Creative Flow in Musical Composition—How My Studies in Chi Energy Shaped My Creativity as a Composer

Abstract

1. Backstory

2. Methodology

2.1. Autoethnography as a Method to Understand Cultural Experiences

2.2. My Position of Power

3. The First Building Blocks and Ethical Considerations

3.1. The Underworld

3.2. The Earth

3.3. The Heaven

3.4. The Way Forward

3.5. The Struggle

4. The Composing Process

4.1. TTM—Thai Traditional Medicine

4.2. Flow in Creativity

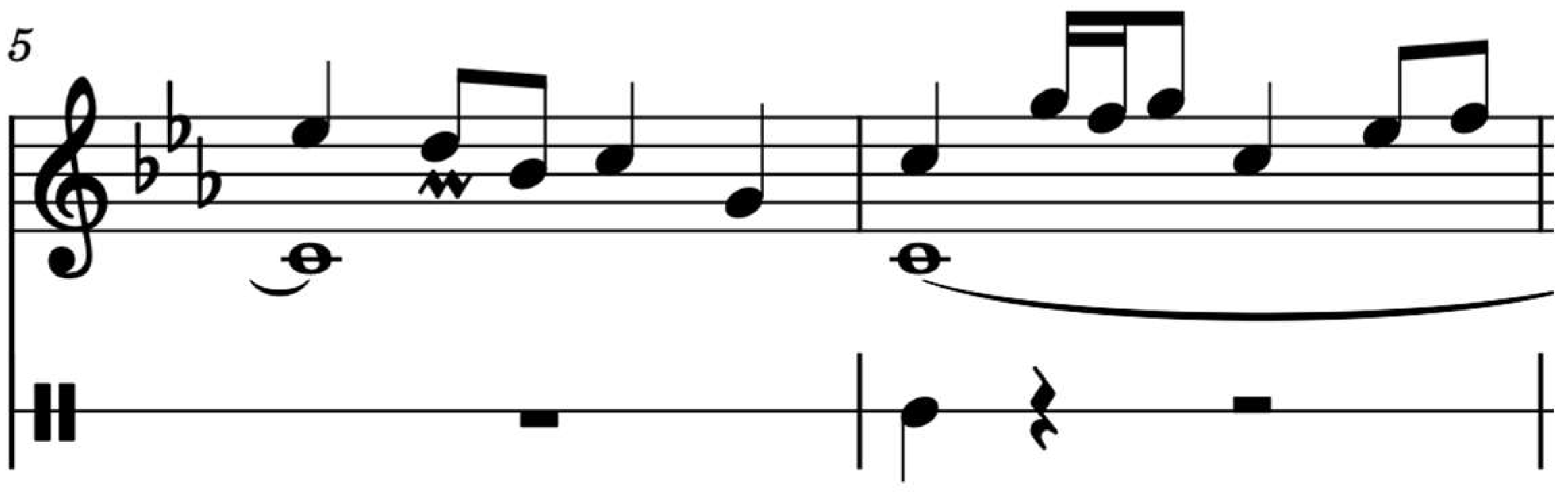

4.2.1. Composing the Underworld

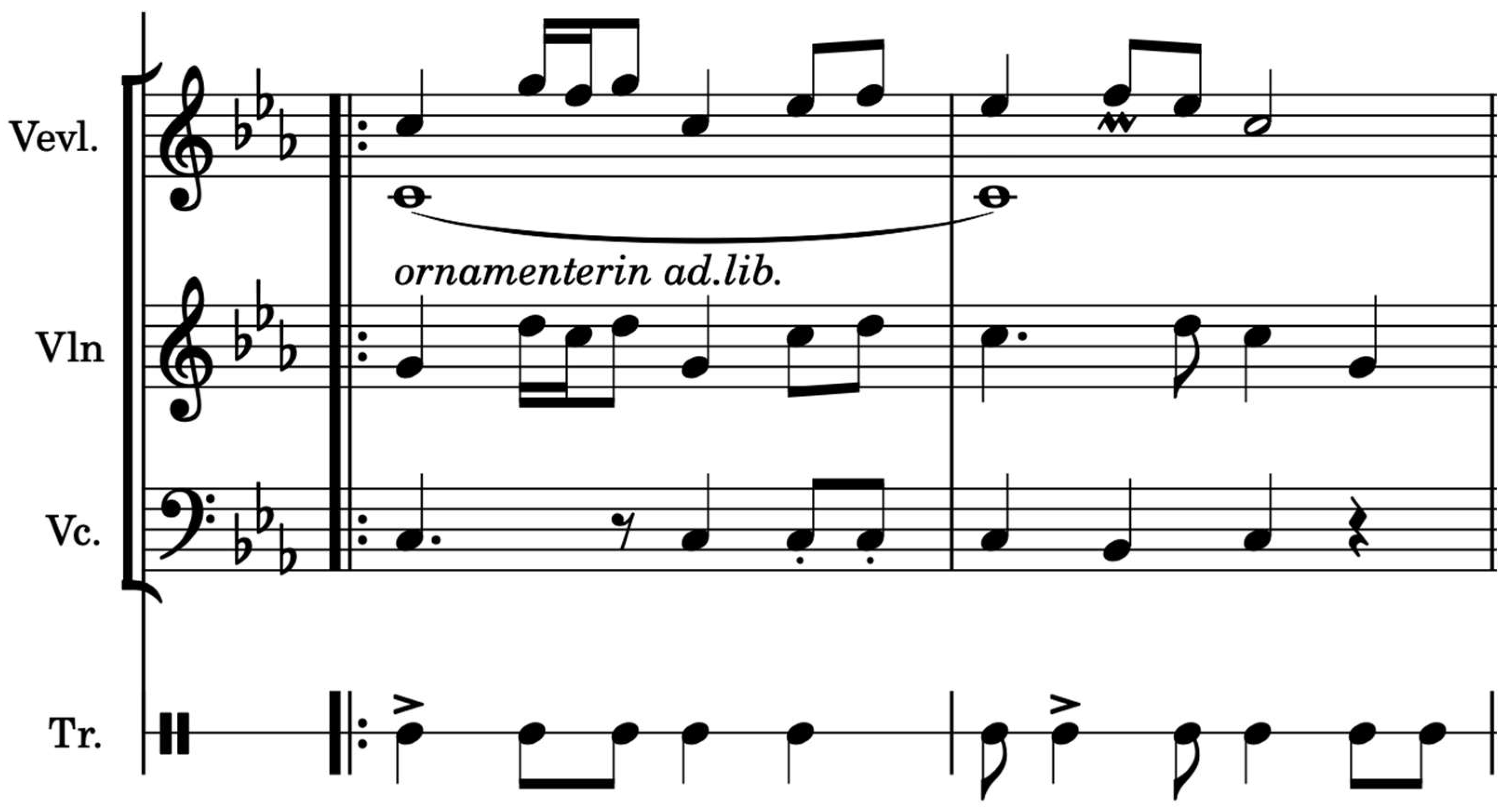

4.2.2. Composing the Earth

4.2.3. Composing the Heaven

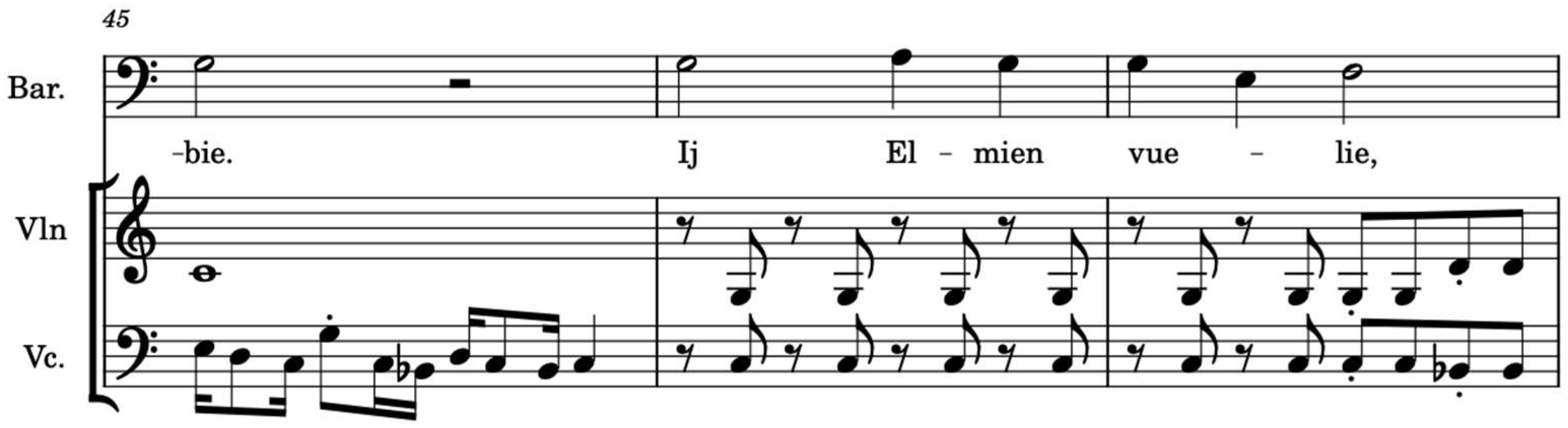

