Restoring Authenticity: Literary, Linguistic, and Computational Study of the Manuscripts of Tchaikovsky’s Children’s Album

Abstract

1. “Sketches of Unconditional Simplicity”?

Since a while ago, I’ve been thinking that it would be nice to contribute to the children’s music literature, which is not rich at all. I want to create a series of little sketches of unconditional simplicity with the titles that would be attractive for children, like Schumann’s [titles]. (our translation)

Letters are never entirely sincere, at least judging by myself. Regardless of my correspondent or my reason for writing, I am always concerned about the impression that the letter will produce not only on my correspondent, but even on some casual reader. As a result, I pose. […] Whenever I read the letters of eminent people after their deaths, I am always troubled by a vague feeling of falseness and deceit.

2. Introduction Proper

2.1. Perception Points and Research Questions

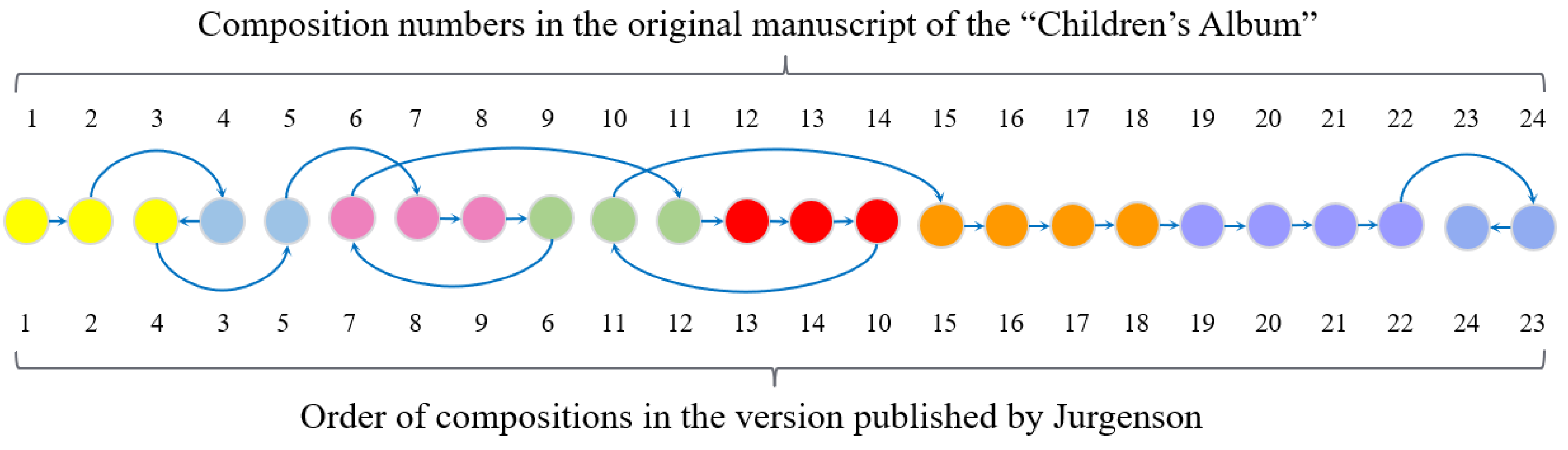

- What is the possible meaning and implications of the reordering of the pieces in many published editions compared to the original manuscript;

- In what extent the structure and music contents of the Children’s Album can be considered as the imitations of Schumann’s approach in his Album for the Youth;

- What is the impact of transformations applied to the original manuscript on the pedagogical and cultural value of the whole work.

- 4.

