1. Introduction

In the twentieth century, greenery interacted with architecture in various ways. The approach to its design evolved—from being treated as a decorative backdrop to being perceived as an integral component of spatial composition, and even as a manifestation of advanced integration between the natural environment and the built space. Modernism in architecture fostered a rational and technical understanding of space, in which designed structures were conceived as forms intended to meet expectations of efficiency, ergonomics, and functionality—essentially as a technical challenge. Within this framework, greenery was also regarded as a functional element, ensuring the hygiene of the living environment and complementing the architectural form.

In the organic movement, represented among others by Wright, the building emerged from the environment in which it was created. In this way, a dialogue developed in twentieth-century architecture between a rational approach to space and the pursuit of preserving its spiritual and symbolic dimensions. Despite the diversity of interpretations within modernism, this movement did not succeed in severing architecture from its cultural meaning—from the connection between abstraction, ideas, and structure on the one hand, and everyday experience as well as the context of place and time on the other (

Vesely 2004).

The contemporary pro-environmental discourse establishes new priorities for architecture. One of its “new” tasks is the creation of infrastructure that supports a wide range of ecosystem services—enhancing the natural environment and mitigating the impacts of climate change. In this context, biophilic architecture has emerged, revealing new possibilities for constructing cultural meaning. Biophilic environments are being created that foster human development in connection with nature, strengthen humanistic and ethical values, and emphasise the importance of human experience within space.

The new poetics of contemporary architecture lies in integrating technology and function with the symbolic and cultural meanings of space. It does not reject modernity but seeks to reconcile it with the human condition, the sense of place, and lived experience. Contemporary architectural thought increasingly assumes a bidirectional relationship between nature and the human world—nature becomes part of architecture, and architecture becomes part of nature. In doing so, it challenges the Cartesian dualism, established since the Enlightenment, that separates the world of the human mind (

Lat. res cogitans) from the material world of nature (

Lat. res extensa) (

Merleau-Ponty 1962;

Latour 1993;

Crutzen 2002).

Technological progress and the evolving reflection on the role of architecture have led to the search for new means of expression. One of the significant directions in this pursuit is biophilic architecture, which promotes environmental values and the idea of harmonious coexistence between humans and nature. Within this framework, immersive techniques—previously associated primarily with the arts—are increasingly being employed. Through the phenomenon of immersion, it becomes possible to achieve a deeper, sensory, and emotional experience of space: an engagement that immerses the user in the narrative of a place, thereby enhancing its phenomenological dimension.

However, the issue of immersion in architecture requires further research. It is complex and transdisciplinary, encompassing various research orientations—focused on the object, the subject, or the relationship between them—and is characterised by definitional ambiguity (

Freitag et al. 2020) and the absence of an established methodology. The aim of the current research is to deepen the understanding of immersion mechanisms within architectural space and to develop tools for identifying and evaluating the degree of immersiveness in biophilic architectural environments. To this end, the Multi-criteria Method for Assessing Architectural Immersiveness (MMAAI) has been developed.

The research work has been divided into individual sections corresponding to distinct stages of the research process and levels of analysis concerning immersiveness in biophilic architecture.

Section 1 provides a general introduction to the subject, in which the authors outline the main assumptions.

Section 2, the theoretical part, discusses the concept of immersiveness and its relationship to biophilic architecture.

Section 3 presents the research methodology, explaining the criteria used for assessing immersiveness in the examined architectural objects, as well as the methods of evaluation. This constitutes an original and authorial approach to capturing the characteristics and properties of architectural objects oriented towards biophilia.

Section 4 and

Section 5, the empirical part, contain the analysis of selected case studies and present the results.

Section 6 offers a discussion of the research findings, including an examination of the possibilities and limitations of studying immersiveness in biophilic architecture and, more broadly, a comparison with other research approaches.

2. Theoretical Foundations of the Phenomenon of Immersion in Art and Architecture

2.1. Sources of Immersion

The term

immersion derives from the Latin word

immersio, meaning “to submerge” or “plunging” (

Glare 2012). It began to be employed in the early twenty-first century within media theory and digital aesthetics. These disciplines contributed to the development of a new mode of perceiving virtual reality, opening up new possibilities for user interaction and participation in immersive narratives. The recipient thus became a co-participant in the story, engaging actively and emotionally in the experience.

Murray (

1997) emphasises that this initiative originated with the audience, driven by a desire for affective experiences. The distinction between the roles of creator and recipient has become blurred and subject to reflection within the context of advancing technology. Regarding immersion, He writes:

“We seek the same feeling in psychological immersion that we do when we plunge into the ocean or a swimming pool: the sensation of being surrounded by a completely different reality, as different as water is from air, which absorbs all our attention, our entire perceptual apparatus”

Ryan (

2001) expanded research into immersion and interactivity in the digital realm, highlighting how the concept operates from both a technological (production-oriented) and a phenomenological (reception-oriented) perspective, which complicates the formulation of its theoretical foundations. She described the transfer of real-world experience, its meaning and value, into the virtual domain—that of electronic literature and digital media—where, through immersion “in the text” and imagination, the boundary between fiction and reality becomes blurred. Ryan also identified differences in the nature of participation between immersion in digital literature and in media. In both cases, however, the crystallising element is the narrative experience, which engages the audience in a multidimensional manner. The text, as a narrative medium, enables entry into an alternative world in which the recipient constructs their own narrative as the source of their experience (

Ryan 2001).

Understanding this phenomenon requires a purely theoretical perspective, one provided by the philosophy of literature. In the first half of the nineteenth century,

Coleridge (

[1817] 1983) described the act of suspending one’s control over reality when engaging with literature or fictional narratives—a detachment known as the principle of the

willing suspension of disbelief—and the capacity to experience the story and the fictional world as part of an implicit agreement between the literary creator and the reader. This agreement suggests that literary works are capable of evoking genuine emotions.

Ingarden (

[1931] 1973,

1960) emphasised the role of the reader, who, through the use of imagination, is able to complete what remains undefined, metaphorical, or ephemeral in the text, thereby making it more complete and personal. Similarly,

Iser (

[1976] 1978) identified the open structure of the text, which contains “gaps” (

Leerstellen) ready to be filled by the reader’s imagined narrative and subsequent interpretation. The act of reading thus creates an interaction between the raw form of the text and the reader’s imagination—a dialogue between author (creator) and interpreter (recipient).

These concepts, rooted in classical literary theory, account for some of the mechanisms underlying immersion in digital media. Intervening in the narrative, interacting through imagination, and constructing an experiential reality enable multidimensional forms of engagement.

Ryan (

2001) further argues that immersion requires the internal coherence of the presented world, the creation of a referential illusion, and the appropriate disposition on the part of the recipient.

Freitag et al. define

immersiveness as “an inherent property of objects in general, and of mediated objects in particular, and thus of delineated real and imagined spaces” (

Freitag et al. 2020, p. 2). In this paper, we maintain a conceptual distinction: immersiveness refers to the qualities of an object, whereas immersion denotes a process or a state of mind.

2.2. Immersive Art

Media art has also drawn inspiration from classical art forms, such as the nineteenth-century panoramic paintings, illusionist theatre, and twentieth-century installation art. In his book

Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion,

Grau (

2004) discusses environments as a key form of immersive physical art and a precursor to virtual experiences. These are spatial installations, developed since the 1960s, in which the viewer is not merely an observer but enters a world created by the artist, allowing for full immersion in the artwork. The mechanism of immersion within environments is based on surrounding the viewer and engaging their senses, thereby eliminating the classical distance between artwork and audience. According to

Grau (

2004), environments represent a significant stage in the history of art, as their spatial, lighting, and interactive solutions inspired later immersive techniques employed in digital media and virtual reality.

Experiences constructed around narrative—employing interactivity, participation, and co-creation—have generated a synergistic force of multidimensional and personal engagement, which contemporary artists continue to harness in various forms of presentation. A crucial variable in art, and one that distinguishes digital media art, is the role of place as a spatial representation—a physical, material layer around which the experience is constructed.

Grau (

2004) describes the transfer of technology and experiential approaches into contemporary art and artistic spaces. Digital technologies have amplified multisensory immersive experiences through the combined power of art, technology, and audience perception, encapsulated in the concept of virtual art.

Architecture is inherently bound to place and its material presence. Hermeneutic and phenomenological approaches emphasise its capacity to generate meanings, values, and significance, as well as its ability to communicate with users of space through the physicality of place itself.

Vesely (

2004) pointed to the tension between architecture’s symbolic and communicative functions and its role as a medium for conveying a “message.” In immersive art, these boundaries become less distinct, and public space and architecture acquire substantial educational potential, enabling shared interpretations of context and meaning (

Greeno 2006;

Suthers 2006).

This occurs through mechanisms of collaborative learning—by focusing attention on the same element and coordinating mutual awareness (

Tomasello 1995). As a result, architecture supports referential practices and becomes a significant component of social learning. Meaning-making in architecture is multisensory in nature: it is grounded in the perception of sounds, smells, tactile qualities, and the spatial–visual environment, all of which individuals and groups interpret collectively (

Pallasmaa 2012). Actors within architectural space can also collaboratively develop various non-visual practices and action strategies—such as sensory narratives and imaginative practices—that lead to the creation of shared meanings (

Steier 2020).

2.3. Environments

Contemporary architecture—that is, the architecture of the twenty-first century—employs various expressive means derived from immersive art. A clear parallel can be observed in the development of the aforementioned environments. This artistic form has evolved since the 1950s, progressing through several distinct stages. The term environment was popularised by Allan Kaprow, an American critic associated with the happening movement. Kaprow defined the environment as a total space in which the viewer ceases to be a passive recipient and becomes an active participant in the event.

