The Artistic and Ideological Framework of Funerary and Mourning Ceremonies for Polish Monarchs in the 16th Century: A Study on Reconstructing the Visual Aspects of Funeral Rites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Evolution of the Funeral Rituals of the Kings of Poland from the Late 14th Century to the Early 16th Century

3. Mourning Ceremonies Following the Deaths of Polish Kings in the 16th Century

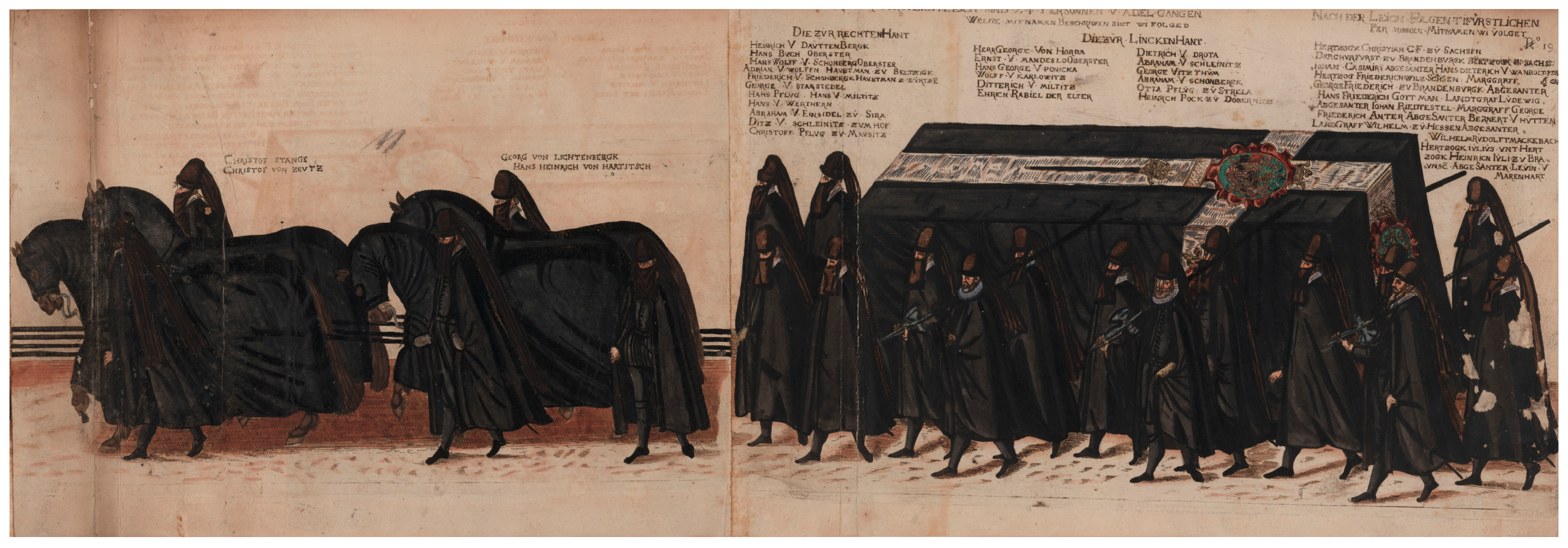

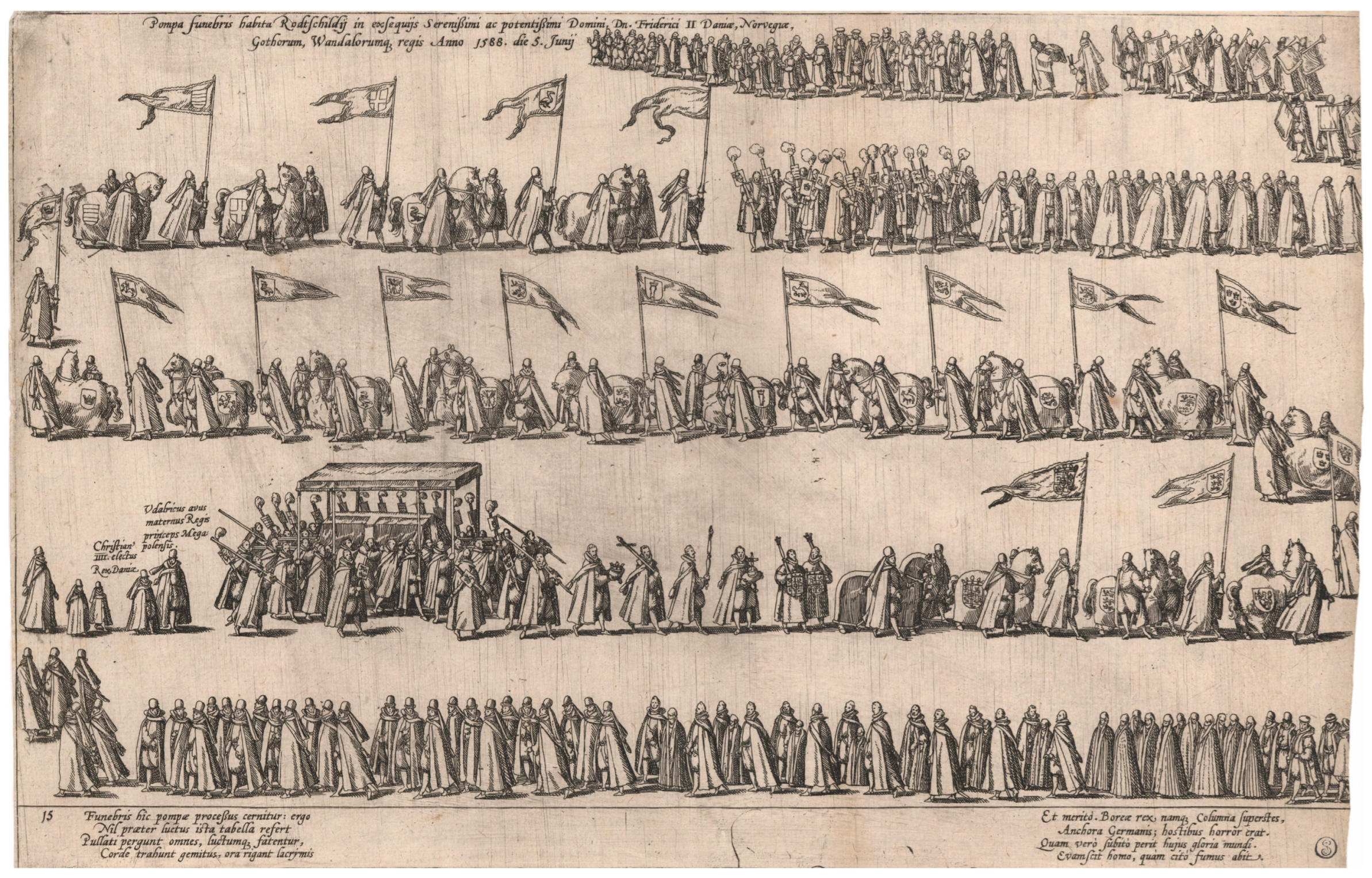

4. The Funerals of the Last Two Jagiellons in 1548 and 1574, and of Stephen Báthory in 1588

