Abstract

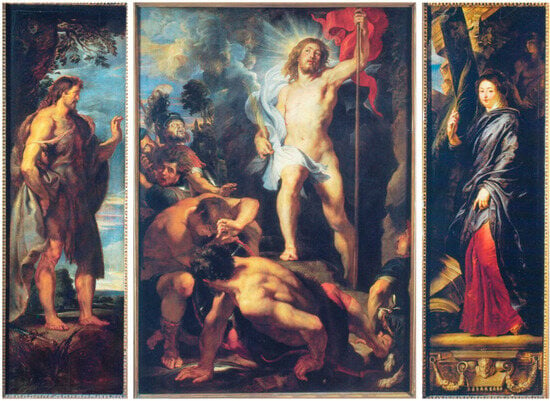

On behalf of the Catholic Church, the Council of Trent (1545–1563) confirmed the usefulness of religious images and multisensory worship practices for engaging the bodies and the minds of congregants, and for moving pious devotees to empathize with Christ. In the center panel of the Rockox Epitaph (c. 1613–1615), a funerary triptych commissioned by the Antwerp mayor Nicolaas Rockox (1560–1640) and his wife Adriana Perez (1568–1619) to hang over their tomb, Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) paints an awe-inspiring, hopeful image of the Risen Lord that alludes to the promise of humankind’s corporeal resurrection at the Last Judgment. In the wings, Rockox and Perez demonstrate affective worship with prayer aids and welcome onlookers to gaze upon Christ’s renewed body. Rubens’s juxtaposition of the eternal, incorruptible body of Jesus alongside five mortal figures—the two patrons and the three apostles, Peter, Paul, and John—prompted living viewers to meditate on their relationship with God, to compare their bodies with those depicted, and to contemplate their own embodiment and mortality. Ultimately, the idealized body of Christ reminds faithful audiences of both the corporeal renewal and the spiritual salvation made possible through Jesus’s death and resurrection.

Keywords:

Peter Paul Rubens; Nicolaas Rockox; Adriana Perez; epitaph; resurrection; Jesuits; heart; Ages of Man 1. Introduction

The immaculate, resurrected body of Christ is the subject of the Rockox Epitaph (Figure 1), a triptych painted by the Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) between 1613 and 1615. Epitaph paintings, designed to hang over the tombs of their patrons, are funerary monuments that commemorate the dead.1 Risen from the grave and glowing with divine light, Rubens’s life-sized, bare-chested Jesus displays his muscular body and wounded palms to three astonished apostles, who marvel at the miracle they are witnessing. Inspired by Caravaggio, the artist sets the four figures against a sparse, dark background and employs theatrical lighting to focus the viewer’s attention on the radiant body of Christ.2 Brightly illuminated and conspicuously unmarred—missing the canonical side wound—Jesus’s renewed body practically pulsates with life: his cheeks are flushed, tendons flex in his forearms, and a network of blue veins traces the path of blood back to his beating heart.

Figure 1.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Rockox Epitaph (open): (a) Portrait of Nicolaas Rockox, (b) Resurrected Christ appearing to apostles, (c) Portrait of Adriana Perez, c. 1613–1615, oil on panel, 143 × 123 cm (center), 146 × 55 cm (wings), Collection KMSKA-Flemish Community, Antwerp, inv. no. 308, 307, and 310.

Rubens employs numerous artistic techniques to encourage the viewer to look at the body of Christ. The translucent white loincloth around Jesus’s hips and the voluminous crimson drapery framing his torso direct the beholder’s gaze to that divine body. Simultaneously, the vibrant red textile distinguishes Christ from his earthly companions, who wear muted shades of blue that better blend into the dark background. In contrast to Jesus’s carefully modeled figure, the apostles’ bodies are both obscured and truncated. The youth in the foreground is reduced to a head, an arm, two hands, and a knee. Likewise, the elderly man next to him is little more than a head atop an amorphous green-blue sheet. In the background, the body of the middle-aged man is almost entirely shrouded in shadows—his shoulder is only visible because the light from Christ’s body shines on him. In this composition, the apostles are secondary figures. Note how Rubens crowds them together on the right to provide ample space for Jesus on the left.

Across the three interior panels of the Rockox Epitaph, the sightlines of the figures guide audiences toward the body of Christ, prompting onlookers to pray and to contemplate the Resurrection. For example, Rubens depicts the awestruck apostles with their eyes on Jesus, their gazes transfixed by his miraculous appearance and his divine beauty. Similarly, from their positions in the wings, the two patrons of the triptych invite the beholder to look on with them and to imitate their pious meditations. In the left wing, with a hand on his heart and a finger marking his place in a small prayer book, Nicolaas Rockox (1560–1640) looks at Christ in quiet contemplation. In the right wing, his wife Adriana Perez (1568–1619) glances out at viewers, beckoning them to participate, as she uses coral and gold rosary beads to aid her own prayers.

Working in the early seventeenth century, when the Catholic Church encouraged artists to create religious art that captivated the minds and senses of their congregants, Rubens provided his patrons with a compelling depiction of Christ, whose glorious body evokes feelings of awe and devotion in pious viewers. Moreover, because Jesus’s resurrected body promises faithful observers eternal salvation and their own resurrection at Christ’s Second Coming, the epitaph gives hope and joyous reassurance to those contemplating death along with Rockox and Perez. In this paper, I argue that Rubens’s juxtaposition of the eternal, incorruptible body of the Risen Lord alongside the mortal, earthly bodies of three apostles, the portraits of two seventeenth-century patrons, and (in time) the interred bodies of the deceased in their tombs below the triptych, prompted living viewers to meditate on their relationship with God, to compare their bodies with those depicted, and to contemplate their own embodiment.

While my analysis broadly considers early modern viewers’ empathetic responses to the Rockox Epitaph, this paper also explores Nicolaas Rockox’s concerns about his aging body, his mortality, and his relationship with Christ. Best known as Rubens’s friend and patron, Rockox was middle-aged when he commissioned his epitaph: in 1613, he was 52 years old, and his wife Adriana was 45.3 By that point in his life, Rockox had been married for over twenty years, he possessed great wealth and an excellent reputation, and he had achieved substantial professional success: he was knighted in 1599; he had served five of his eventual nine terms as outside mayor (buitenburgemeester) of Antwerp; and he had led the city into the Twelve Years’ Truce in 1609.4 Certainly, Rockox had many blessings to celebrate, but the aging government official lived during a time of high mortality rates, premature deaths, disfiguring war wounds, and rampant disease. Evidence of the transience of life and the corruptibility of one’s body was omnipresent.

Though he would live to be 80 years old, Rockox’s preemptive funerary commission indicates that he was thinking about his own mortality and the state of his body and soul as early as his fifties. The Rockox Epitaph, which eventually hung over the tombs of Nicolaas and Adriana in their family chapel in Antwerp’s Church of the Friars Minor Recollects (Minderbroederskerk), functions as a memorial to its prosperous patrons, proclaiming their piety in perpetuity.5 When the wings of the triptych close over the immaculate body of Christ, the exterior panels declare their patronage, displaying the coats-of-arms of Nicolaas and Adriana above two trompe-l’oeil sculptural cartouches (Figure 2).6 Beyond its practical purpose as a commemorative artwork, I propose that the overall composition—which pictures a life-sized portrait of Rockox beside his Risen Lord—offers insights into the patron’s bodily relationship with God and his perspective on life after death. Ultimately, the body of Christ reminds faithful audiences of both the corporeal renewal and the spiritual salvation made possible through Jesus’s death and resurrection.

Figure 2.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Rockox Epitaph (closed), c. 1613–1615, oil on panel, 146 × 55 cm (wings), Collection KMSKA-Flemish Community, Antwerp, inv. no. 309 and 311.

2. Affective Worship and Religious Art in the Catholic Church

In Rubens’s lifetime, Protestants and Catholics agreed that religious art could have a strong effect on viewers, but the two confessional groups responded to the power of images differently. While some Protestant sects destroyed religious art, trying to prevent idol worship, the Catholic Church preferred to harness the power of images to inspire empathetic connections between faithful congregants and their God. Between 1545 and 1563, the Council of Trent convened on behalf of the Catholic Church to discuss the Protestants’ critiques, to determine areas for reform, and to clarify or restate theological doctrines.7 During their twenty-fifth and final session in 1563, they reaffirmed that religious images are both appropriate and beneficial in the church. The Council of Trent explained:

For the Catholic Church, religious images were helpful aids that channeled prayers and adoration to God and his saints. In their defense of images, the Council of Trent wrote:…images of Christ, of the Virgin Mother of God, and of the other saints are to be placed and retained especially in the churches and that due honor and veneration is to be given them […] because the honor which is shown them is referred to the prototypes which they represent, so that by means of the images which we kiss and before which we uncover the head and prostrate ourselves, we adore Christ and venerate the saints whose likeness they bear.8

The Catholic Church used religious images to teach biblical lessons, bolster faith, and fortify parishioners’ relationships with the Lord. Among the myriad narrative and iconic artworks that they employed, the most important religious images featured Christ.…by means of the stories of the mysteries of our redemption portrayed in paintings and other representations, the people are instructed and confirmed in the articles of faith […] great profit is derived from all holy images, not only because the people are thereby reminded of the benefits and gifts bestowed on them by Christ, but also because, through the saints, the miracles of God and salutary examples are set before the eyes of the faithful, so that they may give God thanks for those things, may fashion their own life and conduct in imitation of the saints and be moved to adore and love God and cultivate piety.9

Artistic representations of Christ were essential tools of the early modern Catholic Church, because Jesus’s body is the location and the proof of several foundational tenets of their faith, including the Incarnation, the Resurrection, and the Transubstantiation of the Eucharistic elements.10 For example, in the Rockox Epitaph, the wounds in Jesus’s palms indicate that he has already been crucified, but his body is no longer bruised or bleeding from the Passion. Instead, Jesus is alive, restored and transformed, appearing to his followers after the Resurrection. According to Christian scripture, Christ died on the cross, sacrificing himself to atone for mankind’s sins. He was buried, and on the third day he rose from the grave. For forty days, Jesus spent time with his disciples and appeared to hundreds of witnesses before ascending into Heaven. Through his triumph over sin and death, Jesus made humanity’s salvation possible—which makes the Resurrection the most important Christian miracle. Depictions of Jesus, such as Rubens’s, illustrate complex theological doctrines, teaching or reminding viewers about the miracles and promises of Christianity.

