Global corporate and commercial entities which control, market, and monetize the digisphere have largely subsumed the role of building infrastructures for communications and transactions, thus regulating and sustaining geopolitical systems of power. These corporate entities operate as forms of soft power. But in the process providing structure, information and the means of knowledge production, they end up reproducing asymmetrical systems of power between the Global North (that owns and controls these platforms and their networks) and the Global South (that is disproportionately affected by the exploitation of their resources and subsequent environmental impact). Embedded within these systems of power is a new form of symbolic authority that restructures what psychoanalysts have called our unconscious minds. This is not to say that the unconscious of old—the one that served as both a repository for our unbridled passions and a control mechanism—has disappeared. It has given rise to a new type of unconscious, a digital unconscious, thereby reestablishing authority as a control mechanism that is inaccessible to individual subjects, and thus, continues to be driven by its own destruction (what Freud called “the death drive”).

Since Sigmund Freud’s 1915 essay (of the same name), the unconscious has been loosely understood as a repository of thoughts, impulses, and traumatic experiences to which we humans remain unaware even if these inaccessible forces deeply influence our behavior and the way we perceive the world (

Freud [1915] 1989). Unsatisfied with his original definition, Freud would continue to refine his description of the unconscious, associating it with latency, déjà vu, and dream-work—where the dreamer would recall some information that escaped his or her waking or conscious perception. The unconscious, therefore, produces an internal rift between what we know about ourselves and what remains hidden within, and therefore, to us. As subjects we cannot completely know ourselves, since we often end up doing or saying things we did not intend or anticipate. In Ego and the Id (1923), Freud added yet another dynamic to the unconscious, that of a self-regulated or automated internal mechanism of repression (

Freud [1923] 1989). Seeking to distinguish the unconscious from what he considered to be the unruly natural depths of our unstructured animalistic instincts, Freud postulated that the unconscious is not to be confused with the id, even if, as he explained, “what is unconscious in mental life is also what is infantile” (

Freud [1900] 1989, 210). Instead, the unconscious functions by internalizing authority and automating a set of social rules (the Law of the Father or the symbolic order), and as a result, represses the “lower passions.” The unconscious may be full of contradictions (wild emotional impulses, baseless fears, and repressive forces) but it is also a control mechanism. It is no wonder that digital platforms—requiring uniformity, reliable protocols, secure transmissions and proprietary algorithms as well as an enormous database about human desire and impulses—would gravitate toward an unconscious model of control, or more specifically, the ideal of automating impulsive actions and reactions.

It is this automated system of repression and control that allowed Jacques Lacan to reimagine the Freudian Unconscious in terms of a rather complicated feedback loop. He famously claimed, “the unconscious is structured like a language” (

l’inconscient est structuré comme un langage), governed by rules and the social and symbolic world we inhabit. Desire, feelings, and even those base impulses are profoundly shaped by such structures. Yet as Félix Guattari points out, Lacan’s is no ordinary language: it is a mathematical, and therefore, abstract and universal one (9). Similarly,

Liu (

2011) has convincingly argued that Lacan refashioned the unconscious to match the dictates of postwar Euro-American cybernetics—birthed at MIT and Bell Labs under the auspices of the military-industrial complex. And as Seb Franklin points out (

Franklin 2015), in the 1950s “cybernetics and psychoanalysis emerge as a zone of exchange,” allowing “the computer and the unconscious to become thinkable as doubles of each other” (144, 142). The unconscious in the age of digital or computational media, thus, generates this collective orientation. However, it is a collective framed by binary logic—an orientation that is stimulated and triggered by neural networks, circuits, and combinatory rules. Thus, inherent within the digital is a notion of the collective that is driven by binary or oppositional logic, which often manifests itself as side-taking (likes and dislikes, for or against, either/or, yes or no). This binary systems’ logic, maybe external to the collective (the human user) much like language and the unconscious are for Lacan, but it is internalized by individual humans, affecting the way they interact with each other, and even how they process experiences and memories. The externalization (we could even say the outsourcing) of memory and with it perceptions of the world from the individual’s interaction between the sensuous environment and inner workings of his or her psyche to data processing begs the question: are we still talking about an unconscious or something more like a nonconscious (or unthinking) subjectivity when we refer to the individual user, consumer, or conscious self as it relates to the digital? A subject (whether human, digital or both) that is fed information or stimulated by some type of input, and repeatedly conditioned to see and think about the world in a particular manner, is better described as what Liu calls the Freudian robot. These are subjects whose memories, thought processes, and desires are measured, analyzed, and made accessible as data, and thus they are compelled to repeat. Repetition is generated by external market-driven analytics that leave us caught in a human–machine feedback loop.

Similar to the Freudian unconscious, digital platforms and networks are infamously black-boxed, meaning their operations (inner workings) are made invisible to the average user, including information about them—information used to generate data profiles (see Bruno Latour’s

Pandora’s Hope,

Latour 1999). Yet, what remains hidden in the digital unconscious is not related to the internal workings of our own psyche, rather it is more about the amassing and processing of information about us that can be sold and used by third parties (political campaigns, marketers, governments) to stimulate and control our behavior and our responses. In his attempt to rethink consciousness in the age of twenty-first century media, Mark B. N. Hansen, proposes that subjectivity is no longer individualized but distributed in a network. This subjectivity, according to Hansen, “may be ‘anchored’ in a human bodymind, [but it] does not belong to that bodymind … [F]ar from constituting the interiority of a transcendental subject, this subjectivity is radically distributed across the host of circuits that connect the bodymind to the environment as a whole, or, more precisely, that broker its implication within the greater environment” (

Hansen 2015, 253). Consciousness, for Hansen, is thus “no longer at the center of the present of sensibility” (25); it is, therefore, only as affect or sensibility that we (as humans and non-humans) can collectively create new relations that cannot be so readily controlled.