In this context, it is worth referring to the reflections of Bernard Tschumi, who proposes an approach in his architectural practice that closely aligns with the idea of the environment. Tschumi emphasises the dynamic relationship between space, action, and user perception. In his architectural projects, form is not merely an aesthetic object but a medium that organises human experience and behaviour within space. In

Event-Cities, Tschumi stresses that architecture does not determine behaviour but instead creates a context for events and interactions—much like the environment, it engages the viewer in active participation (

Tschumi 1996).

The further development of environments in the 1960s was closely linked to the art of minimalism and conceptualism. During this period, artistic realisations by Claes Oldenburg (e.g.,

The Store), Yayoi Kusama (mirror and light-point rooms), and Edward Kienholz (realistic scenes of everyday life) introduced viewers into spaces designed to engage the senses and emotions (

Bishop 2005). In subsequent decades—the 1970s and 1980s—works explored and tested perceptual possibilities, becoming experimental means at the intersection of art and science. James Turrell and Robert Irwin constructed light environments that examined the viewer’s relationship to space and perception. Bruce Nauman experimented with oppressive spatial structures, in which the viewer encountered bodily and psychological limitations. These explorations often involved modern technologies, such as video projection and spatial sound (

Bishop 2005).

Since the 1990s, immersion has become increasingly central to art, with a strong emphasis on experience and the use of multimedia and interactive media. Artists such as Olafur Eliasson (

The Weather Project; In Real Life) and the collective teamLab have created spaces that envelop the viewer through light, water, projection, and movement (

Bishop 2012;

Eliasson 2003;

teamLab 2018).

In response to critiques of the Anthropocene, an ecological strand of environment art has emerged, offering a deeper reflection on the relationship between humans and nature. Works by Agnes Denes (

Wheatfield—A Confrontation, 1982), Cristina Iglesias (

Falling Garden, 2008;

The Secret Garden, 2010), and Natalie Jeremijenko merge art, science, and ecology to create living, biological environments (

Bishop 2012;

Denes 1982;

Iglesias 2008,

2010;

Jeremijenko 2000). Contemporary environments are frequently integrated with architecture and urban design—art extends beyond the gallery space and becomes embedded within public space, where it serves as a form of communal and landscape experience.

2.4. From Form to Atmosphere: Aesthetic and Phenomenological Perspectives on Immersive Architecture

Polish philosopher specialising in aesthetics, among other areas, Roman Ingarden approached architecture from an aesthetic perspective, describing it through its formal elements, which together constitute its multilayered nature: the physical (materials, construction, form, proportions), the aesthetic and spatial (rhythm, harmony, spatial relations, composition), and the experiential (user sensations and emotions). The primary aim of architecture, according to Ingarden, is to evoke an aesthetic experience, although its formal representation remains significant (

Ingarden 1957,

1966).

The German philosopher and aesthetician Gernot Böhme, in his discourse on architecture, formulated the concept of

atmospheres, thereby bridging the gap between the traditional understanding of aesthetics and the user’s spatial experience (

Böhme 2017). Architecture functions as a medium that stimulates a range of user experiences—emotional, behavioural, and those that shape a sense of belonging—and actively influences the user. Atmosphere is not solely a product of architecture itself but emerges from its interaction with humans. It mediates between the material environment, the objective structure of a place, and the user’s subjective experience. In this sense, responding to human needs becomes the principal task of architecture.

A classical description of form and function thus becomes incomplete without accounting for the individual and collective (communal) dimensions of experience and the associated emotional responses. This provides a methodological orientation for research on immersive architecture.

Wolf (

2013) adds a third crucial element to this framework:

context. Aesthetic illusion, he argues, arises from the free interplay and synthesis of three factors: (a) those inherent to the representation itself, which by nature tends to generate illusion; (b) those related to the process of reception and the recipient; and (c) those belonging to the broader contextual frame—such as cultural-historical, situational, or generic conditions.

The landscape, both in its physical form and as technologically mediated, enhances the immersiveness of space by guiding the viewer through a sequence of views, framed perspectives, and the manipulation of sensory experience. In doing so, it becomes not merely a backdrop but an active component of spatial narrative, engaging the observer on emotional, cognitive, and perceptual levels and deepening the sense of immersion within the environment (

Jóźwik and Jóźwik 2022).

2.5. Biophilic Architecture in the Context of the Philosophy of Nature

Böhme, as a philosopher of nature, opposed the technicisation of nature—the reduction of its significance, its use as a mere object of study, or as a resource to be exploited. He advocated recognising the phenomenon of nature as central to the construction of life quality and its inherent relevance to human existence. Nature produces states and

auras that evoke sensory experiences, provide reasons for emotional engagement, and offer opportunities for immersion (

Böhme 1988).

Although biophilic architecture involves technical solutions, its intended meaning does not rely on the physical utilisation of nature. Rather, it treats nature as a source of experience, atmosphere, and place quality, contributing to a sense of connection with the natural world. Biophilia is defined as a love of nature. Biophilic architecture is a design approach in which the designer integrates natural elements, processes, and patterns into the built environment to support human health, well-being, and the sense of connection with nature, based on the premise that humans possess an innate need for contact with the natural world (

Wilson 1984;

Kellert 2008).

3. Materials and Methods

The research is structured into sections that follow the stages of studying immersiveness in biophilic architecture, beginning with an introduction and theoretical background, followed by methodology, case study analysis, and results. The final section discusses the findings, highlighting both the potential and limitations of examining immersiveness within biophilic architectural contexts and comparing this approach with other research methods.

Research triangulation is achieved through three components: the theoretical section, the empirical section, and the discussion, which juxtaposes the findings with other research perspectives and provides a critical analysis of the results.

Based on the theoretical framework, it is assumed that biophilic architecture—similarly to immersive art—seeks to create spaces in which the user may become fully immersed in the experience, not only visually but also multisensorily and emotionally. Its essence lies in generating atmospheres conducive to a sense of unity between human beings and nature, corresponding to the understanding of immersion as a state of being surrounded by an alternative reality. Within this framework, immersiveness emerges not merely as a consequence of technological means but as the result of the relationship between the human being, space, and nature—where the user actively participates, experiencing an emotional and physical “immersion” in the place. Biophilic architecture thus realises the idea of immersion through harmony between aesthetics, sensoriality, and presence, leading to a profound, affective engagement with the surrounding environment.

In the empirical section (

Section 4), various architectural projects exhibiting characteristics of contemporary biophilic architecture, completed in the twenty-first century, were selected. These projects have the potential to generate specific atmospheres and experiences, employing immersive practices—namely, they facilitate the user’s immersion in a predefined authorial narrative or provide the opportunity for the creation of a personal narrative, allowing for an individual immersive experience.

The following objects were selected for analysis: the rooftop garden—Warsaw University Library (1999); the Musée du Quai Branly—Jacques Chirac—museum of non-European cultures in Paris (2004); the Bosco Verticale residential towers in Milan (2014); the Crossrail Place Roof Garden at Canary Wharf, London (2015); and Eden Dock, Canary Wharf, London (2024). The selection was guided by the following criteria: the chosen buildings represent the architectural character of the twenty-first century, are situated within the European context, and incorporate various forms of greenery integration as one of the key elements of their architectural composition. At a preliminary stage of investigation, it may be assumed that, in these examples, the boundary between vegetation and the remaining architectural structure becomes blurred, allowing the user to experience immersion and to engage with the architectural narrative. In this sense, architecture transforms into a stage for experience rather than merely a utilitarian form. All sites were analysed in situ.

The research premise adopted asserts that an understanding of atmospheres requires, first, comprehension of their spatial characteristics. In turn, understanding spatial atmospheres necessitates an appreciation of their immersive potential (

Freitag et al. 2020). In their case study research, Freitag et al. employ an interdisciplinary method of open dialogue, aimed at identifying both the potentials and limitations of immersiveness as a conceptual framework (

Wolf 2013).

In the study of biophilic immersion within architectural objects, three research levels were highlighted: sensory (biological stimuli), affective (emotions evoked), and phenomenological (being in a given place), which occasionally intersect and reinforce each other synergistically.

The developed original Multicriteria Method for Assessing Architectural Immersiveness (MMAAI) is based on the integration of layers drawn from several frameworks: Ingarden’s layers (physical, aesthetic–spatial, experiential); Böhme’s layers, addressing the study of atmospheric experience and the contribution of immersive practices (sensory, spatial, aesthetic–atmospheric); and Wolf’s layers (psychological–phenomenological, behavioural, technological, narrative coherence, and contextual) (See in

Table 1).

The aim of the qualitative method is to maintain methodological consistency—particularly when applied to diverse types of objects. In this study, alongside the application of assessment criteria, a deepening commentary is employed to capture the specific characteristics of each site. Additionally, indicators and evaluation methods have been proposed that could be further developed towards quantitative approaches. The method is applicable to architectural objects employing immersion-based techniques—i.e., those using various strategies or media to immerse the user.

Evaluation of the objects relied primarily on participant observation, enabling shared experiences, as well as on expert analyses—both spatial and perceptual–phenomenological. Certain features of the objects may coexist and intersect when assessing different aspects of immersiveness.

4. Case Study—Results

Despite the diversity of forms in biophilic architecture, it is possible to refer to its immersive character. Through the synergy of spatial form, function, and meaning, these buildings construct narratives which—when combined with biophilic interventions—affect sensory and affective stimuli, thereby shaping the phenomenological dimension of spatial experience. Biophilic architecture, through a multisensory environment, introduces the user into a state of immersion in which aesthetics, atmosphere, and perception converge into a unified experiential whole.

