This section presents the findings derived from the integrated analysis of quantitative data from art students, qualitative data from artist interviews, and visual data from selected artworks. These findings are structured around the study’s three core research questions: the extent of Confucian influence, the visual transformation of its core elements, and its role in shaping overall artistic style.

4.1. The Breadth and Cognitive Depth of Confucian Influence (RQ1)

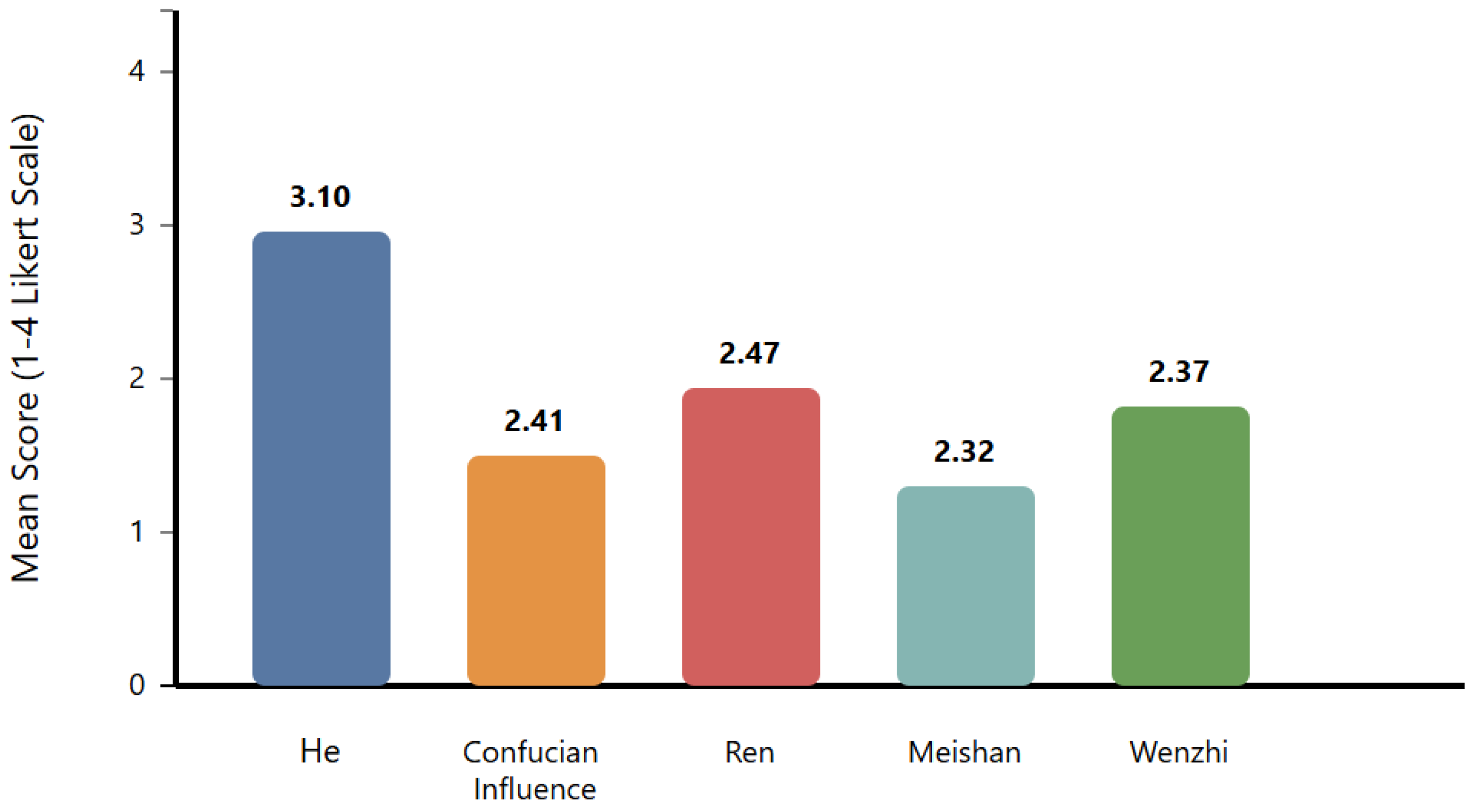

The first research question addresses the degree to which Confucianism influences Malaysian Chinese painters and their audiences. Survey data collected from 227 fine arts students reveal a general awareness of Confucian influence in art, with most respondents recognizing its presence in traditional aesthetic principles. The average score for perceived Confucian influence was relatively high (M ≈ 3.1 on a 4-point scale), suggesting broad recognition of its cultural significance.