As a result, with Hansen’s distributed subjects (like Liu’s Freudian robots) consciousness is reduced to a game in which each person is programmed to play, and each move is not only anticipated (by game theory, algorithms, and data analytics) but cannot help but benefit the existing socio-economic order. Liu writes: “Lacan demonstrated how the unconscious instead of the speaking subject, does the thinking and plays the game of chance according to given combinatory rules” (317). The digitization of the unconscious, based on information theory, however, “seems to function today (in league with Behavioralist and Pavlovian theories)” as some form of “dichotic analysis and binary reductionism” (

Guattari [1979] 2007, 13). What goes unquestioned in both Freud’s and Lacan’s iterations of the unconscious is just whose rules and authority are we talking about? When we think about the digital unconscious do we refer to some abstract (or even mythical) notion of symbolic paternal order, or is it contingent on specific geopolitical forces? Similarly, it is unclear what “environment” Hansen has in mind as he applies it to twenty-first century (computational) media, especially when the maintenance and extension of said media threaten our physical environment by draining natural resources and polluting the planet with its byproducts.

Bruno Latour credits Freud for acknowledging how “human arrogance was deeply wounded by scientific discoveries: first, by the Copernican revolution that drove humans out of the center of the cosmos; then, still more deeply, by Darwinian evolution, which made humans a species of naked monkeys; and, finally, by the Freudian unconscious, which expelled human consciousness from its central position” (Facing Gaia 79). But Latour questions why Freud insists on reading these discoveries in terms of “narcissistic wounds,” rather than seeing how such discoveries liberate humans from what are, otherwise, self-regulated repressive systems of power and domination. Why do we insist on the subject even if it is only a node in a network? This anthropocentric fixation on our narcissistic wounds, on mechanisms of repression, and ultimately on control (with all their unconscious rules and states of play) appears to be just another form of arrogance, or perhaps just another iteration of the death drive.

For Latour, the problem stems from the fact that we are not confronting our present relation to the Earth, a relation which has profoundly mutated, becoming increasingly volatile, unstable, and unpredictable. And twenty-first century media that requires so much of the Earth’s resources and energy seems incapable of reversing this trend. Rather than address what is right in front of us (the Earth is becoming human-unfriendly) in a realistic and thoughtful manner, we still present “the climate crisis” as something to come, or something that can be managed and controlled. That is, we tend to envision a “futuristic future” that the Pollyanna see far off in the distance and reactionaries and climate deniers can dismiss as science fiction. Modern time is, for Latour, similar to the unconscious itself in that it is “profoundly atemporal”: on the one hand, we moderns create narratives based on magical thinking where we transcend our current reality with “infinite enthusiasm for the future,” without actually taking the necessary steps to insure any future at all, and on the other hand, we indulge in “deep despair over the errors of the past” (

Facing Gaia, 243). Hence what Freud once considered a repressive apparatus, has now become an operation of denial. Stefan Aykut and Amy Dahan warn us that if we continue to act as if we can treat the Earth as a territory that can be governed or managed by carbon credits or any other “calculated negligence,” we are not facing up to our present relation to the biosphere. (We belong to the Earth, not the other way around) (

Aykut and Dahan 2015). As they explain, there is no effective way to “govern the climate” or treat CO

2 as if it were another case of pollution.

Thus, I would like to argue that what remains unconscious are not the mechanisms of control, the infinite calculations of power, or the data about the radically changing world around us (the signs are visible everywhere). Rather, what seems to elude us is what Freud once called the “Oceanic Feeling,”

1 which he himself uncomfortably described as a deeply religious feeling of oneness or interconnectedness with the world at large—a feeling that he could not help but turn into the death drive (

Civilization and Its Discontents). I am not interested in religion, or spirituality per se, but in this sense of interconnectedness, what Latour might call a sense of being Earthbound (in a way that can be decoupled from the death drive). Without such a sense, we are, as Latour puts it, “totally unequipped to approach the material conditions of our atmospheric existence” (

Facing Gaia, 244).

