Abstract

It has always been understood that Pablo Picasso imbued his arts with a rich symbolism. Those representations could be understood readily, at times only with some effort, or utterly inaccessible at others. A part of that symbolism is yet to be understood, with numerous points of information and cross-reference “hiding” in plain sight. He was fond of newsprint as a substrate and medium for painting, not only during wartime, but especially so in the deprivations of World War II. The relationship between some paintings typical during the period and the newsprint on which they were done was intense, such that the substrate inhabits the medium, sharing equal part with the composition. Around the same time or after, Picasso was crafting poems of an often cryptic nature. An in-depth look at two poems reveals a multitude of references to paintings on newsprint and to the contents of that newsprint. With new understandings of those symbols, evidence emerges that Picasso’s “palette of words” was more than just metaphor, but also descriptive of a theory and a method which the artist put into practice in at least two instances of WWII-era newsprint paintings and famously cryptic poems, detailed here.

1. Introduction

Picasso wrote dozens of cryptic poems in the 1930s and 40s, many of them in Spanish or mixed languages, but mostly in French. Anne Baldassari identifies “Maxima: au sol” as one “coded poem” which Picasso had labeled and dated, documenting Le Journal 8.12.35 as the source for a portion of its content (Baldassari 2000, pp. 122–25). In the poem, he imitates fonts and cases and makes verbatim use of the newsprint text. Not only were these poems heavily coded, but some of them may seem little more than cleverly worded codes. Emilie Sitzia demystifies Picasso’s writings noting their cubist nature in her recent paper:

It now seems that there is much more happening than perhaps originally thought.Just as Picasso’s painting deconstructs the image to achieve evocation through fragmentation, Picasso deconstructs the syntax of his text. This is partly what creates a loss of narrative and the disappearance of clear subject matter in his poems. His writing, focusing on rhythm, evokes Picasso’s visual work on non-linear compositions that shatter the image, offering no single-point perspective.(Sitzia 2021)

Baldassari dedicated an entire book to the theme of Picasso’s long relationship to the newsprint medium. Of his collages and mixed media on newsprint works, she says the following:

This describes for us the mind, and pieces of the mechanism he employed in producing the works examined here.The textual montage of these writings likewise follows the spiral trajectory of the reader’s gaze, but also follows the rules of composition according to which the manuscript graphically fills up the page. Each of these pages is thus destined to be read out loud as well as looked upon as a drawing.(Baldassari 2000, p. 114)

Picasso said “When I began to write them I wanted to prepare myself a palette of words, as if I were dealing with colors. All these words were weighed, filtered and appraised. I don’t put much stock in spontaneous expressions of the unconscious” (Rothenberg and Joris 2004, pp. xv–xvi)1. If the palettes of words which he prepared were all weighed, filtered, and appraised as he said, then we might ask whether he weighed, filtered, and appraised those words himself, or whether it is possible that he came upon those words somewhere and prepared them for reuse. We explore the possibility that at least some of those words on his poet’s palette were not entirely composed but rather found, chosen directly from Le Journal, Paris Soir, and other newspapers in his possession (Flanner 1957; Krauss 1998; Todd [1964] 1999, p. 158)2. We have found that there are more instances of Picasso’s use of newsprint as a substantial source of content for paintings and poetry, maybe many more, and that Picasso had developed and used a method of deriving that content from the newspapers. There are other coded poems in addition to “Maxima: au sol” and here we identify their apparent source codes: each one a full page of painted French wartime newsprint.

In the two examples below, Picasso uses the method of “prepar[ing] a palette of words” from a full page or multiple pages of newsprint; incorporates certain events, images, people, and artifacts from both sides of the newspaper, transcribing them into the content and composition of his visual art and poems. In these cases, the painting is done directly on the newsprint itself, adding to it his life and commentary on the news on the paper on which it was written. “After all, the arts are one and the same. You can write a painting in words, just as you can paint feelings in a poem” (Penrose 1982). Exactly true to that assertion of universality, typical of Picasso’s reuse and re-working of themes and subjects, he paints a newspaper and writes a poem to describe it, or writes a poem to describe a painting he may have already planned. Gertrude Stein seemed to argue whether some of his poems were really even poems and was suspected of raw jealousy over his intrusion into her literary realm (Meyers 2006). It might also be argued that Picasso was not “flattered” into thinking that because of his fame, he could also write poetry, at least in these cases, but that he was exploring transactions between art forms along their cubist intersections. In the Palette of Words method, Picasso finds confirmation of the theory with a dual use of the content, readily available in the news of the day, already in well-edited form for him to consume, reduce, pick, choose, and re-form into his own. If we could ask Picasso about his methods or intentions in this matter today, we might expect him to reject the notion that the works comprise a pair, but that the poem, the painting, and the newsprint are just parts of the same work and concept.

Others have said of Picasso’s artistic, poetic style:

Picasso was of course known to use props: a napkin, a postcard, a bicycle seat, items extracted from trash heaps, and others, as vehicles for amusement and showcases of his own ingenuity (Penrose [1958] 1981, p. 291; Todd [1964] 1999, pp. 98–101). In the case of wartime newsprint, he occasionally uses the textual items as-is, verbatim and so far as even to reuse the fonts and styles (Baldassari 2000, pp. 122–25). More often though, he chooses to bend the sounds around words or their semantic images for his purposes.…Picasso’s relationship with poetic writing, the way it came into being, the thematic correspondences between his texts and paintings, and the extraordinary inventiveness with which he shaped this verbal substance [are] as free as his other forms of expression”.(Musée National Picasso-Paris 2021)

Picasso himself was quoted “Long after his death, his writing would gain recognition and encyclopedias would say: ‘Picasso, Pablo Ruiz–Spanish poet who dabbled in painting, drawing and sculpture’” (Acoca 1971) quoted in Rothenberg and Joris (2004). We believe him when he says this on his ninetieth birthday, that Picasso was not merely waxing sarcastic. More concrete meanings can be found to exemplify those words, if one knows where to look. We consider here whether he may have developed and employed this method for a time, leaving clues of his genius to be recognized later with the intention that this particular method be discovered after some years.

2. Materials and Methods

We can no longer think of that “palette of words” that Picasso mentioned as mere metaphor. For Pablo Picasso, the painting often started not with his thumb through a wooden palette, but with him unfolding a newspaper as a kind of rag to spread on the table or floor. We notice that a newspaper, other than paper, is comprised largely of words. Picasso read the printed words and saw the graphics before mixing his oil paints. The power which those words hold in times of war is of increased interest to those in possession of the means to force action or inaction through fear, extreme discomfort, and of course death. Prior to the invasion in June 1940, Paris Soir had been routinely a 12- or 16-page paper. It was reduced to a 4-page rag after the onset of the Occupation.

Picasso addressed his attitude toward commentary on the Occupation and the war generally, saying,

Picasso’s art necessarily changed under the influence of the war because, demonstrably, his life was at stake. Those who endured the Occupation, particularly those with the power of communication media such as newspapers and art, were under significant pressure. They chose to flee, were disbanded, became tools of the Occupation such as Paris Soir, or like Picasso were forced to demure. Picasso chose to stay in Paris where his art lived rather than fleeing to the relative safety of (e.g.,) the U.S.A., which he could easily have done (Popova 2025). He faced the trepidations of the Occupation along with his fellow Parisians, placed the calling card of the French Resistance “V” for victory throughout these paintings and poems, and appears to have increased his use of metals for sculpture at a time when the Nazis had embarked on campaigns of ravenous metal acquisitions to supply the manufacture of war materiel (Finn 2016; Popova 2025).I have not painted the war because I am not that kind of painter, the kind who goes, like a photographer, in search of the subject. But there is no doubt about the war existing in the pictures I did at the time. Later on, maybe, some historian will demonstrate that my painting changed under the influence of the war.(Whitney 1944)

We had the Paris Soir newspapers printed by a local printing company on A2-size paper, with the request to print it true to all the original dimensions. To see the words as the artist would have seen them on his palette, we folded and unfolded the newsprint, turned it upside down, and looked at it from both sides, just as a person using it as a rag might see. We compared the printed newspapers in hand with images of the paintings, and the poems. Now we examine the following two examples of three items each—a newspaper, a painting, and a poem—where Pablo Picasso has engaged what can be called his Palette of Words as his primary method of content generation. His commentary can be seen occurring visually (as in Picasso’s careful and deliberate orientation of the newsprint “canvas” and placement of brushstrokes so as to expose or conceal text and objects on the newsprint substrate) or in the poems (as in, e.g., “l’aurore boréale,” another coded poem with its list-like series of phrases and images). At times, these poems read like indexes to the items on the newsprint and their relationship to the visual content of the paintings done on them. The Palette of Words method becomes apparent when the full-page painted newspaper is viewed side-by-side with the code-poem.

The Palette of Words theory states that Picasso used the text, images, and other items present on a full page of newspaper as the primary resource for generating the content of a painting, and paired the work with a poem. Whether he did so with a subject or subjects already in mind and then sought items in the news to fit them, or whether he saw items in the news and related them to the subjects in his head is not important in the present discussion. It seems almost certain that both were true at times, that the process would go in either direction, inductively or deductively, and that plenty of evidence exists to show that he did both. It might be possible that the poem was written first, and then the newsprint was painted, or the other way around. The wartime paintings on newsprint are not dated by the artist and the dating of them is not definitive, other than post the date of the newspaper’s publication.

2.1. Example One

The painting Tête de femme/Moscou dans l’angoisse (Mallen 2024) featured prominently in the front matter of Picasso Working on Paper (Baldassari 2000, p. 2) and in The Picasso Celebration: the Collection in a New Light! exhibition (Musée National Picasso-Paris 2023). Please see Tête de femme, sometimes known as Moscou dans l’angoisse, done on page 3 of Paris Soir, 4 November 1941, https://cep.museepicassoparis.fr/explorer/tete-de-femme-mp1990-72, accessed on 16 February 2025 (Centre d’Études Picasso 2025)3.

