1. Introduction

With the arrival of text-to-image AI systems, one of the oldest myths of Western visuality becomes refreshed: the image that generates itself.

Chris Chesher and César Albarrán-Torres (

2023, 57) use the term ‘autolography’

1 for AI systems, such as Dall-e 2 and Midjourney, automatically translating text into ‘evocative original images’, causing a sensation in mid-2022. They identify parallels and divergences with ancient practices, likening the invocation of a Muse to how natural language prompts cause the algorithmic creation of images that ‘might pass as art’; they compare autolography’s public and critical reception with those of photography, and note the links with Western magical imagination, including stage magic; they question where creativity resides—beyond the pressing of the shutter or the writing of the prompt—and predict a struggle for AI systems to ‘gain faith in their reality’ (

Chesher and Albarrán-Torres 2023, 58–70).

While

Chesher and Albarrán-Torres (

2023, 59) speak of a ‘secular magic’, this AI lineage can be expanded to include magical religious images also known as

acheiropoieta, meaning images ‘not made by [human] hand’ (

Belting 1994, 49). This paper discusses some of the ‘miracle images’ that I witnessed in my doctoral study between 2018 and 2022, and reflects upon the significance of such phenomena. Through the lens of Practice as Research (PaR), it situates digital photogrammetry as a knowledge ground, wherein the self-made image continues to perform the faith structure of earlier visual culture. It argues that such digital ‘holy’ images are not dematerialised artifacts of computation, but contingent events that may act as revelations of the persistence of belief in the self-generating image.

This writing traces the material and theological lineage that connects contemporary AI-generated images with acheiropoieta, illuminating the purposely erased human hands that made such images ever possible. Against the seductive pull of machinic automation and the extractive infrastructures of generative AI, I advocate for

cheiropoieta—images made by hand—as a curatorial ethics that foregrounds labour, embodiment, and material friction. There are thus two interlinked aims: firstly, to place digital photogrammetry within a lineage of self-generating images from religious acheiropoieta to photography to contemporary AI; secondly, to demonstrate how a PaR methodology, following Robin Nelson’s model of a research project that has practice at its heart (

Nelson 2022, 40, 47), may expose the hidden labour(s) and embodied presence(s) behind supposedly self-made digital artifacts. The intended readership includes scholars and practitioners of visual culture, media archaeology, heritage technologies, and Practice as Research in the arts.

2. Not Made by Hand

In his critique of (un)creative artificial intelligence,

Dieter Mersch (

2020, 25) discusses the ‘”works” by machines’ whose only draw is an insipid fascination in the fact that they were supposedly made without the help of people; he calls this ‘a revamping of the myth of the Acheiropoieta’. While, for Mersch, this is as untrue today as it was back then, for this writing it is pertinent to persist with these celestial images, particularly for their religious/faithful lineage.

Kitzinger (

1954, 113) explains that there are two kinds of acheiropoieta: either believed to have been made by non-human hands, ‘or else they are claimed to be mechanical, though miraculous, impressions

2 of the original’ Acheiropoieta not only self-generate, but they also self-replicate, and

Kitzinger (

1954, 115) describes how a celestial ‘found’ picture of Christ, wrapped in a cloth while being transported, produced an identical copy of itself on the cloth; in that moment, the two varieties of miraculous images are combined, fusing together revelation with reproduction. Kitzinger notes that the idea of mechanical reproduction seems to be more popular than the celestial, making the icon an organ of the deity itself; of particular interest is his comment that mechanical reproduction within acheiropoieta is curiously prophetic of methods used in photography.

Fulfilling that prophecy, ‘the invention of the photograph indicated the return of the acheiropoieton’ (

Petri 2018, 166). Photography’s self-generating quality is evident in the words of one of its pioneers, William Henry Fox Talbot, that it is not the artist who makes the picture, but the picture which makes itself; photography is ‘nature’s pencil’ and ‘natural magic’ (in

Geimer 2011, 28–29). Indeed,

Peter Geimer (

2011, 29) considers some of André Bazin’s meditations from 1945 to read like a compressed and revised version of Talbot’s thoughts. For Geimer, it is no coincidence that Bazin invokes the Turin shroud, allegedly containing Christ’s only authentic reproduction (2011, 29). When Bazin exclaims that ‘the image […] shares, by virtue of the process of its becoming, the being of the model of which it is the reproduction; it

is the model’ (

Bazin 1967, 14 emphasis in the original), the iconicity of the photographic image is striking; as per

Marie-Jose Mondzain (

2005, 66), ‘[t]he icon will escape the function of reference; rather, it will itself become what is referred to’.