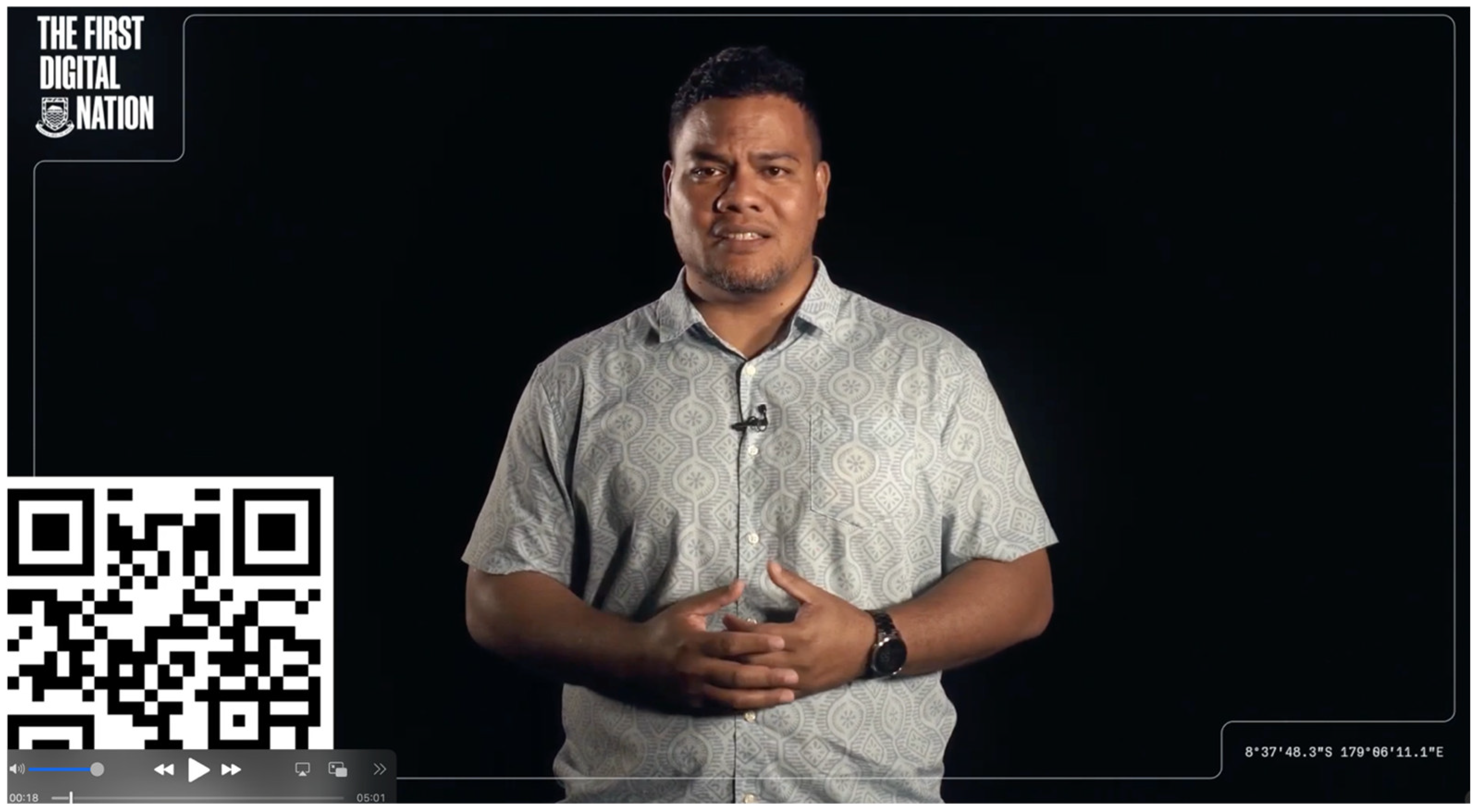

In what follows, I will examine how recent pleas by the Tuvaluan Minister of Justice, Communication, and Foreign Affairs (Simon Kofe) to the United Nations Convention on Climate Change reveal that denial has replaced repression as the key mechanism of the digital unconscious, allowing twenty-first media to offer itself as pharmakon (both poison and a remedy or at least a distraction) to those twenty-first century crises that nineteenth-, twentieth-, and twenty-first-century media continue to advance. Tuvalu and its strategies to combat climate catastrophe can be seen as emblematic of larger political, environmental, and digital power dynamics that are set on environmental destruction. The small low-lying Polynesian nation of Tuvalu (located in the Pacific subregion of Oceana) is considered to be the country most at risk of disappearing due to projected rising sea levels. Scientists at the University of Hawaii Sea Level Center, the NASA Sea Level Change Team and Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology have shown that sea levels have risen in Tuvalu by 14 cm since 1993 and will rise 19 more centimeters by 2050 (

Fournier et al. 2022;

NASA Sea Level Change Team 2023;

Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology 2025). Tuvalu has already seen and will continue to experience increasing flooding. According to NASA, “Tuvalu will likely experience more than 100 days of flooding every year by the end of the century” (

NASA Sea Level Change Team 2024).

The fear caused by this immediate threat of climate catastrophe has provoked Tuvaluans to both appeal to the global community to enact real policy changes to upend this looming threat and also embrace twenty-first century media as a means of salvaging vestiges of Tuvaluan heritage. Appeals to the global community draw on the fact that we are all Earthbound. Yet Simon Kofe has eloquently pointed out that our relation to the Earth and to the climate crisis does not affect everyone equally; low-lying island nations are the first to feel the impact of the global climate crisis. Nonetheless, it is the appeal to the underlying connection of all planetary life, which stands in opposition to the call for the preservation of Tuvaluan’s unique and threatened cultural heritage and cultural identity, that interests me most. The over-arching sense of oneness needed to combat climate catastrophe is often ironically coupled with a plea to sustain individual national and cultural subjecthood. This coupling produces what I see as three key paradoxes. The first, and most obvious one, is that the digital technologies that archive, document, and maintain cultural histories under threat of extinction are the same ones putting them into crisis by negatively impacting them in the first place. The second concerns the intrinsic connection of the global community to older understandings of subjectivity and narrative identity (particularly the nation state) as rooted in notions of the commons (what we hold in common, as in values and resources) and individual property (ownership of land, and ownership of oneself) And lastly, the digital archive requires that we differentiate the notion of memory from storage—that is, documentation is not the same as memory. In what follows, I would like to address why I see some of the latent or vestigial structures of the unconscious and of subjectivity itself now becoming obstacles to the Earthbound—to those of us who would like to establish some form of interconnectedness to the planet upon which we live. If we are to engage in a new form of world-building, we need to let go of the idea that we are somehow ruled and regulated by the vestiges of unconscious structures that are literally killing us.

1. Denial as Death Drive

Writing about how the climate apocalypse is connected to the history of the Marshall Islands, Srećko Horvat links the current changes to the global environment back to the onset of the nuclear age. He explains that the sixty-seven nuclear tests conducted in the South Pacific alone between 1946 and 1958 physically changed our relation to the Earth, setting off what Clive Hamilton argues is “an increasingly more ‘defiant’ Earth that is not indifferent to human actions” (

Hamilton 2017, 113). More than some sinister return of the repressed, nuclear fallout (that has been seeping into the ocean since then), and the cybernetic and digital infrastructures (with their supply chain logistics, drain on the electrical grid, and exponential use of Earth’s minerals), have exposed the tension between those humans who insist on defying the fact that they, too, belong to the Earth by falling back on old practices of domination in a model of zero-sum gain, and the Earth, that is responding to such practices.

With the imminent threat of climate collapse, many island nations and coastal cities are facing permanent territorial loss. As a consequence, the leaders of the Maldives, Kiribati, and Tuvalu have become increasingly engaged in diplomatic forms of climate activism, challenging the current geopolitical discourse by drawing attention to the threat of rising sea levels, the acidification of oceans, and the increasing intensity of tropical storms. But the inevitable disappearance of their entire homelands raises other questions related to their cultural heritage and their attendant legal standing in international law and maritime agreements—all of which hinge on their status as a defined territory with a permanent population. While international law is equipped to deal with stateless people, it still operates on the Westphalian doctrine of state sovereignty—a doctrine that Latour describes as a “monstrosity invented to put an end to the wars of religion” by erecting a worldwide network of territories with definable borders (Facing Gaia, 190). Nation-states with dissolving borders, dislocated climate refugees, and possibly without actual territory, present a conundrum to such international law.