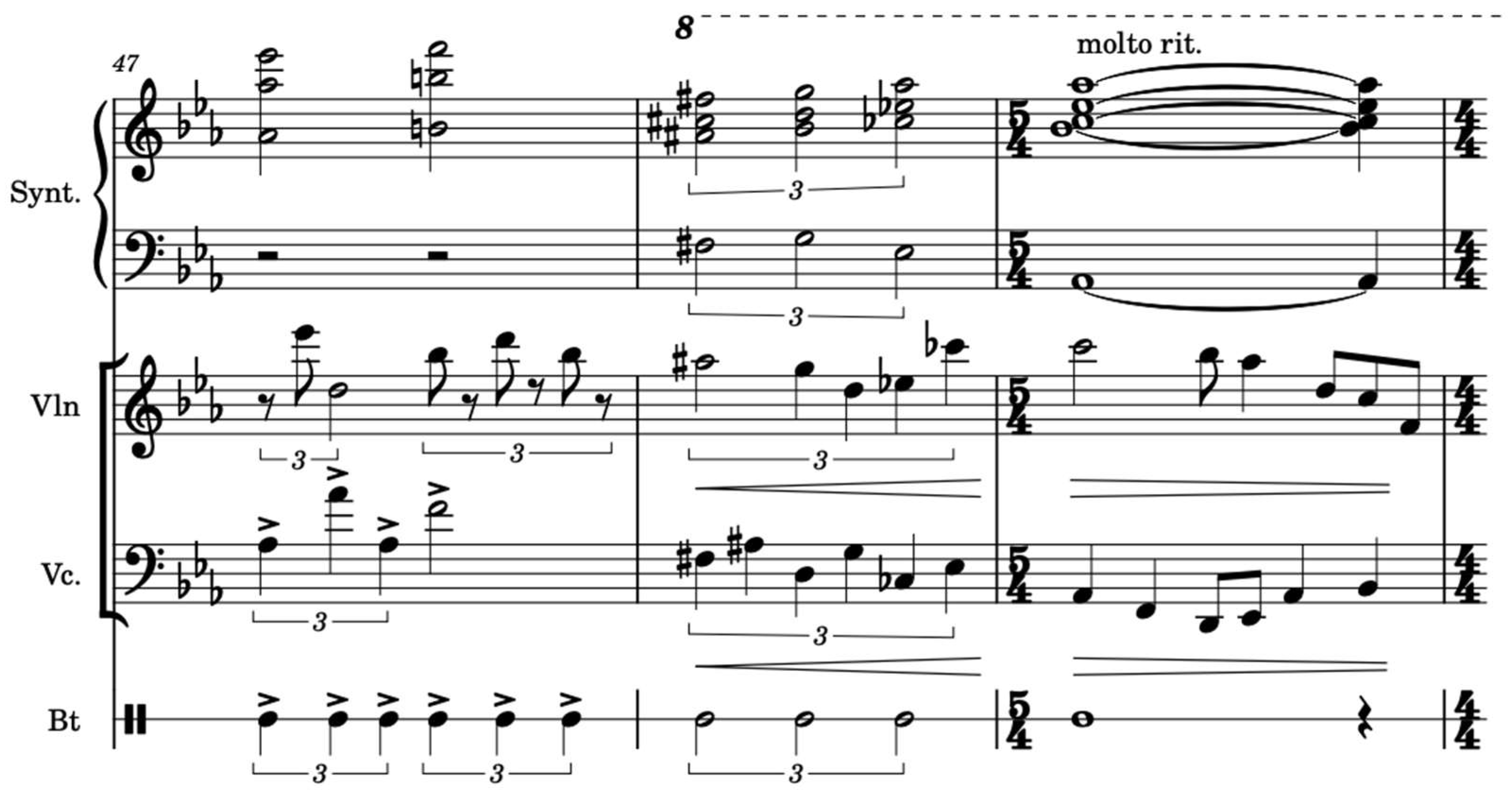

4.2.4. Composing the New Beginning

5. Lessons Learned

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Emma Göransson Almroth is likewise preparing an article on Spirit Land/Vuoiŋŋalaš Eanadat, entitled Weaving the Spirit of Indigenous Feminism (Göransson forthcoming). |