It is easier to understand Tête de femme/Moscou dans l’angoisse when its subject is seen as Olga Khokhlova. The date of the newspaper, Paris Soir, is 4 November 1941 (Retro News 2024a); the painting was done sometime post-4 November 1941 (Mallen 2024). The form of the “folded fan” mentioned in the poem is also found in the hair of the painting on newsprint. A similar fan appeared first in his painting Portrait of Olga in an Armchair in 1918 (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2024) which we suppose the artist had not forgotten. The earlier Olga was meticulously planned, posed, photographed, sketched, and lovingly painted. Please see Portrait of Olga in an Armchair Portrait d’Olga dans un fauteuil c. 1918, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/656448, accessed on 16 February 2025 (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2024)4. Twenty-four or more years later, he paints her again but grotesquely with the fan on top of her head, a colorless caricature on newspaper. On his painting of her in 1918, there are some light brush strokes which have been interpreted as “a few searching strokes” by (e.g.,), The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2024) but which could also have been achieved with the intent of simulating scratches done by fingernails. Those finger-width strokes extend downward, in sets of four, from just below her right fingertips. One might easily imagine him calling her “Ongles” (fingernails) for its sound like “Olga” as a pet name. This analysis will suggest the likelihood that he did just that.5

We can begin to see why this particular newspaper was chosen for this composition of the Tête de femme and the poem “l’aurore boréale” (or alternatively how the chosen newspaper contributed and grew into the generative impetus for their contents). Olga studied ballet in St. Petersburg, not Moscow, but it is almost certain he would have heard from her about cold Russian winters and occasional auroras borealis. Just as Moscow is often used as the emblematic city of reference to the whole of Russia, it remains eminently plausible that, for Picasso, Moscow refers here to Russia, and moreover to his Russian wife. At the time of his writing, Olga, the estranged Russian wife, was quite likely feeling anguished, as well as being a source of anguish for the artist.

Pablo Picasso, “l’aurore boréale” 27 July 1947 (Mallen 2024)

Part 1:

l’ aurore boréale de l’ éventail fermé de sa crinière les ongles enfoncés dans les rideaux de suée des cris crispés auxfers de lance des troupeaux apeurés de lunes mordorées battant des ailes agenouillées autour des énormesamphores traînées par le blanc citron des draps souillés du bleu horizontal du couple orange des boeufsacidulant l’ or du jasmin des cadres ogivals des verres remplis de vin cachés sous les dents des dentellesenveloppant de ses bras en fontaines démangeaisons et jeux déployant des arabesques en haut des fanfaresdes drapeaux en arc-en-ciel codifiant si minutieusement l’ acier des morsures accidentelles des grappesguimauve et feston de miel agitant leurs pattes dans la mare et les puants regrets onctueusement pliés etrepassés sur le marbre accueillent et respectueusement saluent la lointaine acquisition et farandole d’ artificesecouée sur la cendre du potager.

Les enfants flambent arrachés de la chaux vive des feuilles de vif-argent qui grille au fond de la lame tordue ducouteau grattant la plaie.

la caressante laideur du papier semé de rose et d’ amarante continue son ronron à l’ heure

Part2:

II précise où l’ horloge se fane et fond sa cirelèvre à lèvre entre les plis du lac tendu sur lescordes épinglant la fenêtre à l’ ombre portéefaisant ses besoins justement au pied du gibetpeint en vert.

Et la manière si inattendue de lui présenter dols etcondoléances archipel innombrable perducorps et biens dissous dans la bonne soupeglacée frite à pied joint sur l’ écharpede regrets de tant de circonvolutions.

Mais physiquement parfaite.

27 juillet 47. Antibes

Decoding the poem ascribed the working title of “l’aurore boréale” dated 27 July, 1947 leads us to a few realizations about the Tête de femme/Moscou dans l’angoisse: “Les ongles” (the fingernails) in the opening line is almost surely the poet’s reference for its subject’s name. The layering and repetition of these meanings weaves well with other proximal phrases and descriptors. “…l’ éventail fermé de sa crinière” (the closed fan of the mane) describes the horse-like mane and simultaneously hinged, fan-like hair of the woman in the Téte de femme. Les yeux is commonly paired with “enfonces” to mean sunken eyes and “les ongles enfonces”, although it can be translated as “fingernails jammed”, almost certainly means Olga with her famously cupped, deep-set eyes. Picasso consistently rendered Olga with those distinct eyelids and orbitals. The Téte de femme/Moscou dans l’angoisse renders those same Olga’s eyes in gray, with bags and wrinkles. In fact, the only color other than black in the painting was the gray used under the subject’s eyes.

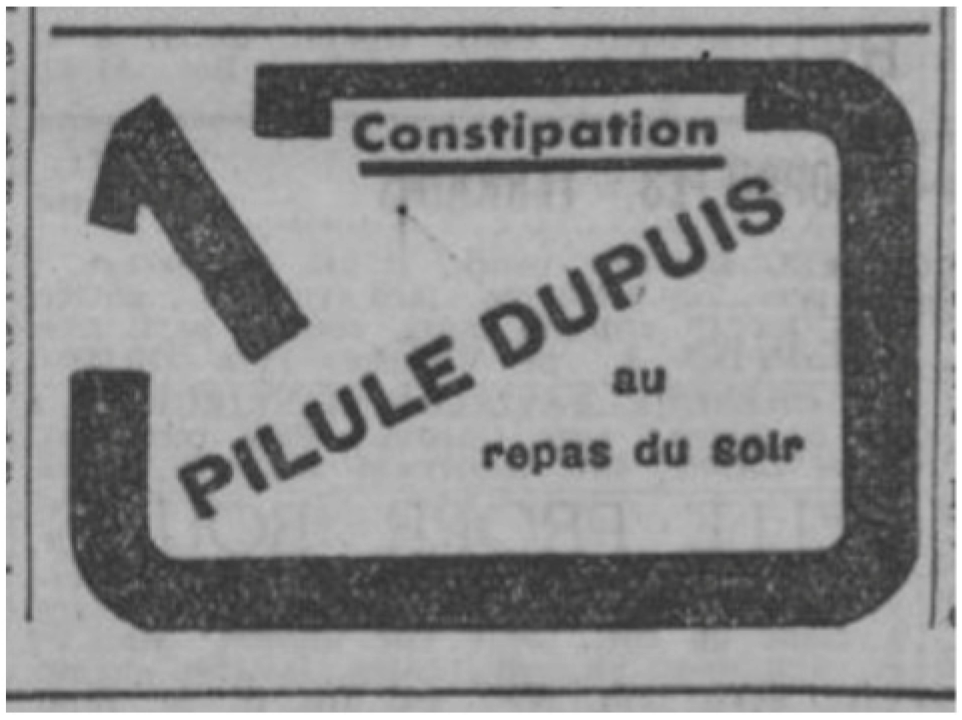

The eye and eyelid on the left of the painting are recessed into the bold outline of an ad for constipation medicine. Just as the ad presents a dark, squarish vortex in the original newspaper, the eye forms a sort of center point to the rest of the painting. “Enfonces” refers also to Olga’s spirit, the French translating alternatively as “sunken”, “jammed”, “pressed”, and “set”. It is hard for us to imagine Pablo Picasso, the “insatiable player of words” (Rothenberg and Joris 2004, p. 315)6 to miss out on the opportunity to rely on the proximity of “enfonces” to “s’enfoncer”, often used to mean “dig oneself in deeper”, such as into depression, which perhaps in the artist’s view she had done. “Les onlges enfonces dans les rideaux” could translate as “fingernails jammed into the curtains” (Rothenberg and Joris 2004, p. 262) but now seems much more likely as an evocation of Olga, the retired stage performer dug in deep behind the curtains. Instrumentally, the opposing page 2 of Paris Soir contains the headline: DERRIERE LE RIDEAUX. Turning Page 2, with its columns of advertisements from the theaters, the Olga image (on page 3) would be brought out from “behind the curtain”.

A number of additional clues, cues, and references in the poem tie it more tightly to the painting on the newspaper:

“L’aurore boréale” mentions cris crispés aux fers de lance (tense cries at the fers de lance). Fers de lance could mean the heads of a number of medieval weapons or it could mean a South American viper, or both. Interestingly, there was a popular murder mystery novel by the name of Fer de Lance (the snake) by Rex Stout in 1934 with a cover that featured foremost the image of an orchid (Stout 1934). In the Tête de femme/Moscou dans l’angoisse, the left side of the female subject’s hair in the painting forms a snake head terminating on the exact location of the notice for a flower show, with the image of a large blossom (Figure 1). Not coincidentally, we proffer, that page three of the newspaper on which we find this painting is the continuation of the story of the real-life murder mystery of Georges Girard, a celebrated case of the day (Retro News 2024a)7. The murders were carried out with a garden tool or weapon called a serpe, a type of billhook, and a close approximation or type of a fer de lance. We have more to say about the novel, the weapon, the snake, and the Girard murders below in the Discussion.

Figure 1.

The top, right column on Paris Soir 4 November 1941 is headed by an ad for a flower show and competition and features the image of an iris in bloom. It is also adjacent to the story of the murder mystery where the word “serpe” appears directly adjacent to the flower (Retro News 2024a).

Starting at the snake’s head and following up the side of the rendered figure’s face, one finds the partially obscured word CHARBON in the headline of a story which discusses a shortage of coal for most citizens that winter. One may recall the unsourced anecdote of Picasso refusing any favoritism from the Germans, to the effect that ‘a Spaniard is never cold’. Traveling up along that side of the face is a snout, understood to be one modeled on that of Picasso’s Afghan hound and appearing in numerous other works around this time (Penrose [1958] 1981, p. 310). Right on the nose we find the headline “Enfants débilités”, echoed “enfants flambent” in “l’aurore boréale”. The content of the soft news item centers on giving advice to mothers for raising healthy children, notably the use of a chalk as a dietary supplement. The presence of “charbon” and numerous other references to children’s health and burning coal (or to a lack of coal to burn) in the painting and in the poem forms a commentary on the difficulties of child-rearing and childhood under the Occupation. Just to the side almost brushing the nose indeed we find reference to “la charbonaire”, a coal burner (“grille” in the poem) and a few lines below “Enfants débilités”, “de la chaux”, which is repeated “…de la chaux” add “vive…” in “l’aurore boréale”. It could not escape notice that “vive” is common in phrases such as “Vive la Résistance!”.

Other meanings for chalk were not far. The “Cult of V” was said to have crossed the English Channel in the summer of 1941 (Ousby 2000)8, manifesting in any number of acts of defiance to the Occupation, among which even children used chalk to graffiti the symbol of victory on sidewalks, walls, military vehicles, streets and wherever they could, as their contribution to the French Resistance (Ousby 2000). It is easy to understand how any artist would take special notice of people carrying chalk through the streets for the purpose of self-expression, in this case as a form of popular resistance. (Mallen 2021, p. 160) notices how Picasso joined in, deliberately placing the figure’s mouth of the “Tête Visage” in the shape of a “V”; an arrow pointing to the very word RÉSISTANCES in another painting done on Paris Soir, 11 September 1941. Picasso as an apparent supporter/sympathizer of the French Resistance and Cult of V sought out “V” shapes and references in his wartime art, and in this example. “L’aurore boréale” references “vif-argent” (mercury), an anagram for “Vilmorin-Andrieux”, an advertisement for potatoes low in the same column as the flower blossom, the headline about coal, as well as references to coal burners, “Enfants débilités”, and “de la chaux”.