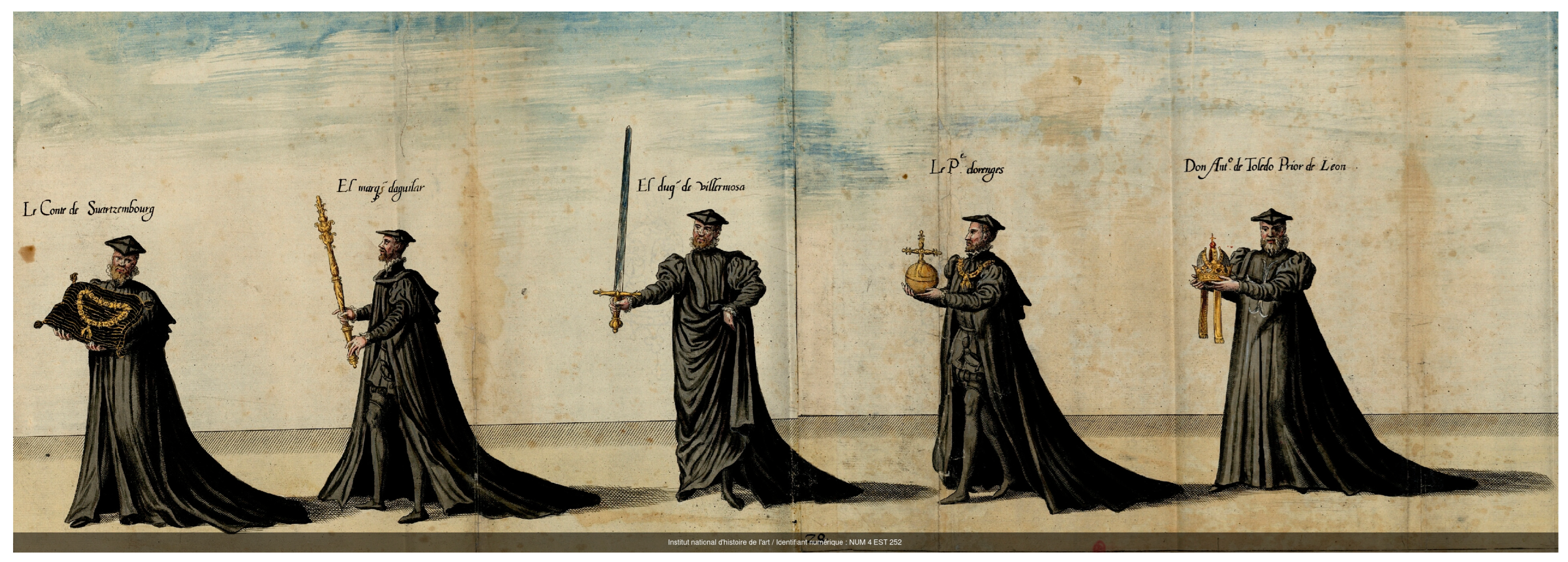

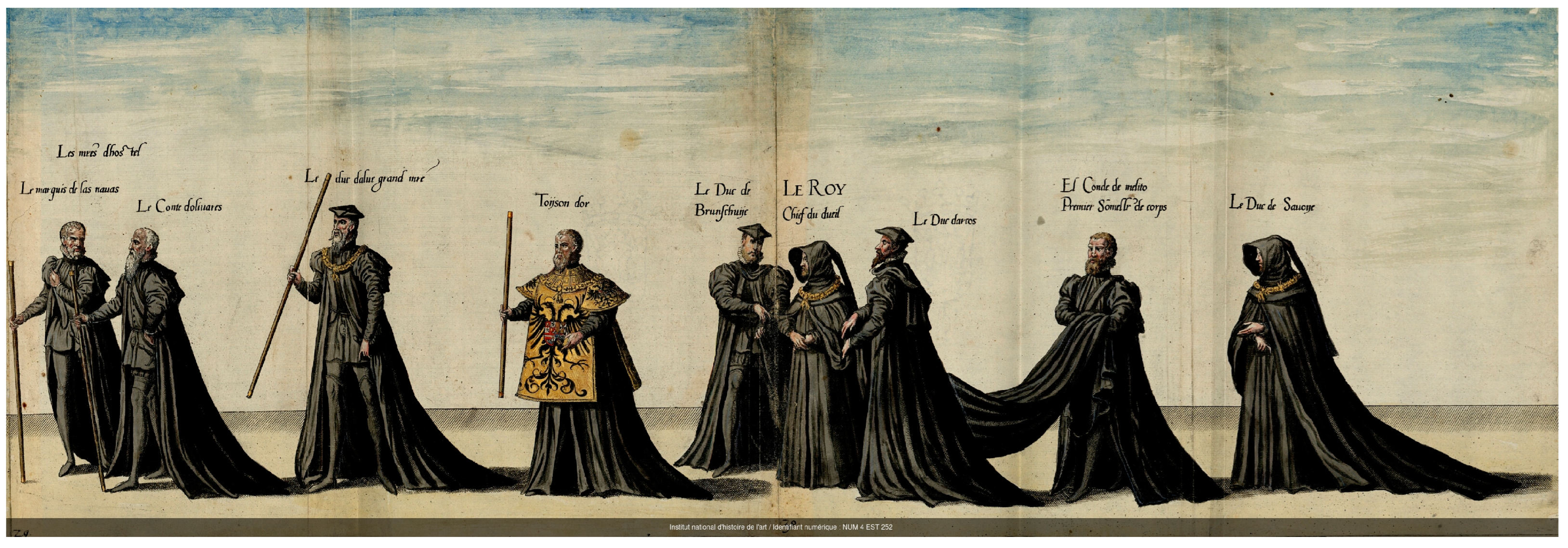

5. Funeral Ceremonies for the Last Two Jagiellonians Held Outside Poland

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The predecessors of Władysław II Jagiełło, with the exception of Louis of Hungary, all died in Kraków: Władysław I Łokietek (1333), Kazimierz III the Great (1370), and Jadwiga (1399). |

| 2 | Maximilian I’s second wife, Bianca Maria, was the sister of Bona Sforza’s father, Gian Galeazzo. Meanwhile, the daughter of Vladislaus II of Hungary, Anna, married Maximilian’s grandson, Ferdinand I, later emperor and the father of Sigismund Augustus’s first wife, Elisabeth of Habsburg. |

| 3 | Anna Jagiellon was the daughter of Sigismund I the Old and Bona Sforza and the younger sister of Sigismund II Augustus. On December 15, 1575, she became the King of Poland, and on May 1, 1576, she married the Prince of Transylvania, Stephen Báthory. |

| 4 | During the funeral of Sigismund II Augustus, due to the absence of his successor, the banner was taken up by his sister, Anna Jagiellon. |

