The Spacetimes of the Scythian Dead: Rethinking Burial Mounds, Visibility, and Social Action in the Eurasian Iron Age and Beyond

Abstract

A body’s symbolic effectiveness does not depend on it standing for one particular thing, however, for among the most important properties of bodies, especially dead ones, is their ambiguity, multivocality, or polysemy. Remains are concrete, yet protean; they do not have a single meaning but are open to different readings.

1. Introduction

Tumuli were intended to function as highly visible communal monuments. They advertised the seniority and importance of the lineages associated with the late Iron Age populations that erected them. Their conspicuous location along major routes of transportation (often on terraces clearly visible from a considerable distance), and their additional demarcation by means of stone rings and stelae, supports this interpretation.

2. Reviewing the Study of Burial Mounds

In sum, an intersubjective spacetime is a multidimensional, symbolic order and process–a spacetime of self-other relations constituted in terms of and by means of specific types of practice. A given type of act or practice forms a spatiotemporal process, a particular mode of spacetime. Defined abstractly, the specifically spatiotemporal features of this process consist of relations, such as those of distance, location (including geographical domains of space), and directionality; duration or continuance, succession, timing (including temporal coordination and relative speed of activities), and so forth.

3. Epistemology of Eurasian Iron Age Burial Mounds

3.1. The Spacetimes of Individual Tumuli: Single and/or Proximate Instances

3.2. Beyond the Proximate: Engagements with Scythian Period Tumuli as Visual Culture

They become more free and flexible, their language renews itself by incorporating extraliterary heteroglossia and the “novelistic” layers of literary language, they become dialogized, permeated with laughter, irony, humor, elements of self-parody and finally–this is the most important thing–the novel inserts into these other genres an indeterminacy, a certain semantic openendedness, a living contact with unfinished, still-evolving contemporary reality (the openended present).

