Abstract

This essay argues that Holiday Powers’ s Moroccan Modernism (2025) offers a compelling case study for rethinking global modernist art from a decolonial perspective, highlighting Morocco’s unique creative, esthetic, and philosophical forces. The questions and issues this book raises, and this essay addresses, revolve around the problematic of non-European modernism as both a phenomenon of decolonial politics of esthetics, in the Jacques Rancière sense, and an artistic movement born out of the history of Western art through the colonial imposition of the European conception of modernity and system of education. I take particular issue with the dominance of political history, identity discourse, and redundant postcolonial rhetoric that characterizes not only Powers’ narrative but also the account of other area modernisms. This dominance generates a tendency to misestimate art agency and to neglect the investigation of the complex creative, esthetic, and philosophical underpinnings of the modernist construct. A lucid revisiting of Orientalism is mandatory for tackling this understudied aspect of modernism. Yet, I also demonstrate the accomplishments of Moroccan Modernism as a cogent historical exposition of this construct in Morocco, upon the basis of which future studies can be undertaken.

1. Introduction

With her first monography published in 2025, Moroccan Modernism, Holidays Powers adds another significant piece to the steadily growing building block of global or transnational modernist art studies, the latest outputs before it being Hamid Kershmirshekan’s (2023) The Art of Iran in the Twentieth and Twenty-first Centuries, Tracing the Modern and the Contemporary, Devika Singh’s (2023) International Departures: Art in India after Independence, and Anneka Lenssen’s (2020) Beautiful Agitation, Modern Painting and Politics in Syria. By “global or transnational modernist art”, I refer to artistic movements and discourses that emerged outside the traditional Euro-American canon but that are shaped by its concepts, institutions, and colonial histories.

Thus, the present article is the result of a thorough reading of Powers’ s monograph as a case of these studies, for which I have recently developed an interest (Gonzalez 2022b). Beautifully illustrated with high-quality images, this monograph focuses on the famous École des beaux-arts in Casablanca or Casablanca school, whose artists have founded the modernist movement in Morocco. It argues that Moroccan modernism emerged from the interplay of colonial legacies, rapid urban industrial transformation, and the agency of Moroccan artists educated within—and against—European modernist frameworks. Powers masterfully delivers an exhaustive historical account of this development of modernism in Morocco from the sixties to the early eighties, leaving no stone unturned as she explores a methodically gathered wealth of documentation including artist biographies, journals, exhibition catalogs, interviews, and other archives. These achievements directly support my claim in this essay that non-European modernisms cannot be understood solely through imported frameworks; they demand a historically grounded, locally inflected lens. Yet, Powers’ s arguments raise questions and leave some gray zones that need to be addressed. Fulfilling this need, my critique aims, in particular, to reposition Moroccan modernism as both a political and esthetic project, thereby opening new directions for postcolonial modernist studies.

2. Preliminary Epistemic Considerations on Modernism and Modernity

In Moroccan Modernism, the introduction itself compels a critique.1 As in all studies of non-Western modernism, in this introduction Powers defines her conception of the subject upon the factual premise that in postcolonial Morocco, like in all former colonies and mandates, “art was not just confined to esthetic debates—art was part of a public conversation about decolonization and meant to incite broader cultural change” (Powers 2025, p. 7). Equally, like in said studies, she “locates modernism at the intersection of art, culture, politics and activism” (Powers 2025, p. 7). However, Powers makes a point of distinguishing from theoretical precedents her own definition of the complex concept of modernity at the source of modernism’s transnational flourishing. This definition, posing some problems, requires a long quotation:

“This book defines modernity within the former colonies as a political project linked to decolonization and nation building… This definition differs from prevailing theorizations of modernity as the period of rapid social and political changes marked by specific and universal factors including urbanization and industrialization. Within this Eurocentric conception of modernity, modernism narrowly refers to the artistic responses provoked by modernization…Some theorizations of modernity assume the presence of universal factors including democracy, capitalism and secularism… This theorization would mean that the framework of European modernity can be directly translated into non-European cultures… [Modernity] can thus be framed as a political project elaborated through and against colonialism… Moreover, rather than seeing modernity as an inevitable social process, theorizing modernity as a political project is to dismantle the rhetoric of power implied through attendant definitions of the nonmodern” (Powers 2025, pp. 7–8).

In her eagerness to foreground the colonial oppression and the political response to it by its victims in the formation of global modernism, Powers overemphasizes politics to the expense of the other equally important cultural aspects of the phenomenon. She thus attempts to downplay the decisive role of the rapid social and politico-philosophical changes brought about by several major factors such as urbanization and industrialization, which, for modernity theorists, constitute the pillars of modernism’s formation. However, these factors indeed constitute such pillars. There is no way around the fact that the modernist condition is based on these changes and that, therefore, this condition is European in nature (Gonzalez 2022b).2 How could the modernist complexity have possibly taken place without the tide of European life-changing sciences, technologies, social models, and parameters of thought that unfurled on the world including, alongside industrialization, urbanization, secularism, capitalism, Marxism, materialism, the republic, individualism, citizenship, class outlook, art’s for art sake, photography, art as expression of free individuality, etc.?

This European condition of the modern has affected non-Western societies in one way or another, if not always in reality on the ground, at least in the reality of people’s consciousness. In the case of Morocco, the sole fact that the art school from which the Moroccan modernist avant-garde emerged was located in Casablanca, and not in Rabat, Tétouan, or Tangiers, attests to the fundamental role of industrialization and urbanization in the genesis of translational modernism. The country’s most modernized city and most opened unto the outside world, Casablanca was the urban location best equipped to embrace what modernity had to offer on all humanistic planes, an embracement without which the local modernist movement would not have arisen. We shall soon return to this argument.

Furthermore, in this same introduction, Powers slightly contradicts herself when she accuses, wrongly in my opinion, the modernity theorists of holding a “Eurocentric conception of modernity”, reducing global modernism “to the artistic responses provoked by modernization”, whereas she herself embeds Moroccan modernism in the history of the Casablanca art school and the oeuvre of its artists—which itself is a modernist institutional narrative (Powers 2025, p. 10).3 As she demonstrates throughout her book, art was pivotal to the shaping of the Moroccan modernist construct, together with the rich critical and political literature related to it such as the writings of the philosopher and postcolonialist Abdelkebir Khatibi. Yet, there is some truth in Powers’ s refutation of the term of “universals” often employed in these modernity theories. Implying metaphysical immutability, this term excessively empowers said operatory factors of modernization that, being by definition empirical, may at some point become obsolete and may be replaced by more up-to-date or contextually relevant forces. More accurately, owing to its outreach and spread, the period’s European modernization falls under the sign of a transculturalism of a global scope, which does not mean, however, that it has received universal acceptance.

Powers then applies to modernist art itself her over-politicized conception of modernity, defining it as “a political project linked to decolonization and nation building” (Powers 2025, p. 7). While she accurately “locates modernism at the intersection of art, culture, politics and activism”, she nevertheless reductively attributes the artistic intentionality subtending it to identity politics by positing that “the will to self-definition is far more foundational to artistic modernism than the modernist techniques taught in colonial art schools” (Powers 2025, p. 9). In other words, for Powers, modernist art was a mere pretext for achieving a political goal. In this respect, in spite of centering its narrative on an artistic production, Moroccan Modernism does not fully align itself with the latest studies on modernist art that are more attentive to the artworks’ agency and esthetic conceptualization. These studies have been indeed incrementally developing since 2007, when Kirsten Scheid pointedly remarked the following:

“The fact is very few studies of the Arab world specifically employ the lens of art to understand social issues… While sociologists of art have keenly identified the social networks and power relations that make art the production of so much more than a “gifted” individual, they have failed to explain what precisely can be deemed the agency of art in social interactions” (Scheid 2007, p. 6)4.

I take issue with Powers’ s misestimation of the philosophical–esthetic dimension of the modernist take on the subject of art in Morocco. Although no scholar worthy of the name would deny the contribution of the anticolonial and national motivations of artists hailing from the region for engaging in modernist artistic expressiveness, the narrowing of the latter’s significance to its discourse, as fundamental as it was, both stifles the esthetic power of the artwork as the complex carrier of this discourse and obliterates the multidimensionality of the visual artistic pursuit as a practice of choice. The Casablanca School was not simply a sounding board of postcolonial thought but a crucible where European pedagogy met Moroccan cultural priorities, producing an esthetic that was at once modernist and distinctively local. Minimized in Powers’ s book is the fact that these Moroccan modernists’ legacy actually resides in their artistic accomplishments. It is no accident, for example, that Mohamed Melehi stands out as one of the painters from the Casablanca school, if not “the” painter from that school, with the most impactful esthetic presence in the history of Moroccan modernism (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mohamed Melehi, Blue Moon, Mathaf (Museum of Modern Art), Doha, Qatar. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2025.

