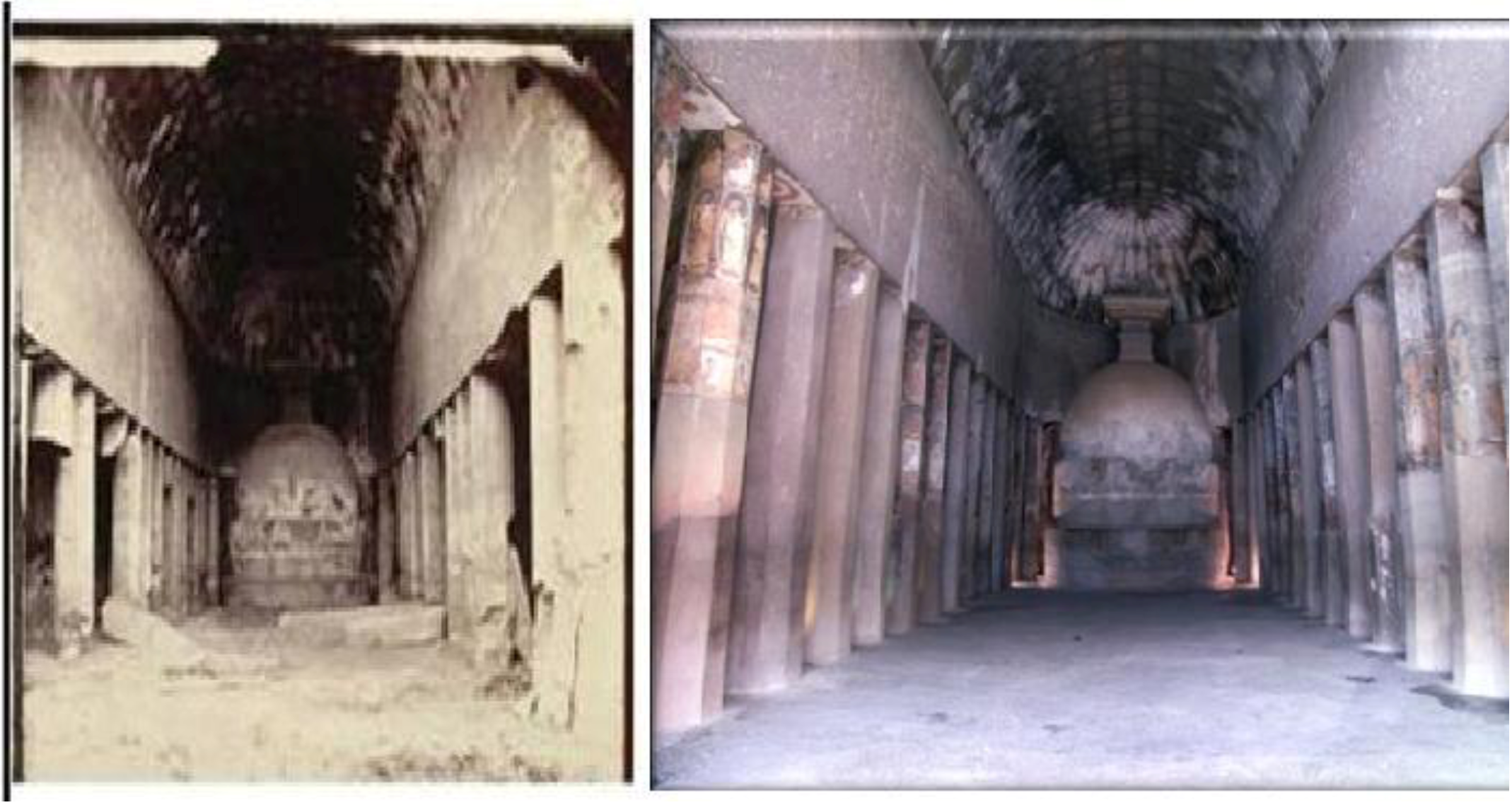

The first of Ajanta caves were started in about the first century B.C. (

Figure 3) that included the impressive chaitya hall, cave 10 and simple associated vihara cave 12 all done by true community effort [

18]. The repainting in old Hinayana cave no 9 &10 was made in 3-4 A.D but the plan was never realized except by painting some more areas of the cave [

19,

20].