3.2.1. Travel, Visibility, and the Eurasian Iron Age Burial Mounds

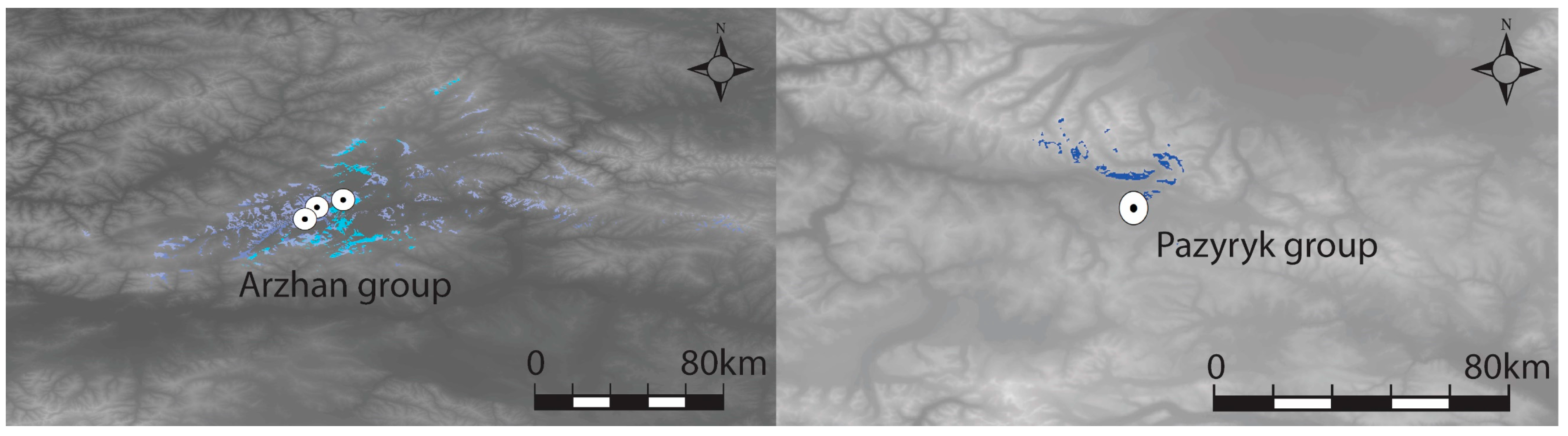

The Arzhan Group and Pazyryk Groups

The Issyk, Zhun Tobe, and Taksai Groups

Kelermes Mound Group

Scythian Royal Mounds of the Lower Dnipro River Region of Central Ukraine

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnold, Bettina. 1995. The Material Culture of Social Structure: Rank and Status in Early Iron Age Europe. In Celtic Chiefdom, Celtic State. Edited by Bettina Arnold and D. Blair Gibson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Bettina. 2002. A Landscape of Ancestors: The Space and Place of Death in Iron Age West-Central Europe. In The Space and Place of Death. Edited by Helaine Silverman and David Small. Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, vol. 11, pp. 130–43. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Bettina. 2003. Landscapes of Ancestors: Early Iron Age Hillforts and their Mound Cemeteries. Expeditions 45: 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Bettina. 2010. Memory Maps: The Mnemonics of Central European Iron Age Burial Mounds. In Material Mnemonics: Everyday Memory in Prehistoric Europe. Edited by Katrina Lillios and Vasilis Tsamis. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 147–73. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Bettina. 2011. The Illusion of Power, The Power of Illusion: Ideology and the Concretization of Social Difference in Early Iron Age Europe. In Ideologies in Archaeology. Edited by Reinhard Bernbeck and Randall McGuire. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, pp. 151–72. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Bettina, and Matthew Murray. forthcoming. A Landscape of Ancestors: Archaeological Investigations of Two Iron Age Burial Mounds in the Hohmichele Group, Baden-Württemburg. LAD Baden-Württemburg: Research and Reports on Prehistory and Early History in Baden-Württemburg. Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss Verlag.

- Bakhtin, Mikhail. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination. Translated by C. Emerson, and M. Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ballmer, Ariane. 2018. Burial Mound/Landscape Relations: Approaches Put Forward by European Prehistoric Archaeology. In Burial Mounds in Europe and Japan: Comparative and Contextual Perspectives. Edited by Thomas Knopf, Werner Steinhaus and Shin’ya Fukunaga. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 100–9. [Google Scholar]

- Barfield, Thomas. 2020. Supersize Me: Political Aspects of Monumental Tomb Building in Early Steppe Empires. In Masters of the Steppe: The Impact of the Scythians and Later Nomad Societies of Eurasia. Edited by Svetlana Pankova and St John Simpson. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Richard. 1977. Verbal Art as Performance. Prospect Heights: Waveland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bokovenko, Nikolay. 1995a. Tuva during the Scythian Period. In Nomads of the Eurasian Steppes in the Early Iron Age. Edited by Jeanine Davis-Kimball, Vasily Bashilov and Leonid Yablonsky. Berkeley: Zinat Press, pp. 265–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bokovenko, Nikolay. 1995b. Scythian Culture in the Altai Mountains. In Nomads of the Eurasian Steppes in the Early Iron Age. Edited by Jeanine Davis-Kimball, Vasily Bashilov and Leonid Yablonsky. Berkeley: Zinat Press, pp. 285–98. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, Barbara. 2019. Roman Tombs and the Art of Commemoration: Contextual Approaches to Funerary Customs in the Second Century CE. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boric, Dusan, and John Robb, eds. 2008. Past Bodies: Body-Centered Research in Archaeology. Oxford: Oxbow Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Richard. 1998. The Significance of Monuments: On the Shaping of Human Experience in the Neolithic and Bronze Age. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Branigan, Keith. 1998. The Nearness of You: Proximity and Distance in Early Minoan Funerary Behaviour. In Cemetery and Society in the Aegean Bronze Age. Edited by Keith Branigan. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, James. 1981. The Search for Rank in Prehistoric Burials. In The Archaeology of Death. Edited by Robert Chapman, Ian Kinnes and Klaus Randsborg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, James. 1995. On Mortuary Analysis–with Special Reference to the Saxe-Binford Research Program. In Regional Approaches to Mortuary Analysis. Edited by Lane A. Beck. New York: Plenum Press, pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Buikstra, Jane, and Douglas Charles. 1999. Centering the Ancestors: Cemeteries, Mounds, and Sacred Landscapes of the Ancient North American Midcontinent. In Archaeologies of Landscape: Contemporary Perspectives. Edited by Wendy Ashmore and A. Bernard Knapp. Malden: Blackwell Publishers, pp. 201–28. [Google Scholar]