Remarkably, religious artworks were only part of a much larger, multisensory program of rituals and ceremonies that the Catholic Church performed to engage the minds and the bodies of their congregants. In a decree from their twenty-second session, the Council of Trent explained why sensory worship practices were vital to the Church:

Catholic worshipers heard dynamic speaking, smelled sweet incense, saw ornate clothing and flickering candlelight, and tasted the sacramental bread and wine (the body of Christ) when they took communion. As active participants, the faithful moved and touched their bodies in accordance with the rituals: making the sign of the cross, bowing their heads, closing their eyes, and kneeling and rising from prayer.…since the nature of man is such that he cannot without external means be raised easily to meditation on divine things, holy mother Church has instituted certain rites, namely, that some things in the mass be pronounced in a low tone and others in a louder tone. She has likewise, in accordance with apostolic discipline and tradition, made use of ceremonies, such as mystical blessings, lights, incense, vestments, and many other things of this kind, whereby both the majesty of so great a sacrifice might be emphasized and the minds of the faithful excited by those visible signs of religion and piety to the contemplation of those most sublime things which are hidden in this sacrifice.11

In this period, in the wake of the Tridentine decrees, artists hired by both the Catholic Church and Catholic patrons adopted a similarly multisensory and visually compelling style in their art. Religious Baroque art employs theatrical lighting, emotional intensity, asymmetrical compositions, oversized scale, and foreground figures to involve viewers, to fully engage their senses, and to draw them into the painting. In the Rockox Epitaph, Rubens uses most of those visual strategies to engage the audience’s gaze and grant them greater access to Christ’s glowing body. From the subtly shining crown of Jesus’s head, down through his left fingertips, the artist uses a diagonal to enliven his austere composition and to move the eye back and forth, from Christ’s face to his punctured hand (Figure 3). The strong contrast between Jesus’s luminous body, clothed in bright red, and the opaque black background, illusionistically pushes the Christian savior forward—closer to the beholder outside the painting. By foreshortening Jesus’s right forearm and adding a dark, contrasting outline along that arm and the left shoulder, the artist amplifies the three-dimensionality of the powerful figure. Moreover, Rubens angles Jesus’s body toward viewers outside the triptych, giving living audiences the best view of their Risen Lord and including them in the moment. Each of the life-sized, three-quarter length figures stands in the extreme foreground of the paintings—seemingly close enough to address or to touch.12 Religious Baroque artworks used their engaging style to move people to devotion, to reconfirm Catholic doctrines, and to bring worshippers—in both body and soul—closer to God.13

Figure 3.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Rockox Epitaph (open, center panel), Resurrected Christ appearing to apostles, c. 1613–1615, oil on panel, 143 × 123 cm, Collection KMSKA-Flemish Community, Antwerp, inv. no. 307.

Perhaps more than any other religious order, the Jesuits exemplify the Catholic embrace of empathetic and spectacular worship. Founded in 1540 by Ignatius of Loyola and six companions, the Jesuits, or the Society of Jesus, engaged their audiences with multisensory, theatrical performances and religious images.14 To support their efforts toward evangelization and religious education around the world, the Jesuits staged Christian plays, displayed moving images, and published illustrated emblem books. In 1622, for example, Antwerp’s Jesuit community celebrated the canonization of Ignatius of Loyola and Francis Xavier by filling the streets with music, fireworks, fountains, ballets, a triumphal procession, and twelve open-air stages.15 In a breathtaking display on the Meir, Antwerp’s main thoroughfare, automatons enacted the miracle of Saint Ignatius casting devils out of possessed people—bringing to life the scene painted by Rubens around 1616 for the main altar of the city’s newly constructed Jesuit church.16

In addition to the marvels they orchestrated and the magnificent images they commissioned, the Jesuits engaged worshippers’ senses with their publications. One of their most popular texts was Ignatius of Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises, first published in Latin in 1548. Spiritual Exercises is a customizable guide for individuals undertaking a spiritual journey to reform themselves and to order their lives toward God’s will.17 Under ideal circumstances, each “exercitant” would devote thirty days to the recommended exercises, supervised by a Jesuit “director”.18 The secluded participant is instructed to follow a daily routine of self-examination (to eradicate one’s sins), meditation, contemplation, prayer, penance, and confession.

The immersive, affective exercises were designed to cultivate empathetic engagement with the stories of Christ’s life. Generally, each exercise begins with a preparatory prayer, followed by three “preludes”. During the first prelude, the exercitant recalls the history of a specific biblical episode, such as the events of the Resurrection. The next prelude requires the participant to “compose” or imagine the place where the biblical episode occurs—envisioning the scene in their mind’s eye. When meditating on the Resurrection, one could imagine what it was like to witness Christ’s empty sepulcher. In the final prelude, the exercitant asks God for the appropriate feelings for the day’s meditation: tremendous joy befits Jesus’s triumph over death.19 Next, the participant contemplates three to six points related to the day’s theme. Finally, the exercise concludes with one or more “colloquies”, or imagined conversations with Christ, the Virgin Mary, or God the Father. Each step of the exercise draws the participant closer to God.

To further enhance their imaginative, embodied meditations, the exercitant should engage each of the senses. In the second week, Ignatius recommends applying the five senses to one’s contemplations:

The First Point. By the sight of my imagination, I will see the persons, by meditating and contemplating in detail all the circumstances around them, and by drawing some profit from the sight.

The Second Point. By my hearing I will listen to what they are saying or might be saying; and then, reflecting on myself, I will draw some profit from this.

The Third Point. I will smell the fragrance and taste the infinite sweetness and charm of the Divinity, of the soul, of its virtues, and of everything there, appropriately for each of the persons who is being contemplated. Then I will reflect upon myself and draw profit from this.

The spiritual exercises are deeply sensory, engaging the body and the mind on multiple levels.The Fourth Point. Using the sense of touch, I will, so to speak, embrace and kiss the places where the persons walk or sit. I shall always endeavor to draw some profit from this.20

While there is no record of Nicolaas Rockox owning a copy of the Spiritual Exercises, his financial investment in the local Jesuit church and his proximity to all the pomp and circumstance of the Society of Jesus strongly suggest that he was familiar with the affective approaches they advocated. In 1615, in anticipation of Ignatius’s canonization, Antwerp’s Society of Jesus laid the foundation stone for a new Jesuit church (the current Saint Charles Borromeo Church), which Rubens helped design and decorate. Rockox contributed 4300 guilders to the cost of the building and décor.21 Around 1620, he presented the church with a painting of the Return from the Flight into Egypt by Rubens, which was to hang above the altar of Saint Joseph in the south side aisle of the church. Evidently, the marble altar was also erected at Rockox’s expense: his arms were once visible on it, but they were later concealed by other ornamentation.22 Following the completion of the church, which was dedicated to Saint Ignatius, Rockox donated a silver suspension lamp worth 2000 guilders, which burned with five flames of different colors—an appropriately wondrous gift for the theatrical Jesuits.23

Of course, the Jesuits were not the only religious group to benefit from Rockox’s charity. As a wealthy government official, he commissioned multiple paintings and financed construction projects for the Franciscan Church where he and his wife would be buried. The Franciscans are a medicant order that, similar to the Jesuits, deeply and empathetically contemplated the body of Christ and engaged the bodies of worshippers. Saint Francis, the order’s founder, embodies the concept of living in imitation of Christ. According to Christian tradition, in 1224, while he was praying on the mountain of Verna, a seraph appeared to Saint Francis and gave him the stigmata, the wounds of Christ’s Passion. Rockox appropriately commissioned three paintings of Jesus to decorate the Franciscan Church.

Around 1610, Rockox hired Rubens to paint Christ on the Cross (Figure 4) for the Church of the Friars Minor Recollects.24 In the painting, Christ’s arms and torso are stretched over the Cross, pinned in place by nails in his wrists and feet. The body of Christ shines in the surrounding darkness, as he looks up toward Heaven—still alive, still suffering for the sins of the world.25 Because the painting hung over the door to the sacristy, beholders gazed up at the Crucifixion, simulating the posture of witnesses to the real event beneath the elevated cross. The placement of the image—as well as its realism—engaged both the bodies and the sympathies of the pious viewer.

Figure 4.

Peter Paul Rubens, Christ on the Cross, 1613, oil on canvas, 221 × 121 cm, Collection KMSKA-Flemish Community, Antwerp, inv. no. 313.

As Nicolaas and Adriana prepared their final resting place in the Franciscan Church, they hired Rubens to paint their epitaph and made plans to construct a family chapel behind the high altar. Tragically, the couple could not have predicted that Adriana Perez would die before the Rockox Chapel was built. When she passed away at age 51 on 22 September 1619, Adriana was not immediately buried beneath the Rockox Epitaph, which Rubens had already completed in 1615. Instead, in the fall of 1619, Rockox financed a new high altar and hired Rubens to paint a new altarpiece for the church.26 The Crucifixion, known as the Coup de Lance (Figure 5), and the architectural, marble framework in which it was displayed, were presented to the church in 1620.27 In that same year, Adriana was interred in a temporary tomb below the high altar. Between 1619 and 1624, Nicolaas Rockox sponsored the construction of the so-called Rockox Chapel, dedicated to the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin.28 After living another twenty-one years as a widower, Nicolaas prepared for his own death and arranged for Adriana’s body to be re-interred in the vault of the Rockox Chapel.29 Following his death on 12 December 1640, Nicolaas was laid to rest next to his late wife, beneath the Rockox Epitaph. The couple’s generosity was considered a public good as well as a guarantee that long after they died, people would see their epitaph portraits and pray for them.30

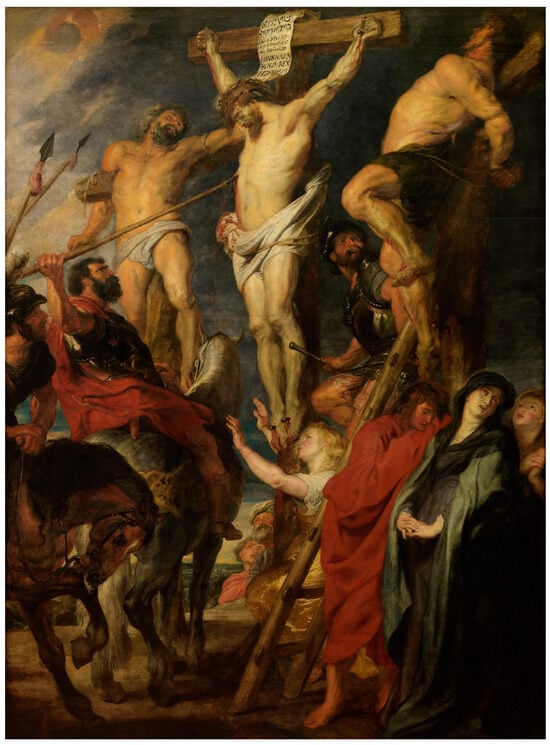

Figure 5.

Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, The Crucifixion (called Le Coup de Lance), 1619–1620, oil on panel, 429.6 × 310 cm, Collection KMSKA-Flemish Community, Antwerp, inv. no. 297.

However, during those twenty intervening years, the grisly Crucifixion altarpiece served as Adriana’s memorial. The monumental painting illustrates the moment in Christ’s Passion when an unnamed Roman soldier pierces Jesus’s side with a spear to confirm that he is dead (John 19:34). According to Jacobus de Voragine’s brief hagiography, the blind soldier was named Longinus. When the blood of Christ ran down the lance into his eyes, Longinus’s sight was restored, and he believed that Jesus was God.31 At the foot of the cross, a beardless youth and grey-bearded older man tilt their heads back to watch the crucifixion. From a similar vantage point, clergymen outside the painting, standing at the high altar in the Franciscan church, could observe Christ’s death and imagine themselves witnessing the biblical event. Through prayer and spiritual exercises, the viewer could envision the scene atop Calvary; hear the moans of the crucified; smell the blood, sweat, and animals; touch the foot of the cross; and taste the tears of the weeping mourners. Each of the three paintings that Rockox commissioned for the Franciscan Church prompts viewers’ multisensory engagement—calling on their own lived, embodied experiences to enhance their understanding of biblical events.

Through affective worship practices and artworks, the Catholic Church engaged the bodies of believers, urging them to contemplate and to empathize with the body of Christ. Thus, Rockox and his contemporaries were conditioned by the dynamic, multimedia context of the Church to interpret art with all five senses. As a result, embodied approaches to worship and to viewing religious images influenced how seventeenth-century audiences understood and engaged with the Rockox Epitaph.

3. Carrying Christ in One’s Heart

Standing in the wings of their commemorative triptych, Nicolaas Rockox and Adriana Perez use meditative aids to focus and stimulate their prayers, engaging their senses in worship. Adriana holds her rosary beads with both hands, sliding her fingers over the coral orbs to count her prayers, keeping track of her devotions through touch. With his left hand, Nicolaas holds a small book with a red cover and gilded pages, marking his place in the religious text with his index finger. The color of the book and the beads matches the crimson drapery clothing Christ, visually reinforcing the couple’s connection to the Risen Lord, who is the subject of their prayers.32 With his eyes on Jesus, Rockox points to his heart with his right hand, signaling his personal relationship with Christ. In sixteenth- and seventeenth-century paintings, touching the center of one’s chest was a well-established gesture of love or friendship.33 Certainly, this affectionate gesture communicates the patron’s love of God. Additionally, I propose that Rockox points to his heart because that is where Christ is supposed to enter the body of the faithful and dwell.34

One of the most popular devotional texts in the early modern period, De Imitatio Christi (The Imitation of Christ),35 written by Thomas à Kempis in the fifteenth century, instructs readers to prepare their hearts to receive God:

Sales records from the Officina Plantiniana, the premier printing press in Antwerp, record that Nicolaas Rockox purchased at least two copies of De Imitatio Christi, first on 26 June 1617, then on 11 September 1620.37 But even if he never read the book, the lessons inside were well-known to seventeenth-century Catholics. Biblical passages, religious treatises, contemporary sermons, and devotional images regularly instructed Christians to cleanse their hearts for Christ to enter.38The kingdom of God is within you, saith the Lord (Luke 17:21). Turn thee with all thine heart to the Lord and forsake this miserable world, and thou shalt find rest unto thy soul. Learn to despise outward things and to give thyself to things inward, and thou shalt see the kingdom of God come within thee. For the kingdom of God is peace and joy in the Holy Ghost, and it is not given to the wicked. Christ will come to thee, and show thee His consolation, if thou prepare a worthy mansion for Him within thee. All His glory and beauty is from within, and there it pleaseth Him to dwell. He often visiteth the inward man and holdeth with him sweet discourse, giving him soothing consolation, much peace, friendship exceeding wonderful.36

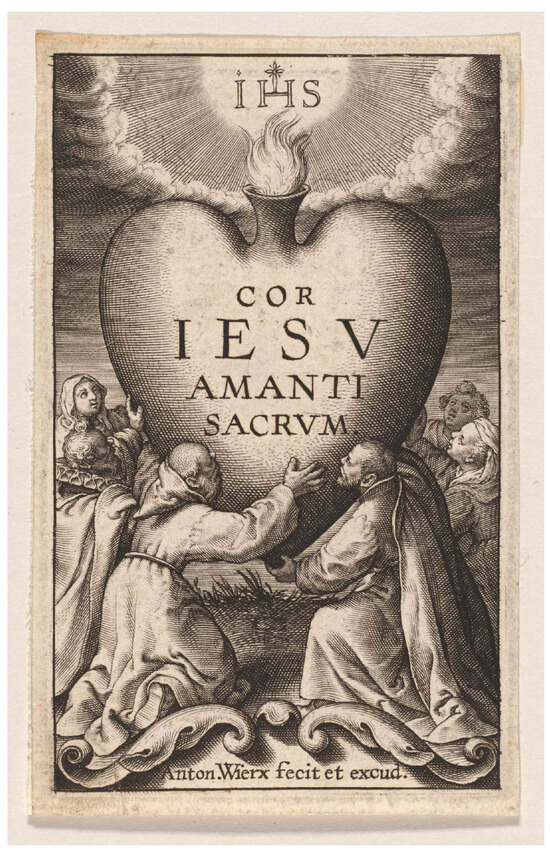

One of the most popular series of religious emblems of the seventeenth century focuses on the human heart, which is purified through its encounter with Christ during prayer and meditation.39 Cor Iesu amanti sacrum (Heart of Jesus Sacred to the Loving Votary or, alternatively, Heart Sacred to the Loving Votary of Jesus) is a set of eighteen small engravings (each approximately 7.8 × 5.6 cm), designed, engraved, and published by the Antwerp engraver Anton II Wierix before 1604.40 The series begins with a title page that pictures a massive, flaming heart held aloft by a group of six contemporaries (Figure 6). The Franciscan and Jesuit friars in the foreground are joined by lay men and women, including an elite gentleman, who wears a millstone collar similar to the one worn by Rockox in his epitaph. With its ensemble of clergymen and laymen, representing different sexes and ages, the book announces that its contents are appropriate for an array of readers.41

Figure 6.

Anton II Wierix, Titlepage for Cor Jesu amanti sacrum, before 1604, engraving, 9.1 × 5.5 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, inv. no. 1278.325-3.

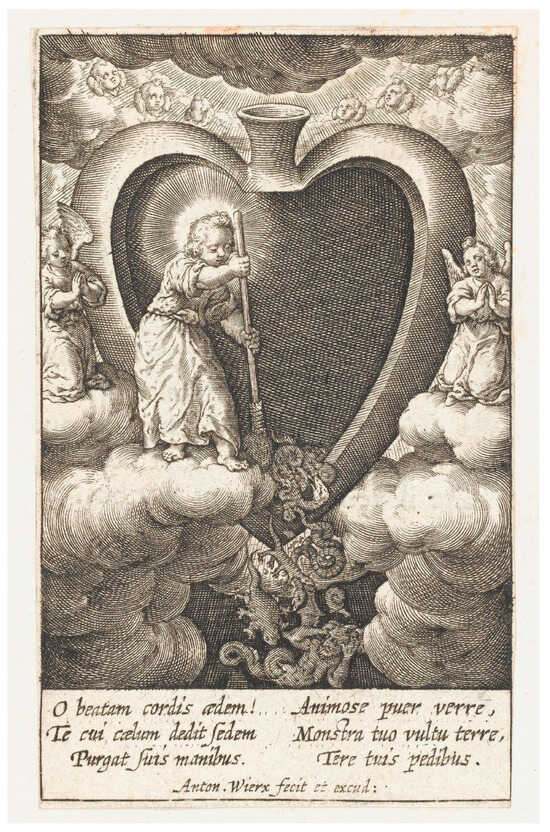

Each of the other seventeen engravings in the series shows an adorable, robed Christ Child interacting with the heart. Before he can take up residence there, the Christ Child sets to work, cleansing the heart of sin and worldly temptations. For example, in one image, he uses a broom to sweep away sins, depicted in the form of snakes, lizards, snails, and a winged demon with a serpentine tail (Figure 7). Inscribed below the scene, the Latin commentary exclaims:

After a sequence of therapeutic interventions, the heart is finally ready to house the Lord. Another engraving in the series features the Christ Child enthroned in the believer’s heart, crowned and wielding a scepter (Figure 8). The radiant halo of light around his head likewise shines around the dove of the Holy Ghost above the purified heart. Below, two courtly angels genuflect in deference to the Lord. The cherub on the right even gestures to his own heart, pointing to his chest like Rockox does. The accompanying inscription reads:Blessed temple of the heart! Let the one to whom heaven gave a throne cleanse you with his own hands. Sweep, courageous boy! Frighten the monsters with your look! Grind them under your feet!42

The charming illustrations of the busy Christ Child in Cor Iesu amanti sacrum personify the transformative, spiritual work of prayer and meditation. This print series visualizes the deeply personal relationship between the body of the individual Christian and the body of God: Jesus is imaginatively internalized and housed in the embodied viewer.Who here would not be calm in expression? Behold, Jesus holds the scepter in the palace of the heart. Jesus, just open your mouth, command what you want, give forth what you command; we are here to serve.43

Figure 7.

Anton II Wierix, The Christ Child sweeping reptilian monsters out of the believer’s heart with a broom, in Cor Jesu amanti sacrum, before 1604, engraving with etching, 7.8 × 5.6 cm, Wellcome Collection, London, inv. no. 31768i.

Figure 8.