Figure 3.

Showing View of Hinayana Caves 9 & inner view of Cave 13.

Figure 3.

Showing View of Hinayana Caves 9 & inner view of Cave 13.

The dramatic idea of creating rock cut monasteries at both Ajanta and Bagh was developed by their respective patrons in Vakataka period 3-4 A.D. Undertaking Ajanta excavation some 400 to 500 years after the Hinayana phase must have involved advance planning as well as supporting patrons, monks, workers, who must have come from number of different parts of the Vakataka empire [

21]. It seems clear that when such a major cave was started, the delegation of architects (now the excavators) and members of Buddhist sangha must have surveyed the site, deciding upon the best and appropriate location. In the case of vast cave 26 complexes, patronized by Asmaka, they were careful to choose the location into which the projected monument would fit and monks may reside in vihara at right in cave 21-25 and left in cave 27, 28. Cave 26 drew upon the precedent of the Hinayana chaitya cave 10; though again with the intention of adding appropriate modern features (

Figure 4). When the four wings were planned for this ambitious cave complex, all were essentially based on the layout of ancient cave no 12. Similarly, the plan of cave 19 drew the precedent of Hinayana cave 9. The two impressive caitya hall of cave 19&26 conceived as intended ceremonial centers for the site. The former (cave 19) is referred as “Vakataka” area including the entire excavation upto cave 20. The other (cave 26) is described as “Asmaka” area starting with cave 21 to 28. The Asmaka were in fact feudatories of the Vakataka emperor.

Figure 4.

Outer and Inner View of Hinayana Cave 10, Ajanta.

Figure 4.

Outer and Inner View of Hinayana Cave 10, Ajanta.

In course of time when two chaitya hall caves 19 and 26 were still being roughed up, the controlling officials have decided that the two caitya halls should be oriented to the solstice’s, cave 19 to winter solstices and cave 26 to summer. The sun rays should coincide with the axis of cave. Such a significant astrological alignment must have meaning and importance to the planners. This was all very well had the excavation of two caves not already been started at a quite different angle. In fact, the cutting of both the caves had proceeded to the point that new required adjustment could not be effected.

To implement the order in cave 26, the excavators were able to locate the stupa by adjusting forward almost two feet from its normal position (

Figure 5). In fact, this is the only caitya hall in India where the space around the stupa is not equidistant at left, rear and right. Then, at the same time by adjusting the frame of the great inner arch under the outer vault rightward in relation to outer facade arch, the planners were able to achieve the desired solstice alignment through the “sun-window” to the stupa.

Figure 5.

The outer and inner view of cave 26, Ajanta. The stupa was aligned for summer solstice and is not in the center of cave.

Figure 5.

The outer and inner view of cave 26, Ajanta. The stupa was aligned for summer solstice and is not in the center of cave.

Cave no.19 presented much greater difficulties (

Figure 6). Fortunately, the interior pillars and stupa had already been roughed up by the time the order came and hence cannot be re-positioned. However, the carvers did what they could do to surge the stupa to the left, its upper elements were shifted leftward and even Buddha image stands slightly to the left, while the whole stupa base is wrenched into a leftward asymmetry. The pillars towards the cave left rear were squeezed a few inches left ward and pillar 1 and 7 just to the left of stupa were slightly reduced in size. The exterior of the cave 19 was also angled in the solstitial direction to a significant degree, through it does not reach the proper solstitial alignment, as it has already been roughed up and could not be twisted more than at present.

Figure 6.

Outer and Inner view of cave 19, Ajanta: for its alignment to winter solstices external part was little curved and inner part also altered.

Figure 6.

Outer and Inner view of cave 19, Ajanta: for its alignment to winter solstices external part was little curved and inner part also altered.

Some alignments were also made due to flaws or faults in the rock being cut. One fine example is cave 26: R.H.S Buddha on upper portion of wall wherein one Buddha has been positioned differently due to flaw in the stone.

Figure 7 shows this deviation.

Figure 7.

The last eighth Buddha from right to left in different Mudra due to flaws in the stone.

Figure 7.

The last eighth Buddha from right to left in different Mudra due to flaws in the stone.