Yet this is not the only problem facing places like Tuvalu, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Maldives, and the Federated States of Micronesia. They are what Maina Vakafua Talia (

Talia 2025) calls “weak actors,” meaning that their cultural, political, and economic survival is often pitted against the vested interests of superpowers like the United States, China, India, the European Union, and the Russian Federation (the world’s top five carbon emitters, accounting for 60% of all greenhouse emissions in 2023).

2 These mega-polluters, however, control the discourse: they have consistently moved net-zero target goals from 2030 to 2050, or, in some cases 2060 or even 2070; broken signed agreements, such as the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Paris Accord (in 2017 and again in 2025); or altered the wording of final United Nations declarations or agreements, replacing terms like “phasing out” with “phasing down,” e.g., when China and India used such language with respect to their use of coal, and more recently when petrostates such as the UAE and Saudi Arabia used the same toned-down phrases with regard to fossil fuels. By 2050, Tuvalu’s land mass is projected to be fifty percent underwater. It is in this context that small island nations threatened by extinction have had to adapt new strategies—often using media tactics to appeal to a wider global audience. One such example is the

Te Ataeao Nei or Future Now Project launched by Tuvaluan climate activists that responds to global indifference to confront what the former Tuvaluan Minister of Justice, Communication and Foreign Affairs, Simon Kofe, calls the “impending reality of the people of small island nations.”

3 It is Kofe’s series of interventions at the United Nations Climate Change Conferences that I will focus on here, as they touch upon the topics of denial, and how the digital has become entangled in the social and environmental survival of small island nations.

In 2021, Simon Kofe delivered Tuvalu’s address to the United Nations Climate Change Conference COP 26 (Glasgow), from the far end of Fongafale, the main islet of the capital Funafuti (See

Figure 1). At first, Kofe appears to be standing at a podium with the Tuvaluan and United Nation’s flags hanging in the background, wearing a suit and tie, but as the camera pulls back, we see that he is knee-deep in sea water. (See

Figure 2).

It is at this point he declares: “We will not stand idly by as the water rises around us, we are not just talking in Tuvalu, we are mobilizing collective action at home, in our region, and on the international stage to secure our future.” The public broadcaster, TVBC, that shot and telecast his speech, frames him in front of a concrete structure used to house American artillery guns during WWII. While the bunker once stood on solid ground, coastal erosion now places it about twenty meters from today’s coastline. This video-broadcast gives an image both to the current impact of climate change on low-lying small island nations and the projected future of some of the most populated areas on earth, while simultaneously promoting diplomacy—a form of diplomacy based on the Tuvaluan values of “communal living systems, shared responsibility, and being a good neighbor.” The idea, according to Kofe, was to “motivate other nations to understand their shared responsibility to address climate change and sea level rise to achieve global wellbeing.”

While the image of a sinking nation garnered international attention—the broadcast was viewed by 2.1 billion people, Kofe was covered in 173 major global publications, and he trended on TikTok and Twitter—it clearly did not translate into the rather optimistic vision of the global community coming together to confront the devastating realities of climate change.

4 Instead, since then the courts and the media in all of the world’s leading polluter nations have gone out of their way to demonize climate activists, their protests, and their various acts of civil disobedience within their own territories. By 2022, Australia, the United Kingdom, European nations (such as Germany, France, Sweden, and the Netherlands), as well as the US began to crackdown on climate activists threatening them with heavy prison sentences, and in some cases labeling them as terrorists, at the same time as their leaders lectured other countries about the right to protest and the rights to clean air and water.

5In 2022, Kofe returned to COP 27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, this time with a more pragmatic proposal, given the world’s inaction on climate change. In his taped video address, Kofe remarks on how nothing had happened since his previous attempt to persuade global leaders to act collectively and responsibly, and noted that Tuvalu “cannot wait for the world to get its act together,” since temperature rise projections remained well above 1.5 degrees Celsius, leaving him with “no other choice than to become the world’s first digital nation.” The city of Seoul and the Island of Barbados have followed suit with their own intensive documenting, scanning, and augmented reality projects hosted on the metaverse.

Similar to the COP 26 address, Kofe stands at a lectern in a suit and tie, with the same two flags waving behind him. (See

Figure 3). But this time it is clear that he is standing on the beach. As he announces that Tuvaluans have “no choice but to become the world’s first digital nation,” we start to notice various anomalies in the image: the Tuvaluan flag unnaturally moves as if it were a glitch in the matrix, and flotsam suddenly appears and disappears on the beach before him. It is at this point that the camera starts to pull back, revealing a tapestry of movement in the background. In stark opposition to compression-decompression systems used to transmit and archive video—which compress video signals by removing any noise that appears to the algorithm to be extraneous—this video renders visible the multiple processes of mediation. This small island appears as a patchwork of images all scanned at different times but stitched together in some Frankensteinian manner.

As Kofe continues to address the UN, he recounts: “our land, our ocean, our culture are the most precious assets of our people, and to keep them safe from harm no matter what happens in the physical world, we move them to the cloud.” Ironically, there are no clouds in this image, only a blackened sky. Kofe’s is no longer a gesture of urgency, nor an appeal to immediate action; rather, it is one of salvaging vestiges of memory from the physical world in a digitized form. As the camera pulls farther and farther away from the podium, the video becomes much more chaotic, revealing an assembly of inconsistent (glitching) images sutured together. While we hear Kofe telling us that “piece by piece we will preserve our country,” we see a mélange of appearing and disappearing shadows, trees, plots of land, parcels of sand, rocks on the beach, splatches of water, and an increasing number of birds that circle, seemingly suspended in a pitch-black sky. (See

Figure 4).