Anton II Wierix, The Christ Child enthroned in the palace of the believer’s heart, in Cor Jesu amanti sacrum, before 1604, engraving with etching, 7.8 × 5.7 cm, Wellcome Collection, London, inv. no. 31747i.

In the same period when Rubens designed the Rockox Epitaph, the artist painted an entire triptych on the theme of carrying Christ. On 7 September 1611, the council of the Kolveniers Guild, a prestigious militia guild armed with rifles, hired Rubens to paint them a new altarpiece. As the president (hoofdman) of the Kolveniers Guild, supervising the company for thirty years, between December 1602 and January 1633, Nicolaas Rockox must have played a part in securing the commission for his friend. By 1614, the artist completed the Descent from the Cross triptych (Figure 9 and Figure 10), which was installed over the Kolveniers’ altar in the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp.44

Figure 9.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Descent from the Cross Triptych (closed), c. 1612–1614, oil on panel, 421 × 153 (wings), Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal, Antwerp.

Figure 10.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Descent from the Cross Triptych (open), c. 1612–1614, oil on panel, 421 × 311 cm (center), 421 × 153 (wings), Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal, Antwerp.

The theme of the triptych was inspired by the militia guild’s larger-than-life patron saint: Christopher. According to the Golden Legend, a compendium of the lives of the saints, a giant named Christopher ferried the Christ Child across a river on his shoulders.45 Because he was a giant and because the name “Christopher” (Christophoros in Greek) means “Christ-bearer”, both Catholic and Protestant authorities questioned the authenticity of the saint in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.46 Even so, the Catholic Church defended the saint’s historical existence and celebrated him as a glorious martyr.47 Instead of taking his story literally, however, worshippers were encouraged to think of the giant’s tale as an allegory: like Christopher, a true Christian should willingly carry Christ himself.48

Following Tridentine guidelines about altarpiece decorum, Rubens painted Christopher on the exterior of the triptych (Figure 9).49 When the altarpiece is closed, the muscular giant—modeled after the Farnese Hercules, studied by Rubens in Rome—emerges from the darkness, straining under the weight of the Christ Child on his shoulder. The interior panels of the triptych picture three scenes related to the bearing of Christ (Figure 10). In the left wing, the visibly pregnant Virgin Mary carries Christ in her womb during the Visitation; in the center, lamenting followers of Jesus support his body as they lower him from the cross in the Deposition; and in the right wing, the wizened Simeon holds the holy infant in his arms in the Presentation in the Temple.

Remarkably, Rubens included a portrait of Nicolaas Rockox in the right wing: dressed in classicizing garments, the city official’s profile is visible behind the prophet Simeon (Figure 11).50 Painted with a thicker beard and more hair on his head, the altarpiece portrait closely resembles the likeness of Rockox that Rubens prepared for his epitaph. Perhaps in thanks for the prestigious altarpiece commission or as a mark of their friendship, the artist honors Rockox by depicting him as a witness to a sacred event, sharing the same space as the Christ Child.51 From his privileged position, Rockox watches the old man thank God for allowing him to see Jesus—to see Salvation incarnate—before he dies.

Figure 11.

Peter Paul Rubens, detail of Nicolaas Rockox with Simeon and the Christ Child, The Descent from the Cross Triptych (open, right wing), c. 1612–1614, oil on panel, 421 × 311 cm (center), 421 × 153 (wings), Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal, Antwerp.

After blessing the infant, Simeon spoke to Mary, saying: “Behold this child is set for the fall, and for the resurrection of many in Israel, and for a sign which shall be contradicted” (Luke 2:34).52 Holding the newborn body of Christ, Simeon foresees Jesus’s inevitable suffering (pictured in the center panel), and he alludes to people’s disbelief in the Resurrection to come. In the Christian tradition, the joy of the infant Christ is always linked with the despair of the Passion and the promise of the Resurrection. Rubens depicts the elderly prophet cradling the newborn against his chest, over his heart, where Jesus should dwell in all believers. Here, Simeon is shown like a high priest in the middle of Mass: he wears luxurious red and gold garments, directs his eyes to Heaven, and elevates Jesus, whose round head resembles the consecrated Host. The emphatically Catholic depiction alludes to the miracle of Transubstantiation, during which the holy wafer is transformed into the Body of Christ. Devout early modern Catholics should both carry Jesus in their hearts and take the Body of Christ into their own during communion.

In the Rockox Epitaph, Nicolaas touches his chest and gazes toward the Risen Lord, whom he carries in his heart. While the seventeenth-century gentleman contemplates the idealized exterior appearance of Jesus, God looks at Rockox’s heart. The Lord explained to Samuel:

While religious art is concerned with the appearance of God, God is not concerned with the appearances of men. Underneath his fine garments, the truth of Rockox’s faith is written on his heart, which the Lord reads. It is noteworthy that Rockox’s heart is mentioned in the dedicatory inscription thanking him for the high altar of the Franciscan church:Look not on his countenance, nor on the height of his stature: because I have rejected him, nor do I judge according to the look of man: for man seeth those things that appear, but the Lord beholdeth the heart. (Samuel 16:7)

Burgomaster Rockox put up this altar to Christ.

Its picture was made by the hand of Rubens.

Whether you look to the handiwork of the artist or the heart of the donor,

In the early seventeenth century, faithful Catholics cultivated profoundly embodied relationships with God—carrying Christ within themselves, inviting Jesus into their hearts, and using their imaginations and their senses to contemplate the miracles of his life.nothing could have been given in a nobler spirit.53

4. Appearing to Peter, Paul, and John—Without a Doubt

In the interior of the Rockox Epitaph, Rubens’s artistic decisions direct viewers’ eyes to the resurrected body of Christ, with whom the audience is intended to forge an empathetic bond. To better understand how seventeenth-century onlookers, such as Nicolaas and Adriana, interpreted and interacted with the triptych, one must first clarify the nature and the subject of the center panel. Since the patrons are actively praying in the wings, one can imagine the couple’s ardent, affective contemplations have rewarded them with a vision of Christ, represented by the center panel.54 Rubens’s painting may visualize what the couple is seeing in their minds.55

As Barbara Haeger proposes, the center panel can also be interpreted as a painting that Nicolaas and Adriana are using to guide their prayers—like the book and the rosary beads, the painting of Christ’s appearance is a powerful Catholic devotional tool.56 Note how the dark, shadowy backgrounds of the three interior panels do not align. Nicolaas and Adriana are pictured in architectural interiors: the stone archways overhead signal that they are standing inside a church—possibly an allusion to their soon-to-be-built family chapel.57 Notably, the plum-colored drapery over Adriana’s head is tied back with a cord and fastened to a rod by metal rings. It appears that the deep purple curtain has been pulled back to reveal the painting it protects: an appearance of the resurrected Christ to his apostles.58 Cleverly, Rubens offers viewers the same meditative aid to use in their prayers as the Rockoxes appear to be using: the triptych’s center panel. Audiences are welcome to join the couple, to follow their example, and to use the Rockox Epitaph for their own spiritual exercises.59

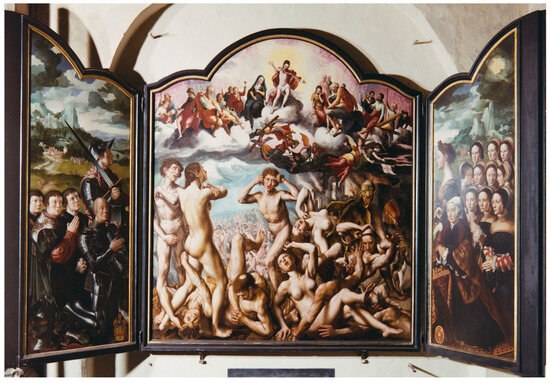

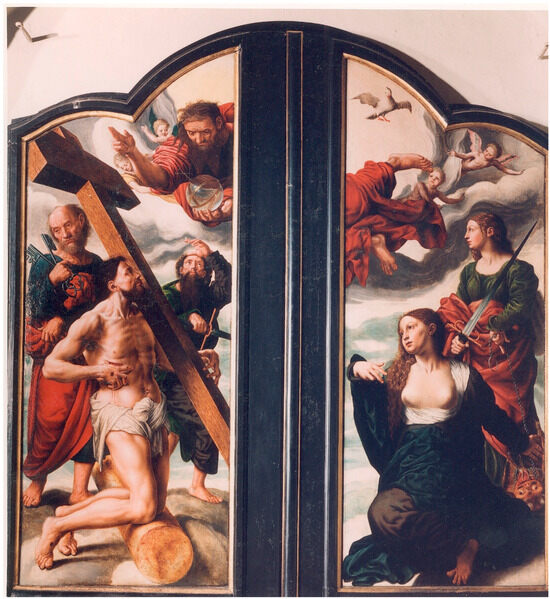

The center panel can, furthermore, be understood as a painting of the Risen Lord based on how Nicolaas and Adriana are portrayed treating the image.60 The patrons are standing in the wings: they are rendered at the same height as the apostles, but hierarchically lower than Christ. Traditionally, patrons are portrayed humbly on their knees. For example, in the interior wings of Jan Sanders van Hemessen’s Rockox Last Judgment Triptych (Figure 12), commissioned around 1537 or 1539 by Nicolaas Rockox’s grandparents, all of Rockox’s relatives are kneeling.61 Moreover, as one would expect, Nicolaas’s grandfather Adriaan is presented by his patron saint, Adrian; likewise, his grandmother Catharina van Overhoff is accompanied by her patron saint, Catherine. In comparison, Nicolaas and Adriana are depicted alone in their panels, without saintly intercessors.

Figure 12.

Jan Sanders van Hemessen, Rockox Last Judgment Triptych (open), c. 1537–1539, oil on panel, 98 × 99 cm (center), Sint-Jacobskerk, Antwerp.