4.1. The Rooftop Garden—Warsaw University Library (BUW Garden) (1999)

4.1.1. Main Assumptions

The building of the University of Warsaw Library was completed in 1999 as a new headquarters for the library, responding to its increased functional requirements and the need to consolidate dispersed collections in a single location. The architectural design was created by architects Marek Budzyński and Zbigniew Badowski with their team, while the landscape architecture was designed by Irena Bajerska. The complex serves as an example of the integration of architecture and nature in a biophilic spirit. Both the building and the garden construct a coherent narrative concerning the relationship between culture and nature. The key concept is to immerse the user in a space where the boundary between structure and landscape becomes fluid. The project aimed to combine library, educational, and recreational functions while introducing nature into the academic environment (

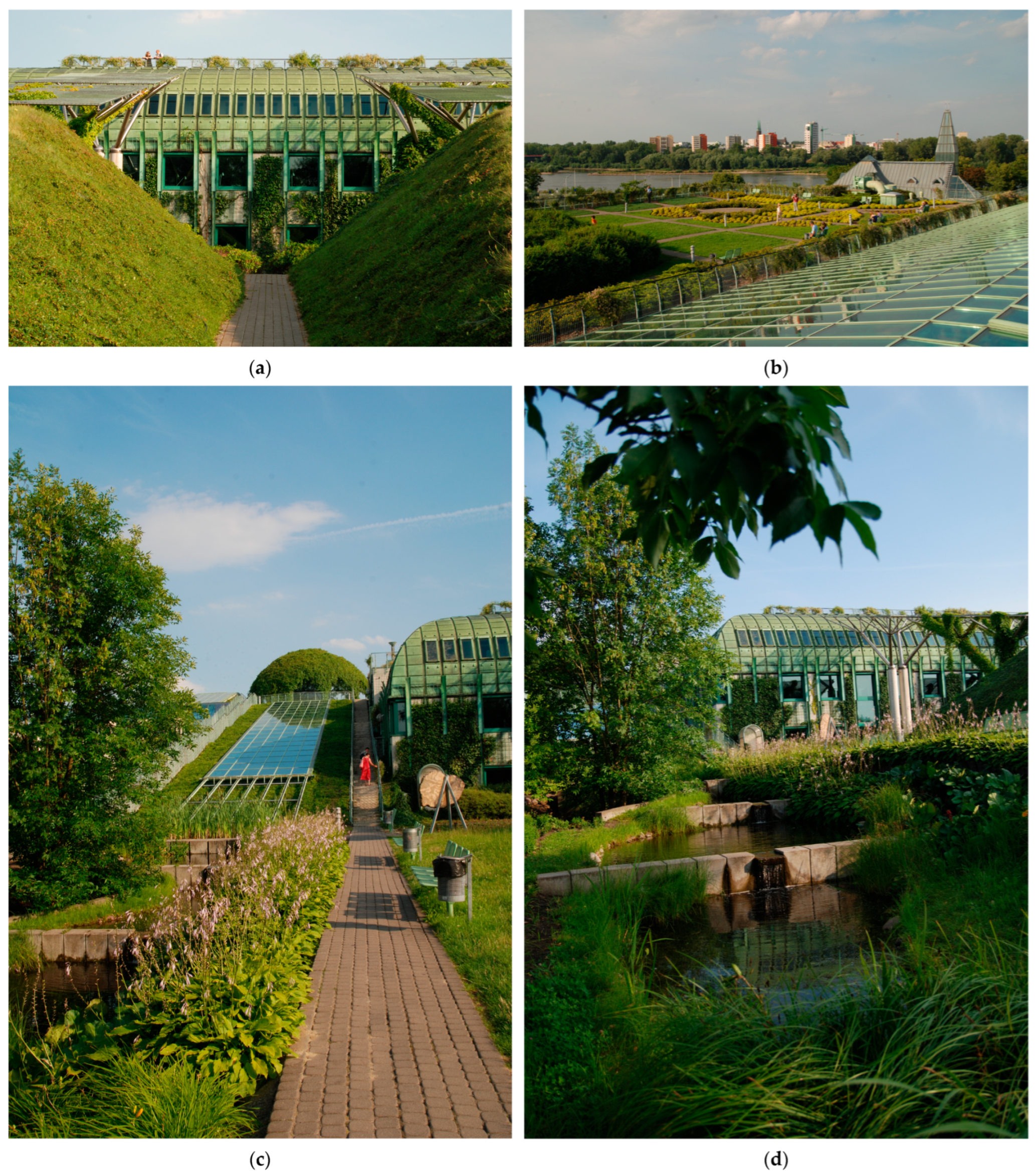

Figure 1).

4.1.2. Physical Elements

The complex comprises 64,000 m2 of usable space and 17,000 m2 of garden area, including a lower garden and a green roof. The lower part consists of an enclosed park with a pond, a fountain, and sculptures by Ryszard Stryjeński (from the Situational sketches series, referencing cosmological motifs). Access to the roof is provided via stairs and a ramp planted with vegetation. The roof garden is divided into four colour-coded zones—gold, silver, crimson, and blue—whose composition is based on a diversity of plant species. The materials employed—glass, steel, copper with a patina, and greenery—create a hybrid of nature and technology. Plant elements are also integrated into the façade and interior. Arboricultural structures are incorporated within the building. The complex is embedded in the topography of the Warsaw Escarpment, and its form is organically integrated with the surrounding environment.

4.1.3. Aesthetic–Spatial Aspects

The spatial composition is based on the relationship between nature and geometry. The lower part of the complex has a naturalistic character, whereas the upper garden introduces axial and symmetrical arrangements. Each garden area is distinguished by its colour scheme, yet the transitions between them are seamless. The use of patinated copper and vegetation creates the effect of the architecture “dissolving” into the landscape—the building appears as an integral part of nature.

4.1.4. Aesthetic–Sensory Experiences

The University of Warsaw Library garden conveys a sense of vastness and openness while also allowing for a feeling of seclusion through smaller, intimate garden spaces. Panoramic views of Warsaw introduce an element of the surreal. Aesthetic experiences arise from the combination of the urban panorama with lush greenery, unexpected perspectives, and the interplay of light reflecting off copper and glass surfaces.

4.1.5. Sensory Aspects

The spatial experience engages vision (the diversity of colours and plant forms), touch (textures of metal, glass, and stone), hearing (the rustle of the wind, city sounds, the splash of fountains, bird calls), and smell (plant aromas). On the roof, wind and changing atmospheric conditions are particularly noticeable. Direct contact with nature intensifies the sensory experience.

4.1.6. Spatial Elements

The spatial composition is structured around a sequential journey through the garden—from intimate garden interiors to panoramic viewpoints. This layout enhances the dynamism of movement and conveys a narrative dimension to the experience. Variation in levels, directions, and vantage points (e.g., towards the Vistula River, the Old Town, and the city centre with skyscrapers) creates an immersive perspective, drawing the user into the landscape. Boundaries are flexible, and the architecture forms interpenetrating garden interiors.

4.1.7. Aesthetic–Atmospheric Aspects

The prevailing atmosphere is one of calm, contemplation, and respite. Greenery, natural materials, and the interplay of light create a climate of organic harmony. The impression of “immersion in greenery” fosters a sense of unity with the place. The garden functions as a space for relaxation and emotional restoration.

4.1.8. Psychological–Phenomenological Aspects (Atmospheric Aesthetics)

Being in the garden generally evokes feelings of tranquillity, freedom, and security. Simultaneously, certain elements—such as steel grilles or exposure to wind—generate ambivalent emotions, balancing comfort with subtle unease. The experience of the place encourages self-reflection and bodily awareness, aligning with the phenomenological concept of lived space.

4.1.9. Behavioural Aspects (Non-Emotional Experiences)

Users engage with the garden for walking, socialising, relaxation, and as a backdrop for events or photographic sessions. Both communal behaviours (e.g., groups gathering in the Golden Garden) and individual activities (reading, contemplation) are observed. The garden influences social interaction, promoting engagement and integration. The space also stimulates exploratory behaviours, encouraging movement and discovery of different garden areas.

4.1.10. Technological Elements

Infrastructure elements—such as skylights, ventilation systems, and steel walkways—are integrated within the planting scheme, serving both technical and aesthetic purposes. This creates a symbiosis of technology and nature, characteristic of contemporary ecological architecture.

4.1.11. Narrative Coherence and Contextual Framework

The architects’ narrative is founded on a dialogue between nature and culture—the green façades and roof garden coexist with the library’s scholarly function. The façade, featuring eight panels of text in various languages, forms a “cultural skin,” symbolising knowledge and diversity. In the urban context, the Library acts as a landmark, connecting the Warsaw Escarpment with the city panorama (

Kania 2024). The project realises the concept of biophilic immersion: architecture not only represents nature but enables its tangible experience. The site functions as an enclave, providing detachment from urban reality. It is not limited to fulfilling the library programme but is open to personal narratives and experiences.

The University of Warsaw Library exemplifies immersive integration of architecture and nature, where users experience a seamless transition between urban space and organic landscape. Immersion in this multisensory environment—combining greenery, light, sound, and material texture—promotes contemplation, relaxation, and a sense of harmony with the surroundings.