What the above allows is an understanding of the centrality of the miracle within processes that, in essence, require the occlusion of the hand that paints that image, presses the shutter, designs the algorithm, crafts the images that train the datasets, and so on. And while, particularly since 2023, the discourse around image-making has been dominated by AI, digital photogrammetry was for a certain period of time the new miracle within the acheiropoieton lineage of icon and photograph, with the 3D digital model recombining the celestial picture miraculously found and the imprinted relic.

3. The Camera-Walk

Between 2018 and 2022, I conducted a number of ‘camera-walks’ whereby I would walk a public or private space, while holding in my hand a camera-on-a-stick. Walking

grounded my methodology, paying attention to social anthropologist

Tim Ingold’s (

2004, 330) assertion that it is ‘through our feet, in contact with the ground […] that we are most fundamentally and continually ‘in touch’ with our surroundings’. My GoPro Fusion, a consumer 360 camera, shot panoramic (360) video, which I would subsequently ‘hack’ into its constituent frames and process them through digital photogrammetry. The camera was launched in 2017; it could be attached to sports equipment or to its wearer’s helmet, or carried with an extendable selfie-stick that doubles as a tripod. Unable to affect its programme while shooting, and without a viewfinder or liquid-crystal-display (LCD) screen for me to see what it was doing, the camera would frame my walk in terms of purpose, but never frame my actual view. Rather, the 360-video frame is omniscient—a technical image exceeding human vision. With its mysterious and opaque automatisms, my camera’s compact plastic body settles well with Vilém Flusser’s apparatus, whereby ‘[a]nyone who is involved with apparatuses is involved with black boxes where one is unable to see what they are up to’ (

Flusser [1983] 2000, 73).

Among my first camera-walks was one in September 2018, when I stepped inside the Church of São Domingos, in Lisbon, while exploring the city during a doctoral research trip. This is a space of ritual, prayer, and death; Fernando Pessoa recounts how in its place once stood the Convent of São Domingos, destroyed in the 1755 earthquake, infamous for Inquisition trials and the 1506 massacre of Lisbon’s Jews (in

Sarfati 2012, 153). Another inferno, in 1959, killed two firefighters and gutted the church, whose marble walls and columns remain singed and cracked; the burning smell persists. There is no liturgy or priests during my visit, only tourists. Without its functionaries, this place feels like a set in-between acts. Recorded hymns play, and suddenly, a loud voice makes me turn. I notice a man in a bright blue shirt sitting on a side pew, animatedly explaining something to a companion. His voice reverberates.

Walking towards the altar, I take the GoPro from my shoulder bag, extend the stick, press record, and hold it up; I begin documenting São Domingos’ interior, walking slowly as my camera records my surroundings. I trace a path around the church, under religious statues and over marble steps covered in red carpet. A few tourists glance at my camera-on-a-stick but keep moving. In this ‘camera-walk’, and those that followed in subsequent years, I walk in silence as my aim is photogrammetry. For this, moving objects are not recommended, so I avoid conversation and encourage stillness through silence. Within this public place of ritual, where my only rule is the rhythm of my steps, I foresee that my photogrammetry will be of what remains: statues, burnt walls, cracks, effigies. I do not expect any animate bodies, including mine, to persist in my model-to-be, because our movements elude the matched points that digital photogrammetry favours. After encircling the space and reaching the altar, I turn the camera off; the ‘camera-walk’ took under five minutes.