The post-war date of the poem “l’aurore boréale” indicates Picasso was reflecting back on those years, his troubles with Olga, their adult child Paulo’s committal in the same facility with Olga, his oppressed feelings during the war and Occupation and revulsion for Nazi atrocities. Although the poem was written after such time as Nazi war atrocities had become well known, in the case of the painting, we know of no definitive reason to say whether it pre-dates or post-dates the arrival of that information (Buncombe 2017). Even if it had been completed as early as 1942 (or at any rate prior to the knowledge of the atrocities, cattle cars, and uses of caustic limestone), the painting is already arranged into a biting commentary on the specter of sick and feverish children deprived of heat and proper nutrition in the coming winter of wartime. Picasso’s baby sister Conchita died of diphtheria at the age of 7 in a process of events that forever traumatized the young artist. As the story goes, Picasso tried to make a deal with God to spare his sister. If she could only live through her feverish illness, then he would swear off painting… (Huffington 1988).

In the post-war context of the poem, of course, “les enfants flambent arrachés de la chaux” (flaming children torn/snatched from the lime) forms a breathtaking remark on the Germans’ treatment of their perceived enemies. This portion of the poem “Les enfants flambent arrachés de la chaux vive des feuilles de vif-argent qui grille au fond de la lame tordue du couteau grattant la plaie” makes less sense in English: “The children blaze torn from the quicklime of the leaves of quicksilver that grilles at the bottom of the twisted blade of the knife scratching the wound” (Rothenberg and Joris 2004, p. 262), but maybe makes more sense as the poetic interpretation of this column of newsprint, starting from the “bent” or “crooked” blade in the top story, CHARBON and la charbonaire, enfants débilités, de la chaux and finally the advertisement for potato seeds, Vilmorin-Andrieux.

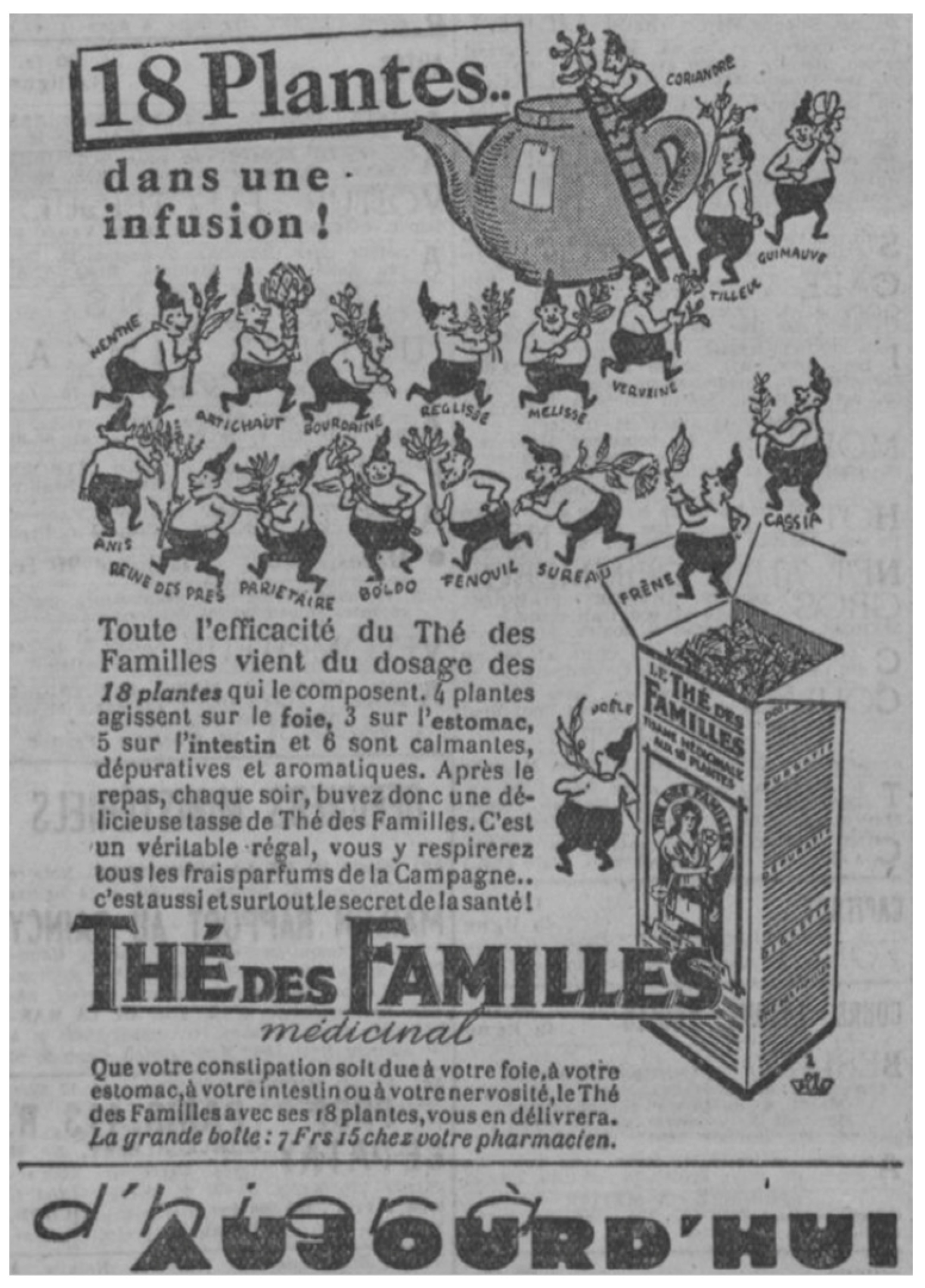

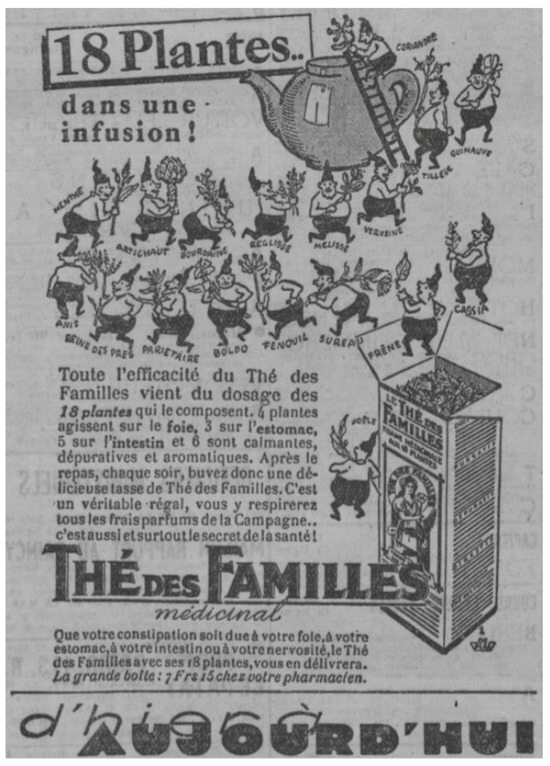

The “la lointaine acquisition et farandole d’ artifice secouée sur la cendre du potager” (the faraway acquisition and farandole of artifice shaken out over the cinders of the kitchen garden) (Rothenberg and Joris 2004, p. 262) mentioned in the poem is plainly seen in an advertisement of Thé Des Familles Médicinal (Figure 2). In it, a serpentine line is danced by 18 elves, each carrying its own specific herb through a garden. The last elf carries the herb guimauve, or marshmallow, also mentioned in the poem just a few words prior. While the same advertisement also regularly appeared in other newspapers, it cannot be excluded from relevance here. Additional indexing seems to appear just below the elves’ farandole under the AUJOURD’HUI headline, offering rentals in the suburbs, “Banlieue”. La Lointaine means the distant, far off, or remote (possibly implying uncared-for or neglected), i.e., suburbs.

Figure 2.

An advertisement on the Paris Soir substrate of Tête de femme/Moscou dans l’angoisse, Paris Soir 4 November 1941, p. 3 (Retro News 2024a). A line of 18 elves, dancing, including one holding guimauve, a word which appears almost inexplicably in the poem “l’aurore boréale” of 24 July 1947.

On the verso, page 4 of most editions of the Occupation era Paris Soir including this one, a horizontal line running the full breadth of the newspaper gives space to the section “les petites annonces couplées” (classified ads). Quite naturally, the word “horizontalment” also appears twice in the crossword puzzle resting on that horizontal line. “L’aurore boréale” mentions “horizontal du couple”. By itself, it may be a dubious claim, but there is a pronounced horizontal there, and personal ads and announcements are always very popular if not the most-read section of any newspaper. “A major reason for young Frenchmen to become résistans was resentment of collaboration horizontal, the euphemistic term of sexual relationships between German men and Frenchwomen” (Crowdy 2007). Also adjacent and above the newsprint horizontal, we find the advertisement for Maux de Dents and its image of a tooth. “L’aurore boréale” says there are things hidden under the teeth, glasses full of wine in ogival frames, “des cadres ogivals des verres remplis de vin cachés sous les dents” which then certainly do appear in the composition “under” the teeth on page 4.