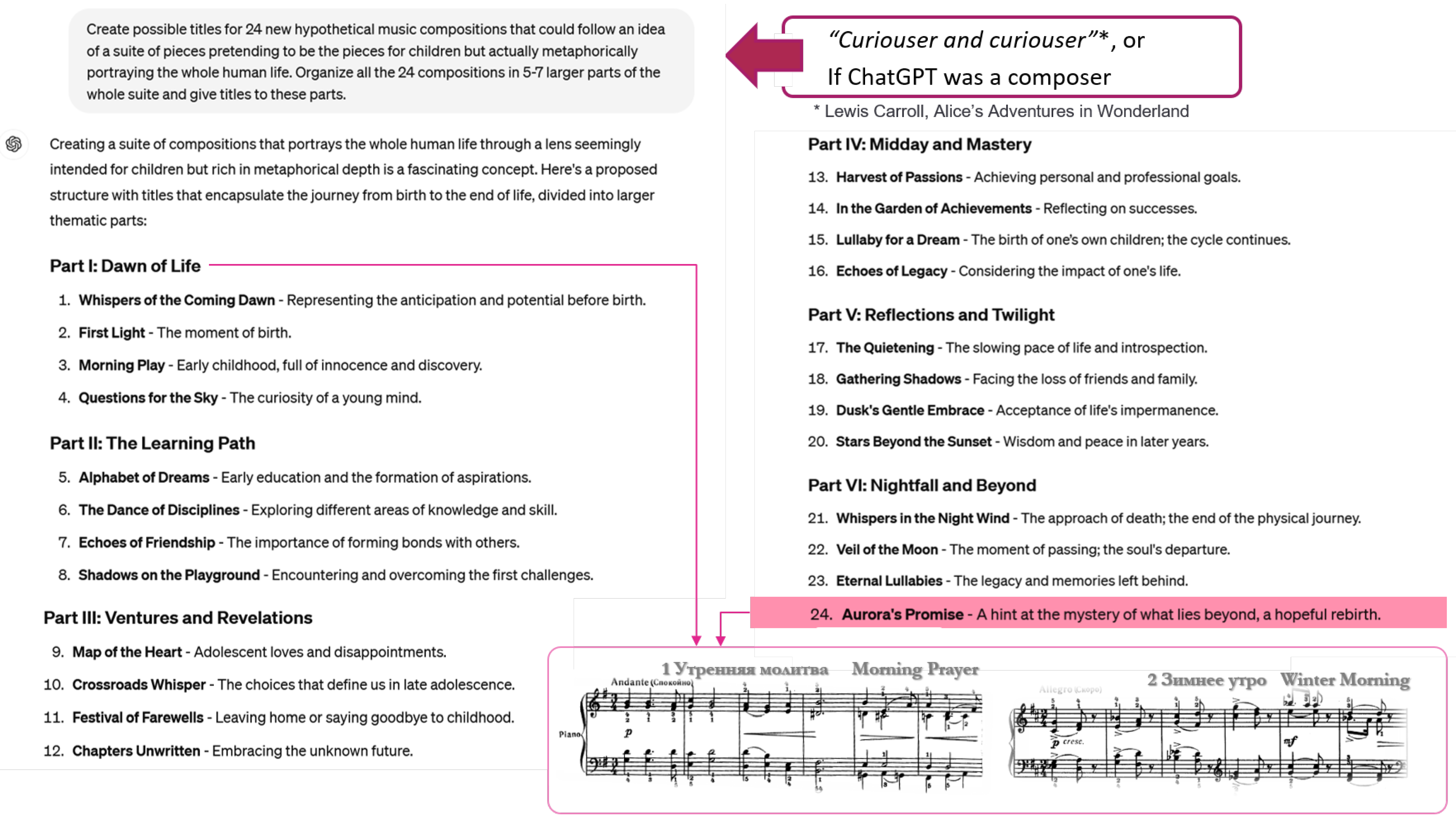

- How an Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology, such as Large Language Models (LLMs) can help to explore both the relevant and irrelevant common views to the compositions; and

- 5.

- What are the possibilities of the computational models, such as pattern elicitation algorithms for extending the musicology studies.

2.2. The Illusion of Objectivity

2.3. Reifying the Research Context

2.4. Contributions to the Research Literature

- We investigate the prevailing perspectives on the compositions from the Children’s Album using the interaction with an LLM-driven AI agent.

- We identify how the reordering of the music pieces from the carefully crafted original manuscript impacted the perception of the musical contents of the Children’s Album.

- We address the question regarding the degree of influence or imitation of Schumann in the Children’s Album.

- We describe the possible enhancements of traditional musicology studies with the help of AI-driven technology, such as pattern elicitation algorithms through linguistic and musical analysis.

- We examine the transformations applied to the original manuscript from the perspective of their impact on the pedagogical and cultural value of the whole work.