Koenraad Jonckheere proposes that Rubens may have pictured the couple in upright stances to avoid the appearance of venerating the image. They look at the depiction of Christ in the center panel without idolizing it.62 Debates about the proper use of religious artworks—dating back to the beginning of the Church—continued to afflict artists, their creations, and their patrons, even after the Council of Trent’s defense of images in 1563. Only a few years after Rockox was born in 1560, tensions and suspicions boiled up again in 1566, when Calvinist iconoclasts destroyed religious images in Antwerp. By not kneeling, the Rockoxes are decidedly not venerating the painting as they would Christ; instead, they are treating the image as an image. Admittedly, the artist’s decision to picture Nicolaas and Adriana standing is a wise compositional choice that makes the best use of space; however, as Jonckheere argues, the patrons’ postures may also comment on the theological controversy regarding the proper use of images. Because the Catholic Church advocated for the responsible use of religious artworks, the couple’s stance in relation to the painting may signal their Catholicism. Likewise, at a time when Protestants rejected the rosary, Adriana’s bright red prayer beads proudly broadcast her confessional identity as Catholic.63

Whether the center panel is best interpreted as a vision or as another prayer aid, most scholarship on the Rockox Epitaph has concentrated on identifying the scene and the three apostles it portrays.64 Since the late eighteenth century, when Jacob van der Sanden described the painting as the Incredulity of Thomas, art historians have predominately used their interpretive skills and close readings of biblical verses to support and to make sense of that identification.65 According to the Gospel story, recounted in John 20:24–29, Thomas did not believe his fellow apostles when they reported seeing Jesus alive after the Crucifixion.66 In fact, the skeptical disciple insisted that he would not believe until he saw “in [Jesus’s] hands the print of the nails, and put [his] finger into the place of the nails, and put [his] hand into his side”. When Christ appeared to the group again—this time with Thomas present, the Risen Lord instructed his doubting follower: “Put in thy finger hither, and see my hands; and bring hither thy hand, and put it into my side; and be not faithless, but believing”. Once Thomas accepted the truth of the Resurrection, Jesus responded: “Because thou hast seen me, Thomas, thou hast believed: blessed are they that have not seen, and have believed”.

Several scholars, including Adolf Monballieu, David Freedberg, and Koenraad Jonckheere, have acknowledged that identifying the central panel of the Rockox Epitaph as the Incredulity of Thomas is problematic.67 The subject of the panel is neither clear nor self-evident because the image adheres neither to the biblical texts nor to the expected Christian iconography. Nevertheless, the epitaph is continually referred to as The Incredulity of Thomas. According to Freedberg, “Doubting Thomas” in the center panel evokes the concept that belief in the resurrection of Christ need not depend merely on the evidence of sight.68 For Thomas Glen, who interprets the triptych as a whole, the skeptical disciple in the center functions as a foil for the faithful patrons in the wings: unlike Thomas, who required tangible proof to believe, Nicolaas Rockox and Adriana Perez are portrayed as true believers—they are blessed because they “have not seen, and have believed”.69

While the epitaph certainly attests to the patrons’ belief in the resurrection of Christ, I am unconvinced that Nicolaas and Adriana selected the Incredulity of Thomas for their commemorative monument. Valerie Herremans has astutely observed:

Why would a pair of devout Catholics choose to be buried underneath an image of someone questioning the most important miracle of their religion? Scholars offer contradictory accounts of Saint Thomas’s reception in Rubens’s time. According to Alexander Mossel, early modern theologians and commentators condemned Thomas for his disbelief.71 However, Barbara Haeger has found that sixteenth-century commentaries and engravings associated Thomas with belief in the Resurrection, which made him a worthy model for emulation.72 Heike Schlie writes that Thomas was an ambivalent figure with positive connotations as a witness to the miracle of the Resurrection.73It … seems highly unlikely that the donors of the triptych, for whom it was plainly intended as a profession of faith (as witnessed by the book and the paternoster they hold), would have chosen as the central theme of their memorial a subject exemplifying the very opposite.70

Regardless of how the saint was perceived in the seventeenth century, if Rubens truly wished to portray the Incredulity of Thomas, he would have clearly depicted the skeptical apostle inspecting Christ’s wounds with his hands, following Caravaggio (Figure 13) and other contemporaries.74 In their commitment to the Doubting Thomas identification, scholars have largely dismissed Rubens’s unmistakable deviations from the standard iconography of the event. When asked to depict the Incredulity of Thomas, medieval and early modern artists adhered to the well-established tradition of picturing the apostle touching or about to touch Christ’s side wound. For example, in Caravaggio’s graphic rendering from around 1601 or 1602, which Rubens must have seen in the Giustiniani collection in Rome, Thomas plunges his finger into Christ’s body.75 The Flemish painter was certainly inspired by the Italian artist’s painting—the overall compositions are very similar, with the figure of the resurrected Christ appearing to three of his followers against a minimal, dark background.76 However, the differences between the paintings are profound.

Figure 13.

Caravaggio, The Incredulity of Thomas, c. 1601, oil on canvas, 107 × 146 cm, Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg (SPSG)/Fotograf: Hans Bach, Potsdam, inv. no. GK I 5438.

Unlike Caravaggio, Rubens did not depict Thomas or anyone else touching the Lord’s body—he did not even paint a side wound for Thomas to inspect!77 Koenraad Jonckheere and James Pilgrim interpret the artist’s omission of the side wound as an invitation to viewers to assess their faith and the role of empirical evidence in their religion. According to Jonckheere, the artist “deliberately constructed an ‘unstable’ iconography by blurring and omitting key signifiers”, raising questions in the minds of beholders and forcing them to “reconsider their opinions on the sense of sight and touch within the Christian religion and their own devotion”.78 Likewise, in Pilgrim’s estimation, by not painting the side wound, Rubens designed the Rockox Epitaph to prompt an “epistemic dilemma”: the center panel solicits and exacerbates the beholder’s rational doubts, while the behavior of Nicolaas Rockox and Adriana Perez in the wings suggests how the viewer’s doubts might be set aside.79 Certainly, skeptical philosophy circulated among the men in Rubens’s circle, many of whom regularly engaged in quaestio disputata, a thoughtful process of questioning with the goal of gaining knowledge.80 However, neither inquiry-based interpretation of the triptych considers the funerary purpose of the epitaph or the desires of the devout Catholic patrons.

Nicolaas Rockox and Adriana Perez commissioned Rubens to create a monument that would attest to their faith, and thus, the preparedness of their souls to face death. It is highly unlikely that the patrons wished for the epitaph—intended to hang over their entombed bodies for all time—to test their viewers’ faith or spark a complex discussion on empirical evidence. Instead, Rubens, who knew where the side wound belonged (see his Crucifixion, Figure 5), may have chosen not to depict Christ’s pierced torso to prevent an undesired association with Doubting Thomas. Alternatively, by picturing Jesus without the wound, Rubens may have prompted Catholic viewers to remember that the Roman soldier pierced Christ’s body to confirm that he was dead. Perhaps the clever artist excluded the side wound to emphatically confirm that Christ is alive. The missing side wound has certainly inspired many creative interpretations. Yet, it is important to note how Rubens has simplified everything in the center panel: there is no side wound, no background, and no saintly attribute to identify the three apostles. Nothing detracts attention from Christ’s resurrected body.

Previous publications’ insistence on finding and explaining the presence of Thomas and the absence of iconographical details has overshadowed the prominence of the body of Christ in Rubens’s composition. As discussed above, the artist employs several techniques to focus the viewer’s attention on the immaculate Risen Lord—the true subject of the epitaph. Compare, for example, how Rubens exposes more of Jesus’s body than Caravaggio does in his painting. The Italian artist covers Christ’s body with a white cloth, while Rubens highlights the body in red and reveals his muscular torso. Notably, Caravaggio’s three attendant apostles appear in the round, equally sharing the painted space, while Rubens truncates the secondary figures to emphasize the significance of Jesus’s body. The Flemish master even changed the appearances and attitudes of his apostles: they calmly marvel at the miracle while Caravaggio’s figures gape in shock. Rubens was inspired by Caravaggio’s Incredulity of Thomas, but he did not paint a copy—specifically, he did not paint Doubting Thomas.

Tellingly, even among scholars who remain convinced that the Rockox Epitaph features Thomas, there is no consensus on which of the three men is the doubter. Over the years, each of the three figures has been called “Thomas”. Following Jacob van der Sanden, Adolf Monballieu, David Freedberg, Barbara Haeger, and Marius Rimmele suggest that Thomas is the youngest apostle.81 Agreeing with Max Rooses, Thomas Glen points to the oldest man as Thomas.82 Rounding out the possibilities, Lodewijk Taeymans, Cyriel Verschaeve, and Willibald Sauerländer have called the middle-aged man Thomas.83 Misguided by the eighteenth-century identification, scholars struggle to find Thomas among the group. Working with his patrons, Rubens did not paint the skeptical examination of Christ’s body; instead, he painted Jesus appearing to three familiar saints: John, Peter, and Paul.

The youngest apostle is John, the beloved Evangelist, and the eldest is Peter, upon whom Christ built the Church.84 Though they do not carry attributes, their physiognomies are recognizable, since their relative ages and features are well established in pictorial convention. In Rubens’s many renderings of John, the apostle’s visage and hairstyle are subject to change, but he is typically young, blonde, and (mostly) beardless. Some artists paint John with no facial hair, only smooth cheeks, but in the Rockox Epitaph and in the Descent from the Cross triptych (Figure 14), Rubens pictures the young man with a few sparse hairs on his chin. Wearing bright red in the center panel, John the Evangelist is easily recognizable in Rubens’s Descent from the Cross (Figure 10), where the fair-haired youth lowers Jesus’s body down from the cross. Typically, John is pictured in red, but in the Rockox Epitaph, he does not wear his signature color next to Jesus, who is draped in crimson, allowing the focus to remain firmly on the Risen Lord.85

Figure 14.

Peter Paul Rubens, detail of Saint John the Evangelist, The Descent from the Cross Triptych (open, center panel), c. 1612–1614, oil on panel, 421 × 311 cm (center), 421 × 153 (wings), Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal, Antwerp.

The wizened apostle Peter also takes on different forms in Rubens’s oeuvre. The artist alters the length and shape of his grey beard and the degree of his baldness but retains both facial attributes. A recognizable Peter, with a bushy beard and balding head, appears among Christ and the Penitent Sinners (Figure 15), another epitaph painted around 1616.86 Instead of holding the keys of Heaven, Peter tightly clasps his hands together, seeking Christ’s forgiveness for thrice denying that he knew Jesus of Nazareth. Because Rubens continually employs the standard Peter iconography, the older apostle is easily spotted, even among the many saints surrounding the Madonna and Child, for example in the upper left corner of a massive Enthroned Madonna altarpiece from 1628 (Figure 16).87 Knowing how Rubens pictures him, the balding, grey-bearded elder in the Rockox Epitaph is undeniably Peter.88

Figure 15.