References

Primary Sources

(Bretschneider 1586) Bretschneider, Daniel. 1586. Proces und Ordnung des Begenknus: Warhafftige Abcontrafactur des […] Herrn Augusti Hertzogen zu Sachssen […] Cörper oder Leiche […] anno 1586 zu Abend […] zu Dresten durch Chrisdum […] abgefordert. Available online: https://digital.slub-dresden.de/werkansicht/dlf/13463/1 (accessed on 6 December 2024).(Ceremonie 1830) Ceremonie przy prowadzeniu ciała [Zygmunta Augusta] Je[go] Kro[la] M[ości] z Tykocina do pogrzebu tym sposobem są odprawowanie. In Pamiętnik Sandomierski. Warszawa, pp. 441–47. Available online: https://bcpw.bg.pw.edu.pl/dlibra/publication/712/edition/12921/content (accessed on 6 December 2024).(Franconius 1548) Franconius, Matthias. 1548. Bericht über den christlichen Abschied aus diesem Leben und dem Begräbnis des Herrn Sigismund, König von Polen. Kraków. Available online: https://polona.pl/preview/f326ee2b-d472-4f72-9db0-4174f1ce582e (accessed on 6 December 2024).(Gołąb 1916) Gołąb, Julian. 1916. Pogrzeb króla Zygmunta Starego. In Dwunaste sprawozdanie dyrekcji C.K.II. Wyższej Szkoły Realnej w Krakowie za rok 1916. Kraków: Nakładem Funduszu Naukowego, pp. 3–43. Available online: https://pbc.rzeszow.pl/dlibra/publication/4515/edition/4149 (accessed on 6 December 2024).(Hannewald 1566) Hannewald, Bartholomaeus. 1566. Parentalia Divo Ferdinando Caesari Augusto […] Maximiliano Imperatore Etc. Ferdinando Et Carolo Serenissimis Archiducibus Austriae Fratribus […] persoluta Viennae. Augsburg. Available online: https://bibliotheque-numerique.inha.fr/collection/item/16457-parentalia-divo-ferdinando-caesari-augusto-patri-patriae-persoluta-viennae (accessed on 6 December 2024).(Jana Długosza 2009) Jana Długosza roczniki czyli kroniki sławnego Królestwa Polskiego, ks. 11, ks. 12, 1431–1444. Edited by Krzysztof Baczkowski et al. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN. Available online: https://polona2.pl/item/jana-dlugosza-roczniki-czyli-kroniki-slawnego-krolestwa-polskiego-ks-11-ks-12,MzgzNDc5MTI/6/#info (accessed on 6 December 2024).(Kurze 1588) Kurze Beschreibung der Zeremonien welche auf dem Begräbnis von König Stephan gehalten worden sind. Królewiec. Available online: https://polona.pl/preview/a66b32eb-b072-4b3e-8663-fe72a394f21d (accessed on 6 December 2024).(La magnifique 1559) La magnifique. 1559. La magnifique et sumtueuse pompe funèbre faite en la ville de Bruxelles, le XXIX. jour du mois de décembre, MDLVIII aux obsèques de l’empereur Charles V de tresdigne mémoire icy representee par ordre, et figures, selon les mysteres d’icelle. Antwerpen. Available online: https://bibliotheque-numerique.inha.fr/collection/item/15442-la-pompe-funebre-de-charles-quint?offset=3 (accessed on 6 December 2024).