Shouting Catfish and Subjugated Thunder God: A Popular Deity’s Criticism of the Governmental Authority in the Wake of the Ansei Edo Earthquake in Catfish Prints

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Ansei Edo Earthquake and Catfish Prints

3. The Catfish in “Prodigal Buddha Social Reform Satirical Chant”

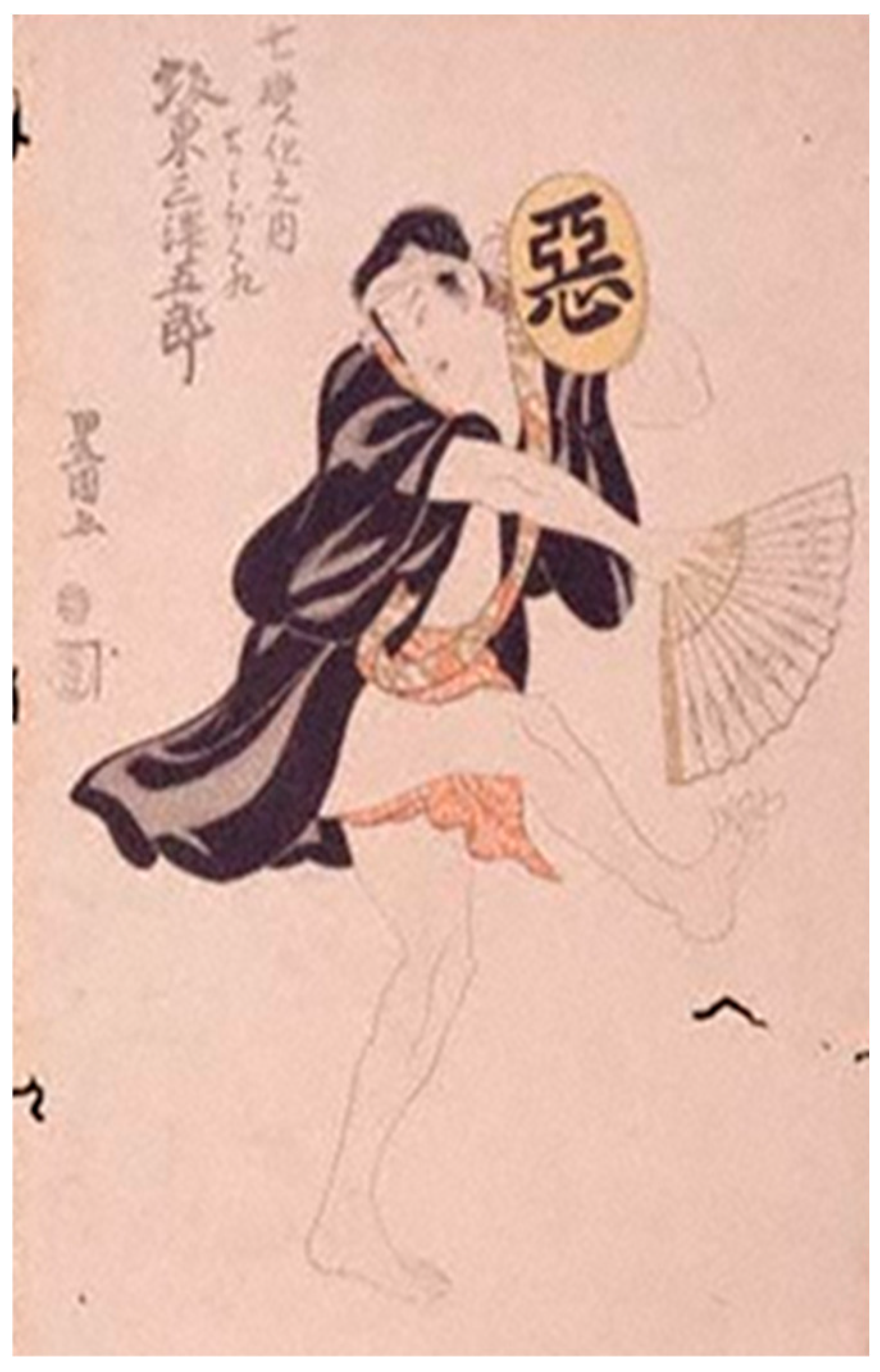

3.1. Chobokure Chanting

3.2. Criticism of Buddhist Temples

The earth cracked, mud gushed out, and things toppled from shelves; people fell down because it was impossible to stand upright, and it was challenging to protect themselves from the continuously falling roof tiles and walls of mud. The evacuees had to shelter in wet, cold fields, holding their empty stomachs in a state of misery.