Geological factors were yet another feature that imposed restraints, although at first the planners seemed less concerned or less aware than was the case later when excavators more and more adjusted the positioning of their cave in accordance with the problematic flaws in the rock. The positioning of early cave 8 is the case in point. Planners thought this location, lower than any of the adjacent caves and easy to access from the old river path, were quite ideal but it surely reflects inexperience of early Vakataka undertaking. There is a thick horizontal deposit of red bole, a very weak clayey rock running through the basalt at a descriptive height and presenting problem that would have warned to abandon any excavation. As we see, work went on with dire consequences (

Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Cave 8 with weak rock causing problem to its stability and various excavators working on the same pillar of cave upper 6.

Figure 8.

Cave 8 with weak rock causing problem to its stability and various excavators working on the same pillar of cave upper 6.

The same lack of awareness or thought resulted in an equally embarrassing situation in cave 11 and the mistake was particularly costly in terms of time, money and desired results. One of the initial patron opted to put small vihara planned with three cells on each side in the unusual space between the old Hinayana cave 10 and 12. The space may have been seemed quite auspicious and patron thought ample space towards the rear of the cave than towards the front. However, this is not the case here. The old Hinayana cave 10, it turns out, does not follow the expected pattern. It is angled subtly but sharply to the left, probably to adjust for a troubling vertical flaw in its façade area and this had dire consequences to the excavators. As noted, cave 11 by error was located too close to ancient cave 10 and as consequence the three cells on the right side could not be cut to make up the loss; the planners “relocated” the missing cells with considerable difficulties in the porch of cave 11. Indeed, they even added one more to compensate for the loss of hall rear central cell. It seems reasonable to assume that this innovation of the planner in cave 11 sparked a new trend of putting cells in the porch affecting caves 4, 15, 16,17,20,26, 26 LW and 27. Indeed, in few cases the planners now dissatisfied with old fashioned single cells, converted them to more complex forms by cutting new pillared fronts out of their front wall.

Figure 9 shows both the simple and complex outer cells at Ajanta.

Figure 9.

Simple and complex outer cells at Ajanta.

Figure 9.

Simple and complex outer cells at Ajanta.

Cave 11 and cave lower 6 were supplied with interior pillars for purely expedient reasons: Cave 11 out of concern that ceiling might collapse due to serious flaw in the rock just above, and cave lower 6 out of concern that ceiling might collapse because of the earlier unanticipated presence of its added story.

Further development of great importance was the beginning of work of cave 1 by the emperor Harisena himself. At Bagh, the friable nature of sandstone so much weaker than Ajanta basalt apparently made it impossible to excavate the expected chaitya hall at the side. Probably, for this reason, cave 2 Bagh was converted into chaitya hall by addition of a chamber with stupa. The slightly later cave at Bagh was intended to be shrine from the start.

These development at Bagh revolutionized Ajanta as well (

Figure 10).