| 2 | Photos or images of such symbols are rarely published. Sámi filmmaker Suvi West made a film in 2024 about Sámi objects from the collections of the National Museum of Finland that were returned to Sápmi. The film emphasises that the Sámi themselves hold the right to interpret their cultural objects, and West conveys that the ancestors are present in the everyday items that were once stolen or purchased and removed from Sápmi by collectors. The drums are considered especially sacred, functioning as a unique link to the ancestors, and in the film West and her cameraman decided not to film old Sámi drums in European museums (West and Kömi 2024). I have not found any photographs or images of the symbols referred to by Mulk and Bayliss-Smith, which I interpret as an act of respect. For this reason, I have likewise chosen not to include any images of ancient Sámi symbols in this paper. |

| 3 | The hymn Härlig är jorden is included in the Finnish, Finland-Swedish, Norwegian, and Swedish Lutheran hymnbooks, all available online through the churches’ official websites: Finnish (Maa on niin kaunis) https://virsikirja.fi/virsi-30-maa-on-niin-kaunis/ (Finlands Evangelisk-Lutherska Kyrka n.d.a); Norwegian (Deilig er jorden) https://www.kirken.no/globalassets/kirken.no/om-kirken/kulturliv/salmer-og-kirkemusikk/deilig%20er%20jorden%20n13%2048.pdf (Kirken i Norge n.d.); Swedish (Härlig är jorden), found in both the Swedish and the Fenno-Swedish hymbooks, https://www.svenskakyrkan.se/psalmboken/kanda-psalmer (Svenska kyrkan n.d.) https://psalmbok.fi/psalm-31-harlig-ar-jorden/ (Finlands Evangelisk-Lutherska Kyrka n.d.b); and in South Sámi translation (Eatneme tjaebpies) within the Agenda for the Service of Reconciliation (Svenska Kyrkans Ursäkt Till det Samiska Folket n.d.). (All accessed on 31 August 2025). |

| 4 | The hurdy-gurdy is a drone-based instrument. Mine is tuned in C and G, so I can use either of those as the tonal base. |

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2010. Vithetens fenomenologi. Tidskrift för Genusvetenskap 31: 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An Official Website of Old Medicine Hospital Thai Massage School Shivagakomparpaj. n.d. Available online: https://www.oldmedicine.org/ (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Berger, Frank. 2025a. De Kunde Bränna Våra Trummor, Men Aldrig Bränna Våra Röster. Kummin 6–7: 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Frank. 2025b. Kyrkan Som Kolonialmakt—Hur Går vi Vidare? Nyckeln. Available online: https://www.nyckeln.net/kultur-omvarld/kyrkan-som-kolonialmakt-hur-gr-vi-vidare (accessed on 31 August 2025). (Photographs by Eduardo Abrantes).

- Bråkenhielm, Carl Reinhold. 2017. Den nedbrutna skiljemuren. In Samerna och Svenska kyrkan. Underlag för Kyrkligt Försoningsarbete. Edited by Daniel Lindmark and Olle Sundström. Möklinta: Gidlunds Förlag. [Google Scholar]

- Bredal-Tomren, Tom Sverre. 2023. Sámi ecotheology as a resource for the church of Norway. An ecocritical analysis of two Sámi ecotheologians. Studia Theological—Nordic Journal of Theology 77: 231–50. Available online: https://vid.brage.unit.no/vid-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/3107746/Sami%2becotheology%2bas%2ba%2bresource%2bfor%2bthe%2bchurch%2bof%2bNorway.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 13 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Carolyn, Tony E. Adams, and Arthur P. Bochner. 2011. Autoethnography: An Overview. Historical Social Research 36: 273–90. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, Yvonne, and Anette Göthlund. 2017. Kroppsliga uttryck—Iscensatta kön. In Möte med Bilder, Att Tolka Visuella Uttryck. Lund: Studentlitteratur. [Google Scholar]

- Finlands Evangelisk-Lutherska Kyrka. n.d.a Virsikirja: Maa on niin kaunis. Available online: https://virsikirja.fi/virsi-30-maa-on-niin-kaunis/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Finlands Evangelisk-Lutherska Kyrka. n.d.b Finlands Evangelisk-Lutherska Kyrka. Psalmbok: Härlig är jorden/Psalm 31. Available online: https://psalmbok.fi/psalm-31-harlig-ar-jorden/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Fjällgren, Jon Henrik. 2020. Månbarn—Min Berättelse. Stockholm: The Book Affair. [Google Scholar]