4.2. Musée du Quai Branly—Jacques Chirac: Museum of Non-European Art in Paris (2004)

4.2.1. Main Assumptions

The Musée du quai Branly—Jacques Chirac was initiated by President Jacques Chirac to honour the heritage of non-European cultures and to create a space for dialogue between civilisations. The building was designed by Jean Nouvel, the landscape garden by Gilles Clément, and the vertical garden by Patrick Blanc. The museum opened to the public in 2006. Its concept envisioned the integration of nature, technology, and culture within an immersive environment that encourages reflection on the diversity of the world. The immersive character of the site is closely linked to its function. The narrative is constructed through a prelude to what is “hidden” within the building—introducing visitors to a state of immersion. Vegetation facilitates direct engagement with nature, and the layout provides numerous spaces and corners for rest and for “touching” the natural environment (

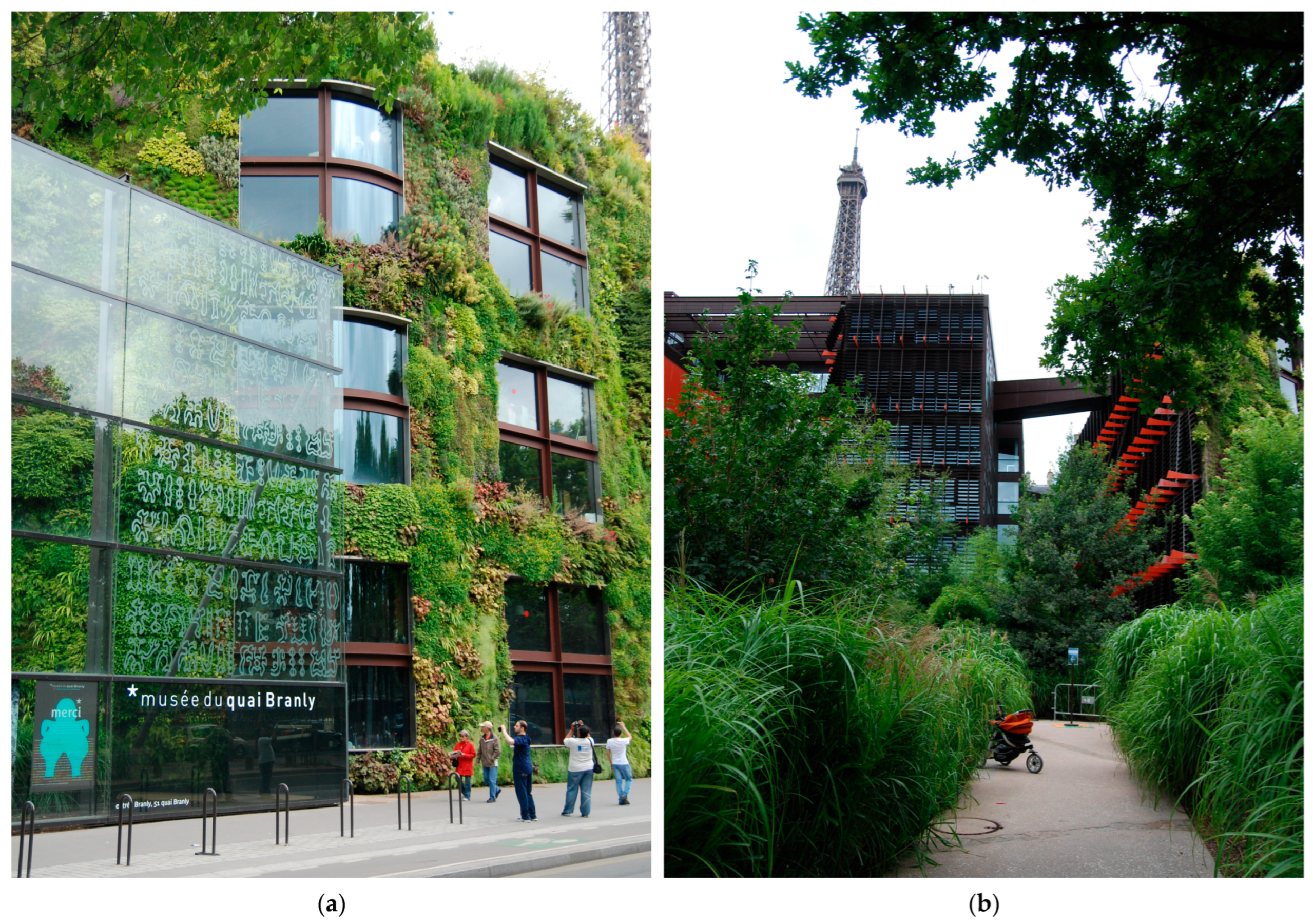

Figure 2).

4.2.2. Physical Elements

The complex occupies an area of 18,000 m2. The dominant element is an elongated building elevated on stilts, beneath which extends an extensive garden with pathways, hills, and slopes. The garden contains 169 trees and over 30 plant species, including bamboos and grasses. To the north, the site is bordered by a 17-m glass acoustic wall, and to the south by a pond forming a soft spatial boundary. Both sides provide access to the museum. The ensemble integrates architecture and landscape across interpenetrating levels.

4.2.3. Aesthetic–Spatial Aspects

The architectural-landscape composition is based on the contrast between the organic form of the garden and the linear, geometric structure of the building. Despite its mass, the architecture blends with the greenery through curved forms and a façade colour palette inspired by non-European art. The building has been described as “hybrid, complex, colourful, mysterious, and joyful” (

Edelmann 2006). The vertical garden, serving as a living façade, manifests the fusion of nature and technology, creating a visually dynamic, almost sculptural structure.

4.2.4. Aesthetic-Sensory Experiences

The spatial experience varies—from distance (from the streets Quai Jacques Chirac and Rue de l’Université) to immersion within the greenery. Entering the museum requires passing through the garden, which serves as a prelude to immersion in world cultures. The green wall acts as a visual and architectural introduction, preparing visitors for the museum’s exhibits. The interplay of scale, light, and colour generates tension between the monumentality of the architecture and the intimacy of plant-filled interiors.

4.2.5. Sensory Aspects

The garden engages multiple senses: the rustle of grasses and bamboo, the cool moisture around the pond, and subtle differences in surface textures. The interior is quieter than the surrounding city due to glass screens. Plant aromas, changing light, and microclimate reinforce the feeling of “detachment from Paris.” The garden is a habitat for birds. Direct sensory contact with nature emphasises the biophilic dimension of the architecture.

4.2.6. Spatial Elements

The garden layout is fluid and sequential. Narrow paths, hills, bridges, and ramps guide users through diverse microspaces organised in organic patterns reminiscent of exotic landscapes—from dense thickets to open glades. Movement in the garden is exploratory, and the changing topography with restricted sightlines introduces an element of mystery. Paths sometimes include slopes or stairs to negotiate the uneven terrain, which features hills and depressions. These elements arose during construction for technical reasons, such as a concealed caisson protecting the collections from flooding. Some dome-like, crusted hills evoke associations with turtles. The building appears to “float” above the site, remaining integrated with the landscape. In 2015, the garden programme was supplemented with an architectural pavilion by Jean Nouvel.

4.2.7. Aesthetic–Atmospheric Aspects

The atmosphere of the garden and complex is exotic, contemplative, and slightly mysterious. Light filtered through vegetation and reflected in glass and water creates a play of moods—from bright intensity to semi-darkness. Colours and materials reinforce the expression of an “other world”—a space between nature and culture. The garden is not merely an aesthetic backdrop but a key element shaping the overall museum atmosphere.

4.2.8. Psychological–Phenomenological Aspects (Atmospheric Aesthetics)

Being in the museum grounds evokes feelings of calm, curiosity, and occasionally disorientation. Changes in scale, silence, scents, and the softness of vegetation induce a state of perceptual immersion. Following Böhme’s concept of atmospheres, this experience is one of “suspension”—the visitor does not merely observe the space but participates in it bodily and emotionally.

4.2.9. Behavioural Aspects (Non-Emotional Experiences)

The garden functions as a transitional and buffer space, preparing visitors for the exhibition. Users primarily move in the context of the museum visit, but the garden also encourages brief stops and rest. Exploratory behaviours are common, including walking, observing nature, and photography. Narrow paths and organic forms promote a slow pace of movement and heightened attentiveness.

4.2.10. Technological Elements

The project exemplifies advanced integration of technology and nature. Patrick Blanc’s green wall employs a hydroponic system without soil, allowing vertical cultivation of plants. Glass screens serve acoustic and informational functions. The elevated building base conceals a caisson protecting the collections from Seine flooding. Technology contributes not only to functionality but also to the spatial narrative and the site’s sustainable character.

4.2.11. Narrative Coherence and Contextual Framework

The architectural narrative integrates nature, culture, and technology, creating a coherent story of humanity’s relationship with the planet. The garden serves as a prelude to the exhibition, preparing the visitor’s senses and emotions. Landscape architect Gilles Clément drew on similarities with savannah forest landscapes, continuing his “garden in motion” (Le jardin en mouvement) concept—spaces subject to continuous change through natural phenomena (

Flouquet 2006). Clément’s design references his earlier Planetary Garden concept in Parc de la Villette, Paris, highlighting both the diversity of nature and of human cultures, shaped by geographical isolation. He aimed to combine animistic respect for natural beings in traditional societies with contemporary ecological concern. Hence, symbols and material elements reference objects treated in various ways: as sacred, ritual ornaments, or even as forms of currency (

Edelmann 2006).

The museum is located in central Paris, near the Seine and the Eiffel Tower, creating a contrast to the surrounding classical architecture—a natural island within the urban fabric. Its function and form engage with global ecological and postcolonial discourse, emphasising the need to understand and respect “Other” cultures. Urbanistically, it exemplifies a contemporary dialogue between nature and the city, and between tradition and modernity.

The Musée du quai Branly—Jacques Chirac was conceived as an immersive space where visitors gradually engage with visual, auditory, and haptic experiences, transitioning from the city to an organic world of nature and non-European cultures. The integration of architecture, garden, and technology creates a coherent, multisensory narrative, drawing the visitor into full participation rather than passive observation.

4.3. Bosco Verticale Residential Towers in Milan (2014)

4.3.1. Main Assumptions

Bosco Verticale (“Vertical Forest”) is a biophilic architectural project created by Stefano Boeri Architetti, completed in 2014 in Milan. The two residential towers—Torre De Castillia (111 m) and Torre Confalonieri (80 m)—represent a manifesto of a new approach to integrating nature with high-density urban structures. The principal concept was to create a self-sustaining urban ecosystem in which the relationship between humans, vegetation, and the city is reciprocal and balanced (

Figure 3).