(La pompa 1574) La pompa ed ordine tenuto nelle esequie di Sigismondo Augusto, re di Polonia. Roma.(Kronika 1930) Kronika mieszczanina krakowskiego z lat 1575–1595. Edited by Henryk Barycz. Kraków.(Martiale 1574) Martiale, Avanzo. 1574. Le pietose esseqie et sontuose pompe funerali che sono state fatte nuovamente nelle citta di Cracovia per la morte del serenissimi Sigismondo Augusto re di Polonia. Venezia.(MNK, Bibl. Czart.) Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie, Biblioteka Książąt Czartoryskich, (TN) Teki Naruszewicza 66.(Niemcewicz 1839) Niemcewicz, Julian U. 1839. Zbiór pamiętników historycznych o dawnej Polsce. Lipsk: Nakładem i drukiem Breitkopfa i Haertela, vol. 4. Available online: https://polona.pl/item-view/b6d11023-8083-4120-8df5-7979d64c5db4?page=6 (accessed on 6 December 2024).(PAN, BK) Polska Akademia Nauk, Biblioteka Kórnicka, ms 241.(Pogrzeb 1839) Pogrzeb króla Stefana Batorego. Porządek i ceremonie przy wyprowadzeniu z Grodna ciała Króla Jegomości, i w drodze do Warszawy, a z stamtąd do Łobzowa nad Krakowem, potem do kościoła wielkiego zamku krakowskiego zachowane i pilnie czynione. In. Niemcewicz, Julian U. Zbiór pamiętników historycznych o dawnej Polsce. Lipsk: Nakładem i drukiem Breitkopfa i Haertela, vol. 2, pp. 322–29. Available online: https://www.wbc.poznan.pl/dlibra/publication/edition/52053/content (accessed on 6 December 2024).(Przezdziecki 1868) Przezdziecki, Aleksander. 1868. Jagiellonki polskie w XVI. wieku. Kraków: Drukarnia Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, vol. 4. Available online: https://www.wbc.poznan.pl/dlibra/publication/1933/edition/3241 (accessed on 6 December 2024).(Ruiz de Moros 1548) Ruiz de Moros, Pedro. 1548. Historia funebris in obitu Sigismundi, Sarmatiarum regis et ad Sigismundum Augustum filium admonition. Kraków. Available online: https://polona.pl/preview/b830a938-9a94-4456-a901-1e7914c61421 (accessed on 6 December 2024).(ÖNB) Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Wien (Austrian National Library, Vienna), cod. 7566 Descriptio germanica pompae funebris in obitum Caroli V. Imperatoris 24 et 25 februarii 1559 […]. Augsburg.(Testament 1975) Testament Zygmunta Augusta. Edited by Antoni Franaszek, Olga Łaszczyńska and Stanisław E. Nahlik. Kraków: Państwowe Zbiory Sztuki na Wawelu.(ZNiO) Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich we Wrocławiu, ms 9789/II.Secondary Sources