- Fur, Gunlög. 2017. Kolonialism och kulturmöten under 1600- och 1700-talen. In Samerna och Svenska Kyrkan. Underlag för Kyrkligt Försoningsarbete. Edited by Daniel Lindmark and Olle Sundström. Möklinta: Gidlunds Förlag. [Google Scholar]

- Gander, Kashmira. 2014. Conchita Wurst’s Eurovision 2014 Win Caused Balkan Floods, Says Serbian Church Leader. Independent. May 22. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/news/god-punished-balkans-with-floods-for-conchita-wurst-s-eurovision-2014-win-says-serbian-church-leader-9419300.html (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Gaup Beaska, Sara Marielle. 2015. Gulahallat Eatnamiin: We Speak Earth. Available online: https://youtu.be/H2LhBAi-Q8I?si=x86k6TblPwZzda9M (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Gaztambide-Fernández, Rubén. 2019. Decolonial Options and Artistic Aesthetic Entanglements: An Interview with Walter Mignolo. Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte: Tambapanni Publishers. Available online: https://www.tambapannipublishers.lk/decolonial-options-and-artistic-aesthesic-entanglementsi-an-interview-with-walter-mignolo (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Göransson, Emma. 2017. Postnomadiska Landskap. Stockholm: Arkitektur Och Designcentrum. [Google Scholar]

- Göransson, Emma. forthcoming. Weaving the Spirit of Indigenous Feminism. Arts.

- Hagelin, Lotta. 2023. Colonial Continuity in Finland: Cultural Appropriation of Sámi Design. Available online: https://no-niin.com/issue-21/colonial-continuity-in-finland-cultural-appropriation-of-sami-design/index.html (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Hämäläinen, Soile, Frauke Musial, Ola Graff, Henrik Schirme, Anita Salamonsen, and Grete Mehus. 2020. The art of yoik in care: Sami caregivers’ experiences in dementia care in Northern Norway. Nordic Journal of Arts, Culture and Health 2: 22–37. Available online: https://www.scup.com/doi/10.18261/issn.2535-7913-2020-01-03 (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Hämäläinen, Soile Päivikki. 2023. “I Sound”—Yoik as Embodied Health Knowledge. Tromsø: The Arctic University of Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Hellsten, Laura. 2025. Norrskenskatedralen som fallstudie för hur kritisk granskning av teologiska föreställningsrymder kan bidra till de-kolonisation. In Finsk Tidskrift 5/2025. Alta: Nordlydskatedralen i Alta, pp. 31–55. Available online: https://www.finsktidskrift.fi/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Finsk_Tidskrift_nro_5_2025_Hellsten_Laura.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- IWGIA (International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs). 2025. The Sámi People. Available online: https://iwgia.org/en/sapmi.html (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Johnsen, Tore. 2017. Erkänd historia och förnyade relationer: Perspektiv på försoningsarbetet mellan kyrkan och samerna. In Samerna och Svenska kyrkan. Underlag för Kyrkligt Försoningsarbete. Edited by Daniel Lindmark and Olle Sundström. Möklinta: Gidlunds Förlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kirken i Norge. n.d. Deilig er jorden. Available online: https://www.kirken.no/globalassets/kirken.no/om-kirken/kulturliv/salmer-og-kirkemusikk/deilig%20er%20jorden%20n13%2048.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Kjellström, Rolv, Gunnar Ternhag, and Håkand Rydving. 1988. Om Jojk. Möklinta: Gidlunds Förlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kraft, Siv Ellen. 2020. Spiritual Activism. Saving Mother Earth in Sápmi. Religions 11: 342. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/11/7/342? (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Lindberg, Anna-Lena. 2002. Den Maskulina Mystiken, Kropp, Kön och Ideal. Lund: Studentlitteratur. [Google Scholar]

- Lundmark, Bo. 2016. Medeltida vittnesbörd om samerna och den katolska kyrkan. In De Historiska Relationerna Mellan Svenska Kyrkan och Samerna: En Vetenskaplig Antologi. Skellefteå: Artos & Norma, pp. 221–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mulk, Inga-Maria, and Tim Bayliss-Smith. 2007. Liminality, Rock Art and the Sami Sacred Landscape. Journal of Northern Studies 1: 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norlin, Björn. 2017. Kyrkan och samiska kulturella uttryck. In Samerna och Svenska kyrkan. Underlag för Kyrkligt försoningsarbete. Edited by Daniel Lindmark and Olle Sundström. Möklinta: Gidlunds Förlag. [Google Scholar]