The constant rendering and re-rendering of these images demonstrate how the small islet upon which Kofe stands has been scanned and rescanned in various gridded zones, giving the impression that this digital archive has only been tenuously stitched together. Rather than seamlessly present the islet as a single unified image, this visible suturing of ephemeral images makes the island appear ghostly, as if it were being filled in and erased at the same time, disappearing into the virtual. (See

Figure 5). These are spectral images that suggest, as Kofe does, that the only future for Tuvalu, and eventually the Earthbound, may be in the metaverse. Yet the flickering quality of the images and the looming desolate sky make even this possibility doubtful, for the metaverse requires resources and a great amount of human input to run.

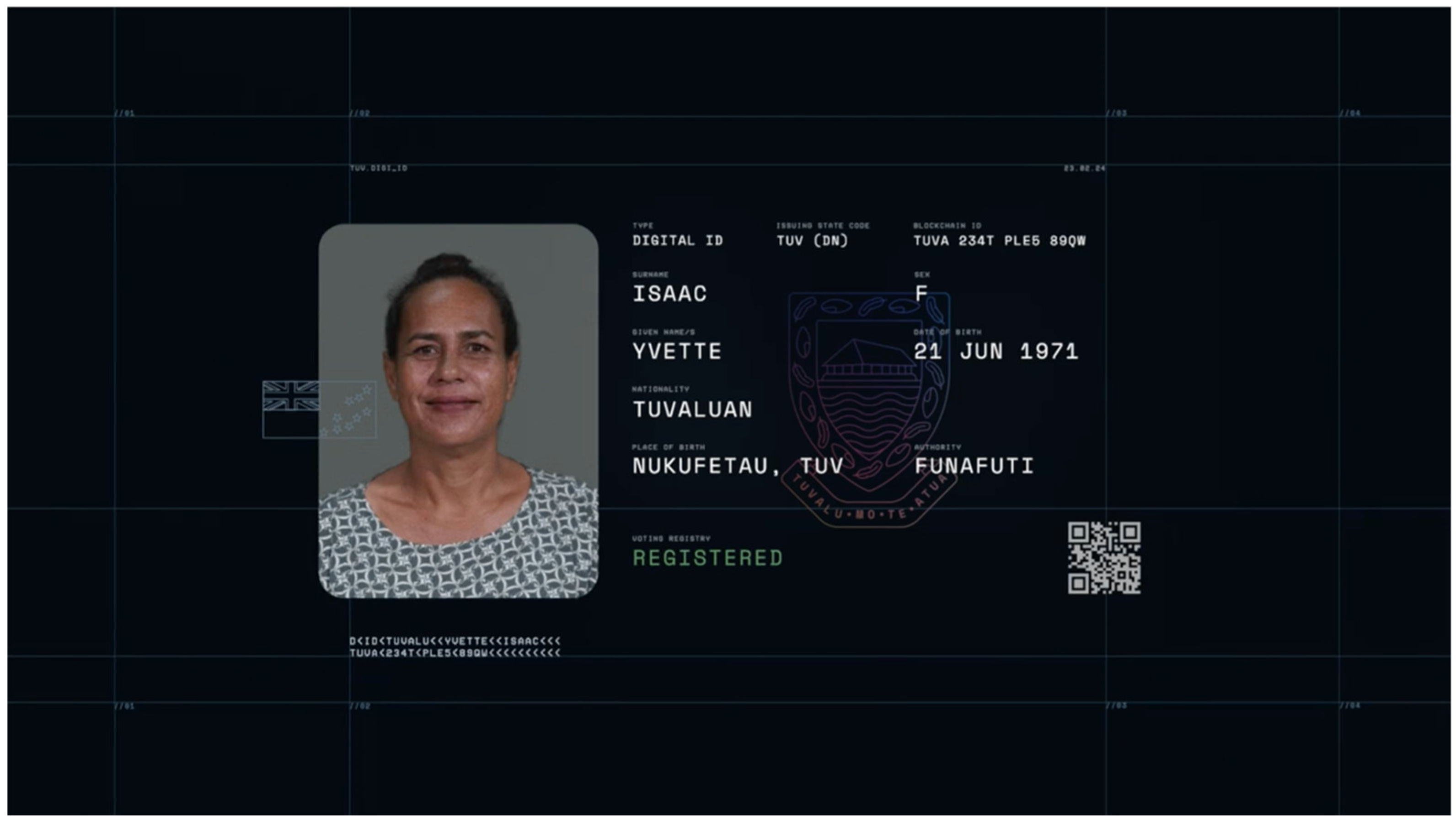

In 2023, Kofe presented the Future Now Project at COP 28 in Dubai: a project that provides digital documentation, scans, maps, and 3D LiDAR renderings of all Tuvalu’s 124 islands and islets, so that Tuvalu as a place and a culture can be experienced virtually and communicated to future generations. (See

Figure 6).

Beginning by asking the audience to “imagine standing on the last piece of land you can call home, only to watch it disappear beneath your feet,” Kofe now appears before an empty black background with a QR code in the bottom left-hand corner and latitude and longitude coordinates in the bottom right. He reminds us that “it is not just the land we stand to lose, it’s our identity, our nationhood.” This video is not just a warning, nor is it a call for solidarity, instead it challenges existing laws regarding the recognition of the nation-state as having a “defined territory” with a “permanent population,” and proposes the digital nation as legal territory. The Future Now Project encompasses the scanning of existing territory and the creation of digital passports (stored on blockchain) to track and allow the Tuvaluan diaspora to continue to communicate and conduct elections and referendums. (See

Figure 7). But it also becomes an archive, allowing citizens to record individual memories for future posterity, and preserve the Tuvaluan values of

kaitasi (a sense of oneness and interconnectedness),

fale pili (concern for one’s neighbor),

aava (respect for community), and

alofa (caring for others).