3. Methods at a Glance

3.1. Computational Methods Extending Musicology Analysis

3.2. Traditional Linguistic Methods

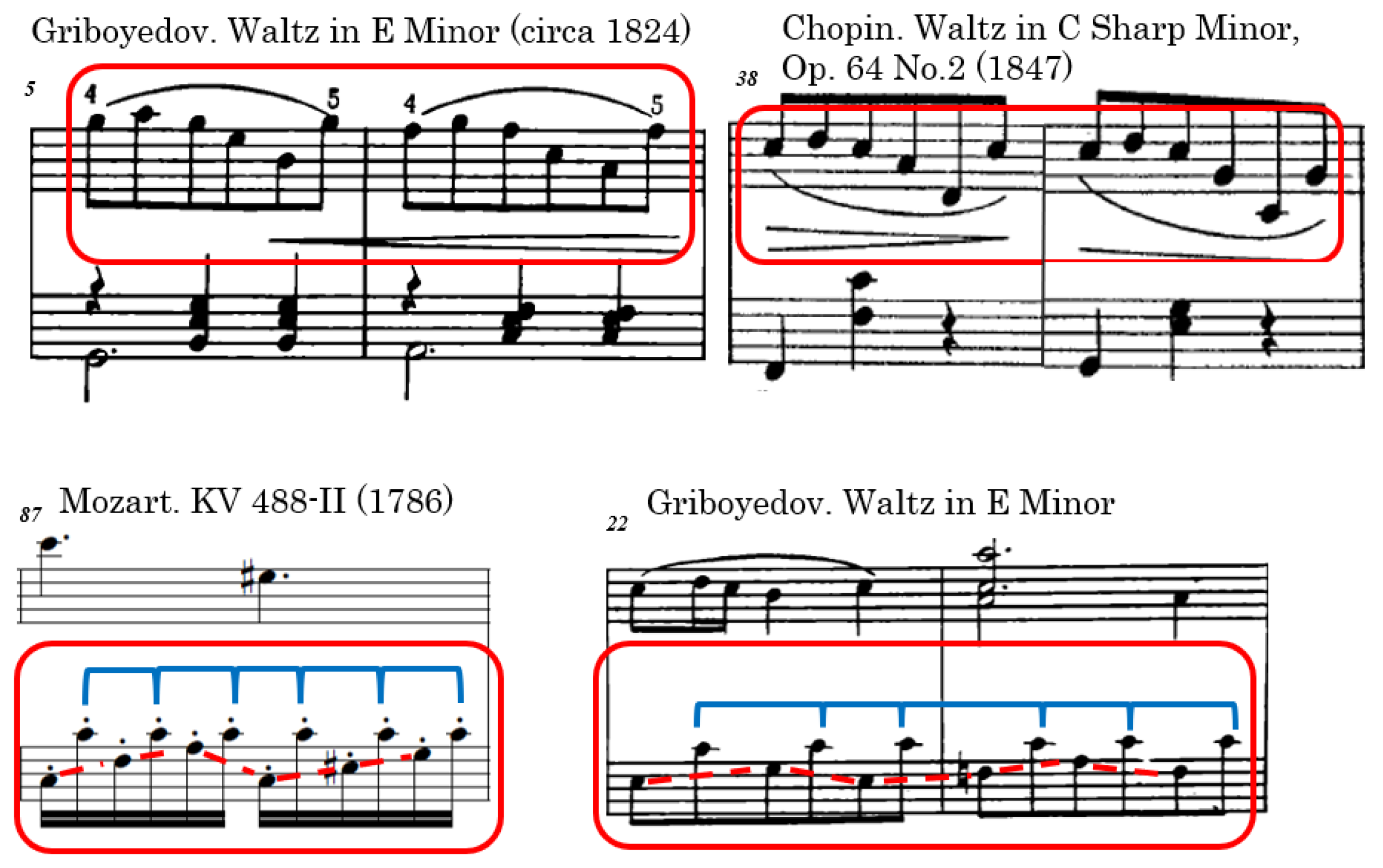

4. Related Musical Literature

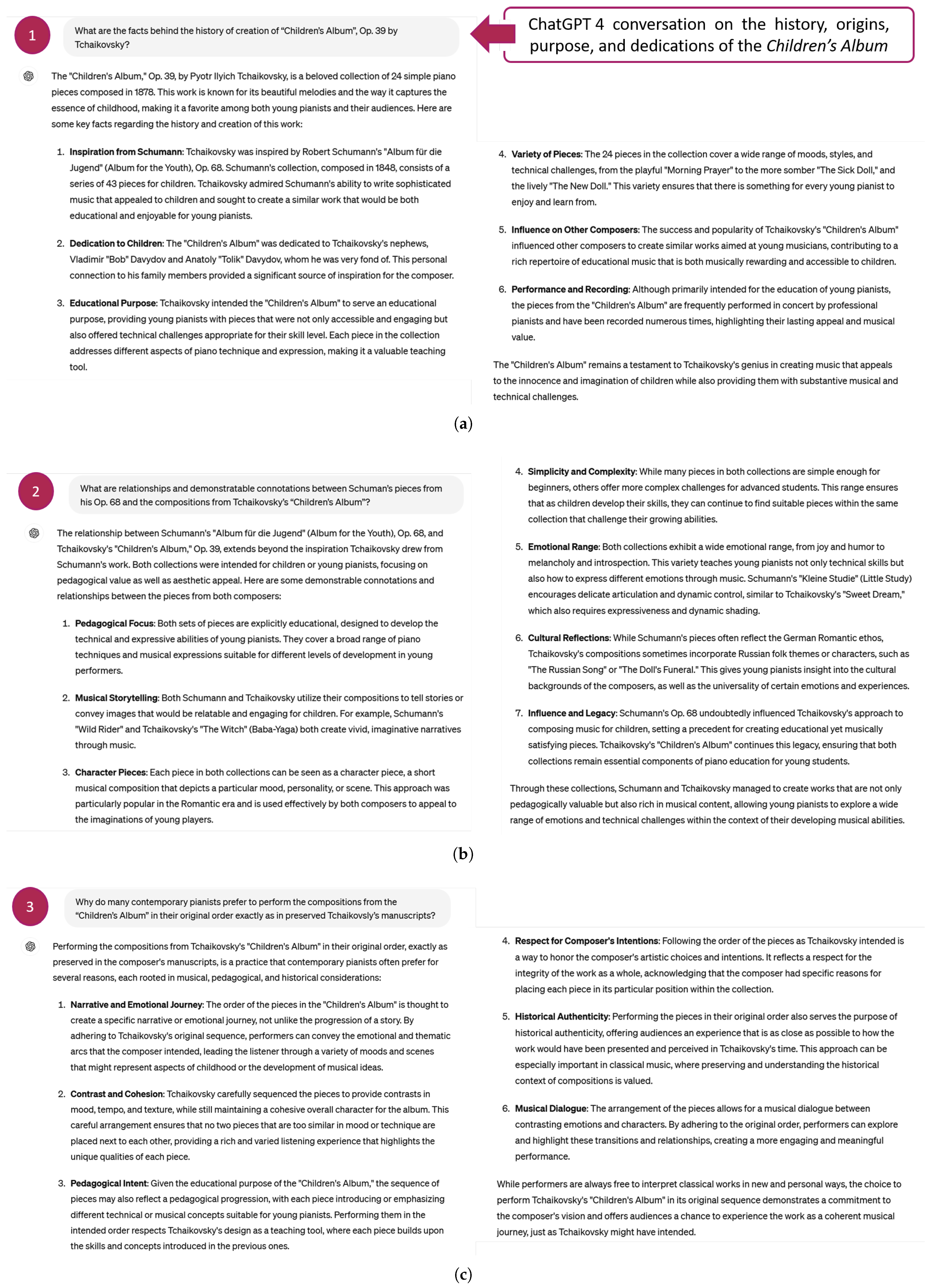

5. Tchaikovsky, LLM, Common Views, and Myths

- 3.

- Why do many contemporary pianists prefer to perform the compositions from the Children’s Album in their original order as in the preserved Tchaikovsky’s manuscripts? (Figure 2c)

6. Findings: Towards Restoring the Children’s Album Authenticity

- The documented author’s approval of the first published edition could not hide all the metaphors that we can discover from the preserved original manuscript, its thematic and structural coherence, and the complexity of interpreting Tchaikovsky’s editorial decisions.

- The original version helps us understand the Children’s Album as an integral inseparable larger scale composition rather than a collection of 24 independent pieces. The compositions are semantically and musically linked to appear as several untitled parts of the whole.

- The Children’s Album can be appreciated by young piano players and their audiences, but they are far from appealing for children only. To truly appreciate the whole construction, its mental appeal, the pictures portrayed, metaphors expressed, one requires both historical and musical background, as well mental maturity, aesthetic sensitivity, and education of an adult.

- The pedagogical value is obvious; however, the purpose of advancing piano playing skills is definitely not the main composer’s motivation.

- The apparent imitation of Schumann’s style must be called in question, yet this does not diminish Tchaikovsky’s profound respect for Schumann’s legacy.

6.1. Sequencing: Unraveling Dramatic Transformations

6.2. Influence: Just a Hint of Schumann

`To suggest that he somehow wished to emulate these models and couldn’t is demeaning and unsupportable in the face of his manifest ingenuity. This does not mean that inspiration never faltered […] but simply that giving him some credit for autonomy and individual approaches to composition will rectify the tendency, over the decades, to reject his music as unassimilated—not quite up to standard—eccentric, and too personal”.(Wiley 2009, p. xx)