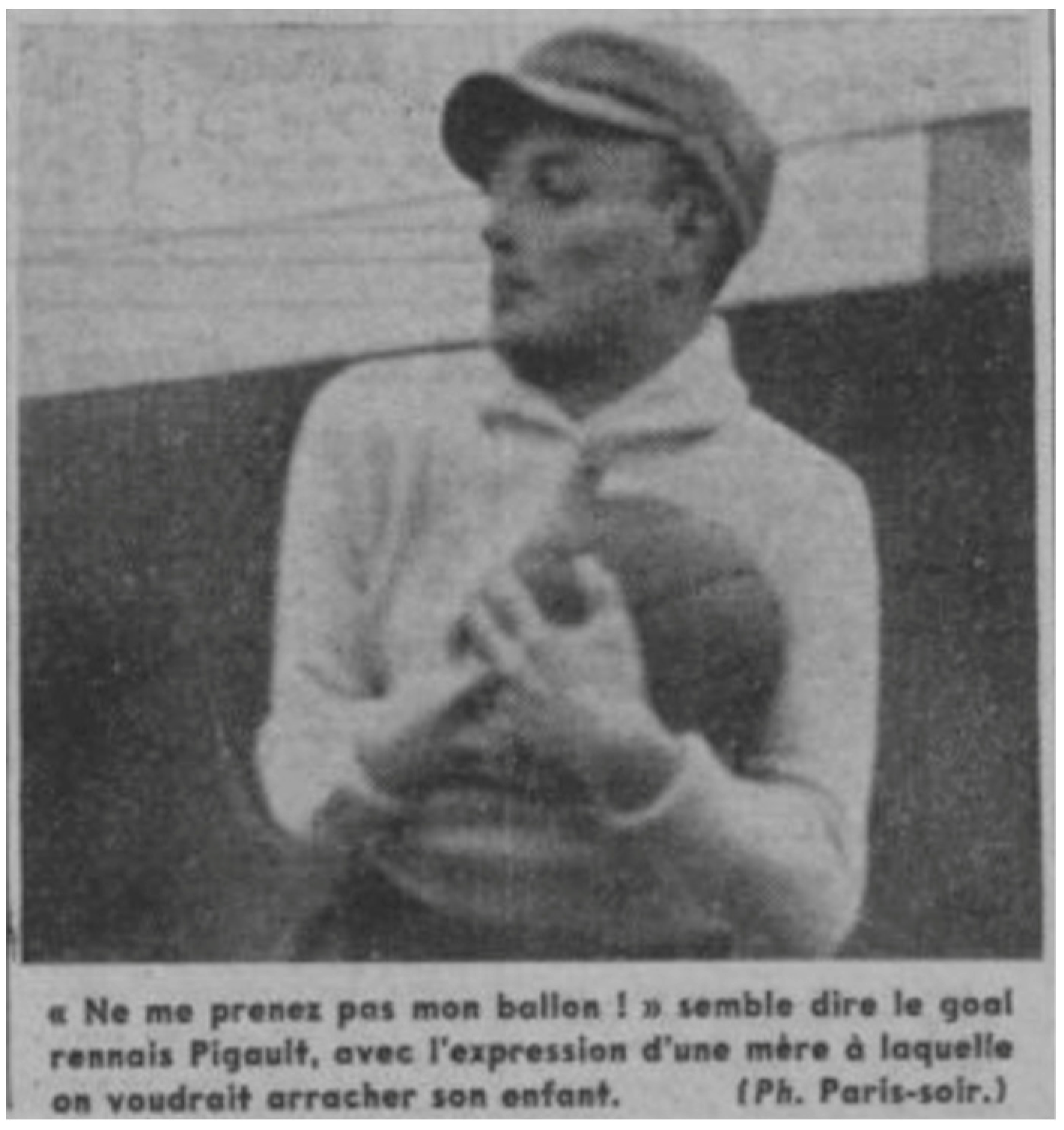

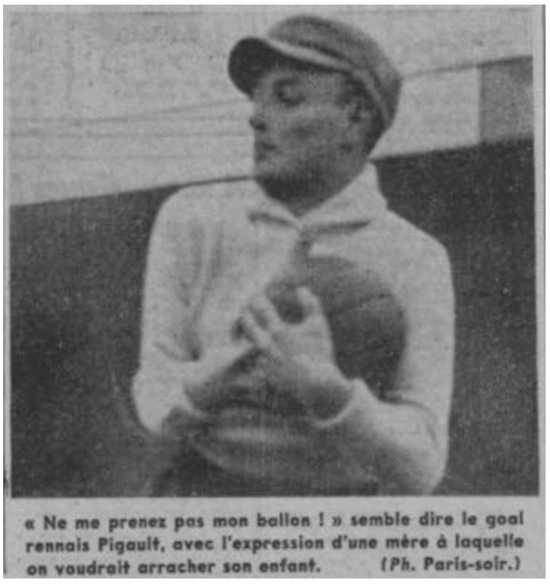

In the middle of Part 1: “l’aurore boréale” reads “enveloppant de ses bras” (enveloping in his arms). Above the fold, above the horizontal, page 4 contains sports news, most notably a photo of a rugby player (Figure 3) which can only be described as embracing or enveloping a ball in his arms. The caption below him reads exactly that, adding that he looks like a mother in fear of her baby being torn away from her “…arracher son enfant” also echoed “les enfants flambant arrachés de la chaux vive” in “l’aurore boréale”.

Figure 3.

A rugby player enveloping in his arms a very precious thing on Paris Soir, 4 November 1941, p. 4 (Retro News 2024a). The last three words of the caption under the rugby player read “arracher son enfant”.

The poem continues “…et jeux déployant des arabesques en haut des fanfares des drapeaux en arc-en-ciel…” (and games deploying their arabesques above fanfares and rainbow flags), which could describe the Reveille, bugle calls and pageantry common to the very events described at such lengths in any sports section. Next to the photo of the rugby player enveloping his ball is an illustration of an athlete in arabesque (Figure 4), below which mentions the énormes amphores trainees (DeepL 2024)9 in the form of the Rugby Cup of France. On the painted page 3, within an area bounded by the three items on the verso, in reference to the Cup of France (an amphore), the character in arabesque, and the rugby player in ecstasy, we find the very word “arc-en-ciel” (rainbow). Arc-en-ciel may not be the single most uncommon of all possible words to find in a newspaper, and yet there it is under three other visual references mentioned in the poem. Picasso is having a field day with this sports page.

Figure 4.

A football graphic depicts an athlete en arabesque from the sports section of Paris Soir, 4 November 1941, p. 4 (Retro News 2024a).

Typical of Picasso’s poems and as with “Les enfants flambant…” above, discernible breaks in the free verse appear by way of occasional full-stops and line spaces. A separate line states la caressante laideur du papier semé de rose et d’ amarante continue son ronron à l’ heure (the caressing ugliness of the paper sown with rose and amaranth continues its purring at the hour) (Rothenberg and Joris 2004, pp. 261–62) at the end of Part I. We find visual perch for this line of poetry along the long, central line of the composition. It is a striking line, dividing one side into a dog-like muzzle and the other into a woman with long wild hair. It runs perpendicular through the word CHRONIQUE and through the article about the reconstruction of Orleans, France. A closer look at the placement of this longitudinal line reveals it dissecting the word CHRONIQUE (from the CHRONIQUE JURIDIQUE or “legal column” which we shall revisit in the following paragraphs) and covering the letters “ec” in “reconstruction”, which yields a “ron…” on one side, and one “…RON” taken from the remains of CHRONIQUE on the other side of the bold line. Since the artist has made some effort redirecting and doubling over his slightly errant line prior to intersecting “reconstruction”, we find the erasure of “e” and “c” operative. It creates two “ron” touching that line, itself reminiscent of a gallows. Ron-ron is the French onomatopoeia for a cat’s or a motor’s (or the clock’s) purring.

Part I ends with “ronron a l’heure” and Part 2 of the 1947 poem starts “Il précise où l’horloge se fane” (exactly when the clock wilts) which is better understood only in the knowledge of the newspaper’s content. The bold-type “des fleurs” (flowers) appears atop the newspaper next to the name of this section “derniere minute” (last-minute news, eleventh-hour news). Flowers fade; hence, the time is fading or wilting in the last minute. Other references to time have been left, one on the forehead of the portrait of Olga. The French “CHRONIQUE” has been painted over with solid black brushstrokes, begetting the word “CHRON” of course the root for “time”. Considered with the next part of the headline, “CHRON…LA REDUCTION…” offers further explanation for the introduction to part 2 of the poem “précise où l’ horloge se fane”. Again, time is fading…

The rest of the headline would have been of particular notice to Picasso around this time: LA REDUCTION LOYER AU PRIX LACTITE (The Mandatory Reduction of Rent), where Picasso had just recently been denied for a reduction in his rental’s rate (Richardson 2021).10 To the immediate right of the article discussing the reduction in rent for housing and the heading CHRONIQUE JURIDIQUE is an advertisement for dog races. Paris Soir’s predicted winner for each of the eight races to be held the following day is listed under the word LEVRIERS (greyhounds). “L’aurore boréale” Part II continues “…levres a levres” (lip to lip) but makes more poetic sense as “levriers a levriers”, especially considering Picasso’s canine companion is a “levrier Afghan”. Half of the painting on newsprint post-4 November 1941 is an image of Picasso’s dog, and the artist enjoyed finding opportunities to insert his beloved “Kazbec” (Penrose 1980).11

The poem continues “les plis du lac” (the wrinkles of the lake), but in the context of this page, it reminds us more of the “PILULE DUPUIS” of the laxative (lac?) advertisement in the drop shadow window (Figure 5). It is located just under the wrinkled right eye of the woman. Notably, the name of infamous Vichy government collaborator Pierre Laval is left plainly visible exactly between two strokes of gray under that eye and the drop shadow.

Figure 5.

An advertisement in a bold drop shadow window on the Paris Soir substrate of Tête de femme/Moscou dans l’angoisse, Paris Soir 4 November 1941, p. 3 (Retro News 2024a). “PILULE DUPUIS au repas du soir” (for) Constipation one Pill Dupuis at the evening meal.

Of “Sur les cordes epinglant…” (on the ropes pinning) or (arresting/collaring on the ropes), we suggest the “cord” as the long stroke painted from the forehead of the figure all the way to the bottom of the chin. Again it is that striking vertical line which not only divides the east–west facing woman and hound but also pins the drop shadow window “…la fenêtre à l’ombre” (the shadow window) of the laxative advertisement “portée faisant ses besoins” (within range of doing its business) to the name of Pierre Laval. According to (Rothenberg and Joris 2004, p. 262), “pinning the window to the cast shadow relieving itself exactly at the foot of the gallows”. Picasso predicts Laval’s appearance on a gallows, which gallows is shaped by that connecting center line. The poem states “justement au pied du gibet” where justement can mean “exactly” but also “justifiably” or “correctly so”. Picasso would seem to have agreed with having this business done to Pierre Laval. Laval was already well hated in France by 1942 (Time Magazine 1942) so Picasso’s prediction of his execution, if not completely prescient, was indeed borne out by history. The stanza ends with “peint en vert” where no green, in fact, no colors or color references could be found. Consider how the subject of the poem is painted upside-down and, voilà! “Peint invert”.

In light of the Palette of Words theory, these two works appear uniquely linked in their subject matter and details to the newsprint of Paris Soir, 4 November 1941. Negative spaces have been very carefully composed around the items of interest in a way which, we submit, cannot be assigned merely to coincidence or better explained in any other more likely way. Imaginary, metaphoric, and painted lines connect topics in the method of the Master “le rapport de grand écart” (the greatest of possible ironies/contrasts) as described in (Gilot and Lake 1964). Those items then reappear in the poem, an index to the objects, subjects, and paintings on the newsprint.