However, this recognition does not translate into a deep understanding of Confucian philosophy. When asked about specific concepts such as “Ren” (benevolence), average responses dropped to a moderate level (M ≈ 2.4). This gap suggests a surface-level familiarity with Confucianism rather than a comprehensive conceptual engagement.

Further statistical analysis highlights significant factors influencing Confucian cognition. Regression results demonstrate that family support for artistic development has a positive correlation with higher levels of Confucian awareness (β = 0.231,

p < 0.01). In contrast, years of formal art education do not exert a significant effect. These results underscore the influence of familial and cultural transmission over institutional education in shaping philosophical engagement. As reflected in

Table 6, gender and academic seniority correlated with higher levels of Confucian cognition, which further underscores the mediating role of life experience and socio-cultural expectations.

In summary, while Confucianism is widely recognized within the art community, its conceptual depth remains limited. The influence is more diffuse and implicit, serving as a background cultural current rather than an explicitly articulated theoretical framework.

4.2. Visual Transformation of Core Confucian Elements (RQ2)

The second research question explores how core Confucian concepts—Ren (benevolence), He (harmony), Wen-Zhi (culture and substance), and Mei-Shan (beauty and goodness)—are visually reinterpreted by contemporary artists. Data from interviews and artwork analysis reveal a complex process of transformation rather than a straightforward representation.

Audience evaluations across the four Confucian dimensions—Ren, He, Wen-Zhi, and Mei-Shan—were relatively balanced, each showing moderate to high internal consistency as shown in

Table 7. Notably, Mei-Shan scored slightly lower, indicating that moral-aesthetic unity is more debated in contemporary visual narratives.

The concept of Ren is no longer confined to depictions of familial warmth but has expanded to include social critique and empathy for marginalized groups. Artists frequently juxtapose traditional symbols, such as maternal figures, with disjointed or distorted forms (e.g., masks, twisted limbs) to highlight psychological and social tensions. Interviewees describe this transformation as a way to extend Confucian care beyond the domestic sphere.