- Caspari, Gino, Timur Sadykov, Jegor Blochinc, and Irka Hajdas. 2018. Tunnug 1 (Arzhan 0)–An Early Scythian Kurgan in Tuva Republic, Russia. Archaeological Research in Asia 15: 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, Robert. 1981. The Emergence of Formal Disposal Areas and the ‘Problem’ of Megalithic Tombs in Prehistoric Europe. In The Archaeology of Death. Edited by Robert Chapman, Ian Kinnes and Klaus Randsborg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, Robert. 1995. Ten Years After–Megaliths, Mortuary Practices, and the Territorial Model. In Regional Approaches to Mortuary Analysis. Edited by Lane A. Beck. New York: Plenum Press, pp. 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, Robert, Ian Kinnes, and Klaus Randsborg, eds. 1981. The Archaeology of Death. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chugunov, Konstantin. 2020. The Arzhan-2 ‘Royal’ Funerary-Commemorative Complex: Stages of Function and Internal Chronology. In Masters of the Steppe: The Impact of the Scythians and Later Nomad Societies of Eurasia. Edited by Svetlana Pankova and St John Simpson. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Dakouri-Hild, Anastasia, and Michael Boyd, eds. 2016. Staging Death: Funerary Performance, Architecture, and Landscape in the Aegean. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Daragan, Marina. 2013. Mounds from the Steppes of Ukraine: Spatial Analysis and Visualization Methods in GIS Technology. In Virtual Archaeology (Non-destructive Method Research, Modeling, and Reconstruction), Materials of the First International Conference, Hermitage Museum, June 4–6, 2012. Edited by Daria Yu. Hookk. St. Petersburg: State Hermitage Publishing House, pp. 76–85. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Daragan, Marina. 2016. The Use of GIS Technologies in Studying the Spatial and Time Concentration of Tumuli in the Scythian-Time Lower Dnieper Region. In Tumulus as Sema: Space, Politics, Culture, and Religion in the First Millennium BC. Edited by Oliver Henry and Ute Kelp. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 669–85. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, Kate. 2021. Everyday Cosmopolitianisms: Living the Silk Road in Medieval Armenia. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galanina, Lyudmila. 1997. Kelermes Kurgan. Moscow: Paleograph. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Giles, Melanie. 2013. Preserving the Body. In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Death and Burial. Edited by Sarah Tarlow and Liz Nilsson Stutz. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 475–96. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1959. Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, Lynne. 1981. One-Dimensional Archaeology and Multi-Dimensional People: Spatial Organization and Mortuary Analysis. In The Archaeology of Death. Edited by Robert Chapman, Ian Kinnes and Klaus Randsborg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Gramsch, Alexander. 2013. Treating Bodies: Transformative and Communicative Practices. In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Death and Burial. Edited by Sarah Tarlow and Liz Nilsson Stutz. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 459–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hanks, Bryan. 2002. The Eurasian Steppe ‘Nomadic World’ of the First Millennium BC: Inherent Problems within the Study of Iron Age Nomadic Groups. In Ancient Interactions: East and West in Eurasia. Edited by Katherine Boyle, Colin Renfrew and Marsha Levine. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research Monographs, University of Cambridge, pp. 183–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, Ian. 1999. The Archaeological Process: An Introduction. London: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Inomata, Takeshi, and Lawrence Coben, eds. 2006. Archaeology of Performance: Theaters of Power, Community, and Politics. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, James. 2009. Beyond Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc: An Investigation into Prehistoric Technologies, Mortuary Sites, and Engendered Social Practices. In Que(e)rying Archaeology: Proceedings of the Thirty Seventh Annual Chacmool Conference, University of Calgary. Edited by Susan Terendy, Natasha Lyons and Michelle Janse-Smekal. Calgary: Archaeological Association, University of Calgary, pp. 187–95. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, James. 2016. Assembling Identities-In-Death: Miniaturizing Identity and the Remarkable in Iron Age Mortuary Practices of West-Central Europe. In Incomplete Archaeologies: Assembling Knowledge in the Past and Present. Edited by Emily Miller Bonney, Kathryn J. Franklin and James A. Johnson. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, James. 2020. Trade, Community, and Labour in the Pontic Iron Age Forest-Steppe Region, 700–200 BC. In Masters of the Steppe: The Impact of the Scythians and Later Nomad Societies of Eurasia. Edited by Svetlana Pankova and St John Simpson. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 198–209. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, James, and Seth Schneider. 2013. Making a Spectacle? Monumentality and Performative Time in the Mortuary Spaces of Early Iron Age Southwest Germany. In Place as Material Culture: Objects, Geographies, and the Construction of Time. Edited by Dragos Gheorghiu and George Nash. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Press, pp. 231–57. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, James. forthcoming. Mobility and Gender in the Construction of Status in “Scythian” Mortuary Practices. In Mobilities and Migrations in the Making of Later Eurasian Prehistory. Edited by James A. Johnson, Guus Kroonen and Rune Iversen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Joyce, Rosemary. 2004. Unintended Consequences? Monumentality as a Novel Experience in Formative Mesoamerica. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 11: 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koryakova, Lyudmila. 1996. Social Trends in Temperate Eurasia during the Second and First Millennia BC. Journal of European Archaeology 4: 243–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laneri, Nico, ed. 2008. Performing Death: Social Analyses of Funerary Traditions in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean. Chicago: The Oriental Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Lillios, Katrina, and Vasilis Tsamis, eds. 2010. Material Mnemonics: Everyday Memory in Prehistoric Europe. Oxford: Oxbow Books. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Ian. 1987. Burial and Ancient Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Ian. 1991. The Archaeology of Ancestors: The Saxe/Goldstein Hypothesis Revisited. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 1: 147–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Ian. 1992. Death-Ritual and Social Structure in Classical Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mozolevskiy, Boris, and Sergei Polin. 2005. Kurgans of Scythian Gerros of 4th Century B.C. (Babina, Vodyana and Soboleva Mohily). Kyiv: Stylos Publishing. (In Ukrainian) [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Nancy. 1986. The Fame of Gawa: A Symbolic Study of Value Transformation in a Massim (Papua New Guinea) Society. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ochir-Goryaeva, Maria. 2014. Culture of the Nomads on the Lower Volga during the Scythian Time: General and Especial. Volga Archaeology 4: 106–31. [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotopoulos, Anastasios, and Diana E. Santo, eds. 2019. Articulate Necrographies: Comparative Perspectives on the Voices and Silences of the Dead. New York: Berghahn. [Google Scholar]