Immersiveness in Bosco Verticale is achieved through the blurring of boundaries between architecture and nature, allowing users to experience space not only visually but also multisensorially and emotionally. Residents are literally surrounded by greenery—trees and shrubs that co-create a microclimate and an atmosphere of tranquillity. The contact with vegetation, its seasonal variability, the play of light filtered through leaves, and the sounds of birds collectively build a phenomenological sense of coexistence with nature. For the external observer, the towers serve as a manifesto of biophilic narrative—a symbolic image of harmony between humanity and the natural world, in which architecture becomes a living ecosystem.

4.3.2. Physical Elements

The towers are located in the Porta Nuova district, directly adjacent to the Biblioteca degli Alberi Milano (BAM) park. Rising above the dense mid-rise urban fabric (approx. 5–6 storeys), the two towers form a distinctive spatial landmark. The structural system is reinforced concrete, designed to support the weight of extensive vegetation-bearing balconies—comprising approximately 800 trees, 5000 shrubs, and 15,000 herbaceous plants. This required the application of innovative engineering solutions and technologies for maintaining plant life at great heights.

4.3.3. Aesthetic–Spatial Aspects

Bosco Verticale embodies the concept of a vertical landscape, introducing a new typology of urban silhouette. The simple, modernist forms are animated by irregularly arranged terraces and balconies planted with vegetation, which generate a dynamic, organic texture contrasting with the smooth glass-and-concrete façades of the surrounding city. The greenery softens the geometric rigidity of the architecture, introducing rhythm, softness, and visual variability. The result is a spatial composition that acts immersively—through visual immersion in greenery and an emotional sense of harmony between the order of nature and architectural structure.

4.3.4. Aesthetic-Sensory Experiences

From the perspective of an external observer, the experience is primarily visual. The changing seasons bring noticeable variation—colours and textures of the plants form a living spatial composition, with light, shadow, and greenery in constant dialogue. Up close, the viewer perceives a tactile and visual contrast between the rawness of concrete and the softness and vibrancy of vegetation. Reflections in the glazed surfaces produce a sense of illusion—a double presence of nature, both real and mirrored.

4.3.5. Sensory Aspects

The sensory impact is predominantly visual. At ground level, the sounds of nature are largely masked by urban noise. However, for residents on higher floors, alternative sensory qualities emerge—the rustling of leaves, the shifting of light and wind, and the scents of plants. The project thus establishes two distinct perceptual domains: an external, visual-symbolic sphere and an internal, multisensory one.

4.3.6. Spatial Elements

The configuration of the balconies and the positioning of the towers within the surrounding landscape generate complex relationships between private and public space. From the adjacent park, the towers form a monumental backdrop to the open urban landscape. From within the apartments, vegetation functions as a visual filter, limiting perspective and creating an experience of “immersion in greenery.”

4.3.7. Aesthetic–Atmospheric Aspects

Bosco Verticale creates an atmosphere of simultaneous engagement with nature and the city. The vegetated façades soften the towers’ monumental presence, imparting an organic character. For residents, the greenery provides a private microclimate, serenity, and natural light; for the external observer, it becomes a symbol of ecological renewal and hope for the contemporary metropolis.

4.3.8. Psychological–Phenomenological Aspects (Atmospheric Aesthetics)

The experience of Bosco Verticale rests on a duality of contemplation and control. For residents, it represents an everyday engagement with nature—observation, care, and empathy towards plants. For outside viewers, it functions primarily as an icon of biophilia—a signifier of the idea rather than a direct immersion experience. Phenomenologically, Bosco Verticale evokes admiration, but also a sense of distance—it is, metaphorically, a “forest in site.”

4.3.9. Behavioural Aspects (Non-Emotional Experiences)

User behaviour reflects a model of coexistence between humans and nature in urban conditions. Residents adapt to the rhythm of natural cycles, observing seasonal changes, light, and weather. For pedestrians, the towers act as a landmark and visual destination for walks. In social terms, they reinforce a sense of place identity and belonging to a “green Milan.”

4.3.10. Technological Elements and Narrative Coherence

The project employs integrated technologies that sustain plant life—automated irrigation systems, humidity sensors, and structural solutions counteracting wind loads. Boeri’s architectural narrative—“a home for trees that also houses people and birds” (

ANSA English Desk 2025)—is coherently realised: technology serves the idea of biophilia rather than suppressing it.

4.3.11. Contextual Framework

Bosco Verticale forms part of the broader Porta Nuova redevelopment programme, symbolising Milan’s transformation towards a sustainable city. On a global scale, it stands as an icon of pro-ecological architecture and a benchmark for subsequent biophilic projects. It aligns with contemporary urban discourse on the necessity of coexistence between infrastructure and nature.

Bosco Verticale exemplifies immersive architecture, in which the human being becomes literally enveloped by nature, experiencing harmony between the vegetal world and the urban structure. Immersion in greenery, the variability of light, and the rhythm of natural cycles elevate the experience of dwelling into a multisensory coexistence where the boundary between architecture and ecosystem becomes blurred.

4.4. Crossrail Place Roof Garden—Canary Wharf in London (2015)

4.4.1. Main Assumptions

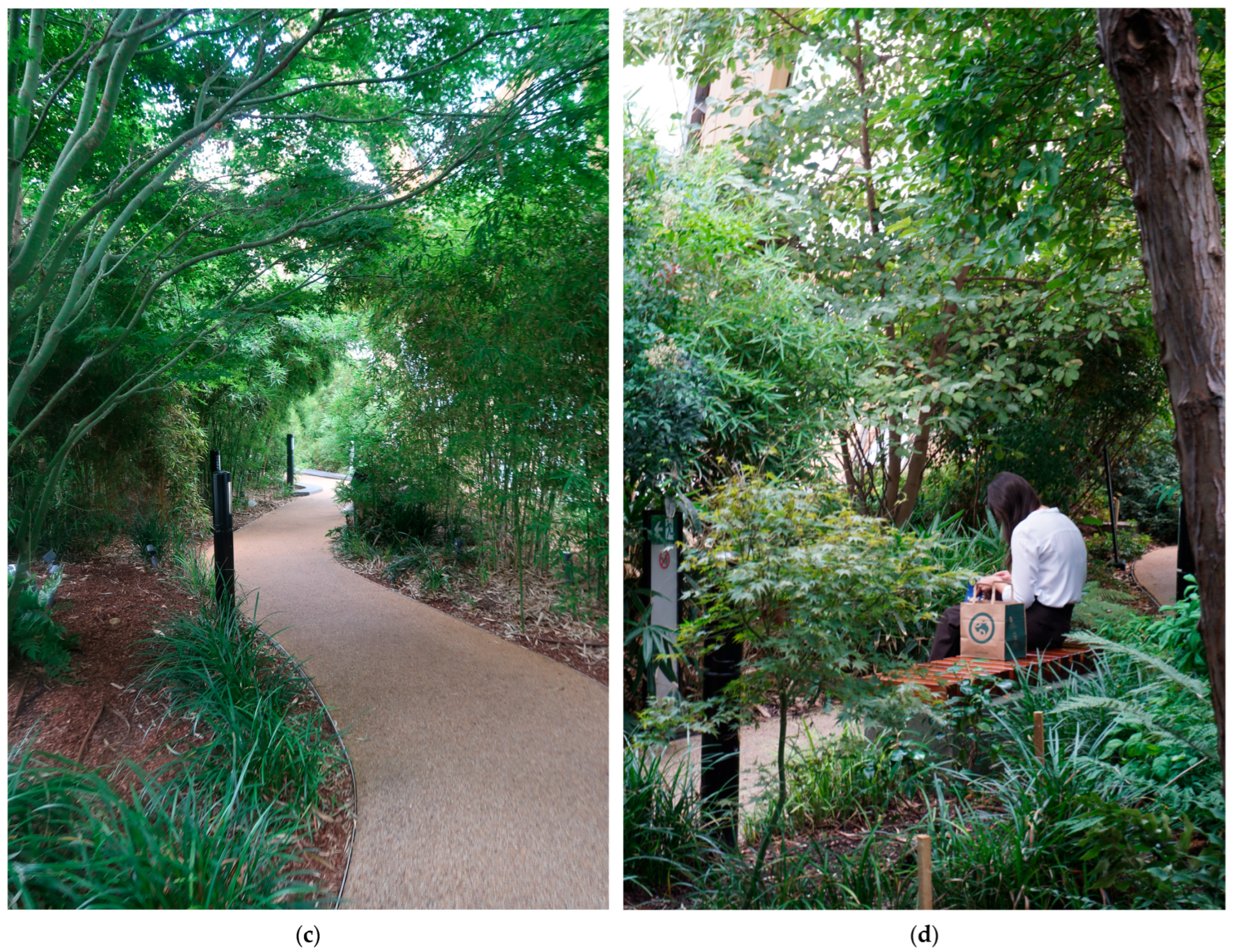

Crossrail Place Roof Garden represents an innovative synthesis of transport infrastructure, commercial facilities, and a public garden within a single, multi-layered architectural structure. The project’s objective was to create a space for relaxation and contact with nature in the densely built business district of Canary Wharf, while simultaneously evoking the maritime heritage of the area. Designed by Foster + Partners, in collaboration with ARUP and Gillespies in 2015, the project serves as an example of biophilic architecture in an urban context—integrating functional and symbolic dimensions (

