1. Introduction

Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land is a transdisciplinary practice-based artistic research project around Sámi cosmology and indigenous reclamation of sacred spaces. The Sámi are the indigenous people of Sweden, Norway, Finland and northwest Russia, and I have my ancestral roots in areas situated on both sides of the Swedish and Norwegian borders. Eanadat/Spirit Land is a collaboration between me, a Swedish Sámi textile artist, archaeologist and researcher, and Frank Berger, a Finnish Swedish musician, composer and theologian. Berger has set music to my monumental wall hangings, representing three of the cosmological spheres in Sámi cosmology: Vuollemáilbmi/Underworld, Eana/Earth and Albmi/Heaven. The artwork fuses textile art, instrumental music, poetry, joik (a traditional form of vocal art) and song and is performed in churches in Scandinavia, linking to the reconciliation process between the Christian churches and the Sámi people without being an official part of this. Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land is independent from the official power institutions and operates as a free voice.

As a researcher, I work in the academic discipline of practice-based artistic research, which centers around the artwork, claiming that creative processes themselves lead forward to new knowledge. For this reason, the starting point for the article is the weaving act, and I use writing in order to reach the core of the artistic process. From this domain, I write and weave an alternative theology of the Feminine Divine based on traditional Sámi knowledge and personal experience. After that, I create a theoretical context for my work and place it in perspective of current indigenous feminism and spirituality. This alternative structure for the text deliberately puts theory last.

In the article, I develop my reflections upon the project and, simultaneously, on how it can be a seen as an act of reclaiming indigenous voices in sacred spaces, breaking free from the silence of the colonized past.

My research is both socially and politically engaged. It is not neutral in the traditional academic sense, and it involves both societal change and individual empowerment. This is an important stand in contemporary indigenous research (

Tuhiwai Smith 2012). It is, however, still unusual within the field of artistic research. Over the pages, I will chisel forward an outline for spiritual indigenous feminism, giving voice to my forerunners, fellow humans and myself. We were silenced due to colonization and inherited and personal trauma. My aim is to break this inherited silence.

By writing this text, I give voice to the silent and almost forgotten land and bodies that gave me this life: my forerunners, forewalkers and foresingers. I write this as a vindication of our right to speak up and be heard in the sacred spaces of our time and for our need to be embraced and confirmed for doing so.

2. Methods, Theories and Materials

I weave. This is the fundament and the core of the survey. Weaving is both method and material, and for me, it is the way I choose in order to connect to my ancestors’ wisdom and to the land they were deprived of by colonization. Weaving is my decolonizing practice.

Alongside weaving, I use the methodology of reflective writing in order to reach the depths of the artistic process. I write from the inside, reaching out to transpersonal ground in order to find my personal spiritual voice. I write in the form of poetry and free-flowing text.

Then, I create a methodological and theoretical context of indigenous feminism for my artistic research work, drawing upon current international scholars in the field, placing my own work in relation to theirs. I clarify how spirituality is considered a vital dimension of making in Sámi culture and traditions.

Further on, I outline a method for practice-based artistic research that rhymes well with indigenous making practices, where the creative process is the core knowledge of human existence. I then make a survey of accounts of traditional Sámi cosmology and spirituality by previous scholars; as well, I draw upon my own experiences from ancestral oral tradition in childhood and upbringing. Combining all this, I set out to decolonize Sámi spirituality.

The (pre-)historical point of departure for the survey is the weaving traditions from the Norwegian Sea Sámi areas and my own learning to weave in the old ways in order to reconnect to my ancestors. I investigate the prehistory and history of traditional Sámi weaving techniques, recreating a sense of bodily and spatial experience of weaving on a vertical loom.

Practice-Based Artistic Research and Reflective Writing

I have worked with practice-based artistic research for almost 20 years. This academic field is characterized by researching through the act of making, not by setting out to theorize creative processes. I was involved in the development of practice-based research at Konstfack University of Arts, Crafts and Design in Stockholm, where I was employed as an artistic researcher and project manager, teaching research-oriented courses to BA and MFA students and post-graduates for 12 years. I developed a method of writing that can be suitable for this particular form of research within Fine Art and Craft. I made use of it in several post-doctoral artistic research projects funded by the largest Swedish research funds such as Swedish Research Council, FORMAS and the KK-fund (

Göransson 2005,

2012,

2015,

2017;

Göransson and Ljungberg 2010) and in my teaching graduate and post-graduate art students.

The specific way of artistic research writing I developed during these years, I call reflective writing. The method is clearly described in the article

Writing from within the artistic process in the series Art Monitor, published by The Artistic Faculty at University of Gothenburg (

Göransson and Ljungberg 2010). In short, it is a matter of developing language, form and content that suits research in Fine Art and Crafts, drawing from Post-Modern critique of Western epistemology. It is an alternative kind of research writing that accompanies the rather uncontrollable creative process of art making. The method “writes away” from the analytical distance that otherwise characterizes many (critical) artist’s texts and that tends to render us critics of our own art. The reflective research text can, however, be and often is helped by other kinds of writing, such as critical writing. This is precisely what I do in the present article. Reflective writing is the artistic voice from within the body of one’s self and the artwork while critical writing constructs a contextual framework, accompanying and strengthening this voice.

I once wrote:

Is it possible to write the artistic process? I mean not on art, or about art, but from the inside of the very creative process, its phases and spaces in between, its ups and downs, and its sequences of flowing forwards and of blockage and loss… Process and change. Constant movement built by a series of standstills, tiny bubbles of “nows” together composing linear time. But isn’t that an illusion? What if the linear form of the process really is something else? A shape we yet cannot grasp. Just like writing. It seems linear on the page, but suddenly you become aware of that the end really is the beginning, and that he blockage you left behind now appears to be the only way to go on…

In my current research around Sámi weaving and feminist spirituality, I continue and develop my previous research methods even further from this standpoint. The main new thing that I bring in is the collective and politically empowering aspect of the artistic research work in an indigenous context. Making art/crafts is used as a way of connecting: to the indigenous past, my ancestors, my contemporary fellow others and, finally, to myself on a deeper level.

3. Decolonizing Sámi Spirituality Through Artistic Research: A Feminist Approach

I begin this section with deep diving into the artistic process. I invite you readers into this realm by means of reflective writing, a way of conducting artistic research, where writing is used as a means to reach the transpersonal depths of the creative process. I will write alongside the weaving process and thereby construct a woven theology for a reclaimed Sámi spirituality linked to the Feminine Divine. This is my woven theology, my practice-based study of Sámi religious faith, practice and experience. It is my statement, and it is not sanctioned by spiritual authorities such as an institution, a leader or a divine creature/god. It is based on oral indigenous tradition and personal experience, unlike the theology of the established world religions. Sámi spirituality was, and still is, decentralized, multifaceted and changeable. It is characterized by individual and collective differences according to, among other things, local traditions, geographical conditions and personal needs. This clashes head-on with the view of centralized religions, whose fundament is always hierarchical, static and formalized by an apparatus of power. Sámi spirituality is not uniform. It differs in time and space, and there are both feminine and masculine components to be found in different accounts of Sámi spirituality/cosmology in the past. Today, here and now in this text, I choose to focus on the Feminine.

After this, I create a methodological and theoretical context of indigenous feminism for my artistic research work, followed by an outline for artistic indigenous research and activism. Then, I investigate Sámi spirituality more closely and formulate a standpoint for my work in the present project. Further on, the concepts of decolonization and reconciliation are examined. Finally, I make a survey on previous research on the history and prehistory of Sámi weaving.

3.1. Weaving the Spirit

Everything is animated: Nature, flora and fauna, Cosmos, the transcendent peaks of existence as well as the little moments of everyday life. I see my artistic practice with this world view, with this sight. Every decision I make, every move with my hand, every touch, every glance and every bodily response to the material have spiritual dimensions. I can feel it; it is true. It is as real to me as the threads running across the growing work in my loom. It is not something I choose. It is a fact. It is just there, from the beginning.

I weave my cosmology out of the materials of the Earth; wool, second hand textiles, silk organza, pine roots, grass, moss… I weave layers of time, composing the Earth I walk upon, which embrace me and will welcome me when my spirit will leave this body one day.

I weave, and by that making, my voice becomes alive. My voice awakened rather unexpectedly. Sound and words came in the form of joik, the song of my people, and also in the form of poetry. Last, but not least, the words came to me in the form of this article. The researching voice in me that had been silenced for quite some time was also awakened and brought to life. In all these aspects, I reclaim the voices of indigenous land, bodies and spirit, for myself, my family and my ancestors, together. I reclaim it and I need you in order to be heard.

Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat /Spirit Land

Poems for the four weaves

Weave I: Vuolleáibmu/Underworld

- Vuolleáibmu

- Eatnama vuolde leat ádjagat, váriid ruohttasat,

- máttariid lavlut

- Silbaárppu cađa stirdon magma

- Psyke suoivan dat amas álgoálggus arena

- Jápmin ii jorggit eallimii

- Gulat go eatnama váibmu čoalkime

The Underworld

- Below the earth there are springs of water, the roots of the mountains

- The songs of the foremothers

- Silver threads running though petrified magma

- Shadows of the Psyche, the unconscious

- The primal scene

- Death transformed into life

- Can you hear the heart beat

- of the Earth?

Weave II: Eana/Earth

- Eana

- Ádjagat ja mearat,

- várit mat gusket albmái

- Ilbmi man min vuoigŋat,

- buot šaddet

- Jápmin ii jorggit eallimii

- Skeaŋkat, ruoktut

- Máttaráhkut, / eatnamat

- Eadni ja mánát seamme ládje

Earth

- Fresh springs and oceans,

- mountains that meet the sky

- The air we breath

- Everything grows

- Gift

- Home

- Madderahkka, Mother Earth

- Mother and child at the same time

Weave III: Albmi/Heaven

- Albmi

- Máŋgalágan sfearat mat luitet čuovgga čada

- Ja čielgasit čuvget juohkehačča erenoamášvuođa

- Musihkka, čudjet eatnamii gomuvuođas

- hirbmát stuora ŋiskun ránu čada.

- Mas heŋgejit geađggit

- dego dološ sámi arbevierru

Heaven

- Spheres in layers transparent

- but clear in each and every one’s individuality

- Music that resonates through space

- and reaches Earth

- A giant weave, with weights

- the ancient Sámi way

Weave IV Dovdameahtun ođđasat/The New Unknown

- Dovdameahtun ođđasat

- Harmoniere dološ áiggiid ja boahttevaš áiggid gaskkas

- Dissonánssat

- Gahččan ja máhccan

- Mii rahpasit vai sáhttit váldit vuostte

- Daid maid mii eat dieđe.

The New Unknown

- Consonance between the past and the present

- Dissonances

- Break through and return in order to meet

- We open up inwards in order to meet

- what is yet unknown

- The fourth weave

- is us

3.2. Reflective Writing from Within the Artistic Process

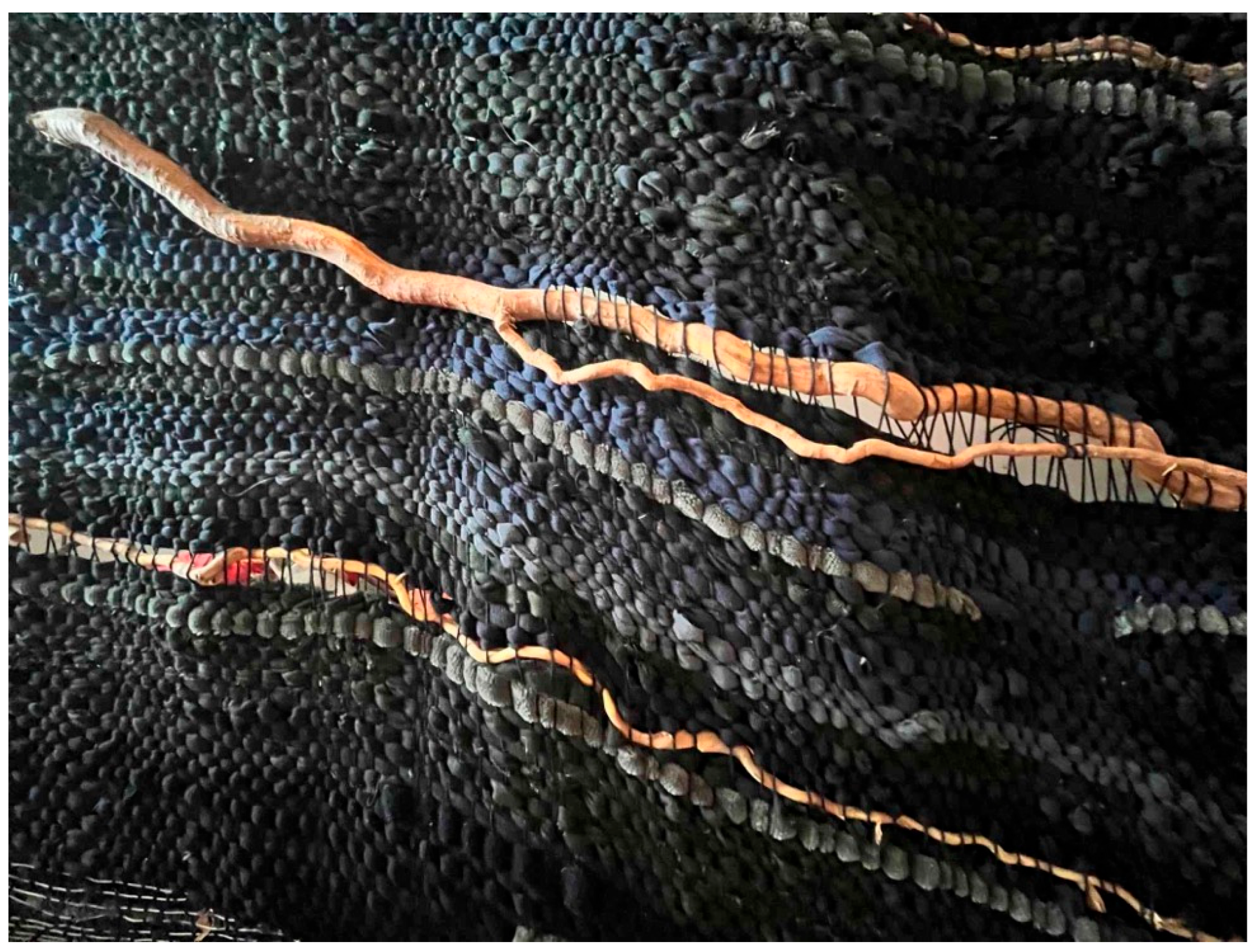

- Vuolleáibmu/Underworld

- Dark, deep and ancient. I weave the layers of the Earth, time constructed upwards, layers packed on top of each other, attaching, permeating water to seep down through the soil. The darkness gradually appears in subtle nuances of black. Everything started here, in the dark, in the void that is the condition for transformation. Everything will end here, in darkness, in the specific space that is filled in with time.

- Here, the foremother’s dwell. I walk in their footsteps, trying to listen and learn. Take this woolen thread, they say, take it and put it on top of the other, gently push them together so they attach. Not too tight, so the fabric becomes stiff. Just as much as needed, so they hold together and can adjust according to the strains of life. My dear child, they continue, Madderahkka herself is a weaver. She weaves our lives together from dark matter. She just grabs a handful of good soil, attaches it to the distaff, sets the spindle whirl in motion and begins to spin. Then, she decides what is meant to be, if the child should become a girl, a boy or something in between or other. She weaves in the dark, just like a baby dwells in its mother’s womb and grows there, in darkness, in order to be born and live in the light later. I can tell you that this darkness is not compact and solid. It is embedded. It is the foundation of it all, the ground on which we depend to grow and the condition we need in order to flourish.

- Vuollemáilbmi. This part of the World was excommunicated and forbidden. The ancestral mothers down here were considered a threat to God the Father up there, a threat to his power over the Earth. They did not understand that all the cosmological spheres are needed and complement each other.

- Threads. I use wool, both spun and unspun, dark fabric, pine roots I dig out from the ground in the North and silver threads. Then, I add the bones, hanging from hemp strings like amulets from a drum. The drum that is your sacred body.

- Of this I am now certain: God the Mother, Earth, Madderahkka, is indeed a weaver. She weaves our lives just like I weave this cosmological world right now for my project, with an open heart. She gives birth to the Spirit, gives it body and gives it life. The act of embodiment of the Spirit takes on the form of weaving. Threads flowing forwards and backwards, forwards and backwards. I spare out a section where light can come through, a space that opens in the bedrock. Thee warp threads now lie bare to the eye. The void suddenly transforms into a cave, a place for shelter in the middle of the dark I first perceived as an abyss. I can rest here now and recover, waiting for the right moment to be born.