4. Ghostly Phenomena

Back in London, I place the camera on my desk. The GoPro Fusion records two separate files, one from each fisheye lens, stored in two mini cards whose content I transfer to my computer. Each of these videos is a flat circle within a black square, like a circular mirror; one also carries sound. The GoPro desktop application stitches the two spherical videos into one panoramic video, which I import into Adobe Premiere. I hand-pick frames to export as stills, towards Structure from Motion (SfM) photogrammetry calculated in Agisoft PhotoScan (later renamed Agisoft Metashape). Here, a very brief explanation of photogrammetry is useful: Professor of photogrammetry Armin Gruen explains that, etymologically, it can be understood as ‘measuring lines with light’; while 19th century photogrammetry depended on big and heavy photographic cameras and data-processing machines, even in the early 1980s digital techniques were valued by only a small minority within the photogrammetric community;

Gruen (

2021, 34–41) emphasises that photogrammetry and SfM photogrammetry are conflated but stem from distinct methodologies, whereby the latter is part of computer vision. Through algorithms establishing common points between multiple images, computer vision prioritises the production of ‘a dense point cloud supporting a captivating 3D model’ (

Aicardi et al. 2018, 258–262).

My own experimentation with panoramic photogrammetry stemmed from a desire to engage in a documentary practice that prioritises walking over looking through a camera lens. Because each panoramic image holds much information, fewer are needed for SfM photogrammetry than if I were using a conventional camera, but they must still share enough detail for the software to match points. Within São Domingos, my ‘camera-walk’ lasted under five minutes; for my first experiment, I render only the first minute (1800 frames shot at 30 fps), from which I hand-pick 51 frames and feed them into Agisoft PhotoScan (Professional).