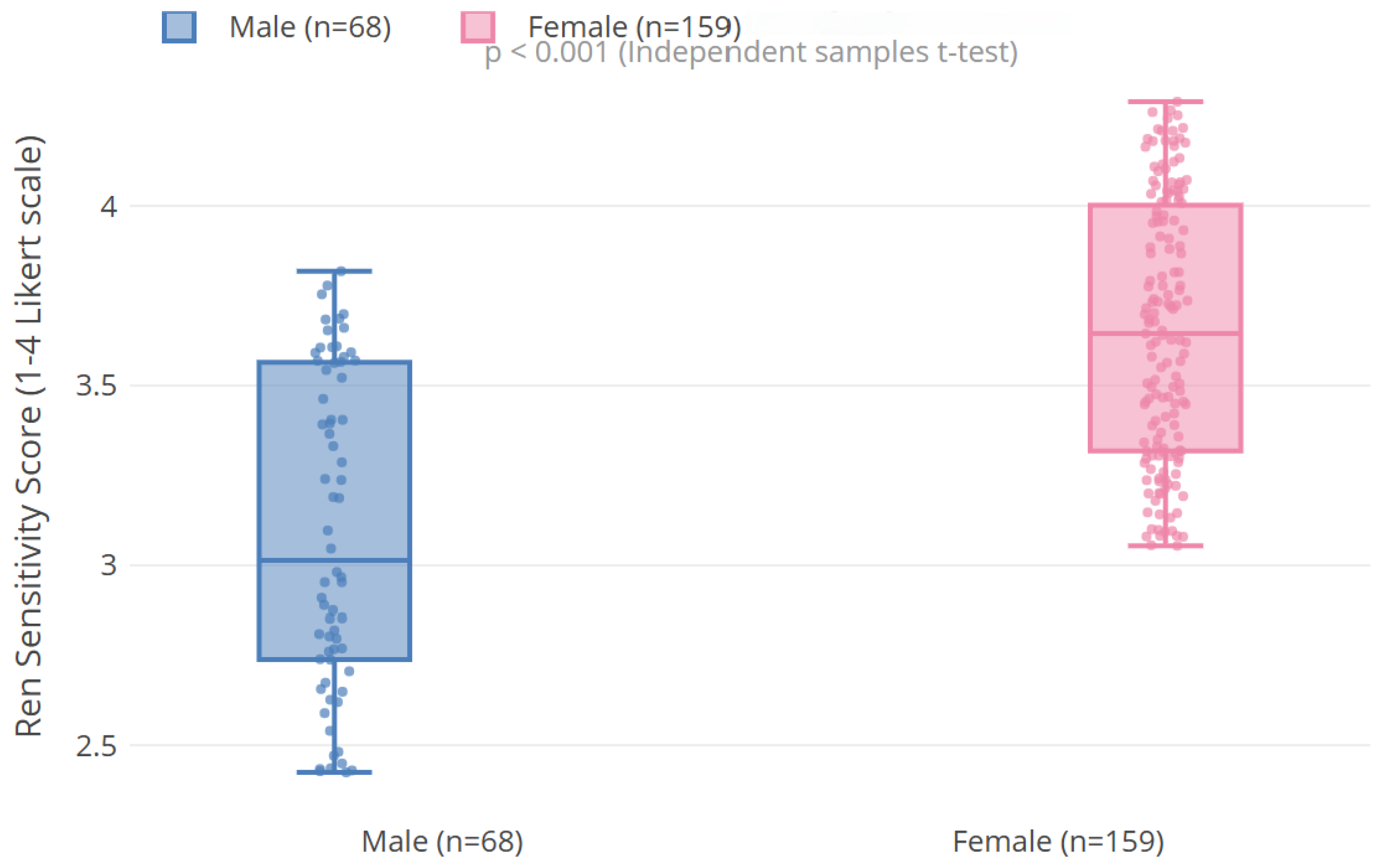

Figure 2 shows the differences in how respondents of different genders feel about the theme “Ren”. Female respondents exhibited significantly higher sensitivity scores (M = 3.68, SD = 0.63) compared to males (M = 3.12, SD = 0.71), with a

p-value less than 0.001, indicating a notable gender difference in sensitivity related to the ‘Ren’ theme, supported by a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.87). While no significant gender differences were observed in line expression (

p = 0.531), these findings align with interview results emphasizing feminine empathy within the context of Confucian reinterpretation.

Similarly, the notion of He is expressed not through compositional symmetry but via a dynamic equilibrium achieved through contrast and fragmentation. Artists integrate Eastern and Western visual languages, producing visual contradictions that invite active interpretation and engagement. Fragmented polyptychs and asymmetrical arrangements are employed to convey “harmony in difference,” reflecting a modern reinterpretation of the Confucian concept of balance.

The duality of Wen-Zhi emerges in the dialectic between technique and content. Interview narratives reveal a sustained effort to balance technical virtuosity with conceptual expression. Artists layer expressive brushwork with symbolic motifs, combining the textured materiality of linen with abstract forms. This strategic heterogeneity reflects a move away from aesthetic perfection toward philosophical depth.

Lastly, Mei and Shan are transformed from their traditional ideal of moralized beauty into a form of aesthetic realism. Artists address themes of trauma, decay, and ambiguity through images that embrace contradiction—such as the juxtaposition of a tiger and a child or the vitality within ruin. This shift suggests a contemporary reinterpretation of Confucian moral beauty rooted in emotional complexity and critical reflection.