Peter Paul Rubens, Christ and the Penitent Sinners, c. 1616, oil on panel, 147 × 130 cm, Alte Pinakothek, © Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich, inv. no. 329, https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/de/artwork/apG9Bom4Zn (accessed on 30 November 2023).

Figure 16.

Peter Paul Rubens, Enthroned Madonna surrounded by Saints, c. 1628, oil on canvas, 564 × 401 cm, Collection KMSKA-Flemish Community, Antwerp, inv. no. IB1958.001.

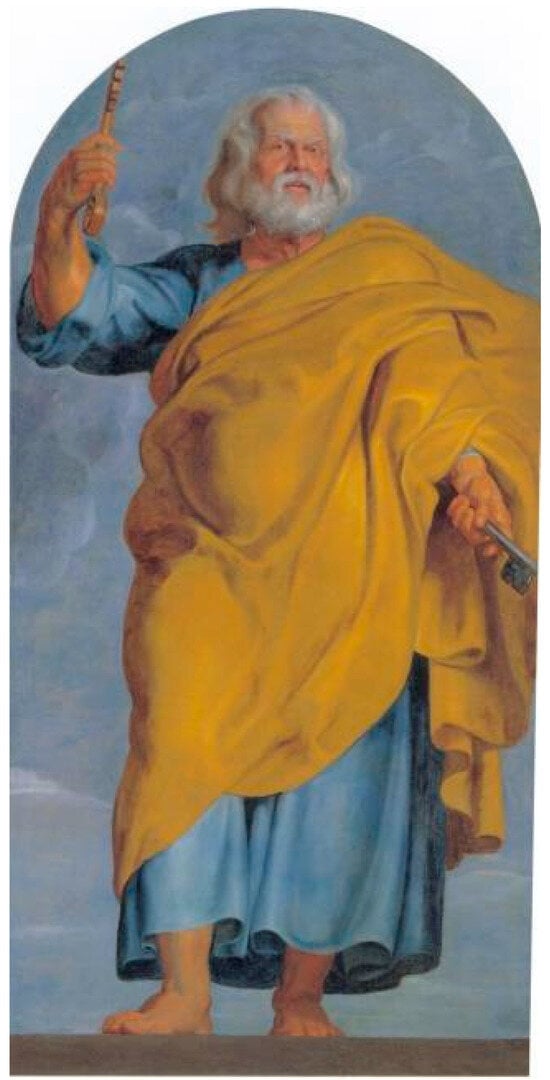

The third, middle-aged apostle is slightly harder to identify without attributes, but I agree with Adolf Monballieu, David Freedberg, and Barbara Haeger that this man must be the Apostle Paul.89 Rubens regularly depicts Paul with dark hair and a brown beard, holding his martyr’s sword. Often, Peter and Paul are pictured together in Rubens’s paintings, drawings, and book illustrations.90 For example, Paul appears next to Peter in the 1628 Enthroned Madonna altarpiece (Figure 17). Standing in the shadows beside Peter, Rubens’s dark-haired Paul has a ruddy complexion that matches his depiction in the Rockox Epitaph. In the same period when he painted the epitaph, sometime between 1613 and 1620, Rubens and his studio assistants prepared a set of pendants featuring Peter and Paul (Figure 18 and Figure 19). These seven-foot-tall, arched canvases were originally installed in the window niches in the apse of the choir of the Capuchin church in Antwerp.91 On the left, in a blue tunic draped with a yellow mantle, white-bearded Peter brandishes his keys. On the right, wearing a red tunic and purple mantle, dark-haired Paul leans against his sword of martyrdom. Because the current whereabouts of the paintings are unknown, the pendants are only available in relatively low-resolution images. Nevertheless, it appears that Rubens and/or the members of his workshop used the same model for this authoritative, pensive Paul and the heavy-lidded, dark-eyed apostle in the Rockox Epitaph—they even have the same full mustache covering their mouths.

Figure 17.

Peter Paul Rubens, detail of Saints Peter and Paul, Enthroned Madonna surrounded by Saints, c. 1628, oil on canvas, 564 × 401 cm, Collection KMSKA-Flemish Community, Antwerp, inv. no. IB1958.001.

Figure 18.

Peter Paul Rubens and workshop, Saint Peter, c. 1613–1620, oil on canvas, 219 × 110.5 cm, whereabouts unknown.

Figure 19.

Peter Paul Rubens and workshop, Saint Paul, c. 1613–1620, oil on canvas, 218.5 × 110.5 cm, whereabouts unknown.

Scholars who attempt to name the figures in the Rockox Epitaph have done exceptional work analyzing the visages and excavating the biblical texts, but few have considered that the patrons almost certainly directed Rubens to depict specific apostles. Nicolaas Rockox and Adriana Perez surely knew the identities of the three saints in their epitaph—and those holy men were important to them. Both patrons may have had an affinity for Paul. According to the 1640 inventory of Rockox’s home, the Antwerp mayor owned one of Rubens’s paintings of the Conversion of Saint Paul (Figure 20), from around 1601 or 1602.92 Traveling on the road to Damascus to continue persecuting Christians, Saul (who became Paul) was blinded by heavenly light and fell to the ground, where he heard and saw Christ (Acts 9). After three days without vision, God returned Paul’s sight; he was baptized; and he began preaching about Jesus. Paul’s conversion and subsequent Christian devotion surely resonated with Adriana Perez, who was a descendant of Spanish conversos or “New Christians” that converted from Judaism to Catholicism.93 In the panel that hung in the couple’s home, Rubens represents the tumultuous moment when Paul falls from his horse; from his position on the ground, he looks up into the sky, where Christ appears in Heaven, emerging from the clouds, wearing a red cloth. The artist depicts Jesus consistently between the biblical panel and the Rockox Epitaph. In the Conversion of Saint Paul, it is noteworthy that Rubens pictures the famous apostle with dark hair and a full beard (Figure 21). Adriana and Nicolaas could certainly recognize Paul’s features in the center panel of their epitaph.

Figure 20.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Conversion of Saint Paul, c. 1598–1599, oil on panel, 72 × 103 cm, © LIECHTENSTEIN. The Princely Collections, Vaduz-Vienna, inv. no. GE 40.

Figure 21.

Peter Paul Rubens, detail of Paul’s head, The Conversion of Saint Paul, c. 1598–1599, oil on panel, 72 × 103 cm, © LIECHTENSTEIN. The Princely Collections, Vaduz-Vienna, inv. no. GE 40.

Moreover, throughout his life, Nicolaas Rockox must have spent hours praying for the souls of his deceased family members in front of a mid-sixteenth-century painting of Peter and Paul, accompanying a muscular, semi-nude figure of Christ (Figure 22). The left exterior wing of Jan Sanders van Hemessen’s Rockox Last Judgment Triptych features the kneeling figure of Jesus as the Man of Sorrows, who shoulders his cross and touches his bleeding side wound. Flanking Christ are grey-bearded Peter, holding the keys of Heaven, and dark-haired Paul, gripping the hilt of his sword of martyrdom. When Nicolaas was just a boy, his father Adriaan died at the age of 45, and he was interred beneath the Last Judgment triptych in the family chapel in St. James’s Church (Sint-Jacobskerk) in Antwerp. On days when the triptych was open, ten-year-old Nicolaas could see the boyhood likeness of his father kneeling behind his armored grandfather (Figure 12). Adriaan, the youngest of the three brothers, is pictured on the far left. In the aftermath of his father’s death, as the eldest son, Nicolaas must have accompanied his widowed mother to St. James’s Church to pray for his soul. Since triptychs were only opened on Sundays and on feast days in accordance with the liturgical calendar, the Rockoxes would have seen the exterior paintings far more often than the interior ones. In fact, the paintings on the exterior wings of the Rockox Last Judgment Triptych may have been the most familiar and most influential images that Nicolaas Rockox knew.

Figure 22.

Jan Sanders van Hemessen, Rockox Last Judgment Triptych (closed), c. 1537–1539, oil on panel, 98 × 99 cm (center), Sint-Jacobskerk, Antwerp.

When he asked Rubens to design his epitaph, Rockox may have instructed the artist to refer to his grandparents’ earlier commission, both to pay homage to his noble lineage, and to celebrate the Rockox family’s history of art patronage in Antwerp. Notably, Rubens’s rendering of Jesus in the Rockox Epitaph echoes that of Van Hemessen in several ways. Both painters present Jesus in profile, looking to the right. The two artists also focus on the muscularity of God-Incarnate, depicting toned muscles in the chest, arms, and neck. The trapezius, the muscle that extends from the shoulder to the neck, is especially thick and over-developed, and the pronounced pectoral muscles are accentuated by the shadowy, recessed sternum. Likewise, both Van Hemessen and Rubens tilt Christ’s torso at the same angle, making his body more accessible to the beholder. Though Rubens’s figure is partially inspired by the ancient sculptures that he studied in Italy between 1600 and 1608 (discussed below), some of the musculature and positioning of Christ’s body seems to come from Van Hemessen’s work, painted for an older generation of Rockoxes. Whether the idea to cite the Rockox Last Judgment Triptych in the new commission came from Rubens or Rockox, a visual connection is apparent. Thus, when a dark-bearded, middle-aged figure and a balding, grey-haired man appear beside Christ in the Rockox Epitaph, they should be understood as Peter and Paul, once again taking inspiration from the earlier triptych.

In her theologically rich interpretation of the Rockox Epitaph, Barbara Haeger also sees an elderly Peter and middle-aged Paul in the center panel. She argues that the two saints signal their different visual experiences with Christ. Peter was an eyewitness to Jesus’s life and resurrection, beholding miracles with corporeal sight; while Paul, who only converted after Jesus’s Ascension, accepted Christ with his spiritual sight.94 In the Rockox Epitaph, as he did in life, Peter stares at Christ’s wounded hand, observing the physical damage done to Jesus’s human body. In contrast, Paul gazes upon the face of his risen Lord, looking at the divine light shining around his head. Though Haeger connects her discussion of vision and faith back to the Incredulity of Thomas, explaining how the doubtful apostle experienced both corporeal and spiritual sight, for me, the assembly of Peter, Paul, and John alludes more generally to the multitude of occasions when the resurrected Christ appeared to his followers.