So many people died during the disaster that there were not enough coffins for all the corpses; bodies were put into barrels, tea boxes, and sugar containers. Even worse, some bodies were pushed into rainwater tanks covered with slimy green algae. The Buddhist priest was displeased by the decline in alms. Not only did he not recite the Buddhist sutras, but he also did not perform the last rites for the deceased. The crematory was heavily crowded with the newly dead, and the crematorium worker grimly stated that it would take more than ten days to cremate all the bodies.

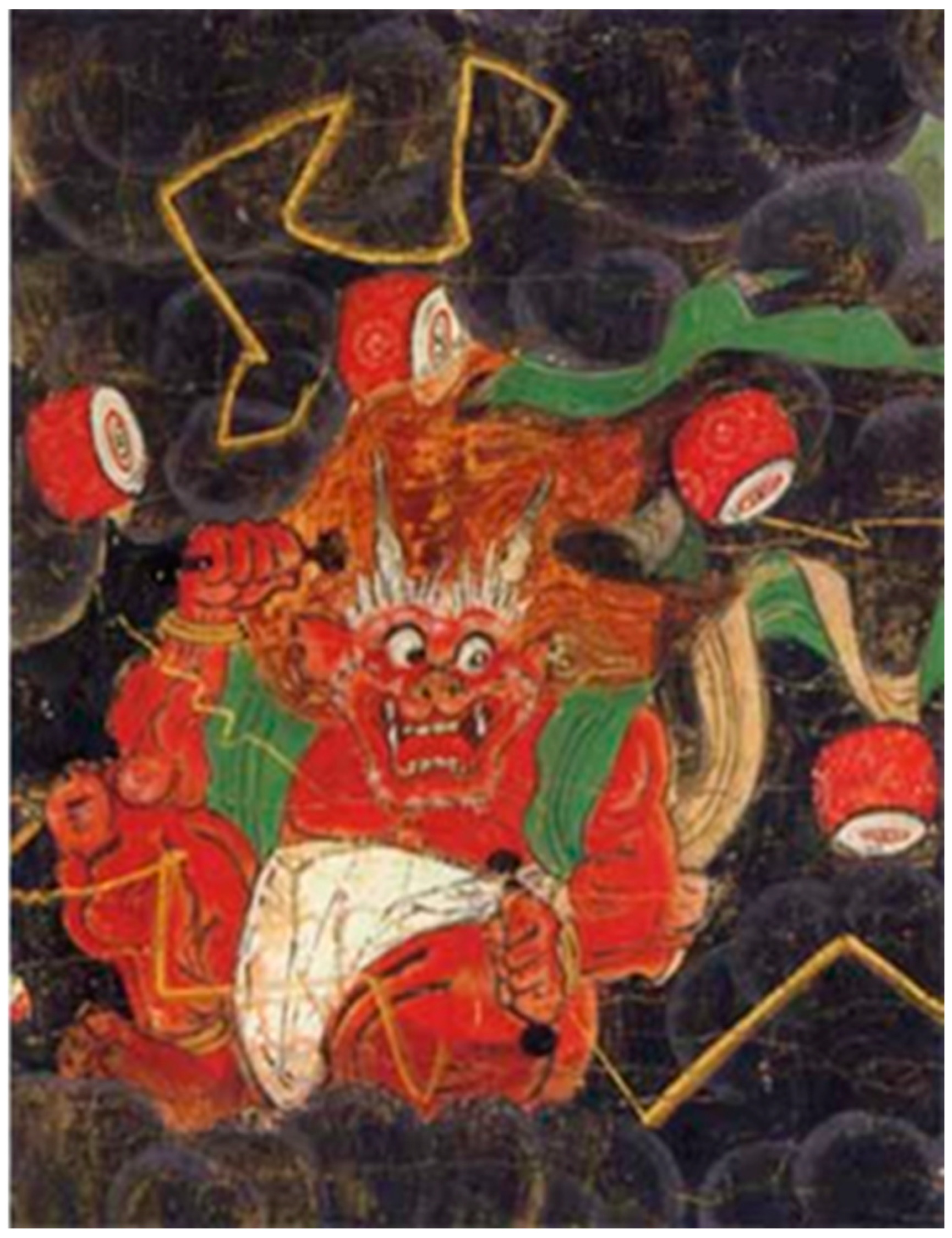

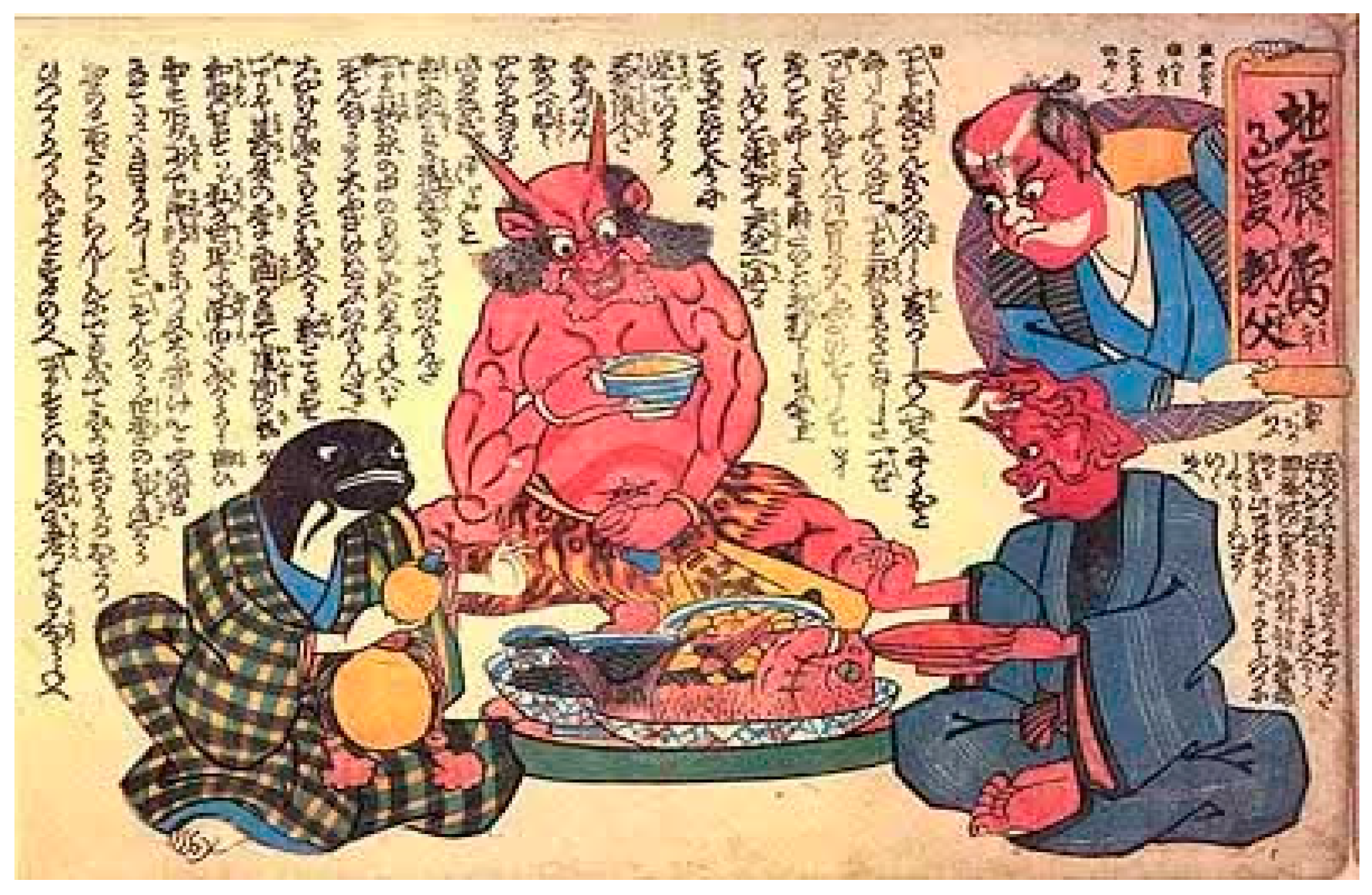

4. Thunder Gods vs. the Catfish: Shifts in Power Dynamics

4.1. Catfish Prints Depicting Catfish and Thunder Gods

4.2. Catfish Challenging Governmental Authority

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | During the Ansei period, other earthquakes occurred outside Edo. To distinguish from these other earthquakes, I call the 1855 earthquake in Edo the Ansei Edo earthquake. |