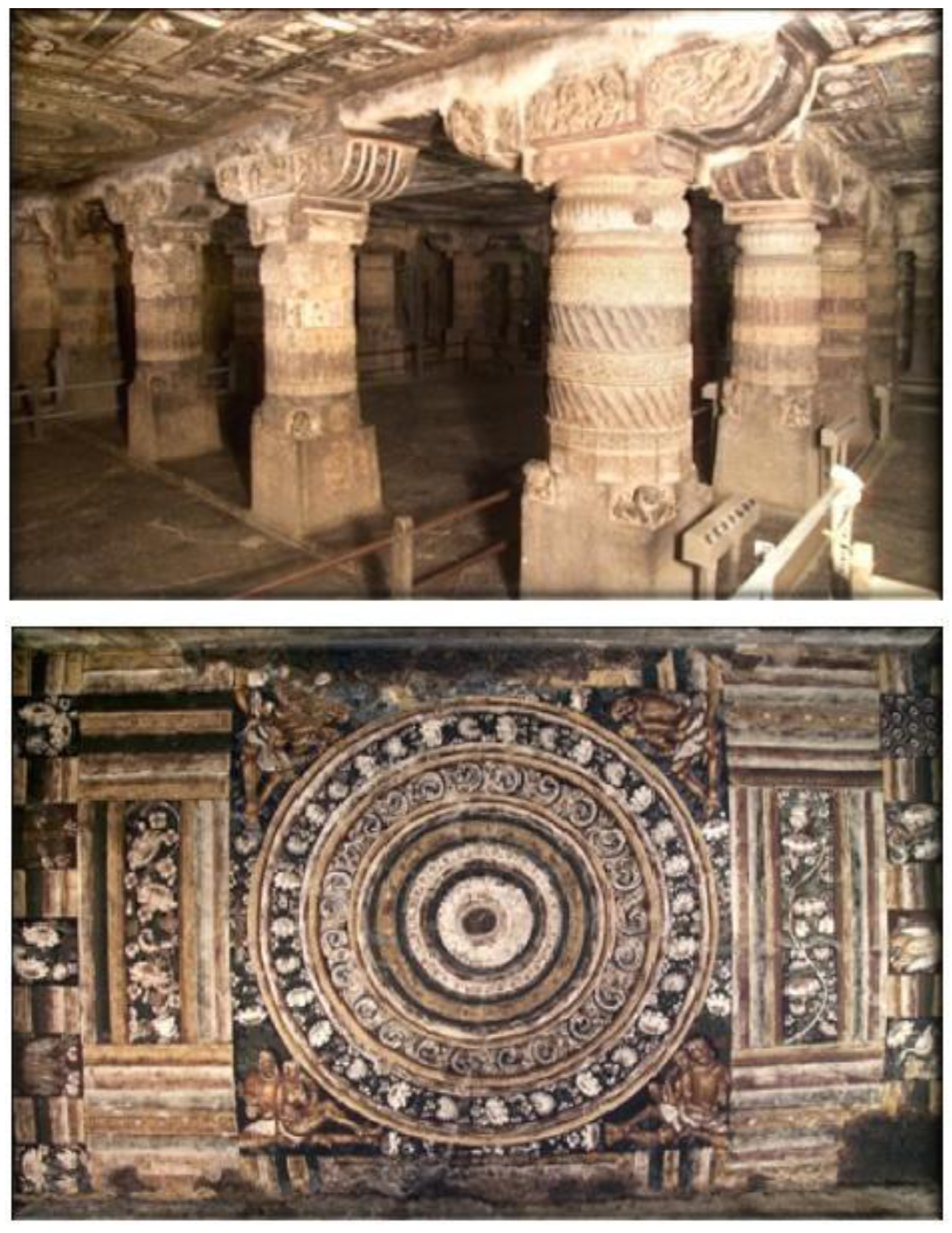

Figure 10.

Inner view of cave 2 and its beautiful medallion.

Figure 10.

Inner view of cave 2 and its beautiful medallion.

This is because the great cave 1 was probably the very first vihara at Ajanta to have been planned from the start with a shrine, and although cave 1’s shrine today contains a fine Buddha image, it is almost certainly originally intended to house a stupa. Although stupa rapidly yielded to the Buddha image, an abandoned stupa in cave 11 backs the completed image, while the image in cave lower 6 may have been cut from a block originally shaped to hold stupa. Cave 11’s stupa was clearly its original focus. In fact, it was abandoned in favors of an image carved from the same matrix. This seems to represent the moment of transition from stupa to image (

Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Addition of attendants in later cave 17’s Buddha whereas cave 6’s Buddha was cut from a proposed stupa with adjustment.

Figure 11.

Addition of attendants in later cave 17’s Buddha whereas cave 6’s Buddha was cut from a proposed stupa with adjustment.

One important feature needs special attention in cave 4, 16 and 17: they splay outward as we approach the rear of the cave. That is the rear side is considerably longer from its left to its right end than in case of front aisle. Due to understandable inexperience of the excavators, they were not able to control their cutting as they proceeded from front to back with the effect the wall surface angled outwards. By the time the rear of the cave was reached, the misalignment could amount to as much as few feet, making the cave unexpectedly trapezoid. This has happened in early caves but discipline later prevented this problem.

In cave 4, the excavators accumulating error resulted in cave 4 ceiling rising nearly five feet from the front of the hall to the rear of the shrine. Of course, the floor level has shown similar rise having been made parallel to the ceiling by consistent measurement with something like bamboo pole. Later on, the excavators corrected these early errors by leveling the ceiling and the floor at the shrine by about five feet. Of course, these corrective measures to level the cave was able to house the tallest Buddha at the site in cave 4.