- Aurnhammer, Achim, and Friedrich Däuble. 1980/1981. Die Exequien für Kaiser Karl V. in Augsburg, Brüssel und Bologna. Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 62/63: 101–57. Available online: https://d-nb.info/1123480567/34 (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Borkowska, Urszula. 1986. Ceremoniał pogrzebowy królów polskich w XIV–XVIII w. In Państwo. Kościół. Niepodległość. Edited by Jan Skarbek. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe Katolicki Uniwersytet Lubelski, pp. 133–60. [Google Scholar]

- Chrościcki, Juliusz A. 1974. Pompa funebris. Z dziejów kultury staropolskiej. Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. Available online: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/chroscicki1974 (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Der Tod des Mächtigen. 1997. Der Tod des Mächtigen. Kult und Kultur des Todes spätmittelalterlicher Herrscher. Edited by Lothar Kolmer. Paderborn-München-Wien-Zürich: Ferdinand Schöningh. Available online: https://digi20.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/fs1/object/display/bsb00044968_00001.html (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Fałkowski, Wojciech. 2009a. Majestat zmarłego króla–pogrzeb Zygmunta Augusta. In Polska i Europa w dobie nowożytnej: Prace naukowe dedykowane Profesorowi Juliuszowi A. Chrościckiemu. Edited by Tadeusz Bernatowicz. Warszawa: Arx Regia, Ośrodek Wydawniczy Zamku Królewskiego, pp. 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Fałkowski, Wojciech. 2009b. Dwa pogrzeby Kazimierza Wielkiego–znaczenie rytuału. Kwartalnik Historyczny 116: 55–74. Available online: https://rcin.org.pl/dlibra/doccontent?id=6589 (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Ferenc, Marek. 1999. Rola i udział dworu w ceremonii pogrzebowej Zygmunta Augusta. In Theatrum ceremoniale na dworze książąt i królów polskich. Edited by Mariusz Markiewicz and Ryszard Skowron. Kraków: Zamek Królewski na Wawelu, pp. 113–22. Available online: https://jbc.bj.uj.edu.pl/dlibra/publication/947590/edition/927693?language=pl (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- French Ceremonial. 2007. French Ceremonial Entries in the Sixteenth Century: Event, Image, Text. Edited by Nicolas Russel and Hélène Visentin. Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Hengerer, Mark. 2007. The Funerals of the Habsburg Emperors in the Eighteenth Century. In Monarchy and Religion: The Transformation of Royal Culture in Eighteenth-Century Europe. Edited by Michael Schaich. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 367–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hennel-Brenasikowa, Maria. 1996. Czarno-białe tkaniny Zygmunta Augusta. Studia Waweliana 5: 33–42. Available online: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/studia_waweliana1996/0035/image,info,thumbs (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Janowski, Piotr Józef. 2015a. Oprawa artystyczno-ideowa uroczystości pogrzebowych Zygmunta Starego. In Nowożytnicze Zeszyty Historyczne, z. 7: Król i jego poddani w Rzeczypospolitej polsko-litewskiej XVI–XVIII w. Edited by Weronika Czaja. Kraków: Koło Naukowe Historyków Studentów Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, pp. 66–87. [Google Scholar]