5. A Moment Out of Due Time, a Promise for All

Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century religious texts offer detailed accounts of Jesus’s appearances after the Resurrection, encouraging readers to meditate more comprehensively on the miraculous events. For example, during the fourth week of the Spiritual Exercises, participants are instructed to contemplate thirteen specific apparitions from “The Mysteries of the Life of Christ Our Lord”.95 Ignatius explains that after Jesus had “taken up his body again, he appeared to the disciples on many occasions, and discoursed with them”.96 In the forty days following his triumph over death, the Risen Lord appeared to (1) the Virgin Mary, (2) Mary Magdalene, (3) the holy women, (4) Peter, (5) the disciples on their way to Emmaus, (6) all of the apostles, except Thomas, (7) all of the apostles, including Thomas, (8) seven apostles who were fishing, including Peter and John, (9) all the disciples on Mt. Tabor, whom he commissioned to teach and to baptize the nations in the name of God, (10) more than 500 brethren at once, (11) James, (12) Joseph of Arimathea, and (13) Paul, after the Ascension.

Likewise, in his popular, richly illustrated Annotations and Meditations on the Gospels, first published in Antwerp in 1595, the Jesuit priest Jerome Nadal (1507–1580), one of Ignatius’s closest collaborators, describes and explicates Christ’s appearances from his Resurrection to his Ascension.97 According to Nadal, Peter and John took leading roles among the apostles—they even believed in Jesus’s Resurrection before seeing him with their own eyes. While John looked after the Virgin Mary, Christ appointed Peter as the pastor to his flock and his vicar on earth, making him the first Pope.98 In the context of the Annotations and Meditations, the Incredulity of Thomas is only one of several important episodes in the Risen Life of Christ. Through multiple appearances, Jesus dispelled the doubts of numerous people—including many of his closest friends and followers.

In addition to the popular Jesuit texts that were circulating, in 1614, Antwerp’s Officina Plantiniana published a new edition of the Breviarium Romanum (Roman Breviary), one of the most important liturgical books of the Catholic faith. Hired by the printing house, Rubens designed the titlepage and ten full-page illustrations for the breviary.99 Intended for everyday use, the massive book contains 1000 pages of prayers, psalms, scripture lessons, hymns, and readings, divided into thematic sections that are organized according to the liturgical calendar and the canonical hours.100 In a 58-page section devoted to the days and weeks following Dominica Resurrectionis (Resurrection Sunday), the breviary offers myriad readings on Christ’s various posthumous appearances. For example, on Resurrection Sunday, one should read selections from Gregory the Great’s twenty-first homily, which explains how the holy women—Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome—brought spices to Jesus’s tomb to anoint his dead body. The women found an empty tomb and met an angel who told them that Christ had risen (Mark 16). Over the next week, breviary owners are encouraged to read about the Supper at Emmaus; Jesus’s appearances to his disciples; the second miraculous draught of fishes; Christ’s apparition to Mary Magdalene; the Lord’s commission to his followers; and the episode when Mary Magdalene informs Peter and John about the empty tomb, so they inspect the sepulcher and believe in the Resurrection. Multiple contemporary religious publications reiterate the lessons of Christ’s many apparitions after his Resurrection.

Some art historians, who do not subscribe to the Doubting Thomas identification, have argued that the center panel of the Rockox Epitaph depicts one of these other instances when Christ appears to his disciples. Ingrid Haug initially proposed that the center panel pictures a more general appearance of Christ before the disciples.101 In agreement with Haug, in his publications, Justus Müller Hofstede refers to the Rockox panel as The Appearance of the Risen Christ to the Disciples.102 Three passages in the Gospels describe Jesus’s appearance among his disciples, during which he displays his wounds as proof of his triumph over death.103 Instead of the Gospel of John, where the skeptical Thomas story appears, Müller Hofstede cites the Gospel of Luke, in which Christ appears to the eleven disciples. Rubens’s choice to reduce the number of disciples—from a group of ten or eleven, down to three—can be explained by the influence of Caravaggio or his preference for clarity and pictorial effectiveness over adherence to the biblical text.104

Mireille Madou has proposed that the center panel depicts Christ appearing to his closest friends: John, Peter, and James the Greater.105 While no Gospel text documents the Risen Christ appearing to that specific group, Madou considers it a logical occurrence in the sequence of events in their friendship. Although I do not see the middle-aged apostle as James the Greater, I agree with Madou that the scene in the center panel does not represent a moment described in the Gospels.

In religious art, Peter, Paul, and John are sometimes depicted together, as they are in Albrecht Dürer’s Four Apostles from 1526, but there is no Gospel text that describes Jesus appearing to those three men as a group.106 Christ appeared to Peter and John during the forty days following the Resurrection; then, after the Ascension, Jesus appeared to Paul. According to Paul, in his first epistle to the Corinthians, after the Resurrection, Christ:

Since the grouping of Peter, John, and Paul cannot represent a specific biblical episode, as they were never together with their Risen Lord, I propose that the center panel should be interpreted as a moment “out of due time”. David Freedberg notes how Rubens’s epitaphs, painted between 1612 and 1618, are “timeless in a very specific sense; they had to be, because of the very nature of their function”, as commemorative funerary monuments.108 Even though he maintains the Incredulity of Thomas identification, Freedberg acknowledges, “A work such as the Rockox triptych does not depict a particular biblical incident, but represents a scene which transcends the purely narratival moment”.109…was seen by Cephas [Peter]; and after that by the eleven [apostles]. Then he was seen by more than five hundred brethren at once… After that, he was seen by James, then by all the apostles. And last of all, he was seen also by me, as by one born out of due time. For I am the least of the apostles, who am not worthy to be called an apostle, because I persecuted the church of God.107

Rubens’s Christ and the Penitent Sinners, painted around 1616, is another epitaph that pictures a group of biblical figures who never actually assembled (Figure 15). Creatively, Rubens brings the resurrected Jesus together with the golden-haired Mary Magdalene, cross-bearing “Good Thief” Dismas, crowned King David, and grey-bearded Peter. The four figures beg their Risen Lord for the forgiveness of their sins in the artist’s visualization of the Catholic sacrament of penance. Christ and the Penitent Sinners is an atemporal, doctrinal piece—and so is the Rockox Epitaph.110

Expanding on Jacob van der Sanden’s identifications of the apostles, Adolf Monballieu first described the Rockox Epitaph as a doctrinal piece that represents belief in the resurrection of the dead.111 According to Monballieu, the apostles Thomas, Peter, and Paul were chosen because of their testimony in connection with the Risen Lord—not because of their presence at a particular apparition.112 In agreement with Monballieu’s logic, I suggest that John, Peter, and Paul may have been selected for their scriptural accounts concerning the resurrection of mankind. In John 11: 25–26, Jesus explains: “I am the resurrection and the life: he that believeth in me, although he be dead, shall live: and every one that liveth, and believeth in me, shall not die for ever”. In his first epistle, Peter instructs Christians to “sanctify the Lord Christ in your hearts, being ready always to satisfy every one that asketh you a reason of that hope which is in you” because Jesus Christ “swallow[ed] down death, that we might be made heirs of life everlasting”.113 Building on the work of Monballieu, I propose that the Rockox Epitaph is not just a doctrinal piece about belief in the Resurrection, but about the promise that the Resurrection offers pious Catholics.

The miracle of Christ’s Resurrection is not limited to Jesus’s own triumph over death: the promise of corporeal resurrection extends to all humankind. In 1 Corinthians 15: 20–22, the Apostle Paul explains, “But now Christ is risen from the dead, the firstfruits of them that sleep [die]: For by a man came death, and by a man the resurrection of the dead. And as in Adam all die, so also in Christ all shall be made alive”.114 Jesus’s Resurrection prefigures and makes possible the resurrection of the dead at his Second Coming for the Last Judgment. Notably, Paul’s words are quoted five times throughout the Dominica Resurrectionis section of the Breviarium Romanum, reiterating and underscoring the broad theological implications of the Resurrection miracle: because Christ is risen, all shall be risen.115

In the same epistle to the Corinthians, Paul goes on to describe how the buried, earthly bodies of mankind will be resurrected and transformed in an instant—they will no longer possess mortal bodies like that of Adam, but celestial bodies like that of the Risen Lord. When Christ returns, Paul explains:

When the dead are resurrected, what is sown in corruption will rise in incorruption; what is sown in dishonor will rise in glory; what is sown in weakness will rise in power; and what is sown a natural (earthly) body will rise a spiritual (heavenly) body (1 Cor. 15: 42–44). In his commentary on Corinthians, first published in 1614, Cornelius à Lapide (1567–1637), a Flemish Catholic priest and Jesuit, explains: “The natural body is one that eats, drinks, sleeps, digests, toils, suffers fatigue, is heavy, and offers resistance to other bodies”.117 When the earthly body is raised as a spiritual body, it is not a spirit, but “spiritual in the sense of being wholly subject and conformed to the spirit, so that it no longer stands in need of food or drink, it toils not, and feels no weariness, but is, so to speak, heavenly and deified…”118 Fallible human bodies that suffer illness, wounds, aging, and various calamities and shortcomings will be transformed at the resurrection into incorruptible, immortal forms—akin to the body of Christ, as he is gloriously pictured in the Rockox Epitaph. Death no longer has its sting because the joyful promise of resurrection and of eternal life with God drives away the despair associated with mortality.In a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet: for the trumpet shall sound, and the dead shall rise again incorruptible: and we shall be changed. For this corruptible must put on incorruption; and this mortal must put on immortality. And when this mortal hath put on immortality, then shall come to pass the saying that is written: Death is swallowed up in victory. O death, where is thy victory? O death, where is thy sting?116

Anna-Claire Stinebring argues that the center panel of Van Hemessen’s Rockox Last Judgment Triptych (Figure 12), which Nicolaas Rockox’s grandparents commissioned, portrays the fully embodied resurrection of humankind and, thus, offers viewers “hope and joyful anticipation in the face of death”.119 She notes how the resurrected bodies in the Last Judgment panel are “uniformly youthful and whole”—none of the figures is skeletal or decaying.120 Humanity is pictured in spiritual bodies; their earthly bodies have been transformed in an instant. While Christ’s judgment of the masses is, at first, terrifying to behold, the triptych trained the Rockox family to confront death, temper their fears, and find comfort in the promise of their own resurrection. While Van Hemessen was painting the Last Judgment panel, in 1539, the Antwerp chamber of rhetoric, The Gillyflower, won first prize at the Ghent landjuweel, a competition for local chambers of rhetoric, with their answer to the prompt: “what is the dying man’s greatest hope?”121 In their play on the theme of dying well, The Gillyflower rhetoricians replied: “the resurrection of the flesh”. Antwerp’s pious intellectuals understood the promise and the hope offered by Christ’s Resurrection.