However, the situation was different in case of ceiling of cave 17. It was also exposed quite early and was subjected to similar error. However, is seems that the excavators kept correcting their errors as work proceeded. Thus, when ceiling level angled upward, they soon brought it down when it angled upwards again they brought it down again. The result of these continuous corrections was waviness of surface, which is now explained as attempt to create the effect of flying carpet or shamiana (

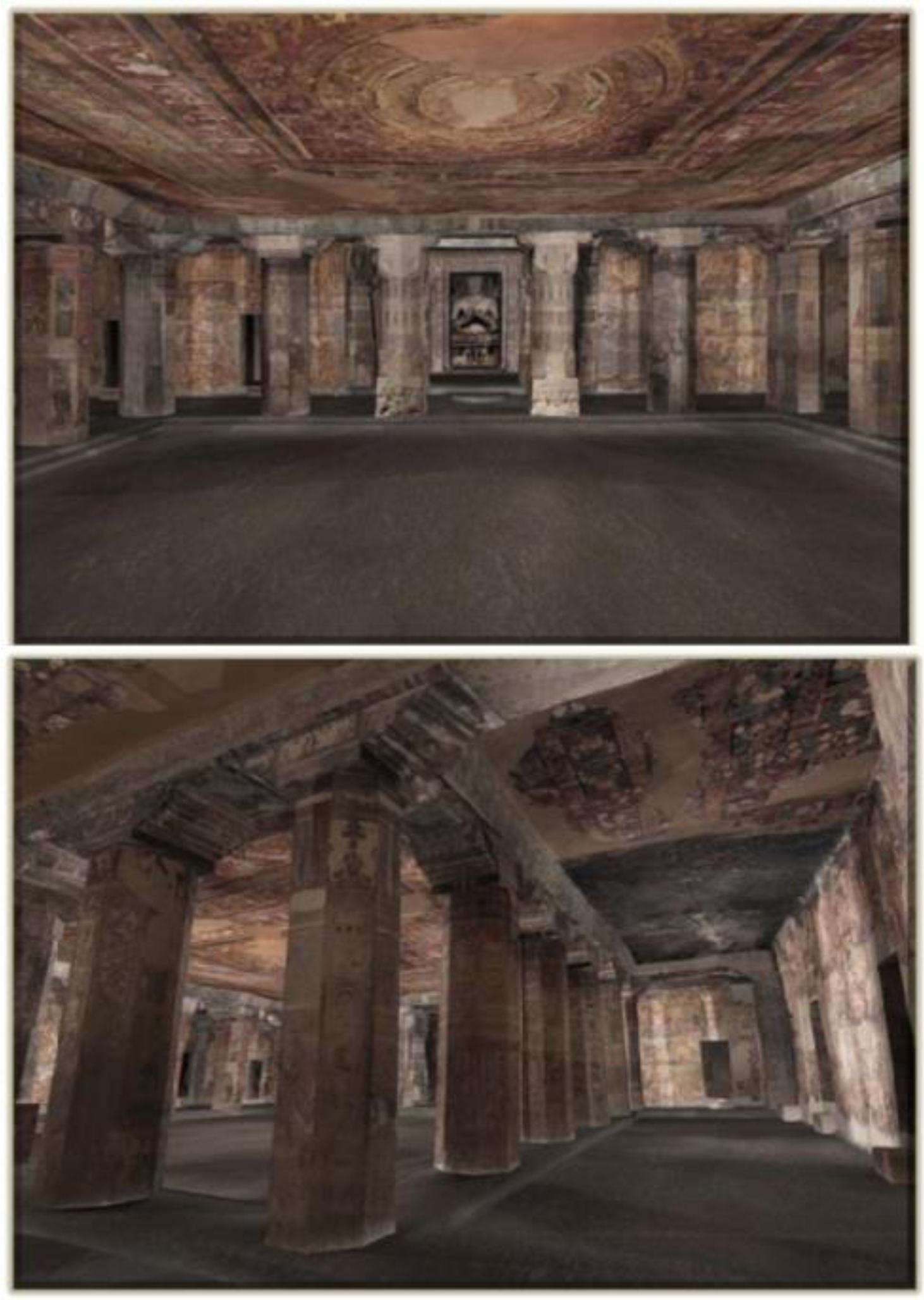

Figure 12).