- Parker Pearson, Mike. 1993. The Powerful Dead: Relationships between the Living and the Dead. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 3: 203–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker Pearson, Mike. 2005. The Archaeology of Death and Burial. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parzinger, Hermann. 2004. The Scythians. Munich: C.H. Beck. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Parzinger, Hermann. 2006. The Early Peoples of Eurasia: From the Neolithic to the Middle Ages. Munich: C.H. Beck. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Parzinger, Hermann. 2017. Burial Mounds of Scythian Elites in the Eurasian Steppe: New Discoveries. Journal of the British Academy 5: 331–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, Mike, and Michael Shanks. 2001. Theatre/Archaeology. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Polin, Sergei, and Marina Daragan. 2020. The Royal Scythian Alexandropol Kurgan Based on New Research Data of 2004–9. In Masters of the Steppe: The Impact of the Scythians and Later Nomad Societies of Eurasia. Edited by Svetlana Pankova and St John Simpson. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 444–71. [Google Scholar]

- Polin, Sergei, Marina Daragan, and Ksenila Bondar. 2020. New Investigations of Scythian Kurgans and Their Periphery in the Lower Dnieper Region: Non-destructive Measurements and Archaeological Proof. In Masters of the Steppe: The Impact of the Scythians and Later Nomad Societies of Eurasia. Edited by Svetlana Pankova and St John Simpson. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 472–82. [Google Scholar]