- Nyyssönen, Jukka. 2013. Sami Counter-Narratives of Colonial Finland. Articulation, Reception and the Boundaries of the Politically Possible. Acta Borealia: A Nordic Journal of Circumpolar Societies 30: 101–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Rick. 2023. The Creative Act. A Way of Being. London: Penguin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salguero, C. Pierce. 2007. Traditional Thai Medicine: Buddhism, Animism, Ayurveda. Chino Valley: Hohm Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sigtunastiftelsen. 2025. Spirit Land—Ett Textilt och Musikaliskt Allkonstverk. Available online: https://sigtunastiftelsen.se/events/spirit-land-ett-textilt-och-musikaliskt-allkonstverk/ (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Sjöberg, Lovisa Mienna. 2018. Att Leva i Ständig Välsignelse. En Studie av Sivdnidit som Religiös Praxis. Ph.D. thesis, Teologisk Fakultet, Universitetet i Oslo, Oslo, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Smalbrugge, Matthias. 2019. Modern Christianity, Part of the Cultural Wars. The Challenge of a Visual Culture. Religion and Transformation in Contemporary World 10: 299. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/10/5/299 (accessed on 12 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies. London: Zed Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Stoor, Krister. 2007. Juoiganmuitalusat—Jojkberättelser. En Studie av Jojkens Narrativa Egenskaper. Ph.D. thesis, Samiska Studier, Umeå Universitet, Umeå, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Svalastog, Anna Lydia, Shawn Wilson, Harald Gaski, Kate Senior, and Richard Chenhall. 2021. Double Perspective in the Colonial Present. Social Theory & Health 20: 215–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svenska kyrkan. n.d. Psalmbok: Härlig är jorden. Available online: https://www.svenskakyrkan.se/psalmboken/kanda-psalmer (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Svenska Kyrkans Ursäkt Till det Samiska Folket. n.d. Agenda för gudstjänsten vid ärkebiskop Antje Jackeléns ursäkt till det samiska folket. Available online: https://www.svenskakyrkan.se/samiska/ursakt-till-det-samiska-folket (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- TallBear, Kim. 2014. Standing With and Speaking as Faith: A Feminist-Indigenous Approach to Inquiry. Journal of Research Practice 10: N17. Available online: https://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/405/371.html (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Thai Massage School Shivagakomarpaj. n.d. Hand Book for Therapeutic Thai Massage Course, Level 4. Chiang Mai: Thai Massage School Shivagakomarpaj.

- Timmy’s Massage Training Center. n.d. Available online: https://timmy.thaistylemassage.com/en/about-timmy.html (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. 2012. Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1: 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2019. Nuad Thai, Traditional Thai Massage. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/nuad-thai-traditional-thai-massage-01384/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Valjakka, Mari. 2025. Sämmiliih Kirhoost—Sä’mmla Ceerkvest—Sápmelaččat Girkus—Saamelaiset Kirkossa (Samer i Kyrkan)—Slutrapport. Projektet Samer i Kyrkan. Available online: https://evl.fi/plus/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2025/04/Samerna-i-kyrkan-Slutrapport-29.1.2025-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Virdi Kroik, Åsa. 2022. Dihte Gievrie—Det vi Möter i Respekt. Berättelser om en Sydsamisk Trumma. Available online: https://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1615505/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- West, Suvi, and Anssi Kömi. 2024. Máhccan—Homecoming [Documentary Film]. Helsinki: Finnish Film Foundation. Available online: https://www.ses.fi/en/catalogue/film/mahccan-homecoming/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berger, F.J.-P. Creative Flow in Musical Composition—How My Studies in Chi Energy Shaped My Creativity as a Composer. Arts 2025, 14, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060141

Berger FJ-P. Creative Flow in Musical Composition—How My Studies in Chi Energy Shaped My Creativity as a Composer. Arts. 2025; 14(6):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060141

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerger, Frank Jens-Peter. 2025. "Creative Flow in Musical Composition—How My Studies in Chi Energy Shaped My Creativity as a Composer" Arts 14, no. 6: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060141

APA StyleBerger, F. J.-P. (2025). Creative Flow in Musical Composition—How My Studies in Chi Energy Shaped My Creativity as a Composer. Arts, 14(6), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060141