When one thinks of it, the voice of Melehi as a political activist does not particularly distinguish itself in the Moroccan decolonial–postcolonial chorus, but his painting definitely does among the country’s modernist artworks, thanks to its artistic quality of the highest caliber, in particular the uniquely personalized osmosis it operates between the Western geometric and color field type of abstraction, and traditional Moroccan aniconic forms. Among the numerous global venues that have exhibited his glorious oeuvre, a couple of years ago the organizers of the Shubbak festival of “Arab art”, which is held in London yearly, selected it to represent Arab–North African modernist painting.5

To finish with the perusing of the introduction in Moroccan Modernism, Powers finally wonders why the artists of the Tétouan school did not join the group of Casablanca and, as a consequence, did not enjoy a comparable success. She hypothetically attributes this state of affairs to “the different intellectual ways these institutions were constructed, and perhaps in part to language differences” (Powers 2025, p. 10). As said before, Casablanca offered the most fertile terrain for modernism to blossom, which was not the case of the other more conservative Moroccan cities. As for the argument of the language difference due to the double French and Spanish colonial history of Morocco, it has no validity. Language never constituted a communicational barrier between the different Moroccan regions simply because the local Arabic dialect never lost its currency, even in the country’s most remote corners.6

Let us now examine Moroccan Modernism’s eight chapters, which organize the discussions in chronological order following the Casablanca school’s history of rise and decline, thus crafting a view of the modernist advent in the country dominated by politics.

3. Contesting the View of Modernism as Less as an Artistic Adventure than as a Historical–Political Journey

Expectedly after an introduction presenting Moroccan modernism as primarily a local instance of decolonial history, and only accessorily or secondarily as an artistic adventure, the chapters detail the different historical episodes of the Casablanca school’s trajectory in the course of the twentieth century, until its decline in the eighties. From this historical viewpoint, Moroccan Modernism is most useful and accomplished. However, the few skillful descriptions of artworks illustrating this history, the citing of the artists’ discussions on their own work, and the rare, albeit fine, pondering by the author of their esthetic concerns do not make up for a largely subdued art inquiry. Another book is needed to address the multiple philosophical–artistic questions that Powers does not or cannot treat as she prioritizes the historical context and intellectual framework of Moroccan modernism.

Thus, in line with her project, in Chapter 1 of her monograph, the scholar depicts the Moroccan milieu brewing with revolutionary ideas under the French protectorate in which modernism emerged. Decisive changes in consciousness were being brought forth by what the postcolonial critical idiom calls “cosmopolitalism”, namely the compound of non-Western regionalist ideologies such as Pan-Arabism, Pan-Africanism, and “third-worldism”. The conductors of these ideologies included luminous anti-colonial literary figures such as Franz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, and C.L.R. James. On the local cultural ground, European modernity had shaped the Moroccan big cities thanks to campaigns of urban and architectural re-modeling, following the latest European principles and formulas. In addition, and non-trivially, European scholars had begun their enterprise of organizing, classifying, and categorizing Moroccan artistic heritage itself in its different historical phases, from prehistory to the modern times. This scholarly enterprise pertains to the broader Western endeavor to build knowledge on global art and cultures that took on a systematic form as early as in the eighteenth-century, with the creation of Eurocentric parameters of study and values of artistic assessment. To note, while the Western esthetic value system, which as we know is replete with prejudices and condescension, has been thankfully deconstructed and jettisoned once and for all thanks to postcolonial criticism, many of these parameters of study have enjoyed a continuous currency until today. Only relatively recently did these old critical tools go through a serious re-questioning with the academic decolonial movement.

Engaged in this contemporary decolonial movement, Powers rightly criticizes the inadequate application on Moroccan heritage of the typical Eurocentric hierarchized binaries of tradition versus modernity, the religious versus the secular, and crafts versus fine arts that served to articulate the colonialist vision of world culture. In postcolonial Morocco, it is the tension-filled entanglement of this imperialist imposition of structures of knowledge and art and esthetic politics—in the Jacques Rancière sense—with the Moroccan national awakening that gave rise to modernism as both an intellectual and artistic event. In this respect, Moroccan modernism more broadly reverberates what was happening in the colonized or formerly colonized world at large. Powers’ s depiction of this complex situation is historically well-researched and well-attuned to the facts. However, the privilege she bestows on decolonial politics produces a first shortcoming by compressing, instead of scrutinizing, what she eloquently calls Moroccan modernism’s “prehistories”:

“While artistic modernism was fundamentally bound to decolonization, there is a history of easel painting in protectorate-era Morocco that is often used as a signifier of modernist art histories in contrast to applied arts” (Powers 2025, p. 29).

The prehistories of global modernism in general are, however, far more complex than that. They begin in the colonial era, when pre-modernist Orientalism was penetrating artistic creation globally. Therefore, indeed the very existence of the modernist artistic revolution owes itself to this Orientalist history of easel painting as a European metaphysical approach to art that was nourished by Enlightenment ideas. These ideas had profoundly challenged the local artistic habits and the worldview that they served to project and signify for the local societies before colonialism, which, in the Arab world, drew from the Islamic tradition. Per this pre-modernist Orientalist intervention in the local visual-cultural fabric, the Moroccan and akin artistic modernisms followed the same esthetic–metaphysical deconstructive logic that gave birth to the Euro-American avant-garde; that is, the deconstruction of the European classical canons of art making. Raymond Williams exposes this logic limpidly:

“Although modernism can be clearly identified as a distinctive movement, in its deliberate distance from and challenge to more traditional forms of art and thought, it is also strongly characterized by its internal diversity of methods and emphases: a restless and often directly competitive sequence of innovations, always more immediately recognized by what they are breaking from than by what, in any simple way, they are breaking towards” (Williams 1989, p. 43).

It follows that, to fully comprehend the why and how of the Moroccan and coeval transnational modernisms, it is imperative to expose and fully comprehend their generative linkage with pre-modernist Orientalism, which constitutes the very source of their being. It must be understood, though, that these non-Western modernisms actually result from a double rupture with past legacies: the local and foreign European legacies. Powers justifies her sidelining of this major element of the modernist puzzle by pointing out the poor state of affairs of the research on European model-based Moroccan art before modernism:

“Very little research has been conducted on this early generation of painters, so it is difficult to obtain precise information, yet the artworks that exists attest to early experimentation in figuration and ways of picturing Moroccan life” (Powers 2025, p. 30).7

That is, however, more an excuse to not to touch upon the matter than a true state of scholarly affairs. A pioneer in the study of Arab modern art, Silvia Naef has produced a substantial body of work upon which Powers could have reflected in order to give at least some contours to the pre-modernist artistic modernity, without which there is no such a thing as modernism (Naef 1995, 2003a, 2003b; Naef and Radwan 2019).8 In a well-documented article, Naef asks and proposes answers to the still open question at the core of the non-Western modernist problematic: Peindre pour être moderne? Remarques sur l’adoption de l’art occidental dans l’Orient arabe (translation: To paint to be modern? Remarks on the adoption of Occidental art in the Arab Orient (Naef 2003a).9 For Naef, before the twentieth century’s decolonization, colonialists had ideologically coerced the Arab and a fortiori the other non-European artists from the colonized world to switch from their age-old traditional practices. The motivation of this coercion was that, under the impulse of the imperialist mission civilisatrice (civilizing mission), the Western rulers of the global artworld in the colonial period deemed these practices archaic and inferior to the superior European modalities of art making. More precisely, Naef defines this pre-modernist period as a phase of emulation that she presents as the result of a forceful push toward modernity, from which ensued the modernist upheaval characterized by identity affirmation. Her article focused on this phase of emulation as the abstract stipulates:

“The adoption of Western style art at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century in the Arab world is to be considered within the general modernization process, which coincided with it. Painting and sculpture became activities that aimed to prove that the Arabs were capable to become “civilized” people. Racist theories and reflections about the “essence” of “civilizations” were used in the debate about the necessity of introducing art in the Western way” (Naef 2003a, p. 140).