Figure 12.

A 3D view of cave 17’s ceiling (Flying Carpet) and aisle.

Figure 12.

A 3D view of cave 17’s ceiling (Flying Carpet) and aisle.

Some unfinished caves like 5 and 24, gives an idea about cutting the rock with long chisel and hammer, without any need of scaffolding (

Figure 13). Probably, the excavators used intermittent left over part of the rock to climb and finish the work before its actual removal from cave interiors. As we can also see from still incomplete interiors of cave 24, a considerable amount of matrix was left enclosing the projected pillars. Thus, later adjustment was possible for the pillars, which could be slightly repositioned to achieve a more balanced spacing.

Figure 13.

General view of unfinished cave 24 and later ornamentation of Ajanta Pillars based on Bagh caves design.

Figure 13.

General view of unfinished cave 24 and later ornamentation of Ajanta Pillars based on Bagh caves design.

The late work of Ajanta was under deep influence of developments at the far most stable Buddhist site at Bagh in peaceful Anupa [

17]. The Bagh, also a Vakataka site started at about the same time that of Vakataka phase at Ajanta. However, unlike Ajanta the Bagh regions was not troubled and it provided a safe haven for Ajanta workers during the fight of feudatories. Surprisingly, by when the displaced workers were able to return to Ajanta, they brought back many things that they learned at Bagh. Important iconic innovation, being the concept of Buddha with attendant, elaborated doorways, decoration of pillars and pilaster etc. are some examples.

2.3. Conservation of Mural Paintings:

Ajanta is a monument to paintings of Buddhist faith. Many of the paintings have been executed on mud plaster, which contains clayey matter of high to low swelling nature admixed with organic additives such as rice husk, plant seeds and leaves,

etc. Due to variation of 40-50% in relative humidity inside the cave [

23], the nature of support has an important bearing on the overall condition of Ajanta paintings. The clayey fraction and its plasticity is a major factor of interaction of earthen support with other structural elements, with the painted surface and with environmental changes.

With the discovery of the caves in 1819, many of the paintings in most ancient caves 9 and 10 were copied in the 19

th century when they were in much better state of preservation than today [

24]. In 1920, the Italian conservators applied thick coat of unbleached shellac varnish to the already varnished surface without removing the old varnishes. Meanwhile the thick shellac oxidized and changed color to reddish brown in Indian climatic condition. Besides, contraction and expansion due to environmental factor also created pattern of cracks in the body of original paintings. Around two third of Ajanta paintings are also found covered with dirt, dust, altered shellac, natural resins and at few places polyvinyl acetate. Deposition of soot is also noticed in those caves that were under worship at Ajanta.

The presence of a large quantity of superimposed materials does not always allow a clear vision of the original pigment layer and also renders the cleaning operation difficult. Besides altering visual appearance of pigment layer, the superimposed materials also restrict the breathability of underlying surface, thereby causing ridges, gaps, lacuna and sometimes the fall of pigment layer. Pigments of Ajanta have now been clearly identified with non-destructive/destructive analysis of micro samples [

25].

As the Ajanta paintings have been executed by tempera technique with animal glue as binding media, use of any water based solvent mixture for cleaning is totally ruled out. Many of the painted surfaces of Ajanta were cleaned by first consolidating the fragile surface with the help of a lime and caseins mixture and allowing it to dry properly. After complete drying, the varnishes layers along with soot and grime were removed using mixture of organic solvents such as morpholine, butyl lactate, n-butyl amine, butyl lactate, butanol, ethanol, and dimethyl formanide in various ratios with dexterity and patience [

26]. No attempt was made to remove last traces of accretions as precautionary measures. The main intention of chemical cleaning measures was to make the surface to breathe.

Figure 16 shows before/after treatment photograph of recently executed chemical cleaning of painted surface of Ajanta. Around 10–15 % of the surface accretions were left as such daring cleaning operation as safety layer.

Figure 16.

Scientific conservation of murals of cave 10, Ajanta.

Figure 16.

Scientific conservation of murals of cave 10, Ajanta.