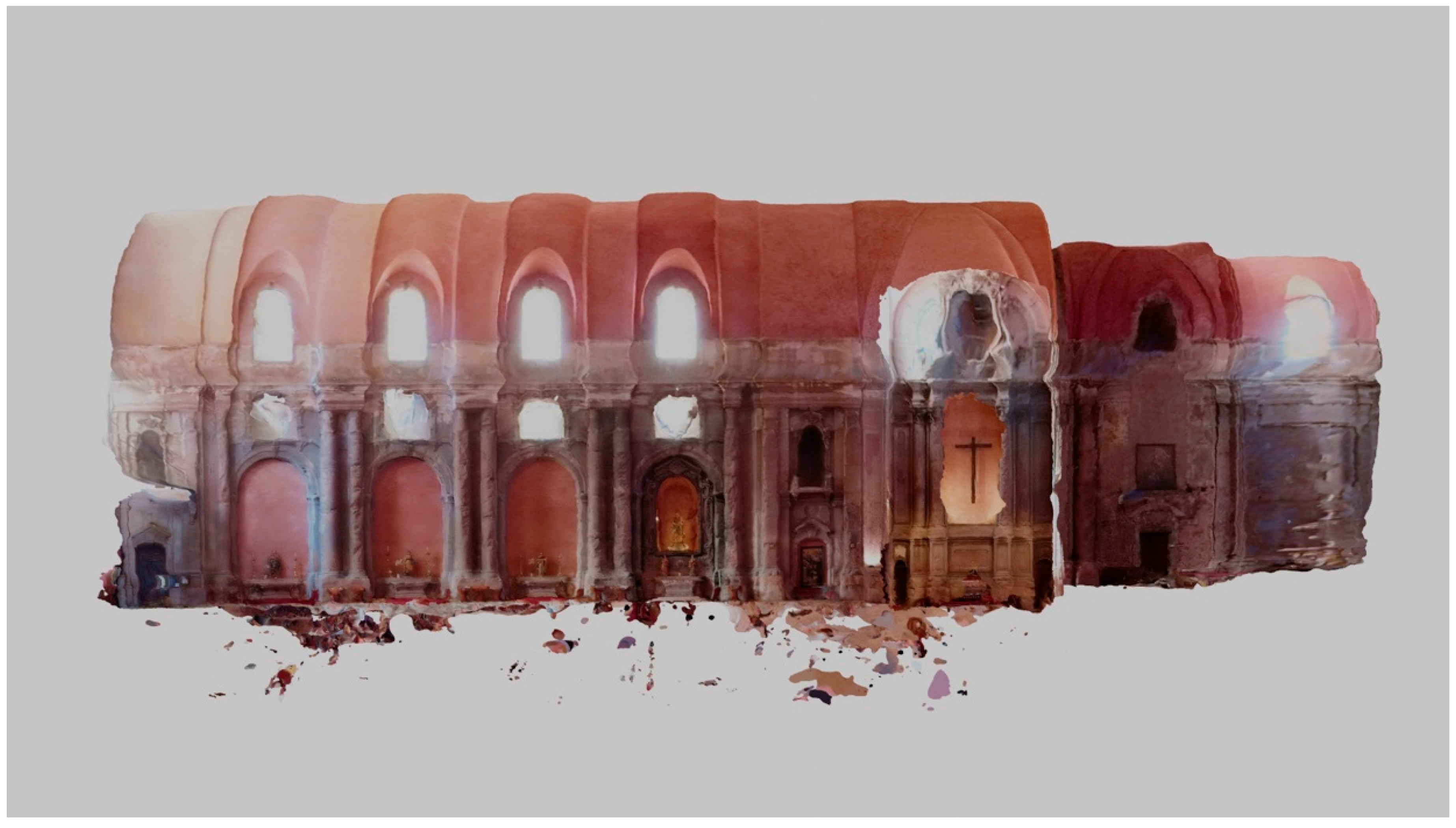

The process runs through four stages: alignment, dense cloud, surface, and texture. Though automated, each can produce different results, according to the settings that I determine. I import my 51 panoramic images into Agisoft, set alignment to medium quality, and wait while it searches for matching points to form a sparse cloud and determine the camera positions. The sparse cloud already suggests the building’s faint shape (

Figure 1), but with the dense cloud, I recognise the space of my camera-walk (

Figure 2). After the mesh and texture projection, the model appears as a fragmented, partial cast of the church (

Figure 3). The positions of the camera are marked as little blue spheres. Because the images were shot from within, the outside and the inside co-exist: the ceiling is also a roof, and the interior walls of the model are also exterior. Because my body and the tourists’ own were in motion, we are not still long enough to be enmeshed in the model’s geometry, but we affect the image by causing distortions and even holes in the floor.

Among the creams and corals of the walls and ceiling, and the reds of the carpet, a vivid blue patch calls my attention. The man in the blue shirt is

there, sitting on his pew, the first human I encounter among statues, and yet also a statue (

Figure 4). How did he get here? I return to Premiere, exporting more stills from the full camera-walk rather than the first minute only. Repeating the process—alignment, cloud, mesh, texture—I create a new, fuller model of the church (

Figure 5), but inside it, the man has faded to a blurred brushstroke (

Figure 6). Like a detective, I return to the spherical video and see him walk away while I was on the opposite side of the Church; his documented absence in the longer video appears to have diluted his earlier concentrated presence. The empty pew contests his body, and his gestures make him a moving object that the software cannot match quite as well. The man in the blue shirt partially ghosts himself, like most other humans in the church.

In this, my very first 360-video SfM experiment, the man in the blue shirt is also my first unexpected human body. He is between a ghost and a statue, but also a relic. He stayed still long enough for my camera to record him into enough frames for SfM photogrammetry to unexpectedly

ossify him as part of the scene. It was coincidence that I chose the first minute of the video to work with, while he was sitting still; coincidence, too, that I had noticed his voice enough to recognise him in the model. His stillness recalls Daguerre’s

Boulevard du Temple 8am from 1838 or 1839, where only the boot cleaner and his customer remained visible while the rest of the moving humans and vehicles vanished (

Bate 2016). The man in the blue shirt’s stillness and my own movement were necessary conditions for his apparition. Had I stayed still, there would not have been enough difference and overlap for the model to form; had he

not stayed still, he would have disappeared with the other moving bodies. Are there more ghosts in the church?