There is also Wendy M. K. Shaw’s excellent book, Ottoman Painting, Reflections of Western Art from The Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic (Shaw 2011) that Powers could have consulted for further clues on this key pre-modernist period, given that the Turkish world went through a similar process of reception of European modernity before modernism. Leaving this period unattended, Powers’ s modernist narrative sans pre-modernism provokes a flurry of unanswered questions and contradictions in the arguments she advances in Chapter 2.10

4. Questioning a Modernist Narrative Sans Pre-Modernism

Significantly subtitled “Mapping the Foundation Abroad”, Chapter 2 tackles the establishment of Moroccan modernism by the Casablanca school’s artists through their biography. Although, like throughout the text, this chapter attests to the author’s historical rigor, it unwittingly highlights the above plea for a critical return to pre-modernist Orientalism. This appears with particular acuity through the unsatisfactory argument Powers offers to explain the highly significant fact that, before founding the avant-garde in their homeland, these artists had acquired their modernist experience abroad, in the European capitals and in New York. I here summarize this argument by inserting some of her statements:

“Like Melehi, all of the artists that taught at the École des beaux-arts under the directorship of Farid Belkahia had studied and lived abroad before returning to teach in Casablanca” (Powers 2025, p. 41). Thanks to this training and experience abroad which shaped their “personal artistic styles… which reflected a modernist engagement with postcolonial national culture”, these artists brought forth a radical change in pedagogy in the Casablanca school’s protocol that upheld classical European rules of art practice. This utterly significant choice of spending time in Western countries in order to become acquainted with the avant-garde art and esthetic vision that made European modernism is then thus justified by Powers: “the lack of modern art infrastructure within Morocco compelled artists to go abroad to seek training and professionalization…There were virtually no galleries, … no fine arts museums” (Powers 2025, pp. 45–46).

But why, in the first place, would Morocco lack the cultural apparatus invented by the Europeans for supporting, displaying, diffusing, and consuming European art, an apparatus that originally has no relevance in the country’s own artistic workings? Powers’ s explanation does not heed the structural difference between the local Moroccan structures of art consumption, spectatorship, and distribution, and their European counterparts that regimented the artistic production issued from the écoles des Beaux-arts and transplanted into non-Western cultural spaces as a part of a wider colonial system of education. Considering that, by definition, in any location, museums, galleries, and other European types of exhibitory sites were created to respond to a large audience appreciative of Western art and to a lively market supporting its circulation, in colonial and decolonized Morocco such an audience and market did not exist just yet. Therefore, there did not exist a museological apparatus in the country. In fact, the art produced in these colonial art schools addressed a spectatorship that was totally alien to Moroccan society’s esthetic habits. If, individually, Moroccan artists could definitely be enticed to attend these schools and engaged in the European manner, this society remained widely unable to relate to this foreign artworld of autonomous canvas paintings hung on walls and free-standing figurative sculptures for no other purpose than representing themselves and the representations they contained. It takes much more time to change a societal habitus than an individual habitus.

It is no wonder then that, as Powers notes, initially it was a miscellaneous group of mostly European individual participants, collectors, critics, etc., hailing from both Morocco and abroad, including the Italian wife of Mohamed Melehi, Toni Maraini, who took the financial and logistical responsibility of showcasing and promoting the Moroccan modernist oeuvre for a limited privileged audience. For this very reason and despite all their noble socialist aims, the Moroccan modernists were locally perceived as elitist.

Powers’ s narrative raises two other correlated questions: Why were those twentieth-century Moroccan artists not simply satisfied with the exploration of the rich local legacies, desiring instead to experience the modernist avant-garde which, yet, pertained to the evolution of Western art? And why did these artists not chose to refuse the Western esthetic hegemony altogether in accordance with their political ideals and identity affirmation against European imperialism?

The argument of the paucity of modern resources in Morocco is obviously no sufficient answer to this complex interrogation. In addition, upon close inspection, it also bespeaks Eurocentric expectations that contradict Powers’ s anticolonial stance. Does she not insist that “the framework of European modernity can [not] be directly translated into non-European-cultures” because this would unfairly put, in Okwui Enwezor’s words, “a European epistemological stamp on its subsequent reception [of this European modernity]” by the non-Europeans (Powers 2025, p. 8)?11

The contradiction appears subtly in the tone of dismay with which Powers expresses the idea that modern institutions emulating the European models were missing in Morocco, somehow forcing the artists to leave their lives behind for some time. She thereby suggests that the colonialists should have built a more extensive art infrastructure alongside the art schools, an enterprise that, incidentally, would have further reinforced the decried Western cultural hegemony. This suggestion itself also implies, perhaps unwittingly, that after regaining independence, the Moroccans themselves should have showed more eagerness to build and sponsor such an infrastructure in order to facilitate the move of Moroccan culture in the direction of modernity. Such a move, by inference, problematically appears as the most desirable, natural, and logical thing to do, by definition, without any question or reasons for it to be so.

At any rate, one may wonder why the scholar does not balance this “absence” of modern facilities with another no less important deficiency in the twentieth-century Moroccan cultural landscape, namely the neglect of a significant part of the precious architectural heritage that was alarmingly falling in ruins. For example, a masterpiece of medieval Hispano-Maghrebi architecture and haut-lieu of Moroccan Islamic learning, the madrasa Ben Youssef had been left decaying for decades, until it was finally restored to its former glory just a few years ago; one may observe its dire condition in the 1998 Scottish film, Hideous Kinky, whose action takes place in the country.12 Funding this heritage’s preservation should have pertinently constituted a national priority for both the reconstruction of a postcolonial Moroccan identity through the arts and its representation on the international scene. Most bothersome is that the omission of this issue presents this heritage as a background frozen in time. Consequently, in Powers’ s narrative, against this frozen background the modernist endeavor’s liveliness pops out, even though, as she demonstrates in Chapters 2 and 3, the Muslim and Berber arts became a reservoir of forms and meanings for the avant-gardist artists to semantize their artworks with.

How, then, can one dissipate these contradictions and provide a more penetrating reading of the Moroccan artists’ decision to seek training abroad? To tackle this challenge, I propose to examine Enwezor’s concept of “the reception”, its political content aside, to “the mutability of European modernity” in the non-Western world.13 Painful, albeit creative and “reflexive”, this reception to this modernity’s intrusion as an overbearing foreign humanistic paradigm was, n’en déplaise to some, as much about resistance to coloniality as about embracement and appreciation of this paradigm.14 In my view, without understanding this embracement, paradoxical only in appearance, it is not possible to fully understand the Moroccan and the other transnational modernisms. To achieve this understanding, again one must return to the pre-modernist Orientalist past that brought about the necessary conditions for Moroccans and, more broadly, the non-Europeans to appreciate European modernity and to make it theirs. But for that, one must first revisit Orientalism itself as a cultural phenomenon.

5. Necessity of Revisiting Orientalism

Though mandatory, the reference to Edward Said’s (1978) Orientalism and to his other writings on the same subject, which Powers duly makes in Moroccan Modernism, is not only insufficient for establishing the generative linkage between pre-modernist Orientalism and modernism, but also, I dare to say, it can hinder progress in the knowledge on both.15 If Said and his followers were decisive in the denunciation of the colonial crime and its imperialist cultural mechanisms, in particular of the colonialist DNA of global artistic Orientalism as a child of it, they monolithically presented Orientalism as a colonialist crushing cultural force thrust upon a crushed victim, which then appears excessively passive in the face of it as the subject of an enforced hybridity. Silvia Naef’s aforementioned interpretation of the period of emulation of European art in the Arab world before the modernist revolution is, in this sense, of a Saidian vein. Because of this excess, the reality of the cultural prejudices of Orientalism yielded to another problematic reality, that of a scholarly prejudice against Orientalism. Fortunately, some critics have since then realized the acuity of this untold problem and, to remedy it, have undertaken a more nuanced, lucid, and dispassionate reappraisal of Orientalism.16 For example, in a most timely and pertinent essay Armando Salvatore writes:

“The emerging idea of transculturality replaces the paradigm of pure comparison between world religions and civilizations. It could also balance the deconstructive zeal of postcolonial critique. While postcolonialism has emphasized hybridity, transculturation challenges the orientalist obsession with authentic origins” (Salvatore 2021, p. 43).