In his own massive depiction of the Last Judgment (Figure 23), completed by 1617, Rubens pictures the resurrection of the flesh.122 Muscular, idealized bodies of men and women rise from the ground, carried up to Heaven by angels on the left or pulled down to Hell by devils on the right. In the center of the Great Last Judgment, below Christ’s feet, two angels with billowed cheeks sound their trumpets. Just as Paul foretells, “in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet”, the dead rise incorruptible and changed. Unlike Van Hemessen, Rubens includes skeletal figures emerging from their tombs as the trumpets blare to illustrate the instantaneous transformation described by the apostle. Notably, the Flemish artist’s animated skeletons and horn-playing angels resemble figures in Michelangelo’s Last Judgment fresco (c. 1536–1541), painted on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel. During his travels in Italy between 1600 and 1608, Rubens studied Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel figures, as evidenced by his red chalk drawing of a seated male nude (ignudo) in the British Museum.123 As Marcia B. Hall has demonstrated, the Italian master’s famous Last Judgment fresco, in fact, represents the Christian doctrine of the Resurrection of the Body described by Paul.124

Figure 23.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Great Last Judgment, c. 1617, oil on canvas, 608.5 × 463.5 cm, Alte Pinakothek, © Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich, inv. no. 890, https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/de/artwork/Dj4mkQbL5A (accessed 30 November 2023).

In consultation with his devout patrons, I propose that Rubens incorporated the theme of mankind’s corporeal resurrection in his design for the Rockox Epitaph. By juxtaposing the renewed, heavenly body of Jesus with the earthly bodies of the apostles and the patrons, the artist introduces a provocative tension that forces audiences to compare the mortal figures with the embodied deity. In contrast to Jesus’s immaculate and everlasting body, Nicolaas, Adriana, and the apostles all appear as living humans, subject to aging and the passage of time. Rubens’s naturalistic, life-sized rendering of the figures reminds faithful viewers of the transformation to come—giving sick, aging, and disabled onlookers hope as they await their own resurrection and eternal life with God. As early modern audiences employed affective viewing strategies to forge multisensory, empathetic connections with Christ, they may have also extended their imaginative empathy to the other figures in the paintings.

6. Mortality and the Ages of Man

The idealized, heavenly body of Christ shines with divine light, differentiating the deity from the nearby mortals in the Rockox Epitaph. The juxtaposition of immortal and temporal figures may have reminded viewers of humanity’s fallibility and the origins of their own imperfection. According to Christian tradition, Nicolaas Rockox, Adriana Perez, and the rest of humankind are descendants of Adam, who was made in God’s perfect image, but who brought Original Sin into the world through disobedience. When Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit, they recognized their nudity and felt shame. God punished the first couple and all their children with mortality, manual labor, and pain in childbirth (Gen. 3: 16–19). Adam and Eve’s primordial punishment is written on the bodies of their descendants.

In his treatise On the Imitation of Statues, written between 1609 to 1615, Rubens states that it is wise to “embrace the close study of [ancient] statues”, because mankind has “fallen to a worst state, unforgiven after our fall or weakened by irrecoverable loss as the world grows older”.125 Believing that humanity had declined since the Fall, Rubens insisted that artists imitate exemplars from Antiquity that were temporally closer to God’s original design. According to the artist, ancient sculpture is “quite close to its natural original and to perfection”, while the bodies of living men bear the signs of centuries of corruption, sin, and mortality—“perfection slides downward into a worse state with the coming of successive vices”. In Rubens’s estimation, the ancients also possessed superior bodies because they exercised daily, while his lazy contemporaries primarily ate and drank, developing “protruding” stomachs and “effeminized” legs and arms.126 Seventeenth-century men’s bodies fell short of Rubens’s exacting standards, so he referred to ancient statues when rendering divine figures.

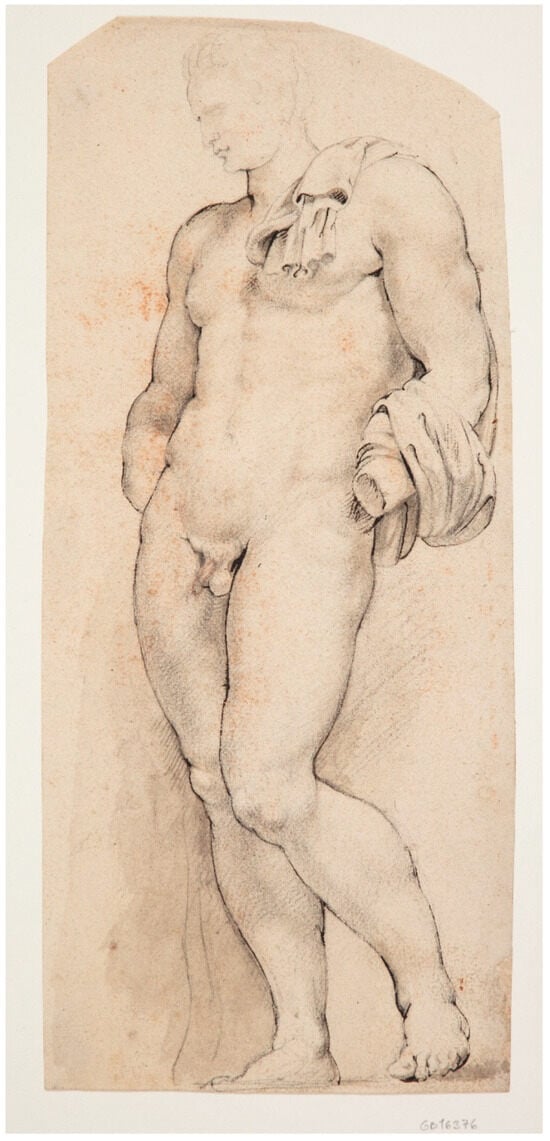

Appropriately magnificent in form and musculature, Jesus’s body in the Rockox Epitaph is partially modeled after the Belvedere Hermes (known to Rubens as Antinous), an ancient Roman statue that the Flemish artist encountered in the Vatican collections in Rome (Figure 24).127 Rubens’s lost drawings of the Vatican Antinous survive in the meticulous copies created by Willem Panneels, an assistant who joined the workshop around 1623.128 As Panneels’s copy illustrates, Rubens borrowed and adjusted several features of the statue in his depiction of Christ: the torsos are mirrored; both figures have drapery over their arms; and the musculature of the arms and abdominals are nearly identical. Looking at his portrait next to Rubens’s resurrected Jesus may have urged Rockox to think about the imperfection of his own body and his transience in comparison to the eternally perfect body of the Redeemer.

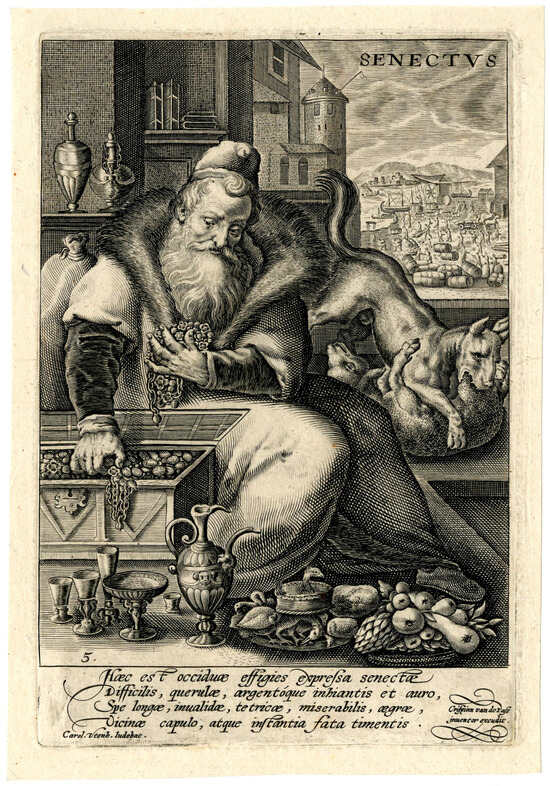

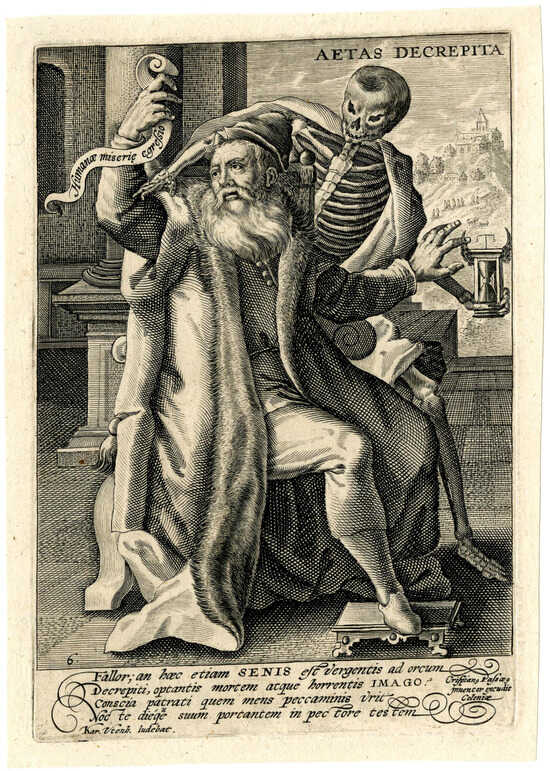

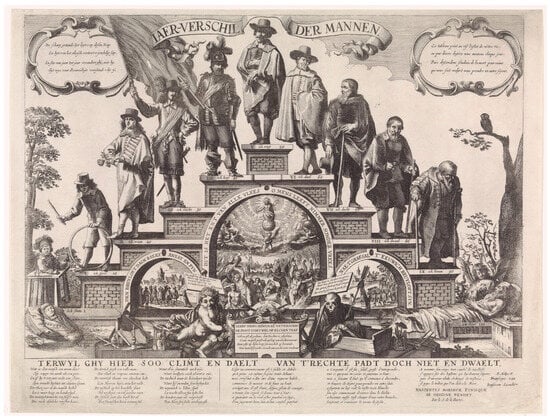

Figure 24.