I return to the model and notice stripe patterns on the church floor, over the cracked tiles. I create more projects, some where I feed more stills into the software, and others where I take stills away. Through this intensely iterative process, I realise that using more images and generating more polygons gives me a denser and more detailed mesh, but with parts of it missing, appearing as holes. With a small number of cameras, a low polygon count, and the texture projected, what were stripes on the floor are now clearly a projection of my figure on the church tiles. There is a visible sequence of my body moving from left to right, seen from up high, as I turn my head to take in the views, and with the stripes of my top causing the aforementioned pattern that sparked my attention. The image shows me walking and curiously looking around rather than through a lens (

Figure 7). The title of this image,

Cheiropoieton, is the modern Greek word for ‘handmade’: it lexically and playfully contests the acheiropoieta traditionally revered in holy places with an accidental self-portrait ‘revealed’ in one.

What such views allow me to understand is that, within my ‘camera-walk’ photogrammetry, while more images may provide greater sculptural detail all round, my body in the centre also hides part of the image and occludes potential matching, so the detail is accompanied by gaps in the mesh. In contrast, fewer images and fewer polygons weaken the sculptural in favour of the photographic—the mesh becomes a flat canvas for a portrait. Is there a name for such artifacts ‘found’ in a church?

The polysemy of the word artifact (also spelled ‘artefact’) is of interest here: the digital artifacts of SfM photogrammetry can be replicas of other artifacts, and my model indeed contains multiple physical objects from the space—sculptures, steps, icons, a man in a blue shirt—all fused together, within a single mesh. However, looking at the various calculated versions, with their rather bulbous and turbulent shapes, holes in the mesh, indentations, extrusions, and strange smears on the texture—a word to describe these unexpected apparitions is also ‘artifact’, in the sense of the word as a feature ‘that does not correlate with the physical properties of the subject being imaged and may confound or obscure interpretation of that image’ (

Walz-Flannigan et al. 2018, 833). While photogrammetry is employed for the production of virtual replicas for heritage conservation, my own models are meltingly different with each iteration, almost resplendent in their imperfection. Author Louisa Minkin ascertains that a photogrammetry-acquired mesh will need substantial work, including assembly, retopology, and cleaning; what needs to be cleaned is digital dirt that ‘may manifest as baroque accretions or as residual contaminants. Tiny bits of geometrical grit will risk breaking your printer’ (

Minkin 2016, 118).

I recognise these contaminants within my own meshes from the São Domingos church, although their sharpness poses no risk to my own screen experience. Rather, they befit this church, with its Baroque facade, and with the Portuguese word

barrocco meaning ‘pearl’. When a contaminant makes its way into an oyster, it ‘tears up’, and pearl-like tears are themselves artifacts of pain, effigies to the many tragedies of São Domingos. For Minkin, any digital model deriving from (SfM) photogrammetry is ‘in some sense a taphonomy, a transition of remains from biosphere to lithosphere or electronic noosphere, replicating through e-currents into myriad death assemblages’ (2016, 118). Taphonomy, from the Greek ‘taphos’ (grave), is the study of processes affecting an organism after death that result in its fossilisation (

Brookes et al. 2023, 2021). A fossil is a fitting metaphor for the photogrammetric mesh—a relic, a mould, a remnant, a record; a transition from the live into a shell formed, marked, and broken.

Minkin (

2016, 122) explains that accidents and misapplications in imaging software may produce new artifacts and knowledge, and aleatory, détourned, or hijacked methodologies are familiar operational sequences in art practice. Returning to my own work, my approach is indeed aleatory in eliciting multiple imperfect photogrammetric iterations rather than seeking

the single perfect replica. Thus, my new artifacts and knowledge are afforded precisely by

not cleaning and retopologising my meshes, and I acknowledge that digital artifacts, as imperfections, are layering new knowledge over the digital artifact-replica.

Gabriel Menotti (

2021: 489) proposes a set of artistic projects enabling a critical subversion of photogrammetry’s capacities through processing low-resolution image datasets found online, whereby the blatant mismatches between the resulting replicas and their doubly removed referents demonstrate the algorithms’ generative interference on the mediation of reality. Among such projects he includes his own

Souvenirs from 2014–2015, a series of figurines deriving from online ‘found’ videos and stock footage of the Brazilian monument, Christ the Redeemer; the videos were converted into sequences of images that were algorithmically computed and 3D printed.