In the art sphere, although undisputably fraught and imbalanced, the Orientalist colonialist–colonized relationship has similarly a much richer dynamic to it than that negative univocal directionality from one to the other depicted in postcolonial criticism, as in Naef’s article in which she foregrounds the catalog of colonialist misconceptions and describes a process of absorption of European modernity by the locals amounting to brainwashing:

“L’abandon de l’art traditionnel peut être attribué à la supériorité prêtée à l’art occidental comme à l’ensemble de sa production culturelle. Pour comprendre ce type de processus, il est utile de se référer à une anecdote rapportée par Ernest Gellner. Dans un article consacré à la domination coloniale, celui-ci affirmait que certains traits de la culture dominante peuvent, dans des conditions déterminées, venir à être considérés comme supérieurs, sans qu’il y ait à cela des raisons concrètes… objectivement parlant, il n’y a pas de raison de considérer un type d’art intrinsèquement supérieur à un autre; cependant, la culture européenne, dominante, parvint à imposer ses valeurs et ses concepts” (Naef 2003a, p. 141). (The jettisoning of traditional art can be attributed to the superiority that Occidental art as well as the whole of European cultural production were bestowed with. To understand this process, it is useful to refer to a story reported by Ernest Gellner. In an article dedicated to colonial domination, the latter asserted that certain features of the dominating culture, in certain determined conditions, could become perceived as superior without apparent reasons… Objectively, there is no reason to think that any art is intrinsically superior to another art; however, the dominating European culture succeeded in imposing its values and concepts).

Of course there was imposition, but it is this one-dimensional reading of the compliance or submissive reaction to it that poses a problem and demands further thinking. In the case of Turkish Europeanized painting, Shaw pointedly demonstrates the conscious and creative sophistication of this reaction, which also shaped the reception of European art in other areas affected in a way or another by Orientalism. Although concealed by the horrors of the colonial rhetoric, Orientalism indeed created a positively productive dynamic of esthetic influences going in both ways, from Europe to the rest of the world and vice versa, as well as a profound mutation of the conceptualities of belonging, ownership, and affiliation in the artistic practices for all cultures involved. Notably, this aspect of the Orientalist phenomenon gave birth to the multicultural Perennialist thought that unprecedentedly projected the idealist vision of a philosophical concord between the Oriental and Occidental religions (Gonzalez, forthcoming 2026). Let us just remember the Sufi Christian Louis Massignon (1883–1962) who famously ventured in the hermeneutics of Islamic art, with profoundly insightful, if not entirely solid, findings.

In an enlightening study, Lorsque la modernité vient d’Orient (When Modernity Comes from the Orient), Bernard Fournier does not critique Said postcolonial work directly but makes a much valid point in putting it in perspective, underscoring that “Une étude qui aurait englobé les XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles aurait nécessairement dressé un portrait quelque peu différent des relations entre l’Orient et l’Occident” (A study that would have integrated the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries would have necessarily produced a significantly different portrayal of the relationship between Orient and Occident) (Fournier 1988, p. 112). While focusing on China but with glimpses at other parts of the Eastern world, Fournier casts light on some unsuspected facets of said Orientalist dynamic in the domain of political ideas that go hand in hand with what was happening in the European arts and literature as early as the seventeenth century. Among a plethora of examples illustrating this phenomenon, one may cite the visual esthetic of Turqueries and Chinoiseries, the Grand Turc figure in Moliere’s plays, Montesquieu’s Lettres Persanes (Persian Epistles), and Rembrandt’s Orientalist figurations of Turkish, Persian, and Mughal inspiration. Fournier thus writes:

“En fait, précisément à partir de la fin du XVIIe et pour plus d’un demi-siècle, la Chine et l’Orient ont reflété bien davantage pour plusieurs Occidentaux l’image d’une certaine modernité. Cette perception que les Français tout particulièrement ont eue du monde chinois, fort différente de celle couramment admise, a joué un rôle fort important et méconnu dans l’évolution de la pensée politique du XVIIIe siècle. Ces idées ayant préparé, au plan philosophique, le terrain aux bouleversements de la Révolution française…” (In fact, precisely from the end of the seventeenth century and for more than half a century, China and the Orient have, for several Occidental intellectuals, remarkably reflected the image of a certain modernity. This perception that the French in particular had of the Chinese world, strongly different from the perception currently assumed, has played a very important albeit quasi-unknown role in the evolution of eighteenth-century political thought. These ideas having prepared, at the philosophical plane, the ground for the French revolution’s upheavals (Fournier 1988, p. 112).

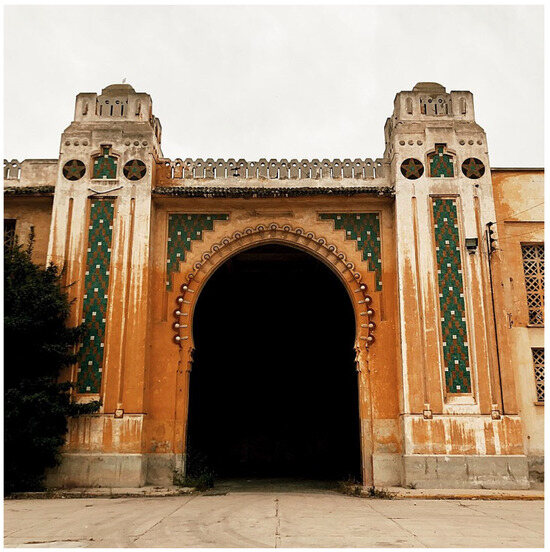

This Orientalist dynamic has also affected the MENA region and, a fortiori, Morocco. However, in Moroccan Modernism Powers masks it with her misrepresentation of Orientalism. Without it being too strident a pattern, her book comprises some inaccurate assessments of the country’s Orientalist transculturalism, bespeaking the symptomatic misguided equivalence between a much-needed decolonization of cultural studies and a counterproductive bashing of Orientalism that only repeats the excesses and blind spots of twentieth-century postcolonialism.17 In Chapter 1, for example, Powers makes this ill-grounded statement about Henri Prost who, together with other architects and urbanists of the French protectorate, presided over the modernization of Morocco’s main cities: “Under Prost, the “Arabisance” style pulled elements from Islamic architecture from throughout the Arab world and Spain without interest in the Moroccan local traditions” (Powers 2025, p. 28) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Neo-Mauresque Old Abattoirs in Hay Mohammadi, Casablanca, Morocco, renovated by Henri Prost in 1922. Photo in the public domain. CC BY-SA 4.0.