2.2. Example Two

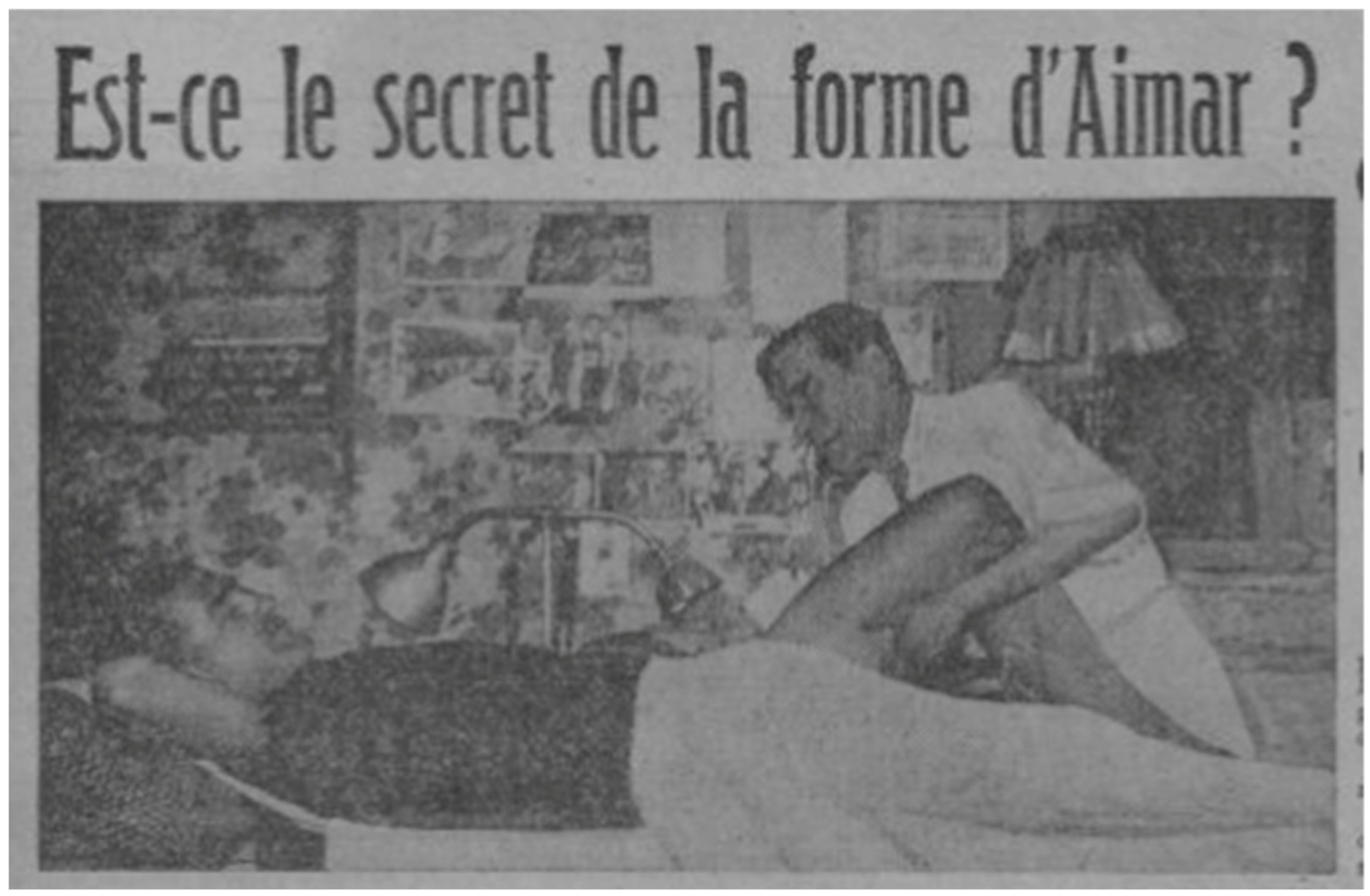

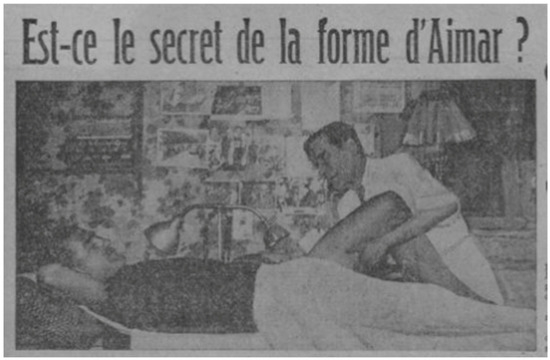

Please see Portrait de Dora Maar on Paris Soir 19 September 1941, p. 4 (Paris, private collection) on https://picasso.shsu.edu, accessed on 16 February 2025 (Mallen 2024). At the top of Page 4 of Paris Soir 19 September 1941 (Retro News 2024b) are four columns and four headlines to the stories below. In Portrait de Dora Maar (post-19 September 1941) done on that page, two headlines are left visible on either side. Of the headlines in the middle columns, one is completely obscured and the other is cut in half with a bold black line. The obscured column and the title of the page is “SPORTS”. The headline on the right reads “Les ‘As’/du patin à roulettes/vont s’affronter en plein Paris” (The Aces of roller skating to confront each other in Paris). The headline on the left reads “Est-ce le secret de la forme d’Aimar?” The headline is imperfectly obvious only because it asks “Is this the secret of the form d’Aimar?” instead of “Is this the secret of the form of Picasso?” for example. Or “Is this the secret of the form d’Aimar which just happens to rhyme with Dora Maar?” This is how we expect that the artist intended it.12

First, we notice the lines of the subject’s hair in relation to that headline. It is perfectly aligned, exposing the question. The question mark punctuating the headline also punctuates the Portrait de Dora Maar, whose hairline gently rests upon it. In such a position, the question in the headline becomes a question to the viewer, posited by the Portrait de Dora Maar. All that could be missing is the speech bubble common to comic book dialog! The photograph, now half-obscured by lines of paint, is of a slightly risqué nature. It depicts the suntanned leg of Mr. d’Aimar, a National Grand Prix athlete, bare from the groin down to the ankle and in the hands of an expert masseur (Retro News 2024b). The photo itself (Figure 6) might remind some readers of the 1942 painting L’aubade.

Figure 6.

The newsprint substrate of Portrait de Dora Maar, Paris Soir 19 September 1941, p. 4 (Retro News 2024b). The top, left of the sports page shows the bare leg of a cycling champion in the hands of a masseur. The headline hints at more messaging from the artist.

expressément nue cachée sur le torchis des roues détachées du char d’ or immobile et glacée pieds collés au feu desparfums peints criant attachés aux fers plantés dans la chair vive amphore parlante muse aux milledéguisements femme orchestre immense soufflant ses illuminations de coquillages et ses givres sur la peautendue du paysage collé aux vitres une main se détache des bras et pose ses lèvres au fond des arcs derubans aux mille couleurs irritées il prend le sein glacé des ailes tendues les liquides châteaux brillants decartes à jouer découpant l’ ombre huilée poissant la robe déchirée de bal de la persienne le doigt divin quialerte la tache vert pomme de son ongle la peinture gris souris et les bleus décousus de la tasse flagellent lesroses défaillantes les plumes mordorées et les bistres et les sourires des chants et des danses et descalligraphies si compliquées et odorantes la folle orgie imprimée sur les tubes ocres des tuiles goutte à floconsdécantent sur les plis du corsage ouvert par l’ arme la cadence voulue aux fleurs fermées de l’ horloge délayéedans l’ aquatinte des gestes du tambourin frappant du bec le marbre la précipitation du calme arrivant par-dessus bord les angoisses emmêlées aux plaintes les graines de pavot grillées et le bruit de gros sous sautantsur les briques dénudées les pas marquant l’ heure à chaque coup d’ aile les assauts des feuilles qui meurentà chaque étage et les marques de feu inscrites sur la peau d’ écailles souffrant les pampres poudrés de lune etles courses d’ obstacles gagnées et perdues aux cirques étalés entre les poils du ciel accordent aux victimesles soupirs et l’ indulgence du mur pendu aux mirages des miroirs un seul espoir bat le tambourin debout surl’ eau qui monte en cataracte la moisson faite et les blés rentrés neigés en pluie d’ or et d’ argent sur le ventreouvert de l’ éventail du temps développant ses grâces et ses caresses l’ amidon qui couvrira la page entièresoutient la chance qui dépend de l’ arbre ses fruits secs et ses pots de mûres le fiel collé au doigt chante etsiffle dans la plume dorée qui avance en traînant ses jambes nues ni un grain de riz ni un ver luisant ni une

épingle le dessin cru du ver saute à la gorge du gris ardoise de l’ herbe des moutons et vient manger sa soupeau creux de la main de l’ écharpe lilas qui se déchire aux ronces plus visiblement qu’ à l’ oreille un enfantpleure

Moving right across the top of the paper, after the carefully crossed-out title of the “SPORTS” column, appears possibly the boldest, darkest line (or actually two lines) on the page. The double black line continues to the top of the page and leaves the paper. Did the artist break with composition rules in leading the viewer completely off the paper? Quite the opposite—he is showing us how to decipher the painting, and to an extent, the poem “expressément nue”.

Originally, “Le football a pris un curieux départ” or “Football has got off to a curious start” is a headline we expect to arouse the curiosity of our reader. Picasso would have read and experimented in his mind how to paint over it, and what to leave unpainted. What remains is “Le footb”. We notice now that the Dora Maar image is also a human foot or footprint. There happens to be a complete foot stomped onto the Dora Maar’s face, with all five toes hidden in the bangs of her hair. It is not unlike the imprint that would be struck in a plaster of paris cast. Interestingly, the functional remains of the headline become “Le foot…a pris” perhaps “the foot taken”. One may wonder if it is the bare foot taken from the bottom of the leg of the cyclist in the photo. The creation of this visual double (treble, or quadruple) entendre must have given Picasso some amusement and satisfaction.

The poem dated 23 February 1942 begins “expressément nue…” (expressly nude) which becomes the title ascribed to it. It contains reference to “glacée pieds collés” (ice cold feet glued…but with “collés” understood also as “collage”) in the first lines, and later to “naked legs”. We understand this starting with the naked leg of Mr. Aimar the cyclist, then the foot-shaped face of the Dora Maar. The start of “expressément nue” identifies the Portrait de Dora Maar on this edition of Paris Soir: “…cachée sur le torchis des roues détachées du char d’or immobile et glacée pieds…” (distinctly naked hidden on the daub of the wheels come off the immobile golden chariot and ice cold feet) (Rothenberg and Joris 2004, p. 251).

On the front page of Paris Soir, this bold claim “‘Un trésor est caché dedans’” (a treasure is hidden inside) appears, sharing equal weight opposite “ROOSEVELT fait pression sur le Vatican” (Roosevelt pressures the Vatican). In answer, the poem tells us that something is indeed hidden inside this painted newspaper and tells us its location. “Cachée sur le torchis” is interpreted as “hidden on the daub”, “hidden on the crosshatch”, or “hidden on the trellis”. It can now be understood to mean the continuation of this light news article about a woman taking children out for a scavenger hunt “l’héritage de Joséphine Carron” (Retro News 2024b). It is hidden under the daub or crosshatch at the bottom of the Portrait de Dora Maar, on the verso. The Carron article also happens to contain the phrase, “…must never give up”. Could it be more Resistance messaging?