Menotti (

2021: 489) explains that his

Souvenirs drew inspiration from the concept of acheiropoeita ‘implying images made not by human action but rather by spiritual intervention’. This gives me a name—and yet, I created the image in 2018, and read Menotti’s text some years later. Equally, my images were not found online but shot purposely, resulting in phenomena of a Practice as Research methodology

before encountering the concept academically. Acheiropoieta were also part of my cultural experience growing up as a Greek, within a Greek Orthodox

3 milieu.

5. Discussion

How can I explain the origins of my own

miraculously found church images? The italics reflect my genuine surprise when I saw the man in a blue shirt (

Figure 5), and afterwards, my own smeared imprints on the floor of the church (

Figure 7). There are two ‘miracles’ here, in my unexpected finding of such an image, and in the origins of the image itself. The ‘finding’ element can be explained through several coinciding events, including the man in the blue shirt talking loudly enough for me to notice him; his concentrated stillness and my own movement; and the ‘camera-walk’ taking place within a church. To clarify, I did not enter a church with the purpose of staging an encounter with acheiropoieta; I was simply walking around Lisbon during a research trip, and the interior of the Church of São Domingos caught my attention enough for me to raise my camera-on-a-stick and document it. Rather than serendipity, another notion of value here is

synchronicity, whose principle ‘asserts that the terms of a meaningful coincidence are connected by simultaneity and meaning’ (

Jung 1991, 277). Synchronicity befits this occasion, because the SfM mesh is itself performing an enmeshing of the time that the ‘camera-walk’ took, so that several minutes are synchronised into a single instant, differing with each iteration.

Equally, because my practice comes out of intense and extended experimentation while ‘mis-using’ software in a non-ideal manner, it is also the product of resilience, and time is needed to extract, notice, and reflect upon the meaning of my findings, so that the initial ‘miracle’ may be re-conjured in subsequent practice, and so that it can be understood as a phenomenon. Here, I consider how Robin Nelson explains that PaR is concerned with phenomena that can be explored only through a practice rather than through a book-based inquiry alone (Nelson, in

Scott 2016, vii). My photogrammetric phenomena can also be read as an accidental auto-ethnography, which portrays the practice-researcher as a pilgrim. At the same time, what the images reveal goes beyond an artistic practice, because they elucidate how the technology functions in hiding the body in the centre. It is worth pointing out that my ‘holy’ images would not have appeared had I been using a smart phone (with a selfie-stick), LIDAR scanning, non-panoramic or spherical images, or high-end volumetric video capture. SfM photogrammetry with materials shot via a conventional camera, a studio rig, or a drone

looks away from both the camera body and any human body behind the lens; LIDAR scanning omits photography, but similarly does not ‘look back’. Part of the 360-camera’s programme is to self-erase its body from the picture, and so, had I left the camera on a tripod or worn it on my head, clipped on a helmet, the model would have been less

stamped by my presence. It is precisely the invisibility of the humans that arrange the cameras, programme the algorithms, and handle mice and keyboards to reshape imperfect models, that gives digital photogrammetry its allure of computed objectivity—while equally occluding the human as programmed-back by the apparatus. However, because I carry forth the 360-video camera with, and slightly in front of, my own body, I am also documented as I document. Rather than fulfil the digital replica that SfM photogrammetry promises, my work exposes the

animate.

The acheiropoieton is not an artifact, but a miracle that requires the disappearance of the hands of the painter, so that the icon can perform its role as divine organ—the same disappearance is required of the photographer’s hands, and the human hands involved with AI further down. To further understand the miraculous origins of such images, we may return to

Flusser (

[1983] 2000, 13)’s explanation that technical images were invented in the 19th century to make texts comprehensible again, to put them under a magic spell, and to overcome the crisis of history. Such a magic spell is recast in the kind of contemporary technological art that occludes the body in the centre, which, in the case of PaR, is also the body of the researcher.