It is not without some irony that this project won the Drum Awards for Marketing at APAC (Asian-Pacific) 2023. Yet, in order to produce such a project, the climate activists needed to strengthen their communications infrastructure by laying submarine cables to link Tuvalu to the cloud. And it is in the cloud where a database of all its citizens now resides, alongside an archive of scanned objects each citizen chose to put on Tuvalu’s digital ark. (See

Figure 8). Under these circumstances, the practice of forensic mapping and the archiving of cultural heritage gives presence to what will become underwater nations. In sharp contrast to Benedict Anderson’s notion of an “imagined community,” or even Moonsun Choi’s concept of “imagined online communities,” the emergence of digitized or 3D-mapped states as “material” evidence for disappearing territories, peoples, and cultures suggests that somehow virtual documentation can help settle vestigial territorial and cultural claims (such as fishing territories and cultural heritage) (

Choi 2016;

Anderson 1990). More problematically, the cloud becomes the “site” of the “nation-state” (

Rothe et al. 2024). I would now like to turn our attention to address the tensions between unconscious structures of identity and authority and the many attempts by climate activists and small-nation peoples to bring visibility to our Earthbound interconnectedness—beyond the promise of twenty-first century media.

2. Communicating the Anthropocene

Sophisticated technologies help to sense, calculate, analyze, and disseminate information about climate change, but they also negatively impact the environment, since they require a substantial investment in digital infrastructures as well as vast amounts of energy consumption, contributing to global warming. Today it is very difficult for any nation wishing to participate in the global economy to remain off the grid. Even though Tuvaluans have had to invest in building and sustaining digital infrastructures with the construction of undersea telecommunications cables and global satellite links, they remain relatively disconnected from the digital world—with less than 50% of inhabitants having access to mobile communications in 2024. Recognizing this as a disadvantage, the Tuvaluan government has been investing in what they call a “digital transformation,” which includes providing its citizens with an accessible connection to the internet, internet awareness training and education, as well as the building of a new workforce skilled in e-commerce, cyber security, and internet banking.

6 Major investments in these networked infrastructures and cloud technologies come with their own complications: they are deemed both essential to participation in the knowledge- or information-based global economy and they are in direct conflict with climate activists that seek to reduce our global carbon and water footprints.

7 As Benjamin Bratton, succinctly puts it: “We are taking a high-stakes risk with the development of smart grids and the energy appetites per terminus they will enable” (

Bratton 2015, 29).

But these are risks weak actors in the global economy are forced to take, since transnational actors like Meta, Google, Amazon, and Starlink have already succeeded in shifting the global economy from one of extraction and production to an information or cloud economy,—which ironically is far from being ungrounded, since it requires more and more extraction of minerals, coal, oil, and gas to keep server farms and data centers running. As Jack Goldsmith and Timothy Wu point out (

Goldsmith and Wu 2006), beneath “formless cyberspace” rests “an ugly physical transport infrastructure: copper wires, fiberoptic cables, and the specialized routers and switches that direct information from place to place” (73). In other words, cloud computing that engages in comprehensive data capture, surveillance, remote storage, and metadata analysis, is dependent on robust physical and global infrastructures that link data centers and swarms of orbiting satellites to individual users. What is becoming less grounded or Earthbound are the transnational cloud computing companies themselves—e.g., Google, the Alibaba group, and organizations like the US National Security Agency (NSA). Although headquartered in the United States, Meta, Google, Amazon, and X (formerly Twitter) need data centers located across the globe, often in hidden or remote areas with ample and unregulated water and energy supply.

A single data center is said to use as much energy as a mid-size American town. In 2008, consultants at the global management company McKinsey argued that “the fastest-increasing contributor to emissions will be growth in the number and size of data centers, whose carbon footprint will rise more than fivefold between 2002 and 2020” (

Boccaletti et al. 2008, 2). And with the recent boom in AI technologies, the consumption of energy used by these data centers is projected to grow again exponentially. In her recent book, Empire of AI: Inside the Reckless Race for Total Domination, Karen Hao (

Hao 2025) outlines what she calls the scale-at-all-cost development of AI (and the growing data centers that support it), which demands not only the fulfillment of its ever growing energy needs—requiring that we turn to coal, methane gas, and other dirty energy sources to power the grid—but also allows AI companies to act with impunity—as evidenced in the ten-year moratorium on state regulation of AI folded into the recent US Congressional reconciliation bill H.R.1—One Big Beautiful Bill Act of 4 July 2025.

8 As a result, local communities and small island nations like Tuvalu have been suffering the negative effects of such operations—toxic waste emitted by these data centers, extreme weather events, rolling blackouts, and rising sea levels. The material (environmental and geopolitical) impact of these transnational actors has been obscured by the fact that the “digital environment [is often treated] as an abstract projection supported and sustained by its capacity to propagate the illusion (or call it a working model) of immaterial behaviour” (

Kirschenbaum 2008, 11, original emphasis).

Kofe’s initial appeals to the global community were attempts to draw our attention to the fact that the Earth and the Earthbound have finite resources and that the pace at, and manner in, which they are being exploited is leading toward our own finitude. It was an appeal to a global conscience, but also a reminder that there are physical and material limitations to Earth’s resources that impact all life on the planet. Tuvalu, however, holds a tenuous spot vis-à-vis digital technologies, since it relies on the internet as both a source of income—the Tuvaluan government sells its domain name (.tv) to large corporations like Fox News, MSNBC, Amazon Prime, and Netflix—and as an archive—the Future Now Project is hosted on the metaverse. Yet this does not mean that Tuvaluans are equally responsible for the climate crisis we are collectively facing. As Sean Cubitt puts it (

Cubitt 2017): “Indigenous people have borne the brunt of the digital boom, and gained least from it. The global poor suffer far more from pollution and environmental loss than the global rich; and much the same is true for the local poor and the local wealthy” (14). Thus, Kofe’s shift from appealing to collective global action at COP 26 to announcing Tuvalu’s move to the metaverse at COP 27, raises another set of interconnected problems.