| 2 | Dates in this article are in the lunar calendar adopted in the Edo period. |

| 3 | The author’s name is unknown; however, the reportage is said to have been written by Kanagaki Robun (仮名垣魯文 1829–1894). |

| 4 | “Kanameishi”, a reportage on the earthquake that occurred in Kyoto in 1662 authored by Asai Ryōi, describes beliefs about the Kashima deity who holds down the earthquake catfish with the keystone to prevent him from causing earthquakes, introducing a poem that reads “The keystone can be shaken but never removed so long as the Kashima deity is there” (ゆるぐとも よもやぬ けじのかなめいし かしまのかみ の あらんかぎりは) (Asai 1999, p. 83). |

| 5 | The Perry Expedition, conducted in two phases from 1852–1853 and 1854–1855, was a landmark event in Japan’s history. American Commodore Matthew Perry arrived in Japan with his Navy warships, aiming to establish diplomatic relations and negotiate trade agreements with the Tokugawa shogunate. |

| 6 | The Tokugawa shogunate issued the Anti-Christian Edict in 1614. |

| 7 | The words yin and yang mean negative and positive, and they are the opposites of each other. The five elements include wood, fire, earth, metal and water. Wood and fire are categorized in yang and metal and water belong to yin, while earth is in between. According to this theory, natural phenomena can be understood by the rise and fall of these elements. It was applied to astronomy, medical science, and calendar and had a strong influence on everyday life in China and Japan. |

| 8 | A historical drama narrating two warrior families, the Kiso Yoshinaka family and the Kajiwara Kagetoki family. It was first written as a joruri play and later was adapted for kabuki. The joruri play was first performed in 1739. |

| 9 | The Japanese character of “fire” is 火事. However, this title uses 過事 (a past event), which is a homonymous term. |

References

- Ansei Kenmonshi. 1855. Available online: https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/wo01/wo01_03754/wo01_03754_0001/wo01_03754_0001.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Asai1, Ryōi. 1999. “Kanameishi.” Essay. In Kanasōshi-Shū. Tokyo: Shōgakukan, pp. 11–65. [Google Scholar]

- Baba, Akiko. 1971. Oni No Kenkyū. Tōkyō: Sanichi Shobō. [Google Scholar]

- Groemer, Gerald. 1999. The Arts of the Gannin. Asian Folklore Studies 58: 275–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijiri Yūkaku. 1757. Available online: https://da.dl.itc.u-tokyo.ac.jp/portal/assets/b7f4b649-ed37-404a-bcec-d7f5bd64e7dd (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Hur, Nam-lin. 2007. Death and Social Order in Tokugawa Japan: Buddhism, Anti-Christianity, and the Danka System. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami, Yoshimasa. 1994. Minkanshinko. In Minkan Shinkō to Minshū Shūkyō. Edited by Noboru Miyata and Manabu Tsukamoto. Tōkyō: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan. [Google Scholar]

- Jinsaiō. 1912. Kogai Zeisetsu. In Kinsei Fūzoku Kenmonshū. Edited by Kokusho Kankōkai. Tōkyō: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 4, pp. 1–379. Available online: https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/949628/1/194 (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Kitahara, Itoko. 2013. Jishin no Shakaishi: Ansei Daijishin to Minshu. Tōkyō: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan. [Google Scholar]

- Matsudaira, Narimitsu. 1998. Matsuri. Tōkyō: Heibonsha. [Google Scholar]