- Adding the threads one on top of the other, I say a prayer. God, Earthmother, Midwife, Mother Earth, you are the sacred weaver, and I say this prayer for you:

- Mother, let me listen to your wisdom, teach me to sing in a gentle voice when my pain threatens to silence me altogether. Open my voice Mother, open my ears to the beat of your heart, so it can guide me and give me strength enough to walk steadfast for those little ones who depend on me. I sacrifice my time walking along the thread of this life to the task I was given before I was born. Make me accept the challenge willingly, so that my descendants may learn from my mistakes and benefit from my achievements.

- Eana/Earth

- Early morning, and Beaivi, the Sun, awakens the upper world, the rooftop that covers the dark. The colors are fresh blue-green and crispy, like grass covered by a thin surface of frost. When I take a deep breath and the air swirls around in my lungs, it almost stings and gives me a tingling sensation of awakening. Does this do me good or does it hurt? I alternate between these two outposts, playing with the difference they make to my life.

- I walk up to the mountain tops, like sages have done before me for thousands of years. I withdraw in solitude in order for seekers to search for me and find me, so I can guide them with my knowledge from the travels down under. I withdraw, so they can come forward.

- This path is sacred. It meanders through the landscapes of the Earth, leading upwards, then down, then upwards again, so they think they have lost the direction they aimed for and that they thought was clear. Just go on walking, I say to them from my distance up there, just go on when the mist covers the footsteps of those who walked here before you. You need the mist; it helps you, even though you are unable to see it right now. That which covers your clairvoyance will refine you and make you strong. Trust me, I walked here before you, and I know.

- Listen to the waterfalls. Near them, you can hear the voice of the Sacred Mother. She sings in running water. Oceans transmit their immense masses of life, where the whales sing with her in choirs. They sing because they are alive; that is the only reason. They sing, just like I do, when I now am awakened from my ancient sleep. My voice is strong and soft at the same time. I sing the land. I sing the grass, the trees, the birds, the reindeer, the wolfs, the ravens and the bear. I sing the springs and the waterfalls, I sing people, food and dwellings, and I sing births and deaths. I sing the Earth that we were given the moment we were born. I sing her. She is mother and child at the same time. She is the shelter. She is the Gift. My voice reaches out to everything alive in a joik composed in running wate

- Albmi/Heaven

- Chords that reach the Earth and embody space. Northern light appears against a clear, yet dark, sky. It is all a giant weave, with warp weights the ancient Sámi way.

- Think about the fact that the darkness out there resembles the conditions in the world under us.

- What if Vuolleáibmu and Albmi is one and the same, if light and shadow, day and night, actually are two sides of the same thing?

- What if God the Father and Earth the Mother may be interdependent and the fusion between them are the prerequisite for life to arise?

- Heaven is the giant weave that Madderahkka composes out of darkness. She takes the stagnation of pain, which is the root of all evil, and transforms it into transparency and wisdom.

- Fabric, interwoven threads, always have spaces in between. That is its very nature. Depending on the distance when you look at it, you can see through it, or not. If you are close, you see through it, but if you are far away from it, you only see a compact surface. That is why you need to go deep inside of everything, yourself included, in order to reach enlightenment. You can then see through what you at first perceived as hidden.

Dat dovddus ođđa/The New Unknown

- Spirit of the Land

- Spirit made visible, audible, restored by this act

- Spirit of the Land

- now restored and allowed to sing, so You can give me my voice back, reconnecting me to árbediehtu, the inherited knowledge of my ancestors

- Spirit of the Land

- once silenced and almost killed, now I can see You shimmering in everything, in all that grows: in animals, plants, the Sun, the rain, in stones and stars and the Moon

- Spirit of the Land

- Animated landscapes of the future

- This fourth weave is what we create together today

- The threads are now our voices and instruments, our bodies breathing together in this sacred space

- The fourth rátnu/weave is what we create together when the artwork is performed

- and what we go out to when we leave this room

- We bring the threads with us

- weave them together with others we meet

- The fourth weave is us

- Consonance between the past and the present

- Dissonances

- Break through and return in perpetual cycles composing time

- We open up inwards in order to meet

- what is yet unknown.

4. Context

4.1. Indigenous Research, Duodji, Dáidda and Spirituality

I draw upon the work of indigenous scholars Linda

Tuhiwai Smith (

2012),

Rauna Kuokkanen (

2019),

Tore Johnsen (

2022) and

Liisa-Rávná Finbog (

2019,

2023). Tuhiwai Smith is a Māori scholar from New Zealand. Her groundbreaking work goes far beyond decolonizing research methodology, in that she states that developing indigenous research from within will help us reclaim control over not just knowledge but also of our ways of being, of our lives. Sámi scholar Rauna Kokkanen, in her turn, outlines a new theory of indigenous self-determination, bringing in a feminist analysis of indigenous political institutions, and critically examines normative conceptions of indigenous self-government. Liisa-Rávná Finbog, finally, outlines a way of making research, where she, by the act of making duodji/Sámi crafts, enacts reconnection with her Sámi roots, reclaiming cultural heritage and the human voice that was silenced and almost lost in the colonization of the Scandinavian countries. Finbog has a PhD in Museology and is a duojár (Sámi crafts woman) with skills in aesthetics and storytelling. She looks upon duodji as a Sámi system of knowledge, which I find intriguing, and I consider it an act of decolonization in itself. Finbog makes use of the metaphor of ruvdet, braiding, for instance, as a way of structuring research (

Finbog 2023, 78p). She visualizes her research methodology in lines of thought, just as the traditional Sámi ruvdu/braid was composed out of four or more strings of yarn. She draws upon previous scholars and activists, but in my opinion, her approach is unique, in that she combines the utterly practical act of learning the skills of traditional duodji with the outline of groundbreaking contemporary indigenous research methodology. She also brings in the spiritual dimension of indigenous research in seeing duodji as the spirit of everything (

Finbog 2022,

2023, 134p). Practice-based spiritual activism by means of making is something that I adopt in the Spirit Land project, even though I do not claim to be a duojár. I see myself as a dáiddar, a contemporary artist, drawing upon duodji as a tradition, but interpreting tradition in my own way today (see further discussion in

Section 4.7. Sámi Weaving, Duodji and Dáidda).

4.2. Symbolic Rematriation

In the article, I develop my reflections on the political aspects of the work and, simultaneously, on how it can be a seen as a vehicle for artistic freedom of expression of indigenous voices in sacred spaces of our time. Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land is an artistic performance that may function as a ceremonial act of liberation from the silence of the colonized past. As such it may be a tool for awareness, which, in its turn, may inspire societal change.

In the

Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land project, I work with an alternative form of repatriation. It is not the question of taking objects out of museums but of reconnecting to the indigenous cultural heritage by reconnecting to bodily experiences of making. I call this

rematriation. The concept is a reformulation of

repatriation and was initiated by indigenous activist and author Lee Maracle in 1988 in her book

I am a Woman, where she decolonizes the very concept of repatriation (

Maracle 1988). This means that in addition to returning cultural/sacred objects or lands, it also opposes colonial and patriarchal social structures that often are embedded in repatriation processes. Led by indigenous women, the reunification of individual objects developed into a broader social movement aiming at restoring relationships between living indigenous peoples and their ancestral lands.

Sámi scholar Eeva-Kristiina Nylander’s Ph D thesis, From repatriation to rematriation: dismantling the attitudes and potentials behind the repatriation of Sámi heritage, from 2023, is an important example of fusing research and activism that places art in the core of societal change and decolonization.

Nylander has collaborated with Finnish/Sámi artist Outi Pieski in several projects combining art,

duodji and indigenous activism. Their collaborative project

Mátteráhkku ládjogahir, Foremother’s Hat of Pride during 2017–2020, investigates Sámi women’s hat

ládjogahpir, a traditional garment that was abandoned around 1900. They studied how the colonization affected women and how the hat the hat now has been rematriated into Sámi society (

Modig 2024, p. 4). To Pieski, repatriation and rematriation of Sámi artifacts to Sápmi is part of a larger artistic decolonization process. She writes about this in the anthology

Offentligt minne,

offentlig konst (

Public memory, public art: my translation from Swedish) (

Pieski 2022,

Enqvist et al. 2022).