3. Cloud Nations

For many Tuvaluans, the real issue in creating a digital copy of their small island nation-state is “protecting their sovereignty regardless of future environmental changes” (

Woods 2024, LSJ Online). Turning to the cloud and the metaverse as a nation-state’s link to its (former) territory presents us with an important challenge to traditional notions of sovereignty. Aside from the fact that an exclusively cloud-based nation-state would mean that any sense of belonging would become remote (people would become landless citizens of a state that no longer exists), the state itself could possibly become remotely controlled by foreign entities. Governed by contractual relations with users rather than citizens, cloud computing companies and platforms such as the metaverse (hosted by corporate entities that often bear trademark and intellectual property protections) appear as unlikely spaces for sustaining human rights and upholding the legal standing for individuals and individual nation states. International law is now grappling with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

9 that grants all people a nationality as well as the creation of what Rosemary Rayfuse (

Rayfuse 2010) calls a deterritorialized state or what Maxine Burkett calls the nation ex situ—both of which would afford “a status that allows for the continued existence of a sovereign state in perpetuity” (

Burkett 2011, 346).

But how do we stabilize the unstable, that is, how do we ensure the endurance of such nation-states and cultures in perpetuity when, as climate scientists argue, the Earth is wreaking havoc on human communities on an ever-larger scale? And perhaps more importantly, how do we ensure the perpetual existence of a state that relies on a proprietary platform outside of its own and possibly international jurisdiction? Bratton muses: “What if effective citizenship in a polity were granted not according to categorical juridical identity, but as a shifting status derived from any user’s generic relationship to the machinic systems that bind that polity to itself” (26)? Social and political realignments from public to corporate alliances in the cloud computing era challenge conventional (or should we say, legacy) notions of citizenship, rights (including human rights), property, territory, and notions of cultural heritage. While the rights and laws based on legacy notions of sovereignty—legal systems, social contracts, human subjectivity, birthrights, psychology, property, various forms of expression—are currently being put into question, what remains in place are control mechanisms, the algorithmic symbolic language (the digital unconscious) which is based on a set of rules and instructions that have become increasingly more automated and unknowable (at least to humans). Automation, however, undermines conventional notion of human subjectivity (Hansen, Liu), by, as Mark Andrejevic puts it, reconfiguring “the subject as a figure of lack” (17), and only further threatens the wellbeing of various forms of life on this planet (

Latour 2017;

Hamilton 2017;

Horvat 2021) (

Andrejevic 2020). As Alain Pottage has argued (

Pottage 2026), cloud computing has “acquired a peculiar existential self-sufficiency. It became an autonomous and paradoxically immediate medium, which conditioned the existence of the elements and entities that it relayed, varying their agency according to the changing informational state of the apparatus” (13). In this regard the cloud not only problematizes the juridical and geopolitical understandings of space, which were established on a concrete notion of land that can be owned (enclosed) as property (nomos), but it also forms and polices a new named territory, cyberspace. The infamous Nazi political theorist, Carl Schmitt (

Schmitt [1950] 2003), defined nomos as “the Greek word for the first measure of all subsequent measures, for the first land appropriation understood as the first partite and classification of space, for the primeval division and distribution” (37). But, as Bratton points out, the cloud and the infrastructures upon which it rests “may establish that there is no real nomos after all” (43).

For Pottage, cloud computing and information-based space unsettles “the very jurisdictional logic of Euro-American law: the idiom of bounding, delimiting, and reifying through the force of legal enunciation” (4). Yet this move away from a jurisdictional logic grounded on the notion of appropriation and reappropriation of land (what Schmitt called

Landnahme), does not undermine property rights, as historically the laws of the seas once did. (Since Roman times, the seas fell into the category of things “common to all”). Instead, the metaverse is not in the commons nor is it “common to all.” Even if information and the electrical infrastructure upon which the cloud relies cannot be enclosed as land (like the sea), it constitutes a new category of property, and a new sense of space or territory that can be controlled, owned, and mined for extractable value. The irony is that while these new territories are governed by corporate entities not nation-states, they are nevertheless protected by strong geopolitical forces (like the mega-polluter nation-states) who can coerce weak actors into accepting their terms and conditions—and by extension those of the corporations that support them. A vestigial nomos haunts these new territories as some form of unconscious jurisdiction, but one that is ungrounded. In legal terms, the commons are repeatedly represented as contested resources such as public land, water, and air, all of which are becoming increasingly privatized. As a result, they are understood almost exclusively in economic terms—designed to further promote the rights of private property at the expense of the commons.

10 The problem now is not that we cannot imagine what climate collapse might look like (we are already witnessing such changes), but how to wrest the discourse of the commons from that of private property to make collective decisions on a global scale.

Here I would like to distinguish the traditional model of the commons that, according to Garrett Hardin and Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom, can and should be enclosed to make them governable as a territory (by the state or private actors) to a concept of the digital commons as something that is beyond enclosure, governance, and any territorial ambitions. Given that information cannot be easily partitioned into privately held territories, we need to treat the commons as something other than property owned by large conglomerate entities, run on cloud servers and data centers, and we cannot do so if the only vision of the Earth is still deemed a plethora of resources to be exploited and divided up among nations and multinational corporations.

11 4. The Future Is a Memory

Pierre Nora refers to archives, museums, and monuments, as

lieu de mémoire: a site of memory, where the past is remembered, commemorated, or celebrated, but also where the act of remembering is rehearsed in an attempt to recover one’s relationship to the past. For Nora, such

lieux de mémoire are symptomatic of a society that is losing its memory or its capacity to experience the past as a lived part of the present. As Toby Lee writes (

Lee 2020), Nora’s ‘

lieux de mémoire’ are themselves the impoverished substitutes of the ‘

milieux de mémoire,’ (82). But the goal of the Future Now Project is not to re-create a static landscape somehow frozen in time: it is to foster dynamic interdependencies. By creating an archive for future Tuvaluans out of contemporary memories and artifacts (the items of the now) The Future Now Project only further illustrates what Jacques Derrida (

Derrida 1996) perceived as the fundamental aporia of what he called “archive fever”: the will to preserve the living memory of something unique and singular that is recorded as something passing out of existence. Building from Derrida’s argument, Dragan Kujundžić connects the impulse to archive to the Freudian death drive: an impulse that belongs to, on the one hand, “repression, a record of passing and death, the recording itself, and on the other hand, the opening that is to the future, and which, as a trace of its own demands or commands transmission and translation” (169). Kujundžić, like Derrida, associates the archive with the death drive (as so many acts of erasure) but also the Freudian unconscious, wherein the archive serves as a mechanism of repression and control at the same time, and it retains the vestiges of some traumatic past. Kujundžić (

Kujundžić 2003) even lauds electronic media for its ability to record, store and retrieve memories. He writes, “[e]very act of computerized archivization is also an ethical act, a racing against catastrophe” (187). Here there seems to be a conflation of the concept of return (to come or

a-venir) and computational retrieval. The notion of the future to come is spectral, ghostly, not operational as simple computer functions, to bury (erase from sight) and unbury (retrieve or make present again).