- Renfrew, Colin, and Paul Bahn. 2008. Archaeology: Theories, Methods, and Practice, 5th ed. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Rolle, Renate. 1979. Death Cult of the Scythians. Part I and Part II, Das Steppengebiet, Vorgeschichtliche Forschungen. Berlin: De Gruyter, vol. 18. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Rolle, Renate. 1989. The World of the Scythians, trans. F.G. Walls. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rolle, Renate. 2011. The Scythians: Between Mobility, Tomb Architecture, and Early Urban Structures. In The Barbarians of Ancient Europe: Realities and Interactions. Edited by L. Bonfante. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 107–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinson, Karen, and Katheryn Linduff. 2024. A Distinct Form of Socio-Political and Economic Organization in the Pazyryk Culture. Arts 13: 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudenko, Sergei. 1970. Frozen Tombs of Siberia: The Pazyryk Burials of Iron Age Horsemen. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ryabkoba, Tatyana. 2020. The Formation of the Early Scythian Cultural Complex of the Kelermes Cemetery in the Kuban Region of the North Caucasus. In Masters of the Steppe: The Impact of the Scythians and Later Nomad Societies of Eurasia. Edited by Svetlana Pankova and St John Simpson. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 483–97. [Google Scholar]

- Satubaldin, Abay, Sergei Yarygin, Aude Mongiatti, Daniel O’Flynn, and Janet Lang. 2020. The Results of New Scientific Analyses of Gold Bracelets from Taksai-1 and an Iron Sword from Issyk in the National Museum of the Republic of Kazakhstan. In Masters of the Steppe: The Impact of the Scythians and Later Nomad Societies of Eurasia. Edited by Svetlana Pankova and St John Simpson. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 498–508. [Google Scholar]

- Saxe, Arthur. 1970. Social Dimensions of Mortuary Practices. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Seth. 2003. Ancestor Veneration and Ceramic Curation: An Analysis from Speckhau Mound 17, Southwest Germany. Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee County, WI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Severi, Carlos. 2015. The Chimera Principle: An Anthropology of Memory and Imagination. Translated by J. Lloyd. Chicago: HAU Books. [Google Scholar]

- Šmejda, Ladislav, ed. 2006. Archaeology of Burial Mounds. Plzen: University of West Bohemia, Faculty of Philosophy and Arts, Department of Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhaus, Thomas, Werner Knopf, and Shin’ya Fukunaga, eds. 2018. Burial Mounds in Europe and Japan: Comparative and Contextual Perspectives. Oxford: Archaeopress,. [Google Scholar]

- Sturken, Marita, and Lisa Cartwright. 2001. Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tainter, Joseph. 1975. Social Inference and Mortuary Practices: An Experiment in Numerical Classification. World Archaeology 7: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilley, Chris. 1991. Material Culture and Text. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Toynbee, Jocelyn. 1971. Death and Burial in the Roman World. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Verdery, Katherine. 1999. The Political Lives of Dead Bodies: Reburial and Postsocialist Change. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Voutsaki, Sofia. 1998. Mortuary Evidence, Symbolic Meanings, and Social Change: A Comparison between Messenia and the Argolid in the Mycenean Period. In Cemetery and Society in the Aegean Bronze Age. Edited by Keith Branigan. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Yablonsky, Leonid. 2000. “Scythian Triad” and “Scythian World”. In Kurgans, Ritual Sites, and Settlements: Eurasian Bronze and Iron Ages. Edited by Jeanine Davis-Kimball, Eileen Murphy, Ludmila Koryakova and Leonid Yablonsky. BAR International Series 890; Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yablonsky, Leonid, and Vladimir Bashilov. 2000. Some Current Problems Concerning the History of Early Iron Age Eurasian Steppe Nomadic Societies. In Kurgans, Ritual Sites, Settlements: Eurasian Bronze and Iron Ages. Edited by Jeanine Davis-Kimball, Eileen Murphy, Ludmila Koryakova and Leonid Yablonsky. BAR International Series 890; Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 9–12. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Johnson, J.A. The Spacetimes of the Scythian Dead: Rethinking Burial Mounds, Visibility, and Social Action in the Eurasian Iron Age and Beyond. Arts 2024, 13, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13030087

Johnson JA. The Spacetimes of the Scythian Dead: Rethinking Burial Mounds, Visibility, and Social Action in the Eurasian Iron Age and Beyond. Arts. 2024; 13(3):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13030087

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohnson, James A. 2024. "The Spacetimes of the Scythian Dead: Rethinking Burial Mounds, Visibility, and Social Action in the Eurasian Iron Age and Beyond" Arts 13, no. 3: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13030087

APA StyleJohnson, J. A. (2024). The Spacetimes of the Scythian Dead: Rethinking Burial Mounds, Visibility, and Social Action in the Eurasian Iron Age and Beyond. Arts, 13(3), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13030087