- Janowski, Piotr Józef. 2015b. Oprawa artystyczno-ideowa pogrzebu Stefana Batorego. Barok. Historia-Literatura-Sztuka 43: 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Janowski, Piotr Józef. 2022. Ceremonie żałobne po śmierci ostatnich dwóch Jagiellonów zorganizowane poza granicami Polski. In Zygmunt II August i kultura jego czasów. W pięćsetlecie urodzin ostatniego Jagiellona na polsko-litewskim tronie. Edited by Radosław Rusnak. Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, pp. 371–92. [Google Scholar]

- Johannsen, Birgitte B. 2014. Ars moriendi more regio: Royal Death in Sixteenth Century Denmark. Journal of Early Modern Christianity 1: 51–90. Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/jemc-2014-0006/html?srsltid=AfmBOorl1w02-hYnNR815msunXmNc1jaQuTQkOg7GknC5Kx8O5wuntep (accessed on 6 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Kolendo-Korczak, Katarzyna. 2013. Sarkofag Stefana Batorego i jego wzory graficzne, czyli Res gestae regi Stephani. Biuletyn Historii Sztuki 75: 641–70. Available online: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/bhs2013/0647/image,info (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Kolendo-Korczak, Katarzyna, and Agnieszka Trzos. 2018. Tin sarcophagi of Sigismund Augustus and Anna Jagiellon. Conservation and restoration, history, ideological meaning. Historical Monument’s Preservation 2: 61–106. Available online: https://cejsh.icm.edu.pl/cejsh/element/bwmeta1.element.desklight-8c5234f0-7f37-40b7-81c7-92647355892f (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Kucia, Dariusz. 1999. Idea wyobrażania zmarłego władcy w ceremoniale pogrzebowym królów Polski od XIV do XVII wieku na tle ceremonii Europy chrześcijańskiej. In Theatrum ceremoniale na dworze książąt i królów polskich. Edited by Mariusz Markiewicz and Ryszard Skowron. Kraków: Zamek Królewski na Wawelu, pp. 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Les funérailles. 2012. Les funérailles princières en Europe, XVIe–XVIIIe siècle. Le grand théâtre de la mort. Edited by Juliusz A. Chrościcki, Mark Hengerer and Gérard Sabatier. Versailles: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, Centre de recherche du Château de Versailles, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Les funérailles. 2013. Les funérailles princières en Europe, XVIe–XVIIIe siècle. Apothéoses monumentales. Edited by Juliusz A. Chrościcki, Mark Hengerer and Gérard Sabatier. Versailles: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, Centre de recherche du Château de Versailles, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Les funérailles. 2015. Les funérailles princières en Europe, XVIe–XVIIIe siècle. Le deuil, la mémoire, la politique. Edited by Juliusz A. Chrościcki, Mark Hengerer and Gérard Sabatier. Versailles: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, Centre de recherche du Château de Versailles, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier, Gérard. 2012. Les funérailles royales francaises, XVI–XVIII siècle. In Les funérailles princières en Europe, XVIe–XVIIIe siècle. Apothéoses monumentales. Edited by Juliusz A. Chrościcki, Mark Hengerer and Gérard Sabatier. Versailles: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, Centre de recherche du Château de Versailles, vol. 2, pp. 17–47. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, Peter. 1997. Sterben–Tod–Leichenbegängnis Kaiser Maximilians I. In Der Tod des Mächtigen. Kult und Kultur des Todes spätmittelalterlicher Herrscher. Edited by Lothar Kolmer. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, pp. 185–215. [Google Scholar]