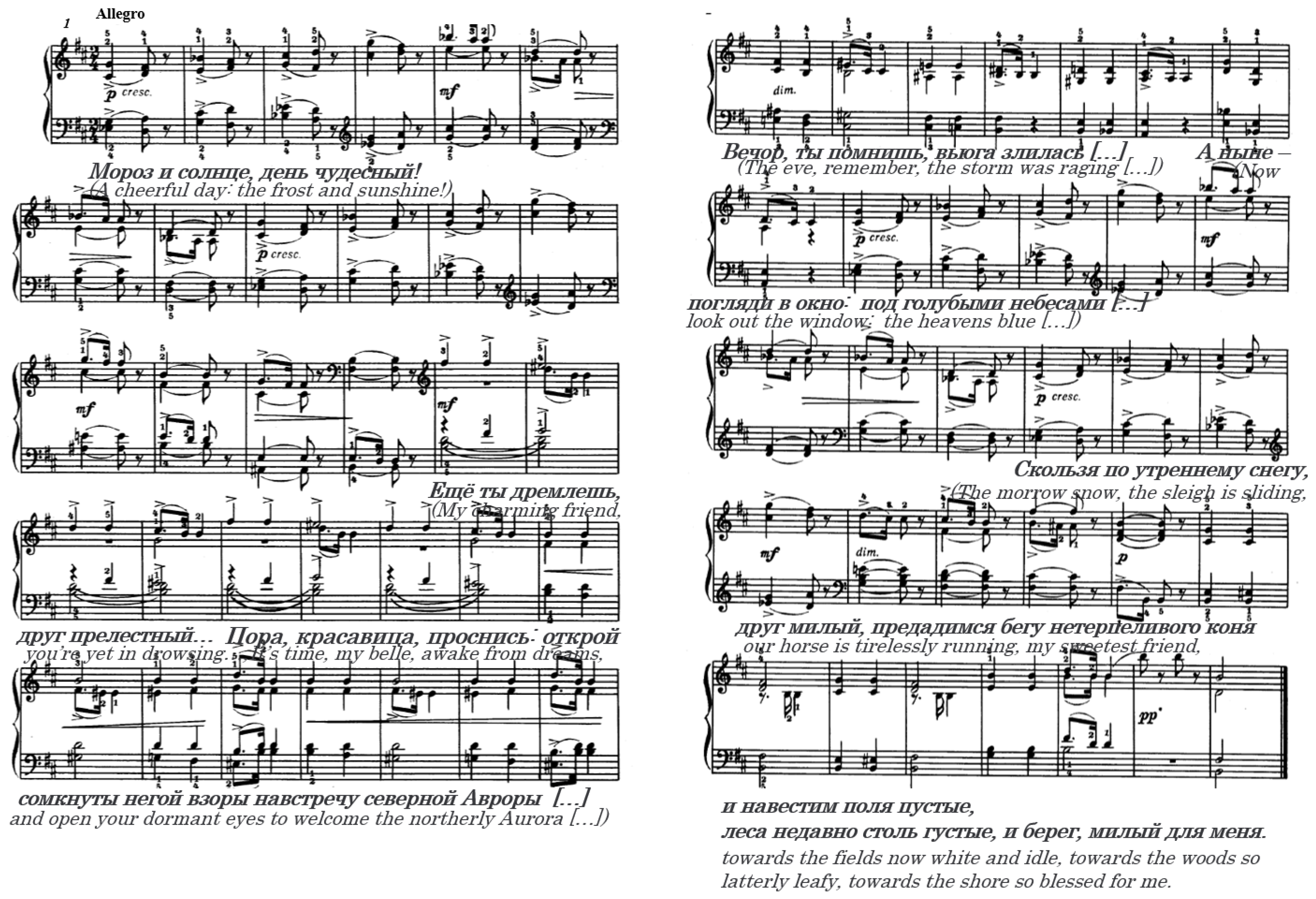

6.3. Metaphors and Allusions: Pushkin, Mozart, Natasha Rostova, and More

Never in the whole course of my life did I feel so flattered, never so proud of my creative power, as when Leo Tolstoy, sitting by my side, listened to my Andante [Andante Cantabile from the First String Quartet, Op. 11] while the tears streamed down his face.

One evening Anatol and I suddenly heard someone singing in the street, and saw a crowd in which we joined. The singer was a boy about ten or eleven, who accompanied himself on a guitar. He sang in a wonderfully rich, full voice, with such warmth and finish as one rarely hears, even among accomplished artists. The intensely tragic words of the song had a strange charm coming from these childish lips. The singer, like all Italians, showed an extraordinary feeling for rhythm. This characteristic of the Italians interests me very much, because it is directly contrary to our folksongs as sung by the people

7. Discussion

7.1. Possibilities for Research on Emotional Response

7.2. Pedagogical Implications

7.3. Cross-Disciplinary, Cross-Genre, and Cross-Technology Implications

7.4. Appeal to Modern Sensibilities

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allegraud, Pierre, Louis Bigo, Laurent Feisthauer, Mathieu Giraud, Richard Groult, Emmanuel Leguy, and Florence Levé. 2019. Learning sonata form structure on mozart’s string quartets. Transactions of the International Society for Music Information Retrieval (TISMIR) 2: 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Cameron J., and Michael Schutz. 2023. Understanding feature importance in musical works: Unpacking predictive contributions to cluster analyses. Music & Science 6: 20592043231216257. [Google Scholar]

- Appel, Bernhard R. 2014. Actually, taken directly from family life: Robert Schumann’s Album für die Jugend. In Schumann and His World. Edited by Larry R. Todd. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 171–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayzenshtadt, Sergei. 2003. “Detskiy albom” Tchaikovskogo. Metodicheskiye Kommentarii (Tchaikovsky’s Children’s Album. Methodical Comments). Sochi: Klassika-XXI. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Bokiniec, Monika. 2009. Mieczysław wallis: Experience and value. Estetika: The European Journal of Aesthetics 46: 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, Philip Ross. 2016. Pyotr Tchaikovsky. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, David. 1991. Computers and Musical Style. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, Michael William. 1965. Vladimir Stasov and the Development of Russian National Art: 1850–1906. Madison: The University of Wisconsin-Madison. [Google Scholar]

- Čajkovskij, Petr Il’ic. 2001. Complete Works, New Edition. Edited by Thomas Kohlhase. Moscow and Mainz: Muzyka, Schott, vol. 69b. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, John. 1969. How We Think. Lexington: D.C. Heath. [Google Scholar]