Pieski was given the commission of producing artistic artwork for the new entrances for the Nordic Museum in Stockholm. This museum has a dark history of appropriating/collecting Sámi cultural artifacts in Sweden during the past centuries. This example of artwork produced by a Sàmi artist for a colonialist institution can be seen as a form of museological decolonization/reconciliation. It is, however, of utmost importance to keep on remembering past abuses. We must never, ever, let art be used to mask history, a fact that also applies to spiritual decolonization (see further discussion in

Section 4.5. To Decolonize the Sámi Spirituality.

Another artist who works with art as a way to reclaim the Sámi cultural heritage is Hilde Skancke Pedersen from the Norwegian side of Sápmi/Sámi land. She combines fine art with writing and scenography and is the artist behind the public artwork Spår/Tracks from 2000 at the Sámi parliament in Karasjok, Norway. In this intriguing artwork, focusing on symbolic representations of circles and labyrinths in the archaeological record in the local area, Skancke Pedersen draws upon (pre-)Sámi archaeological finds in a sensitive way that reconnects to the ancient indigenous knowledge and spirituality, giving voice to the silenced past of the Sámi people.

Máret Ánne Sara, finally, is a Norwegian Sámi multidisciplinary artist and author who investigates environmental issues and the consequences of colonialism affecting the Sámi people. She highlights ancestral knowledge and its importance for future generations. Sara was represented at the 2022 Venice Biennal. She often uses experiences from reindeer herding in her art, combined with deep traditional knowledge of the landscape in its different aspects. Sara is currently showing at Tate Modern in London, 14 October 2025–6 April 2026. In her work, she symbolically rematriates traditional Sámi knowledge regarding ways to relate to the land and its inhabitants on a deep level.

4.3. Sámi Theology and the Spirituality of the Everyday

In this section of the article, I draw upon the results of renowned Sámi scholars Louise Bäckman, Hans Mebius, Tore Johnsen, Åsa Virdi Kroik and Liv Helene Willumsen (

Bäckman 1975,

2005,

2013;

Mebius 2007;

Jernsletten 2022;

Johnsen 2007,

2020,

2022;

Virdi Kroik 2022;

Willumsen 2022). I also want to mention my own thesis at Sámi Allaskuvla in Kautokeino, in which I investigate the Sámi drum in the eyes of four different scholars, putting both the drum and the researchers in question in a critical societal context (

Göransson Almroth 2023).

Tore Johnsen, Sámi theologian, has outlined guidelines for a Sámi ecotheology, inspired by indigenous knowledge and liberation theology, among other things. Johnsen’s doctoral thesis

The Contribution of North Sámi Everyday Christianity to a Cosmologically-Oriented Christian Theology (

Johnsen 2020 is a major step in the process of decolonizing Sámi Christianity.

Johnsen’s theology is based on the fundament that nature is animated and that the divine is to be found everywhere in the form of spiritual beings, the underworld and also in the form of God’s presence in a direct way in all that is alive (

Johnsen 2007). Spirituality is seen as central to the organization of nature itself. He believes that today’s people must once again learn to communicate—to listen to and speak—with nature,

luonddujiena guldalit, (

Johnsen 2020, p. 96).

According to Johnsen, Sámi spirituality should always be understood as a part of the landscape where it functions. Interesting to me is the fact that Johnsen brings in joik, the traditional Sámi vocal art, in the discussion. Joik is, to him, a natural way of relating to the surrounding world, that is, a way of expressing spirituality. This corresponds to my own view upon composing and singing the joik Albmi in the Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land performance.

I do not consider Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit to be a Christian work of art. If I have to classify it, I would say it is transtheological. However, it is of great value to study Christian Sámi theology in order be able to place the work in the spiritual decolonization process. Thereby, we can restore what was taken from us by the Christian churches.

Sámi theologian Åsa Virdi Kroik’s doctoral thesis centers around the Sámi ceremonial drum (

Virdi Kroik 2022). She investigates the circumstances around a particular recent find of an old

gievrie, a South Sámi drum, that was found on the Norwegian side of the border between Sweden and Norway. The find is interesting in itself, but I choose to make a reference to Virdi Krok’s discussion around silence. She stresses the widespread occurrence of silence among Sámi people. Her informants were hesitant to discuss issues surrounding the find, but she raises the topic to a more general level and connects it to past and present experiences of marginalization, oppression and subordination. Besides this, Virdi Kroik means that silence also can be seen as a kind of resistance, using non-verbal communication instead of spoken language. It is a fascinating thought that oppression also may give rise to unique strategies of non-violent activism that need to be uplifted and noticed.

Helga West, also known as Biennaš-Jon Jovnna Piera Helga, is a theologian and poet from Deatnu river valley in the Finnish side of Sápmi. She is a doctoral candidate at the University of Helsinki. In her ongoing doctoral studies, West examines the reconciliation between the Sámi people and the Scandinavian churches in critical perspectives (

West 2020). She argues that the Church of Sweden sees the reconciliation process as a secular endeavor, while the Church of Norway instead uses Christian resources as a way to understand the complexity of the situation. West is of great interest to the

Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land project, since she brings in the role of art into her research work. West is also a writer and stresses the need of breaking silence and giving words to experiences of suffering due to colonialism (

West 2020).

Liv Helene Willumsen is not a theologian but a professor Emerita of History at the department of archeology, history, religious studies and theology at the University of Tromsø, Norway. However, she is of utmost importance to

Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land, as she investigates Sami spirituality from written sources. I want to highlight her studies of the witchcraft trials in Finnmark, North Norway, in the 1600s, where 91 people were executed. I would especially like to bring attention to her review of the trial against Anders Poulsen. Most specifically, I want to point out her survey of the trial against Anders Poulsen, where a thorough documentation of the Sámi ceremonial drum and its iconography is present. Poulsen was brought before the court because he was caught playing the drum, at that time considered an act of witchcraft and reason enough for being executed (

Willumsen 2017,

2022). In her dissertation, the Sami theologian Mienna Sjöberg examines sivdnidit, a specific everyday religious practice of the everyday among the Sami (

Mienna Sjöberg 2018), which is mainly found in Northern Sami areas (my note).

Sivnidit is a verb that has two meanings: to create and to bless (

Mienna Sjöberg 2018, p. 7).

It is linked to Christian traditions but practiced outside of church contexts, and it is not practiced by priests or other theologians but by ordinary people of different ages and genders in everyday life. This is consistent with my view of Sámi weaving, a daily practice with a deep spiritual dimension, something that will be developed further later in this text.

4.4. Sámi Cosmology and Weaving

In

Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land, I choose to work with a cosmology divided in three realms:

Vuollemáilbmi/Underworld,

Eana/Earth and

Albmi/Heaven. The accounts of traditional opinions of this differs in time and space according both to written sources and to the scholars/accountants that transmitted the information. Mebius speaks of both five and three cosmological layers in his survey of previous accounts (

Mebius 2007, p. 63).

In Sámi spirituality, reality has several layers or cosmological spheres. The topmost layer is heaven, with parallels to the Christian worldview, with a supreme divine power and associated protective being. Below this layer is the earth as people experience it with their senses. This too has its specific essence, strongly linked to natural landscapes, flora and fauna. Nature is seen as animated. The lowest layer is the underworld, where the foremothers, forefathers and ancestors live. Here are the roots, the origin, and under these, the dark forces also can be found: a historical counterpart to the unconscious in the human psyche, as we see it today. The lower layer of the Sámi worldview—the underworld—has been excommunicated and silenced by the Christian churches (for discussion see

Mebius 2007, 63p;

Göransson Almroth 2023;

Prost 2022. People who had access to these parts of the Cosmos have not been allowed to speak about them during the last three centuries. Knowledge and wisdom have partly been lost, although some aspects have been preserved deep within the Sámi lineages in secret.

I chose the number of three for several reasons. Practically, it made my weaving work manageable considering the production time that I had available. Further on, I am also fond of the number of three of mythological reasons: the three daughters of

Madderahkka/Mother Earth (

Mulk and Bayliss-Smith 2008;

Mebius 2007) is represented in Sámi culture in many ways. In some Sámi drums, there is also a three-part division of cosmos. This is common, but not altogether representative, in drums from the Umesámi area, where my close family originates from.

The world view that Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land is based on is the animated landscape. This notion and world view was something I grew up with, foremost by means of my ahkka, my paternal grandmother, who was my first and most important spiritual teacher. She taught me about the spiritual beings in Nature and how I should act in order to respect them. She transmitted messages from the past as well as from the future, from the underworld as well as the heavens, holding my hand in our common journey during my first decades walking on this earth.