Continuing across the page, the headline describes a roller skate race: “Les ‘As’/du patin à roulettes/vont s’affronter en plein Paris”. Noting the lightness and superficiality of such heavily curated and reduced news, was Picasso’s sardonic sense of humor not piqued? Or perhaps it was just the right vehicle to move his art down the page. In the poem “des roues détachées du char d’or immobile” (the wheels come off the immobile golden chariot) (Rothenberg and Joris 2004, p. 251) relates to the three red spiral shapes cascading down the news page in the Portrait. The imagery of the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, which drew extensively on Hellenistic references such as to chariots, was still fresh in European memory. In the context of wartime, we notice that the word “char” also means tank and that the place name Sochaux appears directly above, almost touching the nostrils of the snout in this picture. Machinery for the German war effort, including whole military vehicles, was being manufactured right outside Paris in the gigantic Sochaux Peugeot factory (Bruno 2020) for the greater part of WWII. Meanwhile, France’s only working “chariots” had been reduced to roller derby. We wonder if the poem’s mention of “fers plantés” is a mixture of French and English referring to the iron plant of Sochaux. Metals were in painfully high demand at the time. While the metal works at Sochaux may have been of particular interest to Picasso or not, based on his prolific work in bronze during the war (Finn 2016), it is nearly certain that he would have been aware of these facts and more about Sochaux, and of the existence of the large foundry in the Sochaux plant.

One point in the poem presents a stream of colors, rearranged here as a list:

- la tache vert pomme de son ongle “the apple green spot on her nail” (Google Translate 2024)

- a peinture gris souris “the mouse gray painting”

- et les bleus décousus de la tasse flagellent “and the unstitched blues of the cup whipping” (Google Translate 2024)

- les roses défaillantes “the waning roses”

- les plumes mordorées “the bronze feathers”

- et les bistres… “and the bisters…”

- …sur les tubes ochres “…on the tubes of ochre”

Black oil-painted lines comprise the majority of the Portrait. The only other colors in the painting are bits of gray, red, and a bronze brown. The paint has aged for over 80 years at the time of this writing, but there are still some things upon which the colors can inform us. The gray tears, “l’eau qui monte en cataracte” like “water that shoots up a cataract” (Rothenberg and Joris 2004, p. 252) are brushed gently under the eyes of the weeping woman. Juan Gris (nee Gonzálas-Pérez) adopted the name “Gray” upon arriving in Paris in 1906 and finds himself referenced in the poem of 23 February 1942 as “la peinture gris” (technically “the gray painting” but with the painter implied) and in the gray of Portrait de Dora Maar. Gris was a fellow Spaniard and friend of Picasso who painted in cubist form for the entirety of his career. Gris painted portraits of Pablo and addressed him “Dear Master” or “Dear Teacher” (Stein [1933] 2019). Although the lesser-known compadre had died many years prior, Picasso surely maintained his memories of Gris and their time in Montmartre together.

We only have to know that the French national football team is affectionately referred to locally as The Blues to make sense of “et les bleus decousus de la tasse flagellent les roses défaillantes” (and the disjointed blues of The Cup beaten by the failing roses). The story under the headline “Le football a pris un curieux départ” tells a dire tale of such a brutal drubbing of the national team (The Blues) in the first game of the championship at the hands of Brittany’s team (the Roses).

The red spirals spinning off and falling from the eyes have already been identified alternatively as roller skate wheels and the faulty, sabotaged wheels of the immobile tanks built at Sochaux. They also form the simplest interpretations of the rose, identified in the poem as “the waning roses”. Then, in “the bronze feathers” we see the sepia-shaded highlights in places throughout the Portrait’s hair or headdress. The mention of bister in the poem raises an intriguing possibility. Many Old Masters incorporated a technique of shading using this “transparent brown pigment derived from the soot of burnt wood” (Oxford Publishing 2024).14 Looking closely at the trellis or plaid dress of the Portrait de Dora Maar, we see the lines are composed not of solid black, or not only black but also with diluted bister-like brown strokes; a technique noticeably absent from his other paintings on newspaper from the War.

We should mention here that we accept the possibility that the parade of colors in the poem is not explicitly related to the painting, or that they relate not as colors per se but as representatives of other concepts, events, or people in the artist’s personal vocabulary. La tache vert pomme de son ongle might refer either to a green apple, green or spotted wartime potatoes pomme de terre, or something else belonging to his son Paulo, the “son of Olga” where as we have noted that ongle translates as his estranged Olga Khokhlova. “Tubes of ochre” we could not easily find, although the verso of page four (Retro News 2024b) does offer some tubes of a dental product for correcting yellow, nicotine-stained teeth.

Similarly, the poem makes numerous references to cold, ice, frost, freezing, and such, which makes ample sense upon the writing of “expressément nue” in February 1942, but to which we cannot assign a particular meaning on the Portrait de Dora Maar. Not giving up completely, other researchers (Danchev 2010; Meyers 2006) have occasionally consigned certain characteristics or points of interest to the artist’s personal vocabulary, forever inscrutable. Nonetheless, we present these understandings and methods for study along with their seeming enigmas.

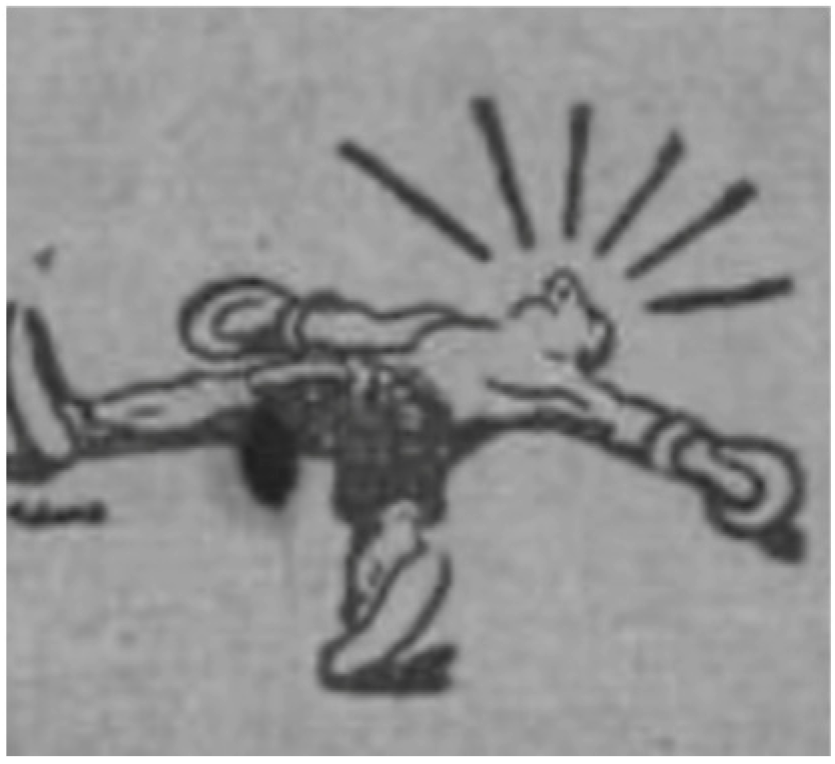

We did, however, on the hardcopy reproduction of Paris Soir, put our fingers on the graphic of a boxer lying knocked out (Figure 7). However comical this little man may be, unconscious, he compliments the article describing a Spanish fighter. Holding our fingers on the reverse of the sports page, pressed to the small graphic, we recall the poem’s mention of a circus as we flip the paper over. By no mistake, our fingers meet on the article about a circus director allegedly robbed by Jews. “Expressément nue” reads “…gagnees et perdues aux cirques étalés…” (lost and won at circuses laid out).

Figure 7.

The graphic of a fighter laid out unconscious appears in the Sports section under the Portrait de Dora Maar. Paris Soir 19 September 1941, p. 4 (Retro News 2024b).

One noticeable convergence occurs in the headline “au fil de l’air” on the left side of the newspaper and in the poem “et des calligraphies si compliquées et odorantes la folle orgie imprimée” (and calligraphies so complicated and odorous the foolish orgy in print) (Rothenberg and Joris 2004, p. 251). Where “folle orgie” has been interpreted as “crazy orgy”, it could just as well have meant a foolish one. “…The foolish print orgy” seems most informative in light of the cursive font used in the headline “au fil de l’air” (Figure 8) as well as the meaning of that headline, sky writing. “De l’air” has several possible uses, one in painting (Grimaux and Clifton 1883)15 but also as an exclamation, a plea to clear the air as in “Get some fresh air in here!” or to order someone out of a room, and occasionally as in the sense of “Who farted?”. The folly of all this superfluous calligraphy in the headline and in the sky finds itself the target of some boyish humor in Picasso’s remark on odors, and those little clouds (of odorous gas) in the headline. With this interpretation, we understand the author’s intent (expressing again mainly bewilderment, exasperation, and sarcasm). It also links the poem with the newspaper, and the Portrait de Dora Maar painted on it.

Figure 8.

A section heading graphic on Paris Soir 19 September 1941, p. 4 (Retro News 2024b). Au fil de l’air, sky writing.

Left and above the “au fil de l’air” graphic, “France ne pas encore battus” (France is not yet beaten) was quite clearly left visible through the brushstrokes forming the Dora Maar’s feathered hair. It is an act of resistance as clear as any to state that France is not yet beaten at this time. It is a phrase which echoes the words of General Charles DeGaulle, spoken in England but broadcast to France on 18 June 1940. That has become regarded as one of the most important speeches in French history (UNESCO 2004). The exiled DeGaulle admonished: “But has the last word been said? Must hope disappear? Is defeat final? NO! Believe me, I speak to you with full knowledge of the facts and tell you that nothing is lost for France”. The speech is considered a call to arms and the beginning of the French Resistance by many (UNESCO 2004).

The intact eye of the woman in the painting looks onward to the cleverly hidden message in her hair. Other pointers are the subtly brown eyebrow leading directly into the headline, the straight portion of the red line of the falling wheel or rosette, and the placement of her feathery hair. Two of the darker, black lines of hair help to form a triangular frame in which the improved headline is now situated. The eyebrow itself covers the unwanted verbiage, perhaps notably the numbers of meters in world records held by France “1000 et 3000”, which numbers find reflection in the poem as “mille couleurs” and “muse aux mille déguisements femme orchestre immense” (muse of a thousand disguises huge one-woman orchestra) (Rothenberg and Joris 2004, p. 251). We notice there is a kind of one-man orchestra in the cartoon Les Adventures de Lariflette occupying much of the space under Dora’s blouse (the crosshatch). The poem continues, “soufflant ses illuminations”. Soufflant could mean whispering or suggesting, and illuminations, meaning lights or enlightenments.