- Dotsey, Calvin. 2019. The Birth of Russian Music: Glinka’s Kamarinskaya. Available online: https://houstonsymphony.org/glinka-kamarinskaya (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Dotsey, Calvin. 2024. Strange and manifold music. In Swan Lake, The Royal Ballet Programme. London: Royal Opera House, pp. 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Eisner, Elliot. 1993. Objectivity in educational. In Educational Research: Volume One: Current Issues. London: SAGE, vol. 1, pp. 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Emmet, Dorothy. 1994. The Role of the Unrealisable: A Study in Regulative Ideals. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Fish, Stanley. 1982. Is There a Text in This Class? The Authority of Interpretive Communities. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fons, Margaret Ann. 2012. “A Thousand Nuances of Movement": The Intersection of Gesture, Narrative, and Temporality in Selected Mazurkas of Chopin. Austin: The University of Texas. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Patricia Marie. 1977. The Pedagogical Concepts of Carl Czerny: An Analytical Study. Cincinnati: University of Cincinnati. [Google Scholar]

- Himonides, Evangelos. 2016. Big data and the future of education: A primer. In Music, Technology, and Education. London: Routledge, pp. 243–56. [Google Scholar]

- Juslin, Patrik N. 2019. Musical Emotions Explained: Unlocking the Secrets of Musical Affect. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kandinskiy-Rybnikov, Alexey A., and Marina G. Mesropova. 1990. Vremena goda i Detskiy albom Tchaikovskogo: Tsyklichnost i problemy ispolneniya (Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons and Children’s Album: Cyclicity and performing problems). In Tchaikovsky: Voprosy Istorii, Teorii i Ispolnitelstva (Tchaikovsky. Questions on History, Theory, and Performing). Moscow: Moscow Conservatory, pp. 120–37. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kandinskiy-Rybnikov, Alexey A., and Marina G. Mesropova. 1997. One opublikovannoy P.I. Tchaikovskim pervoy redaktsii “Detskogo alboma” (On an unpublished first edition of the “Children’s album” by P.I. Tchaikovsky). In Voprosy Muzykalnoy Pedagogiki (Issues of Musical Pedagogy). Moscow: Muzyka, pp. 138–61. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Keshuang, Liu. 2023. “Children’s Album” by P. I. Tchaikovsky and Its Musical Context. Humanities & Science University Journal 76: 110–16. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Landrum, Michael McRee. 1997. Tchaikovsky’s "The Seasons": Analytical and Pedagogical Perspectives. Philadelphia: Temple University. [Google Scholar]

- Lather, Patricia. 2010. Engaging Science Policy: From the Side of the Messy. Lausanne: Peter Lang, vol. 345. [Google Scholar]

- Lazanchina, A. 2015. Fenomen detstva v fortepiannykh tsiklakh R. Shumana i P. Tchaikovskogo (The phenomenon of childhood in piano cycles by R. Schumann and P. Tchaikovsky). In Transactions of Russian Academy of Science Samara Research Center. Moscow: RAS, pp. 1224–27. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Xuanyi. 2023. Towards a Novel Approach for Real-Time Psycho-Physiological and Emotional Response Measurement: Findings from a Small-Scale Empirical Study on Sad Erhu Music. Ph.D. thesis, UCL (University College London), London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Maeder, Costantino, and Mark Reybrouck. 2015. Music, Analysis, Experience: New Perspectives in Musical Semiotics. Leuven: Leuven University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maes, Francis. 2024. Tchaikovsky, onegin, and the art of characterization. Arts 13: 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekhaeva, Iraida. 2018. The modern measurement of Tchaikovsky (Definition experience of the “modernity” concept on example of the “Children’s Album” by PI Tchaikovsky). Tomsk State University Journal of Cultural Studies and Art History 30: 146–47. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Saebyul, Eunjin Choi, Jeounghoon Kim, and Juhan Nam. 2024. Mel2word: A text-based melody representation for symbolic music analysis. Music & Science 7: 20592043231216254. [Google Scholar]

- Peshkin, Alan. 1988. In search of subjectivity—One’s own. Educational Researcher 17: 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Prokofiev, Sergei. 1936. Interview to Gazeta Polska. Signed H.L., March 7. In Prokofiev o Prokofieve (Prokofiev on Prokofiev: Articles and Interview). Edited by Viktor P. Varunts. Moscow: Sovetsky Kompozitor, 1991, pp. 135–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pyshkin, Evgeny. 2022. (Un)like Schumann: Applying Cope’s music signature pattern matching algorithms to Tchaikovsky’s Children’s Album. Paper presented at the 16th International Conference on Advanced Engineering Computing and Applications in Sciences ADVCOMP 2026, IARIA, Lisbon, Portugal, September 28–October 2; pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pyshkin, Evgeny, and John Blake. 2024. Dispelling the seven myths of tchaikovsky’s children’s album through computational and language modeling. Paper presented at the Sempre MET2024 International Conference on Music-Education-Technology, SEMPRE, London, UK, June 14–15; pp. 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pyshkin, Evgeny, and John Blake. 2025. “Lost in Translation”? Challenges in conveying the original titles of Tchaikovsky’s Children’s Album. Terra Linguistica 16: 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Sapir, Edward. 1929. The status of linguistics as a science. Language 5: 207–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavio, Andrea, Nikki Moran, Mihailo Antović, and Dylan van der Schyff. 2022. Grounding creativity in music perception? a multidisciplinary conceptual analysis. Music & Science 5: 20592043221122949. [Google Scholar]