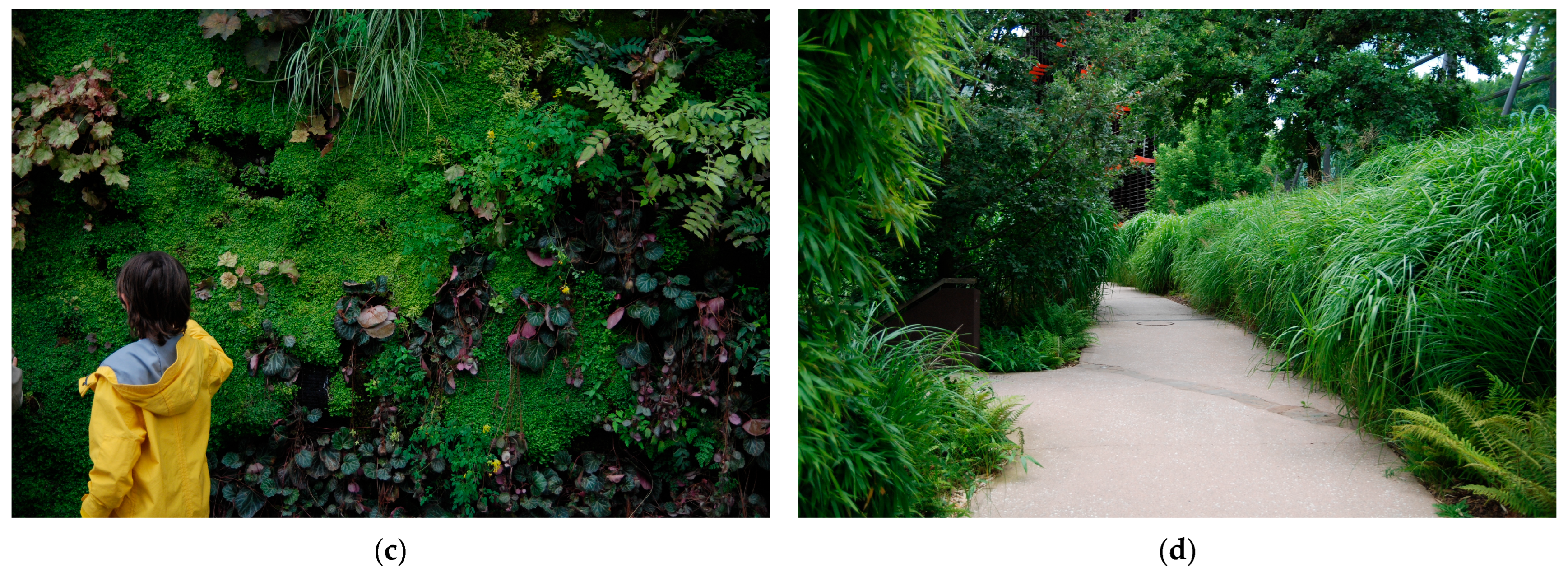

Figure 4).

Immersiveness in Crossrail Place Roof Garden manifests itself through the experience of being enveloped in a semi-transparent, plant-filled structure that separates the visitor from the city’s noise, creating the impression of being inside an exotic garden beneath a glass canopy. The space acts multisensorially—through light, sound, and touch—leading to a sense of calm, contemplation, and momentary transport into a different, natural world at the heart of the city.

4.4.2. Physical Elements

The building covers a total area of 53,500 m2, of which approximately 4160 m2 is occupied by the roof garden located above the Crossrail station. The entire structure, over 300 m in length, resembles a ship moored in dock—an explicit reference to the site’s maritime history. The roof consists of a timber lattice structure covered with transparent ETFE cushions, which admit daylight while providing partial protection from rain. These technological solutions create a controlled microclimate that supports the growth of exotic plant species and reduces external noise.

4.4.3. Aesthetic–Spatial Aspects

The garden’s composition is organised around two thematic zones—Eastern and Western—symbolically referring to Britain’s historical trade routes, reflected in the botanical selection of plant species (

Canary Wharf Group n.d.a). The pathways follow a free, organic layout dominated by a softly winding circulation axis. Variations in vegetation and topography generate a dynamic spatial rhythm that contrasts with the geometric order of the timber canopy. The juxtaposition of natural forms with the architectural framework produces a composition of high aesthetic value, based on a dialogue between nature and technology.

4.4.4. Aesthetic-Sensory Experiences

Entry into the garden marks a transition from the noisy, office-dominated surroundings into a more intimate space defined by greenery. Light filtering through the ETFE roof produces variable patterns of shadows and reflections, reinforcing the sense of immersion. As visitors move along the paths, they experience shifting scents, colours, and densities of planting, intensifying spatial perception.

4.4.5. Sensory Aspects

The garden engages multiple senses: sight through the diversity of colours and foliage shapes, touch through the proximity of plants that can be physically encountered, and hearing through the subdued hum of the city combined with the gentle rustling of leaves. The microclimate enhances the perception of pleasant humidity and moderate temperature, strengthening the sensation of being in an exotic, enclosed garden. The space allows for a temporary disconnection from the urban environment.

4.4.6. Spatial Elements

The garden is designed as a sequence of immersive spatial episodes—transitions, alcoves, and pockets—that draw visitors into the rhythm of a natural landscape. Variations in plant height and density create semi-private zones conducive to contemplation and rest. The spatial layout retains directionality while also offering opportunities to pause, linger, and experience the space individually.

4.4.7. Aesthetic–Atmospheric Aspects

The garden’s atmosphere is gentle, sensuous, and reflective. Light filtered through the roof and foliage creates a translucent aura, within which the visitor experiences tranquillity and balance. The interior evokes the ambience of a greenhouse or tropical conservatory, heightening the impression of isolation from the outer world and encouraging introspection.

4.4.8. Psychological–Phenomenological Aspects (Atmospheric Aesthetics)

Visitors experience a sense of immersion and calm, accompanied by a mild spatial disorientation characteristic of immersive environments. The impression of being in an “other world” arises from the juxtaposition of everyday urban infrastructure with an intensely organic garden environment. This generates a phenomenological condition of in-betweenness—a state suspended between nature and technology, reality and creation.

4.4.9. Behavioural Aspects (Non-Emotional Experiences)

The space encourages both individual and social forms of activity—walking, conversation, and rest. Its intimate scale, mild microclimate, and spatial diversity allow it to function as a “breathing space” within the urban fabric. Users’ behaviours are predominantly non-expressive and contemplative, marked by slowness, calmness, and rhythmic engagement with the environment.

4.4.10. Technological Elements and Narrative Coherence

The ETFE and cross-laminated timber roof structure serves not only a protective but also a symbolic function, evoking the image of a ship and the maritime heritage of Canary Wharf. The spatial narrative is built upon the idea of global botanical exchange, recalling colonial voyages and the exploration of nature—“a celebration of Canary Wharf’s maritime heritage and the global exploration of plants” (

Landscape Institute 2015;

Gillespies n.d.). The garden was conceived from the outset as a “sheltered plant environment” (

Landscape Institute 2015). Technology here operates coherently with the design concept—it functions as a medium for producing an immersive experience rather than merely a utilitarian device.

4.4.11. Contextual Framework

Crossrail Place Roof Garden was established in the business heart of London as a counterbalance to the monofunctional office landscape of Canary Wharf. It constitutes a biophilic enhancement of the urban environment, reconnecting the area’s port-related past with a contemporary, sustainable design ethos. The project aligns with a broader trend of humanising infrastructural spaces through the introduction of nature and sensory experience into the urban realm.

Crossrail Place Roof Garden creates an immersive environment in which the user becomes enveloped by vegetation, cut off from the urban bustle, and immersed in a tropical atmosphere at the core of Canary Wharf. Multisensory stimuli—light, sound, touch, and microclimate—evoke a sense of calm, contemplation, and temporary displacement into “another world”, merging nature and technology into a coherent spatial narrative.