Factor analysis of audience responses supports these qualitative findings. The four Confucian dimensions clustered into two principal components—moral-technical (Ren and Wen-Zhi) and aesthetic-harmonious (He and Mei-Shan), explaining over 68% of the variance. All dimensions demonstrated strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s α > 0.85), validating the structural coherence of these interpretive categories.

The two-dimensional factor loading plot, shown in

Figure 3, illustrates how perceptual items cluster around two distinct axes: moral-technical and aesthetic-harmony. This distribution confirms the structural independence while maintaining a conceptual connection between the dimensions. The key findings reveal that items from the same Confucian dimension tend to cluster together, such as all “Ren” items in the upper-left quadrant, confirming the structural validity of the model. Moderately cross-loading items like “Wen-Zhi” and “Mei-Shan” indicate some conceptual overlap, with correlation coefficients ranging from |r| = 0.15 to 0.25. The factor analysis suggests that Factor 1 reflects moral-technical aspects, encompassing “Ren” and “Wen-Zhi,” while Factor 2 captures aesthetic-harmony aspects, represented by “He” and “Mei-Shan.” Additionally, all dimensions demonstrated high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.91 for “Ren,” 0.89 for “He,” 0.87 for “Wen-Zhi,” and 0.85 for “Mei-Shan.”

These insights are summarized in

Table 8, which contrasts traditional Confucian visual elements with modern reinterpretations across symbolic, formal, and conceptual aspects.

4.3. Confucianism and Artistic Style Formation (RQ3)

The third research question investigates the extent to which Confucianism shapes the overall artistic style of contemporary Malaysian Chinese painters. Contrary to expectations of a fixed stylistic pattern, findings indicate that Confucianism acts more as a meta-framework than a prescriptive aesthetic guide.