Scholars agree that within Sami spirituality, everything is considered to be animated; landscapes, animals, natural forces and the Earth itself (

Mebius 2007;

Bäckman 1975). Sámi spirituality is usually searched for in ancient sacred spaces in the landscape, in the Sámi drums and in the clashes between Christian and Sámi world views present in missionary written sources from the colonization (

Mebius 2007, p. 44). Nowadays, indigenous scholars begin to incorporate the spiritual dimension in both academic research as such (

Tuhiwai Smith 2012) and in

duodji/Sámi craft (

Finbog 2023). I want to bring it into the field of artistic research.

I look upon Sámi weaving as a material-based spirituality in the core of everyday life, regarding both the actual and practical act of weaving threads together and the spiritual reconnective making process. The act of weaving woolen textiles on warp looms, as people have done for thousands of years, has a deeply rooted spiritual dimension that connects today’s weavers and their physical bodies with the Sami foremothers, the landscape and the divine.

4.5. To Decolonize Sámi Spirituality

My absolute conviction is that religion as such, just as ethnicity, always is a conglomerate of different cultural ideas and is shaped and developed in contact, not isolation, drawing upon the studies of Frederic Barth on the development of identity and boundaries among ethnic groups (

Barth 1969). There is no purely Sámi religion to excavate neither metaphorically nor literally. Before the Christian mission/colonization of the spirituality of the Northern countries, there were other religious systems that affected Sámi peoples’ lives and which permeated and merged into Sámi systems of beliefs and world views. Those belief systems then became Sámi. Further on, many Sámi today are today devoted Christians, which applies especially to the Northern parts of Sápmi. Here, the controversial Lars Levi Laestadius, himself of Sámi origin, initiated a revival movement among Sámi people during the 1800s that both controlled spiritual beliefs and behavior even more but also improved social conditions for people (

Østtveit Elgvin 2010).

Again, there is/was no clear-cut border between Sámi, Norse and Christian religions. However, that is not to say that Sámi spirituality does not exist. For instance, what we today consider to be the Sámi symbol of Beavi, the Sun, can be found in Bronze Age imagery all over Scandinavia (and globally). This does not make the symbol less Sámi. Further on, the Sámi god Dierpmis/Thunder man resembles the Norse god of thunder, Thor, the goddess Sárahkka resembles the Norse Freyja and the Christian mother Mary and so on. Worship and sacrifice in Norse religious practice have strong resemblances to Sámi pre-Christian practice. All this and more shows that Sámi spirituality did not exist in a vacuum neither before, during or after the official Christianization of the Scandinavian countries from the early Middle Ages and forwards.

What is clear, however, is that the Christian power institutions disciplined, punished and banned Sámi spirituality. Some scholars claim that this mainly started in the late 1600s, linked to the witchcraft processes in Scandinavia (

Willumsen 2022), and continued with the Lutheran reformation and the Pietist movement in the North during the 17th century (

Göransson Almroth 2023). My opinion on this matter is that the disciplining of Sámi spirituality started much earlier, that is, from the very moment the Christian mission was established in a more systematic way in Finnmark, Norway, that is, during the early medieval period. In the 1600s, the colonization of Sámi spirituality increased beyond sense and reason and was characterized by abuse, executions and discrimination. At this point, I find it crucial not to romanticize or idealize Sámi history. I do not believe that past Sámi societies and religious beliefs were altogether good, egalitarian or even feminist/matriarchal, just as Sámi society today can be criticized for patriarchal values and behavior (see

Kuokkanen 2007).

My standpoint is that Christianism represented by the Church, also the Catholic Church, was and still is a patriarchal power institution.

In order to decolonize Sàmi spirituality, we need to look outside the Western epistemologies and, in my opinion, also outside academic theology and history. An interesting example of this is Robin Wall Kimmerer’s work on indigenous knowledge and natural science, where she explores traditional and current relationships between the land and human beings. Being a botanist, a professor in Environmental and Forest Biology and a member of Citizen Potawatomi Nation, she combines Western and indigenous knowledge in a fruitful way. In her groundbreaking book

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (

Wall Kimmerer 2013), Wall Kimmerer leads us in her footsteps when she listens to the earth and other living beings. Plants are our teachers, she argues, but we have forgotten how to listen to their voices. Even though the book is not considered to be a theology of plants, neither by the author nor by readers, I truly perceive it as such. It is also a piece of art in itself. Since indigenous spiritual knowledge often is not intended to be shared with others, Wall Kimmerer asked her tribe for permission to write and publish the book. A Potawatomi spiritual leader agreed, however.

An example of the opposite is Sámi

duojar (craftsman)

, daiddar (contemporary artist) and spiritual practitioner Fredrik Prost’s book

Leŋges hearggi, sáhčal fatnasa (

Prost 2022) on traditional Sámi spiritual knowledge, focusing on the Sámi ceremonial drum. The book was a subject of debate, since it was nominated for the Nordic Council Literature Prize in 2024 but was published in the Sámi language only. Prost refused, and still refuses, to translate it to Swedish or some other majority language. Prost is utterly critical towards the Christian churches and towards Christianity as such. In an interview with the Sámi Information Center, he stresses that Christianism came from the Roman empire (

Marakatt 2025,

www.samer.se/3875, accessed on 13 October 2025). The Romans used the former religion of slaves and outcasts as a tool in their colonization of the world. The fact that people that were forced to convert to Christianism turned away from their traditional faith and spirituality is a worldwide phenomenon, not just something that characterizes the Sámi people, according to Prost. He compares this to the

Stockholm syndrome. (The so-called

Stockholm syndrome is a is a psychological phenomenon where

victims/hostages develop sympathy towards their perpetrators. It is a concept that arose during a world-famous bank robbery in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1973; my clarification).

I was happy to be part of a Sámi study group, working with the teachings in Prost’s book during 2025. Out of respect for the author, I will not share any of this in the present article, but I can say that it rhymed well with what I was taught by my paternal grandmother as a child and young woman and also with personal spiritual experiences later on in life (

Figure 4).

The question of sharing Sámi spiritual knowledge with non-Sámi is difficult. In the artwork and performance Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land and in the present article, I have chosen to share some of the personal spiritual experiences I have had during the years. It is a glimpse of communication with other realms, with what I here and now choose to call the Feminine Divine; you may also say God in her feminine aspect. This was not easy, since the performance was presented to an audience of several hundred people in three sacred spaces of the majority religion in Scandinavia. Writing this article is not easy either, since it opens the doors to a personal and hitherto hidden spiritual realm. Breaking the silence creates a feeling of vulnerability at the same time as it is an act of justified empowerment.

In traditional Christian theology and cosmology, feminine aspects are rather difficult to find. God is usually conceived as the Father, Christ is his son, and the Holy Spirit is not feminine. To bring in the Feminine Divine into spirituality is, according, to me an act of decolonization. Traditional Sámi spirituality consists of both feminine and masculine components as well as beings and forces of other genders and beyond. In Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land, I choose to focus on the Feminine as a statement of spiritual decolonization feminism.

4.6. Decolonization, Reconciliation and Grief

Decolonization is not an individual choice, as Dakota professor Kim Tallbear states (

Tallbear 2018, p. 152). It must be collective in order to function. We cannot reclaim our land, voices, cultural heritage and spirituality being isolated and hidden. Today, we live in an extremely complicated world, and we need to take an active part in it in order for decolonization to be accomplished.

The core of the Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land project is to give voice to indigenous spirituality in public sacred spaces of today in an artistic form. The decolonization aspect of the project is no more and no less than that. The artwork is performed and experienced by us artists and musicians as well as by our audiences in the different spaces in which we perform. The Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land performance cannot change history in itself or lead to forgiveness or something else that could be wished for. It may, however, function as a reminder and as a starting point for change to happen.

When we give voice to a silenced past, to silenced indigenous people’s experiences and spirituality, this inevitably brings forward grief. When our voices now are heard and when we remember, we also come in contact with immense pain and loss that has been carried silently over the generations. We cry the tears of our ancestors as well as our own, out of the longing for our roots and out of the joy of reconnecting to them.

Reconciliation, however, is something different, even though it can be part of a decolonizing process. It is of great importance to me to clarify this matter and to formulate a standpoint in the current discussion that is ongoing in the Scandinavian countries.