- McArthur, Meher. 1999. Gods and Goblins: Japanese Folk Paintings from Otsu. Pasadena: Pacific Asian Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Miura, Takashi. 2019. Agents of World Renewal: The Rise of Yonaoshi Gods in Japan. Hawaii: University of Hawaiʻi Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miyata, Noboru, and Mamoru Takada. 1995. Namazue: Shinsai to Nihon Bunka. Tōkyō: Ribun Shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Yukihiko. 1957. Chongare Chobokure-Kō: Naniwabushi no Genryu. Yamanobe No Michi: Kokubungaku Kenkyush 3: 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi, Keibō. 1767. Minyō Seiu Benran. Rakutō: Kabunken. Available online: https://www.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kotenseki/html/ni08/ni08_02457/index.html (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Nishimura, Kōchō. 1977. Miwaku no Butsuzō 16: Fujin Raijin. Tōkyō: Mainichi Shinbunsha. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, Hideo. 1967. Kawaraban Monogatari. Tōkyō: Yuzankaku. [Google Scholar]

- Ouwehand, Cornelius. 2013. Namazue: Minzokuteki Sōzōryoku no Sekai. Translated by Kazuhiko Komatsu, Shinichi Nakazawa, Yoshiharu Iijima, and Shinpei Furuya. Tōkyō: Iwanami Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Ryūtei, Senka. 1929. Nai no Hinami. In Nihon Zuihitsu Taisei. Edited by Nihon Zuihitsu Taisei Henshūbu. Tōkyō: Nihon Zuihitsu Taisei Kankō-kai, vol. 12, pp. 731–58. Available online: https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/1226665/1/374 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Saitō, Gesshin, and Kingo Imai. 2004. Teihon Buko nenpyō. Tōkyō: Chikuma shōbō, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Shiba, Zenkō. 1781. Tōsei Daitsū Butsukaichō. Available online: https://kokusho.nijl.ac.jp/biblio/100053942/2?ln=ja (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Shiba, Zenkō. 1785. Daihi no Senroppon. Available online: https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/he13/he13_01480/he13_01480.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Smits, Gregory. 2009. Warding Off Calamity in Japan: A Comparison of the 1855 Catfish Prints and the 1862 Measles Prints. East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine 2009: 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamamuro, Fumio. 1986. Ronshū Nihon Bukkyōshi. Tokyo: Yūzankaku shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Tamamushi, Satoko. 1994. Sakai Hōitsu hitsu Natsu-aki-kusazu Byōbu: Tsuioku no gin’iro. Tōkyō: Heibonsha. [Google Scholar]

- Tomizawa, Tatsuzo. 2005. Nishikie no Chikara: Bakumatsu no Jijiteki Nishikie to Kawaraban. Tōkyō: Bunsei Shoin. [Google Scholar]

- Tō, Minoru. 1968. Kashima Jingu. Tōkyō: Gakuseisha. [Google Scholar]

- Wakamizu, Suguru. 2007. Edokko Kishitsu to Namazue. Tōkyō: Kadokawa Gakugei Shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, Naoko. n.d. Japan Knowledge. Available online: https://japanknowledge-com.uoregon.idm.oclc.org/lib/display/?lid=1001000233434 (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Yamaguchi, Keiji. n.d. Enmeiinjiken Kokushi daijiten. Available online: https://japanknowledge-com.uoregon.idm.oclc.org/lib/display/?lid=30010zz063980 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Yamaguchiken Bunshokan. n.d. Bunshokan Rekishi Nooto. vol. 20. Available online: https://archives.pref.yamaguchi.lg.jp/user_data/upload/File/archivesexhibition/AW13%20rekishinooto/20.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McDowell, K. Shouting Catfish and Subjugated Thunder God: A Popular Deity’s Criticism of the Governmental Authority in the Wake of the Ansei Edo Earthquake in Catfish Prints. Arts 2025, 14, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14020038

McDowell K. Shouting Catfish and Subjugated Thunder God: A Popular Deity’s Criticism of the Governmental Authority in the Wake of the Ansei Edo Earthquake in Catfish Prints. Arts. 2025; 14(2):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14020038

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcDowell, Kumiko. 2025. "Shouting Catfish and Subjugated Thunder God: A Popular Deity’s Criticism of the Governmental Authority in the Wake of the Ansei Edo Earthquake in Catfish Prints" Arts 14, no. 2: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14020038

APA StyleMcDowell, K. (2025). Shouting Catfish and Subjugated Thunder God: A Popular Deity’s Criticism of the Governmental Authority in the Wake of the Ansei Edo Earthquake in Catfish Prints. Arts, 14(2), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14020038