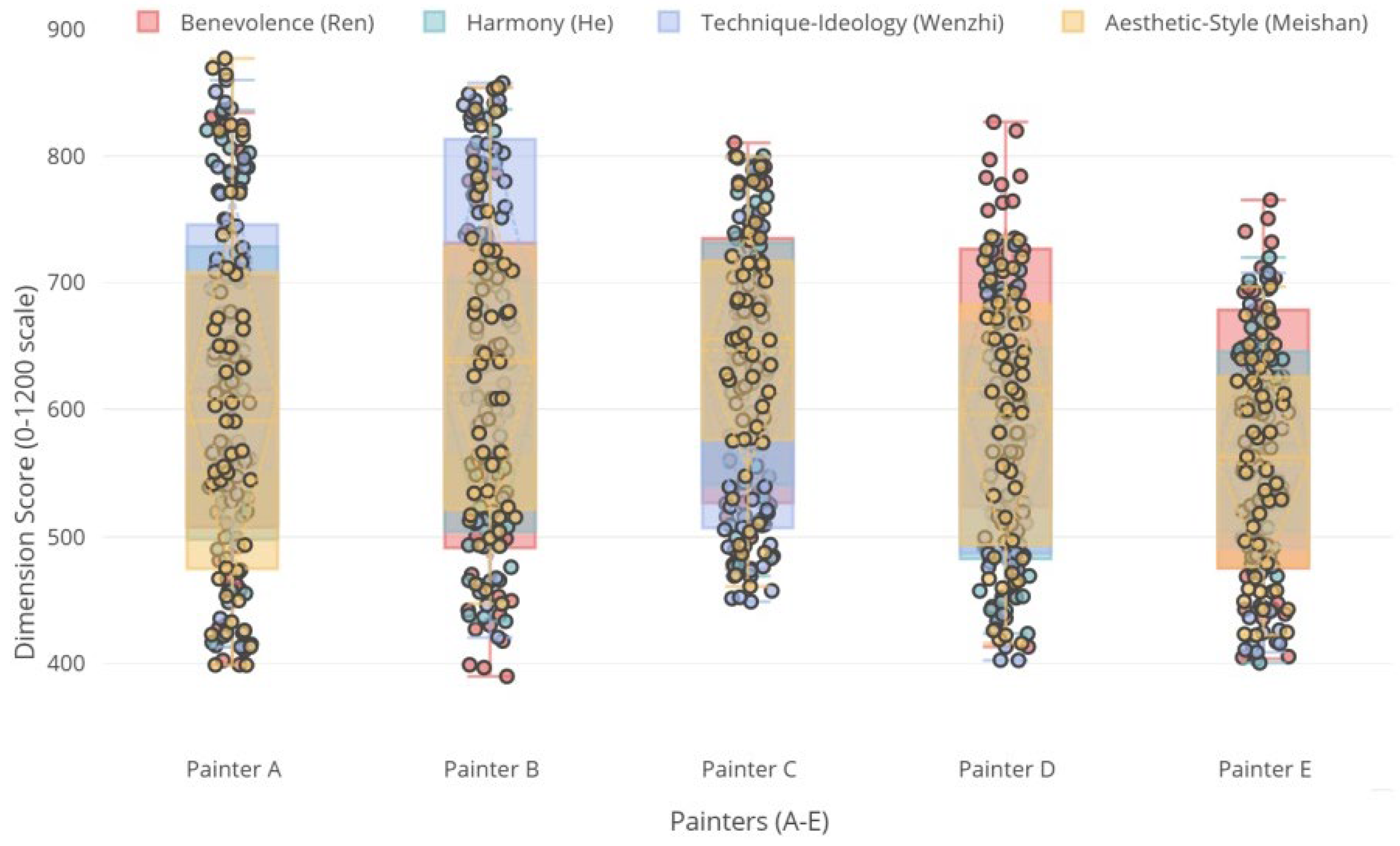

ANOVA analysis, as shown in

Figure 4, indicates no significant differences among painters across the four dimensions (Ren: F = 0.137,

p = 0.968; He: F = 0.655,

p = 0.625; Wenzhi: F = 0.642,

p = 0.634; Meishan: F = 0.724,

p = 0.578)—data sourced from the Quantitative Questionnaire Report. Key insights reveal overlapping score distributions among painters in all dimensions. The highest mean scores were achieved by Painter C for Ren (632.5), Painter B for He (636.9), Wenzhi (642.0), and Meishan (638.9). Conversely, the lowest mean scores across all dimensions belonged to Painter E (Ren = 588.8, He = 561.6, Wenzhi = 557.5, Meishan = 559.8). Standard deviations ranged from 139.3 (Meishan-PainterE) to 258.7 (Meishan-PainterA).

Audience evaluation scores across the four Confucian dimensions were consistent across all five artists, suggesting that although stylistic techniques may vary, the degree of Confucian integration remains comparably high. This implies a shared cultural ethos that transcends individual expression.

Thematic analysis of interview transcripts reinforces this point. While artists pursue diverse thematic interests—including postcolonial critique, gender identity, and familial memory—their recurring concerns with harmony, emotion, and ethical engagement suggest a deep-rooted Confucian sensibility. Terms such as “technical balance,” “emotional sincerity,” and “spiritual continuity” appeared frequently in the coded data.

Visual analysis further confirms this convergence. The recurrence of specific symbolic motifs (e.g., animals, nature, family, masks) and compositional techniques (e.g., fragmentation, layering, juxtaposition) across the artworks suggests an emergent aesthetic that is simultaneously critical and culturally grounded. This hybrid style merges local traditions with global art vocabularies, producing a context-sensitive visual language.