The problem with this faith in, and increasing dependance on, cloud computing, is twofold. First, as Cubitt notes, “optical and magnetic storage media are notoriously short lived: There will be no records other than those saved on paper. In the absence of power, the archeologist might be the first to actually read the manuals, knowing, however, that she has no machines on which to implement their instructions” (Cubitt, 15). Similar to the Earth’s resources, energy is finite. It can only be changed from one form to another, but in those changes, it enters into geopolitics and material conditions. That is, it is subject to degradation, erasure, catastrophic events, willful erasure, and a potential future lack of political or economic support to sustain mass data. Aside from the physical constraints of cloud computing, Tarek Elhaik and Pooja Rangan see a second (

Rangan 2017), deeper problem underscoring the discourse of salvaging, which is often linked to the ideology of curing (

Elhaik 2016). They ask, how can an archive, even if it is immersive and interactive allow for societies to continue to change? In other words, how can a structure be open to the future to come or living in a radically changing relation to Earth when algorithms both erase and fill in for what has been damaged or lost to time? Against the backdrop of this preservationist homage to the ideal of recording so as to salvage a nation or a people from climate catastrophe, from the point of view of the cloud-based archive itself, the 3D LiDAR scans pose a significant challenge to storage, organization and material entropy, but they also seem to have replaced symbolic forms of authority and sovereignty with automated ones.

5. The Vestigial Unconscious

Freud describes the unconscious as a repository (an archive) of feelings, memories, impulses, and experiences, but also one that functions as a control mechanism (a repressive system), a feedback loop, forming and informing the inner workings of each individual psyche. Unbeknownst to the individual, the unconscious sorts memories and assigns them a particular symbolic meaning within its own system of authorial codes. It is this system of mastery and control that produces individual subjects. But the question of who controls the feedback mechanism remains unclear.

Unlike his uncle, Edward Bernays postulated that modern societies “are governed—[meaning that] our minds are molded, our tastes formed, and our ideas suggested—largely by men we have never heard of … It is they who pull the wires that control the public mind” (37). He would later euphemistically rename propaganda, “public relations,” and describe it as “the engineering of consent.” Thus, for Bernays, humans are unconsciously controlled and exploited by other humans (

Bernays 1928). But consumer citizens seem to be generally aware that they are the target of various methods of persuasion—from political propaganda to advertisement and algorithmic procedures—and that their response to such indoctrination serves the interests of governments, political parties, or multi-national corporations. However, once memory is archived and sorted by computer programs, and control becomes automated, the work of men “who pull the wires” also becomes the work of machines and their algorithms, making far less clear whose interest(s) this system is actually serving. As Wendy Chun explains (

Chun 2011), “[b]y storing programs and becoming archives, computers make the future predictable,” but she also likens the hard drive “written by information security experts…to Freud’s description of the uncanny” (176, 134). What is deemed predictable is a world view of individual human subjects governed by rules, economic forces, and social mores. If the digital can be applied to the unconscious, then data analytics must assume the role of the analyst. But even so, it is not clear how something that is based on existing data and systems of value can predict the radically shifting reality of the Earthbound? For example, climate predictions have already vastly underestimated the accelerated pace of global warming.

By rendering the Earthbound readable as information or data, the digital unconscious continues to function as a vestige of an older understanding of the world—an understanding in which humans are controlled by language(s) they have created and to which they are subjected (whether it be linguistic or mathematical). But as David Marriott reminds us (

Marriott 2021), “the unconscious is not realizable as ontology;” there is no logic, mathematical or otherwise capable of rendering the unconscious as anything but an analogy (19), and analogies by definition are contingent on their historical context and the circumstances under which they are generated. According to Freud, the unconscious is both a process and a virtual space, much like cyber-space, where meanings collide and become indistinguishable. The truth of the unconscious is, thus, the vestige of such collisions, and any unconscious mastery of one group of men over another is not based on ontological truth but on analogically concealing unwanted truths. Simply put, the truth of mastery is nothing other than an illusion (a recursive slippage) based on analogy. Yet for Freud, the most concealed part of the unconscious harbors an inhuman force, the death drive, which he described as the vestige of a chaotic and even cruel past that seeks to undo any life force or sense of oneness. Algorithms also excel at creating correspondences (via analogies), and with them, new types of subjects—ones that are “matched” to products, images, or ideologies such as consumer citizens, avatars, online-personas, bots, cloud-based communities—but they also seem to perfect and promote this vestigial and automatic destructive force that is incommensurate with the Earthbound in all of their human and non-human forms. Freud rather disingenuously dismissed the “oceanic feeling” as religious and therefore non-scientific, stating that: “I cannot discover this ‘oceanic’ feeling in myself. It is not easy to deal scientifically with feelings” (

Civilization and Its Discontents, 252). But what is the death drive but another unscientific feeling, a negative one that Lacan associated with lack and called a defining negativity (

Lacan [1966] 1977). If we cling to a model or platform defined by incongruous forces—a lust for extraction, exploitation, endless profit and power over others on the one hand, and entropy, cruelty, and destruction on the other—then we cannot help but embrace Freud’s vision of inevitable extinction. But this is a decision made by the Global North and the corporate interests that drive them to sideline all oceanic feelings as well as indigenous knowledge in the name of such destruction.