4.5. Eden Dock—Canary Wharf in London (2024)

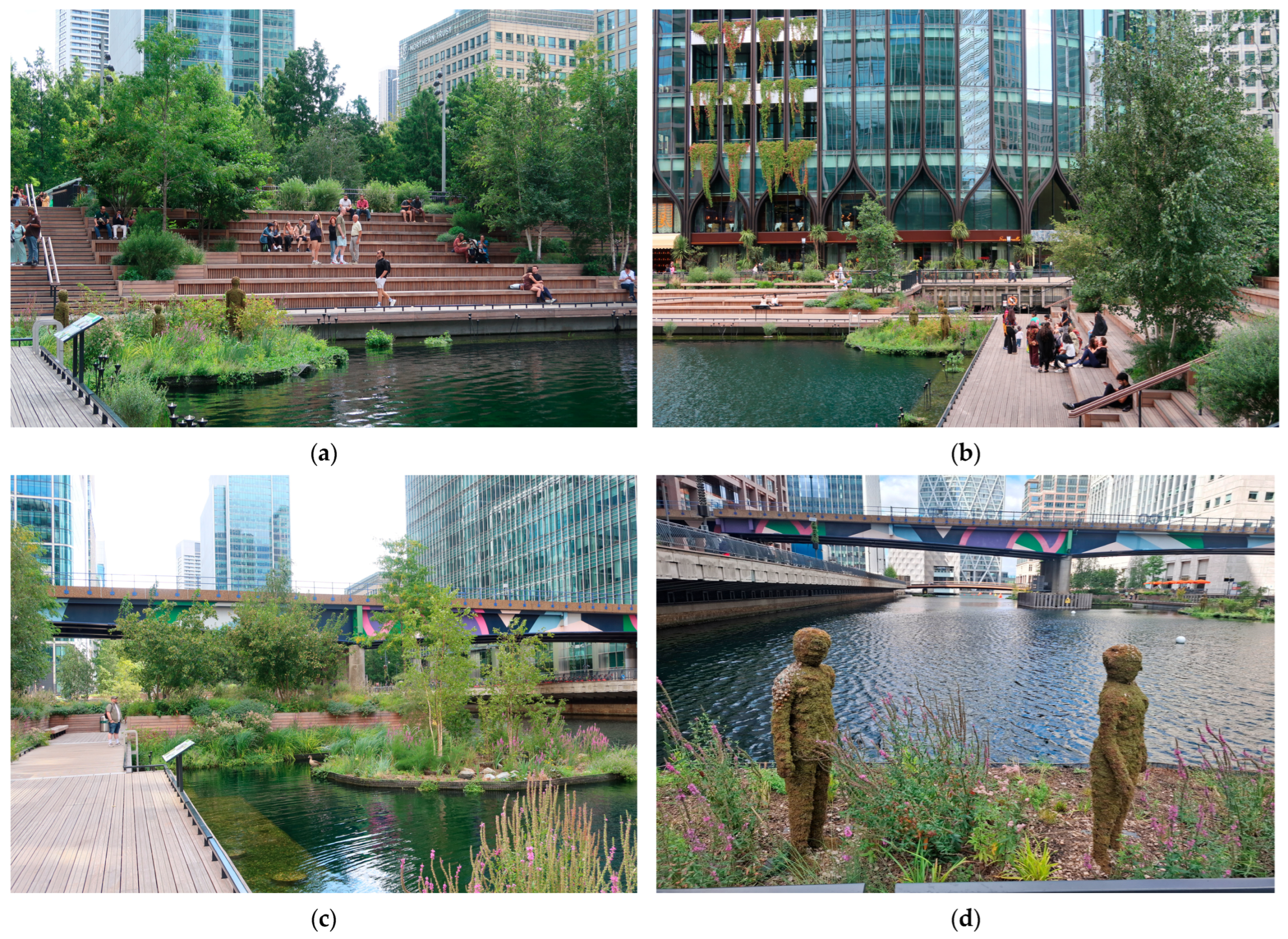

4.5.1. Main Assumptions

Eden Dock represents the transformation of the historic Middle Dock (Grade I listed) in Canary Wharf, London, into a verdant urban landscape within a high-density built environment. The project’s primary aim was to introduce new ecological, artistic, cultural, and recreational functions into the urban fabric. The space was opened to the public in October 2024. The concept of Eden Dock was developed by Glenn Howells Architects (Howells) as lead planner and principal designer, with landscape architecture by HTA Design (

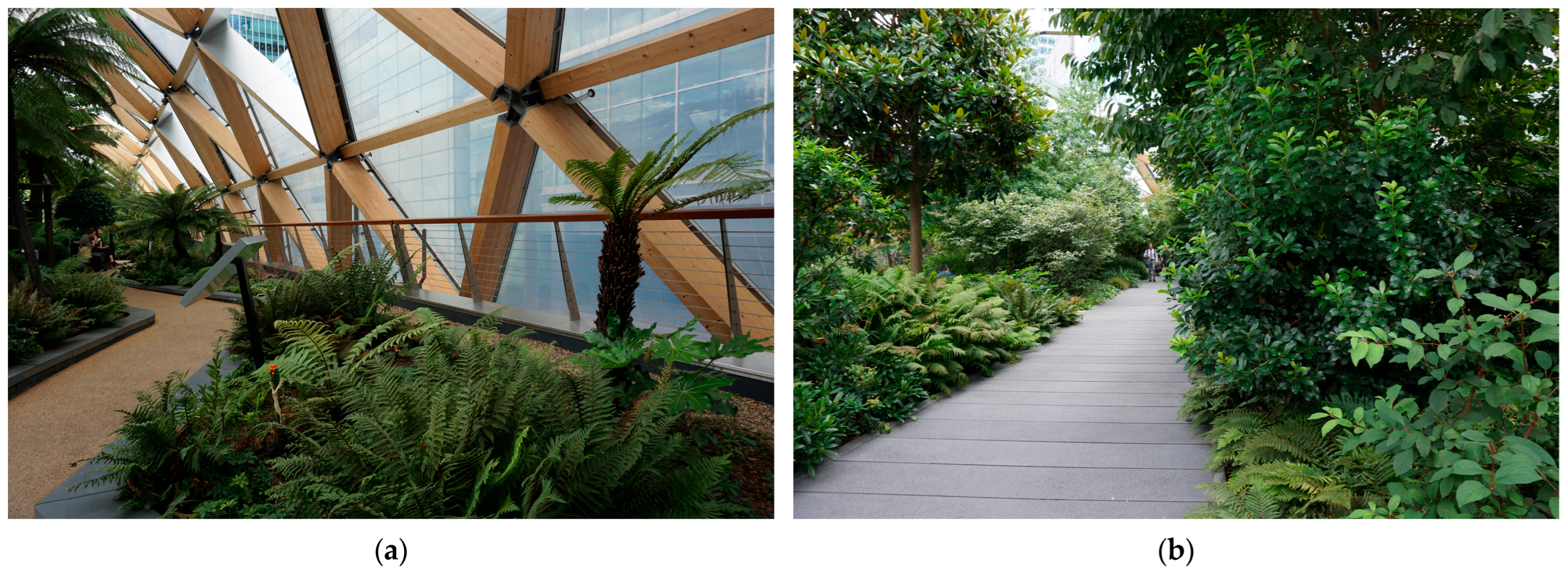

Figure 5).

The immersive quality of Eden Dock lies in the user’s physical and sensory immersion within lush, varied vegetation and direct contact with water, enabling an immediate experience of nature within the urban context. The space allows for a temporary withdrawal from the city’s noise, engaging the senses—sight, sound, and touch—to evoke a feeling of presence and symbiosis with the surroundings.

4.5.2. Physical Elements

The project reconfigured the concrete quays of the historic dock, creating public green terraces, platforms, and floating islands, along with new infrastructure that improves pedestrian connectivity—such as a footbridge and facilities for water-based recreation. The newly designed forms imitate natural structures, while the terraces serve as a contemporary architectural frame for the waterfront. Approximately 30% of the dock’s area has been redeveloped into accessible green zones.

Eden Dock connects to other public green areas—Jubilee Park to the east, India Avenue and Cabot Square to the north—yet retains the character of an urban enclave, distinct from its corporate context.

4.5.3. Aesthetic–Spatial Aspects

The terraces, micro-landscapes, and floating islands mimic natural formations, contrasting with the orthogonal urban grid of Canary Wharf. The rigid waterfront lines have been softened, while vegetation introduces rhythm and visual diversity that integrates the site with its surroundings. The spatial composition allows for both visual connection with the wider context and intimate retreat within secluded pockets of the dock.

4.5.4. Aesthetic-Sensory Experiences

The space acts immersively: users are enveloped by greenery, experience proximity to water and vegetation, and encounter multiple viewpoints overlooking the dock and surrounding towers. The dynamic design and constant change in the landscape stimulate exploration and discovery.

4.5.5. Sensory Aspects

The multisensory experience includes visual contact with rich vegetation, tactile engagement with plants and water, and auditory stimuli such as the rustling of leaves and the presence of birds. The microclimate—partially sheltered from wind and rain—enhances sensory comfort. The intensity of sensory stimuli changes with weather and seasons, amplifying the immersive effect.

4.5.6. Spatial Elements

Eden Dock offers a varied topography with observation points and areas for recreation. Pathways guide visitors through distinct zones, supporting both active movement and stillness. Vegetation and educational installations subtly define spatial boundaries and flow, directing users while maintaining a sense of openness.

4.5.7. Aesthetic–Atmospheric Aspects

The atmosphere is intimate, contemplative, and restorative. Its mood shifts with weather conditions, deepening the user’s connection with natural processes—rain accentuates the presence of water, while sunlight encourages social use and relaxation. Topiary installations (Nature Rising by Agrumi Topiary Art, Sister London) and curated planting schemes introduce artistic and performative elements, visually enriching the terrain.

4.5.8. Psychological–Phenomenological Aspects (Atmospheric Aesthetics)

The space evokes curiosity and exploratory engagement, encouraging spontaneous encounters—observing wildlife, perceiving seasonal change, or discovering hidden perspectives. Its detachment from the urban environment fosters introspection, calmness, and a sense of reconnection with nature.

4.5.9. Behavioural Aspects (Non-Emotional Experiences)

Users engage in a variety of activities: relaxation, nature observation, water sports, educational exploration, or artistic and literary practices such as photo sessions or creative writing. The design accommodates both individual contemplation and social interaction, enabling open-ended, user-generated experiences.

4.5.10. Technological Elements

Eden Dock employs innovative structural and landscape technologies in its terraces, platforms, and floating islands, integrating water into the overall design. Educational signage and supporting infrastructure facilitate orientation and encourage interaction with the natural environment.

4.5.11. Narrative Coherence and Contextual Framework

The project embodies an authorial narrative of a “waterside oasis in the heart of Canary Wharf,” merging nature, education, and recreation. Its declared aims—well-being, biodiversity, and coexistence with the urban ecosystem—are consistent with broader sustainability strategies promoted by

Canary Wharf Group (

n.d.b) through slogans such as “a place for nature and people” and “relax by the water and let nature improve your wellbeing.”

Other interpretations (

ARUP n.d.;

New London Architecture [NLA] 2025) frame the project within the agendas of dockland reactivation, enhanced water experience, 15 min city principles, urban greening, and innovation in ecological infrastructure, positioning Eden Dock within the movement of urban re-naturing.

The site allows for personal and unanticipated experiences, including artistic or performative appropriations that extend beyond the designer’s intent—thus maintaining a flexible, open-ended relationship between users and space.

Eden Dock in London creates an immersive urban landscape where users are enveloped by lush vegetation and water, experiencing nature multisensorially within the dense urban fabric. The project encourages calmness, introspection, and exploration, uniting relaxation, education, and interaction in a harmonious “waterside oasis” at the heart of Canary Wharf.

5. Findings

The examples presented in

Section 4 confirm that immersion in biophilic architecture refers to a space’s capacity to draw the user into an experience of full engagement—both physical and emotional. A key aspect of this phenomenon is the possibility of entering and moving through space in such a way that the user becomes its integral part. Immersion does not rely on observation from a distance, but on being surrounded by an environment in which architecture and nature coexist. In this sense, space engages the body through movement, changing perspective and the relationship of scale, offering the experience of ‘entering another world’.