The last thing we noticed in the painting might ought to have been the first. The Official List of dignitaries of the Freemasons is published, perhaps oddly on the SPORTS page of Paris Soir. It appears directly under the photo of the cyclist’s leg, on the same horizontal as the Dora Maar’s enucleated eye. Suddenly one may notice the twinkle, asterisk-like, especially in that falling (proper right) eyeball. It composes not only a twinkle but a pyramid and rays of an Eye of Providence or “God’s eye” common to Freemason symbolism. There is a similar-looking composition dated 30 September 1941, eleven days after the publication of the Paris Soir newspaper used under the Portrait de Dora Maar. Please see Tête de figure fêminine, 30 September 1941 (Paris, private collection) https://picasso.shsu.edu/, accessed on 16 February 202516 (Mallen 2024). It is known as Tête de figure fêminine, but might have been a study for the Portrait de Dora Maar. In it, the God’s eye is more pronounced and is imposed over the image of a distinctly masonry pyramid. The pyramid of the God’s eye on newsprint points directly to The Official List of Freemasons declared essentially persona non-grata and their addresses situated in the adjacent column.

Among the very first institutions and houses of records which were occupied and looted by the German army shortly after the invasion were in fact the lodges of the Freemasons, who had long been held in suspicion and regarded as being influential and powerful (U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum 2005). The poetic “Le bruit de gros sous sautant sur les briques dénudees les pas” (the sound of fat coins, or big money, falling on the bricks bare footsteps) would now seem to refer rather directly to those acts and the List produced in the sports page next to the Dora Maar’s falling or hanging God’s Eye. The “bricks” in the poem, the Freemasons, had indeed been “stripped” or “denuded” either literally and/or stripped of their power. Masons were immediately barred from public service by the Occupation, and many members were arrested, robbed, stripped, or deported (presumably to concentration camps). Surrealists had long been acquainted with Masonic ritual and symbology, having adapted some from the Masons’ and developed their own as well. Juan Gris had achieved the rank of Master Mason (Gómez 2014).17 The Official List of Freemason Dignitaries must have brought Picasso’s memories of Gris to mind; memories made visible in the gray colors highlighting the God’s eye and pointing to the Nazi blacklist of Freemasons. The poem, the painting, barefootedness, and other imagery is steeped in reference to Freemasonry and this particular tyrannization under the Nazis. The campaign against Freemasons was severe. The Nazis organized public fora starting in October 1940, displaying the heretofore utterly secret, protected workings of Freemasonry, along with their most cherished Freemason artifacts and riches to demystify and vilify the organization (U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum 2005).

With this information we can now better assess a few words in the bottom of “expressément nue”: “…le fiel collé au doigt chante et siffle dans la plume dorée qui avance en traînant ses jambes nues ni un grain de riz ni un ver luisant ni une épingle le dessin cru du ver saute à la gorge du gris ardoise de l’herbe des moutons et vient manger sa soupe au creux de la main…”.

It is clear that for the analysis of Picasso’s cubist poetry, direct translation will not always be of assistance:

Collée, which also translates to glue or sticking, in these contexts will likely tend to refer to collage. Le fiel collé means a somehow poisoned or stinking collage, or alternatively the “bile collage” which finds possible reference to certain Freemason rites of initiation (Beaurepaire 2016).18 We interpret doigt chante (finger chants, finger songs) as a reference to the ritual handshakes of the Freemasons. There are different handshakes which comprise a certain code for the brethren, codes which convey membership, rituals of passage, rank, and others. A series of nine sketches done on 16 July 1941 (Mallen 2024) are details of handshakes. The sketches each portray only the clasped two or three hands, with a certain emphasis on the placement of the thumbs. It seems that Picasso had been thinking about Freemason handshaking and overhand thumb articulations for some months before the creation of the Portrait de Dora Maar and “expressément nue”. We view the nine sketches of 16 July 1941 as separate and different in nature and purpose from those done in preparation for the Femme à l’artichaut.

Plume dorée, which translates directly as “gilded feather” but with dorée also holding visual and aural proximity to “Dora”. Plume dorée is the feathery hair of his muse Dora. Avance en traînant ses jambes nues is directly translated as “who advances dragging his naked legs” and makes sense when we consider that the first three levels of initiation in Freemasonry require the candidate to step forward onto the hallowed ground with bare feet and/or bare legs.

Ni un grain de riz ni un ver luisant ni une épingle (neither a grain of rice nor a firefly nor a pin) (Rothenberg and Joris 2004, p. 252) speaks to the miserable fall of the heretofore lofted French Freemasons. Presumably until the day of the invasion they had enjoyed their exclusive, powerful, and rich fraternity in solemn veneration. The “fireflies” or “illuminated” were of course their wise, old leaders. Like other clubs and agencies, the membership identified themselves and their ranks with, among other signs, their lapel pins. Quite suddenly they had found themselves with not a grain of rice, not an illuminated one, and not a lapel pin among them.

3. Results

A few key similarities arise from Examples One and Two above. The poems and the newspapers are written in French. Both examples of a painting on newsprint and its paired poem use the Afghan hound’s snout to sniff things out. Both make references to the Victory V. Both make use of pointers leading to sardonic criticisms of the Occupation while lauding the Resistance. Both required codification and obfuscation for plausible deniability. Of course, codifying, obscuring, or multiplying meanings was a skill already in Pablo Picasso’s set of well-developed skills. It is as likely that Picasso would engage these ambiguities as much for entertainment as for self-preservation. With the poem of the first example, “l’aurore boréale” having been written well after the end of the war and Occupation and long after any fear of censorship was gone, the former motivation seems to remain operative.

There are many possible reasons, mostly speculative, as to why Pablo Picasso would procure content in just this way. Like anyone who has wanted to comment back to any of the one-way mass media forms but lacked the device to do so, Picasso was in some small way taking control of the narrative by creating his own device for commentary. The words he received from the paper were not only weighed and appraised, but significantly filtered. After the fearful self-censorship of the reporters and editors, the content could undergo further filtration by collaborationist editors and possibly German Occupation censors. That the French language and grammar were already well-weighed and appraised would come with at least two benefits for a non-native speaker: providing confidence and saving him time. That the words were exquisitely censored in favor of an enemy occupation force also provided content rich for commentary. Perhaps above all though, the Palette of Words was a method for Picasso to cull, align, multiply, and encode meaning in a dangerous and chaotic world, cleverly deploying them in his playful nature. The Palette of Words is shot through with wordplay and the playfulness of the artist at times when such playfulness was likely to be seen as superfluous or extravagant in light of the overriding strategy of surviving the war.

4. Discussion

As it happened, there was a triple homicide of a Vichy government official and two household members, including a maid, over the night of 24–25 October 1941 (New York Times 1941). The official’s son was in the house but claimed innocence. Titillated rumors fly of the brutal massacre and the weapon of choice, “la serpe”, which was a common garden tool, also a medieval bill-hook centuries prior. A week-and-a-half after the fact, the triple murder becomes front page news in Paris Soir and features a photograph of the château where the three met their demise.

Picasso thumbs through the newspaper and sees “Moscow in anguish” (reads: Olga) and, atop the same page “La mysterieuse TUERIE d’Escoire” (mystery murders in the Esquire) about the massacre in the château. He knows already or quickly learns of the unusual circumstances and understands that “serpe” is a tool, a weapon, and a snake. He also knows of the mystery novel Fer-de-Lance with that voluptuous orchid on the cover, which he was likely to have at least seen at any number of the book stalls along the river. Fer-de-Lance seems to have been a quite well-known and favorably reviewed mystery in novel, magazine, and cinematic form by this time (Wikipedia Contributors 2024). He realizes the irony inherent and weighs the mystery, the snake, the Fer de Lance as halberd or spearhead, and the swing of the serpe one night not too far away, in a château not unlike his own château. Informationally, the transformation is linear, graphic, and elegant. He then flips the newsprint upside down, thereby allowing for a composition with his own snake or spear head pointing down arrow-like, gently brushing both the flower graphic and the mystery massacre article. With added irony, he can place the head of the serpent in his subject’s hair, a grisly Medusa-like reference to the artist’s estranged wife who was then living in his castle…Picasso’s own Château de Boisgeloup. It must have given him such a sense of accomplishment after the war that he came back to it, wrote the poem, possibly touching up the painting a bit while he enjoyed with nostalgia having survived the experience. Reliving this from the relative safety of July of 1947 would have given the artist great satisfaction, perhaps even resulting in that final line of the poem mais physiquement parfaite “but physically perfect”.

We notice that this is not the only instance of Picasso rotating the newsprint substrate for painting. As it has been shown here, in (Baldassari 2000, p. 152) and others, there is very little chance that the key details in the newsprint occur randomly or unwittingly in, and at times on the reverse of these paintings. Many of them fill a nameable purpose, meaning, or function in the work.

Picasso uses both pages as if in-and-out the sides freely, at times with license, procuring the text, images, and contexts he had found. Some of these were prepared as a “palette of words” either as poems, or poetic indices of a sort, and had also been used as content for his consumption and production into visual art. We propose that these artworks consisting of an altered full page of newsprint, the painting on the newsprint and a poem were composed together, each re-worked, possibly but not necessarily at the same time, but intensely correlated in their subjects, content, and messages. The poem is a palimpsest of a palimpsest on a collaborationist newspaper. Each was used to help form the other as in brainstorming exercises that Picasso would conduct to derive content (events, people, places, times, or the text itself) from and to those intersections which he found amusing or noteworthy. The artist’s love of wordplay and his own comments on his creative process support this.

5. Conclusions

There are a number of consequences to the Palette of Words theory as described. The subject of the painting done on Paris Soir post-4 November 1941 is now known to be his estranged Olga, not Dora Maar or another. The Portrait de Dora Maar (post-19 September 1941) is better understood in light of its multitude of references to bare feet, bare legs, the bare footprint shaping her face and hair, references to feet and legs on the Paris Soir page, and in the poem “expressément nue”. New insight is gained into the content, origins, method, and meanings of two wartime Picasso paintings and poems, with implications for other works not examined here.

André Breton, French writer and poet, co-founder, leader, and principal theorist of surrealism thought very highly of Picasso’s poems. Poems “such [as have] never been kept before!” (Breton 1936). There must be more to understand from these poems, more to decode and decipher. Breton says the prose poems contain the place, the day, and the hour in which they were composed (Breton 1936). Where do they do that, we ask. Of the over 340 poems written between 1935 and 1959, they are almost never titled. They have no punctuation. They do not normally mention the places in which they were written. They are dated but offer no hints as to the hour in which they were composed. In cases when they were re-worked, they are not also re-dated. Why such exaggeration from Breton about these poems? Could he have been privy to the method described here as his “Palette of Words”, incorporating a full sheet or more of newspaper into multiple works of art? Is it possible that Breton had seen Picasso’s process of painting on newspaper, holding it up to the lightbulb or candle light, then looking in and out of both sides through the graphic windows already laid down from the printing press? Perhaps Breton knew of this method Picasso had used, starting from hardcopy inked parameters but making it Surrealist, transliterating between the plastic and the literary. The theory and method described here would give Breton, and us, the places from the newspaper, dates, and sometimes the hour (or in Paris Soir, “derniere minute”, even the last minute) to which Breton refers.