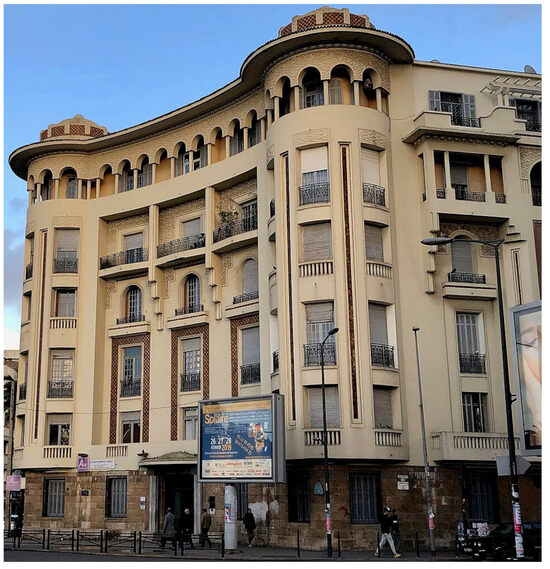

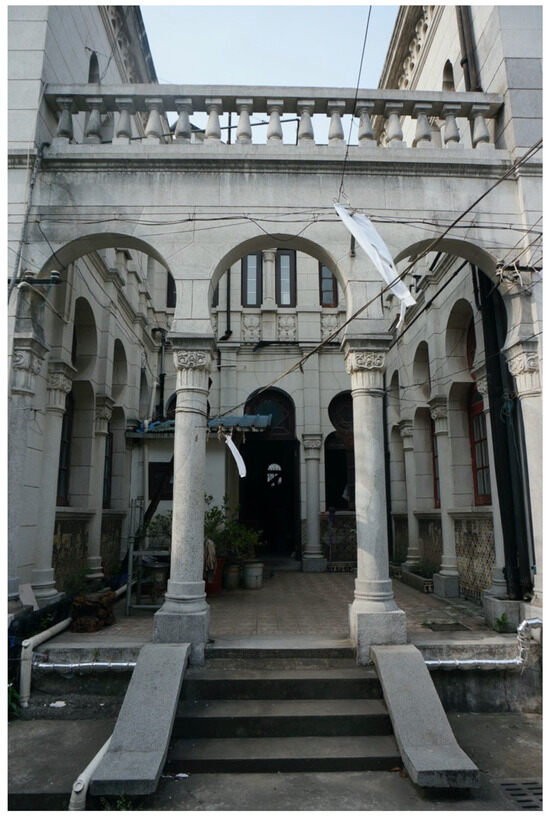

Such a baseless judgmental and demeaning evaluation of an architectural style that was very popular in the period does not heed the utter complexity of the colonial intellectual–esthetic attitudes in Protectorate Morocco and coeval colonized Arab lands.18 Above all, the French architectural and urbanist campaigns in the region certainly constituted instruments of domination, and of conquest accompanied by irreversible levels of heritage destruction in the case of Algeria. The architects of these campaigns also often held a condescending view of the local traditions. Yet, for all these disturbing features that shaped the Orientalist construct, this creative architectural output would simply not have seen the light of day without curiosity for the local models. Nor can it be reduced to a valueless masquerading fake. Prost’s valuable work actually represents the mandate period’s cross-fertilization between Europe’s avant-garde modernist architecture and the nineteenth and early twentieth-century pre-modernist current called “Alhambrism”. Having been contentiously called “neo-Moresque” or “Moorish”, the latter is an Orientalist style of design and architecture based on the inventive Western interpretation of the historical Hispano-Arab–Berber esthetic lore.19 Remarkably, this style attained a global scope of popularity and still remains in fashion in the Muslim world today, particularly in the Gulf region (Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 3.

View of the façade of the IMCAMA Building, Casablanca, Morocco. This building was designed in the Art Deco style by Albert Greslin and constructed in 1928. IMCAMA stands for “Société Immobilière de Casablanca et Maroc”. Photo in the public domain. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 4.

Old San Antonio national bank building, Texas, USA, built by Cyrus L.W. Eidlitz and completed in 1886. Photo of the author.

Figure 5.

Old San Antonio national bank building, detail of the plaque. Photo of the author.

Figure 6.

Residence on 250 Duolun Road, Shanghai, China. Photo courtesy of Shunhua Jin.

Figure 7.

Residence on 250 Duolun Road, view unto the courtyard. Photo courtesy of Shunhua Jin.

In addition, Powers herself cites the reputed architectural historian, Jean-Louis Cohen, who appreciates Prost and his peers’ oeuvre in colonial North Africa with more nuance:

“This architecture signified at one and the same time both oppression and modernization, which thus gave domination (and often cultural repression) concrete form, yet which also brought hope of liberation, through glimpses of other potential ways of living” (cited by Powers 2025, pp. 26–27).

Those “glimpses of other potential ways of living” very subtly suggest that European urban modernization is not to be monolithically rejected as it had brought about some form of improvement in the region’s living conditions, like it did in Europe itself. All in all, a better explanation of the advent of Moroccan modernist art can be advanced by critically integrating in it what I would describe as “the Orientalist esthetic structure of transnational modernism”.

6. Re-Explaining the Modernist Advent in Morocco

Even though the modernist avant-garde against the European esthetic classical canons was taking place in the Euro-American zone, the deconstructive logic underlying it did not spare esthetic consciousnesses in the non-Western artworld. As discussed above, pre-modernist Orientalism had already generated a tight entanglement between the Western and non-Western conceptions of art whereby, beyond the power imbalance, both parties profoundly inspired each other through what I would call “the Orientalist reciprocal gaze”. Apart from the contentious Western Orientalist painting, let us not forget the significant role that non-Western global art played in the European modernist revolution’s formation itself.20 The explosion of flat surfaces and patterns that prepared the Euro-American esthetic of abstraction is owed to the Orientalist consciousness and vision of the like of Owen Jones, William Morris, and Henri Matisse. A corollary of Orientalism, the esthetic discovery of African art buttressed the avant-gardist decomposition and geometrization of the classical figurative forms that Picasso implemented in Les Demoiselles D’Avignon and cubism, which also played a substantial part in the Euro-American journey toward abstraction. Another known instance of this role of non-Western art in Western modernism is the inspirational reception of the 1910 Munich exhibition of Islamic art by Henri Matisse, Wassily Kandinsky, and others revolutionary artists of the period.

We may say that, early on, Orientalism had created something of the order a “nomadic thought” which, in the artistic domain, ultimately triggered a rhizomatic expansion of the modernist spirit, to borrow Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s most efficient representational language in A Thousand Plateaus (Deleuze and Guattari 1987; Gonzalez 2022a).21 Applying this “Deleuzoguattarian” model of process philosophy to the present inquiry, if modernism is definitely a Euro-American product, as its spirit crossed the Western cultural space’s boundaries it became the esthetic property of no one and everyone.22 To put it in another way, non-Western modernism was not exactly borrowed or acquired abroad as some form of forceful cultural appropriation. Indeed, a pivotal feature of the rhizomatic–nomadic paragon in Deleuze and Guattari’s philosophy of multiplicity and assemblages is the loss of its own origin that the rhizome entails once it is at work. Unlike the arboreal growth that preserves the root and defines itself by it, the rhizome owes its existence to the destruction or disappearance of its source, which then allows for an unhinged construction of autonomous conglomerates. The latter, however, always remain linked to one another through what the French thinkers call “a line of flight” (ligne de fuite), a sort of conduit of energy, material or conceptual, that ensures the rhizomatic vitality.

The Modernist Rhizome and Its Network of Lines of Flights

The tense and intense Orientalist reciprocal gaze as well as the rhizomatic artistic growth it permitted to create throughout the world transpire through discussions in which were engaged different early twentieth-century European and non-European actors, artists like literati and art critics. In a double article teasingly entitled Picasso the Muslim (Flood 2016–2017), Barry Flood provides a very useful compilation of these discussions.23 For example, the Egyptian scholar Bishr Farès gave a lecture in Cairo in 1952 in which he argued about “the affinity of picassisme with Arab-Muslim conceptual art” (cited in Flood 2016–2017, p. 44). That these ideas, from the contemporary scholarly viewpoint, were objectively correct or incorrect seldom matters. It is the esthetic–philosophical significations of the bridging associations they make that does. These significations wrapped the Orientalist transcultural encounter with a rich intellectual envelop that nurtured the creative desires and creativity of the artists hailing from the colonized or former colonized world’s great cities, which were exposed to the successive fluxes of European modernity. These fluxes formed the founding network of lines of flight whereby both the pre-modernist Orientalist rhizome and modernist multiplicities came to be and to expand rhizomatically.

That is how, against this background of the old Orientalist collusion between the Western and non-Western artworlds that was channeled through the art schools and the transcontinental travels of European creators and intellectuals, the future modernist artists of the Casablanca school came to develop an interest in the last esthetic output of these fluxes of modernity, namely the modernist avant-garde. Through this interest, an instance of a line of flight in Deleuzoguattarian language of nomadic thought, these artists artistically identified themselves with the Euro-American artisans of this avant-garde, an identification that motivated their long preparatory sojourn in the European capitals and in New York. Consequently, it is not the lack of possibilities at home that prompted this sojourn abroad, but the appeal of the Euro-American avant-garde that could penetrate the esthetic consciousnesses in any worldly location with an Orientalist history of modernity. More than that, considering the generic ontology of the avant-garde as a deconstructive artistic movement, in the twentieth-century context such a movement could not have taken place anywhere else than in the West so that the non-Western artists touched by this appeal had to reach out to that Western avant-gardist cell by building a line of flight with whatever practical means: distant apprenticeship, traveling, or exile. Let me explain this a priori obscure, albeit important, point.

In theory, owing to its revolutionary nature, any artistic avant-garde in any given spatiotemporality can only be circumscribed to specific locations presenting the necessary conditions allowing it to rise against the normative establishment. While the establishment has, by definition, a steady hold throughout the cultural space that initially put it in place, the avant-garde that challenges this establishment operates in and lives off of its anti-normative exceptionality. However, once the avant-garde succeeds in taking over the establishment, it is avant-garde no more as it loses this quality of exceptionality that defines it, thereby becoming itself the norm, until the advent of the next breakthrough. And thus goes the cycle of the establishment yielding to the avant-garde, becoming, in turn, the establishment.