Decolonization is basically the process of liberation from a colonized past, so former colonies become independent from the colonizing countries. It also involves the undoing of colonial systems of politics, economics and culture, often reclaiming indigenous knowledge and psychological independence. Reconciliation, on the other hand, is a process of restoring relationships after conflicts. This can involve relations between nations, groups or just two sides in a political conflict or in war. Reconciliation aims at an agreement or some other kind of solution, and it has no connection to religion or spirituality as such.

In Scandinavia, we tend to equate the term reconciliation with the religious reconciliation that the evangelical Lutheran churches have initiated versus the Sámi peoples. However, it is important to examine this situation more closely.

Is reconciliation between the Sámi people and the Scandinavian authorities—churches and other—even possible? I am not sure of this. What I am sure of, in contrast, is that the decolonizing process of reclaiming indigenous land, language, music, dance, art, spirituality and freedom of expression, giving and taking back our sacred spaces that were deprived from us must continue. The abuses are so severe that I doubt that forgiveness is possible.

Reconciliation also takes two parts. How can we forgive that our ancestors were executed for using the drum, for healing the sick and for praying to the Feminine Divine? How can I personally forgive that my forefather was forcedly converted into Christianism and trained as a priest in order to be used as a tool in the excommunication of unaccepted spirituality among his own people?

There is a process of reconciliation going on between the Christian churches and the Sámi people right now. A documentation of the initial phase of this is presented in the so-called

White Book, published by the Church of Sweden (

Lindmark and Sundström 2016), and the current situation is shown in

Gustafsson Lundberg and Oscarsson (

2025). A major step in this process was when the former Swedish arch bishop Antje Jackelén asked the Sámi people for forgiveness for historical abuse and discrimination in Uppsala Cathedral in 2021 and a second time in Luleå Cathedral in 2023. During the latter, she stated that these both ceremonial acts were part of an ongoing process of reconciliation. Finland has also initiated a similar process called the Sámi Truth Reconciliation Commission (

www.reconciliation.fi, accessed on 12 October 2025). In early 2025, there was a ceremony held in Turku cathedral, where the Sámi people were asked for forgiveness, a counterpart to the Swedish ceremonies mentioned above. Turku cathedral is the center of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland. The fact that the final performance of

Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land was held here can be seen as a decolonizing act of spiritual reclamation that links the artwork to the reconciliation process of the Scandinavian churches, without being an official part of it (see further discussion below).

To decolonize the voice of indigenous spiritual expression is to get access to sacred spaces and to be able to speak, sing, move and weave in what way we choose and to be embraced in that act. If those spaces are in churches and/or in Nature is to me of equal importance regarding significance. The official sacred spaces of the Scandinavian countries today are, however, churches, mosques and temples, among whom the Christian churches still are in the majority. That is why we choose them as suitable spaces for our performances.

The collaboration between Frank Berger (who defines himself as non-Sámi) and me (who defines myself as Sámi) was, for me, also an opportunity to get access to the spiritual spaces I otherwise never would have been able to enter. Regarding Berger’s view of his role in the project, I would like to refer to his article in the present publication (

Berger 2025). My view upon the collaboration is that we met in a creative ambition of breaking the silence of the colonized past. Berger’s experience of living as a minority person in a majority society made me willing to trust his intentions in the collaboration. This was something I sensed intuitively from the moment we met, and it was reinforced during the years of collaborative production that followed.

The project has been a process of voice giving in several ways. Frank Berger is a professionally trained singing coach, besides his profession as a composer, musician and opera singer. When he invited and welcomed my joik Albmi/Heaven into the musical part of the performance, something deeply restorative happened to me personally but also to my lineage. Our joik had been muted and excommunicated from our lives and bodies, from sacred spaces as well as from the profane, past and present. My family and people were given a voice. It was an immensely restorative and healing process.

I do not consider Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land to be a part of the official reconciliation movement, as I already mentioned above. The artwork is independent, and it acts as an individual and free voice in contemporary society. It is of utmost importance that this is considered. It has, however, now been performed in several established majority church spaces, so there is, of course, an impact on these environments. I was told that it was the first time ever that Sámi drums and jojks were heard in Turku cathedral when Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land was performed 11 September 2025. Indigenous voices were heard there at that time and in that place. This is groundbreaking. Even though Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land is not a part of the reconciliation process of the churches, it is, however, an example of a decolonizing spiritual act, performed in one of the largest Christian churches in Scandinavia.

Reconciliation may be possible, but this involves political and social change. This is beyond what our artwork can do. The fourth weave, Dat dovddus ođđa/The New Unknown, is symbolically and literally composed out of what happened during the performance, the fusion between the artwork, us artists and musicians and the audience. This weave is what we bring forward from the performance and what we act out in the world afterwards. It can be a starting point for reconciliation, but that cannot be guaranteed. The results are yet unknown.

4.7. Sámi Weaving, Duodji and Dáidda

I have been an artist for more than 40 years, starting with weaving and painting, followed by sculptural work in concrete and stone. In the middle of that long period, I studied archaeology and finished a PhD in a feminist perspective studying gender and body languages in textile imagery from the Viking Age and Early Middle Ages in Scandinavia (

Göransson 1999).

I then returned to weaving. My artwork has, for the past three years, been focused on investigating of Sámi weaving traditions and spirituality in practice-based and innovative ways. The point of departure is the rana (Umesámi and Swedish) and rátnu (North sàmi)/grenevev (Norwegian). The rana/rátnu is a traditional Norwegian Sea Sami hand woven fabric of sheep’s wool. The rana was formerly used as a utility textile, mainly in the form of cover for the lávvu/tent traded to mountain Sámi on both sides of the border between Norway and Sweden, but it also functioned as bedding indoors. The rana/rátnu is a striped, rather loosely woven two-shafted woolen fabric, produced on a vertical warp-weighted loom. This kind of loom that dates back to prehistoric times (see below). Today, the rana/rátnu mainly functions as a wall hanging, for decorative purposes, both among Sámi and other Nordic people in Norway, Sweden and Finland. It also functions as a cultural identity strengthening object in official spaces, like, for instance, on the walls of Sámi Allaskuvla/Sámi University in Kautokeino, Norway.

I look upon weaving as a feminist political practice, linking the past to the present. I consider the making of duodji (Sámi craft) and dáidda (contemporary Sámi art) to be forms of reclaiming my roots, of making kin. Duodji is often closer to tradition that daidda, but this is not always the case.

Duodji is the traditional Sámi craft, in which weaving is included. This branch of

duodji is called

dibmaduodji. In the present project, however, I chose to regard and practice weaving as a form of

daidda, contemporary art. This may seem somewhat controversial. I want to refer to the ongoing discussion on art and craft (

Hyltén-Cavallius et al. 2015) internationally. The need for strict borders between the two may no longer be of the same importance in the future. For us Sámi, we also have the special situation with plagiarism of Sámi

duodji for sale, when non-Sámi produce Sámi objects for sale, and the background of stolen cultural heritage by the authorities that complicates the question (see discussion in

Hyltén-Cavallius 2014), a fact that makes the discussion utterly complicated.

There was no word for contemporary/fine art in Sámi until the 1970s, when the Máze group was formed (1978–1983), consisting of seven Sámi artists that came together in the environmental protests against the exploitation of the Alta river in North Norway; Synnöve Persen, Britta Marakatt Labba, among others. They launched an organization for Sámi artists that supported and developed a new field of contemporary Sámi art considering the specific needs and conditions that characterized Sámi artists. There was a need for a term for fine/contemporary art in the Sámi languages: dáidda was born.

Gunvor Guttorm is a professor of

duodji/Sámi crafts at the Sámi University College in Kautokeino, Norway, and a practicing

duojar/Sámi craftswoman herself. Many years of experience in research, teaching and strongly rooted own duodji production shape her unique contribution to indigenous research. She discusses the two concepts

duodji (Sámi crafts) and

dáidda (Sámi contemporary art).

Duodji and

dáidda are two sides of the same coin, according to Guttorm, in a similar way that European art and crafts are connected (

Guttorm 2012, p. 183). However, in

dáidda, essential parts of the knowledge content and depth of duodji are omitted/lost, even though they share the same basis (my formulation). I partly agree with this, but I also think that

dáidda gives us more freedom and space that also Sámi people are entitled to. It is not a question of losing traditional knowledge but of developing making (Sámi art, craft, dance…), bringing it forward to new arenas and in new kinds of expression that can enrich tradition.