- Schrader, Stephanie. 1998. ’Greater than Ever He Was’ Ritual and Power in Charles V’s 1558 Funeral Procession. Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 49: 69–94. Available online: https://brill.com/view/journals/nkjo/49/1/article-p69_5.xml (accessed on 6 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Schraven, Minou. 2006. Festive Funerals. Funeral “Apparati” in Early Modern Italy Particulary in Rome. Ph.D. thesis, Universiteit Groningen, Groningen. [Google Scholar]

- Schraven, Minou. 2014. Festive Funerals in Early Modern Italy: The Art and Culture of Conspicuous Commemoration. Abingdon-on-Thames: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Sulewska, Renata. 2019. Warszawskie uroczystości pogrzebowe królów i ich rodzin w XVI i XVII wieku. Ceremoniał, przestrzeń, oprawa plastyczna. Rocznik Historii Sztuki 44: 179–204. Available online: https://journals.pan.pl/dlibra/publication/131208/edition/114606/content (accessed on 6 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Szabó, Péter. 1998. Temetkezési kultúránk újabban felfedezett forrásai elé. In Irodalomtörténeti közlemények 102: 744–59. Available online: https://epa.oszk.hu/00000/00001/00007/szabo.htm (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Szmydki, Ryszard. 2022. Arrasy heraldyczno-monogramowe króla Zygmunta Augusta. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Neriton. [Google Scholar]

- Szmydki, Ryszard, and Piotr Józef Janowski. 2022. Ze studiów nad zakupami tekstyliów dla króla Zygmunta Augusta po roku 1560. In Zygmunt II August i kultura jego czasów. W pięćsetlecie urodzin ostatniego Jagiellona na polsko-litewskim tronie. Edited by Radosław Rusnak. Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, pp. 154–71. [Google Scholar]

- Śliwowska, Anna. 2008. Uroczyste wjazdy monarsze do Wrocławia w latach 1527–1620. Wrocław: Oficyna Wydawnicza ATUT. [Google Scholar]

- Śmierć. 2020. Śmierć, pogrzeb i upamiętnienie władców w dawnej Polsce. Edited by Hanna Rafura, Patrycja Szwedo, Barbara Świadek, Marek Walczak and Piotr Węcowski. Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Śnieżyńska-Stolot, Ewa. 1975. Dworski ceremoniał pogrzebowy królów polskich w XIV wieku. In Sztuka i ideologia w XIV wieku. Edited by Piotr Skubiszewski. Warszawa: Polska Akademia Nauk, pp. 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Tuchołka-Włodarska, Barbara. 1986. Z badań nad sarkofagiem króla Zygmunta Augusta. Biuletyn Historii Sztuki 48: 221–45. Available online: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/bhs1986/0275/image,info (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Weiss-Krejci, Estella. 2008. Unusual Life, Unusual Death and the Fate of the Corpse: A Case Study from Dynastic Europe. In Deviant Burial in the Archaeological Record. Edited by Eileen M. Murphy. Oxford: Oxbow, vol. 2, pp. 169–90. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1cd0ptg (accessed on 6 December 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Janowski, P.J. The Artistic and Ideological Framework of Funerary and Mourning Ceremonies for Polish Monarchs in the 16th Century: A Study on Reconstructing the Visual Aspects of Funeral Rites. Arts 2025, 14, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14010010

Janowski PJ. The Artistic and Ideological Framework of Funerary and Mourning Ceremonies for Polish Monarchs in the 16th Century: A Study on Reconstructing the Visual Aspects of Funeral Rites. Arts. 2025; 14(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleJanowski, Piotr Józef. 2025. "The Artistic and Ideological Framework of Funerary and Mourning Ceremonies for Polish Monarchs in the 16th Century: A Study on Reconstructing the Visual Aspects of Funeral Rites" Arts 14, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14010010

APA StyleJanowski, P. J. (2025). The Artistic and Ideological Framework of Funerary and Mourning Ceremonies for Polish Monarchs in the 16th Century: A Study on Reconstructing the Visual Aspects of Funeral Rites. Arts, 14(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14010010