If we then look at the modernist situation through this theorical prism, it appears clearly that, per the European condition of twentieth-century modernity, the avant-garde was exclusively located in the Western big cities, whereas the classicism-based establishment reigned over both the rest of the Western world and the colonized or formerly colonized areas, including Morocco. Had the latter country, by any chance of history, benefited from the presence of museums and other European institutional support, that presence would not have changed this state of affairs. While Morocco was enmeshed in the old global pre-modernist Orientalist rhizome, the activity of the modernist avant-gardist cells in the Euro-American zone was preparing the advent of the new rhizomatic growth of modernism. Even though this modernism rapidly shed its Euro-American rootedness through its global rhizomatic spread, thus creating the multiple and diverse transnational modernist assemblages that we know, for the avant-gardist adventure to effectively shift “location of culture” and to morph itself into something novel and pertinent for the non-Western world, it needed the creative force of a centripetal movement/line of flight from this world to those Euro-American centers of avant-garde.24 Apprenticeship and emulation are the motors of this centripetal force-based process of transference of artistic identity.

However, apprenticeship and emulation, not to be equated with servile copying, are no easy procedures to go through. Apart from the inevitable failures and poor achievements these procedures entail before obtaining successful results, there are the painful psychological, philosophical, and sociological clashes that the transcultural transference necessarily occasions.25 Chapters 1–3 of Moroccan Modernism describe the varied torments the Casablanca school’s artists endured so as to become avant-gardist modernists in their own right in their own country. While they felt that their cultural difference set them apart in the West, conversely, their unorthodox artistic choice put them in an awkward position at home. Moreover, as they staged artistic modernity in Morocco after they return from abroad, a florilegium of doubts, contradictions, upheavals, and other harsh twists and turns marred the confrontation the Moroccan artists set forward between their modernist revolutionary proposition and the country’s double conservative establishment, namely the European classicism taught in the art schools and the local age-old Arab–Islamic–Berber traditions. Powers meticulously peruses the momentous exhibitions, beginning with the Rencontre Internationale in Rabat, and the other cultural–political events that framed this staging, all commented on and recorded in the critical literary production that surged as a result of the intrusive introduction of modernism in Morocco. She particularly finds a trove of material to probe in the journal Souffles, which constituted the most influential modernist intellectual platform in the country.

At last, thus setting foot on the Moroccan soil, the modernist avant-garde morphed into Moroccan modernism in the true ipseitic sense of the wording; that is, into a modernist assemblage distinct from its Euro-American analogous. Powers enunciates with descriptive finesse the processes whereby this phenomenon of artistic ipseity took place, which relied on the political semantization of the artworks and the insertion in them of formal, spiritual, and poetic references to Moroccan pluralistic heritage. Still, much more needs to be done to unravel this fruitful crossing of the international modernist idiom with the age-old Moroccan modes of visual expressiveness, in particular with the latter’s Islamic constituent.

7. Looking Back at Moroccan Islamic Art Through the Modernism Prism

As Moroccan Modernism cogently shows, under the impulse of both the modernist esthetic quest and the questioning of dubious colonial classifications of the local visual forms in inferior categories such as “pure decoration” and “naïve art”, the Casablanca school’s members, like their peers in the Arab world, acquired a new heightened consciousness of their homeland’ visual cultures.26 In particular, this kind of rediscovery of the national patrimony through the prism of modernism engendered a most intriguing confluence between the two esthetic currents of Western geometric abstraction and aniconic Islamic patterning. Generally poorly understood by Islamic art historians and unattended in Powers’ s book, this confluence awaits a serious case study. Concretely, it manifests itself both in philosophical reflections and in plastic experiments such as the adaptation of Arabic calligraphy to gestural abstract expressionism, patterned color field, and hard-edge-paintings. For example, the Algerian modernist painter Mohammed Khadda extolls the metaphysical grandeur of Islamic abstraction in this comparative argument:

“Rejecting figuration in favor of a stylization, an ever-increasing abstraction, contrary to the plastic traditions of antiquity, which rather saw in nature the exterior aspect of things, Islam produced a metaphysical art from which the anecdotal was excluded—an art of mysticism whose claim was to perfect and refine the spirituality of man” (cited by Flood 2016–2017, p. 262).27

In “Picasso the Muslim”, Flood notes that “For Khadda and many other Arab writers[-artists], the existence of an indigenous tradition of abstraction valorized the production and reception of modern abstract art in the Arab lands as a variant on the already known rather than a foreign import” (Flood 2016–2017, p. 262).28

On her side, Powers contents herself with stating vaguely that “there is the suggestion of a system created within abstraction” (Powers 2025, p. 147). However, in Chapter 4, she has more to say on this return to the national patrimony as she probes new events and period texts illustrating the maturing of Moroccan modernism overtime.

As abstraction, figuration, patterns, writing, and symbols of diverse sources construct a mixture of styles, in this chapter Powers presents the artworks in a kind of taxonomic form that leads her to conclude that this modernism was “a movement held together by ideas more than by aesthetics” (Powers 2025, p. 102). In this presentation, alongside calligraphy, arise the two important themes of ornament and religion. Powers demonstrates how, potently inserted in the Moroccan modernist elaboration, these staples of Arab, Berber, and Islamic visual culture subvert the Western binaries of tradition versus modernity and art versus craft. She interestingly underscores, however, that some artists explicitly credited their inspiration from Bauhaus esthetics for realizing the fallacy of this hierarchical dichotomy between fine art and craftmanship, and not, as one would expect, from Islamic ornament itself (Powers 2025, p. 120); this inspiration constitutes another line of flight connecting the Euro-American modernist assemblage to its Moroccan counterpart within the broader rhizome of global modernism.

As for the crucial question of spirituality, Powers mentions Mohamed Melehi’s association of his paintings’ characteristic wave patterns with prayers (Powers 2025, p. 126). Otherwise, she prefers not to further consider this question as the Moroccan modernists themselves did not seem to elaborate much on the relationship between their artistic practice and their faith (Powers 2025, p. 212). I, however, strongly object this sidelining of the question. If only through their use of Arabic calligraphy, an explicit referent to the sacred in Islamic visual culture, the Moroccan modernists, like their Arab peers, surely activated some form of religious signification in the artistic material, silently but effectively, whether they spelled it out in writing or in recorded conversations, or remained mute about it.

In fact, the religious thought or sentiment in transnational modernist art poses the delicate problem of the exact extent of the impact or resistance to the Enlightenment idea of secularity that coloniality had insinuated in the collective consciousness of non-Western societies, which were originally unconcerned by the sacred–secular binary (Gonzalez 2022b). Morocco and the precolonial Muslim world at large belong to these societies. Besides, this problem did receive attention in other area modernist studies (Dadi 2010; Naef 2003b; al-Zāhī 2006; de Pontcharra and Kabba 1999; Khatibi and Alaoui 1989; Ali 1997; Sijelmassi 1972). Notably, a recent article by Iranian academics discusses Islamic calligraphy as a symbol of resistance to the process of Westernization in the arts, postulating that “Islamic artists turned again to calligraphy as a symbol of resistance and an element that was born out of Islamic civilization to find identity, and get rid of the consequences of colonialism, and reproduce indigenous culture” (Amani et al. 2021).

The Moroccan case, whose political structure has uninterruptedly revolved around the religious legitimacy of its Islamic monarchy from Islam’s inception in the region until today, definitely compels an investigation on the visual expression of spirituality or the lack of thereof in the colonial and postcolonial era.

8. More Events, More Stories, and the Demise and Legacy of Moroccan Modernism

In Chapter 5, Powers tackles the politics of culture the Casablanca school developed under the dire circumstances of the aptly named long “years of lead”, under King Hassan II’s authoritarianism. She expounds how the decolonial socialist and humanistic ideals the artists expressed through their art and promoted in collaboration with decolonialist philosophers, writers, and critics, turned into a threat to the Muslim monarch’ s political-religious absolutism. Creating a fissure in the national project, this situation forced the Moroccan modernists to walk a tightrope between remaining faithful to their original political vision and avoiding to provoke the authorities. All the while, they had to maintain relevance in relation to their modernist peers in the rest of the Arab and African world, in which the multiple variants of anti-colonial, revolutionary, and Marxism-inspired intellectual movements were more powerful than ever. If, as Powers asserts, “transnational solidarity was central to the project of Moroccan modernism”, at home they confronted a new form of oppression entirely Moroccan in nature (Powers 2025, p. 185).