Dáidda can function in respect of tradition, even though I do not think this always is necessary. Art, also Sámi art, in my opinion, must be free and independent. Sámi communities and organizations benefit from development of tradition. This is not the same as abandoning it.

I look upon weaving as a feminist political practice, linking the past to the present. I consider the making of duodji and dáidda to be forms of reclaiming my roots, of making kin. Duodji is often closer to tradition that daidda, but this is not always the case.

4.8. (Pre-)Historic Background

The

rana/rátnu was produced on the warp-weighted type of loom, characterized by a vertical warp, stretched out by warp weights of stone (or clay). It was common all over the Scandinavian area in the Viking Age, and according to Marta Hoffmann it is likely to have existed since the Neolithic (

Hoffmann 1964, p. 19), even though finds of warp weights only begin to appear in the Bronze Age. Later historical accounts of

ranas/rátnus come from Northern Norway; records of levy from Västerbotten, Sweden, mention them in 1553 (

Hoffmann 1964, p. 111), from Oksfjord, Troms, Norway, in 1567, and from Kautokeino in 1583 and 1603. It is said that Sámi people paid levy in the form of old grener, among other goods (

Hoffmann 1964, p. 112).

Hoffmann states that the weaving of

grener (i.e.,

ranas/rátnus) was regarded as a Sámi specialty

for long; what she means with that is not precise. She claims that Sámi people likely wove

grener in the south areas of Norway as well (

Hoffmann 1964, p. 113) and that the Sámi adoption of the warp-weighted loom in

primitive (my italics). Norse time must have occurred in this area. In south Sàpmi on the Norwegian side of the border,

grener is mentioned in connection with trade in Bergen and Trondheim 18th (

Hoffmann 1964, p. 113). Nomadic Sámi used

grener before 1600. Swedes and Swedish Sámi bought

grener in Norway in the 17th century and Russians bought

grener in Northern Troms, Norway.

Grener seem to mainly to have been an article of trade.

We have several illustrations and written accounts of ranas and Sámi textile production from the priest and linguist Knud Leem, travelling among the Sámi in North Norway in the 18th century; his pictorial illustrations are of great interest, although probably not always totally accurate.

The nation states of today did not exist during the Viking Age. What we nowadays call Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Iceland, in those days, were a collection of small lands under the rule of chieftains. Over the whole area, the warp-weighted loom is a common find at archaeological excavations from the time. This links us together. Norse women brought the loom with them to Iceland on their ships from what we today call Eastern Norway, and in Iceland, it remained in use until early in the 19th century. Sweden replaced the warp-weighted loom for the horizontal loom earlier, probably sometime in the Early Middle Ages. In Norway, however, the warp-weighted loom stayed in use until the 1950s among rural people in Eastern Norway and among the Sea Sámi in the Troms area in the North. Among the Skolt Sàmi of northern Finland, the warp-weight stones could be heard singing until approximately the same time. I am of Norwegian Sea Sámi descent myself, so this project connects my contemporary artistic practice to my foremother’s life and work up North.

The warp-weighted loom was not unique for the Sámi. On the contrary, it was the only loom there was among all kinds of people in prehistoric and early historic times (

Þórsdóttir 2019, pp. 20–23). How, and when, us Sámi started weaving is in itself a topic interesting enough for a research project, but this goes far beyond my effort. Marta Hoffmann’s Ph D on the warp-weighted loom from 1964 mentions Sámi weaving among other people’s also. Her extensive work is outstanding in the field of textile (pre-)history, and she is still the number one among researchers who have shown interest in this subject. In her study, she investigates the roots of the

rana/rátnu/grenevev she found traces of among the Sea Sámi in the valleys of North Norway, among rural people in eastern Norway and among Skoltsámi in Northern Finland. How and when us Sàmi started to weave cannot be determined, according to Hoffmann, but she refers to Asbjörn Nesheim who believes Sámi people adopted the warp-weighted loom sometime around 6–700 AD (

Nesheim 1954, p. 32;

Hoffmann 1964, p. 74). My personal belief is that what now is considered to be Sámi weaving is a complex conglomerate of different components born in contact with other ethnicities/cultural identities. Ethnicity is by most scholars today believed to arise in contact, not in isolation, drawing upon Fredrik Barth’s work from 1969. For me it is not the main thing that Sámi weaving (and other cultural activity) is uniquely Sámi. It might not be important at all. What matters is that Sámi people weave and make art, choosing among all knowledge that is available among humans at a certain time and place. For instance, some Medieval silver jewelry, once common among many ethnic groups, remained among the Sámi and today are considered typically Sámi. The same goes for the beaked shoes and the

gapta/kolt.

It is interesting that the warp-weighted loom survived until around the same time among the Sea Sámi of the North and the rural people in Hordaland, Osteröy region, North east of Bergen, much further south, the 1950s. Marta Hoffmann personally witnessed warp-weighted looms in use in Northern Finland among the Skolt Sámi as late as 1955. The reason for the survival of the ancient loom in these particular areas is unknown. Asbjörn Nesheim investigated Sámi technical terms concerned with looms and fixed a

terminus ante quem for the Sámi adoption of warp-weighted looms from their geographical neighbors (

Hoffmann 1964, pp. 11, 75). Everything points at the area among the Sea Sámi in the district of Malangenfjord south of Tromsö, according to Nesheim (

Hoffmann 1964, p. 75).

Textile production in prehistoric times in Scandinavia was solely a female business (

Þórsdóttir 2019, p. 32). Archaeological finds of spindle whorls, looms, warp-weights, et cetera, are only found in female graves or in habitable spaces related to female activity. What we mean with

female or

women in the archaeological record is of course a matter of critical discussion. I refer to my PhD on this subject linked to textile production and images of women, femininity and androgyny in tapestries during the Christianization period in Scandinavia (

Göransson 1999).

4.9. Máhcahit Árbbi/to Reclaim the Heritage by Reconnective Weaving

Decolonization is not an individual choice, Dakota scholar Kim Tallbear states (

Tallbear 2018, p. 152). Indigenous people are in need of the collective. I am in need of others in order to reconnect to my cultural heritage and in order to be heard and seen and confirmed in the decolonization process. We need to make kin, to create new family bonds with each other and with the land.

In Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land, I outline possible methods for an artistically grounded decolonization process, letting practice-based artistic research constitute the foundational tool for such an endeavor. The activist aspect of the artistic research will in a future continuation of the project be set in motion together with other people in the very making process. This will complement the individual work in a way that both let me develop a personal attachment to traditional knowledge and new attachment patterns together with others. In my family, Sámi cultural identity was silenced. We were Forest Sámi and Sea Sámi, the first to be assimilated in a policy that only recognized large scale rein deer herders as Sámi. Our lands were stolen, our language was erased, our music and songs were stopped, our garments were hidden and burned, and we were gradually being labeled as Swedish/Norwegian workers, fishermen, settlers and farmers in official documents, even though we were Sámi. Our culture was considered of lower value. This made us ashamed. Colonization was acted out on us collectively, and decolonization has to be done likewise. It is together that we heal.

My ancestor Adam Kristoffersson was sent to priestly training by force when he was 10 years old. His father Kristoffer protested and said, “Over my dead body that I will send the boy to school in Lycksele” but of course he had to let him go. This created an inherited trauma of forced Christianization in my family. Later, Adam became a bell ringer and psalm singer in Åsele church for many years, not a priest as was intended. In the village where he lived, people today still talk about one of his first missions: to persuade the noaidi/shaman to stop practicing his knowledge and using the drum. I can only imagine Adams’ anxiety and the mixed feelings regarding this assignment.

I now weave to reconnect with my Sea Sámi foremothers. I also stretch out to my Sámi fellows today in order to

make kin.

Making kin is a term launched in Sámi contexts by scholar and

duojjar Liisa Rávná Finbog with reference to Dakota scholar Kim Tallbear, among others. She quotes Tallbear:

Making kin is to make people into familiars in order to relate (

Finbog 2023, p. 18;

Tallbear 2016). Finbog argues that making kin is crucial to finding ones’ identity as a Sámi today. She stresses that forging kinship comes with all kinds of relations: human, non-human beings, entities, land, water in respect and reciprocity (

Finbog 2023, p. 17). Finbog also draws upon Donna Haraway who claims “

We require each other… We become with each other”. Indigenous knowledge systems have been silenced, she continues (

Hoffmann 1964, p. 22). She early discovered the close connections between people who rediscovered their Sámi heritage and duodji: Sámi craft. From early childhood, duodji functioned as a means to connect with her Sámi heritage. Finbog also stresses the importance of reciprocal communication with the Earth—Gulahallat—the act of listening to and communicating with Nature, to/with our fellow creatures, animals, birds, wind, sky and the Earth with reference to Harald Gaski, Sámi author and professor in Sámi literature (

Gaski 2019, p. 262). The recent

joik (Sámi song)

Gulahallat eatnamin, Listening/speaking to the Earth, composed by Sara Marielle Gaup Beaska for the Climate Meeting in Paris 2015, is a beautiful piece of art expressing this approach and way of living that has inspired my own work.