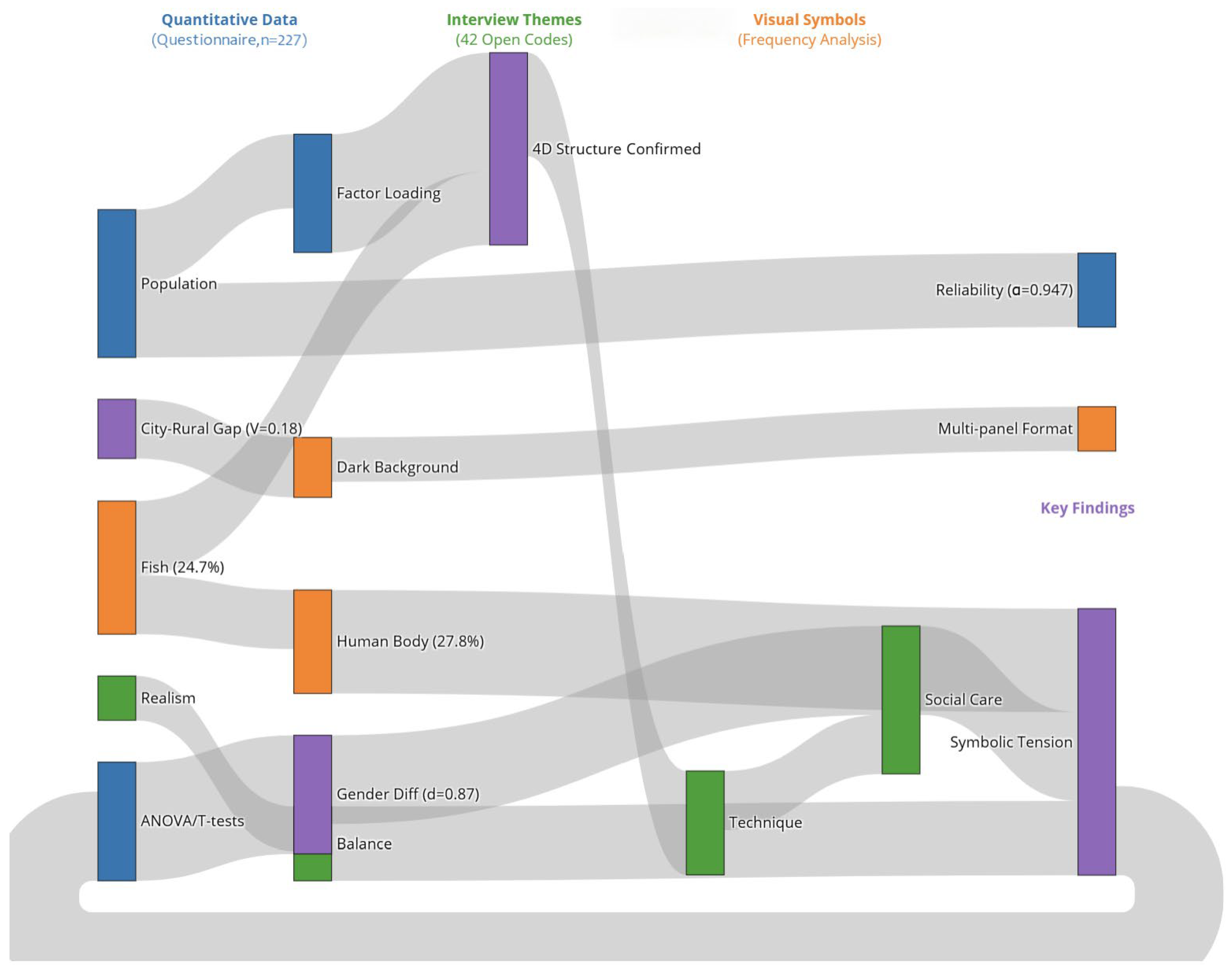

The diagram in

Figure 5 illustrates the integration of multi-source data comprising a quantitative questionnaire with 227 participants, interview coding of 42 themes, and artwork symbol frequency data. The data sources include population statistics, factor loadings with a high reliability (α = 0.947), and ANOVA/T-tests from the questionnaire; 42 initial interview codes categorized into four Confucian dimensions; and artwork symbols, such as fish (24.7%) and human body (27.8%), identified from frequency tables. Key findings reveal gender differences (d = 0.87) related to social care themes, a city-rural gap (V = 0.18) associated with dark backgrounds, and the validation of a 4D Confucian structure across all data sources. Additionally, symbolic tension connects interview themes with artwork symbols, highlighting complex interrelations.

In conclusion, Confucianism does not dictate a specific visual grammar but functions as an underlying value system that guides thematic orientation and expressive choices. It enables artists to maintain a culturally resonant practice while engaging with global discourses, thereby shaping a distinctive, interculturally aware visual identity.