In other respects, during these years economic and educational inequality in the Moroccan society was firmly increasing, thereby reinforcing the discrepancy between the artists’ idealistic intellectualism and the dire reality of the Moroccan ordinary population they wished to involve in their public displays. The mirroring of the Euro-American anti-capitalist currents of the avant-garde, like Situationist International founded in 1957 and active until the beginning of the seventies, could not work in Morocco as the population could not relate in any way to these displays.29

Chapters 6 and 7 continue to narrate the political–social activism and particular struggles of the Moroccan modernists during these years of lead as the fading socialist dream, the Israeli–Arab conflict, and the antithetical Pan-Africanism and Pan-Arabism began to provoke cracks in their intellectual–artistic cohesion. Powers exposes in particular the limits to the Pan-Arab national project, which was put to the test by the disaster of the 1967 Six-Day War. Due to said conflict, the Moroccan Jewish painter, film maker, and faculty of the Casablanca school, André Elbaz, was faced with the dilemma of choosing political allegiance; he eventually emigrated. Other modernist artists felt overwhelmed by the extreme politization of their practice or sensed a loss of their intimate Moroccan identity under the tide of sweeping grand ideologies that did not necessarily reflect the Moroccan reality and its specific needs and preoccupations. In sum, profound anxiety of the individuals and extreme collective effusion for big causes formed the two faces of Moroccan modernism during this phase. It is then no accident that the artistic medium of the poster, mixing eloquent revolutionary imageries, texts, and graphic design, became very popular.

Finally, Chapter 8 covers the Casablanca school’s disintegration and the slow ending of Moroccan modernism’s saga during the eighties, as the disillusions of the varied revolutionary ideals became more apparent and the postmodernist globalization of art loomed. To note, museums, galleries, and other art centers were by now showcasing Moroccan modernism in bonne et due forme. On the subject of the art’s discourse, the opening unto the Arab world had taken over the pluralist modernist project. Powers detangles with her usual heedfulness the historical complexities subtending this saga’s last episode, justly pointing out the pressure on the artistic practices and the insidious undermining of freedom of thought to which the powerful Pan-Arab drive gave rise. To put it in another way, at its final stage, Moroccan modernist art was facing the dangers of excessive didacticism, on top of those of the government’s crackdown on anyone daring to challenge the Moroccan social–political order under the king’s yoke. The declarations and proclamations of the Moroccan artists and their intellectual supporters in journals and other venues betray the ominous unease these pressures exerted on their mind.

In Powers’ diligent account of the multiple tensions that underlined the Casablanca school’s ending, I would give more weight to the antagonism between the Moroccan preoccupation with the Africanity based-Berber question and the Pan-Arab ideology that dominated the last years of Moroccan modernism. Under the apparent sentiment of togetherness and solidarity this all-engulfing ideology was fostering, frustrations were simmering because of this antagonism, as stifled as it may have been. Moroccan Berbers did not claim their cause as remotely loudly as their Algerian neighbors, since in Morocco the main social–political confederating factor has always been overtly and traditionally Islam, unlike in post-independence secular Algeria. Here, the ethnic and cultural differences that the French colonialists had efficiently instrumentalized to consolidate their power became even more exacerbated with the foundation of the Algerian state, which made an enforced linguistic and cultural Arabization its chief policy of social refashioning. Yet, as the references to the repertoires of Berber geometric patterns, signs, and symbols in the Moroccan modernist artworks show, the Berber consciousness was very much alive in Morocco as well. The question of “Arabness” versus “Berberness” still constitutes a contentious cultural issue today in Morocco like in Algeria.

9. Conclusions: An Open End

Ultimately, the inexorable force of the postmodernist glocalization tamed these tense dialectics between the local and global that this last episode of the Moroccan modernist history was fostering. Powers’ s well-conceived conclusion of her book discusses the aftermath of the Casablanca school’s demise as Moroccan modernism turned into a formidable contribution in the country’s century-old patrimony, whose effects can still be felt in contemporaneity. On point, Powers illustrates this period of passage from an era to another with the work of two remarkable Moroccan females artists: Malika Agueznay, herself a former student from the Casablanca school, and Yto Barrada, an acclaimed contemporary multimedia practitioner living in the USA, but with a foot in Morocco. While Agueznay’s magnificent patterned paintings are the direct product of that school, Barrada’s versatile installations reflect the glocalization of the artistic practices in contemporaneity. Nevertheless, Barrada does embed her oeuvre in the Moroccan artistic culture in multiple manners and forms. In one of her installations, she formulates the name of Hubert Lyautey in brightly colored building blocks, thus re-actualizing Moroccan modernism’s anti-colonial political discourse.

Actually, the latter piece illustrates another understudied facet of modernism, namely its distinctive rhizomatic ramifications in postmodernism and contemporary art. It also pinpoints what Moroccan Modernism does and does not deliver in terms of knowledge on the modernist phenomenon. While the book does narrate colorfully and thoroughly the political history of Moroccan Modernism, thus constituting an indispensable reference for anyone interested in the enthralling subject of modernism in the MENA region, it projects a too narrow a view of it by not doing justice to the art agency, the power of which Barrada’s work eloquently displays. This power must be critically dissected in the study of modernism, like in that of any cultural movement using artistic expressiveness as a major, if not its main, instrument. This power must also be seen as the product of a complex knot of historical, philosophical, and esthetic phenomena with roots in the past and ramifications in the future. Modernism, it has been hopefully shown in this essay-book review, lies at the center of such a knot whose extreme complexity remains in need of unraveling. With this open perspective, I hope that the critiques proposed have traced some exciting directions of research to pursue.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The critiques I am substantiating throughout this essay and the pinpointing of occasional incorrections should by no means be taken as a negative assessment of Holiday Powers’ s book, but rather as a constructive reflection addressing these issues. |

| 2 | Be it understood that Europe does not have the monopoly of modernity, even though it has imposed a historical evolution curve following its own modern order begun in the Renaissance and climaxing with modernism. For example, outside this evolution curve, we can certainly describe as a moment of modernity the early Abbasid Caliphate’s intellectual and scientific flourishing, in particular its developments in mathematics and geometry thanks to the foundation of the Bayt al-Hikma (House of Wisdom) in Baghdad, in the late eight century. These developments, as we know, irradiated far beyond the medieval Muslim world’s boundaries. |

| 3 | Paul Mattick offers a good description of the general epistemic state of affairs of modern art and esthetics in (Mattick 2003). |

| 4 | See (Scheid 2007, pp. 6–23). Regarding these recent studies, see (Seggerman 2014; Lenssen 2017; Naef and Radwan 2019). |

| 5 | See the details of the 2025 issue of this festival here: https://richmix.org.uk/events/talks-to-reframe-the-arab-world-presented-by-afikra/?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_term=2025-06-03&utm_campaign=June+12th+Live+Rich+Mix+London+-+afikra+x+Shubbak+Festival (accessed on 3 July 2025). |

| 6 | Although there exists an anthropological literature to attest to this Moroccan linguistic construction, I am here speaking out of a life time experience of the Maghreb and familiarity with its cultures (I was born in Algeria). |

| 7 | See Silvia Naef who, in an important article, pertinently ponders this question: why, before modernism, did artists from the Arab world paint in the European figurative manner? (“Peindre pour être moderne?”) (Naef 2003a). In her book, Powers does not cite Naef’s essential work, though it pioneered the study of non-European pre-modernist and modernist art. |

| 8 | Bafflingly, Powers does not even cite or mention this foundational work in modernist studies. The French language Naef predominantly uses in her writings could not have been an obstacle since Powers seems familiar with it; for her book, she has extensively investigated Morocco’s modernist literary material that is also written in this language. |

| 9 | This and all the other translations from French into English in this text are my own. |

| 10 | Pre-modernism is not to be confused with the premodern era or premodernity, which corresponds to the medieval period before modernity in the European canonical arrangement of periodicity in global cultural history. |

| 11 | Here, I repeat Powers, who cites these words by Enwezor in p. 8. |

| 12 | With regard to this film, see the cinema website IMDb: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0136244/ (accessed on 3 July 2025). |