I have explained that my ‘magical’ photogrammetric images were not the product of

seeking such magic—neither were they a didactic application of a hypothesis; rather, they appeared through the concurrence of several factors, whereby the imperfections of ‘digital artifacts’ act as layers of new knowledge. My research precisely brings forth the body of the researcher (and, potentially, the collaborator) in the centre of the work, refusing the anonymising of the artist’s labour. As noted earlier, the very title of

Figure 7,

Cheiropoieton (meaning ‘made by hand’), names its handmade origin. Remembering Minkin, rather than digital dirt affecting physical printing, my body

is the physical dirt that messes up the digital process. Because I do not correct my meshes, my SfM imperfect photogrammetry reveals the body that played with it, and with the camera, and lacks the hands-free magic of the acheiropoieton; instead, it is the hand-made fruit of a

contaminated miracle.

The question in the title—

Holy AI?—remains open. If autolographic systems promise images that make themselves, they do so within a cultural terrain already formed by centuries of veneration for self-made icons. What appears as innovation is thus also a repetition and a rehearsal, a renewed act of faith. The holiness may not lie in the algorithm but in our belief in it, along with the desire to find revelation within the machinic, the longing for transcendence permeating so many technological ‘breakthroughs’. By evoking religious iconography, this paper [hand-]draws a link between contemporary techno-magic and the magic icons of religious faith. Here, my Practice as Research functions as a form of counter-automation: it reclaims the body’s agency within machinic systems that tend to erase it. The hand returns not merely as a symbol of authorship but as a haptic instrument of inquiry: it touches and tests the tools of vision. There is an additional anxiety that the question mark after Holy AI carries: writing on Generative AI and Large Language Models,

Nikos Askitas (

2025, 12) notes that, as it becomes harder to distinguish between human- and machine-generated content, the value of authenticity declines, and ‘trust in quality (and the signalling function of effort) begins to erode’. While Askitas refers to texts such as abstracts, cover letters, and policy memos, there can be a similar distrust in images: without the dating of the particular image in 2018, before generative AI technologies were accessible, could my ‘miracle’ images today also be mistaken for (and distrusted as) AI? Under this light, the struggle of AI systems to ‘gain faith in their reality’ (

Chesher and Albarrán-Torres 2023) puts

any image under a shroud of doubt.

If AI’s autolography promises effortless revelation, the cheiropoieton demands friction; it makes visible the ethical and material conditions that permit the ‘miracle’ to occur. By situating digital photogrammetry between the sacred and the computational, I propose that every mesh, every fragment, and every smear constitute a layered relic of bodies that once moved, breathed, and paused in front of the lenses. These artifacts insist that digital imaging cannot escape the human but remains haunted by touch and gesture. The ‘ghost’ in the church and the burn marks on marble perform the same act of persistence: the refusal of disappearance. This refusal also offers a curatorial ethics: to present such images is not to demonstrate technical mastery but to stage a dialogue between apparition and apparatus.

Ingold finds ‘the whole AI business’ to be built upon a faulty notion of intelligence in purely cognitive, information-processing terms; for him, intelligence is firmly ‘grounded in the perception and action of living beings, moving around in and perceiving their environments as they go’ (in

Schapira 2019). My photogrammetric relics, produced on foot, form part of an argument against the seamlessness of generative AI, foregrounding instead the steps, the marks, the

stitches, even, of effort. Unlike the unattributed miracles of generative AI, what emerges is a practice of care for the people who participated in the making of such images. Care,

Ingold (

2019, 665) reminds us, shares an etymological origin with curiosity, and research is ‘a way of living curiously: that is, with care and attention’. What my photogrammetric relics make visible is precisely what autolography works to conceal: while the latter depends upon the fantasy of images that write themselves, my work exposes that images are always contingent, co-produced, and marked by the frictions of practice. The ghosts in the church and the smears on the tiles return the body to the centre of image-making, a situated encounter rather than an automated miracle; it involves attending to things, to people, to ideas, to literally and metaphorically ‘looking around’ with curiosity and care. It is a reminder that the labour(s) of walking, witnessing, handling, creating, and conversing cannot be erased. In the context of this practice, care is not only an ethical orientation but a material condition of the image itself.