Immersion is closely linked to multisensory perception. Biophilic architecture stimulates sight, hearing, touch and smell—through the sounds of nature, the scent of plants, variable light and the microclimate. Such an environment supports not only visual perception, but also builds a complete sensorial and emotional experience. The user perceives the presence of nature not as decoration, but as a real, living element of the space.

Another dimension of immersion lies in the aesthetic and atmospheric character of the place, which shapes its mood and emotional microcosm. Light, material textures, spatial rhythm and greenery create an aura of calm, contemplation or mystery. In this way, architecture evokes affective responses—awe, tranquillity or a sense of harmony with the surroundings. The visitor reacts spontaneously, pausing, touching, observing—experiencing the space in its entirety.

Immersion is also reinforced by a coherent narrative and contextual framework. A space that tells a story—about the relationship between humans and nature, about culture or heritage—allows for a deeper engagement with its meaning. Architecture, landscape and technology together form a unified narrative, one that the observer enters through all the senses. As a result, immersion becomes not only an aesthetic impression, but also a psychological and phenomenological experience, in which the individual coexists with nature, sensing its presence in an authentic and holistic way.

Through the analysis of five case studies, features of shared, similar and specific character have been identified.

The common features of immersion in the analysed projects arise from the synergy between nature and architecture and from the pursuit of a multisensory, emotional engagement of the user within the space. All examples create environments conducive to contemplation, introspection and contact with nature, despite differences in function and urban context. Immersion is achieved through the play of light, the diversity of materials, spatial rhythm and the integration of natural elements—vegetation, water, sounds and microclimate.

Similarities can be seen in the idea of ‘detachment from the city’—the BUW Library and Crossrail Place offer contemplative enclaves within dense urban fabric; the Musée du quai Branly and Eden Dock construct narratives of transition between the worlds of culture and nature; while Bosco Verticale translates this experience into a private, vertical dimension. In all cases, immersion acquires both a biophilic and phenomenological character—the observer does not merely look at nature, but participates in it through sensory and emotional involvement.

Differences primarily concern the scale and character of immersion: in BUW Garden and Crossrail Place, immersion is spatial and social (a shared, open experience); in the Musée du quai Branly, it is narrative and symbolic (immersion in cultures and nature); in Bosco Verticale, it becomes private and quotidian (the inhabitant’s daily immersion in nature); while in Eden Dock, it takes a multisensory and performative form (contact with water, vegetation and movement). The degree of ‘control’ over nature also varies—from the naturalistic, slightly wild landscapes of Eden Dock or the Branly Garden to the technologically regulated greenery of Bosco Verticale and Crossrail Place.

6. Discussion

Research suggests that twenty-first-century biophilic architecture is not merely a design approach, but a new cultural paradigm. It integrates technology and nature, function and symbolism, materiality and experience. Its potential extends beyond environmental aspects, creating new frameworks for understanding space as a site where humans encounter nature, art, culture, and themselves. Immersion emerges as a key concept in understanding this process: it serves as a tool enabling architecture to reclaim its original purpose—as a living environment, rather than merely a backdrop. The diverse ways in which biophilia is applied reveal one of the key challenges in defining the concept of nature and its significance for architecture.

Patel et al. (

2022) point out that excessive focus on nature itself may, paradoxically, prevent a genuine sense of connection with it. Moreover, they emphasise the importance of cultural context, which shapes how nature is interpreted and how immersion is experienced. The present study was limited to European sites; however, the users of these public spaces and buildings come from across the world.

A limitation of existing research is the lack of standardisation regarding the catalogues or sets of biophilic elements (

Kellert 2008) and spatial typologies. The study determined that places have greater potential than “viewed” biophilic objects. This research direction could be further expanded to include new spatial categories. Similarly, the assessment of biophilia itself remains underdeveloped; while several sets of biophilic elements exist, not all can elicit a sense of immersion. In our research, we focused specifically on “greened” environments. Research confirms that, although biophilic architecture is often strongly emphasised in terms of its visual engagement with nature (such as greenery or window views), parameters such as experience, narrative, symbolism, and sense of place have been considerably less explored (

Tekin et al. 2025).

Based on the analysis of five examples of biophilic architecture, it has been established that the mere application of vegetation is not sufficient to link biophilia with the phenomenon of immersion in architecture. The analyses emphasised several elements that are crucial in achieving this: the experience of place and its immediate surroundings rather than the object itself; the support of a conceptual or narrative framework; the user’s predisposition to perceive and emotionally respond to architecture; and the user’s capacity for social identification with the place (a sense of belonging, identity, and connection with nature). The feeling of immersion becomes possible when a degree of detachment—physical or mental—from the external environment or context is achieved. The experience of place has the potential to generate an added experiential and emotional value for the user.

Other studies on biophilic environments have explored the notion of exercise immersion among athletes. It has been found that biophilic elements enhance the process of exercise and environmental awareness through cognitive and behavioural immersion, thereby improving the experience of being in a particular place. Immersion thus acts as a mediating factor—suggesting that mere exposure to greenery is insufficient, and that a psychological mechanism is required to engage the user (

Lee and Park 2025).

The proposed MMAAI method is based on qualitative and ethnographic research approaches, typical of social sciences—such as participant observation. However, it does not exclude the inclusion of quantitative methods, for instance, neuro-architectural studies or those employing virtual reality technologies. This demonstrates the potential for expanding the scope of future research. Such studies have been conducted before, though in different contexts, and did not concern real spatial environments.

Research on biophilic architecture in relation to the phenomenon of immersion has primarily employed immersive virtual reality (IVR) in order to identify the key environmental features of biophilia—such as natural light, ventilation, and greenery—and to examine their influence on physiological stress and comfort (

Di Giuseppe et al. 2024;

Al Sayyed and Al-Azhari 2025). Studies on biophilia have also highlighted the importance of a multisensory approach, combining visual and auditory stimuli, which were generated through projections and audio recordings, while ensuring other environmental factors characteristic of real-world settings were maintained under experimental conditions (

Aristizabal et al. 2021).

However, this raises a question regarding the experience of place and authentic interaction—a factor that has proven crucial in studies addressing biophilia within architectural contexts. Overall findings concerning benefits and satisfaction—such as enhanced agency and cognitive performance—are consistent with the results of the present research. Similarly, the concept of dwelling within a place, in this case an interior environment, aligns with our own observations.

Biophilia may thus be regarded as a strategy of transformative learning, enabling deeper comprehension and enriching spatial experience through narrative and experiential engagement.

7. Conclusions

Modernist architecture has traditionally conceived of space primarily as a technical object, subordinated to function. However, in the face of the climate crisis, there is an increasing need to redefine its role—space is now understood as an infrastructure that supports ecosystems and fosters the relationship between humans and nature. On this foundation, biophilic architecture has developed, integrating functionality with both humanistic and environmental dimensions. The new paradigm rejects the duality between humans and the material world (

Merleau-Ponty 1962;

Latour 1993), positioning immersion—an engagement that involves the senses, emotions, and imagination—as a key means of integration (

Murray 1997;

Freitag et al. 2020). Its origins lie in immersive art, which, since the nineteenth century, has transformed the viewer into a participant in the experience (

Grau 2004). Architecture adopts these strategies, creating spaces that promote interaction, collective meaning, and a deeper relationship with the environment (

Pallasmaa 2012).

Research indicates that immersion is not merely a subjective experience of the user but also results from the spatial and contextual mechanisms produced by architecture. Only the coexistence of spatial, narrative, and cultural elements enables a full aesthetic experience, the generation of meaning, and processes of learning. Immersive practices are thus transposed into architecture in multiple ways, calling for a transdisciplinary approach that acknowledges values and context as the framework of experience.

The analysis of five case studies demonstrates that immersivity in biophilic architecture arises from the synergy of nature, architecture, and technology, creating spaces that draw the user into complete physical, sensory, and emotional immersion. Central to this is multisensory engagement—vision, hearing, touch, and smell—as well as the aesthetic and atmospheric quality of place, fostering contemplation, introspection, and harmony. Immersion takes different forms depending on function, scale, and spatial character: in the University of Warsaw Library (BUW) and Crossrail Place, immersion is spatial and social; at the Musée du quai Branly, it is narrative and symbolic; in Bosco Verticale, private and quotidian; while at Eden Dock, it is multisensory and performative, involving direct contact with water and vegetation. Differences also concern the degree of control over nature—ranging from the wild and spontaneous landscapes of Eden Dock or the Branly Garden to the technologically managed greenery of Bosco Verticale and Crossrail Place—illustrating that immersion can be both spontaneous and engineered, yet its shared essence lies in deep user engagement within space.

Biophilic architecture fosters profound spatial experience through forms responsive to natural phenomena—such as seasonality, weather, ecosystemic processes, or succession—and through interaction with nature as an integral, living element of place rather than a mere decoration (

Wilson 1984;

Kellert 2008). These examples demonstrate how biophilic ideas are translated into practice: the University of Warsaw Library Garden merges functional library infrastructure with green spaces for relaxation; the Musée du quai Branly incorporates vegetation into the museum’s narrative; Bosco Verticale transposes the forest into a vertical urban structure; and the Crossrail Place Roof Garden creates a multisensory immersive environment in a transport and educational context.

Collectively, these projects show that twenty-first-century architecture has become a synthesis of technology, nature, culture, and experience—space is no longer merely a technical construct, but a dynamic, narrative environment that engages users and generates meaning. Immersivity emerges as both a design objective and a medium for communicating values, emotions, and meanings, enabling a deeper human connection with nature, place, and culture, and serving a transformative role in mediating the relationship between humans and the world.