- Schumann, Robert. 1848. 43 Piano Pieces for the Youth. Op 68 (Orig. Title in German: 43 Clavierstücke für die Jugend). Hamburg: Schuberth and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Zhengshan. 2021. Computational Analysis and Modeling of Expressive Timing in Chopin’s Mazurkas. Montréal: ISMIR, pp. 650–56. [Google Scholar]

- Tchaikovsky, Modeste. 2018. The Life & Letters of Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky. Frankfurt am Main: Outlook Verlag GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich. 1878a. Children’s Album, Op 39. Lausanne: Jurgenson Peter. [Google Scholar]

- Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich. 1878b. Letter to Nadezhda von Meck from Kamenka. Available online: http://en.tchaikovsky-research.net/pages/Letter_820 (accessed on 23 April 2025). (In Russian).

- Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich. 1948. Complete Works, Vol. 52: Piano Works. Edited by Nikolai Drozdov. Leningrad: Muzyka. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich. 1993. Children’s Album for Piano. Facsimile. Moscow and Vienna: Minex. [Google Scholar]

- Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich. 2015. Tchaikovsky: Otkrytyi Mir. Detskiy Albom (Tchaikovsky: Open World. Children’s Album. Available online: https://www.culture.ru/catalog/tchaikovsky/ru/item/archiv/detskiy-albom-24-legkih-pesy (accessed on 23 April 2025). (In Russian).

- Thomas, Mathew, Mintu Jothish, Navin Thomas, Shashidhar G. Koolagudi, and Y. V. Srinivasa Murthy. 2016. Detection of similarity in music files using signal level analysis. Paper presented at the 2016 IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON), Singapore, November 22–25; pp. 1650–54. [Google Scholar]

- Tolstoy, Leo. 1869. War and Peace. Translated by Rosemary Edmonds. Harmondsworth: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszewski, Mieczysław. 2000. Nad analizą i interpretacją dzieła muzycznego. In Myśli i Doświadczenia. w: Interpretacja Integralna dzieła Muzycznego. Rekonesans. Kraków: Akademia Muzyczna, pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszewski, Mieczyslaw. 2015. Reading a work of music from the perspective of integral interpretation. New Perspectives in Musical Semiotics 61: 356. [Google Scholar]

- Whorf, Benjamin Lee. 1940. Science and linguistics. Technology Review 42: 229–31 & 247–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wiley, Roland John. 2009. Tchaikovsky. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

| Micro-Cycles * | Orig. No. | Jurg. No. | Compositions ** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morning/Birth | 1 | 1 | Morning Prayer |