The Palette of Words theory so described yields some heretofore unrealized criticism of the war and conditions in Paris, as found in the reduced, sterilized versions of Picasso’s apparently favorite newspapers. Although Picasso had been subject to great scrutiny, even searches, by the German occupiers and as such was never considered a Resister or a threat, we point out places where Picasso strives to use the “V” and extolls the very word Resistance, and in one instance admonishes the viewer “France is not yet beaten”. It adds to that body of evidence for those who would say Picasso was no collaborator.

This investigation unravels, clarifies, and expounds on an aspect connecting Pablo Picasso’s art and methods during a dire time in European history. The informationally complex and layered nature of the intersections between his poetic and painted works and the newspapers requires some greater or lesser speculation at times, but the sum of them, their particulars, weight, and apparent relevance to Picasso’s personal life and times leaves little doubt. “L’aurore boréale” and Tête de femme/Moscou dans l’angoisse; and “expressément nue” and Portrait de Dora Maar (post-19 September 1941) are tightly related artworks and should be considered in pairs, together with their Paris Soir newspaper substrates. We can be all the more assured that there are many relationships and references intended by Picasso himself which we have failed to uncover and consider here, and other works not yet mentioned which Picasso created similarly. As extrapolated herein, the Palette of Words Theory leads to a considerable body of potential future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S.; methodology, N.N.; formal analysis, N.N.; investigation, R.S. and N.N.; data curation, R.S.; writing—original draft, N.N.; writing—review and editing, R.S. and N.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in [Online Picasso Project] at [https://picasso.shsu.edu/index.php, accessed on 16 February 2025], and [Retro News] at [https://www.retronews.fr/journal/paris-soir/04-nov-1941/131/97865/3, accessed on 16 February 2025] and [https://www.retronews.fr/journal/paris-soir/19-sep-1941/131/106379/1, accessed on 16 February 2025].

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge their wives and children for their patience while we worked on this. Additionally, the digital availability of works on sites such as Online Picasso Project and Retro News was indispensable. Documents extracted from the RetroNews Site are accessible at the address www.retronews.fr. Any reuse of these documents must be part of the subscription conditions provided by the RetroNews site.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Picasso to Louis Parrot as quoted in the Preface of Rothenberg and Joris. |

| 2 | #25 You moved my slippers, in Conversations with Picasso, a photo of Picasso’s chair with stacks of magazines and newspapers on and around it |

| 3 | Tête de femme, sometimes known as Moscou dans l’angoisse, done on page 3 of Paris Soir, 4 November 1941, https://cep.museepicassoparis.fr/explorer/tete-de-femme-mp1990-72, accessed on 16 February 2025 (Centre d’Études Picasso 2025). As a representation of Olga, it is a stark contrast to the 1918 version. A very fan-shaped presence dominates the head and hair or horse’s mane of its subject. |

| 4 | Olga in an Armchair Portrait d’Olga dans un fauteuil c. 1918, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/656448, accessed on 16 February 2025 (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2024). One will notice the artist’s attention to light, shadow, textiles, and textures, and especially the central presence of one apparently silk, flower-printed, hand-held fan, partially folded. |

| 5 | What might have been a play on words, an artistic pun on Olga’s fingernails, and a possible nickname (read Ongles, fingernails), “a few searching strokes”, as interpreted by The Met (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2024), dangles in the unpainted background, directly under the Olga figure’s fingertips. “Picasso contrasts the finely detailed and meticulously executed figure with an indeterminate background, accentuated with only a few searching strokes and a gray wash. That Picasso exhibited this work in 1921 suggests that he considered it finished, despite having left portions of the picture unpainted”. |

| 6 | Leiris, Michel in the Afterword to Rothenberg and Joris (Rothenberg and Joris 2004). |

| 7 | Notice that the date and title of the newspaper are the same, but that some significant contents are changed or shifted (notably the Moscou dans l’angoisse article is replaced with a call for enlistment and exchange of prisoners). The story of the Girard murders is still present. |

| 8 | Also quoted extensively in Wikipedia, French Resistance. Starting with the summer of 1941, “V” remained one of the main symbols of the Resistance for the rest of the war. |

| 9 | Notice the possibility of “enormes amphores trainees” where traînée = tramp, bitch [pejor.], cunt [pejor.] [vulg.], according to (DeepL 2024). |

| 10 | (Richardson 2021) Richardson, John. 2021. A Life of Picasso: The Minotaur Years 1933–1943, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, p. 211. “As May turned into June (1940), a flood of bad news reached the artist…none worse than the result of his efforts at naturalization… In the file compiled by the police, events from Picasso’s past were also cited as reasons to refuse his application: In 1905 he had been identified as an anarchist; He failed to fight for France in WWI; He supported the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War; and despite his considerable wealth, he had recently tried to have his rent reduced. Without French citizenship, the fear of extradition would continue to hang over the artist’s head”. |

| 11 | (Penrose 1980) Penrose, Roland. 1980. “A similar kind of metamorphosis could have its origin in a mixture of sources, some benign. The obsessive beauty of Dora Maar inspired Picasso for a host of inventions. Frequently her radiant face with shining eyes was transformed into a bird or the head of a nymph with budding horns and at times the long aristocratic head of his Afghan hound was merged into paintings which, although they could not be called portraits, were still in essence Dora”. |

| 12 | Portrait de Dora Maar on Paris Soir 19 September 1941, p. 4 (Paris, private collection) https://picasso.shsu.edu, accessed on 16 February 2025 (Mallen 2024). The composition creates a conversational interplay between the elements comprising the subject, and the contents of the newspaper below it. |

| 13 | (Mallen 2024) indicates “expressément nue”, Part 1: although no Part 2 seems extant. |

| 14 | Oxford Reference Online: “Bistre, the “transparent brown pigment derived from the soot of burnt wood”. |

| 15 | (Grimaux and Clifton 1883) Grimaux, Adrien and Ebenezer Clifton. A New dictionary of the French and English languages compiled from the dictionaries of the French Academy. Paris: Garnier. 1883. (Online.) Accessed 14 July 2024. Available: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6359566k/texteBrut, accessed on 16 February 2025 “donner de l’air a un tableau, to give distinctness to a painting: to make the principal figures stand out well”. |

| 16 | Tête de figure fêminine, 30 September 1941 (Paris, private collection) https://picasso.shsu.edu/, accessed on 16 February 2025 (Mallen 2024). The shape and orientation of the face, the beginnings of the footprint, and the sparkling or rolling rosettes or wheels are very similar to that of Portrait de Dora Maar in Note 12, but the sparkly eye and pyramids are somewhat more prominent. |

| 17 | (Gómez 2014) Gómez, Inigo Sarriugarte. Perspectivas Masónicas en la Vida y Producción Artística de Juan Gris, Cuadernos de arte e iconografia, ISSN 2660-6542, Vol. 23, No. 46, 2014), pp. 543–547 (from the abstract) pg. 543 “In opinion [sic] of Juan Gris, the Cubism is not only a technique, but a way to generate a spiritual representation of his era, where the Masonic side begins to have a reference value. Juan Gris starts in Voltaire Lodge of Paris in 1923, belonging to the Grand Orient de France. He regularly takes part in its meetings, assuming an active role, which allows him finally to access the degree of Master Mason. In this connection between the Spanish painter and the Freemasonry, there are represented objects that can be interpreted under this aspect, in fact, on the centenary exhibition catalog Hommage to Juan Gris (1887–1987). Centenaire its naissance, there is the drawing of a Mason by Juan Gris. Similarly, in his pictorial production, there are objects commonly used in the Masonic ritual, as is the square, the checkerboard, the book, the compass… and hourglass…” |

| 18 | (Beaurepaire 2016) Contains a list of 37 questions about the meanings of various Knights of the Bow symbols with some detailed answers, e.g., “What does the wine signify? It signifies the bile and the vinegar we showed Our Lord. Jesus Christ on the Cross” and “I have never drank such salted wine since I was received as a knight”. |

References

- Acoca, Miguel. 1971. Picasso turns a busy 90 today. International Tribune, October 25. [Google Scholar]

- Baldassari, Anne. 2000. Picasso Working on Paper. London: Merrell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Beaurepaire, Pierre-Yves. 2016. A Strange Encounter: Nobles Jeux de l’Arc and Masonic Lodges in the Eighteenth Century. Renaissance Traditionnelle 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton, André. 1936. Picasso poète. Cahiers d’Art 187. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, Victoria. 2020. Axis Denied. Driven to Write, November 13. Available online: https://driventowrite.com/2020/11/13/porsche-peugeot-war-reparations (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Buncombe, Andrew. 2017. Allied forces knew about Holocaust two years before discovery of concentration camps, secret documents reveal. The Independent, April 18. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/world-history/holocaust-allied-forces-knew-before-concentration-camp-discovery-us-uk-soviets-secret-documents-a7688036.html (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Centre d’Études Picasso. 2025. Tête de Femme. Available online: https://cep.museepicassoparis.fr/explorer/tete-de-femme-mp1990-72 (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Crowdy, Terry. 2007. French Resistance Fighter: France’s Secret Army. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Danchev, Alex. 2010. Picasso’s Politics. The Guardian, May 8. [Google Scholar]

- DeepL. 2024. Traînée. Linguee English-French Dictionary. Available online: https://www.linguee.com/english-french/search?source=french&query=traînée (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Finn, Clare. 2016. Picasso’s Casting in Bronze During WW2. In Colloque Picasso Sculptures. Paris: Mus’ee Picasso Paris, pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Flanner, Janet. 1957. Pablo Picasso’s idiosyncratic genius. New Yorker, March 2. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1957/03/09/picasso-profile-the-surprise-of-the-century (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Gilot, Françoise, and Carlton Lake. 1964. Life With Picasso. New York: McGraw-Hill Inc., p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Google Translate. 2024. Available online: https://translate.google.co.jp/?hl=ja&sl=auto&tl=ja&op=translate (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Gómez, Inigo Sarriugarte. 2014. Perspectivas Masónicas en la Vida y Producción Artística de Juan Gris. Cuadernos de Arte e Iconografia 23: 543. [Google Scholar]

- Grimaux, Adrien, and Ebenezer Clifton. 1883. A New Dictionary of the French and English Languages Compiled from the Dictionaries of the French Academy. Paris: Garnier. Available online: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6359566k/texteBrut (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Huffington, Arianna. 1988. Picasso: Creator and destroyer. The Atlantic, June 1. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss, Rosalind. 1998. The Picasso Papers. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- Mallen, Enrique. 2021. Pablo Picasso and Dora Maar: A Period of Conflict (1936–1946). Chicago: Sussex Academic Press, p. 161. [Google Scholar]