| 13 | Again, I repeat Powers, who cites these words by Enwezor in p. 8. |

| 14 | The term is borrowed from Iftikhar Dadi, who talks about “the reflexive quality of modernism” (Dadi 2010, p. 14). |

| 15 | See my review of a book exemplifying this shortcoming of contemporary decolonization in the frame of Islamic art studies in (Gonzalez 2020). |

| 16 | See this sample of new critiques of Orientalism: (Long Hoeveler and Cass 2015; Almond 2007). |

| 17 | Here I would refer to my chapter on the Perennialist legacy in a forthcoming volume (Gonzalez, forthcoming 2026). It contains an ample bibliography on the subject. |

| 18 | Powers is not alone in engaging in this counterproductive and often erroneous bashing of the Orientalist legacy. This bashing remains a steady trend. To mention another similar (albeit more severely erroneous) example, Margaret Graves provides a totally counterproductive misrepresentation of the British Orientalist Owen Jones’s work in (Graves 2018, pp. 62–65). |

| 19 | Regarding the Alhambrism style, see (McSweeney 2015, 2017, 2020). |

| 20 | See the rich catalogs of two important recent exhibitions: Re-Orientations. Europe and Islamic Art from 1851 to Today, held at Kunsthaus Zurich, 24 March–16 July 2023 (Zürcher 2023), and Inspired by the East: How the Islamic World Influenced Western Art, held at the British Museum, 10 October 2019–26 January 2020 (Greenwood and Guise 2019). While the former show’s catalog contains very interesting interviews with contemporary artists, the latter’s catalog initiated a much-needed critical revisiting of Western Orientalist painting. These stimulating events pertinently propose new ways to look at this complex material. See also on the influence of Islamic art on Western art (Labrusse 2011). |

| 21 | See my employment of this text to make an argument on Islamic ornament in (Gonzalez 2022a). |

| 22 | This term is found in philosophical studies on the texts written by the two famous French thinkers. See https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13603110701238769 (accessed on 4 July 2025). |

| 23 | Powers does not cite Flood’s two-part-piece in Moroccan Modernism. Anyhow, unfortunately, apart from these valuable historical information and citations, this piece is misleading from the critical viewpoint. Its author does not grasp and, as a result, does not analyze these discussions for what they intellectually reflect and signify in depth, namely this stimulating reciprocal gaze for all involved. Instead, to argue his simplistic view that Islamic art has no particular inclination for aniconism and abstract esthetics because it does employ figuration, he painstakingly pinpoints the misperceptions and inaccuracies on the Bilderverbot question that these thinkers and artists of another era held and proffered. For example, he mischaracterizes as a “perceived penchant for abstraction” (Part 1, 48) the factual investment in abstract art in premodern Islam. Or, he chastises Gabriele Münter, Kandinsky’s travel partner to Tunisia in 1904–1905, for confusing the impossibility of representing the divine in Islam with an Islamic prohibition of images as, says Flood, “she insisted that ‘the Moslem interdiction of representational painting seemed to stir his imagination,’ fostering an interest in abstraction”, (Part 1, 58). This presentation demeans the inspirational dynamic that contributed to the birth of Western abstract art. Moreover, the fact remains that, despite their confusion on the Bilderverbot in Islamic visuality, the intellectuals and artists in question rightly identified the latter’s phenomenal non-representational dimension. Therefore, it simply cannot be suggested, as Flood does, that these Western viewers totally lacked esthetic discernment regarding Islamic art. In addition, by no means the Islamic investment in abstraction signifies that representation did not thrive in Islam. Instead, it signals a different approach to the dialectics of abstraction-figuration in this context. Kandinsky himself, as well-known, had a revelatory encounter with Persian book painting, which is figurative and representational. |

| 24 | This expression is borrowed from the title of the book written by the famous South Asian postcolonialist Homi Bhabha (Bhabha 1994). |

| 25 | Here, I wish to pinpoint the task art criticism should undertake in order to identify these failures, poor achievements and successful accomplishments of non-Western modernism. They are an integral part of the global modernist rhizomatic history; therefore, by no means do they diminish the value of this brand of modernism. Yet, too often masterpieces are obscured by being mixed up with the plethora of underachieved artworks in exhibitions, catalogs and scholarly literature alike. I am, however, aware of the controverse surrounding the very notion of masterpiece. My opinion on this matter is that masterpieces can definitely not be separated from lesser artistic productions as if they had come to be in isolation, the product of pure genius. Nonetheless, masterpieces do exist due to superior accomplishment and should be identified as such, although it is not always easy or self-evident to discern this quality of superiority. A good example of that is Johannes Vermeer’s painting whose artistic exceptionality took centuries to be recognized, but it did eventually, and no one would contest this fact today; it has entered history as no less than an extraordinary masterpiece of seventeenth-century Dutch art. Therefore, if attention is paid to the inevitable variance of artistic quality in Western art, there is no reason for not doing the same regarding the non-western modernisms whose masterpieces equally deserve acknowledgement. |

| 26 | On this rediscovery of the local cultures in the Arab world, see (Naef 1995, 1996, 2003b; Ali 1997; al-Zāhī 2006; de Pontcharra and Kabba 1999; Sijelmassi 1972). These references are not cited in Moroccan Modernism. |

| 27 | To note, the first name of Khadda is spelled Mohammed, while that of Melehi is spelled Mohamed. Flood cites Mohammed Khadda from his texts Éléments pour un art nouveau suivi des feuillets épars liés et inédits, published in Algiers in 1972 and 1983, although he idiosyncratically approaches the subject of abstraction, elliptically refuting without much argument the very existence of this confluence between the two non-representational art forms, and accusing of anachronism and of “emphasizing superficial formal analogy” (pseudomorphism) scholars, curators, and critics past and present who have discussed these features or who have staged them in museums and galleries in the form of comparative exhibits (Flood 2016–2017, pp. 42–43). |

| 28 | This noting by Flood appears in contradiction with the arguments he attempts to advance in “Picasso the Muslim”. Indeed, while he acknowledges that Khadda and other Arab modernist artists bring together European and Islamic abstract art in both thought and practice, he deems unfounded or superficial the connection between the two. |

| 29 | Regarding this movement, see https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/s/situationist-international (accessed on 15 August 2025). |

References

- Ali, Wijdan. 1997. Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity. Gainesville, Tallahassee and Tampa: University Press of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Almond, Ian. 2007. The New Orientalists: Postmodern Representations of Islam from Foucault to Baudrillard. London: I.B.Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- al-Zāhī, Farīd. 2006. D’un Regard, L’autre: L’art et Ses Médiations au Maroc. Rabat: Marsam. [Google Scholar]

- Amani, Hojat, Hasan Bolkhari Ghahi, and Sedaqat Jabbari Kalkhoran. 2021. Islamic Calligraphy, a Symbol of Resistance to the Process of Westernization (Based on the Theory of Postcolonial Studies). Bagh-e Nazar 18: 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bhabha, Homi K. 1994. The Location of Culture, 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dadi, Iftikhar. 2010. Modernism and the Art of Muslim South Asia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus, Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated and Foreword by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Pontcharra, Nicole, and Maati Kabba, eds. 1999. Le Maroc en Mouvement: Créations Contemporaines. Paris: Éditions Maisonneuse & Larose. Casablanca: Malika édition. [Google Scholar]

- Flood, Barry F. 2016–2017. Picasso the Muslim Or, How the Bilderverbot became modern (Part 1 and Part 2). RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 67/68: 42–60, 251–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, Bernard. 1988. Lorsque la modernité vient d’Orient. Politique 13: 111–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, Valerie. 2020. What Is Islamic Art? Between Religion and Perception: Wendy M.K. Shaw, 2019, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019, 366 pp. Al-Masāq 32: 110–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, Valerie. 2022a. Debunking the Regionalistic Myth in the Discourse on Islamic Ornament. In Deconstructing the Myths of Islamic Art. Edited by Sam Bowker, Xenia Gazi and Onur Ozturk. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, Valerie. 2022b. Theorizing the Spiritual-Secular Binary in Modern and Contemporary Art of- and by Artists from- the SWANA Region. In Dossier Thématique, ‘Whither the Spiritual? Rethinking Secularism’s Legacy in Post-Ottoman Art. Edited by Hannah Feldman and Kirsten Scheid. Beirut: University St-Joseph. Regards 28: 137–52. [Google Scholar]