5. Discussion

The research was undertaken by and through the artistic process itself. Us two artists in Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land have different views of it, which is shown in our separate articles in the present publication. For me, the aim is foremost to give voice to the silenced Sámi people by means of weaving, singing and writing, linking spirituality to textile duodji, daidda and arbediehtu, traditional Sámi knowledge. In the beginning of the project, I looked upon the collaboration as an artistic form of reconciliation. By collaborating with a non-Sámi musician, composer and theologian, I found the artwork itself as an act of healing between our peoples. Now, when the work is finished, this point of view is altered.

Art may, if we let it, have a position “in between”. It can affect societal power institutions, without being a part of them, and may serve as a vehicle for transformation and societal change. That is, however, not to render art a solely beneficial role for society by nature. Quite a few contemporary indigenous artists choose to work along a similar path today, as previously shown in this article.

The “in between-ness” of this way of perceiving art is, however, somewhat problematic. It gives art a freedom of political expression and action that may open doors to act upon power institutions responsible for colonization such as the Church or the large national museums of today. At the same time, this brings with it a risk for reducing art to a be societal benefactor, like a cultural band aid that covers and masks what the institutions in question have been/are responsible for versus indigenous people. My standpoint is that art needs to exist and operate in a free space but that it still can be a valuable tool for decolonizing processes. Awareness of and independence from the power institutions indigenous artists collaborate with is, however, crucial. The critically outspoken historical analysis must never be silenced, no matter the decolonizing efforts of today.

In the Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land project, we chose the sacred space of the Scandinavian Christian church as the arena for our performance. This fact can be discussed. It is problematic to bring a performance that has a decolonizing ambition into a space heavily associated by colonization itself. My personal standpoint has been fluctuating during the years of artistic production. Now, when the end of the project is here, I look upon the performances made mainly in the form of a free-standing artworks that gives voice to Sàmi spirituality in established Christian spaces. These spaces were once the arenas for exclusion, banning and punishment of Sámi spirituality other than the one sanctioned by the established Church and the nation states.

Sámi voices were, by means of Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land, invited, heard and confirmed in three Christian spaces in Scandinavia: Sigtuna foundation in Sweden, in St:a Anna church in Kökar, Åland, and finally in Turku Cathedral, Turku, Finland. All three are examples of sacred spaces of the majority religion in Scandinavia from different periods of time. The conditions in these spaces vary. Sigtuna foundation is a Christian space outside the Church; it is not part of the established power institutions but is more of a space with focus on ecumenical collaboration, solidarity and the human rights movement. Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land was performed during the culture days at Sigtuna foundation, where a large audience from inside and outside of the established churches attended. At Kökar, the performance was held in a small medieval church established in the Catholic period during the Franciskus feast, dedicated to the Catholic saint now associated with environmental awareness and ecology. The Cathedral of Turku, finally, is of course of a different dignity, being more of a symbol for churchly power and a more restricted spirituality. The performances at these different places were different, both regarding musical character and the way they were received by the audiences, even though I cannot go into details here and now on this matter.

If the results of the performances and the project as a whole will be reconciliation in the end is unknown, even though the project clearly can be placed with the decolonization process. In order for reconciliation to happen, there is need for societal change outside the church and the sacred spaces as well. This is far beyond what our project can accomplish. We have given voice, but what is needed in order for true transformation is that people—both Sámi and majority people—listen and then act. Awareness must be set in motion in the form of politic action and societal change.

6. Conclusions

In the article, I develop my reflections on the artistic as well as the political aspects of the work and, simultaneously, on how it can be a seen as a vehicle for artistic freedom of expression of indigenous voices in sacred spaces of our time. The artwork Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat/Spirit Land is an artistic performance that may function as a ceremonial act of liberation from the silence of the colonized past. As such it may be a tool for awareness, which, in its turn, may inspire to societal change.

I see weaving as a spiritual practice, linked to the ancestral wisdom of Sámi árbediehtu. As such, it may function as a decolonizing tool for social change that involves restoration. Sámi spirituality was disciplined and, in some cases, also totally erased and banned. The Church and other worldly power institutions in Scandinavia acted out these colonizing strategies from the Middle Ages and forwards. The spiritual colonization almost entirely excommunicated the Feminine Divine from people’s lives.

The three monumental wall hangings Vuolleaibmi/Underworld, Eana/Earth and Albmi/Heaven have been produced by my hand during two years’ time on a large tapestry loom in my studio in Gotland, Sweden. They are artistic representations of three spheres in Sámi cosmology, each and every one with their own character, color scheme and unique artistic expression. The wall hangings are rooted in Sámi weaving traditions from the Sea Sámi areas in North Norway but have expanded from there regarding format, design and material. The enlarged and liberated ranas/rátnus step up from the silenced past and become material embodiments of the spiritual dimensions of landscapes. These landscapes are of different kinds: the one we are surrounded by in our lives on Earth, the one that embraces the past, with the ancestors and divine beings connected to the underworld. Further on, it also includes Heaven, the sphere of light that shines through all that is alive.

The fourth and invisible weave is the enigmatic Dat dovddus ođđa/The New Unknown, the site-specific and ethereal weave that is composed in the sacred space every time Spirit Land is performed. The musical movement Dat dovddus ođđa/The New Unknown does not have an accompanying weave in textile form. In the beginning of the project, this puzzled me. Somewhere in the middle of the research process, I realized that the fourth weave was site and time specific, that it was created in space–time whenever we performed Spirit Land to an audience. Here is where decolonization and maybe even reconciliation may happen.

A part of the artistic work consists of four poems that introduces each weave and each movement in the musical part of Spirit Land to the audience during the performance. The poetry, read out loud by me, functions as a guide for the audience, leading them by the hand through each cosmological sphere. The poems are based on traditional Sámi spirituality as I have been taught from childhood.

I have composed the joik Albmi/Heaven, who is integrated is the musical composition’s movement III Albmi/Heaven and movement IV Dat dovddus ođđa/The New Unknown. Sonically, it spans between airy and soft to powerful, anchored rhythms. Heaven is not just light and air; it is also dark and infinite space, northern light and thunder. For me personally, it was a great empowerment to be invited into the musical part of the artwork. The silenced voice of my family was restored. I sang for myself and for my people. I sang in the sacred spaces where our songs were excommunicated and punished. Our voices were shut down and tamed when only Christian psalms were allowed. It was a great moment of healing for me when the joik Albmi was invited and confirmed in three sacred spaces of our time.

In the article, I entered the spiritual dimensions of the weaving process—each cosmological realm—and wrote from the depth of them, merging these with experiences from the depth of my own inner self. I wrote from the inside of the artistic process, from the choices of color and materials, as well as from the inside of the core of Sámi spirituality. I wrote from the source. The texts that appeared on the page were created in a state of transcendence and deep contemplation. In them, I searched for the Feminine Divine, instead of God the Father. I searched for Her, in order to replace patriarchal hierarchy with the feminine cycles of the Spirit.

I wrote forward a context of indigenous feminism for my artistic work in Spirit Land. I place it in a methodological and theoretical web of indigenous artistic and practice-based research that revolutionizes the academic field. This kind of research is not neutral, detached and “true”. It aims at social and political change and involves the personal and the spiritual as it has been done for thousands of years in arbediehtu, Sámi traditional knowledge.

By claiming that weaving is a spiritual practice, I make it a feminist endeavor. I have woven a theology of the Feminine Divine in textile form. By the hands of Frank Berger and myself, the weaving process was given voice by means of music and spoken words.

- Closing words

- I have woven the Spirit.

- She was given voice

- in a space that prepared for me.

- The door opened, and I was invited.

- I started singing and drumming with my eyes closed.

- When I opened my eyes, later,

- I could see that I no longer was alone.

- We were together, holding hands,

- meeting the warmth of people smiling in our direction.