| 2 | 2 | Winter Morning | |

| 3 | 4 | Mama | |

| The games boys play | 4 | 3 | Toy Horse Play |

| 5 | 5 | March of the Wooden Soldiers | |

| The games girls play | 6 | 9 | A New Doll |

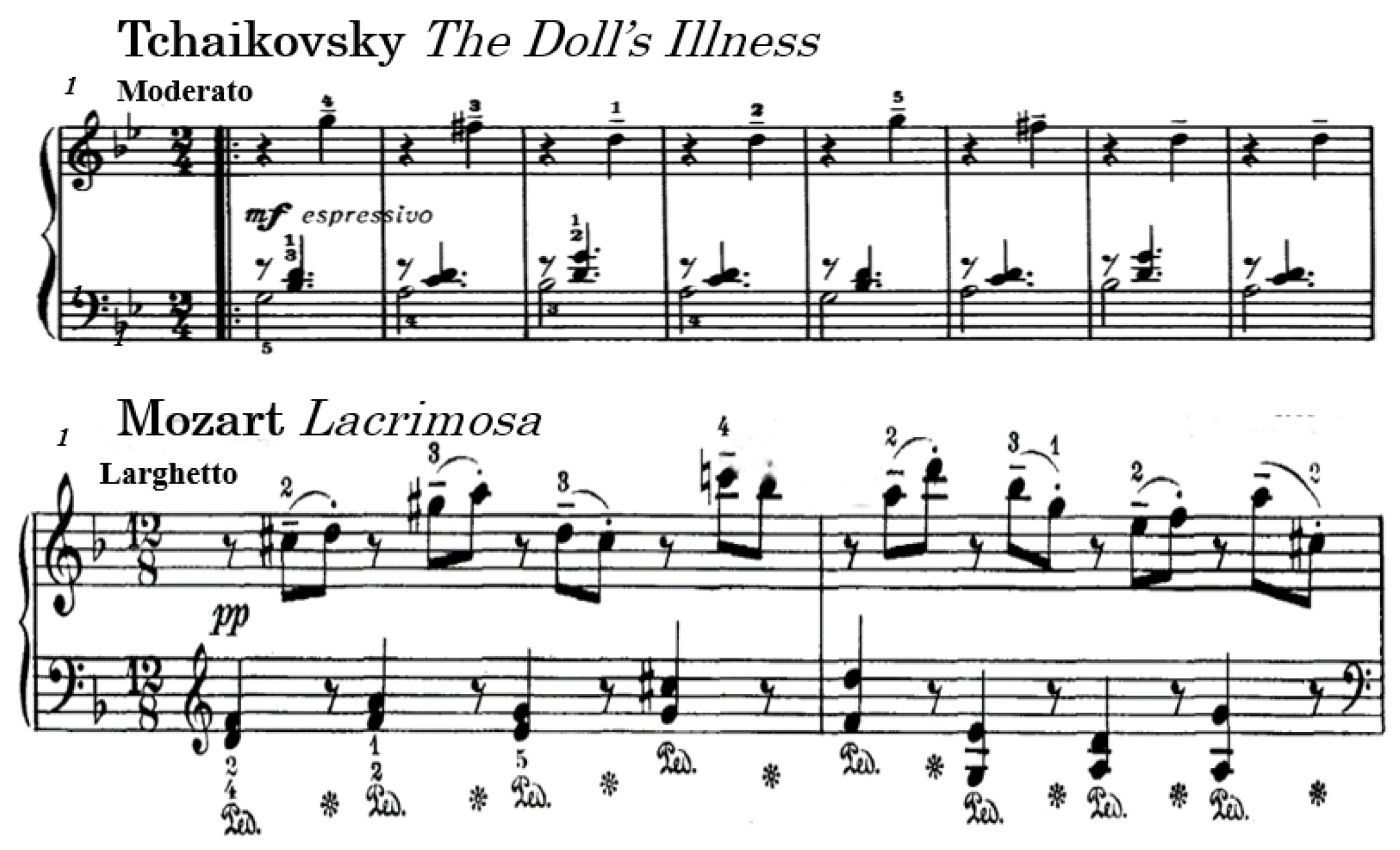

| 7 | 6 | The Doll’s Illness | |

| 8 | 7 | The Doll’s Funeral | |

| Pair and ball dances | 9 | 8 | Waltz |

| 10 | 14 | Polka | |

| 11 | 10 | Mazurka | |

| Motherland (folk traditions) | 12 | 11 | Russian Song |

| 13 | 12 | Muzhik Playing Harmonica | |

| 14 | 13 | Kamarinskaya | |

| Traveling/Learning | 15 | 15 | Italian Song |

| 16 | 16 | Old-French Song | |

| 17 | 17 | German Song | |

| 18 | 18 | Neapolitan Song | |

| Tales/Memories/Children | 19 | 19 | Nanny’s Tale |

| 20 | 20 | Baba-Yaga | |

| 21 | 21 | Sweet Dream | |

| 22 | 22 | Lark’s Song | |

| End of the day/Rebirth | 23 | 24 | In Church |

| 24 | 23 | Organ-Grinder Singing |

| Pattern Match * | Topical Match * | Schumann, Op. 68 | Tchaikovsky, Op. 39 | Other Interesting Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✓ | Choral | Morning Prayer | ||

| ✓? | Roaming in the Morning | Winter Morning | ||

| ✓ | Winter Morning | Pushkin’s eponymous poem | ||

| ✓ | Melody | Mama | ||

| ✓ | Humming Song | Mama | ||

| ✓ | Soldier | March of the Wooden Soldiers | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | Choral | In Church | |

| ✓ | The Wild Rider | Toy Horse Play | ||

| ✓ | Toy Horse Play | Vivaldi’s Sicilienne | ||

| ✓ | First Loss | The Doll’s Illness | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | The Doll’s Illness | Mozart’s Lacrimosa from Requiem | |

| ✓? | Mazurka | Tchaikovsky’s Un poco di Chopin | ||

| ✓ | ✓? | Little Song in Canon Form | Old-French Song | |

| ✓ | The Reaper’s Song | Italian Song | ||

| ✓ | Echoes from the Theater | Waltz | ||

| ✓ | Waltz | Tolstoy’s War and Piece | ||

| ✓ | Sheherazade | Sweet Dream | ||

| ✓ | In Memoriam | Sweet Dream | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | Organ-Grinder Singing | Tchaikovsky’s Reverie interrompue |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pyshkin, E.; Blake, J. Restoring Authenticity: Literary, Linguistic, and Computational Study of the Manuscripts of Tchaikovsky’s Children’s Album. Arts 2025, 14, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030049

Pyshkin E, Blake J. Restoring Authenticity: Literary, Linguistic, and Computational Study of the Manuscripts of Tchaikovsky’s Children’s Album. Arts. 2025; 14(3):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030049

Chicago/Turabian StylePyshkin, Evgeny, and John Blake. 2025. "Restoring Authenticity: Literary, Linguistic, and Computational Study of the Manuscripts of Tchaikovsky’s Children’s Album" Arts 14, no. 3: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030049

APA StylePyshkin, E., & Blake, J. (2025). Restoring Authenticity: Literary, Linguistic, and Computational Study of the Manuscripts of Tchaikovsky’s Children’s Album. Arts, 14(3), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030049